“All the contortions we go through just not to be ourselves for a few hours.” -Keith Richards ATLAS | 3

“All the contortions we go through just not to be ourselves for a few hours.” -Keith Richards ATLAS | 3

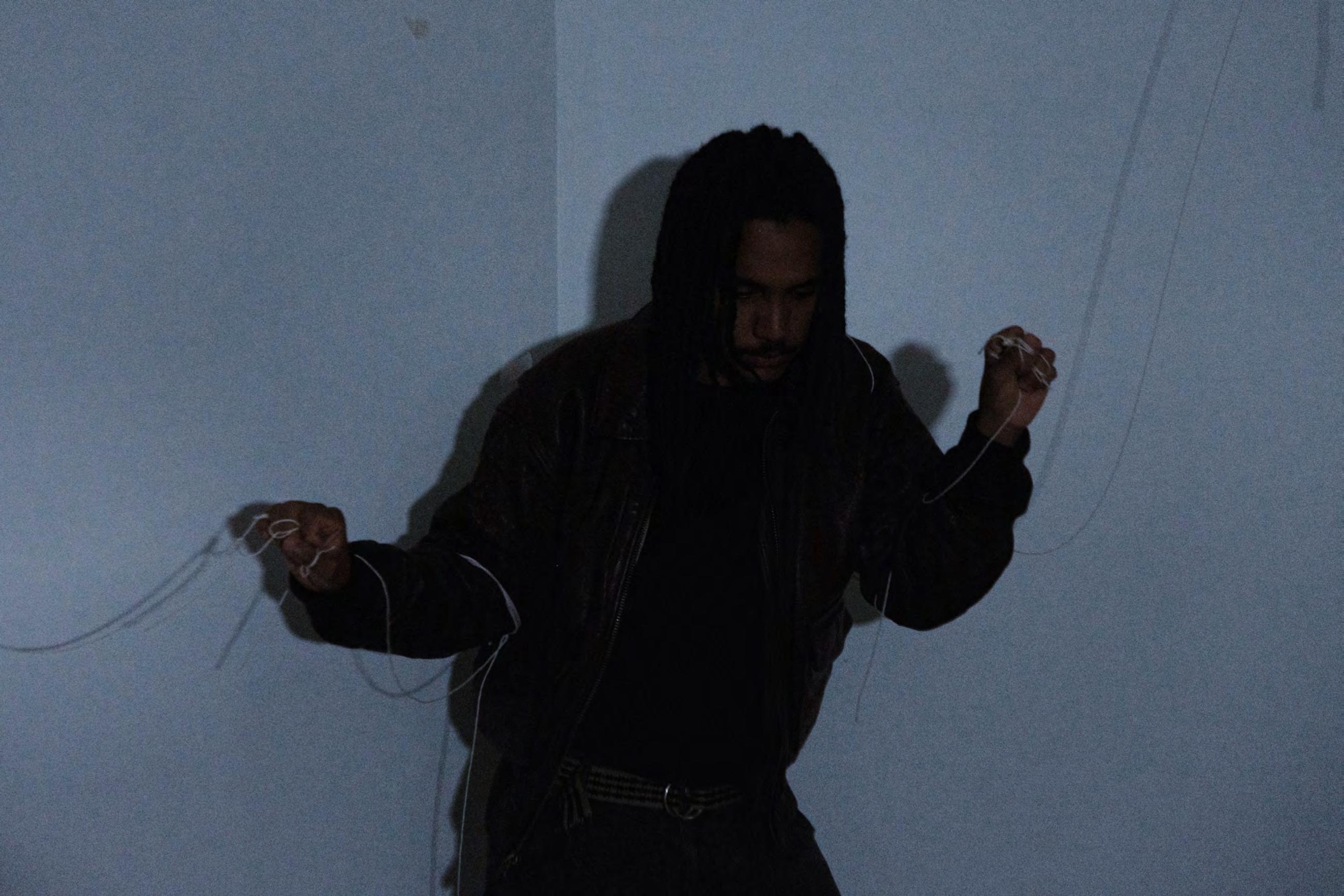

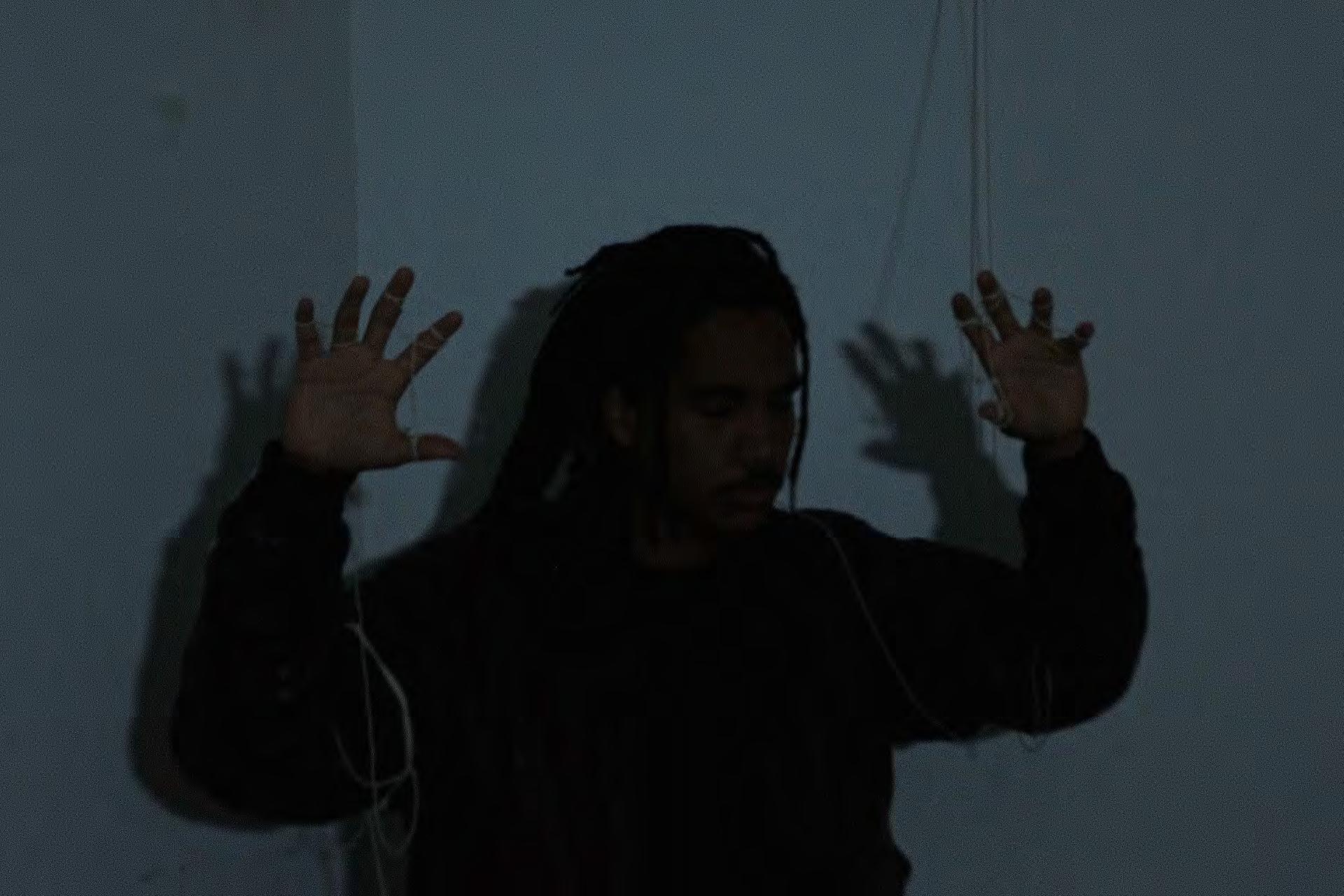

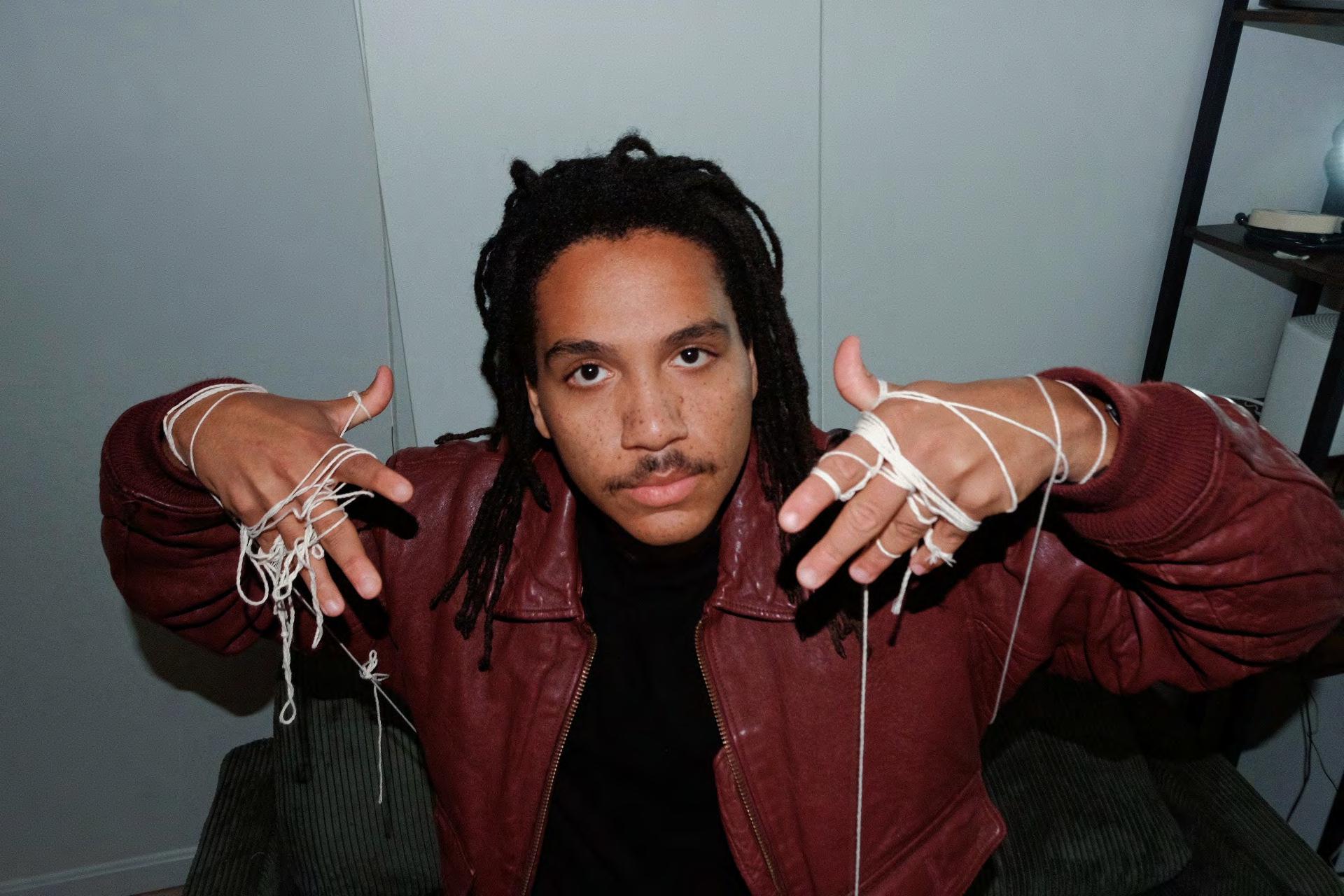

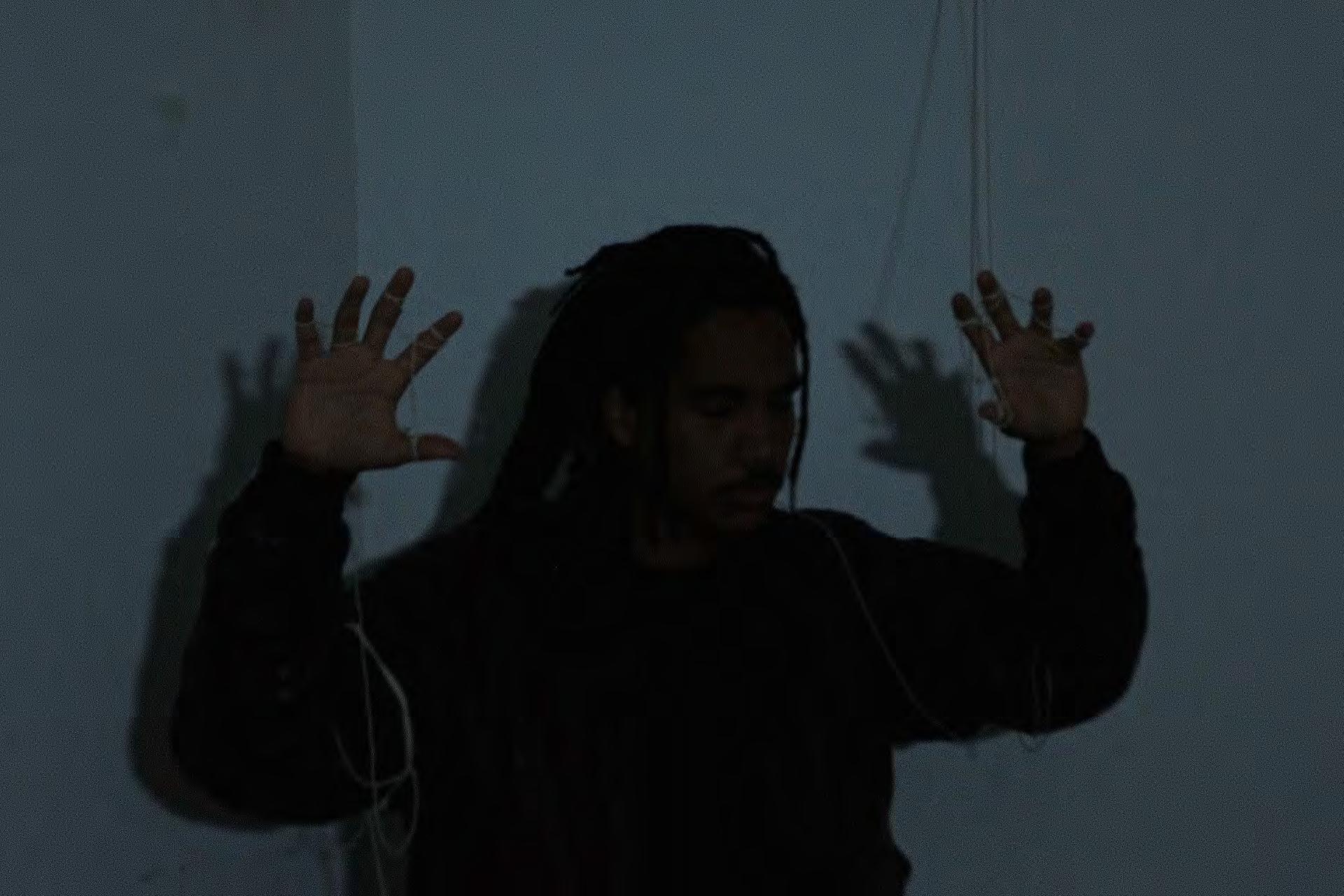

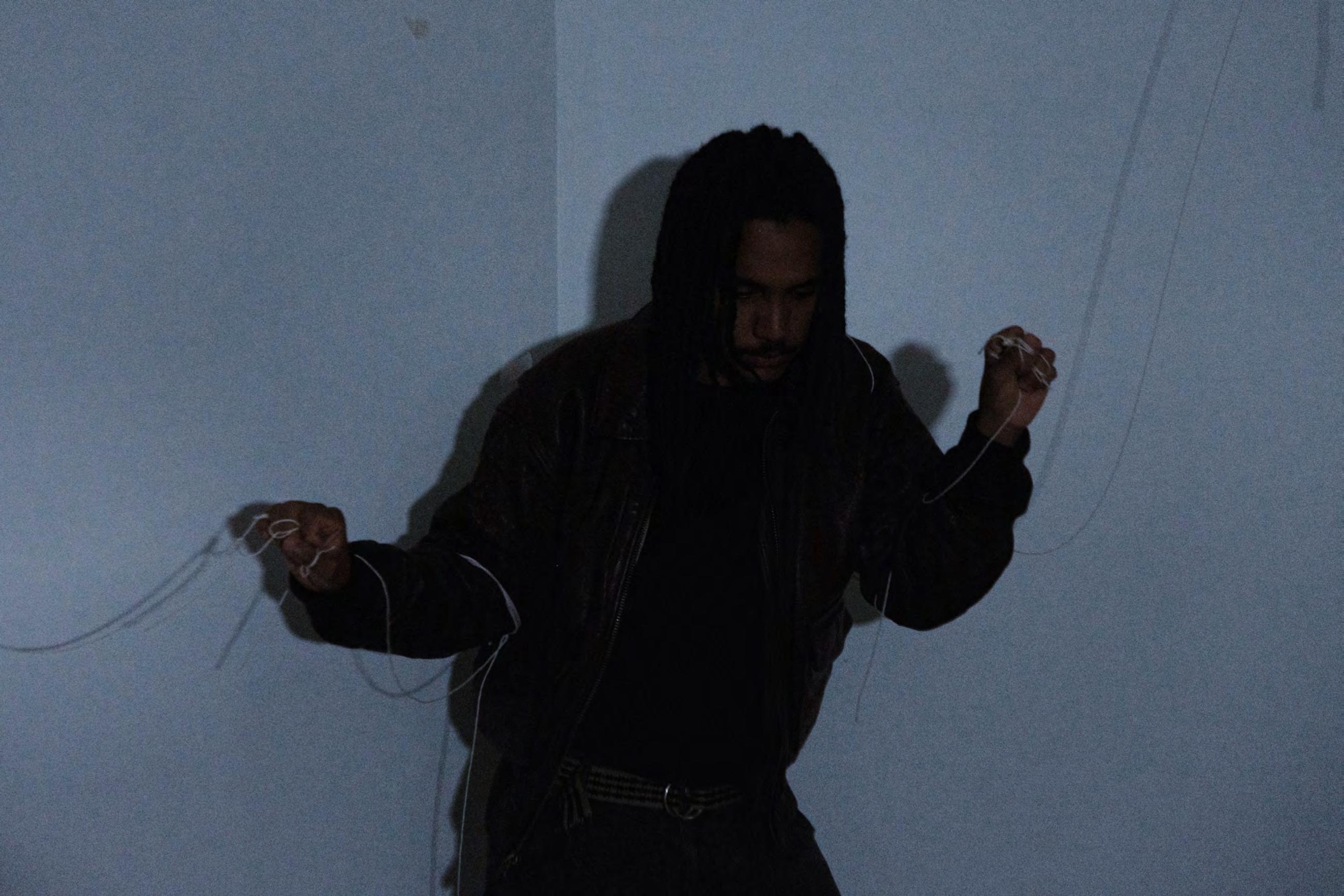

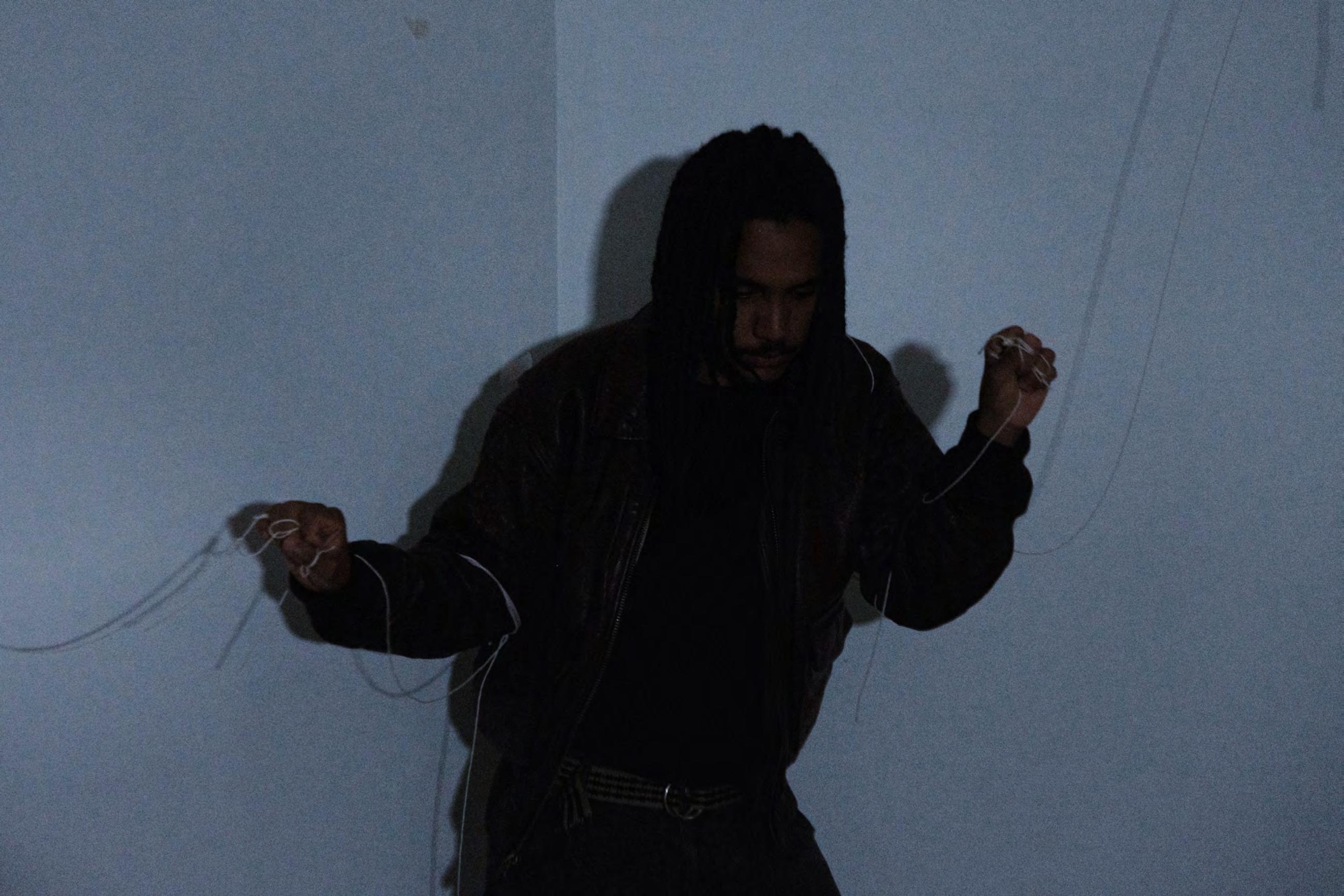

This semester we asked writers and photographers to consider how they contort themselves, the ways in which they bend to different situations, twist and grow. For Atlas, this fall was a semester of contortion. With one of our biggest recruitments of the past few years and many new E-Board members, the magazine itself was shaping into something new.

As first time Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director, there were many learning experiences. Contortion can be a state of confusion, the body and its surroundings lacking clarity and structure. But contortion can also be the experience of untangling oneself, growing into new shapes and forms. We asked many questions this semester and relied on teamwork to reach deadlines and create this magazine. Contortion can be uncomfortable, it asks us to push ourselves. Contortion can also be beautiful, as you are sure to see in this semester’s photoshoots and articles. We want to thank everyone on staff for their patience and dedication to Atlas this semester. We are honored to share your work.

This semester we learned more about what goes into making Atlas — the rounds of edits, the busy design period, the purchase requests on EmConnect. And while it would be nice to think that we will settle into this new contortion, all of these tasks becoming mere muscle memory, we have also learned that contortion does not stagnate. Next semester, we will learn new things, grow in new and unexpected ways. Atlas will continue to contort. We are excited to see it take change, and change again. We are so excited to share what our contortion has produced.

