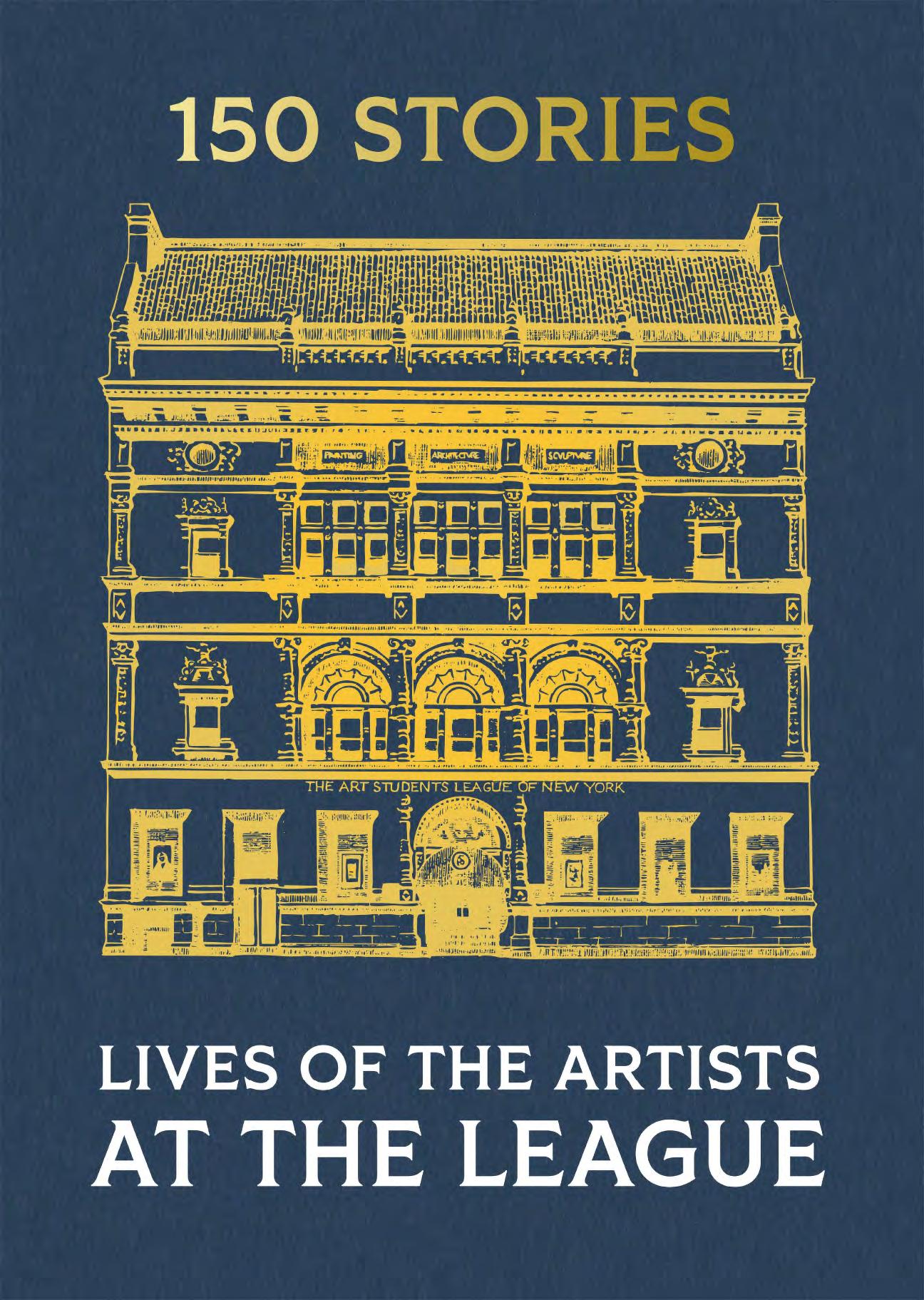

THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK

1875‑2025

150 STORIES

LIVES OF THE ARTISTS AT THE LEAGUE

EDITED BY STEPHANIE CASSIDY

As we celebrate the 150th anniversary of our beloved institution, I find myself reflecting on the journey that has brought us to this remarkable milestone. It is with great honor and gratitude that I pen this letter to you, not merely as the President of “the League,” but as a fellow artist and dreamer who has been profoundly touched by our collective art spirit.

The League has stood as a testament to the power of creativity. Our strength has always been our community. We have been more than just a place of learning: we have been a sanctuary for artists. Here in our halls, friendships have been forged, movements have been born, and the spirit of collaboration has thrived. This anniversary is a celebration of our achievements that weave throughout our rich history and the cultural landscape of American art.

As we look to the future, we commit to fostering an environment where art challenges and provokes thought and inspires change. Our goal is not merely to continue, but to evolve, ensuring that the Art Students League remains a vibrant hub for artistic excellence and expression.

Here’s to another 150 years where every stroke of the brush and every pencil put to paper adds to the masterpiece called the Art Students League of New York.

With deepest respect and admiration,

ROBIN LECHTER FRANK President, Board of Control, 2019–

Director’s

It is an honor to help lead an organization as venerable and revolutionary as the Art Students League of New York. It is an even greater privilege to have the opportunity to shepherd the Art Students League through its 150th anniversary. No art school in the history of this country has been as influential as the League, and no institution can look back on a history as storied as ours with the confidence it has remained true to its founding principles.

Since its founding in 1875, the Art Students League has been a home for and a beacon to all artists. The League has remained true to its mission of providing the highest-quality fine art education to anyone who wishes to pursue it. Through subsidized tuition for all students and a robust program of merit and need-based scholarships, I am proud to say the League turns away no artist—that anyone with a passion for art can find their voice here.

The League has long held the belief that only artists can teach artists. History, and our long list of accomplished alumni and instructors are proof that this founding principle is one that will carry us forward into the next century. The stories contained within this book are merely a fraction of the successes that the League has produced, and they are only a hint at the future successes to come.

The next generation of artists is studying at the League today. They are honing their skills in studios that have been populated by the great artists discussed in this book. As you read about their forebearers, I invite you to contemplate what the next one hundred and fifty years of League artists will produce. You may not know their names yet, but you soon will.

MICHAEL HALL Artistic/Executive Director

WHAT IS 150 STORIES?

150 Stories is a collection of short essays documenting the lives of art students and instructors at the Art Students League of New York over the last 150 years. The volume revolves around artists learning and teaching within its walls. The entries—organized chronologically by the subject’s first contact with the League—are not confined to discussions of classes, techniques, materials, or the elements and principles of design. Instead they offer vignettes that embrace a more expansive view of education. The League, like any art school, offers a realm for new inquiry into the generative relationships, formative ideas, and creative inflection points that can illuminate an artist’s lifelong evolution.

THE SUI-GENERIS ART SCHOOL

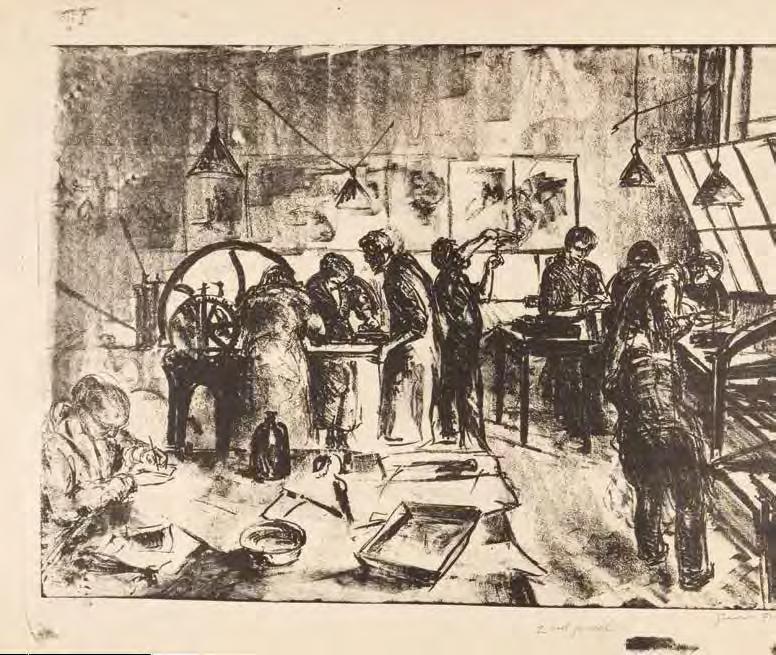

Throughout its history, the League has remained committed to offering instruction in the basic skills required to produce unique objects made by hand in drawing, painting, sculpture, and printmaking. Students have taken these skills with them to pursue varied directions of personal expression in nearly every field of visual art and design— arenas that have been considered together only in recent decades as the world of art has become less siloed.

From a research standpoint, the ASL takes work to pin down. It deviates from the familiar structures of American

higher education, starting with its open enrollment policy. Anyone can enter the building, register for a class, and, within minutes, sit down to sketch a model in a studio. Those who describe the League often point to what it lacks— entrance exams, prescribed curricula, prerequisites, syllabi, semesters, majors, grades, graduation, and diplomas—rather than what it offers—the recognition of students’ autonomy in pursuing and shaping their education. Students register by the month, decide how many classes to take, with whom to study, and whether to transfer from one instructor to another. There is no sequence to follow, no formal beginning or end, just choices from a list of classes. For

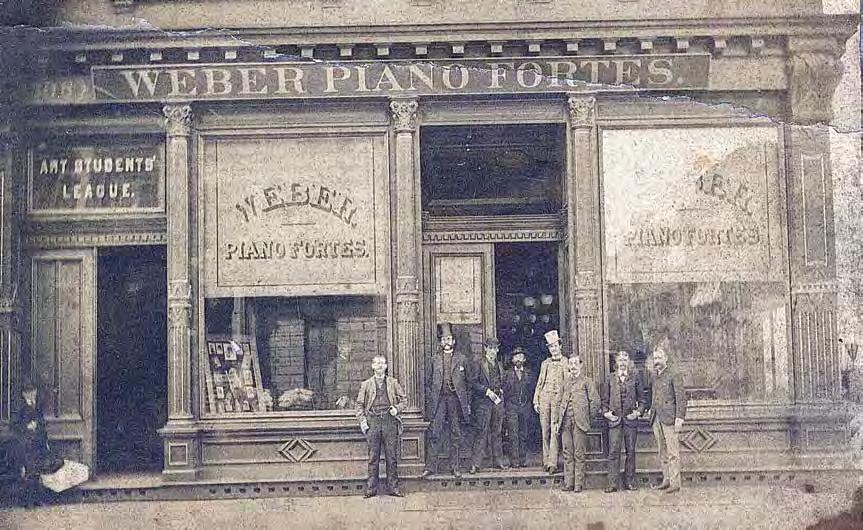

ABOVE: SUSAN N. CARTER’S CAST DRAWING OF THE VENUS DE MILO WAS ONE OF THIRTY BY STUDENTS PUBLISHED AS A PORTFOLIO IN 1872 TO RAISE FUNDS FOR THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF DESIGN’S SCHOOL. A STUDENT INITIATIVE, THE PORTFOLIO EVINCES A BUDDING ACTIVISM THAT, A FEW YEARS LATER, CULMINATED IN THE FOUNDING OF THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE. SEE PHOTOGRAPHS OF DRAWINGS FROM THE ANTIQUE EXECUTED BY THE STUDENTS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF DESIGN UNDER THE INSTRUCTION OF L.E. WILMARTH (NEW YORK: CLASS OF 1871–72, [1873?]) OPPOSITE: THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OPENED IN A SMALL STUDIO, THIRTY FEET SQUARE, ON THE TOP FLOOR OF WEBER’S PIANO FORTE SHOWROOMS ON THE SOUTHWEST CORNER OF SIXTEENTH STREET AND FIFTH AVENUE. THE LEAGUE’S SIDE ENTRANCE APPEARS AT THE FAR LEFT, C. 1882. PHOTO: CORLISS & BANCROFT, COLLECTION OF SUSAN HERZIG & PAUL HERTZMANN, SAN FRANCISCO

generations, students have dropped in for late afternoon sketch classes, signed up for a weekly lecture series on human anatomy, or enrolled in a workshop on portrait painting that can last a day or a week. This à la carte approach to education encourages movement between studios. The open admissions policy makes for a fluid student body while also helping to replenish the turnover of shortterm entrants. Nevertheless, devoted cohorts have formed around instructors in studio classes, with some students staying for years. With little need to filter, regulate, and measure students and their learning, the League’s administrative staff has remained lean, student-run, and economical for much of its history.1

Over the decades, the League’s appeal has remained steady. It has weathered cataclysmic global events that prompted sudden downturns

in registration—including the Great Depression, the Second World War, and the COVID -19 pandemic. The low tuition and low-friction signup have kept it nimble and competitive. As BFA and MFA degrees became the norm for artists during the postwar period, the League remained steadfast as a nonaccredited and economical alternative in an education market that has become increasingly exclusive, expensive, and contentious, recently contributing to the closure of several notable art schools. 2

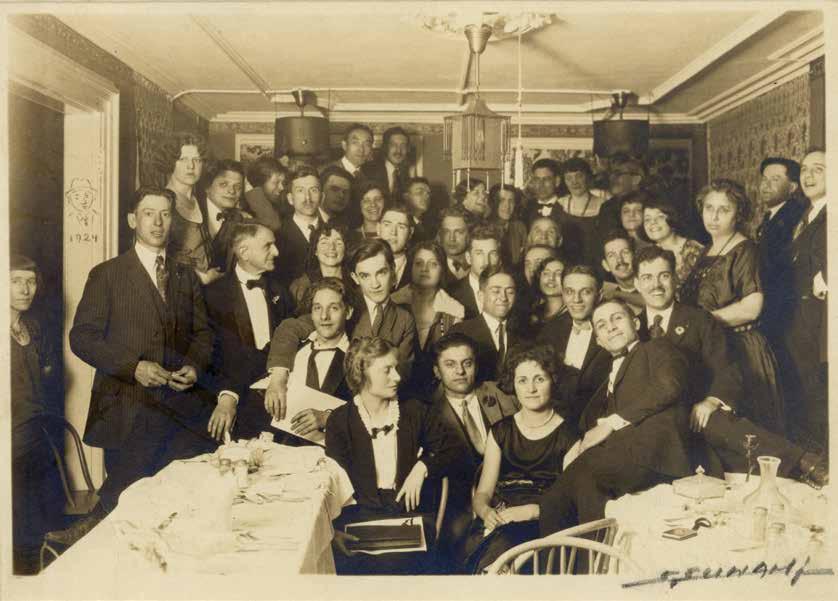

FINDING COMMUNITY

Equally important to students’ forging individual paths has been a community ethos pulling them together as a collective. The first version of the League’s constitution, printed in late 1875, reveals that affiliating as a community of students was not just

a priority but its very purpose: “The object of this Association shall be the attainment on the part of its members of a higher development in Art Culture, the encouragement of a spirit of unselfishness and true friendship, mutual help in study, and sympathy and practical assistance (if need be) in time of sickness and trouble.”3 In other words, before the League became a school, it took the “exceedingly humble” and provisional form of a grassroots learning group for art students. 4

BREAKING THE MOLD

The catalyst for this organized student action, perhaps the best-known part of the League’s origin story, was the anticipated closure of the National Academy of Design’s schools in the fall of 1875. The Academy’s council had been struggling for several years to cover the cost of its free schools. As enrollment grew, academicians disagreed over the school’s need for greater oversight and resources. While the Academy’s school garnered support from the New York press during the early 1870s, its annual exhibitions featuring academicians’ artwork elicited more criticism than praise.5 In May 1875,

the council adjourned for the season without an official announcement about the fall, leaving nearly 250 students in limbo and uncertain about the school’s survival.6 Their instructor, Lemuel Wilmarth, encouraged their idea to form “an association for mutual help and criticism.”7 In helping to form a “league,” the name proposed by student Theodore Robinson,8 Wilmarth shifted away from the model of an art academy to “conduct the various classes on the principle of the Parisian ateliers.”9 This “atelier system” was simply a collection of studios, each overseen by a different artist, encompassing “many methods of instruction.” Those studios held seasonal public exhibitions, allowing a student to “judge for himself [/herself], draw his [/her] own conclusions, and lay out his [/her] own course” of study.”10 In this arrangement, the art student is empowered with choice.

