Exploring Participatory Approaches to Social Architecture in South America

Introduction

'…buildings emerge as brief and transitory points where two separate and distant assemblages overlap: architecture and people. More literally, the notion of the contact zone suitably illustrates the fact that buildings provide physical spaces where people meet and interact permanently.' (Hernandez, 2010:43)

Social architecture is where architecture is used as an agent to prompt and initiate social change. It commodifies the construction process via the critical dimensions of participatory design, expansion of control, and the production and circulation of building materials.

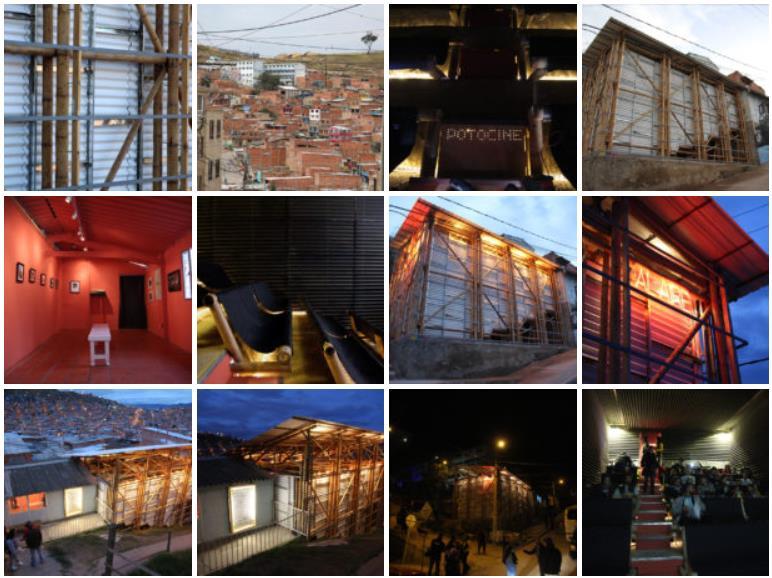

Figure 1: i. El Trebol; ii. La Potocine; iii. House of Rain[Source: Archdaily, no date: online]Hernandez believed in the concept of urban revitalisation. He believed social architecture interventions could address existing differences to 'use architecture as a means to stimulate social interaction' so that they become 'centres of social activity' (Hernandez, 2009:25).

The four key dimensions of social architecture, as defined in the 1970s, are 'autonomy' (acceleration of commercialisation), 'agency' (engage with construction, recognition of selfbuilding), 'participation' (involve community), and 'material' (regional vernacularism).

Most of the definitions of social architecture fit the North. However, in the South, many complexities are ignored when considering the concept of social architecture. Massive political and economic issues like fiscal crises, difficulty securing affordable land, and rapid urbanism had to be overcome to move ahead.

Derived from the critical dimension of 'participation', participatory approaches are defined as including the future inhabitants in the decision-making process for the project. Although architects historically favoured participatory approaches, these are insufficient to make structural or radical changes to alter the underlying urban conditions and justify using the term 'social architecture' (Gribat and Meireis, 2017).

In the context of social architecture, activism is the process of implementing social or political change to reshape communities. The perception of participation, traditionally seen as a symbolic act, is steadily changing, demonstrating the importance and reliability of community involvement to make the dwellers feel included in society.

This essay investigates the role of participation and tries to prove that participation is an agent of expressing the neighbourhood's feelings, giving them a sense of belonging and feeling included and visible in society rather than just being consulted in the decisionmaking process.

To support my argument, I shall analyse a collective called Arquitectura Expandida and take three of their projects to show how participation is used as an agent of expression and how activism strengthens the community. Each case study is analysed on how they relate to dimensions of social architecture, especially participation. Furthermore, the citizens' reaction shows the project's success scale.

This essay will emphasise how the abstract side of participation is as important as the symbolic side. Furthermore, this essay explores the level of activism generated by the collective through a pedagogical approach: the group focuses on the erosion of established patterns of labour, accelerated forms of urban fragmentation, and exclusion of inhabitants.

Conceptual Grounding

Due to a lack of structure and infrastructure, Latin America's population boom and rapid urbanisation in the middle of the 20th century resulted in subpar living circumstances and a low quality of life (Leite et al, 2020). Almost 30% of the infrastructure was built informally, which stigmatises the locality.

Borsdorf's schematic representation of urban developments illustrates the fragmented city, which degraded social conditions, imposed different economic policies like export and free markets and officially recognised auto-construction. Gated communities started developing in Latin America, and the social rationale for the upper class was the differences in lifestyles, self-segregation and the fear of crime. Social fragmentation and rampant sub-urbanisation were the primary social consequences faced by the lower class (Coy and Pholar, 2002).

