ISSN: 0729-3682 (Print) 2150-6841 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rapl20

ISSN: 0729-3682 (Print) 2150-6841 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rapl20

Julian Bolleter

To cite this article: Julian Bolleter (2019): The limits of spatial design in delivering inland decentralisation in Western Australia’s SuperTowns, Australian Planner, DOI: 10.1080/07293682.2019.1664605

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2019.1664605

Published online: 16 Sep 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rapl20

AUSTRALIANPLANNER

https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2019.1664605

ThelimitsofspatialdesignindeliveringinlanddecentralisationinWestern Australia’sSuperTowns

JulianBolleter

AustralianUrbanDesignResearchCentre,UniversityofWesternAustralia,Perth,Australia

ABSTRACT

Since2011,theWesternAustralianStateGovernmenthasspent$85milliononitsSuperTowns projectthataimedtoboostthepopulationandviabilityofsubregionalcentresor ‘SuperTowns.’ UsingtheWheatbeltSuperTownsofNortham,Morawa,KatanningandBoddingtonthispaper exploreshowlocalgovernmentshaveemployedspatialdesigninterventionstoshifttheimage oftheseinlandtownsinabidtoattractpopulationfromWesternAustralia’smajorurban centres.DespitesixyearshavingelapsedsincethegovernmentinauguratedtheSuperTown policy,demographicdatashowsdecliningpopulationsinthesesubregionalcentres.This paperhighlightsthelimitsofspatialdesigninterventionsinrelationtodeliveringpopulation decentralisationtoinlandtowns.

Introduction

Australiahasadistinctiveformofdevelopmentwith thelargemajorityofitspopulationconcentratedin thecapitalcities(Potts 2003,136;Hugo 2012,17).In thefollowingbackgroundsection,Isetouthowthis patternhasemergedandprovideabriefhistoryof attemptstocounterthissituation.Thisinformationis importantbecausetheWesternAustralianSuperTownsprogram – whichisthefocusofthispaper –aimstosiphonpeoplefromPerthandothermajor urbancentrestosubregionalcentres.

Background

CapitalcityprimacyinAustralia Australiahasformanyyearsbeenoneofthemosturbanisedcountriesintheworld(Potts 2003,136;Hugo 2012,17).Thisisduetothepatternofadministration, whichdevelopedfromthetopdownwardsincomparisontoelsewherewhereitdevelopedfromlocalgovernmentupwards.Moreoverintheearlierdaysof Australia’ssettlement, ‘itwasassumedthatnogood thingcouldcomeoutofAustralia[and]theleadingsettlers,professionalandcommercialmenlookedtothe daywhentheycouldreturntotheirhomeland’ (Potts 2003,140).Climaticconditionsalsohelptoexplain theunevendistributionofpopulation – largesections ofcentralandwesternAustraliaarearidandsuitable onlyforextensiveformsofgrazing(Lonsdale 1972, 322).Overtimepowerfulcommercialinterestsandthe metropolitanpresshavecompoundedthiscentralising tendency(Potts 2003,140).Asaresultofthesefactors bythelatecolonialera,apatternofmetropolitan

CONTACT JulianBolleter julian.bolleter@uwa.edu.au

ARTICLEHISTORY

Received10November2017

Accepted3September2019

KEYWORDS Decentralisation;ruraltowns; ruraldecline;Wheatbelt; SuperTowns;primacy

dominancehadsolidified,whichWeberdescribedas ‘ a remarkableconcentration’ (InFreestone 2013,236). InAustraliasincethe1980sthisconcentrationhas furtherincreased.Population flowsfromtheinland agriculturalregionstotheexpandingcoastalurban centres,havecreatedwhatBernardSalttermsthe ‘empty-islandsyndrome’ (InKullmann 2013,243). WhiletheextremelyaridconditionsofAustralia’ s interiorhavealwayscurtailedinhabitationinland,in thelatterpartofthetwentiethcenturythepopulation differentialbetweenurbanisedcoastalareasandinland ruralareaswidenedsignificantly(Kullmann 2013, 243).Increasingly,manyAustraliansdon’tdependon orliveintheAustralianinterior:theyliveinsteadin the fivemainlandcapitalcities,whichareconnected more ‘totheoutsideworldratherthantotheAustralian landscape’ (Diamond 2011,388).

Combating ‘territorialimbalance’ through decentralisation

InresponsetoAustralia’ s perceived ‘territorialimbalance, ’ inwhichpopulationandeconomicopportunity ishighlyconcentratedinmajorcities,therehave beennumerousattemptsatpopulationdecentralisation intoruraldistricts(Lonsdale 1972,323).Theseprogramsdrewinspirationfromexamplesinternationally. InBritain,thepost-WorldWarTwonewtownsprogramsawsubstantialpopulationsdecantedfromthe majorcitiestonewtownssuchasMiltonKeynes,in whatcommentatorsatthetimeregardedasa ‘triumph ofBritishplanning’ (Berkley 1973,479).1

InAustraliadecentralisationprogramsweredriven byavarietyofbeliefs(Bolleter 2018),includingthe fearthatan ‘empty’ landonAsia’sdoorstepwouldinvite

plunder(Daleetal. 2014,9),thebeliefthat ‘apeople evenlydistributedinsmallormediumsizedtowns tendtobestronger,morallyandmentallyaswellas physically,thanoneconcentratedinafewbigcities’ (C.E.W.BeaninFreestone 2013,237).Moreover,commentatorsfeltthatadecentralisedpopulationwassafer fromaerialbombardmentinwartime(Davison 2016a, 97),and finallythatbuilding ‘beautiful’ newtownsclosertoourfoodsupplywasamorebalancedurbanand agriculturaloutcome(InFreestone 2013,237).

Someofthenumerousattemptsatinlanddecentralisationaresetoutbelow.Inthe1890sdepression,with highunemploymentinthebigcities,thereweremoves tocreatenewcooperativevillagesettlementsinrural areas.Theywere ‘merespecksbuttheycapturedarising tideofanti-metropolitanismcriticaloftheparasitical waysofthecoastalcapitals’ (Freestone 2013,236). Post-WorldWarOnetherewasawaveofpro-developmentliterature,whicharguedthattheagricultural potentialofinlandAustraliahadbeenpreviouslyunderestimated.ForemostofthesewritingswasEdwinBrady’ s AustraliaUnlimited(Frost 2004,286).WhileBrady’ s imageofmillionsofpeoplelivingandfarmingthe interiorwereneverrealisedpostWorldWarOne thereweresoldier-settlerandirrigationschemeswhich yieldedanew ‘sprinkle’ ofsmallurbansettlementsin ruralareas(Freestone 2013,237).

AtthetimeofWorldWarTwo,theofficialorganof theNationalCatholicRuralMovementclaimedthat ‘thebombingplanewithitsawfulpowersofdestructionshowssoclearlythefallacyofconcentratingour resourcesinbigcities’ (Kilmartin 1973,37).Soon afterthewarended,withAustralia’scapitalsstillintact, SirPatrickAbercrombietouredAustralia,preaching thevirtuesofhis1944LondonPlan. ‘Decentralisation’ , ‘satellitecities’ and ‘greenbelts’ quicklybecamepartof Australianpublicdiscourse(Davison 2016a,97) althoughsuchthinkingwastoyieldlittleintermsof populationdecentralisation.

Buildingonsuchplanningideology,PrimeMinister GoughWhitlamaddressedauniversityaudienceon ‘MakingNewCities’ in1970withtheexpectation thatbytheyear2000therecouldbe ‘ manymore than five newCanberrasdistributedacrossourgreat continent’ (InFreestone 2013,240).TheWhitlamgovernmentestablishedtheDepartmentofUrbanand RegionalDevelopment,inpart,tooverseesuchmassive populationdecentralisationfromthebigcitiestothe regionshowevertheincomingFrasergovernmentdismantledthe ‘GrowthCentres’ programin1975,withoutitachievinganynoteworthyprogress.Subsequent tothis,anythingakintoboldernationalsettlement ideashave ‘remainedonhold’ (Freestone 2013,241). Moreover,wheredecentralisationawayfromthe five maincapitalcitieshasoccurred,ithasbeentypically tomushroomingcoastalcentresnotinlandrural towns(Kullmann 2013,243).

OutflowofpopulationfromWesternAustralia’s Wheatbelt

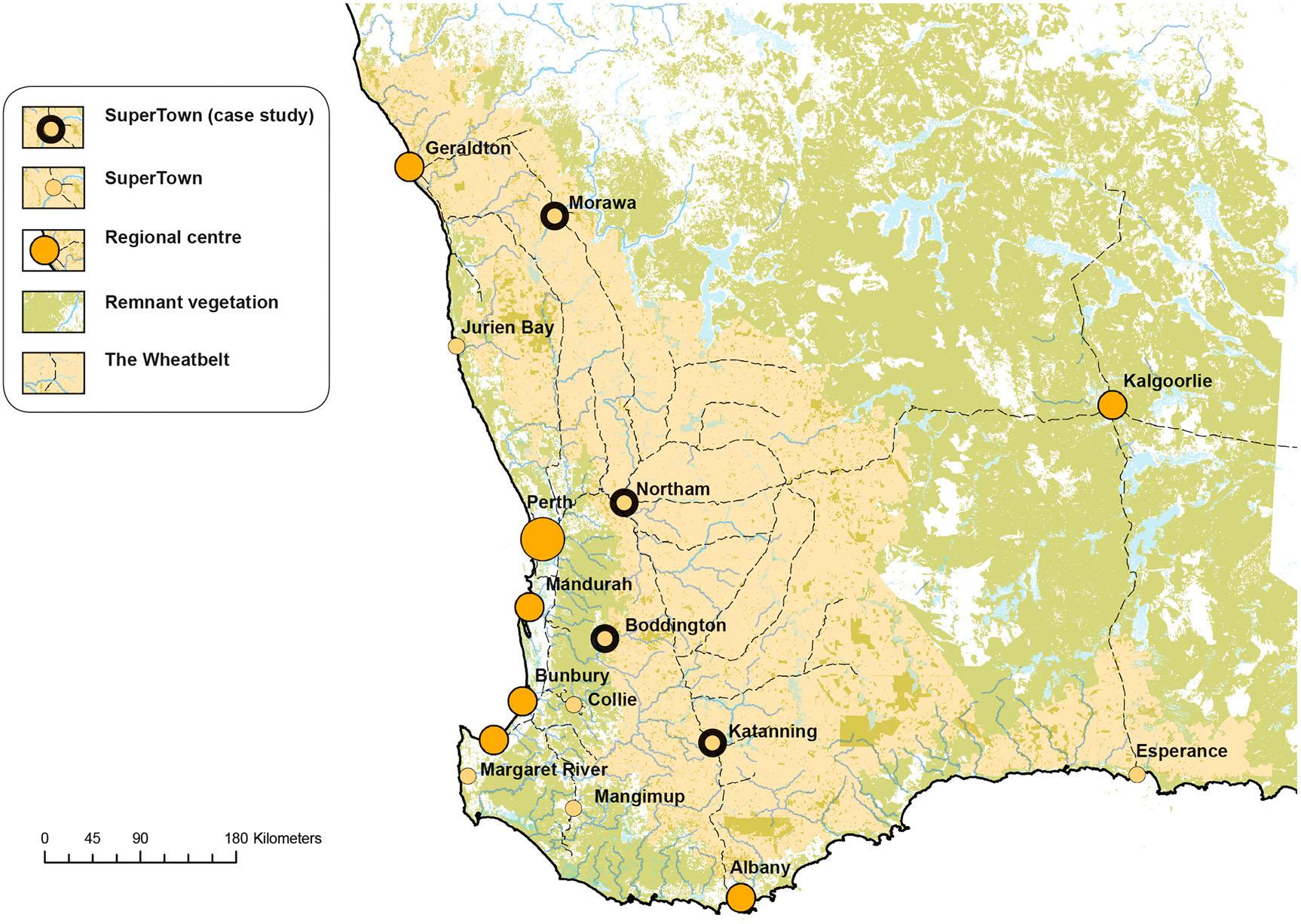

LikeAustralia,theurbanisationofpopulationinWesternAustraliaisextreme,andthecontinuinglossof populationfromruralandregionalareastolarger regionalcentresandmajorurbancentresalongthe temperatecoasthasbeenevidentfordecades(Alan BurnsandWillis 2011,23).Muchofthispopulation losshasoccurredfromWesternAustralia’svast Wheatbelt,thestate’smostimportantagricultural area,whichliestotheeastofPerth – anareathatis thegeographicfocusofthispaper(Figure1).This populationlosshasbeencausedbyacombinationof factorsincludingincreasingglobalcompetitionand marketliberalisation(Plummer,Tonts,andArgent 2017,1).Inparticular,the ‘cost-pricesqueezefacing farmers’ hascontributedtofarmamalgamationand expansion,thesubstitutionofcapitalforlabour,farmer outmigration,andthesubsequentreductionoflocal serviceeconomies(Plummer,Tonts,andArgent 2017,1).Thissituationhasbeencompoundedthrough salinisation,soilerosion,watershortagesanddroughts, whichhaveallravagedtheWheatbelt(Diamond 2011, 379)(Figure2).Oneconsequenceofthis,isreduced populationsinruraltownswhichresultsinfewerservices,whichinturnmakeslivinginasmalltown increasinglylessappealing,somorepeopleout-migrate whichcompoundsthesituation(MalanandWright 2015,62).

InresponsetothissituationinruralWesternAustralia, andtheWheatbeltinparticular,aconcertedeffortwas madebythe2008–2017Liberal/NationalWesternAustralianstategovernmenttoinvest25%ofthestate’ s miningroyaltiesintoregionalinfrastructureandservices,apolicyknownasRoyaltiesforRegions.In essence,thestill-operationalRoyaltiesforRegionspolicyisaboutcounterbalancingtheconcentrationof capitalgeneratedbyresourceindustriesinPerth, throughspatialredistributiontotheregions(Chapman,Tonts,andPlummer 2014,82).Asof2017,the RoyaltiesforRegionsprogramhaddelivered$10.9billiontohelpWesternAustralia’sregionalareasgrow into ‘thrivingandsustainablecommunities’ through approximately3500projectsalignedwiththeState’ s PlanningandDevelopmentFramework(WesternAustralianPlanningCommission 2012,25).2

TheRoyaltiesforRegionsprogramisbroadly alignedwithWesternAustralia’ s ‘StatePlanningStrategy2050’ whichistheGovernment’sstrategicplanning responsetothechallengesofmanagingpopulationand economicgrowthintothefuture(WesternAustralian PlanningCommission 2012,5).Policymakershave basedtheRoyaltiesforregionsprogramonprojections thatthepopulationofWesternAustraliawillincrease from2.5millioncurrently,to5.6millionby2056,

Figure1. SuperTownslocationmap.

