Roots of Exploitation

To what extent does the nature of colonial networks of material extraction in Myanmar make it possible for a military regime to survive through the weaponization of Teak exports?

Aryan Kaul

DATE | 20 TH FEBRUARY 2024 TUTOR | ALBERT BRENCHAT AGUILAR BARC0134 | HISTORY AND THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE DATE | 20 TH FEBRUARY 2024 TUTOR | ALBERT BRENCHAT AGUILAR BARC0134 | HISTORY AND THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE

In this dissertation, the terms ‘Myanmar’ and ‘British Burma’ are used with specific historical and contextual distinctions in mind. ‘Myanmar’ is employed to refer to the country in the post-colonial era, acknowledging its status as a sovereign nation following its independence from British colonial rule. Conversely, ‘British Burma’ is used to denote the period during which the country was under British colonial administration. This choice of terminology is intended solely for clarity and accuracy in discussing the country’s historical and contemporary contexts. It is not meant to express a political stance or to offend any parties associated with Myanmar. The aim is to respect the complex history and diverse identities of the nation, while providing a clear framework for analysis.

List of Illustrations

Word Count : 5461

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 2 1 Contents Disclaimer Introduction 3 9 21 33 37 39 41 01./ Preserving Royal Forests 02./ A Terraformed Colony 03./ Machines of Empire Conclusion

Bibliography

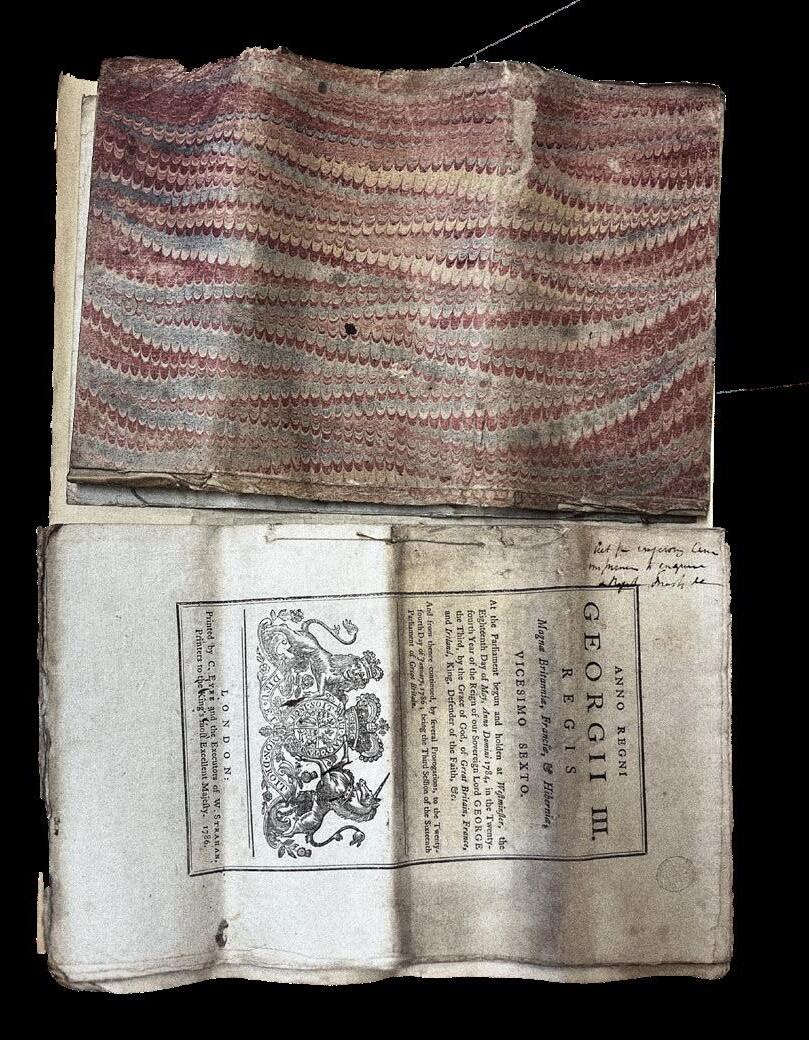

FIGURE 1 (Front Cover)

The texture, pattern and approximate colour of the binding in which the Forest Bill is archived within at the Royal Museums Greenwich.

Source : The Caird Archive

1 Pollard and Robertson, ‘The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914’.

2 Oster, ‘Great Britain in the Age of Sail: Scarce Resources, Ruthless Actions and Consequences’.

“There were few industries in the latter half of the nineteenth century in which Britain was more truly the workshop of the world than in shipbuilding.”

– Pollard and Robertson, 2013, p. 9

Introduction

The Age of Sail commenced in the sixteenth century and concluded in the late nineteenth century. The period is defined by the predominance of sailing ships in naval trade and warfare. Being an island with several sheltered ports proved to be Britain’s most strategically valuable geographical trait during this period. It also had a relatively abundant store of capital; made up a significant fraction of the world’s trade; and was equipped with a technically skilled workforce. To become the “world’s greatest shipbuilding centre” Britain was almost perfect, lacking just one crucial element – an economically feasible supply of the essential raw materials. 1

Procuring these resources was crucial for the protection of the Royal Navy, and by extension – the Empire. Britain found it difficult to sustainably fulfil the material demand using only its domestic resources, therefore it looked to other countries and eventually its colonies for the deficit. The dependence on imports of foreign materials could have proven to be a vulnerability for the state, with Britain having acted with desperation and brutality to secure its first line of defence. 2 Effects of such historic actions are argued to be reflected in material portraits that are now established in contemporary neo-colonial landscapes and explored throughout this dissertation – primarily the concretisation of the military junta established in Myanmar through the weaponization of Teakwood exports.

Jane Hutton’s publication, ‘Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements,’ is recognised as a guiding framework for the research methodology of this dissertation. Each ‘story’ evaluated by Hutton begins by displaying an overarching technical understanding of the need for the resource. As Hutton discloses the source of demand, a reciprocal relationship is manifested between the two distinct resources – sharing only the end product as a point of conformity. 3 The writing is critical of its origins and curious in how it proposes.

3 Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements.

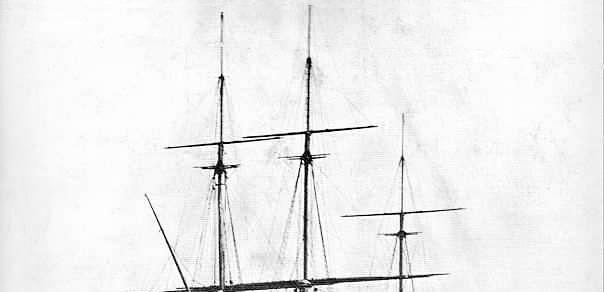

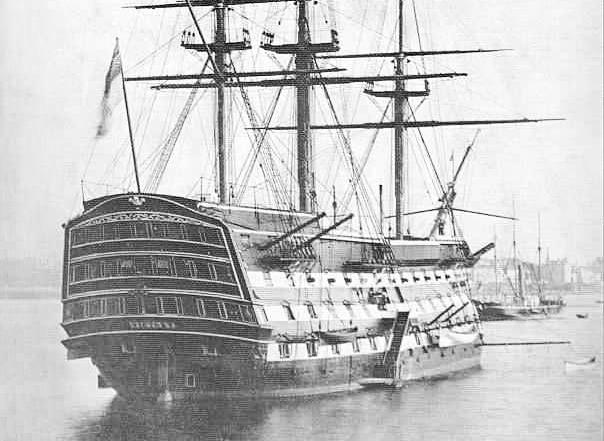

FIGURE 2

HMS Victory

Launched in 1758, the HMS Victory can be see moored in Portsmouth Harbour. She most famously served in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 as Lord Nelson’s flagship. She is now being preserved as a museum ship in Portsmouth. The construction required 6,000 trees of Oak, Elm, Pine and Fir. Some of these parts were later substituted with Teak and other imported hardwoods for better durability.

Source : The National Museum Royal Navy Archive (1884)

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 4

3

The two resources that are affectively analysed in this dissertation are Oak trees from Royal Forests in England, bolstered by a situated perspective of Epping Forest (London), and Teak trees from British Burma – both being demanded for shipbuilding practices by the Royal Navy. Appropriating Hutton’s methodology has been crucial while exploring the historic negotiations between the two timbers. In addition, the research aims to contribute a nuanced understanding to the contemporary discourse on material movements under the lens of new materialism and neo-colonial networks of architectural fabrication. Cross-pollination with other methods of research will mitigate any shortfalls of Hutton’s methodology – including the use of photographic analysis to draw out implicit atmospheres of activity and the use of subject protagonists as a vehicle to digest complex networks of material movements. This multi-faceted approach is activated through three chapters. The first situates us in the context of the Age of Sail and the consequences of decisions made by Great Britain materialising in Royal Forests. It introduces the breadth of literature that this research tackles whilst making way for a reciprocal condition to be established. Procedural in nature, the second section explains the need for its existence before comparing the happenings of British Burma to its counterpart in the imperial centre. Finally, the third chapter sheds light on the knowledge gained through research – demonstrating the efficacy of the methodology and the foregathered contributions offered to contemporary discourse.

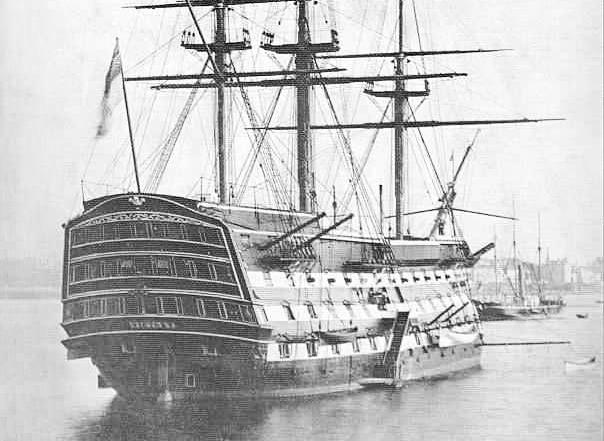

The banner translates to “Britan’s Glory and Protections.” It seems to draw an obvious relationship between the oak tree pictured centrally and its ‘product’ (the naval vessels) in the background. The figure is Britannia, symbolising Great Britain and its care for the oak seedling (pictured in hand). The image can be read as propaganda to support the views of infinte timber resources and the consequent security of the nation.

Source : Irene Cheng

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 6

Eighteenth Century Illustration

FIGURE 3

5

4 ‘Western Firms Cer4fied as Socially Responsible Trade in Myanmar Teak Linked to the Military Regime - ICIJ’.

This dissertation is a personal attempt to dissect the spatial experience of Epping Forest as it stands today. The scars of material movements are overwhelmingly evident within the forestscape, a phenomenon that I find incredibly challenging to overlook. While attempting to understand the intricacy of the material abundance that is ‘The People’s Forest,’ the research discovers a turbid history of resource extraction with discernible relevance to contemporary global material portraits.

In the few adolescent years that I spent growing up in India, we would often frequent the sea of furniture stores in our city. There would always be a section dedicated to Teakwood furniture and it would always smell delightful. Learning from Hutton’s work, it is crucial to identify and declare the justification behind the chosen material reciprocity being researched through this dissertation. I believe the faint memories of those furniture negotiations had a part to play in my decision to explore teak’s role in imperial shipbuilding – perhaps to dissect what causes me to perceive the timber to be exotic in some way.

Ultimately, the dissertation engages with the media that has surfaced in 2021 following the coup d’état in Myanmar by the country’s armed forces. The “blow to democracy” has caused immense civil unrest, with the military generals taking control of major industries and economic sectors, including the Myanma Timber Enterprise (MTE). 4 There is a question of the extent to which the establishment of colonial networks of extraction during the Age of Sail has made it possible for the junta to thrive through the weaponization of Teak exports.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 7

8

Preserving Royal Forests 01./

Venturing into the ancient, mystique-filled expanse of Epping Forest without any guidance is a challenge, to say the least. My deliberate immersion was purposed to lead to a group of peers – all gathered for a field visit to ‘The People’s Forest’ – as it is colloquially known. This serendipitous journey unveiled the forest’s unique capacity to unite disparate paths into an enriching narrative of silvicultural awareness. The assembly point was located at one of the “most picturesque spots” in the forest – The Lost Pond (appropriately titled). Its praise seems to subdue the extent to which the pond communicates itself as a symbol of human terraforming of forest landscapes. Its proximity to Loughton made this deposit of glacial moraine the perfect place to dig for construction gravel in the 1920s, leaving behind scarred landscapes encompassing ditches of removal and scrapes of extraction. Nature has done its best with the cards it was dealt, effectively carrying out a beautification project of the construction mine left behind (Figure 5). 5 It is important – to give context to the discussion in Section 2 –that we recognise it was the freedom granted to the public of England which allowed the forest to be established as a nonexcludable and non-rivalrous public good.

Understanding the nuances in this historical account instigated a retrospective analysis of the trees that were encountered en route. These too had scarred, and perhaps healed, in a similar way. Visually analysing these trees, as seen in Figure 4, led to a pattern of physical similarities to emerge. Dense clusters of new shoots located just above where the browse line would be of grazing animals. Swollen knobs of irregularity on stunted

trees – following the same, almost mechanical line of scarring. Gnarled trunks with rounded bushy tops of younger growth. This was the first kind, displayed mostly by the Fagus sylvatica (European beech). The second could be described as not having much of a trunk, but rather a stool, from which a clump of slender, straight stems surface. These were in clusters – possibly driven by the age of the growths themselves (seen in Quercus robur (Pedunculate oak)). An unexpected conversation with a local forester (Liam Davis), during a subsequent visit, suggested that these scars were a monument to historic sustainable forestry practices of pollarding and coppicing. Their presence suggests that the forest has been

Pollarding and Coppicing

Pollarded and Coppiced trees near Blackweir Pond in Epping Forest. Histories of material excavation embedded in the rich visual landscapes encompassing all corners of the forest.

Source : Author (2023)

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION

9

5 Verderer Paul Morris, ‘The Lost Pond, Epping Forest Forum’.

10

FIGURE 4

a material resource in its past, however, the extent to which they have healed, explained Davis, meant that these routines are carried out no longer. The forest and its ecosystems are left undisturbed.