Urban spaces have evolved from mere physical support for industrial activities to acting as the catalyst for capital accumulation processes in the context of social architecture. Infrastructural set-ups help to secure active citizenship and experience a sense of belonging. Construction became a form of political expression in the quest for access to infrastructure.

Jauregui (2011) focused on urban infrastructure, slum upgrading and comprehensive psychophysical site analysis. His perspective dislocates housing as the critical site of intervention; it is framed around infrastructure as a whole for social transformation. Similarly, Enrique Penlosa (2011), in his book, ‘A City Talks: Learning from Bogotá’s Revitalisation’, mentioned how social housing is not enough to improve the quality of life of people; what people do and where they go in their leisure time is also important.

The past use of participation has been seen as an "intrusion" that has over complicated the social architecture process. Participatory techniques allegedly added "unwanted noise to an already difficult process", thus portraying social interaction as a drudgery rather than a beneficial activity (Forsyth and Jenkins, 2009:xi).

However, contemporary social architecture is starting to comprehend the worth and relevance of various forms of involvement. A pedagogical approach to social architecture aims to help users and experts develop a shared understanding of social and political challenges prevalent in the locality. The users have the chance to holistically mix their lived knowledge with the knowledge of the specialists without assuming that the architects know the "needs of the users better than the users themselves" (Kapp and Baltazar, 2008:14).

This strategy is crucial because the actual experiences, local knowledge and cultural frameworks of the neighbourhoods must be taken into account in order to target the particular needs of the community. This collaborative effort between the users and the experts creates an approach sensitive to the community's needs.

Citizens feel more empowered as a result because their voices are heard and their opinions are acknowledged, which promotes further participation and self-management. Participants learn how to apply their understanding to more enormous social and political challenges through this educational approach, which equips them to continue transforming their communities through self-management even after the organisations have been demobilised.

The significance of fostering activism through participatory techniques in social architecture has gradually come to light. Zibechi emphasises the value of community engagement in teaching and empowering communities. "Education is a crucial political activity for the reform of society," he contends (Zibechi, 2012:23). This is so because a pedagogical approach encourages learning and comprehension, giving citizens the skills and information they need to form an activist identity. Since each member is accountable for participating in a "permanent process of self-education," it is crucial that activism be generated both collectively and individually (Zibechi, 2012:25).

The use of participation within activist and political structures in Latin America is encouraged by this new perspective. Rehabilitation of the 'agency' of construction as a method of being able to alter independently and without depending on the state is the foundation of activist architecture (Boano and Vergara Perucich, 2016).

Arquitectura Expandida is an activist collective based in Bogotá and works with local movements to identify and develop spaces for public participation and self-management in the periphery. The work of Arquitectura Expandida is recognised by the growth of urban debates in contexts of geographical, social, economic, and managerial urban peripheries. Such methodologies facilitate the investigation of alternative community structure models, citizen involvement in public policy, and self-management of shared spaces. Furthermore, these are strategies for exploring how to live together while doing, studying, learning, and building together.

These spaces serve as regular communal gatherings but also serve as a cultural and ecological victory for Bogotá's popular outskirts: The Potocinema (La Potocine) (2016–present) uses cinema to criticise the lack of public cultural venues, while The House of the Rain of Ideas (Casa de La Lluvia de Ideas) (2012–present) serves as a symbol of the quest for environmental rights. On the other hand, The Clover Community House (El Trébol) (2014present) and The House of the Wind (La Casa del Viento) (2011-2017) support urban/street art, literature, and culture as ways for integrating the young and the excluded into society.

The varied nature and contexts highlighted in these social architecture projects serve as an excellent compass to evaluate and analyse the role of participation and self-management as integral agents of strength within the local communities of Bogotá.

Analysis

Participation is structured around infrastructures that increase the excluded social strata's visibility. In this section, I dive deeply into social architecture in Colombia's capital and its history of participation through social architecture. Here, participation occurs in two phasesfirstly, during construction, and secondly, due to the infrastructure developed; stories and knowledge are shared throughout the community.