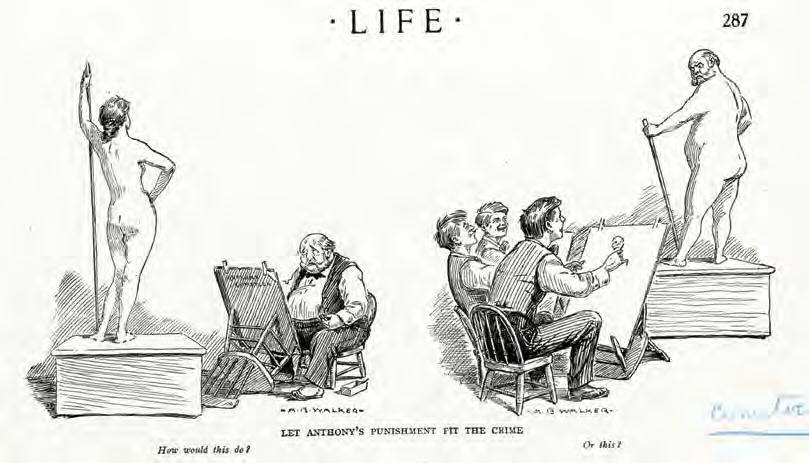

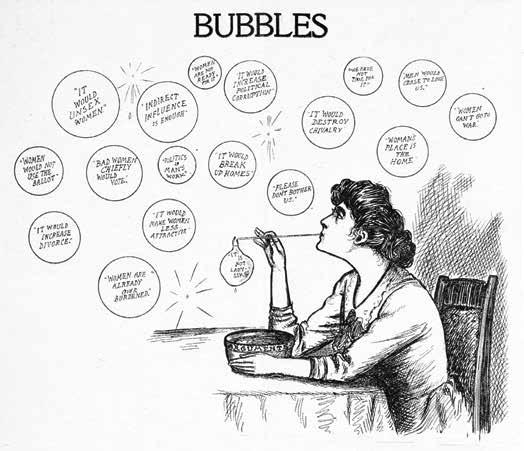

The League’s founders adopted and continued to modify this thriving educational alternative from Paris, recognizing in its open and democratic features an antidote to their disenfranchisement at the National Academy. “[S]tudents themselves, unable to rely on the leaders of the profession,” art historian Lois Marie Fink has observed, “began to take charge of their own education.”11 The circumstances also provided the fertile ground for women students to demand the League fully commit to co-education. To that end, the ASL’s constitution enfranchised women

art students and provided that they would serve on its governing Board of Control.12 A columnist for The Art Union wrote in 1885, “The organization in its construction has always illustrated an ideal equality,” unusual for its time.13

PARSING THE LIST

Lists of names have played a surprising role in preserving and relaying the Art Students League’s history. One of the earliest examples, a list of current and past instructors, appeared in the simple accordion-folded course catalogue of 1901–02. A few years later, the League published its first list of notable alumni. Over decades, these lists became a mainstay of every printed course catalogue, growing from a few dozen names to nearly a thousand. An easy means of recordkeeping, their utility is obvious. They testify to the stature of its teaching corps of artists and alumni, a powerful shorthand for the ASL’s

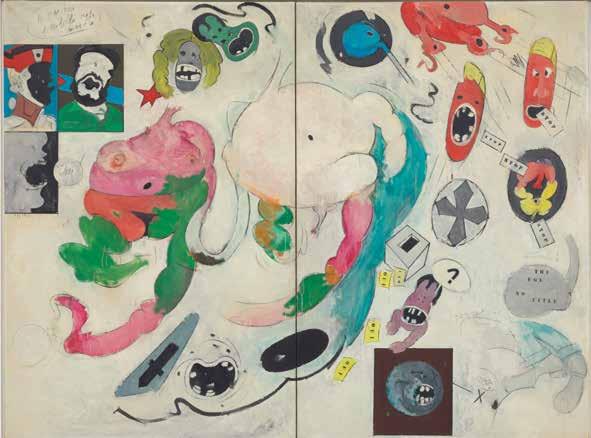

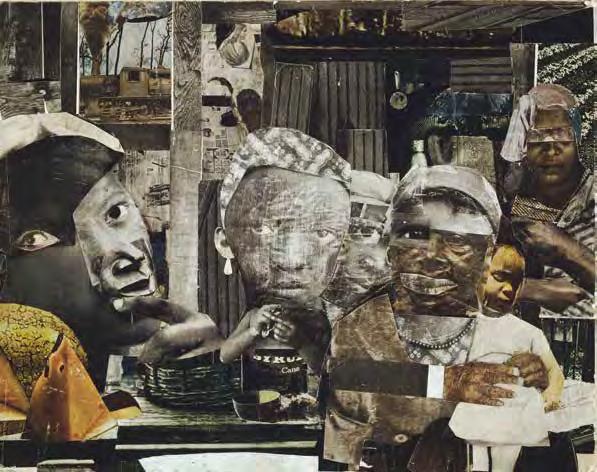

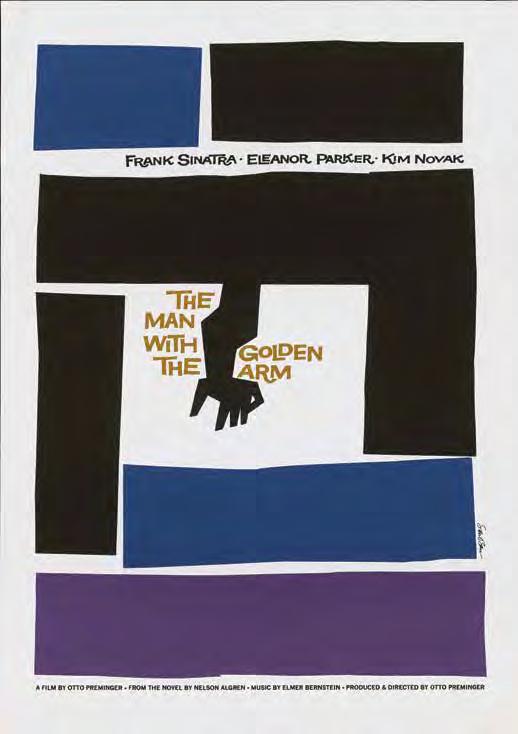

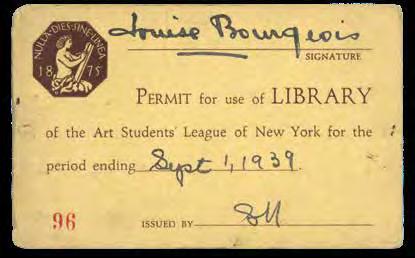

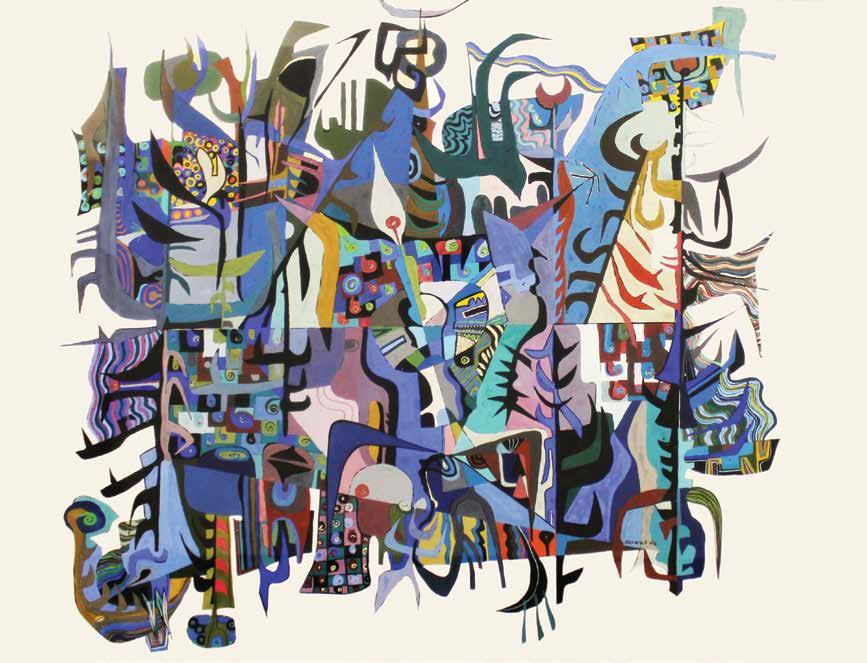

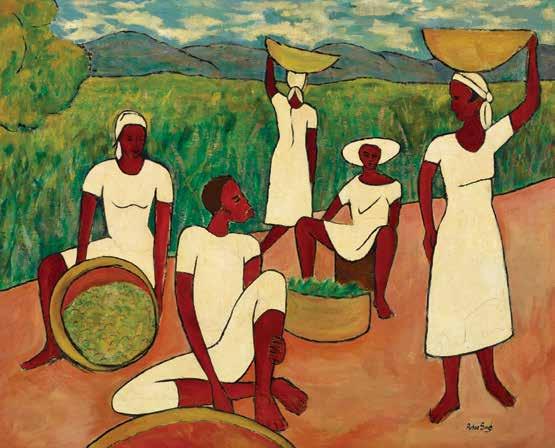

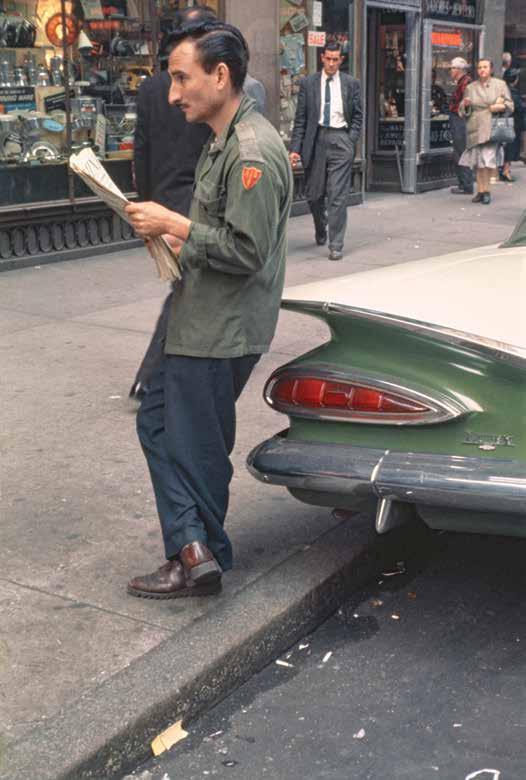

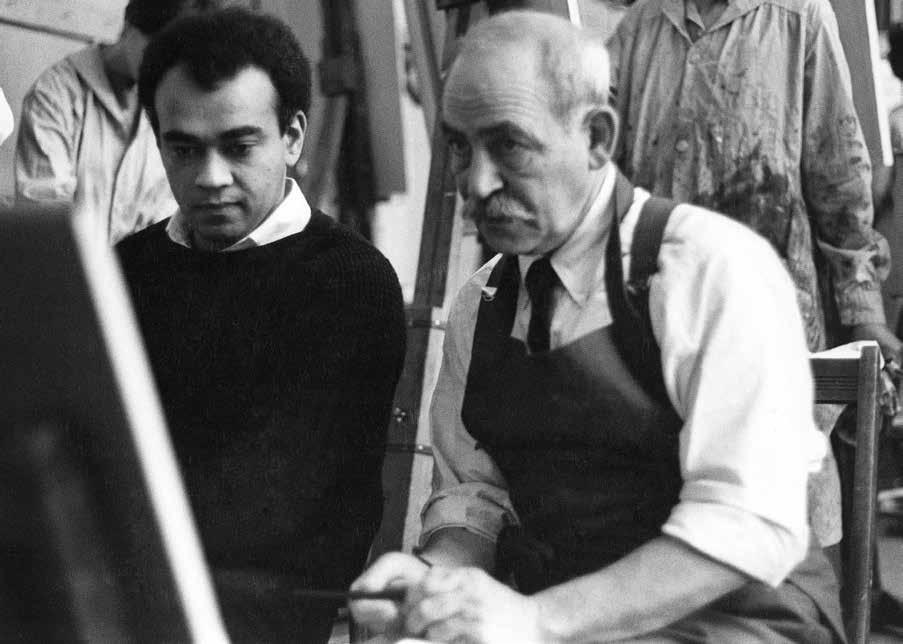

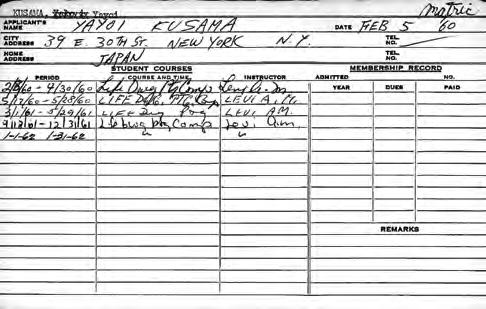

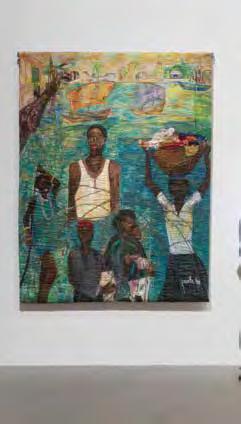

historical significance as an art school. 14 Yet, those long columns of names, alphabetically arranged, are ahistorical. They offer no chronological, thematic, or analytical framework. They reveal no relationships, nor do they suggest connections to a specific kind of art. Moreover, only a handful of these names have found a place in its institutional narrative. To be fully understood beyond the marquee names, these lists depend upon a reader’s familiarity with an art historical canon and well-versed recognition of artists from the past, many of whom are now obscure. Still, a list can be suggestive and ripe for exploration. The Art Students League’s list and its expanded cultivation over the last few years form the basis for the 150 Stories project. My rethinking about the list was prompted by the Museum of Modern Art’s inclusion of a newly acquired painting by Haitian-born Hervé Télémaque,

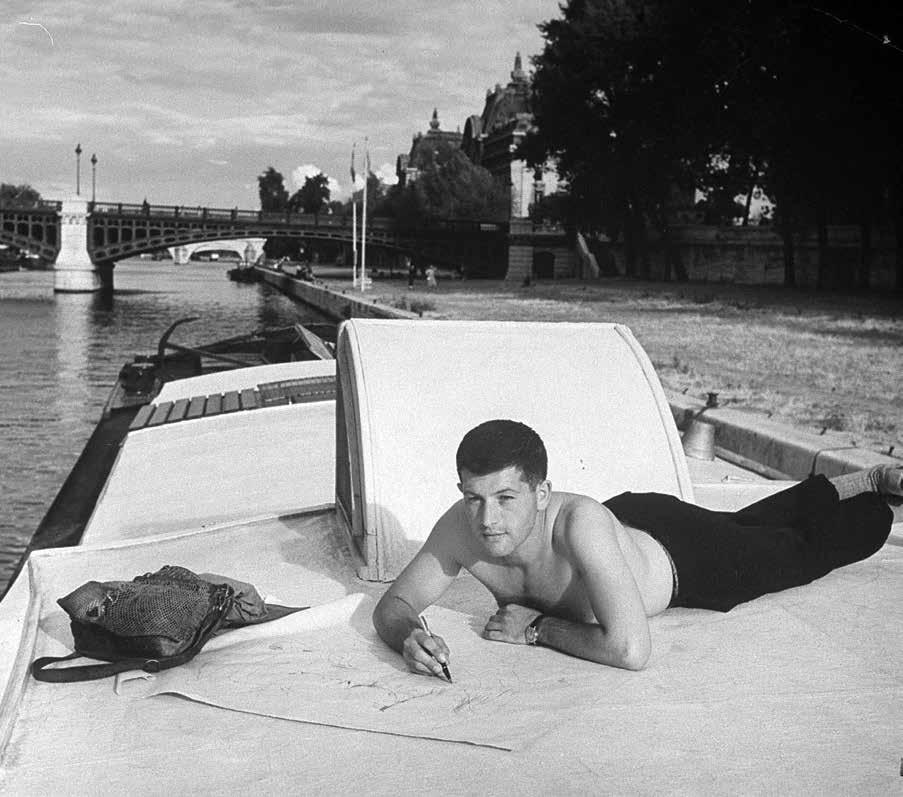

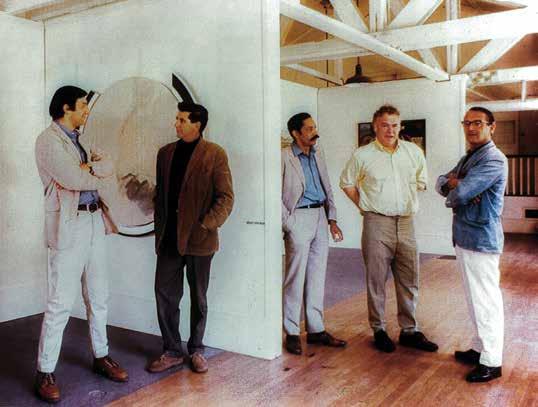

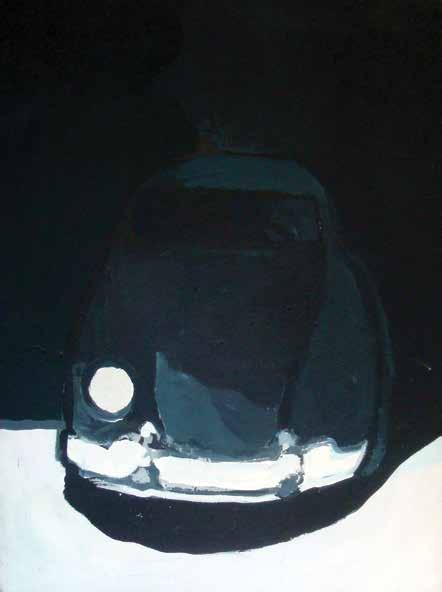

No Title (The Ugly American) (1962/64), in their collection rehang and reopening in October 2019.15 Unlike several other familiar artists in the gallery, his name was new to me. A Black Caribbean Francophone, Télémaque arrived at the League in the fall of 1957 at age twenty and studied for three years with Julian E. Levi, who came to regard him as one of his most exceptional students. In New York, “[t]he racism was very strong,” Télémaque recalled, and, unable to rent a studio, he departed for Paris. The work No Title (The Ugly American) was part of a “reckoning with my time in America,” he explained, looking back at age eighty-one, and “has some of the flavor of New York City and all of the problems I had there as a negro boy from Haiti.” Télémaque’s art and this formative period of his life reveal complex themes of immigration and race that have yet to be examined and brought to bear on how we understand the League

