Perth is a city which is expanding into geomorphic wetlands on two major development fronts. While Conservation Category Wetlands and Resource Enhancement Wetlands are being stringently protected development is occurring on land that is in effect waterlogged below the surface and has above surface water at certain times of the year. One result of this is that many new greenfield developments to adopt Living Stream orientated Public Open Space systems to cope with the related drainage requirements. With respect to this context this report scopes the twin research questions, to what degree can Perth Living Stream reserves be considered Public Open Space, and how can Living Streams be optimised, from an urban design perspective, to provide greater amenity?’ These questions are explored in relation to a taxonomy of recently constructed greenfield Living Stream projects in Perth. The report concludes that Living Streams have significant value and that a number of urban design strategies could be deployed in relation to urban density and structure, which arguably could provide greater access to the amenity Living Streams provide in Perth.

Living streams, for living suburbs

To what degree does Living Stream POS being delivered in new suburban developments in Perth provide amenity?

0 11, 000 22, 000 5, 500 Meters e w etla nd s Prop ose d urba n are as in geo we tla nd s Existing sub urba n are a s M ni ca se stud y proje c t © Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2016

Contents 6 Preface 12 Background 22 An assessment of Living Streams 38 Urban design strategies 60 Conclusion 66 References 70 Contributors

5

Preface

To what degree does Living Stream and Park Avenue POS being delivered in new suburban developments in Perth provide amenity, and as such be considered as ‘proper’ public open space?

6

Preface

The Western Australian capital city, Perth, is expanding into geomorphic wetlands along its south-eastern and north-eastern development fronts. As a result of this situation suburban projects are being designed and delivered to deal with high groundwater constraints. This is typically expressed through the importation of large amounts of fill to lift urban form above water levels, and through Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) informed Living Stream Public Open Space (POS) models which allow for the drainage of broad suburban areas.

Method

Given development is moving into those more challenging areas, and the fact that Living Stream models are relatively new in Perth, this report examines, in part 1, the POS function of a series of Living Stream case study projects and asks how the amenity1 offered by these projects could be maximised, in part 2. The questions structuring this research are as follows:

To what degree does Living Stream POS being delivered in new suburban developments in Perth provide amenity, and as such be considered as ‘proper’ public open space?

How can Living Streams be optimised, from an urban design perspective, to provide amenity to surrounding communities?

To answer the former question an 1 Amenity in this report referring to the provision of ‘comfort, convenience or pleasure’ (Ask. com, 2008)

‘evaluative’ research methodology (Swaffield & Deming, 2011, p. 39) is employed to evaluate a taxonomy of Perth Living Stream case study projects against a credible Perth based matrix for assessing public open space attractiveness (Sugiyama, Francis, Middleton, Owen, & Giles-Corti, 2010, p. 1753). This is augmented by a Perth focussed analysis of the effects of Living Streams on the real estate values of adjacent properties, and an analysis of wetland visitation data.

To respond to the latter question a ‘design projection’ method is employed in which various urban design strategies are systematically proposed (Swaffield & Deming, 2011, p. 40). While there is some controversy as to whether a design projection method can be considered legitimate research, Swaffield and Deming argue that if it is conducted systematically, with a clear framework and research questions that it indeed does constitute research (Swaffield & Deming, 2010, p. 206).

In this report the design projection work is carried out with reference to a clear research question (as set out above) and in relation to a comprehensive literature review, review of constructed case study projects and knowledge garnered from a range of interviews with sustainability engineers (Grace, 2016), urban designers (Wood-Gush, 2016), landscape architects (Emerge Associates, 2016)and hydrologists (Brookes, 2016) all who have delivered Living Stream related projects, state government representatives who regulate the design and operation of Living Streams (Brown, 2016),

7

redevelopment authority directors who have been responsible for the delivery of Living Stream structured suburban developments (Ellis, 2016), project directors responsible for facilitating the design of WSUD developments (Taylor, 2016), and academics who have conducted research into water and psychological economics (Geoff Syme, 2016). Through this rigorous process it is intended that the research will produce new constructive and generalizable knowledge (Swaffield & Deming, 2010, p. 206), within the Perth context – if not more broadly.

Definition of terms

8

Living Streams are invariably mapped historical ephemeral streams. In some case Living Streams are added to the planning framework to deal with areas where post development water flows would bring them close to ephemeral stream status. They are usually an average of 60 metres wide.

Park Avenues are linear parks added to the planning framework usually to provide for water treatment to strip silt and other pollutants and decrease the rate of water flows entering Living Stream in larger rain events. Park Avenues are not always needed for water flows and may be part of the planning to provide safe, direct and attractive parkways for pedestrian, cycle and flora movement. Even where they are needed for water flow some sections may be piped. They are usually an average of 20 metres wide. Where Living Streams are referred to in this study the term applies to Living Stream and Park Avenues. In this report much of the assessment can be expanded

across all types of Living Streams and Park Avenues except where the assessment relates specifically to the water management function.

Road Avenues are within the planning framework as linear treed streets with provided to provide orientation, improved pedestrian and cycle ways and minor treatment. Road Avenues are not specifically included in this study.

UWA illustration of Park Avenue Concept showing active space within a linear corridor with intermittent water treatment function. Park Avenues do not contain permanent living streams and can be narrower.

9

10

Living Streams, which arguably represent one of the most visible WSUD trademarks, are typically retrofitted drains in urbanised or urbanising areas, which aim to deliver the multiple benefits of the water cycle. This is image shows a recently completed Living Stream in the Wungong development, on Perth’s southeastern growth corridor.

11

Background

Living Streams and Park Avenues represent the zenith of WSUD and aim to deliver the multiple benefits of the water cycle...

12

Background

Water Sensitive Urban Design

The Living Stream concept has emerged out of WSUD, a planning, urban design and engineering approach, which involves the ‘integration of urban planning with the management, protection and conservation of the urban water cycle, that ensures that urban water management is sensitive to natural hydrological and ecological processes’ (Polyakov, Fogarty, Zhang, Pandit, & Pannell, 2016, p. 1; T. Wong, 2006, p. 214). WSUD planning, is regarded as being complex, because it aims to ‘protect, maintain and enhance the multiple benefits and services of the total urban water cycle’ (T. H. F. Wong & Brown, 2009, p. 674). These include ‘supply security, public health protection, flood protection, waterway health protection, amenity and recreation, greenhouse neutrality, economic vitality, intra and inter-generational equity; and demonstrable long-term environmental sustainability’ (T. H. F. Wong & Brown, 2009, p. 674), a formidable list of services to conceptualise, and indeed deliver.

Living Streams

Living Streams, which arguably represent one of the most visible WSUD trademarks, are typically retrofitted open trapezoidal drains in urbanised, or urbanising, areas, which aim to deliver the multiple benefits of the water cycle described. In this respect the principal functions of Living Streams are considered to be:

Firstly, to provide flood control and conveyance – in Western Australia Living

Streams networks are required by the state government regulator (Water Corporation) ‘to contain 50% Average Exceedance Probability (AEP) at a 1.5 year Average Recurrence Interval (ARI) flows within a bankfull channel, contain 20% AEP at 5 year ARI flows within the drainage reserve and adjoining POS, and ensure the 1% AEP floodplain is contained within appropriate land uses such as POS, roadways and road reserves, waterways, drainage reserves’ (Water Corporation, 2016, p. 1).

