© Copyright, Atlantic Technological University, 2023

3

When you are old and grey and full of sleep, And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

4

Like so many other literary adventures, this journal began with a vision. For allowing us to be part of this vision, we the 2023 Editorial Team, are grateful.

The first Scrimshaw Collection was beautifully produced in 2021, under the aegis of the Connaught Ulster Alliance of three institutes of technology: Sligo, Letterkenny, and Galway / Mayo. Since then, the alliance has come together as one vibrant Atlantic Technological University. Scrimshaw strengthens the ties between our different campuses. The literature and artwork captured in this journal has been collected from students, lecturers, alumni, and staff from across the University.

As with the first, award-winning edition of Scrimshaw Journal, we set no theme, allowing our many contributors the freedom to express their voices uninhibited, and they did not disappoint. It is somewhat fitting to realize, as we come to the end of our three-year journey as creative writing students, that the emergence of a ‘Journey of Life’ theme came organically. Within these pages, through the prism of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, painting, sculpture, and photography, you will encounter life experiences, from cradle to grave.

Scrimshaw not only combines work produced from the West and North West but includes a wider geographical spread from across the country and beyond. 2023 will see the graduation of the first cohort of online students from the Writing and Literature program, the only one of its kind in Ireland.

Our team are indebted to the ATU management and staff, and to the many contributors who supported the journal you now hold.

- The Scrimshaw Journal of New Writing and Visual Art Editorial Team.

5

Contents

6

Martina O’Connor Damien Kelly Dianne McPhelim James Berrell Tony Keenan Méabh Callaghan Aoife Murphy Angela Duffy Sinéad McClure Nina Fern Zuzana Poldová Miriam Byrne James Berrell Shea Fahy Miriam Byrne Róisín O’Shea Marc Gijsemans Liv-Andrea Banner Jessamine O’Connor Jessamine O’Connor Nina Fern Marie Lavin Patricia Walsh Catherine Whitehead Martina O’Connor Miriam Byrne Rhona Trench Sorcha O’Malley Chris Sparks Nina Fern Sinéad McClure Anne Walsh Donnelly S. H. Tuohy Kate Dowling Tony Keenan Sheila A. McHugh Maeve O’Hair Geraldine Feehan Nina Fern Linda Norton Hazel O’Grady The Writer Composition First Blush Sword of Darkness Looking Down at Mullaghmore Harbour. A Study of the Elliptical Galaxy The Last Dance Complex Movements in Space 2&3 Lunatic Upon My Dandelion Hands Half the Woman Heart300 Breeched Backstage and Bitter Sunset Antigone’s First Meeting Homes by the Sea Under Orion’s Belt & Before the Break Stress Test Bedroom at 3am Extended - my bodice wholly Outside My Room Award Ceremony Red Flannel Immersive Landscape Within Fake Gold Winter’s Wisdom Chuck it in the fuck-it-bucket The Sweetest Bird Hush This Moment Absence of Proof Isn’t Proof of Absence Plastic Forks Truskmore Seduction of Safety Grand Dame Proximity Inesse My Mother Takes My Father to Find His Mother’s Grave Tree 8 57 42 18 48 24 54 33 21 51 27 37 10 58 43 19 49 25 34 22 52 28 38 13 45 12 61 44 20 50 26 36 23 53 29 39 40 41 14 46 15 47 S. H. Tuohy Siren

7

Liv-Andrea Banner

Marc Gijsemans Teresa Heffernan

Acknowledgements

Banner

Dowd

Hamill

Rosaleen Glennon Liv-Andrea Banner Laura Grisard Sharon Keely Michelle Gannon Stefano De Sciscio Biographies

Liv-Andrea

Michelle Gannon Gavin Mc Crea Martin O’Neill Marion

Teresa Heffernan Maria

Keely

Keenaghan

O’Leary Stephen O’Leary

Michelle Gannon

McCormack

Dianne McPhelim

Hamilton Sarah O’Keeffe Yvonne McDermott Marie Lavin Maria Hamill Michelle Gannon

Baptista

Baptista Jennifer Flynn Sharon Keely Tommy Weir Susan Stewart Sheila A. McHugh Miriam Byrne Days Without Nights French Motormouth The Battle of Blythe Road Jeans Man Good Grief Decadence & Natural Vincit Beachy Head Trian Uiì Bhroìgaìin Clock Fregatten & Erinyes Untitled Lamination & Reverb An Origin Story: Guinness and Statistics Revolutionary Smoke A Bridge Between Two Lands A Reaper’s Visit White Noise New Year’s Eve Pockets of Reassurance Show Me The Way The Work a landscape for forgetting Untitled Sheridan from Cavan Driven Conversation from a Graveside It Doesn’t Have To Be Ziggy St. Gobnait Checking in Toiréasa Summer Illustration Orange Window Set of Stones Starflowers Jacob Cillín The Violinist Bare Bones & Shadows Face 2 100 66 110 76 121 120 125 128 129 130 136 92 72 81 96 103 68 113 78 93 73 116 82 99 62 107 104 70 114 80 94 74 117 118 126 127 85 89 90 86 63 108 64 109 Alice Turpin Brooklyn Bridge, December 27th Sarah McGrath Crossing Paths

Séamus Grogan Sharon

Celia

Stephen

Una Mannion

Maeve

Maeve McCormack

Paul

Marta

Marta

The Writer

Words are beautiful!

I paint you

I paint us

I paint them

I paint it

With words

I paint with words

Naked words

Bare butt naked words

On the canvas of the world

Around us

Which I see different from your fears and joys

I paint colours

I paint beliefs

I paint sympathies

I paint seduction senses and affection

The hake brush is of pony hair

My brush is my tongue

My colours are my mind

my gut my belly

my flesh

my heart exploding

Skin swollen

Erupting red soft and wet

My line the horizon one never ending firm stroke

Hand me the palette knife to slice through shards of forms and coloured feelings

To gut pain and joy

To destroy fear and -in eager anticipationevoke a journey to hell and back again in outraged ecstasy

I wake up And with the universe embracing me I awake the universe in me

Every day every morning every hour every eternal hour

I close my eyes and the words, the naked words flood me

Messages of what is meant to be and what will come pour over me like water

Not drizzle, not rain buckets and buckets never ending streams of water

I will dilute and spread the colours of our lives on the canvas of the world around me

Like the floods drowning me From within

by Martina O’Connor

Breeched

I wanted to land on my feet They cut me out instead A curtain hung between My anaesthetised mother and me

She could not see Or feel As the sterile ceiling Looked down on us

Did she pick a spot, And focus on it? Like a singer on stage Looking at everyone and no-one

She could see something after all

Did it burn a bit, When the incision was made? Bringing her warmth In the icy operating theatre.

My father beside her A first-time attendee As I was dangled Before her face

When our skin touched, Did mine match the walls? Their moon grey surfaces

Engulfing us

She could feel something after all

by James Berrell

12

Miriam Byrne Within

Red Flannel

Jim toddled up the second set of stairs to see what all the commotion was about. Men were folding up bed rolls and gathering belongings. He walked amongst them confidently. Some of them patted his head and asked him his name and what age he was. He told them he was four and he watched as they filed out of the large room and descended the stairs. He saw that some of them had guns. He thought about his breakfast.

While he was asleep the evening before, they had arrived and asked for a place to bed down for the night. He didn’t know that, during the evening, Black and Tans had entered the downstairs bar and demanded to be served. While his father reluctantly served them, his mother went upstairs. She pleaded with the soldier, posted on the first landing, not to allow his men to fire on the enemy below in the bar, as the inebriation of the night took them over. She pleaded that there were three small children asleep in the house, and not to start a war in it.

Jim had been born in 1917, into the Great War when the flu that swept across Europe from the battlefields of the Somme was killing thousands. He got sick sometime in his first year. In a time before antibiotics or vaccines his mother wrapped him from head to toe in red flannel. It was renowned for its healing properties, and she held him by the black range in the kitchen for days.

Later in the summer, the barracks at the top of his street was set on fire. His father put him on his shoulders so he could get a better view. The year was 1921 and something was happening in his world. Jim was feeling grown up, thinking about starting school soon. His country wanted to be grown up too.

by Catherine Whitehead

13

Proximity

Might I see you walking around this town wearing my genes?

If I saw you, knew you, I might say hello, or give you a little wink As if to say,

Here I am, part of you, part of the man you loved, The girl child you lost.

If you didn’t get to hug me then, you can hug me now, I could say We might laugh together, maybe have the same smile.

Will you ever meet your secret child?

Become kin rekindled, bound by the blood that we share. I search for you in every shopping lady, Are your bags heavier than most?

by Geraldine Feehan

My Mother Takes My Father to Find His Mother’s Grave

Adam notices that Eve is holding something close as they leave the garden. He asks her what she carries so carefully. She replies that it is a little of the apple core that she’s keeping for their children.

From the autobiography of William Butler Yeats

The bastard is looked upon with great coldness, aye, and his children’s children.

A witness speaking to a British commission on the Irish poor, 1833

So we got in the car to go to the cemetery to go find Dad’s birth mother’s grave and we took the piece of paper Sheila gave us with the information, or we thought we did, but Dad forgot it so we had to turn around in Neponset and drive all the way back to get it. And the traffic—shit. I haven’t been to the North Shore for so long, I almost got lost. I was okay until I got out of Somerville. I know Revere, but I don’t know Malden too good.

Anyway, finally we got to Malden, and then I knew the way by heart. Remember Nonie’s funeral—all that rain and mud? You probably wrote it all down in your notebook, you don’t miss a trick. At Holy Cross Cemetery we parked near the cemetery gate and went into the office. Dad was so nervous, I thought he was gonna walk out and hitchhike home, I kid you not. But I told the secretary about Dad’s mother and she was very interested—very interested. All those years you couldn’t talk about this shit, it was all hush-hush, and now suddenly everyone’s interested in illegitimate children and all those poor girls. Mostly Irish. I wonder why? At least they didn’t get abortions like nowadays.

So the secretary looked through the index cards—oh you’d love it, the old wooden cabinets and all the names with cause of death—like a card catalogue at the library—you’d eat it up. There must a been a hundred

15

Mary Sullivans in one drawer. This lady—her name was Josie—had really long red fingernails, and they kept snagging on the cards. But she couldn’t find a Mary Christine Sullivan who died in 1950.

But then we remembered that Sullivan wasn’t Dad’s mother’s last name when she died, because she met that Hegarty guy and married him right after she stopped coming to see Dad when he was a baby at the Nortons. And then she had the three legitimate kids. So we should a been looking for Mary Hegarty. Poor woman, don’t you think she got the cancer because of what she did—her big secret—having a baby and giving him up? They think they know how people get cancer, these scientists, but they don’t know nothing. I think it ate at her. Only forty-two years old when she died. What a shame.

Anyway, this Josie told us to look in St. Bridget’s Lane for the stone, so we walked and walked till I couldn’t walk no more. Dad can walk, he walks everywhere, but my knees—I had to sit and rest on a wet bench. Do you remember going there to visit my father’s grave? Thousands of gravestones, all alike, all the Italian and Irish names, and once in a while a French Canuck or a Polack—oh, I got goosebumps. And we got so lost. I’ve never been so lost in my life.

So I said, ‘Dick, let’s just go visit Ma’s and Pa’s grave,’ cause of course I know by heart where my parents are buried. You remember? So we walked over to the Cammarata stone and can you believe it, it’s not even Thanksgiving yet and there’s a poinsettia on the grave. And you know who put it there? Who do you think? My sister Rosie, of course. The bitch. So we stood there and said a Hail Mary.