Sydeney & Lily

6 | contortion

Editor-in-Chief

Creative Director

Managing Editors

Sydney Flaherty

Lilian Holland

Sidnie Paisley

Thomas & Lily

Suckow Ziemer

Treasurer Elisa Ligero

Web Director

Jadyn Cicerchia

Photography Director Laith Hintzman

Illustration Director Lauren Wockenfuss

Style Coordinator Audrey Stiefvater

Beauty Director Talia Kahwajian

Style Editor Rowan Wasserman

City Editor Grace Grandprey

Globe Editor Gray Gailey

Arts Editor Sidnie Paisley

Thomas

Wellness Editor Lily Suckow Ziemer

Head Copyeditor Rachel Dickerson

Social Media Director Mia Rodriguez

Head Designer Ugne Kavaliauskaite

Diversity Chair Gray Gailey

ATLAS | 7

Editorial

Lucy Latorre

Rowan Wasserman

Keanna Grigg

Audrey Stiefvater

Vara Giannakopoulos

Alyssa Walker

Jadyn Cicerchia

Harper Pebley

Charlotte Farrar

Ella Sutherland

Lily Suckow Ziemer

Madison Smithwick

Meghan Boucher

Elizabeth Gomez

Sydney Flaherty

Sidnie Paisley Thomas

Jasper Chen

Emma Ross

Brenna Sheets

Matthew Provler

Copy Editors

Rachel Dickerson

Jadyn Cicerchia

Grace Grandprey

Lauren Wockenfuss

Keanna Grigg

Julia Chen

Jasper Chen

Photo

8 | contortion

Virgil Fionn Durkin

Emma Fisher

Keira Alana

Mari Silva

Grace Thayer

Style & Beauty

Mia Rodriguez

Virgil Fionn Durkin

Sophie Corbissero

Audrey Stiefvater

Design

Ugne Kavaliauskaite

Lilian Holland

Ella Sutherland

Audrey Stiefvater

Natalie Alpert

Lauren Mallett

Emma Fisher

Kaitlynn Hungate

Marketing

Mia Rodriguez

Virgil Fionn Durkin

Sophie Corbissero

Audrey Stiefvater

Visual Arts

Lauren Wockenfuss

Natalie Alpert

10 | contortion

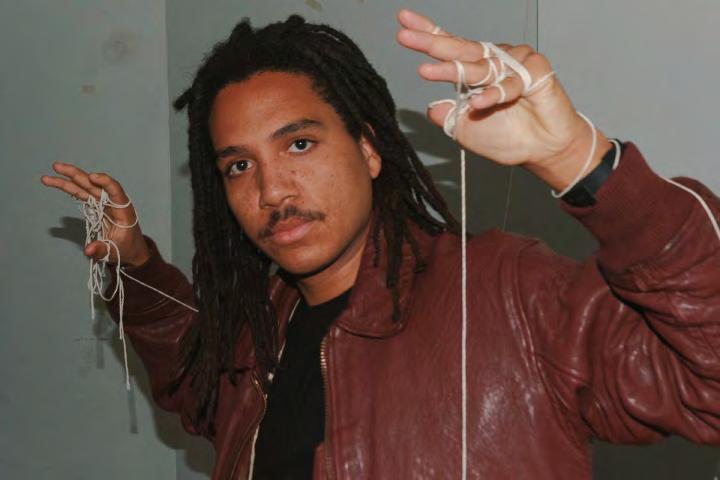

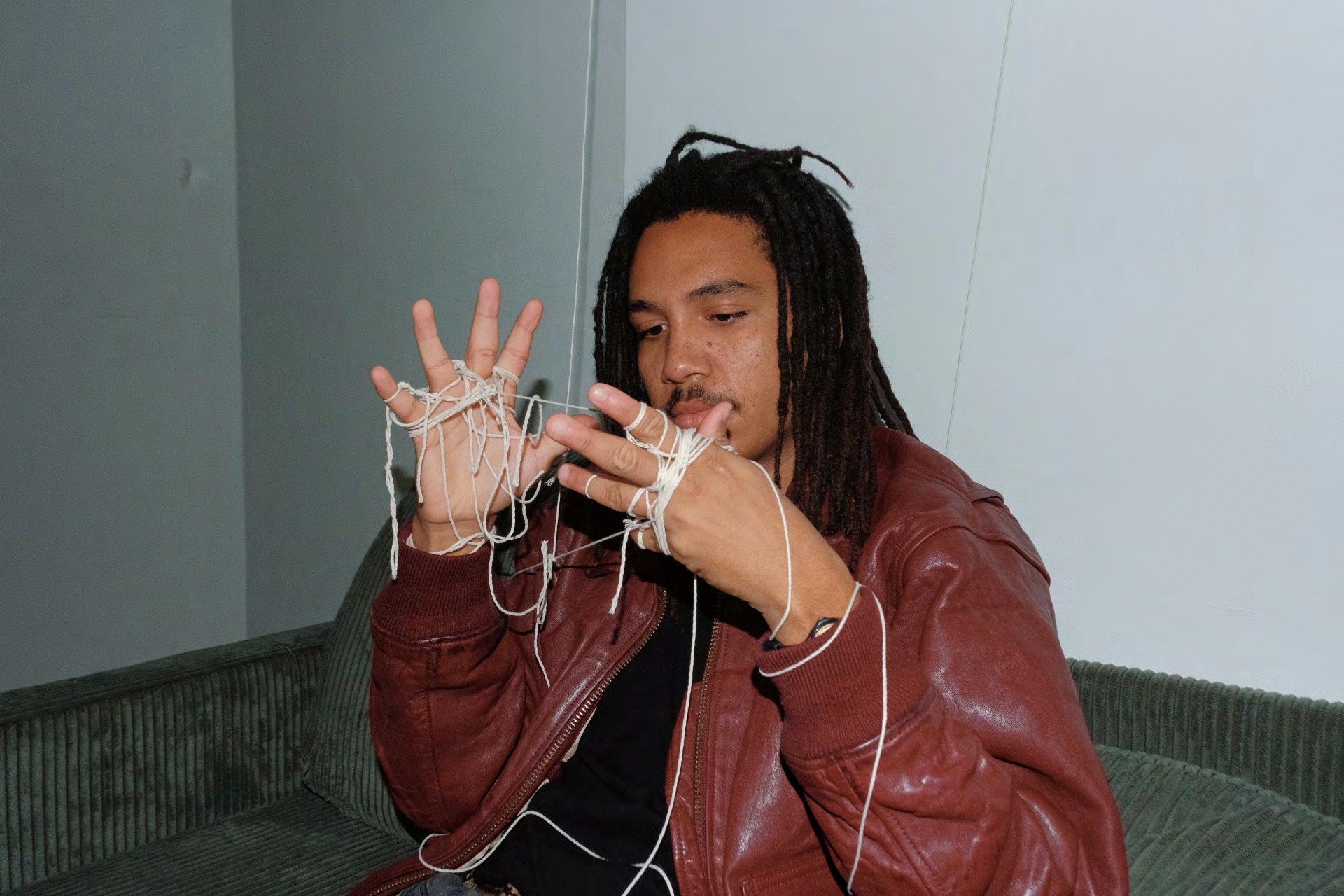

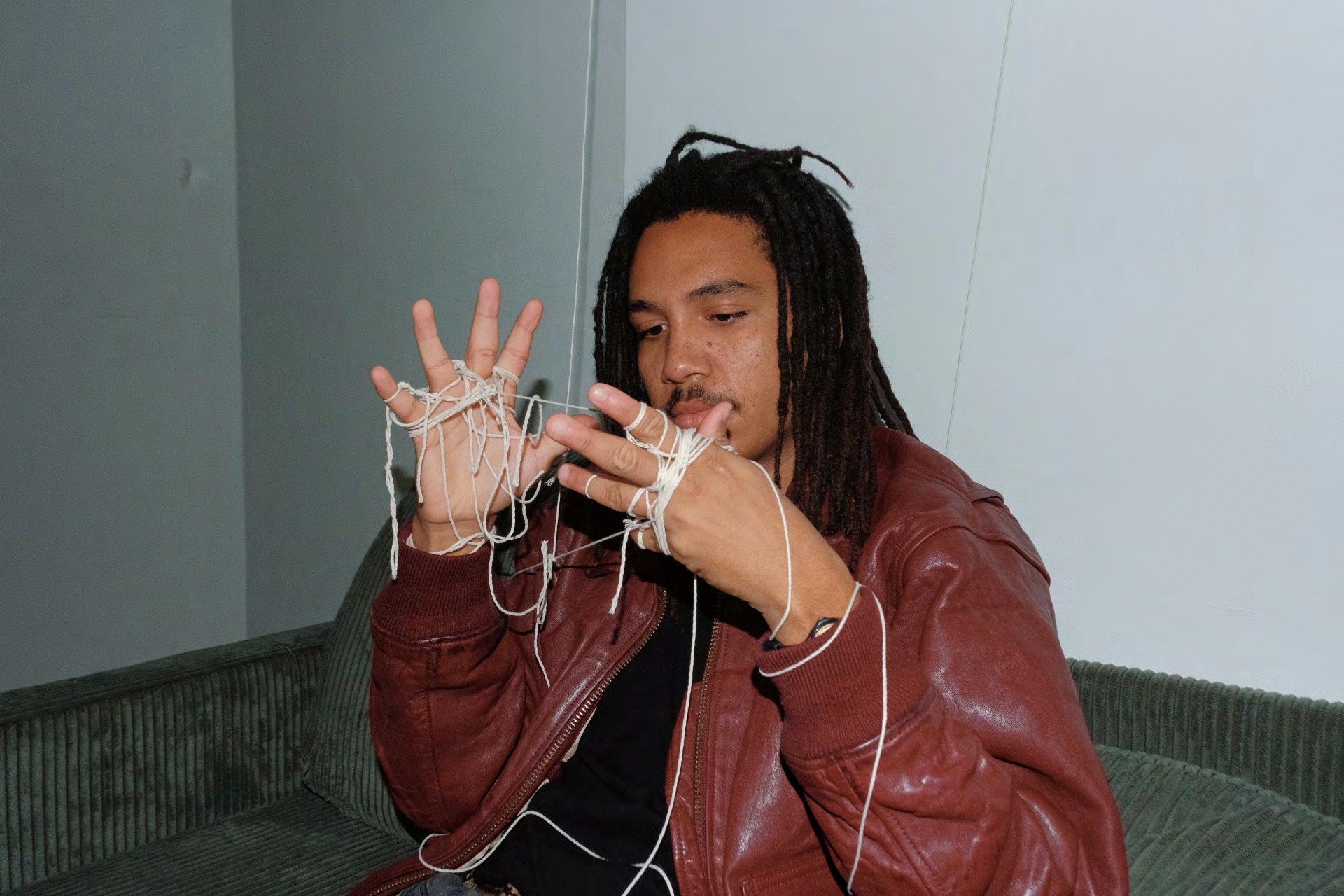

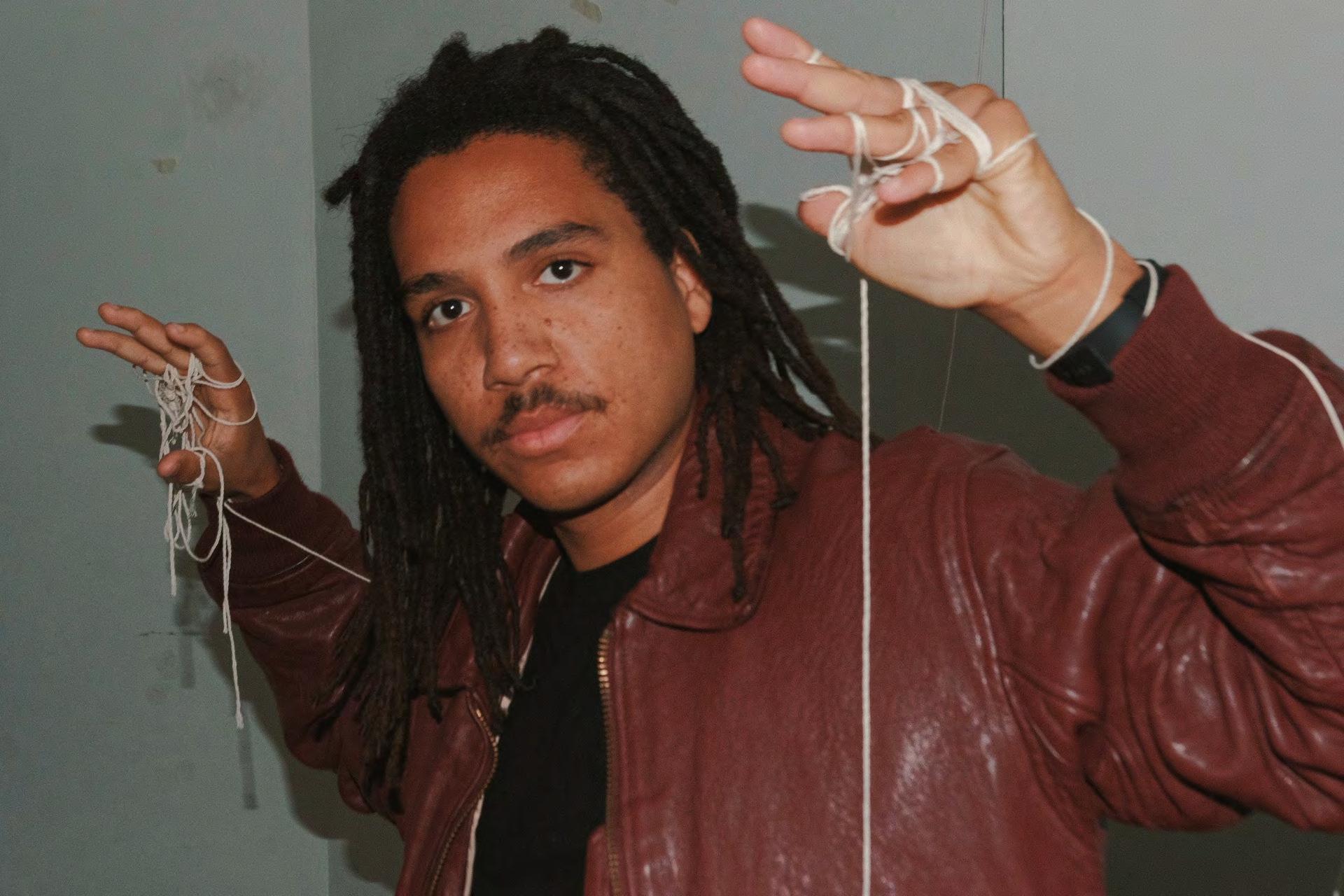

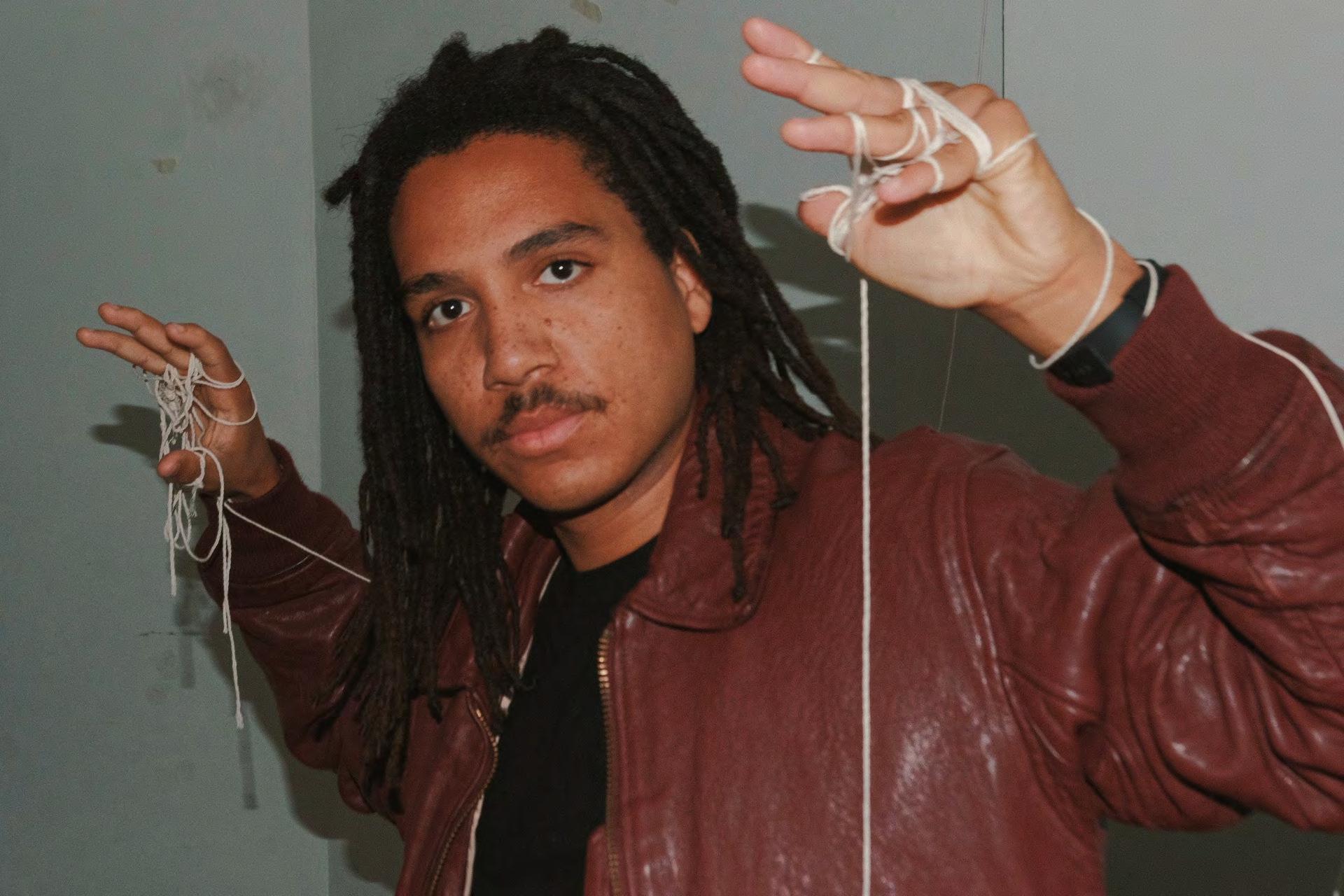

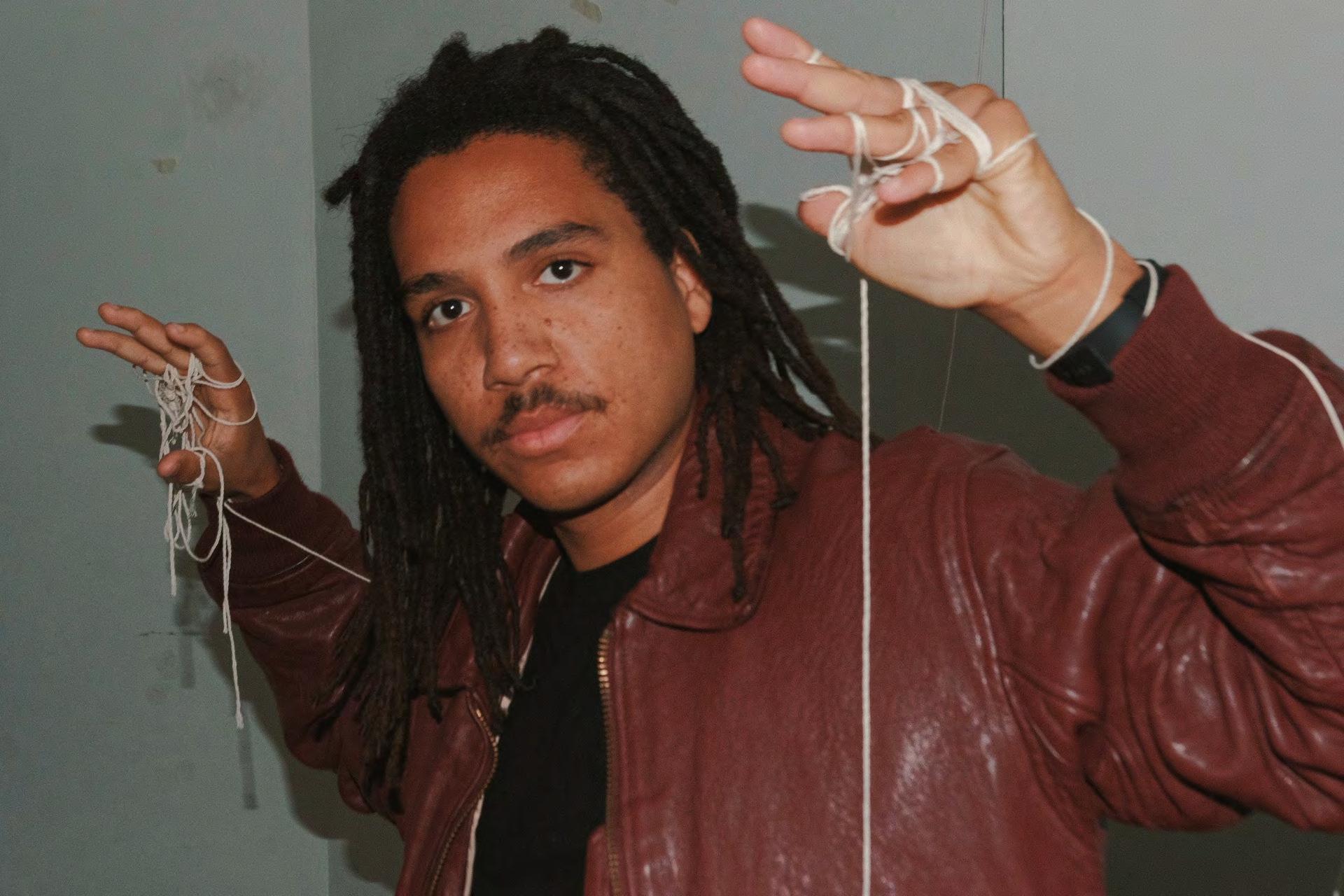

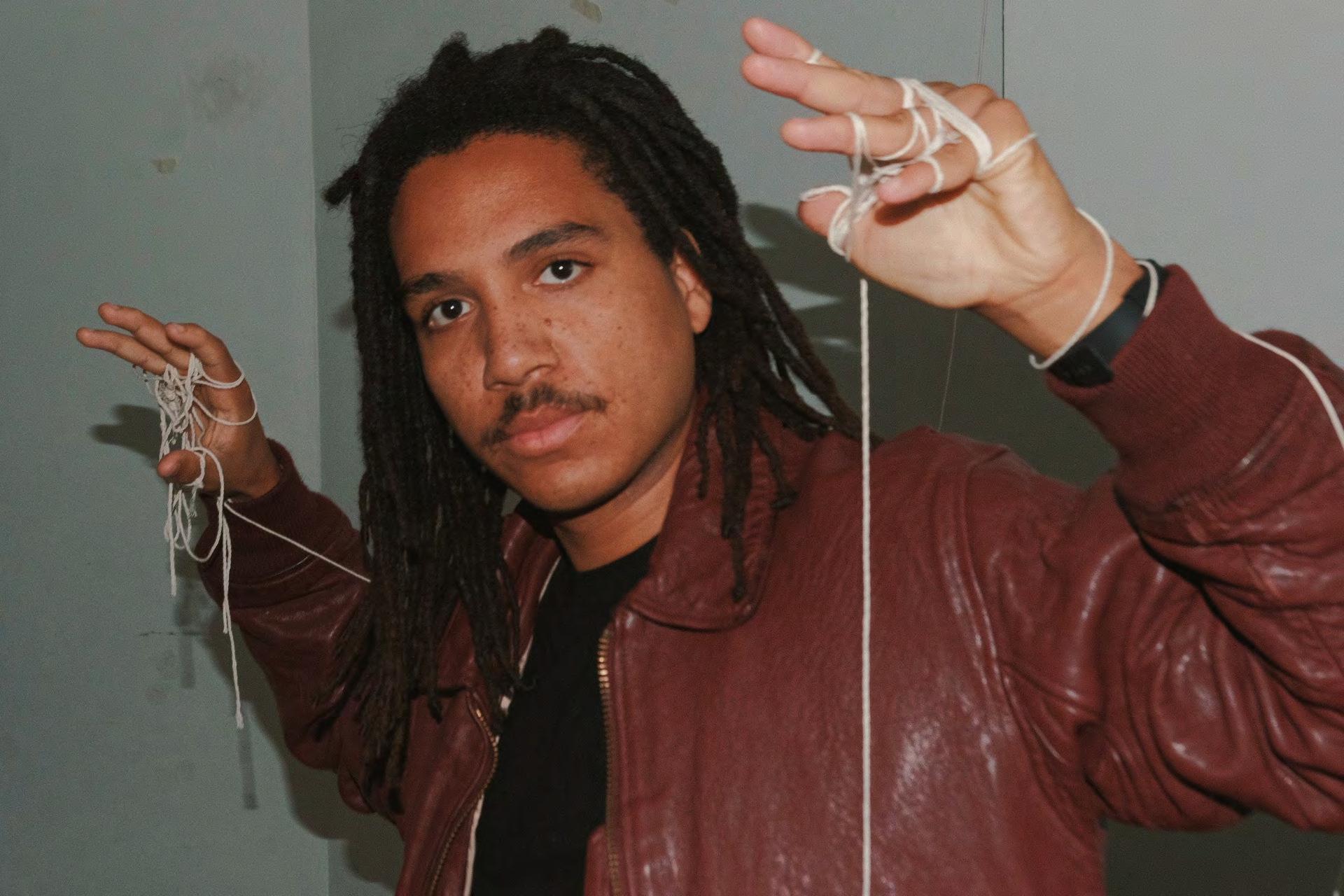

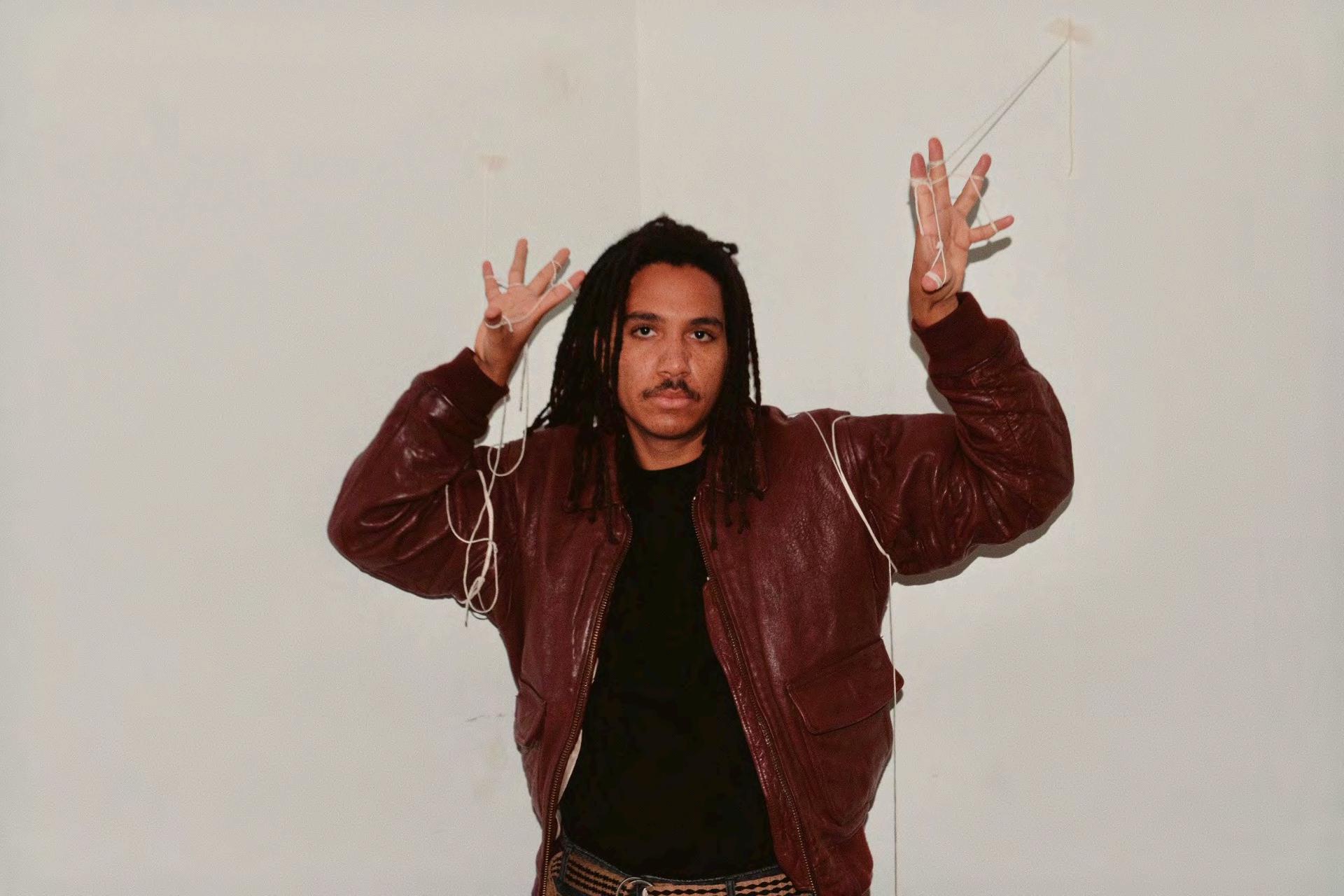

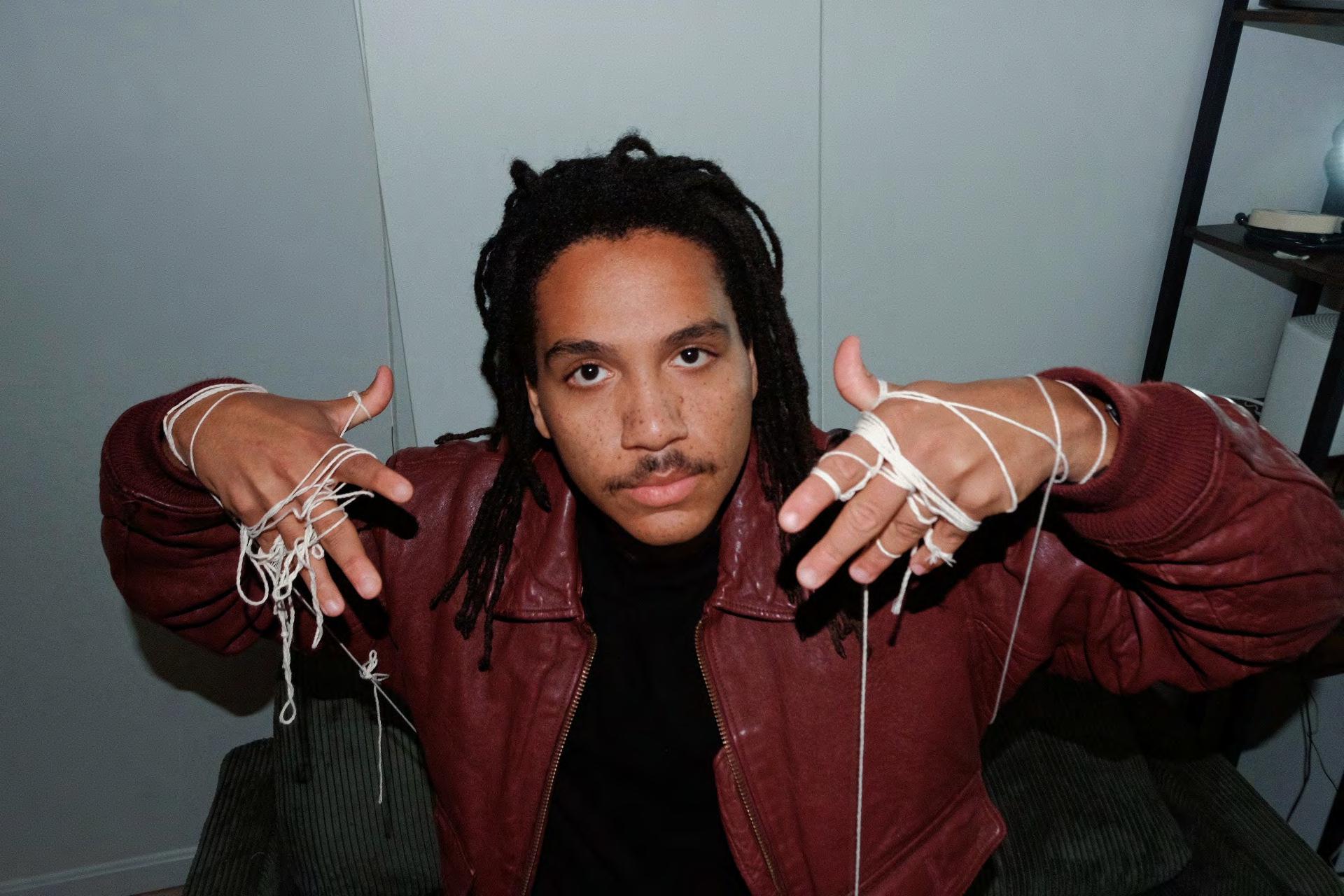

Photographer Kiera

Schuett

Models

Illustrators

& Natalie Alpert

Design Natalie Alpert

ATLAS | 11

By Jasper Chen

About a quarter of the way through Emily St. James’ novel Woodworking, Erica Skyberg paints her nails and counts the people who notice. Erica, a closeted transgender woman and high school English teacher living in a conservative town, has good reason to be nervous.

A few people notice. There’s Abigail, Erica’s openly transgender student and the only person she’s out to; Megan, Abigail’s friend and an enthusiastic ally; and Helen Swee, a progressive political candidate who is about to lose a local election to the incumbent conservative transphobe. And then, oddly enough, there’s Brooke Daniels.

Brooke is a loving mother of two who works with Erica at the community theater. Her family sometimes campaigns for the aforementioned conservative transphobe. Her son, Caleb, is dating Abigail, but she doesn’t know that yet. She’s a traditional, religious, affluent woman who realizes that the high school English teacher has his nails painted.

Brooke suggests that Erica purchase nail polish remover.

Much later, we discover Brooke’s secret: she is a transgender woman who ran away from home, transitioned at a young age, and never told anybody about her gender posttransition. Well, her husband knows, but he refuses to acknowledge her identity and is sworn to secrecy.

Erica and Brooke are two transgender women wearing different costumes. Erica pretends to be a cisgender man, living as Mr. Skyberg until she physically can’t anymore. Brooke pretends to be a cisgender woman. She supports transphobic politicians and scolds Erica over her painted nails. Neither one is telling the truth. Woodworking spends much of its page space dissecting how painful these women’s pretenses are.