during the postwar period.16

Ann Temkin, MoMA’s MarieJosée and Henry Kravis Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, told an audience about the rehang, “It’s our job to present these different histories, and these different communities, and these different moments, and these different approaches…to modern art that retain the same…sense of excellence and…quality,” The “overhaul of the curatorial thinking of the museum,” she admitted, “prompted soul-searching” but ultimately could help reawaken dormant works and broaden the presentation of MoMA’s vast, largely unseen collection in fresh rotations.17 Similarly, how many unique narratives, like Télémaque’s, are buried in the League’s long list of alumni and instructors? What might they reveal about its history?

Several months later, the COVID -19 pandemic provided an unexpected and extended opportunity to consider these questions and revisit the list. Digitized reference works and new curatorial and academic scholarship helped accelerate our discovery of artists whose names could be added across media, geographies, and centuries. Google searches revealed the newly minted collection databases of museums and galleries, large and small. Tracing the lives of ASL alumni from previous generations in online archives became possible. Finally, we could follow the careers of living alumni globally and in real time.18 With names tagged

ABOVE: AMERICAN FINE ARTS SOCIETY BUILDING. POSTCARD, UNDATED (BEFORE 1921). COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR OPPOSITE: ARCHITECT HENRY JANEWAY HARDENBERG BASED HIS DESIGN FOR THE AMERICAN FINE ARTS SOCIETY ON THE MAISON DE FRANÇOIS I, WHICH WAS CONSTRUCTED IN MORET-SUR-LOING, FRANCE IN 1528. FALLING INTO DISREPAIR, THE BUILDING WAS SOLD IN 1826, “TRANSFERRED IN FRAGMENTS” FORTY MILES TO PARIS, RECONSTRUCTED AND RESTORED AT THE CORNER OF RUE BAYARD AND COURS-LA-REINE. EUGÈNE ATGET, MAISON FRANÇOIS, COURS-LA-REINE, 1899. ALBUMEN SILVER PRINT, 7 1/8 × 8 11/16 IN. THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES, GIFT OF MARY AND DAN SOLOMON IN HONOR OF JIM CUNO, 2022.45.61.5. DIGITAL IMAGE COURTESY OF GETTY’S OPEN CONTENT PROGRAM.

with metadata, a once static paper list transformed into a dynamic relational database, and this book project was born.

HISTORY OUTSIDE THE FRAME

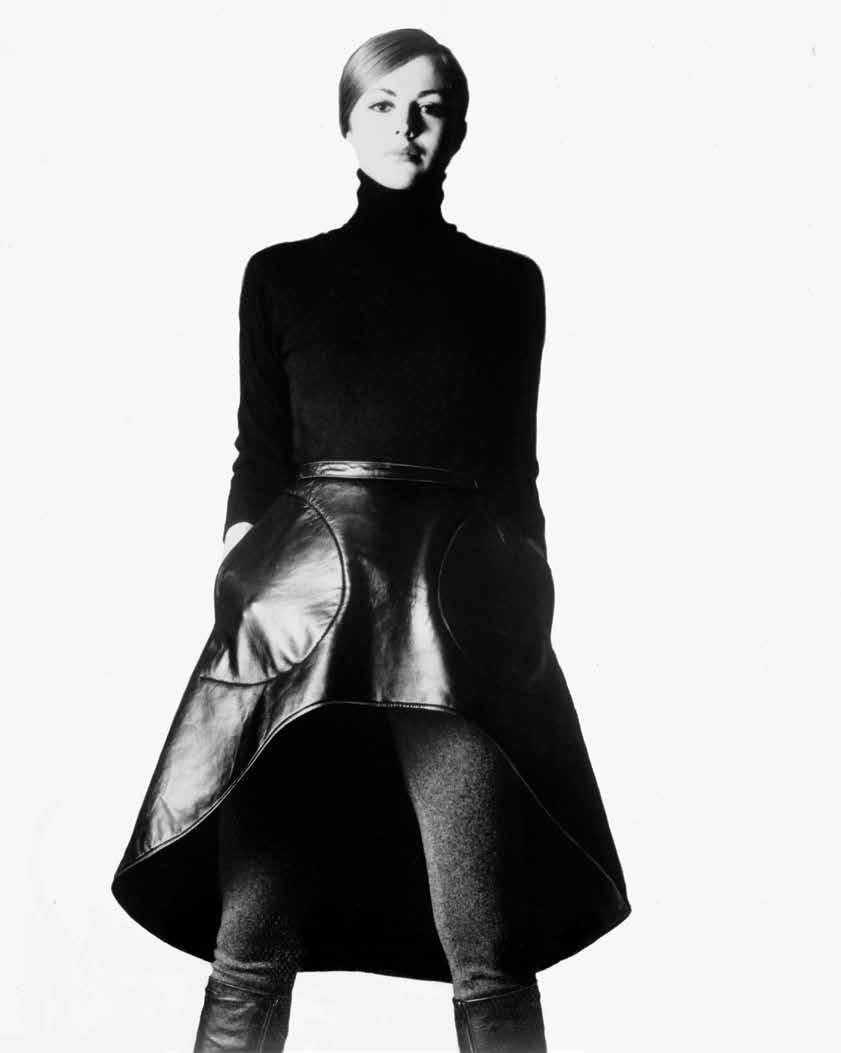

The Art Students League has traditionally celebrated its major anniversaries with exhibitions.19 The first shows were large, encompassing, in-house affairs. They mixed established artists with current instructors, long-term members, and up-and-coming students in the first-floor galleries of the American Fine Arts Society building, the ASL’s residence on West 57th Street since 1892. The exhibition in 1900, for example, included 548 works.20 The next, in 1925, was nearly as large, at 480 works. In a notable postwar shift, commemorative shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1951 and Kennedy Galleries in 1975 offered taut curated surveys of 75 and 101 works, respectively. American Masters from Eakins to Pollock, organized by the League, presented 25 works by 25 artists in 1964, and American Masters: Art Students League, an exhibition circulated in 1967–68 by the American Federation of Arts (AFA), was pared down to 45 works.21 These smaller surveys became less comprehensive, narrowing their focus to a subset of the list, “masters,” largely white male artists, and favoring painting over other media. Like most exhibitions of the period, these shows adhered to a midcentury art historical canon that reflected neither the League’s more diverse student body nor the many artists who forged influential careers outside of its orbit in a range of different media and various

commercial fields of visual art.

The League is a school and not a museum, though a good measure of its reputation is tied to the esteemed artwork and careers of affiliated artists. Art—its creation, history, and appreciation—is the point of the League’s agenda. But a painting or sculpture is, at best, an indirect artifact of that “League education” and inevitably reflects an amalgam of other influences. As for careers, many artists’ biographies mention the League, contributing to its renown. Most of these references turn out to be perfunctory.22 Few studies delve deep enough to explain precisely how time studying or teaching there influenced an artist. Much about what happened educationally within the Art Students League, to say nothing of its chronicle as a landmark institution, remains ripe for exploration.

LIVES OF THE ARTISTS AT THE LEAGUE

150 Stories takes an artist-first approach to exploring the League’s history and documenting its impact. Grounded in first-person accounts and archival research, these succinct entries describe artists’ early efforts in learning to make art. They conjure the instructors’ unwritten teachings passed down through oral histories. They situate the art student in a matrix of formative relationships with mentors, friends, collaborators, and, in some cases, romantic partners. They reveal the side hustles that paid tuition and covered living expenses in New York City. This anthology includes artists who embraced traditional materials, techniques, and modes of expression, aligning themselves with established stylistic lineages, as well as those who, just as vigorously, challenged, dismantled, and diverged from all of those conventions in search of the new. Some note the aspirations that drew students to the League, the motives for their departure, and, for others, the reasons for their return to study again or to teach. In this volume, the Art Students League’s history is not just one story but many.23

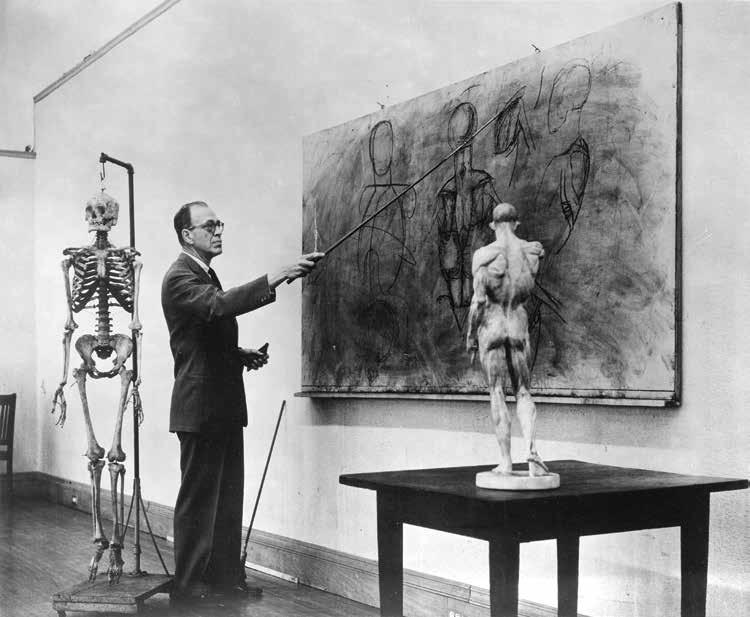

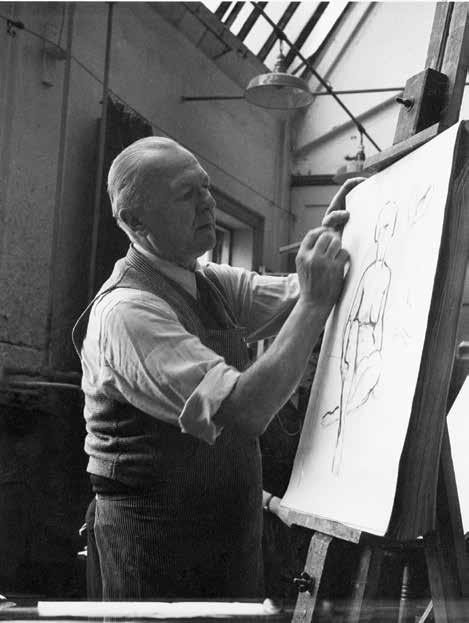

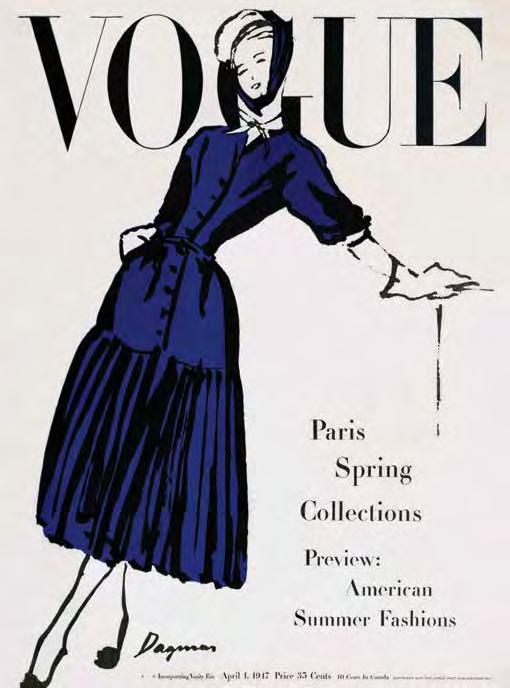

T he artists selected for this book traverse the cultural hierarchy, including celebrated painters, sculptors, and printmakers alongside commercial artists who designed textiles, furniture, dinnerware, and jewelry boxes and those who made fashion illustrations, comic art, posters, and field guides. It includes a line of artistic anatomists and

drawing instructors stretching from the 1880s to the early 2000s and those who captured life through the lens of a camera. Museum and gallery founders, collectors and curators also appear, as do new names surfaced, researched, and exhibited by the recent transformative efforts of scholars and curators to create a fuller, more inclusive art history. The 150 Stories volume, with its subtitle a nod to Giorgio Vasari’s influential text Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), contains only a sliver of the thousands of possible artists who could be included. It marks a beginning and provides scaffolding for the ongoing discovery and embrace of more League stories in the future.

Unlike Vasari’s classic, the lives in this volume are captured by many writers, nearly 140, a fittingly collective effort to create a snapshot of a collective. Six extended essays offer perspectives on public controversies that involved the League, a few of its distinctive customs, and, of course, its Woodstock Summer School. Connected by their shared references, these entries reveal a mosaic of the aesthetics, politics, education, and community that testifies to the Art Students League’s inimitable role in American art.

150 Stories pays tribute to the Art Students League of New York as a place and as an enduring idea. It is dedicated to the next generation of dreamers.

STEPHANIE CASSIDY

1. The Art Students League’s lean operational model has been crucial to its long-term fiscal viability. In a recent essay, Derek Thompson discusses a trend identified by many others over the past decade: administrative bloat in higher education driving up tuition and bringing with it “too many administrative functions [that] can make college institutionally incoherent.” See Derek Thompson, “No One Knows What Universities Are For,” The Atlantic, May 8, 2024, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/ archive/2024/05/bureaucratic-bloat-eating-american-universities-inside/678324.

2. On the National Academy of Design’s challenges that led to the closure of its school, see Robin Pogrebin, “Branded a Pariah, the National Academy Is Struggling to Survive,” New York Times, December 22, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/23/ arts/design/23acad.html and Emily Conklin, “New York’s 200-year-old National Academy of Design Won’t Ever Reopen,” The Architect’s Newspaper, July 12, 2019, https://www.archpaper.com/2019/07/national-academy-of-design-wont-reopen/. For an in-depth analysis of the University of the Arts closure, see David Murrell, “The Inside Story of the University of the Arts’s Stunning Collapse,” Philadelphia, August 8, 2024, https://www.phillymag.com/news/2024/08/08/uarts-philadelphia-closure/. For a general overview of recent art school closures, see Rick Seltzer, “Art School Shakeout,” Inside Higher Ed, February 6, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/02/07/ art-schools-show-signs-stress-what-can-liberal-arts-colleges-learn and Kathryn Palmer, “Enrollment Declines Threaten Small, Independent Art Colleges,” Inside Higher Ed April 8, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/institutions/specializedcolleges/2024/04/08/enrollment-declines-threaten-small-independent.

