Making Home

Stories of Maintenance and Repair in Inner-City Johannesburg

Credits

Editors

Beatrice De Carli, Valentina Riverso

Contributors

Text: Jhono Bennett, Beatrice De Carli, Rowan Mackay, Zoe Panayi, Valentina Riverso

Images: Clare Chappel, María José Gonzales Zevallos, Aanisah Kausar

Photography, Sharing Bertrams Priority Block: Suzette Van der Welt

Production

Copy Editing: Beatrice De Carli

Design: Ottavia Pasta

Publisher Architecture Sans Frontières UK

ISBN 978-1-0685485-2-9

How to Cite

Architecture Sans Frontières UK and 1to1 Agency of Engagement, Making Home: Stories of Maintenance and Repair in Inner-City Johannesburg. Change by Design Johannesburg (London: Architecture Sans Frontières UK, 2025).

Foreword: Putting Residents First

The Context of Inner City Johannesburg

Case Studies

Argyle Court: A Model of Resident-Led Management

Bertrams Priority Block: A Precedent in Resident-Led Upgrading

Fraser House: A Case for Mixed State and Resident-Led Maintenance

Foreword: Putting Residents First

This report is part of a series presenting findings from the Change by Design workshop series, which was held in Johannesburg from 2023 to 2025. Led by Architecture Sans Frontières UK (ASFUK) and 1to1 Agency of Engagement, this initiative champions the right to adequate housing for inner-city residents who frequently face challenges in securing affordable and stable accommodation. Over two years, we have collaborated closely with residents of informally occupied buildings and their support organisations to strengthen grassroots mobilisation and advocacy efforts.

The Change by Design initiative is built on robust partnerships with the Inner City Federation (ICF), the Inner City Resource Centre (ICRC), the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI), and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Further contributions came from several South African and UK universities, including Wits University, the University of Johannesburg, and the University of Cape Town. Through our grassroots partners, we engaged with approximately 150 residents across seven informally occupied buildings over four intensive, one-week workshops. Our goal was to gain a deeper understanding of their living conditions, aspirations, and available options, while also enhancing their advocacy skills and creating useful documentation of the process.

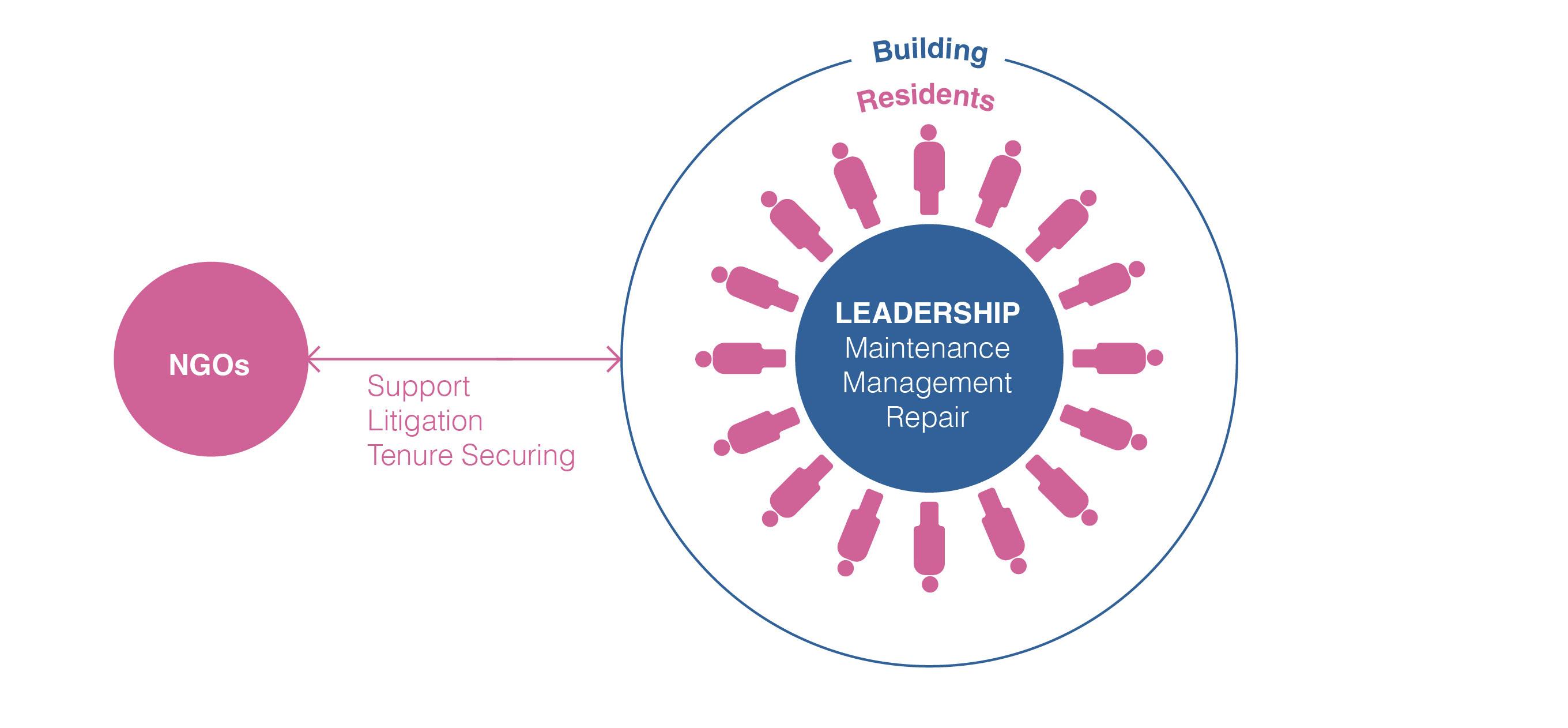

Our experiences have confirmed that innercity buildings—whether they are informally occupied, temporarily established, or abandoned—are fundamental to providing adequate housing for lower-income residents and enhancing the overall quality of life and safety in Johannesburg. Crucially, our findings highlight that under the right conditions, residents can become active partners, not just passive recipients, in securing dignified living conditions in the inner city. Many have successfully managed their homes for decades, implementing effective systems for maintenance, security, rent collection, and cleaning. Despite significant challenges, they invest considerable effort in these properties, often with support from inner-city social movements, allied non-governmental organisations, and universities.

Under the right conditions, residents can become active partners in securing dignified living conditions in the inner city, rather than just being passive recipients.

There is an urgent need for local government to recognise and support these self-managed communities while addressing the systemic barriers they face.

However, systemic barriers—such as unstable city governance, an uncertain policy environment, a lack of tenure security, and limited financial access— hinder residents and their organisations from effectively addressing long-term infrastructural and social problems. These challenges contribute to the decline of the inner city and leave many without safe and adequate housing. For genuine transformation to occur, our research highlights an urgent need for local government to formally recognise and actively support these self-managed communities, while also addressing the systemic barriers they face. By implementing policies that provide tenure security, financial support, and capacity development— similar to successful approaches in informal settlements—local authorities and a supportive private sector can empower residents to improve their homes and actively participate in managing this vital part of the city. Achieving lasting change requires sustained commitment and cross-sector collaboration, with centering the voices and felt experiences of residents and their allies as an essential foundational step.

This publication is an initial step in articulating and substantiating this vision. The workshop series used ASF-UK’s Change by Design methodology, which has four stages: diagnosing, dreaming, developing, and defining. This report specifically documents the diagnostic phase of our work. It details the living conditions in the seven buildings we visited and argues for the recognition of their residents. We conducted in-depth studies of Argyle Court, Bertrams Priority Block, and Fraser House, along with shorter visits to other sites. This report captures this variation by presenting key facts, exploring the processes that led to the current situations, highlighting living conditions, and illustrating existing self-management mechanisms. The other two reports in this series outline a range of principles and specific opportunities for advancing the right to adequate housing in inner-city Johannesburg.

The Context of Inner-City Housing in Johannesburg

Johannesburg’s inner city is a space of contradictions. Once a symbol of apartheidera economic power and white affluence, it has transformed into a contested landscape shaped by disinvestment, neglect, migration, and the everyday resilience of its residents. While certain areas, particularly former banking districts and established retail corridors, have seen pockets of economic revival, much of the city centre now operates under significantly altered conditions, primarily serving a less affluent population. This transformation reflects broader socio-economic shifts and highlights the complexities of urban living in a postapartheid context.

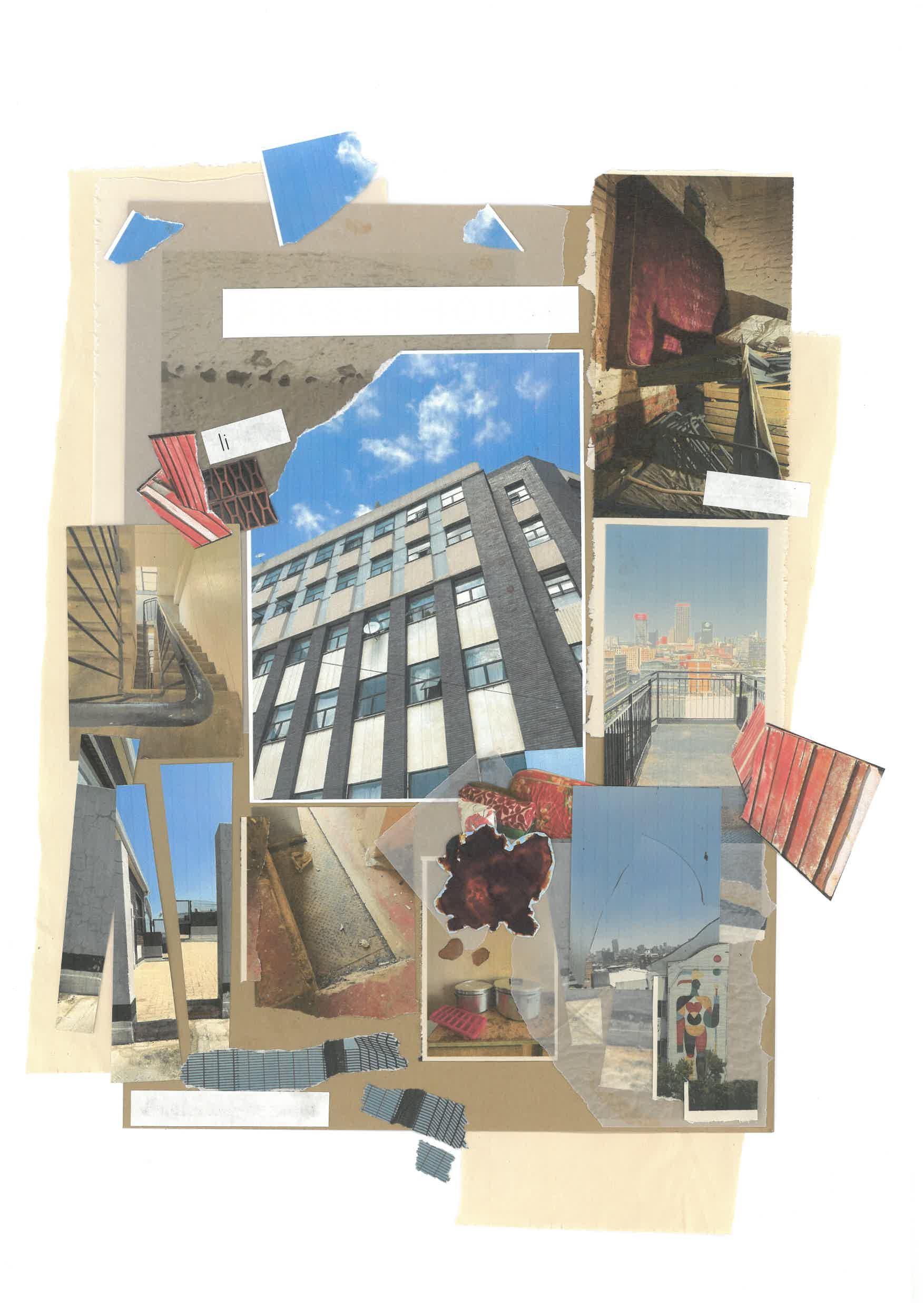

Today, the inner city is characterised by diverse communities residing in various forms of accommodation, including government-subsidised housing, private rentals, and professionally managed properties. A significant portion of the population lives in what are referred to as ‘informally occupied buildings.’ This terminology, embraced by both activists and experts, acknowledges the complex legal circumstances surrounding these structures while avoiding the pejorative implications often associated with terms like ‘bad buildings’ and ‘dark buildings,’ which are prevalent in mainstream media and public discourse. Such language risks perpetuating negative stereotypes and overlook the realities of people who live in these spaces.

