Redefining Biophilic Design:

Regionalism, Sustainability, and Placemaking

Abstract

Biophilic design has developed a superficial connotation. In an attempt to redefine and reimagine the threshold of biophilia, this paper aims to create a more complex framework for analyzing biophilic design. I will attempt to argue that the efficacy of biophilic design is strengthened by its intersection with cultural specificity, grounded in spatial design that incorporates appropriate color, lighting, and material choices, which can be more precisely categorized as regional biophilic design. Additionally, biophilic design cannot exist without encompassing true sustainability, evaluated through factors such as life cycle, transportation, embodied carbon and carbon emissions, and potential for reuse. A critical dimension of sustainability in this context requires consideration of local materials, cultural heritage, indigenous biota, and regional ecosystems.

The term “biophilia” was popularized by German-American psychoanalyst Erich Fromm in the 1960’s. 1 A combination of the Greek root words bíos- meaning “life,” and -philía, one of the four words for love, biophilia is defined more specifically as “a hypothetical human tendency to interact or be closely associated with other forms of life in nature: a desire or tendency to commune with nature.” 2

One of the most common examples of a “biophilic design” project that I have come across in my research has been Bosco Verticale or ”Vertical Forest” by Boeri Studio, built in 2014 in Milan, Italy.

1 “Biophilia Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster.” Accessed September 11, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biophilia. 2 Ibid.

The majority of students studying architecture or interior design likely have an image of this project on their Pinterest board, or, at the very least, have seen this project. After learning more about the qualities of genuine sustainability, I began to question if the project was even sustainable at all.

Architectural educators Daniel A. Barber and Erin Putalik argue in their article in the Harvard Design Magazine, the “superficial” nature of using trees and the “forest city” as a kind of “eco-cloaking device for mass construction.”3 Other critics of the project note the high energy and water usage that comes with maintaining this green façade, and the dangers of trees falling down onto the streetscape. Others argue that the overall benefits of the improved air quality, fostering of biodiversity, carbon sequestration, shading, and experiential qualities of the project outweigh these cons. 4

The project has received a number of accolades and endorsements including recognition from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2023 and the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC) in 2019. 5

In researching the critiques of the Bosco Verticale, it was difficult to find responses to its use of concrete, and its impact on the sustainability of the project. According to the 2018 Chatham House Report by Johanna Lehne and Felix Preston, the cement industry contributes around 8% of global CO2

3 Daniel A. Barber and Erin Putalik, “Forest, Tower, City: Rethinking the Green Machine Aesthetic,” Harvard Design Magazine.

4 Brent Lund, “Sustainability in the Built Environment: Bosco Verticale -- The Skyscraper with 600 Trees,” UWIRE Text, January 20, 2015, Gale Academic OneFile.

5 “It’s Not That Easy Being Green,” World Green Building Council, accessed September 12, 2024; “Green Obsession,” UN SDG Action Awards (blog), July 9, 2023.

Figure 1: Vertical Forest Milan, Boeri Studio, Milan, Italy, 2014. Image by Giovanni Nardi. Courtesy of Stefano Boeri Architetti website.

emissions. 6 The report also stresses the importance of significantly lowering these emissions and the potential for alternative materials in the context of the climate crisis. 7 The impact of the weight of the trees themselves on the amount of steel and concrete used in the structure of the building adds an important point of consideration in the sustainability of the project and brings up the term “greenwashing.” Merriam-Webster defines greenwashing as “the act or practice of making a product, policy, activity, etc. appear to be more environmentally friendly or less environmentally damaging than it really is.” 8 By approaching the consideration of sustainability with more nuance, to recognize the successful qualities of increased biodiversity, air quality, and phenomenological aspects, but to also critique the projects heavy use of concrete and high upkeep demands, is how we can push for more genuine sustainability.

‘The Phenix’ in Montreal, Quebec, by Lemay was completed in 2019 and serves as the firm’s own Montreal office location. The project holds sustainability certifications including LEED Platinum, Zero Carbon Performance, and has received numerous accolades including the 2023 Green GOOD DESIGN Award

6 Johanna Lehne and Felix Preston.“Making Concrete Change Innovation in Low-Carbon Cement and Concrete” (London, England: Energy, Environment and Resources Department at the Chatham House for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2018).

