He pou atua, he pou whenua, he pou tangata.

Ko Waitematā te moana

Ko Waikōkota te whenua.

Ko Te Pou Whakamaharatanga mō Māui Tikitiki a Tāranga te tohu o te kaha, o te kōrero, o te whakapapa o tēnei wāhi, o tēnei whare.

Nau mai e te tī, e te tā ki te whare kōrero, ki te whare whakaari o ASB ki te tahatika o te moana.

Mauri tau, mauri ora!

Pouwhakamaumāharatanga mō Māui-Tikitiki-a-Tāranga

The Memorial Post of Māui the Topknot of Tāranga

Robert Jahnke ONZM (Ngāi Taharoa, Te Whānau a Iritekura, Te Whānau a Rākairo o Ngāti Porou) 2016

Laminated tōtara and Corten steel

Proudly commissioned by Auckland Theatre Company for ASB Waterfront Theatre

The symbols of support, of strength and of guardianship stand fast and proud.

The waters of Waitematā ebb and flow against the shores here at Waikōkota, the land upon which we stand.

The pou of remembrance to Māui Tikitiki a Tāranga stands tall as a beacon of courage, of stories passed down and of the history that connects us all to this place and to this space.

We welcome you all from near and far to this house of stories, to the ASB Waterfront Theatre.

Mauri tau, mauri ora!

ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY KEN LUDWIG

22 APR – 10 MAY 2025

’AGATHA CHRISTIE’ and the Agatha Christie Signature Mark are trademarks of Agatha Christie Ltd. All rights reserved. The rights to this play are controlled by Agatha Christie Ltd. For further information about this play, others by Agatha Christie and about other stage adaptations of her stories, please visit: agathachristie.com Murder on the Orient Express © 2016 Agatha Christie Limited & Ken Ludwig. All rights reserved. adapted from Murder on the Orient Express © 1934 Agatha Christie Limited. All rights reserved.

MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS, AGATHA CHRISTIE, POIROT, the Agatha Christie Signature and the AC Monogram Logo are registered trademarks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere. All rights reserved.

Bronwyn Ensor — Greta Ohlsson

Sophie Henderson

Countess Andrenyi

Jennifer Ludlam Princess Dragomiroff

Mayen Mehta Hector MacQueen

Ryan O’Kane — Colonel Arbuthnot & Samuel Ratchett

Mirabai Pease Mary Debenham

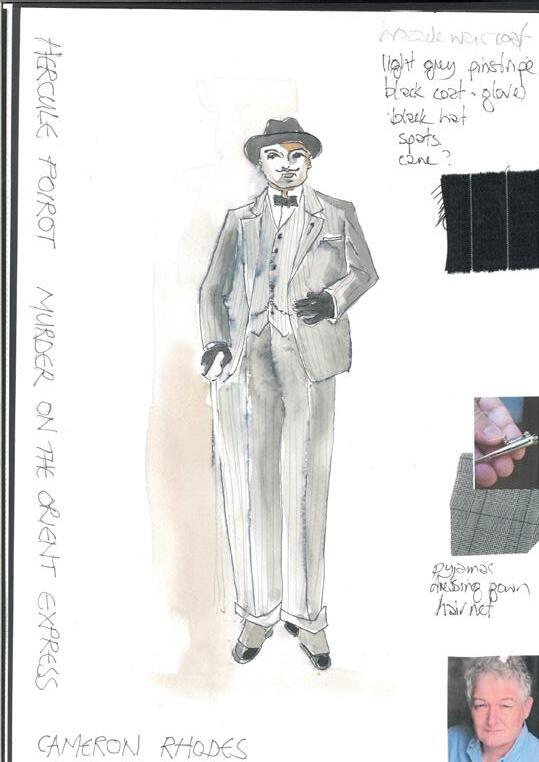

Cameron Rhodes Hercule Poirot

Jordan Selwyn Michel & Head Waiter

Rima Te Wiata — Helen Hubbard

Edwin Wright Monsieur Bouc

Writer — Agatha Christie

Stage Adapter Ken Ludwig

Direction — Shane Bosher

Set Design John Verryt

Lighting Design — Sean Lynch

Costume Design Elizabeth Whiting

Composition & Sound Design

Paul McLaney

Motion Design Harley Campbell

Accent & Dialect Coach

Kirstie O’Sullivan

Intimacy Coordinator Todd Emerson

Engine Room Assistant Director —

Nī Dekkers-Reihana

Paul Barrett — voice of Train Announcer & Radio Parts

Sophie Hambleton — voice of the Mother

Olivia Tennet — voice of Daisy Armstrong

Education Pack Writers — Anna Richardson and Jonathan Price

Education Pack Designer — Wanda Tambrin

The novel Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie was first published in January 1934. It was later adapted many times for radio, film, video games, television, board games and comics in many languages. The Christie Estate commissioned playwright Ken Ludwig to adapt it for the stage. The world premiere was produced by the McCarter Theatre Centre (Emily Mann: Artistic Director, Timothy J. Shields: Managing Director), Princeton, New Jersey, opening on Tuesday 14 March 2017 before transferring to Hartford Stage (Darko Tresnjak, Artistic Director, Michael Stotts, Managing Director), Hartford, Connecticut. Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express had its New Zealand premiere at The Court Theatre, Christchurch, in a production directed by Dan Bain, opening on Saturday 2 March 2024.

Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is the second play in Auckland Theatre Company’s 2025 season. Directed by Shane Bosher, it began previews on Tuesday 22 April and opens on Thursday 24 April 2025.

The production is 2 hours and 10 minutes long, including an interval. It includes references to the death of a child and suicide, and depictions of death.

By arrangement with ORiGIN™ Theatrical on behalf of Samuel French Ltd, A Concord Theatricals Company.

The taking of pictures or video is prohibited except during the curtain call. Silence all noise-emitting devices.

All aboard the last word in locomotive luxury.

