NOMINATIONS OPEN

MONDAY 30 JUNE

NOMINATIONS CLOSE

FRIDAY 1 AUGUST

BALLOTS OPEN

MONDAY 18 AUGUST

BALLOTS CLOSE

SUNDAY 31 AUGUST

ELECTION RESULTS ANNOUNCED

FRIDAY 26 SEPTEMBER

NOMINATIONS OPEN

MONDAY 30 JUNE

NOMINATIONS CLOSE

FRIDAY 1 AUGUST

BALLOTS OPEN

MONDAY 18 AUGUST

BALLOTS CLOSE

SUNDAY 31 AUGUST

ELECTION RESULTS ANNOUNCED

FRIDAY 26 SEPTEMBER

Kia ora e te whanau, and a very belated Mānawatia a Matariki! I hope you all had a lovely break, or at the very least made a bit of cash to get yourself through the next semester. This year, Matariki passed on the 20th of June, allowing the past month to be filled with reflection and planning for the year ahead while working on this issue. We’re absolutely stoked to be back on your stands around campus, kicking off with an issue dedicated to Te Ao Māori and the relevance Matariki has to Aotearoa in 2025.

I’ll let Hiri, our Te Ao Māori Editor, introduce the issue from here - but before I go, I want to give a quick haere ra to our wonderful news editor for the first semester, Evie Richardson! RNZ is lucky to have stolen her from us. I’m stoked to introduce Mila Van Der Plas as our new News Editor - she can be reached at vdplasmila@ gmail.com.

Mā te wā! - Liam

Nga mihi nui kia koe Liam, kia ora e hoa ma!

Ka tahi, a belated Mānawatia a Matariki to all of you. Whether you went up the maunga in the early hours of the morning to see the stars in all their glory or simply enjoyed a little sleep in due to the new-ish public holiday, I hope you’re all using Matariki as an excuse to recover, reflect and renew some energy to get through the rest of 2025. Considering all the intense world events happening nowadays, it feels right to really hone into our wairua in these lessthan-ideal times.

For our international student whanau or anyone who isn’t too sure what Matariki actually is, let me give you a quick rundown. Matariki is the official start of the New Year based on the Māori lunar calendar, and is marked when the Matariki constellation graces the skies. There is some debate on the myth attached to the cluster, with uncertainties around whether there are seven stars or nine. If you’re interested in researching the myth more, I highly encourage diving into google and visiting different Iwi information sites. My iwi, Ngāti Maniapoto, celebrates the Seven Sisters, but growing up in Tāmaki Makarau, I heard both. Star count aside, this holiday gives tangata the chance to rest, reflect and remember those who have passed on. An opportunity for celebration, connections and whanau. It’s honestly my saving grace in the year, as by the time Matariki swings around in June, all New Year's resolutions have been squashed and I am usually burnt out. Next time you get a chance, see if you can join any iwi or local community Matariki events, it is such an ataahua time.

On a more sour note, it is hard to enjoy all of our usual cultural traditions and celebrations while the government is actively trying to make our lives worse. Amidst strife overseas, tragedy in Palestine, tension in the US (although, with the orange dictator having the proverbial keys to the kingdom, is anyone truly surprised) our gov-

ernment seems to think the best way to move our country forward is to engage in a rich white circle jerk while starving the rest of the motu. Grocery prices are at an all time high, my faith in humanity is at an all time low, and certain politicians seem to think they live in a completely different century.

Throughout everything, I try to keep my political opinions as an open space, encouraging korero instead of arguments. However, in recent years it has been difficult to look past the politics that are full of injustice and harmful to our community. I recognise that not all of our readers have the same views, beliefs, or problems, but I implore everyone, no matter what your personal outlook on life is, to look out for the little guy. Oppose bills like the Regulatory Standards Bill that threaten to undo the sacrifices Māori made to get our country to a place of peace. Support movements against companies that are actively funding (or causing) genocide. Korero with those who have differing opinions to you- find out why people vote a certain way and keep your mind open. My Te Reo column Kotahitanga has been introduced this year to do just that, and I thank each and every one of you who has taken the time to listen to me yap.

