Timeless Art

Indigenous and Western Art Takes Center Stage on the Steamboat Art Scene

by Suzi Mitchell

DURING HIS LIFETIME, artist Fritz Scholder (1937–2005) shook the art world through his controversial interpretations of Indigenous American stereotypes. His influence on contemporary Indigenous and Western Art earned him a spot as one of the headline artists whose artwork will hang in the Steamboat Art Museum for a groundbreaking show scheduled to run from December 2, 2022 until April 15, 2023.

The New West: The Rise of Contemporary Indigenous and Western Art will join a growing number of exhibits in Steamboat Springs dedicated to Native and Western art. Earlier in 2022, the Tread of Pioneers Museum unveiled The Pleasant Collection of American Indian Art, and The Roland Reed Gallery opened with the largest collection of personal artifacts and authentic imagery by its namesake, the turn-of-the-twentieth century photographer.

Since the days of hunter gatherers from the Paleo-Indian period, Indigenous tribes lived off the land within the Yampa Valley. The Cheyenne, Arapahoe and Ute tribes followed in the footsteps of ancestors, lured to the area for its “sacred springs.”

In 2020, the Steamboat Springs City Council issued a proclama-

tion recognizing “the Indigenous Peoples of the Yampa Valley for their contribution to the land, water, plants, animals, and people of Steamboat Springs, Colorado.” Within the agreement is a commitment to share the history of the Indigenous people in the valley. Across town, residents and visitors can delve into stories of Native culture through artworks from past to present day now on display.

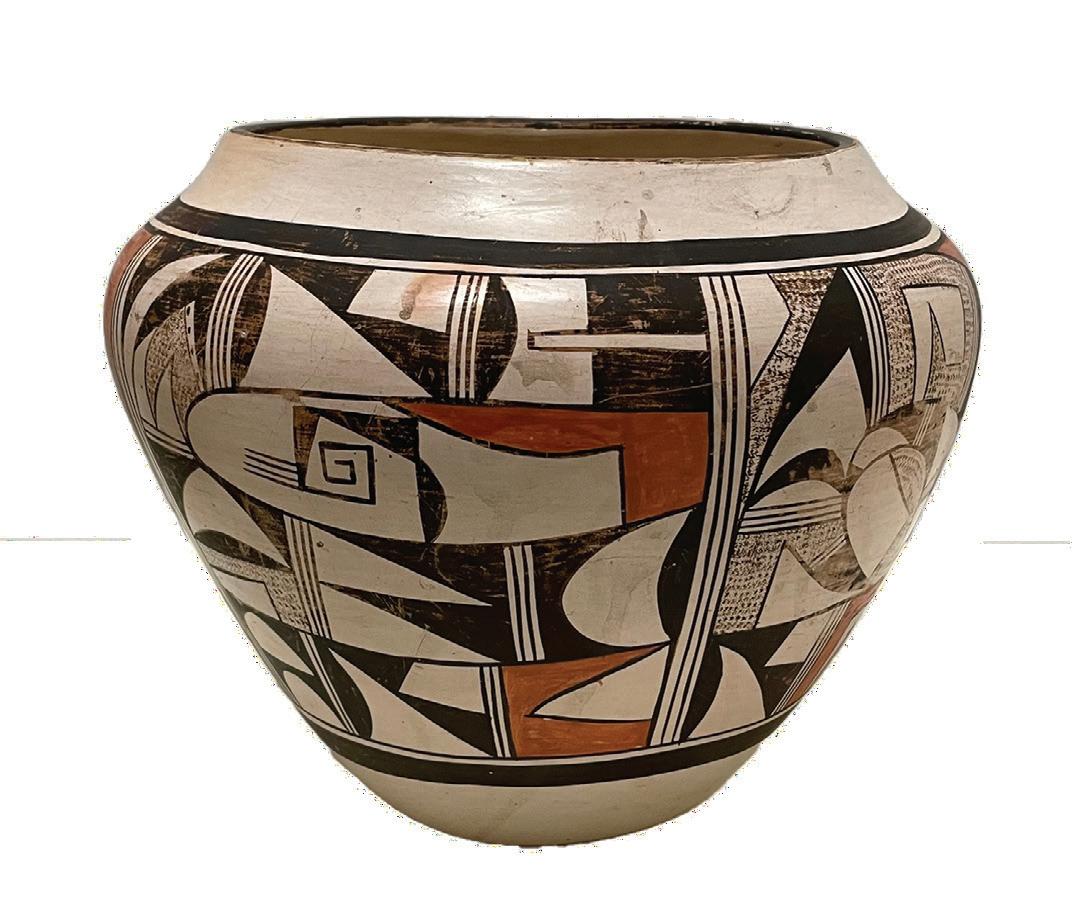

H.B. Pleasant, a Hayden resident in the 1930s, was transfixed by the cultural ways of Indigenous people and spent over 30 years visiting reservations across the Southwest. He engaged with families, tradespeople and artisans, and over time, purchased a tremendous

