Copyright Infringement and Image Ownership in the Age of Social Media:

Copyright Infringement and Image Ownership in the Age of Social Media:

To contribute a deeper understanding of content shareability in the digital age, this research project explores the layers of copyright infringement and image ownership on Pinterest, a popular social media platform focused on visual curation and inspiration. With an extensive study on the interplay of the platform’s copyright regulations, user importance, image usage, and modern social media standards, an indepth content analysis via autoethnographic and ethnographic methods was completed to gain insight into the frequency of copyright infringement occurrences on the platform. By seeking to uncover Pinterest’s structural factors that contribute to the loss of image ownership, it was concluded that Pinterest users unknowingly engage in copyright infringement due to the platform’s ambiguous policy descriptions and promotion of visual curation, yielding a misalignment between copyright law and social media shareability and a recurring loss of image ownership.

The emergence of social media platforms throughout the 21st century significantly altered how society consumes and shares visual media. Unlike dominant - and often controversial - platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly known as Twitter), the creativebased image-sharing platform Pinterest remains neutral from public scrutiny and continues to harbor rapid growth in popularity, engagement, and content.

Now boasting over 498 million active monthly users worldwide, Pinterest was formally launched in 2010 by founders Ben Silberman, Paul Sciarra, and Evan Sharp as a website intended for virtual curation and inspiration. Pinterest allows users to “pin” images and videos from the internet, save and categorize them into personalized “boards,” and explore existing pinned content from other users.

The process of pinning images can be accomplished by methods such as 1) directly uploading an image and 2) link embedding, which “is a process through which one can visually integrate content that is stored in a different place on the Internet” (Palmieri and Reed, 2023, pg. 3). The content featured on Pinterest originates from sources outside the platform, putting “users’ passion for collecting visual content in the foreground” (Kasakowskij et al., 2021, pg. 2) by sourcing images from thirdparty websites. Further, the

platform offers common social media affordances such as following other users, sharing and messaging, and commenting. Pinterest’s homepage also presents a personalized feed of visual content based on users' activity and followed accounts. Pinning an image uploaded by a different user is referred to as “repinning” and is the most common form of curation for current users; examples of this action include pinning images featured on your home feed or from another user’s profile. Unlike other social media platforms, Pinterest relies on user-found content instead of user-created content. In many cases, “any image details and sources are not included in the pin’s description” (Kasakowskij et al., 2021, pg. 2), and the original owner cannot be identified unless the pin was uploaded via embedding. The anonymous, uncredited nature of a pin - specifically a photo, video, or form of visual art - poses the risk of copyright infringement. The threat of copyright is raised if the pin does not contain a description of the source and therefore bears an “infringement of copyright to copy or communicate a work to the public without permission of the rights holder” (Bosher and Yeşiloğla 2018, pg. 14). On Pinterest, image ownership easily and often goes uncredited, presenting the platform with a recurring phenomenon promoted through the logistics of copyright regulations and modern social media norms of shareability. This research project seeks to understand the aspects of Pinterest’s platform structure that quietly enable frequent image and copyright infringements and the loss of creative ownership online.

E S T I O N S

1.

2.

What aspects of Pinterest’s platform structure enable frequent copyright and image ownership infringements?

How is creative ownership of visual art lost through the dependence on user-found content on Pinterest?

S T A T E M E N T

Pinterest users unknowingly engage in copyright infringement due to the platform’s ambiguous policy descriptions and promotion of visual curation, yielding a misalignment between copyright law and social media shareability and a recurring loss of image ownership.

“occurs

when someone reproduces, distributes, or displays a copyrighted work without the express permission of the author or copyright holder” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 6)

The desire to share is the driving force behind social media, and much of the content users regularly consume contains visuals in some form. The inclusion of images and videos on platforms strengthens how users communicate ideas and experiences, and Pinterest is a primary example of this expression. Though the issue has become a point of discussion with the rise of social media development, copyright infringement has long been a topic throughout media history.

Copyright infringement “occurs when someone reproduces, distributes, or displays a copyrighted work without the express permission of the author or copyright holder” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 6).

Published only two years after Pinterest’s public launch, Carpenter provided an early analysis of Pinterest’s copyright liability and general understanding of copyright law. It is crucial to understand the doctrine of Fair Use in the United States, which “confers a privilege on people other than the copyright owner to use the copyrighted material in a reasonable manner without his [or her] consent” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 6).