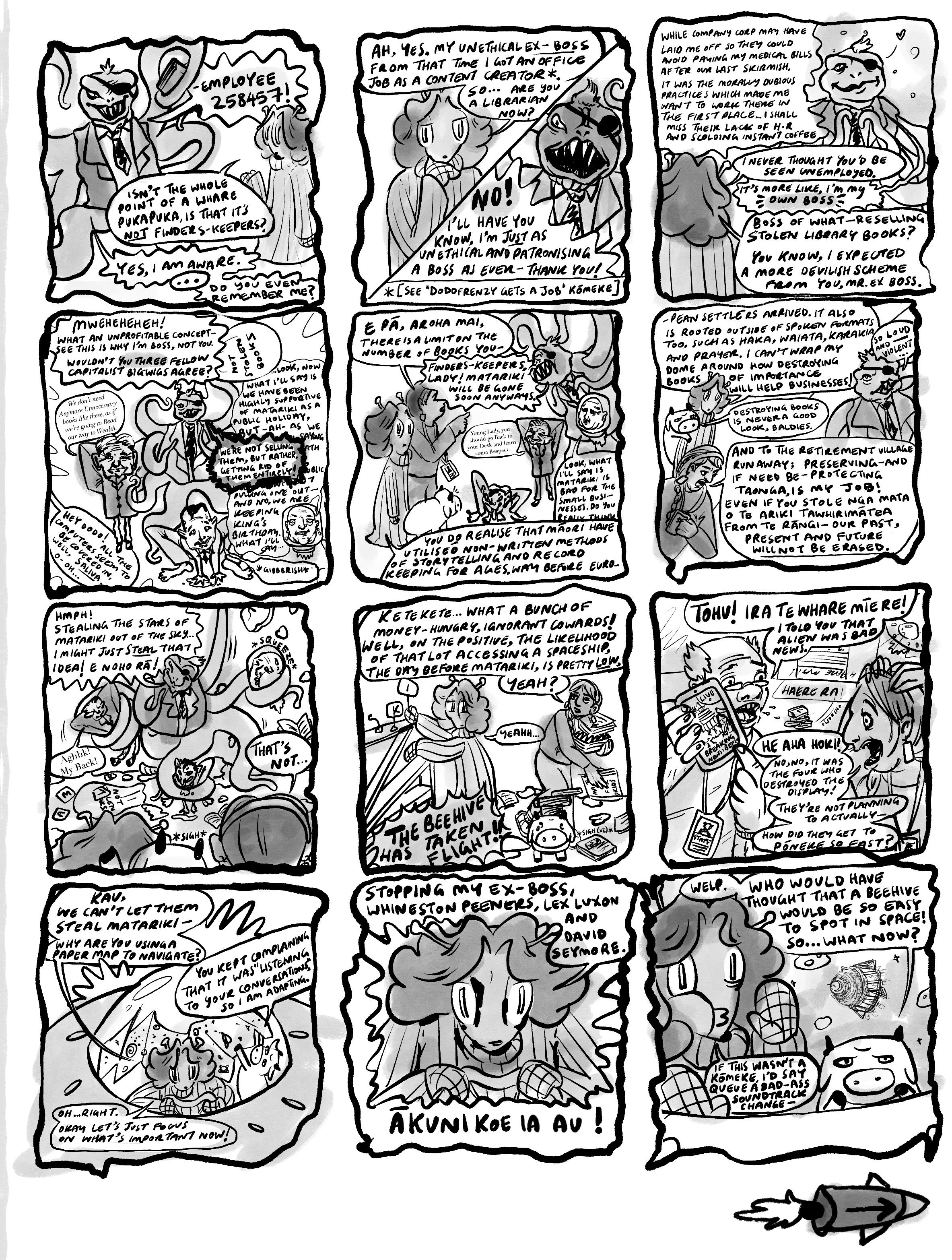

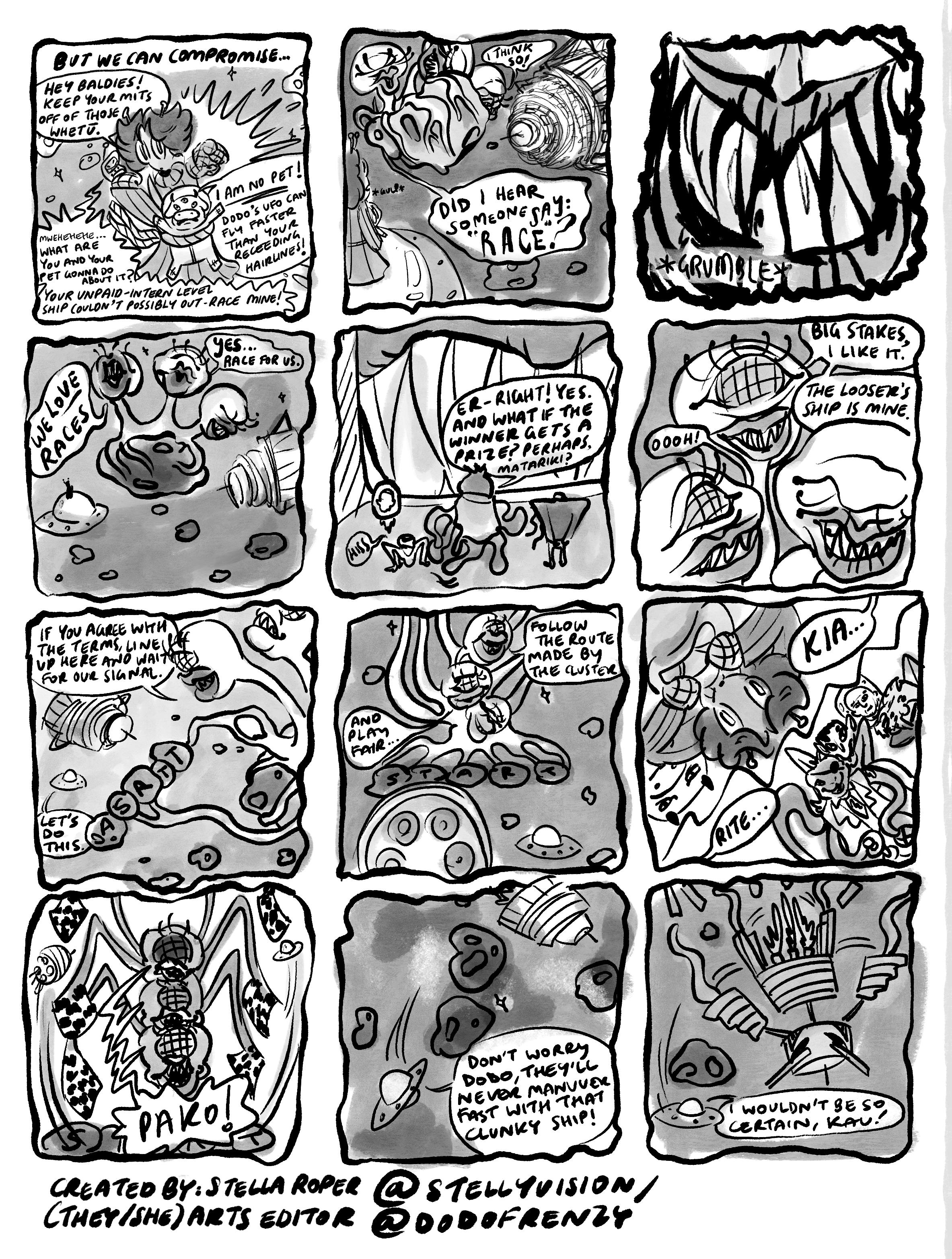

I don’t know how Liam consistently writes such great editorials. I feel like I just want to korero more and more with all of you, but I’ll save that for my other pieces throughout the issue. We’ve got some great entertainment for you once again- Ricky Lai is back at it AGAIN with some Matariki Movie reccs (if you don’t follow him on letterboxd, you’re really missing out - it’s an absolute highlight for me every time I log a film), new and old contributors alike feature with interviews, opinion pieces and general gossip, I discuss the intricacies of the Aotearoa Music Awards and Dodofrenzy is up in the stars (with a cow..?)

This issue is stocked full of great pieces, so go ahead and get stuck in. Go on. Do it. Right now. Go. Shoo.

Mā te wa e hoa ma x

Guest Editorial Written by Hirimaia Eketone (they/them) @hiri_music

TE AO MĀORI

EDITOR

Foreword Written by Liam Hansen (they/them) @liamhanse.n EDITOR

By Stella Roper (they/she)

@dodofrenzy

ARTS EDITOR

Written By Hirimaia Eketone (they/them) @hiri.music

EDITOR

Tena koutou katoa,

Nau mai hoki mai ki te putanga tuawhitu o te rarangi Kotahitanga!

Kia ora e hoa ma, welcome back once again to the Kotahitanga column. Mo te rā, let’s dive into some common reo used around Matariki and the new year!

First and foremost, Matariki is much more than simply a celebration of the star cluster. As mentioned in my editorial, Matariki is a time for reflection, whanau, celebration, and new beginnings. Whether you chose to celebrate the holiday itself, or just enjoyed an extra day off, we can all use this momentous occasion to shift our thinking half-way through the general calendar year.

There are a couple of phrases that are particularly useful around Matariki. Though it has since passed, use these simple phrases next time the opportunity rises!

• “Mānawatia a Matariki” - Celebrate Matariki

• “Ka mua, ka muri,” - Walk/Follow the footsteps of those who came before you (used as encouragement)

• “He waka eke noa” - We’re all in this together

• “Whakapau kaha ki te whai i te ao hurihuri”- Be strong in pursuing the ever-changing world

On a more serious note, it is important to acknowledge the state of the ao around us. I know that for many, the global strife at the moment is heavy on our hinengaro, making it hard to process anything other than the worry and dread of what is to come. It is in these times that I implore all of us to focus on the things that matter most to us. Seeing friends and whanau, advocating for those who cannot and living our life to the fullest, no matter what the government has to say about it.

Use these phrases as endearment, empowerment, and encouragement. Continue to reap the benefits of filling your kite with reo, culture, whakapapa and light.

Until next time e hoa ma,

Mā te wā!

A friend of mine recently had an earth shattering two day talking stage. For lack of any better judgement (or any good judgement at all), she decided to date outside her type. After a slew of androgynous, metrosexual, carabiner LARPing men, it was time for the straight woman's favourite accessory; a man in finance thinking that this would lead to something stable, sensible and longer than a week. Oh how she was wrong. It turns out, “I think you’re pretty” is code for, “if I see you in person I won’t acknowledge your existence.” “I want to take you for dinner” actually means “never speak to me again.”

Another friend of mine was ghosted by someone whose romantic relationship had emerged from a years long platonic courtship. They had spent their real, grown-up money on each other, flying between Auckland and Wellington, intertwining their friendships, and talking about their future. Then, on an unassuming Tuesday, he disappeared without a word. For all we know, he could be dead. Their relationship was a nebulous reverie which left her wondering if it ever happened.

Mixed messaging seems to be common practice in the modern dating world. People will share intimate moments, such as shaving someone’s back, and right afterwards say that they don’t want anything serious with you. Or saying that “you’re the kind of girl I would marry, but I just can’t date right now” - despite continuing to treat you like a partner. Words are the empty seducer of us all.

The dissonance between what people say and their actions continues to grow. Honesty and vulnerability are now absent from the norm. The unknowable quality of person meaning that the other person never really understands them, or what they want. A preventative measure to refrain from getting hurt it seems that people look at dating more as need fulfillment more than anything else. An infinite guessing game, where there are no winners, just confusion and heartache.

You could excuse this kind of behaviour to pure confusion. Most of us in our late teens and early twenties have more important quandaries than the ones posed by our love lives. Study, our career direction, friendships, and, you know - the small objective of figuring

out who we are as people, usually dominate. Between those competing priorities, the interest of another person is the least of our concerns. A long and committed relationship complicates a life that is already difficult to keep above water.

Dating apps seem to add another layer of complication. The promise of something new, something better is all too tempting. With each new swipe, an opportunity arises to improve upon what you’ve already got, even if you’re already happy. It’s dating on steroids, and most have an addiction problem. So we enter relationships, playing at commitment, only to get bored and move on to something new. Seeking instant gratification the same way we scroll through Instagram. Promising just enough to maintain the interest of someone else, without any of the follow through.

That’s not to say that I’m against short-term or casual relationships. I personally don’t think I could handle something for more than a week before getting overwhelmed and calling it a day. But what I am against is dating unethically. I don’t know if you know this, but lying and treating people badly isn't nice and you really should try and avoid it.