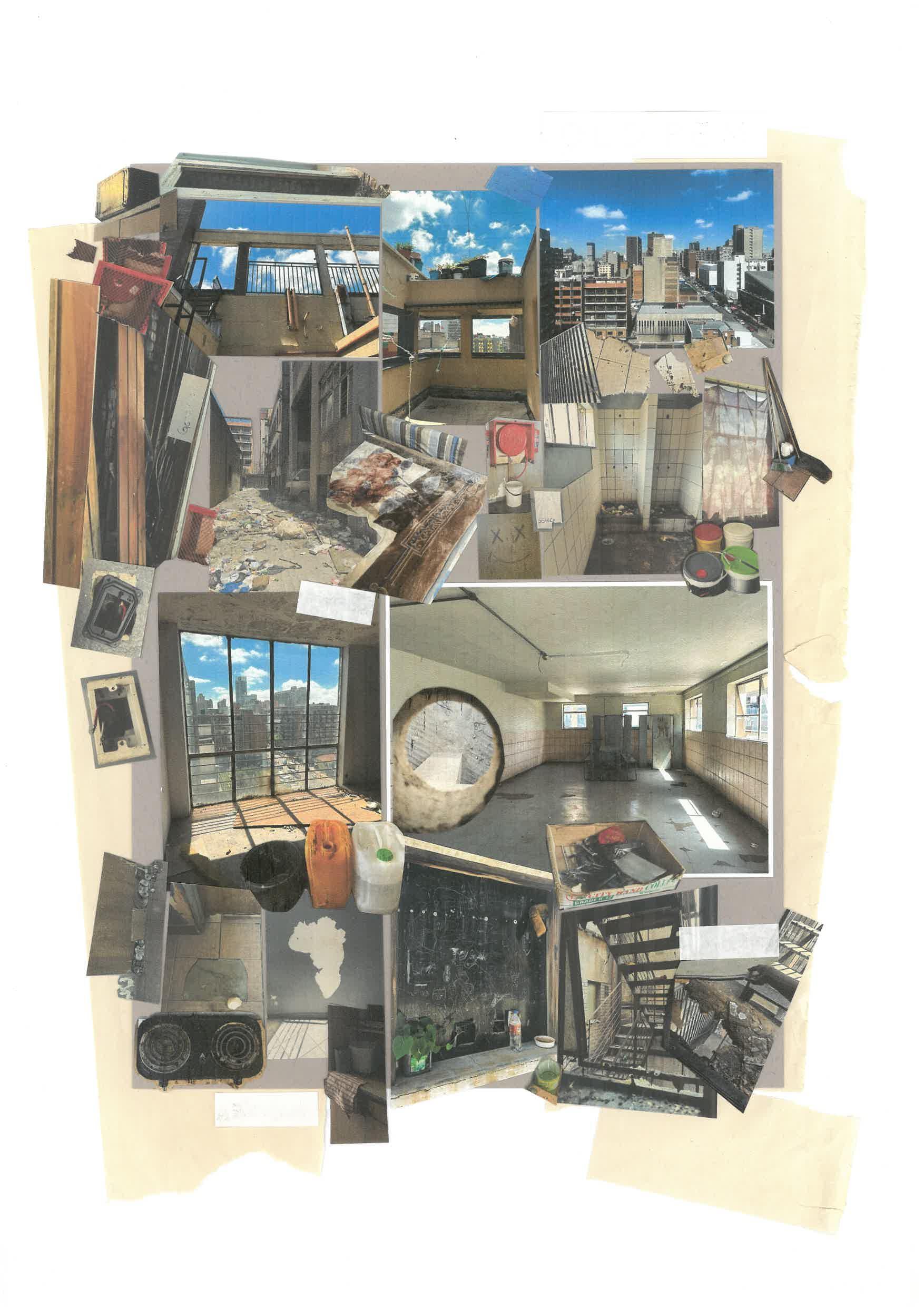

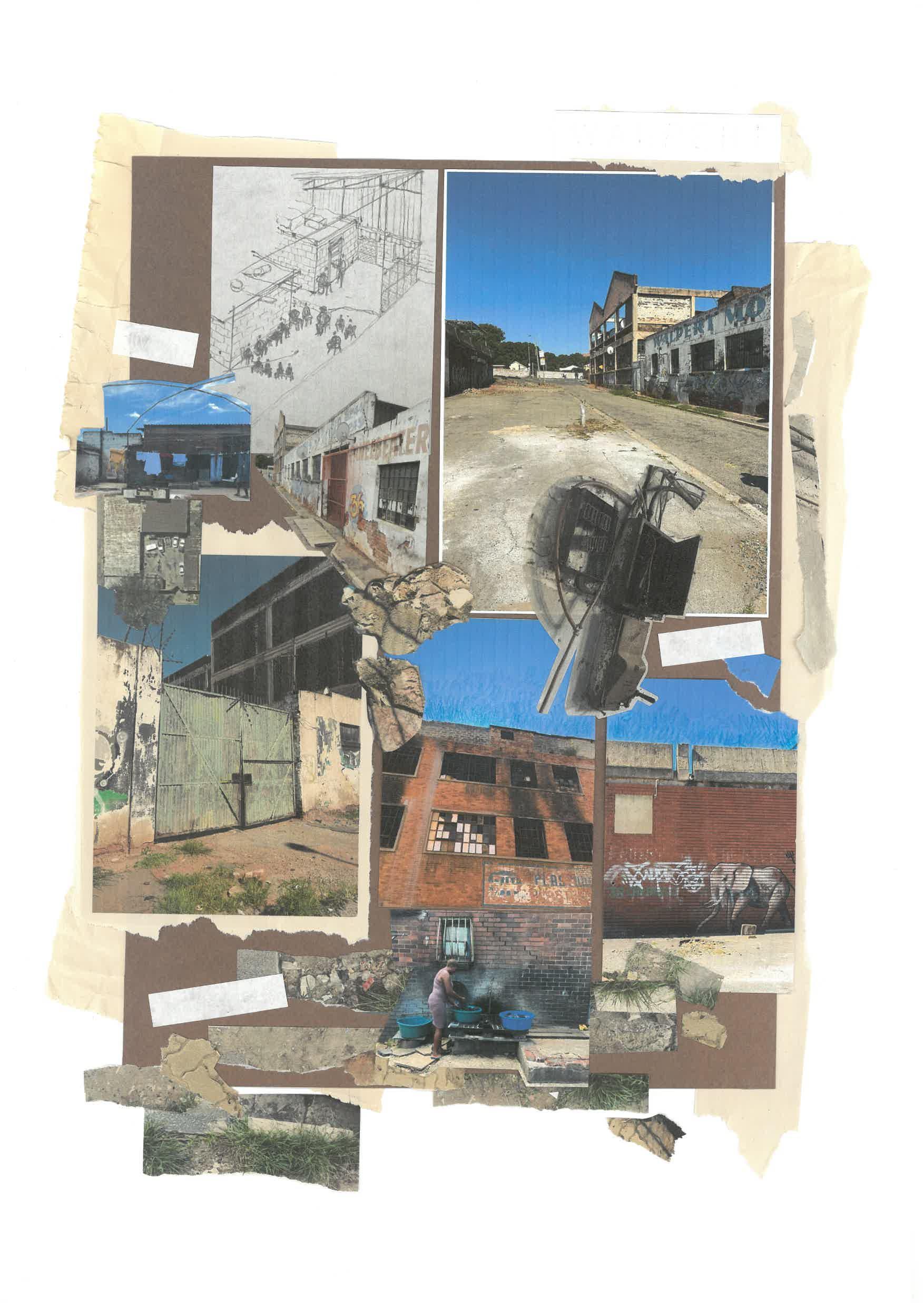

Informally occupied buildings may include former office blocks, abandoned factories, flats, or repurposed warehouses. Typically, these structures suffer from inadequate maintenance and ambiguous legal status. Despite their precariousness, these buildings provide shelter to many individuals facing multiple hardships, who remain engaged in caring for these spaces. This active engagement demonstrates the resilience of communities that, despite systemic challenges, find ways to maintain their living environments. We believe that these buildings and their communities present significant opportunities for innovative and inclusive urban regeneration, highlighting the potential within areas affected by systemic neglect and grassroots forms of care.

The reality of low-income housing in Johannesburg’s inner city reflects the complexities of post-apartheid urban inequality. Each informally occupied building has unique circumstances. Legal statuses vary widely; some buildings are embroiled in ownership disputes, others are caught in prolonged court battles, and many are either municipally owned or in legal limbo due to unresolved insolvency. Finally, some buildings have been ‘hijacked,’ taken over by individuals or groups without the consent of the rightful owners, sometimes leading to the exploitation of residents. Governance structures also differ; while some buildings are managed by informal

Terms like ‘bad buildings’ and ‘dark buildings’ are problematic because they perpetuate negative stereotypes and ignore the realities of the people who live in these spaces.

Each informally occupied building has unique circumstances.

Despite many constraints, residents of informally occupied buildings actively engage in maintenance, repair, and community-building.

leadership groups or community-based committees, others operate under more formal tenant associations. Conditions and living arrangements vary significantly, from crumbling apartment blocks with intermittent water and power supply to subdivided spaces with makeshift electrical wiring and inadequate waste removal systems.

This diversity underscores a broader issue: spatial inequality in Johannesburg and wider South Africa is not uniform and cannot be addressed through blanket urban policy solutions. It must be understood in its full contextual richness. Johannesburg’s spatial contradictions are not relics of the past; they are actively reproduced by contemporary political, economic, and urban governance systems. The legacy of apartheid-era planning, combined with globalised real estate capital, weak urban governance, and rising xenophobia, has created a situation where inner-city housing precarity is both a symptom and a cause of broader systemic dysfunctions.

Despite these constraints, many residents of informally occupied buildings are not passive victims; they actively engage in maintenance, repair, and communitybuilding. From managing plumbing and fixing roofs to caring for the elderly and negotiating with city officials, grassroots care practices are vital to sustaining the inner city. These informal support systems, established by residents and their allied organisations, often bridge the gaps left by inadequate state infrastructure and ineffective housing and social welfare policies. Similar to residents of informal settlements who self-provision drainage and sanitation, occupants of inner-city buildings devise solutions to ensure adequate housing without formal assistance. Supported by a robust network of grassroots organising, their efforts challenge the dominant narrative that portrays informally occupied buildings as dangerous or ungovernable. Instead, they highlight these spaces as essential sites of resilience and resourcefulness, emphasising the urgent need for recognition and support in urban policy and practice.

Recognising these residents and their organisations as legitimate co-producers of the city is not just a matter of justice; it is a strategic imperative. Initiatives like the Bertrams Priority Block project, where 1to1 Agency of Engagement and the InnerCity Resource Centre (ICRC) partnered with residents for repairs using reused materials and co-designed interventions, demonstrate the strong potential of involving people in shaping their own spaces. This approach builds on the idea of upgrading communities in their current locations, as seen in South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), but adapts it for inner city buildings. Instead of tearing down and displacing people for ‘renewal,’ these projects demonstrate how dignified city living can be achieved over time through collaboration and minimal resource expenditure.