Fair Use, which was determined by Carpenter as Pinterest’s long-term protection from infringement, is analyzed in a court of law through four factors: “1) the purpose and character of the use; 2) the nature of the copyrighted work; 3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and 4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 7). In many cases, the fact that an

image was publicly published online before being pinned weakens any argument from a copyright owner on the topic of Fair Use. In addition, “the first statutory factor in the fair use analysis easily favors a determination that Pinterest users’ copying of online images is fair use” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 15). The purpose of why an image was pinned by a user is defined through the namesake of the platform - pinning an interest.

Less than 20% of Pinterest users read the Terms and Conditions.

The content displayed on Pinterest is the direct result of user curation and selection. That said, most Pinterest (and general social media) users do not know their curating could be creating a legal issue, likely ignorant “of the fact that such images published online are subject to copyright and licensing laws” (Carpenter 2012, pg. 14) and thus “do not worry about copyright infringements” (Kasakowskij et al., 2021, pg. 2). Kasakowskij et al. (2021) completed a multi-layered information service evaluation on Pinterest’s data collection process, along with an anonymous survey investigation on user’s trust from 365 responders (276 female, 90 male, and eight assigned to a different gender). It should be noted that Pinterest’s users are over 75% women, and the platform has been referred to as an example of a “highly feminized site of digital cultural production” in a Duffy (2015) discourse study of authenticity, community building, and brand devotion. The 2021 survey concluded that although less than 20% of users read any form of Pinterest’s Terms and Agreement, which includes copyright guidelines, they were not concerned about Pinterest’s legal issues and had a positive level of trust for the platform. What many users overlook is that “Pinterest itself has no direct copyright issues” (Kasakowskij et al., 2021, pg. 7) because the platform assumes “no responsibility for links, Web sites, or third-party services” (Kasakowskij et al., 2021, pg. 5) that are uploaded by users. This form of user ignorance - which most individuals can relate to - allows safely allows the content on Pinterest to remain.

This safety can be credited to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act passed by Congress in 1998 as an expansion of the 1976 Copyright Act. The DMCA is “aimed at placing the blame on the person who is actually responsible for copyright infringement” (Fink 2014, pg. 19) and not the Internet Service Provider (ISP) supplying the platform where it occurs.

In the scenario of Pinterest and copyright infringement, Fink (2014) informs how the platform’s policies are “aimed at protecting itself” (Flink 2014, pg. 11) in a court scenario by subtly informing its users on how to protect themselves through the listing of their copyright policies - which Kasakowskij (2021) determined most users do not read. In short, the pin creator is at risk of being the scapegoat for a case of copyright infringement on the platform rather than Pinterest as a company.

Pinterest users have been encouraged to pin their images via embedding since the platform began in 2010. However, a direct emphasis on how this approach is crucial to limiting the possibility of copyright infringement is lacking in visibility. Embedding enables safe shareability through source inclusion. Palmieri and Reid (2023) studied the platform user agreements from YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), Pinterest, and TikTok. They found Pinterest to clearly allow intraplatform sharing, defined as when users actively “‘reshare content that other users have already placed on the platform, thereby redisplaying that content to other users” (Palmieri and Reid 2023, pg. 5). Nonetheless, Pinterest had the most ambiguous policy on interplatform, which is the “off-platform sharing as activities that display or perform content residing on a social media platform outside the platform, or thirdparty sites'' (Palmieri and Reid 2023, pg. 5) - otherwise interpreted as the locations users find pins. Pinterest’s stance on interplatform sharing is neither “expressly prohibited” (Palmieri and Reid 2023, pg. 32) nor undoubtedly allowed. To limit this confusion, Palmieri and Reid (2023) offer the addition of “unambiguous language” (Palmieri and Reid, 2023, pg. 39) to limit the possibility of legal disputes over content sharing.

More on the matter, Eckhause (2022) noted how the frequency with which internet users encounter images facilitates the mindset of openended usage. Particularly on Pinterest and Instagram, the originality of a photo shared will sometimes be neglected for the sake of aesthetic curation. Carpenter (2012) explained how Fair Use continuously works in Pinterest’s favor, but there is an extent to which an image can be changed or shared. Digitally editing an image in a way “that results in the creation of a fixed, original work - or that uses, shares, borrows from, or modifies an original work is subject to the rights and limitations of

copyright law” (Palmieri and Reid, 2023, pg. 5). Eckhause (2022) analyzed complaints of 1,157 photography-based lawsuits and found that many accusers were “acting in opportunistic ways to take advantage of the Copyright Act’s unusually generous statutory damages” (Eckhause 2022, pg. 98).