Note:ThismapshowsWesternAustralia’sdesignatedRegionalCentresandthenineSub-RegionalCentres,orSuperTowns.TheSuperTownsbeingreviewed inthispaperareNortham,Katanning,BoddingtonandMorawaallofwhicharelocatedintheWheatbelt.

Figure2. SalinisationintheWheatbelt.

Note:MuchofthepopulationlossfromruraltourbanareashasoccurredinWesternAustralia’svastWheatbeltwhichliestotheEastofPerth.Thispopulation losshasbeencausedbysignificantadjustmentstoboththestructureandfunctioningofruraleconomiesandhasbeencompoundedthroughsalinisation, soilerosion,watershortages,andman-madedroughts(photocourtesyofJeanandFredwheatbeltscience.org.au/project/yenyenning-lakes/ https://www. flickr.com/photos/jean_hort/40209134835/in/photostream/).

equivalenttoanadditional3.1millionpeople.Inabid todeliver ‘sustainablesettlementpatternsandpopulationcompositionswithinandbetweenthegreater PerthmetropolitanareaandregionalWesternAustralia’ theplanlookstoregionalexpansionin11regional centres3 nineSub-RegionalCentres,orSuperTowns (WesternAustralianPlanningCommission 2012,17).

TheSuperTownsareBoddington,Collie,Esperance, JurienBay,Katanning,Manjimup,MargaretRiver, MorawaandNortham(DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2016b,31)(Figure1).Thesesub-regional centrestypicallycontainservicesandfacilitiessuchas ahighschool,districthospital,commercialcentre withmultipleretailoutlets,supermarkets,specialty andconveniencestoresandcommunityentertainment facilitiesincludingdistrictsportingcentres(DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2016a,6).

PolicymakershavetaskedtheSuperTownsprogram asdelivering ‘anetworkofdynamicandgrowing regionalcentres’ whichare ‘enormouslyvibrantand attractiveplacestodobusiness,workandlive’ (DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2011,3).Moreover,as withtheRegionalCentres,policymakershaveportrayedthem,asasolutiontoarapidlygrowingpopulationinthecapitalcityofPerth.AsBrendanGrylls (thenstateRegionalDevelopmentminister)explained in2011:

Thereisalotofdiscussionaboutthegrowthofour population,thestrongWesternAustralianeconomy andwherearepeoplegoingtogo.Thereisanargumentaboutinfillandurbansprawl,anditwould justseemtobeanaturalprogressiontolookat wheretheinfrastructureislocatedoutsideofPerth andlooktobuildonthat.Toattractmorepeopleto livewherethejobsareandwheretheeconomic growthiscomingfrom.Theywanttoknowabout theschools,knowifyoucanbuyanicecoffeeinthe mainstreet,andthey’rethetypesofthingswe’relookingtoaddressunderthepolicywe’reproposing(AustralianAssociatedPress).

Inshort,theSuperTownsDevelopmentPlanaimedto givethesesubregionalcentresthecapacity,vibrancy, andeconomicopportunitiesthatwouldprovidean attractivechoiceforpeoplewantingtoliveinregional towns(DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2011,4).4

TodatetheRoyaltiesforRegionsprogramhas invested$85.5milliontoestablishtheSuperTowns (DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2017). ThroughlocalgovernmentGrowthPlans,policymakersidentified17priorityprojectsacrossthenine townsandtheDepartmentofRegionalDevelopment providedthemwithrelatedRoyaltiesforRegions funds.Ofthisfundingapproximately82%hasbeen spentonspatialdesignrelatedtowncentre,touristprecinctandwaterfrontredevelopmentprojects,8%on

agriculturalexpansion,6%onhealth,2%oneconomic developmentand2%onwaterandenergyinfrastructure(DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2017).5 TypicalprojectsincludedCollie’sCentralBusinessDistrictRevitalisation,Northam’sAvonRiverRevitalisationandRiverfrontDevelopmentandAvonHealth andEmergencyServicesPrecinct,andBoddington’ s EconomicDevelopmentImplementation.Despite importanteconomicorhealthrelatedprojects – such asIhavejustlisted – theoverwhelmingfocusofthe GrowthPlanswasonspatialdesigninitiatives,particularlymainstreetupgrades.

AlsooutlinedintheseGrowthPlansistheestimated populationgrowthoverthedecades.Theseprojections areextremewithSuperTownssuchasMorawaexpectinga280%populationincreaseby2041(ShireofMorawa 2012,59),Northama300%increase(Shireof Northam 2011,13)andKatanninga360%increase (ShireofKatanning 2012,13).

Giventhesubstantialamountofpublicmoneythatstate andlocalgovernmentshaveinvestedintheSuperTowns since2011,andthedegreetowhichpolicymakershave spentthismoneyonspatialdesign6 interventions,this researchpaperasksthetwoquestions:

Howhavelocalgovernmentsemployedspatialdesign toincreasetheattractivenessoftheWheatbeltSuperTownsforpeopledwellinginlargerurbancentres?

Secondly:

Havethesespatialdesigninterventionsbeenresponsibleforsignificantpopulationdecentralisationto theWheatbeltSuperTowns?

Theresearchmethodthatthispaperadoptstoanswer thisformerquestionisan ‘interpretivecritique’ (SwaffieldandDeming 2010,43)whichIemployto revealnewunderstandingsandperspectivesupon spatialdesignpracticeintheSuperTowns.Through theanalysisofspatialdesignpropositions,Iseekto understandthemessagestheseinterventionscommunicate – andhowthesemayattractresidentsoflarger urbancentres.Iexplorethelatterresearchquestion usingan ‘evaluative’ methodology(SwaffieldandDeming 2011,40)inwhichrecentAustralianBureauof Statistics(ABS)demographicdataisusedtomeasure thesuccessorfailureofpublicinvestmentintheSuperTownsfromtheperspectiveofpopulationgrowth throughdecentralisation.

Toaddressthesequestions,Ihavestructuredthis paperintwoparts.The firstoftheseprovidesadescriptionofthecurrenturbanformoftheSuperTownsand explorestheprinciplespatialdesigngesturesinvolved intheupgradingoftheSuperTowns,andhowthese gesturesseektoovercomepsychologicalbarriersto

decentralisation.Theseconddiscussesthelimitsof spatialdesignwithrespecttodeliveringpopulation decentralisationfrommajorurbancentres(especially Perth).Iconductthisdiscussionwithreferenceto recentdemographicdatafortheSuperTowns.Finally, giventhelimitsofspatialdesignexercises,Iconsider whatalternativestrategiestheWesternAustralian stategovernment,andinsomecaseslocalgovernments,couldimplementtoyieldsomeinland decentralisation.

Becauseofthenecessarybrevityofthisresearch paper,IfocusprimarilyontheinlandWheatbelt SuperTownsofMorawa,Northam,Boddingtonand Katanning.ThisisbecausetheseSuperTownsoccur inonegeographicunit(i.e.,theWheatbelt)and becausetheyareinlandtowns.Theother,coastal, SuperTownstypicallyhaveorganicallygrowingpopulations(AlanBurnsandWillis 2011,23),andwhich areexpandingforreasonsotherthanthoseestablished throughSuperTownplanning(Kullmann 2013,243).

Whiletherehasbeensomecursoryanalysisofthe SuperTownsPlanintermsofthepublicmoney spent,andthepopulationdecentralisationwhichhas sofaroccurred(Walkeretal. 2017),therehasbeen nocomprehensiveanalysisofhowspatialdesignhas beenemployedtothisendandindeedwhetherithas beensuccessful.Thispaperbringsscholarlyattention tospatialdesignpractice,whichhasotherwiseevaded scrutiny.

Partone:thedeploymentofspatialdesign toovercomepsychologicalbarrierstoinland decentralisation

Thefollowingsectiondescribestheurbanmorphology ofthecasestudySuperTowns.Subsequently,itexplains howlocalgovernmentshavedeployedspatialdesignto shifttheimageofsuchtownstoincreasetheirattractivenessforresidentsoflargerurbancentres.7

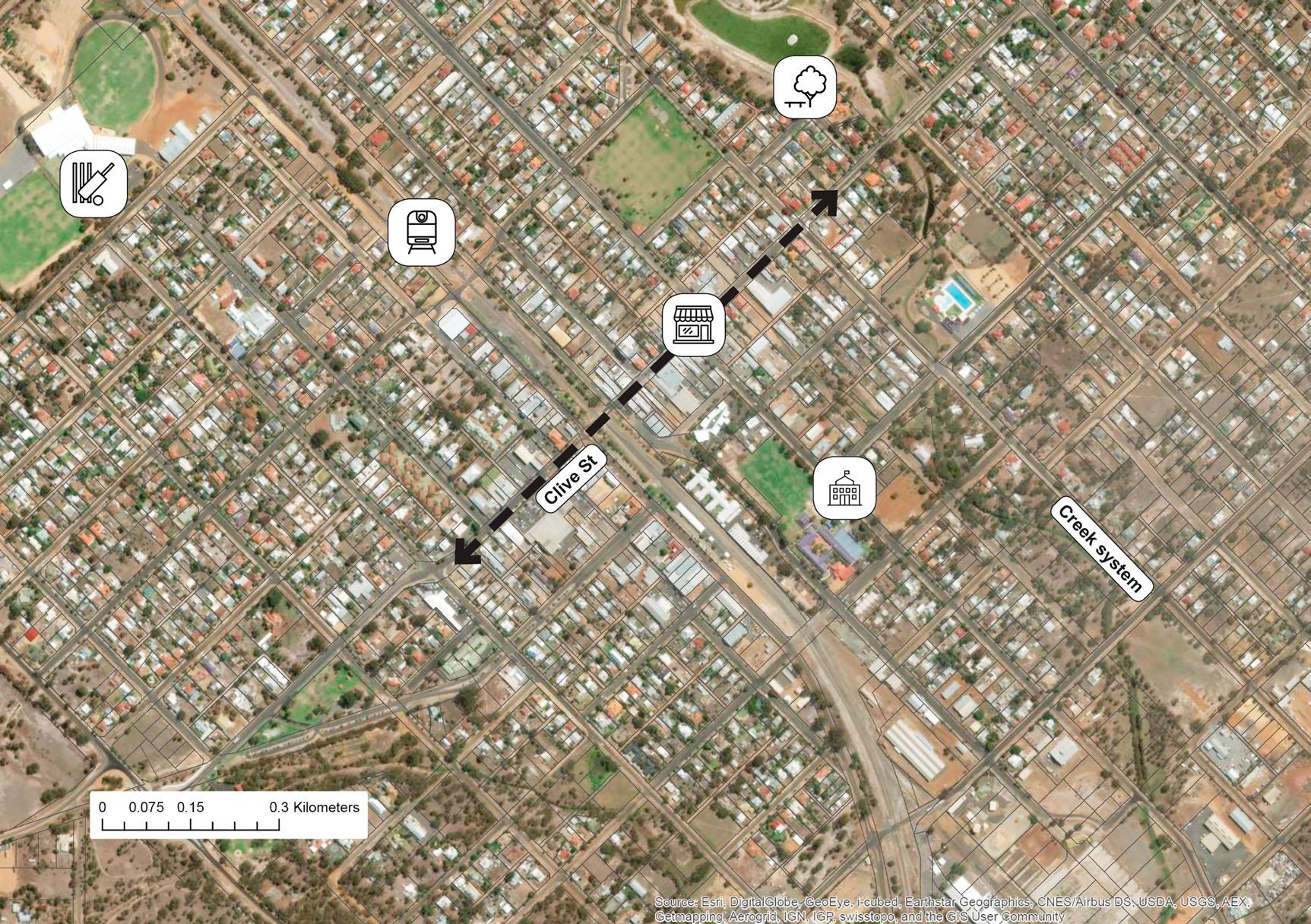

ThecasestudySuperTownsNortham(foundedin 1833),Katanning(1898),Boddington(1912)and Morawa(1913)aresmalltowns,whichhavepopulationsof6580,4325,1107,and655respectively.The townsarestructuredbygriddedstreetsystemsand theurbanfabricconsistsoflowdensityfreestanding houseswithhistoriconetothreestoreyarchitecture containingcommercialandcivicfunctionsconcentratedonacentralmainstreet(HamesSharley 2012, 74)(Figures3–7).Whilethetowncentresandmain streetsprovidesaplaceforresidentstogatherand shop(HamesSharley 2012,10)muchofthepublic lifeoftheSuperTownsoccursatthegolfandlawn bowlsclubswhichareaparticularfocusforcommunity interaction(ShireofMorawa 2012,46).This,in

conjunctionwithgenerallydwindlingpopulations, meansthatvacantandunderutilisedlotsandbuildings aretypicalofmanyofthestreetsintheSuperTowns (ShireofKatanning 2012,23;ShireofMorawa 2012, 36).