7 Ibid.

8 “Definition of GREENWASHING,” September 4, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/greenwashing.

Figure 2: The Pheix Sustainable Design Lab, Lemay, Montreal, 2019. Image by Adrien Williams. Courtesy of Office Snapshots.

from the Chicago Athenaeum, the 2022 Office division of the Planet Positive Awards from Metropolis, a 2020 Green Building Excellence Award from the Canada Green Building Council, as well as the 2019 Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Awards for Interiors. Besides the implementation of a green wall and interspersed planting throughout the office, the extent to which biophilia is present within the space is underwhelming, and could definitely be pushed further.

Biophilic design has become an increasingly trending subject in architecture and interior design, and is often discussed in tandem with a beneficial psychological impact on inhabitants of space. This connection between biophilic design and its impact on human psychological and physical health has produced a large body of research in the last decade, perhaps also due to the heightened interaction with interiors during the COVID-19 pandemic. All over the world, and for many– for the first time, people were confronted with the realities of living in a space for an extended period of time. Furniture resale platforms like Chairish and AptDeco saw large increases in sales during the pandemic, as more people took greater consideration into their physical surroundings. 9 Interior comfort became a consideration for individual homes and large offices alike, coinciding with this growing interest in biophilic design. Also possibly due to the exponential growth of technology in the last few years, human connection with nature may feel increasingly distant. Not only does the actual use of phones, screens, and other devices often physically separate us from our natural environment, but the increased use of energy, and even consumption of natural resources like aluminum, copper, gold, and cobalt used to manufacture electronic devices directly contributes to the deterioration of our natural world. Thus, biophilic design should aim to tackle both of these antagonistic forces: reconnecting humans with nature, and creating more sustainable practices in design.

In the field of interior design, the term biophilia invokes the idea of bringing nature into the interior. In its current state, biophilic design may be considered as a kind of universal idea, often lacking specific connections beyond a generalized concept of ‘nature.’ Natural materials, allusions to ‘organic’ patterns, natural light, and plants

9 Chavie Lieber, “There Are Two Good Reasons Why Used-Furniture Sales Are through the Roof,” Vox, October 8, 2020.

within the interior are all considered to be biophilic design, however oftentimes the idea of ‘bringing nature into the interior’ can be pushed further. Stephen R. Kellert (1944-2016), of whom the aforementioned award is named, is one of the most prominent figures in the realm of biophilic design. In the first few pages of his book, Nature By Design: the practice of biophilic design, he argues that: “ Biophilic design does not involve simply applying any form of nature to the built environment, but rather doing so in ways that effectively satisfy the inherent human inclination to affiliate with the natural world. “ 10

In addition to Kellert’s several texts on biophilic design, another prominent resource in the field is sustainability consulting agency Terrapin Bright Green’s “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design.” 11 One of the key takewaways from this report is the idea that “ biophilic design must nurture a love of place .” 12 The concept of place and placemaking become key components of how we experience space. How should a “biophilic space” in New York be experienced distinctly from its counterpart in Mexico City? Should their designs only rely on a ‘natural atmosphere’ or can they be pushed further? How else can biophilic design become more critical of its place to create a deeper connection with the natural environment specific to its location, thus creating a richer, more meaningful experience within the context of each locale.

Additionally, if biophilic design is about reconnecting with nature, sustainability should be at the forefront of the design process, specifically in the realm of materiality. Regional biophilia should seek to embody true sustainability in terms of raw material extraction, composition, manufacturing, embodied carbon, transportation, potential for reuse/ recycling, and end-of-life management. We should be able to be critical of projects’ sustainability in the entirety of the design and construction cycle, not just as a singular superficial box that they check or do not

10 Stephen R. Kellert, Nature by Design : The Practice of Biophilic Design, online resource (214 pages) : illustrations (chiefly color) vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), p. 4.

11 William D. Browning, Catherine Ryan, and Joseph Clancy, “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design” (New York, New York: Terrapin Bright Green LLC, 2014).