Also, people make mistakes. People fall in and out of love, as quickly as someone can bounce on a trampoline, and that’s not a crime. But telling them kindly and with respect for other human beings' feelings is always important. Communication, rather than ghosting is usually best practice. Usually.

You also just meet bad people who sometimes masochistically hurt others to feed their own egos. Enough said. With these types running amok, It’s hard not to become nihilistic. If you can’t trust words, or actions, what’s left? It seems that even when you are upfront about what you want, things might still end in turmoil.

For me, it seems the trick has been to stay away from it all together - recently, anyway. Getting caught up in the romantic subplots of your life by thinking about every little interaction and inflection may be overwhelming to the point of domination. Other people are unexpected and out of our control. I find treachery in placing the health of my mentality in the hands of a good-for-not-much situationship.

But we can’t always be boring, can we? Someone has to play the character in the stories we tell over Friday evening beers. Another way to cope with turbulence on the plummeting plan that is my love life is by looking for the warning signs. Try and objectively assess communication, without getting caught up in your feelings for the other person. Sometimes just the awareness that it might not work out, or that you may end up hurt, is enough to prevent getting ahead of something before anything happens.

And if that all doesn’t help, hey, - sometimes the drama of it is fun. The dating world’s a stage, and all of us merely players, or whatever that Shakespeare said. Some people make careers out of it, like Carrie Bradshaw or Dolly Alderton. Reveling in the ecstasy of retelling your last week’s escapades with your nearest and dearest is, in all honesty, more fun than the actual relationship. Just know at the end of it, there’s a Friday night with your name on it when you can inappropriately crash out at your local bar and the pained cries of PJ Harvey and the wistful chorus of ‘Nobody New’ by The Marias (or any sad girl music of your choice) is far more satisfying after the most crushing relationship of your life. Great things to look forward to!

Written by Elle Daji (she/her) @elleelleelleelle_ CONTRIBUTING COLUMNIST

As an aspiring musician, it pains me to admit I’ve never really paid close attention to the Aotearoa Music Awards, or any type of NZ music award really. It’s only been in recent years when friends of mine have started being nominated that I’ve decided to tune in. Amongst a rush of consistent media that is shoved in your face from every possible opening, I’ve never felt a particular pull to awards shows as a whole. Hell, I’ve never watched the Oscars or the Grammys. Heoi ano, it was safe to say heading into the Aotearoa Music Awards as a journalist was a layered and complex experience. So whether you’re a seasoned veteran of these awards, an occasional dabbler or a fresh-faced newbie like myself, come along as I report on the happenings of the since-passed AMA’s.

Nothing can truly prepare you for the absolute RUSH of a red carpet. Sure, our humble showing at the Viaduct Events Centre was nothing compared to award shows thrown across the world, with all the millionaires dressing the part just for the fun of it. Nevertheless, the nominees were dressed to the absolute nines as they sauntered down the carpet towards the hungry array of radio stations, news reporters and scared Debate Magazine journalists. Everyone wanted to know how everyone else was feeling, what to expect from the performers of the event and who was wearing what. Personally, my favourite outfit (which was difficult, considering the absolute fashion show on display) was Stan Walker’s ataahua ensemble designed by Morghan Ariki Bradshaw, representing Ōtautahi’s clothing label, FUGAWI. Walker’s face lit up when I asked him about his outfit, even though he’d likely been asked the same question a million times before me. He wore his kākahu with such mana and pride that it was hard to draw your eyes away from him.

In a similar vein, I’d like to give an honourable mention to the talented Vera Ellen, who, after winning the 2022 Best Alternative Artist Award at the AMA’s (among other very notable achievements in recent years), was nominated once again and came to the event dressed to impress. Vera’s stylish silver two piece paired with a crocheted fishnet-looking hood was absolutely serving cunt. If I had more time, I would’ve loved to talk to her more about the inspiration behind the outfit, though I’m willing to bet that is just how she dresses on the regular. Oh, to be blessed with fashion talent.

The actual awards themselves were good. There was no winner that was incredibly polarising, nor did I feel like anyone was particularly robbed. To be completely honest, as much as I enjoyed basking in the elegance of the night and celebrating the best of the best, my most memorable moment from that night was talking with the artists face to face about unrelated things. 2025 Taite Music Prize recipient and newly Best Electronic Artist MOKOTRON spent a good portion of the night deep in korero with me about whanau, kaupapa, Māori waiata and his plans for the night. When asked what Matariki meant to him, he responded, saying, “It’s recently become way more mainstream through kura. Like, I only did my first celebration of Matariki 22 years ago, but now everyone is joining the early morning kaupapa … I think, you know, people know that your spirit moves early in the morning around 4 am. There's something about getting up early, the emotions are intense, even just seeing the smoke from the hangi rise into the starry sky, it gets you, eh?”

The emotions of the night were as intense as could be, with Mokotron taking out the well-deserved win for the Best Electronic Artist category. When I caught up with him afterwards, humble as ever, he expressed his thanks to those who had helped him on his

journey and emphasised the need for more Māori artists in the field.

“Don’t follow in my footsteps,” he joked, “just do the thing that’s in your heart and pursue it relentlessly…” “ . If you don’t fit in, then you’ve got no one to compete with, you know?”

Stan Walker seemed to echo a similar sentiment, pushing for the up-and-coming artists to be recognised, rewarded and encouraged “As grateful as I am, you know,” Walker said, “I’m glad it’s shining a light on the younger artists who are starting to break through. We need more of that.”

These sentiments were evident even in the categories, with seasoned and fresh nominees across the board, in every genre. I am always quick to criticise when the same people get awards over and over again, as it isn’t as if Aotearoa is lacking in musicians to celebrate. This year's spread felt right, felt fair. Sure, there were some awards I didn’t fully agree with, and yeah, there were absolutely some more local heavy hitters who weren’t nominated. A judging panel is never going to fully agree nor satisfy the eager audience, so for that, kia ora Aotearoa Music Awards, you did well.

In not-so-short, the awards this year were a great time to celebrate our local music scene and schmooze with the important people in the industry. Congratulations to all award recipients and apologies for not spending much time on the actual award winners. However, I’m sure by the time this goes to print, you’ll have the list of stars memorised. Massive shout-out to the organisation team at the AMA’s as well, because keeping your cool amongst malfunctions, delays, and the general stress of the night is no small feat and deserves recognition.

If you take one thing away from this AMA review/conversation piece/yap, it should be the confidence to Do Your Own Thing. Be bold. Be brave. Do things because your heart tells you to, not because society does. The only way we can continue being the least bit interesting is by celebrating the things that make each of us unique.

Written By Hirimaia

In 2022, something historic happened in Aotearoa. For the first time in our modern history, the entire nation stopped to acknowledge Matariki, the Māori New Year, as an official public holiday. Fireworks lit up winter skies, social media filled with images of stars, and workplaces shut in recognition of something genuinely different. Yet beneath this milestone lies a question: are we really embracing what Matariki could mean for us, or are we just treating it as another day off work?

Matariki isn't just another holiday. It's a completely different way of thinking about time, a period to remember, reflect, and have a fresh start. For generations, Māori communities watched for the rising of the Matariki star cluster in the depths of winter to mark the beginning of their new year. When those stars appeared, it was time to come together, to grieve for those who had died, to share food, to be thankful for what they had, and to make plans for the year ahead. Each of the nine stars means something different, connecting people to their environment, to the elements, and most importantly, to each other.

Making Matariki a public holiday is definitely a big step forward. It's a public acknowledgement of mātauranga Māori, Indigenous knowledge that has kept communities strong for over seven centuries. This recognition brings Indigenous stories, seasonal rhythms, and spiritual reflection into our national conversation, giving a country still working through its colonial past a chance to move forward with a commitment to bicultural respect. However, we can't just stop at the symbolism of it all.

There's a real risk that Matariki could get watered down into becoming just another capitalised holiday. We've seen this happen before: te reo Māori used in marketing campaigns without any genuine understanding, Māori designs slapped on corporate posters without meaningful engagement. If Matariki becomes just another long weekend for booking Airbnbs or fuelling our shopping addiction, we miss the chance to engage with what it really means to us.

Real celebration of Matariki means more than just changing the calendar. It asks us to live differently. It challenges us to slow down, to honour those who came before us, to strengthen our connections with family and community, and to take better care of our relationship with the natural world. These aren't just Māori values, they're human ones, and we desperately need them in our world of burnout, disconnection, and environmental crisis.

