From the Editor

What is it that makes us human beings created in the image of God? This question has seemed to be swirling around the church as a foundational question beneath the widespread news of Artifcial Intelligence (AI), and it is a question which seems to generate a lot of fear. But it is also a question which often emerges as we consider the complex question of human culture, and the variations we fnd in the feld of Anthropology (albeit not with the religious element). Both subjects were addressed in 2024 at Asbury Theological Seminary in the Advanced Research Programs Interdisciplinary Colloquiums. The frst was held on Friday, March 15, 2024, and the papers were around the subject of AI (Artifcial Intelligence) and Higher Education. The second was held Friday, October 11, 2024, and operated under the theme of Theology, Bible, and Human Cultures in a Changing World. While they both seem like very separate themes, there is a commonality in both wondering what is essential to being human, and how does a Christian worldview see God as being involved in what makes us truly human.

The frst three papers in this issue of The Asbury Journal come out of the discussion on AI. Chris Kiesling, Asbury’s Professor of Christian Discipleship and Human Development leads with his keynote address, as he seeks to untangle the positive and negative aspects of AI and how they might impact the educational work we do. In addition, he shows how some in the feld of AI seek to turn humans into gods. Aaron Lewis presented a student paper which took a philosophical approach to the question of AI, building on Aristotle’s classic views on virtue along with the theology of Aquinas, and wondering if AI usurps human decisions by replacing rational, ethical action in the decision-making process with mechanical replacements which ultimately undermine human virtue. Thomas Hampton presented another student paper in the colloquium, looking at the contributions of Alfred North Whitehead and Catherine Malabou to the development of AI. Whitehead’s top-down view of causality connected to God and Malabou’s view of plasticity, both provide profound ways of exploring human thought processes in an age of AI.

The next two papers come from the second colloquium. Shishou Chen explores the symbols used in the book of Revelation and how these symbols emerged from multiple cultural and religious sources as a way for John to critique his cultural world. Chen further elaborates on how a similar use of cultural symbols could permit Chinese Christians to build on ancient Chinese concepts of Tian or Heaven, as they seek to understand Christianity from a Chinese cultural viewpoint. Sophia H. Y. Huang takes a similar approach in exploring the socio-cultural dynamics of the resident immigrants referred to in 1 Peter. She argues that they were not necessarily the poor marginalized people we often imagine, but they did often try to avoid civic responsibilities which included religious observances in honor of Roman rulers or deities. She explores how this might reframe our reading of 1 Peter.

While human beings need to be understood as separate from any machine technology we build, and we also need to be understood within our cultural and social frameworks, it is equally important to understand the religious dimension which sets us apart as being made in the image of God. Two long-time theological scholars present articles on holiness, which may well be the concept that best connects human beings to God, whose image we are called to represent. Don Thorsen argues the importance of holiness as a concept which binds the Church together in its community witness. It is that concept which connects how we view the nature of God in line with how we live our own individual lives, and how that in turn binds us for how we reach out in the love of God to a hurting world seeking justice. Laurence W. Wood, one of my long-term predecessors as editor of The Asbury Journal, presents an historical view of holiness as it developed in the life and theology of John Wesley, and ultimately emerged as a guiding principle for H.C. Morrison, the founder of the Seminary, and E. Stanley Jones, for whom the School of Mission and Ministry is named. This historical and theological reminder helps us see that as human beings made in the image of God, we are called to live out the characteristics of God through the power of the Holy Spirit within us.

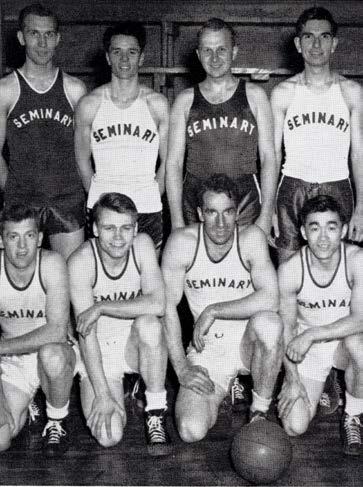

The fnal two articles, as well as the From the Archives essay, examine this holiness in action, lived out in history. Robert Danielson explores the life of a little known African American woman tied to a radical branch of the Holiness Movement. She exhibits much of the type of spirituality which would infuence white holiness groups in terms of worship, and which would emerge in early Pentecostalism as well. Nicholas Railton

explores Methodist views of Jewish people and the state of Israel over time, from the founders of Methodism through modern critiques taken from the news of today. Whether the reader agrees with Railton’s conclusions or not, it is certainly time for the Church to engage modern issues like these through an historical and theological lens which seeks to bring holiness and the love of God to the current concerns of humanity. Finally, in the From the Archives essay, I bring to light a little-known story of the history of Asbury Theological Seminary, and how the issue of holiness played out on the basketball court. As Asbury students desired to form an intercollegiate basketball team, traditional holiness leaders were in opposition seeking to defne how Christians should interact with the wider culture around them.

Back to the question, what makes human beings in the image of God? Romans 1:20-23 (ISV) provides a bit of a hint,

For since the creation of the world God’s invisible attributes- his eternal power and divine nature- have been understood and observed by what he made, so that people are without excuse. For although they knew God, they neither glorifed him as God nor gave thanks to him. Instead, their thoughts turned to worthless things, and their senseless hearts were darkened. Though claiming to be wise, they became fools and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images that looked like mortal human beings, birds, four-footed animals, and reptiles.

Science may invent machines which are more intelligent than human beings. Machines which can run faster, last longer, learn and process more information, machines which look, speak, and respond like human beings. These machines may take away our agency and even our creative impulses, but will they ever be capable of love- true love which emerges from an intimate relationship with the Lord of the Universe? Will they be capable of true worship or expressing genuine thanks to the God who created the world around us? Sure, they can be programmed to go through the motions and say the right thing at the right time, but human beings were made in the image of God to be a holy people, a people set apart from the rest of creation to glorify God and give God thanks. The vast diversity of cultures found in humanity display many lenses through which this worship and thanksgiving can be given, but in each case, it comes from the heart, and not because we have been programmed to give it. Our humanity comes from God, is to be shaped by the holy character of God and is too be returned in the acts of worship and thanksgiving. If this is our understanding

of being human beings created in the image of God, then no machine can ever replace us. Human beings as pointed out in Romans become focused on making human beings into God. Whether old fashioned idols or modern technology, people seek to replace God but can never be creators at the same level as God. Romans reminds us that this attitude is foolishness and only serves to make us forget all of the wonderful things God has made, including human beings. As Psalm 8:3-5 (ISV) states,

When I look at the heavens, the work of your fngers, the moon and the stars that you establishedwhat is man that you take notice of him, or the son of man that you pay attention to him? You made him a little less than divine, but you crowned him with glory and honor.

It is this relationship with Almighty God which defnes our humanity, and no robot or simulation will ever be able to call themselves a child of God.

Robert Danielson Ph.D

The Asbury Journal 80/2: 306-325

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.02.2025F.02

Chris A. Kiesling AI and Higher Education

Abstract: This article originated as the keynote address for the 2023-2024 Advanced Research Programs Interdisciplinary Colloquium on “AI (Artifcial Intelligence) and Higher Education” held on Friday, March 15, 2024. At the time, new advances in artifcial intelligence (AI) were just beginning to become prevalent in mainstream media, catching the attention of academic communities. The aim in the address was frst to introduce concepts that would help our community navigate the landscape of artifcial intelligence. Second, this paper sought to provide some sense of how vast the impact of artifcial intelligence might be, focusing especially on how it might impact higher education. Third, was a desire to awaken the attendees to some of the particularly theological issues and challenges that AI is likely to present. With advancements in AI now coming so quickly, there was both a fair amount of speculation and the probability that by the time this article reaches print, much of what was novel at the time of presentation may have already become common knowledge. Much has been retained here for the sake of those who may still be seeking the objectives stated above.