3. “Article II,” Art Students’ League, Constitution, By-Laws and List of Officers, Committees and Members ([New York]: Art Students League, 1875), [5]. As part of its incorporation in 1878, the League’s board revised its objective to be “First,—The establishment and maintenance of an Academic School of Art, which shall give a thorough course of instruction in drawing, painting, and sculpture. Second,—the cultivation of a spirit of fraternity among Art Students.” Art Students’ League Constitution and By-Laws ([New York]: Art Students League, 1878).

4. “An Art Students’ League,” New York Times, July 26, 1875, and “The Art Students’ League: Its Twenty-fifth Anniversary to be Celebrated This Week,” New-York Tribune, May 6, 1900.

5. For criticism of the National Academy of Design’s annual exhibitions, see “Culture and Progress at Home,” Scribner’s 2, no. 3 (July 1871): 331; “The Academy of Design,” New York Times, April 20, 1873; “Fine Arts,” The Nation 16, no. 412 (May 22, 1873): 358; “The Academy of Design,” New York Times January 11, 1874; “Art,” Atlantic Monthly 34, no. 204 (October 1874): 508. For praise of the National Academy’s school, see “The National Academy of Design: Fourth Winter Exhibition.” The Nation, January 19, 1871, 47–48; Our Art Schools,” New York Times, December 1, 1872; “The National Academy of Design,” Appleton’s Journal 8 (September 21, 1872), 325.

6. For the year 1874–75 the NAD’s antique class enrolled 246 students. See “Enrollment, 1826–2002,” National Academy of Design records, 1817–2012. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

7. “Typescript of James Edward Kelly’s memoirs with descriptions of New York City from the Civil War period to the 1930s,” Reel 1876; Frames 404–05. James Edward Kelly papers, 1880–1957. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

8. See “Typescript of James Edward Kelly’s memoirs,” Frames 404–05.

9. “Art Students’ League,” New York Evening Post, July 26, 1875; and G. W. Sheldon, American Painters: With One Hundred and Four Examples of Their Work Engraved (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881), 110.

10. Lloyd Warren, “The Atelier System,” The American Magazine of Art 7, no. 3 (1916): 112–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20559293.

11. Lois Marie Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 280.

12. Art Students’ League,” New York Evening Post July 26, 1875. Allen Tucker, “The Art Students League: An Experiment in Democracy,” Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition of the Art Students League of New York, January 22nd–February 2nd (New York: The Art Students League of New York, 1925), 15.

13. The equality mentioned in this article refers to that between men and women. See “Women Who Paint,” The Art Union 2, no. 4 (October 1885): 68.

14. The practice of list-keeping began with a members list in Frank Waller, First Report of the Art Students League of New York (New York: The Art Students League of New York, 1886), 53–55, and an instructors list in the Catalogue of the Works by Members, Students, and Instructors of the Art Students’ League of New York in the Retrospective Exhibition, 1875–1900 ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1900), [42] and 47. See also 1901–01 catalogue and 1904–05 catalogue, Archives of the Art Students League of New York. In earlier eras, the list was also called “the registry.” See “Notes on John Sloan’s Speech at Art Students League, 1950,” John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum.

15. “From Soup Cans to Flying Saucers” in the exhibition Collection 1940s–1970s, Fall 2019–Fall 2020. https://www.moma.org/calendar/galleries/5123.

17. Ann Temkin, “Re-Thinking Modern Art: A Preview of the MoMA’s New Collection Galleries with Ann Temkin,” Pollock Krasner House Lecture recorded in the John Drew Theater at Guild Hall on July 28, 2019, posted March 29, 2020, by Guild Hall, YouTube, 1 hr., 1 min., 7 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bXX m ZZDfgvU. Discussions about museum rehangs predated MoMA’s 2019 reopening and have continued after it. See Rachel Wetzler, “Autocorrect: The Politics of Museum Collection Re-Hangs,” ART news, September 19, 2016, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/autocorrectthe-politics-of-museum-collection-re-hangs-6971/; Holland Cotter, “ MoMA Reboots With ‘Modernism Plus’,” New York Times, October 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes. com/2019/10/10/arts/design/moma-rehang-review-art.html; Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Major Museums Are Mixing Old With New as They Reconsider Historical Collections,” March 5, 2024. Artnet, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museums-reconsider-historicalcollections-2445040; Alex Greenberger, “In Collection Hangs, Major Museums Remix the Classics,” Art in America May 2, 2024, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/ features/museum-collection-hangs-remix-classics-1234704248/.

18. My thanks to Caroline Ongpin and Jessica Angamarca for their research assistance on the Art Students League’s lists.

19 Catalogue of the Works by Members, Students, and Instructors of the Art Students’ League of New York in the Retrospective Exhibition, 1875–1900 ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1900); Fiftieth Anniversary of the Art Students’ League of New York ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1925). The Dudensing Galleries independently presented a group of selections from the League’s Fiftieth Jubilee exhibition. See “Art: Exhibitions of the Week,” New York Times, March 15, 1925. For its seventy-fifth anniversary, the League organized an inclusive exhibition of 388 works at the National Academy of Design, followed by a curated exhibition of 75 works at the Metropolitan Museum. See On the occasion of the Seventy-fifth Year of the Art Students League of New York, The Art Students League presents a Diamond Jubilee Exhibition of Fine Art by Members and Associates in the Gallery of the National Academy of Design (New York: The Art Students League, 1950); The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents the 75th anniversary exhibition of painting & sculpture by 75 artists associated with the Art Students League of New York ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1951); American Masters from Eakins to Pollock (New York: The Art Students League, 1964); American Masters: Art Students League (New York: The Art Students League, 1967); New York by Artists of the Art Students League of New York in Celebration of the Centennial Year of the Art Students League of New York: at the Museum of the City of New York, November 3rd to January 4th, 1975–76 ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1975); One hundred prints by 100 artists of the Art Students League of New York, 1875–1975 : [exhibition], April 22–May 17, 1975, at Associated American Artists, New York City ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1975); The Kennedy Galleries are host to the hundredth anniversary exhibition of paintings and sculptures by 100 artists associated with the Art Students League of New York, March 6–29, 1975. ([New York]: The Art Students League, 1975); The Masters: Art Students League Teachers and Their Students (New York: Art Students League, 2018). Two other exhibitions noted the League’s 60th and 50th anniversary in the American Fine Arts Society building. See The 60th-anniversary exhibition of members and associates of the Art Students’ League of New York : June 3rd to June 30th inclusive 1936 [foreword by Gifford Beal] (New York: Fine Arts Gallery, [1936] and On the occasion of the fiftieth year of the Art Students League of New York and of The American Fine Arts Society in their present quarters, the Art Students League presents an exhibition of distinguished artists, who, as students, or instructors, have been associated with it during sixty-eight years, in the Galleries of the American Fine Arts Society, Feb. 7–28, 1943. [New York: Art Students League, 1943].

20. Catalogue of the Works by Members, Students, and Instructors of the Art Students’ League of New York, 32.

21. For a checklist of this exhibition, see “Index of Exhibits, Golden Jubilee Exhibition, January 22–February 1, Inclusive 1925,” in Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition of the Art Students League of New York

22. Two excellent books with substantial discussions of the Art Students League and its artists are New York Modern: The Arts and the City (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999) and Ellen Wiley Todd, The ‘New Woman’ Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

23 . The subtitle of Marchal Landgren’s commissioned history of the Art Students League refers to one story. See Years of Art: The Story of the Art Students League of New

16. Télémaque received two scholarships. See “Hervé Télémaque student registration record,” Archives of the Art Students League of New York. The few references to Télémaque in the ASL’s records include: “The Exhibition Synastria,” Art Students League News 14, no. 4 (April–May 1961); “News of Telemaque,” Art Students League News 19, no. 1 (January 1966); “News of Life Members,” Art Students League News 25 no. 2 (February 1972); A photograph of Télémaque and Levi from 1961 by Carol Lazar appears in Art Students League Centennial Decade, 1966–1967, p. 8. For Julian E. Levi’s impressions of a young Hervé Télémaque, see “Oral history interview with Julian E. Levi, 1968 Oct.–Dec.” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. For audio of Télémaque’s commentary on No Title (The Ugly American), see https://www.moma. org/audio/playlist/297/3752. On Télémaque’s reaction to his painting No Title (The Ugly American) at the M oMA reopening, see Katie White, “Artist Hervé Télémaque, 81, Is One of the Previously Overlooked Stars of M oMA’s Rehang. Here’s What He Thinks About It,” artnet, October 19, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/hervetelemaque-museum-of-modern-art-1685749.

Helena de Kay Gilder

Artist, muse, patron, tastemaker, rebel, and cofounder of the Art Students League of New York. Helena de Kay Gilder (1846–1916) fit all these descriptions, though her place in American art would have been secure as a muse alone. Late in life she was painted by her friend Cecilia Beaux, and had previously been the subject, along with her husband and son, of a low-relief sculpture by another friend, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Most tantalizing for art historians was her youthful relationship with Winslow Homer, for whom she posed for multiple paintings, including a portrait; based on these works and written correspondence, it’s believed that Homer fell in love with her and unsuccessfully proposed marriage.

Helena de Kay was born in 1846. She attended classes at the Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design and studied privately with John La Farge, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Homer, some of the most progressive artists of the era. An able painter, de Kay’s real contributions came as what we’d now call an “influencer.” Frustrated by the

conservative nature of the National Academy, de Kay cofounded the Art Students League of New York in 1875 and the Society of American Artists two years later. The League was modeled after Parisian ateliers, in which each class was supervised by an autonomous instructor, with the further goal of treating men and women as equals. In 1878 de Kay served as the League’s Women’s Vice President, and continued as a board member in 1879. D e Kay married Richard Watson Gilder, a poet and the editor of both

“The Gilders played a uniquely progressive role in the late 19th century, participating in the meteoric rise of print media; helping to establish and promote a new American art world; supporting female artists, illustrators, and critics, and acting as the cultural tastemakers of their time.” —Page Knox

Scribner’s Monthly and The Century magazines, and the couple presided over informal salons at their Union Square home that included a who’s who of American artists and intellectuals. “The Gilders,” writes historian Page Knox, “played a uniquely progressive role in the late 19th century, participating in the meteoric rise of print media; helping to establish and promote a new American art world; supporting female artists, illustrators, and critics, and acting as the cultural tastemakers of their time.” 1

S upporting female artists wasn’t easy. Male artists viewed women as amateurs and barred them from joining art associations. Much to her frustration, this was true even of the Society of American Artists, which Gilder had cofounded. By 1900,

the society had 200 members, of whom nine were women. Yet even Gilder’s progressive vision had its limits. She campaigned against granting women political power and served on the executive board of New York State Opposed to Woman Suffrage.

Gi lder’s daughter Rosamond described her thus:

“ She accomplished an astonishing number of things with an apparent ease and calmness…. Besides five growing children her household usually included at least one visiting guest or relative. During these busy years, she belonged to several clubs, the Fortnightly, the Music Club, and others…she read widely in French, German, and English, and all the while comforted, encouraged, and kept alive that firebrand of energy and emotion, my father, who without her support, could never have survived the struggle on this ‘metropolitan battlefront’.” 2

JERRY WEISS

1 “The Original American Power Couple,” Intelligent Collector, intelligentcollector.

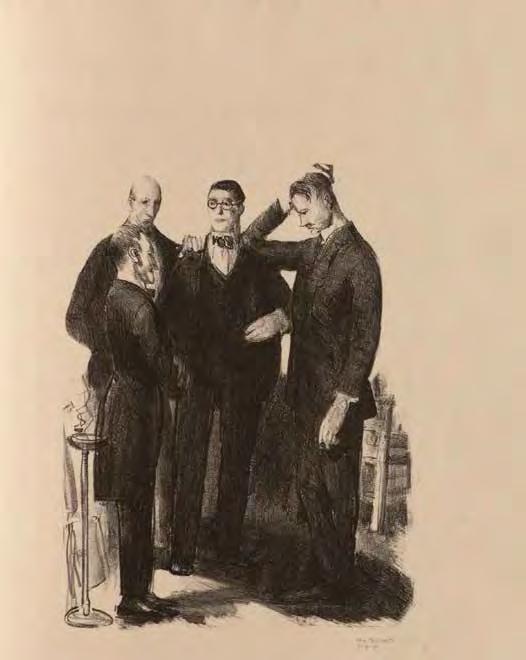

William Merritt Chase

“My god, I’d rather go to Europe than go to heaven!” 1 exclaimed twenty-two-yearold William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) to a group of St. Louis businessmen gathered to meet the promising young painter. They found more than enough potential in his abilities to propose a subsidy for his study abroad. In exchange, the members of the consortium would receive first choice from his paintings. Chase’s resolve in 1872 to attend Munich’s Royal Academy (fearing he would become too distracted by what he called the “frippery” of Gallic life) was a critical decision that would determine not only his own path but the pedagogy in art schools where he later taught.

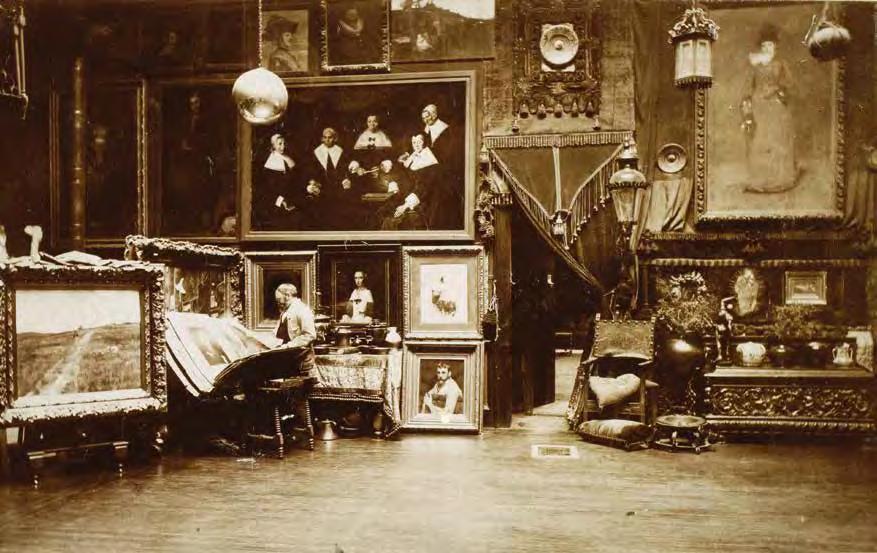

Upon his return to the United States in 1877, Chase found his Munich compatriot Walter Shirlaw on the teaching staff at the recently opened Art Students League. In 1875 a group of students at the venerable National Academy of Design had grown dissatisfied with the lack of academic freedom. They formed their own school, describing it as “…a voluntary association of art-students for the purpose of educating themselves.” 2 The group sought a more responsive and less hidebound teaching approach than the Academy’s endless required drawing from classical models. Fresh from his years training in the “revolutionary” Munich style, noted for direct drawing on canvas and expressive gesture, Chase was attracted to the egalitarian spirit of the new venture and soon joined the League. C hase and Shirlaw retained their prominent positions on the faculty in

two succeeding decades, the period in which Chase’s fame as an artist also grew. In 1879, he took over the premier space in the Tenth Street Studio Building, the reception studio that had belonged to leading Hudson River School artist Albert Bierstadt; Chase began to create an aesthetic environment like the ones he had seen in European ateliers. Filled with brocades, Persian carpets, and Venetian hanging lamps, these spacious rooms would function as exhibition spaces as well as salesrooms. Copies made in his Munich student days of Old Master paintings by Hals and Velázquez were hung high on the walls.

Despite the democratic founding of the League as a group of artists where “some are teachers and some are students,” the charismatic Chase became a legendary figure whose popularity was unrivaled in his years at the League. Ella Condie Lamb gave an account from her student days in the 1880s of her teacher’s

ABOVE: WILLIAM MERRITT CHASE, 1849–1916, SELF-PORTRAIT, 1913. OIL ON CANVAS, 24 1/4 × 20 1/8 IN. PARRISH ART MUSEUM, WATER MILL, NY, GIFT OF LOUIS BACON. 2014.2, PHOTO: © GARY MAMAY

“There was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exciting about [William Merritt Chase]....” 5 —Georgia O’Keeffe

“freedom and enthusiasm” and remarked on “his appearance with “spats and blackribboned eyeglasses.” She noted the thrill of his class demonstrations when he would seize a student’s largest brush and attack the canvas with “great globs of paint.” Most exciting were Saturday afternoons when students were invited to the Tenth Street studio.3 “Be vital in a big, art way.”4

C hase left the League in 1895 to found his own school, but he briefly returned in 1907. Among his students was a young artist named Georgia O’Keeffe. Although her mature style would diverge radically from his, she never forgot her

early teacher: “There was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exciting about him....” 5 It is these qualities that set the tone for the Art Students League in its foundational years and have imprinted the legacy upheld to this day.

