NOEVEREN

a palimpsestic hamlet

by Astrid De Mazière

2021 . 2022 Master Dissertation

© All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo-copying, recording or by any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or specific copyright owners.

Work and publication of a personal master dissertation, within the master studio ‘Vicinity as Nearness in Space’ proposed by Gisèle Gantois.

Academic year 2021-2022.

Acknowledgments

A sincere thanks to Gisèle Gantois (academic promotor) for her guidance, enthousiasm and expertise on Noeveren.

Further, I would like to thank the community of Noeveren and the municipality of Boom, especially Flor and Walter for their warm welcome.

Lastly, I would like to mention my friends and family, for their unconditional support during this project and my studies.

Author Astrid De Mazière

Academic promotor Gisèle Gantois

Cover picture

by Astrid De Mazière

KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Ghent Belgium

NOEVEREN, a PALIMPSESTIC HAMLET

how the metaphor of a palimpsest can be used as an analytical method and design strategy in heritage practices

4 |

Table of Contents introduction

Table of Contents

p 006 p 008 p 040 p 042 p 048 p 132 p 134

ABSTRACT

METHODOLOGY

p 010

CHAPTER 1 - Analysis of Noeveren

The Rupel Region

Noeveren - a palimpsestic landscape Layering in Topography Layering in Time Layering in Social Permeability Layering in the visible Layering in the invisible

CHAPTER 2 - Problem statement & Research question

CHAPTER 3 - Literature study

Traditional heritage practices Alternative heritage practices Own design philosphy

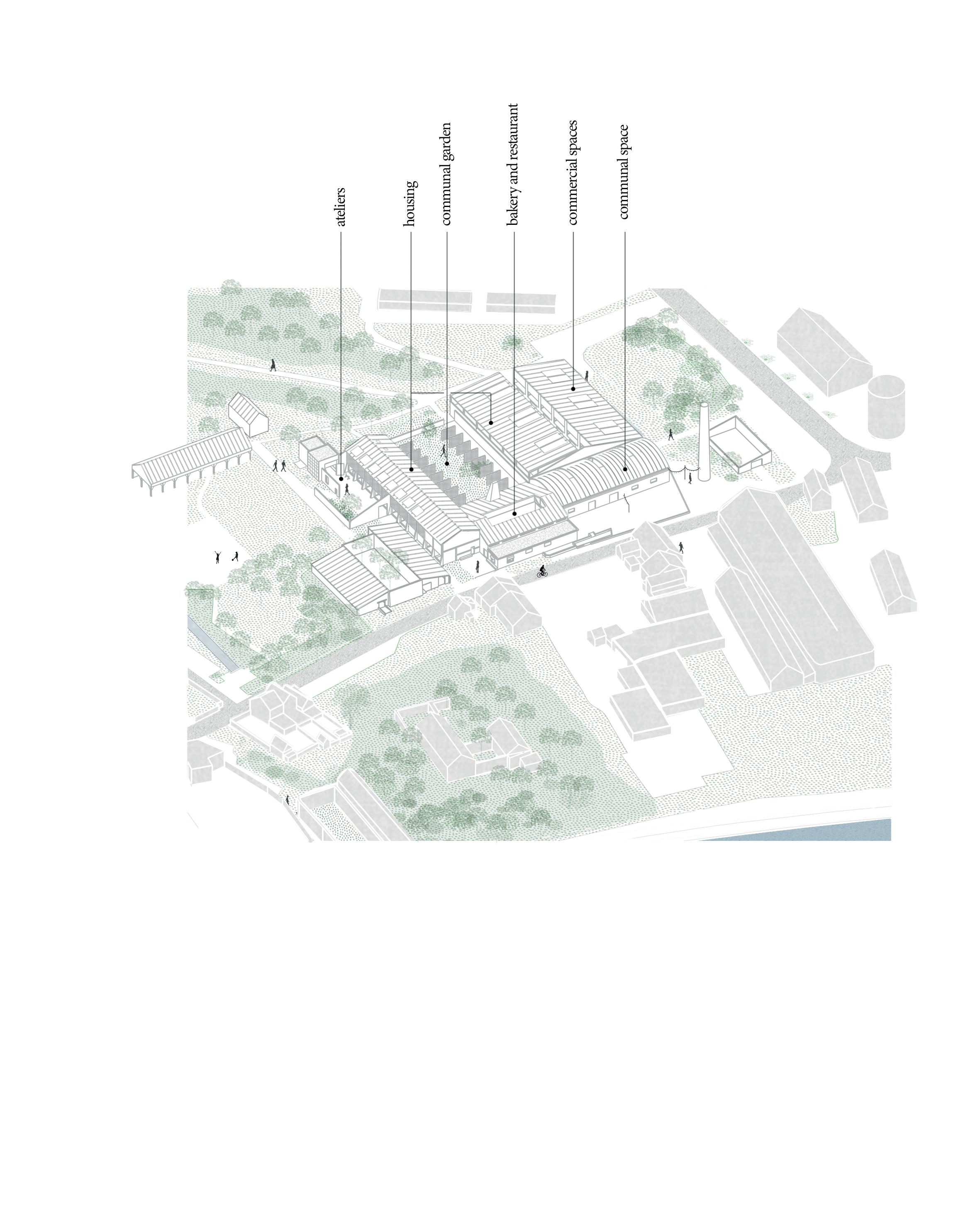

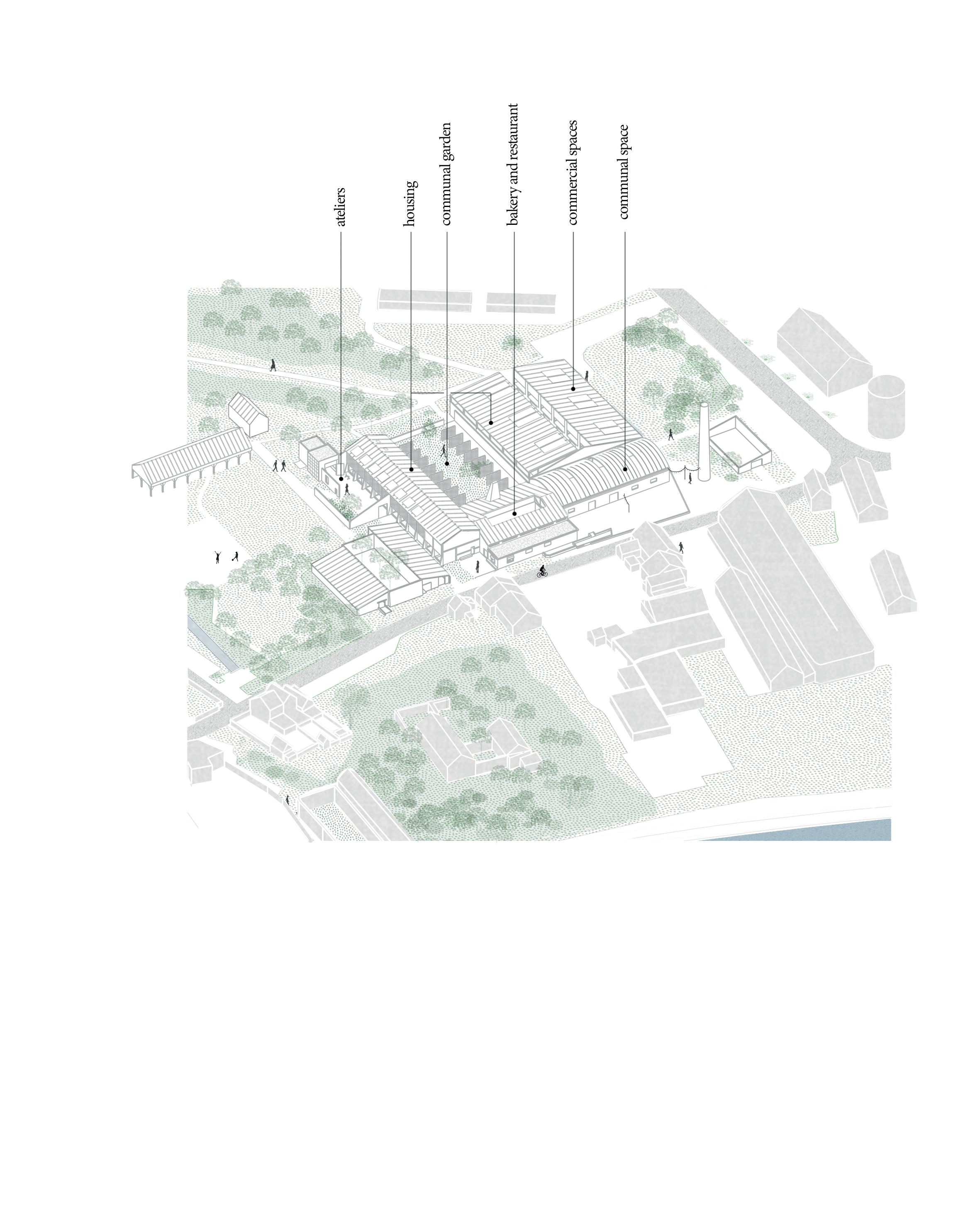

CHAPTER 4 - Case Study - introducing Site Lauwers

Introduction of the site Masterplan Introducing a new narrative Architectural interventions

Bakery and Restaurant Housing Ateliers

Communal garden Communal hall Commerical spaces

CHAPTER 5 - Closing

SOURCES

5

6 | Abstract introduction

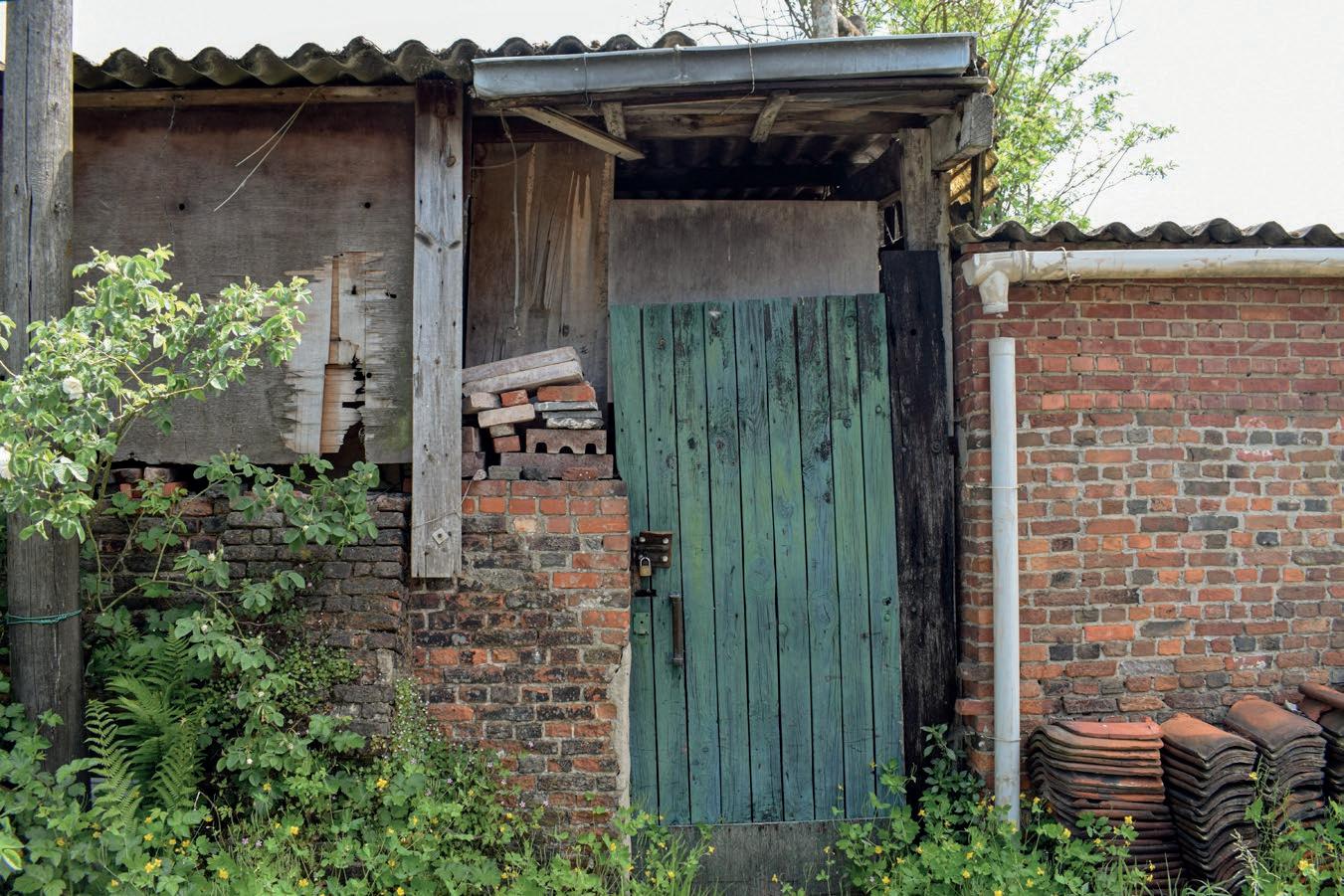

fig. 1 - A typical back street in Noeveren where the communal life happens

AbstractThis thesis explores the many interpretations of the ‘palimpsest’ metaphor and experiments how it can be used both as analytical approach to understand an existing heritage site and as design method when interfering. Using a palimpsest as design method is in itself not something new. However, the meaning of what exactly it entails differs vastly.

Therefore, the paper starts with defining the most apparent interpretations appearing in the hamlet of Noeveren, resulting in an analysis that is complex and not one-sided. Understanding the landscape as a palimpsest asks for immersion in the site: interacting with the community and observing beyond what is visible. In doing so, heritage and its context is recognized as what it truly is: a present being where its meaning is (re)written over time by all involved actors.

As will be understood, the remaining industrial site Lauwers profiles itself as outsider: physically being a part of Noeveren, but mentally not. Of its thriving past is not much left, as the site shows severe decay and carries a negative connotation. In order to reintegrate and reactivate the site, well-considered interventions need to be made. My proposed design answer follows the same route as the analysis: implementing the palimpsest as architectural design method. Designing starts with identifying what exists: recognizing the intrinsic qualities and weaknesses of each entity. Based on this, a process of rewriting, editing and erasing will follow. The purpose of the design is not to have a fixed end goal, but to start an ongoing process. One that inspires others in the future to rewrite, to experiment and to revaluate, because it is within this transformative continuity that the existence of heritage is assured.

7

Methodology

To get a profound understanding of a heritage site, one can not only base him/herself on theoretical evidence and classical surveying. Heritage sites are loaded with narratives, experiences, memories; individual and collective. A sufficient way to collect this type of intangible information can be through interactive walking, as start of a three-step practice-based research methodology that formed the initial basis of our thesis

By interactive walking, we become third-person narrators. “Walking provided us with the opportunity to be ‘more than an audience but less than a participant.” (Gantois, 2020, pp. 171). Being an immersive outsider we can bring new insights, based on our own experiences and knowledge, and it helps us, the narrators, to develop a certain interest on the site.

Our interactive journeys were captured in little jotbooklets, that were used later as a tool to create our own narratives through models, collages and maps, called spatial narratives. These are a hybrid of existing data and our own experiences and imagination. The last step of this research was to combine the experienced data into topographical maps, Cartes Parlantes. Besides only mapping the visual, the Cartes Parlantes also include the intangible, relations over time in space, unofficial walking routes etc (Gantois, 2020).

The above three-step research methodology was a good starting point. As I was unfamiliar with the Rupel Region, I began my walk in Hemiksem and followed the Rupel southwards until I reached Rumst. During my first interactive journeys, I got a first impression of the Rupel municipalities and quickly realized the complexity of Noeveren, as the odd one out. Noeveren doesn’t immediately reveal itself, it takes multiple visits to get a grasp on its meaning. With every conversation and journey in Noeveren, a new layer was dissected. This layered reading of Noeveren was non-linear and sometimes a bit chaotic in all its complexity.

Therefore in the following chapter, that contains my analysis of Noeveren, I combined my documented research material in a non-chronological way; it is a mixture of images from my jot booklets, photographs, sketches, spatial narratives, cartes parlantes and other found sources, gathered over a period of five months, supported with theoretical data.

8

| Methodology introduction

fig. 2 - Jot booklets

After the analysis, I will formulate the problem statement based on my findings. The ambition of my research is to reactivate the neglected site Lauwers and reintegrate this area as part of Noeveren. To do so, I use the same approach as used in the analysis: by understanding the site as a palimpsest and redesigning it accordingly. Before carrying out the design research of my case study, I will elaborate a concise literature study touching on today’s heritage practices and what its issues are. Further, I develop my own idea of what a palimpsestic heritage practice can be. The last part of my thesis, I will apply this design method on the before-mentioned case study to clarify how this could work in practice. With my thesis, I hope to not only revive site Lauwers, but also suggest an alternative practice that can be put to use in similar heritage projects.

Analysis of Noeveren

10

|

Analysis of Noeveren chapter 1 chapter 1

The Rupel Region situating in time and space

ANTWERP

RUPEL REGION

BRUSSELS

fig. 3 - Map: situating the Rupel Region in Flanders

11

Part

I

HEMIKSEM

SCHELLE NIEL

fig. 4 - Map of the Rupel Region

The Rupel Region is part of the province of Antwerp. It covers the following five municipalities, all located on the east bank of the Rupel river: Hemiksem, Schelle, Niel, Boom and Rumst. The presence of the river in combination with a clay-rich underground made the Rupel Region a protagonist in the clay brick industry, flourishing during the 19th-20th century. The industry has an irreversible influence on today’s landscape, where the unique manmade topography and the left relics of the industrial past are proof of (EMABB, n.d.).

BOOM RUMST

12

NOEVEREN | Analysis of Noeveren chapter 1

Modernisation in the brick industry made it impossible for the traditional clay factories to keep up. Mid 20th century the traditional brick industry in the Rupel Region largely collapsed, leaving behind a mined, exhausted landscape. The landscape lost its original purpose and as if the soil wasn’t contaminated enough, the clay pits became in the 70’s the ideal dumping belt for all sorts of waste: household waste, but also asbestos and other toxic substances. A dumping ban in the 80’s brought an end to this (Groen Boom, 2020).

The last two decades, the landscape underwent a beautification, as the province of Antwerp saw this postindustrial landscape as the ideal leisure playground for city dwellers and as an attractive residential area. Clay pits were filled, new allotments were created, mid-rise residential blocks were built on the banks of the Rupel. On designated areas, pioneer vegetation could run its course. Not only beneficial to repair the polluted ecosystem, it also fitted this idyllic framework as it became a backdrop for walks and biking routes along the Rupel.