Samuel Pepys’ (a naval administrator in the seventeenth century) diary entries on Epping Forest state that it was the establishment of the Commonwealth which led to the deformation of Royal Forests from “a green retreat” to a “nursery for timber.” 6 This is perhaps when the modern era of managerial relationship between humans and the forest began – introducing methods of control and leverage for capital and political gain. The civil war that led to the creation of the

FIGURE 5 The Lost Pond – Gravel Pit

Early use of the gravel pit near Monkswoood (now ‘The Lost Pond’) for recreational purposes

Source : Janis Halford (1977)

Commonwealth coincided with Britain’s engagement in Anglo-Dutch wars (during the Age of Sail) – leading to an increased reliance on the predominantly timber naval fleet and requiring the deforestation of most Royal Forests that were left unprotected after Cromwell’s ‘rebellion’. 7

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 12 11 01./ PRESERVING ROYAL FORESTS

6 William Addison, ‘Epping Forest, its Literary and Historical Associations’

7 Harris, ‘God’s Fury, England’s Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars - By Michael Braddick’.

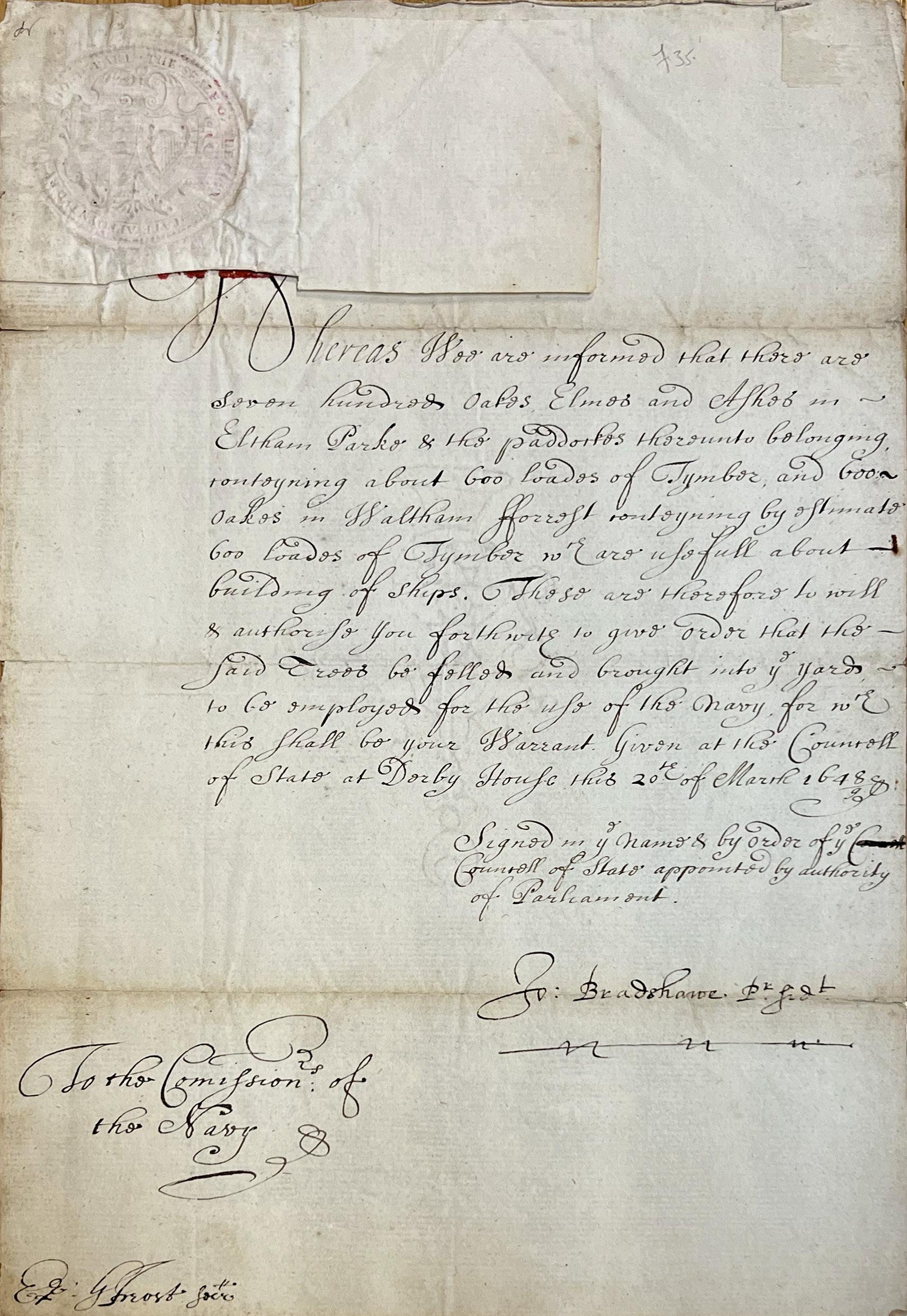

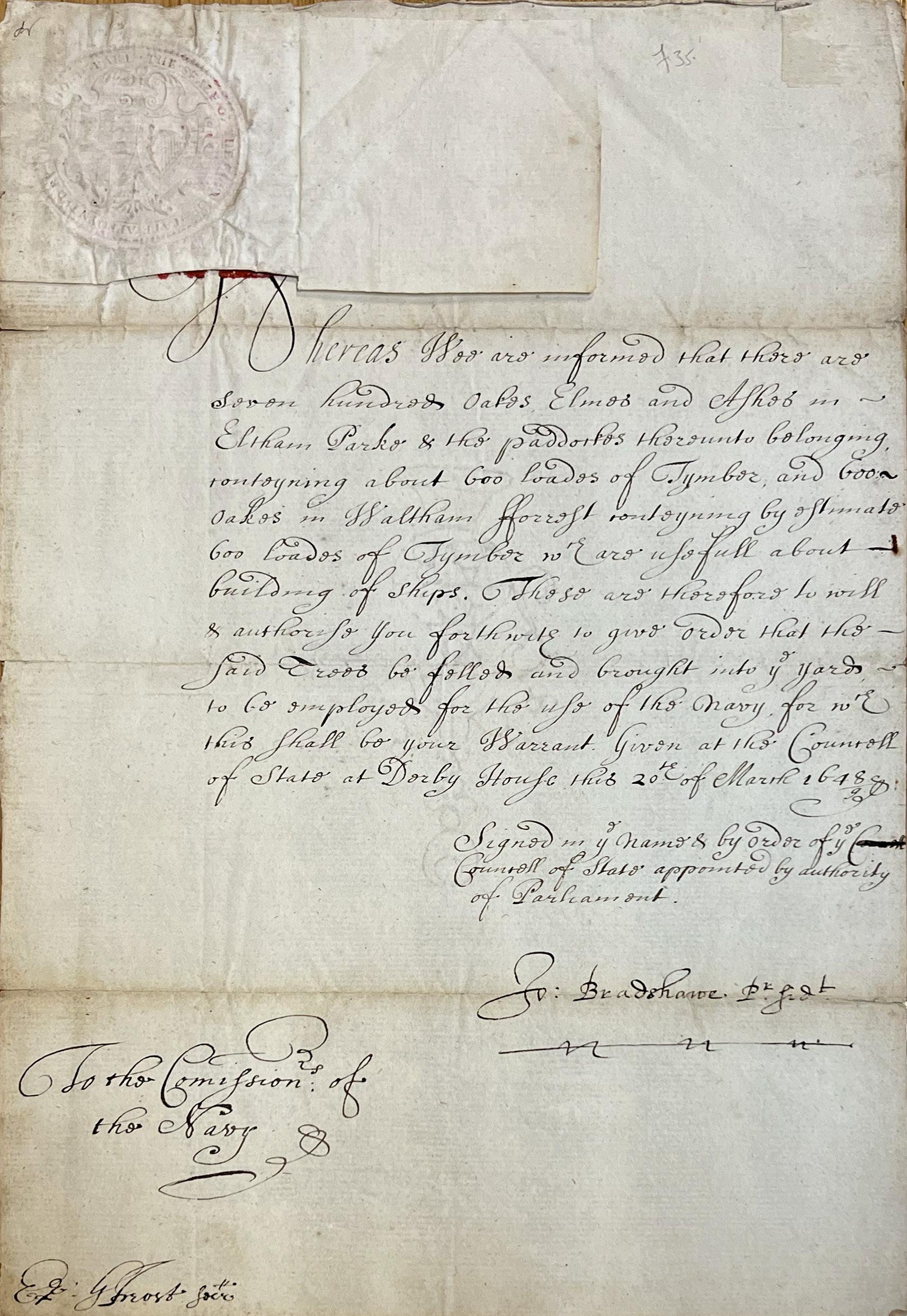

“600 Oaks in Waltham Forest containing by estimate 600 loads of Timber which are usefull about building of ships. These are therefore to will & authorise you forthwith ot give order that the said trees be felled and brough into ye yards for the use of the Navy.”

[Transcribed with the aid of Transkribus]

The Caird Archive, housed at the National Maritime Museum, preserves collections that pertain to historic naval operations and their impact on the management of Royal Forests. Figure 6 details the operation carried out by the President of the Council of State (John Bradshaw) in Waltham Forest, warranting the Commissioner of the Navy to fell oaks in such woodlands. As Bradshaw humbly describes the six hundred trees that are “suitable” for shipbuilding, it conveys the construct of order as a vehicle of urgency and desperation for utilitarian methods of thinking to be established. 8 The letter may symbolise the rigidity with which all workers were expected to act –constricting the development of an emotional relationship between humans and the living ecosystem of the forest.

