5 minute read

Birmingham's Medical Pioneers

from Aston in Touch 2018

by Aston Alumni

Foxglove X-ray by Chris Thorn (xrayartdesign.co.uk)

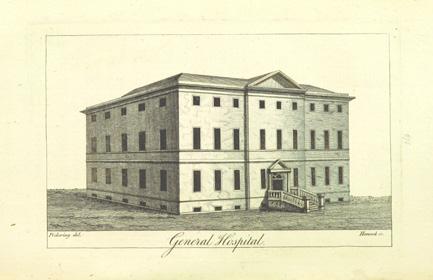

Fifteen minutes from campus, past Snow Hill station and towards Constitution Hill, the road bends to the right into Summer Lane. Today this nondescript street is populated with industrial units, but in the late 18th century, on the spot where West Midlands Passenger Transport Executive now has a Brutalist office block, Birmingham’s first hospital stood. This might not, in itself, seem extraordinary, but Birmingham General Hospital was a long time coming - 34 years, in fact. Once established, however, it fostered some discoveries that would become landmarks of medical history.

Advertisement

Birmingham General started out as an idea by Dr John Ash, who opened a subscription to the hospital in 1765. No doubt inspired by the foundation of the General Infirmary at Stafford, the project attracted initial donations from, among others, the firm of Taylor and Lloyd (later Lloyd’s Bank) and the printer John Baskerville, but after a promising start it ran seriously aground, leaving the Committee embarrassed by delays and debts. In the end it was art, not science, which gave Birmingham its first hospital building. With the launch of the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival in 1768, Birmingham General found itself a source of philanthropic income that would enable the structure on Summer Lane to be completed and opened on September 20th 1799. It was a modest start, however, with just 40 beds (less than half the number envisaged) and only four nurses at four guineas per annum, with another guinea promised “if they behave well”.

William Withering, Copyright Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham

Modest it may have been, but several discoveries emerged from this institution which have shaped medical practice today. Clifford Bailey, Professor of Clinical Science at Aston University, points to “pioneer studies conducted at the hospital that heralded the treatment of heart failure and the medical use of X-rays”.

One of its notable physicians was William Withering, who moved to Birmingham in 1775 to take up a post made vacant by the death of Dr William Small. This year was important for another reason - because it marked the commencement of Withering’s experiments with the leaves of the foxglove (digitalis purpurea). Over ten years later, he outlined his discoveries in what would become his most famous work: An account of the foxglove, and some of its medical uses: with practical remarks on dropsy, and other diseases. In the year 1775, Withering explained, he was asked his opinion concerning a family recipe for the cure of dropsy (an 18th-century term for a generalised swelling of the body). He was told that it had long been kept secret by an old woman in Shropshire, who had sometimes made cures after the more regular practitioners had failed. He was also informed that there were side-effects - violent vomiting and purging - though its diuretic effects had not been recorded. "This medicine was composed of twenty or more different herbs, though it was not very difficult," wrote Withering, an apothecary's son from Wellington in Shropshire, "... to perceive that the active herb could be no other than the foxglove."

Eighteenth-century medicine had not yet made the connection between swollen limbs and heart failure, but in tackling ‘dropsy’, Withering effectively devised the first modern heart medicine. “We now recognise oedema [swelling] as a symptom of heart failure,” explains Professor Bailey. “You can see it in several ways, such as swollen ankles and pitting. We know that, subsequently, it was found that this plant contained a substance called Digitalis. Digitalis was able to enhance the contractile activities of the heart and, as a result, improved circulation. It subsequently gave rise to a derivative called Digoxin, which is still used to this day - not as extensively as other treatments, but nevertheless, Withering’s discovery was a landmark of pharmacognosy. It’s one of the first traditional, herbal treatments that has gone on to be a conventional medicine with nothing more than the active ingredient taken out of the plant. That makes it an absolute pivotal observational study for the treatment of a particular heart disease.”

Withering’s discovery has long since entered folklore. His first biographers, Peck and Wilkinson, speculated that Withering had encountered the patient with dropsy on a trip to Stafford, but the details were later embellished to include the Shropshire woman Old Mother Hutton, to whom Withering supposedly handed golden sovereigns for the “secret of the wayside flower”. Withering - a man not given to fanciful thinking - would have dismissed such fantasies. “His work,” says Professor Bailey, “is a reminder that you should observe, you should then try to deduce from the observation, develop a hypothesis, test it, and then rationalise what you have found - and Withering achieved all of that at a time when people weren’t instructed in that way.” In 1985 Dennis Krikler used the same principles to trace the origins of Old Mother Hutton, finding her to be the invention of a 1920s advertising copywriter at Parke-Davis, a company that sold Digitalis preparations.

“In spite of opinion, prejudice, or error,” Withering wrote, “time will fix the real value upon this discovery, and determine whether I have imposed upon myself and others, or contributed to the benefit of science and mankind”. Today his major contribution to medicine is marked by a blue plaque on his former home, Edgbaston Hall, and a portrait by Carl Frederik von Breda (p.29), a copy of which is currently in storage at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham.

Drawing from William Hutton's An History of Birmingham (1809 edition).

John Hall-Edwards plaque outside Birmingham Children's Hospital

In 1897 Birmingham General relocated to Steelhouse Lane on a site now occupied by Birmingham Children’s Hospital. A few years earlier, in 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Clifford Bailey is Professor of Clinical Science and Head of Diabetes Research at Aston University. Röntgen had made the first radiographic image using a new type of ray which he called the X-ray (‘x’ being the mathematical designation for something unknown). The following year, a Birmingham man called John Hall-Edwards made the first use of X-rays under clinical conditions when he radiographed the hand of an associate, revealing a sterilised needle beneath the surface.

“Hall-Edwards realised that you could use this technique to see how bone fractures had healed or needed to be re-set, and he went about developing medical imaging,” says Professor Bailey. In 1899 Hall-Edwards was made the first surgeon radiographer at the Birmingham General, and was the first person to X-ray the human spine. He served in the Boer War with the Warwickshire Regiment as the first military radiographer, and after the outbreak of World War I was promoted to Major. “In order to improve this X-ray technique he kept X-raying his own hand and arm, and eventually he got severe burns and had to have that arm amputated. But Hall-Edwards managed to put in place a whole new impetus to explore X-ray technology for medicine. I think he deserves much more credit for that.”

Clifford Bailey is Professor of Clinical Science and Head of Diabetes Research at Aston University.