However, policy implementation faces significant challenges. Stigma, risk-averse governance, and legal ambiguity complicate the state’s engagement with upgrading these buildings. This often leads to adversarial relationships and inadequate government support for those facing economic and social hardships. Many officials view these buildings as ungovernable, dangerous, and beyond repair—a perception reinforced by high-profile disasters like the 2023 Marshalltown fire. These tragic events expose the consequences of inaction and policy neglect, serving as urgent calls to action. To protect lives, the focus must shift from eviction and securitisation to dialogue, sustained support, in-situ improvements, and the building of institutional trust. This perspective is supported by extensive research and the experiences of grassroots organisations, NGOs, and academics in Johannesburg and beyond, as summarised in a well-referenced 2023 article in the research-based news outlet The Conversation

This approach builds on the idea of upgrading communities in their current locations, as seen in South Africa’s Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), but adapts it for inner city buildings.

The story of Johannesburg’s inner city is not solely one of crisis; it is also one of opportunity. Its informally occupied buildings are not problems to be eradicated; they are seeds of the city’s housing future. With their strategic locations, high density, and embedded social networks, they offer a unique chance to reimagine housing policy beyond the formal/informal divide. This requires a shift in perception and practice— one that views residents as partners in repair, not as subjects of removal. By doing so, we move closer to an urban future grounded not in fear, displacement, or extraction, but in justice, solidarity, and shared stewardship.

Case Studies

Argyle Court

A Model of Resident-Led Management

Building

Location

Building typology

Number of floors

Structural material

Partitions

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Braamfontein

High-rise multistorey building

7, plus basement and rooftop

Masonry walls and concrete slabs

Brick walls; timber and fabric partitions in some units

Individual sectional title: state subsidised ‘pay to own’ scheme

1990s

Inner City Federation

Resident-led building management structure

Single room units: 15–20 sqm, with shared toilets. Bachelor units: Approximately 30 sqm, including a bathroom. One-bedroom units: Approximately 50 sqm, including a bathroom.

Tap per unit

Toilet either per unit or per cluster of units

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

Connected with an account with the City of Johannesburg

Shared washing lines

Overview

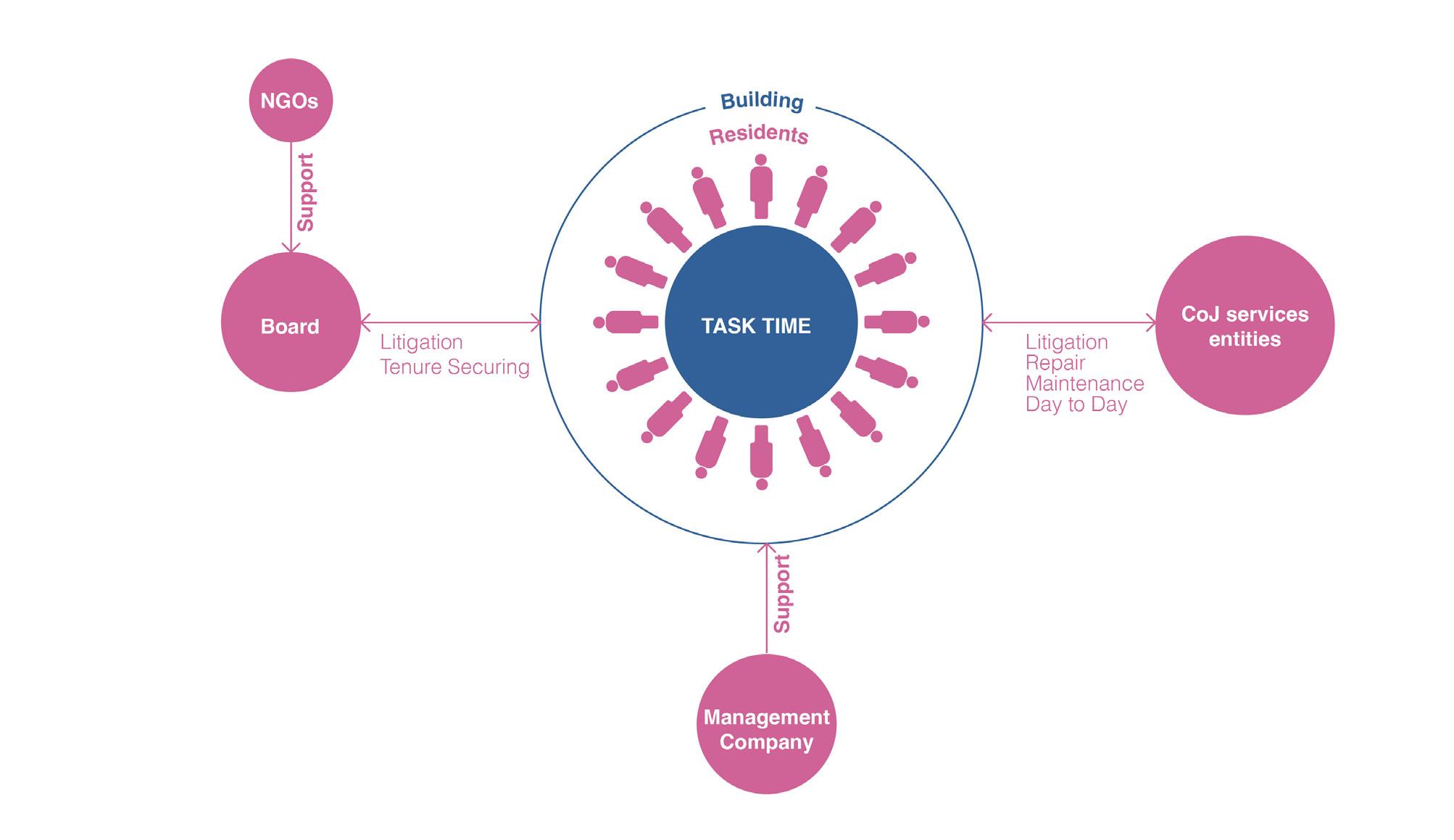

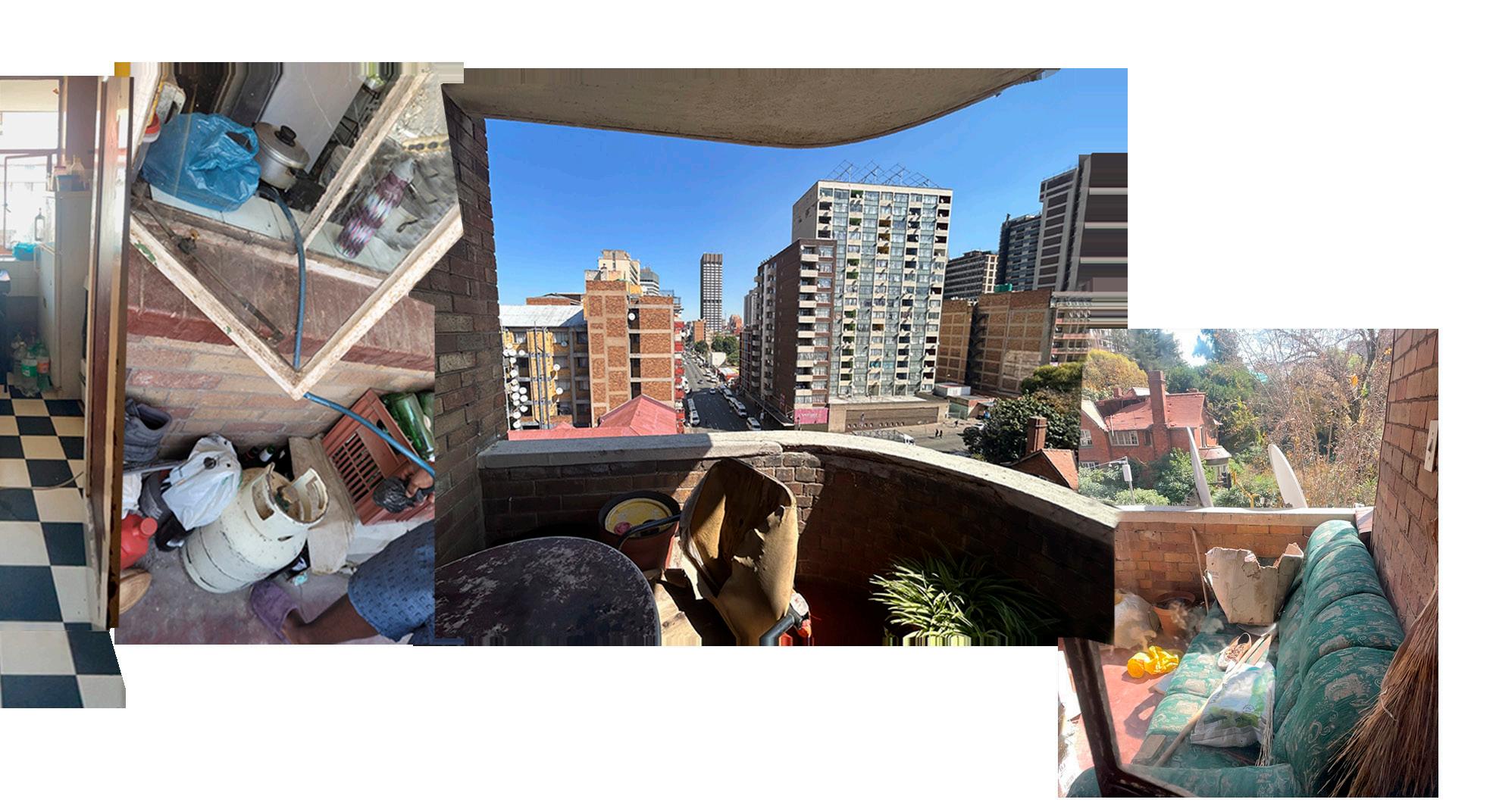

Argyle Court is a seven-storey residential building that stands as a prime example of resident-led management in Johannesburg’s inner city. Originally built under a statesubsidised ‘pay-to-own’ scheme, it now operates under a ‘sectional title’ model, with many residents diligently paying rates and levies to the municipality. While technically part of the formal housing sector, Argyle Court also incorporates informal dynamics, such as partitioned dwelling units of approximately 20 square metres and shared amenities like rooftop washing lines. The resident-led management committee, known as the Task Team, efficiently oversees essential services, including city-connected electricity and individual taps and toilets for each unit.

Despite its complex history, Argyle Court serves as a compelling case study in collective organisation, self-governance, and the potential for incremental upgrading within a legal ownership structure. With 72 households—90% of whom are South African—and strong ties to the Inner City Federation (ICF), the building offers valuable insights into how formalisation and grassroots governance can effectively coexist. The ongoing efforts to secure full tenure through the sectional title process highlight the potential for community-driven upgrading models to thrive, even in historically neglected buildings, provided legal and institutional frameworks are successfully navigated.

Governance

Residents at Argyle Court have been self-managing the building since the mid-1980s, establishing a well-functioning Resident Committee and Task Team to oversee day-to-day operations, including maintenance, security, rent collection, and cleaning. While these daily tasks are managed effectively, the current lack of formal ownership prevents residents from accruing savings or borrowing funds to address long-term structural and cyclical maintenance issues.

Over the years, there have been several attempts to formalise the Committee’s status and establish collective ownership. Notably, the building was part of the Seven Buildings Project in the late 1990s, and more recent efforts have aimed to complete its sectional title. However, challenges to these initiatives reflect a broader political context in Johannesburg. Despite existing policies, legal mechanisms, and resources designed to empower inner-city residents, continuous failures have often resulted from political instability, obstruction and lack of capacity.

Argyle Court has consistently received support from the Inner City Federation (ICF), the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI), and other civil society groups. This external backing has significantly strengthened governance practices and legitimised the Committee’s position with external stakeholders, including service providers (such as power and water utilities) and potential funders.

As a robust example of resident-led housing management, Argyle Court is a legitimate candidate for community ownership. The incorporation of the building as a housing cooperative was previously proposed under the original Seven Buildings Project. Achieving this goal with the City of Johannesburg and relevant authorities would require minimal steps and could be greatly facilitated by the existing network of involved civil society organisations.