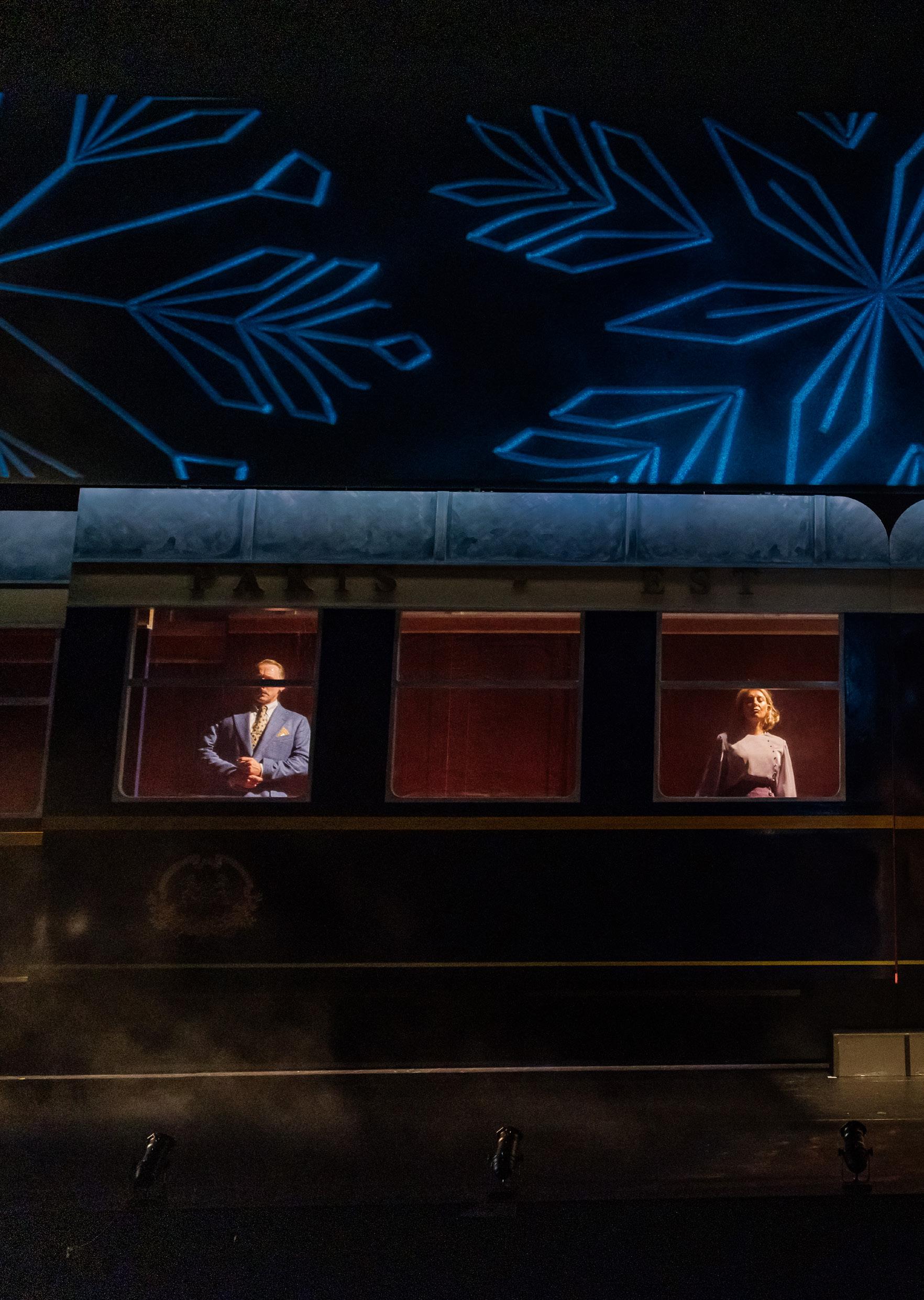

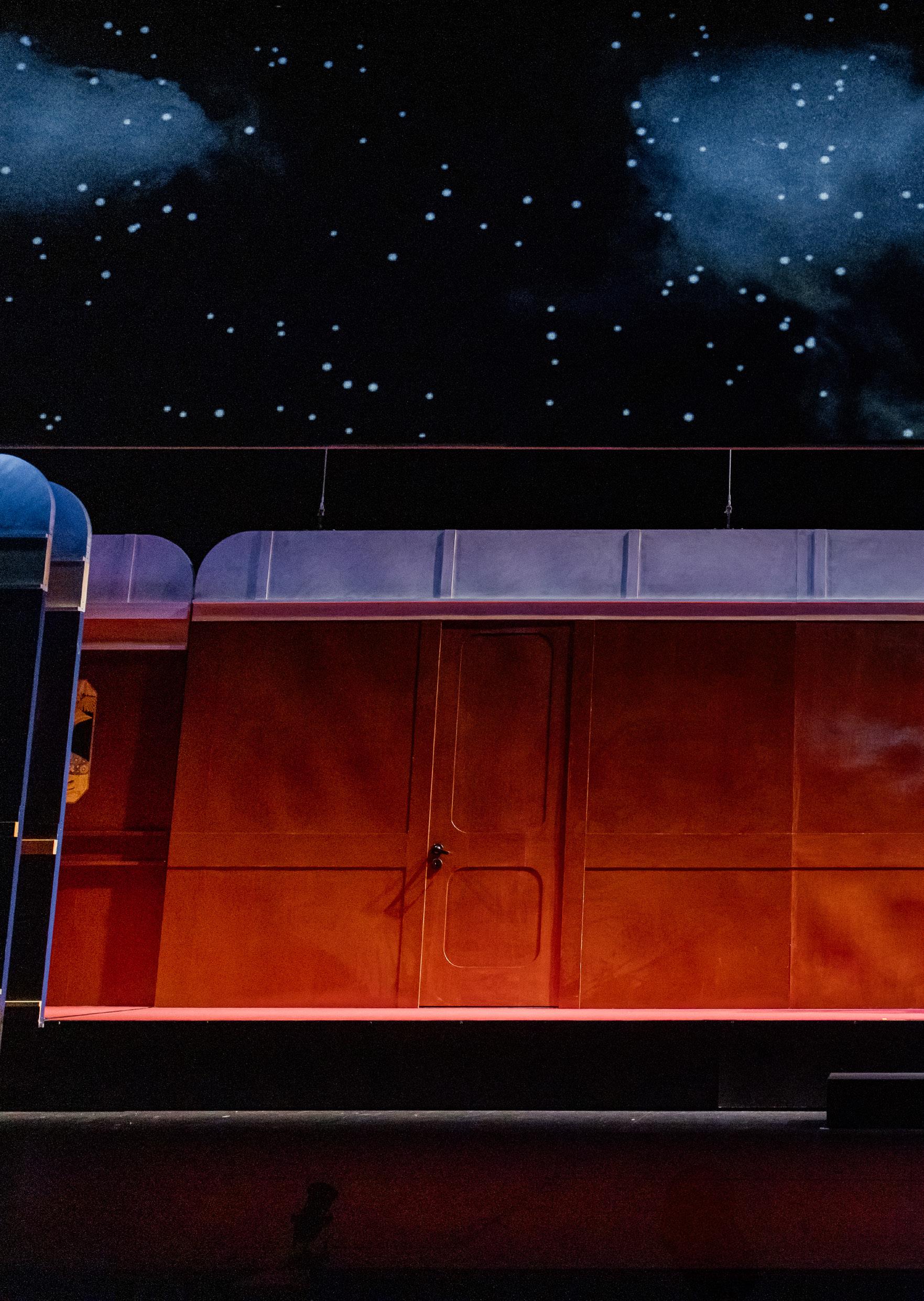

In this lush production, created by director Shane Bosher and his outstanding design team of Elizabeth Whiting, John Verryt, Sean Lynch, Harley Campbell and Paul McLaney, we are swept up in the glamour and sumptuous upholstery of 1934.

Bringing this classic from Dame Agatha Christie to the stage has been a great deal of fun for us all. This is a brilliant ’whodunnit’, with a moral dilemma and a load of laughs. Our Poirot, Cameron Rhodes, leads a stellar cast of New Zealand’s most fabulous actors.

Sit back and watch the snow-covered European countryside whisk by as we hurtle into the night, certain to encounter murder, mystery and mayhem.

P.S. Don’t reveal what happens for people yet to see the show: no spoilers!

Jonathan Bielski Artistic Director & CEO

Winter. 1934.

Hercule Poirot, the famous Belgian detective, is in Istanbul after solving an ’unfortunate’ murder case when he receives a telegram from Scotland Yard begging him to return home.

Despite the train being fully booked, his friend, Monsieur Bouc arranges for Poirot to travel on the Orient Express, the most luxurious train in the world...

One murder, eight suspects and a wild ride that’s about to go off the rails.

Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express continues to surprise readers with one of literature’s most famous endings. The novel drew inspiration from two main sources: Christie’s love of train travel and the Lindbergh kidnapping case.

Christie first traveled on the Orient Express in 1928 to Iraq, where she later met her husband Max. The romance of the train and their meeting merged in her mind, though a honeymoon journey on the same train was marred by bed bugs.

In 1931, Christie wrote to Max describing her fellow passengers in unflattering terms — the genesis for her cast of characters. She used subsequent journeys to verify technical details, ensuring complete accuracy in her plot.

The 1932 kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s child provided the second major influence. Christie incorporated elements from this sensational case, including a servant’s suicide (transformed into a nursemaid jumping from a window).

Christie later declared it “probably the best Poirot book.“ The novel’s structure methodically exposes the mystery’s mechanics through episodic interviews with deliberately archetypal suspects.

Published in January 1934 in the UK and a month later in the US (as Murder in the Calais Coach), the story centers on the death of innocence — both literally and figuratively — creating a timeless mystery that continues to captivate new generations.

The most famous train in the world once travelled from the glittering lights of Paris, France, to the mosques and bazaars of Istanbul, Turkey. Shuttling Europe’s rich and famous across borders in comfort and style, the luxurious train quickly became a hotbed of intrigue, espionage, excess and adventure.

The train’s original restaurant car was run by famous French chefs, serving lobster, foie gras and fine wines at a level rivalling Paris’ top restaurants.