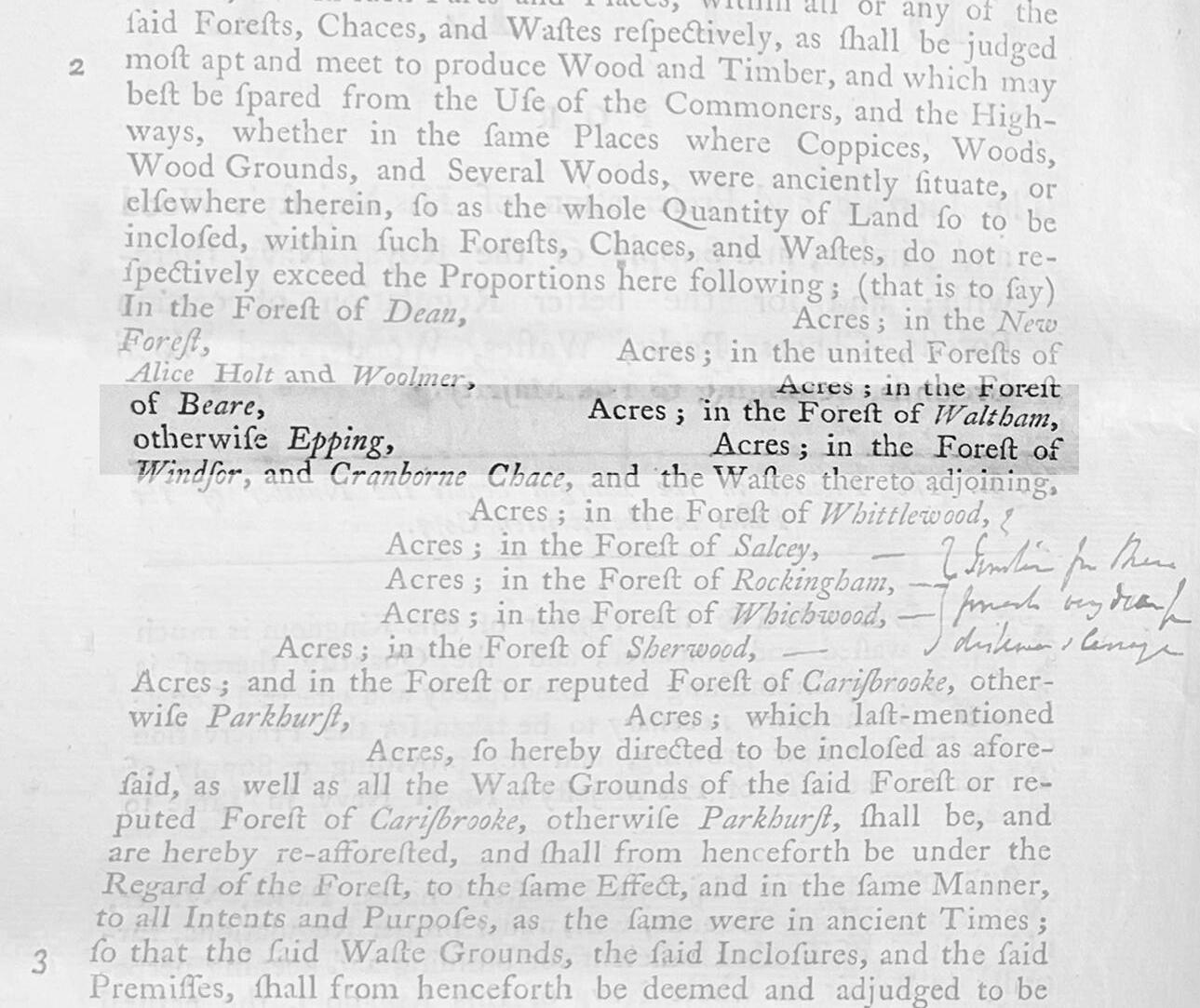

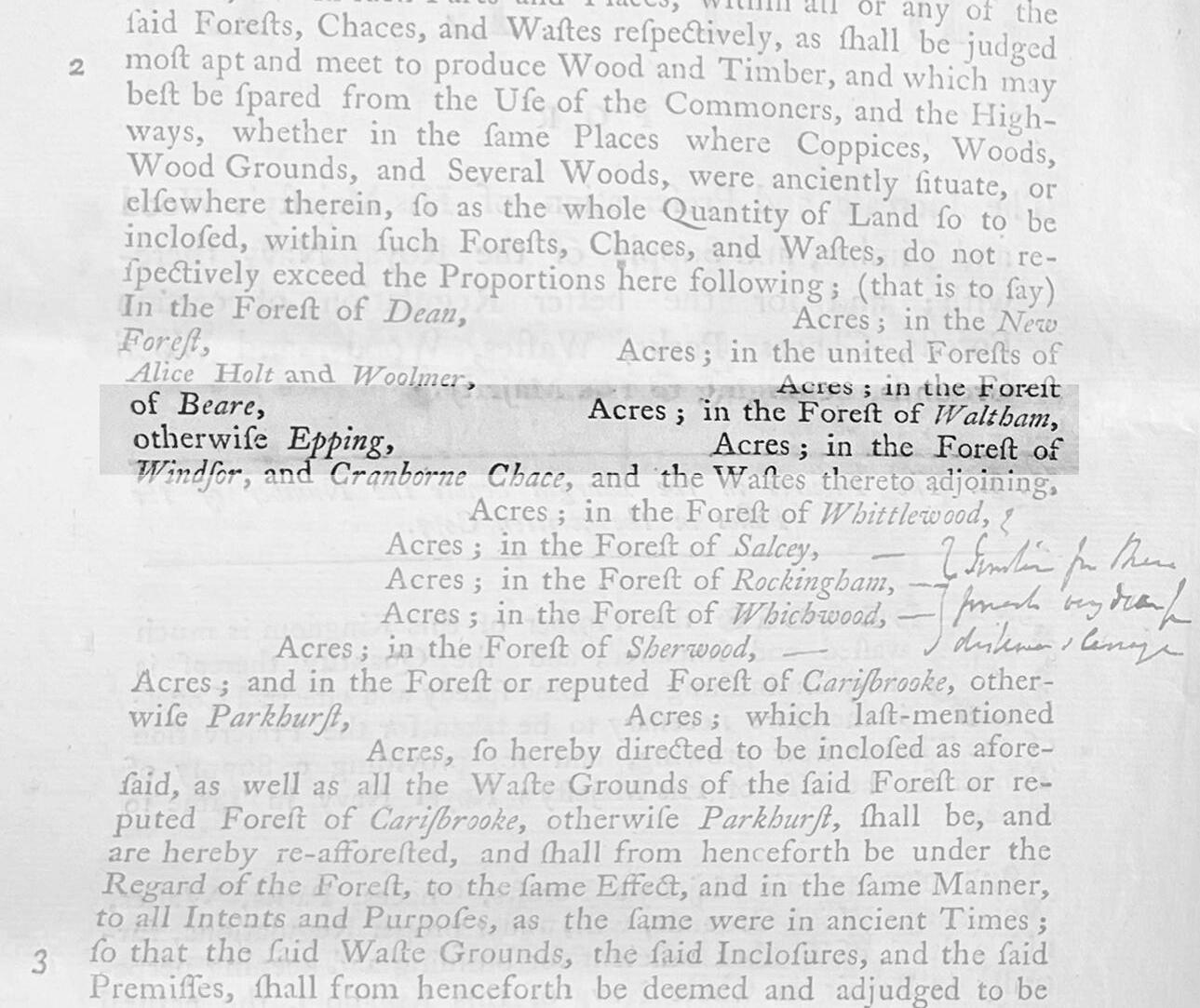

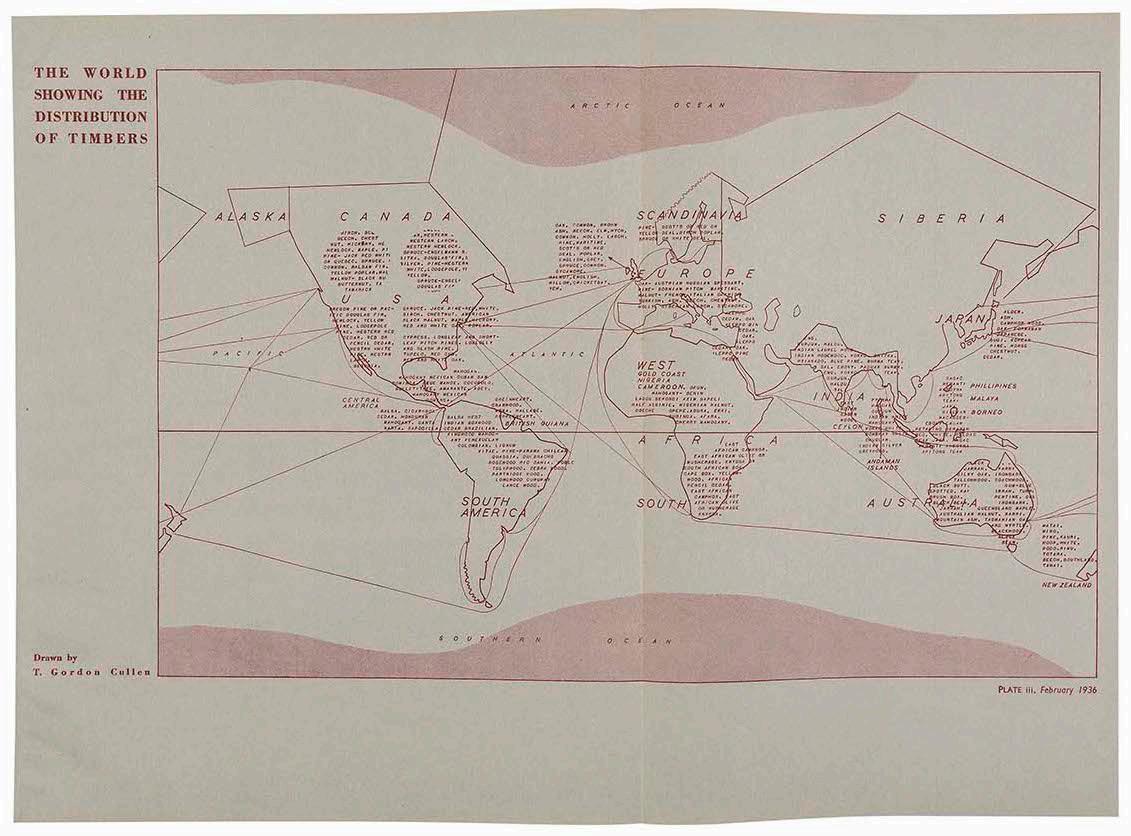

The woodlands in England have always garnered regard from the ruling parties. The Royal Forests have been controlled through legislation such as the Statute of Enclosure of 1482 and the Statute of Woods (1543) – both of which set guidelines for the management practices which must be employed for the protection of the woodlands and their enjoyment by the common. The intended consequences deviate with the local and political demands of the nation, as demonstrated by the unified ambition between 1652 and 1862 to fulfil the timber needs of the Royal Navy. Figures 7a and 7b are an emblem of this ambition, transparently bringing into legislation the priorities of the nation – its survival. The irony, as highlighted previously, is the protection of the right to the destruction of natural resources for colonial advancement. The bill restricts private enclosures of the forest, and it appears to take ownership of all aspects of the forest under the disguise of national security. It is perhaps the enforcement of such legislature that instigated a lethargic approach towards forestry management from its locals – out of sheer disappointment. It can be argued

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 13 01./ PRESERVING ROYAL FORESTS

Letter from John Bradshaw to the Commisioner of the Royal Navy (1648)

FIGURE 6

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 14

Source : National Maritime Museum (Caird Archive)

8 ‘Collecton of Letters Signed by John Bradshaw (1602–1659)’.

FIGURE 7a

Explicit listing of the “Forest of Waltham, otherwise Epping.” Initial hint of eventual seperation of the two entities. A cryptic message of colonial extraction causing unfavourable division of assets within the country.

“A Bill for The Increase and Preservation of His Majesty’s Wood and Timber, and Supply of the Navy therewith ... Whereas the Timber of this Kingdom is much wafted and impaired, and the Quantity thereof is daily diminishing, and some speedy and effectual Course is therefore necessary to be taken for the Preservation of the Timber now growing, and for providing a Supply of Timber for the Use of His Majesty’s Royal Navy in Time to come: ... under proper regulations, furnish a Stock of Timber sufficient for building and keeping perpetually in Repair the whole Navy ... the natural Defence and Glory “

that through the monopolisation of many forestry activities in a similar fashion, the enjoyment and pride in silviculture was lost and has resulted in the worsening condition of the present-day Epping Forest.

The Royal Navy’s calibre characterised Britain’s global political position during this period. Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary, acclaimed that “diplomacy and protocols are very good things, but there are no better peacekeepers than wellappointed three deckers.” The pride in their naval supremacy was employed to boost public morale – which raised the value, both monetary and sentimental, of English-grown Oak. 9 As of 1810, the Royal Navy required timber from 48,000 fullgrown trees – which would each have taken a century to reach maturity. This produced 72,000 ‘loads’ which is fifty cubic feet. The demand accounts for both the construction of a new fleet and the repair of the existing ships. 10 There seems to be no harmony between the existing viable supply of raw materials and the creation of demand by the Royal Navy. This method of development not only stretches the economic systems to provide fundamental goods through a frantic attempt at achieving market equilibrium, but more worryingly puts an inexhaustible strain on our globe as a material resource. This outlook is further demonstrated by the lack of coordination between the operators at the Royal Dockyards, Forests and Navy.

On its way to being a part on a ship, each length of timber cut from the Epping Forest stands would be taken to Barking. To maintain profits, these were transported via horse and carriage to the streams nearest to the forest. From here, there was a slide into a creek which led to the Thames. Rafts were used for transportation of the logs to the Royal Dockyards at

9 Crimmin, ‘Searching for British Naval Stores: Sources and Strategy c. 1802 – 1860’.

10 ‘The Line Upon a Wind: The Great War at Sea, 1793-1815’.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 15 01./ PRESERVING ROYAL FORESTS

Bill Bill

Figure 7b

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 16

Source (Top and Bottom): National Maritime Museum (Caird Archive)

11 Addison, ‘Epping forest, its literary and historical associations’.

12 Atkinson, ‘Shipbuilding and Timber Management in the Royal Dockyards 17501850’.

13 Pollard and Robertson, ‘The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914’.

14 Atkinson.

Deptford and Woolwich. They typically expected shipments of Oak, Elm, Beech, and Fir (softwoods such as Pine and Spruce). This supply chain was worn out by 1725 – as a result of the best (tallest) trees being felled and young stock not being replenished. 11 Through Atkinson’s thorough description of the malfeasances in the accounting of timber in its various stages, there emerges a nuanced representation of its material properties. 12 A construction material with a life stored in each species, making it difficult to stockpile. It is the risk of disease, fluctuation in quality, and the unpredictability of supply that underscores its value.

The positioning of the dockyards where these vessels were crafted was driven by the proximity of “cheap supplies of labour, capital, raw materials, land, a ready market for ships, and the existence of subsidiary industries,” state Pollard and Robertson – resulting in a fidgety and mobile industry which happened to be centred around the Thames in 1841. 13 Shipbuilding begins with the Master Shipwrights production of a ‘ship draught’ – a construction blueprint. This was also supported by the production of scale models for instructional assemblages. Much like the construction industry of the twentyfirst century, the processes of designing, managing, funding, and fabricating were decentralised. Regimental delegation of tasks results in a reduced care for the craft of building; with drawings being drafted without consideration for the systems at play in the construction of the barge. The Surveyor General of Woods would then take the baton back to the forests of England, foraging for timbers. 14 Representative of the purpose it serves, a ship is a complex output of engineering (Figure 1). Each material has its inherent agency, and these collide and engage in a parley when they reach the assembly yard. The choreographing shipwrights take control of these players and

teach them how to work together. Granted the output may tell tales of a successful negotiation, but a closer look reveals the fragmentation that is exposed and amplified in the processes of construction, use and repair. Thankfully, it is the reciprocity of the circumstance and the utility of the ship that will later allow us to circumnavigate the globe and take note of the wider implications of the practices that made the voyage a possibility.

Banbury discusses the upkeep of the Royal Dockyards in his publication ‘Shipbuilders of the Thames and Medway.’ He states that the eighteenth century witnessed large amounts of corruption in the dockyards – a complication prevailed by an overstocked reserve of equipment and workers for emergency situations. 15 It seems as though this would result in an inefficient workforce with a lot of leisurely time on their hands. In addition to the relaxed working timeframes, the craftspeople were “reasonably well paid.” 16 Dockyards established generational communities of craftsmanship. There were local, social benefits to be realised through the access to training and job security provided by this industry. The people in the vicinity of such dockyards would also profit from their right to collect ‘chips’ – offcuts of timber less than six feet long and ‘as much as would go under one arm. ’17

In the section concerning ‘Raw Materials,’ Banbury recalls the ‘domination of oceans’ leading to the forests of the world being open to English Shipbuilders. He uses naively optimistic language, regarding supplies of North American timber as “limitless” and teak and mahogany from Asia as “unlimited.”18 The inherent care for the human resource and its agency in the system of shipbuilding, contrasted by the blatant disregard for any ecological ramifications of commodity-driven terraforming

15 Banbury, ‘Shipbuilders of the Thames and Medway.’

16 Banbury.

17 Banbury.

18 Banbury.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 17 01./ PRESERVING ROYAL FORESTS

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 18

activities reveals the attitudes of many during this period.

Epping Forest, in the present day, is marketed as a service for the public’s consumption. There seems to be a population that adores their right to visit and the amenities that it provides. As the dissertation begins its exploration of the reciprocal landscape, it is key to understand the contemporary standing of the forest and the architectures that surround it. The City of London has maintained ownership rights and established byelaws for the protection of the forest. Many other institutions have taken an interest in the preservation of this ancient forest (as identified in the stakeholder mapping in Figure 8). It is identified as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) however a large portion of this site is deemed to be in an unfavourable condition by Natural England, showing no signs of improvement. 19 Urban sprawl into the edges of the forest can be inculpated for some of this degradation, nonetheless, the immune system of the forest seems to have weakened over time. Silvicultural experts believe that managed felling of trees is of benefit to the overall health of most forests. 20 Perhaps if the right of felling trees in Epping Forest had never been protected by royalty, and the turbulent dynamic of the ownership’s purpose was a myth, then the forest today would be loved with axes and loppers rather than with an overpopulation of noticeboards and wayfinding posts.

parties invested

development and protection of the Epping Forest to discern the parties that may be affected and should be considered when discussing the current conditions within the Forest.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 01./ PRESERVING ROYAL FORESTS 19

19 Superintendent of Epping Forest, ‘The Condition of Epping Forest SSSI’.

20

20 ‘How Cutting Down Trees Can Improve Forest Health’.

Stakeholder Mapping

Mapping the various

in the

Source

Influence Interest Residents Recreational Visitors Meet their Needs Least Important Essential Players Show Consideration

FIGURE 8

: Author

A Terraformed Colony 02./

After the deforestation of domestic forests, Britain was constrained to obtaining materials from unsubstantiated markets. The exclusive glorification of English Oak had to be redacted with haste – ironically celebrating the success of Baltic timber for the upkeep of the ‘native’ fleet’s credibility. The ‘experience’ of the Royal Navy Board calculated the inferiority of Baltic supplies, justified by its liability to decay. 21 This was perhaps an excuse to mask the true reasons for hesitance: the threat of adversarial dialogue; vulnerability to enemy naval warfare; and elastic, unfavourable, costing policies. All these reservations came to be true, with coercive diplomacy from Britain destroying links to many international ports of timber supply.

socio-economically viable exporter market – and the “working” conditions of exploitation at play.

21 Pollard and Robertson, ‘The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914’.

22 Shell, ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant’.

23 Atkinson, ‘Shipbuilding and Timber Management in the Royal Dockyards 17501850’.

24 Oster, ‘Great Britain in the Age of Sail: Scarce Resources, Ruthless Actions and Consequences’.

There may be an entitled bias causing the gap in literature discussing the instantaneous divergence to colonised forests after the alienation from vicinal sources. Shell, Atkinson, and Oster contextualise their views through a timeline of international timber supplies – jumping from the Baltics to Asia without any further explanation. 22, 23, 24 Despite the varying focuses and personal beliefs of each author, it seems to be a clear indicator of the entitlement with which the Empire established itself, where the procrastinated consideration of their colonies for timber was down to logistical inconveniences as opposed to the ethical and environmental sustainability of these practices. The historical narrative introduces these landscapes with praise, speaking about the advent of teak and its well-established superiority in naval applications –forgetting to mention the lack of a locally established

It is the strength and the water-resistant properties of the species Tectona grandis (teak), which make it alluring to shipbuilders. The natural resin found in this timber makes it ideal for naval application, being instrumental to the function of the hull, in particular. 25 The heartwood remains durable and resistant to termites and fungal attacks in terrestrial and aquatic environments. With shipbuilding routines pushing timbers to their limit – mechanically and organically, it is not a surprise that Teak is valued for its ability to resist defects, such as “end cracks, surface checks, splits and twists.” This is complimented with great elastic qualities and a 25% reduction in dry weight compared with its Oak counterpart. 26