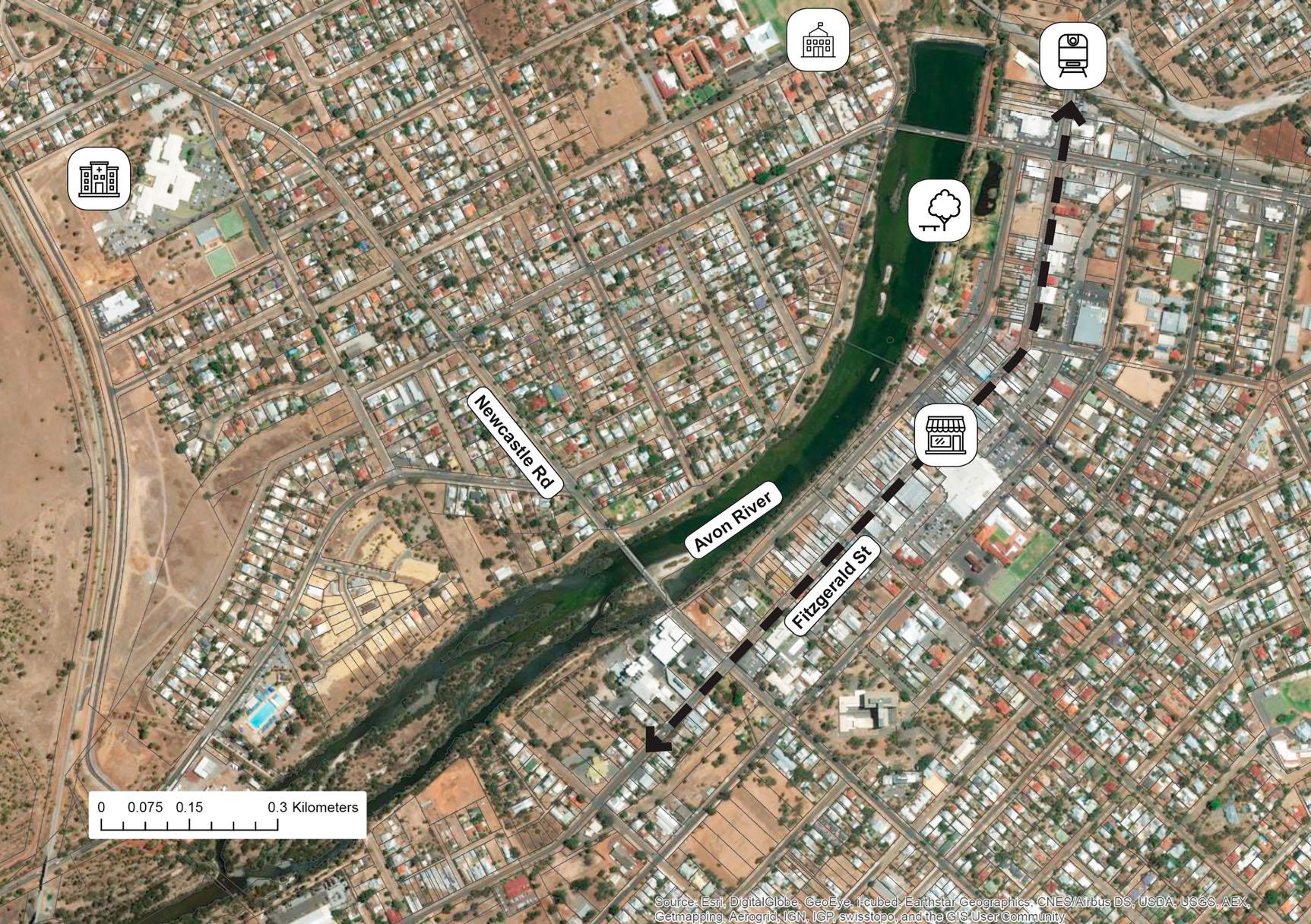

Severalthetownshaveariverorcreeksystem, whichrunsthroughthetown,inNorthamtheAvon River,inBoddingtontheHothamRiver,andinKatanninganunnamedcreek.Oftenthetownsbackonto theseassetsandassuchthereisnotaclearrelationship betweenthesehydrologicalsystemsandtherespective townsites(HamesSharley 2012,74).Moreoverin somecasesthesesystemsareinpoorenvironmental condition(ShireofKatanning 2012,23).Publicopen spaceaboundsintheSuperTowns,howevermuchof itisunderutilised.

Thefollowingsectionexploresspatialdesign interventions – namelyrejuvenatingmainstreets, introducingcivicplazas,andrepairingandconnectingtoenvironmentalassets – thatlocalgovernments havedeployedinabidtoovercomethepsychologicalbarrierstopopulationdecentralisationtosuch towns.InAustralia,manypeopleregardinland ruraltownsassufferingfromanimageproblem. Dwellersinlargerurbancentrestendtoviewcountry townsasboring,shortofattractions,havinglesseducationalopportunities,andprovidingalimitedsocial scene(Lonsdale 1972,327).Asonecitywriterputit, ‘there’snothingtodointhecountrytownoncethe pubsshut.’ Suchattitudesareobviouslybiased,but theyhighlightanimportantpsychologicalcomponenttotheproblemofachievingdecentralisation (Lonsdale 1972,327).

Localgovernmentshaveprincipallydeployedmain streetupgradestoincreasetheattractivenessofthe SuperTownsforresidentsandvisitors(Figures8–12). AsHamesSharley,plannersfortheBoddingtonSuperTownexplain:

TheactivationofMainStreetprojectshouldrelyon principlesofPlace-Makingincludingthetransformationofpublicspacesintovibrant,welcomingplaces whichareabletosupportsustainandinspirepresent andfuturecommunitiesofresidents,workersandvisitors(HamesSharley 2012,127).

TothisendSuperTownmainstreetupgradestypically includedentrystatements,featurepaving,coordinated streetfurniture,orderedtreeplanting,theretentionof heritagebuildingsandthepluggingof ‘ gaps ’ between buildingsthroughurbanconsolidation.InMorawa’ s SuperTownplanning,designersintendedtoimprove builtformalongthemainstreet,WinfieldStreet, throughincentivesforlocalbusinessownersto upgradethebuildingfacadesaswellasthrough

Figure3. AustraliaTerraceinKatanning.

Note:Theprosperity,andultimatelyviability,ofAustraliancountrytownscanbemeasuredinanumberofwayshoweveroneconsistentbenchmarkisthe appearanceandvibrancyofthemainstreet(photocourtesyofGlenysDavies).

Figure4. Northam.

Note:TheSuperTownsgenerallyarestructuredbygriddedstreetsystems.Theurbanfabricconsistsoflowdensityfreestandinghouseswithhistoriconeto threestoreyarchitecturecontainingcommercialandcivicfunctionsconcentratedonacentralmainstreet(backgroundimagecourtesyofArcMap).

streetscapeimprovements.Asaresult,itwasbelieved thatnewbusinesses,investors,touristsandvisitors wouldbeattractedtothecentre,thereby ‘creating additionalpressuretoredeveloporupgradeexisting tenancies’ (ShireofMorawa 2012,96).Inthisrespect theWinfieldStreetrevitalisationprojectwasregarded

Figure5. Katanning(backgroundimagecourtesyofArcMap).

Note:PublicOpenSpaceaboundsintheSuperTowns(backgroundimagecourtesyofArcMap).

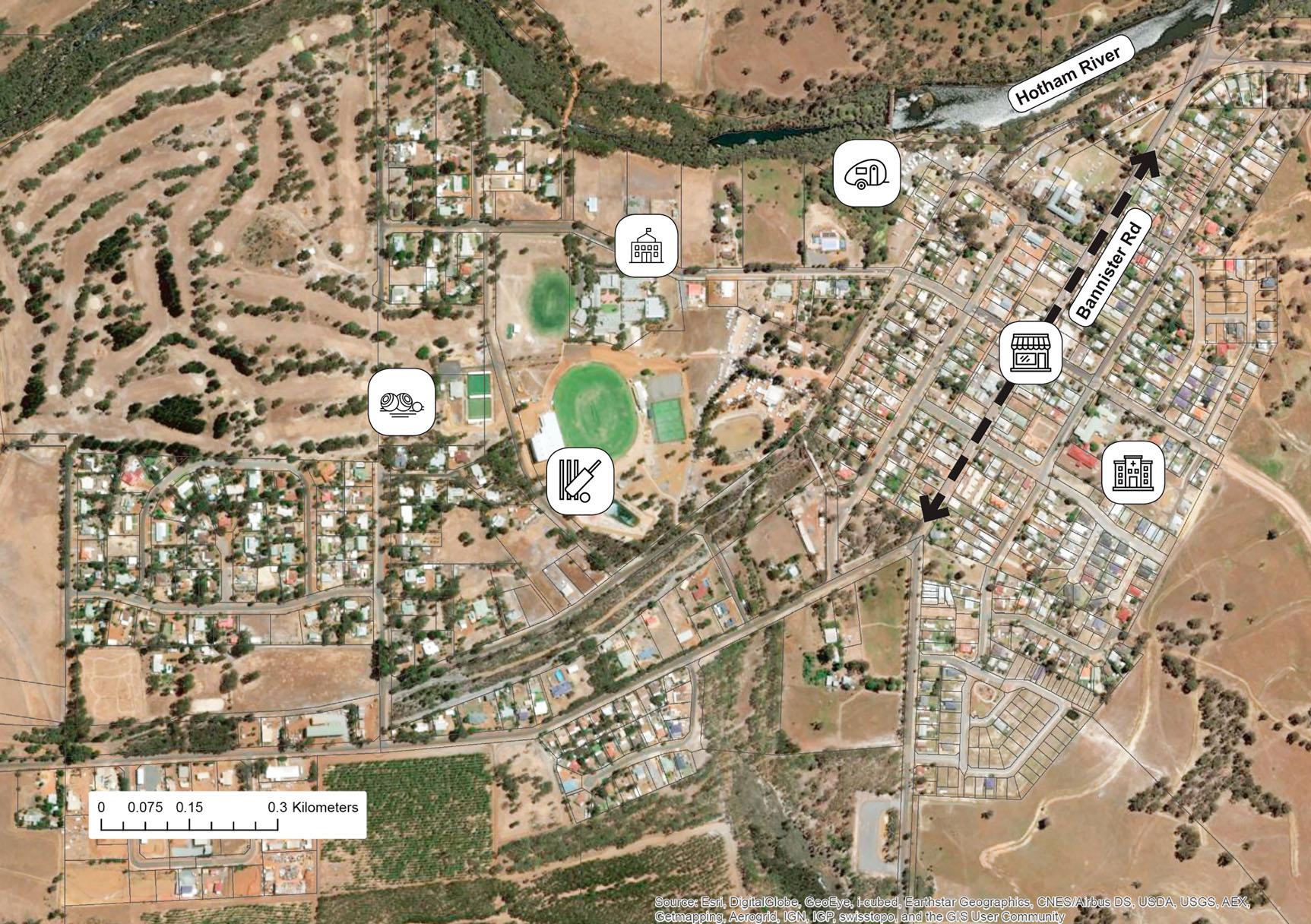

Figure6. Boddington.

Note:Anumberofthetownshaveariverorsmallernaturaldrainagesystemwhichrunsthroughthetown.Oftenthetownsbackontotheseassetsandas suchthereisnotaclearrelationshipbetweenthesehydrologicalsystemsandtherespectivetownsites(backgroundimagecourtesyofArcMap).

asa ‘transformativeproject,inthatitwillenablemany othernewprojects’ (ShireofMorawa 2012,73).In Boddington,plannersregardedthemainstreet, BannisterRoad,aslackinginvibrancyoraclearly recognisablefocalpoint.Variablebuildingsetbacks andstreetscapetreatments,incombinationwith

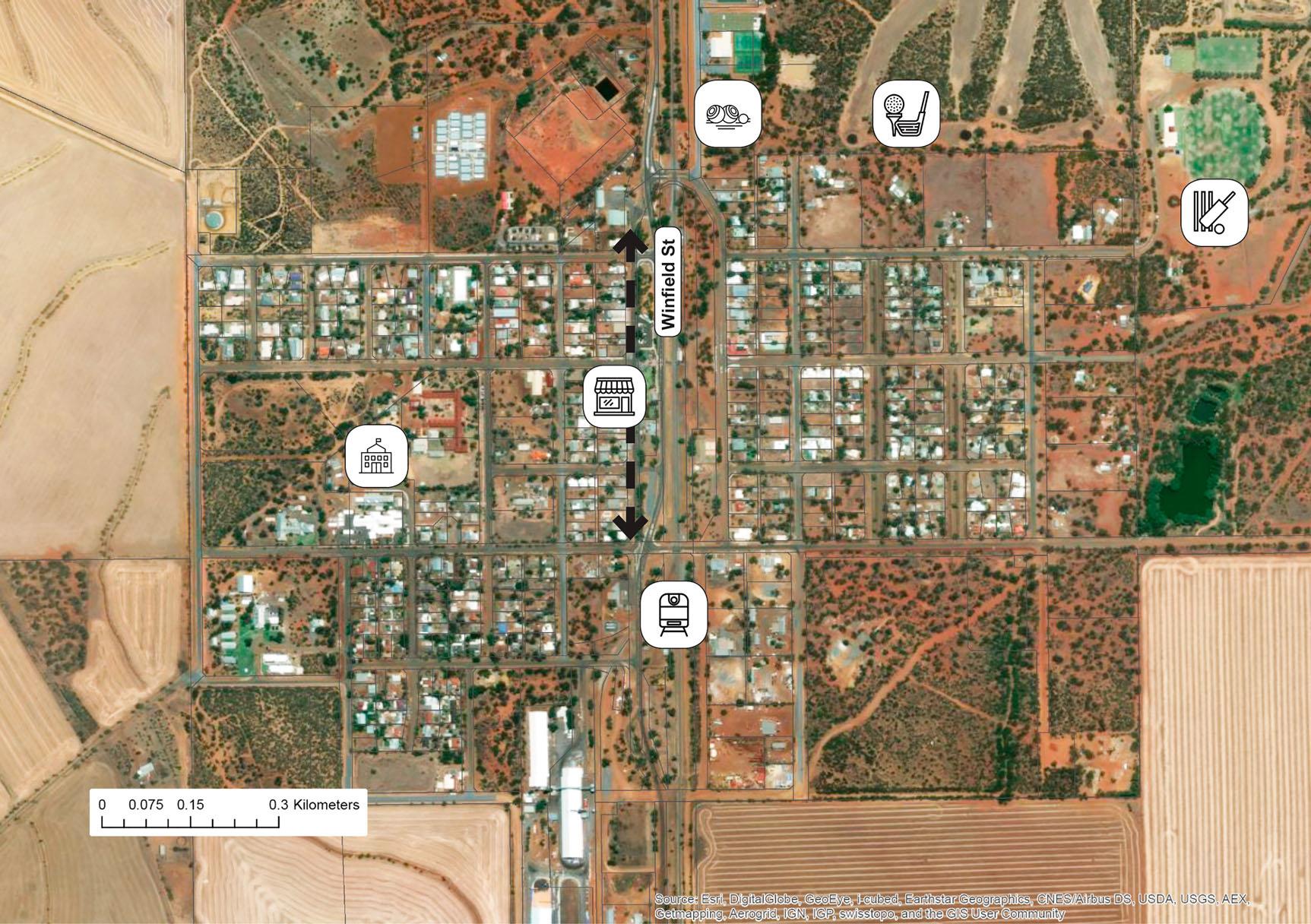

Figure7. AmapoftheMorawaSuperTown.

