NGURRA - Dwelling of desert animals - mounds, burrows, warrens, lairs and nests

Melbourne Art Fair

20 – 23 February 2025

NGURRA - Dwelling of desert animals - mounds, burrows, warrens, lairs and nests

Melbourne Art Fair

20 – 23 February 2025

Convention & Exhibition Centre Booth M3 NGURRA - Dwelling of desert animals - mounds, burrows, warrens, lairs and nests

Melbourne

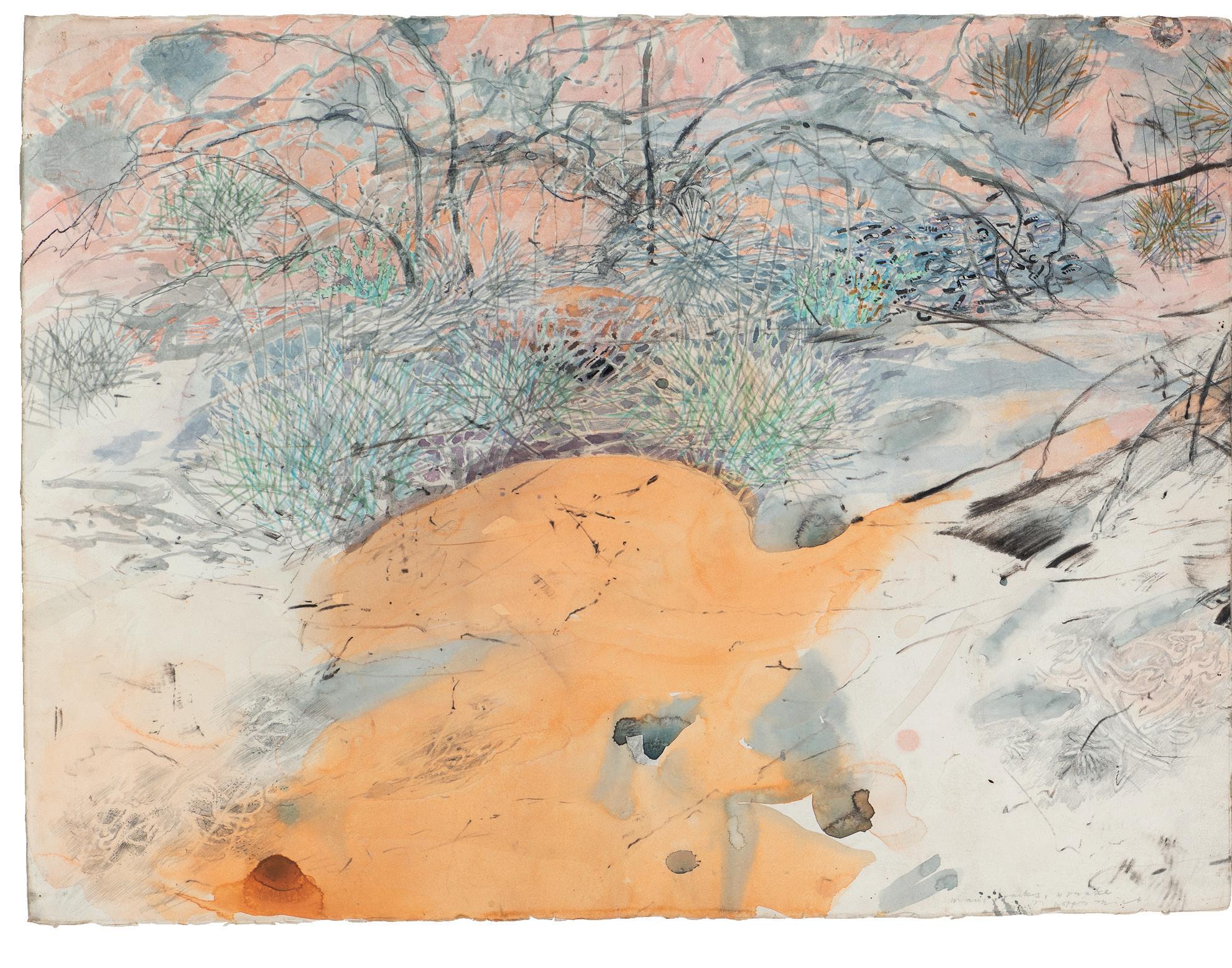

Cover image: Great Sandy Desert – the burrows of the Thorny Devils usually face south (detail) 2023-24

