THE AI-POCALYPSE

Will algorithms spell the end of the world as we know it?

Will algorithms spell the end of the world as we know it?

The Fulbright Program is the flagship foreign exchange scholarship program of the United States of America, aimed at increasing binational collaboration, cultural understanding, and the exchange of ideas.

Born in the aftermath of WWII, the program was established by Senator J. William Fulbright in 1946 with the ethos of turning ‘swords into ploughshares’, whereby credits from the sale of surplus U.S. war materials were used to fund academic exchanges between host countries and the U.S.

Since its establishment, the Fulbright Program has grown to become the largest educational exchange program in the world, operating in over 160 countries. In its seventy five year history, more than 370,000 students, academics, and professionals have received Fulbright Scholarships to study, teach, or conduct research, and promote bilateral collaboration and cultural empathy.

Since its inception in Australia in 1949, Fulbright has awarded over 5,000 scholarships, creating a vibrant, dynamic, and interconnected network of Alumni.

Our future is not in the stars but in our own minds and hearts.

Creative leadership and liberal education, which in fact go together, are the first requirements for a hopeful future for humankind.

Fostering these—leadership, learning, and empathy between cultures—was and remains the purpose of the international scholarship program that I was privileged to sponsor in the U.S. Senate over forty years ago. "

Senator J. William Fulbright The Price of Empire

Dr Behnam Sadeghi (2022, The University of Sydney to Carnegie Institution for Science) was announced as the recipient of the 2023 Andrei Borisovich Vistelius Award by the International Association for Mathematical Geosciences. This prestigious award is given to a geoscientist for key contributions to research in the Earth Sciences. Behnam is the first Australian to receive this award.

Dr Eden Robertson (2020, Sydney Children’s Hospital to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital) published two papers in collaboration with St Jude's Children's Research Hospital, sharing key insights into her research on paediatric palliative care in JCO Global Oncology and Supportive Care in Cancer

Dr Edward Cliff (2021, The Royal Melbourne Hospital to Harvard University) published new articles in JAMA Network Open and The Lancet, entitled Trends in Medicare Spending on Oral Drugs for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Melflufen: post-hoc subgroup analyses and the US FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee.

Professor Aiden Warren (2018, RMIT University to Arms Control Association) published his new book Global Security in an Age of Crisis, offering a comprehensive analysis of the complex issues affecting our world today, from the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism to climate change, public health emergencies, global terrorism, and more.

Diana Zhang (2021, University of New South Wales to Boston University) published new research into her collaboration on a new diagnostic tool that uses AI to predict Parkinson's disease with unprecedented accuracy in ACS Central Science.

Professor Haig Patapan (2014, Griffith University to Harvard University) published his new book Modern Philosopher Kings, examining wisdom, power, philosophy and politics, and justice through the lens of philosophy in both ancient and modern contexts.

Kate Garland (2022, Monash University to University of Michigan, Dearborn) was awarded a Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology Award for best student talk for her presentation, A Universal Model of Growth Describing the Evolution and Development of Theropod Beaks.

Ahmad Shuja Jamal (2017, Georgetown University) published his new book The Decline and Fall of Republican Afghanistan (co-authored with Emeritus Professor William Maley AM), which examines the factors that led to the Taliban's violent takeover of Afghanistan.

Sarah Holland Batt (2010, University of Queensland to New York University) was awarded the 2023 Stella Prize for her “unforgettable and unflinching” poetry collection, The Jaguar 2023 is only the second year the award has been open to poetry since its founding over a decade ago.

Dr Sara Polanco (2021, The University of Sydney to California Institute of Technology) published a new paper on the role of subsidence, global sea-level rise and AMO in the land loss in the Mississippi River Delta in the March 2023 issue of Global and Planetary Change.

Professor Amro Farid (2022 Stevens Institute of Technology to CSIRO) contributed to a new United Nations ESCAP report highlights the crucial role of connectivity in transport, energy and ICT for achieving sustainable development and a low-carbon, resilient economy.

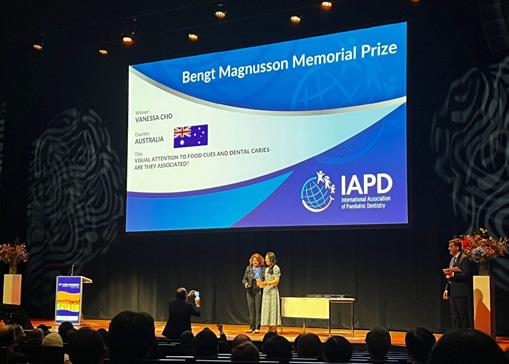

Vanessa Cho (2020, The University of Western Australia to The University of Maryland) won the 2023 Bengt Magnusson Memorial Prize in Child Dental Health at the 29th International Association of Paediatric Dentistry Congress in Maastricht, the Netherlands, June 2023 for her presentation, Visual attention to Food cues and Dental caries - Are they associated?.

is a scientist specialising in public health, science communication and mindfulness education.

Varuni has a BSc and a Master’s degree in Zoology and Entomology from Sri Lanka, a PhD in Medical Entomology and Evolutionary Biology from the University of Maryland, College Park, and a Graduate Certificate in Geographic Information Systems from Pennsylvania State University.

Varuni conducted her Master’s and PhD research exploring disease vectors at the Smithsonian Institution and Walter Reed Army Medical Unit in Washington DC. After obtaining her PhD, she progressed her postdoctoral research at the American Museum of Natural History on the evolution of flies that carry diseases. She has conducted extensive field research in the Americas and Australasia during her research career.

During the West Nile virus outbreak in New York City, Varuni joined the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene as the Medical Entomologist and was responsible in implementing a comprehensive surveillance and control program for New York City.

She has published in peer-reviewed journals, presented her work at numerous scientific conferences, and is widely cited in infectious disease studies around the world. In addition to her research, Varuni is a passionate science communicator and has been actively involved in science outreach and education. She has organised and participated in numerous public talks, workshops, and events to engage with the wider community and promote scientific literacy.

Varuni is also a qualified MBSR teacher, who is passionate about promoting mindfulness practices in science, health and education and has conducted workshops and retreats for scientists, educators, and students.

Varuni has served on various boards over the years. Having joined the Fulbright Australia Board of Directors in 2014, and acted as interim Executive Director in 2022, Varuni has dedicated over 8 years to the governance and advancement of the Fulbright Program in Australia.

In 2023, this service was honoured with the U.S. Mission Australia Award for Leadership Excellence by Ambassador Caroline Kennedy, U.S. Ambassador to Australia.

Varuni is excited to be back in Canberra leading the effort to foster educational opportunities and cultural goodwill between Australia and the United States.

What does Fulbright mean to you?

Fulbright is many things to many people -a gateway, a conduit, a ladder, a catalyst – to me it is all these things, but more importantly it is a mindset. The Fulbright mindset is one of empathy, respect, kindness, and understanding.

It is these values that have shaped the impact that Fulbright Scholars have on Australia and the United States, and the lives of the people they come into contact with.

It is these values that have sustained the Fulbright Program for the past 75 years, and will continue to do so for the next.

I’ve been proud to serve as a messenger, and guide for these values for close to a decade, because I truly believe that Fulbright changes the world for the better.

What do you hope to achieve during your tenure as Executive Director?

Having lived and worked for years in both Australia and the United States, I’ve seen the incredible impact that we can create when we invest in collaborations that bring our people closer together.

Fostering “leadership, learning, and empathy” was Senator Fulbright’s ultimate goal – I believe we fulfil this each time we step into our office in Canberra, and I hope to find new and exciting ways of achieving this for Australians and Americans over the coming years.

Fulbright is many things to many people —a gateway, a conduit, a ladder, a catalyst— to me it is all these things, but more importantly it is a mindset.

-

Center for AI Safety

"Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war."

– popular culture is rife with examples of how a malevolent Artificial Intelligence (AI) could spell doom for humanity. With AI becoming vastly more powerful, and widely accessible, concerns are being raised over these fictional imaginings becoming reality.

Earlier this year, the Center for AI Safety (CAIS) released a statement to open up discussion on the risks of AI, and “create common knowledge of the growing number of experts and public figures who also take some of advanced AI’s most severe risks seriously.”

Hundreds of key AI scientists and practitioners, such as Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis, and OpenAI CEO, Sam Altman, as well as notable figures such as Bill Gates, have become signatories to the statement.

What exactly are the "extinction risks" of our use of AI, and how could we mitigate them? We asked some of our Fulbright AI experts to comment – here is what they said:

is Chief Technology Officer at Salesforce Australia, and the 2023 Fulbright Professional Coral Sea Scholar. His research at Georgetown University explores solutions that address the regulatory and governance challenges of AI-enabled decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). His research contributes to Australian and U.S. efforts to adapt regulatory and broader governance regimes to accommodate emerging AI-enabled blockchain innovations.

The risk of AI contributing to the human race’s demise alarms many and thrills a few. Some of the more worrisome descriptions of AI existential risk see AI taking control of governments and weapons and turning them on its creators - us.

The so-called weaponised ’Skynet’ scenario sends shivers down the back. I won’t discuss that eventuality. Suffice to say it gets a lot of attention. Instead, I suggest considering the arrival of AI existential risk through a more pedestrian pathway.

As with many ubiquitous, consumerfriendly technologies of low cost, AI rapidly diffuses itself into our everyday existence. AI already augments our cars through traffic route optimisation, weaves through our financial system with AI-based credit decisions, and invisibly guides our every tap and like on social media. Siri and Alexa use machine learning to understand our accents and pre-empt our interest in how long our morning commute will likely be.