Living in Argyle Court

Lethabo

Lethabo is a 28-year-old man who lives on the second floor of Argyle Court. He grew up in this building and now resides there with his brothers, two younger sisters, and their father, who visits occasionally. Lethabo lives in a two-bedroom apartment of approximately 46 square metres. The apartment includes a kitchen, bathroom, and sitting area, with two ‘bedrooms’ separated from the sitting area by a curtain. Residents have also created a lounge space with a sofa for seating and relaxation. The kitchen doubles as a study area for Lethabo’s sister. Lethabo works as a petrol attendant and is well-known for assisting his neighbours at Argyle Court with practical tasks.

Sibusiso

Sibusiso is a 40-year-old man who lives on the sixth floor of Argyle Court. He moved to Argyle Court in 2003. Sibusiso owns his bachelor’s unit and shares it with two other people who contribute to the rent. The space is divided into three ‘bedrooms’ using DIY partitioning made from curtains and suspended bed sheets. The balcony has been adapted to serve as a place to hang clothes and for additional storage. The room is filled with plants, adding character and liveliness to the space. Sibusiso is part of Argyle Court’s Task Team and works part-time as a security guard.

Amahle

Amahle is a 78-year-old woman who lives on the third floor of Argyle Court. She moved into the building in 1988 and shares a two-bedroom apartment with her nephew and two grandchildren. The apartment includes a kitchen, bathroom, two bedrooms, and a balcony. Amahle’s room is used for both sleeping and storage; her belongings are stacked in suitcases, and a TV stand separates the sleeping area. She also has a sofa for visitors. Amahle used to make a living selling vegetables and is now responsible for cooking in the household, making the kitchen her favourite space. Amahle doesn’t use the balcony due to a fear of rats. Due to her age, mobility is a challenge, and she struggles with the stairs; she hopes to move to a ground-floor unit at Argyle Court.

Sharing Argyle Court

Argyle Court is an example of informal yet highly effective building governance, showcasing the potential of empowering residents to self-manage their homes. The building includes a variety of shared spaces, all collaboratively managed by its occupants. For instance, the rooftop and two ground-floor courtyards are used for essential activities such as clothes drying and waste management.

Additionally, the underground car park includes a meeting room that serves as a central hub for the resident-led Task Team and Committee, facilitating the organisation of communal life within the building. Communal toilets and showers on the lower floors further illustrate this self-organising capacity, as they are jointly maintained and cleaned by the residents.

Beyond these shared physical spaces, residents directly oversee a range of essential building services, including security, cleaning of communal areas, maintenance of fire exits, general repairs, and refuse collection. They also manage financial aspects, such as rent collection and arrears, while maintaining records of allocations and occupancy.

This robust, resident-driven framework offers valuable insights into the potential of grassroots management and resourcefulness within informally occupied buildings. It highlights the effectiveness of community-led initiatives in creating adequate living spaces for everyone.

Bertrams Priority Block

A Precedent in Resident-Led Upgrading

Building

Location

Building typology

Number of floors

Structural material

Partitions

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Bertrams

Multiple low-rise, multistorey walk-up buildings

3

Masonry walls and concrete slabs

Brick walls; timber and fabric partitions in some units

Private ownership (absentee owner); informal rental system

2000

Inner City Resource Centre

Resident-led building management structure

15

Not available

Not available

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

Tap per building or cluster of buildings

Toilet block per floor

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

Izinyoka (informal connection)