12 Ibid., p. 13.

check. This includes considering where products are made, with what materials, how they are transported, the process of making them, how long they will last, and how they are reused or disposed of at the end of their life cycle.

(Re)defining Biophilic Design

By conducting a more focused and nuanced study of biophilic design, we may gain a deeper understanding of how we can create more impactful, meaningful and inspiring spaces. I argue that the most successful biophilic design aligns with the following criteria:

i) cultural/regional relevance: the design forms connections to the existing environment including history, religion, biota, geographical features, vernacular architecture, natural/local materials

ii) climatic adaptability: the design works in tandem with the climatic conditions in which it exists

iii) sustainability: the design considers tenets of sustainable design and the full cycle of materials

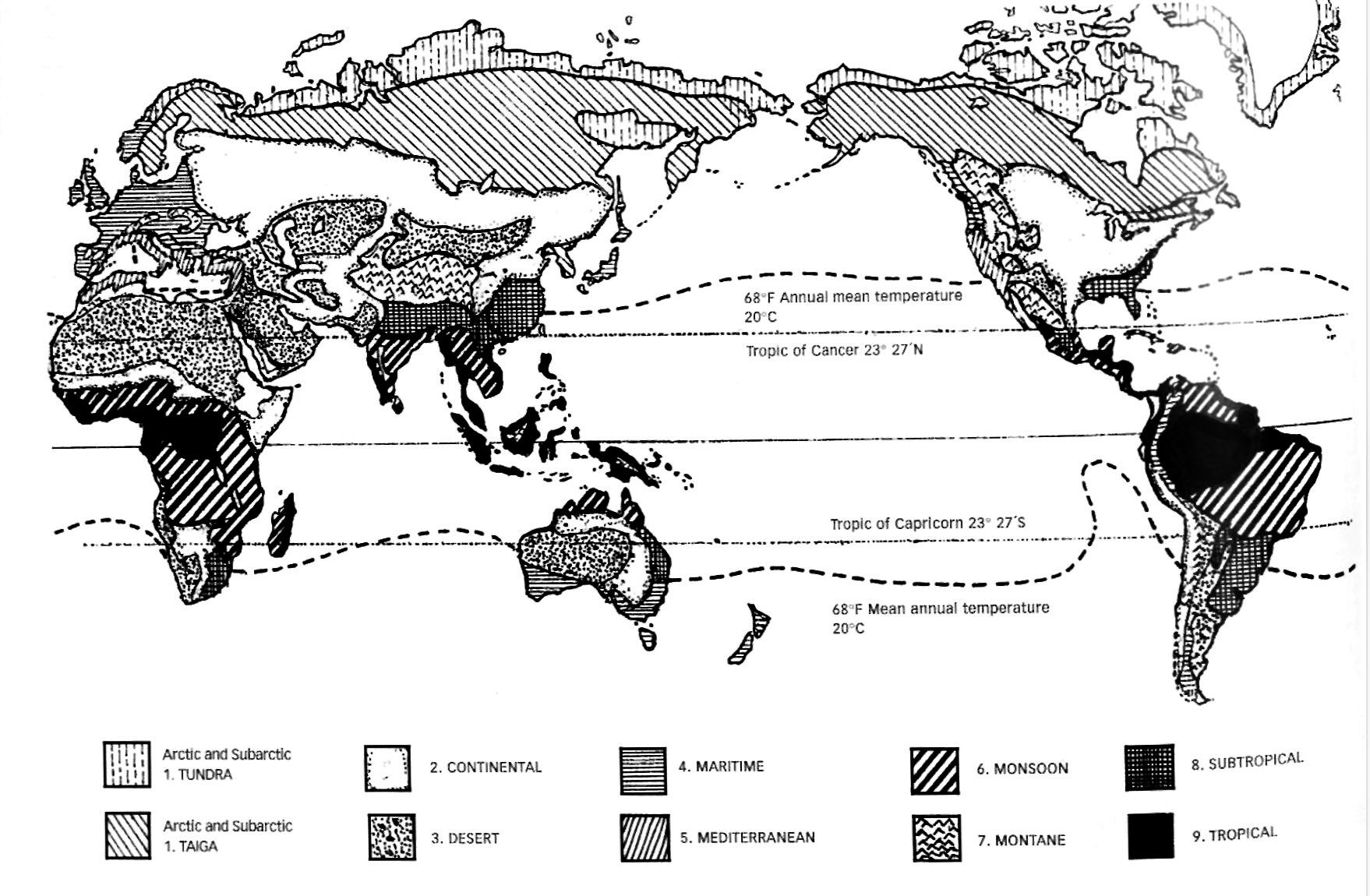

How do different regions manifest biophilic design? The phrase ‘tropical’ spaces, often invokes imageries of lush green landscapes, vibrant colors and an ‘inherent’ connection with nature. This is perhaps due to the increased intensity of extreme heat, and therefore a greater abundance of plant life year-round, creating these constant visual cues that allow us to feel a strong sense of the natural environment. But do other geographic regions also not have similar connections with their natural environments? Why do we more often consider the tropics as having a stronger connection with nature? If the temperate zones’ experience all four seasons they may arguably have a stronger connection with the natural environment. Alternatively, the Arctic zone experiences a similar intensity of the elements, but perhaps less visibly green plant life prevents us from associating them with nature. The potential for place to inform our approach to design is present within all kinds of environments. In an attempt to investigate biophilic design on a global scale, the case studies chosen will look a variety of climates.

Biophilic design should act as a means by which people create a stronger sense of place, and the interior has the capacity to mediate nature and the built environment. Biophilic design, and design as a whole, also have the

potential to act as a means by which culture and heritage are preserved. 13 This potential can be achieved by investigating strategies through a framework of cultural relevance, climatic adaptability, and sustainability. These critera are also often found in vernacular architecture, design specific to a particlar place or region. 14

On Regionalism