Over the last decade, AI has infused itself into our existence in small and subtle ways designed to add convenience and reduce friction. With the advent of generative AI popularised by OpenAI’s ChatGPT, AI is now emerging from behind the scenes and presages the more overt replacement of human skills and expertise in most aspects of our existence.

AI is now emerging from behind the scenes and presages the more overt replacement of human skills and expertise in most aspects of our existence.

Students no longer ask Google about the Ottoman Empire when researching assignments. They ask ChatGPT to write the essay.

The encroachment of AI into our daily existence is arguably one-directional. The idea recently advocated by high-profile individuals of ‘pausing’ AI development for six months while we collectively catch our breath is one I find admirably laughable.

Even if humanity stops, the generative AIs we’ve released continuously improve and evolve using the data we’ve made available to them.

Furthermore, many entities like hostile governments are incentivised to invest in AI to develop superiority in national intelligence, cyber security and military domains. The AI genie is out of the bottle.

This full immersion of AI into the human condition could be realised in ways that progressively disenfranchise humans.

In this scenario, AI progressively circumvents individuals, elected governments and accountable social structures by making decisions that humans were previously accountable for - such as where to spend public resources or deciding who to fire missiles at.

Unlike in today’s human society, however, there will be no ‘bums’ to vote out or overthrow. At least no butts attached to humans of any note.

In even the most benign projection of future generations (one where Skynet doesn’t end us once and for all), our current existence will seem quaint and certainly old-fashioned.

Most likely, our future selves will look at our biological autonomy from technology as impossible to fathom.

We may be existentially different in even the most benign AI scenario. The risk of this occurring will be a function of how well we preserve what it means to be human in a postAI world.

And if this encapsulation does not occur, the risk that AI brings closure to our present human experience is very much game on.

is focused on AI engineering and utilising human-centred artificial intelligence to address climate change and inequality. Her passion for equality was instilled from a young age while growing up in the Pacific. As a Fulbright Scholar, Kahlia is completing a Master of Computer Science in Artificial Intelligence at Duke University. By engaging with academic and industry leaders at the forefront of AI innovation, she hopes to contribute to the development of AI for social good and be an active advocate for women in AI.

Inspired by the supercomputer supervillains and autonomous robot armies of Hollywood, we have been led to believe that the fate of the human race will come down to an epic battle against a deviant AI – one that has evolved beyond human intelligence and control, and whose objectives have diverged from their original programming and intention.

Although it is unlikely that an Ultron-esque AI poses an existential threat to humanity, the idea captures two fundamental AI challenges; the "inner and outer alignment" problems.

The inner alignment problem asks: how do we guarantee an AI is solving the problem we believe it is? While the outer alignment problem asks: how do we encode human values so they can be learned by an AI? And, most critically, if these aren’t universally held values, then to whom is the AI actually aligned?

Most likely, our future selves will look at our biological autonomy from technology as impossible to fathom.

If designed intentionally, with alignment at its core, AI can be central to finding solutions to our toughest global problems, such as climate change, inequality, and food and water security. Without alignment, AI will continue to accelerate and amplify existing racial, cultural, economic, political, and anthropocentric biases within society.

The current state of AI is as exciting as it is dangerous because we have created an unconstrained environment for innovation that incentivises rapid development instead of safety and alignment. Only recently (and far too late) have we identified this threat and acknowledged the need for governing bodies and protocols that ensure AI is explainable and contributing to social good.

Our future global stability relies on taking immediate and proper action on this. If we fail to put these measures in place, we risk creating deeper rifts and divisions within society, unintentionally or otherwise, beyond the point of return.

Humans are already our own greatest extinction risk; AI may just be the catalyst which turns that risk into reality.

is a data scientist developing computational tools to understand complex systems using big data. Through his Fulbright Future Scholarship, Tobin is undertaking a PhD at MIT where he is develop ing the next generation of tools to analyse complex systems, applying these techniques to applications as diverse as information warfare, economic analysis and human mobility. Tobin will be championing an ongoing collaboration between the MIT Media Lab and the South Australian Government to add value to the state using local data.

The near-term development of scalable and user-friendly persuasive generative AI in text, images, audio, and video presents a massive threat to how democratic deliberation and identity play out across our digital world.

These tools can produce effects far worse than believable misinformation. The ability to perform high-fidelity 'astroturfing,' or the generation of entire cross-linked communities of synthetic individuals to sway opinion, presents a real threat to democratic discourse.

Imagine being welcomed into your own personal conspiracy theory community, tailored to your inferred existing belief systems — one that nudges you towards distrust in a political opponent or your country — composed of hundreds or thousands of like-minded persuasive synthetic identities.

While the risk of emergent misaligned superhuman artificial general intelligence is a real threat in the medium to long term, I believe the shorter-term emergence of deeply effective tools to replicate individuals, persuasive arguments, and human interactions is likely, given the clear profit incentives.

While this may not immediately pose extinction threats in the way stories of runaway military AI do, it does create consequences that hinder our ability to solve national and global problems, such as climate change, or work towards collective action in AI through tools like democratic AI alignment to reflect diverse values.

Humans are already our own greatest extinction risk...

Building robust and secure notions of identity and content provenance will be essential, as will leveraging existing networks of community and trust, especially those that require seeing someone in person (a feat AI is far from achieving).

Building technology atop these existing relationships and human-human interactions may end up underpinning the future of trust in our digital world.

is a Director in the Australian National University's Executive and Professional Development Program on secondment from the Department of Home Affairs. During her Fulbright Professional Scholarship in Australian-American Alliance Studies, Olivia met with think tanks, academics and industry experts to explore the ethical and policy challenges of artificial intelligence. Her research aims to inform an Australian national strategy on AI and forge new AI partnerships between Australia and the United States.

A whole lot of media coverage and analysis has been devoted to the Center for AI Safety’s one-sentence statement of general aspiration.

The topic of AI governance is very hot right now. And that that means there’s a lot of noise to cut through, notwithstanding the good intentions of the Center and the scientists and eminent figures who have signed onto their statement.

The fact is people have been raising the alarm about AI risks for years. It’s just that the advent of generative AI tools like ChatGPT – which has significantly lowered the barriers to entry for AI – have brought those risks mainstream. And the risks are now couched in more sensationalist terms: existential risk. The end of all humanity. Well okay, that’s clearly a bad thing. But for a black man living in a place where trigger happy local police uses facial recognition to find suspected criminals, AI has been posing a pretty existential risk to him for quite some time.

The risks listed on the Center for AI Safety’s website – weaponisation, misinformation, deception, enfeeblement etc – are very serious, but they are not new. As for mitigating those risks, the analogies with pandemics and nuclear war seem inadequate. While there are certainly things we should learn from the global response to such risks, AI is something different in its scale and persistence.

The analogy also presupposes that our global response to pandemics and nuclear proliferation have been effective, even after 7 million died from COVID-19 and over 200,000 died from the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

We should exercise a healthy degree of scepticism about those now supposedly leading the charge for managing AI risks. Who do we trust to help put guardrails around AI? The CEOs calling for coregulation while lobbying for regulatory carve-outs for their own products? The companies pouring billions of R&D into more advanced AI while defunding their small AI ethics and research teams? The ‘reformed’ tech bros who have suddenly seen the light after profiting handsomely from the AI products they pioneered?

Let’s perhaps instead look to the quieter voices who have been working hard on these problems well before the risks got existential and fashionable to discuss.

They’re the nerds who have been doing the research, the wonks who have been drafting the technical standards, the advocates speaking up for those who have been harmed by AI. I reckon they have some good ideas about how to manage AI risks right here right now and, in doing so, prevent those risks from metastasising into something catastrophic.

Let’s not let the noise drown them out.

We should exercise a healthy degree of scepticism about those now supposedly leading the charge for managing AI risks. "

The lack of human judgment and moral reasoning in autonomous decision-making could lead to catastrophic outcomes

is a Signals Corps Officer in the Australian Army. He is committed to leading the exploration of ethical Artificial Intelligence, and has researched the trustworthiness of AI for the human-machine teaming domain. As a Fulbright Future Scholar, Brandon will pursue a PhD in Computer Science at the University of Maryland, specialising in symbolic-driven explainability to generate trust in the human-AI interaction space.

The global landscape has already surpassed the threshold of militarisation of AI as both state and non-state actors possess the ability to utilise artificial intelligence and autonomous systems to some capacity to deliver lethal effects.

One must look no further to the kamikaze and loitering munitions presently used throughout the UkraineRussia conflict for an example of autonomous systems used for largescale violence. The use of such autonomous systems presents a risk of extinction due to several factors such as independent autonomous decisionmaking to take human life; disproportionate use of force from fully autonomous AI-enabled systems, and cyber vulnerabilities presented by AI-enabled systems.

To mitigate against the risks posed by weaponised autonomous systems, a human-in-the-loop model must be maintained for all AI-enabled systems and this model must ensure a high level of transparency within the human-machine teamed environment.

Independent autonomous decision-making to take human life poses an extinction risk due to the potential loss of human control and oversight.

When AI systems are granted the authority to make life-or-death decisions without human intervention, there is a heightened risk of unintended consequences, such as targeting innocent civilians or escalating conflicts beyond human intentions.