When contextualizing this study toward Pinterest, the poor direction of copyright regulations explained by Palmieri and Reid (2023) puts users in a legitimate position of vulnerability and financial risk if they choose to edit an image and pin it as their own. Pinterest has been previously coined as a site that does not “fully embrace the policing role they must play” (Gillespie, 2018, pg. 59) in maintaining users’ safety. The Pinterest user, once again, becomes vulnerable due to the platform’s lack of legal protection and support.

In a case study of Instagram completed by Bosher and Yeşiloğla (2018), the technological function of screenshotting was presented as a leading way users copy images from social media platforms. The observation determined that many images on Pinterest are screenshots from a source and then uploaded as an independent pin - this action, because it excluded creator credit, risks copyright infringement. As technology continues to evolve, the social norms of usage shift simultaneously. Social media is a clear example of this shift and has continuously illustrated rapid displays of online trends. The recurring misalignment between copyright law and social media practices was explored by Meese and Hagedorn (2019) through a grounded theory approach, emergent thematic analysis, and group interviews. Most regular social media users, including those on Pinterest, do not know or care about copyright infringement as much as those within creative communities whose work is notoriously stolen or reworked by different

users. Through four semistructured group interviews containing two to six people who identified as regular social media users in Sydney, Australia (11 female, five male) elapsing 40-60 minutes, Meese and Hagedorn (2019) concluded there are “are no centralized community discussions around ownership and attribution, which regularly occur on online creative communities” (Hagedorn and

Meese, 2019, pg. 7), evident through the absence of specific guidance to copyright laws on platforms like Pinterest.

Social media has presented a challenge to copyright law because its collaborative nature defies “traditional notions of ownership and because digital images frequently do not conform to copyright’s view of the image as a singularly “fixed” construct ensconced in a tangible medium” (Ekstrand and Silver 2014, p. 2). In the age of smartphone photography, the visual image on digital platforms like Pinterest has become more complex. Ekstrand and Silver (2014) studied the history of the visual image and how it translates to the current forms of images on social media, relating to how Bosher and Yeşiloğla (2018) found that the disparity between the principles of copyright and social media to lead to confusion and vulnerability of users. Notably analyzed by Ekstrand and Silver (2014) was the Selfie, which is an image format popular amongst Pinterest feeds; the authors suggested that “the selfie’s actions might suggest that the copyright, though owned by the creator and subject of the photo, is more like an implied license, in which the creator’s actions suggest that the copyrighted content is intended for sharing and reuse” (Ekstrand and Silver 2014, p. 8). An image shared on the Internet retains its copyright “when uploaded to a social media or photo-sharing site” (Ekstrand and Silver 2014, p. 4) like Pinterest.

I employed autoethnographic and ethnographic methods to answer this study’s research question and further scholarly discourse on Pinterest. Pinterest allows users to reverse image search photographs to find pins that are identical matches or options that showcase similar content. As a creative individual with active, public social media accounts, I examined my personal experience and understanding of Pinterest copyright infringement by selecting 25 of my photographs to search. Further, I searched 25 of my friend’s photographs (Quincy Whipple, @whipplequincy) because of her unique position as an influencer with over 132,000 TikTok followers and 34,000 Instagram followers. Each of the 50 total images was selected due to previously demonstrated high engagement (1000+ likes or reposts) on other social media platforms including Instagram, VSCO, and TikTok. My Pinterest search data was coded through Content Analysis and categorized into 1) image frequency, 2) the method of pinning, and 3) the inclusion of image owner credit. Additionally, I interviewed Quincy to gain insight into her perspective on the matter through the lens of an internet figure as an ethnographic method. By completing this study, my goal was to gain a first-hand account of copyright infringement on Pinterest and interpret if my findings could constitute legitimate legal action.

F I N D I N G S

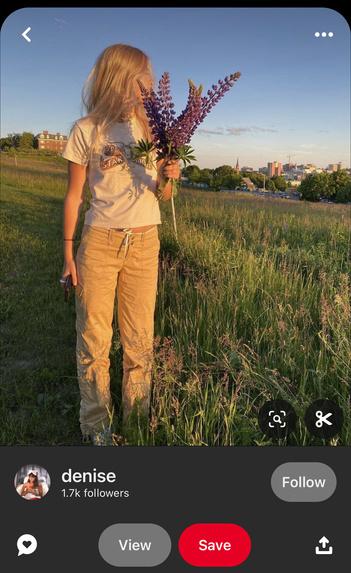

I took this photograph on August 20, 2020, and posted it to VSCO on August 21, 2020. VSCO is a popular image-editing and photo-sharing social media app. Unlike other photo-sharing apps, VSCO does not allow users to see their own or other users’ follower and repost counts. “Reposts” are the VSCO equivalent to likes, where users can repost other users' work to their feeds.