Note:muchofthepubliclifeoftheSuperTownsoccursatthegolfandlawnbowlsclubswhichareaparticularfocusforcommunityinteraction(background imagecourtesyofArcMap).

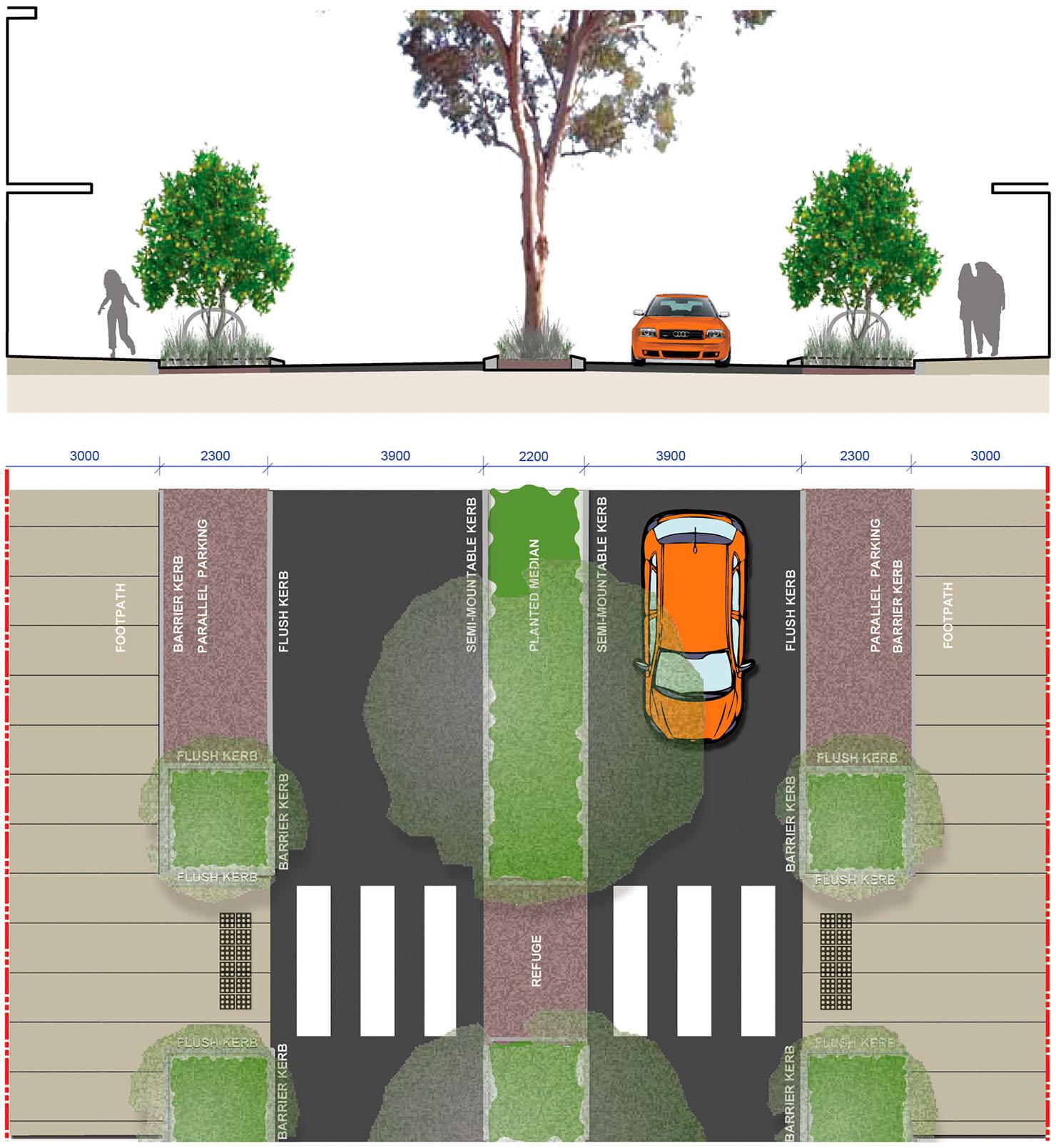

Figure8. Katanningstreetscapeupgradesplan.

Note:PlannershaveprincipallyusedmainstreetupgradestoincreasetheattractivenessoftheSuperTownsforresidentsandvisitors.This figurefromthe KatanningSuperTownGrowthandImplementationPlanshowsstreetscapestobeupgradedandtheproposedtownsquareonthemainstreet,CliveStreet (drawingcourtesyofEcoscape).

Figure9. Katanningstreetscapeupgradessection.

Note:This figurefromtheKatanningSuperTownGrowthandImplementationPlanshowsproposedupgradestoKatanning’smainstreet,CliveSt.Ingeneral theSuperTownmainstreetupgradestypicallyincludedentrystatements,featurepaving,coordinatedstreetfurniture,orderedtreeplanting,theretentionof heritagebuildingsandthepluggingof ‘gaps’ betweenbuildingsthroughurbanconsolidation(drawingcourtesyofEcoscape).

demolishedandvacantbuildingswereregardedascurtailingtheformationofanycohesivesenseofplace (HamesSharley 2012,75).Inresponse,planners regardedthaturbanconsolidationshouldbeusedto plugthese ‘ gaps ’ (HamesSharley 2012,75;Shireof Katanning 2012,83)andassuchengenderastrong senseofplace.

Discussion

Inessencemainstreetupgradessought,inpart,to assureprospectivemigrantsthatruraltownscanoffer potentialmigrantsallthebenefitsofcivilisation(Mirams 2012,278)andurbanitythatlargerurbancentres offer,benefitswhichareoftenneatlysurmisedas alfrescodiningopportunities(ShireofKatanning 2012,93).AsBrendanGryllsexplained,migrants fromthecities ‘wanttoknowifyoucanbuyanice coffeeinthemainstreet …’ (InAustralianAssociated Press 2011),suchasyoucaninlargerurbancentres. IndeedKatanning’sSuperTownplanningmadedirect connectionsbetweenKatanning’sCliveStreet,with

well-knownactivatedhighstreetsinPerthsuchas RokebyRoad,inSubiaco,andBayViewTerrace,in Claremont(ShireofKatanning 2012,90).

Thisfocusonmainstreetupgradesisunderstandable.Theprosperity,andultimatelyviability,ofAustraliancountrytownscanbemeasuredinanumber ofways – includingcensusdata,surveys,interview researchandfocusgroups – howeveroneconsistent benchmarkistheappearanceandvibrancyofthe mainstreet(AlanBurnsandWillis 2011,29).To thisendresearchershaveevenproposedasimple ‘EmptyShopsIndex’ tomeasureruraltownwellbeing (AlanBurnsandWillis 2011,21).Assuch,the deteriorationofcivicandcommercialspaceinthe mainstreetsofWheatbelttownscanrepresentthe most ‘vividface’ ofruraldecline(Kullmann 2013, 252) – particularlyincombinationwithprolonged droughtinthesurroundingfarmingdistricts(Diamond 2011,388).

Towardoff thisperceiveddecline,andprojectan enticingurbaneimage,SuperTownplanningofWheatbelttownshaveallinvolvedmainstreetupgrades.The

Figure10. CliveStreet.

Note:ArecentphotoofupgradestoKatanning’smainstreet,CliveSt(photocourtesyofGlenysDavies).

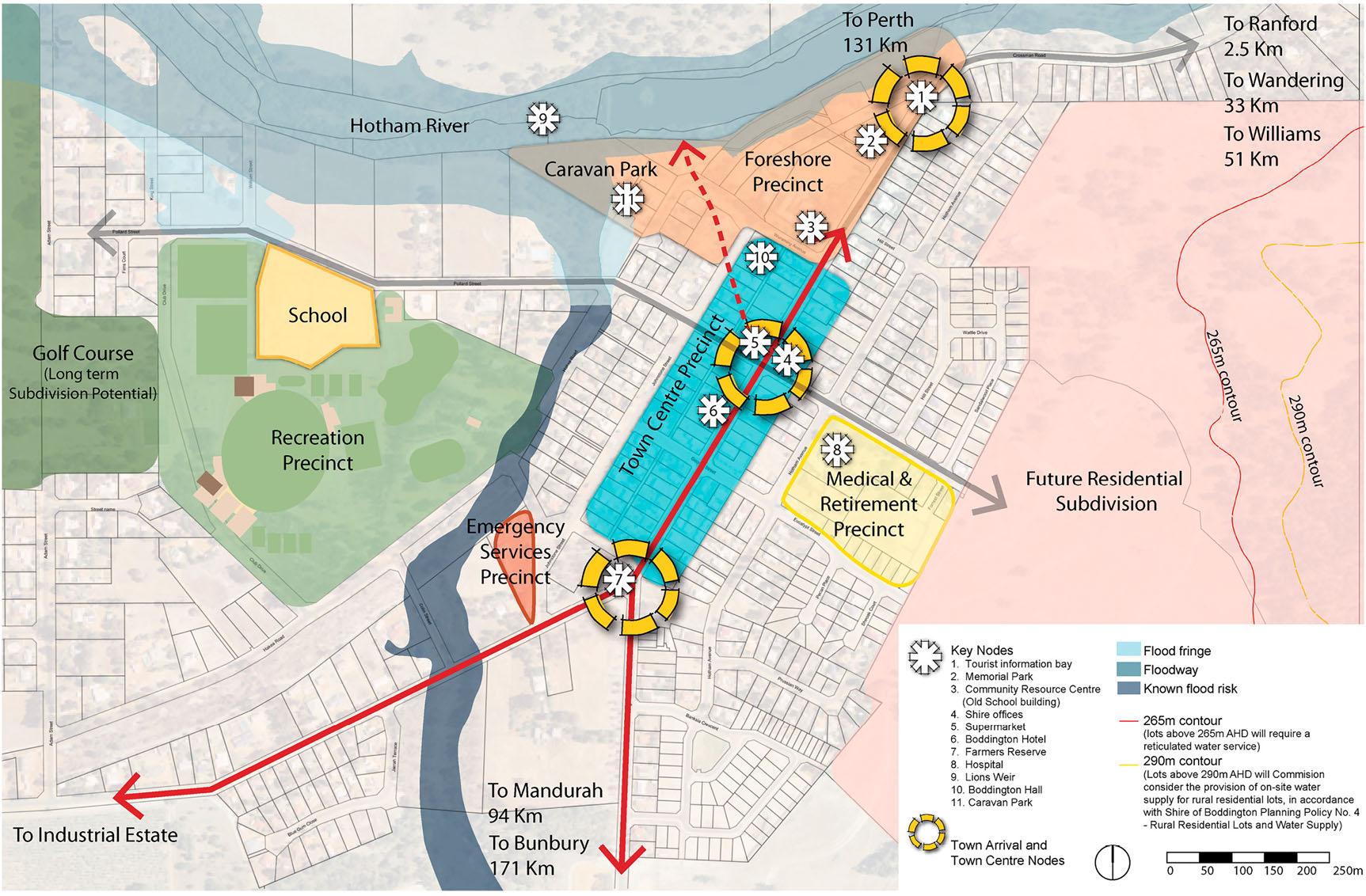

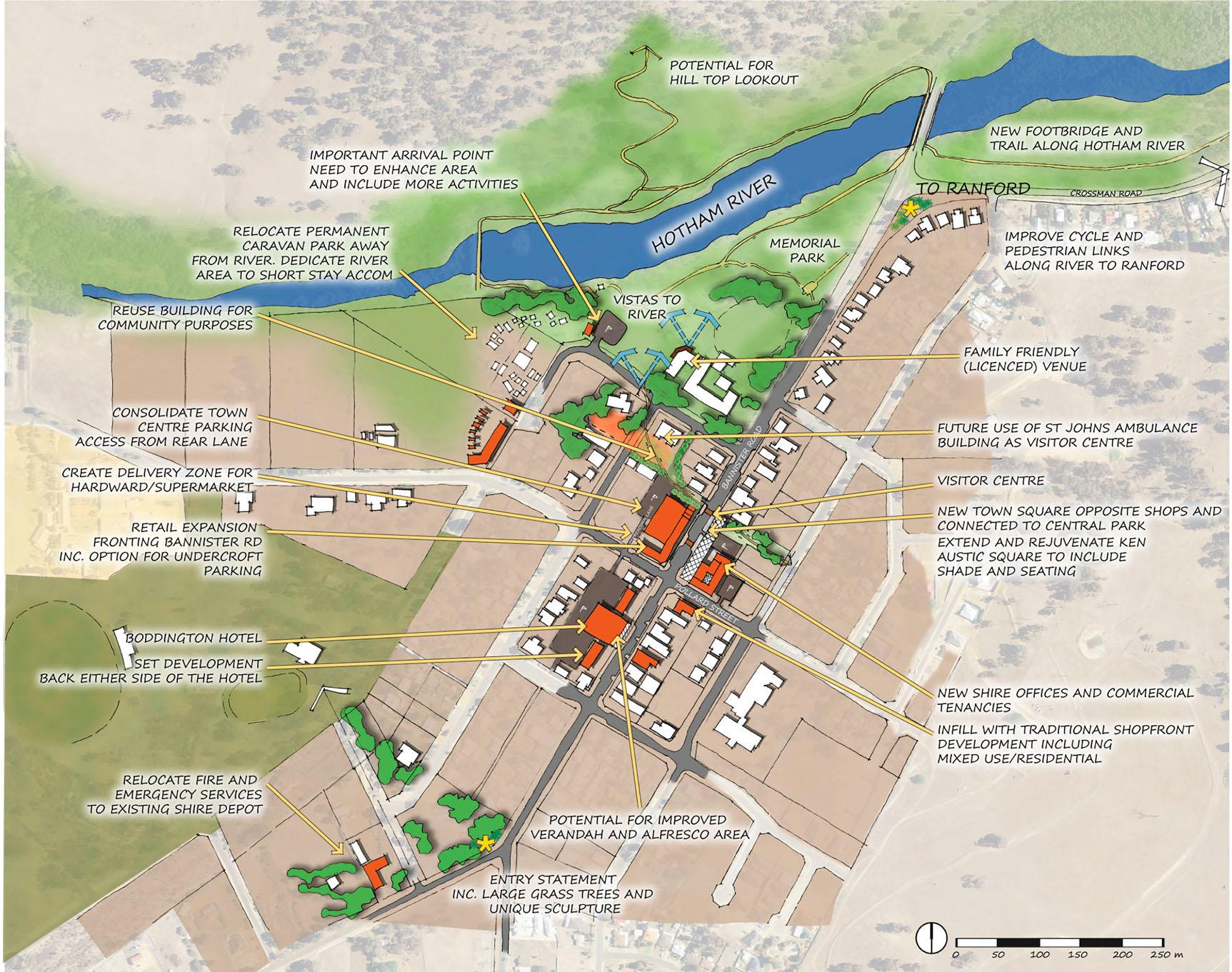

Figure11. Boddingtonnodesandlinkages.