Keywords: artifcial intelligence, higher education, theology, technology, seminary education

Chris A. Kiesling is Professor of Christian Discipleship and Human Development at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky. He is the co-author of Spiritual Formation in Emerging Adulthood: A Practical Theology for College and Young Adult Ministry with David P. Setran.

In January of 2024 a Barna study focused on How US Christians Felt About AI and the Church. When introducing the fndings in an online post, David Kinnamam named four categories that pose an intriguing way to distinguish among various feelings toward artifcial intelligence.1 If you had to choose one answer to the following question, which would most characterize you: When it comes to engaging Artifcial Intelligence, I feel: Compelled? Curious? Concerned? Or confused?

If you chose “compelled,” an interesting follow-up might be to inquire about your age range, as Barna reported that older generations selfscored as more “concerned” (or skeptical) than “curious” about artifcial intelligence. This was in contrast with Gen Z and Millennials who selfreported being more “curious” and “compelled” than “concerned.” If you chose “curious,” it might be interesting to note a Christianity Today article that pondered the following question with input from experts – “Would you be more inclined to ask a question about God to CHATGPT or to Google?”2 It’s a question that in my own small, convenience sampling also yields differences between the generations with equally different rationales. If you chose “confused,” you are certainly not alone. If AI by itself is hard to comprehend it becomes more complex with the tsunami of new applications and accompanying terminology that inundate us daily. Perhaps we can take heart that only fve or so years ago most of us were asking “what’s a Zoom meeting?” wondering if we could ever master the technology. If you chose “concerned” it would be noteworthy to ask if the worry is over a future, dystopian existential threat or whether the concern is more with the possible daily effects that may infuence us in our use of AI. Another interesting question to ponder is this - if you have ever found yourself concerned with the prospect of a self-driving car, would you feel safer with a self-driving plane?

In the early season of a new technology, it is not surprising to fnd a wide range of responses varying in our degrees of receptivity and/or resistance. Yet, we should also note that whether aware of it or not, most all of us are already immersed in using some form of artifcial intelligence. If you have used google maps, sent an e-payment, used an auto correct feature on your phone or laptop, given a directive to Siri, texted with a chatbot, or been asked for a facial recognition login or entrance, you have already been engaging with artifcial intelligence. For the sake of stretching the imagination, let me offer a thought experiment that projects into the future, (perhaps less than a decade from now) - a harvesting of what

artifcial intelligence pundits are projecting may be possible. Imagine that you taught at a university that had suffcient time and money to make a wholesale investment into optimizing the use of artifcial intelligence in the enterprise of teaching and learning.

Hypothetically, consider that every student after being admitted into your university was granted a personal robot that would accompany them throughout their matriculation at your university or seminary. For the sake of raising the stakes, let’s suppose that in the case of misplaced identity your students chose to nickname the robot after the Greek word for the Holy Spirit and named this bot, “Cletus.” Cletus would be programmed to serve as the student’s academic advisor – suggesting the particular courses the student should take, when they would be available, and providing access to all the material resources and directives needed for each particular course. Cletus would also serve as the student’s fnancial advisor calculating how much money they had to spend each semester and providing notifcation when there was an excess of withdrawals. Cletus would also serve as a mentor, being programmed to coach the student on how to study and it would generate questions to test the student’s comprehension over what they were assigned to read. Your student could ask the bot to take on the persona of a historical fgure and create an imaginary dialogue, or debate with the student; or if you wanted the student to gain a feel for what it might have been like to visit the ancient tabernacle, Cletus might design a virtual tour using 3D imaging, complete with a hologram priest to guide your visit. We could imagine Cletus serving as life coach, reminding the student to take their medications, get adequate rest and exercise, and monitor their diet as it would become a sort of Fitbit on steroids. If you harbored animals at home, Cletus could be trained to look after your pet iguana, and if we really wanted to push the envelope, we might even dare to consider that Cletus could serve as a junior Spiritual Director (though most of us for good reason might object and insist on human touch for all things spiritual).3

Imagine as well that you as a faculty member also had a robot that could serve as your personalized administrative assistant. Let’s name her Sophia (the actual name given to one of the world’s most sophisticated robots at the time of this writing.)4 Sophia could accompany you to meetings and summarize the main conversation points. She could absorb the notes you use to teach class and from them generate frst drafts of books. Sophia could create and monitor your own professional development plan; cowrite with you research articles; and though you may have never shown any

signs of an anxiety attack or a seizure, it could alert you to early warning signs if something like reading an article on artifcial intelligence in The Asbury Journal signaled overwhelming systemic distress.5

Assume fnally that the university permits the use of facial recognition software so that Sophia could record any moments in class when any particular student showed signs of fatigue and distraction. Sophia could then clip the video recording of the portion of the class that the student checked out of and transmit it to Cletus. Cletus could then take into account that student’s learning style preference, the history of where they have struggled to grasp concepts in that unit of material and customize a learning assignment designed to bring that student at their own pace to a profcient level of mastery. Further, if you as the student preferred, you could have Cletus translate the assignment into your native language; or you could hear it presented in your professor’s voice, unless of course you as the professor decided (and the law permitted) that the student had instead programmed Cletus to communicate all assignments in the voice of James Earl Jones, or say, Taylor Smith. Finally, Cletus could track your progress in such a manner that you could graduate, not when you completed all your classes, but as soon as you demonstrated mastery of all required competencies. (Note: This imaginative exercise came to mind after listening to a TED Talk from Sal Khan at the KHAN academy. They were not yet using autonomous robots, but they were generating simulations via laptop. In one assignment related to a unit on The Great Gatsby, students were asked to exchange text messages with a personifcation of Gatsby himself. So realistic did this feel that one student ended their exchanges by apologizing to Mr. Gatsby for taking up so much of his time.)6 Now let me come back from the imaginative and hypothetical and chronicle changes that may already be encroaching on the lives of faculty and students.

The Evolving Role of the Professor

Faculty who have experimented with artifcial intelligence to test how well it could a) generate learning objectives, b) suggest teaching methodologies or c) generate resources for a topic, may have noticed a shift beginning to occur in the role of the professor illustrated by the following progression:

The leftmost column represents the historical role of the faculty. Certainly, there was more to the professorate than determining the content of a class, but this particular aspect of the role was largely under the domain of the

professor. Enrolling in an educational institution was the best way to gain access to this knowledge and the delivery of the content usually occurred in a geo-physical setting. With the onset of online learning and multipledelivery systems, many schools begin to hire an instructional designer. Typically, the professor still provided the content for the course and set many of the parameters, but the way the course was designed and content delivered was augmented by the assistance of an instructional designer. With artifcial intelligence, both the content of a course and the course design may be augmented by technology as ChatGPT is solicited to generate learning outcomes, locate best resources, suggest learning exercises, and help with evaluating a student’s work.7 In a recent Christianity Today article, Nicholas Carr noted that when machinery becomes involved in creating content – when the network performs the “editorial function of choosing which pieces of content which people will see … you have to start to wonder about the motivations of the people in the companies operating the networks, because suddenly they’re in positions of enormous power over everyone who is going onto these systems to socialize, to fnd information, to be entertained, to read, or to worship.”8

What Changes for the Student?

The following attempts to chronicle in broad strokes some of the possibilities regarding the ways artifcial intelligence is projected to alter the learning experience for the student.

• Personalization – Presentations that are adjusted according to the unique needs of the learner.

• Real-time feedback – Rather than waiting on grading, a bot can generate immediate feedback to most student input.

• Dynamic adjustment – Artifcial intelligence can assess level of diffculty and automatically adjust tasks/questions based on a learners ongoing performance.