ALICIA G. LONGWELL

1. Katharine Metcalf Roof, The Life and Art of William Merritt Chase (1917, repr. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1975), v.

2. Marchal E. Landgren, Years of Art: The Story of the Art Students League of New York (New York: Art Students League of New York, 1940), 44.

3. Ibid., 37.

4. As quoted in Alicia G. Longwell, William Merritt Chase: A Life in Art (Water Mill, NY: Parrish Art Museum, 2014), 12.

5. As quoted in Jerry Weiss, “I’ve Been a Person Other People Always Wanted to Paint or Photograph,” LINEA February 1, 2021, asllinea.org/georgia-okeeffe-portrait/

Dora Wheeler

A pioneering woman artist who established a successful career during the Aesthetic Movement, painter and designer Lucy Dora Wheeler Keith (1856–1940) was a prominent student of acclaimed Art Students League instructor William Merritt Chase. Wheeler studied with Chase privately and joined his class at the Art Students League from 1879 to 1880. She described him as a kind, unselfish, but rigorous teacher, nothing that “I started in one morning and he would not let me stop until the light was gone.” As her career progressed, she and Chase became colleagues and Wheeler served as a member of the board of Chase’s Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art on Long Island.

T he daughter of renowned designer Candance Wheeler, Dora was exposed to art from an early age and throughout her life worked alongside her mother. In 1877, Candace founded the Society of Decorative Art and over the next five years established the interior decorating firm Tiffany & Wheeler, with Louis Comfort Tiffany, as well as her own agency Associated Artists. A feminist, Candace campaigned for women’s engagement in the workforce and employed many young women artists in her companies. In 1885, while studying at the Académie Julian in Paris, Dora created a pastel drawing that became the preliminary design for her needlewoven tapestry Penelope Unraveling Her Work at Night (Metropolitan Museum of Art),

which was produced the following year by Associated Artists. The work was part of a series of tapestries designed by Dora featuring heroines of American art and literature. These compositions brought great acclaim to Associated Artists, although no other examples survive. Wheeler was also well known for her mural on the ceiling of the library of the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and for her portraits of leading writers including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman.

T hroughout her career she maintained a studio at Associated Artists on East 23rd Street that became a gathering place for artists and intellectuals including John Singer Sargent, Oscar Wilde, and Anders Zorn. The studio was the setting for Chase’s famous 1883 portrait Portrait of Dora Wheeler (Cleveland Museum of Art), although in the painting the background

is concealed by an elaborate gold tapestry. A subtle reference to Wheeler’s professional work, the tapestry also serves as a dramatic backdrop, lending the composition a modernist flatness. Seated in an ornately carved wooden chair, chin resting in her hand, Wheeler gazes at the viewer with thoughtfulness and determinization, conveying a sense of professionalism associated with the “New Woman.” One of Chase’s most

accomplished pupils, Wheeler’s career served as a model for the many women artists who studied at the League during the late nineteenth century.

JILLIAN RUSSO

1. DeWitt Lockman, “Interview with Dora Wheeler Keith,” January 24, 1927. Interviews of artists and architects associated with the National Academy of Design, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

2. Amelia Peck, Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design, 1875–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 147.

One of [William Merritt] Chase’s most accomplished pupils, Wheeler’s career served as a model for the many women artists who studied at the League during the late nineteenth century.

Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley

As great-granddaughter of the artist Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley (1860–1958), and an art historian and museum curator, I have always been fascinated by the wonderful life of my American greatgrandmother. Wilhelmina was a twentyyear-old art student when she joined the Art Students League in 1880. Over twelve years, from 1880 through 1892, she served as the ASL’s librarian, costume designer,1 corresponding secretary, 2 female vice president,3 and member of the League’s Board of Control. 4 Short notes in her diary, which she kept since she was twelve, have allowed me to reconstruct her time at the Art Students League.5

I nitially, Wilhelmina spent her first academic season of 1879–80 at the Cooper Union under Julian Alden Weir.6 After joining the ASL in 1880, she attended Antique classes under James Carroll Beckwith when the League was

still housed at its first location, on the top floor of a building on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and West 16th Street.7 In 1881, Wilhelmina attended Portrait classes under William Merritt Chase, and in 1882, life classes under Charles Yardley Turner. From 1882 through 1887, the ASL had its second location at 38 West 14th Street. 8 In 1883, most likely via Beckwith, Wilhelmina met the Irish poet, writer, and “professor of aesthetics” Oscar Wilde in New York City during his famous American lecture tour. According to her diary, Wilhelmina enjoyed “several long talks with Wilde about books, art, etc.” and also met him at a reception in Beckwith’s studio.9

We can also read in her diary that Wilhelmina posed as a model at the ASL . Artist Kenyon Cox, an early instructor at the ASL , painted her life-size portrait in 1887.10 In 1888, one year after the ASL

Over twelve years, from 1880 through 1892, [Hawley] served as the ASL’s librarian, costume designer, corresponding secretary, first female vice president, and member of the League’s Board of Control.

moved to its third location at 143–147 East 23rd Street, Wilhelmina attended Kenyon Cox’s Antique classes and Sketch classes. From 1889 to 1891, Wilhelmina maintained her Manhattan studio at West 14th Street, where, according to her diary, she made many children’s portraits in watercolor. Her member ticket of the ASL for the 1891–92 season confirms her final year of service on the League’s board.11 In the summer of 1892, Wilhelmina decided to move to Paris, “[for] two years, or perhaps forever,” as she wrote in her diary.12 Since that first summer in Paris, Wilhelmina also traveled to Rijsoord, a Dutch artist colony, where she met my great-grandfather Bastiaan de Koning, whom she married in 1901. In 1904, when Wilhelmina was 44 years old, she gave birth to her only child, my grandmother Georgina Florence de Koning, who was named after

Wilhelmina’s two aunts, Georgina and Florence Merritt, who had supported and sponsored her artistic career from the beginning. After the birth of her daughter, Wilhelmina continued to teach art classes during the summer months in Rijsoord, traveling to Paris to meet her friends and visit art exhibitions.

ALEXANDRA VAN DONGEN

1. Wilhelmina designed costumes for the ASL , which were used during the costume classes, as was recorded in a reminiscence of the student years of Ella Condie Lamb, recalling that ‘Wilhelmina Hawley made the first costume owned by the League—it was of green velvet “Ella Condie Lamb, 1881 to 1884,” in Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition of the Art Students League of New York, exh. cat., January 22 to February 2, 1925 (New York: Art Students League of New York, 1925), 39. Email correspondence with Stephanie Cassidy, February 10, 2003.

2. From 1886 to 1887 Wilhelmina worked as the corresponding secretary of the League. Family Archive Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, Alexandra van Dongen.

3. In 1886 Wilhelmina was elected Women’s Vice President of the ASL , serving two consecutive terms (1886–88). Newspaper item on the Art Students League in the New York Times of April 21, 1886: “At the annual meeting of the Art Students League of New York, held last evening, at their pleasant rooms at No. 38 West Fourteenth-street, officers were elected for the ensuring year as follows: President Mr. C. R. Lamb, VicePresidents Miss. W. D. Hawley and Mr. H. B. Snell.”

4. Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition of the Art Students League of New York, 69.

5. Alexandra van Dongen, “‘For Two Years, or Perhaps Forever’; Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley and the artists’ colony in Rijsoord,” 400 Years Dutch-American Stories, National Archives, The Hague, Netherlands, 2004, nationaalarchief.nl/ en/research/400-years-dutch-american-stories/for-two-years-or-perhaps-foreverwilhelmina-douglas.

6. Weir was one of the early instructors of the Art Students League in New York.

7. Ira Goldburg, “Founded by and for artists, the Art Students League thrives after 129 years,” in The Art Students League of New York, 2004–05 (New York: The Art Students of New York, 2004), 2.

8. According to the wq archives, Wilhelmina’s home address at the time was 135 West 55th Street. Close to her studio was a block of artists’ studios, such as the Holbein, a studio building at 146–152 West 55th Street.

9. Oscar Wilde, Impressions of America (London: A. S. Mallett, 1883).

10. According to Wilhelmina’s diary, Cox’s portrait of her was exhibited in 1888 as part of an academic exhibition in Ohio, where it was awarded a gold medal.

11. Correspondence, April 26, 1896, Family Archive: Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, collection Alexandra van Dongen.

12. Diary, Family Archive: Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, collection Alexandra van Dongen.

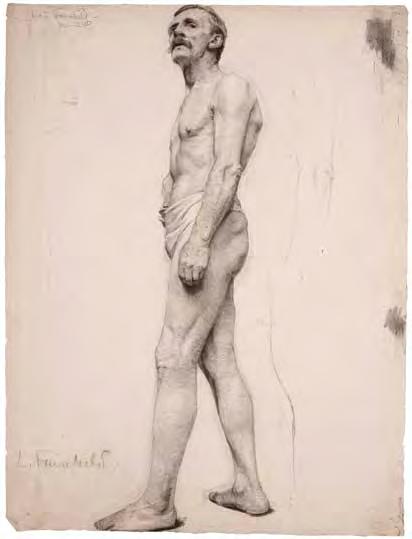

Kenyon Cox

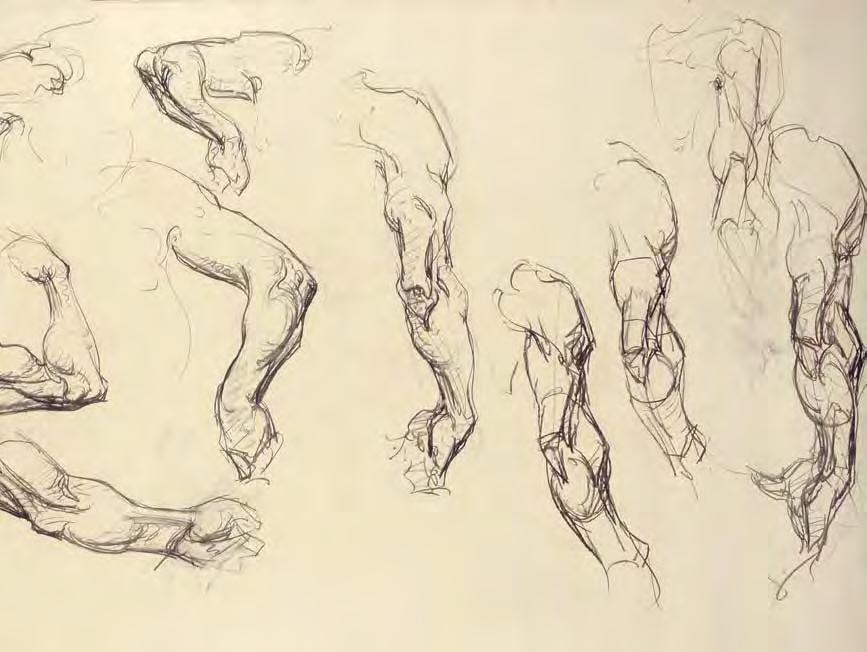

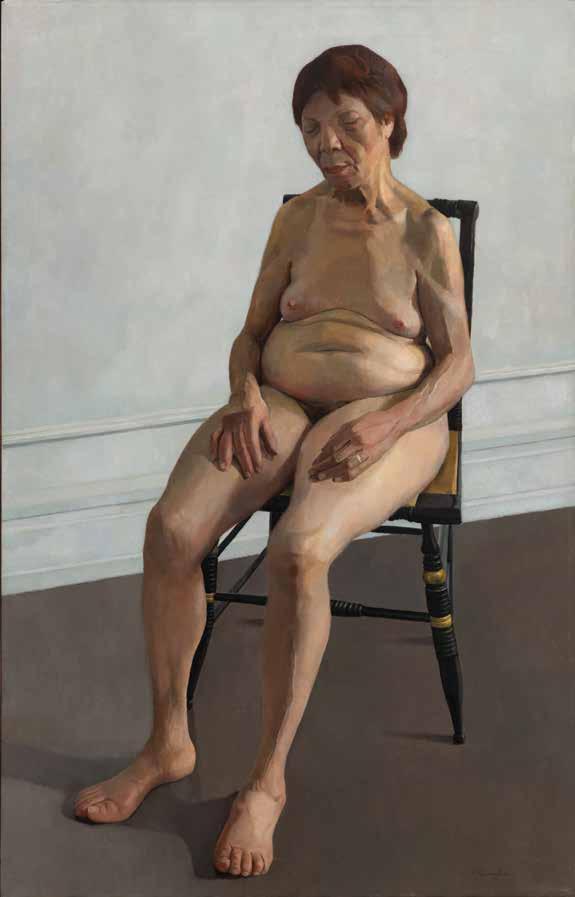

Living in New York City in 1883 at the start of his career, having just returned to the United States from studying in Paris, Kenyon Cox (1856–1919) looked for ways to boost his income. He could not make a living exclusively by selling paintings, so he was receptive when the Art Students League invited him to teach in 1884.1 Although he began teaching fortuitously, his role as an instructor quickly became a source of pride and satisfaction, and he taught life drawing and painting, drawing from the antique, and later lectured on artistic anatomy continually until the spring of 1909.2

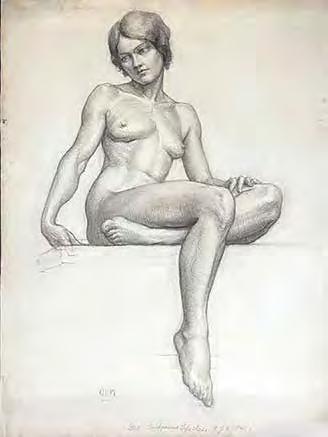

Cox’s rigorous method for mastering the depiction of the human form’s mass and posture was based on a centuriesold tradition promulgated by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which he had inherited from Jean-Léon Gérôme while a student in his atelier. He emphasized the representation of the figure’s form using a combination of contour lines and strong modeling, paying only secondary attention to surface texture and idiosyncratic lighting effects. Some

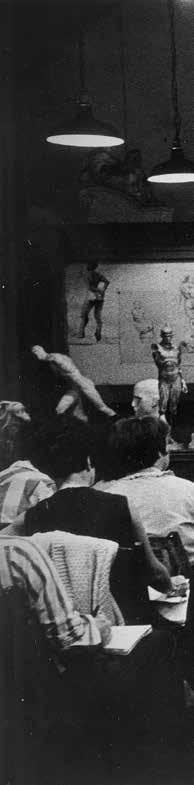

students were in awe of his exacting standards and his French pedigree.3 Responses to Cox’s classroom demeanor were mixed. As his wife and former student, Louise Howland King Cox, recalled, “He was so conscientious in judging a canvas that sometimes he hurt when he meant to encourage and was amazed when a student burst into tears.”4 Lucia Fairchild Fuller valued his anatomy lectures, as reported in a review of her work: “she describes Kenyon Cox’s anatomy lectures at that time as having been a great help and delight to her, so they probably played their part in enabling her to produce the well-drawn nudes which she has sometimes exhibited.” 5 One of her male figure studies in the League’s collection, executed for H. Siddons Mowbray’s women’s life class circa 1891, captures details of the studio,

“My life-class work is undoubtedly the best in the whole school…”