Secondly, and beyond such drainage requirements, Living Streams should function as a biological filter in which fringing and aquatic vegetation provides ‘a biological filter sieving out both organic and inorganic material and assimilating a portion of the nutrients flushed from the catchment’ (Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 197).

Thirdly, Living Streams should function to provide a habitat and food web for a variety of plants and animals and to provide a corridor of land and water along which many animals can move (Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 197).

Fourthly, Living Streams should enhance the amenity of the area – the function that is the explicit focus of this report. Indeed through providing POS, planting vegetation along streamlines or incorporating it into new drains the resulting Living Stream Pen and Majer exhort that Living Streams ‘may become a living feature of the urban or rural environment, rather than just an essential, and often unattractive, part of their infrastructure’ (Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 194).

13

Controversy regarding Living Streams as POS in Perth

Despite the generally regarded function of Living Streams to enhance the amenity of an area there remains some controversy about their role as POS in the Perth greenfield context. In Western Australia, a greenfield development must also allocate 10% of its developable area to POS. This figure derived from the mid twentieth century, a time in which POS was configured with the explicit aim of giving ‘recreational opportunities to the masses’ (Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 6). Indeed it was considered that what ‘was needed most were opportunities for citizens to exercise – to strengthen and discipline bodies, to temper immoral impulses and to give people a place to vent frustrations and escape from urban life’ (Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 6). As a result of an overt focus on active recreation the ‘recreation movement’ saw the simplification of parks to become ‘what we now call playing fields, with little ornamental vegetation, large expenses of grass, places for people to sit, with clubrooms for sporting teams, and facilities like goal posts, basketball hoops and cricket pitches’ (Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 6). In the last decades in Perth however POS has increasingly required to provide for ecological roles – such as stormwater infiltration and retention, providing habitat and maintaining remnant vegetation (Middle & Tye, 2011; Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 7). In part as a result, a tension exists between the various uses, ecological or recreational in Perth (Middle & Tye, 2011).

These tensions have been most clearly

expressed in the Wungong project – an aspirational suburban development on Perth’s south-east fringe. The Wungong project encompasses an area of over 1,400 hectares and it is projected it will yield 16,000 homes at a compact density (by suburban standards) accommodating an anticipated population of 40,000 people (Brett Wood-Gush in Weller, 2009, p. 239). The design philosophy of the Wungong project stems from an initial provocation by the client, the Armadale Redevelopment Authority (ARA), for the designers to produce a ‘concept masterplan as if the landscape really mattered’ (Brett Wood-Gush in Weller, 2009, p. 239).Testament to this landscape orientated philosophy, the initial Wungong masterplan proposed an urban development with an ‘integrated urban water management system structured around an interconnected matrix of Park Avenues and Living Streams to maintain and ‘enhance the area’s natural character’(Brett WoodGush in Weller, 2009, p. 243). The purpose of the Living Streams, and Park Avenues, was not just to take water from one point to another, but rather to be ‘part of the ecology of the site and educate people about the ecosystem’ (Taylor, 2016) as well as being a place for nearby residents to meet and ambulate (Brett Wood-Gush in Weller, 2009, p. 243).2 Reflecting the innovative nature of the proposed Wungong POS system, a system of accrediting POS was developed so that a ‘wider variety 2 Despite the focus applied to creating linear POS in the form of Park Avenues and Living Streams the Wungong project also proposed to provide space for active recreation through the shared use of school ovals and regional sports facilities (Wood‐Gush, 2008, p. 10).

14

of types of open space could be supported as part of the developer contribution to open space’ (Wood‐Gush, 2008, p. 10). In this system Park Avenues and Living Streams are given 50% credit as POS while conventional parks are credited as 100% POS (Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority, 2012, p. 12).

Despite the clarity of this policy, the definition of what constitutes 50% ‘useable space,’ from the perspective of the local government who will eventually will maintain the POS – the City of Armadale – ‘becomes very complex’ (Emerge Associates, 2016). This is in part because in periods of high rainfall areas of the Living Streams become waterlogged, and as such are viewed by some as unusable. Furthermore in 2010 a review of the Wungong project by a peer review panel, commissioned by the then recently elected state government, raised fundamental concerns about the structure of the POS system. In this report it was concluded that there was an ‘inadequate provision and distribution of appropriately useable public open space’ and ‘an over-provision of narrow linear open spaces’ (Jones, Burrell, Morris, Wong, & Stein, 2010, p. 3). Moreover it was considered that the nexus between the Park Avenues and Living Streams and surface water management did not have to be so ‘tightly bound’ (Jones et al., 2010, p. 7).

Such criticisms relate to a 2011 Department of Sport and Recreation commission research report which argued that both WSUD and Bush Forever3 have caused a reduced supply

3 ‘Bush forever’ is a strategic plan for the conservation of remnant endemic bushland in Perth.

of active open space (i.e. sports fields) in the new fringe suburbs studied (Middle & Tye, 2011, p. 4). In part, this has led to an expectation from local governments that the mandated 10% POS figure will be configured in the form of district open space in the form of sporting fields. Indeed several outer suburban Local Government Areas (LGAs) have adopted templates for district open space be given primacy in the design of new POS systems – unless a district plan exists that fully provides for these uses in areas in close proximity to the development. As a result of this, in areas with hydrological and ecological constraints this creates pressure for planners and developers to increase the overall amount of open space provided.

The critiques of the Wungong POS system can’t be mentioned without commenting that at the time the planning profession were increasingly embracing the Liveable Neighbourhoods’ policy which applies to the design of Perth’s new fringe suburbs (West Australian Planning Commission & Department of Planning, 2007), a policy which the Wungong project directly challenged (Wood‐Gush, 2008, p. 10). Indeed many of the Wungong POS types would be excluded from current POS calculations under the Western Australian, Liveable Neighbourhoods policy for being too burdened with use constraints, in relation to drainage (Wood‐Gush, 2008, p. 10).4 There is also arguably an ideological conflict between the Wungong masterplan, which has been

4 It should be noted that current MRA open space policy is now more closely aligned to WAPC policy in terms of excluding drainage from POS.

15

promoted as an exemplar of ‘Landscape Urbanism’ (Weller, 2009) and the Liveable Neighbourhoods policy which is ostensibly New Urbanist. This in turn reflects New urbanism’s ambivalence about linear POS – indeed Andrés Duany has described linear parks as ‘an extended venue for crime’, and as a reoffering of the ‘matrix of green as a buffer’ which in his opinion will ‘perpetuate the problematic dispersive tendencies of the modern city’ (In Kullmann, 2011, p. 72).

While there may indeed by a shortage of sporting fields in Perth5 (Middle & Tye, 2011), the controversy about ‘appropriate’ POS types does raise the question as to what degree Living Streams should be considered as POS which offers amenity to surrounding communities, an indeed how access to this amenity could be maximised.

The significance of this research

This research has significance for the design of many of Perth’s future suburban developments. This is because ‘all the easy land’ on Perth’s fringes has been developed, so there is a lot of low lying land which is now under development focus (Taylor, 2016). Indeed Perth’s new outer suburbs, on the south-east and north-east development front are in many cases being developed on land with is geomorphic (groundwater dependent) wetlands (Singh, Pal, Clohessy, & Wong, 2012, p. 6). Arguably, these new suburban developments will develop their own Living Stream orientated POS systems to manage the seasonal

5 This issue is outside of the scope of this necessarily brief report, but is certainly worthy of further research.

inundation characteristic of these areas.