Erica’s pretense makes her deeply paranoid, convinced she’s on the verge of being found out. She is intensely aware of how her conservative community would react to the truth: “In a town like Mitchell, South Dakota,” St. James writes, “[Erica] had to disappear before she was spotted” (1). Erica inches out of the closet, only to leap right back in. The situation makes her hopeless. “At a certain point, you’ve invested too much in your life,” she reasons, explaining 12 | contortion

why she should not transition. “It becomes a sunk-cost fallacy” (86). In other words, she’s spent so much time miserably trying to be a man that she might as well stick with it.

On the other hand, Brooke’s pretense leaves her lonely and cruel. She throws away letters from transgender people who mentored her when she was younger. She argues for bathroom bills, saying they “[protect] us…from men who wear costumes and pretend to be women” (182). She is without a single loved one who knows and accepts that she is transgender.

Woodworking switches between the perspectives of Abigail, Erica, and Brooke. The characters speak from different points of view. Erica speaks in the third person. She is separated from herself, a passive observer of her own life. When she finally comes out to her boss, pushing herself so completely out of the closet that she knows she will never return, she begins to speak in the first person. Coming out shifts her narrative to this point of view; in other words, it allows her to become an active participant in the world she inhabits.

Brooke’s chapters are told in the second person. “You will always remember the song playing on the radio when the guy gives you your first hormone pills…You know your name is Brooke before you know you are a woman” (224-225). However, a first-person voice slips into her story. “...I hang out in the subbasement of yourself…and I wait and wait and wait for you to notice me” (245).

Here, St. James literalizes the idea that Brooke is living as a wholly separate person from her true self. The first-person voice represents Brooke as a transgender woman. She is trapped behind Brooke’s false identity, speaking only in short sections before Brooke hides her once more.

The use of changing points of view is bold, but ultimately does not interrupt the flow of the novel. Woodworking uses the narrative device to suggest that Erica and Brooke can find their true selves only by being openly transgender women. This would be a straightforward, easy-to-understand moral were it not for the existence of Abigail.

Abigail is not closeted. Her chapters are always in the first person. Abigail complicates the narrative that a transgender person can fix their life by simply coming out. She is out, she is not-so-proud, and she hates her life. A local politician tries to pass a bathroom bill as soon as she starts attending school in his district. Her parents refuse to accept her, so she lives with her sister. She fantasizes endlessly about the exact scenario that causes Brooke so much grief: “I’ll get my surgeries done and change my name and never, ever tell anybody else again” (15).

The breaking point comes when her boyfriend, Caleb, shows her his college essay. It is about how his girlfriend is transgender, but he bravely loves her anyway. It shares Abigail’s deadname; it talks endlessly about how he is “so inspired” by her “perseverance and beauty” (220).