Note:This figurefromtheBoddingtonSuperTownGrowthPlanshowskeynodesandlinkagesalongtheupgradedmainstreet,BannisterRoadwhichplannersregardedas ‘lackinginvibrancyoraclearlyrecognisablefocalpoint’ (drawingcourtesyofHamesSharley).

orthodoxyofSuperTownmainstreetrejuvenation assumesthat ‘permanenceandsolidityarekeycriteria forreversingdecline’ (Kullmann 2013,255).Thus, readerscanconsidersuchupgradesbothspatialand

symbolicincharacter.Asignificantcomponentofthe promotionof ‘permanenceandsolidity’ (Kullmann 2013,255)isthepluggingof ‘ gaps ’ inmainstreets,as discussed.InterestinglyalloftheSuperTownplans

Figure12. Boddingtonkeyprojects.

Note:This figurefromtheBoddingtonSuperTownGrowthPlanshowskeyprojectsprincipallyalongtheupgradedmainstreet,BannisterRoad(drawing courtesyofHamesSharley).

proposeurbanconsolidation(i.e.,gap-filling),over furthersuburbanexpansion,asbeingthepreferred mannerinwhichtoaccommodatefuturegrowth (ShireofNortham 2011,13;ShireofKatanning 2012, 75).Thisisdespitethefactthatthesetownssitwithin thevastexpanseoftheWheatbeltandhavespatiallylittlerestrictiontosprawl – thispointstourbanconsolidation,particularlyinmainstreets,beingproposedin partassymbolicbidtopromoteanimageof ‘ permanenceandsolidity’ ratherthanpurelypragmaticconstraints.Thatsaidincreasedurbandensitycan generateurbanlife,walkabilityandreducecardependency(Farr 2008,44)

Whileimprovingtheamenityofthemainstreet logicallyincreasescivicpride(Kullmann 2013,253) andpotentiallyimprovestheimageofatownforprospectivemigrants,itdoesn’tnecessarilyleadtogreater investmentinthetowncentre,oractivationofmain streets.8 Indeed,manyoftheSuperTownshad,atthe timeofplanning,anexcessofretailandcommercial floorspacemeaningthattherewascertainlyanexisting containerforeconomicdevelopmenttooccurin – and assuchtheproblemswerenotspatialatroot.Inthe caseofMorawa,in2012,itwaspredictedthatgiven eventheinflatedSuperTownpopulationgrowthprojections,thetotalretail floorspacedemandinthe

towncentrewouldnotbeexpectedtoincreasegreatly (ShireofMorawa 2012,61).Moreover,inKatanning itwasregardedthatofthe20%ofcommercial floor spacewithinthetowncentrewasvacant(Shireof Katanning 2012,75).Inshort,theproblemofpoorly activatedSuperTownmainstreetsisnotprincipallya spatialissue – thereisalreadyenough floorspacefor economicdevelopmentthatcouldleadtogreater vibrancy.Rather,therootcauseswhichleadtomain streetdeclineinruralareas – farmamalgamationand expansion,thesubstitutionofcapitalforlabour,farmer andfarmworkeroutmigration(Plummer,Tonts,and Argent 2017,1)arethemajorunderlyingissues.

SuperTownstreetupgradesalsopotentiallyrisk,in theshortterm,theeconomicfunctionofthemain street.Indeedtheproblemofstreetupgrades,in townswhichareoftenalreadystrugglingeconomically, isthatthetradersthemselvescan’tactuallywithstand thedisruptiontotheirbusinessesthatisinevitably causedbystreetscapeworksoutsidetheirshops (MalanandWright 2015,62).Inotherwords,theconstructionofthenewstreetscapeplanthatwascommissionedto ‘revitalize’ thetowncentrecanbetheendof theverybusinessesthattheplanwasdesignedtosupport(MalanandWright 2015,62).Certainlyshop ownersintheKatanningwereangrythemainstreet

revitalisationprojectranovertime,disruptingthemain streetandcostingthembusinessandcausinga ‘dramaticdropinincome’ (Bennett 2014).Thiscanmean thatmainstreetupgradestoachieverevitalisation andactivation,whichproponentspresumedtobe attractivetoresidentsoflargerurbancentres,might threatenthesequalities – particularlyintheshortterm. Despitethebenefitsthatprobably flowedfromthe SuperTownmainstreetupgradesintermsofcivic pride(Kullmann 2013,253),theyareunlikelyto – in themselves – enticeurbandwellerstomigratetorural towns.Thisisinpartbecausemanyofthemainstreet upgradesaspiretoreplicatingsuccessfulhighstreetsin largerurbancentressuchasPerth,andassuchare replicatingwhaturbandwellersalreadyhave.

TheSuperTownplanningfor ‘FutureMorawa’ depictedavibranttowncentrecoalescingarounda newurbanplaza,astheShireofMorawaportrayed: Morawa’sMainStreetisalivewithactivityonthis Saturdayafternoon.Friendlylocalsgatheraround theshadedplazaasitprovidesawelcomingmeeting placetogatheranddiscusstheupandcomingharvest. Acrossthestreet,alocalminerenjoysacoffeewithhis youngfamilyatthenearbycafé.Heoverhearsthejoy expressedbysomepassingtourists,commentingon thevibrantandattractivecharacterofthetownand howtheyintendtostayacoupleofnightsontheir waybackthrough(ShireofMorawa 2012,vii).

InthecaseofKatanning,MorawaandBoddington,the respectivelocalgovernmentsdeployedsmallcivicplazasorsquares,adjacenttomainstreets,inpart,to reshapetheimageofruraltownsforlocalresidents, visitorsandpotentialmigrantsfromlargerurban centres(Figures13–16).SuperTownplanningfor KatanningandMorawaadvocatedtheplazasshould functionasa flexible,activated(onasmanysidesas possible),publicmeetingplaceforthecommunityto meetandinteractandattend ‘regular’ events(Shire ofMorawa 2012,74),dinealfrescoand ‘sitandenjoy thetown’ (ShireofKatanning 2012,62,90).

SpatialdesignconsultantsfortheMorawaplaza, borrowingfromtheProjectforPublicSpaces(PPS) inNewYork,aspiredtotheplazaofferingatleastten thingstodoortenreasonstobethere.Itwasexplained theseshouldincludea ‘placetosit,playgroundsto enjoy,arttotouch,musictohear,foodtoeat,history toexperience,andpeopletomeet’ (ShireofMorawa 2012,67).Beyonddeliveringonsuchambitiousaspirationsforpublicspaceplannersconsideredthattheplazasshouldprovide ‘animportantroleincontributing tothecharacterandappealofthetown’ and ‘would havethepotentialtoinvitetouriststostaylongerin townandwillappealtoandattractpeoplewhoareconsideringMorawaasaplacetolive’ (ShireofMorawa

2012,74).Significantlythedeploymentofurbanplazas inthisruralcontextisoutofstepwiththesociallifeof ruraltownswhichtendstobeconcentratedona recreationprecinctwhichprovidesforarangeofsportingactivities(suchasgolforlawnbowls)andisafocus forcommunityinteractionwithinthetown(Shireof Morawa 2012,46).

ThedeploymentofurbanplazasintheMorawa,BoddingtonandKatanningSuperTownshasaneconomic narrativethatgoesbeyondfacilitatingconviviality. ThisnarrativeisthatSuperTownmainstreet,mixed useprecincts – focussedoncentralurbanplazas –througha ‘diversityofco-locatedlandusesstimulate knowledgediffusionandthuseconomicgrowthand diversification’ (OECD 2012,20).Theattractiveness ofthisnarrativetorurallocalgovernmentsisthat incontrasttothedayswhenAustralia’ seconomy reliedonprimaryproduction,thecontemporary economyisextremelyconcentratedandfocussedon knowledgeintensive,creativejobs(KellyandDonegan 2015,23).Formanypeopleurban,activatedplazas suggestcreativeenvironmentswhichgeneratecreativityandthecommercialinnovationsandwealththat flowfromit(Florida 2002,22;Lang 2016,37).As BrendonGryllsexhortedinrelationtoRegional CentreredevelopmentsinthePilbara: ‘We arelooking tosetuptownsquareswithabitofcultureand lifestylenotcurrentlyassociatedwiththoseplaces’ (Mills 2010).

Certainlythecombinationoffactorsthatmakea ‘creative’ areaaccordingtoRichardFlorida’sestimation – suchasaconcentrationandwidediversity ofpeople,alargevarietyofbuildingssuchasapartments,bars,shops,smallfactoriesandunderutilised structuresidealforcreativeenterprises(Florida 2002, 42) – wasnotbeingdeliveredintheSuperTownplanning.However,theurbanplazas,withtheirattendant localartisanfeatures(ShireofMorawa 2012,74), attempttocatalysesomeofthiselusivecreativityand economicdiversification.Ofcourse,theplazascannot catalysetheknowledgeintensive,creativejobsthat couldconvinceurbandwellerstorelocatetoinland SuperTowns – inisolationfromtheothernecessary ingredients.Nonetheless,itwouldappeartheyremain asasignifierofeconomicdiversificationforrural townadministrators.

Moreover,forthepotentialurbanmigrant,theplaza alsoactsasanantidotetomanyoftheperceivedsocial illsofruralinlandtowns.SociologistA.P.Elkin,who surveyedthecountrytownsofNewSouthWalesin theearly1940sidentifiedthe ‘ suffocatinghomogeneity, ofruralsociety’ whichwas ‘unrelentinginitsdemands forconformity’ (InDavison 2016a,155).ThedeploymentofurbanplazasintheruralSuperTownssignifies amoreurbanattitudetodiversityinwhichthe ‘urban

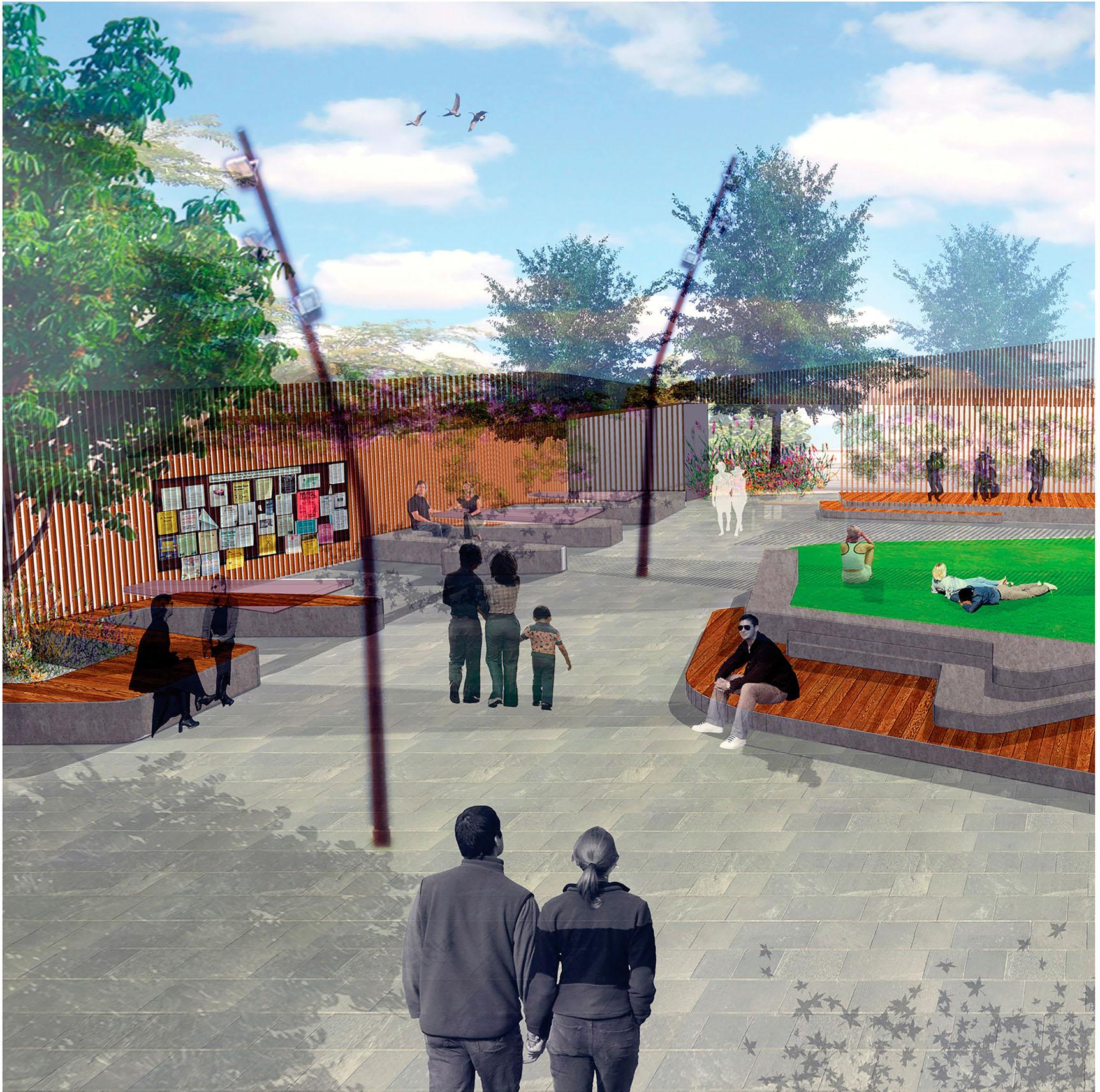

Figure13. Katanningcivicplazarender.

Note:ArguablythecivicplazasorsquareswhichweredeployedinSuperTownplanning,inpart,toreshapetheimageofruraltownsbothforlocalresidents butalsovisitorsandpotentialmigrantsfromlargerurbancentres(imagecourtesyofRPSEnvironment).

communitydisplaysmereindifferencetotheeccentricitiesofitsmembers’ where ‘strangersbecomefellow citizens’ (Davison 2016a,268).