Furthermore in both Western Australian greenfield and infill contexts Living Streams are topical. Evidence of this is that the Department of Water (the principle manager of water resources) and the Water Corporation (the principle supplier of water) have recently been working collaboratively, through the ‘Drainage for Liveability Program,’ to improve drainage management. This exercise has focussed on ‘reframing drainage’ to ‘meet the needs of the community through understanding current arrangements, examining options to improve drainage management and identifying priority areas for improvement’ (Water Innovation Advisory Group, 2016, p. 20).

Moreover, while there is a substantial body of literature on Living Streams written from an ecological, hydrological, regulatory or economic perspective (Bernhardt & Palmer, 2007; Pen & Majer, 1994; Polyakov et al., 2016) there is lacuna of Perth focussed literature which scopes how urban design can maximise the amenity provided by Living Streams while simultaneously allowing for the important ecological and hydrological functions of Living Streams to flourish.

16

17

Typical geomorphic (groundwater dependent) wetlands in Perth’s south-eastern growth corridor.

18

19

Perth’s new outer suburbs are in many cases being developed in geomorphic wetlands. These new suburban areas will require their own Living Stream POS and drainage systems to manage this challenging hydrological situation.

20

Ge omorp hic an d surfac e w etla nd s

Prop ose d urba n are as in geo we tla nd s

Existing sub urba n are a s

Mini ca se stud y proje c t

Wandi

Piara Waters

0 11, 000 22, 000 5, 500 Meters 21

Byford

Wungong

An assessment of Living Streams

To what degree can Living Stream and Park Avenues be considered as amenable Public Open Space?

22

An assessment of Living Streams as Public Open Space

This following section reviews case study Living Stream projects to determine to what degree they can be considered to constitute amenable POS.6 This review is conducted in relation to a credible POS ‘attractiveness’ matrix developed by the University of Western Australia (UWA) School of Population Health, data around wetland visitation – wetlands having many shared attributes as Living Streams, and house price data for residential properties adjoining drains which have been reconfigured as Living Streams.

Case study projects

The four case study projects that are examined in this section are the linear POS systems which connect to ‘Veterans Park’ in Byford and ‘William Lockard Park’ in Piara Waters, ‘Honeywood Park’ in Wandi, and the linear POS adjacent to Burdekin Turn in Wungong.7 These recent suburban developments, which are all still under construction to varying degrees, are all located in Perth’s south-eastern growth corridor in areas which are identified as geomorphic wetlands. Because of these drainage conditions all of these projects have substantial Living Stream orientated POS systems, developed in part to mitigate flood risks. The case

6 This assessment can be extrapolated to Park Avenues. Living Streams are studied as they provide a more aggregated collection of the opportunities and constraints.

7 These case study projects will be referred to in this report by the name of the suburb as some of the Living Streams don’t appear to have official names.

studies have been, with the exception of Wungong, developed in relation to the Liveable Neighbourhoods policy (West Australian Planning Commission & Department of Planning, 2007) and are characterised by smaller lots sizes of 500 metres squared (and less) and generally single storey suburban form.

The attractiveness of Living Stream POS

Research into POS tells us that users have varying preferences for POS characteristics like ‘undulating topography, water, diverse vegetation and the presence or absence of tree cover’ (Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 22). Just one example of how preferences can differ is, older adults may consider water features in POS as ‘calming and therefore appealing, while mothers of young children may view lakes as safety hazards’ (Francis, Wood, Knuiman, & Giles-Corti, 2012, p. 1574).

Notwithstanding such subjectivity researchers at the School of Population Health at UWA in 2005 developed a method for estimation the ‘attractiveness’ of parks to a set of potential users (Giles-Corti et al., 2005, p. 173). Attractiveness was calculated as a weighted mean score of nine attributes including the presence of walking paths, shade along walking paths, water features, irrigated lawn, lighting, sporting facilities, and birdlife; type of surrounding roads; and being adjacent to a beach or river (Sugiyama et al., 2010, p. 1753). These attributes and their weightings were determined on the recommendations of expert panel members, a focus group, a comprehensive literature review and a

23

second expert panel consisting of urban planners from 13 local government authorities (Giles-Corti et al., 2005, p. 173).

24

Significantly when the four Living Stream case study projects, being examined in this research, were evaluated against these criteria the Living Stream projects scored an average of 70 out of 100. In the original project conducted by the School of Population Health, which evaluated 2,500 parks, recreational grounds, sports fields, commons, esplanades, and buffer strips the average score was 47.5 (Giles-Corti et al., 2005, p. 170). The Living Stream projects tended to rate highly because, other than sporting facilities, lighting and adjacencies to a beach or river, they were generally well-equipped and furnished spaces. Thus the most reliable quantitative measure of POS attractiveness yet developed in Perth indicates that the Living Streams case study projects should be considered attractive POS, at least when ‘attractiveness’ is calculated by this method.

Living Streams and property prices

Confirmation that Living Streams in Perth are regarded as attractive to residents – and presumably offering significant amenity – can be found in the effect of Living Streams on property prices in the adjacent urban area. The Bannister Creek Living Stream, located in the south of Perth’s middle suburbs, provides one example of this. In 2001 Bannister Creek, a trapezoidal drain, was reconfigured as a Living Stream to both be able to filter the water running off a large urbanised catchment but also

to simultaneously to allow for regular recreational activities such as jogging, dog walking, or bird-watching (Polyakov et al., 2016, p. 6). The effects of upgrading of Bannister Creek to the level of a Living Stream on house prices, calculated using the ‘hedonic price approach’ was initially negative –perhaps reflecting the issues of noise and inconvenience which construction poses to adjacent residents (Polyakov et al., 2016, p. 9). However the negative impact was fully reversed within a five year period; and within about seven or eight years there was a substantial, statistically significant amenity benefit that reflected itself in increased property values in the adjacent areas (Polyakov et al., 2016, p. 9).

This finding is not surprising as there have been a number of studies in Perth, and elsewhere reviewing the effects of POS on property prices. These have found that bush reserves and lakes have significant and positive impacts on property prices in the adjacent area (Pandit, Polyakov, & Sadler, 2013, p. 16; Geoff Syme, 2016). Significantly, the literature does not show a similar effect of small reserves and sports reserves, generally without water bodies or substantial vegetation, on adjacent property prices (Pandit et al., 2013, p. 16). These findings indicate that it is possible that the endemic vegetation and water bodies typical of Living Streams which may be, in part, the elements responsible for the positive effects on adjacent property prices. Furthermore the generally passive – as opposed to active – recreation function of Living Streams is also is linked to greater property price uplift in

surrounding areas (Crompton, 2007, p. 216).

Wetland visitation

While the above section introduces the positive effects of Living Streams on property values in Perth this section examines the visitation of wetlands –which are morphologically and functionally similar to Living Streams –by surrounding residents. In a 2001 study of residents in comparatively new suburban areas in Perth with small lot sizes (typically less than 500m2), it was found that it is wetlands and not parks which receive the greater visitation – in contrast with suburban areas with ‘normal’ lots of 700m2 and more. The attractiveness of water bodies in urban landscapes is well attested and may partly explain this result (Geoffrey Syme, Fenton, & Coakes, 2001, p. 169) –however it may be also that residents in smaller lots development are seeking a connection with ‘nature’ to compensate for the lack of greenspace on their smaller residential lot. This dynamic generally is referred to as the ‘compensation hypothesis’ in which residents compensate poor access to private greenspace by using public greenspaces such as parks which offer this in a well vegetated form (Byrne, Sipe, & Searle, 2010, p. 164).