amount of artwork. Among his collection were arrowheads, pottery, beadwork, basketry, Navajo weavings, and photography by Edward S. Curtis.

Upon his death in 1951, the collection was given to his son, who died a decade later, at which time it became the property of estate executors and Routt County residents, Ferry Carpenter and his wife Rosamond, who was H.B.’s niece. Among the selection of pieces on display is pottery from the Pueblos of Hopi, Santo Domingo and San Ildefonso c. 1910–1940s, basketry from Pueblos of Hopi and Apache c. 1920s–early 1940s, and Navajo weavings c. 1890–1920.

“Few, if any, people from around here were connected with Native American tribes, much less appreciating and collecting their art,” says Belle Zars, a historian and family descendent. “He cared about the people. He (H.B.) felt they should be treasured and valued, and he just loved their arts and craftsmanship.”

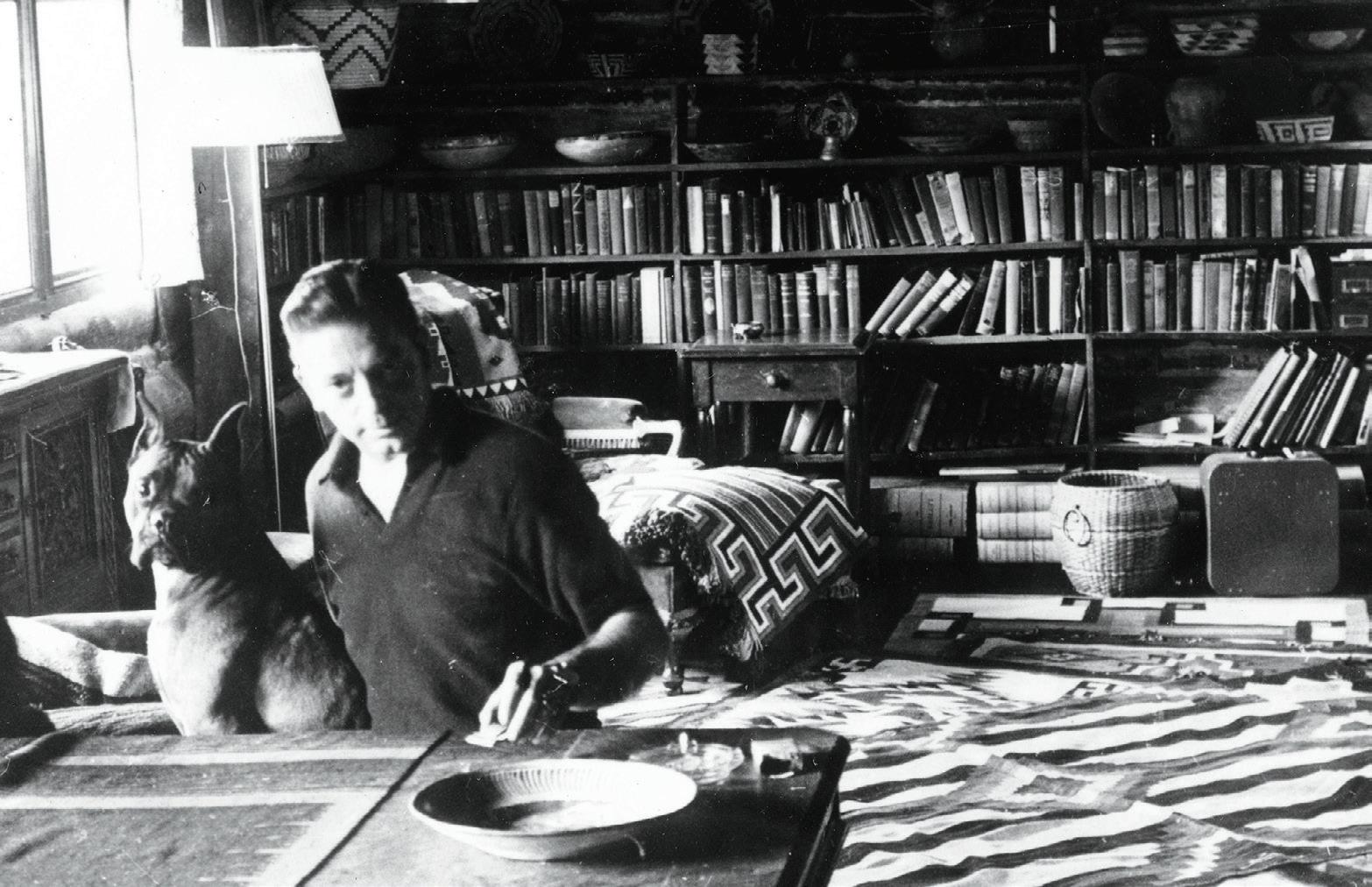

Around the same time H.B. Pleasant was visiting reservations, Roland Reed, a little-known photographer from Wisconsin, was also immersed among Indigenous tribes. Born 100 miles from Edward and four years earlier, Roland is the lesser known of the turnof-the-century photographers known as the pictorialists, and who dedicated much of his career to documenting the “lost ways” of the Indigenous people.

Unlike Edward, Roland was self-funded and self-directed. His imagery amounted to hundreds versus Edward’s reported 40,000 pictures. Roland limited his subjects to eight tribes with the intent that he gained their trust and respect to create a series of imagery using only authentic artifacts. When Roland was photographing members of the tribes, their traditional way of life had already been altered, but he wanted an accurate depiction of how things used to be. Today, his work, along with that of Edward, faces criticism for romanticizing a stereotype when many Indigenous people had already been forced from their lands and lifestyle.

“Roland’s photographs produce a feeling of timelessness and a reaction that they are telling a story much larger and broader than just what is depicted,” says Paula Fleming, a retired photographic historian and archivist at the Smithsonian Institute. “His images are absolutely some of my favorite views.”

Roland passed away in 1934 before he could complete his book, Reed’s Photographic Art Studies of the North American Indian. His belongings became the property of his cousin, Roy Williams, who took it upon himself to show Roland’s work by giving over 1,500

Art with Altitude

lecturesthroughouttheMidwest.UponRoy’sowndeath,hisentire collection of Roland’s artifacts was put in storage.