watercolour and etching on Gampi and cotton rag paper

88 x 208 cm

All artwork photography by Ian Hill

A USTRALIAN G ALLERIES

T 03 9417 4303

melbourne@australiangalleries.com.au

australiangalleries.com.au

2024 watercolour and charcoal on paper 56 x 152 cm

John Wolseley settled in Australia in 1976. Since then he has had numerous exhibitions; each one a survey and distillation of a particular landscape or ecosystem. In these large installations he relates the microcosm of plant, bird and animal to the abstract dimensions of geology and the earth’s dynamic systems.

In this NGURRA series he has focused on how particular mammals and reptiles dwell within the landscape, and how they create and construct their architectures of dwelling – mounds, burrows, warrens, lairs and nests. Some of these paintings are about animals which are on the verge of extinction – Greater Bilbies, Burrowing Bettongs, Golden Bandicoots among others.

In this exhibition we can feel something of the excitement of seeing how these endangered animals have been returned to their ancestral lands after their long absence, and how at Newhaven, one of the Australian Wildlife Conservancies vast reserves, they are thriving and breeding and transforming the land.

John Wolseley’s work can be found in all state galleries in Australia and numerous public and private collections. He has an honorary Doctorate of Science from Macquarie University, Sydney and is a recipient of the Emeritus Medal from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council. He is represented in Melbourne by Australian Galleries and in Sydney by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

For the last three years I have been having an El Dorado of a time, investigating and painting the habitat and modes of dwelling of desert mammals and reptiles. It all started when John Kean and I visited one of the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) sanctuaries at Watikinpirri/Newhaven, west of Alice Springs. I started to draw the different animals which have been returned to their ancestral country after it had been fenced to keep out the cats and foxes that had caused their demise. Greater Bilbies, Bettongs, Mala - Rufus Hare Wallabies and Golden Bandicoots, and many more of the species which used to be all over Australia and which are now sadly reduced to dangerously low numbers. It took some time before I actually saw the creatures in the flesh as it were. When one wanders amongst the Desert Oaks and across the spinifex plains one is physically near the actual critters but they are usually hidden or running away. One sees their tracks and other signs of them. They are cryptic. The OED definition of cryptic is ‘secret, mystical, mysterious and enigmatic’.

In July 2022, Joe Schofield of the AWC took me to see Bettong warrens in the calcrete rocks which are in the low country between the sand hills. For many thousands of years, Bettongs have burrowed underneath the calcrete slabs to excavate their warrens - living as family groups of 20 or more. They are the only macropod to engage in burrowing and engineering. Some 120 years ago rabbits moved in and evicted them. And then after the AWC take-over, the rabbits were sent packing and the first few Bettongs were released near their old warrens.

It was only a year after the Bettongs were released that Joe Schofield took me to see the warrens. It was nearly the first time that he had inspected these particular new diggings and there was a rapturous expression on his face when he saw the voluminous piles of earth piled-up outside the burrows. Joe placed motion-sensitive cameras near several of the burrows. In the morning we printed some of the images. It was a revelation. One after another, the photos emerged like some animated film showing Bettongs popping out of the dark burrows, peering nervously and then bounding out beyond the camera. One felt almost some kind of guilt - or is it just rather rude spying on them like some clumsy paparazzi. One shot caught a Woma python as it moved towards a frightened young Bettong with its mother. This was one of the snakes which had preyed upon the rabbit usurpers for the past 120 years, then starved after the rabbits had been kicked out. They then rejoiced at the arrival of the Bettong restaurant. These photos and others taken by AWC scientists have been a marvellous resource for me in the making of this exhibition. As in the work - Lustful Bettongs returning to Watikinpirri – Newhaven 1.