If we're serious about making Matariki meaningful, we have to start with education. We need to go beyond token lessons in schools and ensure young people understand the whakapapa, the family connections, of the stars, the cultural practices around them, and what they really represent. Teachers need proper support and resources to bring this to life in classrooms, not just during Matariki week, but throughout the whole year.

Beyond schools, our institutions and all of us as individuals need to reflect Matariki's core values in how we actually live. Rest should be valued, not punished. Community wellbeing should come first. Time to gather and reconnect shouldn't be seen as lazy or indulgent, but as essential for our social health. Matariki reminds us of cyclical living, of paying attention to the seasons, of letting go of what doesn't serve us, and of beginning again with purpose. What would happen if we carried this energy into how we structure our workplaces, our policies, our public spaces?

Research keeps showing us how important cultural rituals, social connection, and collective reflection are for our well-being. Matariki has all

of these things built in. It creates space for grief, joy, reflection, and vision. It's a culturally grounded approach to wellbeing that's been around for centuries, long before Western psychology came along.

Matariki can also be a bridge between generations, between urban and rural communities, between different cultures. Celebrating it encourages national unity without forcing everyone to be the same. It strengthens the social fabric of Aotearoa by building mutual respect and shared understanding rather than trying to make everyone assimilate.

But we can't let this be where we stop. Making Matariki a public holiday is a beginning, not an end. The visibility needs to be followed by a deeper understanding, and the recognition needs to be backed up by real action. That means supporting Māori voices and leadership, protecting te reo Māori, weaving Indigenous knowledge into our institutions, and calling out empty gestures when we see them.

Matariki, after all, is a constellation. It's a cluster of stars whose power doesn't come from any single star but from them all working together. That's what we need to aim for: growing together, remembering together, hoping together.

So this Matariki, let's do more than just take the day off. Let's take the time to learn with humility, to listen with genuine intention, to connect with real purpose. Let's make space for conversations that actually matter, for questions that challenge us, for silences that heal. Let's honour the stars not just by looking at them but by living their values in our everyday lives.

We asked for the stars. Now comes the harder work: learning to live by their light.

Written By

Ishani Mathur (she/her) @vohnriladki CONTRIBUTING WRITER

By Tashi Donnelly (she/her)

@tashi_rd

FEATURE EDITOR

Column By Ricky Lai (he/him)

@rickylaitheokperson

CONTRIBUTING COLUMNIST

On certain days, you can feel how young Aotearoa is, pouting at its periphery to the rest of the world. It’s hard to tell what we – collectively speaking as a national consciousness – even really think of ourselves. Take Karangahape Road, for instance; The rainbow crossing spanning the width of one of Tāmaki Makaurau’s central business districts – that’s us. But the crossings overnight vandalization with white paint last March? Hurtful as it is to admit, that’s also us.

Don’t take this at all as an endorsement of reactionary ideologues, but as we recover pathways to the more radical, interesting world promised forty-or-more years ago, there’s a lot to learn from asking why our trajectory to progress is so often littered with pushback. There’s a more culturally rich Aotearoa somewhere along history – I hope we find it.

Ngati (Barry Barclay, 1987)

I’m a sucker for a period-piece atmosphere you can practically lean in and breathe the air of. Ngati’s multiple story threads are set in the fictional New Zealand town of Kapua in the year 1948. And yet, in post-colonial Aotearoa, it still brims with an optimism that I found profoundly moving – this is a rural nation in construction. Think of a rich novel unfolding with the limber, amateur-friendly rhythm of Cassavetes’ ‘Shadows’ (1958). It is cosy, amicable and buzzing with communal joy, to say nothing of the sweet, coastal air, and I’ll bet a large part of this can be credited to the natal talent of Barclay’s first-time cast and crew consisting mainly of Māori folk. Ngati concludes with a tangi service for Kapua to mourn the loss of one of their youth, but the cultural specificity brought on by Barclay’s team leads to a beautiful scene where each of the tāngata wash the tapu off their hands under a tap before leaving the cemetery. I have not seen that in a movie before.

Every projection of the abusive father in New Zealand lays, for better or worse (perhaps worse), under the shadow of Jake the Muss in ‘Once Were Warriors’ (1994) – a flagrant cartoon-sketch of a muscle-armed, bottle-breaking David Tua-wannabe with no restraint for whose lights to punch out. I’ve always felt that despite how well Lee Tamahori’s visceral approach shocks the senses, the subject matter could have, by now, used a more sensitive retread. In the crushingly slow and sensuous ‘One Thousand Ropes’, the patriarch of a Samoan father is introduced as a looming background presence during the birth of his daughter’s child; the two do not make eye contact. Between interludes that draw from Māori folklore – including the titular ‘thousand ropes’ of Maui suppressing the sun – we come to learn that he is attempting to make amends with his daughters by being there for his girls in natal and post-natal care, eluding the ghosts of his own spousal abuse that inhabit their walls. Their relationship is fraught, as we expect, but what leaves the audience a true impression is the camera’s close-up interest in seeing how he tries to rehabilitate his hands for good; rubbing coconut oil over a pregnant belly, the kneading of dough, the rolling of a lemon. You can just about catch the many scents here as the spectre of violence begins to simmer and re-surface.

Rain (Christine Jeffs, 2001)

Typically, I have no taste for brooding family melodrama – let alone that which uses death as a heavy-handed cue for the ‘Loss Of Innocence™’ – but ‘Rain’ would be so much less than that were it not for the disarming imagery here, forged out of the landscapes of rural country batches and shorelines that New Zealand holds dear. These are also characters you’ll relate with and remember. One of the very first images we see of Ed, the father of said family, catches his toes nearing a little too close to the whirling blades of a lawnmower – setting up the devastating trait of his indifference to oncoming danger. The whiskey-drunk, middle-aged house parties are steeped in elegiac quality; dimly lit faces, kissing silhouettes, and what must always be the stench of beer and whiskey. Parents in passionless marriages find their flings on the fringes, and a glass of liquor leads to young Janey’s gateway – or initiation – into adulthood. And nobody is acknowledging that they’re sad. This is the European, middle-class side of New Zealand that I recognise all too well.

My year in Rumaki Reo

Hurihia tō aroaro ki te rā tukuna, kia taka ki muri ki a koe

Turn your face towards the sun, let the shadows fall behind you

In ancient times, Rangi, the Sky Father, and Papa, the Earth Mother, held each other in a tight embrace. Their children dwelled in the darkness between their eclipsed bodies. They were discontent and ached for the light. Over time, their longing grew. It grew despite the weight of their parents, despite the pressing of the darkness enclosing like a black hole around them.

It was too late; once they knew of the light, they wanted nothing but to chase it.

This is what learning Te Reo was like: like coming in from the cold and dark. And sometimes it is—except you’re tripping over the doorstep, stubbing your toe on every corner, and you’re attempting to warm your hands around the day's fourth cup of coffee.

pō

1. (noun) darkness, night.

pōnānā

1. (verb) to be frustrated, flustered, anxious.

During my year in Rumaki Reo, I came to understand this balance and tension between the light and the dark in Te Ao Māori; about the prominence of the kupu “Pō” in words that often carry dark or negative connotations, and the overarching metaphor of this transition from Te Pō to Te Ao Mārama.

The night is long, but the light will come.

My first day of kura, I felt like I was going to vomit. I had been plagued for weeks by nightmares of social isolation, study link holds, and the irrational fear that someone from high school would be in my class. Despite reading the acceptance letter over 20 times, I was convinced that there had been a massive clerical error. I was sure that as soon as I dared to show my face in the classroom, everyone would see me for what I was: an impostor.

pōwhiri

1. (verb) to welcome, invite, beckon, wave.

2. (noun) invitation, rituals of encounter, welcome ceremony on a marae, welcome.

whiri

1. (noun) flock (of birds).

2. (verb) to twist, plait (a rope, etc.), weave, spin.

When I scanned the crowd at the pōwhiri, I could feel my stomach sink. I could feel my body wiri as the karanga pulled us forward. We were a flock of migratory birds; of manuhiri flittering, ushered in from the night — waiting to be cast under the protective cloak of the Wānanga.

nohopuku

1. (verb) to be silent, quiet, inactive.

noho

1. (verb) to sit, stay, remain, settle, dwell, live, inhabit, reside, occupy, located.

puku

1. (noun) (anatomy) stomach, seat of emotions

The first face I recognise pulls me into a warm embrace. He issued a wero for me: “I know you love your books bub, but you have to really listen.”