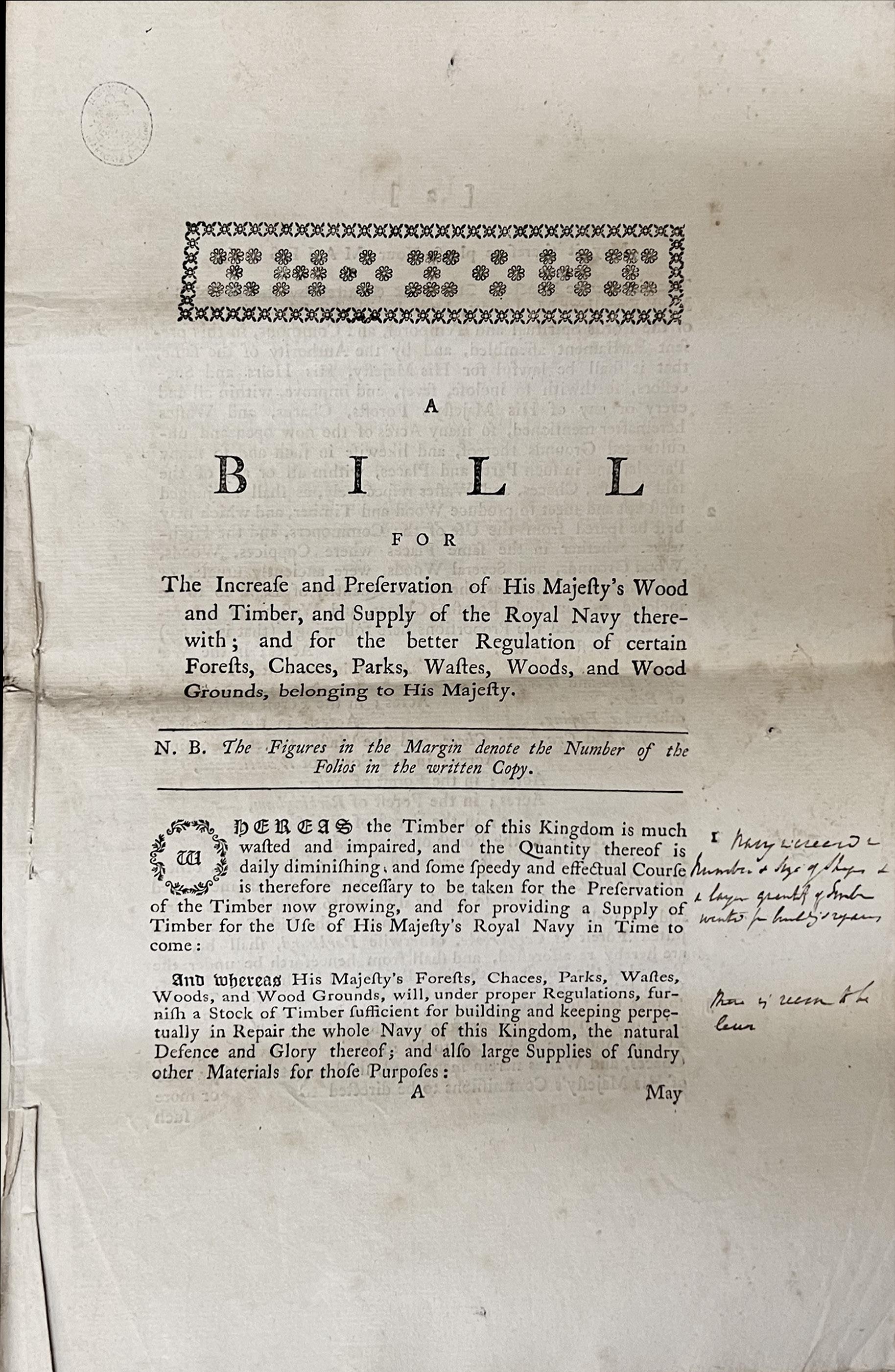

The scarcity of other timbers and the inability to explore new ‘timber worlds’ strengthened the argument for the use of teak. “Burma was a country of huge forests,” Shell describes –suggesting that the timber from other colonies (namely South Africa and India) was helpful but not plenty. 27 Although, Tripati argues that the Malabar northern teak was deemed the most valuable timber in the world for shipbuilding in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (named and sourced from the western coast of Malabar in India) (Figure 9).

28 The lack of agreement between these sources may be suggestive of other political practices at play that skewed an outward narrative of ‘small and vulnerable forests’ elsewhere – whispering at a logical and sympathetic approach from the British rule. If this

25 Shell, ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant’.

26 Tripati et al., ‘Teak (Tectona Grandis L.f.): A Preferred Timber for Shipbuilding in India as Evidenced from Shipwrecks’.

27 Shell, ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant’.

28 Tripati et al., ‘Teak (Tectona Grandis L.f.): A Preferred Timber for Shipbuilding in India as Evidenced from Shipwrecks’.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION

21

22

Anthony Webster, ‘Gentlemen Capitalists : British Imperialism in South East Asia, 17701890’.

were the case, it could be considered a ploy to justify and humanise the ensuing violent attacks on Burma, whilst shielding the Empire from the burden of the ecological disasters it may have caused in other colonies – an investigation that is out of the scope and purpose of this dissertation.

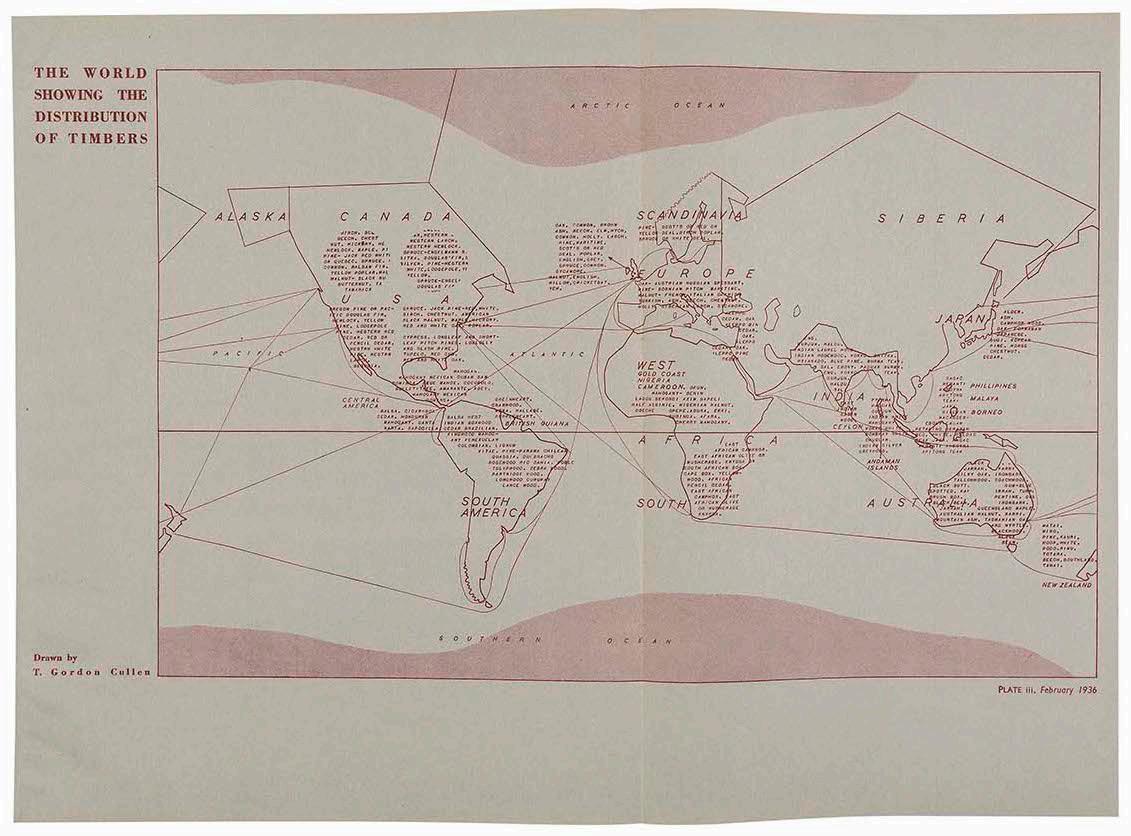

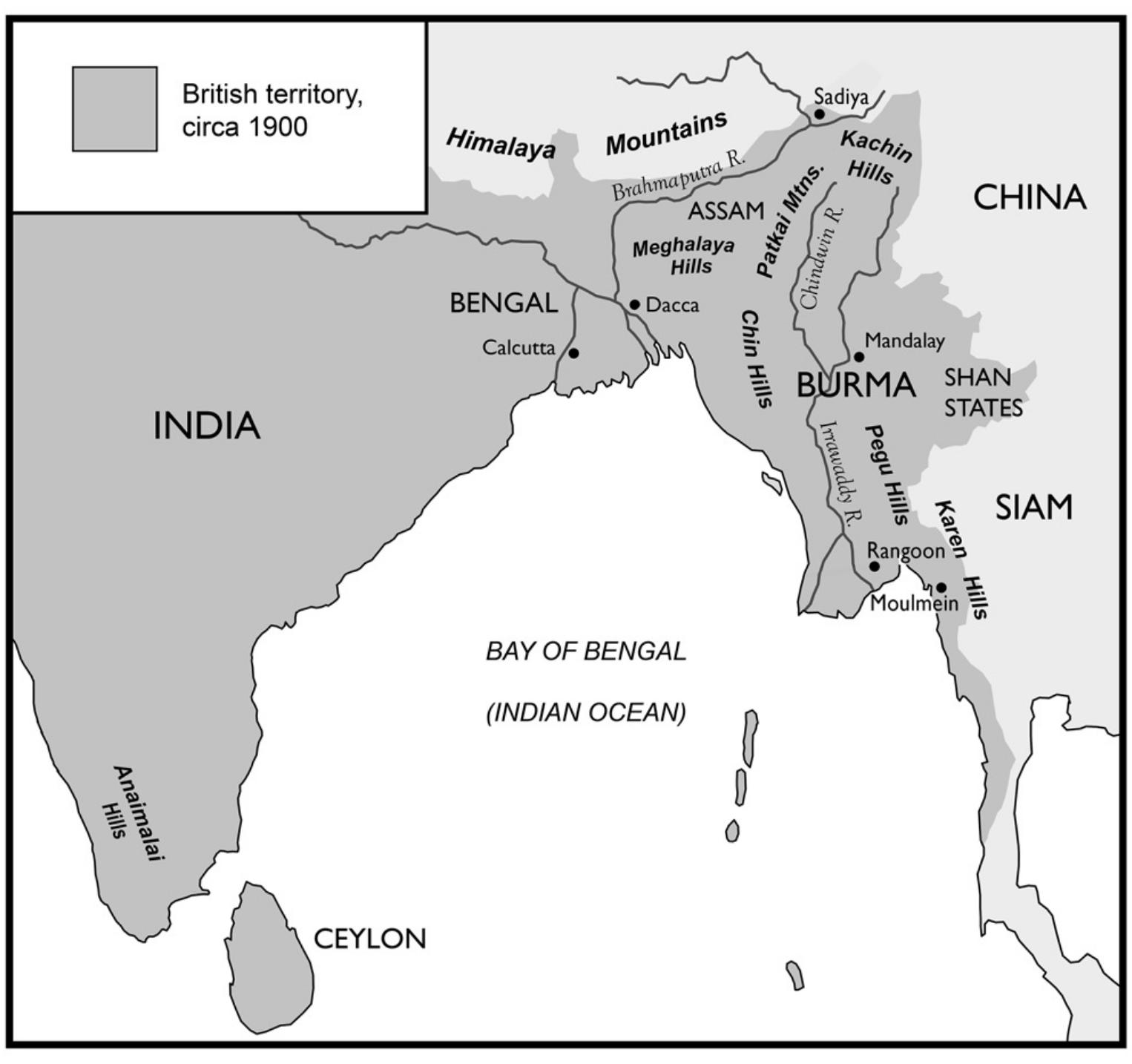

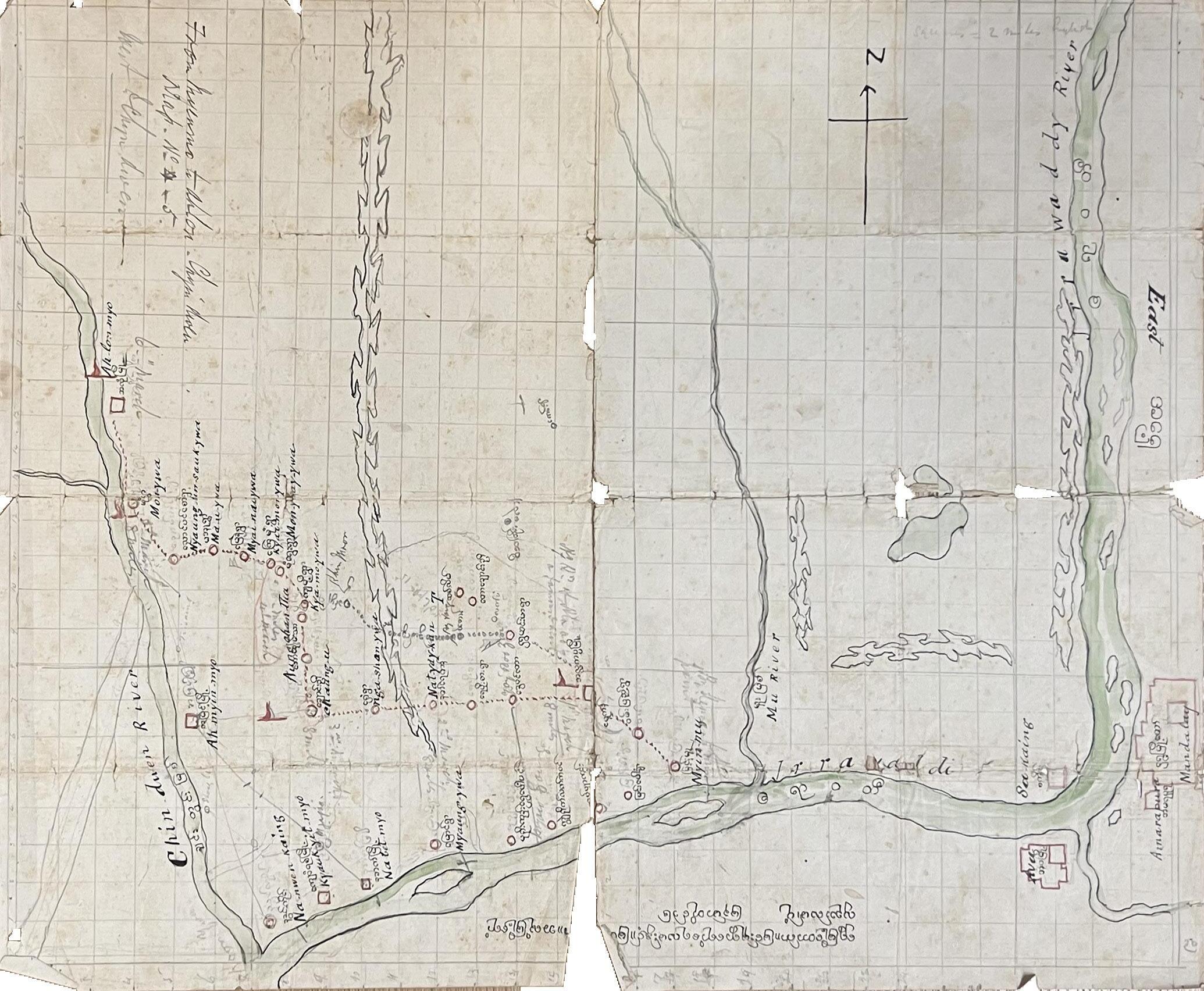

Speaking to the violent attacks, it took three Anglo-Burmese wars for the British Empire to gain control over all of Myanmar and its natural resources. The brunt of the losses suffered during this war, both of life and wealth, were faced by the people of British India. 29 The nature of the establishment of British rule in Burma foreshadows the practices of exploitation that were to unfold: attitudes of deflection of harm to other