Burrowing Bettongs return to Watikinpirri - Newhaven 2024 etching 26 x 33.5 cm edition 30 variable

The Bilby returns - Great Sandy Desert 2024 woodcut, etching, chine-collé and watercolour 32 x 39.5 cm edition 30 variable

Enormous thanks to Kaitlyn Gibson for her extraordinary work in the making and printing of the etchings, woodcuts, and nature print elements of these works. And to Jeff Gardner of Cascade Art, Maldon, for his equally superb printing.

Over several days I walked and sometimes crawled over the slabs of calcrete rock under which the Bettongs lived. Sometimes I wore the camouflage clothes I had recently bought. I was thinking that they mimicked the rocks and vegetation in quite a cryptic way - my idea was to morph into the landscape, and become one with it. I crawled along the ground very slowly and in short spurts. I think I did go someway into the umvelt or ‘life world’ of these curious earth engineers, and even began to move into some sense of their life in Deep Time. The idea that one could get a feel for the vast time scale during which the land was formed; how the hills rose up and were eroded by wind and water over those thousands of years came to me over the week spent watching the growth of the mounds of earth as they were burrowed out by hyperactive Bettongs. Each day I would see them rise and rise; and then have the sudden and cosmic leap of understanding that the hills on this savannah plain had been created by the Burrowing Bettongs over thousands of years.

For me the story of these animals creating the forms and shapes of this country has a beautiful correspondence with First Nations’ stories about how this land was formed by the actions of human and animal ancestor figures. These stories of heroic ancestors (Jukurrpa) are celebrated in the paintings of the great artists of this region. As John Kean commented, it is quite magical to consider the prescient work of the Papunya Tula Artists, the founding painters of the desert art movement, several of whom painted this Country. Their paintings are especially instructive now, as Country is being restored by the AWC working in partnership with Traditional Owners. The network of mythic journeys of Possum Ancestors, painted by Mick Wallankarri Tjakamarra, Tim Leura and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri is inscribed into this very landscape. The night of 8 August 2024 was particularly moving for all involved, as a bunch of boisterous Brush-tailed Possums were returned inside the fence, after having been locally extinct for at least half a century. It felt that Mick Wallankarri’s painting, Storm Men meet Possums and Potato Men at Watikinpirri (1974) suddenly came alive.

Down the years I have talked to many elders from these central desert lands about their connection to Country and what it meant to dwell in the land of their Ancestors. Last year Iria Kuen came to my camp with her fellow AWC ranger, Alice Nampijinpa and we spent the day wandering around the warrens of the Burrowing Bettongs and digging out edible grubs from the roots of Witchetty bushes. My understanding of Warlpiri is minimal but I did notice how certain words seemed to come up in the conversation. One was ngurra. Later in Alice Springs I asked Fiona Walsh, the redoubtable environmental polymath, about this particular word. She said that the word ngurra could be said to embody – one of the foundational concepts of the Aboriginal world view. We looked through the Warlpiri dictionary and found the more obvious translations such as hole, cavity, place for sleeping, camp, nest, lair and burrow. Then there was a further meaning – Country, land (place with which a person is associated by conception, ancestry and ritual obligation).

Basking mound, birthing pool and communal latrine of the Great Desert Skink - Watikinpirri 2024 watercolour and charcoal on Kozo and Rakusuishi paper 97 x 117 cm

This was incredibly exciting to me because it seemed to carry with it the idea that a person could be dwelling in their traditional country; and feel that they are deep dwelling in the site which, in the first morning, or Jukurrpa, was actually made by their ancestors. What power and emotional depth this gives to the idea of dwelling and belonging to Country! So different in so many ways from how we whitefellas dwell or do not dwell in Australia.