Some of the luxury compartments had private baths – unheard of for trains at the time!

Being halted by snow is based on a real-life incident in 1929 when the train was trapped by heavy snowfall for five days near Çerkezköy, Turkey. This true event likely inspired Christie’s setting for the novel.

The murder in the novel is loosely based on the Lindbergh baby kidnapping of 1932, one of the most infamous crimes of the time.

The Orient Express was the first train to serve ice.

The train travelled through the Simplon Tunnel. This 12-mile rail tunnel beneath the Alps was once the longest in the world, unlocking fast rail links between Northern and Southern Europe. Nazis tried to blow it up in 1945 but were thwarted by Italian resistance.

Becoming known as The ’Spies’ Express’, The train was famous for carrying kings, diplomats and spies, including Lawrence of Arabia and Mata Hari.

In operation between 1919 and 1962, the train survived two wars and heralded the flood of modern tourism that dominates Europe today.

Polinski Pass is a fictional location invented by Agatha Christie for dramatic effect. In the novel, it’s somewhere in Yugoslavia (modern day Serbia or Croatia).

In 1923, a prime minister was assassinated on

In 2023, a fully restored, 17-car Express was unveiled, bringing of travel with new luxury journeys.

How do we situate this production within theatre history? What tradition of theatre style or genre does it belong to? It’s an interesting question, given that Agatha Christie was not primarily a playwright and her best known adaptations have occurred on TV or cinema screens. Writer Ken Ludwig’s adaptation of this Agatha Christie story, then, is partly a celebration of an adored narrative formula that already lives in the collective memory of the audience. The creative team are well aware that, for most audiences, the violence and thrills on Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express are cushioned by familiarity, nostalgia, and the knowledge that we are headed towards a resolution as inevitably as a train pulling into a station. In the world of Agatha Christie, if you keep your wits — and your morals — everything will be okay. Even something as grim and unexpected as murder can be taken apart like a steam engine and put back together through careful reasoning.

As director Shane Bosher says, “That’s what people are really hungry for: entertainment and escape and being taken out of the complexities of their daily lives, when we’re doing so much doom-scrolling and wondering about the existential crisis.“

We could make the case, then, that Auckland Theatre Company’s production of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express owes a lot to the theatrical tradition of Victorian Melodrama. Melodrama developed in the 19th century in France, thanks to the work by French playwright René de Pixerécourt. Melodrama quickly became a favourite theatrical form around the western world for the next century and particularly took root in Victorian England, where it was bolstered by elaborate new stage technology. Like crime novels, Victorian melodramas relied heavily on stock characters, suspense, thrills, and formulaic plots in which good prevails over evil. They were characterised by:

• Violence, romance, and sentimentality

• Short scenes full of action keeping a fast-paced tempo

• Spectacular settings facilitated by theatre technology

• A focus on sensational incidents over character development

• Musical accompaniment

• Exaggerated acting

• Audience interaction to promote audience engagement

• A clear moral framework

You will find many of these characteristics in Auckland Theatre Company’s production of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (look out for spectacular scene changes, character asides and dramatic music!), but the last bullet point is particularly relevant. In her novels, Agatha Christie tantalises us with glimpses into a dark and violent realm but ultimately presents a world in which no crime is unsolvable. Similarly, melodrama sought to thrill its audience by

showing polite society disrupted by villains perpetrating terrible crimes. Inevitably, order would be restored by the end of the play. Christie, just like her melodramatic forebears, reassures us that the world, though sometimes dark and dangerous, is ultimately tameable.

Furthermore, in their efforts to create a cinematic experience for the audience, the team at Auckland Theatre Company will be using many technological tricks that were popularised in the era of Victorian Melodrama. The counterweight fly system housed in the fly tower at the ASB Waterfront Theatre can swiftly bring large pieces of set in and out of the mise-en-scène. The counterweight system was originally invented at the tail-end of the Victorian era, in part to facilitate the demands of ever more spectacular melodramas. Director Shane Bosher says, “What we’re wanting to do is create an old-school sense of theatrical magic in which the worlds

of the play are created in front of us – and so pictures are taken out of sight and new pictures emerge.“

Also in the melodramatic tradition is the original score by Paul McLaney, supporting the actors to create mood, tension, and surprise. In fact, the “melo-“ in melodrama comes from the word “melody“, highlighting the importance of music to this genre. Nowadays, we are so used to music underscoring performances in film and television

that we consider it normal. Before melodrama, however, it was unusual to score a performance with music unless it was an opera. Cinema, with its fast pace and ability to cut between scenes, adopted many of the features of melodramas, even as they disappeared from the stage. Now, as theatre-makers are looking to create cinematic experiences for their audiences, those same features of melodrama are finding their way back to our stages.

• What technologies are used in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express that would not have been around in the 19th Century? How are they supporting the more traditional theatre technologies?

• Though crime writing owes a lot to melodrama, Agatha Christie had her own unique outlook, especially when it came to female characters. How does Agatha Christie’s narrative subvert melodrama tropes?

With more than 2 billion books published, she is outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare. Her works have been widely adapted and produced across most media platforms around the world, including TV, film, radio, publishing, stage, games and digital.

Wrote over 20 plays, of which the most famous, The Mousetrap, is the longest running play in the world, having debuted in 1952.

Over 120 hours of film and television adaptations.

Prolific writing career spanning five decades, with 66 crime novels, 6 non-crime novels and 150 short stories. Her work includes Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and the genre-defining And Then There Were None.

Created Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, two of the most famous detectives of all time.

Easily translatable, her books have been published in over 100 languages, making her the most translated writer of all time.

Wrote her first mystery novel in 1916 when she was just 26, following a bet with her sister. It was published four years later as The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

Born in Torquay in 1890, Agatha Christie became, and remains, the best-selling novelist of all time. She was an extraordinary woman with a remarkable mind.

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born on 15 September 1890 in Torquay, in the south west of England, to an English mother and an American father. She taught herself to read at five years old, and began writing her own poems from a young age. Her education was a combination of informal tutoring at home (mainly by her parents) and then being sent to teaching establishments in Paris where she became an accomplished opera singer and pianist. By the age of 18 she was amusing herself with writing short stories – some of which were published in much revised form in the 1930s.

She spent a three month “coming out season“ in Cairo which resulted in various marriage proposals, and then in 1912 she met Archie Christie, a qualified aviator who had applied to join the Royal Flying Corps. They married on Christmas Eve 1914,

with Archie returning to the war in France on Boxing Day. Agatha became a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment of the Red Cross Hospital in Torquay, and when the hospital opened a dispensary, she accepted an offer to work there and completed the examination of the Society of Apothecaries. This sparked a lifelong interest in the use of poisons, which made a huge contribution to her first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles. The murderer’s use of poison was so well described that Christie received an unprecedented honour for a writer of fiction – a review in the Pharmaceutical Journal.

She was spurred on to write a detective story by her elder sister Madge, who set her the challenge. As there were Belgian refugees in most parts of the English countryside, Torquay being no exception, Christie thought that a Belgian refugee, perhaps a former great Belgian policeman, would make an excellent detective for her first novel. Hercule Poirot was born.

By 1919, at the end of the war, Archie had found a job in the City and they had just enough money to rent a flat in London. Later that year Agatha gave birth to their daughter, Rosalind. This was also the year that publisher John Lane contracted Christie to produce five more books. She went on to be one of the first authors Penguin ever published in paperback, with fantastic results.

Following the war, Agatha continued to write and to travel with Archie, including a Grand Tour of the Empire in 1922 during which she learned to surf in South Africa and Hawaii. Agatha and Archie divorced in 1928, and Agatha then fulfilled one of her lifelong ambitions: to travel on the Orient Express to the Middle East. This and future trips are recognised in books such as Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, Murder in Mesopotamia, Appointment With Death and They Came to Baghdad, as well as many short stories.

During a trip to the excavations at Ur in 1930, Agatha met archaeologist Max Mallowan - the man who became her second husband, and who was fourteen years her junior. Their marriage would last forty-six years. Agatha accompanied Max on his annual archaeological expeditions for nearly 30 years. The excursions did nothing to stem the flow of her writing and her book, Come, Tell Me How You Live, published in 1946, wittily describes her early days on digs in Syria with Max.