Three months after my initial post of this photograph, it began to go viral on the app, steadily averaging 100+ reposts a day for over a year, and was featured as a trending post by VSCO. I still receive reposts almost four years later.

After searching my photograph into Pinterest, 35 matches showed up. This number is tentative, as I learned throughout my research that Pinterest’s image search does not provide all matches, so I can confidently assume many more matches are circulating on the platform that I did not find.

Of the 35 I analyzed, not one credited me as the image owner in any way. Only three showed my image in its original appearance - the other 32 had digitally edited it in some way (coloring, cropping, exposure, sharpness, etc). Two examples were pinned as embedded links from other third-party sites - Spotify and Wattpad - which have no connection to me or the original VSCO post location. The three examples that were unedited yet uncredited, would not pass a verdict of copyright infringement because of their pin intent and my openness to share my work publicly, in reference to the Doctrine of Fair Use. However, the examples that were outwardly edited, altered, and uncredited, would constitute cases of copyright infringement.

Throughout my image search, I was led to a user profile of a teenage girl whose created pins featured 30 of my photographs. These pins were screenshots of photos I posted on VSCO, some of which were posted two years ago, and had slight filters and recoloring added. I was not credited on any pin as the photographer and there was no reference to the photos being found on VSCO. It is important to note that this user follows me on Pinterest. The usage and altercations made of my photographs would constitute copyright infringement. However, this case would not be considered due to the direct affiliation of the user as one who interacts with my profiles and is aware of my ownership. Pinterest encourages visual curation, and because the girl is someone who follows me and appreciates my photographs, her creation of these pins is not done in a malicious or harmful way and does not decrease the value of my work.

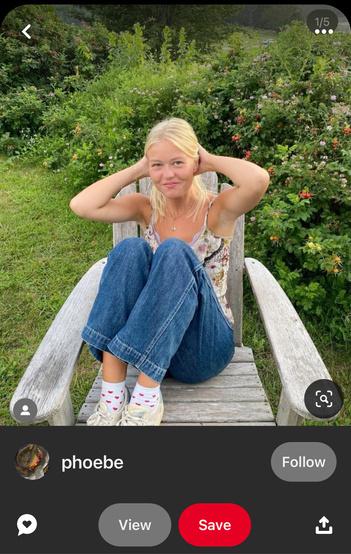

Quincy Whipple (@whipplequincy) is a social media influencer with 132,000 followers on TikTok and 33,000 on Instagram. Her content primarily focuses on lifestyle, fashion, beauty, and college life. Quincy’s TikToks garnish tens of thousands of views per video and her Instagram posts regularly receive 10,000 likes. Due to her vast exposure on social media, photos and videos she has posted on her profiles often appear on Pinterest - I explored this further with my image-searching research.

Since Pinterest is a popular location for fashion inspiration, photographs from Quincy’s Instagram and screenshots from her TikTok frequently get pinned because of her fashion-related content. My searches discovered that pins of Quincy are very popular on Pinterest. Her status as an influencer places this case study in an interesting conversation of image ownership as a public figure, particularly when sharing visual content is your job. Quincy posts on social media with the knowledge that a large audience will see what she shares - that is the goal. In turn, her public image - quite literally, her appearance - has become recognizable amongst many social media users, particularly Gen Z.

There was a surplus of pins featuring Quincy - mainly photographs of herself that she has posted, but also photographs she has taken. Some pins credited her as an individual in the photo - either through embedding her original post, adding her name to the caption, or including her social media handles. In contrast, some pins had no inclusion of her name or profile. The ratio between these two sides was generally even. For photos that clearly feature her, there is less of a necessity to credit her because she is a social media personality. Photos that do not include her and go uncredited are not as easily accepted in terms of copyright infringement, however, no part of this case would be considered because she willingly and knowingly shares content to a mass following. The pins that do not credit her do not harm the value of her posts nor is there any likely intent other than inspiration. In our interview, Quincy discussed an instance where a TikTok user stole her videos and posted them on a separate account, directly using her content, creating a new name, adding new captions, and overall attempted to grow a following with her image. That said, this event had no affiliation to Pinterest but represents an example of when using someone else’s content would be considered malicious toward rules of copyright infringement, specifically regarding identity theft.