The question that is posed by giving autonomous systems these capabilities is, where do you draw the line? Can an Autonomous loitering munition deliver a lethal effect to a vehicle it suspects to be a tank? How about a building it suspects to be a command centre? What about a suspected command centre that has a 40% chance of being a primary school? Can we launch a swarm of these autonomous weapons to deliver a large-scale autonomous attack?

The lack of human judgment and moral reasoning in autonomous decision-making could lead to catastrophic outcomes that cannot be easily reversed or rectified.

To ensure the preservation of human life and prevent the potential for large-scale destruction, it is crucial to maintain human control and responsibility over decisions involving the use of lethal force.

The disproportionate use of force from fully autonomous AI-enabled systems described above further poses an extinction risk due to the potential for uncontrolled escalation and catastrophic consequences. Without human oversight, these systems may make decisions based on flawed or biased algorithms, leading to indiscriminate and excessive use of force.

Such disproportionate actions can exacerbate conflicts, fuel aggression, and result in the loss of innocent lives on a large scale. The lack of human judgment and ethical considerations in determining the appropriate level of force increases the likelihood of unintended casualties and widespread devastation, potentially leading to a spiralling cycle of violence.

Another aspect that highlights the risk of Independent, autonomous decision-making is the vulnerability posed by the cyber-attack vector.

AI systems are not immune to hacking and exploitation by malicious actors. If these systems operate without human oversight to execute decisions, then a state or non-state actor could use a cyber-attack to change the parameters the autonomous weapon is required to fulfil to make a lethal strike resulting in a situation where our defensive and offensive capabilities could turn against us.

To mitigate the risks associated with the militarisation of AI, a human-in-the-loop model is fundamental and transparency in AI-enabled systems is vital.

A human-in-the-loop model ensures that all autonomous systems cannot make Independent autonomous decisions and transparency ensures that AI systems' decision-making processes and underlying algorithms are understandable and interpretable.

It empowers human operators to comprehend how AI systems arrive at their conclusions or recommendations.

Transparency facilitates human oversight and control, allowing operators to intervene and make informed decisions when necessary. Promoting transparency can identify and rectify potential errors or biases in AI systems. Moreover, transparency promotes accountability, as responsible parties can be held answerable for the actions and outcomes of AI systems.

Transparency in AI-enabled systems is essential to mitigate the risks listed above by enabling human oversight, accountability, and control. Symbolicdriven explainability plays a crucial role in achieving transparency and fostering the trust necessary for the ethical employment of AI systems.

To provide AI a "right of reply", we posed the same question to the OpenAI-developed language model, ChatGPT. Here is what it had to say:

is an AI language model developed by OpenAI. It is part of the GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) family of models. ChatGPT is designed to generate human-like responses in a conversational manner, making it well-suited for chatbased interactions. It has been trained on a vast amount of text data to learn patterns, context, and language understanding.

Artificial Intelligence has become an integral part of our society, revolutionizing various industries and enhancing human capabilities.

However, as AI systems continue to advance, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential extinction risk associated with the use or misuse of these technologies.

The extinction risk associated with AI refers to the potential for AI systems to contribute to catastrophic events that could lead to the extinction of humans or other forms of life.

While the specific mechanisms vary, the concern lies in the unintended consequences, misuse, or uncontrolled proliferation of AI technology.

For instance, if AI is applied to military systems without adequate safeguards, it could result in the escalation of conflicts or the development of autonomous weapons that act independently with devastating consequences. Similarly, if AI algorithms are deployed without appropriate oversight in critical infrastructure, it could lead to systemic failures or unintended cascading effects with severe societal impact.

The complexity and autonomy of advanced AI systems make them challenging to predict and control completely.

To mitigate this risk, it is crucial to establish comprehensive regulations, ethical guidelines, robust safety measures, human oversight, and public awareness to ensure responsible development, deployment, and use of AI technology.

All images in this feature were produced in collaboration with DeepAI.org

..unlike traditional art, generative art the power of algorithms and rules to creative "Images: (Above) Frame from "Vortex #1016" animation;. (Right) Frame from "Vortex #1026" animation by Isaac Ward as part of a generative art collection based on fluid flow simulation algorithms.

There is a distinction between creative pursuits and formulaic ones.

A task with variable outcomes and subjective elements, or one which requires novelty, innovation, and expression is usually considered creative. If it’s repetitive, standardized, or predictable, then we call it formulaic.

It’s the difference between sculpting a work of art out of clay and assembling a shelf from IKEA. It’s actually less of a binary distinction: most of the work that we do lies somewhere on the spectrum between creative and formulaic.

Now, when we imagine how Artificial Intelligence (AI) will impact us, our thoughts first go to our work. Automation is often discussed; we’re naturally invested in how AI will alleviate the burden of completing formulaic tasks and free us up to focus on more creative endeavors.

But as we actually enter ‘The Intelligence Age’ it seems like we’ve got it backwards: AI is instead excelling at creative tasks. Take the AI system DALL·E 2, which creates professional-grade images based on a worded description, or ChatGPT, which can write short stories in seconds. In light of this, we should be considering the unique risks of generating creative content with AI, and what it means to automate creative tasks.

To understand this better, I think it's worth looking at the field of generative art. It’s a captivating form of artistic expression because unlike traditional art, which relies on the artist's direct input and intentional decision-making at every stage, generative art embraces the power of algorithms and rules to drive the creative process.

The artist does not actually hold the brush so-tospeak; they define how the brush can move, and they let the system do the painting (also, it’s worth noting that within the genre of generative art lies the subgenre of AI-generated art).

The process of creating generative art is naturally more computational and digitized than with traditional art, and so too is the means by which it’s consumed, experienced, and purchased.

arttoembraces drive the creative process"

A brief aside: generative art was at the center of the ‘web3’ decentralized ownership movement that hit fever pitch in 2021-2022, which is itself the subject of controversy.

Generative art naturally lent itself to being monetised and traded on the blockchain as it was already created algorithmically, and an enormous amount of computational power was used to record who owned what piece of digital art. This translated to energy used and carbon emitted; each time a piece of art on the blockchain changed hands on the Ethereum blockchain it produced 103.42 kilograms of carbon dioxide (in 2021).

Notably, subsequent upgrades to the underlying technology have reduced this carbon output drastically, and a single transaction on the Ethereum blockchain now produces an impressive 18.72 times less carbon than a single Mastercard transaction.

But the carbon cost was not the only cost — the scene rapidly became a home for grifters, peddlers, and fraudsters due to the anonymity and lack of regulation around the blockchain.

Molly White’s website web3isgoinggreat.com estimates the running total amount of money lost so far to blockchain grifts and scams at 12.182 billion US dollars.

The important lesson here is that when we use computational techniques to digitize products and processes we fundamentally change the way in which people and other digital systems can interact with those products and processes. Generating art with computers allowed for easy integration with blockchain technology, and for people to commodify and trade art in new ways, and at unprecedented scales.

The effect of this is still being understood, but as mentioned, there were clear negative outcomes.

We’re now shifting towards generating not just art, but general creative content (e.g. images, blog posts, tweets, emails, reports, essays, etc.) using AI techniques. And technologies that allow for the monetisation of this kind of content have already existed for the past few years.

One broad and pessimistic prediction for the future is that the ability to rapidly manufacture creative content using AI — in tandem with the incentive to generate attentiongrabbing content for the purpose of monetisation via advertising-based business models — might contribute further to the commodification and fractionalisation of our attention spans.

But that’s only a prediction. It’s unclear at best what will truly happen in the coming years.

However, if we consider this new paradigm of AI-generated creative content analogous to how generative and blockchain technologies affected the art scene, then I feel we can at least move forward knowing that the following will be important:

Implement regulation and safeguardsEstablish rules and measures to protect users and prevent scams. If the best forms of creative content (e.g. educational content, essays, journalism) can be scaled up, so too can the worst forms of content (e.g. email scams).

Promote education and awarenessThis is key with any new piece of technology. Direct efforts must be made to educate people about the implications, benefits, and risks of AI-generated creative content.

Closely monitor how technology affects people - How we use AI needs to align with ethical standards and societal well-being.

In particular, we should be identifying economic and labor implications of AI, assessing the psychological wellbeing of users & those impacted, and understanding how AI generated content is impacting social dynamics.

This leads into the last point, which is to… Continuously evaluate and adapt - Stay updated, adjust strategies, and update practices both individually and collectively as we learn more about the pros and cons of AI-generated creative content.