• Data-driven insights – Software is already available for collecting data on learner’s interactions utilizing this to inform the learning path;

hence, continuous data collection and analysis can dynamically inform and guide next steps in a learning process.

• Increased engagement and motivation – Illustrations within the same presentation can be customized to appeal to an athlete, a science Geek, or a business minded student.

• Effciency in learning – Material that a student has already mastered can be omitted from readings or assignments.

• Scalability – the same instructor can cater to a large number of students simultaneously while still maintaining personalized learning experience.9

How Might it Affect Work in the Academy?

Playing off these advances, we can begin to speculate on how artifcial intelligence may change the nature of work in the academy for those who teach and administrate programs. In our discussion of these probabilities at the colloquium, it became apparent that none of what follows are value neutral advances; each is worthy of ample discernment to determine if these contribute to the spiritual formation and virtue of students and professors.

The acceleration of research workfow

Most in the academy have spent hours exercising care and seeking to develop expertise in fnding the best “key words” to rummage through data banks, reading abstracts, and marking relevant articles to procure a robust literature. Then comes the tedious process of copying and storing the articles as themes are identifed from collated articles until organizing concepts begin to emerge. With the availability of natural language processing, interfacing with a search engine becomes increasingly conversational, and machines become increasingly adept at discerning and extending what is being searched for. Furthermore, artifcial intelligence can search vastly more information and generate almost instantaneously what used to require months via a cumbersome literature review. AI applications can be engineered to suggest ways one might go deeper in a particular area of investigation or identify other luminaries in the feld. Other apps might

be calibrated to the particular requirements for a professional journal and create an evaluative mechanism to determine “publication readiness.”10

Already mentioned is the capacity for artifcial intelligence to generate syllabi, lesson plans, sample tests, and rubrics. Taking this a step further, multi-modal data banks are now being developed that integrate text with images with sounds and with audio.11 Hence, the generation of all these materials for teaching could incorporate music, sound effects, and video. With such capability, papers and tests may soon become obsolete as the best proxies for determining competence, giving way to simulation of real life situations.12 For example, I asked ChatGPT to generate simulation ideas for a class on missions. Included among the feedback was a disaster relief simulation, management of a refugee camp, business market analysis for a non-proft, and a spacewalk. (No doubt confating information on the “mission to space” with the kind of missiological implications I was aiming for…but hey, who wouldn’t want to be the frst chaplain on Mars for the Space Force?) With capacity to scan vast archives of knowledge and identify connections between felds of inquiry, artifcial intelligence will no doubt encourage areas of interdisciplinarity and global collaboration. Virtual laboratories will permeate many felds advancing knowledge and skill building in exciting ventures.

The academic workfow for students is similarly increasing, augmented by artifcial intelligence that can move randomized thoughts and unformed outlines into written drafts. Those who labor with proper grammatical construction or English translation can fnd software that auto-completes sentences. Enhanced voice recognition software now can provide summaries of class conversations or generate study notes (fashcards). Chat bots can serve as a reading assistant, asks questions to test one’s comprehension or create a task that helps a student think more critically about a given body of knowledge. Much to the delight of many, software can now generate citations prompted with the simplest of source identifcation.13

Ethical Issues and Other Concerns

Where some are enticed by the possibilities of artifcial intelligence, others are more precautionary, citing hazards or projecting possible deleterious outcomes. The following are some of the known challenges that frst accompanied the prevalent use of AI.14

Plagiarism - the most prominent concern of educators, regulating what is and what is not original thought will almost inevitably become increasingly nuanced and more diffcult to detect. State educational systems are experimenting with creating codes of conduct and/or categorizing graduated levels of prohibition (red, yellow, green). With the need for ongoing modifcation of regulations, educators are likely to lobby for at least a minimal level of scrutiny such as students self-disclosing how AI is being used.

Copyright infringement – At the time when this article was being written, courts were still deliberating on a class action lawsuit regarding whether large databases infringed on the rights of authors and artists via incorporating their work without permission into their vast storage of information.15

Hallucinations and false reporting – Many of those wary of AI will recount an experience where a search generated false information suggesting a book that did not exist, citing a historical artifact, fnding a reference that was fabricated, or providing misinformation about a particular topic. Some examples that made interesting news stories included a headline that Elon Musk had been in a Telsa car crash (made possible by the algorithm linking key words/concepts together), or a more comprehensive search of legal briefs that allegedly generated legal precedents later judged to be incorrect from between 69-88% of the time (in the use of early large language models ChatGPT 3.5 and Llama 2).16 Critics of AI will now cite such examples as precautionary tales urging the limited and discriminate use of AI. Proponents of AI will hasten to add that algorithms themselves can be created to check and self-correct such falsehoods, eventuating in increasingly accurate and helpful outcomes.

Bias – One particularly interesting area of bias relates to the use of facial recognition software and what it might be used to detect. If employed for the purpose of discerning negative emotions or the tendency toward a particular disposition, how likely is it that more negative emotions get associated with a particular race?17 Given the possibility for such bias, what might be the implication if this kind of artifcial intelligent was utilized in the criminal justice system to detect guilt or to indicate proclivities toward criminal behavior? What if banks or insurance companies employed it

to determine who qualifes for a loan or insurance? What if it was used to assist in diagnosis within a hospital to help triage who gets priority for medical care?

Deepfakes – Most of what has been discussed so far are unintentional outcomes of AI indicating gaps in the internal workings of algorithms. (One of the more elaborate examples was a case in which ChatGPT allegedly invented a sexual harassment scandal AND made up a Washington Post article to help substantiate the claim.)18 But there are also intentional and nefarious uses of AI that also have to be taken into consideration such as nudifcation technology. These types of cases have led to various attempts to regulate AI. For example, the FCC has endeavored to fne companies who use AI sounds in political ads.19

Privacy Concerns – Brian Johnson, a cybersecurity expert, was asked on a Breakpoint podcast, “how can you protect yourself in an AI world?” The question emerges in part because any user assessing Open AI themselves become a source of data. Johnson’s judgment was that ultimately a person can’t fully protect themselves. The bigger issue for him however is a question of identity (protecting what is “mine”) and developing methods like opt out features or utilizing a separate account when assessing AI.20

Governance challenges – In November of 2023, Bletchley reported that 28 countries signed a declaration creating a collective commitment to manage the potential risk of frontier AI.21 Ian Bremmer and others have predicted however that the pace at which AI is developing will outpace our capacity to regulate it.22

Power Grid – In early 2024 it required about $40 million/month to process inquiries on Open AI. At that time it was estimated that this represented about 1% of all energy consumption, but that in some locales it could consume as much as 20% of the power gird.23 As AI rapidly expands requiring large infrastructure and the necessity of more nuclear power points, the speculation is that companies will seek contracts with governments to ensure they can run their AI platforms. Note the spectacle shortly after Trump’s election of several tycoons pledging $500 billion dollars to aid in building America’s infrastructure for AI to keep us competitive with other superpowers.24

Inequity Divide – It is estimated that 2.6 billion people (approximately one third of the world’s population) was without access to internet as late as last year. This divide between those who have access and those who don’t will no doubt increase with AI.25 Furthermore, even if most of the world could gain access, it is highly unlikely that most of what they would fnd would exist with their needs or interests in mind.

Defning Artifcial Intelligence

Perhaps it is helpful at this point to take a deeper dive into explaining the emergence of artifcial intelligence, offer more nuanced descriptions between what is currently emerging, and what remains speculative but is the subject of many dystopian projections. Artifcial intelligence created a tsunami of interest when several things converged:

High power computing + Algorithms and software models + Big data collectors26

To give some indication of the expansive power of this convergence, consider the following. One gigabyte of data has been estimated to equate with about 178 million words that can be stored from books, articles, and conversations. One Terabyte is the equivalent of about a trillion bytes of data. The frst version of ChatGPT was estimated as using about 45 terabytes of data.27 Or to say it more simply a terabyte of data is about 175 billion parameters – multiply this by about 50 and you get the pilot version of Chatbot, which by the time you read this article is likely already obsolete by the models that exceed it.