Finally,theircommissionerspresumeplazasto functiontoreinforceasenseofbelonging.Within thecontextofthevastWheatbeltravagedbyover clearing,salinisation,soilerosion,pestsanddroughts (Diamond 2011,379),theplaza,drawingonthesymbolismofthecitysquare,agora,andforum,actsasa siteofcivicbelonging ’ (Davison 2016b,211).While ‘ thebush’ andtheopennessofthecountryisentwined withlandscapepublicopenspaceininlandrural towns,intheseurbanplazasthesequalitiesarepartly diminished.Indoingthistheneatlydelineatedplaza potentiallysatis fi esapsychologicaldesireforboundednesssometimesexperiencedbythosevisitingorlivingininAustralia ’swideopen,hostile,interior landscapes.AsSusanBrightobservedoftheWheatbelt, ‘ theheat,thelonelinessandthepressuresof smallruralcommunitiesarepalpable ’ (Kullmann

2013,247).Thedesireto ‘ plugthegaps ’ inSuperTown urbanstructure(HamesSharley 2012 ,75;Shireof Katanning 2012,83),withalltheirvaguenessand unease,reachesitszenithintheseplazaswhichprovidearationalorderingof,whatcanbeforvisitors, ‘strangespace ’ (DoveyandSandercock 2005,30).Of coursegiventhelowpopulationdensityofKatanning andMorawafortheplazasthemselvestonotbecome windsweptandvacanttheyrequirecarefulmanagementofsocialandculturalfestivitiesyearround (ShireofMorawa 2012,50).

Repairing,andconnectingto,environmental assets

TheWheatbelt,inthemindofresidentsofWestern Australia’smajorurbancentres,tendstobethought ofintermsofenvironmentaldestruction(Kullmann 2013,250).Thissituationisnoaccident – ofthe Wheatbelt’soriginalnativevegetation,90%hasnow beencleared,mostlybetween1920and1980,

Figure14. PhotographoftheKatanningcivicplaza.

Note:GiventhelowpopulationdensityofKatanningandMorawafortheplazastonotbecomewindsweptandvacanttheyrequirecarefulmanagementof socialandculturalfestivitiesyearround(imagecourtesyofRPSEnvironment).

culminatinginthe ‘MillionAcresaYear’ program pushedbytheWesternAustraliastategovernmentin the1960s(Diamond 2011,403).Inpartasaresult, theproportionoftheWheatbeltsterilisedby

salinisationisexpectedtoreachone-thirdwithinthe nexttwodecades(Diamond 2011,403).Withinthis context,planningforimprovedenvironmentalhealth intheSuperTownsistimely.

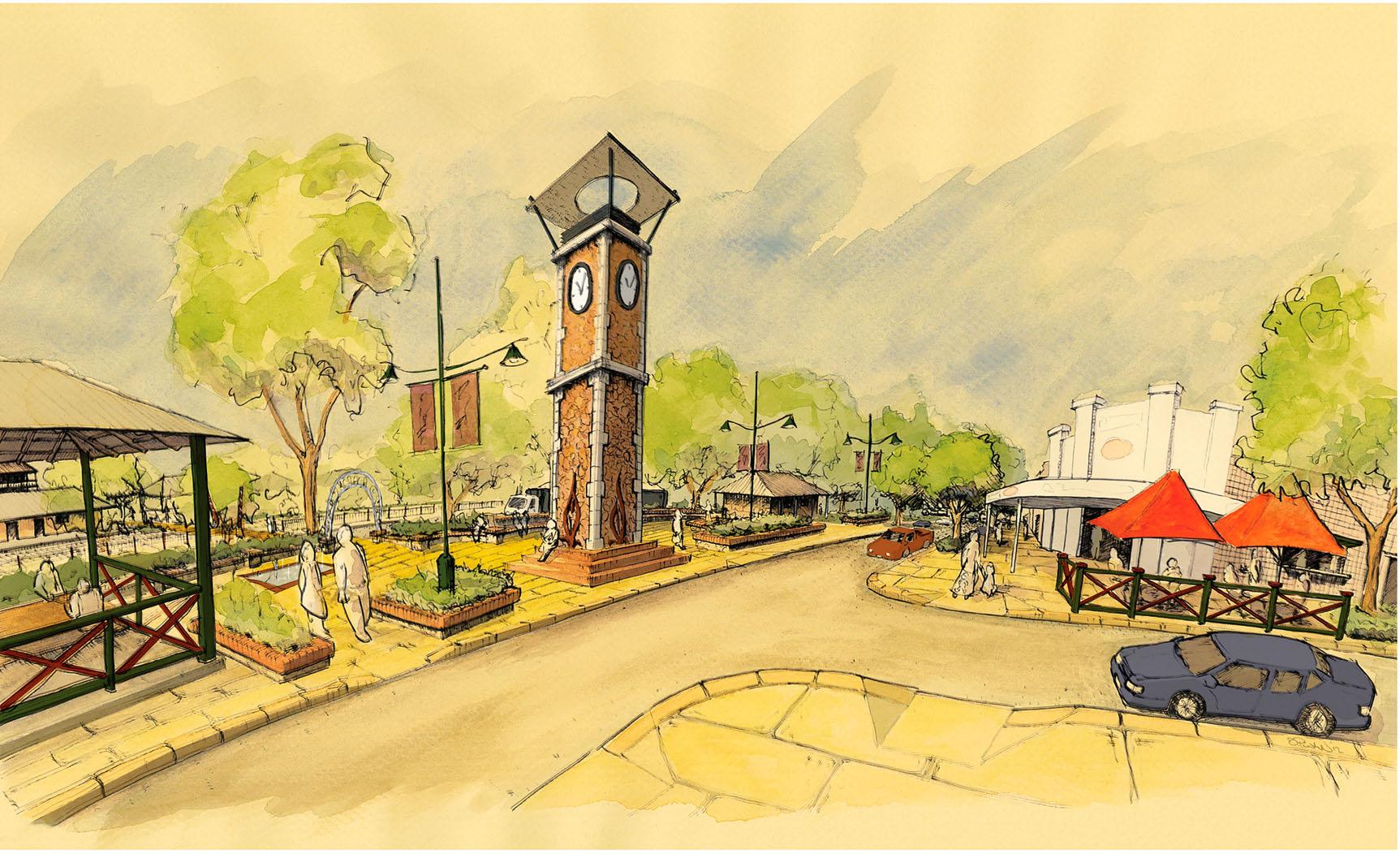

Figure15. AphotoofMorawacivicplaza.

Note:Civicplazasarepresumedtofunctiontoreinforceasenseofbelonging.WithinthecontextoftheexpanseoftheWheatbeltravagedbyvastforest clearing,salinisation,soilerosion,pestsanddroughtstheplaza,drawingonthesymbolismofthecitysquare,agora,andforum,actsasasiteofcivicbelonging(imagecourtesyofThePlanningGroup/ShireofMorawa).

Note:AviewoftheMorawacivicplazalookingbacktowardsthemainstreet.Suchplazas,withtheirattendantlocalartisanfeaturesattempttocatalyse elusivecreativityandeconomicdiversification,aswellasreinforceasenseofbelonging(imagecourtesyofEmergeEnvironmental).

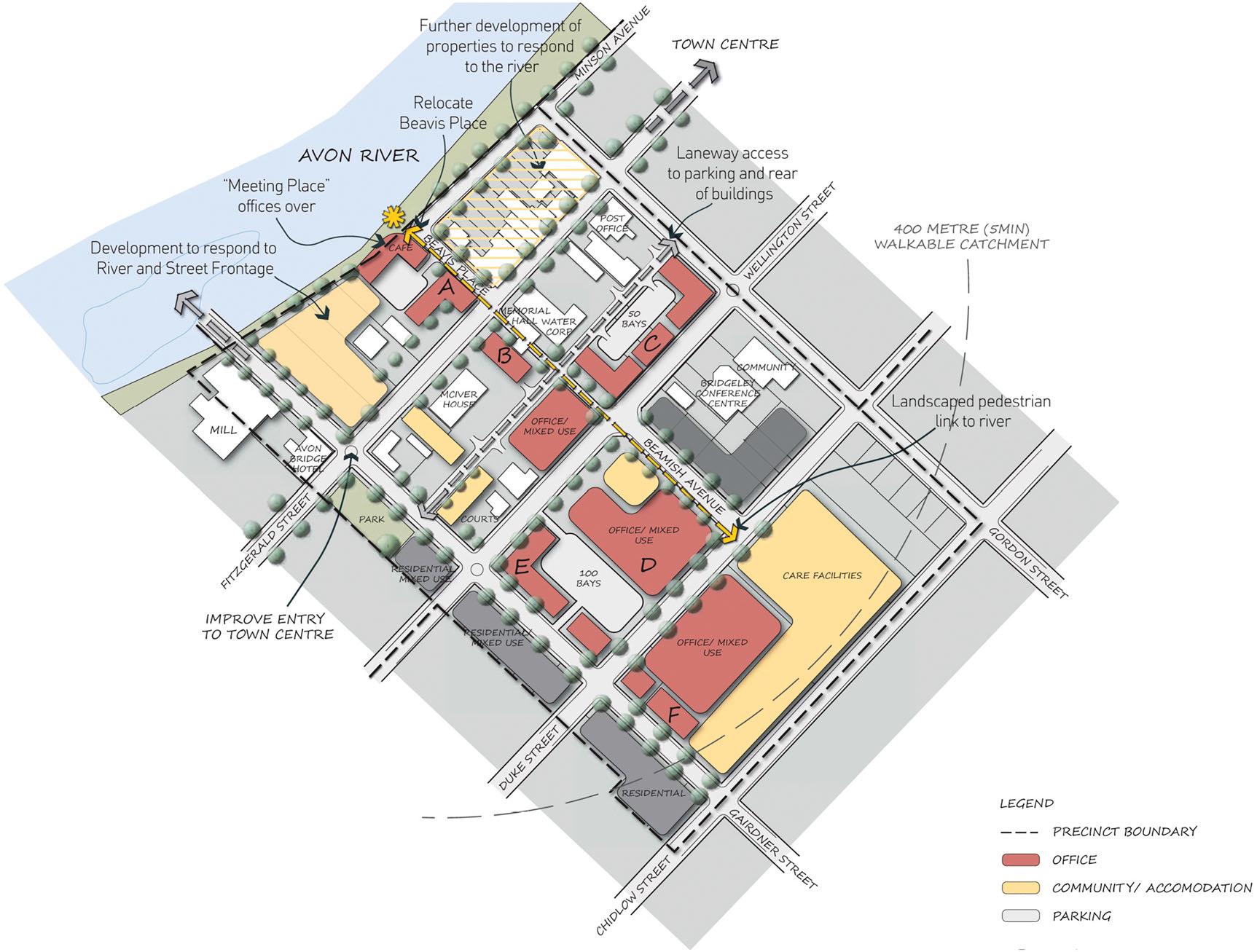

Tothisend,anumberoftheSuperTownGrowth Plansfocusonforgingstrongerconnectionsbetween existingtownsitesandadjacentrivers,inparticular theHothamRiverinBoddingtonandtheAvonRiver inNortham(HamesSharley 2012,74),aswellas improvingtheenvironmentalhealthoftherivers (Figures17 and 18).IntheNorthamSuperTown GrowthPlan,landownersanddeveloperswere encouragedto ‘turnaround’ tofacetheriverprecinct (ShireofNortham 2011,60).Concomitantly,the localgovernmentdeliveredriverhealthprogramsand upgradedforeshorepublicopenspacesothatthe ‘riverwouldbecomeamajorfocalpointforthesub region’ (ShireofNortham 2011,60).

IntheKatanningSuperTownGrowthPlan,aGreen InfrastructureConnectivityConceptcalledforthe rehabilitationofcreekswithinthetownsite – which wereheavilyinfestedwithweedsandmarredbybank stabilisationmeasures – aswelltheintroductionofformalisedpedestriantrailsalongthesecorridors(Shireof Katanning 2012,23).Localgovernmentbelievedthe resultofsuchinterventionswouldberecreational benefitsand ‘visualappeal’ thatwouldhelptodevelop Katanning’ s ‘uniquesenseofplace’ (ShireofKatanning 2012,39).Remnantvegetation,whichtendstodisproportionatelyconcentratewithinthetownsitesas opposedtothesurroundingclearedagriculturalland, wasalsoslatedforprotectionfromBusinessAsUsual (BAU)suburbansprawl(ShireofKatanning 2012,49).

Discussion. ImprovingenvironmentalhealthandconnectingtoenvironmentalassetsinSuperTownplanningcanbeunderstoodbothasagesturetoreverse (toasmallextent)theecologicaldevastationwhich theWheatbeltembodiesbutalsoasameansof attemptingtoreversesettlementdecline(Newman 2005,530) – andtoincreasetheappealoftheSuperTownstopotentialurbanmigrants.InSuperTown planning,policymakershopedthatenvironmental initiativeswouldhelptoamelioratetheurbandweller’ s connotationsbetweentheWheatbeltandenvironmentaldevastationthattendstocurtailtheattractivenessofWheatbelttowns.Rathertheserejuvenated environmentalassets,throughtourism,andpotentially migration,are(inpart)perceivedtoformapotential economicmainstay(Kullmann 2013,249).

AfocusonenvironmentalhealthinSuperTownplanningalsorepresentsanattempttobalancetheurban drawcardsofsuchplanning(includingmainstreet upgradesandurbanplazas)withthe ‘natural’ attractions ofruraltowns.Thisisbynomeansanewstrategy, employingaccesstonature,asanincentiveforpopulationdecentralisationhasalonghistory.Indeed,EbenezerHoward’snowhistoricGardenCitiesmodelaimedto combinethebestoftownandcountryinanewkindof settlement,TownCountry(Hall 2002,93).WhatismissinginthecaseoftheSuperTownsisaregionalplanfor theWheatbeltwhichisbasedontheprinciplesofecologicalbalanceandresourcerenewal(Hall 2002,8)

Figure17. Katanningcreekrehabiliation.

Note:IntheKatanningSuperTownGrowthandImplementationPlanaGreenInfrastructureConnectivityConceptcalledfortherehabilitationofcreekswithin thetownsitewhichareheavilyinfestedwithweedsandmarredbybankstabilisationmeasures,aswellformalisedpedestriantrailsalongthesecorridor (imagecourtesyofEcoscape).