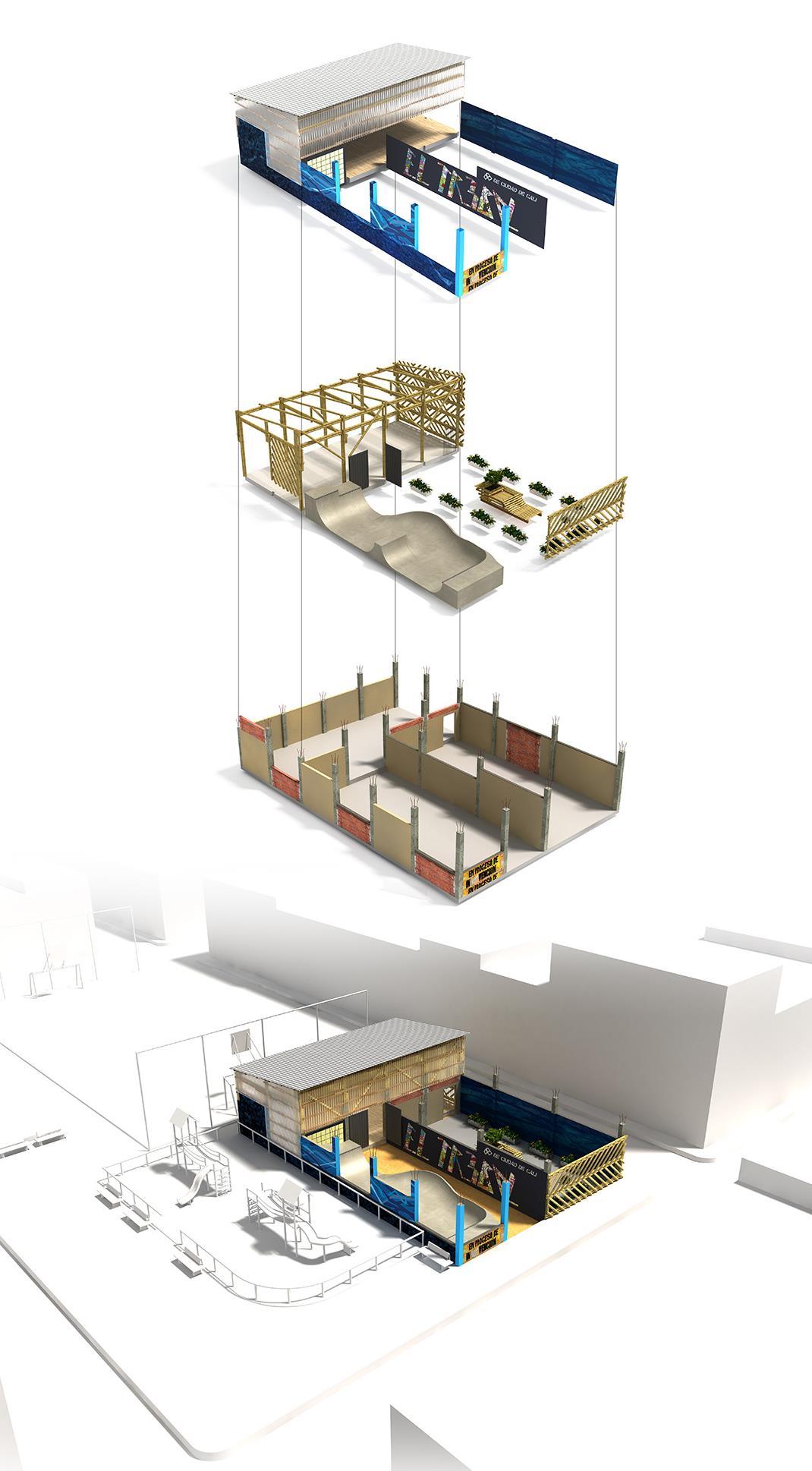

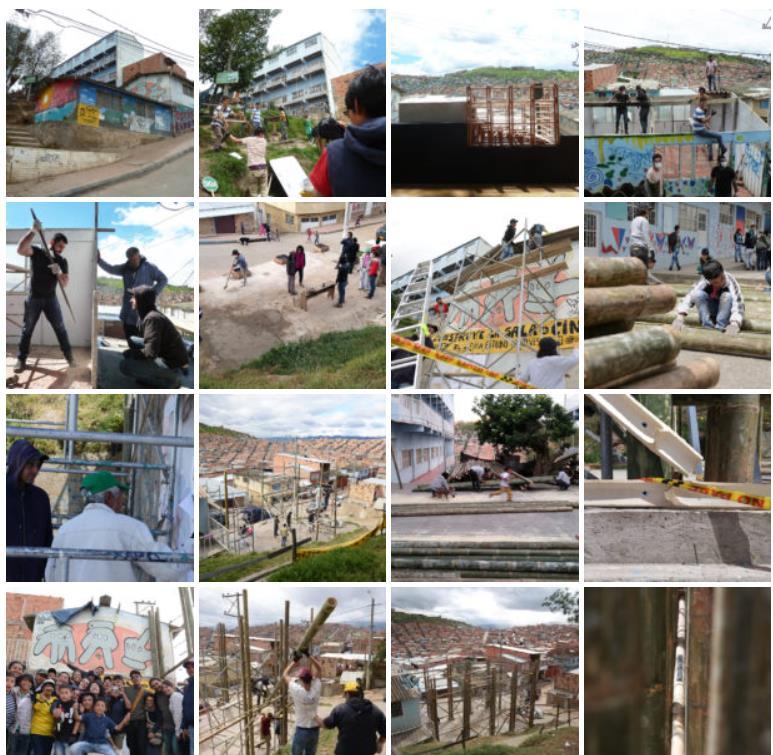

"El Trébol" or "the Clover" was established by the Colectivo Arquitectura Expandida and the Neighborhood Association of the Kennedy neighbourhood in Bogotá to recover a community space that had notable local use historically but had been abandoned for a variety of reasons. A communal space for workshops, conversations, projections, and exhibitions resulted from the initial assemblies and participatory design workshops parallel to the self-construction process.

In the Clover, a skate park, an ornamental garden, a community library, workshops for literature, dance, capoeira, music, bicycles, and the plastic arts coexist with the dynamics of recovering local memory and exchanging territorial pedagogies.

The legal strategies allow intervention without subjecting the process to a labour-intensive and wasteful bureaucratic permit process, and the limited material resources influence the spatial design decisions. Funds were primarily raised through activities that the community has traditionally used to fund neighbourhood self-construction (raffles, bingos, and voluntary contributions).

The existing building that serves as the base has been preserved; however, the roof has been changed. This occurrence allows us to consider how heritage can be recuperated in the unique circumstance where heritage with questionable architectural merit but precious community relevance is recovered.

Guadua creates the enclosure's structure and parts of its various components (local, economical material with a warm character and easy adaptation to self-construction processes). Zinc tile, plastic tile, and alveolar polycarbonate are used in the cladding, which not only enables the construction of a transparent space as an expression of invitation but also provides the opportunity to produce a regulated greenhouse effect, suitable for Bogotá's high temperatures.

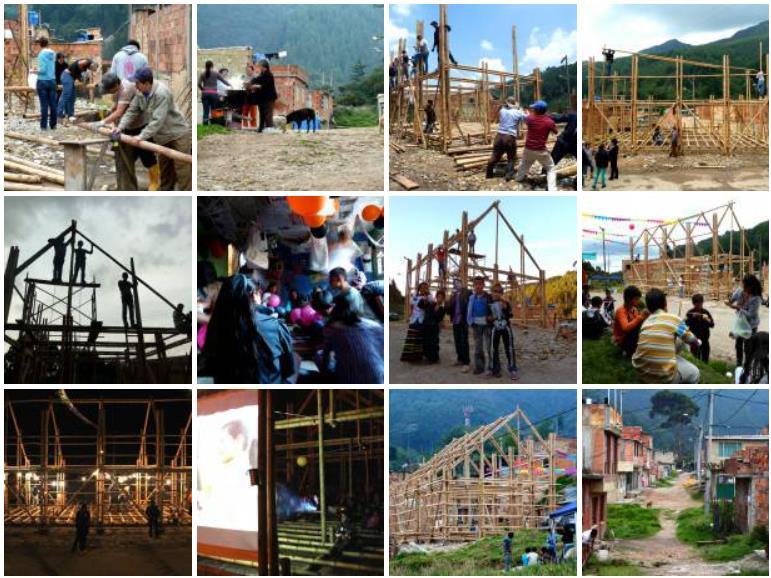