While wetlands studied (Geoffrey Syme et al., 2001) are less linear than typical Living Stream orientated POS it could be presumed that the increased visitation of wetlands in small lot developments could also extend to Living Streams. Indeed the descriptions of wetlands employed in the 2001 study describe a space very much like that of

Living Streams, the wetlands constituting ‘relatively open park space for active and passive recreation surrounding them. Bird life abounds. Each of the lakes has some natural vegetation at the lakeside through which visitors can walk’ (Geoffrey Syme et al., 2001, p. 163).

By way of conclusion to this first section of the report, the literature and economic data about Living Streams in Perth, and (related) visitation figures for wetlands, suggests Living Streams are likely to be considered attractive, high amenity environments by surrounding residents, indicating that they should be considered as amenable POS –regardless of their linearity, overlapping ecological, hydrological and recreational roles. Despite this positive assessment, urban projects successful or otherwise always entail lessons (Ellis, 2016). In this spirit, the following section of this report examines how the urban design Living Stream POS could be conducted so as to increase the amenity offered.

25

Tre es an d shrub s

Turf

Pa th net work

Sp orting fa cilitie s

Living stre am b ase c ha nne l a nd la ke s

26

Generally the Living Stream projects studied tended to rate highly because were generally well-equipped and furnished spaces, regardless of their hydrological function. Thus the most reliable quantitative measure of POS attractiveness yet developed in Perth indicates that the Living Streams case study projects should be considered attractive POS, at least when ‘attractiveness’ is calculated by this method. This map is of the Byford case study project.

0 190 380 95 Meters 27

Tre es an d shrub s

Turf

Pa th net work

Sp orting fa cilitie s

Living stre am b ase c ha nne l a nd la ke s

28

The Piara Waters case study project

0 140 280 70 Meters 29

31

The Piara Waters Living Stream

The Piara Waters Living Stream case study project (photo courtesy of brett Wood-Gush)

Tre es an d shrub s

Turf

Pa th net work

Sp orting fa cilitie s

Living stre am b ase c ha nne l a nd la ke s

32

The Wandi case study project

0 80 160 40 Meters 33

The Wungong case study project

Tre es an d shrub s

Turf

Pa th net work

Sp orting fa cilitie s

Living stre am b ase c ha nne l a nd la ke s

34

0 60 120 30 Meters 35

When the four Living Stream case study projects, being examined in this research, were evaluated against these criteria the Living Stream projects scored an average of 70 out of 100. In the original project conducted by the School of Population Health, which evaluated 2,500 parks, recreational grounds, sports fields, commons, esplanades, and buffer strips the average score was 47.5.

Attributes/ Weight assigned

Shade along paths (%)

Lawns irrigated (%)

Scores for case studies (out of 100) 36

Walking paths present (%)

Sporting facilities present (%)

Adjacent ocean or river (%)

Water feature present (%)

Quiet surrounding roads (i.e., cul de sac or minor road only)

Lighting present (%)

Along paths

In some areas

In barbecue/play equipment areas only

No lighting

Birdlife present (%)

Good Medium Poor

Very good

Very poor No paths

Waters Wandi Wungong Byford 17 14 14 10 15 15 15 15 14 14 14 14 10 0 0 13 0 0 0 0 8 8 8 8 4 8 8 6 5 3 0 0 4 4 4 4 69 63 71 74 37

Piara

Urban design strategies

This section develops ideas for how the amenity of Living Streams and Park avenues could be enhanced – from an urban design perspective...

38

Enhancing the amenity of Living Streams through urban design strategies

While the previous section examined the various cases for a characterisation of Living Streams as generally amenable POS, this section develops strategies for how the amenity of Living Streams could be enhanced – from an urban design perspective. This exercise is carried out in relation to the available literature of Living Streams, and related linear parks (i.e. Park Avenues), interviews with practitioners, regulators and directors involved in designing and delivering these projects (Brookes, 2016; Brown, 2016; Ellis, 2016; Emerge Associates, 2016; Grace, 2016; Taylor, 2016; Wood-Gush, 2016) and examination of the Living Stream case study projects. These principles are set out in relation to their approximate scale of application, from the regional scale to the site scale.

39

Regional mapping of the emerging Living Stream case study projects shows that, outside of the immediate Wungong project area, the Living Streams appear to be generally not well coordinated with regional destinations, in the form of urban centers, schools, and ROS, and movement systems such as bike paths.

Major w etla nd s/ dra ins/ w a terc ourse s

Bike route s

City c ent res

Urb an a rea s

Sc hools

Pub lic O p en S pa ce

Ca se stud y proje c ts

40

Wandi

0 2, 900 5, 800 1, 450 Meters 41

Byford

Piara Waters

Wungong

Note: this diagram (and subsequent diagrams) are based on an adapted version of the Piara Waters Living Stream

School Regional Open Space Urban destination 42 Living Stream path netwrok

Integrate Living Streams with destinations

Living Streams are potentially important elements to encourage active modes of transport, in part, because ‘flowing water… leads you into a landscape as it flows from here to there…’ (Geoff Syme, 2016). Moreover compared to streets, with their attendant vehicles, Living Streams provide a very safe environment for both children and adults to ambulate (Ellis, 2016). However the degree to which Living Streams are used for active modes of transport, such as walking and cycling, relies not just on such factors but more generally the destinations to which they connect.

As a result of Living Streams being retrofitted drains they often do not provide direct connection to existing destinations such a Regional Open Spaces (ROS), district and neighbourhood centres, and primary or high schools – largely because their alignment is governed by hydrological not cultural factors. Indeed regional mapping of the emerging Living Stream case study projects shows, outside of the Wungong project area, that the Living Streams appear to be generally not well coordinated with regional destinations, in the form of urban centers, schools, and ROS, and movement systems such as bike paths.8

Developed to its fullest however, the integration of Living Streams could result in a high amenity regional scale active transport network in which hydrology, ROS, schools and urban destinations

8 Given the area is still under construction, such an assessment may change over time.

are woven together into one connected matrix. In this respect Living Streams could be considered as a structuring principle for entire greenfield developments, and the destinations which it contains (Kullmann, 2011, p. 77).

One existing example of connecting Living Streams to destinations is the Wungong project masterplan which employed the linearity of the Living Streams and Park Avenues to encourage people to move along their length, to the Wungong River, the community parks situated at the heart of each neighbourhood and each of the schools proposed in the development area (Weller, 2009, p. 251). As Wungong engineer Bill Grace explains ‘the Living Streams were considered a bicycle and pedestrian thoroughfare that would go somewhere. Idea of having density around the Living Streams was that they would be the destinations that you would be going to’ (Grace, 2016).

43

44

Open

District Open Space

Regional

Space

Local Open Space

Living Stream

Integrate Living Streams with local, neighbourhood and district POS types

One aspect of the integration of Living Streams that is particularly important is the degree to which they form part of an integrated POS system at the local, district and ideally regional scale. To achieve such an integrated POS system means thinking of POS units not as an isolated component (be it a Living Stream, street, or local park) but as a ‘vital part of urban landscape with its own specific set of functions’ (Richard Rogers in Ward Thompson, 2002, p. 61). With respect to Living Streams this could be, in part, achieved by collocating traditional neighbourhood local, neighbourhood and district parks with Living Stream POS. This approach provides a number of benefits with respect to the provision of amenity.