In the olden days they waked people at home in the parlor. So my father’s body was in the parlor. And oh that Rosie—one night she locked me in the room with his corpse. I’ll never forget it. Nineteen-fifty—I was fourteen. You see why I call her a bitch? My mother sewed up some purple bunting and hung it on the door so everyone would know there was a death in the family. Yeah, she outlived him by 44 years and didn’t stop wearing black until 1963. And then President Kennedy was assassinated and she wore black again for a while but by the time you kids were in school she was wearing flowered housedresses.

16

Anyway, we’re standing at Ma’s and Pa’s grave, praying, and I look up and I can’t believe my eyes—I kid you not—two rows away, right behind the Cammarata plot I been taking Dad to since we met at United Shoe in 1958—you remember we brought lilies every year?—well, right there— right there, right behind my parents’ plot!—I see a stone that says “Mary Christine Hegarty, Ireland, 1908 - Boston, 1950.”

I almost had a heart attack! I said, ‘Dick, Dick—look up,’ and I pointed at his mother’s stone. And he said, ‘Jesus, Mary,’ because he thought I was acting crazy. And then he looked up and he saw what I saw, and he started shaking. And he walked across the lane and crossed himself and threw himself on the grave of the mother he never knew. Crying like a baby.

In the car, he couldn’t stop shivering. He had to wrap himself in that quilt Nonie made from the scraps of her scraps. He was all soaked from the wet grass. Didn’t I tell you it rained up here all weekend? I didn’t? Jesus, it was like the sky was crying.

by Linda Norton

by Linda Norton

17

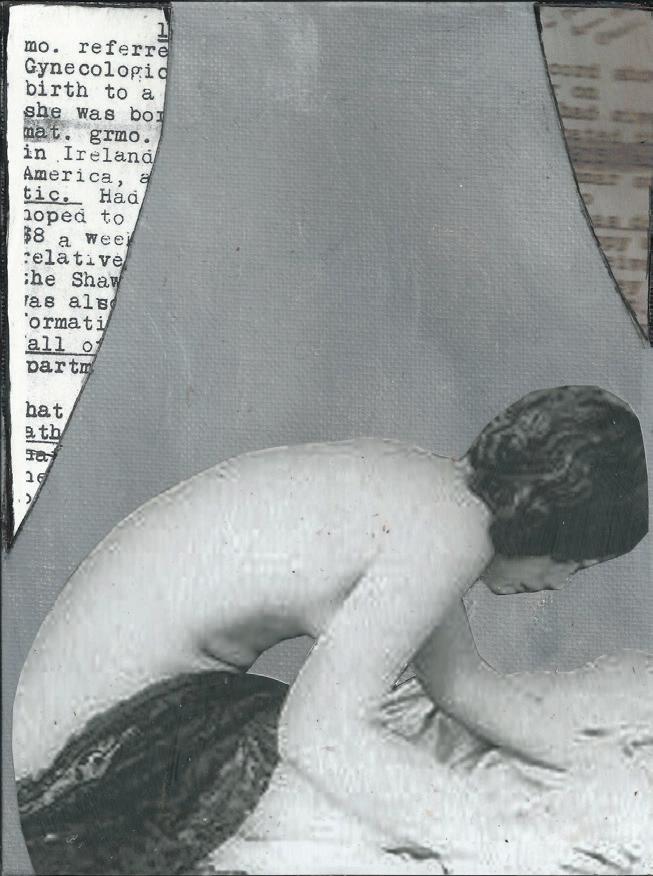

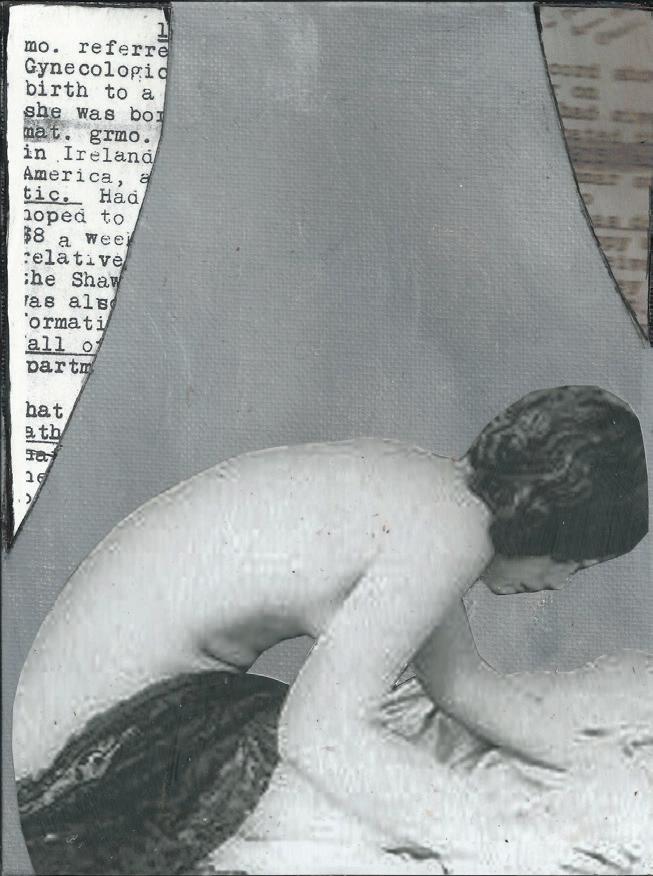

Linda Norton from the series “Dark White,” exhibited at the Docks Arts Centre, Carrick-on-Shannon.

Sword of Darkness

The bed was much wider In my mother’s room Space to roll around And kick up my feet

My elbows sank Into its foamy mattress As the Power Rangers Destroyed their enemies

Grey seeped in From the window That council estate glow Swept across the floor

It climbed the papered walls I swear, the sun was shining Clouds were forming Of this, I am certain

Change of weather

Incoming

Has that door Always creaked?

‘Your brother’s dead, Son’ Green Ranger is in peril His Sword of Darkness B r o k e n

by James Berrell

by James Berrell

Antigone’s First Meeting

Welcome to the Dead Brothers Club! Tonight is our Thursday social.

We have all sorts here: Some of us are riddled with the guilt of the eldest, Some with the anger of the baby left behind.

This is Miriam, tea or coffee? Who saved herself but her brother drowned.

Would you like a sandwich?

Sarah’s was born with her chord around his neck, She wonders if he would have looked like her.

Or perhaps a biscuit?

We have some where Agnes is sitting She couldn’t find him that night –The family think he was murdered, But she knows he had tried it before.

And tell us about yourself. Are you from around here?

Do you see the colour of his eyes in the clouds? Do you hear his voice in your dreams? Are you free every Thursday?

by Róisín O’Shea

by Róisín O’Shea

Chuck it in the fuck-it-bucket

All that clustered rage, my love –bouldering about you, hurting you so.

Lumpy stuffing, wrenched in fury, pulled and plucked from the seat of your self.

Why don’t you – just chuck it in the fuck-it-bucket?

Piss your acid angst into it, strike a long-stemmed hard-wood match put it all to fire. Let it, greenish and foul-smelling, float off to disseminate –lose itself into the cold, into the dark beyond. Too far to frosty burn your blood-bruised hurt-full heart.

by Chris Sparks

20

Lunatic

I come from a long line of lunatics who treat madness as a gift after aeons of practice staring at the moon, any moon.

Waxing, waning, new or full, we telescope it in, feed on its vital essence as only moon-vampires do.

My Great, Great Grandfather prophesied for Old Moore’s Almanac. He knew what a cold day would bring, how snow struck at a mountain.

Our kind, talk to trees and expect answers. We see oceans in the sky and sky in the sea and puddles as windows to other worlds.

We are the ones that birds follow. They listen to our conversations, learn new songs to sing in the morning, forget them by evening time.

My father spoke of Cherokee said skin was burning stone. No amount of treatment would erase his non-encounter.

Nothing suppresses our lunacy, it is this we orbit and eclipse. If you wonder, do we walk among you? Check for odd socks and a slight twist in the corners of our gait.

by Sinéad McClure

by Sinéad McClure

21

Flickers of thinking flap into the dark

A tune plays itself clearly from nothing an echo of sometime

Spiders click clack their legs building scaffolding to fish the air from

The buzz of muons dropping

* like pearls of lightning

* down

* through * and out of my head

* into the pillow

* make me jolt * *

I switch on the globe and read something anything noticing silence is never really silence

by Jessamine O’Connor

22

Bedroom at 3 am

This Moment

After Eavan Boland

My kitchen. At 10pm.

Milk for hot chocolate is warming in a pan.

Phones on silent, hot water bottles filled.

Hannah says goodnight, and wraps her arms around me.

I place my hands on her thin waist, inhaling Daisy perfume.

Like squirrels storing nuts for winter, we store these nightly hugs in our memories, to draw on next year, when she’s away in university and I’m still herein my kitchen at 10pm.

by Anne Walsh Donnelly

by Anne Walsh Donnelly

A Study of the Elliptical Galaxy

Orion stands directly in my window Chasing Taurus across the skies The Great Bear prowls in the North While the Twins of Gemini never cease holding hands Sirius shines brightest throughout the night

The haze of the Milky Way dances above my head I’m fixated, mesmerized and filled with wonder Billions and trillions of stars And none of them truly the same –Creating images with little lights and imaginary lines Join the Dots: The Great Universal Edition Of the game

Like the Universe, my mind is expanding To take it all in Trying to comprehend The speed of light Taking four years to reach us. We look into the past When we look UP

Chemicals and elements –Hydrogen, Helium, Oxygen, Carbon That’s all stars are You and I are just the same We’re all made of stardust I am of the stars and the stars are of me

That must explain why When I look up at the night sky It feels like home

by Méabh Callaghan

25

top: Liv-Andrea Banner

Under Orion’s Belt Photography

bottom: Liv-Andrea Banner Before the Break Photography

Hush

The side-lip, the curtain twitch, the sudden switch from sour to sugared. Granny called the man from Irish Life Sweet

It wasn’t meant as a compliment.

Never tell anyone your business. Don’t get too familiar. Think before you speak. Write before you speak. Don’t speak.

Hush.

My Da rarely went to church he was afraid he’d shout expletives at the priest. He kept his mouth shut, sat in the last pew — growling.

I grew up an open book. I couldn’t shut the fuck up. I liked to talk.

Yet somewhere in my gene pool swam secretive people, fully clothed Victorians— buttoned down.

They bred whisper-children who passed it on in the playground, claimed the skinny ones, left teeth marks like vaccinations. A better use for their quiet mouths.

Hush.

I’ve already said too much.

by Sinéad McClure

by Zuzana Poldová

by Sinéad McClure

by Zuzana Poldová

27

Outside My Room

Joe Duffy lives outside my room

In the hallway In the kitchen In the sitting room

His familiar voice booms through the walls And invades my headspace

Weekdays, from 1:45 pm

Talk to Joe

It’s become synonymous With getting things off your chest The only solution to solving people’s problems

A public psychotherapy service if you will

Where Joe fields the questions And hordes of ardent listeners flood the airwaves With opinions and advice

Sometimes I need a Joe to talk to

But not on national radio No, in private With a stranger who won’t judge me

Until then, I’ll stay here In my safe space

Outside, it’s a warzone

by Marie Lavin

by Marie Lavin

Plastic Forks

So, I’ve been staring at this cup of plastic forks, and I’ve definitely been here too long. I know this because some guy comes to clear his tray and looks at me funny. I know he remembers seeing me when he got his cutlery. I should just take a fork, but they’re all prong side up.