By 1930, having written several novels and short stories, Agatha had created a new character to act as detective. Miss Jane Marple was an amalgam of several old ladies she used to meet in villages she visited as a child. When she created Miss Marple, Agatha did not expect her to become Poirot’s rival. But with The Murder at the Vicarage, Miss Marple’s first outing in a full-length novel, it appeared she had produced another popular and enduring character.

In 1971, Agatha achieved one of Britain’s highest honours when she was made a Dame of the British Empire. Her last public appearance was at the opening night of the 1974 film version of Murder on the Orient Express, starring Albert Finney as Hercule Poirot. Her verdict? A good adaptation with the minor point that Poirot’s moustaches weren’t luxurious enough.

Agatha died peacefully on 12 January 1976. She is buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Cholsey, near Wallingford.

Agatha Christie Limited (ACL) has been managing the literary and media rights to Agatha Christie’s works around the world since 1955, working with the best talents in film, television, publishing, stage, and on digital platforms to ensure that Christie’s work continues to reach new audiences in innovative ways and to the highest standard. The company is managed by Christie’s great grandson James Prichard.

Ken Ludwig has had six productions on Broadway and eight in London’s West End. His 34 plays and musicals are staged around the world and throughout the United States every night of the year.

His first play, Lend Me a Tenor, won two Tony Awards and was called “one of the classic comedies of the 20th century“ by The Washington Post. Crazy For You is currently running in London’s West End. It was previously on Broadway for five years and in the West End for three, and won the Tony and Olivier Awards for Best Musical.

In addition, Ludwig has won the Edwin Forrest Award for Contributions to the American Theatre, two Laurence Olivier Awards, two Helen Hayes Awards, the Charles MacArthur Award and the Edgar Award for Best Mystery of the Year. His other plays include Moon Over Buffalo, Leading Ladies, Baskerville, Sherwood, Twentieth Century, Dear Jack, Dear Louise, A Fox on the Fairway, A Comedy of Tenors, The Game’s Afoot, Shakespeare in

Hollywood and Murder on the Orient Express. They have starred, among others, Alec Baldwin, Carol Burnett, Kristen Bell, Tony Shaloub, Joan Collins and Henry Goodman. His book How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare, published by Penguin Random House, won the Falstaff Award for Best Shakespeare Book of the Year, and his essays on theatre are published in The Yale Review. He gives the annual Ken Ludwig Playwriting Scholarship at the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, and he served on the Board of Governors for the Folger Shakespeare Library for 10 years. His first opera, Tenor Overboard, opened at the Glimmerglass Festival in July 2022. His most recent world premieres were Lend Me A Soprano and Moriarty, and his newest plays and musicals include Pride and Prejudice Part 2: Napoleon at Pemberley and Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. His plays include commissions from the Agatha Christie Estate, the Royal Shakespeare Company, The Old Globe theatre and the Bristol Old Vic. For more information, visit kenludwig.com

Writing about her work, Agatha Christie talked about the austerity and stern discipline that goes into making a detective plot: “it is the kind of writing that does not permit loose or slipshod thinking“.

Emboldened by a sense of play and adventure, our company has spent much of this rehearsal period unpacking the intricacies and idiosyncrasies of Agatha’s complex puzzle of a plot. We’ve had to activate every little grey cell of our brains to determine how this tale of lies, deception and humanity really works. Such is the craft of the finest mystery writer of all time.

There’s something deeply satisfying about her signature formula: a mystery is solved: baddies are brought to justice; and order is restored. But, at the heart of this locked-room mystery is a deeply human question. When the systems set up to protect us don’t, what are we to do? Who holds the right to see justice served? And how? It’s a knotty moral issue that both Agatha and her adaptor Ken Ludwig have interrogated with rigour.

This gig has been an exciting and challenging journey. Ludwig’s adaptation sets up the Orient Express itself as a character in

the play: the most opulent mode of transport taking us to multiple destinations. The actors are required to walk a tightrope between wild comedy and searing drama, integrating complex dialects, nuanced character arcs, historical etiquette and razor-sharp dialogue. (It really is daredevil stuff.) We’ve built costumes rich in period detail, found about a million props, created a filmic score and figured out how to stage some how-thehell-do-I-do-this moments of theatre. It’s been a resource-hungry undertaking. The ensemble gathered by Auckland Theatre Company to

tell this story has embraced the ask with extraordinary dedication, an unwavering pursuit of excellence and limitless creativity.

Thanks to Jonathan, Anna, Kathryn and the wider Auckland Theatre Company whānau for this fabulous ride. I’m beyond grateful.

Bon voyage.

“Entertainment is not a dirty word. We’re centering entertainment with this production.“ This is how Director Shane Bosher prepared his team for the work ahead of them, as he presented his vision to the cast and designers on the first day of rehearsals. In a time where gloomy thoughts are never more than a thumb-swipe away, Auckland Theatre Company’s Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express seeks to provide an experience that, much like the historical train itself, is lush, richly ornamented, and provides a temporary escape from contemporary concerns.

However, while the audience experience of pure entertainment should be easeful and comforting, it poses a unique challenge to the team of performers, designers and directors at Auckland Theatre Company. That’s because, in 2025,

the aesthetics of entertainment are dictated by screens. When we seek the warm glow of escape, we turn to our TV’s, laptops or phones. And, of course, if you’re looking specifically for Agatha Christie, you can readily find her on your device. Few authors have been so frequently adapted for the screen; there are over 30 film adaptations alone!

One of Bosher’s solutions to this challenge is to try and bring the language of cinema to the stage. He says, “The audience’s relationship with murder mystery is informed by film and television, and how [the genre] is treated in those forms.“

Think of an on-screen murdermystery: title-cards, close-ups on suspects, moody voice-overs, flashbacks, close-ups on murder weapons, “Dun-dun-duuuun!“ Says Bosher, “So some of the moments

“What we then go into is effectively a memory play“

- Shane Bosher, Director

in this production will be informed by that; by us creating a theatrical version of, for example, a close-up or the highlighting of a suspect or a clue.“

An example of this design approach is the mobility of John Verryt’s set, which can move even when actors are on it, allowing for sequences that mimic the tracking or panning of a camera. “For example,“ explains Bosher, “there’s a scene whereby a door is broken down and reveals a dead body. In our iteration, we’re using the corridor wall which, as three men barge against it, will fly out to reveal a very quickly changed actor.“

Working with such a design requires the performers to work almost like dancers, with each change requiring special choreography. Bosher adds, “A great challenge is having to plot

and figure out where everybody’s quick changes, exits and entrances are, which is usually something we’d work out in rehearsal but with this it’s built into the design.“

The lighting design also takes inspiration from the world of detective cinema, in particular the sub-genre of film noir. Lighting designer, Sean Lynch, explains: “The idea is the juxtaposition between something that is quite soft and lovely looking like [the train’s] dining cars and corridor, with something that’s much more film noir, black and white, sharp edges – and those will build as the tension mounts.“

Finally, sound design is crucial in creating an immersive experience for audiences used to headphones or the surround-sound systems of modern cinemas. “When that train moves, you want to feel, ’Oh my god, there’s

a train about to hit us,’ so you want to feel the full weight of the sound system,“ says sound designer Paul McLaney. As for the score, “we want a foot in the modern camp as well as paying homage to when and where it was written, so it’s not a period piece in that regard. I played with the idea of taking some of the sound design elements, like the moving train, and using the rhythms of that in the original score.“

However, it isn’t enough simply to import the aesthetics of cinema onto the stage. To achieve a feeling of cohesion between the fiction and the design, there must be some dramatic justification coming from inside the narrative. Bosher finds this justification in the character of Poirot himself, who appears on stage to present the mystery of the Orient Express as a recollection. “What we then go into is effectively a memory play,“ says Bosher, “and so we’re

going to find physical articulations of Poirot observing, stepping outside of the action, as well as participating inside of it.“

Here, Bosher is referencing a term popularised by Tennessee Williams in The Glass Menagerie. A “memory play“ is constructed from the memory of one of the play’s characters, usually the protagonist and narrator, and therefore has dramatic license to depart from reality; to take lived events and reshuffle, refocus, and reframe them. So, in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, the aesthetics of cinema become the language of Poirot’s memory. As Tom Wingfield, the narrator of The Glass Menagerie explains to the audience in the opening scene: “The play is memory. Being a memory play, it is dimly lighted, it is sentimental, it is not realistic. In memory, everything seems to happen to music.“

Using the Note from the Director (page 24) and the information about the director’s vision (page 26)and the following pre-reading activities to identify quotes, ideas and themes that you could explore and unpack in a revision and in a report construction context. The resource you will need access to for this activity is a Know, Want to Know, Learned Chart: KWL chart (reference: NCEA Literacy Planning Resources)

• Your topic is “Unpacking Shane Bosher’s vision“

• Fill out the ’know’ section of the chart. What do you as an audience member already know about what the director was trying to communicate from the way Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express was brought to life on stage? You can include what you learnt at the post-show Q&A.