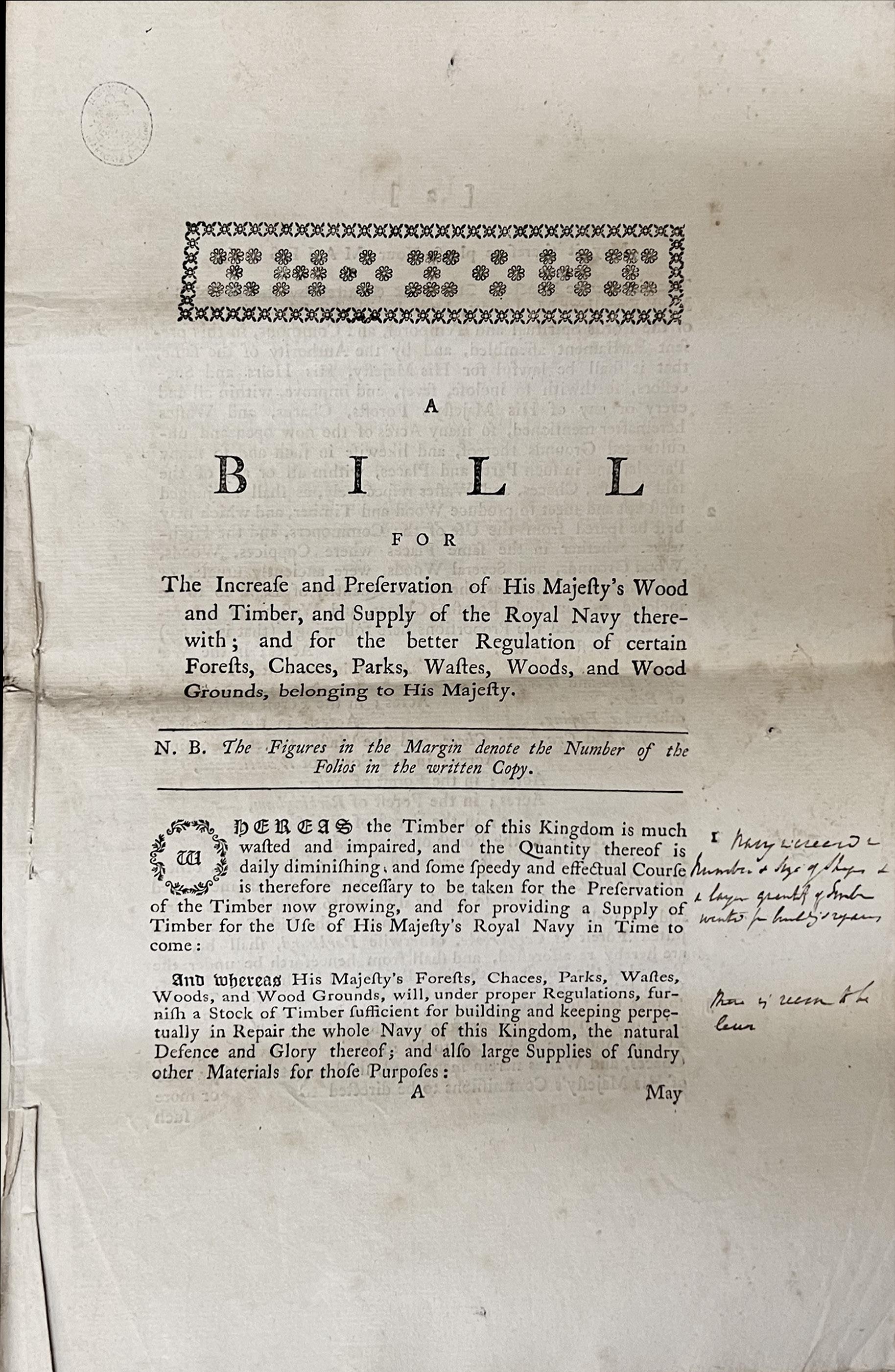

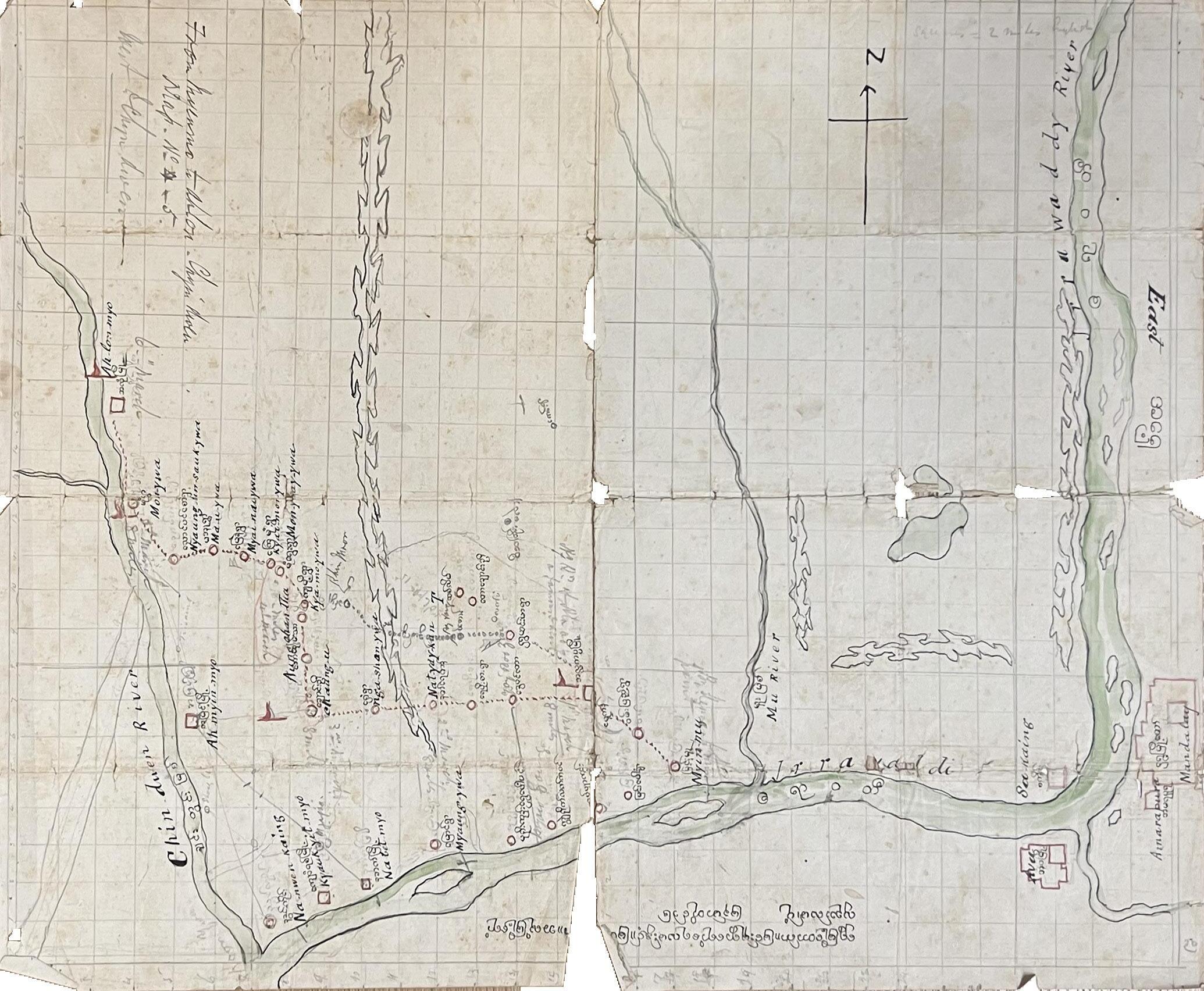

FIGURE 9

‘The World Showing Distribution of Timbers’

A map presenting the global picture of trade with British colonies producing timbers shown to be numerous.

parties, where possible, to ultimately benefit from the material, political and monetary successes.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 23

02./ A TERRAFORMED COLONY 24

29

Source : Gordon Cullen (1936)