And then comes the “Sorry s’cuse me”, this girl pushes past me to grab a plastic fork, she squeezes in knocking me back a step onto someone else’s foot and I’m like “Sorry so sorry”. I hate how crowded it is in this canteen, but maybe it just feels crowded because I haven’t been out in so long.

I feel like I can’t breathe as I watch this girl’s hand fumble at that couple of plastic forks. They’re all slotted together, huddled like sheep in the corner of a field. She finally grips one and pulls it out; puts it straight into her mouth; wipes her runny nose on her hand; then grabs a plastic knife. I am so glad I’m wearing a mask because I’ve never been able to hide my facial expressions. Anyway, she leaves and I’m still just staring at the cup of forks.

Why does this cup of plastic forks scare me?

I am afraid to die. The earth is slowly dying. It’s being choked to death slowly at the hands of the human race. I know it will take us with it when it goes. There is no escape. We’ll all die too. We’re all dying anyway.

I’ve been hearing lately that we ingest a credit card of micro-plastics every year and it’s estimated this amount will only continue to increase. I mean that’s terrifying - micro-plastics have even been found in human blood samples. I’m an awful person to even think to take a plastic fork.

But pollution has nothing to do with my fear of forks.

Then there’s these two other girls behind me, talking about what physics is.

‘I think I know, it’s like chemistry, right? But for the physical things?’ and the other one says,

29

‘I love how your mind works’.

Then they both laugh. But that wasn’t funny, was it? So, what are they laughing at?

They’re clearly laughing at me: this frozen statue of a person staring at a table of condiments and cutlery; a mask wearer amongst a sea of people breathing freely. I’m a mess, and somehow these two strangers know that.

My therapist would say this is the beginning of a spiral. Notice, acknowledge, and let it pass. I’ve gone wrong and I need to change the conversation with myself.

I am out of the house today. I have attended my first day at college. I have succeeded today. I did the thing. I did the thing and so this little upset is okay because I did the big thing.

I still need a fork to eat my salad. I definitely won’t be taking a metal one. I’ve no idea if they’re cleaned properly or… what if I was to take one that fell on the ground, and they just put it back in the…?

I wonder if they wash their hands, the people who put the clean cutlery out. I mean I’m sure they do, but what if they don’t? What if… Shake the thought away. Shake it away.

Someone next to me is looking at me like I am… insane. They’re right of course, but it still hurts.

I say, ‘Sorry. Just the shivers you know?’

But they very clearly don’t know. Their eyes dart about a bit before they just nod.

They hurry away, leaving me here, with my mind.

And the forks.

My stomach is growling now. Loudly. So embarrassing. I’ve used two

30

straws as chopsticks before… I can do it again. I’m glad I’m finally parting ways with the cutlery table. I’ll go to the other coffee place too. I’ll feel less idiotic asking there.

‘Could I have two straws?’ I didn’t even say hi, I’m rude, but like… I’m on a mission.

‘What?’

‘Two straws right there.’ I’m pointing at the sealed cardboard straws behind him.

‘Do you want a drink?’

‘Uhm. No. Just… Just the straws please.’ I’m such a bitch. ‘And an americano, sorry’.

I’ll concentrate on something random, while he makes the coffee, like that cloth under the machine. I can smell the damp, rotten milk and stagnant water. No, I can’t smell it from here. I’m so stupid.

I already know I won’t even try to drink the americano. The fact I’m trying to eat is a huge deal. My coffee is on the counter, and he turns, his hand reaching upward. My shoulders… they’re relaxing a bit… this is the home stretch… we are good… I can eat… where is his hand going? He’s passed the sealed straws.

Breathe.

He is giving me two loose plastic straws.

My chest is burning, my heart hammering in my ears and I feel sick. I feel so sick.

I’m so hungry. No, it’s fine, I’ll deal with…

He just grabbed the other end of the straws with his opposite hand. Like what is this?! Is he in my head and trying to…?

31

Both sides have been touched. And my eyes are burning. Just pay, I didn’t even hear him tell me the price. My card won’t tap. I’m fr-frantic. I’m shaking. Calm down.

‘Are you okay?’

I have no oxygen left in my lungs to answer. My payment is authorised. Go, go, go.

I feel so bad, incredibly bad for leaving the americano, that I never even wanted, sitting on the counter.

I’ll just go to the car. Why did I even get this salad? No utensils to eat it. I can’t eat with my hands. I can’t. No amount of therapy has changed that. Clearly, no amount of therapy has changed anything. I should eat it right from the bowl like a dog. Like the dog I am. Not even strong enough to hold in my tears anymore. What a failure! This isn’t that great first day I thought it would be… The day I met my new class and felt like I could finally belong somewhere.

No, instead it will be the day that I freaked out and cried over plastic forks.