Vegetable garden and roof space

Overview

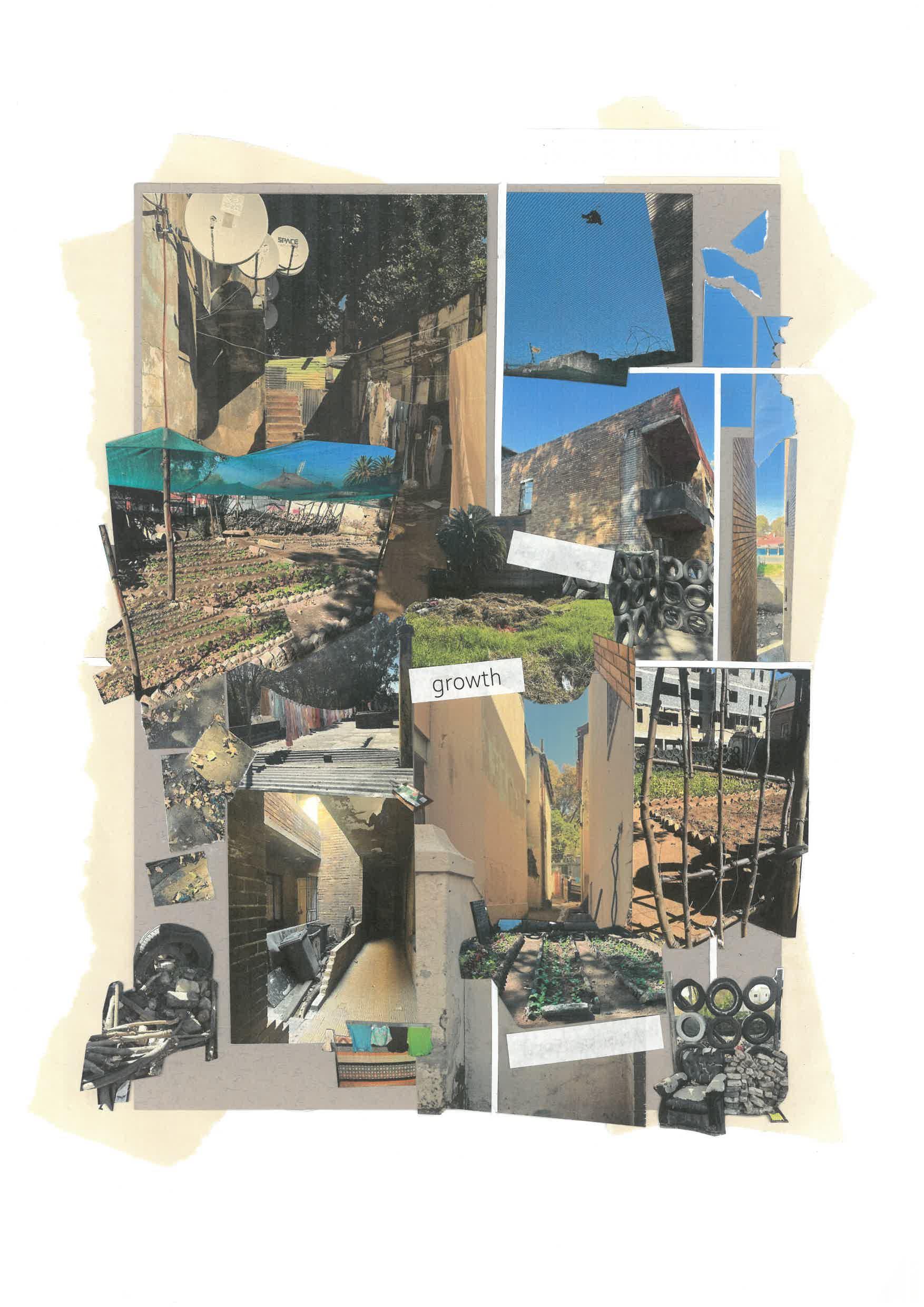

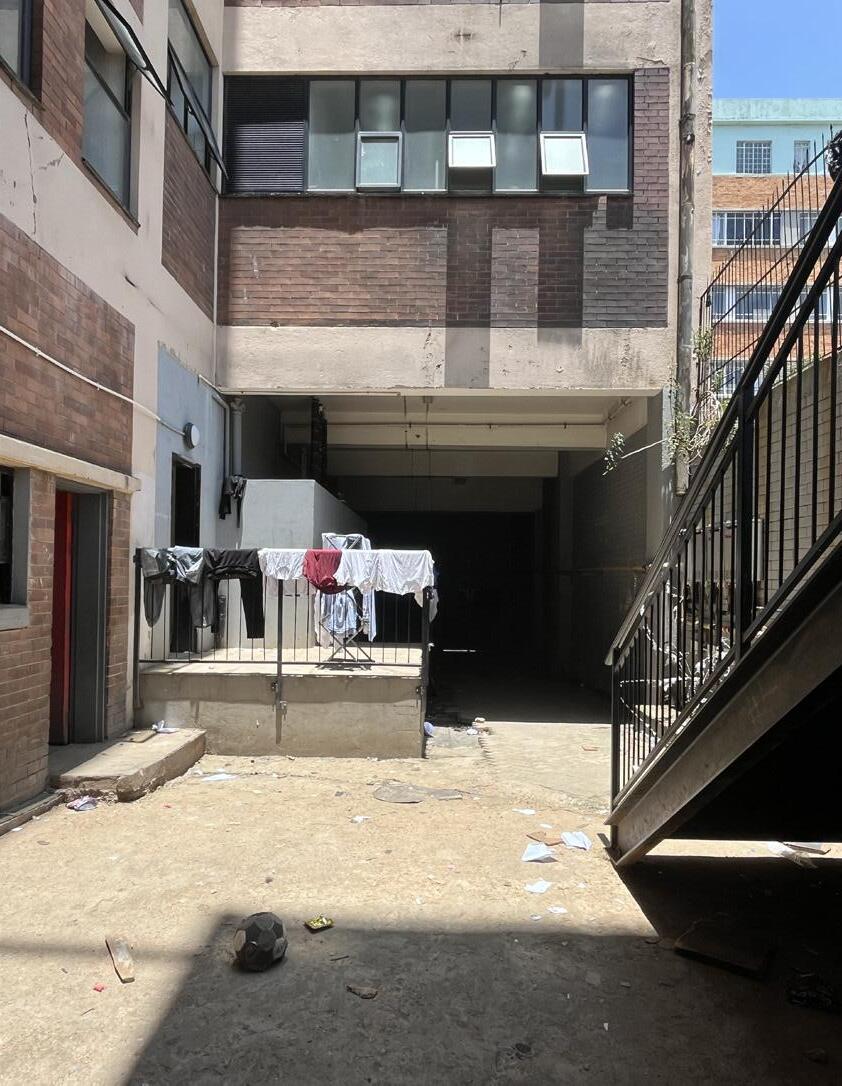

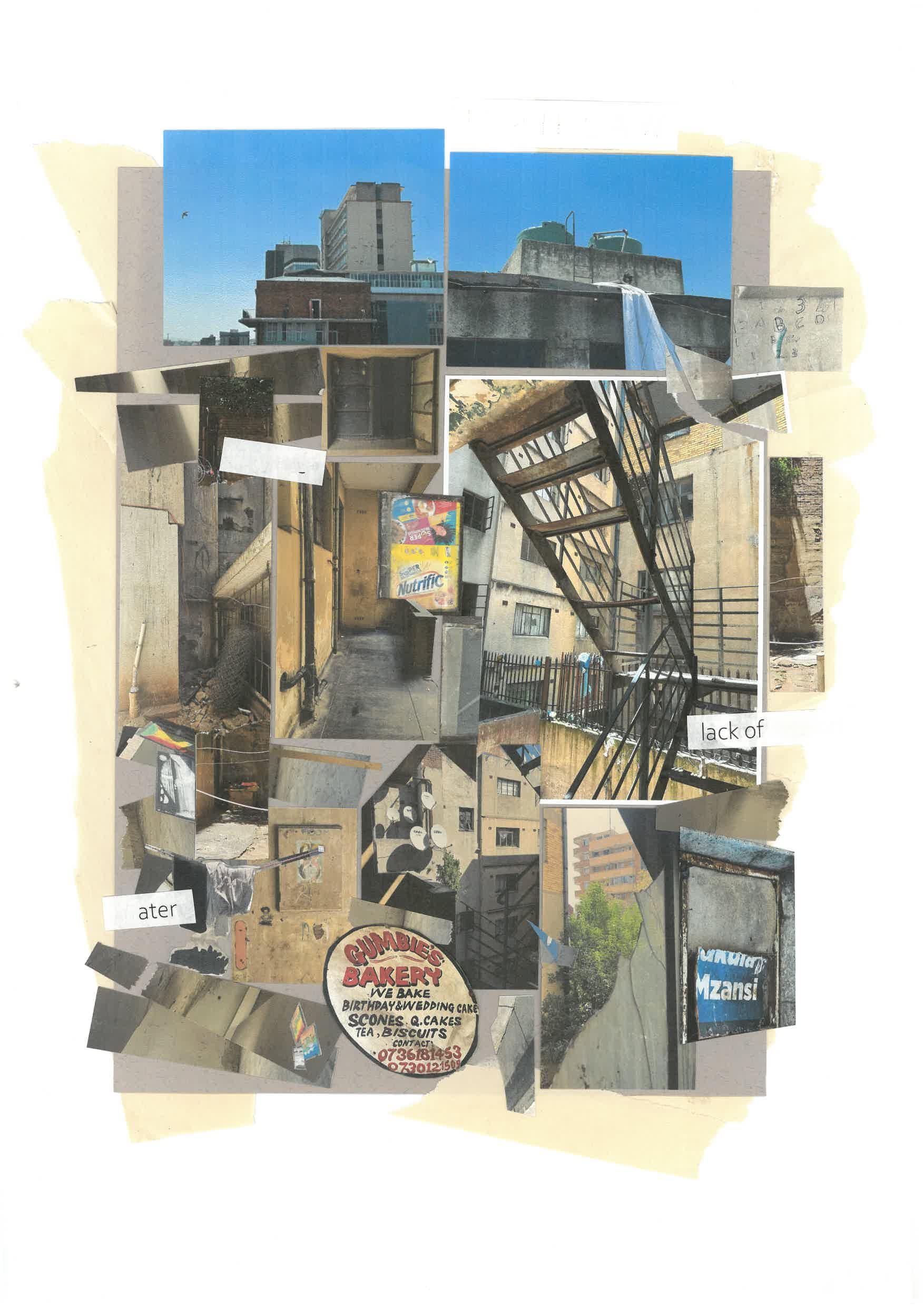

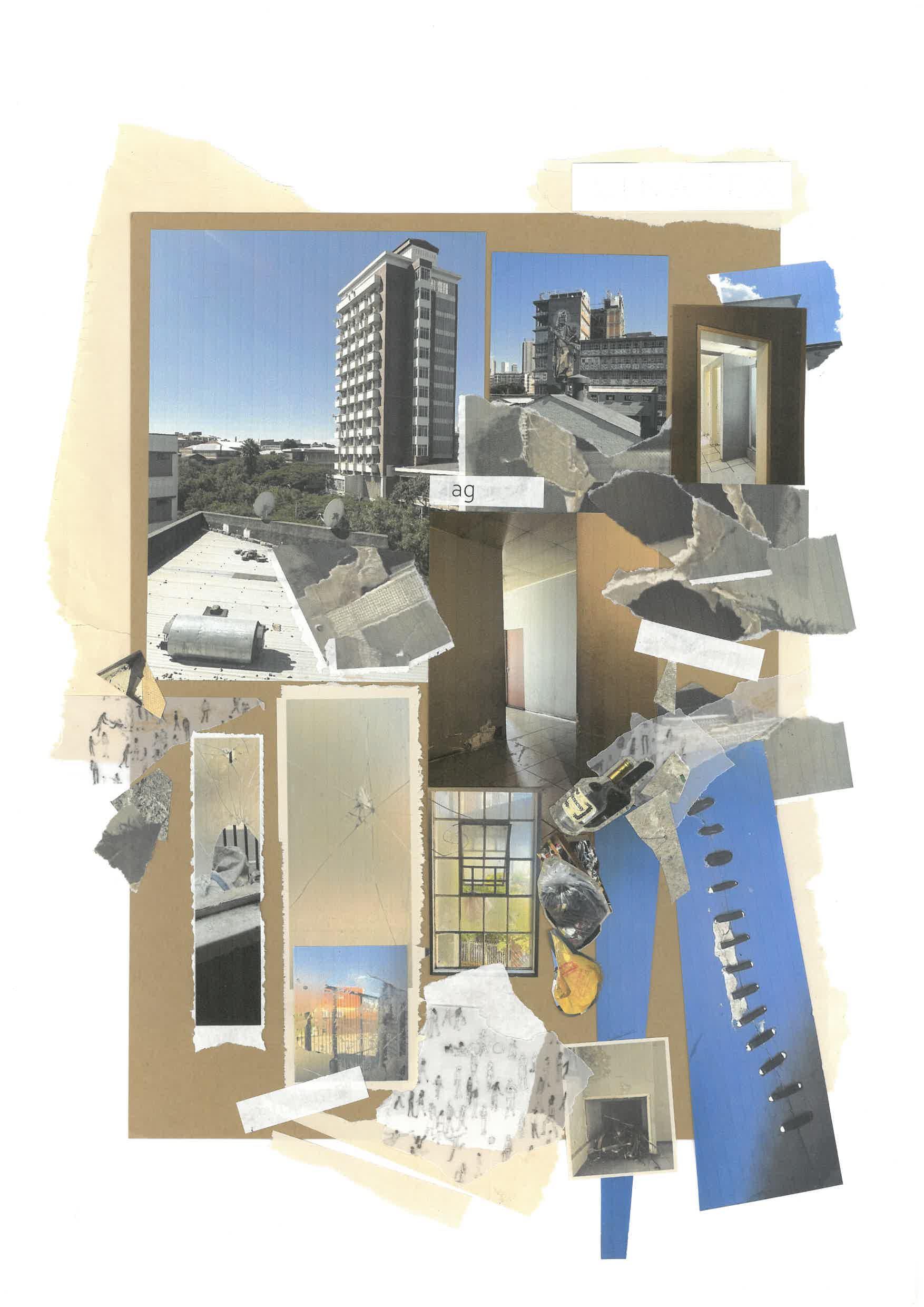

The Bertrams Priority Block, located on the eastern edge of Johannesburg’s Central Business District, comprises a cluster of municipally owned buildings that have been informally occupied since the early 2000s. This area, spanning approximately 25 plots of land between Gordon and Berea Roads, provides homes for over 100 households, predominantly led by women. Despite the absence of formal tenure security, residents have established robust self-governance structures, collectively managing and maintaining their living spaces through shared efforts and contributions.

Faced with eviction threats, particularly during the preparations for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, residents, supported by organisations such as the Inner City Resource Centre (ICRC) and 1to1 – Agency of Engagement, initiated a series of participatory upgrading projects to improve their living conditions and demonstrate their ability to care for the space. These initiatives have included vital repairs to hazardous infrastructure, such as steel staircases and leaking roofs, and the development of communal amenities like gardens and play areas.

The Bertrams Priority Block exemplifies the potential of community-led interventions in maintaining the inner city. It highlights the importance of viewing informally occupied buildings not as problems to be eradicated, but as integral components of the urban fabric that can be co-managed by residents, with inclusive policies and adequate support.

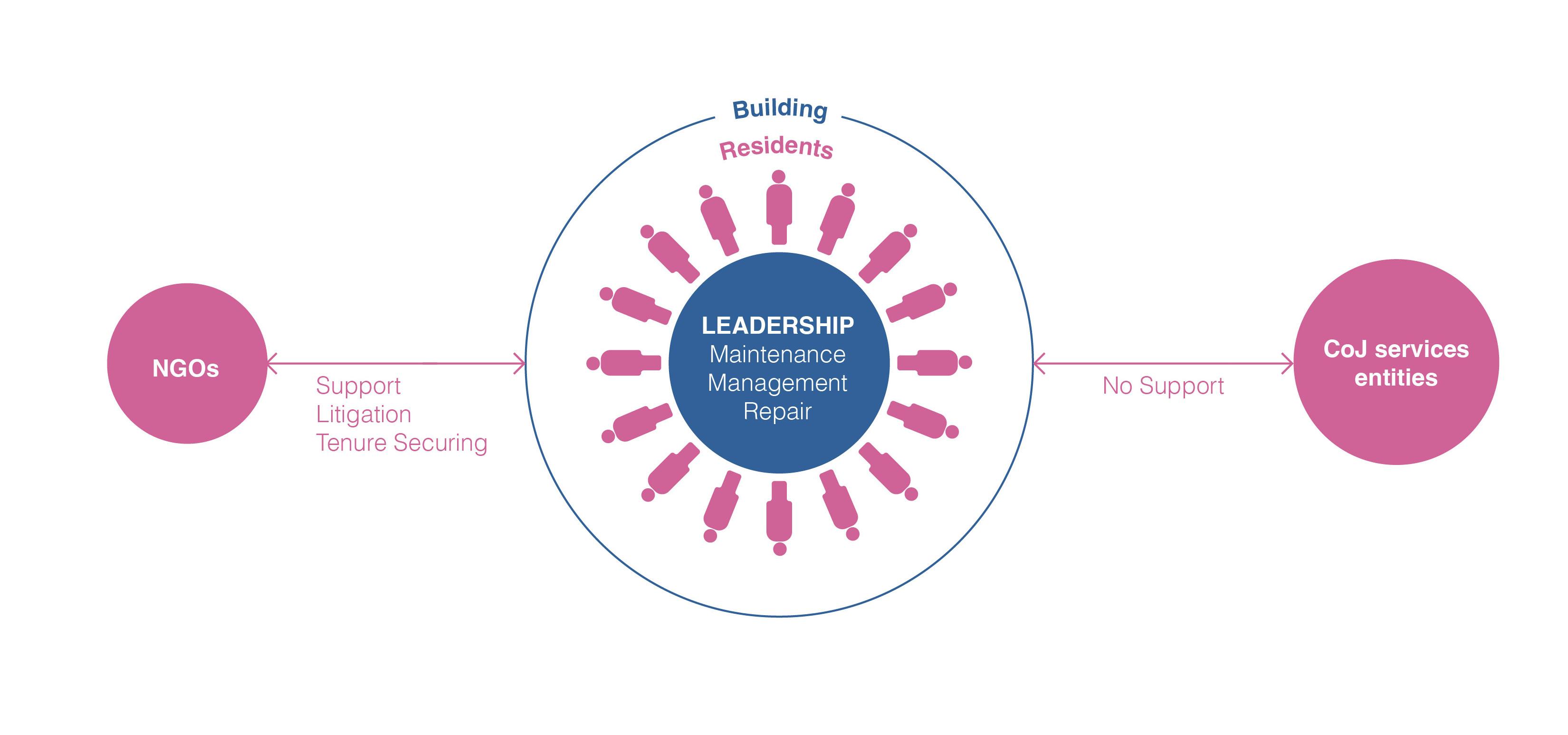

Governance

Bertrams consists of a collection of informally occupied buildings with an absentee landlord. These buildings have been occupied under an informal rental system in place since the early 2000s. Residents manage the upkeep collectively and have established shared governance systems that cover cleaning, repairs, security, and childcare. However, the buildings lack legal access to essential services such as water and electricity, and communication between the building committees and the City of Johannesburg (CoJ) is minimal.

The residents’ lack of legal status or tenure security presents challenges in taking on additional responsibilities for building maintenance or addressing long-term issues. A significant barrier is the restriction on their ability to represent themselves collectively. If they were to incorporate as a legal entity, they could access financial resources (savings and loans) and basic services, enabling them to care for the buildings more effectively.

In recent years, residents have affiliated with the Inner City Resource Centre (ICRC), which supports the upliftment and development of inner-city communities. This partnership has attracted additional support organisations and resulted in improvements in waste management, sanitation, building security, and minor repairs. Additionally, a shared garden has been established, providing space for growing food and leisure activities.

Despite limited resources, residents have shown a strong commitment to maintaining the buildings in Bertrams and improving their neighbourhood. A simple step the CoJ could take to support the gradual upgrading of the inner city would be to enable informal occupants of vacant buildings like these to collectively incorporate, allowing them to manage or potentially own these properties.