The functions of ChatGPT, which most users are gaining familiarity with, searches sequences of data (primarily text based) and considers the context and relationship of words with every word surrounding it. As a huge computer system develops a comprehensive understanding of this vast data bank, it can then generate the capacity to predict the next word creating what is to humans a coherent thought. The method by which a computer is acting on this data is called an algorithm, and how an algorithm functions is determine by its creator.

However, with the convergence of power computing, algorithms, and big data collection, additional sources of information are being stored and fused together in what can be delivered to the user. For example, text,

image, sound, audio, and code can all be combined in what some call “data lakehouses”28 where algorithmic operations generate multimodal capabilities in how computers perform. In one illustration, a user took a picture of an exotic meal she hoped she could cook for anticipated guests and wondered how AI could help. Consider what might ensue as a computational system receives an image of a luxury meal, receives a verbal instruction, searches recipes to best determine what goes into such a meal, generates a grocery list and formulates a vocalized instructional guide on how to prepare such a meal.29 Note in this illustration how a computer system is able to perform multiple task that normally require human capacities – visual perception, speech recognition, some form of decision-making, and translating input to textual output. This helps us bridge to various kinds of intelligence that are relevant in discussion of artifcial intelligence today. Seriating various defnitions provides a helpful comparison:

Variations of Intelligence:

• Human Intelligence –Ability to “learn, reason and solve problems across a wide range of domains…”30

• Artifcial Intelligence – Programming a machine to accomplish (a) task(s) that involve(s) interaction with its environment, like simulating behavior or thoughts.

• Generative Artifcial Intelligence – Intelligence exhibited by a machine system that generates new audio, image, or text from previously imputed data.

• Machine Learning - Algorithmic operations that enable machines to operate on general procedures for solving a whole class of problems – e.g. a decision tree. By automating an analytical model via reinforcement learning (e.g. right decisions are retained, wrong decisions are corrected), a computer improves performance based on receiving more data. This enables the possibility of fnding hidden insights or patterns that were not pre-programmed, hence “unsupervised learning.”

• Deep Learning/Neural Networks – A subset of machine learning31 that uses layered algorithms inspired by and mimicking biological networks of neurons in the human brain. Hence, artifcial neural networks are programmed to perform complex operations including allowing the system to derive its own algorithm and evaluate its own conclusions.

• Artifcial generative intelligence – Hypothetical future development whereby machines could perform any human intellectual and conceivably supersede humans as they become sentient (see the subsequent article for a deeper dive into comparative intelligences).

In the last several decades, the capacity of machines to imitate human intelligence was gaged by the Turing Test.32 In its original conceptualization questions would be asked to both a person and a machine without knowing which answers came from which. These could include open-ended questions, opinions about climate change, emotional questions about something you long for, or hypothetical questions like “if you were a museum curator what artifacts would you set on display?” Whenever a person could no longer distinguish between which answers came from a human and which answers came from a machine – the machine was regarded as having passed the Turing Test. One simple use of the Turing Test are CAPTCHAs that intend to present a task that is relatively easy for humans but impossible for bots, like identifying wavy, distorted letters to gain access to a website or from a matrix of nine images which ones contain a motorcycle.33

Most pundits or artifcial intelligence would note that a signifcant gap remains between human intelligence and robotic intelligence, but many also see this relationship asymptotically. With deep learning and more complex neural networks, might we think about computers having emerging capacities much like human functions?34 Is it legitimate for us to now talk about robots possessing recall or memory – i.e. scanning through any recorded conversation or document and pulling from it a desired artifact. Having the capability of decision trees operating at hyper speed to train a system to continually improve its output, might we also talk about a computer as “learning” and/or gaining imagination? With facial recognition, software and haptics that can allow sensibility to touch and temperature, how closely can a robot mimic human emotion. Before trying to answer this

question, google “Ameca” and see how the world’s most sophisticated robot functions have stunned people with its anthropomorphic capabilities.35

Further, since there are ways that computers can already supersede humans in some areas of intelligence - for example beating a master chess player, performing quicker and more accurate mathematical computations, recalling more memory from massive data sets, recognizing patterns, etc. –robots will soon outperform humans on many tasks potentially displacing them in the workforce. By some estimates, as high as 70% of our everyday work tasks will be automated as early as 2026.36 The World Economic Forum in their 2025 future jobs report estimate a structural transformation of the workforce affecting 22% of workers, yet hopefully creating more new job roles than are eliminated.37 Recognizing the comprehensive impact such a huge displacement of workers may have globally, the Wall Street Journal reported Pope Leo intentionally chose his papal name in large part because of his desire to address artifcial intelligence as a signature issue of his papacy. Historically, Leo was noted for his protection of factory workers in light of industrial barons who were regarded as threatening their dignity and labor rights. Hence, AI is being regarded by the new Pope as a primary social justice issue of the day. Allegedly, tech leaders have been active in conversations with the Vatican, recognizing a need to sway moral opinion in favor of the technological advances they hope to promote.38

There are other ways that artifcial intelligence is emerging and taking on human characteristics that will be important to follow in the years to come. Here are a few things to peruse, though by the time this article is published many of these may already be common or ousted by even newer technologies.

Disappearing Technology

Imran Chaudhri offered a TED talk on what he termed “disappearing tech.”39 Chaudhri frst traces the evolution of computer systems, once housed in large building spaces, becoming small enough to embed in laptops. As the power of computing increases, the size of the devices that house decreases. Hence, we now have iPhones and even smart watches with ten times the computing power that it took to launch the frst rocket to the moon. Recent years have seen the availability of artifcial intelligence in the form of virtual reality headsets created with transparent screens so gamers would not be as deprived of social interaction while playing. Chaudrhi presents the harbinger of “invisible tech,” that is mostly

invisible to others, coming in the form of a decorative pin one might affx to clothing. Invisible tech would not require one to resign themselves to an offce space, tapping on a mouse or swiping on an app. This form of screenless AI intends to interact with the world in the same way humans interact with the world – hearing all that we hear, seeing all that we see, and providing a multi-modal interface with our immediate context. Screenless, seamless, and sensing, one could be riding a bicycle while simultaneously summoning AI to sort through emails, prioritize them and offer a response even using your voice in its dictation.

From an Attention to a Relational Economy

Brian Johnson in a Breakpoint podcast extrapolates from the way smartphones are used in an “attention economy” to the way chatbots and robots may be used in a “relational economy.”40 The attention economy suggests an ecosystem where companies proft by capturing and monetizing our focus. People’s attention is regarded as a scarce and highly desirable resource that companies and organizations compete over to capture and maintain. Steve Jobs was masterful in the creation of the smartphone designing it with psychological mechanisms that capture and maintain our attention – e.g. touch screens, notifcations, illuminating displays, pop-up menus, etc. - all of which provide small dopamine reinforcements that keep us glued to our screens. Initially, we are enamored with the ease of access and immense world of information it opens to us. Yet, a decade later we seem to be awakening not only to its benefts but also to the mental health challenges and opportunity costs lost via our inundation in a digital world.

