5 minute read

Battling the Fake News of Sex Difference

from Aston in Touch 2018

by Aston Alumni

Battling the Fake News of Sex Difference

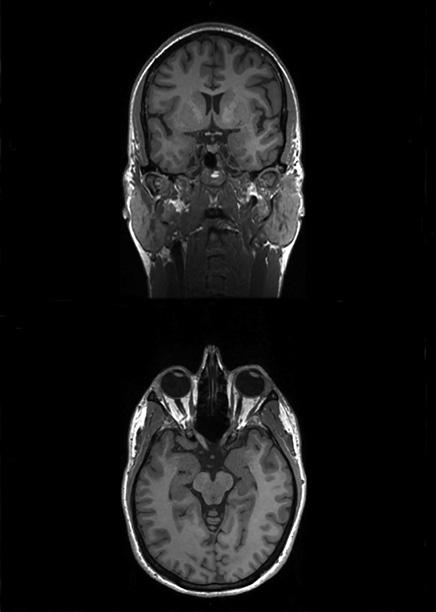

Is there such as thing as a male or female brain? Annette Rubery talks to cognitive neuroscientist Professor Gina Rippon about biological myths and why we must fight them.

Advertisement

“ I ’m a man who discovered the wheel and built the Eiffel Tower out of metal and brawn,” says Will Ferrell as Ron Burgundy: hero of the film Anchorman. “You’re just a woman with a small brain - with a brain the third the size of ours. It’s science.”

Anchorman is, of course, a satire on the sexism of the 1970s TV newsroom, with Ferrell playing the bullish presenter, secure in his male-dominated world. But while those arguments might seem laughable to us now, the idea that men and women’s brains are different has never really gone away. Take Allan and Barbara Pease’s 2001 book Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps, for example. Or recall the Google controversy of 2017 - when a male software engineer wrote a memo suggesting that the low numbers of women in technical fields was down to biological differences. Far from being outmoded, the myth of the male versus female brain is still alive and well in the 21st century.

According to Gina Rippon - Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Neuroimaging at Aston University - those stereotypes are not only inaccurate, they’re disabling. If, for example, girls believe that computer science is a ‘boy thing’ this bias will probably have a negative effect on their performance. Yet as research is revealing, just knowing whether a person is male or female is a poor indicator of any type of behaviour; men and women are fundamentally more similar than they are different.

“I think every brain is different from every other brain,” explains Professor Rippon, when asked if she thinks men’s and women’s brains are the same or different. “So, men’s brains can be different from women’s brains, but not because of some kind of fixed biological template, but because the world treats males and females differently. We now know our brains are plastic throughout our lives and that the experiences we have, and the attitudes we encounter, can change our brains.”

Perceptions of certain subjects as ‘masculine’ might itself have been a factor in Professor Rippon’s journey into neuroscience. A pupil at an all-female convent boarding school, she had hopes of getting into Medicine but her school didn’t offer Physics or Chemistry ‘A’ Level. Biology was available and she managed to combine it with independent tuition in Chemistry, but the only other option available was English Literature. “So I did Biology, Chemistry and English Literature and couldn’t get into Medical School because they were the wrong ‘A’ Levels,” she explains. “I was already interested in the brain, so I applied to do a degree in Psychology instead. At that time, this subject was much more about predicting how people behaved, but the parts of the course I really liked were the ones about the brain, and biology’s role in human behaviour.”

She gained her PhD from Birkbeck College in London, having studied the biological aspects of schizophrenia, then got a job teaching at the newly established Department of Psychology at the University of Warwick. It was here that she first began looking for differences between male and female brains.

“I was doing some research into sex differences and we had some new brain imaging equipment,” she remembers. “I spent ages setting up paradigms and collecting data, never finding any differences. I thought I must be using the wrong task or not using the right kind of analysis, and then eventually I thought: ‘Maybe it’s because there aren’t any differences’. And then I started looking at the data in a different way, in terms of how the individuals were performing on the tasks I was giving them, for example, and then differences in the brain data did emerge. So I carried on looking at individual differences between brains, but no longer in terms of whether they were from males or females, as this didn’t seem to be a fruitful approach.”

It has long been assumed that there is a direct link between biological sex and social gender. In other words, being born male or female would determine the skills an individual had and this would set them on a fixed path in the world. Now scientists are finding that classifying brains or behaviour as male or female is, in most instances, meaningless. Brains are a mosaic of male and female characteristics and the alleged differences between the sexes in, for example, spatial cognition tasks, have been reducing for some time or may even have become non-existent.

The emerging notion that gender is not a binary category (i.e., just a choice between male or female) may be a reaction against the rigid divisions of the past. Facebook’s decision, in 2014, to allow users to select from 71 gender categories to describe themselves might have been an acknowledgement of changing norms. Many are concerned about the sharp rise in the numbers of children being referred to clinics because of gender dysphoria (i.e., a feeling that there is a mismatch between their biological sex and their gender identity). Children, says Professor Rippon, are “gender detectives” from a very early age, and quickly pick up on gender rules. They may feel pressure to conform to very polarised stereotypes, for example via the gendered marketing of toys or clothes. If they feel differently from what is seen as acceptable for them they may conclude that there is something wrong with them and go on to feel that their biology is at fault.

As part of understanding the pressure to conform to stereotyped beliefs about sex differences, Professor Rippon has developed an interest in what she calls the neurotrash industry - the Ron-Burgundy-style misreporting of science to support both lazy assumptions and downright misogyny. She has appeared in a number of TV broadcasts, such as BBC Horizon’s Is Your Brain Male or Female?, and in print media, tackling spurious arguments.

Her battle against what’s been called the ‘fake news of sex difference’ is important because, ultimately, we are all shaped by our environment. “Neurotrash has implications for sustaining stereotypes because it feeds into the world view of what men and women should be like - the Mars and Venus hokum,” she explains. “This includes challenging some of the findings from neuroscience itself. If scientists are basing their research on outdated binary male-female categories then they are failing to acknowledge other important factors in shaping brains. They should always be checking, at the very least, what kind of educational experiences their participants have had. What’s their socioeconomic status? What’s their occupation? These things will change what you find. And if you go into the outside world with your claims that you’ve found male/female differences, they will be picked up by the popular press who will not always represent things accurately. Then you get a kind of vicious circle where it feeds back into what people think, and - as we now know - this changes how their brains work.”

Professor Gina Rippon joined Aston University in 2001 as Deputy Director of the Neurosciences Research Institute and today she is Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Neuroimaging in the Aston Brain Centre. Her new book, The Gendered Brain: The new neuroscience that shatters the myth of the female brain, is published by The Bodley Head and is out in March 2019.