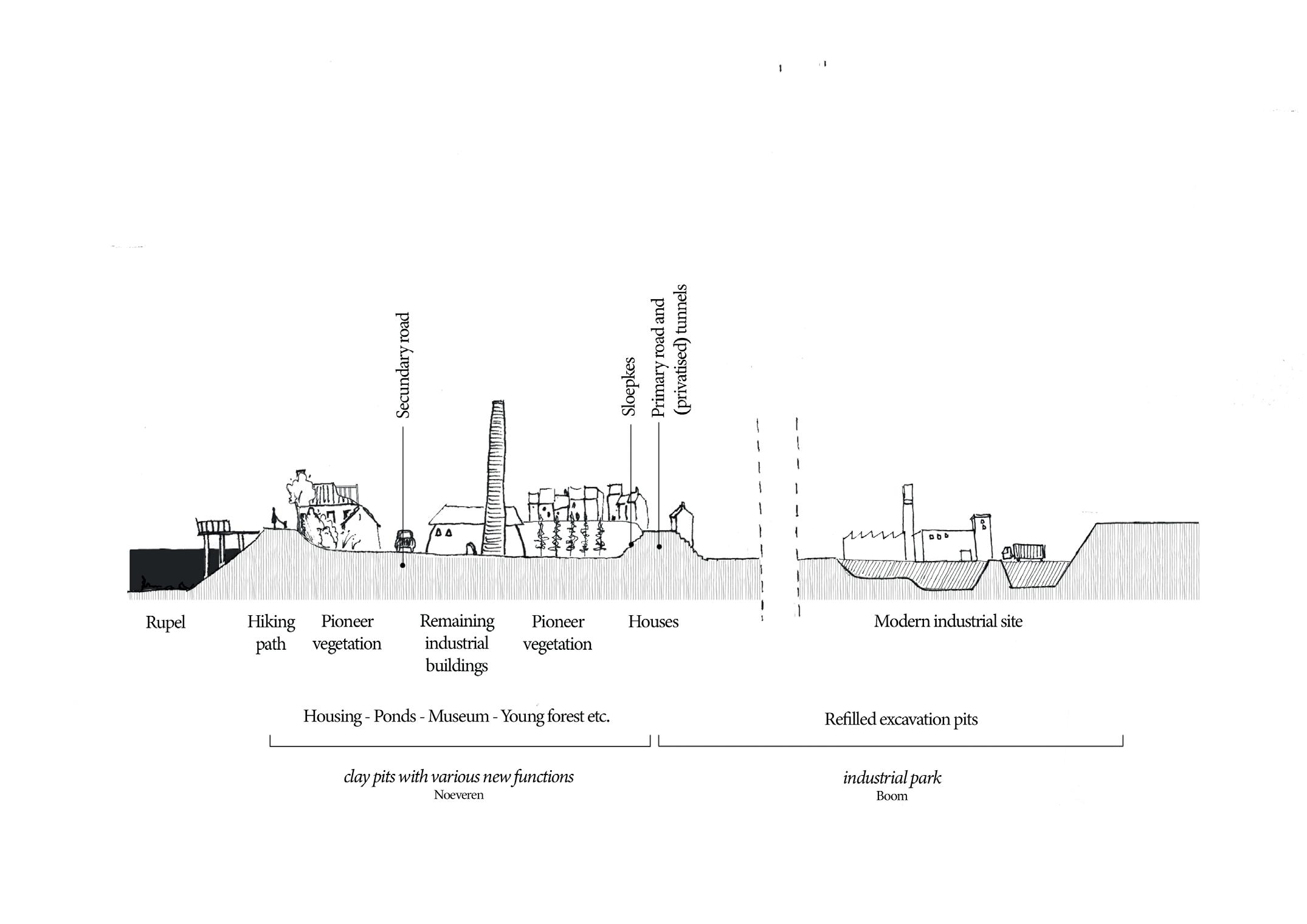

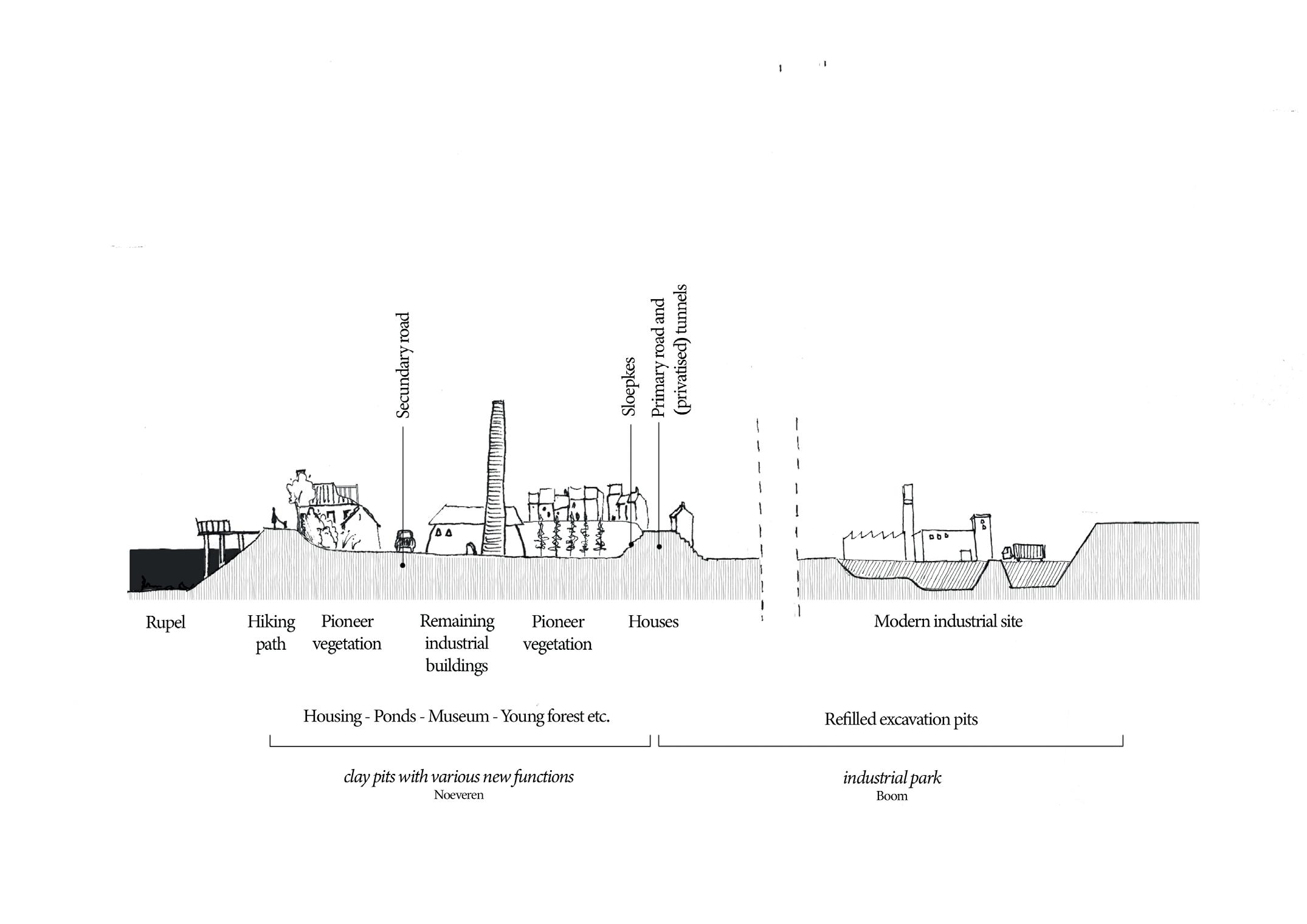

During my first interactive journeys, I found a recurring spatial layering in all these municipalities, (fig. 5). Behind the ribbon development, a high fence or hedge separates the residential area from the mined landscape. This abandoned area is partly given back to nature as extension of the river, where birds, amphibians, pioneer vegetation take over. In most cases, this green area is intersected by a hiking/biking path for leisure. The depth of this green area depends from village to village, going from 100 to 5 meters, where the residential blocks have a direct view on the Rupel.

13

14 |

chapter

Analysis of Noeveren

1

fig. 5 Spatial collage of the layered landscape. From top to bottom: Rupel - Recreational Area - Mined landscape - Fence - Housing

However, the landscape in Noeveren differs from the other Rupel municipalities, as it was designated as protected townscape in July 1986 (MD, 1986). Thanks to this designation, many elements of its industrial past have been preserved over time. What the designation of a protected townscape theoretically involves can be read in the ‘Erfgoedtoets’ [Heritage Test] (Buggenhout & Piffet, n.d.). This document focuses essentially on visible heritage and how it can be preserved. And so, a point of critic could be that it doesn’t take the intangible meaning of heritage into account. For a better alternative, that was created with a bottom up approach, I refer to the ‘Heritage Management Plan of Noeveren’, signed in March 2022 (Gemeente Boom, 2022): describing the objectives for the following 24 years. This was based on the ‘Visienota omtrent de wijk Noeveren’ [Vision Note for Noeveren] composed by Gisele Gantois and her students in 2018, suggesting a more nuanced heritage practice combining theoretical data with participatory practices (Gantois, 2018).

My analysis continues in the same vein, by recognizing Noeveren as a layered hamlet that goes beyond the visible. By immersing in the site and perceiving Noeveren as an infinite source of narratives, I intend to dissect Noeveren in all its complexity.

15

Noeveren

a palimpsestic landscape

fig. 6 - a Palimpsestic collage

“When one looks at the historical evolution of Noeveren (...), they see a palimpsestic land, which has been in continuous transformation over time.”

(Gantois, 2021, pp. 7)

Noeveren reads itself as a palimpsest, a complex layered being. Sometimes these layers are logically built as a superimposition, linear in time. In other cases the layers are randomly fragmented as a patchwork (Bartolini, 2013). I understand a palimpsest as a broad term, not only in the framework of time. A topography, social permeability, communal and individual narratives etc. are all interpretations of a palimpsest as they suppose a layering. On the following pages, I will further elaborate each interpretation and how they are interconnected to create structure in the complexity of Noeveren.

16 | Analysis of Noeveren chapter 1

definition

Palimpsest

A palimpsest is a recycled piece of parchment, where the top layer got scrapped clean to reuse for new writings. Even though the manuscript was rewritten, traces from the previous script were still visible (Archipel, 2019).

AS A METAPHOR IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN

André Corboz introduced the term in the field of urban design, understanding the city as rewritten land that conserves traces of its past. This point of view contrasted with the ‘tabula rasa’ ideal that modernist architects tried to implement in their urban designs. By reading the urban landscape as a palimpsest, Corboz recognized the city as transforming being, where the present is a product of the past. Meaning, the remaining traces have a value, historically but also as memory medium for its inhabitants, and so they have to be taken into consideration when making new interventions (Malaud, 2020).

Today, the metaphor of a palimpsest is still highly relevant in city planning and heritage management. Especially, within the sustainability debate to promote adaptive reuse: what can we reuse, what can be rewritten? In 2019, the term became the year topic of the Flemish architecture organization Archipel, where the metaphor was given a wide definition: an umbrella term for all phenomena that suggest a layered transformation in time (Archipel, 2019). I continue along the same lines, when stating my own definition.

In my understanding a palimpsest goes beyond the framework of history. Stratigraphy, a patchwork of materials, narratives, a social hierarchy etc. are all interpretations of a palimpsest as they suppose a layering. All of them are transformative over time, evolving constantly: a never-ending process of recycling, rewriting, erasing. By dissecting layer after layer, interconnections and relationships between the traces can be find. Eventually this will give clarity in the complexity of palimpsestic landscapes, and hopefully lead to better interventions.

17

18 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

Layering in topography

The topography can be described as a waffle-structure, where the excavation pits are surrounded with houses, who are situated higher up, on the slopes (Gantois, 2021). This unique manmade landscape all stems back from the organisation during the brick manufacturing era.

19

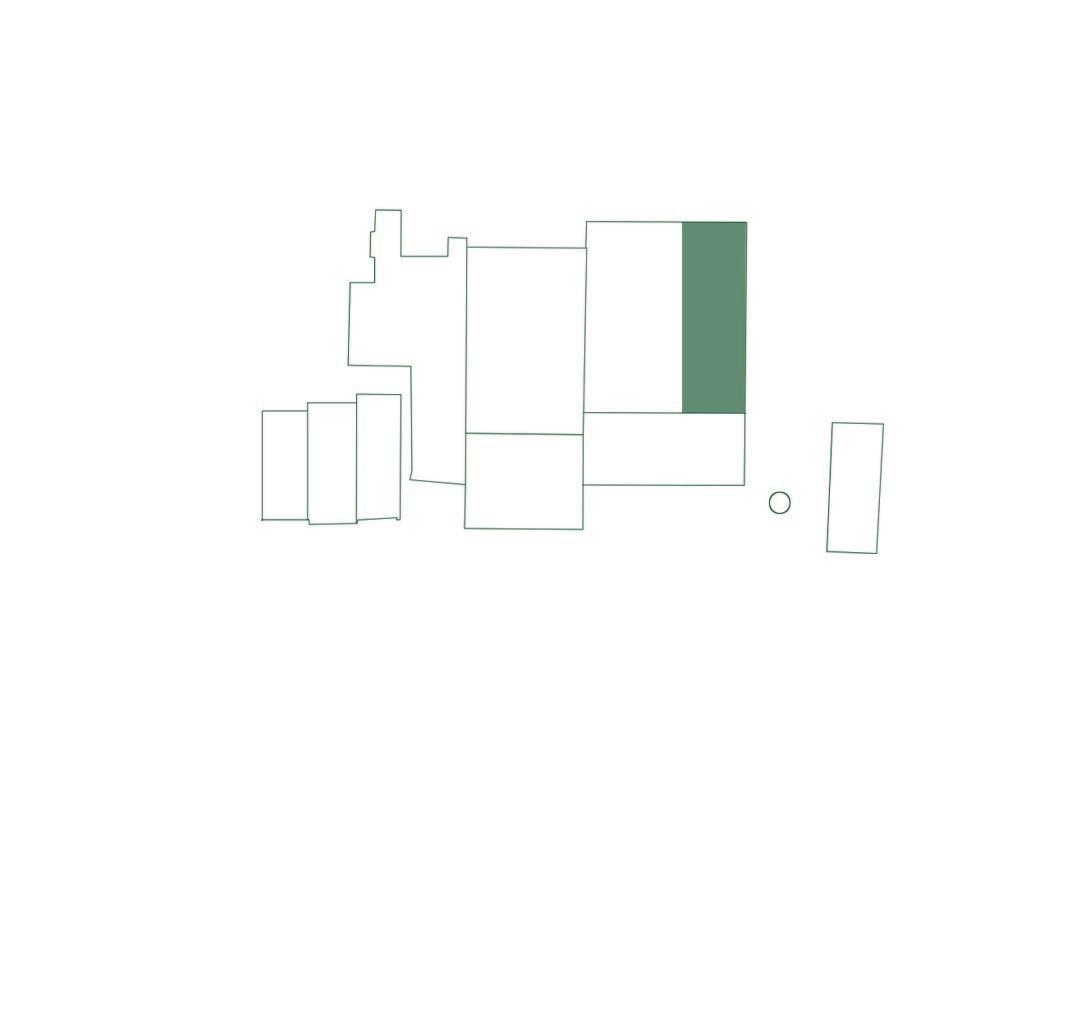

fig. 7 Waffle- structure of Noeveren showing three excavation pits with their corresponding brick factory. A site Peeters - Van Mechelen B site Frateur C site Lauwers

Originally, the landlords of the factories each owned a strip of land, perpendicular to the river. The factory was organized in different building (ovens, dry sheds, machine hall etc.) who were all located on the lowest part of the excavation pit, also called ‘t geleeg. The workmen lived in houses on top of the slopes around this industrial terrain. Workmen could leave their house and descend via the “sloepkes” to their work in just a couple of minutes. This way of organisation intended an easy connection between the workmen’s houses and their working space, and as a result benefitted the production process (Buratti et al, 2015). Over time, the residential fabric grew spontaneously and extended itself. A complex network of easements was created (Gantois, 2021).

Another important elements as consequence of the topography are the tunnels, who made a connection between the excavation pits possible.

Today, this topographical typology still forms the main spatial structure in Noeveren, where three former clay quarries have divided the hamlet. Each quarry houses a remaining factory being (from north to south) site Peeters - Van Mechelen, site Frateur and site Lauwers. Each site is surrounded by houses and their extensions, which have a unique layout due to the difference in altitude. The main roads, circling around the excavation pits, are still intact and used for car traffic. Same goes for the main pedestrian network: besides some closed-off tunnels and easements, the majority of sloepkes, tunnels and small pathways are still in use today (Gantois, 2018).

Even though the landscape hast lost its original utilitarian function, the resulting stratification hasn’t been touched since and influences the spatial use and organisation of today’s life. The vertical stratification of living and working, is still noticeable today in the organisation of the houses embracing the clay pits. In future projects the working aspect can be reintroduced in the excavation pits in order to reinforce this workingliving exchange. Also circulation-wise the distinction between car traffic which is located at a higher level, and the low-lying soft traffic, is still very closely related to the historical organisation (Gantois, 2021).

20

fig. 8 - A section perpendicular to the Rupel, 19th century, based on (EMABB, n.d).

fig. 9 - A section perpendicular to the Rupel, 21th centruy.

21

22 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

Layering in time

When walking in Noeveren, you can’t avoid its traces of the past: chimneys, workmen’s houses, dilapidated dry sheds etc. Noeverens long history has marked today’s landscape.

fig. 10Transience of a dry shed next to the manor house on site Frateur: over a period of less than 50 years the shed will be reduced to some traces and eventually become dust.

23

Layering in time 2007 2022 2050

History can be understood as a continuum of events. An example of this continuous transformation is the variation in configuration if dry sheds during the 19th and 20th century in the excavation pit of the site Lauwers (fig. 11). If we would want to rebuild these dry sheds, how do we decide what configuration is the most accurate or valuable? When only picking one event, we risk to end up with a very two-dimensional, idyllic version. The decision-making in whether or not a trace or artefact should be kept, is not so evident.

As architects, we contribute largely in how the landscape is curated: what needs to be visible for future generations and what traces should disappear to make place for new ones? What Flanders heritage considers as valuable, can be completely different to what locals perceive as meaningful (Gantois, 2020). In Chapter 4, I will elaborate further on how a thoughtful consideration can be made.

24 | Analysis of Noeveren chapter 1

1878 1981 2003 2022

An example of different perspectives in how a historical building can be handled, are the current developments in the three remaining brick factories: site Peeters –Van Mechelen, site Frateur en site Lauwers.