—Kenyon Cox

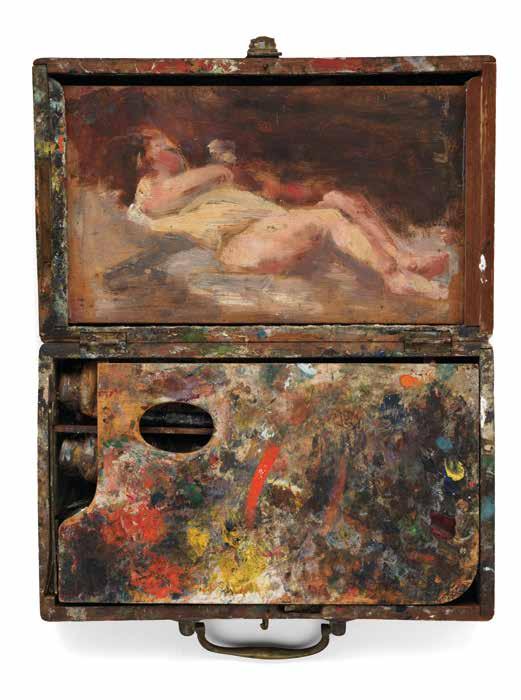

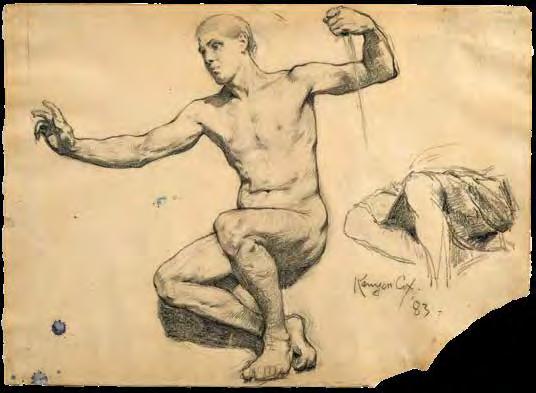

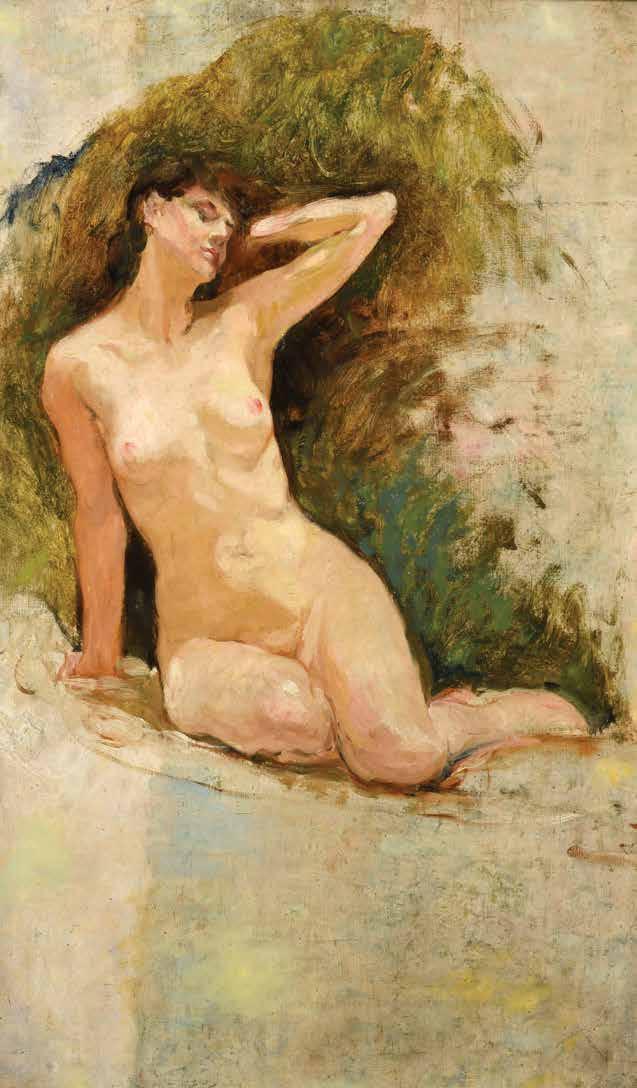

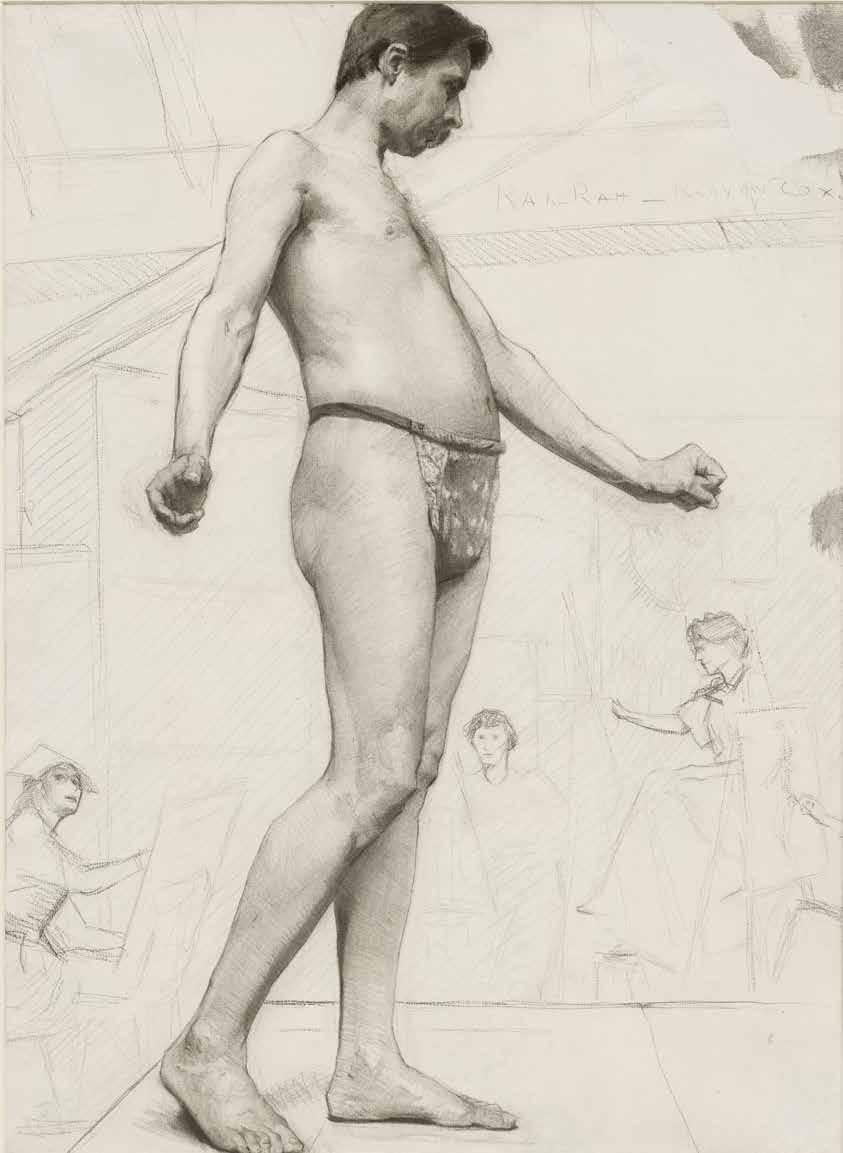

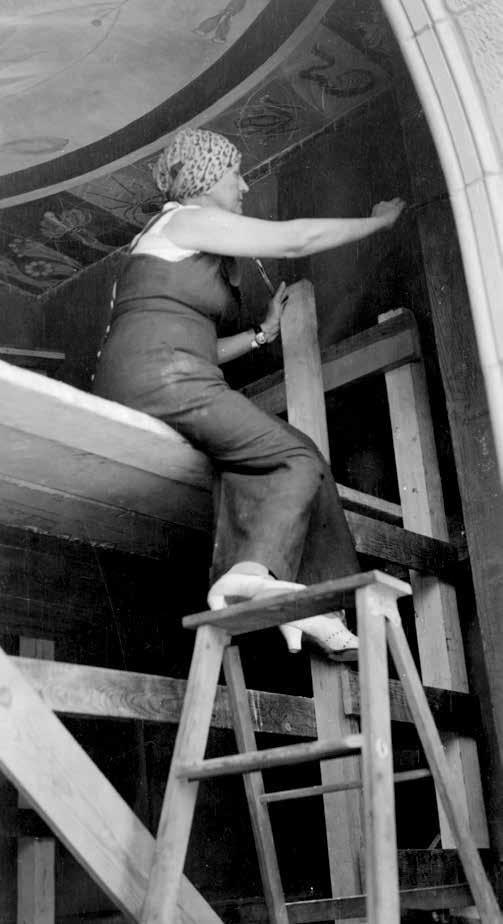

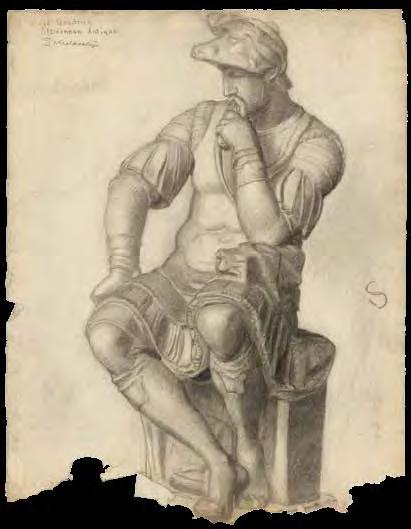

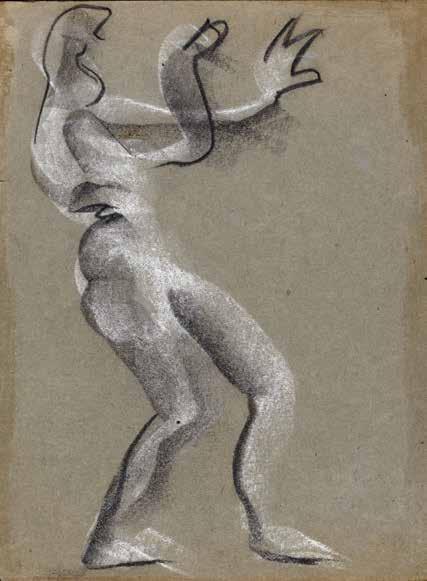

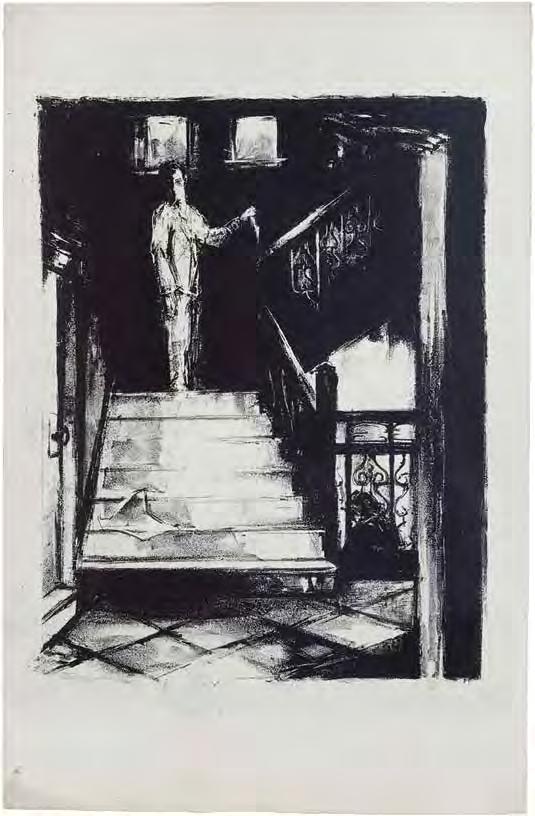

OPPOSITE: KENYON COX, UNTITLED, 1883. CHARCOAL ON PAPER, 16 × 22 IN. PERMANENT COLLECTION, THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK, 100614 ABOVE: KENYON COX, STUDY FOR EVENING , 1883. OIL ON BOARD, 30 × 18 IN. PERMANENT COLLECTION, THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE OF NEW YORK, 100214

which include “RAH RAH KENYON COX!” scrawled on an overhead beam.6 Yet, antipathy toward Cox probably prompted a vandal in 1910 to slash holes in his painting The Girl with the Red Hair (c. 1890), and jam it “behind a radiator in the room of the woman’s life class.” 7 Cox had donated the painting to the League around 1908 to provide inspiration.8 Cox may have donated another seated female nude to the League for similar reasons, here identified as a Study for “Evening,” painted in 1883.9 Cox’s pride in his students and competitiveness with his fellow antique and life instructors is evident from a letter he wrote to his wife on May 15, 1906, after scholarships and honorable mentions were announced for work from the academic year. His students collected three scholarships and three mentions, which surpassed those won individually by George B. Bridgman’s and Frank Vincent DuMond’s students. He noted with restrained glee that for women’s life, “DuMond got nothing.” He further laid into DuMond: “My life-class work is undoubtedly the best in the whole school… and the DuMond classes are awful. His policy of admitting pupils who haven’t any previous training is bearing fruit, and his class gets weaker and weaker, while all the serious workers come to me.” 10

JEFFREY M. FONTANA

1. Cox also took work teaching life classes at the Gotham Club of Art Students in 1884; H. Wayne Morgan, Kenyon Cox, 1856–1919: A Life in American Art (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1994), 84, note 27.

2. In May of 1885 he sanguinely wrote his mother, Helen Finney Cox, “My teaching has been very successful this winter and my pupils say they have learned more than they ever did before in their lives, and were unanimous in asking the League to engage me for next winter;” Morgan, Kenyon Cox, 1856–1919 , 84, note 26.

3. Christian Buchheit and Lawrence Campbell, Reminiscences (New York: Art Students’ League of New York, 1956), 19.

4. Louise Howland King Cox and Richard Murray, “Louise Cox at the Art Students League: A Memoir,” Archives of American Art 27, no. 1 (1987): 20.

5. “Honors of Women Painters,” New York Sun , April 17, 1910, 8.

6. Lucia Fairchild, Untitled, vine & compressed charcoal, 24 1/2 × 18 1/2 in., number 101468; James Lancel McElhinney, Classical Life Drawing Studio: Lessons & Teachings in the Art of Figure Drawing (New York: Sterling, 2010), 160.

7. “Cut Up Girl Painting,” Burlington Free Press, January 8, 1910, 10, newspapers.com/ article/the-burlington-free-press/35634988/; “Cox Picture Slashed,” American Art News 8 no. 14 (January 15, 1910): 1.

8. A former student recalled The Girl with the Red Hair enthusiastically: “In our life classroom at the old Art Students League, there was a study by Kenyon Cox of a nude girl with red hair, a magnificent example, in oils, of vital life in the raw, an unforgettable canvas. It had a hole in it when I last saw it, and I do not know what became of it;” Jerome Myers, Artist in Manhattan (New York: American Artists Group, Inc., 1940), 98.

9. Kenyon Cox, presently catalogued as Untitled , 1900, oil on board, 30 × 18 in., number 100214. See Ronald G. Pisano and Beverly Rood, The Art Students League: Selections from the Permanent Collection (Hamilton, New York: Gallery Association, 1987), 18–19. Compare the painting to the black ink and graphite Sketch for “Evening” at the Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, number 1919.10, hvrd.art/o/305961, and the oil on canvas Study for “Evening” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, number 1983.114.6, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/study-evening-5854.

10. H. Wayne Morgan, ed., An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883–1919 (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1995), 145.

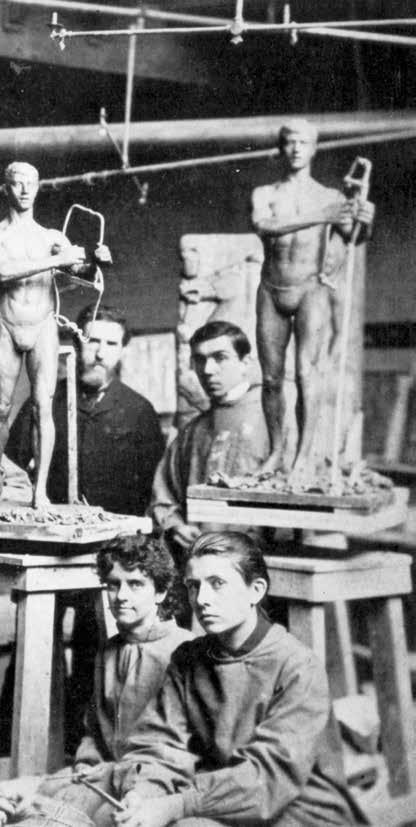

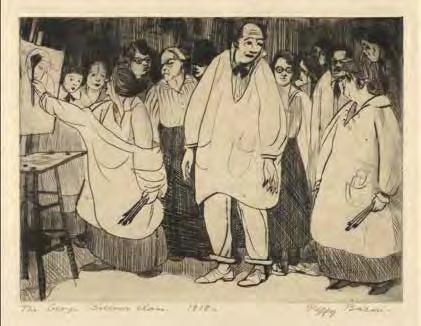

Kate Cory

After honing her skills at the Art Students League, the intrepid and enterprising artist Kate Cory (1861–1958) forged an unconventional career that flouted the era’s gender norms. Scholars have studied Cory’s work documenting the cultural traditions of the Hopi with her paintbrush and lens, but her endeavors in the industrial arts have received scant attention.