He manuka nui, kia nohopuku au.

rumaki

1. (verb) to immerse, drown.

Hold tight to that waka nē?

I had come to kura prepared to stifle my personality and maybe not be an insufferable know-it-all for once in my life. I told myself that I would not be loud in class like I usually was, or be the only tauira who put up their hand. I would try to listen and take as much in as possible. The first day in our new akomanga; PikiTūRangi (Hi!), I realised that I was surrounded by people with strong personalities who were unafraid to speak up. Where in some environments Māori people are considered “loud” and “disruptive” all while laughing like a kēhua, I was around people who, at the very least, matched my intensity.

I didn’t know that my brain had the capacity to hold that much new information. Each day we drilled kupu hou with mahi ā-ringa, stringing rākau whaikano into sentences, and sang waiata until we lost our voices. Then I’d go home, draw the curtains, and sit in the dark of my room. My mind was saturated, flooded with kupu. I had always been an academic overachiever, but for the first time, I felt truly stupid. Some of my classmates could stand and give whaikōrero after only a week, while I was still mixing up te and ngā, fumbling over pronouns. The kōrero washed over me. The more I learned, the more I realised I did not know.

Sitting in a circle, we went around the class and each took a turn to speak. Constantly writing and trying to find the right order for the words, the kōrero passes to me. I shake my head, set my jaw and say, “Next.”

pōuri

1. (verb) to be dark, sad, disheartened, mournful, sorry, remorseful. uri

1. (noun) offspring, descendant, relative, kin, progeny, blood connection, successor.

I would be lying if I didn’t admit my pōuritanga and my whakamā didn’t constantly follow me like a shadow.

Over a year before, I had been fussing over the enrollment, reading the expectations for the course: 80% attendance, 30-hour weeks - the expectation that by the end of the year I would stand and kōrero māori - and māori only—for one hour. There was an urgency I had to confront this thing. I had decided if I was going to do it, like most things in my life, I was all in. Baptism by fire.

And ultimately, it meant confronting the unrelenting question that had been following me for years:

How can you even call yourself Māori?

I had hang-ups to be sure, ones that were deep-seated and ached in the back of my mind. I felt like my life needed context, like people needed the full picture to understand, and therefore not judge the way I felt separated from my māoritanga. How could I call myself Māori when I had never been welcomed on my own marae, let alone stay there— I could barely string together a single sentence. I stammered through basic karakia. I had only a handful of kupu to begin to explain my upbringing in the church and the way they denounced Te Ao Māori, the internalised racism, and imposter syndrome. Why this, why now?

I desperately wanted people to know and validate the whakapapa of my pōuritanga, but at the same time, it felt too tapu to share. It still does.

mahanahana

1. (noun) warmth

I’ve always been partial to the back table. It provides a safety zone, one where you can opt in or opt out of class discussion and maybe even get away with whispering to your mates in Te Reo Pākehā. When you’re just learning to speak, your conversations dry up quickly.

“Kei te pēhea koe?”

“Kei te ngenge ahau.”

But that’s where I made my first friends. When no one was looking, Mitch and I would build towers from the rākau whaikano, do lunch runs to Blue Rose Cafe with Wiki and Te Amo, and have after-school drinks at Wapiti. It also meant going off on side quests where necessary, and that was usually on a Monday, during whānau hui where they didn’t take the roll.

At Takiura, parents are encouraged to bring their children, so we were blessed to have four babies in our class. Within a few weeks, I was stealing them away. They were a welcome distraction when I zoned out during lessons, and their cuddles were the highlight of my day.

For most people, learning Te Reo really is that deep. We had tauira ranging from 23 to 80, and we all carried our reasons with us.

It takes one generation to lose a language and three to restore it. For tangata māori, we can pinpoint these places in our whakapapa. We can recount at which point it was beaten by members of our whānau, when they went to school and had their mouths washed out with soap, and when their parents ultimately discouraged them from learning it for their own protection. When our parents didn’t have the kupu to teach it to us themselves.

Our future generations weigh in our minds, and we prepare the way for them. In our quest, we encounter ourselves.

“I think what you are doing is actually finding your other self, the one that’s missing.” Nanny Kaa Williams (on learning Te Reo Māori

rongoā

1. (verb) to treat, apply medicines.

My akomanga, and learning te reo became my rongoā. The more I learned at Rumaki, the more I fell in love. I fell in love with its layers, its depths. I fell in love with the art of the mihimihi, with the poetry we wrote for one another, with the way we showed up for one another.

Very quickly, we realised that there was no hiding. When you were expected to stand, you stood. When you were expected to speak, you spoke. When you were expected to do interpretive dances and silly whaakari, organise costumes, and write pao, stand in front of everyone at whānau hui, you did. Even if it meant stumbling, dare I say, face-planting through your reo, you needed to confront it. It was during times like these that our class became undone. Emotions running high, tension bubbling, and the shadow of whakamā hanging over all of us. I was not the only one who felt stupid, who felt like they were falling behind, who was whakamā, and pōuri and pōnānā. We were not alone.

1. (experience verb) to be clear, to understand.

When Tane Mahuta, the God of the trees, could want the light no longer, he lay on his back; stretching out the tree trunks of his legs. With all his might, he began to push the sky from the face of the earth. His parents' embrace tightened, resistant to the force. But Tane was stronger, and finally, as their skin separated, the mārama flooded in. Where the sky had been nothing but black, it became blue. And for the first time, he and his brothers could see clearly. For the first time, they understood.

In te reo, we draw this comparison; the idea of finally understanding something as a spark. The first light after aeons of darkness. Our realisation becomes a guiding light for us.

Mine came as a series of sparks.

The first spark: doing the Haka for the first time when our classmate Rachel spoke about her mamae. In response, we performed Ka Mate for her. That was the first time I had done a haka the way it was meant to be done — not choreographed, not rehearsed, but one that erupted from adrenaline, pride, and aroha.

I felt the spark of kupu, of finally grasping my foundations, understanding grammar and being able to speak from the top of my roro. In my fifth whakapuaki, I spoke for half an hour, kōrero māori anake, and the words flowed from me in a way they never had. I finally addressed my mamae and my whakamā for the first time.

I felt the flame light during the trip to Koroneihana, where everyone around me was speaking Māori. Our class sang for Kiingi Tuheitia. Where previously I had been too nervous, I maintained a ten-minute conversation in Te Reo.

During a class noho at Purekireki Marae, I did my first karanga. I had spent all day nervous for it, and in the moment, those nerves left me.

That night, for the first time, I slept beneath the whakairo of Porourangi; my tipuna. I woke up to see the paua shell eyes looking down at me.

In November, we had our graduation. A bittersweet feeling. A hundred haka were performed that day–waiata sang. Piki, my kaiako, gave me a personal mihi, and I stood to collect my diploma and hongi. I turned to walk off, truly not expecting a mihi on my behalf. But my father stood and began to sing Taku Manawa.

Taku Manawa, ko te Tairawhiti

He began to spin me around as everyone laughed. I could see and feel his pride at seeing his daughter chase something we had lost.

It was a healing moment for me, full of light.

I have a piece of paper now — a Diploma of Māori Language Fluency, Level 5 — and it’s precious to me. It’s not just a qualification; it’s a tohu of the countless hours I spent listening, crying, stumbling, laughing, and showing up anyway. It comes with the hours spent standing in front of my class while speaking a new language. It comes with Kapa Haka practices, late-night study sessions, and reminding my friends: “Kia kaha ki te kōrero Māori.”

My reo is still a work in progress — some days it feels rusty, and other days it flows like water from my ngutu. But it’s mine now.

I didn’t expect to be fluent in a year. What I did expect — and what I found — was a doorway. A journey of healing. A deepening. A long-awaited homecoming. A fire to feed.

Nothing came easily. Nothing was born from pure luck. It was fought for. It was carried through grief and joy, confusion and clarity, ngā piki me ngā heke, by me, my classmates, my kaiako, and everyone who came before us.

With my friends, my whānau, and my tīpuna behind me, I turn to face the light.