Case Study 1: El Trébol, Bogotá Figure 2: Initial stages of construction of ‘El Trebol’ displaying community involvement in the construction workshop; educational and recreational workshops for citizens. [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 2: Initial stages of construction of ‘El Trebol’ displaying community involvement in the construction workshop; educational and recreational workshops for citizens. [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 3: Exploded axonometry showing the structure of all floors keeping the existing building base intact [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 3: Exploded axonometry showing the structure of all floors keeping the existing building base intact [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

The physical-spatial, cultural, and administrative fragility of public spaces in communities with a history of informal settlements are challenged by this self-organising process. The plot where the Clover is situated appears with several owners in different public databases, which makes the use value of the shared space trump the exchange value. As a result, part of the recovery initiative is linked to neighbourhood opposition to land speculation processes. In essence, the Clover enables us to comprehend architecture as a creative resistance process.

In response to the threats of demolition, the Trébol de todos y todas neighbourhood association was established as a replacement for the Community Action Board. A request had been filed for this organisation to be given the right to utilise the space for cultural purposes. It works closely with the collective Amnesia Selectiva to spearhead the venue's cultural activation. The DADEP (Administrative Department of Public Space) has positively

Figure 4: Usage of the space by the community [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 4: Usage of the space by the community [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

replied to this request and initiated a discourse; most recently, the local mayor's office has given up on the demolition.