In site Peeters – Van Mechelen, the architects (and owners) transformed the building into a palimpsestic interpretation where new and old narratives are mixed. Program-wise, the common working-living combination has been implemented. Also visually, you can distinguish different layers: by using traditional materials in a new way or by not renovating/restoring every corner of the building. Some intentional ruinlike structures surround the garden and show the past, while on the opposite façade, large windows were added. The design is a compromise between the past and future.

The centrally located site Frateur is a stereotypical example of Flanders conservation practice. After a thorough conservation, restoration and rebuilding of some structures, today the site is open for tourists who hope to relive some of the industrial past through this architecture. As said before, this fixation of the past gives a very idyllic, one-truth-only idea of the reality.

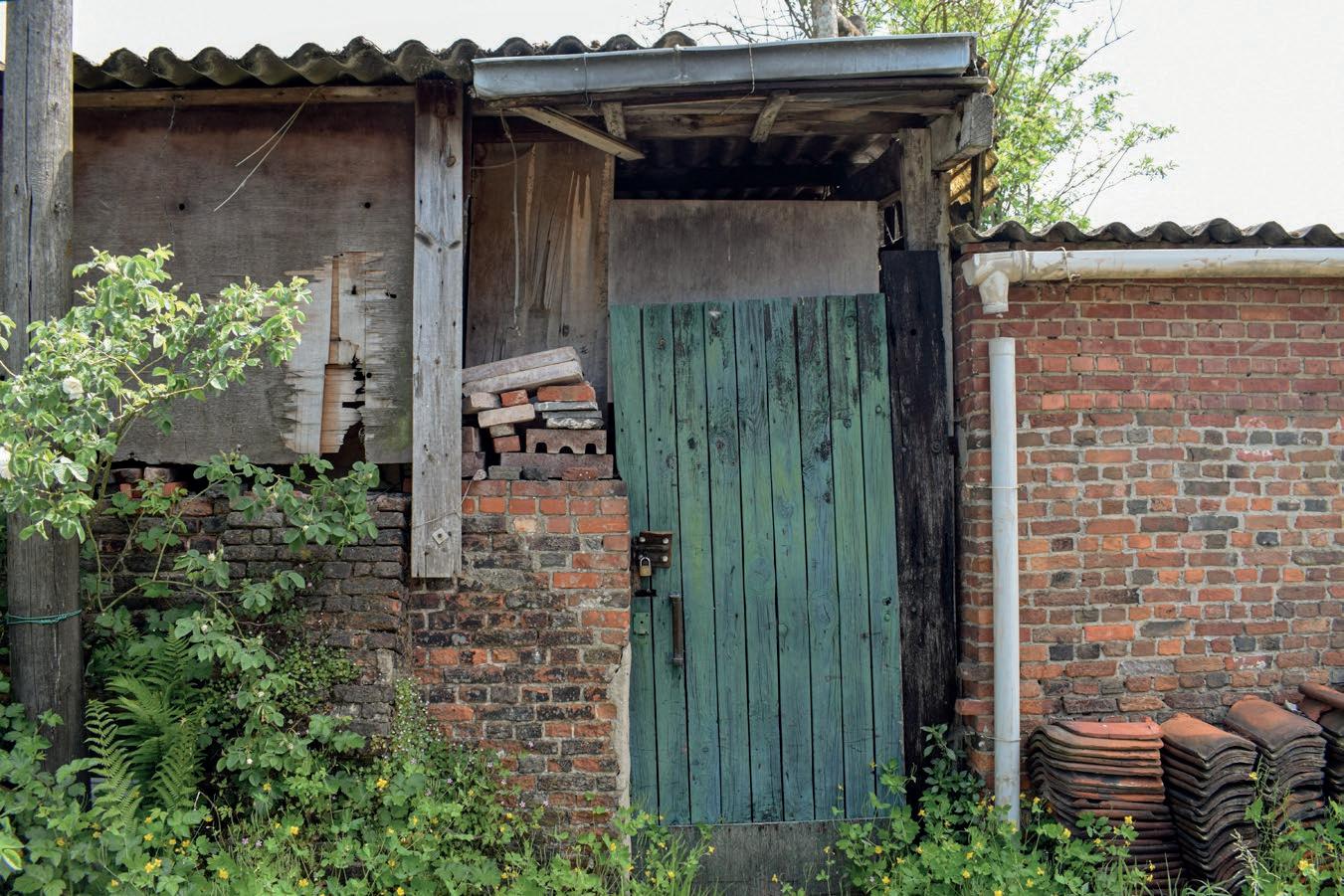

Lastly site Lauwers, who was the last active brick factory in Noeveren. Today, the site is left to its fate, at the mercy of nature and contaminated with asbestos. It has lost its meaning for the community. This also is a way of managing time: transformation will happen, not by human intervention but by nature. A valid question could be: but doesn’t the essence of existence lays in its meaning and use? If heritage disappears into nothingness, will the life cycle of the building end?

fig. 11 - left Configuration of dry sheds on site Lauwers changing over time, based on (Buggenhout & Piffet, n.d.).

fig. 12 top right site Peeters - van Mechelen (Dujardin, 2014)

fig. 13 middle right site Frateur

fig. 14 bottom right site Lauwers

25

Layering in time

26 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

Layering in social permeability

On the edges of the excavation pits, an interesting fabric of houses, annexes and alleys can be found.

If we zoom in on the ‘Reverse Row’, you can clearly distinguish a layered sequence of:

Main street – Private house – Communal Street – Backhouse – Garden/terrace – Garage

fig. 15 Spatial model of the Averechtse Root

27

Layering in social permeability

Interestingly, the outside transition space between the house and back house is privately owned, making the communal street a patchwork of private strips of land. When looking on the cadastral plans, you can see clear boundary lines of parcels. Paradoxically, in reality these boundaries are invisible. The street feels as one collective space. It’s by the placement of benches, flower pots, garden decorations how outsiders get a clue of the borders (Gantois, 2021).

Some of these houses don’t have a front door on the main street, as would be expected, but have their entrance on the communal street. To enter this street, one has to descend through the ‘sloepkes’. Sloepkes are small alleys, a stair or slope, connecting the main street with the communal street, located between two workmen’s houses (Buratti et al, 2015). Further this means, when entering their house they have to cross neighbouring private territory. This phenomenon is rather unusual in Flanders, where nowadays it’s a given to close off your private parcel with fences or high hedges, at the expense of the collective space. This alternative strengthens the community: it creates opportunities to interact, it forces inhabitants to take responsibility and care of their space and sometimes it leads up to a conflict (which is inherently part of building a community) (Gantois, 2021).

“Ownership, actual or perceived is a central driver for a successful interspace zone, meaning a zone for social interaction.” (Gantois, 2021, pp. 8)

This layering in tissue is accompanied by a layering in accessibility. A first time visitor in Noeveren will feel uncomfortable to enter through the sloepkes. Perhaps feel like an intruder. The accessibility is based on unwritten social codes and on trust. For a regular visitor, or neighbour, this transition space is pereived as collective space, free to enter, as long as the nonwritten rules of respect are not violated.

fig. 16 - Cadastral plans with the division of land through notorial acts

fig. 17 - Plans without the invisibile boundaries, presenting the collective space.

fig. 18 - Different walking routes, depending on how comfortable you are with entering the collective space.

28 | Analysis of Noeveren chapter 1

fig. 19 - Sketch of a backstreet.

The layering happening in the Averechtse Roat, applies to Noeveren as a whole. Even though almost every piece of land is privately owned, when walking, these boundaries are not visible. This results in Noeveren having a large collective space, where inner streets, little paths and tracks are all connected (Gantois, 2021). How much you want to emerge in this network, is not determined by physical indication, but will depend on the level of comfort and trust that is built between the visitor and locals.

29

30 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

Layering of the visible

fig. 20

Meesterwoning of site Frateur showing traces of the past on its facade.

When walking in Noeveren, you can not overlook the layering of the visible : in materiality, nature, traces of the past. Noeveren visually presents itself as patchwork of textures and greenery.

Layering of the visible

31

fig. 21 and fig. 22

Photographs taken on Site Lauwers. During the last decennia, the layer of nature has thickened itself in Noeveren. It seems like nature is taking back what once was theirs.

32 | Analysis of

chapter 1

Noeveren

fig. 23 Bricolage - layering of materials in the backyard of a Noeverian through recycling old materials and stacking them in case they would need it.

33

Layering of the visible

34 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

fig. 24 Layering of materials in an aesthetic way on site Frateur

NOTE

The visible aspect is important for tourists: they want to visually experience the historical landscape. However, the framework they get to see is of course a glorified version of the past. It’s an artificial shell, materialized, without any substance (Malaud, 2020). Some stakeholders, such as property developers, tend to experience Noeveren in the same way, reducing it to its physical state. They oversee the intrinsic qualities, the granularity and fragility of Noeveren. To avoid creating a rural idyll or making Noeveren an economic good, we have to emerge in the community to understand the narratives behind the visible (Gantois, 2020). Because it’s the community who defines Noeveren and keeps the hamlet alive.

35

Layering of the visible

36 | Analysis

Noeveren chapter 1

of

Layering of the invisible

“Monuments are not historical documents but active structures in the social life of the city, framing its collective memory.”

(Malaud, 2020, pp. 25)

When understanding a community, a crucial aspect is trying to get insight in its collective memory.

One way to do this is by interactive walking as we did. Approaching the community bottom-up, exposes gradually narratives, individual experiences, perceptions, emotions, rituals etc. that shape the invisible connotation of a place.

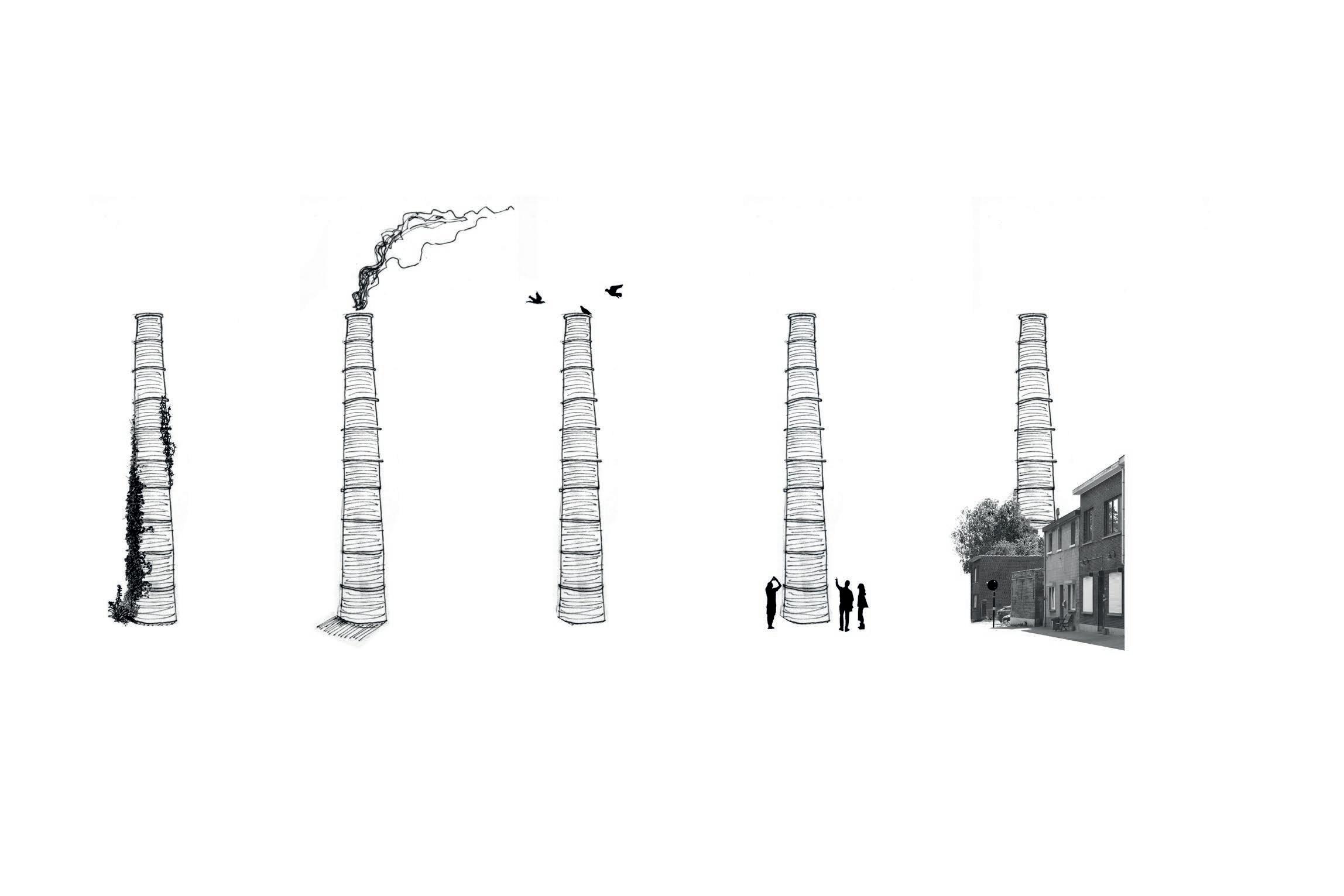

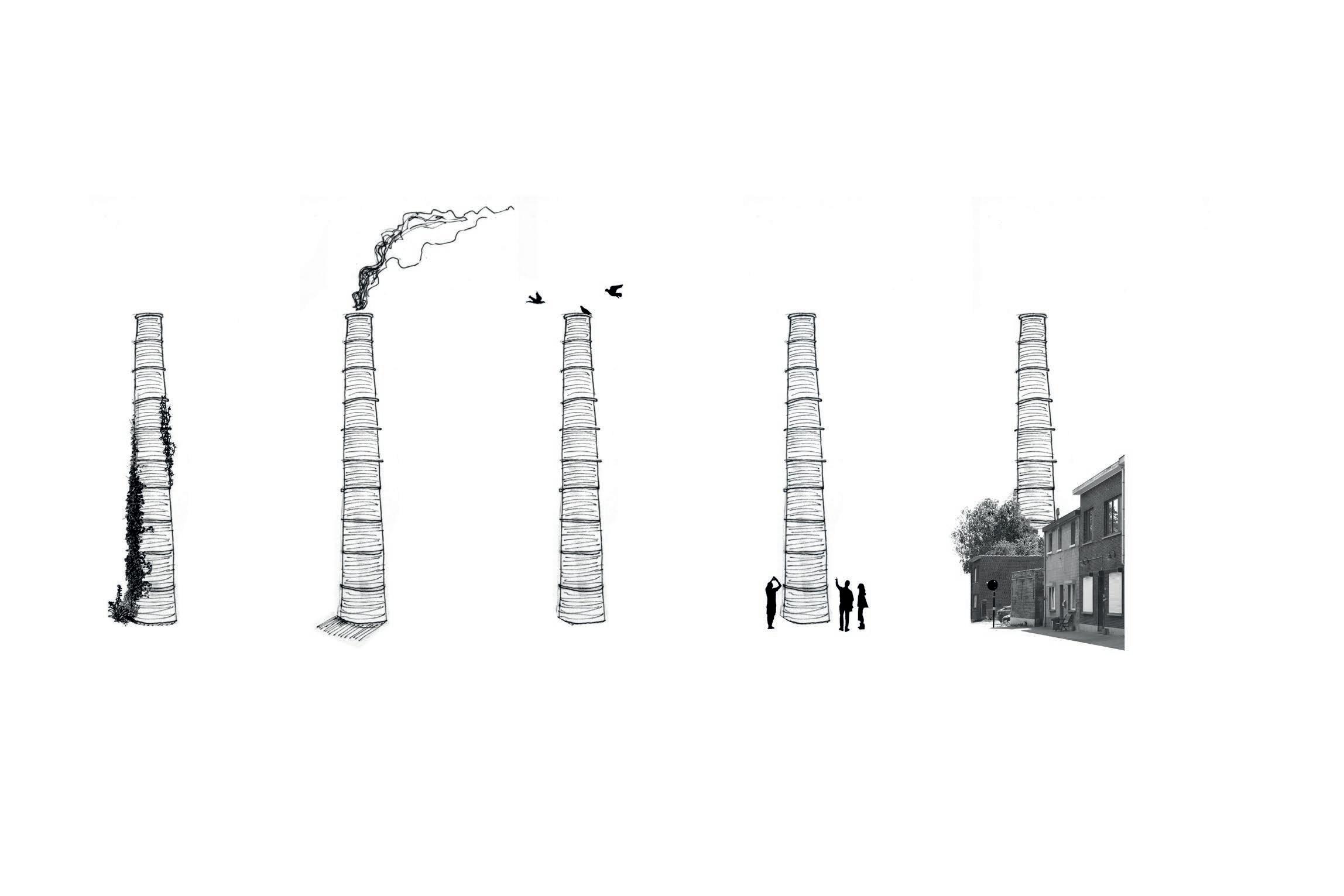

fig. 25

37

- Layered meanings of a chimney

support for vegetation industrial object habitat for birds and bats historic artefact landmark

Layering of the invisible

fig. 26 Site Lauwers has a negative connotation today – asbestos intoxication, squatting, vandalism, closed off... If no action is taken, it risks to turn into a pathological permanence.

38

Layering of the invisible

39

Problem Statement & Research Question

40

| Research Question chapter 2 chapter 2

Noeveren reads itself as a palimpsest, where multiple layers shape the hamlet and the communal life. As the analysis has indicated, the remaining industrial site Lauwers does not fit this framework. It misses this layered refinement. As the site is completely fenced and overgrown with vegetation, it doesn’t permit any visitors. This is highly in contrast to the commonly used ground, that makes Noeveren so exceptional. Due to the pronounced boundaries, the layering in permeability is here absent. Also in narrative, where the other heritage sites represent multiple narratives, in site Lauwers only one narrative seems to remain: a negative one due to the decay, pollution, vandalism and the feelings of unsafety it evokes. If nothing is undertaken, the site seems to be heading to the end of its life. That would be regrettable, as it could become an interesting generator of new activities, Noeveren is missing today.

In a layered context as Noeveren, how can we use the metaphor of a palimpsest as a design strategy to revitalize site Lauwers and make it meaningful again in the life of the community?

41

Literature Study

42

| Literature Study chapter 3 chapter 3

INTRODUCTION

Noeveren is the only protected Rupel municipality, sin ce it got designated as protected townscape, in 1986. The designation comes with regulations with regard to adaptations or new developments. Most of the time, the same procedures are being followed in order to protect the existing heritage. In this short study, I want to ex plore a variety of strategies, besides the more obvious ones also alternative practices. Firstly, the traditional discourse* will be discussed, which favours restoration and conservation to protect the physical state of herita ge. The second part will focus on alternative practices, understanding heritage beyond its physical state going from the deep city approach, to more extreme practices as ruination.

During both discussions, critical remarks will be made. What are the pitfalls of both practices and what has proven its benefits? Ultimately, after this study I hope to construct a nuanced understanding of different practi ces to eventually formulate my own strategy.