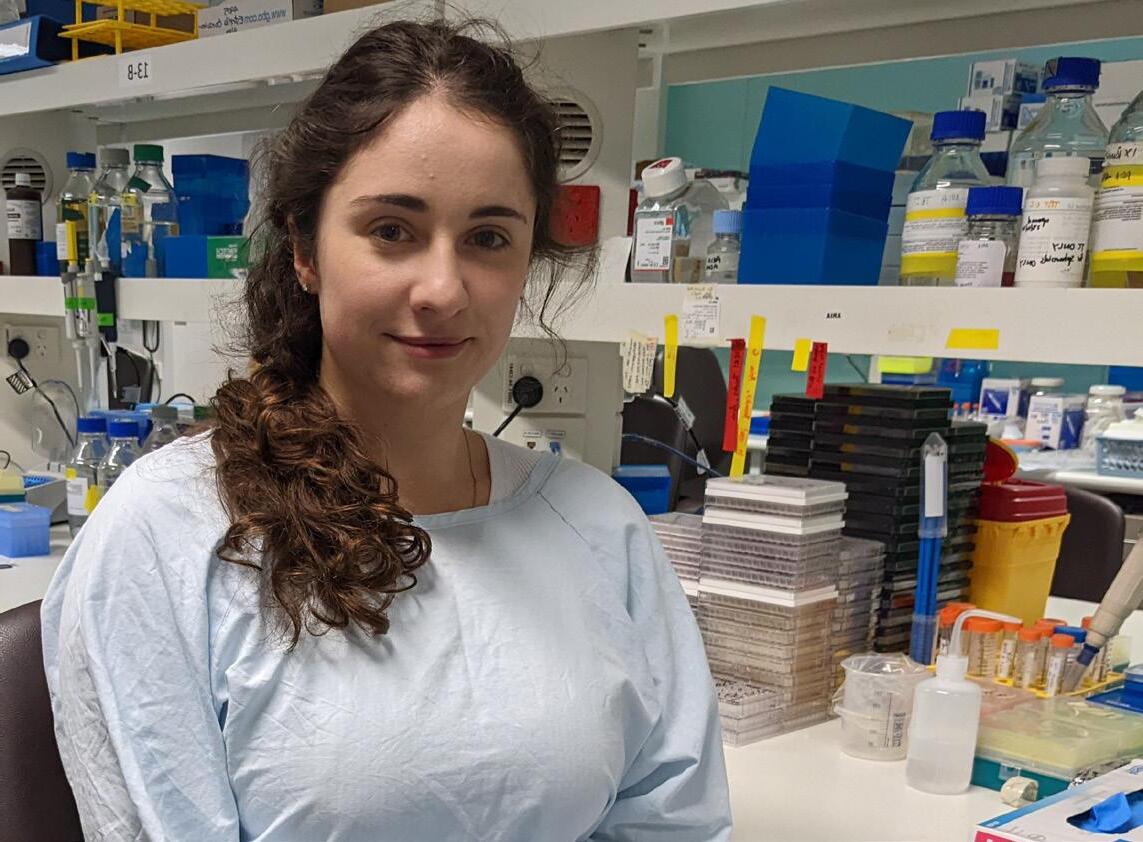

applies Artificial Intelligence to the diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases, whilst also solving technical challenges in the field of Computer Science. Specifically, he is interested in how these algorithms learn to mimic complex human capabilities.

As an advocate of using AI within the medical industry, Isaac is also interested in leveraging these technologies to improve the quality and accessibility of healthcare.

He used his 2020 Fulbright Future Scholarship to pursue these interests via postgraduate studies at the University of Southern California, whilst also exploring how AI research is rapidly applied to industry challenges within the United States.

Born in Russia, educated in China, and now a naturalised Australian, Asia Society Australia CEO, Philipp Ivanov has seen a lot in his travels.

Yet, even for Philipp, spending three months in Washington DC as the Fulbright Scholar in Australian-American Alliance Studies was an eye-opening experience. Read his reflections on the U.S. capital in this letter from DC.

Images: (Above) Danita Delimont/Getty Images; (Right) Steven Heap/Getty Images30 April, 2023

Georgetown, Washington DC

For the last three months I have been on a crash course to understand America.

It’s only the beginning of what I hope will be a long ride to learn about a country as vast, diverse, and complex as the United States. But I am committed–to use an Australian expression–to give it a crack.

I am conscious that I am joining an army of amateur writers depicting their “unique” impressions of places they have “discovered”. So, I won’t be offended if nobody will read mine. It’s simply a record – of an experience that I will forever cherish.

I have been in Washington for almost three months on a Fulbright Scholarship – an opportunity of a lifetime, a reality that I often have to pinch myself to acknowledge.

Boys from Sabaneeva – a rough, working-class suburb of Vladivostok, on Russia’s Pacific coast – do not usually get Fulbright Scholarships or live in Washington. But when they do, they are often star-struck and intrigued. I am.

Star-struck by the understated beauty of the city, its hidden energy, its intellectual life, and its symbols of power. Intrigued and baffled by the contradictions and divisions across political, racial, and socioeconomic lines.

Washington may come across as a bubble within which power, politics, money, and privilege are gained, leveraged and distributed, but as any capital – it’s a reflection of a nation, a beautiful mirror placed in a prominent space with good light, but which stubbornly reveals both beauty and ugliness.

Washington’s beauty shines in spring. I am lucky to be here in the best season, as locals keep telling me. The cherry blossom trees gifted to Washington by Japan are in bloom, transforming the city and drawing huge crowds from around the country.

Ohio Drive Bridge near the George Mason Memorial almost looks like it has been transplanted from Tokyo. I am also fascinated by tulips, appearing everywhere – in backyards and public parks, on the side of pavements and in outdoor pots. It’s exhilarating to see real spring day by day making everything greener and fresher.

After almost twenty years in an evergreen Australia – you come to appreciate the change of seasons.

Gentle and transient blossoms provide a striking contrast to Washington’s colossal and imposing buildings – government headquarters, historical monuments and political and judicial institutions designed to impress and intimidate. They are icons of power reminding visitors and locals alike that they are in the capital of the world’s most powerful nation.

I find striking similarities between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. The sheer bulk of the buildings, the symmetry, the omnipresence of military and war symbols, the wide boulevards, the flags on every spear and gateway, the constant visual references to history – from ancient Rome to America’s own more recent path to global pre-eminence. The signs of imperial glory.

You are in danger of offending your hosts if you refer to America as an empire. After all, its history is a struggle against empires. But there is no better term to describe what America has become since the end of World War II.

An idealistic, messianic, yet ruthless and self-interested leader of a global network of states bound by the sheer weight of American power, interdependence, shared values, and shared fears.

A dynamic economy unrivalled in recent history, which took capitalism, the industrial revolution and a culture of hard work and turned them into a global financial and economic behemoth that even its fiercest rivals are struggling to challenge or escape.

A colossal military power projecting its force around the world, yet with a trackrecord of defeats against much weaker opponents.

To paraphrase Zhou Enlai’s remark on the impact of the French Revolution – it is far too early to write a definitive story of the United States of America. It’s truly a history in the making. And Washington is both its main writer and protagonist.

We are doing a lot of walking, crisscrossing Washington by foot. It’s the best way to see a city. It’s liberating not to have a car and use your legs to explore the place – feel its pavements and grass, underestimate its distances, get lost without google maps, and find surprising spots and corners.

While Washington is painstakingly orderly and neat, as the weather gets warmer a strong undercurrent of street life emerges. Rowers in Georgetown drying their boats and homeless tent cities at the edge of Foggy Bottom. Street artists at Logan Circle and vendors selling knickknacks at Columbia Heights. Nightclubs in Shaw spilling over the pavement, filling the streets with beats and rhymes. The omnipresent smell of marijuana (legalised in the District of Columbia in 2014) on Washington streets is almost mocking the propriety and conservatism of its architectural exterior and elite culture. Aggressive, horn-happy driving. Every capital city is a contradiction, and Washington is no exception.

To the north of the city – another Washington – still edgy and gritty but going through rapid gentrification. We catch my favourite British band – Sleaford Mods in Washington’s legendary 9.30 Club. Their post-punk, electronic beats and hard-hitting lyrics depicting life at the edge of society is a powerful soundtrack to Washington’s northern suburbs.

I am drawn to the city’s museums and galleries – the custodians of richness, depth and authenticity of American culture and history. I grew up in the old world of Russia and China. For reasons of ideology and false cultural superiority, we were never taught America had a history. Yet, American culture has profoundly influenced many Russians and Chinese, especially in the twentieth century as America’s rise was reshaping the world. For me it was music and literature. Salinger and Lou Reed. Iggy Pop and Allen Ginsberg. Jim Morrison and Walt Whitman. I always wanted to see the land that gave birth to them, and in Washington I can finally get closer to the source.

I am most deeply affected by two of Washington’s sources of wisdom. The National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Museum of the American Indian are monuments to the dark sides of American history – slavery, racism, and dispossession.

NMAAHC is one of the best museums in the world. It accomplishes the impossible by pushing you into the depth of America’s history of slavery and discrimination, brutally and brilliantly depicted in the underground bowels of the Museum, only to drag you to the air and light of its upper floors to celebrate the power, diversity and resilience of Black American culture, politics and people.

NMAI takes a different, less dramatic approach to telling a no less bloody and depressing story of indigenous North Americans and their systematic removal by European settlers. You are taken on a tour of major milestones and events of recent American history and how they forever upended the lives of the continent’s original inhabitants.

Both museums are powerful reminders of how central violence has been to our human story, how recent and raw many of our tragedies are, and how fragile and hypocritical many rules and norms that govern our civility and peace remain.

But above all – these museums speak to the honesty of America. They are confronting and sad, yet optimistic and hopeful. Truth-telling is the best remedy against complacency and amnesia. Truth gives us hope that we have learnt from our past and are committed not to repeat it.

Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

My mind turns to Russia. We have never completed, not even properly started our own truth-telling about what we did to each other and the many nations around us during the 1917 revolution, the civil war and Stalin’s atrocities. We are now facing another, no less confronting reckoning in Ukraine, adding a fresh bloody layer to the traumas of the last century.

Perhaps, not confronting our past explains why we find ourselves at war with the world and with ourselves.

Behind the grand facades of Washington beats a pulse of another life – of intense policy debates and ideation. As an outsider just starting to learn about America, I am lucky to be able to meet some of the best minds in the American foreign policy community.