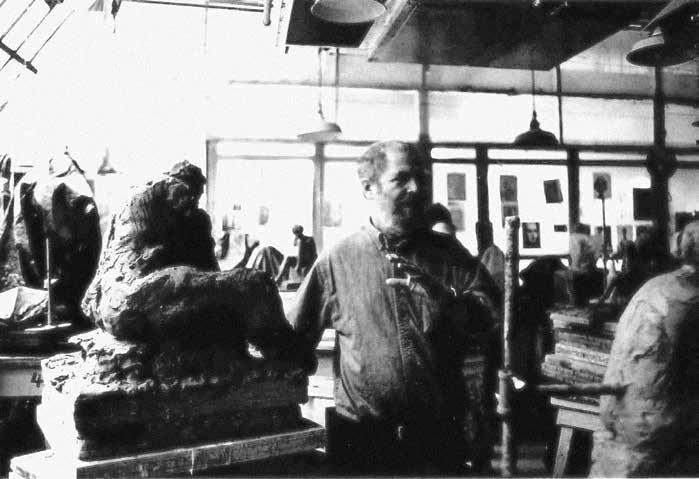

Born into privilege in Waukegan, Illinois, Kate arrived in New York City with her family in 1880. She began her training at the Woman’s Art School of the Cooper Union (1884–87), winning prizes in every class she enrolled in.1 She also undertook an intensive course of study at the Art Students League (1886–90), including Costume (drawing and painting from the model in costume), Drawing from the Antique with Kenyon Cox, and Modelling in Clay with Augustus Saint-Gaudens.2

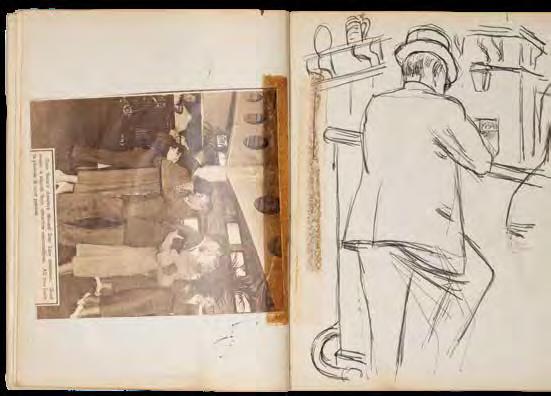

A photo of the celebrated sculptor’s class captures students, including a determined Cory, posed with their clay models of seminude archers. Kate had clearly proven her artistic bona fides by this time: the Cooper Union hired her to teach Cast Drawing from 1888 to 1890.3

Cory took advantage of expanding opportunities in the industrial arts, applying her talents to wallpaper design

and pottery, among other pursuits. In 1887, a journalist admired Cory’s wallpapers at a Manhattan showroom, displayed alongside examples by eminent designers: “It is needless to say, words of praise respecting Warren, Lange & Co.’s designs, other than to repeat the names of such artists as Lockwood De Forest, Miss Kate Cory, Dora Wheeler, Mrs. C. Wheeler, Rosina Emmett, Louis C. Tiffany, Samuel Colman, and others, whose talents are shown in the artistic purity and excellence of the patterns and colorings.”4 Cory joined forces with art potter Charles Volkmar in 1895 to produce a series of wares with historical subjects transfer-printed and painted in blue and white. As Volkmar’s son later recounted, Cory’s financing enabled them to rent a vacant pottery in Corona, Queens, to produce the Delftware-inspired pottery.5

Their wares, retailed exclusively at Joseph McHugh’s The Popular Shop, garnered a gold medal at the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition that year. Cory gave a tour of the pottery to a writer for the Clay Record, who praised her as “a woman pioneer in the business.” 6

I n 1905, the artist Louis Akin urged Cory to venture to the Hopi Reservation in Arizona, where he hoped to establish

an artist colony. Though the colony never materialized, Cory remained there for seven years, living a hardscrabble life among the Hopi and documenting their daily lives and sacred ceremonies.7 Though she remained based in Arizona for the rest of her life, Cory maintained ties to the East Coast art world and exhibited a work in the landmark Armory Show in 1913. 8 During World War I, she returned to New York City briefly to deploy her art in service of the war effort, designing aircraft wings and painting bombers with camouflage patterns.9 She also recharged at the ASL , attending classes and lectures by luminaries including George Bellows, John Sloan, and Robert Henri.

MARGI HOFER

1. Cooper Union annual reports, 1884–87, Cooper Union Archives. Cory studied Normal Drawing in 1884, Elementary Drawing in 1886, and Drawing from Life in 1887.

2. According to ASL student records, Cory was elected a member in 1890 and became a life member in 1901. She took additional classes in 1901–02 and 1917–18.

3. Cooper Union annual reports, 1888–90, Cooper Union Archives.

4. Richard Spenlow, “Decorating and Furnishing,” New York Times, August 28, 1887. It is noteworthy that Kate’s brother, J. Stewart Cory, was in the wallpaper business and established a major factory in Newark, New Jersey. See [Merit H. Cash Vail], Essex County N.J. Illustrated (Newark: L. J. Hardham, 1897), 192.

5. Leon Volkmar typescript, August 6, 1939. New-York Historical Society, museum object file 1939.280–287. The wares are marked “Volkmar & Cory.” For more information on the partnership, see forthcoming essay: Margi Hofer, “History in Blue and White: The Commemorative Wares of Charles Volkmar and Kate Cory,” Ceramics in America 2025 , edited by Ronald Fuchs (Milwaukee, WI : The Chipstone Foundation, 2025).

6. “American Delft Ware: The Secret of Its Blue at Last Mastered by American Potteries,” The Clay Record 8, no. 1 (January 14, 1896): 22. The partnership ended later that year.

7. For more information about Cory’s time among the Hopi and her later career, see Tricia Loscher, “Kate Thomson Cory: Artist in Hopiland,” The Journal of Arizona History 43, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 1–40 and Melody Graulich, “I Became the ‘Colony’”: Kate Cory’s Hopi Photographs,” in Susan Bernardin et al, Trading Gazes: Euro-American Women Photographers and Native North Americans, 1880–1940 (New Brunswick, NJ : Rutgers University Press, 2003), 73–108. Papers, photographs, and artwork are in the collections of Sharlot Hall Museum and the Smoki Museum in Prescott, AZ , the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, and the Waukegan Historical Society in Waukegan, Illinois, among other repositories.

8. Cory exhibited—and sold—her painting Arizona Desert . See Milton W. Brown, The Story of the Armory Show, 2nd ed. (1963; repr., New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 213.

9. Loscher, “Artist in Hopiland,” 24 and Sandy L. Moss, “Kate Cory: Hopi Historian, Artist and Photographer,” Territorial Times 3, no. 1 (November 2009): 6.

Cory remained [on the Hopi Reservation] for seven years, living a hardscrabble life among the Hopi and documenting their daily lives and sacred ceremonies.

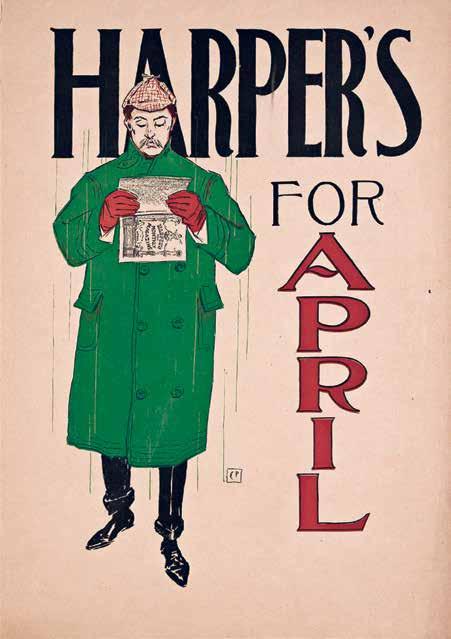

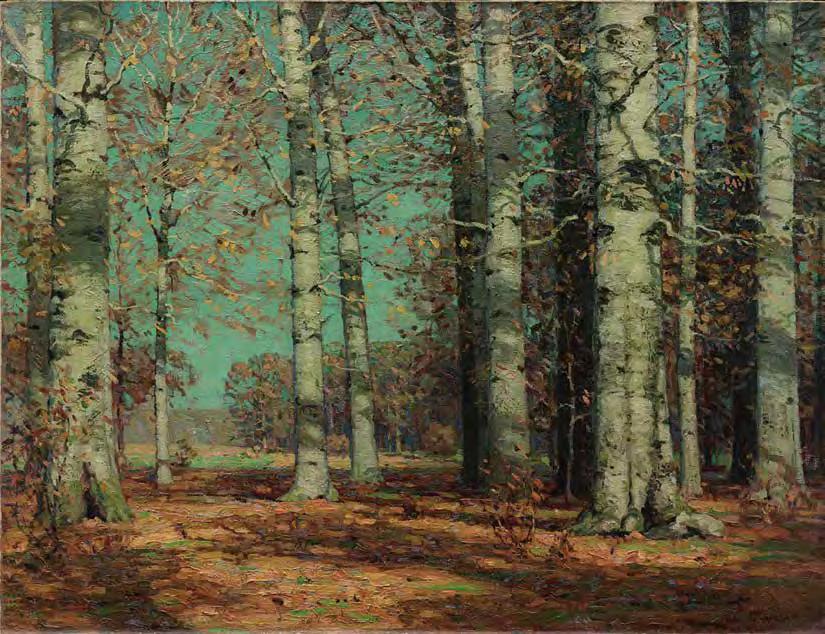

Frank Vincent DuMond

In 1892 the young artist Frank Vincent DuMond (1865–1951) returned to New York after four years of study in Paris at the Académie Julian in the ateliers of Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, and Gustave Boulanger. His early masterpiece Christ and the Fisherman had received a prize at the Salon of 1890, and he returned home ready to embark on a career as a professional artist. His time in Paris was steeped in rigorous classical training, but he also would have been immersed in the contemporary art scene of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting. Also, he had the good fortune to join James McNeill Whistler’s circle of expatriate artists and students. These seemingly disparate experiences would eventually converge to inform DuMond’s unique sensibility as an artist and educator.

T he year 1892 also marked the opening of the American Fine Arts Society building on West 57th Street, with the still nascent Art Students League as one of its inaugural tenants. The League had begun modestly seventeen years earlier, becoming a more progressive alternative to the established, conservative National Academy of Design. DuMond had studied at the League with William Sartain before departing for Paris. Upon his return, DuMond began teaching classes at the League in the studios of the grand beauxarts structure, and there would begin a most serendipitous confluence of the right person in the right place at the right time. In the new century, the United States would go on to fulfill its ambition to be a global leader, and New York City would become the center of commerce and arts in what came to be known as the American

“Every day I learn more, with the help of my students. They have taught me that passing on one’s own accumulated knowledge and experience to others is the most noble profession in the world.”

—Frank Vincent DuMond

Century. The Art Students League, with its pluralistic ideals and fortuitous geographical placement at the center of burgeoning Manhattan, would become one of the premier art schools in the world. And DuMond, along with his old Parisian flatmate George B. Bridgman, would play a vital role in mentoring the artists who would define a distinctly American artistic voice in the figurative tradition.

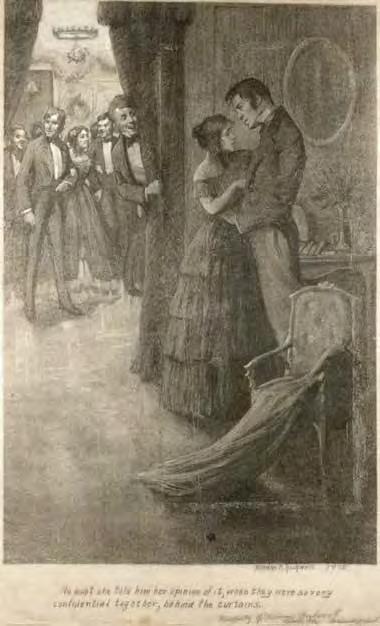

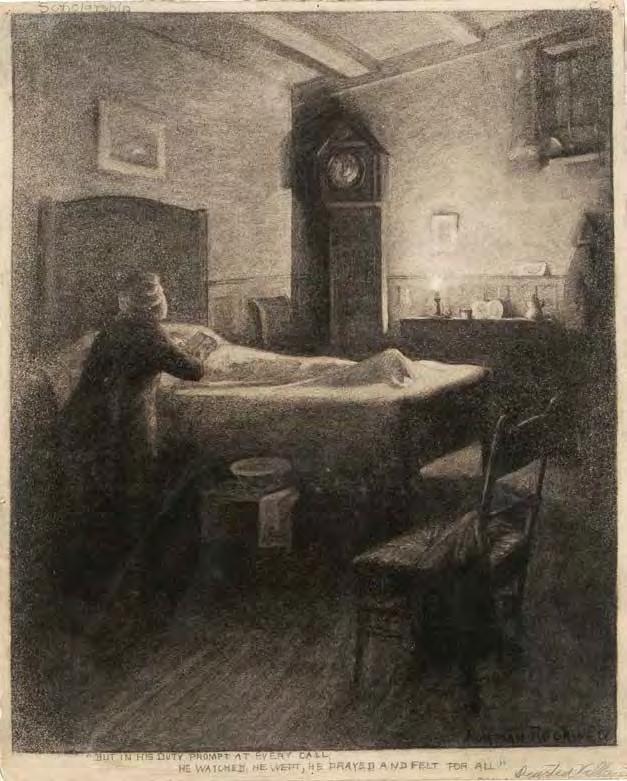

D uMond maintained a busy schedule as a portraitist, illustrator, and noted muralist while teaching at the League. His first classes were in cast drawing

where Charles Hawthorne was an early student. He also taught life drawing and was the first instructor at the League to allow his students to draw from life without first spending time in the cast room, much to the chagrin of the classicist Kenyon Cox. His influence as an instructor would be best remembered as an incredible sixty-year tenure teaching painting from life in what he would describe as “the silvery light” of Studio 7. DuMond taught thousands of students the principles of painting from life. Many luminaries of American art studied here

with DuMond: Eugene Speicher, Norman Rockwell, James Montgomery Flagg, Ogden Pleissner, John Marin, and the portraitist Everett Raymond Kinstler, just to name a few. But equally significant are the many distinguished artists who continued his legacy as instructors, especially in the realm of landscape painting. John F. Carlson, the author of a seminal book on landscape painting, was taught by DuMond. So was Frank J. Reilly, an influential teacher who developed a system of instruction for illustrators that became known as the Reilly Method. Arthur Maynard, a distinguished painter and founder of the Ridgewood Art Institute, studied with DuMond. My teacher, Frank Mason, a legendary painter and instructor, continued teaching the principles he learned from DuMond at the League.

By all accounts, DuMond was an extraordinary instructor. I have met many former students over the years beyond my own instructor, Frank Mason, and they all spoke reverently about his influence. His teaching style was based as much on philosophy as on technique, perhaps more so. He believed in principles over methods and the importance of learning to see. He didn’t write his teachings down, and he discouraged his students from taking notes. He believed in learning by osmosis over time. It is one of the reasons that he is not as well-known as other luminaries of art education. Instead, he spoke about

painting and art in spiritual and poetic terms so that the students could immerse themselves in the metaphysical nature of light. With that understanding, painting could follow.

A lasting legacy of DuMond’s instruction is his development of the famed Prismatic Palette. It represents a physical manifestation, in strings of color values, of the rainbow he described as always glowing over the landscape. As an avid plein-air painter, he was a founder of the artists’ summer community in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where American Impressionism flourished. The palette is the culmination of his explorations in painting outdoors in all kinds of light and atmospheric conditions. He especially pushed boundaries when it came to expressing the variety and intensity of sunlit greens. He taught his students this palette in his landscape classes in Old Lyme and Vermont. Often misunderstood as a method or formula, the palette is more of a conceptual tool to help students see the light spectrum of nature in terms

of color-value progressions. This approach has continued to be taught after DuMond’s passing in 1951. Its influence on generations of artists cannot be overstated. The concepts of the landscape were brought into the studio as well, where students were compelled to see the model bathed in the light and atmosphere of the space. Again, as per his temperament, none of this was written down or codified in a book, and consequently, DuMond has not received his due credit for his role in preserving the practice of landscape painting throughout the twentieth century and beyond. Too wise to believe his way was the only way, DuMond imparted an open-endedness in the teaching of the palette, which continues to this day and has evolved into a variety of approaches. That is how DuMond would have wanted it. His philosophy of painting and teaching and possibly of life, could be summed up in the quote: “Every day I learn more, with the help of my students. They have taught me that passing on one’s own accumulated knowledge and experience to others is the most noble profession in the world.”