* Disclaimer - I refer in this text regularly to the term ‘traditional heritage practice’. By this, I mean the gene ral discourse that Flanders Heritage Agency (part of the Flemish government), politicians and other official instances (as Unesco) seem to pursue in regard of heri tage. Obviously, this is a generalisation; it does happen that these official instances deviate from their course.

43

Traditional heritage practices

The traditional heritage discourse focuses on the protection of the physical state of heritage, favouring restoration, conservation and preservation as main strategies. This conservation fever started in the 19th century, where objects, buildings, relics were inventoried and listed with the aim to retain them for future generations. In the 20th century, this listing and documenting peeked, leading up to having today an overwhelming accumulation of heritage that “needs” to be protected (DeSilvey, 2017). Thanks to this listing, we and future generations can visually experience the past. Heritage shapes our cities, they are important landmarks giving clues of what once was there. However, as Marie Balshaw point out: “Our heritage system is constipated. It is time for a no-blame conversation about letting some things change and even letting some things go.” (Balshaw, 2014)

Firstly this means, we risk to conserve just for the sake of it without considering what is really worth to. We need to reprioritize. Especially in Flanders, where a gradation in listing would partly destress our system. Secondly, what leads to many issues is the belief that heritage should be physically conserved for it to stay meaningful. This is related to the limited perception of heritage just being a materialized mnemonic device (DeSilvey, 2017). These train of thought risks to define heritage as an empty shell, rigid and a victim of time, further elaborated in the following paragraphs.

CONSERVATION PARADOX

Traditional heritage practices understand physical deterioration as a loss in remembrance. From this perspective, action is required to preserve the physical integrity of a heritage object to ensure its survival (DeSilvey, 2017). A problem with this way of thinking is that the focus is almost solely on the material state of heritage, and not on the underlying invisible meaning. Guaranteeing the life of a building goes beyond its material state. Its significance is largely dependent on the relationship it has with its community (Malaud, 2020). When a building is conserved and later used as commercial good, the community can feel excluded and start feeling estranged (Gantois, 2020). Outsiders will see a beautified heritage artefact, locals will experience

a meaningless object. And so paradoxically, in our attempt to conserve the physical integrity of an object, we risk to transform it into a stuffed animal: interesting to look at, but dead in significance (Archipel, 2019).

CONSERVATION MEANS STAGNATION IN TIME

Conservation results in a fixation of time, which counteracts a core characteristic of heritage, being the product of a constant rewriting of past narratives (Archipel, 2019). When we restore a building to a previous state, we simultaneously eliminate a multitude of opportunities (DeSilvey, 2017). It becomes an artificial imitation of one past narrative. Heritage that has survived until this day, has adapted itself to its surroundings over time carrying many narratives. Conservation partly counteracts this quality and threatens therefore the long-term existence of a building.

HERITAGE AS ECONOMIC GOOD

When understanding heritage as an object is can easily become an economic good. Tourism, as an example, where the owner maintains the building with budget brought in by tourists. Not only does conservation costs an enormous amount of money, the maintenance costs long-term are even higher. In practice, this often results in heritage becoming a privatized profitable good. This also applies to project development that commercialises heritage and turns it into exclusivity (Gantois, 2017). Facadism, showing “authentic” elements, giving the site a name related to the past… all are marketing tactics to attract potential buyers. Municipalities and Flanders Heritage Agency most of the time accept these practices as the project developers generally follow the heritage guidelines, which are solely focused on the material aspect. The danger lays here in creating developments that are no longer connected to the traditions, stories and opportunities, the involved heritage once beared (Malaud, 2020).

The main issuu with the traditional heritage practices is their lack of adaptability and ignorance of the intangible.

44

Alternative heritage practices

The following experimental practices understand heritage as a continuation of transformation. They recognize the many temporal and social layers heritage can carry. In doing so, they can all be called ‘palimpsestic’ approaches. The first paragraph describes a more extreme practice, teetering on the edge of neglect (DeSilvey, 2017). The second practice is more nuanced, and focusses on the social significance of heritage and how a community can play a role in the recycling process of heritage (Malaud, 2020).

A CURATED DECAY IN A POST PRESERVATION ERA

In a Curated Decay, DeSilvey refutes the belief that remembrance can only be obtained by material statis. Material statis means fixating one specific state, heritage once took during its lifetime. In doing so, we hope it can act as a mnemonic device to make one past available. This is counterintuitive, as heritage has not one past, but is a collection of stories and functions. Instead, we should recognize the transformative nature of heritage and embrace change ‘not as loss but as a release into other states’. DeSilvey even goes a step further: she indicates the possibility of facilitating persistence of memory through transience. She proposes to intervene less or even not, to let the process of transience run its course, resulting in ruins, feral landscapes, dilapidated heritage… Intervening less will increase the entropy of heritage. High entropy can be defined as a greater range of potential configurations heritage can possibly take. And so, the less we intervene, the more transformative heritage is (DeSilvey, 2017). I question this idea: is not intervening necessary to facilitate transience? Can we not catalyse transformation through intelligent architectural interventions, that wouldn’t be possible in case of neglect? Also, if we don’t intervene, heritage will at some point disappear physically, but also from our memory, because humans will no longer interact with it when it becomes too dilapidated and dangerous. What are the social consequences of the curated decay?

CONSERVATION MEANS STAGNATION IN TIME

The ‘Deep City’ approach strives to protect the transformative and temporal character of cities and

acknowledges the importance of the community in this process. ‘Deep City’ means looking beyond what is visible on the surface, but dissecting the city (or a heritage site) through its complexity of layers (Fouseki, 2020).

“Deep cities approach indicates the significance of studying, understanding and creatively incorporating the temporal layers of the city into its multitude and complex socio-spatial dimensions.” (Fouseki, 2020, pp. 3).

This approach is largely based on Aldo Rossi’s theory, where heritage is understood as locus of the collective memory. Heritage shapes our mental landscapes: monuments are important points of references in our collective memory (Malaud, 2014). They carry memories, experiences and possibilities. In fact, the social significance is so crucial, that if a community no longer appropriates themselves to a monument, the life of this heritage comes under threat (Gantius, 2020). That is why transformation is so important: heritage survives through its persistence of transformation. Sustainable heritage is an infrastructure which can take a multitude of functions shaped by the social and cultural framework (Malaud, 2014). The ‘Deep City’ approach stands by this idea: participation of the community and other stakeholders heighten the chances of a successful process. During this process, architects are mediators. They should evaluate the ambitions of all agents, and at the same time protect the transformative quality of heritage to leave the door open for future generations.

The discussed alternative practices are a balancing act: the approach is not always straightforward. A thorough analysis and cooperation of different stakeholders is necessary. The difficulty in these approaches lies perhaps with the non-specific procedure. It is more intuitive than the traditional ones and will require more time and effort.

45

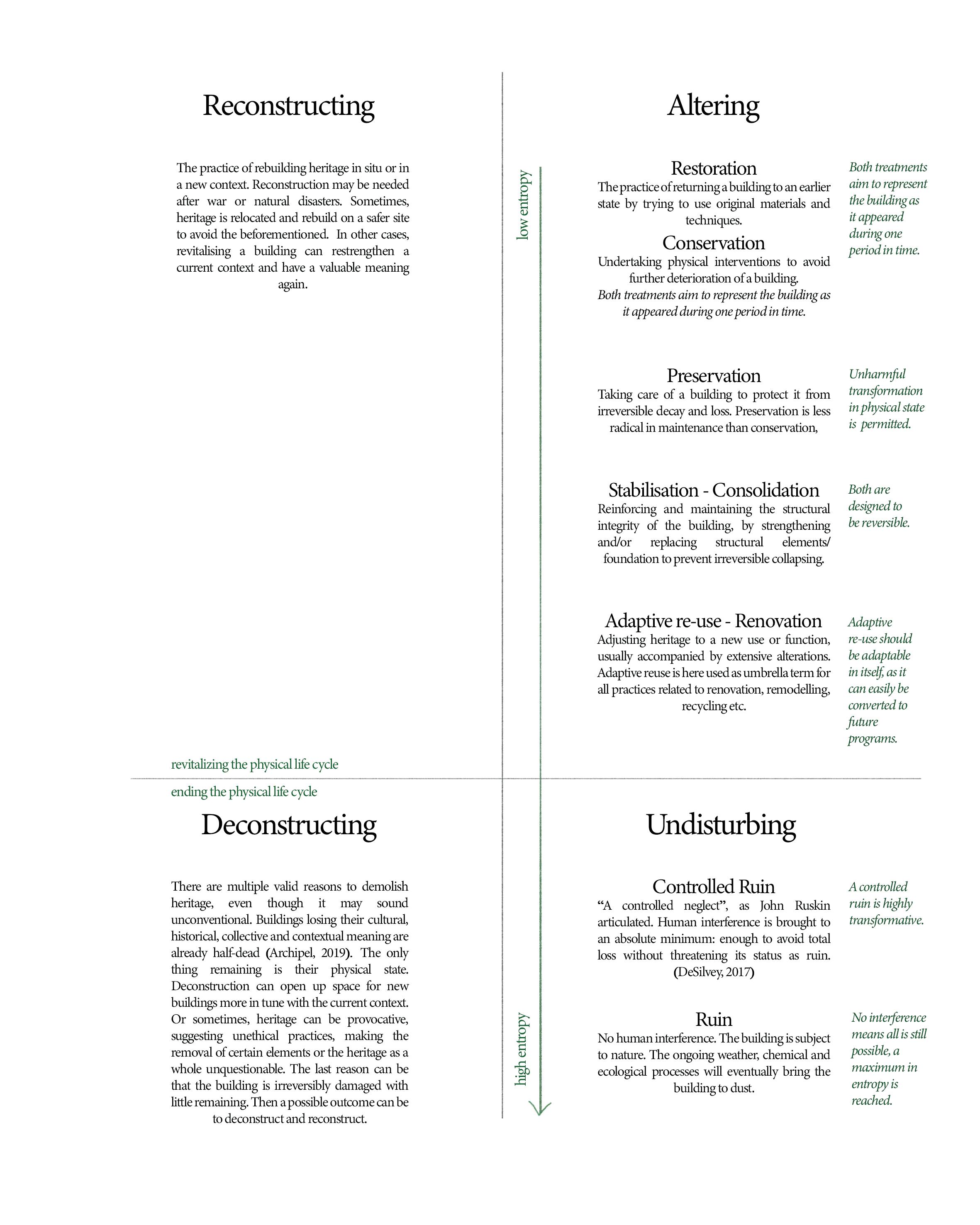

A Palimpsestic Heritage Practice

My Design Philosophy

From both the traditional and experimental discourses something can be learned. An appropriate architectural answer for a palimpsestic landscape, such as Noeveren, probably lays somewhere in between. Some entities are worth being conserved to protect from physical loss, other buildings should be reinvented in other forms. Besides a palimpsestic design methodology where multiple aspects of the visible and invisible are layered (such as in materials, accessibility, meanings etc.), I further advocate for implementing a layering in treatment in future heritage practices.

Instead of conserving a building or site in its totality, we, as architects, should decide which aspects need to be conserved in a traditional way and which don’t. A layering in treatment will force the architect to perform an extensive analysis to understand the intrinsic, material and cultural values of all involved entities. This way, a better estimation of treatment can be given. Curating a landscape with a diversity of treatments (controlled ruins, conserved facades, experimental adaptive spaces, decaying sheds where birds live etc.) can give opportunities, that can be overlooked in a more monotonous heritage practice.

In the following paragraphs, I shortly substantiate three statements in how a diversity in heritage treatment can provide an answer to issues we are confronted with today.

A PALIMPSESTIC HERITAGE PRACTICE IS MORE FINANCIALLY FEASIBLE LONG-TERM

Considering the financial burden of many monuments, we could ask ourselves: what is the price of conservation? And who will pay? The more we opt for conservation, the bigger the total costs for maintenance will be. This will only increase, keeping in mind the environmental changes threatening our heritage. If we lessen our conservation urge and favour minimal intervening, or even zero interference, the total costs will obviously be reduced. Sometimes stabilising a building and opening up the façade is already enough to catalyse a desired reaction long-term. Eventually when expenses are spared, their will be more capital left to actually maintain the conserved heritage.

A DIVERSITY IN HERITAGE TREATMENTS WILL MOST LIKELY RESULT IN A DIVERSITY OF USERS.

Generally, the conservation costs of heritage are paid back by tourism or other profitable activities. What does it mean socially, if a building becomes a moneymaking monument? Conservation for educational and touristic purposes isn’t in itself a bad thing, but it may not exclude locals and affect their relationship with heritage in a negative way. Aiming to keep this framework of the collective memory active, it can be refreshing to opt for other heritage practices. Sometimes doing the minimum as an architect and letting the local community do the further implementation of a building can be really effective. When locals are given the chance to transform the building, they will slowly claim it back as their territory (Gantois, 2020). And with that the collective memory keeps on existing and growing.

A LAYERING IN TREATMENT MAKES A BUILDING MORE RESILIENT FOR THE FUTURE.

One of the main purposes of implementing a palimpsestic heritage treatment, is to encourage transformation.

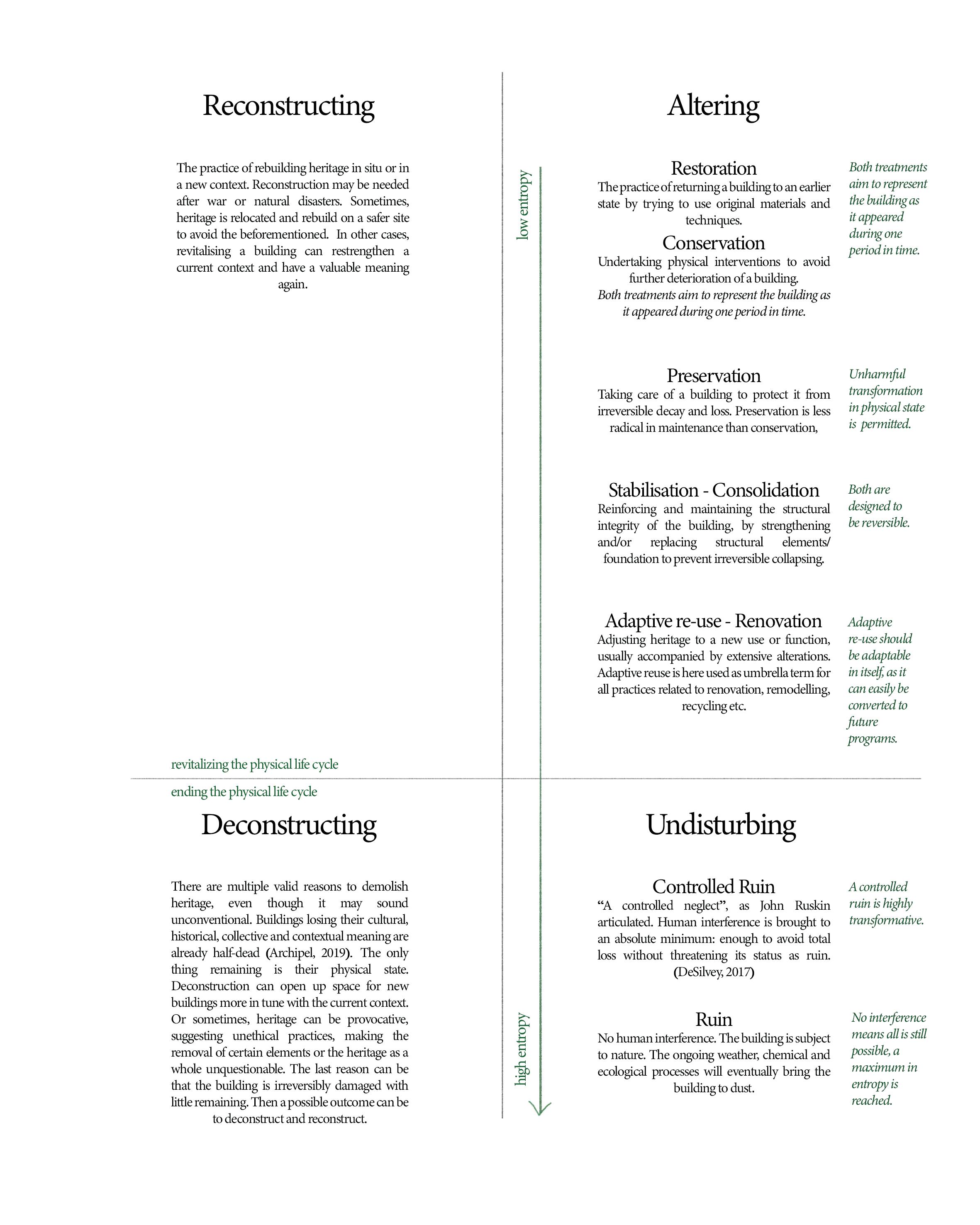

In fig. 27, the degree of entropy related to each treatment is indicated. This is based on the theory of DiSilvey, where she understand a high entropy as an increase in opportunities and possibilities (DeSilvey, 2017). When stepping back from conserving extensively and being open to less permanent treatments, we create opportunities for future others to decide, engage, experiment... We leave space for new narratives, who are needed to keep heritage relevant. This metamorphic nature will also be needed when coping with climate change. Luckily, most heritage typologies/sites lend itself to those changes, they have the capacity to take many appearances (Malaud, 2019). They have proven their persistence over time and will keep doing so if we give them the freedom to do so.

46

fig. 27 Spectrum of Heritage Practices partly based on the work of Caitlin DeSilvey (DeSilvey, 2017) and Fred Scott (Scott, 2008).

Case Study - Site Lauwers

fig. 28

Distant view on site Lauwers.

48 | Site Lauwers chapter 4

chapter 4

INTRODUCTION

Site Lauwers is one of the three remaining brick making factories of Noeveren, most south situated. In 1981 the site, previously called the Novobric Factory, was bought by the brothers Lauwers. When they took over the factory, modernisation of the buildings had already taken place. Beside some replacements of old dry sheds into modern ones, and remodelling the garage boxes, nothing drastically changed after 1981 (Buggenhout & Piffet, n.d.). In 1986, Noeveren got declared as protected village site, because of its unique industrial history. At that point, site Lauwers was the only active brick factory in Noeveren. The other two, site Frateur and site Peeters-Van Mechelen, were already closed. The label of protected village comes with certain regulations and expectations. When reading this Decree, it is remarkable how little is written about site Lauwers (MD, 1986). As this was still an active factory and also the most modernized of the three, authorities turned a blind eye to this site; as it was not really possible to mould this building inside the heritage framework they envisioned. Site Lauwers stayed an active factory until 2006 (Buggenhout & Piffet, n.d.).