The process is represented as one of the three leaves of the Clover: the access area where a collaboratively written timeline materialises. It involves workshops for adults and children (neighbourhood memory workshops and journalism workshops for children, "the guardians of memory"). In another of these Clover leaves, communal garden design and preservation dynamics are being consolidated; vertical gardens, developing a seedbed, and designing outdoor furniture are a few of the techniques explored.

Case Study 2: La Potocine sala de cine, Bogotá

The neighbourhood, named Potosi, is increasingly occupied by displaced individuals due to the country's ongoing conflict, demobilisation operations, and socioeconomic conditions. Guerrilla camps traditionally had an impact on its rural setting. The main socioenvironmental issue today is connected to illegal mining mafias and socio-urban issues, including violence, drug abuse, micro-trafficking, and access to culture, art, health, and education.

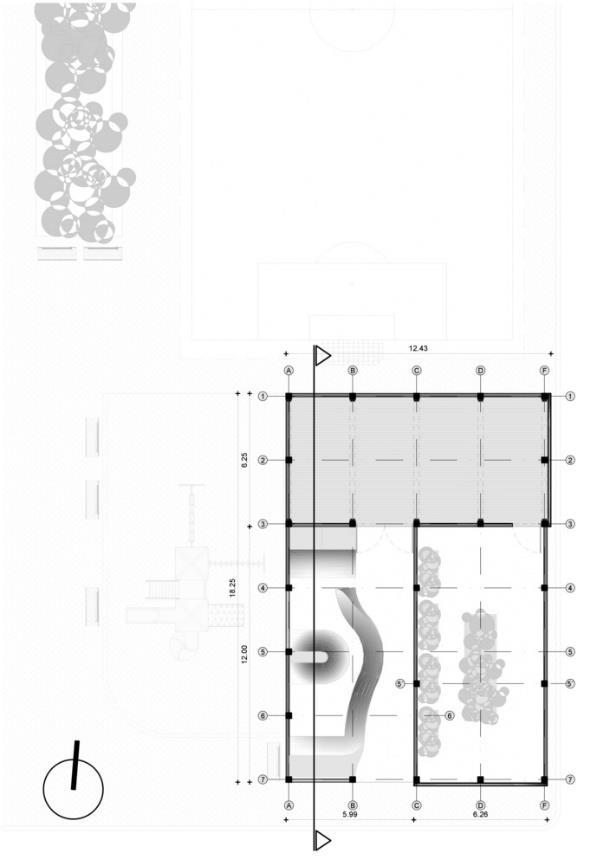

Figure 5: a. masterplan and b. sections and elevations of the project[Source: Archdaily, no date: online]

Figure 5: a. masterplan and b. sections and elevations of the project[Source: Archdaily, no date: online]

The concept of La Potocine emerged out of the need for a theatre and cinema that would serve as logistical support for the institute's activities and a territorial symbolic reference. It would be the first community cinema in Ciudad Bolivar and a physical and symbolic element that would allow us to consider how having the right to be seen and recognised is a requirement of citizenship.

With a focus on the audiovisual process, the self-construction process is used as a pretext to investigate organisational and social dynamics, and information is shared among the participants. Many of the constraints of a process with insufficient institutional support and the social, technical, and organisational tools at their disposal had an impact on the project's design.