Artifcial intelligence however will operate increasingly in a relational economy. In relationship economics, benefts accrue when value is created by personalizing a response and fostering the quality of a relationship and loyalty that follows. Since AI can tailor a response to user behavior; provide 24/7 availability via virtual assistants; segment a customer base for more targeted marketing; use voice analytics to gauge customer satisfaction, and increasingly simulate personal interaction, its use is inevitably exponential. AI in a relational economy will move beyond seeking to capture attention to stimulating companionship and outsourcing intimacy. Empathy, advice and affection can be offered on demand though relational automation. It is a daunting question to ponder how many daily relational exchanges between people could be replaced by interacting with a robot. Following the pandemic, we have already become increasingly

deeply invested in education, therapy, medical visits, banking, dating, and even worship occurring in digital spaces. Yet, most of these exchanges are under our control, requiring little vulnerability – frictionless relationships that do not require us to develop the skills of mutuality. What might be the cost socially, emotionally, and psychologically as more people interactions are displaced by robots? What happens when we imbue artifcial intelligence with our trust and come to rely on it for more of our functioning and wellbeing? Speaking what now seems prophetically at the World Summit AI in 2022, Ian McGilchrist cautioned, “As machines gradually displace people, what happens to human fourishing?... what makes life worth living can only be called resonance: the encounter with other living beings, the natural world, …. with the cosmos at large, or with God. If we are not to become ever more diminished as human beings, we need to remain in control of machines, not come under their control…”41

Neurotechnology

Neuralink is a neurotechnology company co-founded by Elon Musk that is seeking to help people with paralysis gain capacities via their thoughts directing prosthetics. Beginning in 2024 clinical trials have begun with “brain computer interfaces” (BCI) that are surgically implanted into a person’s cerebral cortex.42 Fine threads with electrodes record and transmit brain signals that wirelessly connect to external devices, enabling those otherwise paralyzed to speak or move prosthetic limbs. Nueralink envisons that BCI’s could eventually restore cognitive, motor, sensory, and visual function as well as contribute to the remediation of neurological disorders. The capability of triggering movement with a thought through this process is remarkable, the possibilities literally “mind-boggling.” If a BCI can stimulate or turn off or control the speed of neurotransmission, what uses might there be to infuence depression or anxiety? But ethical questions emerge that are equally concerning: Given this process - is the bot actually reading a person’s thoughts? If it is reading a person’s thoughts and has the capacity to function autonomously– is it gaining consciousness? If such implants are extended, what possibilities are there for hybridizing humanity with machines? What then does it mean to be human?

Transhumanism

This takes us to a brief exploration of transhumanism defned by several as “the intellectual and cultural movement that affrms the

possibility and desirability of fundamentally improving the human condition through applied reason, especially by developing and making widely available technologies to eliminate aging and to greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities.”43 Transhumanism envisions the upgrading of the human being through biotechnology and genetic engineering, predicting that in the not so distant future, a new species could emerge. John Lennox however, regards this as a new form of Gnosticism, seeing it as one more attempt to free humans from our bodies via technology.44 Lennox interacts with one proponent of this perspective - Yuvall Noah Harari as Harari address what he regards as three primary longings of humanity: bliss, immortality, and Divinity asking “what if we could achieve all three?”45

“Humans don’t die because God decreed it or because mortality is an essential part of some great cosmic plan. Humans always die due to some technical glitch…Every technical problem has a technical solution. We don’t need to wait for the Second Coming in order to overcome death.”

“The great project of the twenty-frst century will be in the pursuit of attaining global happiness, to get there ‘will involve re-engineering Homo Sapiens so they can enjoy everlasting pleasure.’” “Having raised humanity above the beastly level of survival struggles, we will now aim to upgrade humans into gods, turning Homo Sapiens into Homo Deus.”46

Nikolai Federov a Russian Orthodox philosopher writing in the same vein suggests that humans could intervene in their own evolution and direct it toward physical immortality and even resurrection. “This day will be divine, awesome, but not miraculous, for resurrection will be a task not of miracle but of knowledge and common labor.”47

Given our witness to the Christian faith, the stakes could hardly be higher!

End Notes:

1 Cf. a Barna report titled Hesitant and Hopeful: How Different Generations View Artifcial Intelligence, https://www.barna.com/research/ generations-ai/?utm_source=chatgpt.com, January 24, 2024.

2 “Christians Are Asking ChatGPT About God. Is This Different From Googling?” https://www.christianitytoday.com/2023/05/chatgptgoogle-bible-theology-artifcial-intelligence-truth/?utm_source=chatgpt. com.

3 Many of the ideas in this paragraph originated from watching a Ted Talk from Sal Khan posted in April 2023 titled “How AI could save (not destroy) education”. https://www.ted.com/talks/sal_khan_how_ai_could_ save_not_destroy_education.

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6TUPW9C454.

5 Many of these ideas also originate from a product resource databank that Ithaka S+R was offering March 7, 2024, under the title “Generative AI in Higher Education: The Product Landscape”.

6 Sal Khan, ibid.

7 Much of the progression I offer here originates from a presentation titled “Reimagining Course Creation: The Adaptive Intelligent Design Model and Generative AI” given by Mike McKay and Dr. Michelle Meadows at the Feb 2024 annual conference of the International Technological Council, Las Vegas, Nevada.

8 Interview with Nicholas Carr in Christianity Today, Vol 69, 4, July/August 2025, page 25. https://www.christianitytoday.com/2025/07/ nicholas-carr-ai-doctors-internet-edgelords/.

9 Much of what appears in this seriated list was gleaned from AI in Education podcasts hosted by Dan Bowen and Ray Fleming. For example, see their Jan 25, 2024, podcast titled “The Impact of AI on Higher Education: Interviews” Also helpful was an AI Open Forum titled “Constructive Partnerships with Text-based Generative AI” hosted online by the Association of Theological Schools, March 4, 2024, as well as the presentation cited above in footnote 7 from McKay and Meadows presentation.

10 Ithaka S+R, Ibid. Much of the ideas posed here were gleaned from descriptions of available products in the Ithaka resource bank. See footnote 5 above.

11 This information came from an episode of 60 Minutes on “Artifcial Intelligence” that aired on Jan 13, 2019 – https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=aZ5EsdnpLMI. Since then, 60 Minutes has aired several more episodes focused on more recent developments in AI. The MIT Technology Review was also helpful in understanding multi-modal AI and data lakehouses - https://www.technologyreview.com/topic/artifcialintelligence/.

12 I became persuaded toward this shift in assessing students when reading The Chronicle of Higher Education’s publication titled Big Bot on Campus: The perils and potential of ChatGPT and other AI, 2023.

13 See many of the footnotes already listed to fnd examples, especially the Sal Khan Ted Talk in footnote 3.

14 Of great help in compiling this list was a TedTalk given by Gary Marcus on May 12, 2023, titled “The Urgent Risks of AI and What to Do

About Them” Specifcation of what Marcus named comes from assorted news stories heard throughout the preparation for the colloquium collated from sources like NPR, CNN, Fox News, etc. and from news magazines like Time Where it might prove helpful, I have further identifed specifc sources in the seriated list. What is most interesting to note is how infrequently these are now reported, indicating what appears to be a signifcant capacity for AI to either self-correct or be engineered with increasing accuracy.

15 https://authorsguild.org/news/ag-and-authors-fle-class-actionsuit-against-openai/.

16 Dahl, Matthew; Magesh, Varun; Suzgun, Mirac & Ho, Daniel E. Large Legal Fictions: Profling Legal Hallucinations in Large Language Models, 16 Journal of Legal Analysis 64 (2024).

17 This report is attributed to Privacy International under a case study titled “Emotionreading facial recognition displays racial bias” reported August 12, 2019. https://www.privacyinternational.org/es/advanced-search ?keywords=&f%5B0%5D=content_type_term%3AEducational&page=28.

18 https://www.foxnews.com/media/chatgpt-falsely-accusesjonathan-turley-sexual-harassment-concocts-fake-wapo-story-supportallegation.

19 https://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/fcc-cracks-down-on-aipowered-robocalls.