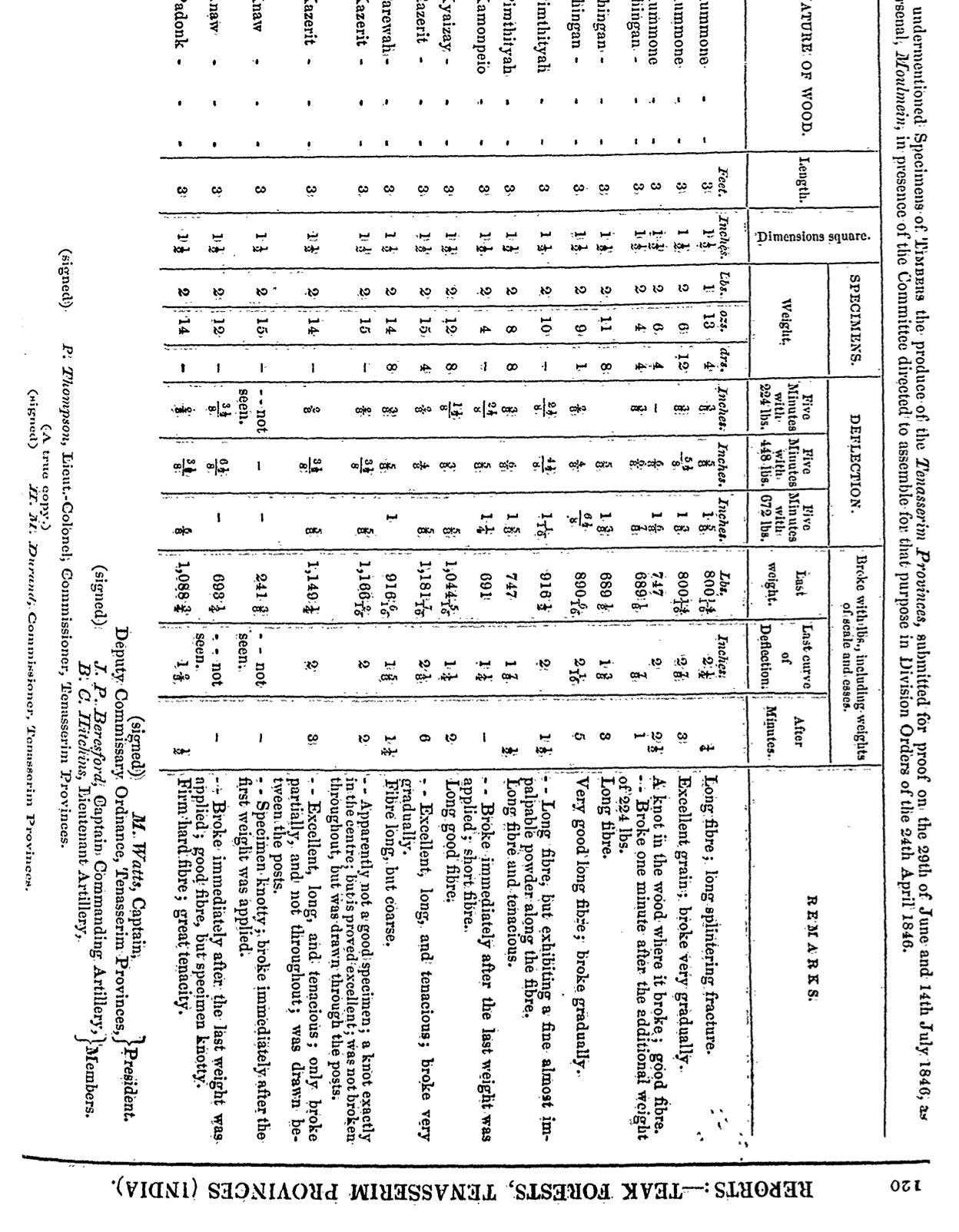

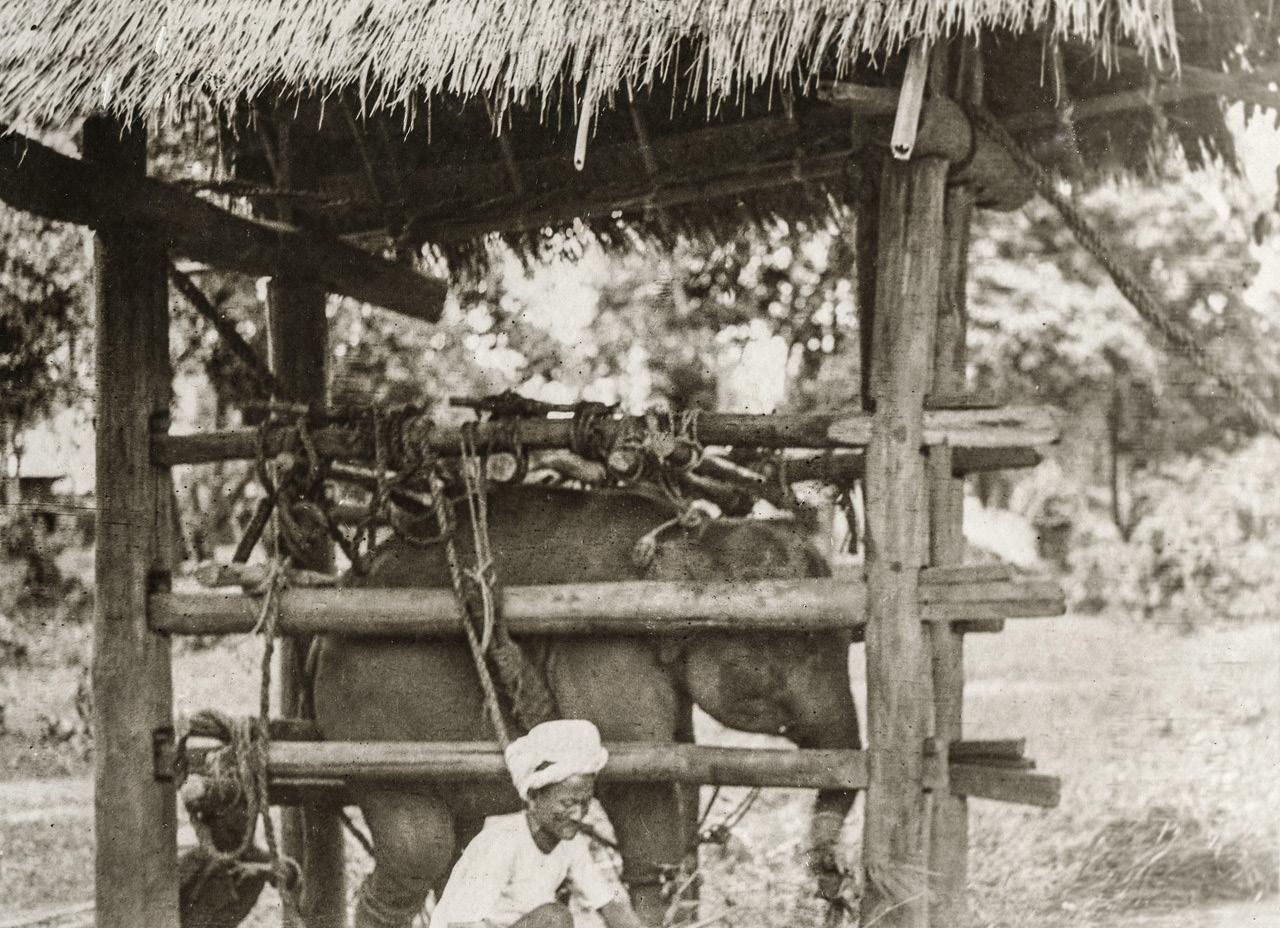

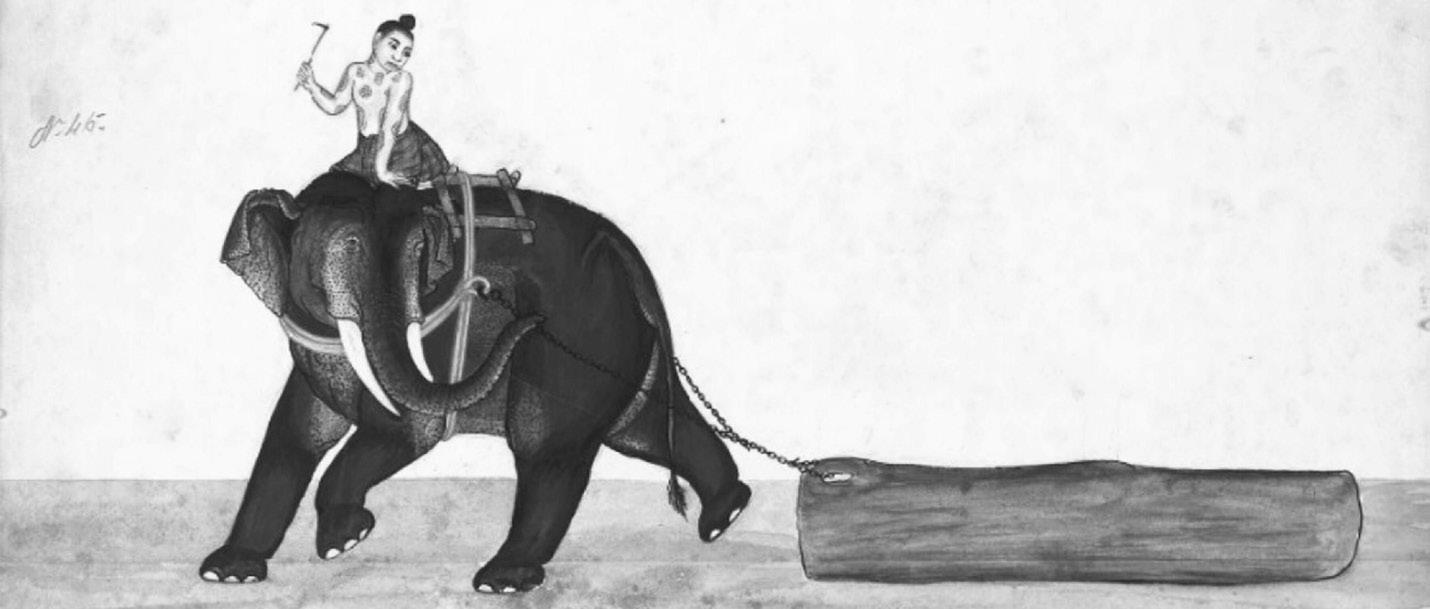

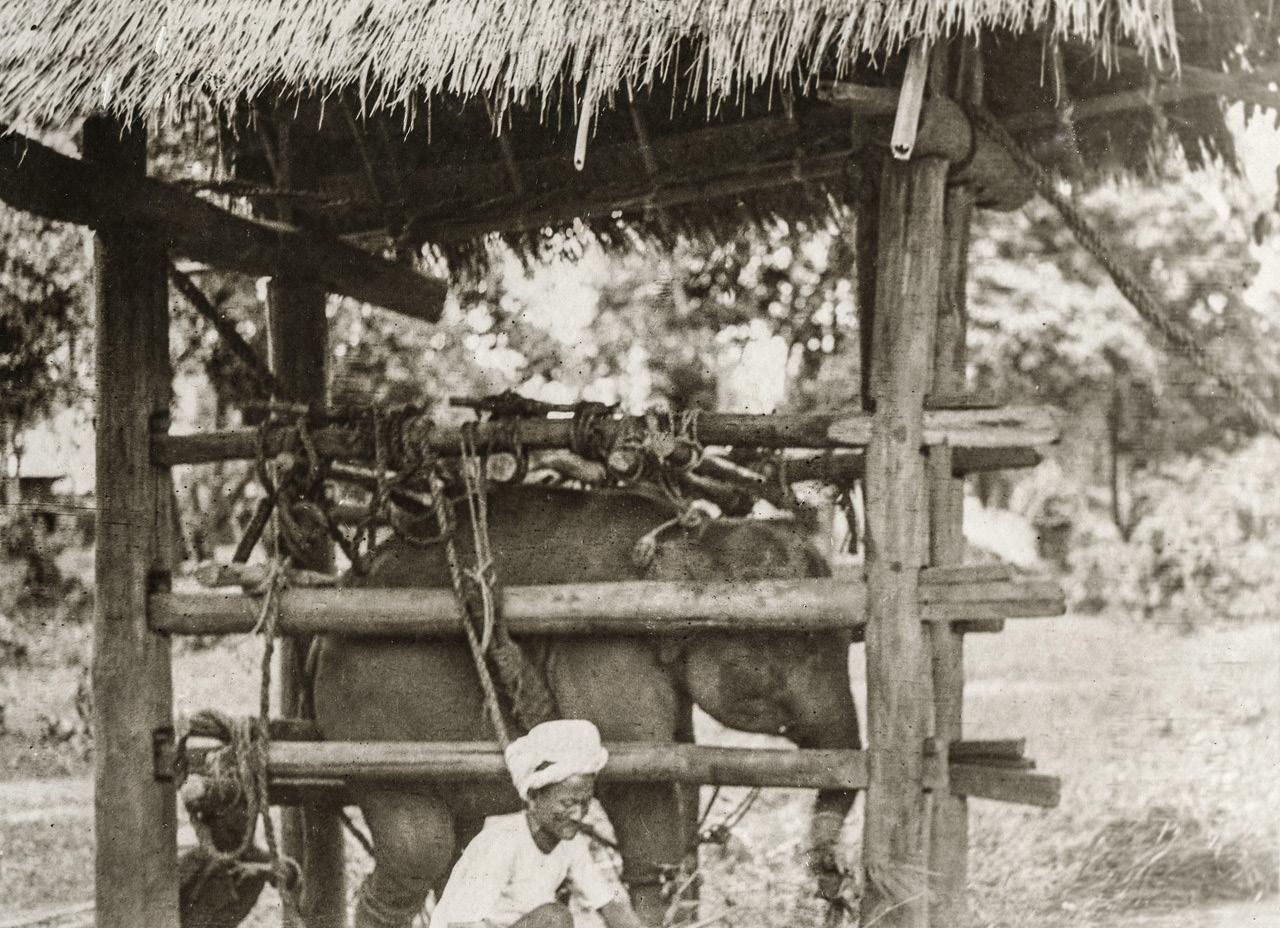

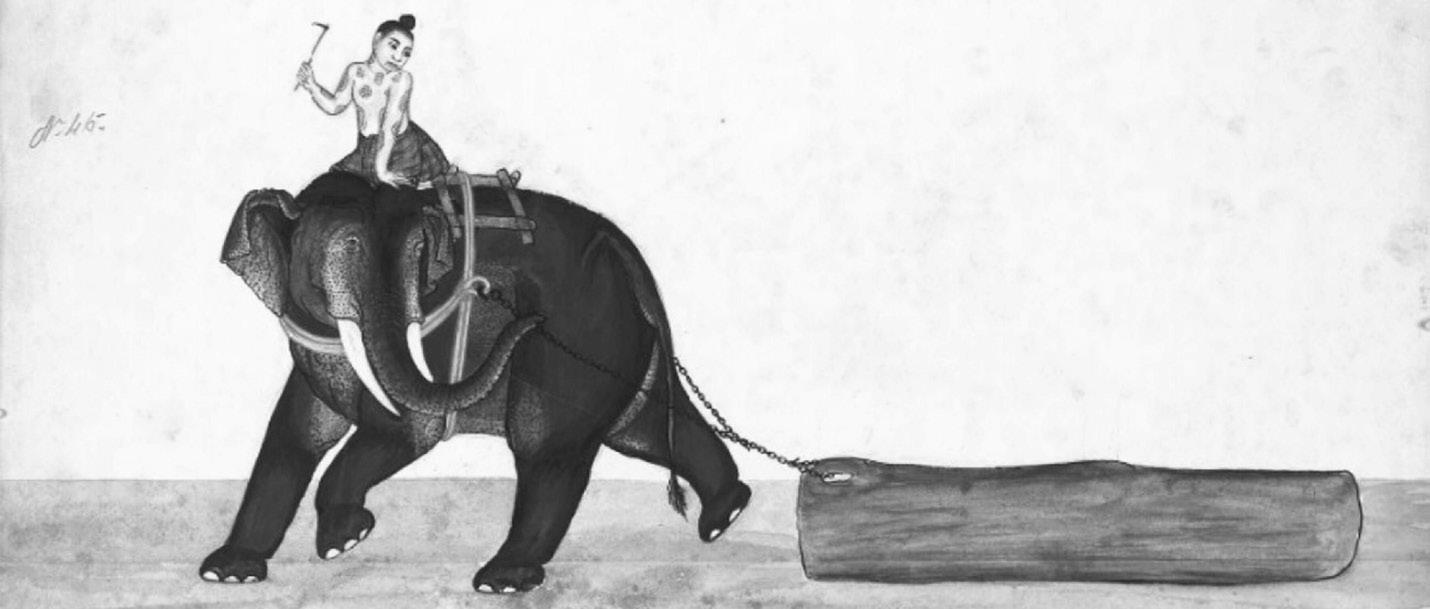

Although contemporarily celebrated for its aesthetic quality, the primarily utilitarian approach to sourcing the teak resulted in greed for the hardest teak trees. Propitious growing conditions were found in the amply sunlit hilltops –granting an occasion for the implementation of sophisticated engineering solutions. Elephants.

“The case of the colonial logging elephant stands as an important indicator that if a sentient, intelligent creature with irreplaceable labor power refuses to compromise its practices … to suit the needs of a political regime, the creature can force a concession from this surrounding edifice of power.”

– Jacob Shell, 2019, p. 1155

Due to the geographical proximity and the mis-approximated homogeneity of the two lands (see Figure 10), the British foresters that had previously annihilated forests in British India were sent to Burma for their ‘expertise.’ It became apparent, however, that the Burmese mahouts were the true educators in this exchange. The reckless forestry in India had resulted in the extinction of many native forestlands and consequently a depletion of the wild Asian elephant population. Elephantbased labour remained indispensable in the British teak logging activities. Being preeminent in negotiating the undulating and formidable forest landscape, Asian elephants grew into an “enigma” with which “the forces of the empire had to contend.”

30 Shell uses a contemporary analogy of global workforce mobility to understand the nature of the troubles that the British faced. Many developed countries supplement their skilled workforce through fluctuation of immigration policy – the living being reduced to an economic asset. The place of origin in the case of the ‘immigrating’ elephant workforce was the wild forests, whereas the developed establishment would be the captive work environment.

These elephants were forced into the visual culture of empire and their exploitation became a performance for western travellers to enjoy.

31 After all, the horses and carriages used in Epping were not quite as much of a spectacle. The horses do not seem to have been frequently starved, burnt and drugged into submission – as is the case for the elephants in Burmese forests (Figure 12).

32 Despite the sacrifices made by human and non-human hostages, it seems as though systems set up by the Forestry Department allowed the European firms to gain from most of the ‘blood-stained’ produce whereas the indigenous groups that lost their habitat to these extractive

30 Shell, ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant’.

31 Cheng, ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’.

32 Saha, ‘Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar’.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 25 02./ A TERRAFORMED COLONY

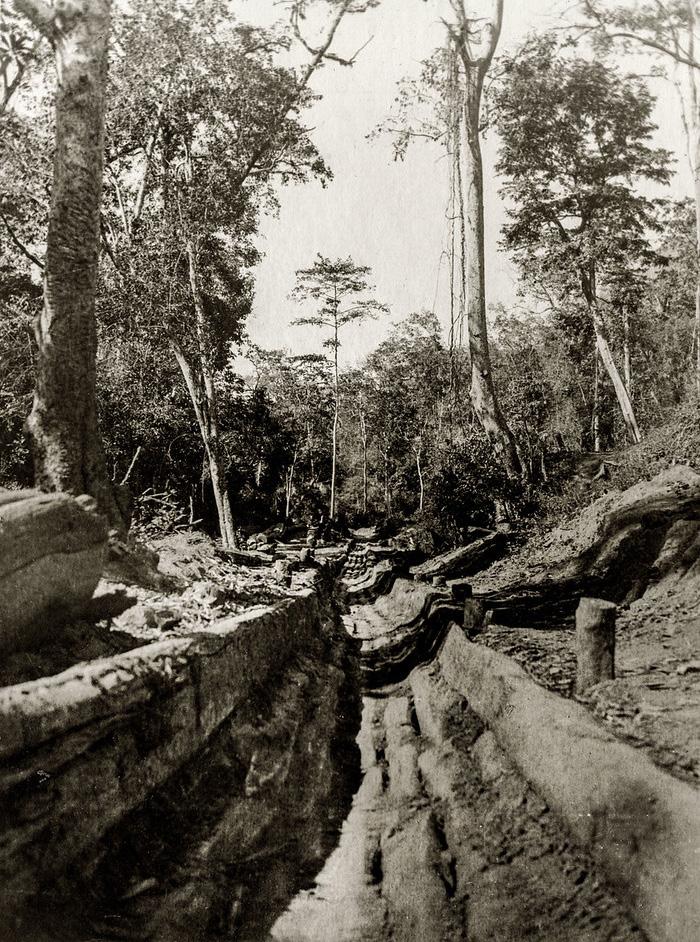

Cartography of the Indian Subcontinent

Displaying the proximity of Burma to India, imaginable routes of conquest and eventual trade. Draws a geographical relationship between the water and topological features within Burma

FIGURE 10

Source : Jacob Shell

26

were not able to benefit whatsoever from allowing the activities to take place in their back garden.