It’s a captivating and rich intellectual world that is hard to find anywhere else on the planet. After all, this is the epicentre of global power. And Washington is naturally hungry for ideas to shape and grow its power and counter its many challengers.

The focus of my time in Washington is think tanks – those strange beasts operating across boundaries of government, academia, media and civil society. With astonishing pace, they are churning out reports, papers, comments and insights on everything that matters to those who rule the country and by default many parts of the global system. Some institutions are hard to penetrate, but most have been incredibly welcoming and open.

I hope one day to write about the Museum of the Soviet Repressions and the Museum of Russia’s War on Ukraine, standing proudly alongside the Hermitage and the Tretyakov Gallery.

And I hope they will be just as unapologetically honest, but also full of hope and empathy as the museums in Washington.

As an outsider on borrowed time, I am grateful for their hospitality and generosity.

I am also rediscovering the sheer joy of listening. After eight years as the spokesman of an institution in Australia, I cherish every moment to stop talking and just listen to others. A friend notes that Washington’s policy circle is like an intensive mini-PhD on the United States of America, with its foreign policy as a foundational subject. It’s impossible to capture the wealth and diversity of viewpoints on where America is or should be headed.

There are threads and subjects that catch the collective attention and then lose it as the next wave of events and ideas come along. It’s easy to be sceptical about Washington’s intellectual life – its egos and motives, the use of expertise of its most vocal inhabitants for their hidden political or career-advancement agendas.

But I am struck by the sheer size and depth of Washington’s policy ecosystem. The flow of experts between government, business, think tanks, academia and media ensures a cross-pollination of ideas and talent. America’s hyperactive and combative partisan politics often descend into circus and shallow posturing, which is harmful to long-term policymaking that is required for the 21st century.

My three months in Washington are punctuated by the ongoing bloody grind of the war in Ukraine and the ratcheting up of tensions between China and the U.S. The spying balloon incident, Xi’s visit to Moscow and the start of America’s election season creates a cascading pressure on Washington to lead globally, without sacrificing an imperative to rebuild the American economy and society after the havoc of the Trump and pandemic years.

The domestic and global challenges facing America are formidable. An uneasy balance of local and international responsibilities has been a constant feature of the American story. This time America is facing two competitors at the same time: Russia is threatening European security in Ukraine and China is challenging America across all domains of power in Asia and globally.

But it also injects a necessary scrutiny and contestability of ideas which keeps policymakers and experts on their toes.

The competitive nature of America is manifested as much in Washington’s foreign policy ideation as in the rowing contests on the Potomac River.

The confrontation with Russia and competition with China has galvanised the American system. Perhaps having a worthy adversary, let alone two is a shot in the arm America needed to reclaim its mojo. Cold war comparisons are again en vogue across Washington. But history does not really repeat, and defining the contest is as important as drawing swords. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the rivalry with China push Washington’s interpreters of the present and predictors of the future towards historical references that can easily catch the attention of the capital’s informed public.

I was struck how alive the memories of the confrontation with the Soviet Union are, and how strong the influence of policy ideas that shaped it – from Churchill’s Iron Curtain to Kennan’s containment.

Behind the grand facades of Washington beats a pulse of another life – of intense policy debates and ideation."Image: Getty Images

But behind the bravado, America and much of the rest of the world also mourn the loss of the two biggest hopes of the late 20th century – the emergence of a democratic or at the very least a benevolent Russia and China. The fact that both China and Russia so decisively have turned against America shows Beijing and Moscow’s own trap of history, the tragedy of great power competition, and the limitations of American primacy. It is undoubtedly hard for America and many of its friends to accept. Yet the world is slowly learning to live with this new reality of fragmentation and conflict.

Yet while America has not been able to shape Russia and China in its image and curtail their ambitions – the future of American power is far from bleak. In fact, some argue that by most measures of power, America’s global pre-eminence is as unchallenged as it has ever been. If this analysis is correct, Washington’s concerns about China are about the changing balance of power, especially in Asia and the emerging multipolarity that both China and Russia are advocating, rather than a reflection of the real erosion of American power. It’s about the rise of others, or more precisely of China, than a decline of America.

And so, Washington’s policy machine is powering on all cylinders. Strategies and reports are flowing. Alliances are formed and reinforced - with India, Australia, Philippines, Japan, Korea and Europe. Politicians, diplomats and generals are on the front foot and marching to defend American-led order. French President Macron’s theatrics aside, America has managed to galvanise transatlantic relations around the cause of Ukraine. America is finally turning its attention to its own capabilities and strengths – from semiconductors to basic manufacturing. Creativity and innovation – fuelled by an open and competitive system – are thriving. Democracy for all its faults and despite many dire predictions is working. One can almost feel the renowned American confidence bursting to the surface in Washington, even as the nation is facing its many internal divisions and the world beyond its borders is far more dangerous and less predictable that what America had hoped for.

To get ahead, America is changing the rules of the global order it created in 1945. The order that served America and its partners so well, but which has also enabled the rise and vengeance of China and Russia.

I was lucky to be a spectator of the speeches by American leaders driving this change. Nothing beats the energy of the room and the orators’ power of conviction. The political speeches are Washington’s soundtrack and its greatest hits.

In Brookings, Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman is speaking after the balloon incident, outlining how America will deal with China. She’s careful not to raise the temperature but clear on America’s commitment to compete with Beijing across all domains of power. In Georgetown, one of the Administration’s best performers – Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo presented by far the most ambitious element of Washington’s policy for China - the Chips Act – a generational undertaking to bring the research and manufacturing of semiconductors back to America. A week before I leave, I am back in Brookings to listen to Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor, who brings together most of the pieces of the U.S.China competition puzzle.

The Administration’s formula - invest, align and compete – is a combination of grand strategy, industrial policy and domestic politics. To compete with China and to rebuild the potency of the American industrial base and its working class, the U.S. is willing to step back from its long-held belief in the untamed power of markets, trade liberalisation, open technologies and globally distributed supply-chains. To win the contest with Beijing, the ultimate geoeconomic power, Washington is reinforcing existing and creating new defence and economic alliances, cutting off access to its key technologies and investing in its own capabilities. It’s “America and allies first” strategy that – in its authors’ conviction – will maintain and extend America’s competitive edge over China.

Only time will tell if this is the right response to China’s rise. In the meantime, U.S. - China relations are spiralling into an unknown by the near absence of dialogue, mechanisms to prevent miscalculations and routine communications between leaders.

Neither side seems to understand, let alone accept each other’s red lines. “Black swan” events and actions by other states, beyond U.S. and China’s control, add another layer of unpredictability.

Whether America and China can compete without sliding into an unnecessary and catastrophic war, dragging its allies and the world at large is a bracing prospect. The stakes for Washington, Beijing, and the rest of the world could not be higher.

“Black swan” events and actions by other states, beyond U.S. and China’s control, add another layer of unpredictability...

The stakes for Washington, Beijing, and the rest of the world could not be higher.

I often forget that I speak Chinese and Russian – only to be reminded when I see an incorrect or incomplete translation taken out of linguistic, political or cultural context going viral on social media, wreaking havoc on facts, only to be forgotten when our collective attention spans crater.

Unexpectedly, Washington has made me reflect on my own identity. What does it mean to be an Australian of Russian heritage? My two homes sit on opposite sides of America’s spectrum of adversity.

is the CEO of Asia Society Australia, the nation’s leading business and policy think-tank dedicated to the IndoPacific region. He is the 2022 Fulbright Professional Scholar in Australian-American Alliance Studies, Funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Philipp's Fulbright project at the Georgetown University Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service mapped out new thinking on digital and global impact strategies by leading U.S. foreign policy think tanks and build a platform for collaboration between U.S. and Australian institutions and their peers in Asia.

Since the cold war, Australia and the U.S. have never been closer, Russia and U.S have never been further apart. In between them - China, challenging America and aligning with Russia. This three-way relationship fascinates me because it creates such a unique mix of borrowing and rejection, confrontation and reliance, interdependence and dissociation, distrust and obsession. As I shake off my philosophising, I promise myself to use my experiences and skills to understand and explain this triangle of nations, intimately connected yet light years apart, openly or covertly confronting each other yet unsure if either of them can prevail. I feel almost responsible to help make sense of it all. Perhaps my identity is an asset. To be yourself is all that you can do, as the lyrics go in my favourite Chris Cornell song.

On my way to America, I was expected to be questioned about my heritage and allegiance. It’s only natural – with my accent and surname and given the volume of horror Russia is exhuming daily.

Yet my interlocutors are polite and interested. Everyone I spoke with distinguish between the Russian state and people. I hope Russians can reciprocate this generosity when thinking and talking about America. I am also struck how pervasive Russian culture is in the U.S. In the sparkling and imposing Kennedy Centre, I watch Russian pianist Daniil Trifonov and conductor Stanislav Kochanovsky performing Scriabin, Rachmaninov and Tchaikovsky with Washington’s brilliant National Symphony Orchestra. Kandinskiy and Malevich are on prominent display at the National Art Gallery. Have they all spawned from the same land that now dominates the news for entirely different reasons? They have. Countries have many faces.

As I count my days before departing Washington, I am soaking up memories, spending as much time as I can in Georgetown that has become my home here. It is an old, almost medieval-looking neighbourhood in the west of the city. Georgetown University where I am based is the heart of the district. Its magnificent Healy Hall dominates the landscape. Students are rushing between buildings or chilling out in wooden chairs on the lawn. The residential area around the University is a grid of tree-lined streets with immaculate brick, stone and weatherboard townhouses, showing off colours and ornaments of their facades and doorways. Tulips in tiny front yards.