• Note down things that you ’want to know’ in the next section. Discuss this with a peer or small group. What felt cinematic about the way this production was staged? How did this evoke a sense of nostalgia and entertainment? What themes, motifs, symbols stood out to you that you would like supporting quotes or ideas for in order to unpack these?

• Using the information from both sections of the pack:

• Circle ideas that you want to explore further as a class

• Highlight quotes that might support an exam answer or be included in your report

• Underline ideas that you would like your teacher to unpack with you

• Share what you have circled, highlighted and underlined with the rest of your class and with your teacher. Discuss and make notes as a class that you can access later.

• On your own; from what you have circled, highlighted and underlined - fill out the “Learned“ section of the chart.

Extension: You may want to take these notes, class discussions and ideas to do further reading and research. You can incorporate your own thoughts, responses and perspective in the way you respond in your exam or in the portfolio you construct.

Divide into four groups, with a big bit of craft paper each. Each group will take a different prompt to use in conjunction with the information compiled in this pack. Discuss what you think Bosher intended to communicate through his directing choices. You could also refer to anything you discussed in the previous activities as well, building on this whākaaro.

Prompts:

• Research material: Explore the research material provided. Think of examples where this is brought to life on stage through design, directing or acting choices.

• In the rehearsal room: what ideas do you think were explored in the rehearsal room and how does this connect to what you saw on stage.

• The big themes and intentions: identify the themes or intentions that Bosher had for the piece or chose to highlight through design or directorial choices.

• Style and flair: can you identify a specific style or aesthetic in the way the performance was pulled together. What do you think Bosher intended to communicate through these choices?

You will have 10 minutes to discuss and annotate around the prompt you are given as a group. Then you will rotate around the different prompts, spending 5 minutes at each, discussing and adding your own ideas. Once you are back at your original brainstorm prompt collate the ideas into bullet points and share these back to the class for discussion. Make sure you take photos of all the evidence you produce during this activity to reference during your revision or when compiling your portfolio later in the year.

by Ken Ludwig

About four years ago our family went on vacation in England, and during the London portion of the trip we went to the theatre and saw The Mousetrap by Agatha Christie. As you may know, The Mousetrap is the longest-running play in history. When we saw it, it had been running for 56 years (be still my heart) and it’s still running today as I write this.

As I watched the play unfold that night and saw the joy that it gave to our entire family, I resolved to try and write a mystery of my own. However, I knew, even then, that I wouldn’t have a chance of writing a good one until I figured out the allure of mysteries on the stage, and how and why the great ones entertain us so powerfully.

I started by reading every good mystery play I could lay my hands on. (Note: the phrase “mystery play“ can also refer to one of the succession of religious plays written from the 10th to the 16th centuries, illustrating Bible stories and performed by craft guilds. However, these rarely involved strychnine in the soup or eccentric lady detectives in pork pie hats and are not the mysteries referred to in this essay.) What I learnt from all my reading is that the greatest mystery plays written in the past 100 years have certain elements in common

and, by recognising these elements, I was able to understand more deeply the genre I was trying to tackle. Here is a summary of some of the lessons I learnt from my foray into the literature of mysteries.

1. THE GREATEST MYSTERY PLAYS ARE PLOTTED METICULOUSLY. They’re not character studies of a freewheeling nature; that’s not their territory. Think of the three great Agatha Christie stage mysteries: The Mousetrap, Witness for the Prosecution and And Then There Were None. Each one is an absolute model of architectural plotting.

When we speak of plot, it’s worth remembering the definition of plot offered by E. M. Forster in his book Aspects of the Novel. He illustrates the difference between story and plot as follows:

“The king died and then the queen died“ is a story. “The king died and then the queen died of grief“ is a plot. The time sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.“ This is a plot with a mystery in it, a form capable of high development.

In other words, a plot requires causality. It’s not just “and then and then and then“. Great thrillers sometimes take this form, but great mysteries do not. In a mystery, one event must lead logically to the next. Events are caused by other events. A mystery play that lacks a good plot in this sense –that is not well plotted architecturally – is never a very good one.

I recently came across a longlost essay written in the 1930s by Agatha Christie herself, reprinted in the English publication The Guardian Review. In it, Christie confirms the need for tight architectural plotting in a mystery. She says, “I think the austerity and stern discipline that goes to making a ’tight’ detective plot is good for one’s thought processes. It is the kind of writing that does not permit loose or slipshod thinking. It all has to dovetail, to fit in as part of a carefully constructed whole.“

2. THE PLOTS OF GREAT MYSTERY PLAYS ARE RELENTLESSLY LINEAR. Mysteries take us on a ride, starting at the beginning and driving straight through to the end. Like roller coasters, the best mysteries may twist and turn, climb and plunge, but they’re always headed straight forward and zoom on to the finish.

Because the best mystery plays are so linear, there is rarely time for subplots. Everything usually stays on track and contributes to the main story. Think of Deathtrap by Ira Levin. This story about a writer of mystery plays who plans and executes a real murder, grabs us from the first minute and never lets go. Interestingly, it’s not really a whodunit so much as a whydunit – at least for the first half.

Equally compelling in the same way is Sleuth by Anthony Shaffer, about a man revenging his wife’s infidelity: I’ve seen this one described as a whodunwhat – which reminds us that mysteries don’t need to be formulaic, as they’re sometimes described. On the contrary, originality thrives in the world of mystery, be it in the basic plot, the setting of the story, the point of view, and, certainly, in the final twist.

But the one thing the best mystery plays have in common is that there are no superfluous subplots, even for purposes of theme. Great mysteries drive straight onward, staying on track from beginning to end.

Of course, mysteries sometimes contain red herrings: developments that make us believe that someone other than the culprit committed the crime. But, in the best mysteries, the red herrings are woven into the

forward motion of the play. There are loads of red herrings, for example, in The Mousetrap. Indeed, they make up the bulk of the play. The play begins by telling us that a gruesome murder was recently committed, thus laying out the exposition. It then spends most of the rest of the time introducing us to suspect after suspect until the real killer is finally revealed. Christie uses the same technique in her mystery novel Murder on the Orient Express. And, in both cases, she adds a terrific unforeseen twist at the end.

When I started to write my own mystery play, The Game’s Afoot; or Holmes for the Holidays, I came up with a mantra for myself based on all my prior mystery reading.

Just as President Clinton put a note above his desk that said, “It’s the economy, stupid“, I put a note above my own desk that said, “Relentlessly Entertaining“. I decided that the best way to write a mystery for the stage was to make the piece as relentlessly entertaining as I possibly could – another way of saying that the forward propulsion of the piece should never flag.

3. THE GREATEST MYSTERY PLAYS, LIKE THE GREATEST PLAYS OF ANY KIND, SOMEHOW, ALMOST MAGICALLY, HAVE RESONANCES TO OTHER, DEEPER LAYERS OF MEANING. Take the greatest mystery play ever written Hamlet. It begins with the line “Who’s there?“ and it spends the rest of the night exploring that question. Who’s there? Who am I? Who is the ghost? Who is Claudius? And in the midst of these questions, it manages to be (if it’s possible to see it objectively any more) an edge-ofthe-seat mystery-thriller where the

victim’s son tries to figure out whether to trust a ghost who tells him to kill his own uncle in revenge for the brutal murder of his father.

