The Aspen Archives

by AwA

by AwA

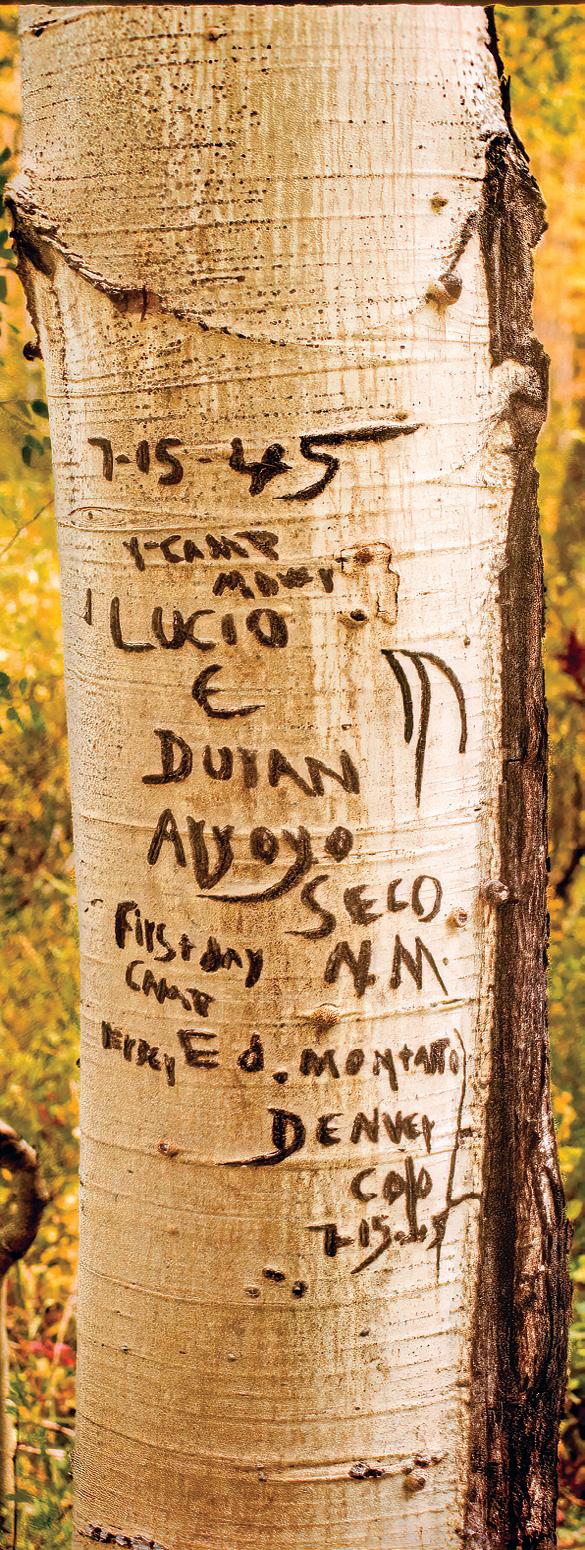

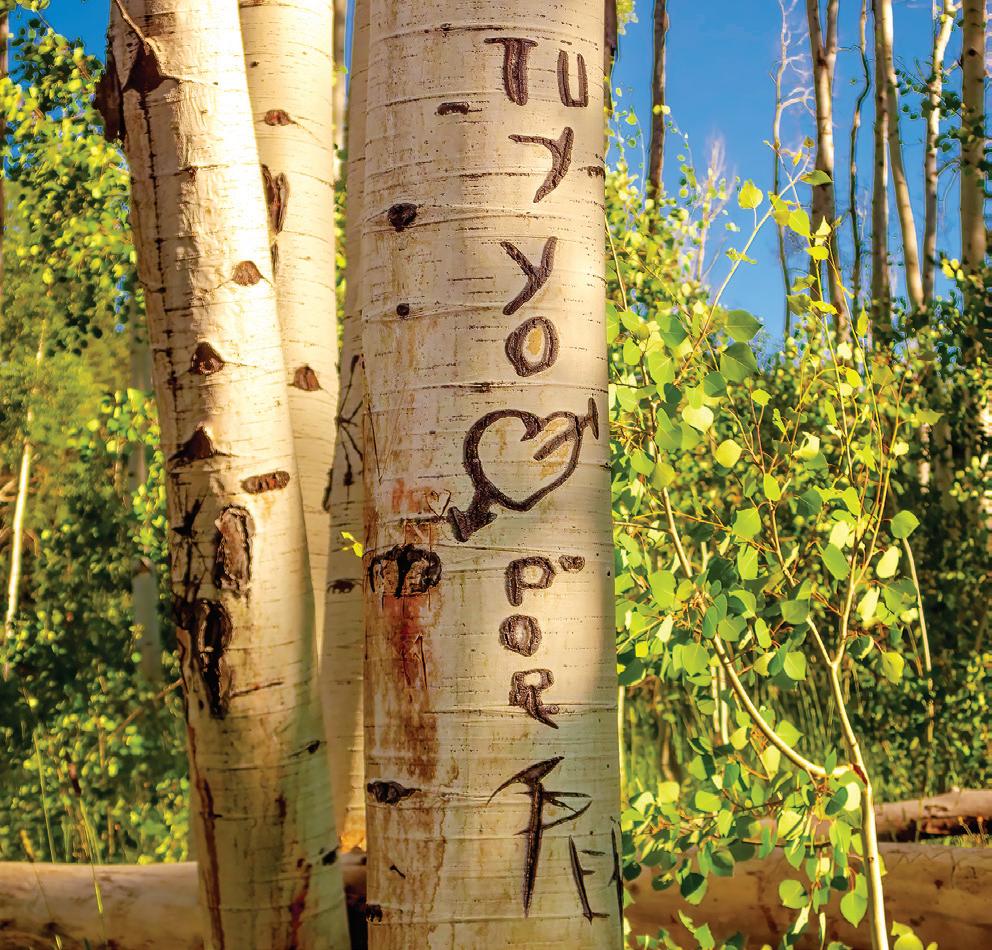

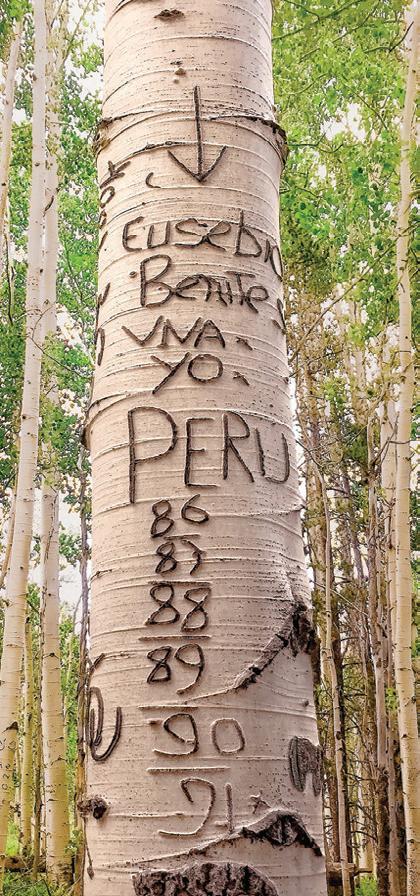

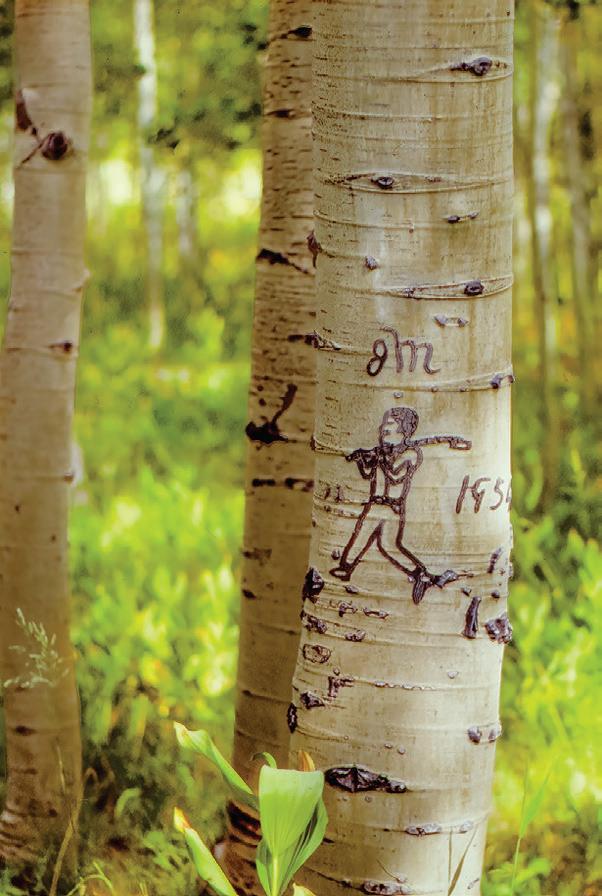

“HIDDEN HIGH IN the Colorado mountains, upon ephemeral canvases lies this exhibition’s point of departure,” writes Dr. Alison Krögel, Professor of Andean & Quechua Studies at the University of Denver, of her exhibit, The Aspen Archives. “Beginning in the late nineteenth century, sheepherders began to mark their passage through the Colorado landscape by inscribing words and images upon the trunks of high country aspens—arborglyph chronicles of loneliness and longing, but also poignant affirmations of friendship and celebrations of personal, regional, and national pride.”