ATLAS | 13

“Abigail complicates the narrative that a transgender person can fix their life by simply coming out.”

Abigail is open about who she is, but all this means is that people view her through the lens of whatever beliefs they already hold regarding the transgender community. Her gender identity defines her; it turns her into a cardboard cutout in everyone else’s life. To conservative politicians, she is a deviant who threatens the well-being of other girls. To Erica, she is a lifeline who is obligated to listen to her secrets. To Caleb, she is a vaguely “inspiring” person to write about in his essay for Northwestern. After she reads the essay, Caleb tells Abigail he loves her. “You love a character in a story,” she retorts (221).

Abigail is hardly an active participant in her own life, either. Mostly, she is swept around by what other people think of her. When she talks about her life and desires, she sounds uninformed and helpless. “I hadn’t ever really thought about what I want,” she says. “I wanted to be a girl, and then I did that, and a whole bunch of life met me on the other side” (199).

14 | contortion

“Woodworking spends much of its page space dissecting how painful these women’s pretenses are.”

ATLAS | 15

Pretending not to be transgender is a lie. But being openly transgender is not necessarily the truth. All it means is that you must contort yourself in increasingly uncomfortable ways to fit societal standards for what a transgender person should be.

Abigail is plagued by this. Her parents want her to let them call her by her old name. Her boyfriend’s family wants her to be quiet about her identity. Her school wants her to stop talking about how bathroom bills harm transgender students. She loses her personhood in the haze. But Erica and Brooke, who take opposite approaches to Abigail, suffer as well.

Woodworking is about the impossibility of a transgender person living as their true self. They are always forced to conform to someone else’s idea of what they ought to be. There is no way to escape this external pressure.

But, Woodworking suggests, maybe you can lessen internal pressure. Abigail doesn’t have a perfect life. She struggles. She is brash and incautious, and depressed. Still, she is more herself than Erica or Brooke. She cuts off people who misgender her. She loves and is loved as a transgender woman. She lives in the first person.

Woodworking opens with Erica meeting Abigail. Erica, trying desperately to come out to her, asks, “...what do I do…now that I know?” (7). Abigail looks at her, understands what she means, and buys her nail polish.

The novel ends with Abigail spotting another transgender girl being harassed by some guys. She approaches and attempts to comfort her. The other girl “reads [Abigail] the second [she walks] up to her” (342) and smiles.

Maybe that’s the more important message of Woodworking. Transgender people will always face impossible choices as they try to balance being safe with being themselves. But when they are with each other, for brief moments, they can be honest and unafraid of harm.

“That’s all we are, maybe,” Abigail muses, “...people who pick each other out in a crowd and realize that the face of someone you’ve just met can feel like home” (343).

16 | contortion

“All it means is that you must contort yourself in increasingly uncomfortable ways to fit societal standards for what a transgender person should be.”

ATLAS | 17

By Alyssa Walker

“We cast away priceless time in dreams, born of imagination, fed upon illusion, and put to death by reality.” – Judy Garland

If you were to log onto YouTube in 2015, your home page would likely show thumbnails of swollen lips and shot glasses with titles reading “Kylie Jenner Lip Challenge,” often, “Gone Wrong.” At the time, the titular reality TV star had people, primarily younger girls, speculating on how she got her lips so big, since Jenner very much denied any kind of filler.

So the public got creative.

The trend, primarily partaken in by teenagers, involved inserting your lips into a shot glass and sucking in to hopefully recreate Kylie Jenner’s full pout. Instead, the results left users with bruised lips and the chance of having glass shatter all over their faces.

Finally, in May of that same year, Kylie Jenner shocked nobody when she admitted to having temporary lip filler.

Jenner’s lip filler was never the problem; her denial of it was. Gaining her fame from Keeping Up with the Kardashians, a reality show whose primary audience was impressionable teenage girls, turned her into a role model, a beauty standard. Being a teenager herself and admitting during her “confession” that it was her insecurities that led her to fillers, couldn’t she have known how the girls watching her felt? Given societally situated beauty standards, it is only natural, especially during the most self-deprecating years of your life, to want to change, to want to look like the conventionally attractive people on your TV. When you are made to believe that Kylie Jenner’s unnatural looks are natural, sometimes the only viable option is to put lips to shot glass and suck.

18 | contortion

However, Jenner is not entirely to blame.

Beauty standards are a chain, moving from those who run Hollywood to celebrities to consumers. And when you are at the very top, the standards are yours for setting. This is why all the guilt cannot be entirely forced upon Kylie Jenner’s shoulders, as she was just sixteen years old when she began getting filler. She herself was just a link in the chain.

We see the beginning of this chain in movies such as Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, where celebrity Elisabeth Sparkle is fired by her producer because her age is making her less marketable. In response to this, Elisabeth takes The Substance, an injection that allows her to change into Sue, a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of herself. Though this is what societal standards tell Sparkle she wants, she quickly realizes that seeing the world fawn over her “more beautiful” self is devastating to her mental well-being. The overuse/misuse of The Substance also causes eventual physical damage, the sad irony of course being that Sparkle took it to improve her appearance. The Substance leads to grotesque and eventually fatal effects for Sparkle, who dies on her own Hollywood Walk of Fame star. The industry built her up, kicked her out, and killed her.

In other films, we can see how striving for on-screen perfection has real-life consequences. Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 film Black Swan portrays how the main character, Nina, is forced to undergo a severe mental change in order to be the ballerina that her New York City Ballet director wants her to be. To play the role, Natalie Portman was made to lose 20 pounds, restricting her eating and spending her days sweating in rehearsal. In a 2010 interview with The Independent, Portman said of the role, “There were some nights that I thought I literally was going to die.” Hollywood rewarded her with an Oscar.

It is those who control even the most famous celebrities—producers, directors, and management teams—who make them change, either forcefully or unintentionally, with the promise of money, fame, and awards. The actual substance taken by Sparkle is, of course, a not-so-subtle metaphor for the aforementioned lip filler, various types of vanity-enhancing cosmetic surgeries, and even the recently popularized misuse of Ozempic.

This is not to say that cosmetic surgery is inherently bad and that celebrities owe the public explanations surrounding their body—it is not, and they do not. However, there is always a blurry line that accompanies this subject. Cosmetic surgery is not bad, but there are mental and societal impacts that come with changing yourself. Celebrities are still people, but they are people with influence. No, it was not Kylie Jenner’s fault that young girls felt insecure about their appearance, but there is a sense of blame due to her lies about her lips, leading to the bruising of others.

Though it may seem like it, cosmetic surgery is not a new concept. It has actually been around since the late 1800s—with the umbrella term plastic surgery having existed since 1600 BCE—and a majority of these original surgeries were done to amend injuries gained in war. However, there are a handful of documented rhinoplasties and breast augmentations done for vanity. A change in

ATLAS | 19

“No, it was not Kylie Jenner’s fault that young girls felt insecure about their appearance, but there is a sense of blame due to her lies about her lips, leading to the bruising of others.”

appearance to make oneself more conventionally attractive (or even more beautiful than that) has been desired for years. However, it is only in the last couple of decades that this desire has become more widespread and somewhat accessible. The rise of TV and social media has influenced countless people to warp their appearance with plastic. Globally, there were around 16 million reported cosmetic procedures in 2023.

Another rising (and arguably more controversial) appearance-altering trend is the use of Ozempic and similar weight loss drugs. This is because it is not meant to be a cosmetic accessory. Originally used to treat type 2 diabetes, Ozempic (and other GLP-1 drugs) usage has become the 2020s ‘heroin chic.’ It is incredibly disappointing to witness celebrities like Meghan Trainor, whose claim to fame is a song about being happy with a bigger body, or Serena Williams, one of the most accomplished female athletes of all time, publicly endorsing a body-altering drug. The medication becomes widely craved and more easily prescribed, yet more inaccessible for those who actually need it.

Since its popularized vanity usage, Ozempic has constantly fluctuated in price and has frequently experienced shortages. Arguments can be made that yes, these celebrities are selfish, while also acknowledging that they are victims of beauty standards themselves. However, as public figures, they also set said standards and therefore influence the general public to follow in their footsteps.

Is there a middle ground? It depends on how you view it. Celebrities are going to keep changing their appearance—whether by choice or force—and the public is going to keep falling into the trap of influence, and everybody is going to look like somebody and nobody is going to look like themself. We live in a world where we are taught to strive for perfection when the definition of ‘perfection’ is always changing and has never been objective. Yes, you can try to remove yourself by not getting cosmetic surgery or taking Ozempic, but there’s always going to be that tricky loophole where saying “I’m not a part of the system” actively places you in it. Like people, though, beauty standards change constantly. A world where everyone breaks free of the chain is possible, where everyone accepts their natural selves and appreciates the beauty of looking like an individual. The only question is when it will happen.

“ We live in a world where we are taught to strive for perfection when the definition of ‘perfection’ is always changing and has never been objective.” 20 | contortion

“When you are made to believe that Kylie Jenner’s unnatural looks are natural, sometimes the only viable option is to put lips to a shot glass and suck.”

ATLAS | 21

By Harper Pebley

The loveliest of Athena’s priestesses was caring for the goddesses’ temple, as she did most nights, when her story begins. The mighty Poseidon, enemy of Athena, appears at the temple in pursuit of the loyal priestess. She resists, but still the young woman is assaulted by the god. In response, Athena grants her suffering servant a way of self-defense. The priestess’s bright eyes become sharp and serpentine, her long locks of hair join together to make several snakes spring from her scalp. With her new appearance, the woman had a defense: from now on, anybody who so much as looked upon her would meet the fate of stone. She was safe.

This is the story of Medusa as most know it: an empowering tale of survival, yet it is not the original myth. As Ovid first tells it, Athena does not bless Medusa but curses the girl with hideousness in an act of revenge. Poseidon, the true perpetrator of the unholy act, goes unpunished while the victim is mutilated and ostracized. The older version of the tale is, unsurprisingly, disturbing to modern audiences, however reflective it may be.

Via online discourse and recent cultural conversation, the myth has changed to the first version I described. More recently, a collection of Trista Mateer poems titled “Aphrodite made Me Do It,” released in 2019, includes the lines “They made a monster of Medusa… They made a war ground of her body, so she made one of theirs.” It is this developing rhetoric that has inspired a popular tattoo. Many survivors of sexual violence will now get an inking of Medusa’s iconic head as a representation of their resilience and empowerment.

For the ancient Greeks, who lived in a time period that valued power over the individual, a telling of Medusa’s tragedy that reinforced the omnipotence of the gods would likely be comforting and informative. For contemporary audiences, whose more romantic stories tend to surround heroes fighting the power, that version of Medusa is terrifying. So we alter the myth, casting Medusa as an icon for survivors of sexual assault, which resonates with the current society much more than viewing her as a villain.

Ovid is far from the only artist to have his work altered by and for the general public. William Shakespeare is perhaps the king of this phenomenon. Many of his iconic works have been interpreted in thousands of different ways since their sixteenth-century debuts; the tragic Romeo and Juliet is perhaps the most infamous. Sometimes productions of the show, such as its most recent Broadway revival directed by Sam Gold, change the costumes and setting to give it a more modern appeal. Other times, the story is changed from a tragedy entirely. Taylor Swift’s song “Love Story” does exactly this. It retells the star-crossed lovers’ story with a happy ending, where the titular Romeo gets Juliet’s father’s approval and the two end up wed and alive. The song and its re-release currently have over one billion streams each on Spotify. There is a unique power in granting two characters who have been resigned to tragedy for hundreds of years a “happily ever after.” When an audience declines an ending, they assert the power they have.

22 | contortion

To further understand this dynamic, I spoke to a freshman student here at Emerson, whom we’ll refer to as “Max.” Being a Media Arts Production major and aspiring filmmaker, Max told me she is always aware of the tension between artists and their audience, bringing up the notorious rift between J. K. Rowling and her audience. “I think of the phrase ‘money is power,’” she told me. “The money is what makes it. If J. K. Rowling didn’t have this much money, she wouldn’t have this much influence… nobody would hear her.” Rowling is rich off of her stories, namely: The Harry Potter franchise. The saga is currently recognized as one of the most financially successful franchises of all time, having made roughly $34.7 billion.

Harry Potter, as a work of art, maintains an active fanbase to this day—you can watch fan theories on YouTube, go visit the Universal theme parks, read fan-made stories, buy fan-made merchandise, and the list goes on. However, Rowling herself has only declined in popularity due to her interaction with outwardly transphobic rhetoric online. The author recently posted about her excitement over the UK Supreme Court’s ruling that limits the legal definition of a woman to strictly “biological women,” therefore excluding trans women from discrimination protection under Britain’s Equality Act. On the social media platform X, she referred to the ruling as “TERF VE Day,” comparing the decision to the end of World War II. “I just recall feeling disappointment and confusion,” Max said about Rowling’s public opinions on the trans community. “...because how can you write a book series with a fictionalized marginalized group, and then go out of your way to do the very thing you wrote against?… It’s like an abuse of power, it’s very odd,”.

Rowling’s opinions have been a kind of betrayal to many people who grew up feeling seen in the books’ themes of ostracization. “I know many people who it hurts them too much to even look at a copy of Harry Potter, which I have complete empathy for, and I understand, but I don’t know,” Max said. “Those books are very near and dear to my heart… I don’t think anything could make me hate them forever.” When I asked how she currently interacts with the story of Harry Potter, she brought up how she gets creative inspiration from both fan edits and fan fiction. Specifically, she referenced the Marauders Fandom—a subsection of the fanbase that focuses on creating stories surrounding Harry Potter’s parents and their friends. She describes it as “this idea of taking characters we know a little bit and filling in the gaps.” Max adds, “[The Marauders Fandom] comes up with these creative little side stories. There is such creativity in that, it’s excellent.”

Fanworks, as Max mentioned, are perhaps the most direct and clear examples of “separating the art from the artist.” It actively decides that the interpretation of a work is more important than the intention.

The play Nachtland by Marius von Mayenburg beautifully tackles this very issue with one of the world’s most destructive examples: the paintings of Adolf Hitler. Two of the play’s central characters debate how important the artist is to the interpretation of art in the following scene:

ATLAS | 23

“ When an audience declines an ending, they assert the power they have.”

“For us, whose more romantic stories tend to surround heroes fighting the power, that is terrifying. So we alter the myth…”

24 | contortion

“

Judith: A work of art is only what an artist says, if there is no artist, there is silence –

Kahl: No, there are works of art that speak to me although I don’t even know who the artist is.

Judith: Of course, there are also people that talk to you although you don’t know them. And yet you know there’s someone there who is speaking to you.

Kahl: But what matters is what is being said, not who says it.

Judith: ‘I love you.’

Kahl: Really?

Judith: When I tell you that it provokes a different emotion in you than when, for example, your wife tells you

Kahl: My wife –

Judith: Or, for example Frau Dr Günther –

Kahl: That’s true –

Judith: And when my husband tells you he loves you, that’s also different, the effect changes according to who is speaking, there’s no statement without the person making the statement, there’s no art without the artist –

Kahl: But the artist died a long time ago and needn’t concern us any more –

Judith: But he’s still talking to you, and you’re dying to hear what he’s saying,”

ATLAS | 25

It is not my belief that either character in this scene is incorrect. Art is not selfdependent. It is never created in a vacuum, nor can it be viewed in one. An artist creates art for and from themselves, the same way a patron consumes art for themselves.