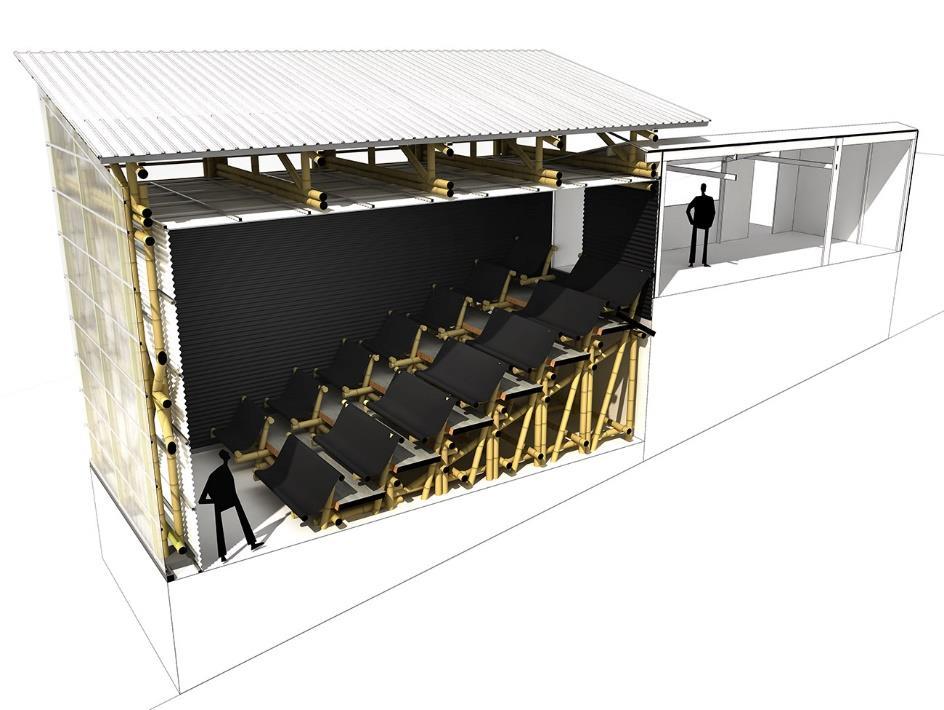

They used a plot ceded by Cerros del Sur, which comprises two concrete platforms on which two prefabricated booths that were part of the institute's foundational building were originally situated. The higher one, which will serve as the access, the workshop, the audiovisual production space, and the sound room, was agreed to be kept, with the majority of the intervention being built in the space where the lower booth was, La Sala Potocine.

Guadua (Colombian bamboo) structure with alveolar polycarbonate outside and interior thermoacoustic tile lining allow the inhabitants to work on the details and leave them visible. This display of the construction system throughout a self-construction process is also a political stance. The armchairs in the movie theatre are built with the extension of the structure of the trusses that define the stands and with textiles that, sewn by various women from the neighbourhood, make up comfortable and versatile "beach chairs".

Figure6: Spatial Qualities of the spaces inside with different lightings. [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 8: Community involvement in construction process using guadua and convenient construction techniques [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 7: isometric section cut through the cinema; view of the chairs and structure [Source: Archdaily, no date: online]

Figure 8: Community involvement in construction process using guadua and convenient construction techniques [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 7: isometric section cut through the cinema; view of the chairs and structure [Source: Archdaily, no date: online]

Case Study 3: Casa de la Lluvia (de Ideas), Bogotá

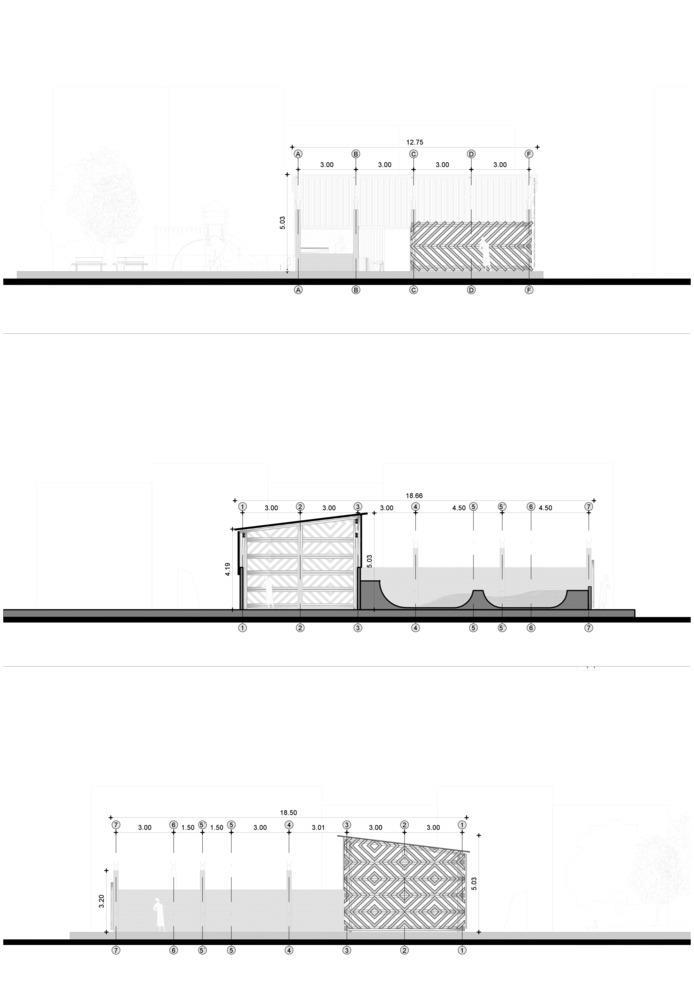

The House of the Rain [of ideas] is a cultural and community place in a Bogota squatter neighbourhood near the hills; the former has been built through physical and social selfconstruction. Its location has few natural resources but abundant human and ecological resources. The potential for self-management in the city can extend beyond housing and essential services to embrace the public and community space, being its inhabitants who take charge of their city's cultural, political, social, and infrastructural management in the first person.