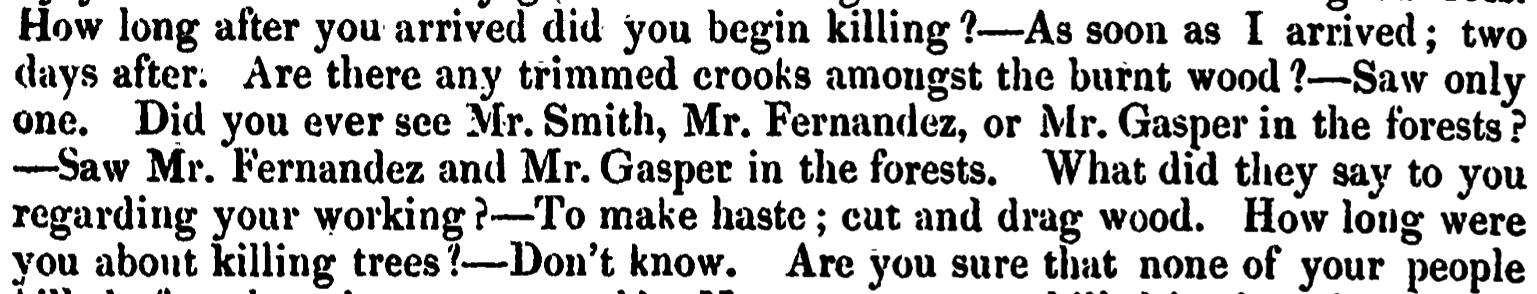

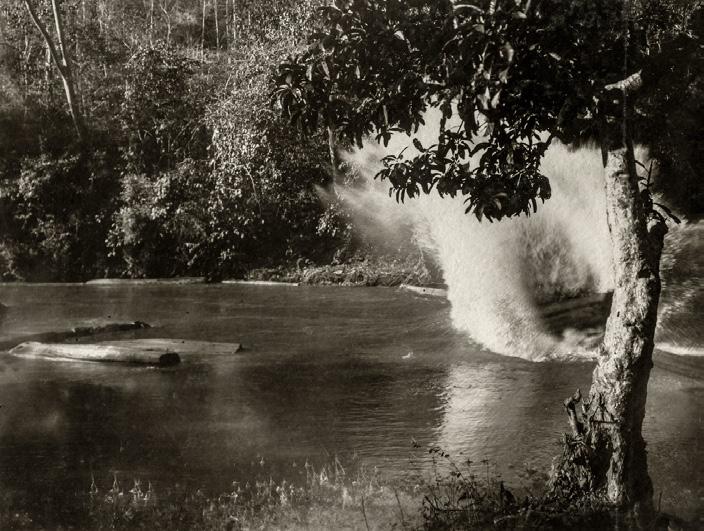

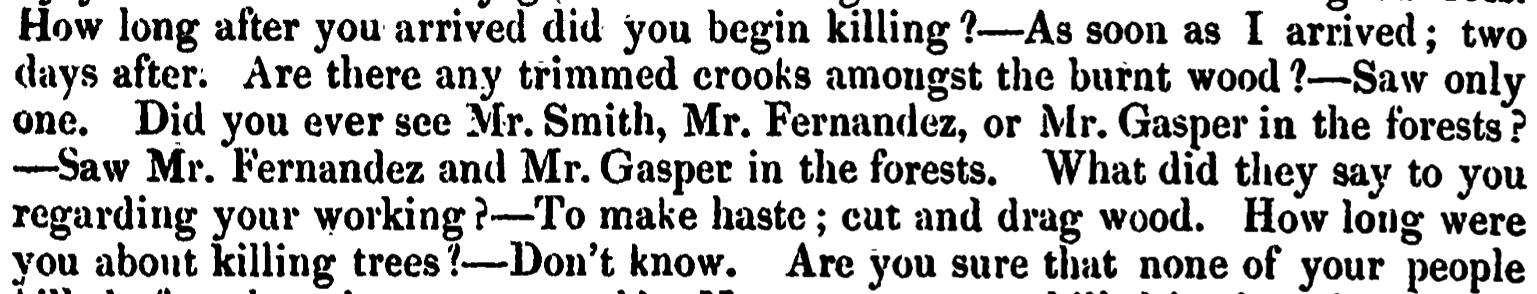

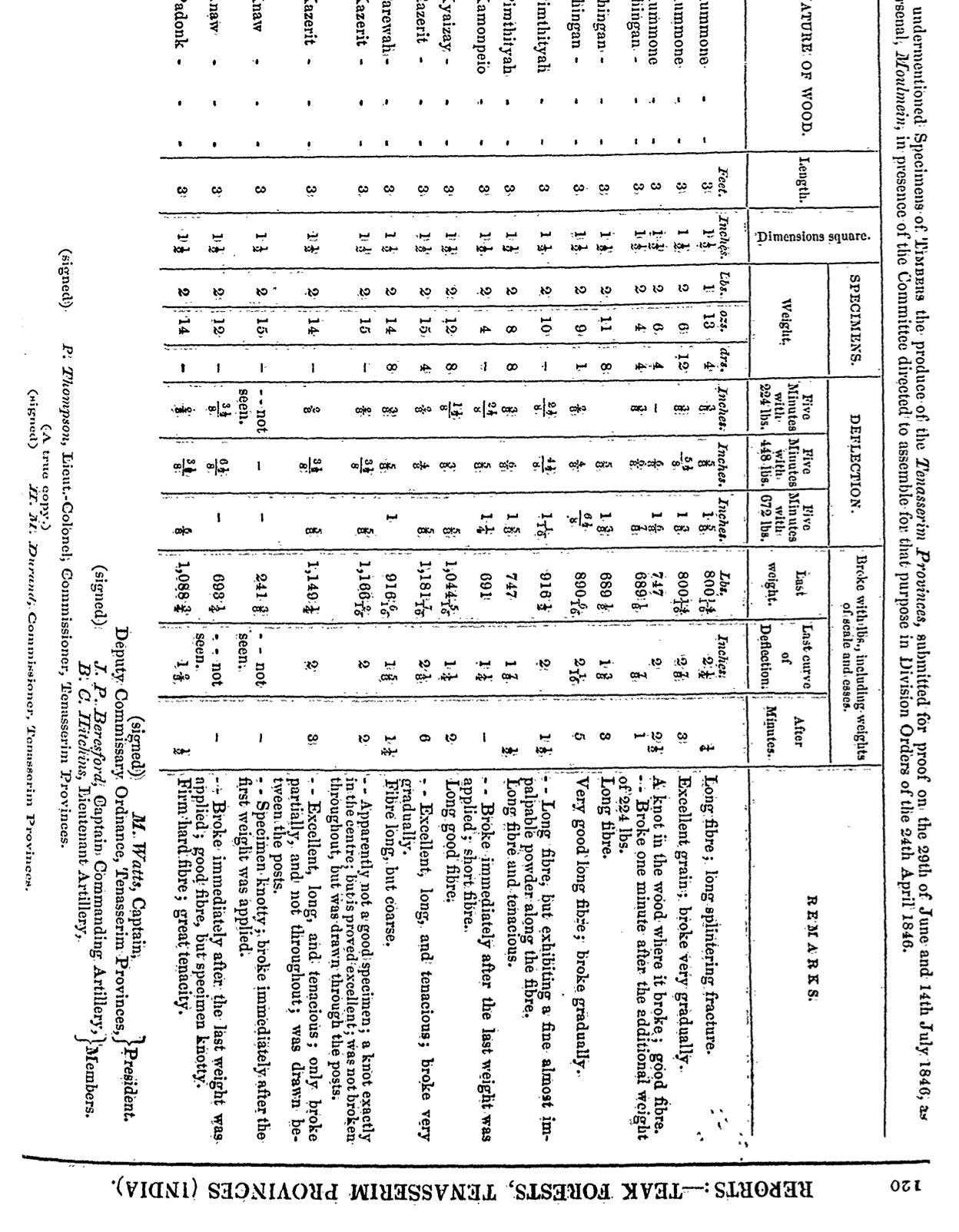

Figure 11a is an excerpt from the testimony of a forest worker, Kopaylow, regarding a Breach of Forest Rules in 1846. 33 In isolation, the transcription feels inherently violent and portrays a shameful confession of heinous crimes – although the transparency of the archive and distribution of these proceedings resonates with the perpetrator’s pride. The terms of the testimony grant immunity to Kopaylow for any breaches of the Forest rules, as long as they speak the truth. Bluntly denying any orders for the replenishment of the forest’s teak stock, they go on to speak about the actions of their “gang” as though gruesome, yet inevitable, murders were executed.

The statement being referred to in Figure 11b takes account of the commodities that were due to be extracted from the forests, with an obsessively thorough account of each log and its qualities. The refusal of the Burmese village population to comply with such colonial processes demonstrates the forceful nature of the extraction – revealing that the show of order and rigidity was imposed through coercion rather than an empathetic agreement.

The language used in Figure 11c encapsulates a feeling of pleasure in the process of observation by the committee. The resolution in the deflection readings exemplifies the scientific rigour with which the committee was expected to work.

Though the consequence of social degradation may not have been factored in by the Navy when plotting the heist – the scrutiny of the loot maintained an astounding level of entitlement. Others may regard the social value of these archival materials in a different manner; however, it is refreshing to come across evidence that is transparent and unfiltered – raw memos of candid conversations that can place the reader in these otherwise inaccessible dynamic landscapes of havoc.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 28 02./ A TERRAFORMED COLONY 27

33 UK Government, ‘Copies of All Reports Which Have Been Made to the India or Home Government Respecting the Teak Forests in the Tenasserim Provinces.’

UK Parliamentary Papers (1848)

FIGURE 11a

Source : The Maritime Museum

UK Parliamentary Papers (1848)

FIGURE 11b

Source : The Maritime Museum

UK Parliamentary Papers (1848)

FIGURE 11c

Source : The Maritime Museum

34 Squire, ‘Photographs Taken by My Greatgrandfather in Burma’.

35 Saha, Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar.

36 Cheng, ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’.

37 Hutton, ‘Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements’, p. 192 – 193.

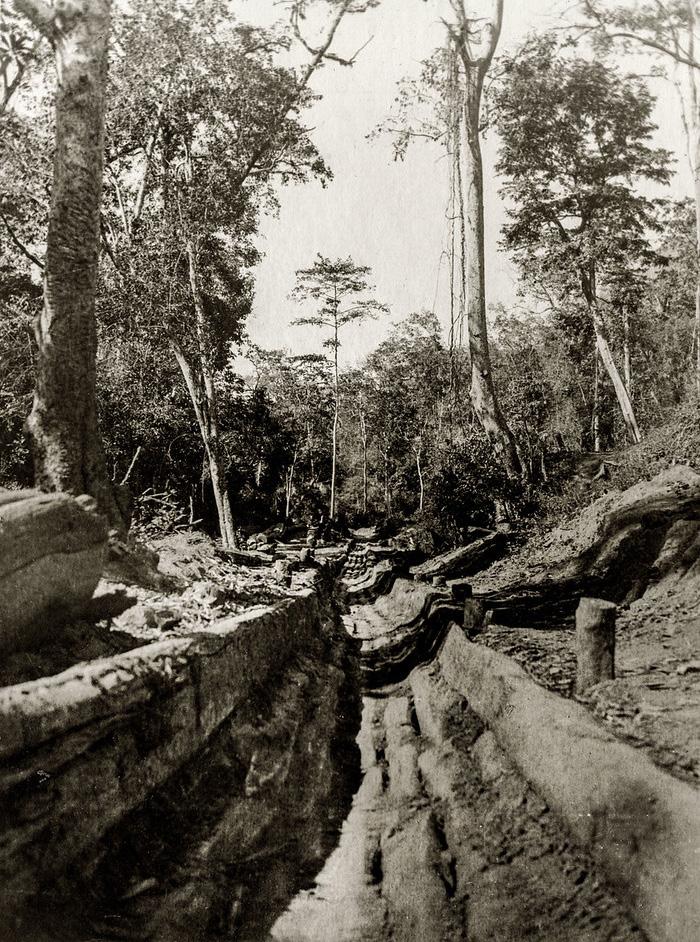

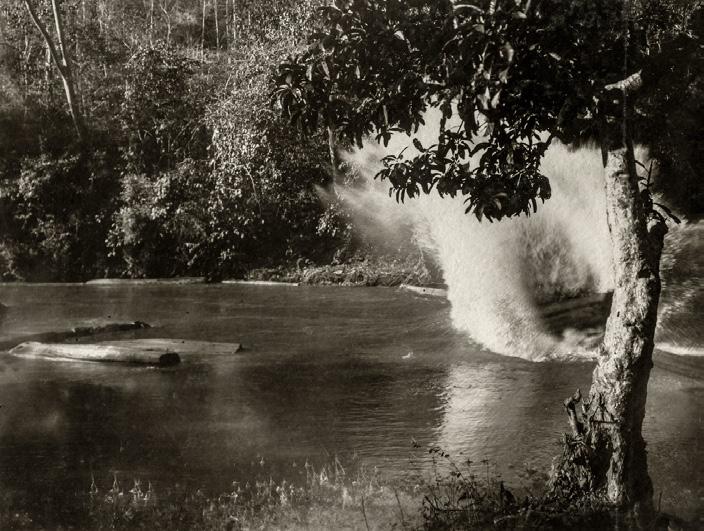

Ben Squire’s great-grandfather was a manager for the Bombay Burma Trading Corporation in the late nineteenth century. Mr P Marshall was tasked with the supervision of teak logging expeditions in the Burmese jungles. 34 Squire’s digital archive of Marshall’s photographic endeavours provides a parallel intimate understanding of settler colonial attitudes – where commercial interests materialised in the mobilisation of nonhuman figures for resource exploitation. 35 Figure 13 can be merited for its poignant encapsulation of the colonial gaze, as argued by this dissertation. The orchestration of the photography set: two labourers and the fruit of their labour – demolition of their indigenous habitats; documenting the façade of propriety and achievement. Consideration towards apertures, exposures, and visual compositions throughout the portfolio of images narrates the fruit from its systematic exploitation that was not only rationalised but also glorified. Where in England the shipbuilding industry created livelihoods for its citizens, the operations in this part of the world resulted in well-respected generational foresters becoming servants to British corporations and their abusive leadership. 36 The existence of a portfolio of images (Figure 14) – as opposed to a one-off memento – affirms the existence of a narcissistic power complex within colonial terraforming.

As Hutton discusses in the framework text, misinformation regarding material sourcing can lead to supply chain failures –driven in the case of Coastal Redwood (ipe) in the USA due to the arrogance of having “infinite supplies.” The shock of barren timber reserves was dealt with through the development of technologies for the preservation and improvement of other timbers. 37 In eighteenth-century England, Pepys identified suitable beech for the use of the Royal Navy – however rather than investing in the appropriation of the home-grown

ARYAN KAUL | TEAK AND OAK 30 29 ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 02./ A TERRAFORMED COLONY

Marshall’s Photography

Marshall’s Photography

FIGURE 13

FIGURE 12

Young Elephant in captivity, being forced to follow a colonial schedule of reproduction to ensure enough ‘tools’ remain for future extraction activities.

Source (Top and Bottom): Jonathan Saha

timbers, it was decided that they would look to deforesting other countries instead. 38 This is a trivial historic example of NIMBY at play on a global political scale. An example which has continued to manifest itself across centuries and cultural contexts, despite the atrocities discussed thus far.

32 31

Collage of Percival Marshall’s Photography (c. 1900)

FIGURE 14

02./ A TERRAFORMED COLONY ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION

Source : Jonathan Saha

38 Banbury, Shipbuilders of the Thames and Medway. p. 48

Machines of Empire 03./

Mechanisms of control are realised in a multi-scalar portrait. Lap joints with mortices create a laminated handshake of oak and teak, allowing a seamless transition between two worlds of cellular disparities. They are allowed room to grow – some empathy is shown towards their personalities. Tensioning the ropes carefully to ensure the swollen lignin doesn’t burst and cause a crack to ripple through the hull. Steam bending the geometry to make it do what he wants. Prying over the bracing to ensure it is behaving, while keeping records of minor divots and pleasant surprises – for next time. The wooden sailing vessel was truly a machine of empire. An instrument of expansion, each piece of ‘English’ joinery was employed in the conquest of new lands to be colonised. It allowed for control over trade routes, the imposition of military domination and the safeguarding of colonial loot. Outside of this dissertation, the machine would predominantly be adored for its economic engine – being the protagonist in romances of mercantilist policies. Superseding the Royal Navy’s extraction, they created trade monopolies and allowed these networks to funnel wealth back to imperial centres.