Stories, reflecting those who tell and receive them, are not fixed things but fluid. The myth of Medusa, once a cautionary tale of divine wrath, now stands for survival. Shakespeare’s tragedies are rebuilt into hopeful melodies. Beloved books like Harry Potter can be reclaimed by those who value the meaning they hold over the actions of their creators. As audiences become increasingly aware of the power they hold, they reshape narratives to better reflect their needs. Art cannot exist in isolation; it is shaped both by the minds that create it and the hearts that carry it forward.

“Stories, reflecting those who tell and receive them, are not fixed things but fluid.” 26 | contortion

ATLAS | 27

By Charlotte Farrar

In January of 2025, Glitch Studios, well-known for its smash hit web series The Amazing Digital Circus, announced it would be dipping into the world of 2D animation for the first time with its new show, Knights of Guinevere, a psychological thriller heavily focused on body horror. The show is being created by Dana Terrace, John Bailey Owen, and Zach Marcus, former showrunners of the popular Disney series The Owl House, with Terrace being its creator. Fans of The Owl House rejoiced at this news, as Disney canceled the show prematurely despite its large fanbase. People were ecstatic to see what Terrace and crew would do under an independent studio with more freedom. The official pilot was released on September 19, 2025. It quickly grew in viewership, surpassing ten million views only three days after being published.

On first impression, the show is visually stunning. The art style is reminiscent of Terrace’s personal work, while maintaining a similar charm to The Owl House. The animation is digitally hand-drawn rather than using rigs, making the character movement more fluid and stylistic. The use of color becomes very prevalent in the pilot, as the color stories for each environment further the audience’s knowledge of each place. For example, the more destitute urban areas are mostly desaturated, while the more lavish locations have rich coloring. Knights of Guinevere, or KoG, also utilizes shape language in an interesting way. While historically, shape language is used to show the personality of a certain character, i.e., an abrasive character’s design being composed of mostly triangles and sharper edges, KoG uses shape language mainly to differentiate the titular character, Guinevere, from the other characters. While human characters are shown with wrinkles and sharper edges, Guinevere’s design consists of smooth curves and round circles. This show certainly has the quality and care that have been missing from big-budget projects, making it a generous breath of fresh air in the current media zeitgeist.

The pilot opens with a narration from an unknown voice telling the story of a princess locked in a tower, scared and in dire need of rescue. A little girl tinkers with a life-sized android splayed stiffly on a bed with its eyes wide open. The girl is beckoned outside by her father, who gestures below at a fireworks display over a theme park floating above the stars. The girl beckons the android she was working on toward her. We see that the android has gooey cobalt blue intestines pouring out from its metal stomach. When it does not come fast

ATLAS | 29

enough, the little girl grabs one of the sprawling tubes and yanks it towards herself, like a cruel owner dragging their dog on a walk. The robot responds with a placid script before glitching, eyes rolling back, and face straining. She then bolts and jumps off the balcony the three are standing on, plummeting to the park below. The girl and her father are unfazed, commenting that the guards will simply find her and bring her back as they had done before. As the robot falls, we hear one final piece of narration, saying that this is the trapped princess, Princess Guinevere, and that she desperately needs to be saved. This opening does a fantastic job at hooking in the audience, the bait and switch of who exactly the narrator was talking about working incredibly well.

The episode follows Andi and Frankie, two young women who work for different sections of the previously shown theme park, Park Planet. Andi works as a junior engineer in the labs, and Frankie, part-time at a factory that makes merchandise. They live on the planet of M7, whose citizens hate the park. Official park signage is graffiti-covered over, and statues of the park’s mascot, Guinevere, are defaced. The planet is heavily contaminated. Smog and trash flood the residential parts of the city, the park throws garbage into the ocean when it flies overhead, and there are signs and news headlines warning of a disease, dubbed “Blue-Lung”, that turns your skin and organs blue.

Many fans speculate that this is not-so-subtle commentary on the environmental and safety hazards caused by the carelessness of big corporations like Disney. The show, making an obvious jab at these companies, holds a lot more weight when you consider the team that created it. Terrace has publicly alluded to her negative experience working under the Disney corporation in the past, insinuating that feeding her best work to an army of profit-driven executives harmed her creative flow and self-esteem. Disney specifically has also received public criticism for their environmental carelessness, whether it be from the carbon emissions and water usage of their parks, or their recent uptick in AI use for promotional material.

As the episode continues, we see more real-world examples of Blue-Lung and what might be causing it. We learn through Andi’s job that most Park Planet animatronics have some sort of blue goo leaking from their seams. Blue smog shoots out of factory buildings, and people around M7 cough up blue goo or have blue patches of skin. It is heavily implied, if not outright stated, that Park Planet is poisoning the planet with this blue substance despite

| contortion

“This show certainly has the quality and care that have been missing from big-budget projects, making it a generous breath of fresh air in the current media zeitgeist.”

ATLAS | 31

realizing it is hurting people. They need this substance to make their machines the way they do, and they don’t care about the consequences it has on the environment. In the real world, of course, big companies are the largest contributors to yearly fossil fuel emissions and other environmental detriments. Cutting corners and prioritizing profit, these corporations are increasing public health concerns in highly industrialized areas and destroying the planet.

At Frankie’s second job, where she works on a barge that fishes trash from the sea and resells it, she discovers a one-of-a-kind piece of ocean waste: an authentic Guinevere android, the kind that interacts with guests at the park. The animatronic is in rough shape, with missing appendages and scraggly, ripped-out hair. Despite establishing how precious this find was, Frankie and her boss maneuver her very carelessly. They repeatedly drop her or handle her roughly, not minding her clearly fragile condition. They eventually throw her into a storeroom on the ship, her few remaining limbs contorting and twitching unnaturally around her as her one eye stares lifelessly ahead. There is something to be said about the in-universe treatment of Guinevere, both as a character representing Park Planet and as an object of desire. Early on, we are shown a flash of notes that an animator would recognize as character sheet feedback. The feedback on a sketch of Guinevere relays that she needs to be more perfect. She cannot have any sharp, “violent” edges in her design. She cannot have any wrinkles, not even the curve you’d find naturally under your eye. Guinevere’s design is perfectly catered to every age group, with a kind demeanor and a pretty dress for kids and an exaggerated hourglass figure for the adults.

In the episode, we briefly see a news article detailing how someone snuck a weapon into Park Planet and purposefully damaged a Guinevere holding a meet and greet with a child, the pictures showing blue blood splatters and severed metal arms. This seems reminiscent of how many adult theme park goers in recent years act inappropriately towards character actors. With the “customer is always right” culture that big corporations have curated over the years, there has been a steady increase in people seeing anyone who works with the public as mere vessels for their satisfaction and entertainment. This universe replaces the idea of a character actor with a sentient android, reflecting the idea that these workers are often treated more like objects than people. While the Park Planet mascot, Guinevere, is defiled, there is an allure to her that caters to every taste. However, when this manicured image is damaged, she becomes just another piece of junk to sell.

32 | contortion

“While the Park Planet mascot, Guinevere, is defiled, there is an allure to her that caters to every taste. However, when this manicured image is damaged, she just becomes another piece of junk to sell.”

ATLAS | 33

Frankie, dead set on fixing the Guinevere, convinces Andi to help her steal the android. They sneak her into the Park Planet Labs, where the hurt Guinevere screams bloody murder just before a ginormous creature of inhuman proportions attacks them. The girls take cover in a spherical construction, which looks strikingly similar to the Epcot Ball, but the giant homunculus simply picks it up and throws it full force against the wall. In the commotion, Andi’s arm snaps almost clean in half, her jagged forearm swinging limply at her side for the rest of the episode. Andi drags Frankie to a nearby elevator for safety, but Frankie turns back one last time before the doors close. We then see Guinevere, who was only recently a twitching mess dragged out from the ocean, in full control of the pieces of her body she has left. She looks back at our heroes, her one eye opened unnaturally wide and her smile splitting her face uncomfortably. The translucent elevator doors shut, and we see crimson blood splatter and hear the squelch of organic matter being torn apart. The doors open again, and we see the creature defeated in a bloody mess. Guinevere holds herself up for a few more seconds before losing control and slamming into the ground.

Knights of Guinevere is a pilot that blows so many current shows out of the water. In just one episode, it has established clear symbolism for capitalism and the harm it is causing, created a memorable setting and characters, and left millions of people begging for more.

34 | contortion

“She looks back at our heroes, her one eye unnaturallyopenedwide and her smile splitting her uncomfortably.”face

ATLAS | 35

Photographer Emma Fisher

Models Audrey Collins & Matthew Biser

Stylist Emma Fisher

Illustrator Ella Sutherland

Design Emma Fisher & Ella Sutherland

36 | contortion

38 | contortion

by Ella Sutherland

I remember first hearing the catchphrase “You don’t alter Vera to fit you; you alter yourself to fit Vera” leave Kate Hudson’s mouth when I was a kid watching Bride Wars. Ever since, I’ve heard it passed around like fashion scripture. Beyond my certainly being too young to think about that kind of thing and the twisted aspirations the quote elicits in young people, the quote reveals a truth: fashion has always demanded contortion. Clothing is rarely a neutral canvas. Fashion is treated like bait on a hook, something to earn, to mold yourself around—a trap of ideals that corsetry captures perfectly: at its root, a means of reshaping the torso into an ideal. The quote and corsetry alike become less about devotion to fashion or designers themselves and more about the centuries-old negotiation between body and garment.

Fashion has and always will be tied to the body—whether shaping, disciplining, glorifying, or punishing it. The byproduct of this relationship is most epitomized in corsets, cinchers, and bustiers. They’re total paradoxes of style: tools for patriarchal control and symbols of feminine power, aesthetically pleasing torture methods and vices of expression, cages and armor.

The corset first appeared in European fashion in the 16th century and quickly became an indicator of wealth, status, and femininity. Early designs used whalebones or metal to force torsos into stiff and rigid structures. It became the expectation for women to lace themselves up in these pieces, sacrificing comfort and mobility so their bodies were a wasp-waisted reflection of beauty and virtue.

Corsets were more than items of clothing—they were social regulators. In a very physical way, they enforced the notion that women should be controlled and ornamental. A smaller waist became synonymous with a greater virtue. Corsets

were both a fashion statement and a cage, manifesting patriarchal structure in bodily form.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, corsets began to evolve. People started to realize corsets were a health risk for women and criticized the damage they inflicted on their bodies, as if the compressed lungs and displaced organs weren’t enough of a red flag. Designers began experimenting with looser silhouettes, girdles, and bras as alternatives.

Corsets never truly disappeared— they evolved, taking new life in cinchers, bustiers, and shapewear. As the physical garment evolved, so did its meaning: from discipline to glamour, or enforced femininity to sexual liberation. Women took agency over the pieces that used to represent patriarchal control. I remember tugging one off a thrift store rack once—stiff boning, scratchy satin, hooks that took forever to close. It was uncomfortable as hell, but in the mirror I felt better. That tension—discomfort vs power—is exactly what makes corsetry fascinating.

Still, the tension never really disappeared. From Dior’s nipped-in “new look” of the 1950s or the Madonna-inspired corsets of the 1990s, the cinched waist has remained a cultural fixation and a reminder of how we as a society interpret power, sexuality, and desirability.

Today, society is in no drought of the waist-sculpting garment rush. Reality TV stars, celebrity influencers, and fashion icons alike have repopularized waist cinchers by blending a growing obsession with fitness culture and aesthetic ideals.

The Kar-Jenner clan is definitely leading this fad. From Kim Kardashian’s Mugler Met Gala look to her own SKIMS shapewear brand, to Kylie Jenner’s Instagram bustiers and waist trainers, women all over the world see this as an ideal. And no, I’m not saying everyone needs to praise the ATLAS | 39

Kardashians, but it’s hard to deny the impact. We have once again wound up in the same spot with the same old question: why are we all so obsessed with squeezing ourselves into shape?

The answer doesn’t have to be patriarchally shaped. It can actually be quite aspirational. Waist-sculptors create a dramatic transformation and a visual spectacle of femininity and power. Corsetry speaks to desire, both of our own and of others. It creates a fashion fantasy. The garment doesn’t hold the allure; the metamorphosis it imposes does. Haven’t we all felt that squeeze—literal or not?

There is a paradox within the modern corset. When someone squeezes themself into a piece of shapewear or laces themself into a corset, are they engaging in an act of expression or submission? I think both.

For some, corsetry has been reclaimed as a form of art. Drag queens,

burlesque dancers, and avant-garde designers use bustiers, corsets, and cinchers to play with gender, sexuality, and fantasy. Corsetry is a way to amplify presence, exaggerate the body, and command attention. Ironically, the thing that is designed to restrict and confine is what sets some people free.

On the opposite end, the same garments reinforce the pressure to mold ourselves into narrow ideals of beauty and femininity. Waist trainers in fitness culture mirror old narratives of bodily inadequacy and discipline. Turning back to the Vera Wang quote—by altering ourselves to “fit” clothing or ideals, we sacrifice so much in the process.

Fashion is and has always been more than fabric. Fashion is an aspiration. From branding to runways to red carpets, fashion is not marketed as accessible; it is luxury. It is an ideal to chase. Corsetry embodies this dynamic because it physically forces the

40 | contortion

Clothing is rarely a neutral canvas.

body to meld into a shape that is impossible without artifice and pain.

Historically, this expectation has been more punishing on women, the queer community, and those with “substandard” body types. To lace up a corset is to erase difference and conform to what is considered ideal or acceptable. Still, the act of putting on a piece of corsetry has been subverted and claimed as a piece of performance, armor, or drag. The garment itself does not determine its own meaning; the wearer does.

At a glance, hearing things like “you alter yourself to fit Vera” makes us giggle in a throw-away romanticization of the devotion fashion lovers have to couture. But when considering the larger history of corsetry, it reads to me more like a confession. Fashion is rarely democratic. It is something that requires sacrifice and contortion. It asks bodies to mold to certain ideals rather than honoring the humanity and diversity of fashion.

Yet, the very act of alteration can be completely reframed. People choose to “fit Vera,” not out of submission but as an act of performance. It is a way to participate

in a fantasy and enter a world of glamor and aesthetics. There is a power in that. The same garments that once symbolized control can now serve as a declaration of sexual independence and a stroke of theatricality. This paradox remains unsolved— and maybe it shouldn’t be solved. Corsetry is polarizing because it embodies such tension between repression and expression, control and freedom, idealism and authenticity. Sometimes a corset is neither art nor oppression—sometimes it’s just a hot top for a Friday night out. Corsets, cinchers, and bustiers prove fashion isn’t neutral. It doesn’t just serve to cover the body—it reshapes, punishes, glorifies, and distorts it. Whether your stage is the runway, the street, or a literal stage, the garments carry a lineage of baggage - yes, of patriarchal control, but also legacies of reinvention and resistance.

42 | contortion

Corsetry is polarizing because it embodies such tension between repression and expression, control and freedom, idealism and authenticity.

ATLAS | 43

Sifting through my closet is like meeting a lineup of completely different people. Everything from costume lingerie, tiny “going-out” tops, huge furry coats, and summery button-ups lovingly coexist, making every morning feel like a thought-out selection of who I plan to be that day. Most mornings, I open my drawers and put on the same t-shirt as always, but when I actually plan out a put-together outfit, it has the ability to change my mindset. With each outfit I wear, I feel like a slightly different person. Or, more specifically, a slightly different writer.