20 Brian Johnson and Abdu Murray are interviewed by Pete Marra on Feb 27, 2024 on a podcast titled “The Promise and Perils of Artifcial Intelligence” - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kC-qUfrgbf8.

21 See the Bletchely Declaration policy paper updated Feb 13, 2025 at https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/foreign-commonwealthdevelopment-offce.

22 Bremmer, Ian. “The Top Risks of 2024, ” Time magazine, Jan 22, 2024, page 28.

23 Find these stats embedded in a full report from The MIT Technology Review titled “The Great Acceleration: CIO Perspectives on Generative AI,” July 18, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/07/18/1076423/ the-great-acceleration-cio-perspectives-on-generative-ai/.

24 https://www.forbes.com/sites/moorinsights/2025/01/30/thestargate-project-trump-touts-500-billion-bid-for-ai-dominance/.

25 See for example that article from Schellekins, Phillip and Skilling, David, “Three Reasons Why AI May Widen Global Inequality, ” Oct 17, 2024. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/three-reasons-why-ai-maywiden-global-inequality.

(2025)

26 The previous footnote indicated a podcast that was later commented on in weekly review podcast co-authored by Timothy Padgett. Padgett interviewed Ray Kurzwell in an episode also titled “The Promise and Perils of Artifcial Intelligence,” Feb 23,2024.

27 https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/chatgpt.

28 MIT Technology Review, ibid.

29 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4o5mekBoWOk.

30 This defnition and the some of the subsequent categorization began with an article titled “Human or AI?: The Nuances of Intelligence” from Amelia Haynes, research manager for Korn Ferry in 2024.

31 Mckay and Meadows, Reimagining Course Creation, ibid. See footnote 7 above as another helpful resource in creating these defnitions and categories.

32 The Turing test is mentioned in many historic looks at AI. See one example in this Ted Talk from Greg Brockman titled “The Inside Story of ChatGPT’s Astonishing Potential,” April 20, 2023.

33 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CAPTCHA.

34 See further the 60 Minutes episode cited in footnote 11 above.

35 https://engineeredarts.com/robot/ameca/.

36 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Otim2mDjsYM&t=5s.

37 https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobsreport-2025/.

38 https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/pope-leo-ai-tech-771cca48?utm_ source=chatgpt.com.

39 https://www.ted.com/talks/imran_chaudhri_the_disappearing_ computer_and_a_world_where_you_can_take_ai_everywhere.

40 Brian Johnson and Abdu Murray are interviewed by Pete Marra on Feb 27, 2024 on a podcast titled “The Promise and Perils of Artifcial Intelligence” - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kC-qUfrgbf8.

41 For a full recording of McGilchrist’s brilliant presentation see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgbUCKWCMPA.

42 See the technology tab at https://neuralink.com/.

43 This defnition is used for example by Nick Bostrom, “A History of Transhumanist Thought,” in the Journal of Evolution and Technology, 14 (1): 1-25.

44 Lennox, John, 2084 and the AI Revolution, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2024.

45 This aspect of Harari’s ideology was reviewed by Bill Gates on May 22, 2017, on a Gates Notes page titled “What if people run out of things to do?” - https://www.gatesnotes.com/homo-deus.

46 Harari, Yuvall N., Homo Deus: A History of Tomorrow, HarperCollins, 2017.

47 This quote can be found in the Lennox book cited in footnote 44, 167.

The Asbury Journal 80/2: 326-370

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.02.2025F.03

Aaron J. Lewis

The Giants Cry “Halt”: Incongruencies between Classical Virtue Ethics and Generative Artifcial Intelligence

Abstract:

Due to recent advancements in the feld of Artifcial Intelligence, the near future of technological growth is estimated to be one of the most transformative periods in human history. Virtue ethics is arguably the superior ethical framework for integrating advanced technologies into the life of the common person. However, the philosophy undergirding much of classical virtue ethics—as espoused by Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas— makes apparent several incongruencies between Classical Virtue Ethics and Generative Artifcial Intelligence. These incongruencies must be identifed for the sustainment of future conditions in which moral virtue can be fostered. For those who recognize the limitations of human nature and acknowledge the importance of human fourishing, this topic is of increasing concern.

Key Words: virtue ethics, artifcial intelligence, Aristotle, Aquinas, agency, human nature

Aaron J. Lewis graduated from Purdue University in 2014 with a B.S. in Engineering. Over the next six years, he worked within the domains of biomedical technology and manufacturing engineering. From 2020-2025, he attended Asbury Theological Seminary, graduating with an M.A. in Theological Studies and a Th.M. focused on Philosophy. He now studies further graduate philosophy at Western Michigan University and serves as a teaching assistant.

“You can not have the power of gods without the love, wisdom, and prudence of gods.”1

Introduction

Humanity is sailing into uncharted and futuristic waters that will require ancient truths to navigate. In these waters, our foresight into the ramifcations of ethical choice, personal moral formation, and action may be obscured by the rate of change in a world augmented by artifcial intelligence. For those concerned about human fourishing, this issue is of paramount importance. Advancements in the felds of artifcial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have birthed new families of generalpurpose technologies. These technologies may prove more transformative than fre, the wheel, the engine, the personal computer, and the splitting of the atom. With suffcient architecture, training data, and computational power, AI and ML may one day solve humanity’s most diffcult problems with ease. On the other hand—and a heavy hand it is—AI may enable new expressions of dark desire and create irreversible consequences at both the individual and societal level. The cure for cancer and the origin of yet-tobe-named psychological disorders could be borne from the same source. For some, the future seems a utopian dream; for others, it is an existential nightmare. A new technological and ethical landscape is becoming manifest, and each person must decide their moral aim: virtue or vice.

As we approach this future, virtue ethics is arguably the most promising ethical framework for properly integrating advanced technologies into the life of the common person. Some philosophers of technology, such as Shannon Vallor, argue that, within this integration, the moral calculus of utility is untenable and the techno-social paradigm shifts are too frequent for a fully adequate deontology. As Vallor says, “Virtue ethics is ideally suited for adaptation to the open-ended and varied encounters with particular technologies that will shape the human condition in this and coming centuries.”2 Even still, more needs said on this issue—and that is the purpose of this paper. While virtue ethics offers superior guidance amidst technological change, the philosophy supporting classical virtue ethics has much to say against the specifc technology of Generative AI (GenAI). It should be noted that some approaches to virtue ethics and GenAI might attempt to show how AI can be used virtuously or positively infuence human cultural evolution.3 However, the current approach considers why we should be cautious. At a high level, AI creates two problems. One

problem is that the manner and degree in which agency is relinquished will disrupt how virtue is cultivated. The other problem pertains to how AI operates in a manner and speed that is incongruent with the principles of virtue ethics and fourishing respective of human nature. We can observe these general issues in the following, particularized arguments:

1a. GenAI often replaces human agency and means of habituation, disrupting the causes of virtue (with respect to how the technology is applied and integrated).

1b. Virtue requires a human agent to make rational and ethical measurement, progressively understood through experience, prior action, and moral knowledge about particular facts. AI may dispossess human measurement, resultant action, and growth related to relinquished tasks.

2a. Virtue is antithetical to vice. The “accessible domains of vice” are and will be inordinately amplifed by AI, likely disrupting prudential foresight and temperate balance of many users through temptation and access to vice.

2b. The current state of AI and future state of AGI create totalizing conditions in which “prudential measurement of the current state” and “teleological view of a future state” cannot be articulated due to: (1) The combination of democratized AI and the epistemic gap between userintentions and AI-production and (2) the compounding of exponential growth and operating speed of systems. (This epistemic gap is qualifed by four phenomena in the feld of AI: emergent properties, the black box problem, asymmetric direction of ft, and AI hallucinations.)