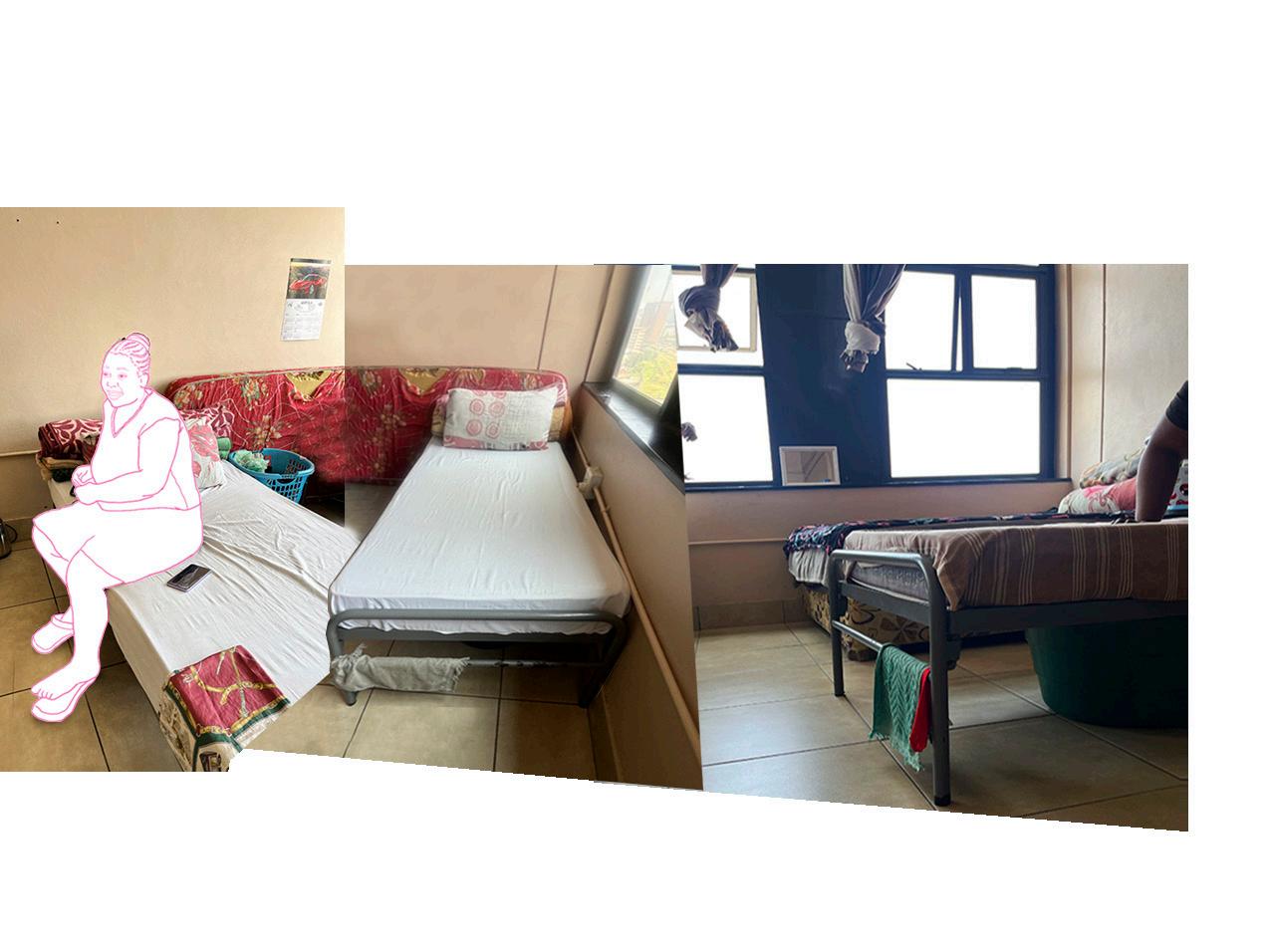

Living in Bertrams Priority Block

Palesa

Palesa is a 40-year-old woman living in a ground-floor unit. Originally from KwaZuluNatal, she moved to Johannesburg in 2012 after finishing school and becoming a mother at 18. Following the end of a long-term relationship, she settled in Bertrams. Palesa lives in a shared unit with her two daughters (22 and 16), two sons (18 and 9), and three grandchildren. She works ad hoc cleaning jobs and is the primary provider for her family, as only one daughter has occasional part-time work. Despite the overcrowded

Tawonga

Tawonga, also known as ‘Rasta’, is a 45-year-old man from Zimbabwe who lives with his brother, Panashi, on the rooftop of one of the residential blocks. He arrived in South Africa in 1998, first living in Hillbrow before moving to Bertrams in 2000. After working for a bakery and a gym chain, he lost his job in 2015. Since 2018, he has run a weekend carwash business. Despite the cramped conditions, Tawonga maintains his space with care and resourcefulness. However, the patched-up roof and a lack of legal electricity and water connections are serious challenges. His dream is to expand and improve his living space to make it more liveable.

Lindiwe

Lindiwe, a 31-year-old woman, has lived on the first floor of one of the residential blocks in Bertrams since 2016. She shares the flat with her 59-year-old mother, who is unwell and housebound, and her adoptive brother. Born in Johannesburg, she moved to East London in 2006, returning in 2015 for work. She lost her last retail job in 2020. Known in the building as ‘the baker’, Lindiwe completed a baking course and dreams of having a proper kitchen to grow her business. She supports the community by organising Sunday cleaning schedules and raising money for shared expenses. Despite her efforts to rally residents to repaint the building, she faces limited participation. Her main concerns are safety, poor sanitation, and a lack of communication amongst residents, and she ultimately hopes to create a safer, cleaner, and more united community.

Sharing Bertrams Priority Block

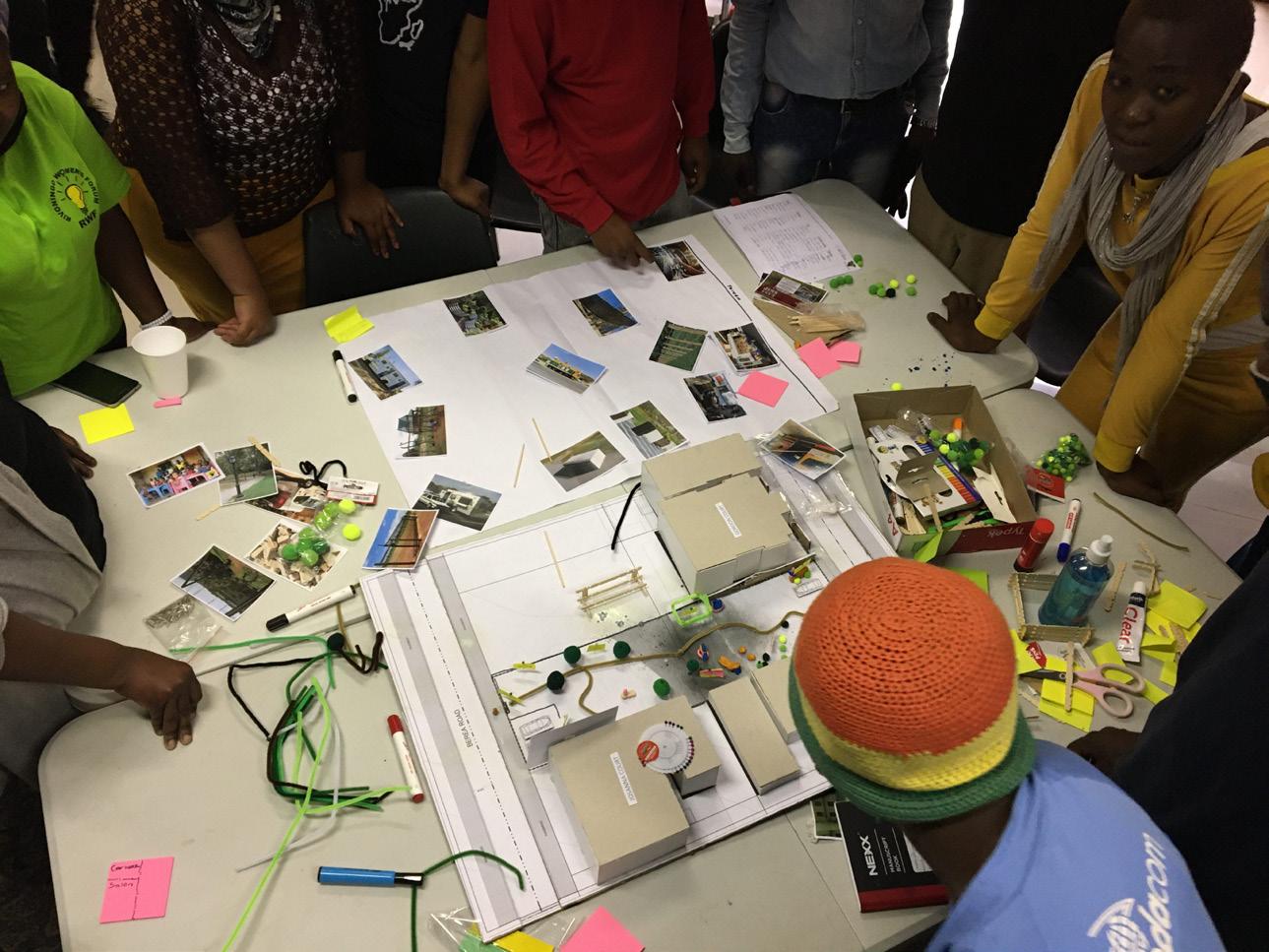

From 2020 to 2021, the Bertrams Priority Block was the focus of a meaningful co-design initiative, supported by the National Research Foundation through Tshwane University of Technology. Key allied organisations, including the Inner-City Resource Centre, 1to1 Agency of Engagement, and Planact, collaborated to transform a shared open space into a hub for community governance and upgrading.

The initiative began with an information campaign called ‘Know Your Neighbourhood’ in September 2020. This led to a discussion where residents analysed their community and envisioned potential uses for their main shared space. In October, a facilitated co-design workshop formalised these ideas. Participants prioritised five key themes: Business, Social Services, Security, Farming, and Children’s Space. With a consensus that working together to maintain the space was a priority, the Community Space Planning Committee was formed to guide the project.

Renamed ‘SHAP Bertrams’ (Strength, Hope, Action, Purpose), the committee refined the proposals, leading to a community garden project launched in December. Despite challenges, residents actively participated in the garden’s development throughout 2020 and 2021, removing waste, preparing the land, and constructing infrastructure like fences. This initiative not only met immediate needs but also fostered a lasting sense of ownership and responsibility, highlighting the effectiveness of involving residents directly in the co-design and upkeep of their living spaces.