44 | contortion

By: Lucy Latorre

“With each outfit I wear, I feel like a slightly different person.”

46 | contortion

I bought this perfect jean jacket blazer as a back-to-school present for myself. When I found it at the thrift store, I knew it was at least two sizes too small, but I chose to blissfully ignore it. With big brown buttons and a bit of scalloping on the sides, it screamed “writer.” If I wore it with a page boy cap and sat myself down in the corner of a coffee shop, it would look like the perfect writer tableau. I would fold open my journal—which would obviously be bursting at the seams with the next great American novel—and put the bottom of my pen by my mouth, contemplating something that those around me couldn’t even begin to comprehend. I’ve put it on a few times, but the compression on my arms drives me crazy. Maybe, if I stretch it out, I can wear it one day, but that means putting up with the tightness for the time being. Plus, I’d be attempting to write without being able to bend my arm.

In Amsterdam, I found this adorable slip dress that I swore fit me in the moment. An absolutely gorgeous Carrie Bradshaw moment, like a journalistic siren. I dreamt of attending galas in it, rubbing elbows with celebrities and then going home and typing away about how it felt to see my situationship at the bar last week. I’d start wearing my hair curlier in public and walk around in heels, but I’d never trip and fall in them. Those kinds of writers never trip in heels; they wear them like extensions of their feet. They click-clack like a typewriter each time they enter an underground concert they’ll discuss in their next blog post. I tried that satin slip on again and there was no way I could ever make it work. One boob was higher than the other. A very distracting image to see in the reflection of a laptop.

ATLAS | 47

“...when I shut my closet and silence the fantasies, I feel this weight lifted offmy shoulders...”

48 | contortion

Sometimes when I wear a leather jacket there’s the smallest part of me that thinks I’ve figured it out. I almost feel like one of those writers who reads Jack Kerouac in a graveyard, discussing the human condition over a pack of cigarettes. They annotate poetry and send think pieces to local newspapers. They also have the incredible ability to write absolutely anywhere, no matter how loud or crowded the surrounding world is. These kinds of writers just drown it out, disappearing into their own brilliant minds. My jacket is oversized to the point that I feel like I’m drowning in it. I wrap it around me as the air gets colder, creeping my hand past the sleeves to try and write anything down. But, my hand gets so cold that I put it back in my pocket.

I tend to do my best writing braless, in a pair of sleep shorts, propped up by the stiff arm of my couch. Sometimes I write when I’m wearing melting makeup, drunk and deep in my head. Other times, I’m just wearing what I always wear, feeling a sense of inspiration in an ancient sweater, dirty jeans, and greasy hair. I take great pride in my clothes, but when I shut my closet and silence the fantasies, I feel this weight lifted off my shoulders. I write best when I’m imperfect.

ATLAS | 49

From first to eighth grade

I wore a uniform to school. For those eight years, my life was characterized by polos and shades of plaid.

It was the first day of first grade, when uniforms were new and exciting. The color and strictness of uniforms changed as we got older, but this first year girls started out with the jumper: a skirt with two thick strips of fabric going around the shoulders, always layered with a white polo. On the playground, two girls pulled down their navy shorts hiding beneath the skirt to show me.

“What, you don’t have biker shorts?”

I didn’t, and was subsequently scared to go on the tall playground structure where the floor was speckled with holes. My face flushed as they questioned me further. Neither I, nor my parents knew this unspoken rule—we’d just assumed everyone wore the jumper like a usual skirt. The rest of the school day I became keenly aware of my difference.

By: Lily Suckow Ziemer

last two pairs in my size, I let out a breath for the first time since recess.

By third grade biker shorts weren’t cool anymore. All the girls wore loose, short, black Nike shorts. They weren’t school-approved but most got away with it. The biker shorts I cried over were useless now and I perused the Target athletic section for shorts with a similar cut.

50 | contortion

That night I came home crying. It was 6 p.m. by the time my parents got home, and only one of the two stores that sold my school’s approved uniform was still open, and closing soon. “Can’t we just get them tomorrow?” my dad asked. We couldn’t. I saw those girls in my mind’s eye, standing in front of the play structure and asking me if I’d gotten any. My dad drove as fast as he could, with my rigid instructions playing in his head: “They have to be the navy ones, a little bit long. Biker shorts. They are called biker shorts.” When he arrived home with the

It’s silly in retrospect. These shorts were rarely visible. We often took our skirts off for gym class, but it shouldn’t have mattered so much for something that barely peeked out for most of the day. For some reason it did though. The same went for most things. Did your polo shirt have the band on the bottom? Did you wear white socks with plaid ruffles? Were your shoes ballet flats or Mary Janes? There was a sort of unspoken hierarchy. If you didn’t wear the popular subversions of the uniform, you stood out. Our similarities made it so obvious when someone broke the trend. I can still remember the girls who rolled their skirts up to make them shorter, and the girls who bought extra long ones. There are many reasons schools institute uniforms. They are said to establish unity, make students concentrate on studies rather than what they are going to wear tomorrow, and level the playing field, displaying everyone as equal. At my school, and thousands of schools around the world, the adults in charge of us shaped how we dressed. They tried to fit us all into one box.

“We are all shaped by fashion trends, even choosing to abstain from them is a contortion to what’s popular.”

52 | contortion

As someone who wore a uniform, I can tell you it didn’t always work. Even when a group’s style choices are erased, differences appear, especially to those in the group. Maybe I didn’t go back to school shopping every year, but I did pay attention to all the finite details of my uniform, and others’.

Like most kids, I wanted to fit in. I had my mom hem my skirt so that it wasn’t too long or too short. I could distinguish my five identical shirts by the softness of the fabric, and chose the nicest ones based on the day ahead of me. I scoured the isles of DSW to find the best, black dress shoes. These choices were influenced by my peers, what the majority was doing. I imagine my teachers didn’t notice the trends that affected their young students, but they were poignant to me. When I reached high school and we were no longer required to wear uniforms, most adults expected it to be the wild west of fashion. It wasn’t. In fact, I was already acutely aware of how to observe trends and how to wear what everyone else did. The uniform didn’t disappear, it just became shaped by us.

We are all shaped by fashion trends, even choosing to abstain from them is a contortion to what’s popular. Sometimes we want to look the same, become a united front like my school always wanted us to be. Sometimes we want to stand out, follow the opposite of a trend. Regardless, our styles are always shifting in regards to one another. Nobody exists in a vacuum, even if we want to.

ATLAS | 53

If beauty is the art of transformation, my body is the canvas. When I was younger, I would look in the mirror and see my reflection as an opportunity, a chance for expression. But as I grew older, I started to view myself through a camera lens. I push and pull my skin, trying to mold my body into a different shape every day. I cinch my waist, pad my chest, and flatten my stomach. A closet full of clothes turned into a collection of shapewear, with shape taking precedence over style. As shapewear and fitted undergarments have exploded in popularity, the female body has become the most prominent yet inconsistent trend in modern fashion. And young women like myself have been turned into both the biggest victims and supporters of the movement. My first experience with shapewear was in fifth grade when I started wearing bras. I remember anxiously pacing through the aisles of my local Justice, overwhelmed by the options. There were bras meant to suppress the chest, push up bras to enhance the chest, even bras solely meant to prepare and “train” young girls to wear more bras in the future. When a worker came to help us, she mentioned that the push-up style was their most popular offering. As I tried the bra on, I grew estranged with my reflection. The body I saw in the mirror was not the one I grew up in. It was an entirely different shape, one that didn’t feel like it could ever truly be mine. I was disgusted. I was confused. Yet, most importantly, I was intrigued. Clothes didn’t just sit on my body anymore. They changed it. And the change seemed to make all the difference. The next day as I was changing in the locker room before my physical education class, a friend came up to me. She said I looked different that day. When I asked her what she meant, she simply replied, “You look good,” and walked off. In that moment I internalized my feelings as a fact: to change my body is to look good.

54 | contortion

There is something wrong with what is naturally there.

I started wearing shapewear during my sophomore year of high school, spending almost all of my birthday money on it. I ordered a push-up bra and mid-waist shorts from SKIMS to widen my chest and slim my waist down. Putting these items on was like having three different bodies all at once: the large curvy chest, stick-thin torso and legs, and the ugly skin that laid underneath. It was a sensation like no other. In particular, I was obsessed with the shorts, to the point where I couldn’t bear to look at myself without them. I wore shapewear no matter what, even to bed. Some mornings I would wake up with marks or bruises on my waist. It hurt, both emotionally and physically. But I ignored my pain, prioritizing other people’s perception over my own self-worth. Once I started college, comments on my body came from everywhere. My friends would often tell me how great they thought I looked. In those moments, I felt beautiful. But once I was left alone with my reflection, I realized the body they were complementing was not mine. They were admiring the contortion of it.

SKIMS and their products heavily affected the way I viewed myself. On their website, the brand says their mission is to “set new standards by providing solutions for every body… and consistently innovate on the past and advance our industry for the future.” The key words in this statement are “solutions” and “innovate.” Both of these words imply the existence of a problem. In context, the problem is the body. And the only way to “fix” this problem is by buying from the brand. At the time of writing this, the brand sells fifty-three different forms of shapewear and nine styles of push-up bras. Each style is meant to “fix” a part of your body, from padding the hips to accentuate one’s curves or pushing against the stomach to flatten it. Whatever insecurity

by Madison Smithwick

The body itself is the sexiest thing a woman can wear.

you have, SKIMS sells the “solution.” Insecurity has become its own industry, with SKIMS at the forefront of the business. The brand was estimated to have a value of four billion dollars in 2023, which has only grown in recent years. Many other brands have also found success recently, including Spanx, Honeylove, Leonisa, and more. None of these companies sell clothing, they sell the idea of a perfect body. Girls can change their style by changing their bodies. The body itself is the sexiest thing a woman can wear.

The most important and damaging aspect of shapewear is that it is undetectable. With people being able to change the shape of their bodies on a whim, the image of the female body has become an intricate puzzle that loses pieces by the day. Under this lens, I saw my body as an object. Rather than follow modern trends, I choose to follow my own personal style. Now when I look in the mirror, I recognize what I see. I understand that my body is a part of me, not a product of or for anyone else.

By Emma Ross

There was an elevator I rode every day during my months in France, tucked away in a student residence off the Rue du Sauveur in Lyon. No bigger than a broom closet, it is the smallest elevator I’ve ever squeezed into—a space large enough to carry one person comfortably and three people awkwardly. If more than one person occupied the cabin, it would take the bravery of a lion tamer and the contortion skills of an acrobat to shove my way in. You can imagine the quiet celebration I held each time the door thundered open to reveal an empty space. A mirror was glued to the back wall, likely to make the space appear twice as large. No such illusion was created. Yet every time I boarded the elevator, I studied the image of myself—stripped bare by the white, fluorescent light, and, for a few moments, I became disembodied. For a few moments, I was not a woman in France, nor a lonely person in a foreign city, but a stranger in an elevator, suspended in space and time.

The fabric of the world rips apart each time the door of an elevator peels open and an individual is invited into limbo.

French anthropologist Marc Augé defines non-lieu or non-place as a space of transience in which one remains anonymous and unattached; such spaces do not harbor community, connection, or identity. Nonplaces are the in-betweens of our lives. Humans transform from individuals to ciphers.

I acknowledge that, for some, this may sound unappealing—depressing even. You may buy into the rom-com ideal of elevator meet-cutes: the romance of two people exchanging shy glances and hesitant smiles, followed by an expression of love for The Smiths. You may be throwing your hands into the air and crying, “Can’t a person dream?” But is there no relief to be found in the anonymity of an elevator cabin? We spend much of our lives searching for, grasping at, identity and individuality. In the

non-place of an elevator, we can shed the heavy coat of observation and simply float in the in-between for a short ride up or down.

The weightlessness of our bodies during an elevator’s journey is not just inertia acting on our mass, but the feeling of unburdening ourselves of identity.

My heart used to jump at each clank and shutter of the freight elevator at my last retail job. I was anxious that the machine would break down at any moment. It was a slow elevator, beginning each trip with a startling lurch. Sometimes the doors would open prematurely, while the cogs were still whirring and the floors had yet to align.

Other times, the doors would pause, only peeling back once I began to sweat a little and wonder whom I’d have to call for help. For the first year of that job, I avoided the elevator.

“

Can’t a person dream?

I grew used to the wacky machine by the second. By the third, I was excited at the possibility of being trapped inside the stuffy space, even if only for a few moments. I was eager to elongate the experience of anonymity—to lengthen the time spent outside of my existence. I could slouch, drop my face, heave a heavy sigh, or do nothing at all; I would be the only witness. There was no need to think of the world outside of that elevator. I was completely removed from it. Like an actor walking offstage, away from the prying eyes of the audience, the mask could be dropped.

In a grand city like Boston, elevators are rarely unoccupied. Each time I enter a bustling building on Emerson’s campus, there

62 | contortion

is a crowd gathered in anxious wait for their ride up. Students will check their watches, glue their eyes to the flashing floor numbers, or tap their feet against the ground with no particular rhythm. When the chime rings out and the doors finally open, we all file in, convinced we can fit just one more person. Once inside, we all face forward, tucked into ourselves, and stand in silence until we’re delivered to our destinations. Like sardines in a can. Or many Schrödinger’s cats in a box. I don’t remember the faces of the students I ride with in the elevators, and I imagine they don’t remember mine either. I feel the warmth of them as we brush shoulders, and the tickle of their shirt fabrics against my skin. But they are simply entities around me. They are nobody. I am nobody. What a relief.

While we pack ourselves into these claustrophobic motorized cabins, the boundaries of the world fall away. The simple conformity of standing in place, looking forward, keeping one’s business to oneself, frees us from the rough, solid gaze of looming institutions. Each elevator is a hole punched through the paper of society—a blank space in the middle of the material, through which we can poke our finger, wiggle it around, and feel nothing but air. A reprieve from the texture of life. You can, for a moment, and at no extra cost, escape the weight of existence without taking any drastic action. Just press the button and wait for the doors to shutter shut. You will become nothing; isn’t that wonderful?