Firstly, when other POS types are collocated with Living Streams some of the burden of dealing with major flood events can be shifted from the Living Stream to a broader area of POS which in turn means the Living Stream banks can be less steep, less reinforced with walls, and subsequently more useable and often more attractive. As hydrologist Helen Brookes, who is engaged in the Wungong project, explains an explicit focus on dealing with drainage just within the drainage reserve tends to deliver a situation in which the Living Stream is ‘too steep to be useable, but not vegetated enough to be of environmental value, ‘it’s nothing…’ (Brookes, 2016). This integration is not always easy to achieve, and in a Perth

context has tended to require extensive negotiation with the regulating organisation, Water Corporation. Helen Brookes, describes ‘We got to the point where as long as the five year flood event was within their (drainage corridor) landholding they could cope with the rest going outside their landholdings into POS’ however this outcome required a prolonged period of negotiation (Brookes, 2016).9

Moreover the integration of other forms of POS with Living Streams means that spatial dimension of the Living Stream is varied, thus creating a (potentially) more diverse and engaging experience for users. Indeed as Karl Kullmann explains a greater overall diversity of spatial types means that ‘a variety of park users are able to find their niche somewhere, frequently forming ‘subcultures’ along the way’ (Kullmann, 2011, p. 77).

Furthermore, given the role of local, neighbourhood, district parks and Living Streams in maintaining biodiversity, forging direct connections between POS types is potentially important for allowing the movement of wildlife (Weller, 2009, p. 251). While this could be perceived as having little or no impact on the amenity provided by the Living Stream, data around the presence of birdlife in parks increasing their relative attractiveness suggests otherwise (Francis et al., 2012, p. 1574).

The Honeywood Project in Wandi provides an example of where a Living Stream has been integrated with a series of neighbourhood scale parks. As

9 This experience may be become a ‘thing of the past’ with Water Corporation’s relatively new drainage and liveability program (Water Corporation, 2016).

45

46 the designers, Emerge explain:

We have created open space either side of (the Living Stream) which is really well used and appreciated - the City of Kwinana thinks it was a great outcome and are very supportive of it. It was all about getting (active and passive POS) integration around the living stream (Emerge Associates, 2016)..

While largely mono-functional, low quality spaces may engender ‘necessary’ activities (such as dog walking), high quality POS such as provided in the Honeywood project –which is varied in proportion and potential usage – is able to accommodate a range of optional recreational and social activities producing a ‘place and situation which invites people to stop, sit, eat, play, and so on’ (Francis et al., 2012, p. 1571).

Integration between the Living Stream reserve and POS at the Wandi case study.

47

Vehicularcrossing

Vehicular crossing

Perpendicular streets

Informal pedestrian crossings

48

<80m >200m

Integrate Living Streams with the street network

Beyond integration with POS types the spatial relationships between a Living Stream and the surrounding street network is vitally important for the maximising of the amenity it provides, visual or recreational, to surrounding residents. Firstly it is important to, within reason, maximise the number of streets running perpendicular to the Living Stream to boost the ability of people to walk to the Living Stream (Kreiger, 2004, p. 34),10 and view it from their properties. When the networks surrounding Living Streams are designed in this way they operate as ‘catching features, meaning that they are relatively easy to encounter’ (Kullmann, 2011, p. 78) by people walking, or cycling in the street network.

As the same time as the number of roads perpendicular to the Living Stream should be maximised, the number of roads that cross Living Streams should be kept to a relative minimum (Weller, 2009, p. 251). The effect of a large number of roads crossing the Living Stream is to dissect the Living Stream into smaller components, create both visual barriers and potentially obstructions to the movement of pedestrians and cyclists – arguably situations that can be linked to a decrease in the amenity provided by the Living Stream. This situation also incurs great cost because the number of 10 This concept is partly borrowed from urban waterfront developments in which ‘To avoid the less desirable consequences of a thin line of development, a city must create perpendicular streets and civic corridors that are as desirable as the shoreline drive’ (Kreiger, 2004, p. 34).

bridge/ culvert structures required increases – and reduces the project budget able to be directed towards other landscape design features.

While all the selected case study projects illustrate both these principles to various degrees, the Piara Waters Living Stream project provides an exemplar in this respect with its perpendicular streets typically at 80 metre spacing and streets crossing the Living Streams generally at 200 metre spacing.

Streets running adjacent to the Living Stream should be of a minimal width and planted with street trees in such a way that binds the street into the Living Stream as one ‘single composition.’ This perception can also be increased by grading the adjacent street so that it ‘falls’ towards the Living Stream, and has flush kerbs, all of which helps to unify the adjacent street and the Living Stream. If such measures are not undertaken Living Streams can appear to be spatially separate from the adjacent street – a situation which is less likely to draw people into the Living Stream environment through its disconnection with the surrounding fabric.

49

50

Ideally the street running adjacent to the Living Stream should be of a minimal width and planted with street trees in such a way that binds it into the Living Stream as one ‘single composition.’ This example from the Wandi case study reveals a disconnect between the Living Stream POS, the streetscape and the surrounding suburban form.

51

Urban density 52

Increase density around Living Streams

As the previous section examined, Living Streams are perceived to offer a substantial degree of amenity to residents of the adjacent areas, a phenomenon which is reflected in boosted house values (Polyakov et al., 2016, p. 9). As such Living Streams potentially could be a structure upon which urban density could be grafted, in part because they offer amenity and as such an incentive for people to live at higher densities than otherwise may be achieved (Bolleter & Ramalho, 2014).

In particular there are a number of synergies that could form between the higher density housing and Living Streams. By way of one example, researchers have found that children living in higher density housing have a greater need for ‘publicly accessible greenspaces for play, mental health and social and physical development’ (Sipe & Byrne, 2010, p. 5) – something that Living Streams could be specifically designed to offer. Moreover, having direct views to a Living Stream from higher density dwellings has many potential health benefits. Indeed research tells us such views of ‘nature’ from a home (or indeed workplace or car window) can be restorative, lessen psychological distress (Francis et al., 2012, p. 1574), and have general mental benefits (McDonald, 2015, p. 198). From another perspective Living Streams are ‘all edge and no middle, and (as such are) heavily defined by their margins’ (Kullmann, 2011, p. 74). As a result denser urban edges adjacent to Living

Streams may provide a more appropriate urban ‘frame’ in comparison to the conventional suburban density typically delivered, as well as increasing the surveillance, usage and safety of the Living Stream.11

Moreover deploying compact urban form along the edges of Living Streams has significant potential to yield dwellings because the edge length compared to area of such POS is particularly high. For example in the Wungong project, 21 linear kilometres of Park Avenues are planned to be provided which equates to potentially 42 linear kilometre of denser housing that fronts the avenues (Taylor, 2016). In this respect the Park Avenues (and Living Streams) could incentivise (Ellis, 2016) and compensate for significant areas of residential density. Moreover by densifying around Living Streams developers are able to recoup some of the capital that is otherwise lost in having a significant amount of land bound up in Living Streams.

Despite the potential of denser housing being concentrated along the edges of Living Streams, only the Wungong masterplan exploited this potential. This was achieved through correlating urban density with Living Streams and Park Avenues.