Since 2006, a process of slow decline started, structurally but also in its meaning, still continuing today. Overgrown by nature, completely closed off with gates and fences, it doesn’t feel welcoming to approach. The main building specifically became victim to squatters and vandals, which didn’t improve the perception of the site.

However, besides being seriously damaged, the site has lots of opportunities. Each building carries intrinsic qualities, making it extremely diverse and layered. Perhaps, it is rather fortunate that the site hasn’t been transformed yet. Now that time has past, we can evaluate the other two factories and seek for new interventions Noeveren is missing.

On the following pages, two inventarisations will be addressed; the first one being an overview of all the building part of site Lauwers. This inventarisation is focussed on the material, the visible. This is followed by an photographic collection of some buildings, with notes regarding the feelings, stories and experiences that these places recall. I will end this introduction with envisioning my strategy for the site.

49

Introducing the site

kleiplein

fig. 29 inventarisation of the buildings on site Lauwers

Brick press

Clay Shed

Dry tunnels

Shaping hall Administration

Sanitary Accomodation Storage hall + dry tunnels Storage hall

fig. 30 layout of the brick factory

Introducing the site

Introducing the site

PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION

site Lauwers through experiences, stories, impressions

Rooftops intoxicated with asbestos and showing severe decay. On the other hand make the openings the growth of vegetation possible.

Some call it vandalism, some call it art.

fig. 31

The interior of the clay shed (11b) today.

52

|

Site Lauwers chapter 4

The only visual contact with site Lauwers is a far glimpse on the chimney .

The dry sheds on the Kleiplein [Clay Square] are today replaced by trees and bushes. Some older locals recall the days they came playing here in ‘t Geleeg. The dry sheds were the perfect spots to hide. Even though, today there is a playground, children do not play here anymore. In fact, it is no longer a place where people spend much of their time. It has become an extension of the garages, where people drop their car.

fig. 32

Today’s view on the Kleiplein [Clay Square].

53

Introducing the site

fig. 33 Small clamp kiln.

Nature has partly swallowed the small clamp kiln. It seems to disappear in the bank of the Rupel.

54 | Site Lauwers chapter 4

fig. 34 Large clamp kiln.

A real life scenery or a Romanticism painting?

55

Introducing the site

fig. 35

As if the abandonment and severe decay isn’t discouraging enough to ban passers-by, the brother Lauwers placed a bright yellow gate to completely close off the site.

56 | Site Lauwers chapter 4

Street view on site Lauwers.

DESIGN STRATEGIES

Introducing a new narrative, where the duality of working and living is re-established.

Improving the accessibility of the site.

Introducing new protagonists.

Creating a layering in social permeability, considering all the protagonists.

Understanding heritage as a generator for new narratives, rather than heritage as stagnant objects.

Leaving space, free for imagination and spontaneous interventions.

Make ways for bringing water and vegetation inside the building.

Implementing a layering in heritage treatment to keep this degree of diversity present in the landscape.

57

Introducing the site

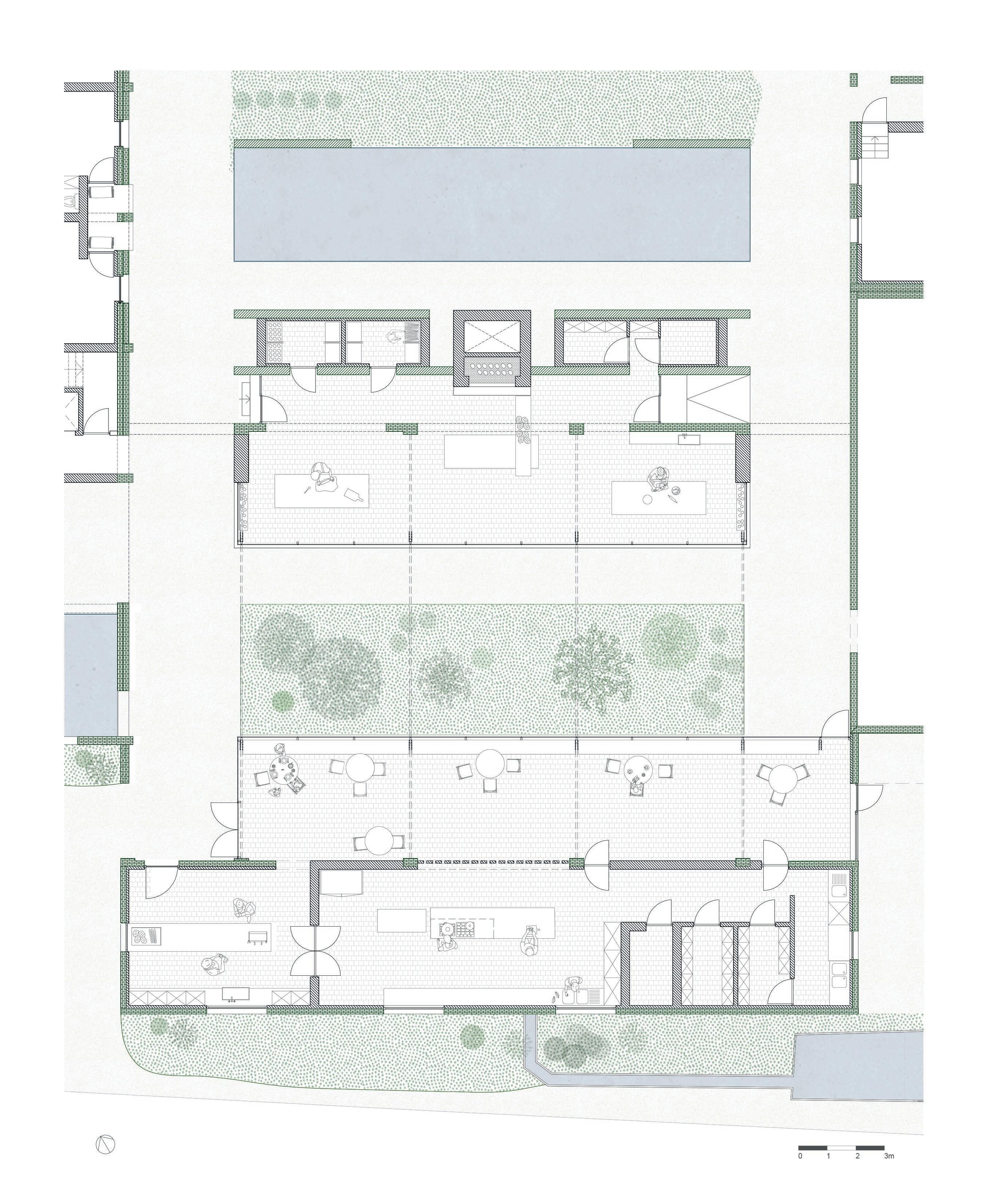

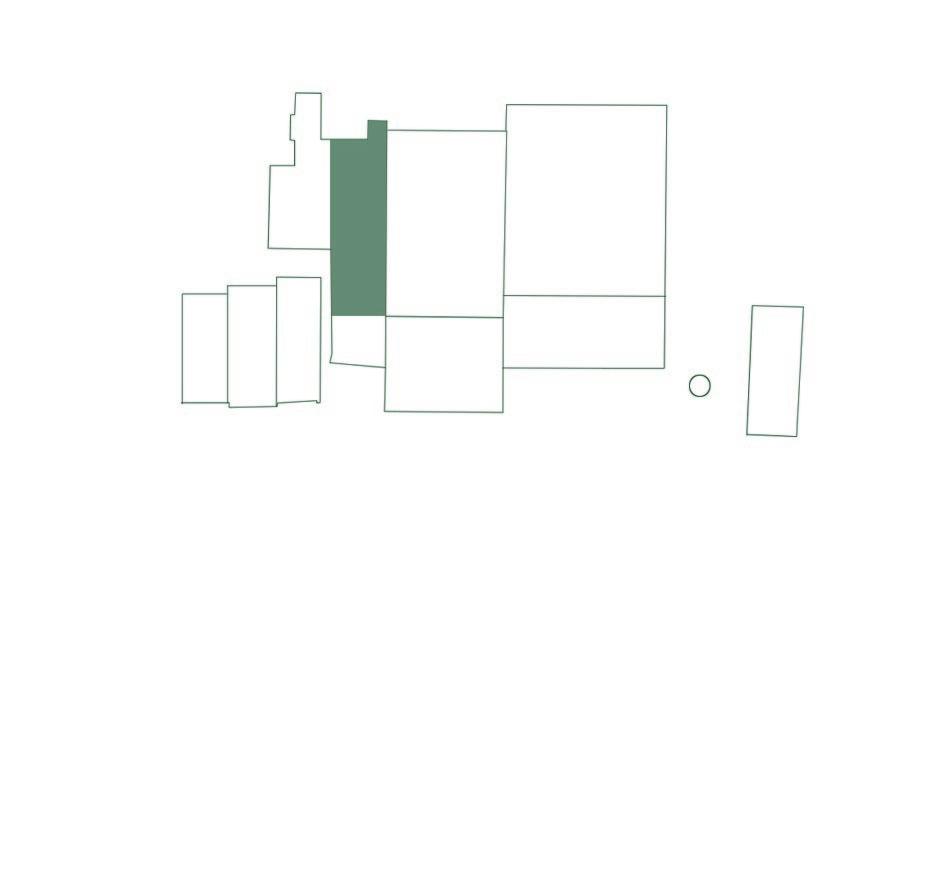

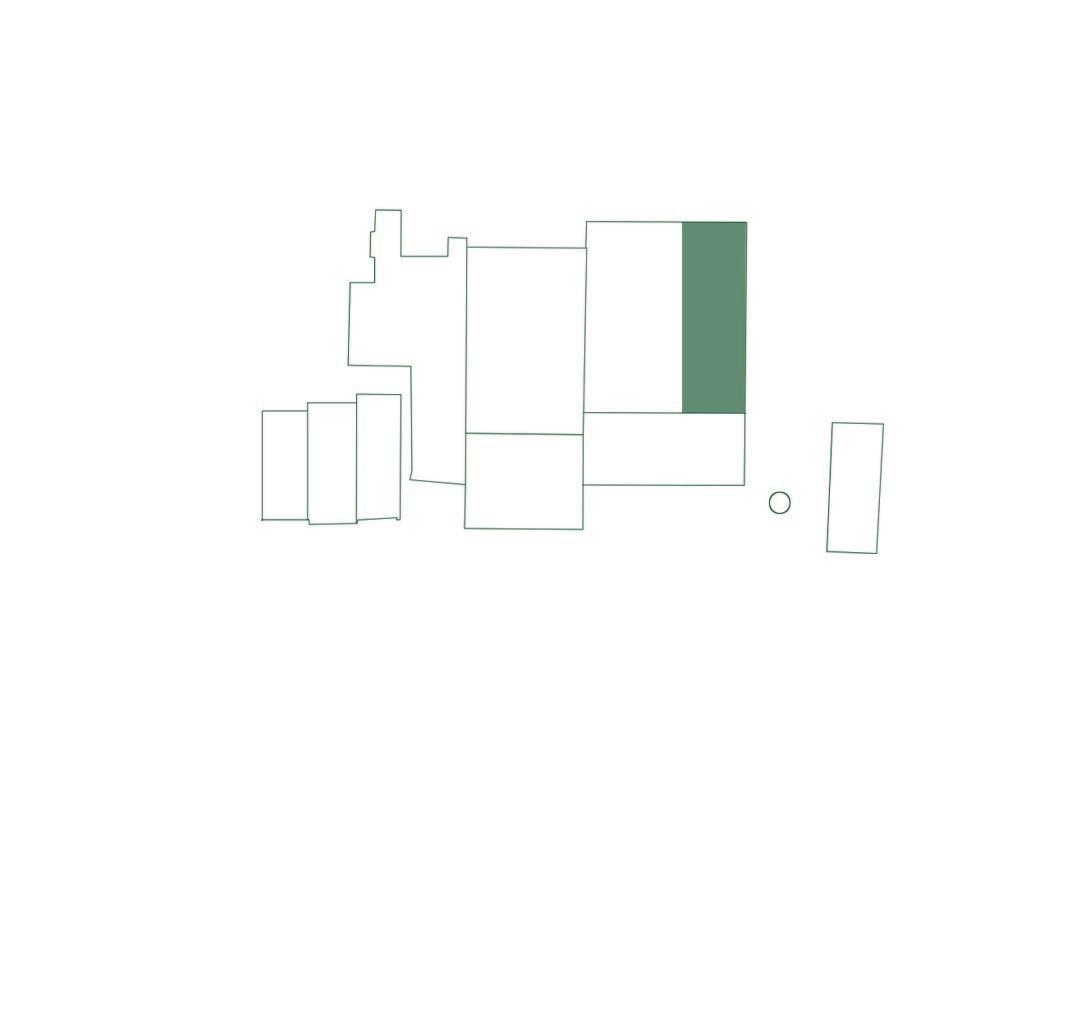

Envisioning the Masterplan chapter 4 part 1

58

| Site Lauwers

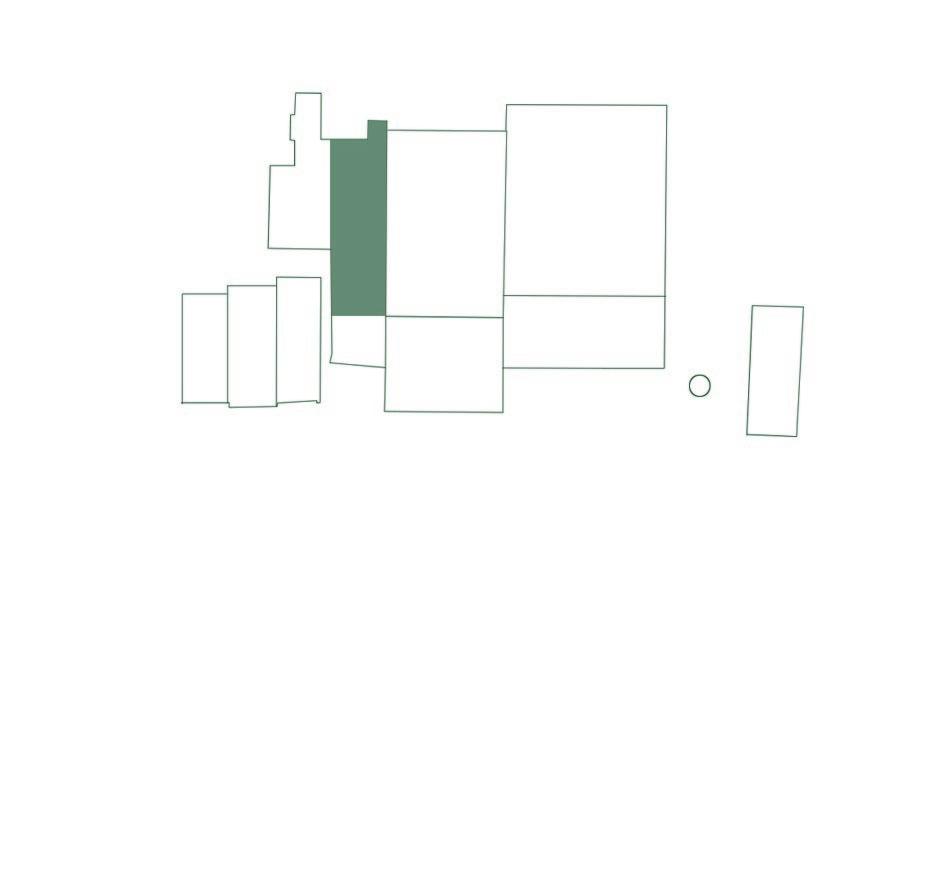

The first step in curating site Lauwers is deciding on what treatments (or the lack of it) will be implemented on each building, keeping the intrinsic qualities, the historical context and their value in mind. On the first plan, this layering in treatment is visualised, together with the heritage treatment scheme previously mentioned in the design philosophy.

Linked to the treatment is the accessibility of the site: how will locals and visitors experience these adaptations? On a following plan, the possible walking lines of the protagonists are drawn. It gives an idea from what corners the site is reached and where protagonists meet. Making the site accessible again and attracting different groups of users is an important given to reintroduce the site again in the daily life of Noeveren.

59

Masterplan

Layering in heritage treatment

boxes

Garage

fig. 36 Masterplan with the different hertiage treatments

Accessibility

fig.37Accessibility masterplan with indicated interventions

By re-opening the tunnel underneath the main street, the pedestrian connection between the clay pits will be repaired. This can be interesting for tourism, as visitors will be able to walk from the museal site ‘t Geleeg to site Lauwers by using the traditional route through the tunnel. Redirecting the tourist route from main street to lower-laying pedestrian paths also means that the locals will be less confronted with their presence.

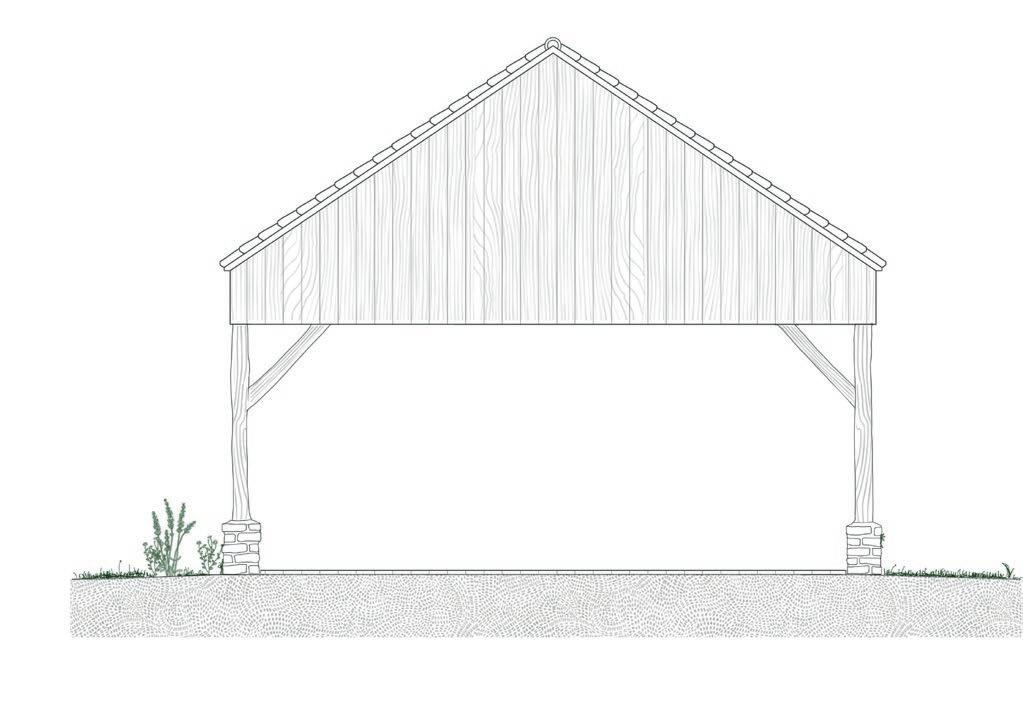

The dry sheds works as directing element to guide visitors from the tunnel to site Lauwers.