Merriam Webster defines regionalism as an “emphasis on regional locale and characteristics in art or literature.” It is also often defined with political undertones, as a kind of self-determinism for a particular place or region. Regionalism’s coupling with the term “critical” was coined by architect and historian Alexander Tzonis (1937-) and Professor Liane Lefaivre in their 1981 essay, “The grid and the pathway.” Critical regionalism, described by the Oxford Reference, is “a strategy for achieving a more humane architecture

13 Frank Jacobus, “Toward the Immaterial Interior,” in The Interior Architecture Theory Reader, by Gregory Marinic, 1 online resource vols. (London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2018).

14 “Definition of VERNACULAR,” December 3, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/vernacular.

Figure 3: “Nine Climatic Zones for vernacular architecture,” Paul Oliver, Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 1997.

in the face of universally held abstractions and international clichés.” 15 Tzonis and Lefaivre make distinctions between different types or phases of regionalism, and their proposition of “critical regionalism,” which serves as a tool to recontextualize the local and singular into contemporary cultural contexts. They also make reference to the work of historian, sociologist, and urban planner Lewis Mumford (1895-1990), who writes about culture, cities, urbanization, technology, and architecture. In his lectures at Alabama College in 1941, Mumford argues that:

“Regionalism is not a matter of using the most available local material, or of copying; some simple form of construction that our ancestors used, for want of anything better, a century or two ago. Regional forms are those which most closely meet the actual conditions of life and which most fully succeed in making a people feel at home in their environment: they do not merely utilize the soil but they reflect the current conditions of culture in the region.” 16

Discussions of regionalism invoke the idea of a romanticization of the past, of nostalgically looking to past vernacular forms to establish local identity. Both Tzonis and Lefaivre and Mumford implore the designer to critically examine and engage with past culture, and while vernacular forms often make use of local material and are in character with their particular climatic conditions, we cannot consider them without also considering the improvements in technology we currently have access to.

Case Study #1: Climatic Adaptability

Mexican architect Frida Escobedo’s ‘Boca de Agua’ project in Cancún illustrates how we can adapt vernacular architecture to create more regional spaces. The construction of raised villas leave 90% of the natural jungle environment intact. 17 Additionally, the project uses FSC-certified Chicozapote wood, a species native to Mexico and Central America. Open slatted facades allow increased airflow throughout the interior, decreasing heat levels

15 “Critical Regionalism,” Oxford Reference, accessed September 26, 2024, https://doi. org/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095648561.