In spring 2021, Jace Romick, a photographer and gallery owner from Steamboat, got the chance to purchase those artifacts, including around 120 glass plate negatives. Like Roland, Jace is a perfectionist who now wants to embody Roland’s work as the late photographer intended.

“I feel an eerie sense of responsibility that in 200 years someone might be looking at an image I’ve printed from these plates,” Jace says. “I am compelled to do it right and represent Roland Reed withcompleteintegrity.Iwanttogivethisincrediblytalentedartist and historian a platform to showcase a way of life that has been forever altered”

Leticia Uzeta, a descendent of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana, is one of many Indigenous visitors to the Roland Reed Gallery since it opened in July 2022. “I hold great pride in my heritage and find it rare to see Native tribes portrayed in a way that honors them authentically,” she says. “These images depict their way of life before being stripped of everything. They are a great reminder of why we call ourselves ‘Niitsitapi,’ meaning ‘the real people’ Jace Romick’s knowledge and passion for not only the collection, but the tribes represented brought these images to life during my visit.”

While Jace's exhibit brings to light a way of life forgotten by most, Steamboat Art Museum's, The New West: The Rise of Contemporary Indigenous and Western Art, brings some of the greatest artists of the west together in one space. Seth Hopkins, Executive Director of the Booth Western Art Museum, in Cartersville, Georgia, assisted in the selection of pieces and artists to include in the exhibit.

“When our Board agreed that it was time to push our boundaries to a wider genre of western art, I reached out to Seth because of his expertise in this genre and the Booth’s extensive contemporary western art collection,” says Betse Grassby, the museum’s executive director. Until recently, the museum—which has a national reputation for exceptional exhibitions of living Western artists, has focused on Representational or Impressionist styles.

“We worked closely with Seth to develop this exhibition, starting with the early Indigenous instructors and teachers from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) and the subsequent influence they have had on the contemporary artists of today.” Betse says.

Among the works is that of Fritz Scholder. “He’s one of the star artists who kicked off the whole idea of Contemporary Indigenous and Western art,” Seth says. “He was an early instructor at the Institute of American Indian Art, one of the groups that