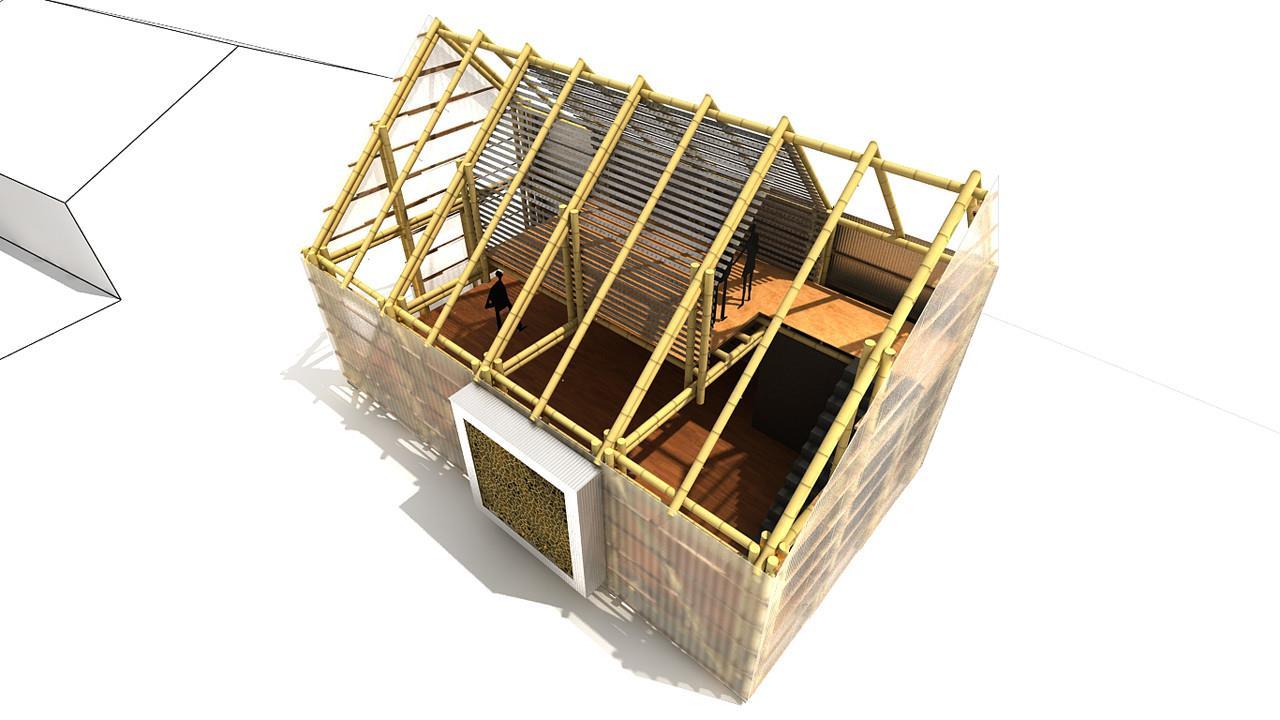

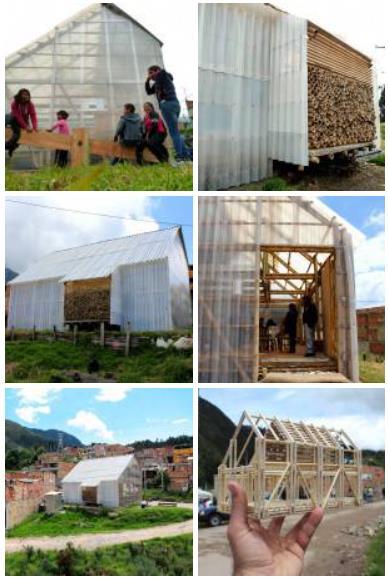

A citizen initiative of cultural management that transcends the physical and spatial limitations of architecture has been developed through participatory design, selfconstruction, and design of cultural activities, which developed over the majority of the Sundays of 8 consecutive months. It was made up of guadua, a locally produced, warm, naturally resistant, and simple-to-work-with material for self-construction. The literal transparency of polycarbonate also has a mental meaning: it is an open environment that always invites you inside and reveals what is going on within. It serves as the territory's lighthouse at night. Because of its materiality, it has a strong symbolic meaning that translates into a right to live in a lovely, representative city and to be seen as an equal citizen.