Fraser House

A Case for Mixed State and Resident-Led Maintenance

Building

Location

Building Typology

Number of Floors

Structural Material

Partitions Material

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal

Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Ferreiras Dorp

High-rise multistorey building

6

Masonry walls and concrete slabs

Brick

Temporary Emergency Accommodation

Not applicable

Inner City Federation

Building representative appointed by City of Johannesburg

Not available

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

Tap per floor

Toilet per floor

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

Connected with an account with the City

None

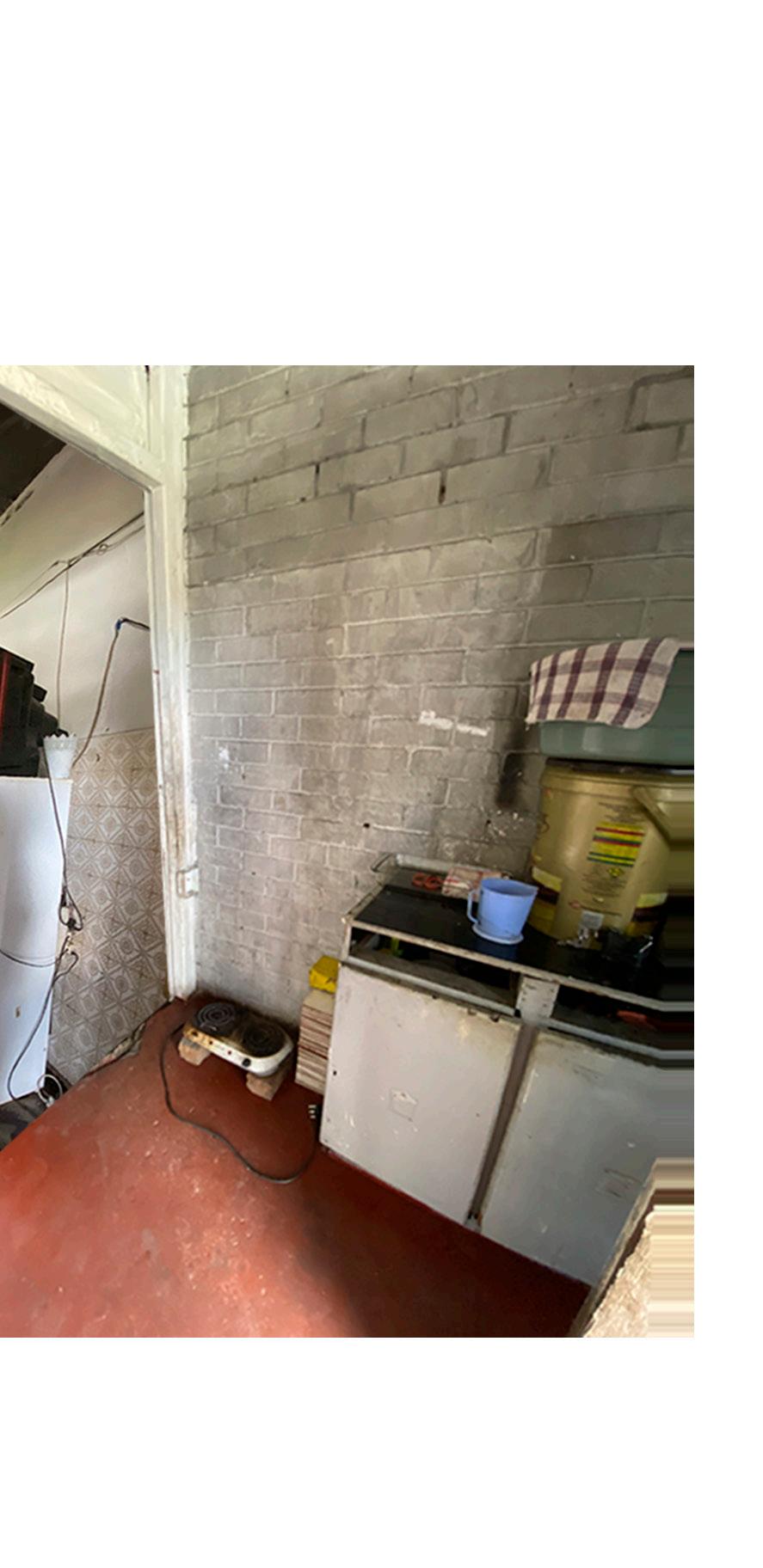

Overview

Fraser House demonstrates the complex dynamics of state-led interventions in Johannesburg’s inner city. Originally a state-owned building, it was designated as Temporary Emergency Accommodation (TEA) as part of the People’s Housing Process (PHP). Intended to house displaced or homeless individuals, the building has since evolved into a form of transitional shelter for over 100 households.

Despite its classification as a ‘homeless shelter,’ Fraser House is not a temporary solution in practice. The building is primarily occupied by South African citizens, including 50 children, and is formally connected to the city’s electricity network. However, water and sanitation facilities are limited to a single tap and toilet per floor, and there is no formal waste removal. The absence of clear governance structures within the building further complicates management and upgrading efforts.

Fraser House represents a critical case for exploring the limitations and possibilities of state ownership, especially regarding tenure security, maintenance responsibilities, and collaborative upgrading. Its position at the intersection of formal intervention and informal adaptation provides key insights into what sustainable inner-city housing might look like under public ownership frameworks.

Governance

Governance at Fraser House, as a Temporary Emergency Accommodation facility, is primarily state-led, with the City of Johannesburg (CoJ) controlling all decisions regarding maintenance, repairs, and tenancy. While residents have established a committee to take on informal leadership roles, their effectiveness is limited. The CoJ often establishes these committees when residents move into a TEA, but without formal responsibility or training, their ability to maintain the building is minimal. This lack of engagement with the CoJ and proper governance practices means the Resident Committee is largely powerless to enact meaningful change, focusing mainly on cleaning common areas and mediating social issues.

The CoJ’s unwillingness to negotiate building rules or formalise tenancy agreements has resulted in tenure insecurity and a constant fear of eviction for residents. This, combined with the community’s limited ability to manage collective resources, has led to a compounding backlog of unresolved maintenance issues.

Despite these challenges, the Resident Committee has built a strong relationship with the Inner City Federation (ICF), which provides training, technical support, and advocates for residents’ interests with the CoJ. This partnership offers a crucial opportunity for the CoJ to devolve some decision-making power to the residents and the ICF, enabling much-needed improvements like fixing the roof, plumbing, and communal kitchens.

By collaborating with the ICF, residents could access resources and funding that, with CoJ support, could be directed toward these critical repairs. A greater role for civil society, coupled with regular forums between the CoJ and TEA Resident Committees, could help distribute the responsibility for building management and maintenance. This would move beyond the state’s sole burden and potentially break the cycle of improvement and decline that is common across the TEA building stock.

Living at Fraser House

Precious

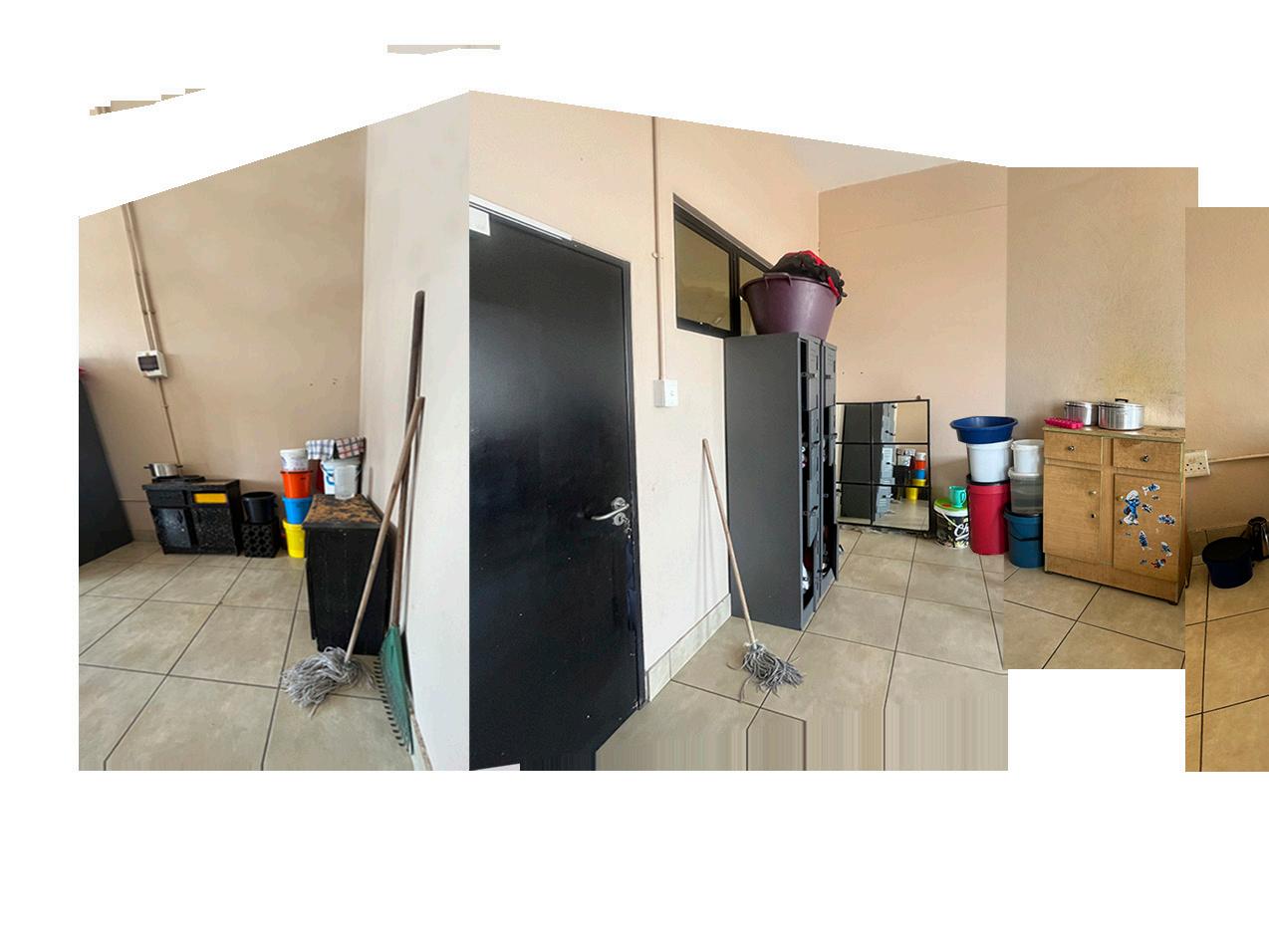

Precious is a 26-year-old woman residing on the fifth floor of Fraser House. We were unable to capture details about her previous housing situation or the year she moved in. She shares her 32-square-metre unit with three other unrelated women. Despite the high occupancy, they maintain a clean and orderly environment. However, building management’s restrictions on hanging pictures and the lack of furniture contribute to a sparse atmosphere. Precious reported that the inability to subdivide the space with furniture or partitions has created tension over its use.

Minenhle

Naledi

Naledi, a 43-year-old and an active member of the Fraser House resident committee, moved into her fourth-floor unit in 2021. For her, the move was a rescue; she describes her new 32-square-metre home as “heaven” compared to the 20 years she spent at a transitional housing facility known as Killy Billy, where she also ran a hair salon. She lives with her three children, ages 22, 12, and 5. Safety is her top concern, especially after a child fell from a window but was saved by a balustrade. She also worries that the building’s disused rubbish chutes are hazardous to children playing nearby. The lack of local healthcare facilities is another challenge, as it forces her to travel to Jeppe for medical care. Her dream is to transform the building into a safer space where children can play freely, study groups can be formed, and small businesses and recycling initiatives can operate with proper permission.

Thandiwe

Thandiwe is a friendly woman in her early 40s who lives on the sixth floor of Fraser House. She previously resided at Killy Billy for five years, but relocated due to its deteriorating condition. She shares a small, 16-square-metre unit with her 20-yearold daughter, who recently completed her matric and aspires to study medicine. Despite their limited space, their home is neatly arranged, with a dedicated sleeping area, kitchen appliances, a TV, and storage. A space for yoga, layered net curtains, and flowers on the table help her make the space her own. While Thandiwe is concerned about the violence in the building, she feels it’s significantly less than what she and her daughter experienced at Killy Billy, and she maintains a positive outlook on their living situation.

Sharing Fraser House

Fraser House hosts several shared spaces; however, a sense of hesitation and uncertainty keeps them largely underused. The building features wide hallways, a kitchen on each floor, a rooftop area, a ground-floor courtyard, and communal toilets and showers on every level. Despite their potential for daily life and social connection, the use of these areas is limited by restrictive rules and minimal infrastructure. For instance, the kitchens are equipped with only a sink, a few sockets, and a countertop, while residents are discouraged from gathering in open areas due to curfews and noise restrictions.

Residents, however, have a different vision for how they would like to utilise the building’s open spaces to complement what is available in their individual units. They imagine communal kitchens that encourage connection and shared meals, as well as floor-level spaces for childcare, training, meetings, or events. Many hope for a rooftop garden to grow herbs and plants, and some envision areas for trading everyday goods and sharing the diverse skills present within the building.

While current governance arrangements strictly limit residents’ ability to implement these changes, the collaboration between the Resident Committee and the Inner City Federation offers a practical path forward. This partnership could help facilitate the reorganisation of shared spaces, transforming them into functional areas that support residents’ daily lives.