Note that throughout this paper there are two related yet philosophically distinct approaches by which the incongruencies between AI and virtue are analyzed. The frst approach recognizes the conditions in which an individual maintains agency and cultivates virtue (1a, 1b). The second

approach recognizes the way in which society breeds conditions in which virtue can or cannot be cultivated (2a, 2b). As AI is propagated across the ethical landscape, issues will appear at both individual and societal levels of analysis.

In developing an explanation for why these ostensible issues loom, a comprehensive survey of the history and kinds of virtue ethics is beyond the scope of this paper. Therefore, two giants of the Western virtue tradition have been selected to represent the whole: Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. Key aspects of the above arguments are treated in four following sections. First (I), we will briefy review relevant portions of Nicomachean Ethics. Second (II), we will address the Summa Theologica and a philosophical synthesis of the Aristotelian and Thomistic accounts of virtue. These two sections focus on the virtues of prudence (phronésis) and temperance (sôphrosune). These virtues make the most effcient and plausible case for each argument. Third (III), is a review of GenAI, highlighting general knowledge, notable breakthroughs, applications, and trajectories. Fourth (IV) we return to Aquinas and detail a theory of agency so that AI-users may be cognizant of the precise location of agency being exercised or relinquished. Section four is the largest because agency is highly nuanced, central to the cultivation of many virtues, and relevant to each particularized argument in section fve. Fifth (V), we will address the particularized arguments above. In result, this paper will demonstrate a totalizing case: those who strive to be virtuous and live in a virtuous society should be both cautious and selective when integrating and applying many technologies within the genus of GenAI.

The reader should note—and will progressively understand— three areas of supporting material. One area is Aristotle’s theory of causality (The Four Causes) and its applied relationship to his own theory of virtue, as relayed by Aquinas and others.4 The causal account of virtue aids in conceptually “giving name” to the components of virtue that are dispossessed by AI. The second area is the Aristotelian and Thomistic understanding of human agency as it relates to virtue.5 For Aristotle, an agent is anything that can act or create force (e.g. a storm, animal, or computer) but only within the bounds of its nature.6 A human agent is composed of rational deliberations of circumstance and means, moral intentions, choice, and respective actions toward a desired end.7 The defning characteristics of a human agent are both moral and rational activity. In the Middle Ages, Aquinas detailed this activity and formulated the theory of agency applied

(2025)

in section four. A fnal area of focus is the following framework, which we can call the “framework of virtue,” that represents the modalities of virtue as a concept, action, and process:

Start/ Ask-

Rational and Ethical - Action - Final/ Answer Measurement

Virtuous Habituation

This framework, on which more will be later said, visually represents the general principles of virtue cultivation seen within the classical tradition. The argumentation related to this framework is intended to be general yet robust, enabling it to stand alongside (or within) several articulations of virtue ethics.8 Last, the moral and philosophical position of this work claims that all people can achieve the classical virtues. The rise of AI will affect all, and virtue is our best universal response.

(I) A Summary of Aristotelian Virtue Theory

Throughout history, some form of virtue ethics is refected in many traditions, such as Christian and Confucian. The earliest expressions of virtue most notably come from Greek antiquity. Plato, of course, gave us four classical virtues: prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. While Aristotle developed a larger set of virtues that he considered human excellences, these classical virtues remained a centerpiece of Aristotle’s virtue theory. Four relevant aspects of Aristotle’s concept of a virtue are as follows. First, virtue is a type of excellence relative to a human’s nature and end (telos). Second, virtue relates to the character of an agent, either intellectually or morally. Third, virtue is determined by principle (reason, intellect) and knowledge gained through experience. Fourth, virtue has to do with a matter of choice, specifcally moral choice. This moral choice often falls between the defciency or excess of a particular intellectual or moral state of being.9 One such example is courage as the proper choice between cowardice and foolishness. Within Aristotelian thought, (most) virtues have a relative “mean” between some excess and a respective defciency. Aristotle says:

Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean, the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the man of practical wisdom (phronésis) would determine it … it is a mean because the vices respectively fall short of or exceed what is right in both passions and actions, while virtue both fnds and chooses that which is intermediate.10

This is Aristotle’s well-known doctrine of the mean. Many modern philosophers rightfully debate advanced articulations of the “mean,” the “rational principle,” and their respective functions. For our purposes, the reader should simply note that a virtue is a state of character defned by an agent’s reasoning, moral choices, and actions, iteratively selected by that agent from a purview of what is known by rational principle and practical wisdom (phronésis, prudence).

Virtue can be understood as an iterative process directed at fourishing (eudaimonia). This process is qualifed by selecting that which is excellent, acting upon it, and moving toward an improved state of being. Virtue cultivation is inherently different for each person because choice is relative to personal nature (e.g. a person with social anxiety may display incredible courage in a simple act of conversation). For some virtues, the mean is not found at the midpoint between excess and defciency. Courage may be closer to foolishness than cowardice and cowardice may come more easily for some people. In acquiring virtue, experiential knowledge plays a central role. Aristotle points out that, when making decisions, a mature man is more prudent and temperate than a child, even if both the man and the child aim at the same good.11 The man simply has greater experience, and therefore, greater knowledge in applying morals and reason to a given landscape of choices. Furthermore, virtue is not solely concerned with what a person is doing, but also with what they ought to do. This “doing” reinforces in the actor as a type of practical knowledge, which in turn iteratively makes the actor more virtuous or vicious in character. This iterative process and resultant growth is termed here as virtuous habituation.

The central acts of virtue—rational deliberation and moral choice—are demanding for a simple reason. “Men are good in but one way, but bad in many,” says Aristotle.12 This statement seems to be a general truth in life, whether in pleasing a parent or solving a math problem. Simply, there are many ways to do something wrong and only a select few ways to do that same thing correctly. Therefore, as the level of consequence increases

for any action, the associated deliberations and moral choice become increasingly paramount. This point will be relevant to our discussion on AI. Moving on from virtue in general, let us consider more specifc and relevant aspects of prudence.

Aristotle articulates some qualities of prudence, namely that a person is not nearsighted, but is rather considerate of holistic wellbeing, what might come about, and what is “advantageous to the virtuous life.”13 By these qualities, prudence is naturally preserved in a person by temperance (sōzousa ten phronēsin).14 Moreover, prudence is concerned with facts, but more specifcally with what ought to be done with certain facts and to what ultimate end (telos) they lead. He says:

Practical wisdom (phronésis) is concerned with the ultimate particular, which is the object not of scientifc knowledge but of perception15… Now all things which have to be done are included among particulars or ultimates; for not only must the man of [prudence] know particular facts, but understanding and judgment are also concerned with things to be done… 16

“Scientifc knowledge,” as Aristotle defnes it in this context, is best understood as what follows from frst principles and knowledge of the immediate facts. This a priori analysis determines an object’s empirical behavior as a result of rationally grasping its form or nature. Prudence, on the other hand, is something not derived in the same manner; it is the perception of the moral end, which is over and above the facts themselves.17 Aristotle’s analysis of factual knowledge and prudence seems apparent, despite heavy debate in the current era. Consider that empirical facts gathered by scientifc inquiry or computational systems say nothing of what ought to be done with those facts. Here, moral knowledge about facts is necessary. As a real-life example demonstrates, scientifc knowledge will readily determine if ebola can be hybridized with smallpox.18 Moral knowledge from a moral agent adjudicates if ebola and smallpox should be hybridized. The virtue of prudence acts as an ethical overseer by navigating the facts of a given situation and providing guidance toward fourishing. For these reasons, Aristotle considers prudence as the cardinal virtue. He says, “Prudence as well as Moral Virtue determines the complete performance of man’s proper function: Virtue ensures the rightness of the end we aim at, Prudence ensures the rightness of the means we adopt to gain that end.”19 For our later discussion, consider that AI is an unprecedented hyper-

accelerant toward some end; lesser time for iterative correction infers that prudential aim is critical. Whether AI is a prudent means in general is an issue of great debate.