Written By Elise Sadlier (she/her)

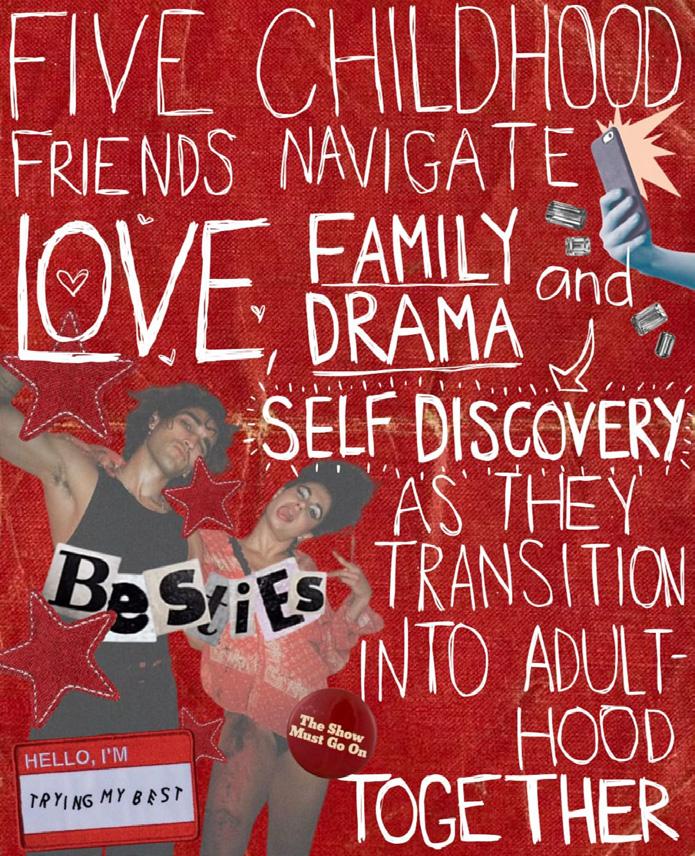

TAKAHOA, an upcoming five-part YouTube mini series following five childhood friends, is promising to be a compelling exploration of Māori identity in your 20s and the importance of community and friendship. Set locally in Tāmaki Makaurau, New Zealand, co-creators Monet Bailey-Ngatai and Jess Sewell share their journey from the roots of Overwhelmed Productions to finding a community of their own, seeking to represent several up-and-coming Aotearoa creatives through the show.

What inspired TAKAHOA, and how did Overwhelmed Productions come to be?

Jess: So, we originally were writing a show called ‘Overwhelmed’ and then it was a lot bigger scale. So, we ended with like pretty much deciding to do something a little bit smaller, and then we were like, “We need a production company.” Long story short, we called it Overwhelmed Productions based off of the original idea that we had, and then one day, Monet had an idea to do like a web series, or a mini series.

Monet: Well, we found a producer for our original idea, and she was the one who suggested we do something a bit smaller. And then we’re like, “Okay, let’s think about that.” And then, yeah, we came up with an idea, and then, yeah, just started. I was doing a business course to help, because we worked for my mum to help with her business, and Jess was like, “Why don’t you like, put this on if we had a production company?” and I was like, “Okay.” And then since then it’s just been like full speed ahead.

Jess: Yeah, it’s been a lot.

Why did you decide to specifically tap into the coming-ofage genre?

Monet: We love it.

Jess: Yeah, we love it and only just really recently lived it, so we’re kind of just writing about what we know. We’re both 25, so we’re pretty much like just writing on our experience of how we felt when we moved to Auckland, cause we’re both from very small towns. Monet’s from Waitara, and I’m from Napier, and we moved here pretty much around 19, 20-ish. It’s pretty much just based on that experience.

Monet: There’s a lot of like youth dramas in New Zealand, but they don’t really resonate with us. So because of that, we were kind of like, “Oh, let’s try to make something that would resonate with us, and we know what resonates with us cause we are-

Jess: We are in that age group, we are those people.

Could you guys briefly introduce your characters and the role they play within the story?

Monet: TAKAHOA is about five friends who have been together since childhood, and now they’re in their 20s. Attending Uni, out working or just, you know, figuring out what they want to do for the rest of their lives. Four of them live together in a shared flat, with their other best friend Alice, who lives separately from them in the city. They’re all navigating what it means to be an adult, like finding what their purpose is. Our first season is centred around Hana, who is Māori-Pākehā and a visual artist. She’s always been quite avoidant of her Māori heritage, and when she submits her piece to an art gallery and gets second place to someone who does more traditional Māori style of art. One of her best friends, Marley, who’s the only Pākehā girl in the group, calls the winner a ‘diversity win’ to make Hana feel better. But that’s obviously not how -

Jess: Not the right thing to say.

Monet: No, and Anahera overhears that, the girl who won, and confronts Hana about standing up for her culture, or for other Māori, and for letting her friends talk about that in her space. That experience makes Hana reflect on why she feels the way she does about being Māori and inspires this journey into her identity.

Jess: Yeah, and I feel like for you [Monet], you were writing from a personal experience.

Monet: Well, because I’m Māori-Pākehā, I was always very averse. I never felt like I was white enough to be a white girl, and never brown enough to be a brown girl. So, it was always like I don’t even wanna acknowledge being Māori, cause that’s what I have like control over, and no one can tell me anything. It took me a really long time to kind of feel comfortable talking about it, and with this project especially, I’ve really had to look into those feelings.

Jess: You had to confront it head-on in front of a whole bunch of other people.

Monet: Yeah, it’s been good for me, a good exercise.

So with that, what kind of messages are you hoping to send, especially to your Māori-Pākehā audiences?

Monet: There is no such thing as being not Māori enough, cause you’re just Māori and that’s it. You don’t have to do things or be a certain way to prove yourself as a Māori. Just embrace

Could you guys briefly introduce your characters and the role they play within the story?

Monet: TAKAHOA is about five friends who have been together since childhood, and now they’re in their 20s. Attending Uni, out working or just, you know, figuring out what they want to do for the rest of their lives. Four of them live together in a shared flat, with their other best friend Alice, who lives separately from them in the city. They’re all navigating what it means to be an adult, like finding what their purpose is. Our first season is centred around Hana, who is Māori-Pākehā and a visual artist. She’s always been quite avoidant of her Māori heritage, and when she submits her piece to an art gallery and gets second place to someone who does more traditional Māori style of art. One of her best friends, Marley, who’s the only Pākehā girl in the group, calls the winner a ‘diversity win’ to make Hana feel better. But that’s obviously not how -

Jess: Not the right thing to say.

Monet: No, and Anahera overhears that, the girl who won, and confronts Hana about standing up for her culture, or for other Māori, and for letting her friends talk about that in her space. That experience makes Hana reflect on why she feels the way she does about being Māori and inspires this journey into her identity.

Jess: Yeah, and I feel like for you [Monet], you were writing from a personal experience.

Monet: Well, because I’m Māori-Pākehā, I was always very averse. I never felt like I was white enough to be a white girl, and never brown enough to be a brown girl. So, it was always like I don’t even wanna acknowledge being Māori, cause that’s what I have like control over, and no one can tell me anything. It took me a really long time to kind of feel comfortable talking about it, and with this project especially, I’ve really had to look into those feelings.

Jess: You had to confront it head-on in front of a whole bunch of other people.

Monet: Yeah, it’s been good for me, a good exercise.

So with that, what kind of messages are you hoping to send, especially to your Māori-Pākehā audiences?

Did you ever imagine that it would take off like that?

Monet: No.

Jess: I did not expect the stretch goal to even be a thing.

Monet: Well, we were like surprised right from the beginning, we’ve been constantly surprised about how well-received our project has been. Like, when we first put an ad out on Instagram for a cast and crew, we didn’t expect anything. And then the next thing we know, we have 20 people in our house doing auditions. And we were like, “This is crazy!”, and it just keeps getting crazier.

Jess: Yeah, now we have about 25 cast and crew, which is insane.

So, what are the next steps for you guys?

Monet: Shoot the shot.

Jess: Yep. We need to nail down pre-production. We’re really getting into the busy stage. We’re finalising the budget and all that sort of stuff.

Monet: There is no such thing as being not Māori enough, cause you’re just Māori and that’s it. You don’t have to do things or be a certain way to prove yourself as a Māori. Just embrace who you are, that’s what it’s all about.

What was it like surpassing your monetary goals and receiving such overwhelming support for TAKAHOA online?