The restored Paepe Oven is an important relic of the brick industry past. Together with the restored entities on site Frateur and EMABB, it creates a historical narrative of Noeveren that visitors hope to experience. Today, the museums aren’t connected with each other, in fact their relationship is quite competitive. I hope with my design to reconcile all the historical relicts into one story.

Bringing hikers through a small pathway up to the Rupel. En route to the river, a glimpse of the ruinated large Clamp Kiln can be seen. Visitors experience heritage from a completely different perspective in this area; it reveals the beauty of loss. Further on, when walking between land and river, the small Clamp Kiln can be seen, showing even further decay. See fig. 33 and fig. 34.

The car traffic of visitors (tourists and consumers) will be concentrated on the Nielsestraat. Their access to the other streets won’t be allowed. When visiting Noeveren, cars can be parked on one of three provided areas (from north to south): a small parking lot for the new inhabitants and their guests, in front of the old Paepe oven one for clientele and consumers, and lastly the car park that belongs to the neighbouring businesses. This last parking lot is unused during the weekend, so lends itself as parking space for tourists during these days.

Masterplan

Introducing a new narrative

64

| Site Lauwers chapter 4

chapter 4 part 2

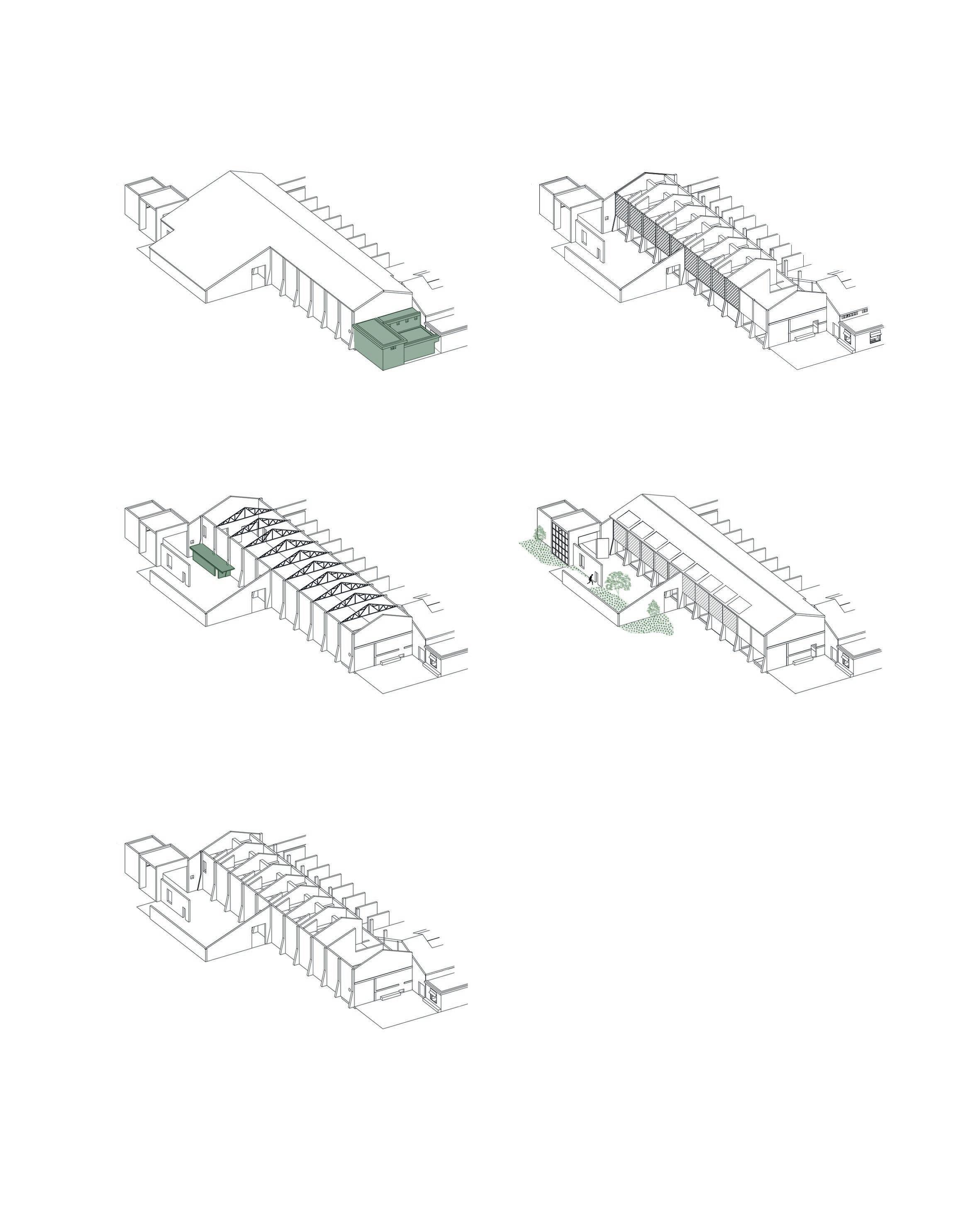

In the main industrial building, a new narrative will be introduced. Before discussing each building, I will give an overview of the new program and how the functions are interconnected. The new narrative could be compared to a chain of functions all supporting each other.

Narrative

Iconographic introducing the program and protagonists

possible employment for (new) inhabitants visual interaction walking routes making spontanuous encounters possible the protagonists: new inhabitants community Noeveren locals from outside Noeveren tourists, hikers, city-dwellers

66

fig. 39 Iconographic | Site Lauwers chapter 4

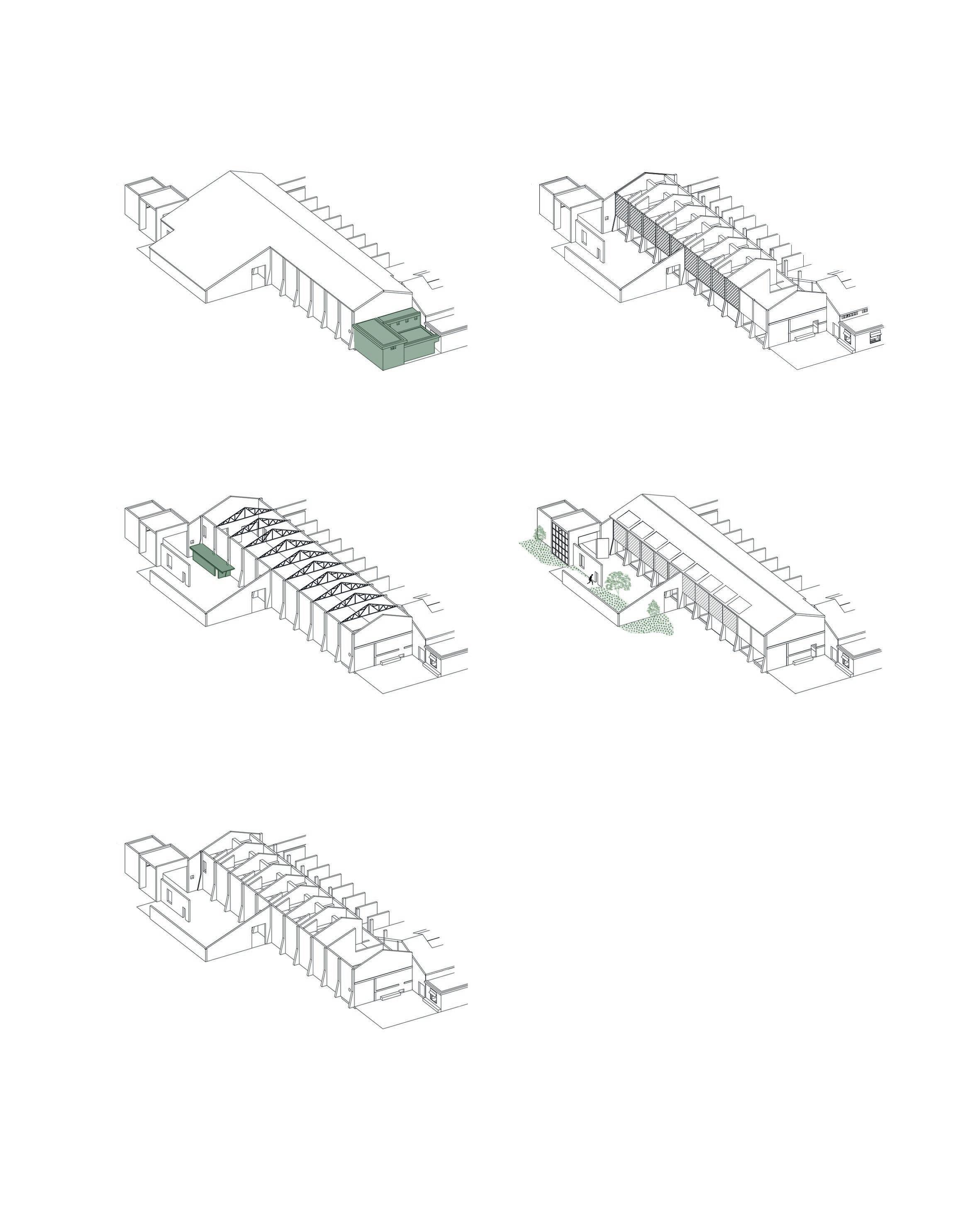

Architectural interventions

68

| Architectural Interventions chapter 4

chapter 4 part 3

fig. 40 - Overview of the main industrial building and its surroundings

In the main industrial building, a new narrative will be introduced. Before discussing each building, I will give an overview of the new program and how the functions are interconnected. The new narrative could be compared to a chain of functions all supporting each other.

69

Architectural Interventions

70 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 41 Collage of the front facade of the bakery where people wait in line

Bakery and Restaurant

The bakery and restaurant have a central role in the new narrative. It is a meeting place where all involved actors can meet and interact. Standing in line, waiting for their bread, opens up conversation.

71

Bakery and Restaurant

Why a bakery?

A bakery will ensure daily activity on the site. Not only from the new inhabitants, but also the existing community of Noeveren will be drawn to site Lauwers to buy a bread. This way, the site will be reintroduced to the community: they will create new narratives, mostly through social interactions by perhaps waiting in line and talking to their new neighbour.

Another more practical reason, is the fact that there is no bakery in Noeveren or close proximity today. The closest bakery is a 15 minute drive. After discussing this idea with the inhabitants and municipality, it became clear that the long distance to the nearest bakery is a problem.

Lastly, a bakery and restaurant means employment. One of the main aims for my thesis is to reinforce the work-living duality.

fig. 42

Architectural interventions to transform the old shaping hall into a bakery and restaurant.

72

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

Bakery and Restaurant

the Art of Traditional Bread Making

In Noeveren, handicrafts have for a long time during history been part of the daily life of the community, mainly through the process of brick making. But also today ‘Noeverians’ [people living in Noeveren] still like to spend their time tinkering, making art pottery, gardening, woodworking… Coincidence or not, this handicraft seems to fit the slower way of living Noeveren exudes. Therefore, in my research to get an understanding of how bread is made in bakeries, I quickly realized the process of traditional bread making would be way more fitting than an industrial one. I visited a traditional bakery in Mechelen, called the ‘Broodbroeders’ to inform myself on the topic.

Making a traditional sourdough bread takes up to four days, so flavours can develop themselve more. By letting the bread rest in different phases, it works itself. No intense kneeding is needed. This means expensive equipment can be limited: a mixer, two fridges and an oven are the only appliances needed. Going back to traditional procedures, the baker has to use his senses and intuition more: touching the dough, smelling and observing carefully, making the artisan process of baking bread, more of an intuitive art, than a fixed science.

74

intermezzo

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 43 - Bread tugged in between cloths to get support while rising.

In addition, slow-food sourdough bread is sustainable in multiple ways. Evidently, energy-wise, less electricity is used. Ideally, the oven is hybrid, so the baker can switch from wood burning to an oven on electricity depending on the weather conditions. Another sustainable aspect is the use of fermentation baskets and rising cloths (see fig. 43) which can be recycled every day.

However, sustainabily isn’t only about limiting waste and using local, sustainable resources. According to Broodbroeder founder, Johan, sustainability also has a social meaning: he advocates for a sustainable work environment with reasonable hours. Because of the four day process, bakers don’t have to wake up during the night to start the baking process.

During my visit to Broodbroeders, Johan gave me a clear vision on how to organize a bakery. As for the organisation in plan, three main areas are needed: one for preparation, one for mixing and one for baking. And yet again, he reminds me of the importance of the well-being of a baker: the most important architectural elements should be daylight and enough space. The little dark back houses, so typical for small bakeries, should be avoided at all costs.

75

Bakery and Restaurant

1 2 3 4 5 8 6 7 9 10 11 4 5 7 9 12 12

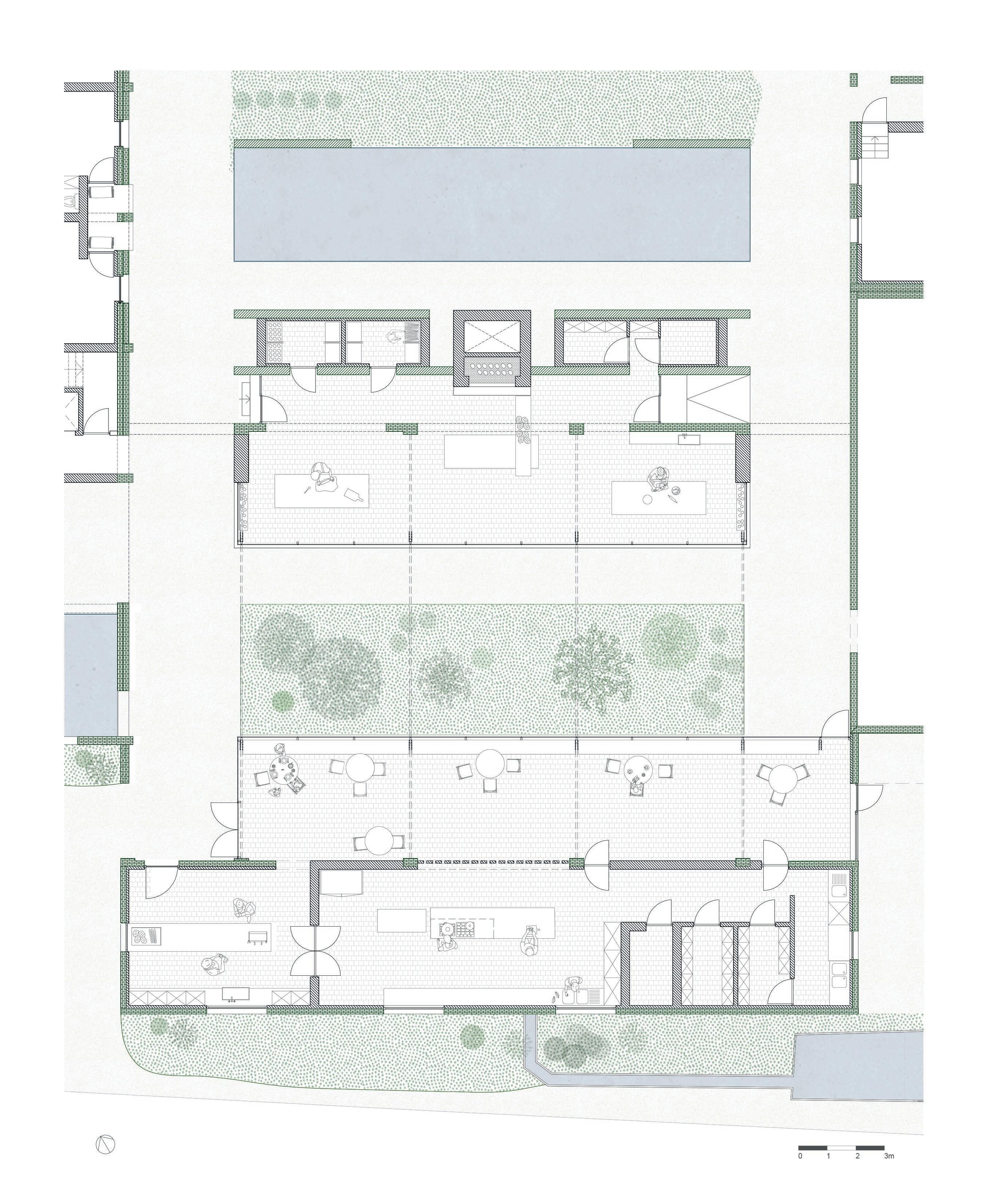

fig. 44 Floor plan of the bakery and restaurant

Design notes

The restaurant and bakery are organized around a patio with a central wadi.

The proof rooms (9) are placed inside an old drying tunnel. This is a small reference to the old function. Nowadays, it is no longer bricks that rest there, but bread.

The bread oven introduces a new typology of chimney on site Lauwers, clearly different in shape and height (see section).