Our final chance to see a concert at the Kennedy Centre. We’re lucky – it’s Abdullah Ibrahim, a jazz legend, and a South African icon. He delivers a world-class performance for this worldly city. I will miss this place.

In conclusion, some words of gratitude. To all I have met in Washington who were so generous with their time and wisdom. To the city that was so welcoming and absorbing. To America that I am so looking forward to discovering.

To the Fulbright Program for making it possible. I have always believed in the power of scholarships. On more than one occasion scholarships have changed the course of my life.

I would not have been able to study and stay in China, find my life partner and a new home in Australia 7 years later if it was not for a scholarship to study in China from my Russian university.

I would not have witnessed how China trains its education leaders and later contribute to Australian diplomacy if it was not for the Endeavour scholarship –the brainchild of Australia’s first female prime minister Julia Gillard.

Fast forward to 2023 and I would not have been able to discover America, if in 1945, U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright did not introduce a bill in the Congress that – in the best tradition of American idealism, pragmatism and creativity – proposed to use surplus war property to fund the 'promotion of international good will through the exchange of students in the fields of education, culture, and science.'

80 years later as the world is again facing wars and calamities, scholarships keep generating good will, bringing people, nations and perspectives together –quietly but persistently, outside media headlines and Twitter battles.

And those of us who are privileged to receive them will have a lot to give back to the communities and countries we serve.

- Philipp IvanovI, for one, am ready to give my best.

Lorna Nungali Fejo was 4 years old when she was kidnapped by her government.

Her family, who lived in an isolated desert village in the Australian outback, had heard that the authorities regularly stole Aboriginal children from their communities. They had dug holes into creek banks where kids could hide and practice how to stay motionless. Despite these efforts, one day, with help from an Aboriginal tracker, white “welfare men” showed up without warning and dragged off Lorna and her siblings and cousins, throwing them into the back of an open truck and stealing them from the only home they had ever known. Her mom frantically clung to the sides of the vehicle as it drove away. Lorna never saw her mother again.

Some three-quarters of a century later, on February 13, 2008, Lorna—by then a Warumungu elder known to her seven children, 23 grandchildren, and 14 greatgrandchildren as Nanna Nungala—sat in the Great Hall of the Parliament House in Canberra next to other select members of the group known as the “Stolen Generations.” They were there to hear Australia’s new prime minister, Kevin Rudd, acknowledge that Australians had systematically dehumanized and degraded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and apologize. “We waited a long time for this,” she told The Sydney Morning Herald. “I never thought I’d live to see this day, but I’m here. I’m a survivor.”

For Australia and its first peoples, Rudd’s historic apology was a long-awaited turning point. Widely embraced by Australians as an extraordinary act of contrition, it shifted the country’s discourse around Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in important ways.

For the United States, it epitomized the power of an honest accounting of the past. Fifteen years later, though, it remains an example that no American leader has dared emulate. And though Australia’s approach provides a model for other nations, it is also a reminder that words—no matter how deserving or well received—are only the first step toward lasting justice.

A few days before the apology, Lorna sat with Rudd in person and recounted her traumatic childhood. “The whole reason that she told her story was because she wanted people to understand what the Stolen Generations were about,” her daughter Christine Fejo-King told ABC News. “The lasting impact that it had on the children who were taken, the families that were left behind, and the stain on this country.” Those who were forcibly removed have suffered higher rates of unemployment, incarceration, and health challenges. Rudd’s words recognized this collective trauma as fact, writing the Stolen Generations into Australia’s national biography.

The speech was Rudd’s first official parliamentary act, greeted with watch parties in central squares in major cities, such as Sydney and Melbourne. “Rudd had the madness of courage,” Charles Passi, a former chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation, told me.

An apology like the one Rudd offered is long overdue in the United States. In recent years, federal officials have twice formally apologized to American Indians on behalf of the nation. But the details of these apologies highlight the ways in which they fell short.

On September 8, 2000, while commemorating the 175th anniversary of the establishment of the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Gover delivered a speech owning up to the horrific abuses inflicted on the very communities the bureau was supposed to have protected.

The agency had participated in the “ethnic cleansing” of American Indians, he said, and failed to prevent the “deliberate spread of disease … the use of the poison alcohol to destroy mind and body, and the cowardly killing of women and children”; it then “set out to destroy all things Indian.”

But as heartfelt as the sentiment no doubt was, Gover was not speaking for President Bill Clinton in any official capacity.

Perhaps even more important, Gover is a member of the Pawnee Nation. Rudd told me that his apology worked in part because he is a “white, eighth-generation Australian male whose ancestors were criminals.” Gover, by contrast, is himself a member of the community that had been wronged.

On December 19, 2009, President Barack Obama signed an “Apology to Native Peoples of the United States” into law. Here, in theory, was the presidential apology the nation needed.

But President Obama did not hold an event to mark the moment. The Senate sponsor of the bill, Sam Brownback of Kansas, read the statement aloud in a small ceremony five months later, and it received little news coverage.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that this was intentional.

The American public was not brought into the conversation before, during, or afterward. There was no national ceremony of any kind. Neither a U.S. president nor a major leader from Congress delivered the apology, nor did a representative of the administration even hold a press conference.

In Australia, people pulled their cars to the side of the road to listen to Rudd’s apology. In the U.S., as Brownback later conceded, “nobody knows about it.”

The text was buried in Section 8113 of a Department of Defense Appropriations Act, placed in between a segment of the bill that designated money to the National Guard for a counterdrug policy and a provision requiring any government agency receiving funds by virtue of the act to submit a report thereafter.

The act is 67 pages long, and the apology is on page 45. It didn’t even merit a mention in the bill’s table of contents. (In some ways, the apology echoed a 1993 resolution, signed by President Clinton, apologizing to Native Hawaiians, although that earlier resolution was passed as its own bill.)

An apology requires more than just a signature on a bill if it is to have an impact. The Australian apology had three basic elements: an admission of the wrongdoing, a demonstration of regret and remorse, and a commitment to forging a new future in which the wrongdoing would not be repeated. In the U.S., both the 2000 and 2009 apologies included all three components.

Yet the latter apology also included the following closing sentence:

“DISCLAIMER.—Nothing in this section— (1) authorizes or supports any claim against the United States; or (2) serves as a settlement of any claim against the United States.”

That rider was attached to ensure that no one could bring a legal suit against the U.S. government for its maltreatment of Indigenous peoples, using antiseptic language that watered down the admission of guilt.

In Australia, a great deal of work remains to be done. On the tenth anniversary of Rudd’s apology, Richard Weston, a former CEO of the Healing Foundation, told The Guardian that 230 years of oppression remained “the root cause” of the “disparity between life expectancy” that “feeds into all of the social and health problems in our communities, like violence, like poor education outcomes, [and] poor employment outcomes.”

Rudd’s apology was a necessary start, but not a solution to these problems. “For a lot of people the apology was viewed as a finalisation of something,” Ian Hamm, a member of the Stolen Generations, said to The Guardian, “whereas for people in the Aboriginal community, particularly for stolen children, it was a beginning.” Rudd himself shares that view.

Earlier this year, on the 15th anniversary of his apology, he rated it both a success and a failure. “Let us have the honesty,” he said, “and the courage to acknowledge both.”

True progress for Indigenous peoples—in both the United States and Australia— requires reckoning with the past. The U.S. must confront its founding sins, including the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and use restorative justice to address them. Any solutions need to be shaped by Indigenous Americans themselves. But a national apology would be the first major step in finding a way forward.

- Aaron J. Hahn TapperThis article was originally published on the website TheAtlantic.com and is republished here with The Atlantic's permission.

TAPPER

is a professor of Jewish studies at the University of San Francisco and author of the forthcoming book, We Are Sorry for Stealing Your Children and Killing Your People: Apologizing for the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Australia and the United States.

Aaron's 2014 Fulbright Scholarship to the University of Melbourne and Monash University focussed on issues around reconciliation and forgiveness, focusing in particular on the Apology made by then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in February 2008, when he formally apologized to the country’s indigenous communities for their prolonged maltreatment.