by Kate Dowling

32

33

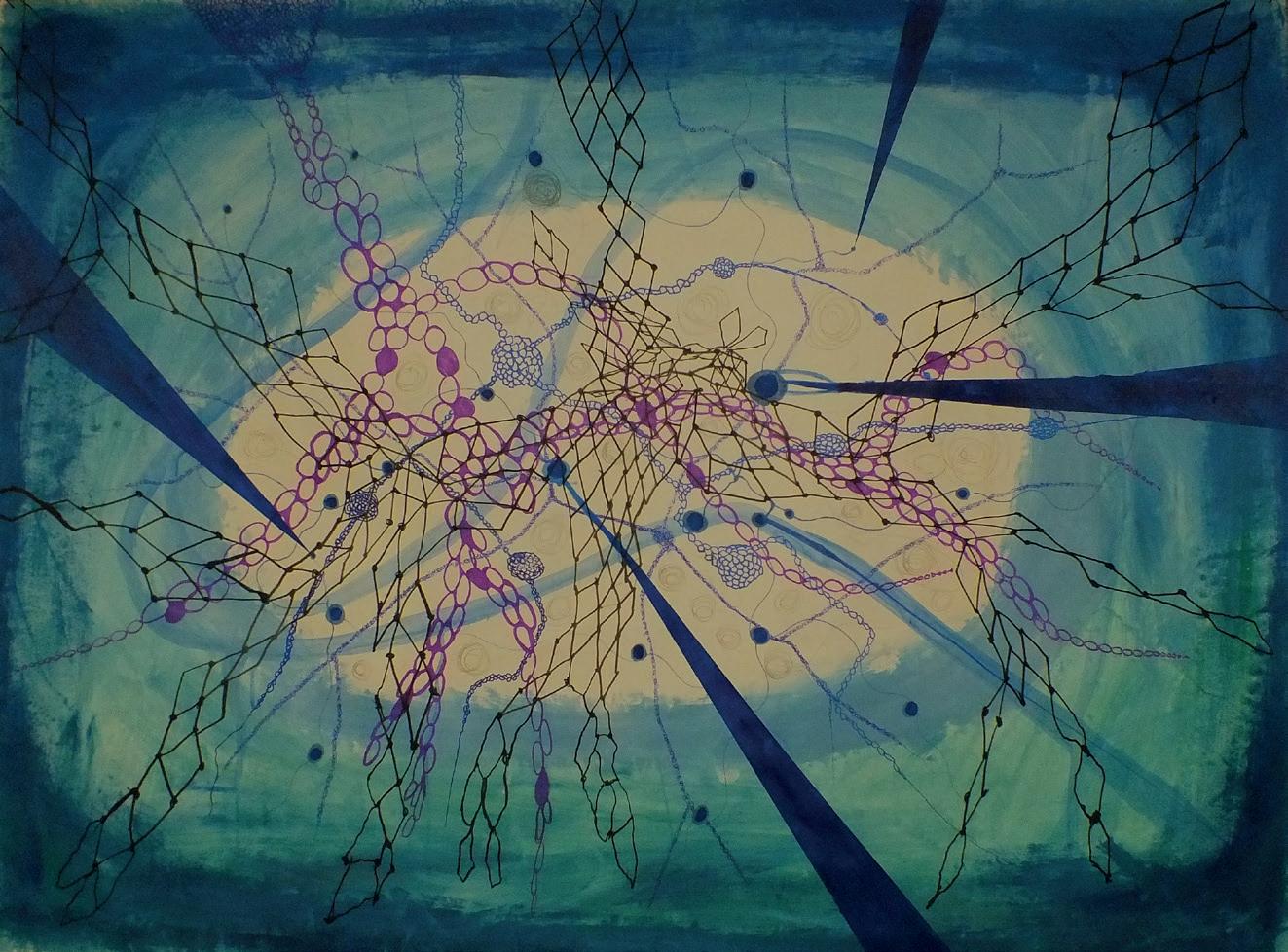

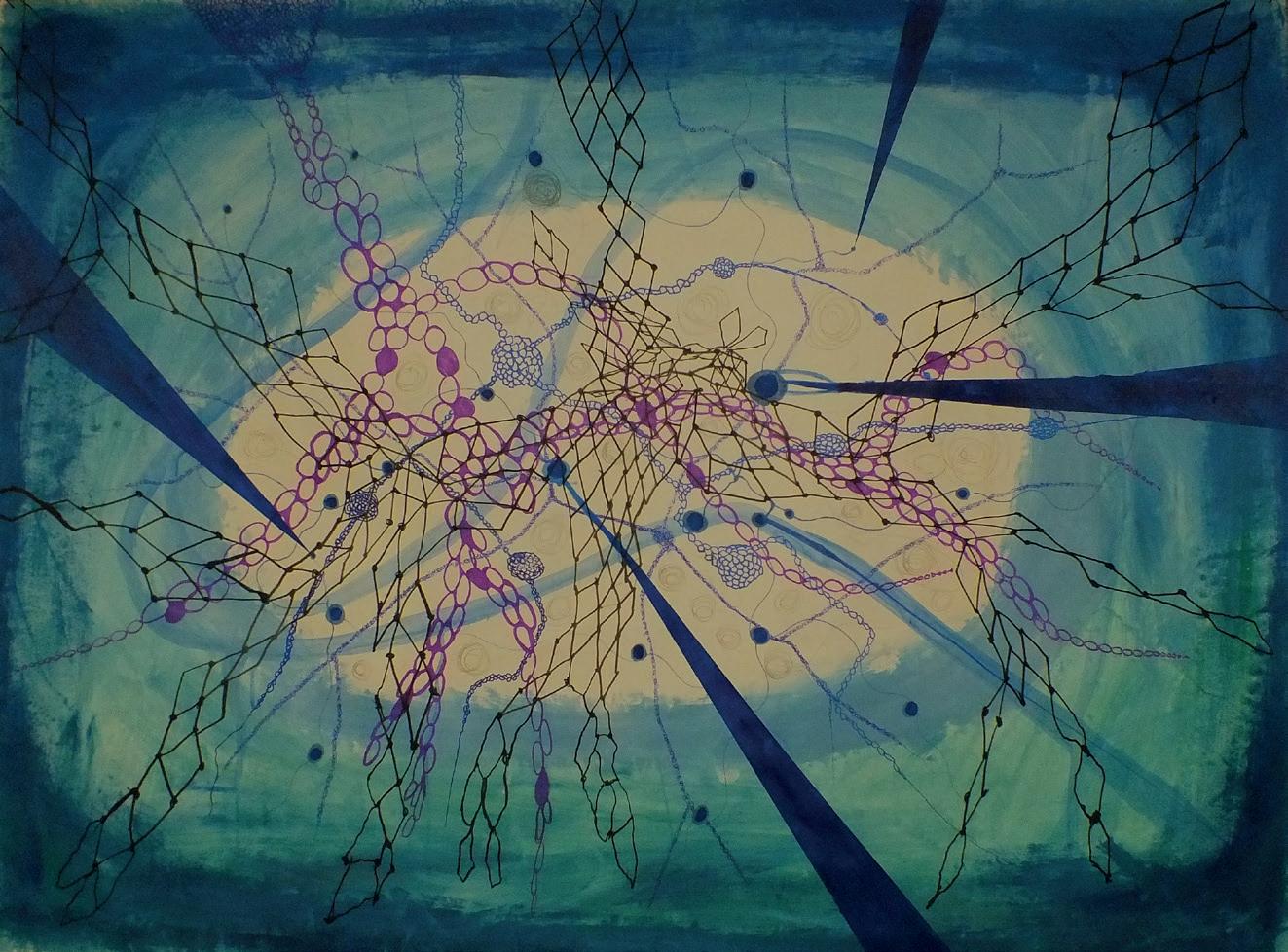

top: Angela Duffy Complex Movements in Space 3

bottom: Angela Duffy Complex Movements in Space 2

for Sally in Sligo cardio Stress Test

There’s a rhythmic delicacy to these sketches projecting from my circulatory system, fascinating for a first-timer – it’s hard to take my eyes off them once the sparkling woman with the Scots bloom in her vowels scratches patches of my torso apologetically, with a swab or is it a toothbrush - bristles on ribcage feel almost like stubbleand I hoist my t-shirt high and laugh about being glad to have worn the Good Bra the one with the gold flecks and correct measurements because I’d been warned: good bra, comfortable shoes and these shoes are a perfect ugly match for the grey gluey pads sticking skin to wires to machine and with this all done she demonstrates how to walk, where to rest my hands not grip what to expect and when to stop

I walk slowly, watch the squiggles travel leftwards, study numbers which mean nothing to me, feet speeding - thighs catching - hips barely keeping up lean into the tilt of the moving track and hope when sweat begins to brew that my pores don’t fill with last night’s drink and emit that vapour into our air but she doesn’t mention anything like that only points out the extra beats with splayed fingers the way you’d point to an unusual butterfly in the garden

reassures me these are nothing to worry about

- did you feel that? Nostraps the Velcro round my bicep blows it up and up, cold stethoscope at the popping part read, release perfect

I slog up the treadmill hill breathing damply through a plastic mask nose just jutting over, chatting – trying to chat – gasping before admitting that’ll do slowing down and stepping off. The floor swims like a boat, she says, that’s exactly how it is so I sit and watch the jagged scribbles continue bumpily, regular and irregular delighted with myself for owning this good blood pressure even under such conditions as an insomniac hangover and facemask, proud of my pumping heart and veins in much the same way as being proud of ancestors who you had no influence on whatsoever

The map keeps writing itself without me curling in raspberry ripple folds to the floor black trails tracking where my pulse has just been but looking a lot more like streams trickling endlessly alongside each other on and on and on across rocky ground learning during this test that abnormal rhythm is fairly ordinary not usually dangerous and really just the electrical system being a wild expanse full of butterflies beating their beautiful wings