Snapshots

Jean Law Court

Building

Location

Building Typology

Number of Floors

Structural Material

Partitions Material

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Braamfontein

High-rise multistorey building

7

Masonry walls and concrete slab

Brick

Owned by the City of Johannesburg; currently under an eviction order; an informal rent agreement with partial payment is ongoing

1991

Inner City Federation Resident-led building management structure

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

In most units

Toilet per floor

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

None

None

Overview

Jean Law Court is a seven-storey building owned by the City of Johannesburg, but it has been informally occupied since 1991 and is under a pending eviction order. The building is home to 22 households, 70% of which are foreign nationals, and is characterised by fragmented occupancy and legal uncertainty.

Residents live in brick-partitioned units with limited access to basic services—just one toilet per floor and no formal electricity. Despite these conditions, the building has a functioning resident-led management committee and is affiliated with the Inner City Federation (ICF). Jean Law is a critical case study for understanding the effects of absentee ownership and the legal ambiguities of municipally owned buildings. The case highlights how urban policy, xenophobia, and spatial justice intersect, making migrant populations particularly vulnerable during evictions.

With the building now being reassessed for potential upgrading, there is a timely opportunity to mitigate eviction threats. This can be achieved by strengthening community organisation, conducting professional assessments (like fire safety and engineering), and pursuing legal advocacy to transform ownership and tenure structures.

Linatex House

Building

Location

Building Typology

Number of Floors

Structural Material

Partitions Material

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal

Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Doorfontein

Multiple low-rise, multistorey walk-up buildings

3

Masonry walls and concrete slab

Drywalls

Temporary Emergency Accommodation

2005

Inner City Federation

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

Tap per floor

Unknown

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

Connected with an account with the City of Johannesburg

None

Overview

The Linatex building, a repurposed industrial structure on the outskirts of Johannesburg’s central business district, has been informally adapted into a multi-household residential building. Its open floor plan and sturdy construction have allowed residents to subdivide the space with informal materials like plywood and reclaimed bricks. While this offers flexibility, it also creates fire risks and restricts air and light circulation.

The building lacks formal sanitation and water infrastructure, with limited shared access and no consistent waste removal. The informal electricity connections often lead to risks of overloads or fires. Despite these challenges, Linatex has a cohesive community with its own governance system, which includes cleaning rotas and informal dispute resolution.

Residents are now collaborating with grassroots organisations, such as the Inner City Federation (ICF), to explore upgrading options. The Linatex case demonstrates the potential of upgrading industrial buildings in-situ, particularly when a strong community is already established. It highlights the need for creative, safety-focused retrofitting that respects current living arrangements while expanding formal support.

Building

Location

Building Typology

Number of Floors

Structural Material

Partitions Material

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal

Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Hillbrow

High-rise multistorey building

10

Masonry walls and concrete slabs

Brick

Unknown (ex-TEA, referred to as Old Perm)

Unknowkn

Inner City Federation

Unknown

111 (444 people)

100%

0

Unknowkn

Unknowkn

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

Tap per floor

Toilet per floor

None

Connected with an account with the City of Johannesburg

None

Overview

Old Pem is a ten-storey building that exemplifies inner-city adaptive reuse in Johannesburg. Originally designed as an industrial facility, it has been informally repurposed into a highdensity residential space. Currently, it accommodates 111 households, all of which are South African, and maintains loose connections to the Inner City Federation.

Despite its industrial origins, Old Pem now functions as a live-work environment, integrating informal economic activities with residential living. The building’s water and sanitation facilities are limited to one tap and toilet per floor, and it lacks a formal waste removal infrastructure. Electricity is supplied through a municipal account, although the internal distribution appears to be informal.

What sets Old Pem apart is its potential to serve as a precedent for hybrid residentialcommercial upgrading, focusing on both safety and economic opportunity. The building benefits from relatively strong leadership and organisational cohesion, providing a promising foundation for participatory upgrading processes. As a featured site in the Kanpepe Report, Old Pem represents a model for reimagining industrial structures to address urban housing shortages while preserving the informal livelihoods they often support.

Walpert Motors

Building

Location

Building Typology

Number of Floors

Structural Material

Partitions Material

Governance

Tenure status

If occupied informally, start date of current occupation

Affiliation with grassroots organisations

Leadership and other forms of resident organisations

Occupants

Number of households

South African occupants

Foreign national occupants

Children (under 18)

Elders (over 65)

Quality of Occupation

Prevalent dwelling typologies

Water access

Sanitation

Waste removal Electricity

Other known shared spaces and infrastructure

Jeppestown

Converted low-rise single-storey factory

1

Masonry walls and concrete slab (to be verified)

Bricks

Unknowkn

Unknowkn

Inner City Federation

Unknowkn

45

Unknowkn

Unknowkn

10

5

Single room units shared by multiple occupants

Tap per building

Toilet per building

Waste bins collected by the City of Johannesburg

None

Shared courtyard spaces between buildings

Overview

Walpert Motors is a former commercial garage in Johannesburg’s inner city that has been informally transformed into residential accommodation. Originally designed with expansive open-plan interiors, the building has been subdivided into makeshift residential units using temporary materials like timber, board, and sheet metal. These adaptations have resulted in dense living conditions that lack adequate ventilation, insulation, and formal safety infrastructure.

Sanitation facilities are improvised, with limited access to toilets and no formal waste removal system. Electricity connections are irregular and often hazardous, increasing the risk of fire. Despite these significant challenges, Walpert Motors is home to a tight-knit community of residents who have established informal systems of governance and mutual support.

This building exemplifies inner-city spatial transformation driven by necessity. Its case raises critical questions about the intersections of safety, dignity, and regulatory frameworks when commercial buildings are repurposed for residential use. Walpert Motors presents unique opportunities for envisioning modular, low-impact upgrading solutions—such as mobile ablution blocks, fire safety retrofits, and incremental infrastructure improvements—that cater to the specific spatial conditions of industrial-to-residential conversions while ensuring that existing residents are not displaced.

Conclusion

The stories captured in this report confirm that inner-city buildings, regardless of their legal or structural status, are essential to providing housing for Johannesburg’s lowerincome residents. The case studies of Argyle Court, Bertrams Priority Block, and Fraser House, along with the snapshots of Jean Law Court, Linatex, Old Pem, and Walpert Motors, consistently reveal a central truth: the inner city’s housing future is not found in a policy of demolition and displacement. Instead, it lies in the resourcefulness and resilience of residents who are already actively engaged in maintaining and repairing their homes and communities.

This report challenges the dominant narrative that portrays informally occupied buildings as “bad” or ungovernable. Our findings demonstrate that despite residents’ precarious legal status, there are often well-organised, self-managed communities. For decades, residents of several buildings across the inner city have established their own systems for governance, security, maintenance, and resource collection—from the efficient Task Team at Argyle Court to the grassroots co-design initiatives at Bertrams Priority Block. Their practices of maintenance and repair, often bridging the gaps left by absent landlords or inadequate state services, are a testament to the residents’ commitment and ability to create dignified living conditions, when adequately supported.

However, these organic, community-led efforts are continually undermined by significant systemic barriers. A lack of tenure security, unstable urban governance, limited financial access, and a restrictive policy environment create a cycle of precarity and neglect. As seen in the constant threat of eviction at Jean Law Court and the limited access to services at Linatex, these issues prevent residents and their organisations from making long-term, structural improvements. Rather than being the cause of the city’s decline, our research shows that these communities can also be viewed as its most active agents of preservation, working in a system that often fails to recognise or support them.

For genuine transformation to occur in inner-city Johannesburg, there must be a fundamental shift in how local government and other stakeholders engage with these communities. The path forward is not through removal and securitisation but through a proactive strategy of recognition and support. This means formally acknowledging self-managed communities as legitimate co-producers of the city. By implementing policies that provide tenure security, financial support, and capacity development— similar to successful models in informal settlements—local authorities can empower residents to scale up their efforts and create safer, more stable homes.

These communities aren’t the cause of the city’s decline; they are its most active agents of preservation, working in a system that often fails to recognise or support them.

The case of Walpert Motors, for instance, highlights the potential for modular, lowimpact upgrading solutions, while the Linatex and Old Pem cases show the promise of retrofitting industrial spaces to support both residential and economic livelihoods. Achieving this requires sustained commitment and cross-sector collaboration grounded in the voices and lived experiences of residents and their allies.

This report serves as the diagnostic foundation for this approach. By detailing the living conditions, self-management mechanisms, and key challenges across these seven buildings, we provide a rich evidence base for a more just and inclusive urban future. It is our hope that this publication will not only document these stories but also serve as a strategic instrument in the ongoing struggle for adequate housing in the inner city, contributing to future efforts to collaboratively build a city grounded in justice, solidarity, and shared stewardship.

Acknowledgements

This report presents a selection of findings from the Change by Design workshop series, a multi-year initiative held in Johannesburg from 2023 to 2025. The Change by Design programme is a longstanding initiative of Architecture Sans Frontières UK, while the Johannesburg workshop series was an initiative by ASF-UK and 1to1 – Agency of Engagement.

We extend our sincere gratitude to our collaborative partners: the Inner City Federation (ICF), the Inner City Resource Centre (ICRC), the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI), and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). This project was also made possible by the invaluable support of many organisations, including Oskotheni, Planact, and Ndifuna Ukwazi, along with several universities: the University of the Witwatersrand, University of Johannesburg, University of Cape Town, London Metropolitan University, University College London, and the University of Sheffield.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Allford Hall Monaghan Morris (AHMM), without which this publication would not have been possible.

We would like to extend our thanks to the dedicated facilitators from ASF-UK and 1to1 – Agency of Engagement who made this work possible. Our coordinators were Jhono Bennett, Jacqui Cuyler, and Beatrice De Carli, who were joined by Nick Budlender, Kathryn Ewing, Tahmineh Hooshyar Emami, Tamara Kahn, Rowan Mackay, Sifiso Mtimunye, Francesco Pasta, and Valentina Riverso.

We are also incredibly grateful to the workshop participants for their invaluable contributions:Ana Muñoz Antuña, Clare Chappel, Lucy Olivia Earle, Shannon Fisher, Veronica Frederico, Oana Gavris, Noluthando Geja, Nomvuzo Gingcana, Florence Gule, Monica Hassamo, Jinty Anne Jackson, Nubumbi Kabongo, Bevil Lucas, Siyabonga Mahlangu, Gcina Malandela, Zainab Al Mansour, Marcelle Mardon, Giacomo Martinis, Percy Masango, Dumisani Mathebula, Harriet McKay, Angelique Michaels, Balungile Mntaka, Hiba Mohamad, Muhammad Moola, Bonginkosi Ndlovu, Lizwelthu Ndlovu, Ebenezer Kofi Okyere-Dede, Giulia Peruzzo, Julia Phora, Retsepile Rammoko, Lauren Royston, Suraya Scheba, Marika Searle-Krokidas, Sabine Surkan, Itumeleng Tlokotsi, Cornelia Busiswa Tsibiyana, Katarzyna Wardach, Diana Zambelloni, Sifiso Zuma.

A special thanks goes to the many guest speakers who generously shared their knowledge of the inner city, particularly Heather Dodd, Althea Peacock, and Matthew Wilhelm Solomon. Heather Dodd’s work was an especially important source of inspiration for our efforts in documenting occupied buildings from an architectural perspective, which greatly informed our workshop discussions and outputs. We are also grateful to the friends and collaborators who attended our public sessions, as their thoughtful contributions were invaluable in helping us explore the complexities of life in inner-city Johannesburg.

Our deepest gratitude goes to the leadership and representatives of the Inner City Federation and the Inner City Resource Centre for guiding us through the inner city, and to all the residents who entrusted us with their life stories. We hope this publication serves as a useful tool in your ongoing struggle.

Change by Design Johannesburg

Change by Design Johannesburg is a collaborative initiative led by ASF-UK and 1to1 Agency of Engagement. Since 2023, we have been working alongside residents and community organisations in inner-city Johannesburg to advocate for community-led solutions for adequate housing.

Architecture Sans Frontières UK (ASF-UK) is a non-profit organisation working to transform cities through community-led design and planning. We amplify the voices of those most affected by urban change, building collective power for more just and sustainable cities.

www.asf-uk.org

Architecture