53

11

Physical health benefits

Mental health benefits

Increased property values

Nature experience

Enhanced water knowledge

Living Stream

urban form

Densified

Passive surveillance Capital ($) Activation 54

Provide a natural experience

Today, for many people in urbanised areas, ‘the park is a place which resonates with concepts of the original ‘garden’ and where contact with nature may have a metaphysical or spiritual dimension, even if only at the subconscious level…’ (Ward Thompson, 2002, p. 66). Indeed the increased visitation of residents of small lot developments in Perth to wetlands, discussed in the previous section, hints to us that they are seeking a connection with ‘nature’ to compensate for the lack of greenspace on their smaller residential lot (Geoffrey Syme et al., 2001, p. 169).

In relation to the fact that (on a day to day basis) ‘the average Australian is alienated from the natural world’ (Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 198) – Living Streams potentially have a very important role to play in providing this experience of ‘nature’ to residents as the benefits are potentially huge. As Robert Macdonald explains:

…the mental health benefits of access to nature shows that even a brief time-out in nature can reduce this psychological toll. Stress levels decrease, and people’s ability to focus increases. There is even evidence that time in nature reduces the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and reduces the odds of domestic violence between their parents. These mental health benefits are in addition to the benefits to physical health from recreation and the aesthetic benefits (2015, p. 198).

While these benefits are yielded by most forms of POS, to varying degrees, Living Streams have particular potential in this respect because of their linearity they typically adjoin, and are near to, a large proportion of houses making them highly accessible. Moreover because of their typically passive recreational focus, the presence of water and biodiversity means they form an apt substitute for ‘nature’ in the city.

Due to these factors Living Streams in Perth should be designed, as much as possible, to provide access to nature –however this term needs to be clarified. John Dixon Hunt has helpfully separated landscapes into three categories, first nature, second nature and third nature. First nature is the ‘pristine nature of wilderness, unaffected by the presence of mankind….’ Second nature refers to ‘cultural landscapes which, very broadly, can be taken to include all agricultural landscapes and all the landscapes of our settlements.’ Hunt reserves ‘third nature’ for landscapes of this last sort, a category which includes all parks and gardens (Thompson, 2011, p. 19). The ‘nature’ which could be emulated in Perth’s future Living Streams is located between second and third nature, recognizing that the re-creation of a pure first nature is practically and philosophically impossible – and also not necessarily desirable in an urban context. In this respect such Living Streams could provide an ecologically rich, diverse (Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 195; Water Corporation, 2016, p. 1), immersive (Kullmann, 2011, p. 80), loose-fit, wild, messy and informal space (Ward Thompson, 2002, p. 70) which allows for exploration and play,

55

particularly by children (Louv, 2007) and provides a window on the ecology of running waters which can be used by local schools (Brown, 2016; Pen & Majer, 1994, p. 198) – particularly if schools are located adjacent to Living Streams.

The importance of Living Streams being able to immerse or ‘lose oneself’ themselves in a ‘natural’ experience is crucial (Giles-Corti et al., 2005, p. 170).

Karl Kullman describes a linear park that can provide this immersive experience as a ‘thicket,’ as he explains:

This effect is ostensibly created with overgrown vegetation, but can also be a product of constructed complexity and messiness. From within a thin park constituted as a thicket, depth of field, interior and exterior become obfuscated, making the experience from within both explorative and disorienting (Kullmann, 2011, p. 80).

Topographic shifts, screening vegetation and tree cover (Kullmann, 2011, p. 78) can all play a part in facilitating a visitors desire to ‘lose one’s self’… Immersion also relies on the path system, for substantial areas, deviating from the road edge and being ‘immersed’ within the body of the Living Stream POS.

Moreover Living Streams also could provide a more powerful experience of temporality and change (Geoff Syme, 2016), due to changing water flows, than typical parks in Perth – an aspect of Living Streams which helps to illustrate Perth’s drying climate and increase awareness in this respect. This is important because research has found a clear correlation between level

of knowledge about water and behaviour (Water Innovation Advisory Group, 2016, p. 27).

Their temporality also implies the potential for a different management approach for Living Streams, as opposed to one where ecological processes are usually arrested in an unchanging, puritanical state (Ward Thompson, 2002, p. 67). As Catharine Ward Thompson explains:

A different management philosophy might encourage the cyclical nature of plant growth and succession, erosion and siltation of water bodies, etc. Parks (and Living Streams) could be allowed to change over time in the kind of homeorrhetic or long-term, cyclical way that natural succession follows, rather than be subject to the homeostatic regulation of equilibrium around an unchanging norm (Ward Thompson, 2002, p. 67).

Arguably all of the Living Stream case studies examined in this report are, to a degree, derivatives of the picturesque/ pastoral movement in which the image is regulated as a largely ‘unchanging norm’ – typified by the large turf expanses which characterize many of Perth’s suburban parks and indeed generally the Living Stream case study projects. Arguably Living Stream projects in Perth hold the potential to present landscape architecture with ‘compelling aesthetic alternatives’ to the picturesque/ pastoral modes ‘that are more authentic representations of contemporary conceptions of urbanism, ecology, culture and nature’ (Kullmann, 2011, p. 81). Indeed design is becoming increasing skilled at creating these

56

spaces while still providing paths and places that offer universal access.