Figure 9: Structure of the project exposed [Source: Archdaily, no date: online]The technological transfer associated with the guadua (for which self-construction sheets have been developed to solidify this as a pedagogical process) and the cultural strategies associated with the process also impact this project; these strategies try to value the citizen cultures of the territory. For this reason, workshops on the historical memory of the neighbourhood, emotional cartography, and a documentary journalism workshop on the history of the neighbourhood has been developed.

Since 2012, the area has been administered by a local governance system with a strong emphasis on environmental rights and a straightforward yet sophisticated system for managing access keys and cultural programming. The institutional proposal since the neighbourhood's establishment in 2015 included destruction, construction using different materials, and a competitive administration process. The community in assembly rejected this, realising that the institution needed to pay more attention to a system of social and spatial governance that lacks financial security but is supported by six years of operation.

The site assists in locating the Alto Fucha territorial conflict on the city map. It represents a way of thinking about the city in terms of ecological challenges as well as the tenacity of its residents. "Fighting for the permanence of La Casa de la Lluvia [de ideas] is a way of fighting for each of the homes and families at risk of displacement," said neighbourhood resident Mónica Poveda (no date:online).

Figure 10: exterior of the project and scaled miniature model [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 10: exterior of the project and scaled miniature model [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Another significant analysis is the legitimacy vs legality of city construction procedures. A community in this situation is prevented from developing its territory due to the environmental protection law of the eastern hills of Bogotá and the absence of a ruling from the Council of State in this matter. In the 1980s, no law 388 of 1998 enabled POTs nor a 2003 decree that criminalised invasion. As a result, it is imperative to assess the basic urban rights that have evolved into fundamental rights, such as the freedom to assemble and the use of public space as a democratic community centre.

Conclusion

The role of participation in social architecture has evolved and proven to be a crucial and essential tool for stimulating high levels of activism. As important as it is to include locals and the neighbourhood in the design process, the inhabitants should also feel a sense of belonging. Social infrastructures have helped transform poor localities and shape the urban fragments of the city of Bogotá; these include social housing and public infrastructure.

Figure 11: Community involvement in construction process using guadua; basic load-bearing structure of the project shown [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Figure 11: Community involvement in construction process using guadua; basic load-bearing structure of the project shown [Source: Arquitectura Expandida, no date: online]

Participation is frequently disregarded as a right to the city in many Latin American cities, leaving most of the populace feeling abandoned. It will be advantageous for society in many ways, apart from the contextual benefit to social architecture, to transform these disparate strategies for de-hierarchical connections.

After analysing the case studies, the scalability of the projects might be low. However, it has transformed communities, heard their voices, acted as a catalyst, and helped them express their emotions whilst also educating themselves. These examples of social architecture have empowered nearby communities and offered locals the knowledge and political identity they needed to keep shaping their environments.

The projects analysed are small-scale and might have shortcomings like minor legal issues or the permanency of the project. Nevertheless, it has succeeded in showing how participation is used as a means of expression, fulfilling community needs and making the citizens feel included. Therefore, even small-scale projects do have the power to change underlying urban issues and conflicts.

To conclude, the analysis of the particular element of 'participation' in association with 'selfmanagement' and 'activism' in the context of social architecture in South America has provided significant evidence that the inclusion of the local community in not just the decision-making process but also the ground-level thinking process for social infrastructures is a way of fostering a sense of inclusion and belonging and inculcates in the form of empowerment of the local community through these social infrastructures.

References

Arquitectura Expandida (no date) Arquitectura expandida. [Online][Accessed: January 3, 2023] https://arquitecturaexpandida.org/ .

Boano, C., and Perucich, F. V. (2016) Half-happy architecture. Unknown place of publication: Viceversa [Online] [Accessed on 22nd December 2022]

https://www.academia.edu/24301881/Half_happy_architecture

Jenkins, P. and Forsyth, L. (2009) Architecture, participation and Society. London: Taylor and Francis.

Kapp, S. and Baltazar (2020). “Interfaces for production of space”. Unpublished manuscript.

Leguía Mariana (2011) Latin America at the Crossroads. London: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Leite, C. et al. (2020). Social urbanism in Latin America : cases and instruments of planning, land policy and financing the city transformation with social inclusion. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Nina Gribat & Sandra Meireis (2017) A critique of the new ‘social architecture’ debate, City, 21:6, 779-788.

Penalosa, E. (2011) A City Talks. Learning from Bogotas Revitalisation. N/A: John Wiley & Sons,Ltd.

Zibechi Raúl and Ryan, R. (2012) Territories in resistance: A cartography of Latin American social movements. Oakland, CA: AK Press.