Jess: It was awesome and unexpected, cause I think because with Boosted in the first week it kind of goes full steam ahead and they’re donating, and then in the middle two weeks, in week two to three, is when it sort of dies down. So, we have to push out more story-related stuff for the audience to keep them engaged and keep wanting to support the project. And then in the last week, it picked up again. So, I think in week three is when my hopes kind of got down a bit, and I was like, “I don’t think we’re gonna be able to do it.” And then in week four, we got accepted to the Rule Foundation. They gave us a grant that went in, and then we got to match donors, and then that kind of just picked up the speed again, and yeah, it started to feel more real.

Monet: We had people donating in the last 10 minutes. Like I swear, they were only doing it cause they wanted us to have an uneven number. And then Jess was like, she put the last-

Jess: I was the very last donation, because I was like, “It needs to be an even number.”

Monet: We were like, “After the crowdfund, we’ll have a little moment to breathe.” Never.

Jess: There is no moment.

Monet: Yeah, so we’re shooting at the end of this month, and then we plan to distribute on YouTube at the end of August, and we’re going to do it weekly. So keep an eye out for us on YouTube over at @overwhelmedproductions.

Anything else to add on TAKAHOA?

Monet: I think it’s worth talking about how our kaupapa for this project is to uplift and showcase emerging creatives in the industry.

Jess: Especially in New Zealand.

Monet: Yeah, especially Aotearoa creatives, because we are 25, and all of our crew and cast are around our age.

Jess: Around 20-ish.

Monet: Yeah, and still in that age bracket, and they’re all quite like you knowwe’re based on vibes, we judge based on that. We don’t even know what they do for their actual job, in the interview, we’re just like, “What’s your favourite movie?” And then we have like callouts on our Instagram for Aotearoa-based musicians, visual artists, fashion designers, and we’re just trying to like build a community. We can see how we can help them out, how they can help us out, how we can all just support each other, showcase each other, and, ultimately, be there for each other.

Through TAKAHOA, Monet and Jess strive for authentic and diverse cultural, youth and queer representation that depicts real stories based on real-life experiences. Keep up to date with their progress on their Instagram and YouTube @overwhelmedproductions for more information on the release of the show.

Katha O Maatram is a piece that breaks the conventional, challenging many implicit stereotypes in South Asian society. Additionally, it serves as a mirror to the artist - to Sahana Rahman’s soul. It has been an honour both as a good friend of Sahana’s and a writer to critically analyse the autobiographical fragments of this piece. It shows her way to the stars, which resembles the community, strength and peace she found at the current stage in her life.

The project took shape over five months of inner reflection and deeply rooted introspection on societal issues that personally impacted the artist’s life. There is meticulous attention to detail in terms of the paintwork and artistry, inspired by the Mughal miniature style of painting and surrealism. The repetitive nature of elements, occult musings and more are depicted through matte acrylics. Rahman successfully executes a series of art frames that read chronologically and depict the struggles and highlights of her life.

What strikes me is how the artist weaves a tapestry of rich heritage, while presenting a realistic analysis of the detrimental impacts of colonisation, false characterisation contributing to identity crisis and how our loved ones influence how we perceive ourselves. As a fellow half-Tamilian and half-Bengali, being able to witness the intricacies of our culture through intricate and detailed paintings truly resonated with me. How fitting that historically, Bengalis were recognised predominantly for their tenacity during the era of freedom fighters, for dance, for writing and art. To me, Katha O Maatram centres around the idea “one must always return to oneself, no matter the curves life throws at them.”

Much like the moon, the artwork proceeds through phases of enlightenment and transition. The following sections take a deep dive into these phases and their respective representations.

Review of the exhibit:

Katha O Maatram (Stories Of Becoming)

Sahana Rahman @shannyszn

The artwork begins with a portrayal of Rahman’s higher self. There is a duality herein; this is not just who the artist is aspiring to become, but rather a being that has already existed within her. The significance of her being ‘ready to bloom’ is heightened by her seat - a lotus flower. Occupying an auspicious symbol of Indian culture and mythology, the lotus also serves as the national flower of India. It is a symbol of enlightenment, rebirth and spiritual awakening. The flower emerges from mud to bloom in the water, which foreshadows the artist’s rise from adversity. Rahman faces forward towards the upcoming scenes, a sign she is (expectant) of the (inevitable) life experiences to come. The setting is Newlands, Wellington, where Sahana was brought up with Mount Kaukau and harakeke to complete this canvas. The harakeke holds a particularly special place in the artist’s heart as it centres around a waiata sung at her primary school - He tangata, He tangata, He tangata.”

As the artwork progresses, the viewers are then able to see the artist’s heart growing and violets present. Violets here resemble queer pride, appearing multiple times in the poetry of Sappho and other writers. The uterus here resembles an anchor weighing the artist down, alluding to her struggles with PCOS. Through the thorough detail implicit in the natural backgrounds, there is a hidden figure of a woman in the rocks lying down and spreading her legs as the artist’s ex-lover is in the water looking up. Allusions to the calm before the storm exist in the colourful elements of

the artist’s childhood. The figure of an angel in the sky is Rowena, the artist’s god grandmother - a prominent life figure who had an abundant garden and wished for the artist to “grow as tall as a sunflower.” The waterfall reaching heaven sits as a parallel to the Stairway to Heaven analogy, with the following phases showcasing how this sanctity can be disturbed in a minute’s glance.

PHASE THREE

Light to dark sits as a metaphor here, with the colours of the paints visibly transitioning. The highway signifies that life began to move extremely fast - the sprawling urbanscape of Wellington and people under the bridge acting as the epitome of being alone, of being homeless. Where to find home, other than in oneself? The idea of death and darker meanings are hinted at, and the number 18 on the tunnel, which is when things took a haunting turn for the artist as she had to face homelessness and her traumatic past with men.

PHASE FOUR

Chaotic and indescribable, this scene, through its wit, serves as a depiction of colonisation. Through the British, Dutch, Portuguese, Persian and Mughals, through the various animals, through the splattered blood - this is the mayhem many countries faced. There is an irony present in the artist’s attire at the end, as she is in Western clothes, contrary to the depiction of her higher self on the lotus at the start in a sari. Perhaps more than a direct representation of colonisation, it also showcases the complex immigrant journey of finding home away from home, and the sacrifices we must make to achieve this. The footprints turn from a solid brown black to red, almost as if the artist has bled out to get to where she finally needed to be. The light at the end of the “tunnel.” The bear directly behind serves as an anecdote to the “man or bear” analogy, as if the bear were the one to pick up the pieces of a past man left scattered.

PHASE FIVE

The sun shines in this scene and has the patterning of the solar plexus chakra - in Hinduism, this is associated with personal power, self-esteem, confidence and willpower. It is a representation of vitality and the energies needed to manifest your goals, moving forward with both courage and determination. This same sun guided the artist to art school. If you look closely, this same chakra is mimicked on the Nokshi Katha table in the final phase of the artwork. To me, this symbolises the artist’s chosen family being present in the abundance of that vibrant and meaningful energy.

The use of the colour red is a tap towards the deeply rooted anger and frustration the artist felt through their traumas. This was discovered through EMDR therapy, where the artist described her aches as a red beating light. I think this showcases the ever-present nature of anger - oftentimes it sits like a beating drum in our chests, hands held with the emotions of confusion, frustration and betrayal. But what we fail to realise is that anger has immense power to change people.

PHASE SIX

The final scene has an umbilical cord showcasing complexities in the relationship of mother and daughter, but the cord dives into a deep blue. Nature and Mother Earth always served as grounding factors for the artist. We reach the end, where the artist is hosting a Nokshi Katha workshop - an ode to Auckland being her newfound home for creative awakening. The animals are of Klous, with the turtle being the artist’s partner’s spirit animal. There is also the beautiful signifying of a complete ending as Rahman’s armour, though still on, still wishes to gift a flower to Kripalee, her partner. Throughout the creation of this piece,

a blackbird consistently peeked through the artist’s windowperhaps a spiritual guardian, keeping Rahman steady as her heart was poured into paints. It shows queer joy with portrayals of non-binary and the artist’s Bangladeshi trans friend Shomudro, depicted playing the sitar, a classical instrument. The horse resembles equine therapy, and the snail was off an intuition. It hints at an intentional nature in the slowed pace of the art from a hectic, chaotic and boisterous scene before this.

Navigating the Academic Journey Together Under the Stars of Matariki Kia ora tātou!