“

By Brenna Sheets

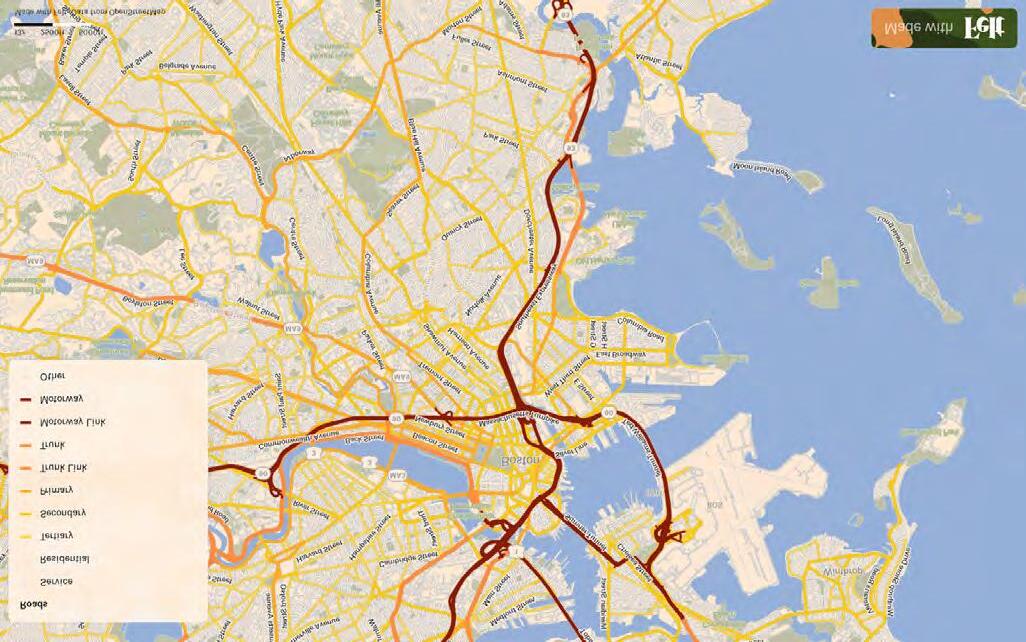

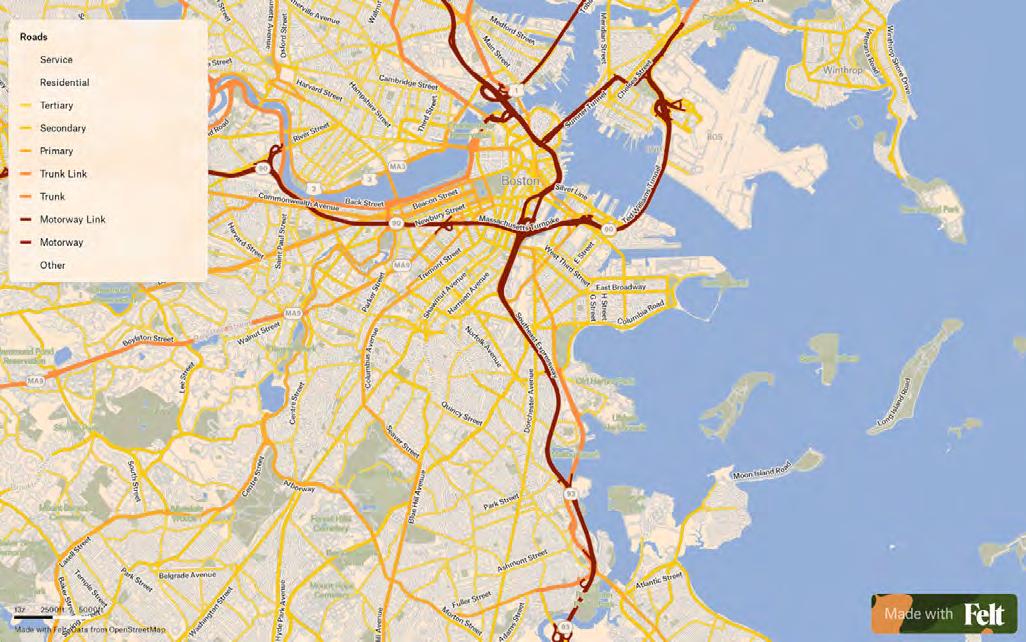

There’s a saying in Boston: “If you miss the exit, just go home.”

Let’s use Rock & Rye, my favorite dive bar in Boston, as an example. If you’re driving to Rock & Rye from the south of the city, such as Dorchester, you’ll take I-93. If you miss the exit toward Lincoln Street, you’ll miss your last chance to get off in downtown and will, in fact, have to do a whole life-questioning circle around the city. Well, at least there’ll be a nice drive-by tour of the scenery, an optimist would think. Boston laughs back at you. You’re underground the

ATLAS | 65

majority of the time, lightly shielding your eyes from the tunnel’s harsh lighting, wondering how the Big Dig was even possible, and hoping there’s ventilation for all the backed-up car exhaust.

I know this because, now that I’ve lived in Boston for three years, it’s happened to me on numerous occasions—in Uber,

66 | contortion

en route to Emerson, Moxy’s, Urgent Care, Rock & Rye, The Paramount, The Wang, The Q, The Common, and the shops on Newbury. Who knew they built the subway for a reason? The Red Line is my best friend when it’s reliable, but it tends to fall off the wagon a few times a year: We have a toxic, co-dependent relationship.

A 2024 study by WalletHub on the best and worst cities to drive in ranked Boston 94th for traffic and infrastructure, with an overall score of 86 (100 being the worst). Even if you’re traveling on foot, you can take The Dark Side of Boston tours, which lead visitors through the North End’s winding streets and alleyways for true tales of misery, misfortune, and murder.

One can learn all about the Great Influenza of 1918, the Molasses Flood, and the infamous Brink’s Robbery, all of which were so heavily immortalized by Boston’s infrastructure.

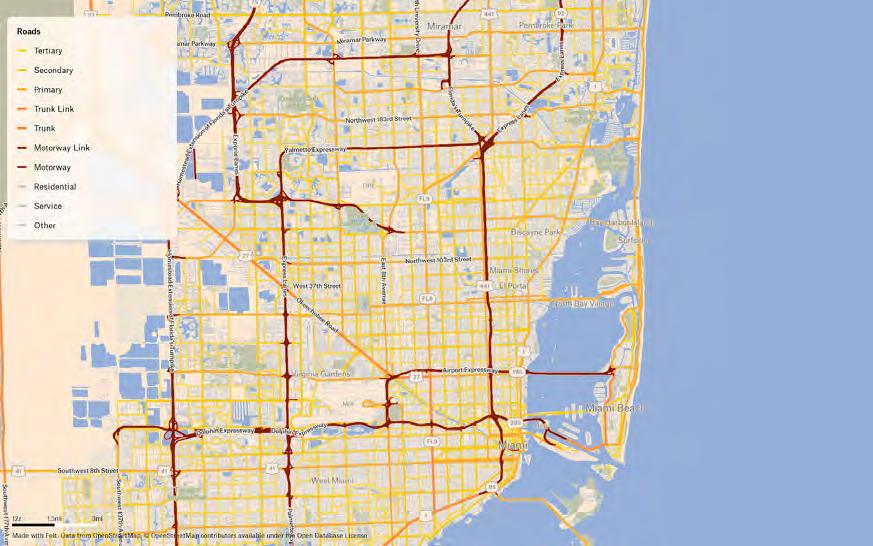

It’s not just my perception as a transplant. Boston really is built differently. Unlike most major US cities, Boston’s street system didn’t emerge from a central plan but from centuries of layering.

In the 17th century, what is now downtown Boston was once the Shawmut Peninsula, known as Mushauwomuk, which translates to “the boat landing place” in the Algonquian language; it was part of the Massachusett nation, according to the West End Museum. William Blackstone, a lone English settler on the peninsula, invited John Winthrop to move Puritan settlers to the area in 1630, and they renamed the settlement “Boston.” The Massachusett were forced out of the area within a decade. The narrow cow paths and foot trails eventually hardened into roads. When the city expanded by filling in marshes and annexing nearby towns, the street system grew like a patchwork rather than a blueprint. By the time cars arrived, the damage, if you can call it that, was already done.

to make more than one wrong turn unless you’re trying to, and there’s usually an easy solution, with traffic being the only headache.

The result is a city where one-way streets double back on themselves, where there are five-way intersections, where the tunnel rats never see the light of day, and where a single street will change names multiple times in the space of a mile. It’s a place that has reinvented and expanded itself for centuries, and it expects you to do the same as soon as you sign your lease.

For reference, I grew up in Miami, Florida, which has a grid system and no trains.

In Miami, everything’s laid out pretty straightforwardly. Streets and avenues are numbered and perpendicular, like graph paper stretching toward the horizon. It’s hard

I enjoyed growing up in Miami, but I always saw it as just that—a place I would grow up. I always dreamed of moving away and living a different life than the one I’d seen: I wanted more than just flip-flop tans and EDM music and drugs, and living at home. I didn’t want to kick it with high school friends and pretend to care about Art Basel and avoid discussing politics as the city turned red. Yet, it seemed like every time I tried to veer off the plan and leave Florida, the universe stood firm on its decision.

That summer, after high school graduation, I found out that no matter how smart you are, how many clubs you join, or how hard you work, there are just some things you can’t do without money. One of those things was going to college in New York City. I bet big and applied to the top

ATLAS | 67

Boston is a maze, which is fitting because it’s also a rat’s race. “ “

schools only, desperate to leave my life in Miami and expand my horizons in pursuit of something greater. But when I found out my scholarship would still leave me $150,000 in debt, and my mom’s credit was too poor to co-sign any kind of loan, I gave up. I remember a financial aid personnel telling me over the phone, Well, you know, maybe if you can’t afford it and the loans are an issue, you should sit down and think, ‘Is this really even the environment for me?

The possibility that I was somehow destined to live a Floridian life was terrifying. When I finally managed to scheme a plan to leave the state after college, I figured that being in Boston would be the easy part, the reward after the grind.

I was just a little off track.

Boston is a maze, which is fitting because it’s also a rat’s race. It’s full of twists and turns, side alleys with one-million-dollar brownstones, underground cafes, and train escalators that lead to more trains instead of above ground. It has over 50 colleges, over 100 company headquarters, around 700,000 residents, and above 40,000,000 airport passengers every year. The population and tourist destinations are not something I’m

68 | contortion

unfamiliar with, but I never thought I’d find myself embarrassed and confused at intersections so often.

My time in Boston has mirrored its streets. Life delivered more unexpected turns than I could have imagined, with moments that felt like the universe was expelling me back to the Florida marsh where I belonged. It wasn’t like Miami at all, which always seemed to be begging me to settle, to follow familiarity and discontentment. Boston was quite literally turning me up on my head at every turn. Any time I’ve found myself settling in, it’s thrown me right back out onto the streets. I’ve taken probably all the wrong turns you can think of in the past three years: I stayed in the wrong career, picked the wrong apartments, settled for the wrong friends, talked to the wrong guys, chose the worst possible temporary this and momentary that, and somehow ended up in the suburbs, of all places. I’ve had to double back, reroute, and start all over, repeatedly.

I still need Google Maps to get around. I still have to check where the Green Line splits and whether the Red Line is delayed. But the panic and frustration of not knowing where I belong have softened. Maybe I’ve just gotten used to adapting to the unnatural. Somewhere along the way, the disorientation stopped feeling like a mistake and started feeling like a continuous journey. Or maybe I’ve simply grown crazy with the city.

Missing an exit doesn’t always mean you have to go home. Sometimes it just means you take the long way, and not even for the pretty sights, but just because it’s a part of the deal.

70 | contortion

By Matthew Provler

Everyone and anyone, no matter what, needs to work a customer service job—not just for the money (although it often is just for the money), but to scrape against the scum of the earth in the form of our fellow human beings. Out of all the possibilities, food service being a notable horror, I ended up in retail: Men’s suits, to be painfully precise. The only place that would hire me, at 16 with no experience, was a suit store in need of warm bodies to watch the front door and absorb the blasts of human incompetence. On. Long. Island.

Fast forward to the present day: The vanity, ignorance, and disregard for others are unmatched by the clientele of Boston’s famous Newbury Street, a feat Long Islanders couldn’t dream of. After nearly two years of working on this tourist-infested, consumerist wonderland of a mile-long stretch, I have grown fed up with the disingenuousness of the sickly sweet smiles and the coddling of grown adults as they behave like tantrumthrowing toddlers. I am sick of the flippant destruction of tourists and trust fund children as they march through the store, ATLAS | 71

tearing sweaters from shelves with animalistic fervor, only to toss them back down at the turn of their noses. Although innumerable, I wish to catalog a few experiences through distinct vignettes, sharing snippets from across the years of idiocy spent with Newbury Street “elites”:

Through my years of working in men’s suits, I’ve encountered the elusive “know-it-all.” The irony is that oftentimes, if not always, they don’t know what they’re talking about. They know the difference in lapels (they mix up the only two relevant ones, somehow), they insist on the correct fit (meaning too tight at the stomach and waist, with the lapels puckering outwards and rippling fabric stretched too tightly around the shoulders), and they always back up their “knowledge” with the fact that they wear suits everyday, and for their job none the less.

Speaking of which, a common customer is a young client whose father is buying them a suit for their first big-city job. And I have to tolerate the constant arrogant interjections from said father, who insists he knows all there is to know about suits.

A quiet day arrived, with the typical customers and appointments. Suits were fitted, fabric and accouterments chosen, and payments taken. Enter a father and daughter. The daughter was looking for a suit for a job that I couldn’t care enough to remember, but I nodded my head in tepid encouragement as the father loomed nearby. He told me he wore suits every day (as many of his type had before). I carefully measured and evaluated how to move on to the next phase of the fitting, tuning out the father as best as I could.

And yet, my curiosity struck. Why does he need to wear a suit for work every day?

“I’m a lawyer,” he said in a dry tone as I pinned the try-on jacket on his daughter.

“Oh, cool.” I was pleasantly surprised. “What kind of law?”

72 | contortion

“Environmental law,” he replied, rather quickly.

I remark again, with a slightly genuine, “Oh, that’s pretty cool!”

“For oil.”

Ohhhhhh . . .

“Ohhhh . . .” I couldn’t even hide my disappointment, the perfect subversion of a morally bankrupt joke.

And so, in an effort to either cope with my reaction to his career decisions or his own career decisions (perhaps both), the father began to explain, grasping to convince me that his cause for advocating big oil’s needs was morally righteous. And the ducklings slathered in oil, fluttering around helplessly as their homes are destroyed and their lives taken? No, no, no, oil needed the help. Oh, bro-ther.

“The soles of your shoes were made with oil,” he rambled on. “Rubber is made with oil.”

I paused for a moment and pointed to my shoes: leather loafers with a leather sole.

“No, mine are actually made of leather,” I politely retorted.

“Well,” he coped on, “leather soles are actually less durable than rubber soles.”

So that’s bullshit. “You’re wrong,” I interrupted, “but that’s ok.”

I gave a cold, smug smile to the thensilent father. Little talk filled the time, and I finished my job by taking his credit card for payment alongside a curt, “Have a nice day!”

Fast forward, a new job, which felt eerily familiar to a bygone one, was then my sole activity amidst a summer in Boston spent surviving off each paycheck for food and rent. The clientele? Many had gone to the store since they were younger, reminiscing on how their father (almost always the father when it comes to suits) bought them their first suit there. Mind you, our suits start at $1400. I hope that puts into

Raised by money, not manners. “

“

74 | contortion

Havea goodone , and so on. “ “

perspective the upper class to which the customers belonged.

A strange yet telling detail I noticed early on was the particular trend of credit cards that customers pulled out at the register: Platinum and Gold Amex that accompany extravagantly high annual fees and luxurious benefits. The annual fee alone would’ve been enough to feed me for a month, and then some. To this certain echelon of customers, I’m often seen as a helper, not as a human.

A coworker always retorted, “Raised by money, not manners.” And they were not wrong.

After a day of mulling over decisions and strained by a lack of food, I swayed at the granite-topped register, staring intently at my watch as minutes pushed past my eyes, insurmountable as mountains, when a customer approached. He had been shopping around. I noticed him seemingly fade in and out of reality as he appeared behind and around me mysteriously, reuniting with me at the register with a measly button-down shirt.

His lip pouted, arms crossed, and eyes glaring above my downturned head as I sluggishly scanned and bagged his prized purchase in delicate tissue paper. Have a good one, and so on.

“Are you new?” He asked a loaded question I’d heard many times before. It’s never a good sign if someone asks if you’re new. It always means you, personally, fucked up and are about to receive an unknown reckoning.