16 Lewis Mumford, The South in Architecture; The Dancy Lectures, Alabama College, 1941 (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1941), p. 30.

17 “Frida Escobedo Completes Treehouse-like Resort on Mexico Coast,” Dezeen, October 23, 2023, https://www.dezeen.com/2023/10/23/taller-frida-escobedo-treehouse-resort-mexican-coast/.

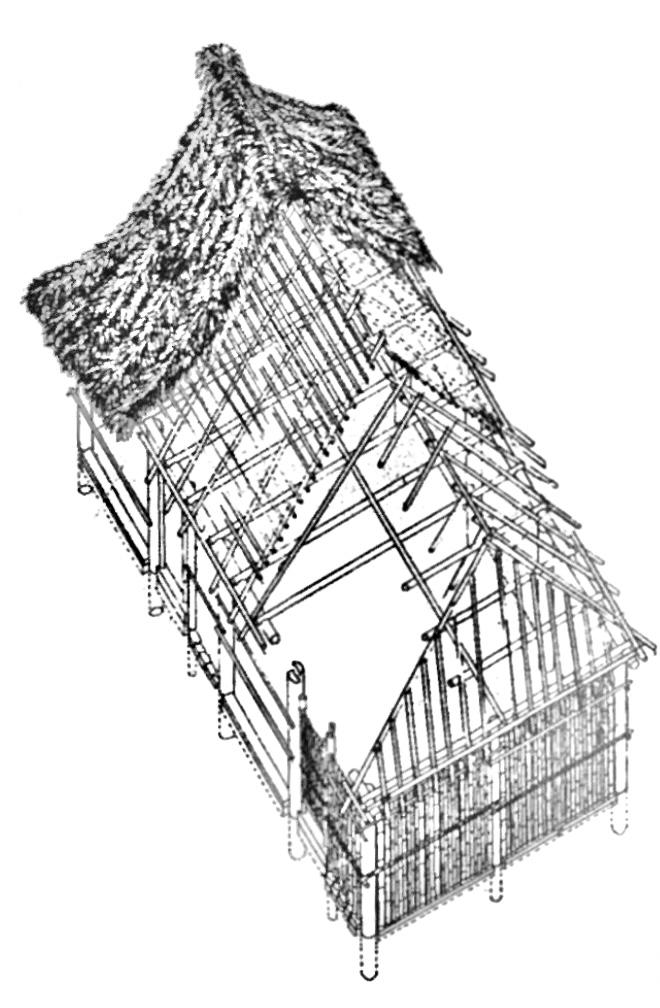

within the tropical climatic zone. In vernacular traditions of Mexican architecture, solid adobe and mudmortar walls, as well as lighter woven-stick and mud were used to create structures. 18 Additionally, zacate, or grass roofs were left unclosed with a hole to promote air circulation. 19 In this project, we can see the way vernacular techniques can inform modern approaches to design to improve climatic comfort within a space. With a simple and minimal material palette, Escobido uses the structure as a frame for the existing natural environment. The building is a medium 18 Paul Oliver, Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 1772. 19 Ibid., p. 1772.

Figure 4: Interior image of Boca de Agua treehouse showing lighting conditions, materiality, and view to exterior. Image by César Béjar. Courtesy of Dezeen, 2023.

Figure 5: A. Peruzzi/Giancarlo Cataldi, “Cut-away axonometric of a Totonac house,” in Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 1997.

through which users can experience the rural landscape. A new understanding of biophilia should expand to also consider material and form: how can materials also inform our approach to experiencing our natural environment and create forms that reconnect us with nature? Even a detail as small scale as an operable window can make a significant difference in feeling connected with the outside world. Sensorial experiences involving sight, sound, smell, touch, and even taste, are crucial aspects of creating connections to spaces, and are therefore key opportunities to consider climate, region, and place.

Climatic adaptability becomes a means through which users can form connections with their environment, not necessarily limited to tropical climatic zones–even arctic zones should perhaps consider how to foster a sense of place. The idea of climatic adaptability should also be at the forefront of design strategies as we witness the increasing impact of climate change throughout the globe. Rising sea levels, extreme temperatures, severe droughts, hurricanes, and other natural disasters, have already begun to affect regions all over the world, and therefore our approach to design needs to not only work towards reducing its environmental impact, but also mitigating these effects. 20

“Climate Change Impacts | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.”