For this Case Study, there is an additional layer to the discussion of image ownership. As someone who frequently takes photos of Quincy, many pins that credit her as the owner are actually my photographs. I am - technically - the owner of the image and the one who took the photo, yet I am not the one who posted it. Seeing a pin of Quincy that is a photo I took does not bother me, as I am aware of her status and understood that the image would be posted. It is, however, a silent layer of influencer content that does not get considered.

“There have been a few times I’ve seen a picture of myself on my [Pinterest] feed or even one used in a TikTok that's not mine, and I don’t even recognize that it’s me. That will really make me think about how many people can see what I post and how those pictures are just out there for anyone.”

Quincy Whipple, 2024A N A L Y S I S

Pinterest is popular because there is a seemingly never-ending flow of personalized content that is easily accessible. As a platform that promotes creative inspiration, the need for image source inclusion is not a forefront thought for users because there is no serious reprimand for not doing so. Pinterest thrives off of user ignorance toward platform copyright regulations because Pinterest knows that - as a platform - it is never in any serious legal danger due to adherence and implementation of government regulations such as the Doctrine of Fair Use and the Digital Millenium Act. In the age of social media shareability, we actively thrive off consuming visual content in large quantities, fostering a mindset of open-ended use and creating an online environment more focused on curation than credit.

Through my research, I was able to see first-hand how images can easily and often undergo cross-platform travel without the owner’s knowledge. If any photograph is shared on one platform, that does not guarantee that it will remain stagnant in that location. As a creative on social media, my Pinterest search provided an obvious reminder that any image shared to a public account is public. When considering image ownership in a field like photography, it is important to have sufficient evidence that you are the original owner, and - if functioning in the field professionally - have your work copyrighted. As we enter a new, unknown era of technology and AI, the circulation of images that present your physical image can be used without your knowledge. For influencers like Quincy who work within multiple social media platforms, Pinterest can be seen as a cautionary tale and an example of your internet reach.

Pinterest offers only a sliver of photographic content on the Internet. With this surplus existing, copyright infringement cases on Pinterest are difficult and unlikely to be identified unless explicitly searched for. Image theft is common on the platform, but the platform was made for curation and community. The intent of creating pins is seldom done with negative intent, as users seek to pin content they love. When a pin is posted without any form of owner credit, it lends to the loss of creative ownership. When a pin is posted and the user significantly edits or

changes its properties, this strips the elements that made it unique to the owner and is legally wrong. When analyzing copyright infringement on Pinterest, it is the user who gets put at fault for the lack of protection and guidance provided by the platform.

Bosher, H., & Yeşiloğlu, S. (2019). An analysis of the fundamental tensions between copyright and social media: The legal implications of sharing images on Instagram. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 33(2), 164–186 https://doi org/10 1080/13600869 2018 1475897

Carpenter, C C (2012) Copyright infringement and the second generation of social media websites: Why Pinterest users should be protected from copyright infringement by the fair use defense (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2131483). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2131483

Duffy, B E (2016) The Romance of Work: Gender and Aspirational Labour in the Digital Culture Industries International Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(4), 441–457 https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877915572186

Eckhause, M (2022) Fighting image piracy or copyright trolling? An empirical study of photography copyright infringement lawsuits (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4126676) https://doi org/10 2139/ssrn 4126676

Ekstrand, V. S., & Silver, D. (2014). Remixing, reposting, and reblogging: Digital media, theories of the image, and copyright law Visual Communication Quarterly, 21(2), 96–105 https://doi org/10 1080/15551393 2014 928155

Fink, B. (2014). Pinning your way to copyright infringement: The legal implications Pinterest could face. Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum, 4(2), 363. https://doi org/10 58948/2329-9894 1035

Gillespie, T (2018) Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media Yale University Press

Kasakowskij, T., Kasakowskij, R., & Fietkiewicz, K. J. (2021). “Can I pin this?” The legal position of Pinterest and its users: An analysis of Pinterest’s data storage policies and users’ trust in the service First Monday https://doi org/10 5210/fm v26i7 11477

Meese, J., & Hagedorn, J. (2019). Mundane content on social media: Creation, circulation, and the copyright problem. Social Media + Society, 5(2), 205630511983919. https://doi org/10 1177/2056305119839190

Palmieri, I M , & Reid, A (2023) Copyright and shareability: A contractual solution to embedding via social media. Communication Law and Policy, 28(2), 152–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/10811680.2023.2185405