New Construction

Old Construction

4 cold store 5 dry storage 6 utensil storage 7 washing area 8 bakers atelier 9 proof room 10 wood oven 11 wadi 12 water buffers

77

Bakery and Restaurant

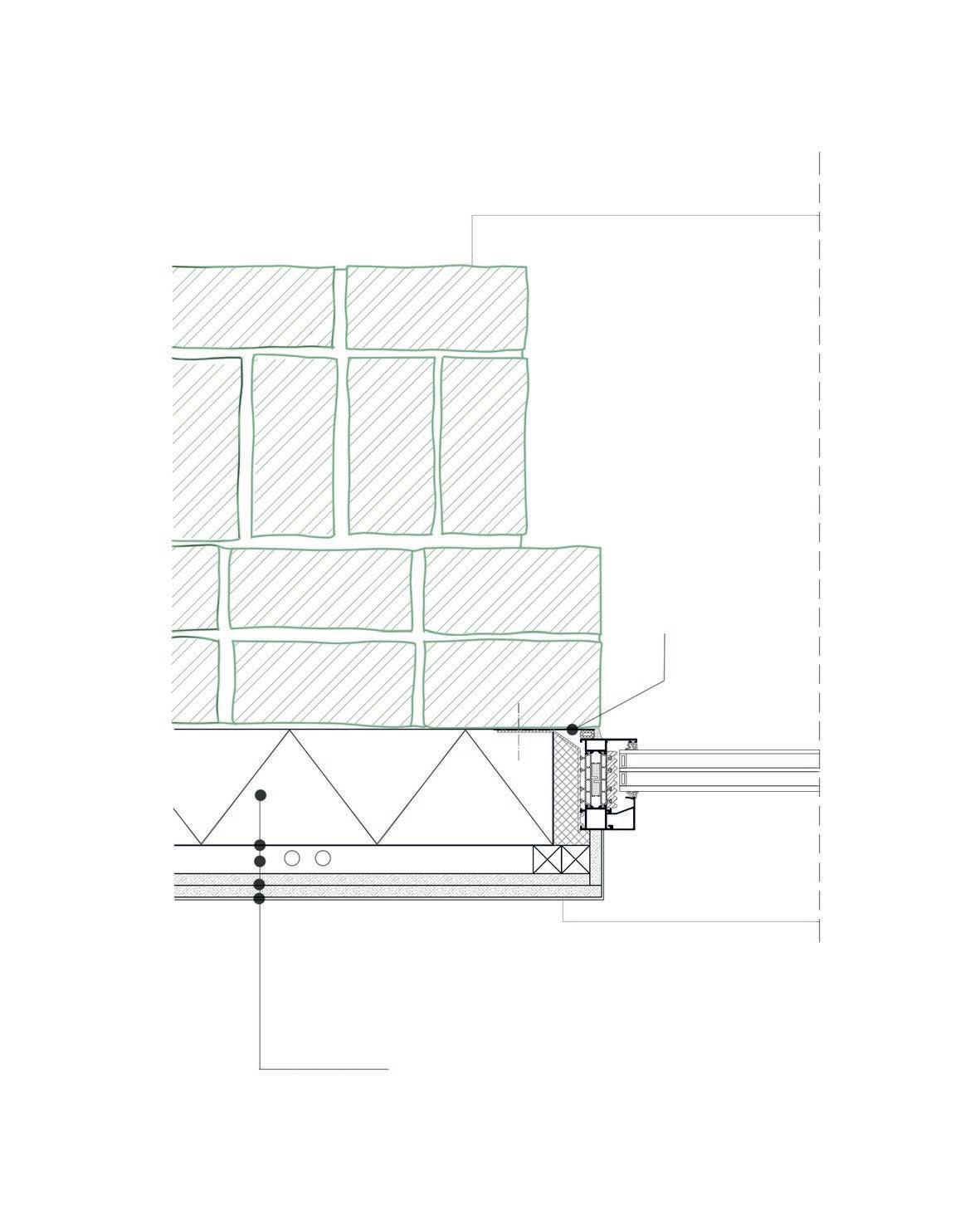

fig. 45 - Three-dimensional section of the restaurant and bakery.

Roof tiles - Boomse Clam

Battens 30 x 40 mm

Ventilation cavity 30 mm

Roof decking 18 mm

Thermal insulation 70 mm

Thermal insulation 120 mm

Vapour barrier Plasterboard 12,5 mm

Plasterboard 12,5 mm

Vapour barrier OSB 18 mm

Thermal insulation PUR 90 mm OSB 18 mm

Insulation panelling 30 mm Ventilation cavity 30 mm Battens 35 mm Wood panneling 20 mm

Floor Finish - Tiles 18 mm

Screed 60 mm

Thermal insulation PUR 90 mm

Waterproofing membrane Concrete 250 mm

80

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

EXTERIOR INTERIOR

Dark wooden panelling, inspired by the panelling on the dry sheds

Steal structure curtain wall

A plinth of masonry, using Boomse ‘brick’

fig. 46 -left

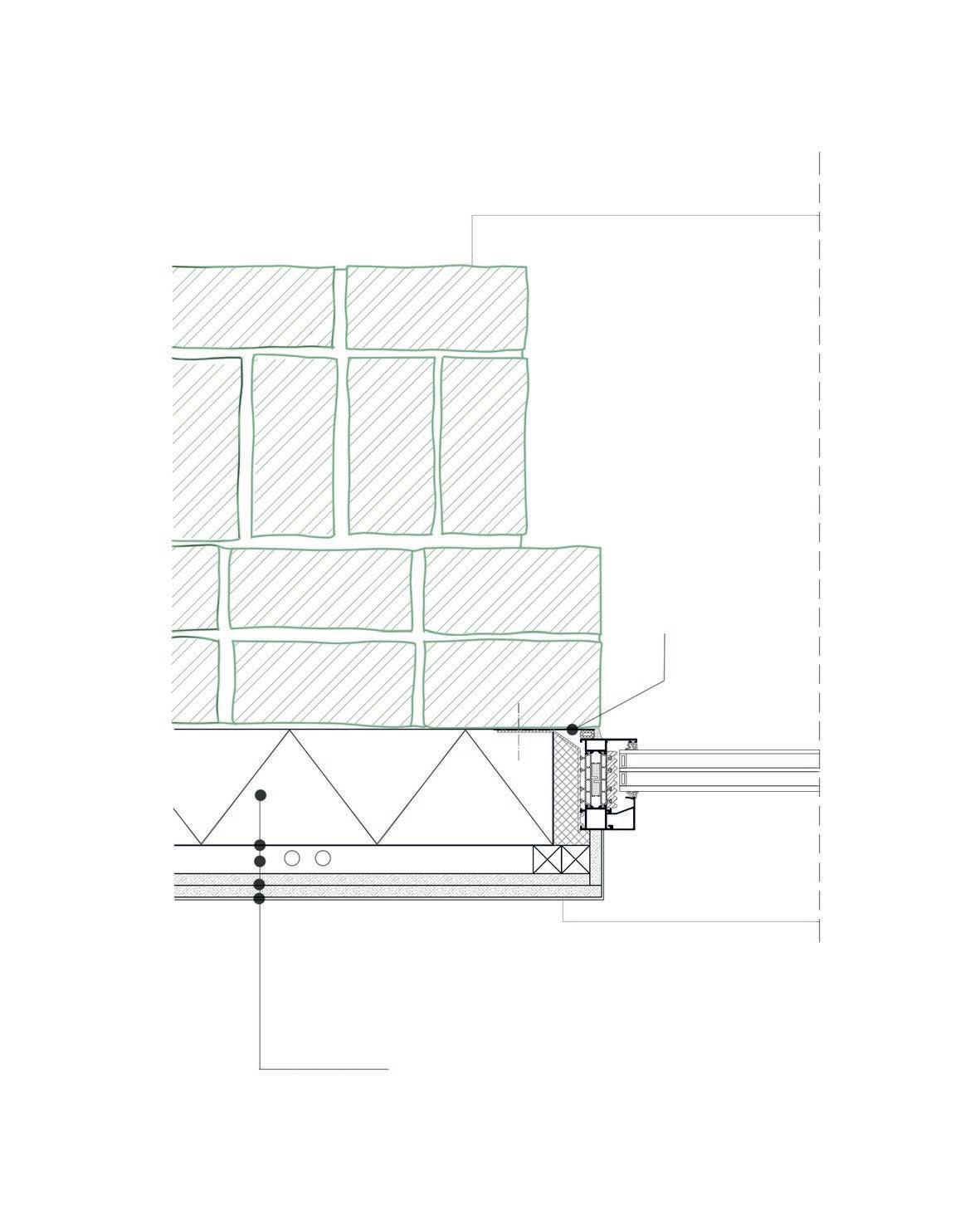

Vertical detail of new construction of the bakeryconnection of the curtain wall to the roof and foundation

fig. 47 -right axonometric drawing of the facade with indication the materials

Bakery and Restaurant

82 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 48 - Facade of the new houses

83 Housing

fig. 49 - Horizontal dichotomy

Current housing typology in Noeveren

As mentioned in the analysis, the houses around the former clay pits exist of a front house and a back house. This phenomenon is a consequence of the topography and work-living organisation during the brick era. The horizontal dichotomy between front and back house is interrupted by a unique “interspace”, as the Averechtse road, where inhabitants interact with their neighbours, and where the informal communal life takes place (Gantois, 2021). For the community, this

fig. 50 - One of the many alleys in Noeveren

84

Housing variant on site Lauwers

fig. 51 - Vertical dichotomy

85

Housing

Housing - east side

fig. 52 - Picture of the storage rooms and central corridor today.

The old storage rooms are organized around a central corridor, that resembles a street. The existing structural grid splits the building in units, ideal for housing.

There are two types of units, and of each type there are six:

Two types of units

Type 1 main house 126 m² additional rooms 58 m²

Type 2 main house 130 m² additional room 19 m²

fig. 53

Transformation of the storage rooms into housing units.

86

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

INTERVENTIONS

1. demolishing rooftops because of the asbestos

2. adding two more units to make the building symmetrical

3. freeing the central hallway and making it a green axis + raising the facade

4. creating patio houses to attract direct sunlight inside

87

Housing

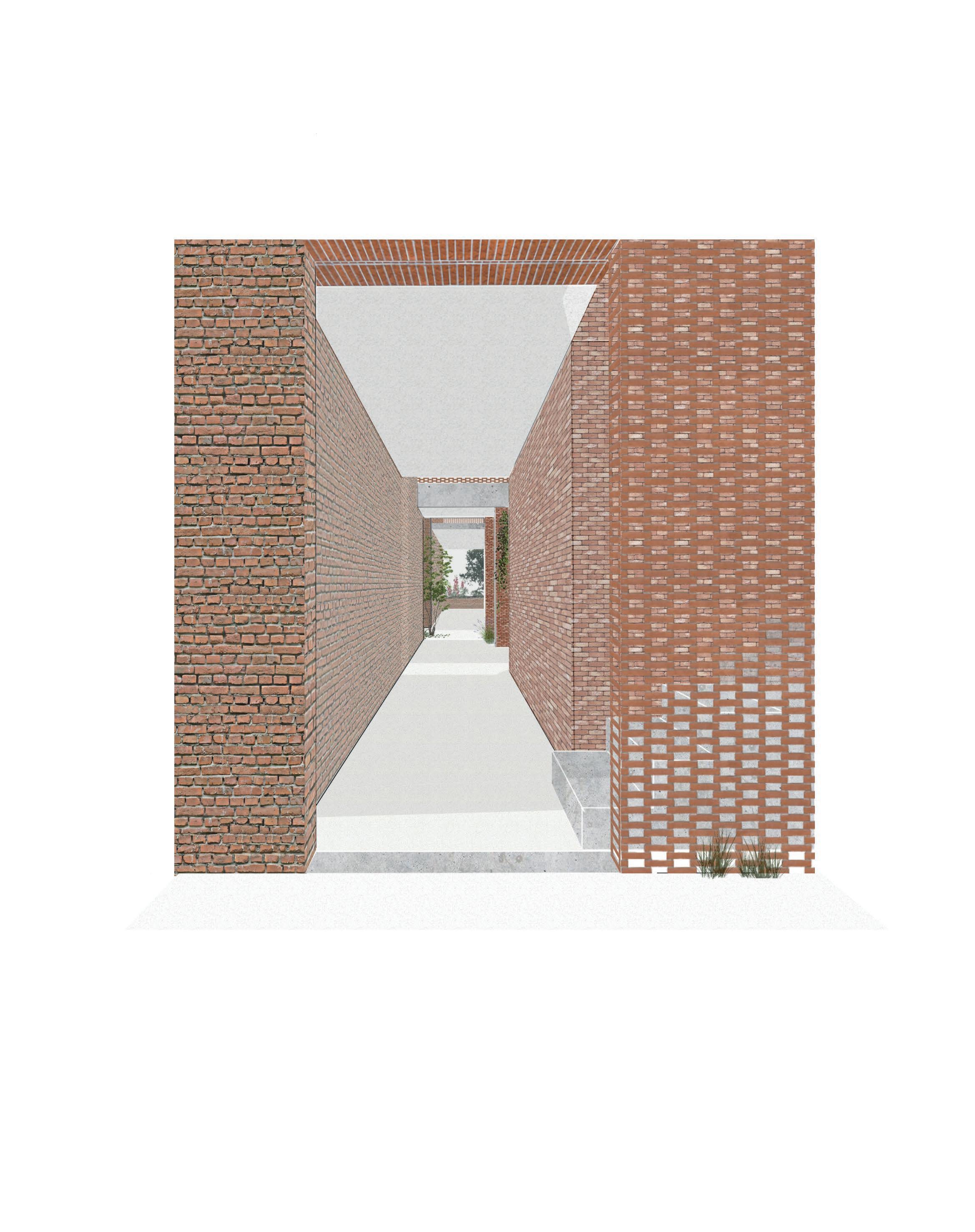

What visitors experience (see fig. 57)

visitor

fig. 54 - Plan of the ground floor

1st floor

2nd floor

fig. 55 Floor plans of the first and second floor

1st floor

2nd floor

fig. 56 - Perspective section of the housing units on the east side of the building

There is more additional living space on the ground floor in these units (58 m²). And so, it would be possible to have an extra living space for one or two persons downstairs. Perhaps elderly family, who can reside here. This unit would be ideal for multigenerational living.

Both units are organized around a patio. The main reason for this, is to bring sunlight into the interior.

In the units on the other side, the extra room is smaller, as a big part of the ground floor is taken in by rental space for services and commercial purposes. Here, the duality of living-working is fully present.

fig. 57 - Collage - a stranger standing in front of the facade.

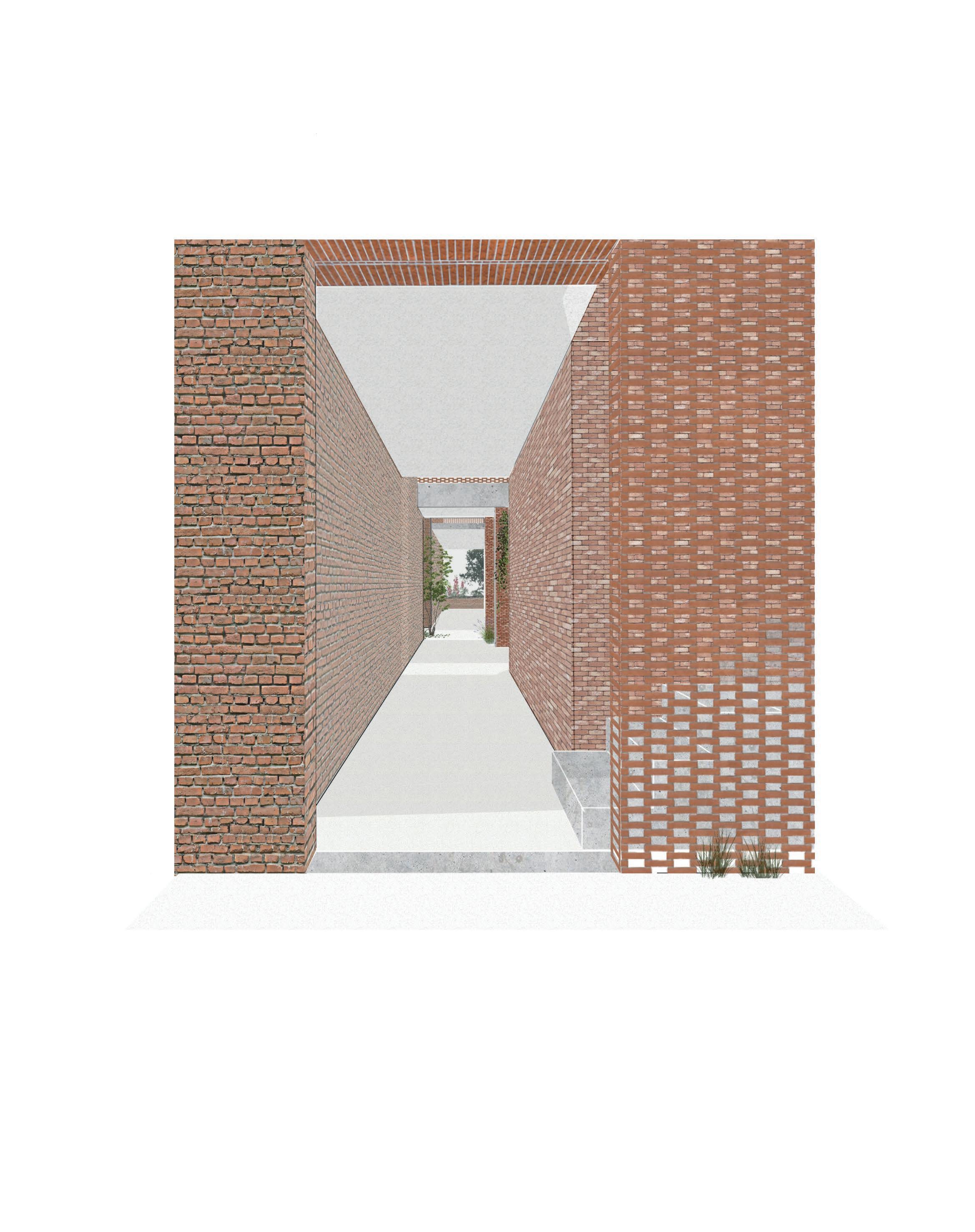

Between the houses and around the patio’s, little alleys and interspaces arise. If you are standing in front of the facade, you will notice a layering caused by these alleys. An interplay of light, bricks and greenery creates depth. As visitor it is unsure whether or not your access is allowed. How far can you enter through this intricacy of space ?

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 58 - Mapping of the collective space around the housing units on the ground floor.

95

Housing

fig. 59 - Facade overlooking the communal garden.

The facade is a patchwork of old bricks, new bricks and occasionly a perforated masonry. The bricks that needed to be removed to create openings, are cleaned and reused to build this perforated masonry. This could be understood as a rewritting of materials. Instead of copying the same masonry, they are recycled through a new articulation. This is a straightforward application of a palimpsestic design method.

Housing - west side

On the other side of the communal garden, in the previous clay shed, there is a second group of housing units. Here too, the units are placed in the existing structural grid.

There are 8 units of the same type:

Type 3 main house 76 m² additional rooms 15 m²

fig. 60

Architectural interventions to transform the clay shed into residential units and atelier spaces.

98

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

INTERVENTIONS

1. demolishing sanitary block and removing rooftops (intoxicated with asbestos)

4. the wall on the side of the Kleiplein will be deconstructed: the bricks will be reused to build a perforated wall as privacy barrier for the housing

2. demolishing sanitary block and removing unstable trusses

5. the old brick press hall will be transformed into an outside atelier space, surrounded by greenery.

3. placing new structure for housing in existing structural grid

Housing

fig. 61 - Perspective section of the housing on the west side.

Design notes

1. The supplementary room on the ground floor can be used as temporal residence for artists. So direct access to the ateliers is possible.

2. The artist-in-residence can use the first floor of the house, where the kitchen and bathroom is. There will be interaction between guest and host.

3. A perforated masonry provides privacy in the bathroom, but lets light come through.

4. The second floor, where the bedroom, living room and terrace are located, is the most private level of the house. The guests don’t enter this part, except if they are invited.

100

fig. 62Plan of the ground floor, where the extra room is occupied by an artist-in-residence.

Housing

fig. 63 Plans of the first and second floor.