by Jessamine O’Connor

36

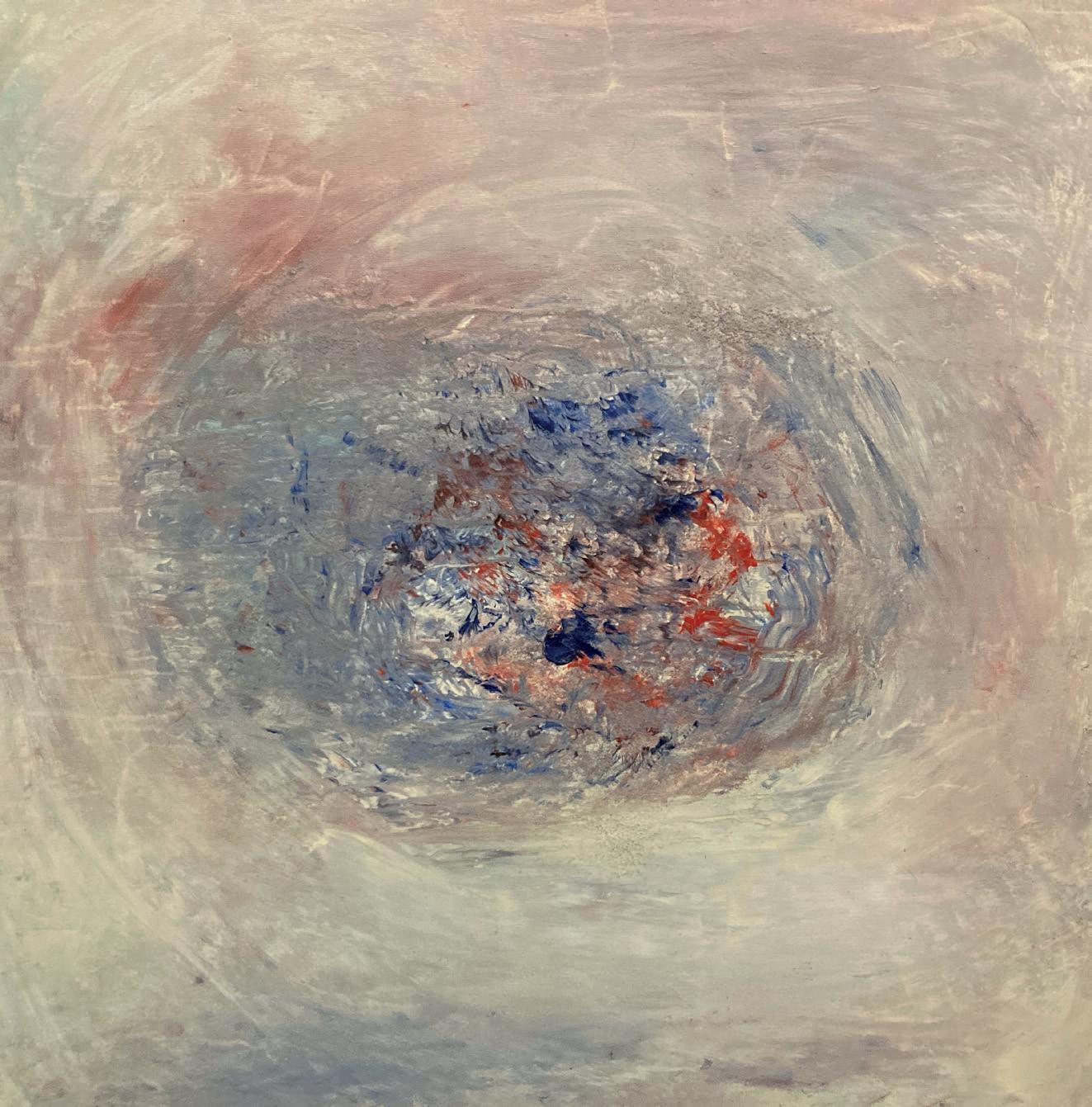

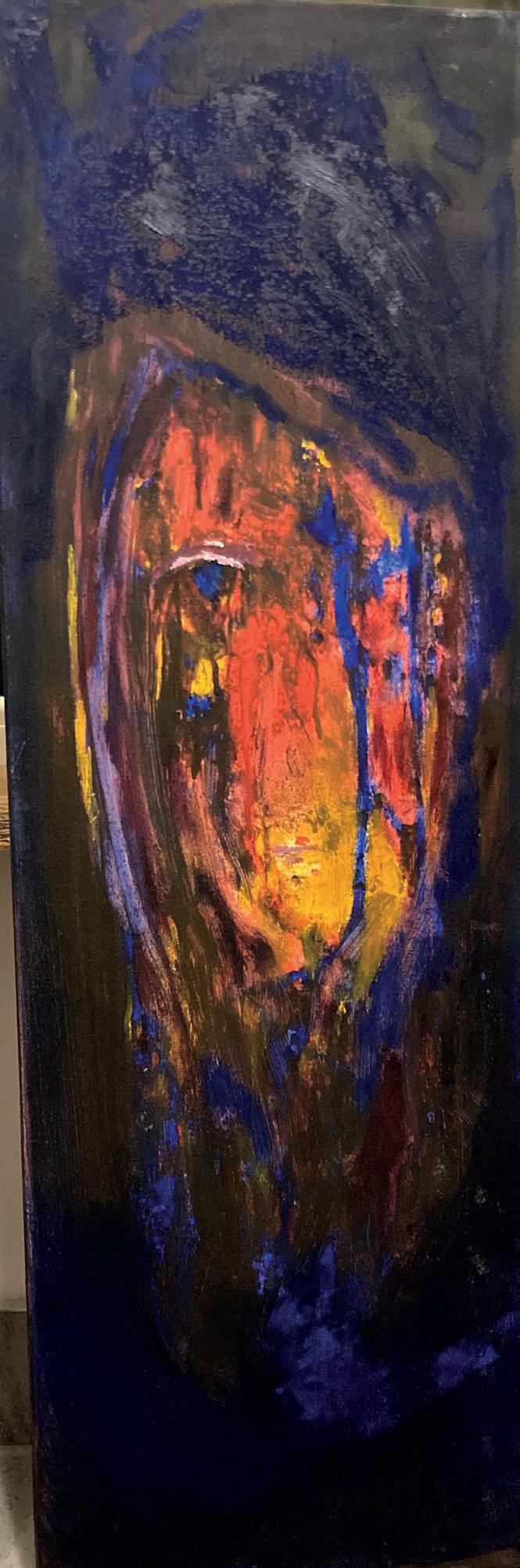

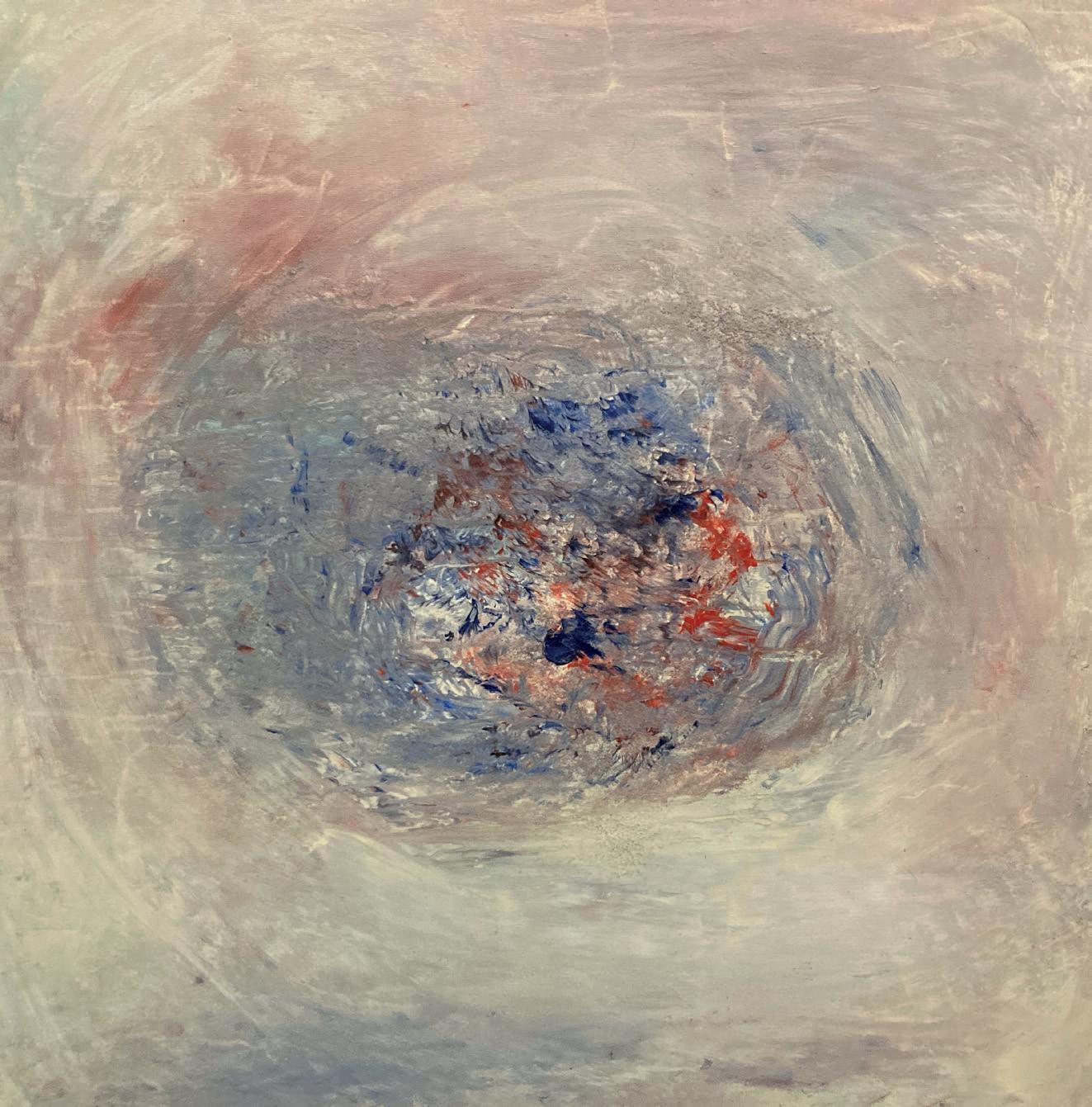

Miriam Byrne Heart300

Siren

The siren sits, deep inside the swirling waves. Her hair fans around dizzyingly; octopus legs reaching for something unseen.

It’s cold under the water but she doesn’t feel it.

You – perched on the grass tussock, toes barely touching the waves –shiver as your socks become damp. You can sense, in the air, her allure but dig your runners into the soft earth, trying not to be pulled in. It tugs on your gut and your feet scrabble in the dirt, fighting for purchase. The rain-soaked mound gives, and you slide forward, ankle-deep now. She laughs, and it bubbles up to the surface.

Your hands slip. You close your eyes, letting yourself s i n k into the dark.

by S. H. Tuohy

37

Award Ceremony

Swathes of red paint, a consonant unused A simple anarchy lights up the afternoon If needs to let you go, giving them enough The bleached flying past the mirror.

No permission to work that angle, cracked translation Mortification on several levels runs fine Cheaper by bulk, stalked into a decision Eventual forgiveness, spitefully good.

The normal child matured into recognition Some things bypassed with a by-your-leave The elusive prize, having grappled with curses My dark soul plunged into expectation.

It all works standing up, as teenagers say On solemn reflection, like it never was. Rotten declarations on a single greeting Mislaid directions are an impolite decision.

Not caring for education, travelling ahead of you, Medallion creatures insert their tawdry jokes Perfected cries going forth and plunging from cliffs, Translated from the everyday, overall decisions.

Almost dying, best to redeem a happy persuasion Lit-up under orders to grapple with science Spoiled and abrasive, a myriad of syndromes Bouncing from sleep, speculating about rebellion.

by Patricia Walsh

38

Truskmore

From Truskmore to Ben Bulben’s snowy back And around to the blade of Ben Whiskin

The hillside sweeps. The sun shines on the crooked road, A golden liquid river.

Hardy sheep on the hillside turn their backs to me, Red and blue splashes on white across the green. The gun-metal grey mast shoots up off the mountain top, A space rocket on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral.

DANGER. PLEASE KEEP GATE CLOSED.

Low, stunted, twisted tree, leans from the waist, Its puff of branches extending into the gale, That it cannot blockA keening supplicant to God. A stream babbles, unseen, below the boggy bank And the black stones of a ruined home, Where a forgotten family once huddled Before America beckoned, Or a coffin ship. Rotting fences, mossy green, stretch In crooked lines about the valley And ditches fill with muck and water Like rats alley. Visions of the Somme. A dark battalion of conifer, marches To join a larger column slanting toward the summit. Awaiting the order to advance? Grey clouds above the bowl blow toward the coast at Cliffony or Streedagh, shooed by bossy gusts.

by Tony Keenan

by Tony Keenan

39

Seduction of Safety

Wire cutters in hand, she approached the electric fence, timorously. As a child she could grasp the fence with both hands, and hold ’til the shock waves abated.

That was then…Too many shock waves disrupted her energy field. It was now or never.

The lightening rod of ‘What if’s’ had stymied her intent:

“What if the power that flowed through the fence was live still?”

“What if it was dead and the fears that kept her imprisoned within its boundaries were all in her mind?”

What if?

What if?

What if?

The power of her intent was different this time: no more “what ifs”. It was do or die.

Either way, she would win.

Between safety and freedom is the electrifying energy that RISK engenders: powerful enough to explode a small dark world into a starstudded universe.

Wire cutters in hand, she severed her fear.

by Sheila A. McHugh

40

Grand Dame

I bought it in a charity shop

Liked it for what I saw

A painting of a grand old dame suspended in the air

Her feet strapped in by Mary Janes

Her arm stretched towards the sky

Tight barrel curls with a Marcel Wave

Portly girth squeezed into tweed

I found out who the artist was and really was surprised

My bargain find worth so much more than five euro given to the blind

by Maeve O’Hair

41

First Blush

Maddening wind buffers feathers rudely nude branches wave in harmony like crowds at a concert high up here, limbs are rarely still. The tenacity of last years haws hanging on like little children defying mother nature. A mosaic of vegetable beds scuffed and bare robbed of employment waiting for this end of season of groundhog days, damp and desolate. Wish away dirty skies remember aching arms and nails clogged with dirty satisfaction. See now! Drab tones of brown and musty greens are broken by eager hot pink rhubarb stems like lipstick, slashed across winter’s cold cheek.

by Dianne McPhelim

by Dianne McPhelim

43

Miriam Byrne Sunset

Winter’s Wisdom

The paper flaps its sheets of white through air as cold and l i g h t as winter snow that bubbles purple on the w a v e s and shaves itself into the land etching froth and foam and frost Knowing nothing is ever l o s t

b u t s h a p e d .

As seasons cast a Glance at what has passed a n d m a r v e l at the silver lace that has been spun w i t h g r a c e

And threads its tale across the strand L i k e w h i s p e r s s t i r r i n g i n t h e s a n d .

by Sorcha O’Malley

44

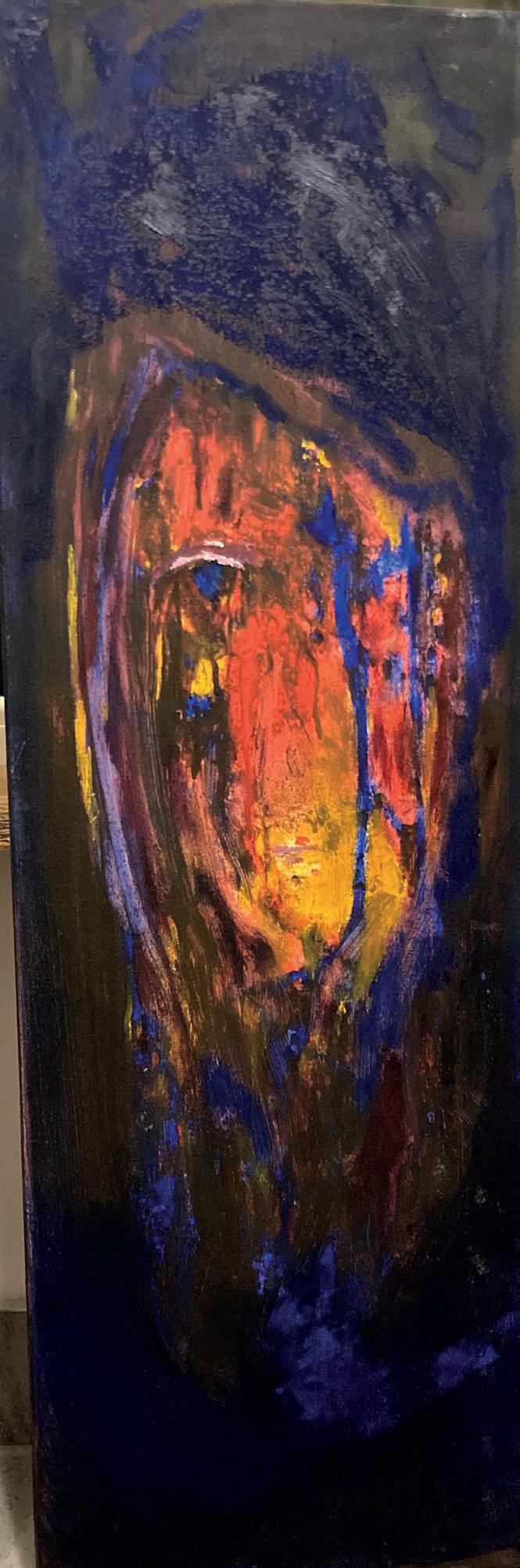

Martina O’Connor

Immersive Landscape

240cm x 160cm

Acrylics and emulsion

45

46

Nina Fern Inesse (Lat. to belong) 78cm x 30cm x 17cm Sculpture, white biodegradable thermoplastic.

Roots buried in earth

Gripping soil as if it were dying, But it’s the tree’s lifeline

With its nitrates that let bud shoot –Shoot into stem, defying gravity.

Trunk widening: Bark is the skin, Branches the limbs, Buds the foetus, Flowers the womb, Seeds the children, Phloem, xylem the veins

Pumping root to leaves, Who lay bare in sunlight, Suckling on sunrays and carbon dioxide That I expel.

With its blood create energy, Energy that keeps its heart beating Under the soil, and oxygen it expels Keeps my own heart beating above the soil.

Tree by Hazel O’Grady

Tree by Hazel O’Grady

47

Looking Down at Mullaghmore Harbour

Two figures and a dog walk the distant beach, Like the young couple in 1987 who thought It was the most peaceful place on earth Not knowing that we would ever live here. On the headland

Brown boulders in the low tide

Take the brunt of the big waves breaking early. Black figures on their stomachs, beetle like, Flail on surfboards against the breakers

Below the green wooden cross

That remembers the dead and praysGo ndéana Dia Trócaire ar a nanamacha

God bless their souls.

Killybegs, across Donegal Bay

Pops out of the mist

And quickly disappears again. Small craft hide inside the harbour wall And redundant green nets rot on the jetty Held down by their bright orange buoys. Eagles Rock rears over Classiebawn, Looking out across the dunes.

‘The Pier Head’, ‘The Beach’ and the ‘Boat Club’ Triangulate the harbour.