I’m Vyshakh Rajendran, your Vice President (Academic) at AUTSA - your voice at AUT. I try to uphold our motto by amplifying your voice in AUT boardrooms that make your learning fruitful and rich. I represent your academic interests, and raise concerns with university leadership to make tangible changes to your university experience.

I’m sure everyone’s a bit more relaxed after the first semester, and taking time for self-reflection (not that practice what I preach, just thinking out loud), something that we are reminded of during Matariki – the Māori new year. I was genuinely elated to write an article for Debate’s Matariki issue. And guess what? Matariki took place on my birthday this year! So feel free to shower me with belated birthday wishes and your valuable feedback at vpacademic@autsa.org.nz.

Matariki can be spotted by following a straight line through Te Kokota from Orion’s belt towards the west, much like what I have done, following my own stars in pursuit of a new journey. It makes me proud to have started my role a the first international student to hold this position (a huge shout out to all those who voted for me!) If you are someone who aspires to represent and stand by fellow students at AUT, now is the time to make it happen as we, AUTSA, are entering our election phase to elect our new SRC for 2026. More info can be found at https://www.autsa.org.nz/elections.

Now, let’s jump into the business side of things! I have been involved with many meaningful initiatives to make your university experience better than yesterday. We have been doing this by actively gathering your feedback in person around the campus, so next time you see myself or other SRC members, don’t be shy! Come say hi and have a chat (as long as neither of us are running late for class). Recently, I have worked with the AUT academic quality office to gather feedback from deaf Ākonga on AUT students feedback policy. Through your feedback, we have also been working on some of the most pressing issues for our cohort, such as cost of transport, accommodation, quality of lecture and course material, and much more!

I am keen to hear about any difficulties in your studies, or if you have suggestions for improvement. Please reach out to me or any SRC member. We can all benefit from a better educational experience thanks to your voice. Mānawatia a Matariki – may this season bring you clarity, growth, and inspiration.

Ngā mihi,

Vyshakh Rajendran

Vice President Academic, AUTSA

Q: 18, she/her

Hi Tashi, I hope you can help me with this. I’m having a weird time with my best friend and I’m not sure if I’m overreacting or if something is actually off. We’ve been close since year 11, and we’re both at different Auckland universities now, but lately I feel like everything has become this subtle competition. She always asks what grades I got (which feels weird because we’re in different courses and different schools!), and when I tell her, she either one-ups me or downplays her own results in this fake-humble way. It feels like she only asks so she can talk about her own grades. She’s also started copying things I do, like dyeing her hair the same colour I just did, and posting similar captions on insta. I feel like I’m getting too annoyed by it, and I don’t want to be.

It’s not only that stuff, it’s other subtle stuff too. Sometimes when we’re trying on outfits for a party she’ll say things like “Aw, your boobs look so much better than mine in that dress, not fair!” And we laugh, but it felt like a weird backhanded compliment. She also constantly points out who is flirting with her, and who’s checking her out, but when I mention that I thought someone was flirting with me she always says “Nah, I don’t think that was flirting” and makes fun of me (not in a super mean way) for not being able to tell.

I feel like she’s making me feed into this women competing with other women trope that I don’t want to be a part of. I wonder if I’m just being insecure, but part of me feels like she wants me to feel that way. I don’t want to lose her, and she wasn’t like this in high school, but I’m tired of second-guessing everything she says and does. How do I talk to her about this without it turning into a massive drama? I don’t want it to come across like I’m jealous and bitchy. Any help with this is appreciated!

A: Dear Anonymous,

For starters, I don’t think you’re overreacting. In fact, I applaud your radically compassionate question. These days, I think a lot of people would tell you to set up boundaries or to cut the “negative energy” from your life. I’m not going to do that. Firstly, because

you’ve explicitly expressed a desire to remain friends, and secondly, because I don’t think cutting people off as soon as they do something annoying serves our humanity. However, I’ll try not to bore you with my personal philosophical beliefs.

The way your friend is acting is making you second-guess yourself because it’s bordering on gaslighting. I don’t mean the kind of intense, abusive gaslighting that’s become a buzzword in online discourse, but the subtle kind that speaks more to immaturity than willful intent to harm. You’re a good friend, so you want to make sense of it. Let’s try to do that.

When I read your letter, I was overwhelmed by the same kind of protective sympathy I have for all teenagers. You’ve entered a new, adult part of your life. The step from high school to university is a big one. It’s scary and exciting.

For your friend, going from the closeness of a high school friendship to the comparative distance of a university-aged friendship might be a shock. She may have been more reliant on you emotionally than she realised. And even though you’re only separated by Wellesley Street East, she might feel terribly abandoned.

Her actions might seem like a strange response to missing you, but it could come from a fear of abandonment. If someone’s used to feeling emotionally dismissed and ignored, especially as a child, then when someone is actually there for them, and reliable, it can feel weirdly frightening. It’s like their brain is going, “Wait, no one else has been this consistent, I can’t trust that this is real.” And instead of recognising that as a fear, they act out in subtle, self-protective ways.

One of the ways people deal with these uncomfortable feelings is by projecting them. It’s kind of like an emotional game of hot-potato. They pass off the discomfort to someone else. Basically, instead of thinking “Oop, I’m feeling a bit jealous,” your friend feels the need to make you feel jealous instead. That way, she doesn’t have to deal with those feelings herself. It’s likely not on purpose; it’s just a messy way of trying to cope and stay close, at the expense of your friendship, unfortunately.

So yeah, she’s a bit envious of you. It’s not a crime, as far as I know, but it’s certainly a little more than uncomfortable for you. The tricky thing with envy is that it can either bring people closer, like, “I admire you, and I’m lucky to have you in my life”, or it can turn into unhealthy comparison. Right now, it sounds like your friend has her navigation system calibrated toward sabotage.

This might explain why she brings up grades (even when it’s not relevant), copies your hair and Insta captions, makes comments about your body, and dismisses your experiences when you feel seen or desired. She’s trying to put you in the role of the “insecure one” so that she doesn’t have to feel that way herself. And the teasy, jokey tone lets her dodge responsibility, and makes you question whether you’re being too sensitive.

But hey, here’s the thing: so many of us go through friendships like this, especially around your age. It’s common to test boundaries, act out a bit, fall into subtle competition without realising it and potentially ruin friendships while trying to figure out who you are. I’m guilty of doing this myself when I was a teenager, back in the Middle Ages.

The fact that you’re noticing this and asking about it means you’re already ahead of the game. And with a little honesty and self-aware-

ness, from both of you, this friendship still has a shot at becoming something healthy and strong.

How are you going to address this with your friend? It’s a tricky one. If your attempt doesn’t result in tangible change, I would probably suggest a bit of distance. But you’re young, some of this stuff is just emotional growing pains.

It’s important to recognise that you’re picking up on your friend’s emotional discomfort, not your own inadequacy. That in and of itself is a solid emotional boundary. You’re doing a great job of holding the complexity already: you haven’t labelled her as “toxic” or “fake”, just someone who’s behaving strangely, but is still your best friend.

If you respond to the projection with more projection, it’ll only feed the cycle. As Jessica Benjamin puts it, “We are not simply passive recipients of projections. We participate in a process of mutual recognition or misrecognition.” If you indulge the projections, it gives them more weight, but it doesn’t make them real. The antidote is made with vulnerability. You need to tell your friend genuinely how her actions have made you feel.

So, how do you bring this up without it turning into a petty fight or spiral of defensiveness?

Start with “I” statements. Rather than “You made me feel…,” try something like: “I felt uncomfortable when you said ___, and I want to understand what you meant so I don’t overthink it.” She can’t argue with how you feel. That’s not up for debate.

I’d also avoid framing the conversation as a You vs. Me. Instead, it should be both of you vs. the problem. Esther Parel talks about this as a key to conflict resolution, not defending positions, but trying to understand each other’s inner worlds.

Most importantly, stay curious. You’re already doing this part. Curiosity opens up conversation. It doesn’t judge prematurely. Instead of saying, “You hurt me in these ways,” try: “Can you help me understand what was happening for you when…” It keeps things open instead of accusatory.

I know this probably sounds like a bit of effort on your part, but none of this should feel like walking on eggshells. If she is receptive to your honest attempt to connect, wonderful! Your friendship can blossom. If she has a meltdown and refuses to engage, remember: you’ve done your part. There’s not much left to try. Respectfully, she can go compete with someone else’s nervous system.

Answered By Tashi Donnelly (she/her) @tashi_rd

FEATURE EDITOR