As Hamlet above all others reminds us, mysteries speak to something central to us all. We try to find out who the killer is just the way we question other, deeper questions of identity. We want answers to vital questions that can make the world more rational and sensible because answers give us peace of mind.

4. MYSTERIES, BY THEIR VERY NATURE, CONTAIN CERTAIN RECURRING THEMES.

These usually include questions about death, about justice and about appearance versus reality. Let’s start with death. Has there ever been a really successful stage mystery that doesn’t have a dead body in it? If there has been, I don’t know of it. In some stage mysteries, the death is far in the past –think of Angel Street (retitled Gaslight for the movies) by Patrick Hamilton, in which the murder occurred years before the opening of the play. By contrast, in Dial M for Murder, the murder doesn’t occur until well into the second scene of the play. Similarly, in Sleuth and Deathtrap, the first half of each play is spent plotting the malefaction. But, whether the death is remote or recent, onstage or off, death of some kind usually plays a part.

Sometimes, the death is morally ambiguous, which raises questions about justice. Should the culprit be punished if the victim is a predator on the community? Hamlet raises this question squarely. Is Hamlet morally wrong for murdering Claudius if Claudius in fact murdered Hamlet’s father in cold blood?

I raise this question myself in The Game’s Afoot; or Holmes for the Holidays. It’s hardly the central question of the play, but I’ve spoken with audience members who find the issue of justice to be one of the most interesting parts of the whole proceeding. If the culprit who is finally identified killed a character who was hateful to the whole society, is that culprit blameworthy or worthy of praise? And should that kind of culprit be punished, either by society or by the law? The answers to these questions are never clear-cut, nor should they be. But it’s interesting to remember that we certainly root for Prince Hamlet every step of the way. What about appearance versus reality? In one sense, all drama almost automatically raises this dichotomy. Actors play characters in the play; and while we’re meant to be invested in the characters who embody the story, we also realise that we’re sitting in a darkened room watching actors who have been hired to play parts. What is the appearance and what is the reality? Mystery plays always take this question one step further. Many of the characters, and certainly the culprit, are disguising their true identities for the sake of some kind of escape, be it from real life or from the hangman. Disguise is central to mysteries, just as it’s central to our own lives. Do we want anyone to know who we really are? How do we hide our true identities? What happens when our true identities are revealed? These questions are central to all stage mysteries, from Hamlet to The 39 Steps. And this is one of the reasons that we find mysteries so endlessly fascinating. Mysteries are journeys trying to answer the question of who we really are.

5. FINALLY, WHAT WE’RE REALLY SEEKING WHEN WE LOOK FOR ANSWERS IN A MYSTERY IS A SENSE OF ORDER.

In The Game’s Afoot; or Holmes for the Holidays, I have the inspector in the play, Inspector Goring, say to the protagonist, William Gillette (the actor who played Sherlock Holmes on stage for more than 30 years): “Order from chaos. Order from chaos. It’s what I do.“

And that’s what mysteries do. They fit the pieces together. First, all the disparate elements of the story are thrown up in the air by the murder or another corrupting event. Then, miraculously, all those elements fall back to earth and fit together again, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, into a social order that society recognises and approves.

We as humans seem to crave that sense of order. We find it satisfying and it gives us peace. It seems to me that it’s somehow related to the puzzles that many of us like to solve on a day-to-day basis: like crosswords and Sudokus. Solving those puzzles and filling in all the space in an orderly manner gives us a sense of reassurance and closure.

Every mystery play I can think of – from the earliest examples of the genre, like Sherlock Holmes by William Gillette, which premiered in 1899, to more recent examples, like The 39 Steps by Patrick Barlow, which premiered in 2005 – has an ending where good triumphs over evil and society rights itself after a period of discord. In a sense, that’s the very definition of a mystery. Order from chaos. It’s what a mystery does.

Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express has rich source material, lends itself to natural theatricality, and examples of it being reimagined can be found in popular culture. Information has been compiled in this pack to help you think about the wider context of the performance.

Collecting information: In small groups, read the following sections; ’A background to Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express’, ’The Melodrama Formula’, ’Agatha

Christie - a Potted Biography’, and ’Why Do Mysteries Grab Us?’ by Ken Ludwig’. Use the following table to collate information that you think will be helpful as wider context in an exam answer or in your portfolio:

This could be:

• Quotes

• Information that was directly recreated onstage (make sure you link it to examples of moments on stage)

• Points that you found interesting and would like to discuss further

With the information that you have collated as a group, do the following activity for homework (this could be a presentation, essay or voice recording):

• Think of an important moment in the performance and describe it in specific detail; what the actors were doing, details about technology, motifs, symbols, etc

• Discuss how this moment was inspired by Christie’s original text and how Ludwig has brought it to life for the stage

• Discuss how this moment was influenced by Victorian Melodrama, giving specific examples

• Tie your thoughts together by discussing how Shane Bosher was influenced by the historical and wider context, in his vision for the performance

In small groups write a short response or create a short presentation around either of the following questions, drawing on the thinking and playing you have been doing so far as a class.

Be creative with your presentation; it could be physical, in role, TED talk style or a seminar. Ensure that the whole group’s responses are included.

“What was your initial reaction to the performance of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express? How did it make you feel as a member of the audience? What have you been thinking about and feeling since?“

“What impact did the sense of suspense and mystery in the performance have on you as an audience member? How did it make you feel in the moment? What connections can you make to examples of this story in popular culture?“

Thinking about what Ludwig says about why mysteries grab us and drawing on the cinematic nature of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, work in small groups, to storyboard a short mystery that is inspired by what you have read so far and seen. Once you have an idea of your short scene, bring it to life. You could incorporate the following:

• Include freeze frames or tableaux directly from your storyboards

• Creative stage configuration, such as:

• traverse, in the round, thrust etc.

• Break the fourth wall and have characters speak directly to audience as if being interviewed

• Use an episodic structure, as Christie does in her novel

• Aim to build tension with a bold ending; a cliff hanger or a shocking plot twist

• Features drawn from Victorian Melodrama, with archetypal characters

Once you have performed for your peers, discuss as a class how these scenes could be extended, how the choice of staging was impactful, and why mysteries draw the audience in.

The incomparable Hercule Poirot has entertained readers for a full century since his debut in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, written during World War I and published in 1920.

The 1930s produced a bumper crop of Poirot novels as Christie entered what many consider the golden age of detective fiction. His career finally concluded in 1975 with Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case.

Poirot has appeared in nearly every artistic medium, from graphic novels to computer games and animations.

As described in Styles: “Poirot was an extraordinary looking little man. He was hardly more than five feet, four inches, but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military.“ His mysterious limp in early books soon disappeared.

Christie revised the first novel’s ending at publishers’ request, replacing a courtroom scene with the now-famous gathering of suspects for the detective’s reveal— establishing a template for her future works.

She deliberately made Poirot “very neat – very orderly,“ wondering if this was because she herself was “a wildly untidy person.“ Across the books, details about Poirot are sometimes inconsistent, with Christie herself needing to verify facts with her agent.

His idiosyncrasies caused many to underestimate his deductive abilities. Christie chose “Hercule“ as a deliberately grand name for her small detective, finding inspiration in Belgian refugees near her home, though she admitted, “I didn’t really know any.“

Making him a retired police officer was “a mistake,“

Christie later conceded, as Poirot would have been over 100 in later cases.

Poirot famously disdained tangible evidence, preferring to rely on “the little grey cells.“ Christie described her mysteries as “halfway between a crossword puzzle and a hunt in which you can pursue the trail sitting comfortably at home in your armchair.“

Her willingness to challenge detective fiction conventions made Christie a sophisticated, critically acclaimed and much loved writer.