In a curious way this series of paintings has for me become a search into the many different modes of dwelling adopted by all the diverse human beings, and then by all the animal beings. I was out there drawing these rare and fascinating animals and sometimes watching them as they were returning to their ancestral dwelling places. Then I realised that the important thing to do was rather than trying to draw the actual animals themselves I could paint them in the process of returning. I should make paintings of NGURRA - Dwelling of desert animals - mounds, burrows, warrens, lairs and nests.

I also spent days and days drawing the Great Desert Skink communes which Dr Danae Moore showed me. It had been a marvellous experience investigating these large golden and pewter coloured Skinks – one of the few lizard species known to construct and maintain underground dwellings. Danae carried her thesis concerning the environmental threats to this vulnerable species, and she would excitedly relate the diagrams to the relevant features of the basking mounds and burrows. These little mounds of glowing red sand rested between the clumps of spinifex and near each one we found the Skink latrines –scatterings of black and white skats. Here I made the painting, Basking mound, birthing pool and communal latrine of the Great Desert Skink – Watikinpirri.

These Skinks live in groups of as many as 30 individuals and share the same basking mound, latrine and even their maternity ward. One can sometimes find the round flat termite pavements which the Skinks use as birthing pools when it rains. The water rests on top of what are actually inverted termite mounds; that is to say, the vertical cones or castles of cathedral termite mounds face downwards into the ground. These shallow lenses of water are where the Skinks give birth to their young. I put my easel next to a beautifully rounded basking mound. It’s like a miniature sand dune, with the tracks of Bilbies and Bettongs skittering over it. But no Skink foot prints. They were all fast asleep – hibernating all through these winter months. One day as I approached the mound, I saw a little golden puff of sand and the blur of a moving creature. Phew! A sleepy Skink must have chosen that moment to emerge onto the mound and steal a bit of winter sun. Then I saw the imprint of a perfect fan-like hand there on the sand, so crisp, so clear! Such a precious gift.

John Wolseley, 2024

Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) is on a mission to restore Central Australia’s extinct animals to the desert. At Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, on Ngalia Warlpiri and Luritja Country, AWC has constructed one of the world’s largest conservation fences, creating a safe haven where unique and threatened species are making a comeback. Newhaven is a world-class rewilding project in the heart of Australia.

AWC manages a network of sanctuaries and protected areas around Australia with a practical approach informed by science. AWC field teams and ecologists work in iconic landscapes like the Kimberley, the Top End, Cape York, and Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre; tackling weeds and feral animals, reinstating ecologically friendly fire regimes, and monitoring ecosystems as they recover.

About 300 kilometres west of Alice Springs, AWC’s Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary covers an area larger than the ACT, including ancient quartzite ranges, a sprawling chain of salt lakes, spinifex plains and patches of mulga woodland. Since 2006, AWC has worked closely with local communities to control feral animals and improve fire patterns to protect the biodiversity of the desert.

Newhaven’s wildlife reintroduction project is about re-establishing healthy populations of threatened mammal species which have been extinct in Central Australia for decades.

A 40-kilometre cat-proof fence – two metres tall and electrified – protects 9,450 hectares of habitat from the ravages of feral predators. Since 2017, AWC has returned 8 different species of mammals to the sanctuary, including Mala, Red-tailed Phascogale, Golden Bandicoot, Greater Bilby, Brushtail Possum, Burrowing Bettong, Brush-tailed Bettong, and the critically endangered Central Rock Rat. The project is a lifeline for these species, several of which are on the brink of extinction.

Today, Newhaven’s red sand is busy with the tracks of thriving native mammals; burrowing, feeding, breeding and playing their part to restore a healthy desert ecosystem.

For more information visit: www.australianwildlife.org