“The demise of the sailing vessel was certain,” after the development of a competitive steamship by 1865. 39 The advancement of the iron and steel industries was directly linked to the adoption of the steamship. The transition was curiously not compartmentalised. Once the appropriate infrastructure was in place, the screw propulsion; the iron construction; and the viable engine were all employed at once to create a division between large tonnage iron vessel production and

the crafting of small timber sailing vessels – hybrids were not explored. The most efficient long-distance carrier was the 1850s square-rigged wooden vessel, justifying its argument by dominating the ocean trade with its superior ratio of cargo space to tonnage. 40 Although the rational evidence is sufficient to not disagree with Greenhill’s argument, the exploration of control systems may be more viable in a timber construction methodology. This is perhaps because of the undeniable involvement of biological, or rather organic, processes at each stage of realisation – after all the elements being organised remain natural throughout the scales of application.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 34 33

Colonising Route Map FIGURE 15 Source : The Maritime Museum

40 Greenhill, The Ship. p. 3 39 Greenhill, The Ship. p. 20

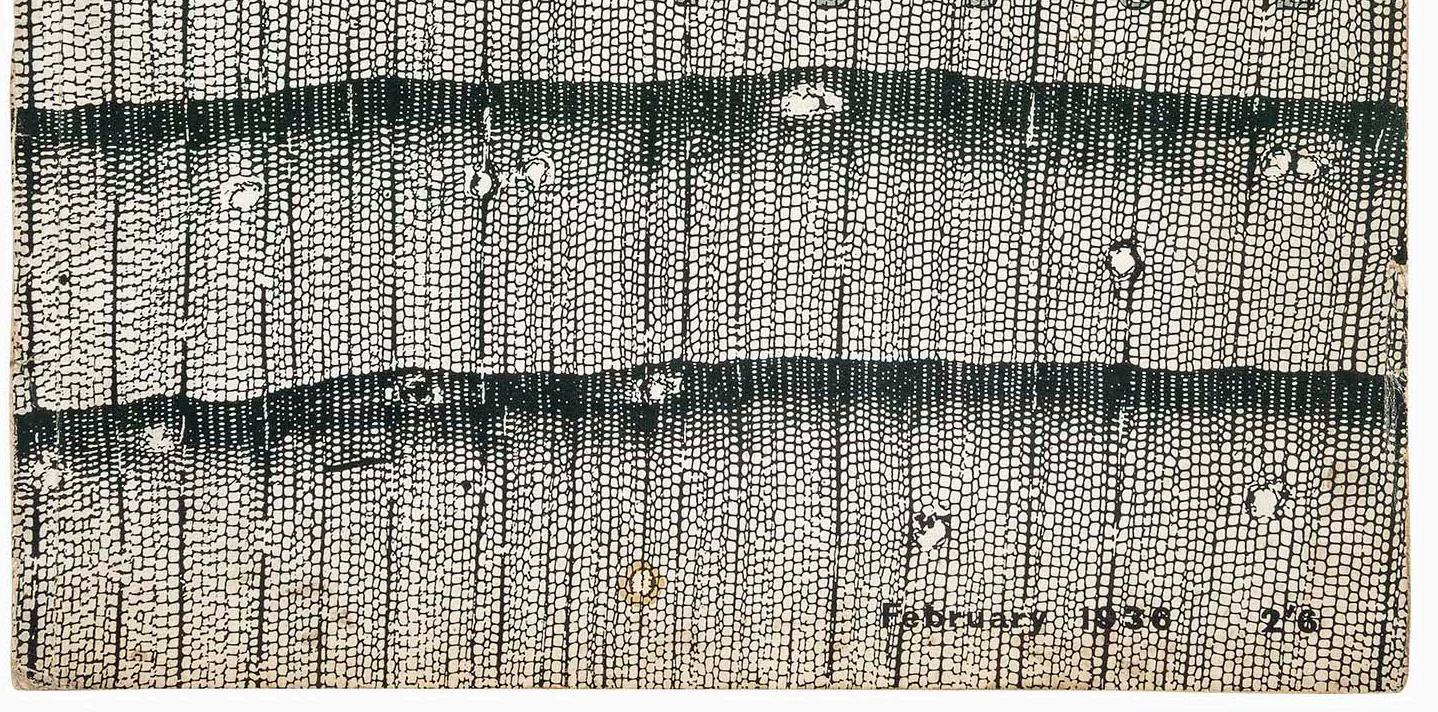

The boasting of ‘German-found scientific forestry practices’ in Burmese teak forests by the British seems to be the reason the global landscape signed up for the promotion of these timbers. 41 Despite the culmination of the Age of Sail providing the perfect opportunity for the abolition of colonial forestry exploitation, networks tempting capitalism had been established that are argued to have grown into neo-colonial warzones. Rushing past the many undulations that the use of teak and its implications on forest communities in Myanmar over the past two centuries would’ve taken – the spatial bounds of this research take us to the machine of the neocolonial empire.

Wooden sailing ships have found their parallels in the twentyfirst century as ultra-luxury goods: yachts, furniture, and decks. Although new, composite materials such as fibreglass are used to satisfy the structural and formal needs of most modern aquatic vessels (including parts of steel, aluminium and other plastics dependent on scale and function); there is an overwhelmingly use of teak in the internal cladding of decks, furniture, and cockpits. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) investigated the source of this variety of teak, whilst also considering the systemic imperial networks that may have been exploited. It appears the junta is stealing the fallen empire’s historic tactics. Through a continued revival of teak’s seductive allure, see Figure 16, the junta is able to fund itself and its oppression of democracy through the established global market for teak. The corruption in historic Royal Dockyards is a minuscule matter compared to the ethical violations being committed by the junta-controlled Myanma Timber Enterprise (MTE) and Western dealers of teakwood. It is plausible that these behaviours have been nurtured, encouraged, and amplified –

drawing a reciprocal landscape not only between Epping Forest and Burmese teak forests (pre-twentieth century); but also, between Myanmar’s twenty-first-century military regime and the shipbuilding practised in the British Empire during the Age of Sail.

16 The Architectural Review –1936 Timber Special Issue

A 2023 article in the Architectural Review (AR) by Neal Shasore critically examines the role of the Empire Marketing Board, the Timber Development Association (TDA), architectural agents such as the AR and the Royal Institute for British Architects, as well as many other individual actors, in the promotion of Empire timbers for use in interwar buildings. The Timber Trade Federation established the TDA in 1934 – where architectural journalist and design reformer John Gloag was appointed the public affairs director to stimulate a domestic demand for wood products. The consequent campaigns by the TDA gathered much attention in the field of architecture, with the AR publishing a special issue on timber in 1936.

: The Architectural Review

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 36 35 03./ MACHINES OF EMPIRE

FIGURE

Source

41 Saha, Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar.

“[Teak is] a part of nature that has been radically commoditised and thus turned into a dynamic aspect of human affairs.”

– Appadurai, 2014, p. 420

Conclusion

With the hope that Myanmar achieves a state of peace as soon as possible, there is scope for this research to be repeated in the emergent post-neo-colonial landscape. If evidence of sustainable forestry practices in Myanmar’s forests is available at this time, it would be crucial to consider the control each player in the supply chain has over the usage of this beautiful hardwood. Teak is etymologically based in its utility for construction – coming from the ancient Greek word for carpenter: tektōn. 42 I desire that the legacy of Teak – and the lives of the people and ecosystems that are intertwined with its growth – can be enhanced through human intervention rather than be corrupted. The current demand for the material presents layered paradoxes of resource mismanagement through the late-stage capitalist advertisement of Teak as a decorative finish, rather than as a gentle giant who is willing to work with you and achieve structural wonders that no other timber can – which is how I have come to appreciate it through the course of this dissertation.

It is at this point that the research converses directly with the built environment. The framework used thus far remains a prototypical exploration of a method of understanding the roots of components of architectural practice. Having undertaken this research, the dissertation discovered relationships between colonial and neo-colonial enterprise expressed through human–non–human agency; prevalence of concepts of terraforming; ironies masked within naïve colonial arrogance; but most of all the importance of bringing consciousness to the invisible networks, actors, processes, and techniques that intersect on a global scale in our practice. 43 This piece rests its case alongside the following question for a later date, borrowed from Irene Cheng (as posed in her work on visual culture studies):

[Could] investigating the enlarged and overlapping worlds that produce buildings as well as the worlds that buildings produce enable us to grasp the wider political ecologies in which architecture is enmeshed?

– Cheng, 2013, p. 179

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 38 37 ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION

42 Cheng, ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’.

43 Cheng, ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’.

Source : Unknown Burmese Artist (late nineteenth century) Folk Painting FIGURE 18

Relationship between a Log, the Elephant and the Mahout FIGURE 17

Source : Jacob Shell

List of Illustrations

Figure 1

Charles Middleton. Bill for the increase and preservation of His Majesty’s Wood and Timber, and supply of the Royal Navy therewith (1783). https:// www.rmg.co.uk/collections/archive/rmgc-object-511175.

Figure 2

Bob Hind. ‘HMS Victory Looking Stunning under Full Sail’. The News, 7 April 2020. https://www.portsmouth.co.uk/heritage-and-retro/retro/hms-victory-looking-stunning-under-full-sail-nostalgia-2531344.

Figure 3

Cheng, Irene. ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’. A Concise Companion to Visual Culture, 1 January 2021. https:// www.academia.edu/46868684/Architectures_The_Material_Politics_of_ Teak_in_Greene_and_Greenes_Bungalows_.

Figure 4

Aryan Kaul. Epping Forest, near the Lost Pond. 2023.

Figure 5

Verderer Paul Morris. ‘The Lost Pond, Epping Forest Forum’. Accessed 12 February 2024. https://eppingforestforum.com/the-lost-pond/.

Figure 6

‘Collection of Letters Signed by John Bradshaw (1602–1659)’, 20 March 1648. National Maritime Museum: The Caird Library and Archive. https:// www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-463426.

Figure 7

Charles Middleton. Bill for the increase and preservation of His Majesty’s Wood and Timber, and supply of the Royal Navy therewith (1783). https:// www.rmg.co.uk/collections/archive/rmgc-object-511175.

Figure 8

Aryan Kaul. Stakeholder Map. 2024.

Figure 9

Shasore, Neal. ‘Empire Timber: “Exotic Woods” in British Interwar Buildings’. Architectural Review (blog), 10 April 2023. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/empire-timber.

Figure 10

Shell, Jacob. ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant: Sovereignty, Reproductive Nature, and the Limits of Empire’. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 4 (4 July 2019): 1154–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 24694452.2018.1536534.

Figure 11

Charles James Barlow. ‘Orders and Reports of Proceedings of the Naval Brigade, Burma War 1885-1886’. National Maritime Museum, 1886. National Maritime Museum: The Caird Library and Archive. https://www.rmg.co.uk/ collections/archive/rmgc-object-492629.

Figure 12, 13, 14

Jonathan Saha. ‘Teak and Photography in Colonial Burma’. Colonizing Animals (blog), 23 March 2016. https://colonizinganimals.blog/2016/03/23/ teak-and-photography-in-colonial-burma/.

Figure 15

Charles James Barlow. ‘Orders and Reports of Proceedings of the Naval Brigade, Burma War 1885-1886’. National Maritime Museum, 1886. National Maritime Museum: The Caird Library and Archive. https://www.rmg.co.uk/ collections/archive/rmgc-object-492629.

Figure 16

Shasore, Neal. ‘Empire Timber: “Exotic Woods” in British Interwar Buildings’. Architectural Review (blog), 10 April 2023. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/empire-timber.

Figure 17, 18

Shell, Jacob. ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant: Sovereignty, Reproductive Nature, and the Limits of Empire’. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 4 (4 July 2019): 1154–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 24694452.2018.1536534.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 40 39

Bibliography

Addison, William Wilkinson. Epping forest, its literary and historical associations / by William Addison. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1945.

Appadurai, Arjun, ed. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. https://doi. org/10.1017/CBO9780511819582.

Atkinson, Daniel Edward. ‘Shipbuilding and Timber Management in the Royal Dockyards 1750-1850 : An Archaeological Investigation of Timber Marks’. Thesis, University of St Andrews, 2007. https://research-repository. st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/472.

Banbury, Philip. Shipbuilders of the Thames and Medway. Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1971.

Cheng, Irene. ‘The Material Politics of Teak in Greene & Greene’s Bungalows’. A Concise Companion to Visual Culture, 1 January 2021. https:// www.academia.edu/46868684/Architectures_The_Material_Politics_of_ Teak_in_Greene_and_Greenes_Bungalows_.

‘Collection of Letters Signed by John Bradshaw (1602–1659)’, 20 March 1648. National Maritime Museum: The Caird Library and Archive. https:// www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-463426.

Crimmin, P. K. ‘Searching for British Naval Stores: Sources and Strategy c. 1802 – 1860’. Great Circle 18, no. 2 (1996): 113–24.

Greenhill, Basil. The Ship – The Life and Death of the Merchant Sailing Ship (1815 - 1965). Vol. 7. 10 vols. National Maritime Museum, 1980.

HARRIS, TIM. ‘God’s Fury, England’s Fire: A New History of the English Civil Wars - By Michael Braddick’. Parliamentary History 28, no. 2 (2009): 301–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-0206.2009.00111_4.x.

‘How Cutting Down Trees Can Improve Forest Health’. Accessed 18 February 2024. https://www.nationalforests.org/blog/how-cutting-down-trees-canimprove-forest-health.

Hutton, Jane. Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements. 1st ed. Milton: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315737102.

Oster, Russell M. ‘Great Britain in the Age of Sail: Scarce Resources, Ruthless Actions and Consequences’, April 2015.

Pollard, Sidney, and Paul Robertson. ‘The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914’. In The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914. Harvard University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674436152.

Saha, Jonathan. Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Shell, Jacob. ‘The Enigma of the Asian Elephant: Sovereignty, Reproductive Nature, and the Limits of Empire’. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 4 (4 July 2019): 1154–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 24694452.2018.1536534.

Squire, Ben. ‘Photographs Taken by My Greatgrandfather in Burma’. Accessed 15 January 2024. https://www.bensquiresphotos.com/Burma.

Superintendent of Epping Forest. ‘The Condition of Epping Forest SSSI’. Epping Forest and Commons, 7 September 2015. https://democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk/documents/s54165/SEF%2041-15%202020%20targets%20 -%20Committee%20report%20September%202015%20FINAL.pdf.

Teak Forests (India). Copies of All Reports Which Have Been Made to the India or Home Government Respecting the Teak Forests in the Tenasserim Provinces. Accounts and Papers. Great Britain. Parliament. (Session 184748). House of Commons ; 654. London: House of Commons?], 2006.

‘The Line Upon a Wind: The Great War at Sea, 1793-1815’. Kirkus Reviews, no. 8 (2008).

Tripati, Sila, S. R. Shukla, S. Shashikala, and Areef Sardar. ‘Teak (Tectona Grandis L.f.): A Preferred Timber for Shipbuilding in India as Evidenced from Shipwrecks’. Current Science 110, no. 11 (2016): 2160–65. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/24908149.

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 42 41

Bibliography

Verderer Paul Morris. ‘The Lost Pond, Epping Forest Forum’. Accessed 12 February 2024. https://eppingforestforum.com/the-lost-pond/.

Webster, Anthony. ‘Gentlemen Capitalists : British Imperialism in South East Asia, 1770-1890 / Anthony Webster.’ British Imperialism in South East Asia, 1770-1890. Tauris Academic Studies, 1998.

‘Western Firms Certified as Socially Responsible Trade in Myanmar Teak Linked to the Military Regime - ICIJ’. 2 March 2023, sec. Latest News. https:// www.icij.org/investigations/deforestation-inc/myanmar-teak-trade-sanctions-military-regime/. -

ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION ARYAN KAUL | ROOTS OF EXPLOITATION 43