When you are thinking about an actor’s performance to write about in an exam or portfolio setting, you will want to build a comprehensive profile of how they used their body, voice, movement and use of space. Details about motivation, ideas or symbols they highlighted and moments of subtext that pointed to themes or relationship dynamics, are also useful. You will want to link these details to specific moments in the performance, describing what was happening on stage and linking to big ideas and wider context.

These activities will enable you to build a kētē of information about characters you found compelling or who were integral to the narrative.

Each character within Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express has their own narrative arc, relationships and tensions. It is important to understand why the character is behaving the way they are, what has happened for them prior to the play beginning that makes them who they are and what they are communicating to the audience.

Divide the class into small groups, enough groups to focus on each of the characters. Use the following framework, include notes, sketches and imagery and save in a digital space:

• Character name, age, physical attributes

• Purpose in the narrative being explored on stage

• Where has this character been prior to boarding the Orient Express? Why is this relevant to the story being told?

• Reflect on the type of language used by the character. How does this impact the way you understand the character?

• Describe a moment that was important to that characters story on stage

• Explain how the actor used techniques; voice, body, movement and space in that moment to bring the character to life

• Pull out quotes and important ideas from the education pack, including interviews and add them to this profile

• Add ideas from your own research, including from the original source material

• Add quotes from the performance that you feel are important to this character, demonstrate motivation or tension or from moments that drove the story forward.

• Sketch and annotate the costume the actor wore as this character, how did this impact their use of body, movement and space. How this contributes to the audience’s understanding of the character’s narrative arc.

Each of the characters in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is under the watchful and suspicious eye of Poirot and also the audience. This activity allows you to explore how the actor used drama techniques; voice, body, movement and space to demonstrate innocence, guilt or how they attempt to divert attention away from themselves. (You can collect information and discuss in a way that suits you; in writing, voice notes, a presentation, images, sketches, etc.)

• Choose a character that you found particularly compelling

• Choose a moment where the actor is demonstrating innocence, guilt or trying to divert attention from themselves. Describe this moment in specific detail - what was happening on stage?

• Discuss how the actor used voice, body, movement and space to hint at/demonstrate this innocence, guilt or diverting attention from themselves

• Choose a quote from the performance that captures this innocence, guilt or diversion

• Sketch the moment and add annotations - you could do this as a storyboard capturing the moment across multiple frames or one detailed image

• Physical extension activity: Recreate this moment with a group of your peers. Create three freeze frames that capture a moment of suspicion. Focus on bringing to life expressive facials, use of proximity and body angle/ position to highlight mood, tension and focus.

Bring the characters of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient

Express to life in your classroom: All of the characters in the play come under suspicion and ultimately the details of the murder are revealed at the end of the performance, BUT could it have gone another way? Divide into groups with enough

actors to cover Poirot and each of the characters under suspicion, to create an alternative ending, with an alternative murderer, through a devising process.

• Your scene doesn’t have to be long and should focus on using drama conventions and building the drama elements of mood, focus and tension

• Focus on using drama techniques to bring the characters to life; give accents a go, experiment with posture, facial expression and play with proximity and use of tableaux to create strong images on stage

• After your performance justify to the audience why this character could have been the murderer

Poirot is an iconic character, represented in short stories, novels, on stage, and in film. This series of activities will enable you to do a close reading of the information provided in this education pack, explore how Cameron Rhodes brought him to life in this production, and also to play with creating your own interesting characters.

• Read Hercule Poirot: The Quintessential Detective (page 40), then:

• Circle ideas that you want to explore further as a class

• Highlight quotes that might support an exam answer or be included in your report

• Underline ideas that you would like your teacher to unpack with you

• Share what you have underlined with the rest of the class, and with your teacher’s support, unpack your ideas and how they connect to what you saw on stage

• Thinking about what Agatha Christie intended for the character and how he is represented, discuss how Cameron Rhodes bought Poirot to life on stage:

• How did he use his voice, body and movement to bring the character to life?

• How did the Director’s instructions and Rhodes’ use of space and proximity to other characters help to communicate the story being told?

• How did the costumes and use of props contribute to the sense of character and how did this impact the way Rhodes carried himself and his movement across the space? How was costume design drawn from how Christie had created the character?

• Choose a moment that you found compelling in the performance that highlighted Rhodes’ use of voice, body, movement and space. Respond to the following prompt: How did Rhodes create focus, build tension OR create atmosphere?

• Include references from your close reading, your brainstorm as a class and the notes you have made about techniques and costume/ props

• You can include imagery, sketches, record as a voice note or write a response

Agatha Christie noted that in creating Poirot “some characters are suggested to you by strangers you’ve never spoken to – you see someone at a picnic and make up stories about them like a child.“ Use the following instructions to create your own iconic characters in a small groups;

• Individually (perhaps as a homework task) think about someone (must be a stranger) you might have observed on your way to school, at the train station/ bus stop, in the mall or a public setting like the beach/on a walk, etc.

• Write down details about them, how they speak, move, stand, etc

• Come up with a posture for them that you can show your group

• Give them an interesting or mysterious name

• Share the above with your group and brainstorm the following:

• An iconic location where these characters might meet or be

• A short narrative for this meeting; including a bit of mystery or intrigue

• A cliffhanger you could end on

• Have fun with the story, be creative and over the top. You could reference some of the features noted in the Victorian Melodrama section of this education pack

• Use a devising process to bring this short scene to life, focus on your use of drama conventions and elements

• Present your scene to the class and discuss what was effective and how the scenes could be extended.

by Elizabeth

As a class have a discussion around the following prompt questions, making extensive notes on the white board with your teacher:

Why do you think Agatha Christie based this murder mystery on a train? What does it do to the audience to watch a story where the action takes place in a confined space? What did it make you think and feel as you watched the performance?

Divide into small groups, with each group covering a different designer and complete the following:

• Read the designers notes

• Discuss and note down what their design inspiration was?

• Discuss and note down why you think they made these choices

• Discuss how these choices connected to the directors intentions for the performance and how they realised this

• Note down quotes you think might be helpful in a portfolio or in an exam answer.

Junior students: share what you have discussed with the rest of the class

Senior students: Upload your group’s notes to a shared digital space so that the class can access the information when they are thinking about constructing their portfolio or revising for the exam.

Split the class into groups, each group should cover a different setting within the performance. As a group, use the table structure below to compile notes:

• Make notes about the set, sound, lighting, props, and special effects. Provide lots of detail about materials, colours, etc. and use technical language such as

gobo, cool versus warm lighting, etc. Your teacher will support you with this.

• Choose a moment that was important to the narrative that happens in this set and outline this in specific detail.

• Sketch the set and add annotations/labels

• Share this back with your peers and save in a digital space where everyone can access the notes.

Notes…

Important Moment:

Sketch:

In a play like Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express costume enhances and heightens the characters for both the audience and the actor. The actor uses their costume, hair and make-up to help them understand the world their character comes from, to drive their use of gesture, their posture and stance, and the way they move across the space. It might also influence little eccentricities that an actor might add as they are developing their character. For the audience, we think about the same things as we watch the performance, with the addition of also considering what might have inspired the designer in the decision making. Use the following activity to explore these ideas.

Divide into groups, with each group focusing on a character each and create a digital or hand made presentation/short portfolio that covers the following:

• Sketches or images pulled from the pack with detailed annotations. The annotations should include; colour palette, materials used, style of clothing and added details (buttons, zips, etc)

• Notes about what inspired the designer(s), including quotes

• Notes on how the costume, hair and make-up design impacted the actor’s use of body, voice, movement and space

• Examples of character eccentricities that could have been inspired by the costume, hair and make-up design

• Extension: how has this character been represented in popular culture and how does this help you understand the character’s purpose in this story? Discuss the similarities to Auckland Theatre Company’s depiction.

“Drama transforms the tangible into the intangible.“

This section of the education pack is designed to support Level One drama students navigating the new Level One external Achievement Standard 91943 - Respond to a drama performance. Unlike the Level Two and Three external standards, which are an exam, you will be constructing a portfolio, over a period of time in class and it will be based around three key aspects;

• Key message of the performance, the use of drama components and your own personal response about how you connected to the performance, capturing the wairua (spirit) of what you watched.