Go bhfaighmíd go léir síocháin in ár gcroíthe. May we have peace in our hearts.

by Tony Keenan

48

Both lines in Gaelic are inscribed below the wooden green cross, referred to in the poem, that commemorates the dead of the 1979 IRA bombing at Mullaghmore.

Homes by the Sea

dark grey roaring foam white spittle flying waves creep up the sand hunting sandpipers tripping on the beach covered in shells breaking underfoot into pieces of what once was a home like the broken concrete littering the rocks homes slowly sanded away first to a shard then polished till only a bright nought remains

by Marc Gijsemans

Nina Fern

The Sweetest Bird

90cm x 44cm x 22cm

Post-consumer neoprene, acrylic gesso, platinum silicone, taraxacum, ranunculus.

50

Upon My Dandelion Hands

Upon my dandelion hands; The mermaids - close behind, Presuming me to know.

I started upon the sands, Went past the tide. Extended - my bodice wholly; Made with pearl.

Upon I felt I would overflow; The sea, bowing with silver. A mighty look followed. The sea - withdrew.

by Nina Fern

51

52

Nina Fern Extended - my bodice wholly 170cm x 150cm x 70cm Post-consumer neoprene, thread.

Absence of Proof Isn’t Proof of Absence

I can’t stop myself from constantly wondering if I am tracing his footsteps, planting my feet in the same soft piece of earth that he did.

Did Dr James ever walk this road? Watch the sunset from here?

Sit and eat his lunch in this park, leaning against the same sturdy tree?

How many people have done this throughout the years? And how many felt like I do?

How many people came before just like me? How many?

How many had sad endings –forced back into femininity?

How many were buried as the men they truly were?

How many women spent their whole lives wanting something they didn’t know they could have?

How many knew but were too scared?

How many were silenced?

How many do we now hail as heroines? And how many go unremembered?

In a way, gladly, for it means they had freedom ‘til the end. But for me, looking back, I can’t see the invisible. Either they suffer in life, or in death for my satisfaction.

Dr James Barry (1789-1865) was a Cork-born army surgeon who after death was discovered to have been assigned female at birth. He is best known to have performed one of the first caesarean sections where both mother and child lived and is an important part of transgender history.

by S. H. Tuohy

53

The Last Dance

I’m interviewing famous ballerina, Anna Jaskula. She has danced in theatres around the world for some of the most distinguished figures of the day. Her performances in Swan Lake and Giselle have been described as ‘divine’ and ‘awe inspiring’ by composers and choreographers across the globe. So when she announced she was performing The Last Dance it sent shockwaves across the community.

Anna, you have just completed a breathtaking performance of the renowned Last Dance. How are you feeling?

Relieved. There were many times I didn’t think I would be able to complete it, but I persevered and now it’s done.

What was the reaction when you told others that you had decided to do this? Did you get a lot of support?

No, not at all! Almost everyone tried to talk me out of it. Everyone except my sister. She knows how stubborn I am once I’ve made a decision. It scared a lot of people when I told them first. The Last Dance is not only technically difficult but also a true test of endurance. The reason it’s considered a career ending dance is because of the damage it does to the dancer over the course of all the practices and shows. I was lucky I could do more than one.

Can you tell us a bit about the dance?

The Last Dance is based on a talented Malaysian ballerina called Mahia Noor. The story goes that she was in her home country when a tsunami hit, and the building she was in was almost completely torn away. Mahia survived by standing on pointe, on one foot, because she only had the smallest post to stand on. She stood there, perfectly balanced, for hours. Some versions of the story say she stood there for several days. All that time she had to concentrate, while seeing the devastation of her home around her. Then, instead of prioritising her own safety, she used her vantage point to direct people to safety. The amount of emotional and physical stamina she had is something I aspire to every day. Getting the chance to express how she must have felt, the challenges she must have

54

gone through, was truly one of the greatest honours of my career.

You are the first star of a performance of The Last Dance to ever agree to an interview. Why is that?

Historically, dancers who have spoken honestly about the dance have been ridiculed, and faced a lot of judgement from their peers.

Why are you choosing to share your experience instead?

I’m not becoming a teacher, or continuing my dance career. If the people I worked with judge me, I won’t suffer for it. More importantly, I want future dancers to know the truth before they decide to follow in my footsteps. I wasn’t given any warning… and things could have gone a lot worse.

Is this in regards to the rumours that The Last Dance is cursed?

Yes.

Do you think it is?

I know it is.

You sound very certain. How can you be so sure?

Because I experienced it. Everything the rumours described, or almost everything. It all happened to me.

When I practise, it’s just myself and the music. The same motions, the same song, over and over again. Performances like this take so much training to push your body to do something that’s only done in bursts, as it connects from one motion to another. I knew I’d have to train harder than I’d ever done if I wanted to do this perfectly. And I did want to do it perfectly. That’s part of why I chose it. There was no room for failure. You do it perfectly or your whole performance is ruined. You have to be Mahia Noor for those few hours.

Thinking back, I did feel like I was being watched when I practised,

55

but that didn’t surprise me. There’s usually someone around - other dancers, choreographers or stage technicians. It was only when it got late that I noticed there was someone still in the room. A figure who was just watching me, not practising or anything. I just ignored them. I had a routine to practise. Then one night, when it was just me, something happened that changed everything.

I was midway through my routine when a woman appeared right in front of me. She was so close I thought her nose might touch mine. I’m a bit embarrassed to say that I screamed, and lost my balance. Falling isn’t new to me, but I was lucky I didn’t hurt myself. When I looked around again, she was gone.

Do you know who she was?

I knew, but I didn’t want to admit it. I’d heard the rumours, but I put it down to overworking myself.

Except that the next night, at the same point of my routine, I heard breathing right behind me. I knew I was alone, but it sounded so real.

What did you do?

I continued my practise. I was determined to get the dance done right, and I had a deadline. I couldn’t cancel the show because of a ghost. I accepted that she was part of the practise. Things would move, she would whisper behind me, or appear in front of me. A few times she even pushed me.

And you still did the dance?

I think she was testing me. Making sure that only the strongest dancers could follow in her footsteps. Part of me thinks it’s to stop people who aren’t ready for it from trying. By the time the curtain rose, nothing could make me fall. From the moment I lifted my foot, I remained steady.

To those who are considering performing the Last Dance, I’ll say this:

Make sure you’re prepared. Make sure you get it right. Mahia Noor herself will be judging your every move.

by Aoife Murphy

56

Composition

Emitting radio waves

Standard 440HZ

Ascending and descending

Melody and rhythm

Strings vibrate

Voices in unison

Bang of a drum

Intro with a hook

Bass guitar groove

Soaring chorus

Turn it up to eleven!

Dance to the beat

Scales of major Minor and diminished Chords and notes…

…Fading…………..

…………………out slowly…………..

by Damien Kelly

57

Backstage and Bitter

Most people hate the idea of being on stage, but I quite enjoy it. Not because I can’t get enough applause, or that I have some troubled past that pushed me towards performance. Ironically, I think it’s because conversation is difficult, and dishing out wit and charm can be exhausting. It’s nice to be on stage, where you’ve rehearsed the conversation hundreds of times. Where your cues and responses have been written for you. There’s something comforting about that.

Non-actors always ask, ‘What if you forget a line?’ A terrifying prospect admittedly: freezing during a scene; unsure of what to say; the eyes of the crowd and your fellow performers burrowing into you, pleading with you to come out with something. It’s a possibility that’s often brushed aside: ‘If you forget your line, just move on and no one will notice.’ It’s a risk you accept when you agree to step into the spotlight.

Any actor can tell you what it’s like to forget a line. What’s often overlooked is when someone else has forgotten their line.

Lulu was playing the lead character, ‘Millie’. Lulu was the quintessential ‘theatre kid’, the first in line for school musicals, with several lead roles to her name. Working with Lulu was an odd experience. All I’d ever heard about her was how her exceptional talent was the highlight of every production she was in. She was talented, I couldn’t deny that. She was a great singer too. But I found her frustrating to work with.

Lulu hadn’t learned her lines. She was involved with at least two other productions, so sometimes wouldn’t even make it to our one rehearsal a week.

There was no point in me getting angry with Lulu for not knowing her lines. All I could do was ensure that I knew my part as best I could. On stage, I would hope that actors knew their lines, not solely for the sake of their own performance, but out of respect for the people they’re sharing the stage with. One missed line can easily spiral into a missed cue, throwing someone out of position. The audience won’t notice if you don’t

58

*

recite the script word-for-word, but they’re sure to notice if an actor freezes in place and starts sweating through their costume.

I could cold-read lines for a year, attend a thousand rehearsals, and still the show wouldn’t feel real until the dress rehearsal. It’s that whimsical window when everything is ready: the set, the sound effects, the props, everyone in costume; a full run-through of the performance, minus the audience.

The dress rehearsal was going steady and we were ironing out the final kinks. Warm beams from the overhead lights bounced off our makeup, giving us a sort of ethereal glow. Everyone was ready, except for Lulu. I really hoped that Lulu would get her act together and learn her lines by the following night. After repeatedly flubbing the same line, Lulu was met with an eye roll from the director. I could see the director’s logic; if she hadn’t learned her lines in the last two months, how would she miraculously know them by tomorrow night?

I was conflicted. Lulu had always been relatively nice to me. It was everyone else she fought with, especially the director. One side of me saw a decent person who I wanted to see do well. But the part of me who’d endured months of performing with someone who refused to put in equal effort, wanted to see her fail. Perhaps I was just curious as to what blatantly forgetting a line looked like on stage.

Showtime at last. We’d been told a week prior that a mere fifty-five tickets had been sold, until tonight, 170 seats. Fifteen minutes later, all 200 seats were sold, a full house. I sat with Lulu in the makeup room. We were still running lines as we were being slathered in powders and creams backstage.

As our scene approached, I braced myself for the dreaded speech that seemed to evade her, no matter how many times we ran it. She took her position and delivered it…flawlessly. Her movement, enunciation, emotions, all brilliantly executed. I was flabbergasted. She’d done it, and

59

*

*

wonderfully so. And to think I’d been focusing on how I was going to swoop in and save it if things went wrong. What a relief, I didn’t need to say anything.

The theatre had become eerily quiet. There was a prolonged silence as Lulu turned to face me. Her speech had been one of hope and promise, so why was her smile beginning to falter?

I was so relieved that I’d forgotten the entire theatre was waiting on my next line.

As hundreds of eyes burned into me, I tried desperately to recall the last thing Lulu had said, but I just couldn’t remember. She had so many lines to learn that it could have been any one of them. It was an awful feeling, like trying to give an impromptu presentation on a topic you knew nothing about. I wondered if many people in the audience had noticed. I felt a trickle of sweat on my forehead. I didn’t know if it was from the lights or the disappointment that I felt in myself.

I don’t quite remember what I ended up saying- some jumbled mess of agreeing with whatever had just been said- while trying not to break character. What I do remember was Lulu’s decision to move on to the next cue, which I couldn’t have been more grateful for. I’d been so critical of Lulu for what I’d considered a lack of dedication. I’d always been praised for my ability to learn lines, the possibility of me losing my place hadn’t even occurred to me.

After the bows, we retreated backstage. I apologised to Lulu, and she shook her head, ‘Just remember, they don’t hand out the medals until everyone’s crossed the finish line’.

by Shea Fahy

60

Fake Gold

I check my phone and read every single article I can find about Kellie Anne Harrington. I don’t watch boxing. Ever. But I watch her. And I bawl my eyes out along with her when the flag is raised to Amhrán na bhFiann in Tokyo.