Figure 6: Exterior image of Boca de Agua treehouse showing stilt structure and jungle environment. Image by César Béjar. Courtesy of Dezeen, 2023.

As discussed in ‘Climatic Adaptability,’ the vernacular often serves as a reference for how design can be optimized for a specific region or climate. Embedded in this notion of the vernacular is a specific connection between place and culture. Thai architecture firm Enter Projects Asia’s ‘Spice & Barley’ ‘gastro lounge’ adapts traditional vernacular architecture into the interior. Large scale undulating rattan sculptures act as pseudo-columns, before spilling out onto the ceiling plane. Rattan, a species of climbing palm native to the Asia-Pacific region, has been long used in Thai crafts and architecture. 21 Being both flexible and extremely strong, as well as fast-growing, locallygrown, and lightweight, rattan was widely used in vernacular Thai architecture for walls, furniture, and other domestic objects. Enter Projects Asia has developed their own in-house fabrication facility,

21 “Rattan - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics.”

Figure 7: Figure 7: Interior-exterior view of Spice-Barley restaurant| Enter Projects Asia,” Enter Projects, 2020.

Figure 8: Akha House, Thailand, 1985.

hiring local Thai craftspeople for the construction process, but designing complex geometries within their team using digital tools and technology. 22

Through this project, we can see how local materials can be combined with modern digital technologies to create new forms. Materiality creates a bridge between vernacular tectonics and the interior. As Mumford argues, we cannot simply recreate the vernacular (in the interior or exterior) and call it regionalism. We need to adapt and consider new technologies and current needs. As regional biophilia becomes more specific to interior design, the binary between culture and nature blurs, and we can see how adapting local vernacular technique can create a richer, more compelling space while also being inherently more sustainable. In the first case study we saw how the material and form work to mediate the relationship between the environment and the interior through thermo-sensorial aspects, and here we can see how material and form work to evoke ideas of place.

Case Study 3: Sustainability

We have already seen the interconnection between regional and local materials and sustainability, however now we will take our study of biophilia north. The ‘Arctic Bath,’

22 “Sutainability & In-House Fabrication | Enter Projects Asia,” Enter Projects, accessed November 21, 2024, https://www.enterprojects.net/sustainability.

Figure 9: Aerial perspective of the Arctic Bath on the Lule River, Sweden, 2019.

designed by Bertil Harström, Johan Kauppi, and Ann Kathrin Lundqvist in 2019, floats on the Lule River in a remote area of Sweden. The project consists of 6 river-front floating cabins and 6 larger in land cabins, and a floating circular wellness center with an ice-bath in the river, as well as hot baths, saunas, and a spa. This luxury experience is centered around mindfulness, with activities such as yoga and meditation, and being immersed in the natural world. In the winter, the structures freeze into the river, and in the warmer months, float through a custom-made concrete pontoon system. The design for the central open air structure comes from log jams that occurred due to felled trees, and so the wood used for this nest-looking construction is local felled pine. The palette for the interiors evokes the material palette of Scandinavian interiors, and also comes from local Swedish pine. By not only utilizing the natural resources of the environment, but truly celebrating them in materiality, form, and even program, this project makes sustainability inherent within itself. Not only does the space ask us to consider our relationship to nature in the physical realm, but it also invites a kind of introspection of a deeper connection with the natural world. This heightened awareness of the surroundings asks us to consider sustainability not just as an action that we carry out in our everday lives, but how it can become embedded in our fundamental approach to life.

Figure 10: Interior perspective of floating river cabin, image by Anders Blomqvist and Daniel Holmgren, Design Anthology UK.

As we have seen through these case studies, material becomes an essential part of considering how we can expand our criteria of biophilia to become more sustainable, more responsive, and more culturally relevant. Often when designers think of biophilic design, they imagine spaces with intricate, organic curves, embedded with green plants, perhaps even a tree or two. I argue that biophilic design should broaden its scope to encompass a larger range of designs. Additionally, if “biophilia” literally means a love of nature, then all biophilic design should be truly sustainable, and while both ‘biophilic’ and ‘sustainable’ have fallen under this umbrella of greenwashing, used in order to garner increased attention and/ or profits, they are still distinct. I argue that while sustainability is a key component of biophilic design, they are not interchangeable. Biophilic design necessitates a consideration of place, of a specificity that goes beyond a universal nature.