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

Waterproofing layer

exterior interior

fig. 64

Horizontal detail: windowold wall

Thermal insulation PUR 120 mm Vapour barrier Battens (cavity for services) Plasterboard 2 x 12,5 mm

HORIZONTAL DETAIL internal wall insulation with new window on two existing brick walls. Besides meeting today’s demands in living comfort, with proper insulation and water- and windproofness, this detail also shows the material layering seen from the outside. The layered construction gives depth to the facade and suggests its original construction. Scale 1.10

103

Housing

fig. 65 - Facade looking from the communal gardens.

104

Same principle as in the other residential building applies here too. The bricks that were removed to make openings are cleaned and re-used to build a perforated masonry.

105

106 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

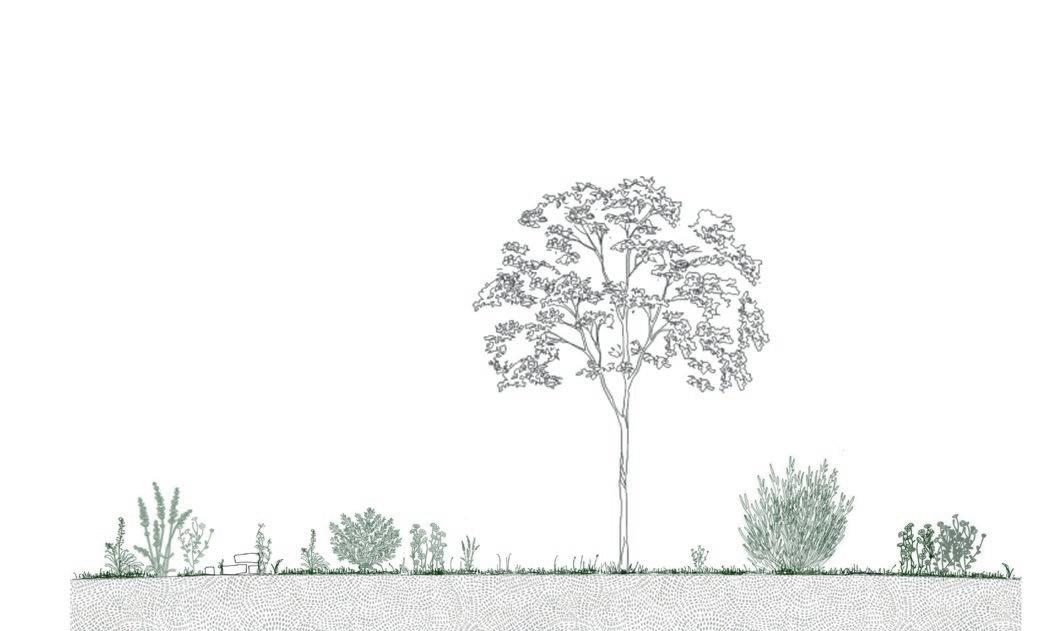

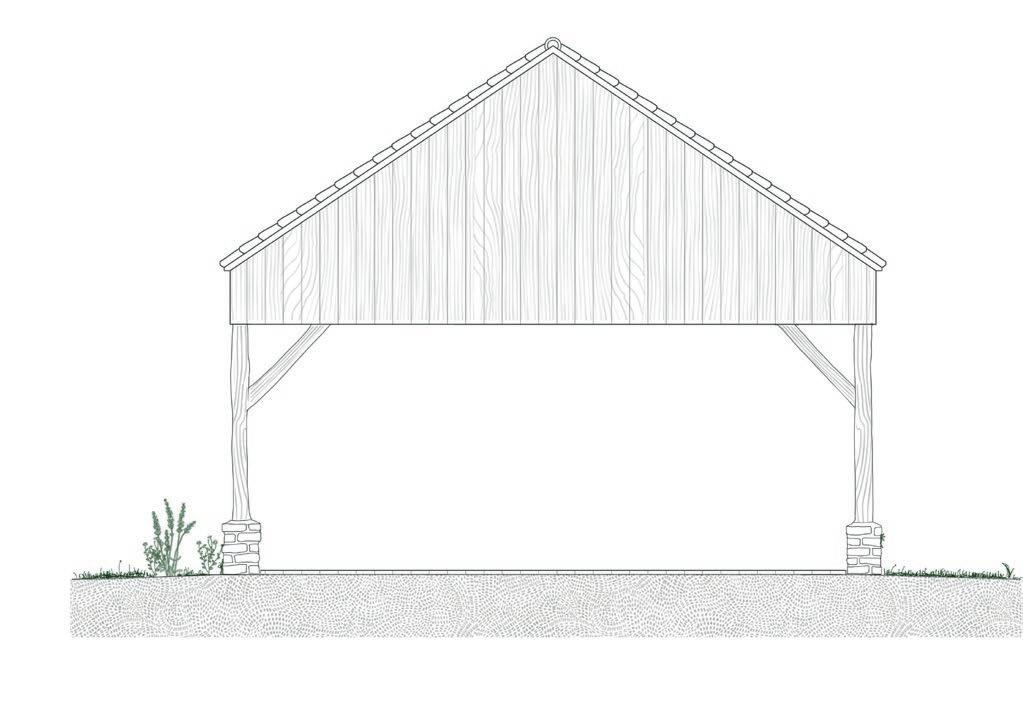

fig. 66 - Illustration of the outside atelier space and exhibition hall, adjacent to the Kleiplein. The new reconstructed dry shed is shown in the background.

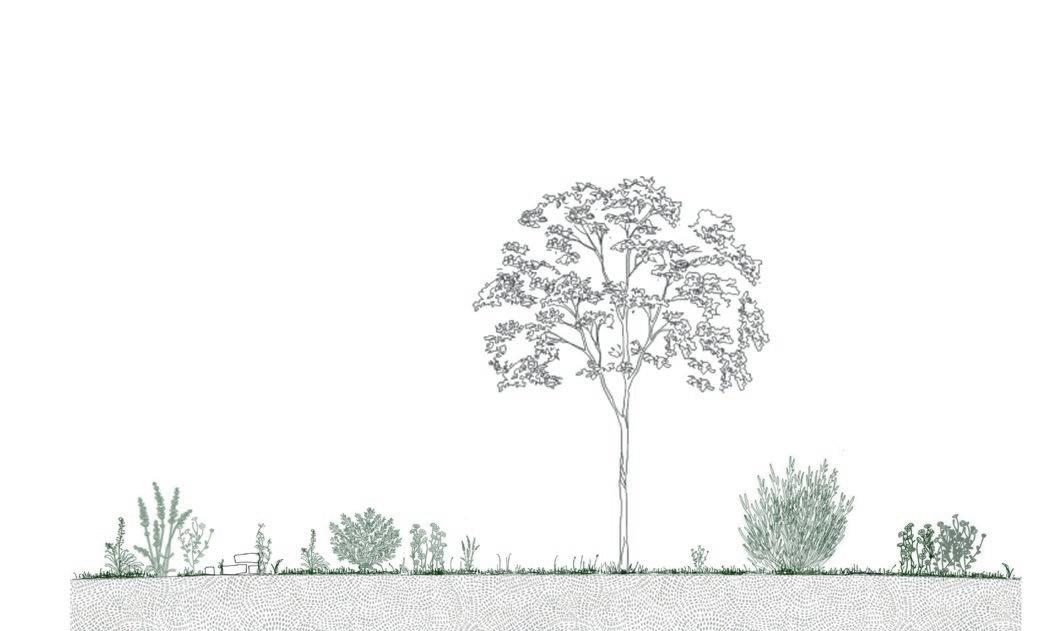

Noeveren with its unique landscape and history has inspired artists to reside in the hamlet and create art of all sorts. But not all artists are coming from outside, there seems to be a general interest in arts and crafts among many inhabitants. Most of them have their own small atelier at home, in a garage box or in the back houses. However, there is not yet one collective space where all artists can work together and collaborate.

107

Ateliers

210 m² 188 m² 511 m²

fig. 67 - Plan overview of the surface areas and their corresponding function.

108

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

technical rooms

fig. 68

Floor plan of the atelier spaces, exhibition space, and possibly the rooms for artists-inresidence.

Design notes

The atelier spaces are located on one border of the Kleiplein [Clay Square]. When the boarder of a square is activated, it often stimulates the activitity on the square as well. The reconstructed dry shed and repaved walking route also helps with this.

The top exhibition space can be used/rented by artists to present their work. If a bigger space is needed, the restored Paepe Oven can be an option as well.

111 Ateliers

fig. 69 - Three-dimensional section of the ateliers, exhibition space and housing, situated between the communal garden and the Kleiplein.

112

113

114 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

Communal Garden

The old drying tunnels will be transformed into a communal garden, where each inhabitant can ‘claim’ their part. An interesting diversity of little gardens will develop itself between the old walls, where the individuality of each inhabitant can be found.

fig. 70 - View from the central green axis on the chimney and all the little gardens that end up in this central green space

Communal Garden

fig. 70 - View from the central green axis on the chimney and all the little gardens that end up in this central green space

Communal Garden

1. Removing rooftops (intoxicated with asbestos)

2. Removing the uneven walls of the drying tunnells to make the in-between spaces wider. Opening up a central axis.

3. Phytoremediation: an intermediate phase - 5 years - to remediate the polluted soil.

4. Communal gardens for the surrounding housing.

116

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 71

Architectural interventions to transform the old drying tunnels into a communal garden

In the communal garden, a situation similar to the Averechte Roat occurs. First of all, a process of appropriation happens. The communal garden is common space, as the name tells. However, when people start to personalise a small part and take care of it, they will in the process start to claim it as it was legally their ownership.

“Ownership, actually of perceived, is a central driver for a successful interspace zone, meaning a zone for social interaction.” (Gantois, 2021, pp. 8)

The gardens will start conversations between neighbours. Conflicts will need to be solved through negotiating, as there are no official easements. One main rule is to keep the central axis open: no hardening, no outbuildings, nor permanent installations.

As a visitor, the phenomenon of a layering in social permeability happening now in the Averechtse Roat will probably also take place in this garden. Similarly, the space is collective, every corner is accessible. Yet through different articulations of appropriation, strangers become aware of the socially determined borders. To enter the central green axis, the individual gardens will need to be crossed.

117

Communal Garden

fig. 72 - left

Floor plans of the communal garden

fig. 73 - right

Possible interpretations of the individual gardens

120 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

Communal Hall

fig. 74 - A rough sketch of how Noeveren Kermis (a yearly activity) could be organised on and around the new square.

Noeveren doesn’t have a central (market)square. There is no church, no typical focal point where the community can meet. Nowadays, they mostly gather around cafe ‘de Koophandel’, or have small markets inside the restored ring ovens. Since site Lauwers is located in front of the cafe, it could work together as a small communal centre and enlarge this ‘unofficial’ gathering point. The open space in front of the communal hall has all the ingredients to become a proper square: water, interesting boundaries and a landmark (the chimney).

121

Communal Hall

INTERVENTIONS

1. demolishing old canopy and removing roof tops

2. reopening the old openings and closing with perforated brick masonry the entry to the housing units

3. closing of the outer shell of the building with new doors, and a new rooftop. The interior layout and design is up to the local community.

122

| Architectural interventions chapter 4

fig. 75 - left

Architectural interventions to transform the old storage hall into a communal hall

fig. 76 - right

Possible configuration of the communal hall: a food market

A communal space/square works, when the community feels attached to it. An important action during the design process of the square and the adjacent communal hall is to involve the community and give them the freedom to actively transform the space. I suggest minimal architectural interventions, and letting the inhabitants eventually determine what this area can mean for them. As said before, tinkering and handicraft is a common activity in Noeveren. I expect they gladly elaborate their plans themselves.

123

Communal Hall

124 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

Commercial Spaces

fig. 77 - Facade of one of the offices

The east-side of the building is next to a business park and car parking. It is the more official side, less informal and lends itself for working activities.

125

post office bike repair shop offices offices GP practice

parking

bicycle storage

fig. 78

Floor plans with possible new functions.

On the floor plan, possible implementations are drawn. The functions are based on the Vision Note that suggests small-scale services, such as a GP practice, a post office, a bike repair shop etc. to bring back this working part in the working-living duality (Gantois, 2018). The spaces could also lend itself as co-working space for small compagnies. After all, Noeveren has an interesting location between Brussels and Antwerp.

Each unit is 60 m² in surface area. Two units are connected with each other by a shared kitchenette and sanitary room.

127

Commercial Spaces

128 | Architectural interventions chapter 4

Masterplan - a synthesis

This chapter ends with a masterplan of the ground floor with the possible walking lines of each protagonists drawn on. This final masterplan expresses the overall permeability of the building. There is a route for each protagonist (locals, inhabitants, tourists, artists...), yet all of them have the possibility to deviate from their usual path. The plan further shows interesting points where the different actors most likely will meet.

fig. 79 Masterplan of the ground floor with the walking lines of all the protagonists.

129

Synthesis

132 | Closing chapter 5

ClosingWith this project, I want to take a position in the heritage field of today. Instead of following blindly the conservation discourse which prefer restoration and preservation, I advocate for an alternative practice that is more transformative, imperfective and nuanced, all qualities the metaphor of a palimpsest entails.

While I focussed on the hamlet Noeveren and the case study Lauwers, this approach can also be applied to other heritage sites throughout Flanders and even Europe. When a heritage landscape slowly reveals itself as a complexity of narratives, it can be a delicate task to interfere. Reading the landscape as a palimpsest and treating it accordingly guarantees a higher chance of succeeding.

Therefore, as architects, we should not strive for a fixed, two-dimensional design. When doing so, we liquidate the real qualities of heritage: its transformative nature, its capacity of carrying a collective memory and its ability to generate future narratives. Instead, we should provide an architectural framework, where some interventions will be more determined than others, leaving room for different interpretations and opportunities. The end result -will be a work in progress, where new narratives are welcomed, a selection of past narratives are fixed, and present narratives can land.

It becomes inclusive.

133

chapter

5

Bibliography

ACADEMIC ARTICLES

Bartolini, N. (2013). Critical urban heritage: from palimpsest to brecciation. Interna tional Journal of Heritage Studies, 20, pp. 519-833.

Gantois, G. (2021). Negotiating everyday vicinity. On Noeveren’s collective use of private ground. Faces, 80, pp. 7-9.

BOOKS

Buratti, Riccardo, Clinckemalie et al. (2015). The Cuesta of the Rupel Region. Volume I (Vol. 1). Faculty of Architecture, KU Leuven; Ghent.

DeSilvey, C. (2017). Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: Universi ty of Minnesota Press.

Gantois,G. (2020). Small-scale heritage: The canary in the coal mine. In Fouseki, K. et al. (Ed.), Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations. Deep Cities (pp. 166184). New York: Routledge.

Fouseki, K. et al. (2020). Heritage and sustainable urban transformations. A ‘deep cities’ approach. In Fouseki, K. et al. (Ed.), Heritage and Sustainable Urban Trans formations. Deep Cities (pp. 1-15). New York: Routledge.

Malaud, D. (2020). From modern utopia to the ‘deep city’: Heritage as history, collec tive memory and embodied energy. In Fouseki, K. et al. (Ed.), Heritage and Sustai nable Urban Transformations. Deep Cities (pp. 16-34). New York: Routledge.

Scott, F. (2008). On altering architecture. New York: Routledge.

CONFERENCE

Maria Balshaw, “The (Heritage) Elephant in the Room,” Heritage Exchange 2014, http://www.heritageexchange.co.uk/.

134

DOCUMENTS

Buggenhout, S. & Piffet, R. (n.d.) Erfgoedtoets.

Gantois, G. (2018). Ik Zie, Ik Zie wat Jij niet Ziet. Visienota omtrent de wijk Noeveren. Gemeente Boom. (2022). Erfgoedbeheersplan.

Vlaamse Gemeenschap. (July 25, 1986). Ministrieel Besluit, houdende bescherming van monumenten, stads- en dorpsgezichten, Noeveren (Boom) [MD]. Accessed on May 15, 2022, https://besluiten.onroerenderfgoed.be/besluiten/2176/bestan den/6698.

BOOKLET

Archipel vzw. (2019). Palimpsest [Booklet]. https://archipelvzw.be/storage/files/Pu blication/352/cahier007lores.pdf

WEBSITES

EMABB. (n.d.). Ten Oever aan de Rupel. Accessed on May 6, 2022, http://www. emabb.be/old/Nl/nl TenOever.htm

Groen Boom. (2020). Dossier: De kleiputten. Accessed on May 16, 2022, https:// www.groenboom.be/dossier de kleiputten

135

136

List of Figures

fig. 1 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 2 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 3 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 4 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 5 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 6 - picture and collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 7 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière

fig. 8 - section, drawing by Astrid De Mazière, based on EMABB. (n.d.). Ten oever aan de Rupel. [Illustration]. Accessed on May 25, 2022, http:// www.emabb.be/old/Nl/ nl_TenOever.htm

fig. 9 - section, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 10 -drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 11 -mapping, drawn by Astrid De Mazière, based on Buggenhout, S. & Piffet, R. (n.d.) Erfgoedtoets. fig. 12 - Dujardin, F. (2014). Reconversie Peeters-Van Mechelen [Photograph]. Lezze. Accessed on May 23, 2022, https://lezze.be/2014/08/01/reconversie-peeters-vanmechelen/ fig. 13 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 14 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 15 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 16 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 17 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 18 - map, drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 19 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 20 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 21 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 22 - picture by Astrid De Mazière

137

fig. 23 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 24 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 25 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 26 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 27 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière, based on the work of DeSilvey, C. (2017). Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Scott, F. (2008). On altering architecture. New York: Routledge.

fig. 28 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 29 - masterplan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 30 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 31 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 32 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 33 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 34 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 35 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 36 - masterplan with scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 37 - masterplan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 38 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 39 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 40 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 41 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 42 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 43 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 44 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 45 - section by Astrid De Mazière fig. 46 - detail by Astrid De Mazière fig. 47 - axonometry by Astrid De Mazière fig. 48 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 49 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière

138

fig. 50 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 51 - drawing by Astrid De Mazière fig. 52 - picture by Astrid De Mazière fig. 53 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 54 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 55 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 56 - section by Astrid De Mazière fig. 57 - illustration by Astrid De Mazière fig. 58 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 59 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 60 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 61 - section by Astrid De Mazière fig. 62 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 63 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 64 - drawing detail by Astrid De Mazière fig. 65 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 66 - illustration by Astrid De Mazière fig. 67 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 68 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 69 - section by Astrid De Mazière fig. 70 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 71 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 72 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 73 - axonometric schemes fig. 74 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 75 - scheme by Astrid De Mazière fig. 76 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 77 - collage by Astrid De Mazière fig. 78 - plan by Astrid De Mazière fig. 79 - masterplan by Astrid De Mazière

139

Introducing the site

Introducing the site