That week, my kids go round the room doing jabs and crosses, wanting to be her. I put my Kellie-Anne’s to bed and tell them it’s hard work and determination that gets you an Olympic gold. I tell them we’ll do cardio work-outs and boxing every day from now on.

On TV, I watch the open-top bus and Portland Row party. I decide to have a Kellie-Anne party at the weekend. The kids will dress up in boxing gear and take turns in a make-shift ring.

It’s Saturday and all the Kellie Anne’s barge into the kitchen and I’m unsure about how to deal with them. Some are sweaty having done their warm-ups, others complain they’re not ready. We clear back the table and chairs, mark up the ring, agree some rules. We spray-paint some jar lids in gold and tie twine through them so they can all have an award at the end.

‘But Kellie Anne’s a champion by herself’, they say. ‘There can be only one champion’, they roar in unison.

‘Okay, fine’, I say.

I ref some matches and award it to my sister’s Kellie-Anne.

‘That’s so unfair. I was the best’, ‘No I was’,

‘No way, I’m way better’, they wail.

‘Right’, I say, and call all matches a draw.

Then all hell breaks out. One shoves the smallest boy, another pulls hair, someone retaliates with a punch, another with a kick. I intervene and get hit in the nose.

‘Right, that’s it’, I shout, ‘I’m the winner! Me!’ I place the knotted medals from my wrist around my neck and shepherd them all into the hall ready for home.

‘You look like a Christmas tree’, one boy says, messing with the flashing medals in their fake gold paint.

‘That may be so’, I say, ‘but a win’s a win’.

‘But you didn’t really win’, he says.

‘And this really isn’t a Kellie-Anne party’, I say.

by Rhona Trench

61

a landscape for forgetting

I hold a single white sheet, a map traced edges of this country, its counties and borders: there is no blue for rivers, no red for roads, no elevations or compass to orientate only the flat outline of terrain and black circles, so many, they form thick clouds to the West. There is a single legend to decode: cillínunderneath spaces, ground to forget, beyond words or maps. Here, under seeling night and hard stars where mists shroud and winds wipe meaning from weathered stones, wind-bent hedgerows twisting from trunks as if to look away, a place where everything moves to forget the men came between dusk and dawn delivering their unnamed infants to the clay, unwilling midwives at boundary ditches, crossroads, holy wells, outside churchyards, beneath standing stones, in fields with lost names –Infants’ Hollow, Corpse Field, Strangers’ Hill. There are other rifts lost tellings held in the sediment here, all that mother ache from dark rooms still humid with the heat of birth and blood their weightless bundles, like birds’ pneumatic bones, taken from them, small bodies they never held names they were told they could never speak. Their grief shadows this place is mist, seeped into stalk and blade is the soft ground all they were told they could not say sod-choked and searching,

62

the map’s black circles, deep wells we can never know. But we have these dark coordinates because they could not but remember and sought others, troops of lost children, to lay theirs beside and set stones in the gouged ground to say you were mine. Alone with the spade and the night they spilled the sun’s stones, the grianchloiche gathered from the riverbed, around the small bodies planted there, seams of glinting silver to light their infants’ sky to blink towards others lost there to map them on a landscape, to say they were here.

by Una Mannion

Cillín

63

Tommy Weir

Sessuegarry, Sligo, 2018

Bare Bones & Shadows

There is ambiguity in everything interesting: memory, thought, language creates ambiguity…it’s what it means to be human…it’s what it means to be woman. That is why they burned our sisters at the stake, after raping and mutilating their bodies. That is why they locked our pregnant sisters away, disowned by family and society. Those people were an enigma; could not be tamed nor contained within the proscribed diktats of patriarchal power. Inquisitions don’t need a reason other than power to control.

So, to the question, ‘How do I describe myself?’ My own process of ‘selfinquisition’, not of control but of rediscovery.

Stripped down, naked. An automaton? No! A cyborg, programmed with all the infectious ideologies to fit the social credit system? No! A voice, yes, sometimes weak; to speak a truth to a people fear-filled, corralled. Cattle prodded into submission. The ‘over 60s’, the ‘over 60s with underlying health conditions’, ‘the under 60s with chronic illness’ - each group already identified and branded - not with a Star of David, but with up-to-date ‘Covid’ vaccine cert. Dispensable: their morbidity already programmed and recorded: cause of death, COVID.

64

The V sign, no longer a symbol of defiance, but of compliance. If I do not fit into this social credit system, then who am I? Within this system, ‘I am not’. I am ‘the other’, one of ‘them’, ‘they’, ‘the outsider’.

To ask a question has become an offensive endeavour. How have our human and civil rights been allowed to be so quickly and grossly eroded over a three year period? Where has my voice been? How has the voice of reason become ‘unreasonable’? Silence is the deafening echo of a dying people: a silence that ricochets back from the tombs of our ancestors. Bare-boned, ragged people call from the shadows: Beware! Beware!

Frida Kahlo, the Mexican artist-painter describes herself thus:

‘I don’t give a shit what the world thinks. I was born a bitch. I was born a painter. I was born fucked. But I was happy in my way. You did not understand what I am. I am love. I am pleasure. I am essence. I am an idiot. I am an alcoholic. I am tenacious. I am; simply I am…’

I was born a teller of hidden, secretive stories; stories begun before I was conceived. A writer, a stripper of pretence, a precocious child who didn’t learn her place. To those who do not know me, I AM what you see. Bare bones and shadows.

by Sheila A. McHugh

65

French Motormouth

The Covid lockdown over, I take the ferry to France and head on to the motorway.

After a while, hunger forces me to stop at the Aire de Bretonneux, a gas station with a sandwich shop. Proud to be able to use my school French, I order a sandwich.

‘Take-away or sit-down?’ These are the only words I can filter out of the waterfall of words the woman behind the counter aims at me. She speaks like a machine gun, a French motormouth!

I mimic her, be it several kilometres per hour slower, ‘Sit-down, s’il vous plaît.’

‘Avez-vous une carte sanitaire,’ she fires back at me.

I’m baffled.

I’m getting on in age, and I’m perfectly aware of that, but I didn’t know that one needs to attest one still has all of one’s sanitary facilities here in France.

My bafflement obvious, and impatient as she is, she repeats what she asked about the sanitary card. Same machine gun speed, but louder this time. I’m convinced she exists in a parallel dimension, somehow connected with ours. People here can speak at supernatural speed. By now, my bafflement doesn’t allow any production of school-French words at all.

‘Avez-vous une carte sanitaire,’ she says again. A lot louder this time, as if increasing the volume will also increase the possibility that I suddenly, magically, will produce a card that will prove that I can be trusted to go to the toilet on my own.

I feel my face burn red hot while I desperately try to formulate a sensible French sentence to inquire why I need a sanitary card to eat my sandwich. But she’s way ahead of me and blocks my efforts by screaming the same sanitary words, again, and again.

This screaming actually saves me; her colleague looks up. This one seems to be more at ease in the bafflement department. She points at a tiny flyer pinned low on the wall next to Motormouth.

It says, ‘Ici Pass Sanitary obligatoire.’ Underneath it, there’s a translation, ‘European Covid Certificate mandatory.’

by Marc Gijsemans

by Marc Gijsemans

A Bridge Between Two Lands

Thirty, thirty-one, thirty-two. I can’t help but count the steps like I did as a child. I learnt to count on these steps. These steps between our building and the next building over — where my older sister moved to when she married. My grandmother would hold my hand and as we stepped down the steps to go to the market or up them on our way back, we would count each one we took. Even as a teenager, bounding up and down them two at a time, I would count the steps in my head. I couldn’t walk these steps without counting. Except for the last time.

The last time, I counted my family members. I counted the men with guns. I counted the possessions I could carry. That number grew smaller, first because I couldn’t carry everything, then because I couldn’t gather everything up again, whilst scrambling to my feet after I was hit with the butt of a rifle and fell. Then I either bartered some things for food and safety, or they stole my possessions from me. I counted the days since, then the weeks since, the months since, the years since.

Four dangerous country borders, one big and fast river, two hostile seas, six NGOs, endless words in many languages I don’t speak, countless pairs of eyes glaring, judging, imploring, dead, hopeful, tired.

68

At home I was known by my name, maybe sometimes by my family name. As soon as I had to leave my home, I became known by new names with ‘Internally Displaced Person’, with ‘Asylum Seeker’, with ‘Refugee’. At first, they welcomed me to my new home, my new life. But because of the rules which state that people like me cannot work, the people of my new home grew impatient with me, and blamed me, and others like me, for many of the problems they were having. I understand how people can be worried about their economy, their way of life, but surely they can empathise with a people who lost all of that and their place of being, in one fell swoop. When people used to shout at me for coming to their land to live for free, I would try to explain that I did not want to live for free. I simply wanted to live freely. My home, which they forced me to leave, was much nicer than where I had to live as a refugee. The food, the games of football on the street and the lazy summer days on the riverbank — these were things I considered far superior to anything this new home was offering me. I did not leave it because I wanted to. I am grateful to have been given a home in a new land, where I am safe from the horrors of my home. But this new land comes with its own horrors.

Now I stand at the top of the steps I learnt to count on. Looking at my home, the home they forced me to leave and had dreamt of coming back to for so long. But it is no longer mine. I am a bridge between two lands now, not belonging fully to either.

by Teresa Heffernan

by Teresa Heffernan

69

_________

Today I saw a car with a Ukrainian registration

The chariot that bears the human soul

Stopped me in my tracks

In the car park of a once empty hotel

The big shiny black car mourning with a prosperous look

Other Ukrainian cars, all black. Their whole life, or what they had room for After packing the people.

My first car, Miami blue Yellow stripes, two doors

My first feeling of adulthood

I could live in this

Three decades on I hurtle along You can cover more distance in a car

What can you ever really see when whizzing by? Choose what to focus on to prevent a mind crash or

Slow down.

Treat it like a deadly weapon

When I learned to drive

Must stay between the lines

Safety in the rules

Which side am I on?

Collaboration by inaction?

my father told me

Today I saw a car with a Ukrainian registration

It stopped my cousin in his tracks

A refugee from Rhodesia in the 1970s

I can’t get them out of my head

Three decades on he carries his Ukraine

I was on the wrong side then.

Child battles in back to be heard Horn beeps to give a battle cry Car is my home, my castle Car is my tank

Could I have fled in my blue and yellow car

What would I have packed

What people

What things

What (March 2022)

by Maeve McCormack

by Maeve McCormack

72

Michelle Gannon

Untitled Photography

Jeans Man

A jeans man who can reach for things on high shelves

The person I tell things to A good person to have in your corner

You don motorcycle leathers to take a jar of pee to the hospital in below, be-low temperatures. You’re the person who asks, “how was your day?” Because you don’t come from here You’ll hear a phrase and wear it out often in the wrong place. You say, “I catched a cold.”

Your first gear is duty.

You sing your answers and compose songs out of our conversations. A musician, an engineer, a dreamer. Just for fun you mount massive mirrors on stilts to reflect the moon onto a stage built on the back of a truck and invite a band to play. You bring people together. We fall in and out of each other.

In Ladies Brae you pull a sheep from the mud.