Figure18. NorthamtownsiteandproposedconnectionstotheAvonRiver.

Note:IntheNorthamRegionalCentreGrowthPlanlandownersanddeveloperswereencouragedto ‘turnaround’ tofacetheriverprecinct(imagecourtesy ofHamesSharley).

withinwhichtheSuperTownscouldbenestled.While importantatalocalscale,thesmalleffortsmadetowards ecologicalrestorationandremnantvegetationprotection madeinSuperTownplanningwereunlikelytorecastthe Wheatbelt’sgeneralimageproblemaroundenvironmentalissues – andassuchdolittletoenticeurban dwellerstotheinlandSuperTowns.

Parttwo:evaluatingtheSuperTownpolicy, anditsspatialdesignstrategies,fromthe perspectiveofinlandpopulation decentralisation

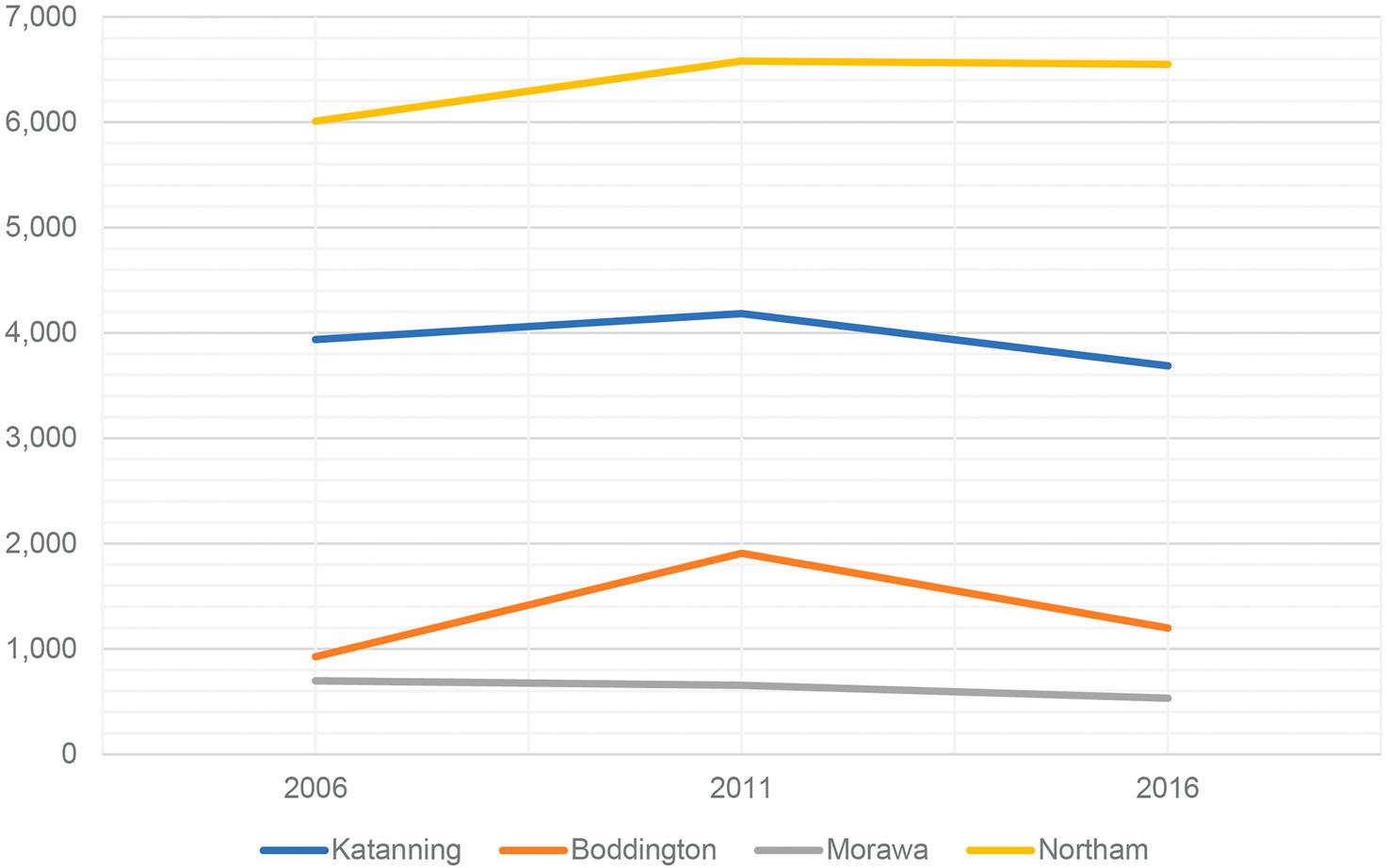

Thissectionexaminesrecentlyreleaseddemographic datatoallowustoformaprovisionalpictureofthe success,orotherwise,oftheSuperTown’spolicyin enablingpopulationdecentralisationawayfrom majorurbancentres.Itisimportanttonoteatthis pointthatthatthesuccessofSuperTownstrategies canbeevaluatedusingcriteriaotherthanpopulation statistics(Kullmann 2013,248),suchasincreased civicpride,orretentionoffamiliesoverlongertime periods.Thesecriteriaarehowevernotpartofthe scopeofthispaper.Concerningpopulationdecentralisation,thepictureismixedatbest.OftheSuperTowns studiedinthispaperallofthepopulationsfell,tovaryingdegrees,whenconsideredattheStateSuburbLevel, themostdetaileddatatheAustralianBureauofStatisticsprovides(AustralianBureauofStatistics 2016) (Figure19).Indetail,Morowa’spopulationfellfrom 655in2011–532in2016(minus123),Northam’ s populationfellfrom6,580–6,548(minus32),Boddington’sfrom1,908–1,198(minus710)andKatanning’ s populationfellfrom4,183–3,687(minus496).In total,thecasestudySuperTown’slost1,361peoplein

the2011–2016period,despitethesubstantial$85 millioninvestmentmadethroughtheSuperTowns program(AustralianBureauofStatistics 2016).As such,readerscouldexpectthissituationhasledtopoliticalcommentaryfromthereasonablyfreshlyelected LaborStateGovernment.NewRegionalDevelopment MinisterAlannahMacTiernanrecentlysaidtherewas littleevidencetheSuperTownsschemehadachieved itsgoalofattractingpeopleawayfromPerth:

Whenwelookattheamountofmoneythathasbeen invested,andwelookatthepopulationchanges,we can ’tbereallyconfidentthatthismoneyhasnecessarilyproducedtheresult thebeautificationof towncentreshadfailedtoimproveemployment opportunitieswhichiswhatwillbringpeopleto thosecountrycentres(Walkeretal. 2017).

Asaresult,thenewStateGovernmenthas flagged axingtheSuperTownsscheme(Walkeretal. 2017). Regardlessofthepoliticalcommentary,whatisevident isthatspatialdesigngestures,appliedinrelativeisolation,havenotyieldedsignificantpopulationdecentralisationtoinlandruraltowns.Strangely,someof theactualSuperTownGrowthPlans,whichsawsignificantspendingonspatialdesigninterventionspredicted thisatthetime – as,didtheShireofMorawa: Morawa’sregionallocationmayotherwiseprovetobe adisincentiveforalargenumberofpeopletotakeup residencythereunlessthereisaverygoodreasonfor themtodoso.Thereasonisusuallyemployment related(ShireofMorawa 2012,60).

InterestinglytheShireofMorawaidentifiedthemain streetupgradeasbeingtheirfourthpriorityforState Governmentfunding.Astheyrecentlyexplained: ‘ we asashirechoseindustry.However,thedecisionwas notoursastowherethemoneywouldbespent …’

Figure19. WheatbeltSuperTownpopulationgrowthbetween2006and2016.WhilealltheSuperTownsstudiedlostpopulation thedegreevaried.BoddingtonandKatanninglostthemostpopulationwhileNorthameffectively flat-lined.Datacourtesyofthe AustralianBureauofStatistics.TheSuperTownspolicywaslaunchedin2011.

indicatingsuchdecisionsmayhavebeenenactedona higher,probablypolitical,level(Walkeretal. 2017).

Thissituationrevealstherelativeinabilityofspatial designalonetodealwithbroaderproblemsfacinginland ruraltowns.Thisisprincipallybecausetheproblems facingthesetowns,e.g.,farmamalgamationandexpansionorthesubstitutionofcapitalforlabour(Plummer, Tonts,andArgent 2017,1) – arenotattheircorespatial designissues.Eventherelatedenvironmentalissues facingtheWheatbelt,suchassalinisation,soilerosion, introducedspeciesandwatershortages(Diamond 2011,379)arenotwithintheremitofspatialurban design.Giventhissituation,theovertfocusonfunding spatialdesigninterventionswithintownswouldappear tonothavebeenwelltargeted.

Planningforthedecentralisationofpopulationtothe inlandSuperTownshasbeenprincipallyaboutdeliveringspatialoutcomesbywhichtownscouldaccommodatepopulationincreasesbutalsoshapinganimageof aconfident,creative,engagedanddiverseruralsociety – todrawpeoplefromlargerurbancentres.Ofcourse, theactualcultivationofanexpandedruralsocietyis lesspredictablethanplanningforitshardinfrastructure. AsMarcusWestburyexplains, ‘therearefewroadmaps toapplytothechallengingtaskoffosteringadynamic successfulculture.Itismuchmorethanplacementof monuments,buildingsortransportlink’ s (Westbury 2008,173).Inthecreationofsuchaculture,spatial designremainsa ‘bluntinstrument’ thatisatbesta devicewhichcanspatiallyenablesuchasocietyover timeandprovideimageswhichevokeit.

Alternativestrategiestopartiallymitigatethe barrierstoinlanddecentralisation

Iftheyhadreviewedtheliterature,concerningprevious attemptsatdecentralisationinAustralia,policymakers mighthavebeenabletopredictthefailureoftheSuperTownsprogramtoyieldsubstantialdecentralisation. FirstandforemostwhilethecapitalcityofPerth remainshighlyliveable(TheEconomist 2016)there islittleinthewayofan ‘urbancrisis’ topromptresidentsandbusinessestore-evaluatetheircurrent location(Lonsdale 1972,326).Inshort,whilethelarger urbancentresremainliveablethereisno ‘push’ factor todrivepopulationdecentralisationtoinlandregions. Inthisrespect,stategovernmentcouldconsiderimplementingstrongerurbancontainmentpoliciesinmajor urbancentres(Bolleter 2015).Amongthemostpopularareurbangrowthboundariesandgreenbelts,which aimtolimiturbandevelopmentbeyondboundaries andwithingreenbelts(OECD 2012,16).Suchpolicies, intime,mightbeabletoredirecttheforcesofgreenfieldsuburbanexpansionintoregionaldecentralisation.

Moreover,itwouldappeartobeafutiledecentralisationstrategytoattempttoduplicatetheurbanamenityoflargerurbancentresinabidtodrawpeople fromthesesamecentres.Thisisbecauseasmallrural SuperTownwillbeunlikelytobeabletomatchthe urbanamenitythatrequiresalargerpopulationbase tobeauthentic.Inthisrespect,SuperTownplanning mayhavehadgreatersuccessinpromotingdecentralisationbycateringforalternativelifestylesthatlarger urbancentresdonotprovide.PeterNewmanhasraised thepotentialofruralEco-Villagesinthisrespect –communitieswhichwouldbeoff-gridandallowfor socialexperimentation(Newman 2005,531).Nonetheless,thesecommunitieswillneedtoworkhardtoovercomethepreferenceofAustraliansforclimatically favourablelocationsonthecoast.

EconomicfactorscontinuetoworkagainstpopulationdecentralisationasAustralia’seconomyis becoming evermoreconcentrated.Evidenceofthisis that80%ofeconomicactivitytakesplaceonjust0.2 percentofAustralia’slandmassincapitalcities –andtheyremainthebackboneofoureconomy(Kelly andDonegan 2015,23).Evenwithinthesecities,economicactivityisheavilyconcentrated,assuchcentral businessdistrictsalonearecriticallyimportanttothe nation’sprosperity(KellyandDonegan 2015,23).In thissituation,decentralisingeconomicactivityto metropolitanActivityCentresinsuburbanlocations ischallengingenough,letalonetoruralinlandcentres. Thisisparticularlythecasewhengovernmentsarecarryingoutthedecentralisationofeconomicactivity throughthelensofspatialdesign,notjobcreation strategies.

Inthisregard,theWesternAustralianstategovernmentcoulddirecttheirinvestmenttowardstransport improvementsbetweenPerthandselectSuperTowns, sothatregionalresidentscanaccessthehighpaying jobsofPerth.Inrecentyears,advocatesofhigh-speed rail – whichcantravelat350km/h – havemadesimilar assertionsforboththewestandeastcoasts(Bolleter andWeller 2013).Howeverforhighspeedrailtobe feasible,itnormallyneedstoconnectcitiesofwell over1,000,000peoplethatareseparatedbytravel timesoflessthan3h9 (DepartmentofInfrastructure 2010,1),asituationunlikelytoariseinWesternAustraliaanytimesoon.However,strengtheningand improvingregionalrailservicesfromPerthtothecloserinlandSuperTownssuchasNorthamandBoddingtonissensible.Indeed,withsuchaservicethetrain journeyfromPerthtoNortham(97km)shouldbe 40minandPerthtoBoddingtonunderonehour (127km).AsFionaMcKenzieexplainsrailhashada renaissance,inruralareasaroundAustralia ‘The restoredrailnetworkhasreconnectedtownsacross thecountry.Automationhasenabledpassengerand commercialservicesthatarereliable,affordableand inhighdemand’ (McKenzie 2016,18).Inthisrespect,

itisstrangethatin2013(withtheSuperTownspolicy infull-swing)thePublicTransportAuthority(PTA) announcedthecancellationoftheAvonLinkservice (whichconnectsPerthtoNortham)10 anditsreplacementbyabusservice(Ducey 2013) – amovewhich nodoubtreflectsalackofsharedpolicyobjectives betweenthePTAandDepartmentofRegional Development.