57

BaseflowchannelImmersive,lowerlevelwalkingexperience

Geometrictreeplantingunifiescorridor

Parking

Sharedpedestrian/bicyclepath TrafficcalmedstreetFrontgardenfacingLivingStream

2-3storeyterracebdgs

Views

Regionaldestinations

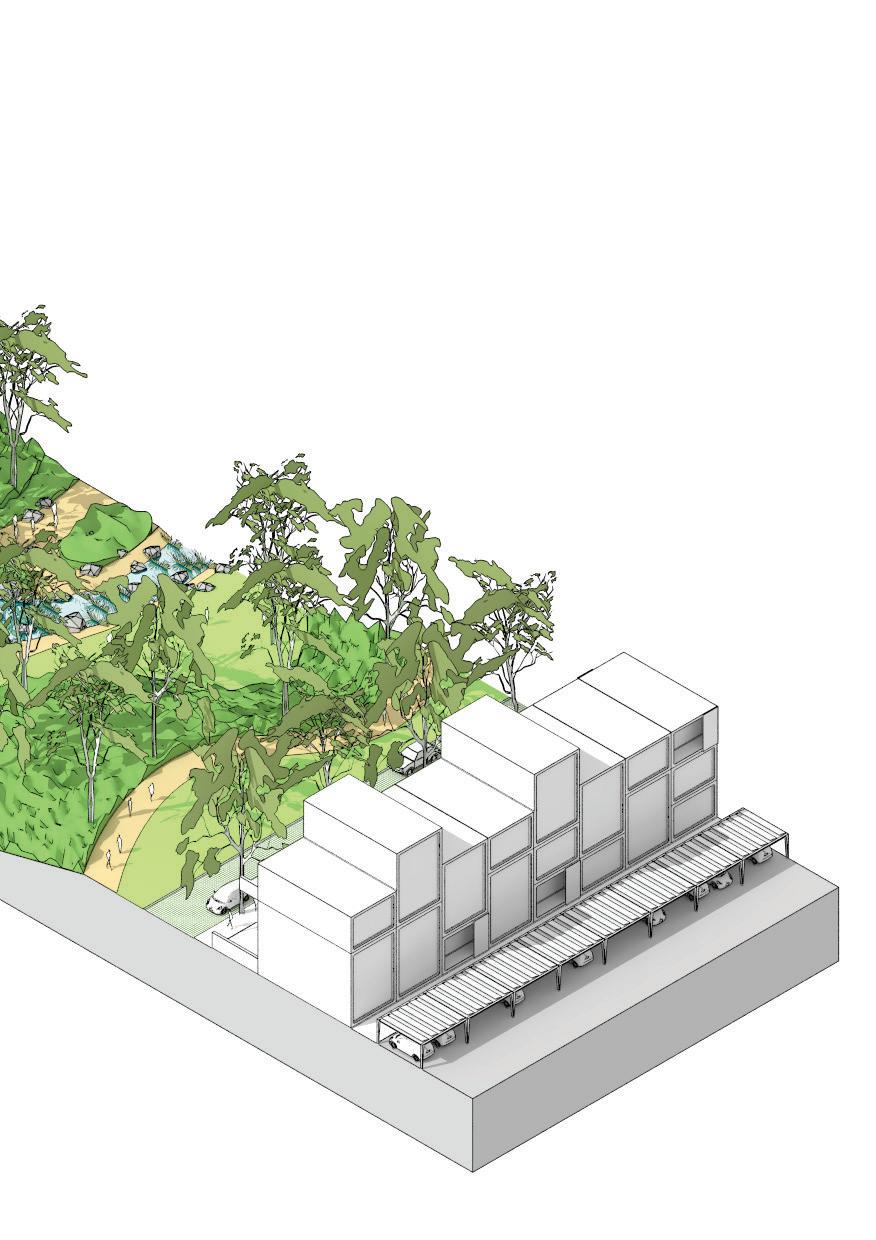

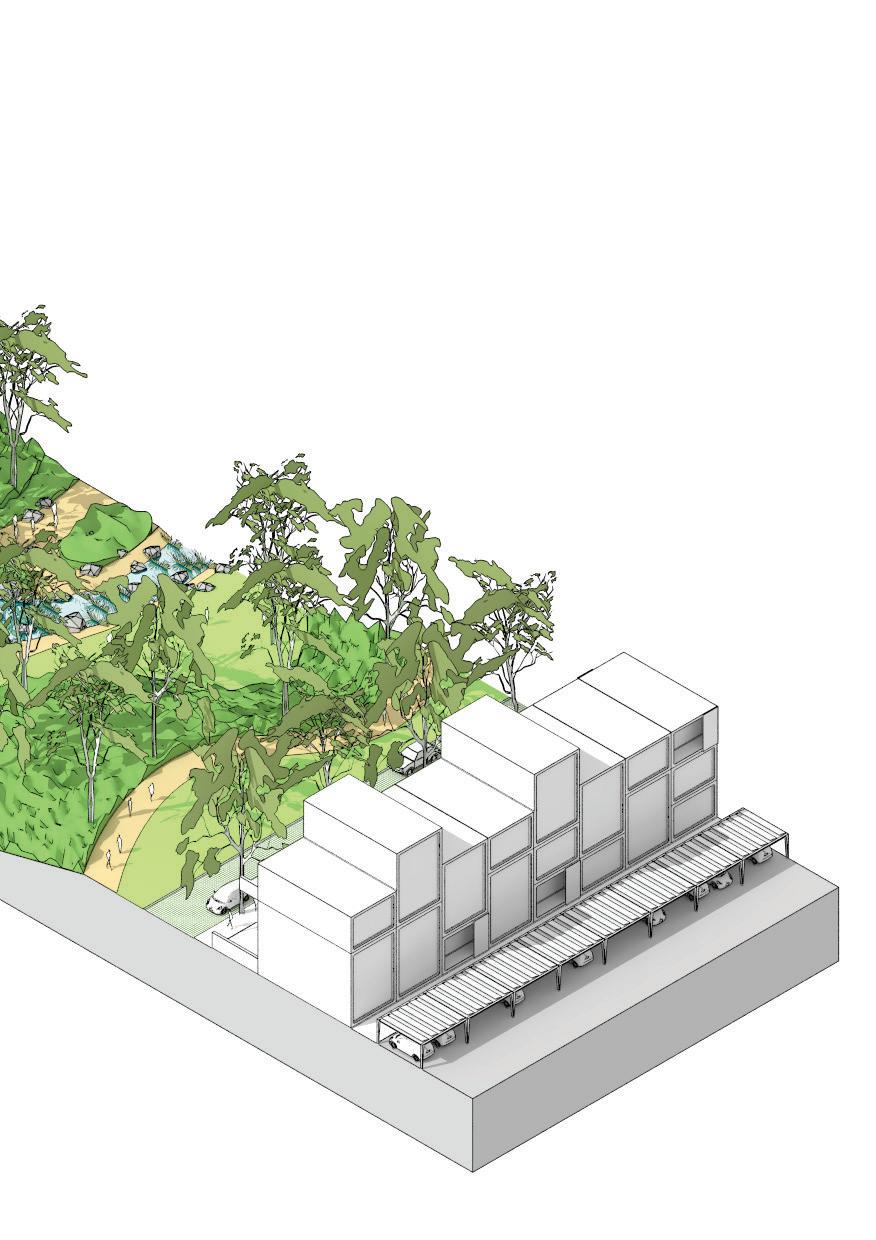

A proposed Living Stream sectional model for an active stream with water conveyance and setback buffer. Please note this proposed model would need to be varied to accommodate different POS reserve widths and varying drainage and active transport requirements.

2-3storeyterracedwellings

PrivateparkingRearlaneway

corridor Overlandflow 59

Flushkerb

Conclusion

As Perth expands further into waterlogged land the Living Stream and Park Avenue model is likely to be employed more and more frequently...as such it is important that this model is well understood...

60

Conclusion

This research has addressed both the case for why Perth’s Living Streams and Park Avenues should generally be considered POS, in relation to key data from Perth. Indeed the report has found that in some cases local level bucolic space, such as Living Streams, can provide greater uplift in adjacent land values as well as allowing for greater connection to nature, in comparison to some District sporting oval POS. Furthermore this report has explored how the amenity of Living Stream and Park Avenue orientated POS could be enhanced through the application of a number of urban design principles. The accompanying table sets out these principles in relation to the case study projects and provides a broad measurement of whether the principles find expression in the selected projects. The finding is that there is much potential for such principles to be tested, as they typically do not find expression in these constructed projects – and yet there is substantial opinion and evidence assembled in this report that suggests such principles could uplift the amenity provided by Living Stream and Park Avenue orientated POS.

While it is not the explicit focus of this report, how such principles could be practically applied varies as to the scale of the principle. The integration of Living Streams and Park Avenues into a network connecting to destinations requires the coordination of District and Local structure plan areas as part of existing planning approval processes

(Department of Planning & Western Australian Planning Commission, 2015, p. 13). The integration of Living Streams and Park Avenues with other POS types requires water related regulatory bodies such as Water Corporation, Department of Water, Department of Planning and Local Government to become more flexible in terms of how the burden of flood management is dispersed outside of existing drainage corridors.

Integration of Living Streams with the surrounding street network requires coordination with local government traffic engineers to develop street typologies which work to maximise the access to and amenity of the POS. The development of urban density in correlation with Living Streams and Park Avenues requires the backing of developers, who need to be convinced that consumers will trade-off higher larger lots for access to Living Stream POS. Finally the provision of a natural experience requires coordination with local government level maintenance planning, the Department of Fire and Emergency Services, and indeed local schools and groups that are likely to access this ‘natural’ amenity. Even a brief summation of the stakeholders and regulating bodies that have a role in Living Stream creation indicates the complex economic, regulatory and spatial situation which proponents must engage with.