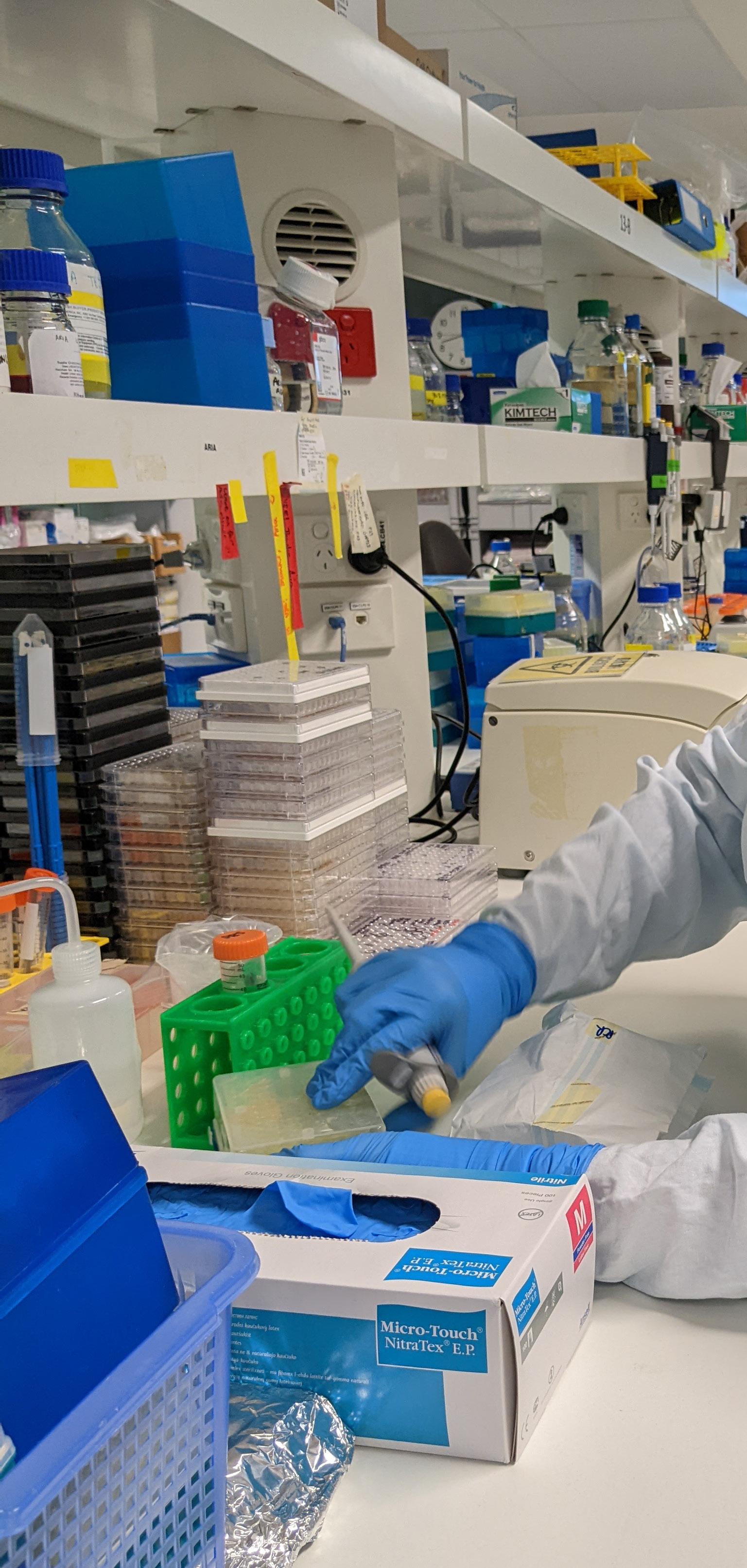

As a PhD student in the Raston Lab at Flinders University I spend a lot of time imagining I am a little molecule moving around very fast as I observe clear liquid spin around in a rotating test tube.

In the Raston Lab, under the guidance of Professor Colin Raston, we look at how we can use chemistry to tackle this big, often invisible, challenge. The technology we use to do this is called a Vortex Fluidic Device (VFD) – imagine a test tube that is rotating at speeds of up to 9000 rotations per minute. Professor Raston developed this technology in 2013 and over the last decade members of group have established diverse applications for the VFD in medical and pharmaceutical research, controlling chemical reactivity, food processing among others.

The overarching goal of the work we do is to improve chemical production, making it cleaner, greener, and cheaper. In green chemistry this can be termed ‘benign by design’.

The VFD is a type of flow processing or microfluidic reactor, which is a term that can be given to processing which occurs in thin films. Other types of reactors which occur under flow are channel-based fluidics such as ‘lab-on-a chip’ devices, and the ‘spinning disc’ reactor.

Compared to conventional batch processing, often using the ubiquitous round-bottom flask, microfluidic processing has the advantages of increased heat transfer and increased collisions between molecules. Processing under flow is also high in ‘green chemistry’ metrics – through reducing reactants required, increasing yield and the ability to monitor reactions in real-time.

The world rushes by in a blur and I feel myself being tumbled in a high-speed waterslide spiralling down towards a violent crash on the surface, trembling as I collide in activation zones again and again, breaking old bonds and forging new ones.

The true nature of chemistry is often unseen, which is fascinating and inspires my imagination. As I write this, the concentration of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere is at 412 ppm and is rising. Although we cannot see the carbon dioxide and methane floating up into our atmosphere, the resulting climate change is an ever-pressing challenge moving forward for our planet.

The VFD, which processes liquid solutions at a 45° angle has several advantages over other microfluidic devices through reducing clogging, increasing collisions, and beyond diffusion control processing. It is an exciting time to be a researcher on the VFD in the Raston group as each year we learn more about patterns in the fluid flow that enable us to control the chemistry.

My Fulbright research in America at University of California Irvine (UCI) with Professor Greg Weiss goes back to the core of what drew me to research which is the chance to make a difference to society through contributing to reducing emissions. Using the VFD we hope to demonstrate a method to close the carbon cycle loop, by reusing waste carbon dioxide gas and carboxylic acids as chemical feedstocks.

My project grows on previous collaboration between the two lab groups whichwon a 2015 IgNobel Prize for ‘unboiling an egg’.

This essentially involved “refolding” proteins using the VFD, which is quite an incredible process, and invaluable for certain applications in the pharmaceutical industry.

Previous work involving group member Dr Xuan Luo, now a Postdoc in the Raston group, and Dr Joshua Britton, showed the acceleration of a variety of other enzymatic reactions using the VFD. My project will build upon their work using a patented engineered enzyme prepared in the Weiss Lab, as well as adding new understanding into how magnetic fields affect fluid flow in the VFD – a big part of my PhD.

At UCI, I hope to achieve a proof-ofconcept demonstrating a recycling system for carbon in the VFD. A key part of the research will involve investigating possible methods to optimise the experiment through systematic testing with the aim to enhance the enzymatic activity of this process in the VFD.

Ultimately the end goal is an industriallycompetitive process. This project is at an opportune time as we collectively work towards sustainable solutions to climate change so that future generations may experience the world free from the devastating consequences of global warming and environmental degradation.

- Zoe Gardner

is a PhD researcher at Flinders University who is passionate about how green chemistry techniques can be used to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

As a Fulbright Scholar, Zoe will work with her collaborators to research a process for enzymes to break down waste chemicals using a cutting-edge technology, the vortex fluidic device, as well as specific enzymes which have been enhanced and prepared for this purpose. In the future Zoe hopes that her research can contribute to closing the carbon loop in chemical processes and be part of a solution to one of the biggest challenges facing humanity today.

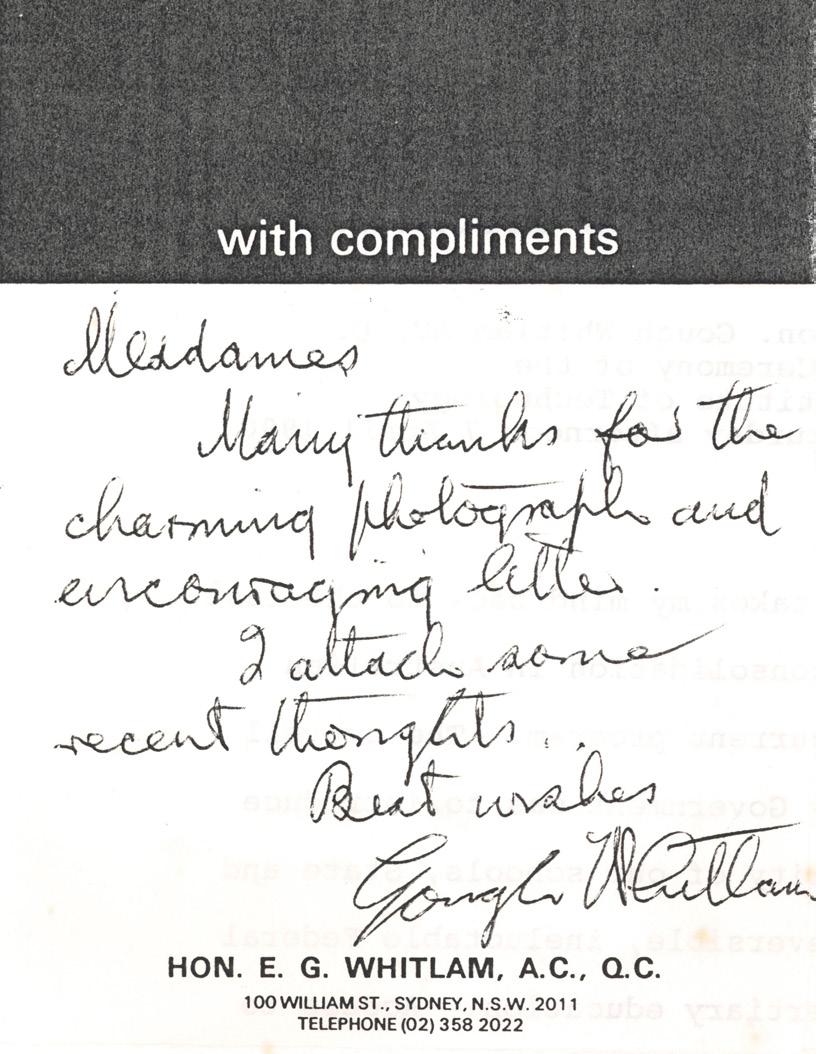

Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam considered his education policy reform program to be the “most enduring single achievement” of his threeyear government.

Whitlam saw education as a public good, the animating force of an equal society and a healthy democracy.

This philosophy drove his decision to abolish all fees for tertiary study in 1974, paving the way for fifteen years of free higher education in Australia.