The exhibit, showcased at the Tread of Pioneers Museum in Steamboat Springs, allows the visitor to step into a forest of history, filled with the voices of sheepherders and poets. The room is lined

with maps and photographs that tell the history and stories of sheepherding in Colorado and the Western US. Visitors can delve into the light and shadows of economy and mingling cultures. Learn about aspen ecology and wool processing practices in Routt and Moffat counties, as well as in highland Perú.

For the exhibit, new poems by two of Perú’s most well-known Quechua language poets, Pablo Landeo Muñoz and Olivia Reginaldo were commissioned and performed in Quechua with an English translation. Photography by Denver Post photojournalist RJ Sangosti—part of his Moving Wool collection—which chronicles aspects of the daily life of herders working in northwest Colorado lines the walls. Signage (bilingual in Spanish and English) in the

physical exhibit seek to contextualize some of the occasionally difficult to decipher cultural, historical, or political references contained in the arborglyph images and messages.

During the last forty years, sheep ranchers in Colorado and the Western U.S. have come to depend almost exclusively on the expertise and labor of Peruvian Quechua herders participating in the US H-2A temporary agricultural worker visa program. While from the 1880s–1970s this arduous and solitary labor was primarily carried out by Basque sheepherders from Spain and France, as well as by “Hispano” herders from communities in rural northern New Mexico or southern Colorado.”

Alison first became interested in studying the history of sheepherding in the United States twenty years ago when she was a graduate student of Andean Studies at the University of Maryland. “One summer, I was visiting family in Montana when an acquaintance of my sister asked if I knew that ‘lots of Peruvians who speak a language that isn’t Spanish work as sheepherders in the forests of

southern Idaho.’ I had just spent several months in Perú studying the Quechua language—the most commonly spoken indigenous language of the Americas—and wondered if these workers might be Quechua speakers. After a lot of inquiries, a rancher invited me to meet several of her Peruvian sheepherders working outside McCall, Idaho where the herders were happy to meet someone from the U.S. who could speak Quechua. I was incredibly interested to discover that much of the deep knowledge of ovine husbandry practiced in central Perú had led to the establishment of transnational labor agreements between U.S. ranchers and Peruvian workers.” During the pandemic, when her research projects in highland Perú were put on hold, Alison became interested in chronicling the memories of generations of sheepherders left inscribed on the aspen canvases of northwestern Colorado.

“A common misconception throughout the Rocky Mountain West is that sheepherders only work as seasonal employees during the summer months, or that they are undocumented workers,”

said Alison. Nearly all sheepherders laboring in the US today work under the auspices of the H-2A ‘Temporary Agricultural Worker’ program administered by the US Department of Labor with 3-year (often renewable) visas which allow them to work for a particular employer/rancher when it becomes difficult or impossible for the employer to find domestic workers to fill the position. In nearly all cases, sheepherders are employed to care for flocks on a year round basis, not only in the summer. Many herders spend the winter months in the Brown’s Hole/Brown’s Park region in far northeast Utah/northwest Colorado or the Red Desert region of Wyoming

Art with Altitude

caring for thousands of sheep on winter pastures. Many of the herders guide the flocks on foot and horseback from areas near Craig, Colorado towards these winter pastures, advancing several miles each day over a period of weeks. Historical photographs, Colorado newspaper archives, and grazing allotment maps document that this practice of transhumance—or moving livestock from one grazing ground to another in a seasonal cycle—has been carried out for as long as ovine husbandry has existed in northwestern Colorado.

The exhibit invites gallery visitors to consider the contexts in which nearly a century of arborglyphs were created. In Routt

county, the exhibit will be housed in the Crawford Community Room at the Tread of Pioneers Museum, which is dedicated to the artwork and artists that honor the history of northwest Colorado. “Although we certainly don’t advocate for graffiti on our forest trees as this can be detrimental to the trees’ health,” said Tread of Pioneers’ Executive Director, Candice Bannister, “we did want to provide a platform for Dr. Krögel to showcase the rich history, lifestyle, culture and people who created these particular aspen tree carving art forms and bring more awareness to the importance of the sheepherding industry in Routt County over the past century.”

Alison hopes The Aspen Archives exhibit will highlight the complex, transnational labor histories, economies, and sociocultural practices that have, for generations, linked many sheep ranching operations in northwestern Colorado with herders from rural high country communities in northern New Mexico, México, and Perú.

ELEVATE THE ARTS: Visit the Tread of Pioneers Museum to view the exhibit. If you are local, entry is free but consider a membership to support their programming. AwA