The term biophilia seems to have a stigma, especially within the pedagogy of design. Many professors I have encountered are not sold on the idea of biophilia, perhaps because of its often half-baked implementations in the interior. And so while we must work towards becoming more critical of both biohpilia and sustainability, I believe there should also be an effort to consider biophilia as, in many ways, inherent to design and sustainability.

Through the vernacular, we are able to see how many of the approaches to technique, form, materiality that we draw from local and regional architecture can help us create richer and more sustainable interiors. Many indigenous modes of domestic architecture have already figured out how to adapt to their regional climate, making use of local material, and adapting structures to exist in harmony with the natural environment. These vernacular architectures also often come to form the language of place, embodying a kind of cultural identity that can be built upon and adapted to suit modern needs.

Utilizing the very aspects of the natural and regional environment that make a place unique, in creating interiors that celebrate culture, identity, and sustainability, are the strengths in the potential of biophilic design, and so our approach should aim to consider how we can think more critically about our much needed connections to nature more impactful, intentional, and sustainable.

Projects & Case Studies

Boeri Studio (Stefano Boeri, Gianandrea Barreca, Giovanni La Varra), Vertical Forest Milan, Milan, Italy, 2014.

Enter Projects Asia, Spice & Barley, Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. Harström, Bertil, Johan Kauppi, Arctic Bath, Harads, Sweden, 2019. Lemay Architecture and Design, The Phenix, Montreal, Quebec, 2019. Taller Frida Escobido, Boca de Agua, Bacalar, Mexico, 2023.

“Akha House.” n.d., Werner Collection: India Art and Architecture. George Washington University, . Accessed December 12, 2024. https://jstor.org/stable/community.38407311

Barber, Daniel A., and Erin Putalik. n.d. “Forest, Tower, City: Rethinking the Green Machine Aesthetic.” Harvard Design Magazine. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www. harvarddesignmagazine.org/articles/forest-tower-city-rethinking-the-green-machine-aesthetic/ Barbiero, Giuseppe. 2024. “Biophilic Design Reframed. The Theoretical Basis for Experimental Research.” Ri-Vista. Research for Landscape Architecture 21 (2): 80–91. https://doi. org/10.36253/rv-15678

Beth McGee and Nam-Kyu Park. 2022. “Colour, Light, and Materiality: Biophilic Interior Design Presence in Research and Practice.” Interiority 5 (1): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.7454/ in.v5i1.189.

“Biophilia Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster.” n.d. Accessed September 11, 2024. https:// www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/biophilia.

“Bosco Verticale.” 2024. In Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bosco_Verticale&oldid=1243251240

Browning, William D., Catherine Ryan, and Joseph Clancy. 2014. “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design.” New York, New York: Terrapin Bright Green LLC.

Browning, William D., and Catherine O. Ryan. 2020. Nature inside : A Biophilic Design Guide. 1 online resource (vii, 280 pages) : color illustrations. vols. London: RIBA Publishing. http:// public.eblib.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=6370332.

“Climate Change Impacts | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.” n.d. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/climate/climate-change-impacts

“Critical Regionalism.” n.d. Oxford Reference. Accessed September 26, 2024. https://doi. org/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095648561.

Debal Deb. 2022. “The Erosion of Biodiversity and Culture.” Ecology, Economy and SocietyThe INSEE Journal 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.37773/ees.v5i1.487.