This portfolio will be presented as a slideshow or PowerPoint and can be a mixture of written and audiovisual material - the main question

you should ask yourself as a student is; how do I communicate my ideas, thoughts, and feelings about what I saw, the best? With that in mind, you are encouraged to collect your thoughts, discussions and do your research in a range of formats. Such as voice notes, sketches and annotations, brainstorms, mood boards, recorded physical responses and writing.

Kaiako and ākonga please ensure you read this year’s assessment specifications carefully as you prepare to submit this assessment. You can access the specifications via this link: NZQA Assessment Specifications - Level One

Below are three activities to support you to expand your ideas and support you during the teaching and learning phase of unpacking the performance.

In pairs, small groups, or as a whole class, discuss and brainstorm the following prompts:

• What do you think the playwright was trying to say? Why this story? Why these characters? Why this period of time?

• What do you think the director was trying to communicate through the choices they made? How does this connect with what the playwright has written?

• What do the characters in the performance represent and what do they communicate to the audience?

• What do you think the designers are trying to communicate through their choices? How does this bring the playwright’s ideas to life?

Once you have brainstormed around these questions, you could journal, voice note or record thoughts around the following questions:

• How do you identify the key message of a performance?

• Can there be multiple key messages?

• Think about your interpretation of the performance - what was the key message to you?

• What physical evidence from the performance connects to the key message? This could be a scene, a moment between characters, dialogue, a moment where the use of technology highlighted an idea.

• Describe these examples and sketch them in specific detail.

Drama components are techniques, elements, conventions and technologies. Make sure you have explored this language and terminology with your kaiako/teacher.

Now that you have fleshed out what the key message might be, you need to connect it with the choices that the director, designer and actors have made and how they have used the drama components in combination.

Brainstorm in small groups, or in pairs:

• How an actor used drama techniques in a moment that communicated the key message

• How elements created a sense of mood, atmosphere or tension

• How conventions were used throughout the performance

• How technology enhanced the story being told

In the unpacking on the NCEA website for this standard, this aspect of the assessment is unpacked in detail. Your teacher will support you

in understanding this and guide you to explore, research and develop your ideas.

“The wairua of the performance is experienced as the intangible energetic and emotive qualities that carry the spirit and intention of the play. How the wairua is expressed by the performers provokes a response from the audience and allows them to reflect on the ideas and themes of the play based on their own life experiences and perspectives.“

- 1.4 - Unpacking

• What thoughts, ideas and feelings did the performers provoke in you?

• What have you reflected upon since watching the performance?

• What have you been thinking about (head) and feeling (heart) since?

• What did your gut/sense of intuition communicate to you as you watched the performance?

• What life experiences or perspectives do you bring? What connections did you make?

Drama | NCEA

Level One External Specifications

If you are a Year 12 or 13 student who attended the production of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express you will likely have had your Live Performance exam in mind as you watched the performance. You are encouraged to look at the questions written for Year 11/Level One students in the previous section. With this in mind, the questions below will support you to revise for your exam at the end of the year but will also enrich your thoughts, feelings and ideas about the performance of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express and may expand your own work that you develop in the classroom. You are encouraged to explore the questions both individually and with your peers.

Note: When answering the following question you will want to find and provide physical examples from the production. A physical example is when you describe, with specificity, what is happening on stage at the time. Get down to specific detail, for example, explaining how the actor/ performer is standing or moving, how far away from the audience they are, what is happening with technology, where exactly they are in space, etc. The more detail, the better!

• Describe how an actor who you found interesting or compelling used drama techniques in a specific moment in the performance.

• Describe how two actors used proximity during a moment of tension.

• Discuss how an actor uses drama techniques during a solo moment on stage. What were they aiming to communicate? What did you understand at that moment?

• Explain another actor’s use of drama techniques and how they created a sense of tension within the performance.

• Choose specific moments where you felt the actor used their body, voice, movement, and space in combination to create suspense or a tense atmosphere, thinking about the whodunnit nature of the play

• Discuss why you think tension or suspense was important in this particular performance

• Thinking about the actors and the way they created their characters:

• How did they use techniques to create a sense of time and place?

• How did they use techniques to communicate their history?

• How did an actor use drama techniques to communicate subtext in their performance? Use a specific moment and example to discuss this use of subtext.

• Why was the subtext important when telling this story?

• Discuss what you found compelling about an actor’s use of drama techniques in the performance. Choose a specific moment to focus on.

• Discuss what the character communicated to the audience; how did the actor portray them? Plot their character arc and describe how they use techniques to communicate this.

• Discuss the purpose of the characters:

• What impact do they have on the narrative, as well as the audience and actors’ relationship?

• How does the actor’s use of techniques communicate their purpose in the performance?

• Explore the ensemble of characters as a whole: what purpose do they serve in the narrative?

• Discuss the design choices in the opening or closing moments of the performance. Why were these choices important in setting the scene or closing out the narrative?

• Discuss how technology or design was used during a climatic moment in the performance? What do you think was at stake within the scene?

• What influences do you think the Director/Designer drew on? Use information from this pack and from the forum to support your answer.

• Discuss how Auckland Theatre Company’s realisation of this performance connects to the Agatha Christie source material and how it was influenced by Melodrama Form. Link your ideas to specific moments or examples from the performance.

• How did the way the performance was realised impact the style of delivery of the narrative/story?

• How does the content of the play challenge, excite and serve the audience?

• Why do audiences love a whodunnit narrative?

• Discuss how the director brought the story to life using Drama Components - Elements, Conventions, Techniques and Technologies.

• What do you think Shane Bosher is asking you to think about in the way he has directed Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express?

• How did the acting and staging choices affect you as an audience member?

• What was the impact of the way the design, directorial, and acting choices worked together? Choose a moment that surprised, shocked, or excited you to talk about.

• Discuss why the use of sound and lighting design was integral to this performance? Focus on the mood created by sound choices, use of colour and the shapes created by the angles or composition of lighting.

(NB - make sure you are familiar with what the established Drama Conventions are by discussing this with your teacher)

• Identify a moment in the performance where Drama Conventions were used to create focus, mood or atmosphere:

• Explain how the convention or combination of conventions were used in the performance

• Discuss the impact of the use of the convention or combination of conventions in this moment

• Discuss how meaning was created for you, as an audience member, in this moment

• Discuss how the use of a convention or combination of conventions in a specific moment helped you think about the big ideas and themes of the play.

• Connect this with the original Christie source material.

• Drama Elements and how they draw our attention to themes, motifs and symbols:

• What were the main themes, questions and ideas evident in the performance? Link these themes, questions and ideas to specific moments or examples from the performance.

• How were design and directorial elements (props, setting, AV, costuming, audience positioning and interaction) and the Drama Elements used to build the performance? How did this make you feel as a member of the audience?

• Identify recurring symbols or motifs throughout the performance. Explain why they were important in helping you understand ideas being communicated in Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express?

• How do these themes, symbols, or ideas link to the wider world of the play and what impact does this have on the audience?

• Reference the wider reading from earlier in the pack

• How do these themes, symbols or ideas highlight or link to specific characters?

• Why are these themes, symbols or ideas important to the narrative as a whole?

LINK YOUR IDEAS TO SPECIFIC MOMENTS OR EXAMPLES IN THE PERFORMANCE.

Think about lighting, set, sound, props, costumes, make-up and how this helped bring you into the world of the play.

How was technology used to create the atmosphere in the performance?

• How was technology used to highlight important ideas, themes and symbols in the performance?

• How was contrast and/or focus created or built through technology and why was this important?

• How did the use of technology help to build the tension and mystery of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express?

• How did the use of technology establish a sense of time and place and how did this drive the narrative forward?

• How did technology highlight the different character in the performance?

• Discuss why this was impactful, exciting and/ or how this built a sense of mystery around the character

When you are writing about Set or Costume, you need to be specific about the following details and also sketch what you see. Imagine the person you are writing for has not seen the production and create a vivid image in their mind of what you saw:

• For example: Set/Props

• The size, shape and dimensions of any set pieces or props used

• The materials used, their textures and the colours