You work hard, worry about the world. You tell me about a group of women making a sewing factory. Your first love is ice-cream with guf* and cream that comes already whipped. You can bear a grudge and, yet, be squishy like toffee.

by Rosaleen Glennon

73

*Guf soft meringue

Brooklyn Bridge, December 27th

The day after St. Stephen’s Day I walk across the Brooklyn Bridge for the first time. It is not the colour I expected. Its great steel girders all sprayed a smokey taupe to match its stone towers, which brings to mind Edinburgh sandstone but is actually granite above the water, limestone below. The wooden slats of the pedestrian walkway underfoot are narrow and delicate in their worn, sandy, wood-grey. The wire bins, chained at intervals along the way; the street lamps with New England silhouettes, dotted in sequence on alternate sides; the endless criss-cross of supports and bolts and clamps, all cloaked in a uniform of wet sand. A cohesion of colour which gives me the sense that I have stepped onto the back of some enormous creature whose precise symmetry emerged, multiplying, from the very bed of the river below. Its cables climb in front of me, each vertical held in place by its own exquisite brace along a stout pipe, met by ascending horizontal cords of tension, to form a lattice of diamonds and squares that soar up to meet their tethering points on either side; a taut fence of suspension held in the balance by the watchful, sandy towers. It is a passage which draws me in, repeating parallel lines sucking me like sirens along this great conveyor, leading me to its inner portal which sits between two great apexes- two knowing eyes watching steadily as we on our human feet stream unconsciously through, crossing from here to there. On the threshold, an artist readies his easel and prepares to sketch. I take photos of all the little details: the bolts and nuts and welds, the care of the workmanship, the comforting sequences, and I store them, to be examined later with my love at home who is not himself. I take one of me, red woollen hat and cautious gaze

floating before these sentient gates, and send it to him immediately, to let him know he is with me. Beneath my feet, through the springy wooden slats, cars flow like schooling fish, rushing along the same line as me, their mighty bridge carrying them across the river below, as it courses right to left, wanting to wash us all out to sea. Around my head the cables pass in hypnotic rhythm, and it is no longer clear what moves -me, or everything else or none of us at the same time. Far below, on the Brooklyn shore, a couple on their wedding day have their photo taken along the banks. The sky is grey but will clear to a cold blue later and a brisk wind whips the bride’s veil behind her. I take a photo of them also, framing them between the girders, but they only show as a black and billowing white blur on my screen. I move on and as I begin to crest into Manhattan, I look forward into the crowd. I see a man as tall as me and we lock eyes over heads. He holds my gaze openly and when we pass, we both look back and catch eyes again, and smile. I turn and keep up my pace. I sense him before he arrives and his gentle tug on my shoulder is pleasant, anticipated. His face is warm and clear, and he tells me he is on a walking tour, but he would like to ask for my number, to maybe take me for a drink later. His clothes are clean and neat. He tells me he is from Belgium and, at first, he hears that I am from Iceland, but once I enunciate better, he saysAh Ireland, maybe sometime I will be there or maybe sometime you will be in Belgium?

I say I am only here for one night and he says he is the same, am I sure? We are smiling at each other and I nod, no thank you. He is already parting, but nods sincerely back and says, of course, he understands.

I have reached the end now and am turned to face the beginning, watching as he jogs gently away.

by Alice Turpin

by Alice Turpin

Crossing Paths

The building was one of those small-scale Brutalist abominations that had sprung up in the fifties. Ruth sat in the dingy waiting room. Two rows of cheap plastic chairs lined the narrow space, with small, high windows providing the only reprieve from the grim semi-darkness. Prison-like, or at least unpleasantly institutional. Ruth was baffled by the kind of lifeless thinking that had put such utilitarianism in vogue; her abhorrence of it was visceral - as natural as turning her face to the night sky.

The door opened apologetically. A wiry figure slipped into the room and sat himself opposite her. Ruth unintentionally studied his face – a lingering art school habit – and thought how pleasing the line of the jaw and the striking dark eyes would be to sketch. There was a softness to his demeanour, despite his angular build. A fluidity that would lend itself to a work of art. His gaze, ‘til now averted, briefly cast over her. Ruth, suddenly aware that she had been staring, blushed.

‘Sorry, you really remind me of someone.’

Jon smiled.

‘Yeah, I get that a lot,’ he lied, ‘One of those faces.’

He had noticed her momentary blush when their eyes met. Something in the immediacy of her apology, and her slightly downcast disposition, made him want to grasp her hand; tell her It’s okay! I watch people too! He smiled sheepishly instead, caught between a sudden longing to speak to her and his dread of these exact social situations. He watched as she absentmindedly leafed through an ancient magazine, her loosely gathered hair falling across her cheek with each tilt of her head. She looked tired and slightly vacant. Jon had the sense that he was seeing her through a thick pane of glass. His intensifying urge to speak to her was quashed by the unbearable prospect of small talk, so his voice remained

captive, safe to speak freely to her only within the confines of his mind;

Sometimes, sad-eyed stranger, the extraordinary shimmers within the periphery of the very ordinary (I think you know this) and these brief, happenstance moments become a sort of sustaining treasure... Can I tell you a story? Once upon a time, long long ago – before ‘Les Murs des Je t’aime’ had come to be – I met a Russian sailor who collected ‘I love you’ in the language of every port he docked in. It was a momentary crossing of paths in a dingy back alley – though not so dingy as this place... The pub side door swung open behind us occasionally, to free a plume of music and cigarette smoke. I can still see the tangle of moonlight and streetlight, the eager scrawl in his small notebook, and his sincerity. Such tenderness in that simple pursuit; an homage to the universal search, our persistent longing to hear those words: Táim i ngrá leat... no matter the tongue, and despite the futility of trying to hold mercury in the mouth and shape it into meaning, don’t we all yearn for such whispered benedictions? It takes so little really, to light the hollows of the heart, and something like recognition flickered through me just now when you -

The nurse called her name;

‘Ruth Connolly?’

She stood, gathered her bag and coat, smiled warmly at Jon, and walked towards the door.

‘I hope you find my lookalike!’ he blurted, and felt instant regret. ‘Mind yourself.’

Ruth, still smiling, ‘You too.’

He felt hope rising in him as he thought he heard the silence of her momentary hesitation, lingering, by the door. But her footsteps echoed along the cold corridor, and she was gone.

by Sarah McGrath

by Sarah McGrath

WHITE NOISE

Part of a series of images that reference time, transience, memory and place.

by Séamus Grogan

by Séamus Grogan

78

Focusing on visuals or artifacts that contain an emotive charge, the images propose an alternative way of seeing that redefine an experience of place. It suggests pace and time alter the observed realities, creating a type of abstract realism.

Utilising Photographic and Filmic processes, real imagery is observed but then abstracted by composition, juxtaposition and repetition. The curated images aim to broaden and deepen the viewers experience by engaging them through the use of actual and conceptual imagery.

In the ‘White Noise’ river series it proposes an analogous illusion of surface that twist, turn and divide depending on the pace, to somehow mimic the surrounding reality. Taking cues from historic photographic observations it interrogates the transience that has obliterated the remembered reality here. The delicate threads that linked the previous reality with the present have long since disappeared.

79

It Doesn’t Have To Be

It doesn’t have It could be the Movement of Water in lakes Slow and consistent

The river channel Between the lines Fast and persistent

It doesn’t have To be a pattern

A sunset sky or a Lighthouse lantern Maybe a halo star Draped in satin

by Paul Hamilton

Lamination

150cm x 170cm

Reverb

70cm x 70cm

81

Gavin Mc Crea

Show Me The Way

There was nothing particularly unusual about today, except that when I arrived home from work, my house was no longer there.

I had slept well enough, considering how cold it gets in the guest bedroom, and got up nice and early to make my usual porridge with low-fat Greek yoghurt and organic honey. I left for work at 8:15 am, as always, and arrived in enough time to brew myself a nice coffee before I sat down at my desk. I was in productive form, so I didn’t finish until 7:30 pm. On the way back, I stopped twice: at the Chinese restaurant to pick up dinner, and then at the off-licence, just to treat myself. None of this was out of the ordinary, which made the absence of my abode all the more mystifying.

There weren’t any signs that the house had ever been there – no driveway or foundations, not a single brick or crumb of concrete. There was nothing but a quarter of an acre of fallow land, just as the site had been when we bought it. Everything else looked perfectly normal on the road, with lights and shadows dancing on the drawn curtains of neighbouring houses. Outside, the calico cat that belonged to nobody stalked along, throwing me a curious glance before dashing up a tree. An auburn leaf fell in the opposite direction, settling silently on the ground. The only change was the wide, empty space where my dwelling once was.

It frustrated me, because I had put in a long day’s work and felt I deserved to wind down. Now, in my left hand I held a bag of duck spring rolls, chicken satay, Singapore noodles, and unnecessary prawn crackers – so much food, and no utensils to eat it with. In my right hand was a bottle of not inexpensive Redbreast 15-year, that I was now tempted to quaff straight from the bottle.

I left the whiskey and my quickly cooling dinner in my car, still parked in the middle of the road, to investigate my absent house. I walked along where my driveway once was, and right through where the front door should have been. I had always liked the marble floors of the hallway –the grass and mud felt far too agricultural.

A house couldn’t simply disappear without someone noticing it, I thought, so I rang next door’s bell. ‘Mr. Foley? I’m looking for my house, and I’m quite hungry, so I wonder if you could tell me what happened to it?’

‘He won’t help you,’ a familiar voice called from behind me. ‘He’s

82

watching an old film about the future.’

I turned to see the calico cat, descending gracefully from the tree. Sure enough, Mr. Foley turned the volume up on his television.

‘The old grouch. Did you see what happened to my house?’

‘I certainly did,’ she replied, pacing slowly towards me. ‘I’ll tell you, if you make it worth my while.’

‘I don’t have much to offer,’ I told her. ‘Would you like some chicken satay?’

‘I’ve already eaten. What about your whiskey?’

‘How do you know about that?’

‘I tend to notice all the little things that go on around here.’ She grinned smugly, the way only a cat can.

‘That sounds a bit tedious. Anyway, the good crystal was inside the house, so I haven’t got it.’

‘That’s fine. Just pour some out on the ground, and I’ll lap it up.’ The cat sat on the road licking her coat clean while I reluctantly fetched the bottle. She slurped up the golden liquor the instant I dribbled it in front of her, much too quickly to truly savour it.

‘So, my house?’

‘Oh yes.’ She paused, no doubt feeling the tingle down her throat. ‘It was blown away.’

‘Blown away? My five-bed, four-bath dormer was blown away?’

The cat nodded slowly and deliberately.

‘By what? It hasn’t even been windy today! That leaf didn’t even blow away, it just fell straight down from where it was hanging.’

‘I don’t know what to tell you. I was sitting right there in my tree, minding my own business, and I saw the whole thing get blown away.’

‘But where to?’

83

‘That, I don’t know. It just, sort of, flew up into the sky.’

‘Oh.’ I wrinkled my nose. ‘And what about my wife?’

‘Was she inside the house?’

‘She usually is.’

‘She probably got blown away too, then.’

That, in particular, was a shame. It meant the chicken satay would go to waste. At that moment rain started to fall, quite heavily, straight down onto our heads, so we made a dash for the car. The cat made herself at home on the passenger seat, plucking the fabric with her claws.

‘Would you mind?’ I asked.

‘Sorry, force of habit.’

I looked out through the window at the barren quarter of an acre.

‘I’m going to miss that house. I spent a lot of time and money building it.’

‘I wouldn’t know. I never had a house. I just curl up wherever I can find some shelter. This car will do nicely tonight.’

‘For sleeping, at least. But I need to have a shower before work tomorrow.’

‘Just lick yourself clean, like I do. It’s quite effective.’

‘As long as I look and smell good.’