Thispaperhasreviewedtheuseofspatialdesignin inlandSuperTownsinabidtoovercomepsychological barrierspotentiallycurtailingthemigrationofresidentsoflargerurbancentrestotheregions.The paperconcludes,onthebasisofpopulationdata,that whilesuchspatialdesigngesturesmayyieldbenefits tothelocalcommunityintermsofincreasedcivic pride,theyareunlikely(inisolation)toyieldsubstantialpopulationdecentralisationtoinlandregions. Thisisparticularlywhendeployedinrelativeisolation fromregionalpublictransportationstrategies,regional environmentalplansandpoliciesforcurtailingand redirectingurbangrowthinmajorcentres.Inshort, theissuesfacingtheWheatbeltsuchaschronicstructuraldeclinearenotspatialinnature.Inthiscontext, spatialdesignersarereducedtocreatingthe ‘containers ’ for,andimagesof,vibrancy,creativityandgrowth butareunabletodelivertheeconomicconditionsthat couldsignificantlygrowruralsociety.

Notes

1.Moreover,intheU.S,decentralisationproponents believedsiphoningpeoplefromthemajorcitiesinto neworboostedcitiesinregionalareaswastheanswer totheurbancrisisofthe ‘bigcities’,initsvarious manifestations(1967,711).

2.Whilethisfundingwasmuchoverdue,thepolicyhas politicalorigins.Thesubstantialnewfundingwasthe non-negotiabledemandwonbythethenNational partyleader(andstateRegionalDevelopmentminister)BrendonGryllsasaconditionofhisparty’ ssupportfortheLiberalpartyinthestate’shung parliament(AustralianAssociatedPress 2008).The politicaloriginsofsuchapolicyisnothingnew – politicians ‘wooing’ countryelectoratesoftenreaffirm theirsupporttotheprincipleofdispersionoffunding, economicopportunityandpopulationtoruralareas (Lonsdale 1971,116).

3.TheelevenRegionalCentres,identifiedinthe RegionalCentresDevelopmentPlan(WesternAustralianPlanningCommission 2012,14),whichareprojectedtoabsorbmuchofthispopulationgrowthare Albany,Broome,Bunbury,Busselton,Carnarvon, Geraldton,Kalgoorlie,Karratha,Kununurra,MandurahandPortHedland(DepartmentofRegional Development 2016b,31).Theseareexistingsubstantialregionalcentres,which,exceptforKalgoorlie,are onornearthecoast.

4.Inadditiontoenticingpeopleawayfromlargerurban centres,theSuperTownsplanaimedtobuildonthe attributes,resources,capabilitiesandpotentialsof existingregionalcommunities(Departmentof RegionalDevelopment 2011,13)aswellasincubate theirownnaturalpopulationincrease(Department ofRegionalDevelopment 2011,4)

5.ThepriorityprojectsacrossthenineSuperTownswere: Boddington – RanfordWaterCapacity($1.25million), andEconomicDevelopmentImplementationinthe BoddingtonDistrict($1.17million),Collie – Collie CBDRevitalisation($12.40million),Esperance –EsperanceWaterfrontProject($19.7million)EsperanceTownCentreRevitalisationMasterplan($.380 million)EsperanceEconomicDevelopment($.193 million),JurienBay – JurienBayCityCentreEnhancementProject($12.42million),Katanning – ($9.31 million)MulticulturalandAboriginalEngagement andEnhancement($.255million),Manjimup – Manjimup’sAgriculturalExpansion($6.95million)revitalisationofManjimup’sTownCentre($5.71million), MargaretRiver – MargaretRiverPerimeterRoadand TownCentreImprovements($1.94million)Surfers PointPrecinct($4.70million),Morawa– NorthMidlandsSolarThermalPowerStationFeasibilityStudy ($.500million)MorawaTownSiteRevitalisation ($3.00million),Northam – AvonRiverRevitalisation andRiverfrontDevelopment($3.65million)Avon HealthandEmergencyServicesPrecinct-$4.81million (DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment 2017).

6.Inthispaper,ItypicallyrefertothepractitionersdeliveringtheSuperTownGrowthPlansasspatial designersorplanners.Iintendthistobeinclusiveof urbanplanners,urbandesigners,landscapearchitects andarchitects.TownPlanningManagementEngineering/EcoscapeproducedtheGrowthPlanforKatanning,HamesSharleyforBoddington,ThePlanning GroupandEmergeEnvironmentalforMorowa,and HamesSharleyandRPSEnvironmentforNortham.

7.Largerurbancentreswillbesubsequentlyusedinthis papertorefertothecapitalcityandRegionalCentres asdefinedbytheDepartmentofRegionalDevelopment(2016b,31).

8.Thereareexceptions,however.Severalruraltownsin easternAustraliahavesuccessfullyenactedlocally adaptedmainstreetupgrades.Atopicalexampleis theruraltownofCoolahinthestateofNewSouth Walesthatsuffereddeclinefollowingruralrecession and theclosureofthelocalmillinthe1980s(Kullmann 2013,248).

9.Ihavebasedthiscalculationonanaveragespeedof 150kmh.ThisissubstantiallylessthantheKalgoorliePerth ‘Prospector’ whichhasamaximumservicespeed of200kmh(DepartmentofInfrastructure 2010,12).

10.Duetoapublicoutcrythiscancellationnever occurred.

Disclosurestatement

Nopotentialconflictofinterestwasreportedbytheauthor.

References

AlanBurns,Edgar,andEvanWillis. 2011 “EmptyShopsin AustralianRegionalTownsasanIndexofRural Wellbeing.” RuralSociety 21(1):21–31.

AustralianAssociatedPress. 2008 “WA:AndrewForrest BacksBarnett’sDubaiPlan.” AustralianAssociated Press.Accessed20October. http://search.proquest.com/ docview/448194740?accountid=14681 .

AustralianAssociatedPress. 2011. “WA:NatsFlag PopulationPolicytoEaseStrain.” AustralianAssociated PressGeneralNewsWire.Accessed15June. https:// search.proquest.com/docview/850537590?accountid= 14681

AustralianBureauofStatistics. 2016 “Census.” Australian Government.Accessed10November. http://www.abs. gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/Census? OpenDocument&ref=topBar

Bennett,Mark. 2014 “KatanningMainStreetRefurbishment DelaysFrustrateLocalBusinessOwners.” ABCNews Accessed3July. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-0727/katanning-street-upgrade-delays-anger-shop-owners/ 5617906.

Berkley,GeorgeE. 1973. “Britain’sNewTownBlues.” NationalCivicReview 62(9):479–485.

Bolleter,J. 2015 ScavengingtheSuburbs:AuditingPerthfor1 MillionInfillDwellings,10.Perth:UniversityofWestern AustraliaPublishing.

Bolleter,J. 2018 TheghostcitiesofAustralia:ASurveyof NewCityProposalsandTheirLessonsforAustralia’ s 21stCenturyDevelopment,9.London:Springer.

Bolleter,J.,andR.Weller. 2013 MadeinAustralia:The FutureofAustralianCities,203.Perth:Universityof WesternAustraliaPublishing.

Chapman,Rachel,MatthewTonts,andPaulPlummer. 2014 “ResourceDevelopment,LocalAdjustment,andRegional Policy:ResolvingtheProblemofRapidGrowthinthe Pilbara,WesternAustralia. ” JournalofRuraland CommunityDevelopment 9(1):72–86.

Dale,Allan,AndrewCampbell,MichaelDouglas,Alistair Robertson,andRuthWallace. 2014 “From Mythto Reality:NewPathwaysforNorthernDevelopment.” In NorthernDevelopment:CreatingtheFutureAustralia,editedbyAntonRoux,MattFaubell,andDuncan McGauchie,7–17.Melbourne:ADCForum.

Davison,Graeme. 2016a CityDreamers:TheUrban ImaginationinAustralia.Sydney:NewSouthPublishing. Davison,Graeme. 2016b “CityDreaming:MakingPeace withBelonging.” GriffithReview 52:202. DepartmentofInfrastructure,Transport,RegionaldevelopmentandLocalGovernment. 2010 AProfileofHighSpeedRailways.Canberra:DepartmentofInfrastructure, Transport,RegionaldevelopmentandLocalGovernment. DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment. 2011. Regional CentresDevelopmentPlan(SuperTowns)Framework 2011–2012.Perth:GovernmentofWesternAustralia. DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment. 2016a Regional CentresDevelopmentPlanFramework.Perth: GovernmentofWesternAustralia. DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment. 2016b Royaltiesfor Regions:ProgressReportJuly2015–June2016.Perth: GovernmentofWesternAustralia. DepartmentofRegionalDevelopment. 2017 “SuperTowns. ” GovernmentofWesternAustralia.Accessed15June. http://www.drd.wa.gov.au/projects/EconomicDevelopment/Pages/SuperTowns.aspx Diamond,Jared. 2011. Collapse:HowSocietiesChoosetoFail orSurvive.London:PenguinBooks. Dovey,Kim,andLeonieSandercock. 2005. “Riverscapes1Overview.” In FluidCity:TransformingMelbourne’ s UrbanWaterfront,30–42.London:Routledge.

Ducey,Liam. 2013. “TranswaCancelsAvonLinkTrain Service.” Watoday.Accessed8July. https://www.watoday. com.au/national/western-australia/transwa-cancels. Farr,Douglas. 2008. SustainableUrbanism:UrbanDesign withNature.NewJersey:JonWileyandSons. Florida,Richard. 2002 RiseoftheCreativeClass.NewYork: BasicBooks. Freestone,Robert. 2013 “BacktotheFuture.” In Madein Australia:TheFutureofAustralianCities,editedby JulianBolleterandRichardWeller,236–243.Perth: UniversityofWesternAustraliaPress. Frost,Warwick. 2004 “AustraliaUnlimited?Environmental DebateintheAgeofCatastrophe,1910–1939.” EnvironmentandHistory 10,285–303. Hall,Peter. 2002 CitiesofTomorrow;AnIntellectualHistory ofUrbanPlanningandDesigninthe20thCentury.3rded. Oxford:BlackwellPublishing. HamesSharley. 2012. BoddingtonSuperTown.Perth:Shireof Boddington,DepartmentofRegionalDevelopmentand Lands,PeelDevelopmentCommission. Hugo,Graeme. 2012 “PopulationDistribution,Migration andClimateChangeinAustralia:anExploration.” Urban Management,TransportandSocialInclusion ,1–101.

Kelly,Jane-Frances,andPaulDonegan. 2015 CityLimits: whyAustralianCitiesareBrokenandHowWeCanFix Them.Melbourne:MelbourneUniversityPress.

Kilmartin,LeslieA. 1973 “UrbanPolicyinAustralia.The CaseofDecentralisation.” TheAustralianandNew ZealandJournalofSociology 9(2):36–39.

Kullmann,Karl. 2013 “DesignforDeclineLandscape ArchitectureStrategiesfortheWesternAustralian Wheatbelt.” LandscapeJournal 32(2):243–260.

Lang,John. 2016. RevisitingPlaceandPlacelessness , edited byEdgarLiuandRobertFreestone,37–48. Routledge.

Lonsdale,Richard. 1971. “Decentralization:theAmerican ExperienceanditsRelevanceforAustralia.” The AustralianJournalofSocialIssues 6(2):116–127.

Lonsdale,Richard. 1972 “ManufacturingDecentralization: theDiscouragingRecordinAustralia.” LandEconomics 48(4):321–328.

Malan,Liesl,andSallyWright. 2015 “ADangerous Profession.” LandscapeArchitectureAustralia,61–64. McKenzie,Fiona. 2016 ScenariosForLandTransportIn 2040.Melbourne:LaTrobeUniversity. Mills,Michael. 2010 “RegionalRevitalisationforPilbara MiningTowns.” ReedBusinessInformation.Accessed20 October. http://search.proquest.com/docview/928948186? accountid=14681.

Mirams,Sarah. 2012. “‘TheAttractionsofAustralia’:EJ BradyandtheMakingofAustraliaUnlimited.” AustralianHistoricalStudies 43(2):270–286. Newman,Peter. 2005 “TheCityandtheBush Partnershipsto ReversethePopulationDeclineinAustralia’sWheatbelt.” CropandPastureScience 56(6):527–535. OECD. 2012 “CompactCityPolicies:AComparative Assessment.” OECDGreenGrowthStudies. Plummer,Paul,MatthewTonts,andNeilArgent. 2017 “SustainableRuralEconomies,EvolutionaryDynamics andRegionalPolicy.” AppliedGeography Potts, Anthony. 2003 “ThePoweroftheCityinDefiningthe NationalandRegionalinEducation.ReactionsAgainst theUrban:UniversitiesinRegionalAustralia.” PaedagogicaHistorica 39(1):135–152. ShireofKatanning. 2012. KatanningSuperTown:Growth andImplementationPlan.Perth:ShireofKatanning,

DepartmentofRegionalDevelopmentandLands, LandCorp,GreatSouthernDevelopmentCommission.

ShireofMorawa. 2012.MorawaSuperTown:Growthand ImplementationPlan.ShireofMorawa,MidWest DevelopmentCommission,Landcorp,Departmentof RegionalDevelopmentandLands.

ShireofNortham. 2011 NorthamRegionalCentreGrowth Plan.Perth:ShireofNortham,DepartmentofRegional DevelopmentandLands,WheatbeltDevelopment Commission.

Spilhaus,Athelstan. 1967 “TheExperimentalCity.” Science 159:710–715.

Swaffield,Simon,andElenDeming. 2010 Landscape ArchitectureResearch.NewJersey:Wiley.

Swaffield,Simon,andElenDeming. 2011 “Research StrategiesinLandscapeArchitecture:Mappingthe

Terrain.” JournalofLandscapeArchitectureSpring 2011: 34–45.

TheEconomist. 2016. “TheWorld’sMostLiveableCities.” TheEconomist.Accessed4July. https://www.economist. com/blogs/graphicdetail/2016/08/daily-chart-14 Walker,Alice,AndrewCollins,GeorgiaLoney,andNatasha Harradine. 2017 “SuperTownsProjectFacesAxeDueto PoorPopulationGrowthinRegionalWesternAustralia.” ABCNews.Accessed15June. http://www.abc.net.au/news/ 2017-04-12/supertowns-program-faces-axe-wa/8438600 Westbury,Marcus. 2008 “FluidCitiesCreate.” In Griffith Review:CitiesontheEdge,editedbyJulianneSchultz, 171–183.Brisbane:GriffithUniversity. WesternAustralianPlanningCommission. 2012 State PlanningStrategy:PlanningforSustainedProsperity Perth:GovernmentofWesternAustralia.