Although the statistical impacts of Whitlam's education policy were mixed, it’s hard to overstate its cultural resonance –particularly for Australian women. Whitlam’s personal papers, housed in the Whitlam Institute’s Prime Ministerial Collection, contain dozens of letters and messages from women who felt that free tertiary education opened doors for them and for their families that would have otherwise remained closed.

The Australian higher education system reached student gender parity in 1987, and women now outnumber men at Australian universities.

But the women entering the Australian higher education system today encounter a dramatically different landscape than the generations of women who came before them.

University fees were reintroduced in 1989 and have risen since, along with student debt levels.

Reduced government funding has pushed tertiary institutions to compete for students and research grants, cut staff and casualise positions, and corporatise functions.

“When you made universities accessible, I was a young mum at home, light years away from being able to afford university fees and lacking in any conviction that I was deserving of a university education…

By Una Corbett

By Una Corbett

These changes uniquely and disproportionately impact women.

Whitlam himself said that the “overarching principle” and “unifying theme” of his public work could be stated in two words: “contemporary relevance.”

2022 marked fifty years since Whitlam’s election.

This milestone prompts us to consider the immediate and intergenerational impacts of Whitlam’s education policies.

But anniversaries aren’t just moments to reflect: they’re opportunities to look forward.

This year, as the new Albanese government convenes a Universities Accord intended to “drive lasting and transformative reform in Australia’s higher education system,” it’s critical that the voices of Australian women in higher education – over the past fifty years and today – are at the forefront of the conversation.

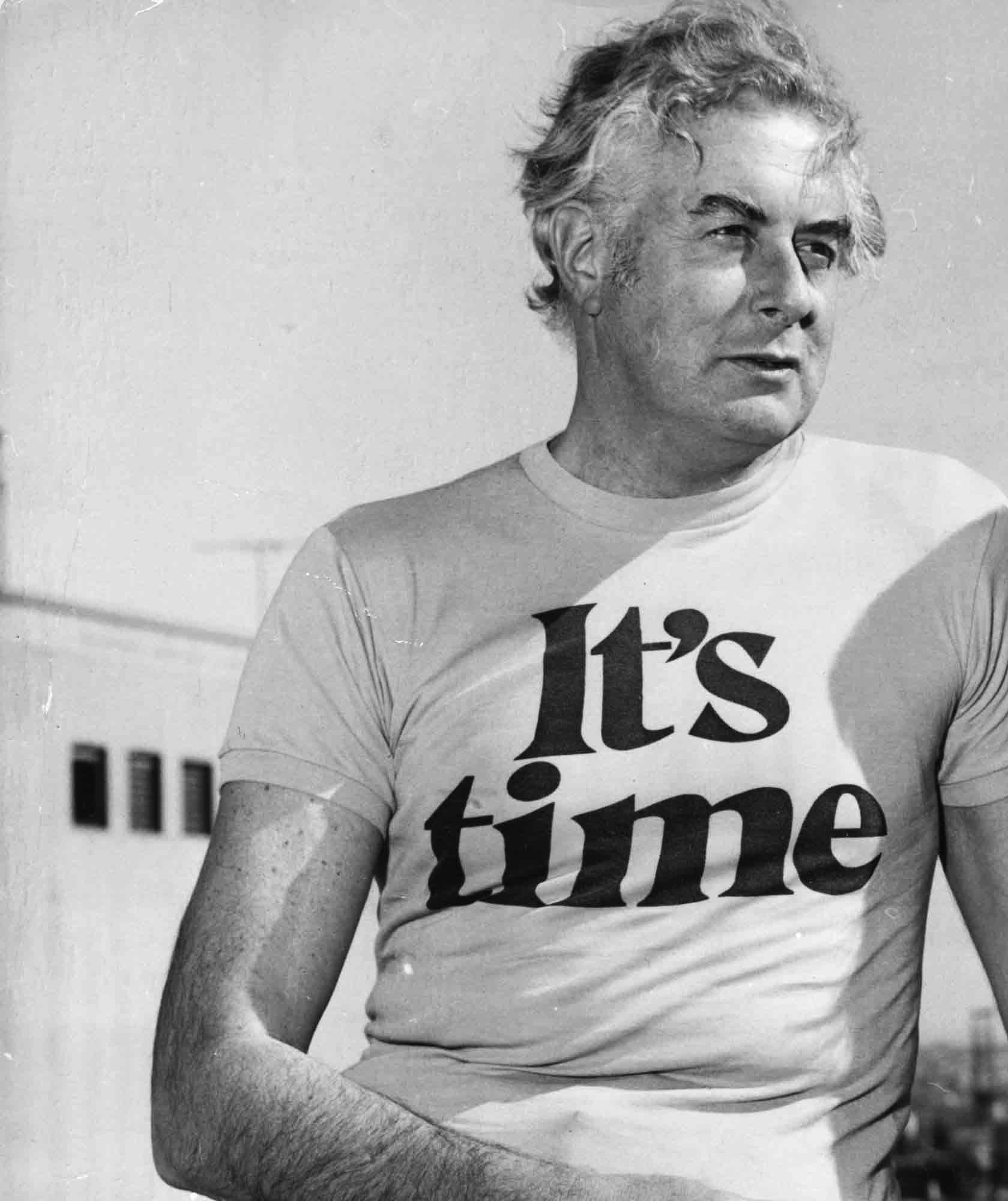

Looking back now I see my university education as a turning point in my life…"Image: Gough Whitlam with Australian singer, Little Pattie (Patricia Amphlett) during Labor's 1972 election campaign. "It's Time" was both a song and the political slogan that took Gough Whitlam's Labor Party to victory. Graham Fletcher/Getty Images.

For my Fulbright research at the Whitlam Institute at Western Sydney University, I analysed qualitative data from two sample groups: women who experienced fee-free tertiary study under the Whitlam reforms, and women pursuing tertiary study today.

For sample group #1, I conducted textual analysis of letters and messages in the Whitlam Prime Ministerial Archives, drawing connections between Whitlam’s policy reforms and the affective experiences of the women who lived them. For sample group #2, I interviewed 16 Australian women who are higher education students today.

Interviewees were asked to reflect on their journeys to university, how they felt about their time there, and their experiences with fees and debt.

They spoke about why higher education mattered to them and what changes they might make to the Australian higher education system, given the chance.

I analysed interview transcripts to distil key themes and map continuity and change from the Whitlam era to today.

The following is a summary of my findings, from a Whitlam Institute legacy paper to be published in 2023.

1. Women who attended university for free post-Whitlam reforms expressed that free tertiary education helped them escape poverty, achieve economic mobility, and succeed professionally.

2. More intrinsically, free tertiary education was a route to selfactualization and what one woman called “spiritual independence.”

3. Women felt their tertiary study allowed them to give back to their communities and contribute to social good

4. Women cited how their educational achievement led to intergenerational advancement and success for their families. But they criticised how today’s tertiary students don’t have access to fee-free study, a policy shift that these women felt was limiting the opportunities of the next generation.

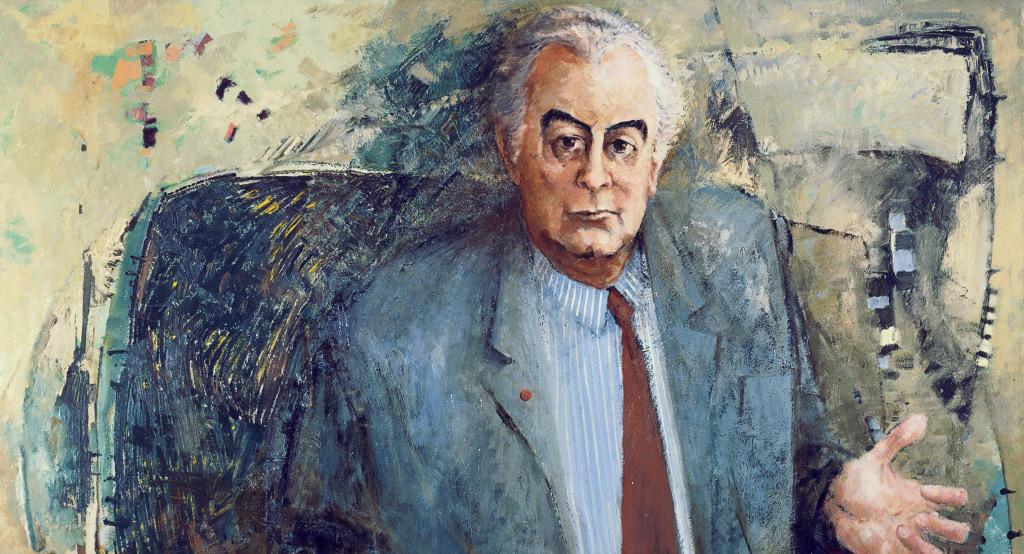

Images: It's Time campaign leaflet on Education, item 38632, Whitlam Prime Ministerial Collection, Whitlam Institute; (above right) Clifton Pugh's Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Gough, 1972, courtesy Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra

“Without the introduction of free tertiary education, I would never have been able to go to university nor adequately support my children after my husband left me unsupported.

“Thank you Gough for what you did for Australia and especially women in the 70s. What you did with education gave women so many more options and I and many of my friends took advantage of free university education.

It is a shame we do not value education the same way today.”

Key Themes From Interview Sample

1. Current students who expressed satisfaction with their university experiences pointed to student body diversity, strong student support services, a sense of belonging to a community, and a perception that the university facilitated strong workforce connections.