Let us transition to the relevant aspects of temperance. For Aristotle, as well as Aquinas in his wake, temperance is usually concerned with pleasures related to sex, food, and drink, or those pleasures and aversions common to most creatures.20 The excesses and defciencies of the temperate mean are quite obvious, yet people are evidently more predisposed to the excesses of self-indulgence.21 While Aristotle almost exclusively focuses on the sensory aspects of temperance, there are certainly higher-order pleasures unique to humankind beyond base gluttony and lust—such as power, luxury, fame, domination, and control—to which the same model of thinking can be applied. Moreover, Aristotle notes that there are “pleasures peculiar to individuals.”22 The more peculiar a pleasure is, likely, the more pernicious it is. He states that when peculiar pleasures go wrong, they “go wrong in many ways.”23 This insight is highly relevant to the imagery (or general sensory) branch of GenAI, where “peculiar” appetites have quite literally no limitation in quantity or precision. The endless panoply of surreal, temptatious, and destructive visual content is an already welldocumented issue, feeding perversions and distorting the pleasures toward which humanity is drawn. Inarguably, some pleasures are well beyond proper reason and direct the susceptible away from fourishing. This is why temperance must be in harmony with reason. It is an aid in preserving many other virtues. On the whole, temperance is a type of balance, regulation, and control of one’s mind and body, an act of doing the right thing at the right time.24 Aristotle aptly closes Book III stating,“…the [will] in a temperate man should harmonize with reason… this is what reason directs.”25 Temperance is an essential virtue in a world with an increasing domain of “consumptive” possibilities, yet the ability to obtain temperance is confounded by the nature of what is creating those possibilities. Perhaps what has been said can be understood in an analogy: if a man who struggles to control himself is forced onto a tightrope, the result is predictable. Before moving on to Aquinas and the synthesized account of virtue, let us briefy defne the Aristotelian account of causation (The Four Causes). Aristotle frst argued that all objects have four causes for their existence. The term causes is often best understood as becauses—in other words, the reasons why something has a particular ontology.26,27 They are:

- Formal Cause: the essence of, what it is about, what it is

- Material Cause: that out of which something is made

- Final Cause: the good, telos, or end to which something is moving

- Effcient Cause: where the process of change occurs28

From the Enlightenment through the postmodern era, the formal and fnal causes have been all but gutted by the dominant views of reductionism and materialism. All who believe in moral goodness have no such luxury to abandon these causes as essence and end are primary concerns of ethical and theological thought. For this reason, Aquinas saw the value in Aristotelian causality and employed it in his formulation of virtue. A causal synthesis of Scholastic-Aristotelian virtue will prove useful in “giving name” to the potential incongruencies between AI and moral virtue. Although this causal account is not the only framework of virtue, it is a cogent point of synthesis between the Aristotelian and Thomistic accounts, offering us a unique philosophical viewpoint for the incongruencies between virtue and AI.

(II) A Summary of Thomistic Virtue Theory and a Causal Synthesis

In the Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas sought to unify the theological, philosophical, and ethical thought of the previous two millennia. Furthermore, he advanced the theological virtues: Faith, Charity, and Hope. For Aquinas, virtue ethics (which constitute over a quarter of the Summa)29 is a vital part of religious life. By further integrating natural law into the conception of virtue, Aquinas was able to develop an advanced virtue ethic, grounding virtue in the divine and common moral knowledge. If Aristotle is the trunk of the virtue tradition tree, Aquinas is surely the strongest and most fruitful branch of the Scholastic Era.

In I-II 55.4 of the Summa, Aquinas employs Aristotle’s causalmetaphysics in his formulations, giving keen insight on what constitutes virtue. Aquinas’s formulations imply that if components or causes are removed from a virtue’s constitution, the virtue cannot be obtained. Thomistic scholar Nicholas Austin structures Aquinas’s causal account of virtue in this way:

- Formal Cause: A good quality (habit)

- Material Cause: of the mind

- Final Cause: by which a person lives rightly

- Effcient Cause: which God works in us [or which is acquired by habituation]30,31

Aquinas—recognizing that many virtues are universally accessible— notes that the effcient cause of virtue may be considered without God for common virtues.32 However, this exception will not work for theological virtues as God is the object of theological virtue. Summarizing Aquinas, Nicholas Austin states that what a virtue “is about” designates whether it is a theological or classical virtue.33 This designation is known as its formal object or mode. Theological virtues are about God, while classical virtues are about the right quality and trait; one is infused while the other is acquired by habituation.34

Moreover, Aquinas employs Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean and expounds on it. He generally describes the doctrine as “rule and measure” guiding the human will:

…[concerning virtue,] evil consists in discordance from their rule or measure. Now this may happen either by their exceeding the measure or by their falling short of it; as is clearly the case in all things ruled or measured. Hence it is evident that the good of moral virtue consists in conformity with the rule of reason… Therefore it is evident that moral virtue observes the mean.35

We see once again a classical process of ethical measurement, application of reason, moral choice, and conformity to some mean. Where does this process occur? Aquinas states that the rational principle and virtuous mean are observed in the reasoning of the agent—or “the mean is observed in the act itself of reason.”36 The moral determination then binds the passions to this rational mean. In this way, temperance leads to temperate acts, and prudence leads to prudential acts. So, Aquinas provides this key addition to our thesis: if the mean is observed in the act of reasoning, then, consequently, the act of reasoning must be done by an agent in order for a respective virtue to be obtained for that agent. 37 Note that for many cognitive activities, both personal agency and cognition are being progressively relinquished to AI. In summary of what has been said, several general principles of the Aristotelian and Thomistic accounts have been established, and these principles are further elucidated within a causal account of virtue. Virtue can be broadly accounted for in this way. The formal cause of virtue is the nature of virtue in and of itself. The material cause is the human mind,

including its associated rational deliberations and moral choices. The fnal cause is the quality of character by which a person lives rightly and fourishes. The effcient cause is the process of habituation by which one becomes virtuous. In general, virtue is an act of reasoning, identifying a “mean” to which moral choice binds the passions and actions of an agent. Virtue requires both rational and ethical measurement and therefore conditions in which a human agent can apply these principles and measurements. This framework synthesizes the general principles:

Start/ Ask- Rational and Ethical - s-\ction - Final/ Answer Measurement

Virtuous Habituation

With what has been said in (I) and (II), we have much to consider in the following sections. The cardinal virtue of prudence is not applicable in domains where current circumstance and future states of affairs are fully imperceptible. Virtue in general cannot be enacted or habituated when agents relinquish reasoning, choice, and action to secondary “agents” with unknown rational and moral directives. If and when the material cause of virtue is co-opted, the effcient cause is displaced, the formal cause is distorted, and the fnal cause is unknown, virtue cannot be obtained in any traditional sense that has been established. Now we see what this analysis of virtue has to say about a world augmented by AI.

(III) Overview of Generative Artifcial Intelligence

This section will establish general knowledge of GenAI, including high-level capabilities, standard operations, and how these operations might relate to classical virtue ethics. If virtue is generally understood by the phrase “what you do is what you become,” then all parties should consider what becomes of a human and human society when much of “the doing” is relinquished to technology. It is true, humans are inherently limited; this is why the allures of GenAI are attractive. But again, humans are limited. There is only so much we can handle, only so fast we can grow, only so much pleasure we can experience, and only so far we can see. The reader, if new to the topic of AI and ML, must understand the profound and transformative

power of this new technology. While contemplating sections (III), (IV), and (V), consider AI’s formative impact both at the personal and societal level of analysis. Relating to forthcoming arguments in (IV) and (V), further consider the following terms: technological growth rate, domains of vice, emergent properties, and the incremental replacement of human agency