“Definition of GREENWASHING.” 2024. September 4, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/greenwashing

“Definition of REGIONALISM.” 2024. September 16, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/regionalism

“Definition of VERNACULAR.” 2024. December 3, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/vernacular designboom, sofia lekka angelopoulou I. 2020. “Sweden’s Floating, Circular ‘arctic Bath’ Hotel Opens on the Lule River.” Designboom | Architecture & Design Magazine. January 23, 2020. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/sweden-floating-circular-arctic-bath-hotel-opens-lule-river-01-23-2020/

“Frida Escobedo Completes Treehouse-like Resort on Mexico Coast.” 2023. Dezeen. October 23, 2023. https://www.dezeen.com/2023/10/23/taller-frida-escobedo-treehouse-resort-mexican-coast/

“Gallery of Bosco Verticale / Boeri Studio - 1.” n.d. ArchDaily. Accessed September 11,

2024. https://www.archdaily.com/777498/bosco-verticale-stefano-boeri-architetti/564e7c1ee58ece4d730003a3-bosco-verticale-stefano-boeri-architetti-photo “Green Obsession.” 2023. UN SDG Action Awards (blog). July 9, 2023. https://sdgactionawards.org/green-obsession/

“It’s Not That Easy Being Green.” n.d. World Green Building Council. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://worldgbc.org/article/its-not-that-easy-being-green/

Jacobus, Frank. 2018. “Toward the Immaterial Interior.” In The Interior Architecture Theory Reader, by Gregory Marinic. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. https:// search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1769748

Kellert, Stephen R. 2005. Building for Life : Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection. 1 online resource (x, 250 pages) : illustrations vols. Washington, DC: Island Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10149925

———. 2018. Nature by Design : The Practice of Biophilic Design. 1 online resource (x, 214 pages) : illustrations (chiefly color) vols. New Haven: Yale University Press. https://www. degruyter.com/isbn/9780300235432.

Kellert, Stephen R., Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design : The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

Kellert, Stephen R., and Edward O. Wilson. 2013. The Biophilia Hypothesis. 1 online resource vols. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=164142.

Lieber, Chavie. 2020. “There Are Two Good Reasons Why Used-Furniture Sales Are through the Roof.” Vox. October 8, 2020. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/21496101/furniture-resale-market-west-elm-anthropologie-cb2

Lund, Brent. 2015. “Sustainability in the Built Environment: Bosco Verticale -- The Skyscraper with 600 Trees.” UWIRE Text, January 20, 2015. Gale Academic OneFile. Martin, Rory, and Stephen Choi. 2018. “Biophilic Design.” Environment Design Guide, 1–15. McGee, Beth, and Nam Kyu Park. 2021. “Beyond Plants: Biophilic Design as a Pedagogical Tool.” The International Journal of Design Education 15 (2): 209–28. https://doi. org/10.18848/2325-128X/CGP/v15i02/209-228.

Mumford, Lewis. 1941. The South in Architecture; The Dancy Lectures, Alabama College, 1941. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

“NJF Design Creates Thatched Resort Surrounded by Dunes in Mozambique.” 2021. Dezeen. December 24, 2021. https://www.dezeen.com/2021/12/24/kisawa-sanctuary-hotel-mozambique-njf-design/

Oliver, Paul. 1997. Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Preston, Felix, and Johanna Lehne. 2018. “Making Concrete Change Innovation in Low-Carbon Cement and Concrete.” London, England: Energy, Environment and Resources Department at the Chatham House for the Royal Institute of International Affairs. https://www. chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-06-13-making-concretechange-cement-lehne-preston.pdf

“Rattan - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics.” n.d. Accessed November 21, 2024. https://www. sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/rattan.

“Spice-Barley | Enter Projects Asia.” n.d. Enter Projects. Accessed October 3, 2024. https:// www.enterprojects.net/projects/spice-barley

Stairs, David. 1997. “Biophilia and Technophilia: Examining the Nature/Culture Split in Design Theory.” Design Issues 13 (3): 37–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511939

“Sutainability & In-House Fabrication | Enter Projects Asia.” n.d. Enter Projects. Accessed November 21, 2024. https://www.enterprojects.net/sustainability

“The Vertical Forest: A Concrete Utopia for the World, from Milan - InfraJournal.” n.d. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.infrajournal.com/en/w/the-vertical-forest-a-concreteutopia-for-the-world-from-milan.

Tzonis, Alexander, and Liane Lefaivre. 2018. Times of Creative Destruction: Shaping Buildings and Cities in the Late C20th. 1 online resource : illustrations (black and white) vols. London: Routledge. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781317010067