Nonetheless, we believe it is important that such principles are tested and developed because as Perth expands further into waterlogged land that is characteristic of geomorphic wetlands, the Living Stream and Park Avenue model for dealing with complex drainage

61

conditions is likely to be employed more and more frequently. It is vital that this urban and landscape model is well understood for the POS amenity of Perth’s emerging, and yet to be built, outer suburbs to be maximised. This research has been directed towards this end.

Category of analysis Integrate with destinations Integrate with other POS types

Byford

Piara Waters Wandi

Wungong (masterplan)

Key

Project doesent meet this criteria

Project partly meets this criteria

Project meets this criteria

62

This table sets out the proposed Living Stream urban design principles in relation to the case study projects. The finding is that there is much potential for such principles to be tested, as they typically do not find expression in these constructed projects – and yet there is substantial opinion and evidence assembled in this paper that suggests such principles could uplift the amenity provided by Living Stream orientated POS. Integrate with street network Increase density around Living Streams Provide a natural experience

63

64

As Perth expands further into waterlogged land that is characteristic of geomorphic wetlands, the Living Stream model for dealing with complex drainage conditions is likely to be employed more and more frequently.

65

References

66

References

Ask.com. (2008). Dictionary. Dictionary.com website. from http://dictionary.reference. com

Bernhardt, E. S., & Palmer, M. A. (2007). Restoring streams in an urbanizing world. Freshwater Biology, 52(4), 738-751.

Bolleter, J., & Ramalho, C. (2014). The potential of ecologically enhanced urban parks to encourage and catalyze densification in greyfield suburbs. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 9(3), 54-65.

Brookes, H. (2016). Interview with Helen Brookes, Director Essential Environmental. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Unpublished.

Brown, S. (2016). Interview with Suzanne Brown, Manager Drainage and Liveable Communities Water Corporation. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Unpublished.

Byrne, J., Sipe, N., & Searle, G. (2010). Green around the gills? The challenge of density for urban greenspace planning in SEQ. Australian Planner, 47(3), 162-177.

Crompton, J. (2007). The impact of parks on property values: empirical evidence from the past two decades in the United States. Managing Leisure, 10(4), 203-218.

Department of Planning, & Western Australian Planning Commission. (2015). Draft Perth and Peel @3.5 million. Perth: Western Australian Planning Commission.

Ellis, J. (2016). Interview with John Ellis, Ex Armadale Redevelopment Authority Director. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Unpublished.

Emerge Associates. (2016). Interview with Emerge Associates. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Not published.

Francis, J., Wood, L. J., Knuiman, M., & Giles-Corti, B. (2012). Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Social science & medicine, 74(10), 1570-1577.

Giles-Corti, B., Broomhall, M. H., Knuiman, M., Collins, C., Douglas, K., Ng, K., . . . Donovan, R. J. (2005). Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2), 169-176.

Grace, W. (2016). Interview with William Grace, Adjunct Professor Australian Urban Design Research Centre. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Unpublished.

Jones, E., Burrell, B., Morris, W., Wong, T., & Stein, L. (2010). Armadale Redevelopment Authority Wungong Urban Water Project Review: Wungong Independent Peer Review Panel.

67

Kreiger, A. (2004). The Transformation of the Urban Waterfront. In Urban Land Institute (Ed.), Remaking the Urban Waterfront (pp. 22-47). Washington: The Urban Land Institute.

Kullmann, K. (2011). Thin parks/thick edges: towards a linear park typology for (post) infrastructural sites. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 6(2), 70-81.

Louv, R. (2007). Leave no child inside. Orion Magazine, 57(11).

McDonald, R. (2015). Conservation for Cities: How to Plan and Build Natural Infrastructure. Washington: Island Press.

Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority. (2012). Wungong Urban Water Redevelopment Public Open Space Policy. Perth: Government of Western Australia.

Middle, G., & Tye, M. (2011). Emerging Constraints for Public Open Space in Perth Metropolitan Suburbs. Perth: Department of Sport and Recreation, Centre for Sport and Recreation Research, Curtin University.

Pandit, R., Polyakov, M., & Sadler, R. (2013). Valuing Public and Private Urban Tree Canopy Cover. Not yet published

Pen, L., & Majer, K. (1994). Drains versus Living Streams. Paper presented at the How Do You Do It?: Water Sensitive Urban Design Seminar 1994; Proceedings.

Polyakov, M., Fogarty, J., Zhang, F., Pandit, R., & Pannell, D. J. (2016). The value of restoring urban drains to living streams. Water Resources and Economics.

Singh, B., Pal, Y., Clohessy, S., & Wong, S. (2012). Acid sulfate soil survey in Perth metropolitan region, Swan Coastal Plain WA. Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia.

Sipe, N., & Byrne, J. (2010). Green and open space planning for urban consolidation- A review of the literature and best practice. Brisbane: Griffith University.

Sugiyama, T., Francis, J., Middleton, N. J., Owen, N., & Giles-Corti, B. (2010). Associations between recreational walking and attractiveness, size, and proximity of neighborhood open spaces. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1752-1757.

Swaffield, S., & Deming, E. (2010). Landscape Architecture Research. New Jersey: Wiley.

Swaffield, S., & Deming, E. (2011). Research Strategies in Landscape Architecture: Mapping the Terrain. Journal of Landscape Architecture, Spring 2011, 34- 45.

Syme, G. (2016). Interview with Geoff Syme Editor in Chief Journal of Hydrology. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Not published.

Syme, G., Fenton, M., & Coakes, S. (2001). Lot size, garden satisfaction and local park

68

and wetland visitation. Landscape and Urban Planning(56), 161-170.

Taylor, M. (2016). Interview with Matt Taylor, Ex project director for the Wungong project In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Not published.

Thompson, I. (2011). Ten Tenets and Six Questions for Landscape Urbanism. Landscape Research, 37(1), 7-26.

Ward Thompson, C. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60, 59-72.

Water Corporation. (2016). Drainage for Liveability Fact Sheet: Living Streams in Water Corporation assets. Perth: Water Corporation, Department of Water.

Water Innovation Advisory Group. (2016). Water Innovation Advisory Group Report to Minister. Unpublished: Department of Water.

Weller, R. (2009). Boomtown 2050. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

West Australian Planning Commission, & Department of Planning. (2007). Liveable Neighbourhoods; A Western Australian Government Sustainable Cities Initiative. In W. A. P. Commision (Ed.). Perth.

Wong, T. (2006). Water sensitive urban design- the journey thus far. Australian Journal of Water Resources, 10(3).

Wong, T. H. F., & Brown, R. R. (2009). The water sensitive city: principles for practice. Water Science and Technology, 60(3), 673-682.

Wood-Gush, B. (2016). Interview concerning Wungong project with Brett Wood-Gush, Principal Urban Designer Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority. In J. Bolleter (Ed.). Unpublished.

Wood‐Gush, B. (2008). Wungong urban water project: Going beyond liveable neighbourhoods in the pursuit of environmental planning best practice. Australian Planner, 45(2), 8-11.

69

Contributors

Julian Bolleter

Julian is an Assistant Professor at the Australian Urban Design Research Centre (AUDRC) at the University of Western Australia. His role at the AUDRC includes teaching a master’s program in urban design and conducting urban design related research and design projects.

Dr Joerg Baumeister

Joerg is Director of the Australian Urban Design Research Centre (AUDRC) and has been researching, practising, educating and exploring Urban Design and Architecture for more than 20 years in Australia, Europe, Africa, and on the Arabian Peninsula.

70

71