JOHN A. VARRIANO

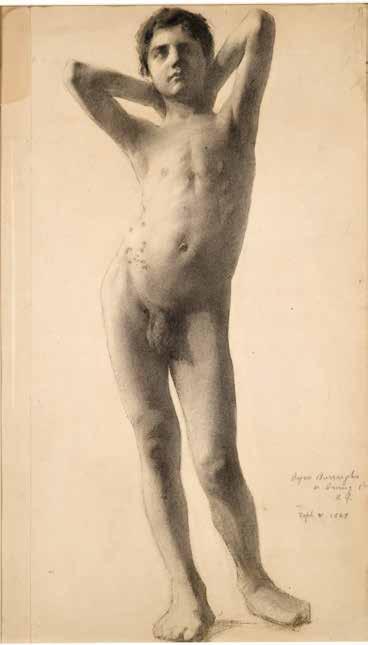

Bryson Burroughs & Edith Woodman

For over twenty-five years, Bryson Burroughs (1869–1934) spent his mornings painting in his studio on East 85th Street in Manhattan, and in the afternoons walked to his part-time job nearby. From 1909 to 1934, Burroughs was Curator of Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

B urroughs arrived in New York City by way of Hyde Park, Massachusetts, and Cincinnati. He first registered at the Art Students League of New York in 1889, and studied with Kenyon Cox and Harry Siddons Mowbray until 1891. His student work was good enough to win a prize that paid for a five-year stay in Europe, two years of which were devoted to studying in Paris. In Paris, Burroughs met Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose pale palette and classical themes exerted a lasting influence. The observational realism of his early studies evolved to a more eclectic production of biblical and mythological narratives. Art historian Lloyd Goodrich—himself a former League student—wrote that “Burroughs’s classicism was free from the kitsch of French salon art and the solemnity of American mural painting with its

idealized Greco-American females symbolizing civic virtues.”

After he returned to New York, Burroughs served briefly as both League president and an instructor, teaching from 1899 to 1902. During the first years of the twentieth century, his paintings won prizes at several international expositions, but earning money through sales proved difficult. Financial assistance came in 1906, when he was hired as Assistant Curator of Paintings fat the Met and assumed the role of Curator

“As a painter [Burroughs] developed a personal style based on traditional figure drawing and a predilection for historical, biblical, and mythological subjects. As a curator his criteria for the acquisition of paintings reflected a breadth of vision unequaled at the time.” —Douglas Dreishpoon

in 1909. Other League instructors had served as trustees and had helped shape the museum’s policies, but none for so long or at such a decisive level. According to art scholar Douglas Dreishpoon:

“As a painter he developed a personal style based on traditional figure drawing and a predilection for historical, biblical, and mythological subjects. As a curator his criteria for the acquisition of paintings reflected a breadth of vision unequaled at the time.” 1

During his tenure at the museum, Burroughs oversaw the acquisition of old master works such as Crucifixion and Last Judgment by Jan Van Eyck, Pieter Brueghel’s The Harvesters, Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates, and Michelangelo’s drawing of the Libyan Sibyl. His championing of modern artists initially met with resistance from the museum’s trustees— Burroughs was nearly fired for approving the purchase of Renoir’s Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children, and he later engineered the purchase of the first painting by Cézanne to enter a public collection in the United States. Eager to add late watercolors by Winslow Homer to the Met’s collection, he corresponded directly with the artist and organized a memorial exhibition of Thomas Eakins’s paintings while acquiring some for the museum. Burroughs also enlarged the Metropolitan’s collection of contemporary realism, adding works by League instructors Reginald Marsh, Arnold Blanch, Allen Tucker, and Hayley Lever (Marsh married Burroughs’s daughter Betty in 1923, and lived in their family home in Flushing).

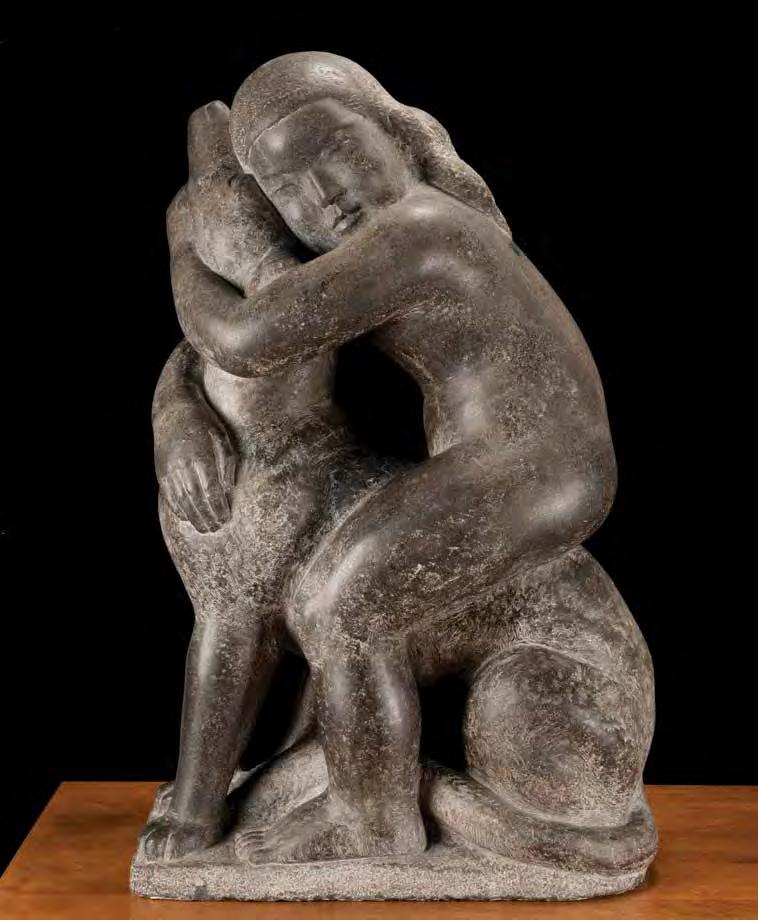

Burroughs married a fellow League student, the sculptor Edith Woodman (1871–1916), while

traveling together through Europe in 1893. Woodman began her studies at the League at the age of fifteen, and was registered there from 1886 to 1892, studying with Kenyon Cox and Augustus Saint-Gaudens—her daughter recalled other teachers, including Frederick MacMonnies and Alexander Stirling Calder.2 Later, in Paris, Woodman studied with Jean-Antoine Injalbert and Luc-Olivier Merson. The medieval cathedrals at Chartres and Amiens inspired her to adopt a Neo-Baroque style.

W hile still a student in New York, Woodman was doing decorative work for Tiffany and taking commissions. After seeing the work of Aristide Maillol on a second trip to Paris in 1909, she refined the forms in her figure work while retaining a more naturalistic approach in her portraits. She was, according to her daughter, a more successful artist than her husband. Woodman continued exhibiting and winning prizes throughout her life, including recognition for the best artwork by an American woman at the National Academy of Design in 1907, and a silver medal at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915, where she was also commissioned to create two outdoor works.

T he Burroughs’ daughter, Betty Burroughs Woodhouse, was a sculptor, teacher, and editor. Their son, Alan Burroughs, was an art historian, lecturer, museum curator, and author.

JERRY WEISS

2. Oral history interview with Betty Burroughs Woodhouse, May 24, 1977. aaa.si.edu/ collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-betty-burroughs-woodhouse-13140.

1. Douglas Dreishpoon, The Paintings of Bryson Burroughs (1869–1934) (New York: Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., 1984).

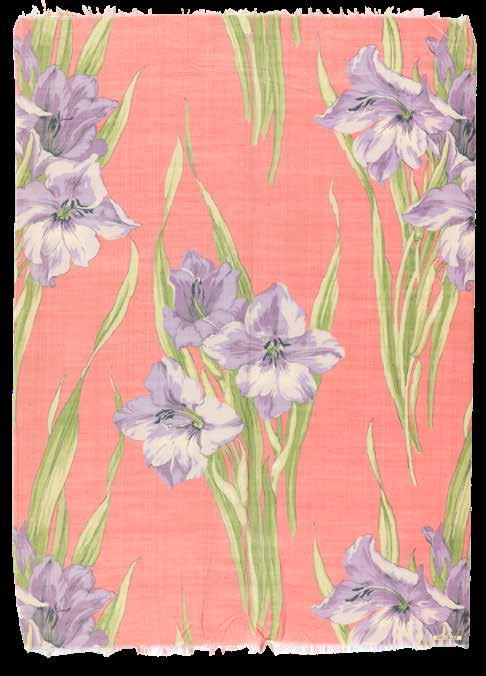

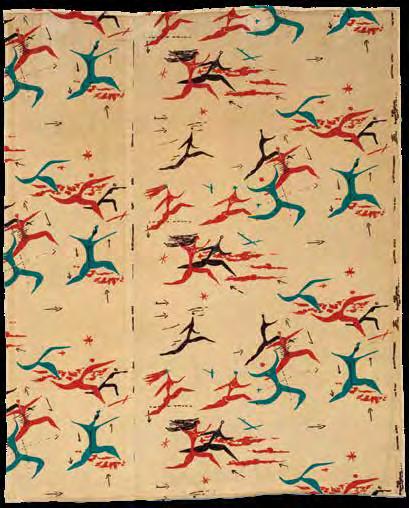

Sophia Louise Crownfield

Sophia Louise Crownfield (1862–1929) was born in Baltimore, Maryland. There she worked as a china painter before moving to New York in 1889. 1 While Crownfield’s educational experiences in Baltimore are unknown, in January 1889, she enrolled at the Art Students League. She skipped the preparatory course work, attending antique classes with instructor George de Forest Brush. Brush, who had trained in Paris under Jean-Léon Gérôme, had his students draw from plaster casts of classical sculpture to further refine their drawing skills.

Crownfield continued her studies at the Art Students League while actively pursuing a freelance career in design. An important milestone was achieved in 1893 when her floral design for a wallpaper was displayed at the Women’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition. 2 Crownfield, along with her sister Eleanor and friend Emma W. Doughty, later listed themselves as “Designers & Draughtsmen” in Trow’s Business Directory of New York City of 1898.3 By the early 1900s, American silk producers had made significant

advancements in their manufacturing capabilities but still looked to France for design inspiration. Paying handsome sums for French textile samples, manufacturers had their designers copy patterns directly or use them as inspiration for their silk fabrics.

Crownfield worked within this system, creating floral patterns and other designs that signaled her awareness of trends like Japonisme and the Arts and Crafts movement. While Crownfield seemed to favor more lifelike floral patterns, her 1906 Japanese-inspired

An important milestone was achieved in 1893 when her floral design for a wallpaper was displayed at the Women’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

design of folding fans and pine branches shows her skill in producing these other styles. 4

I n the 1890s, Sophia Crownfield befriended the artist and illustrator Katharine Pyle, who began her studies at the Art Students League in 1892. Pyle likely recommended Crownfield’s services to the publisher of Florence Bone’s 1910 book The Other Side of the Rainbow, Being the Adventures of OldFashioned Jane. Crownfield produced the frontispiece and illustrations that appear throughout Bone’s book. Other published designs include an uncredited Cheney Brother’s chrysanthemum silk used for a coverlet appearing in The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1911.5

Until the early 1920s, Crownfield exhibited her design work and

participated in several textile design contests where she received cash awards for her submissions. Fifty-seven of Crownfield’s drawings and four silk textiles for Cheney Brothers were gifted to the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in 1937. A larger selection of her drawings and textiles are located at the Decker Library at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Textile samples are also at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

KIMBERLY RANDALL

1. Baltimore City Directory (Baltimore, MD : R. L. Polk & Company, 1888), 274.

2. “Women’s Work in the Applied Arts,” The Art Amateur: A Monthly Journal Devoted to Art in the Household (April 1893): 146.

3. Trow’s (formerly Wilson’s) Business Directory of the Boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx, City of New York (New York: Trow Directory, Printing & Bookbinding Company, 1898), 348.

4. See Google Patents for twenty-one textile designs by Sophia L. Crownfield. patents.google.com

5. Marion Wise, “The Light Bed Coverlet,” The Ladies Home Journal (February 15,

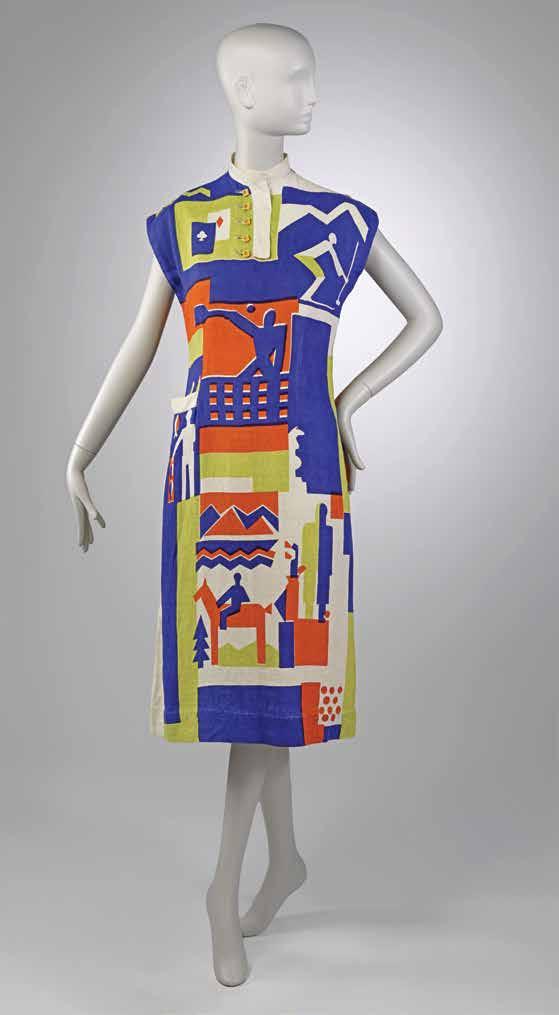

OPPOSITE: SOPHIA LOUISE CROWNFIELD, UNTITLED, UNDATED, SILK, 21 1/4 × 15 1/4 IN. GIFT OF STARLING W. CHILDS AND WARD CHENEY, 1937-59-35, COOPER HEWITT, SMITHSONIAN DESIGN MUSEUM ABOVE: SOPHIA LOUISE CROWNFIELD, STUDY OF SQUASH OR PUMPKIN PLANTS , UNDATED. WATERCOLOR AND GRAPHITE ON PAPER, 10 11/16 × 22 1/16 IN. GIFT OF STARLING W. CHILDS AND WARD CHENEY, 1937-59-33, COOPER HEWITT, SMITHSONIAN DESIGN MUSEUM

Lucia Fairchild Fuller

Lucia Fairchild Fuller (1870–1924) led the American revival of miniature painting both as a practitioner and as a cofounder in 1899 of the American Society of Miniature Painters. She exhibited miniatures regularly to positive reviews, and won bronze, silver, and gold medals at international expositions. She was esteemed by her peers, as reflected in her induction into the American Society of Painters in 1899 and her recognition as an Associate by the National Academy of Design in 1906. Her accomplishments were due to a remarkably sustained dedication to improving her skills over a roughly ten-year period, mostly at the Art Students League, as well as her “characteristic independence of spirit and adventurousness.” 1

Lucia Fairchild—she took the surname of painter Henry Brown Fuller upon their marriage in 1893—began her artistic training in Boston by 1888, under Dennis Miller Bunker at the Cowles Art School. 2 In 1889 she came to the Art Students League and over the next three to four years took classes with William Merritt Chase and Harry Siddons Mowbray.3 Oddly, her registration card for the 1889–90 year lists no classes, but she must have begun with Chase’s painting class. 4 During this and the subsequent year Mowbray taught a Life Drawing and Painting class for men, but not yet for women. The requirement to enter the painting class was a drawing of a head,

which she may have brought with her from Boston. If she had not yet made an acceptable full-length nude drawing for admission to a life class, it is likely she also took antique classes during these early years at the League.5

T hree of Lucia’s four nude figure drawings in the League’s collection bear printed labels on their mounts, indicating they were executed in Mowbray’s life class for women, which he began teaching during the 1891–92 season and continued the following year. 6 The drawings display her command of the figures’ proportions, anatomy, weight distribution, and individualized faces, and were executed with a sensitive and controlled use of line and modeling. Her years of study paid off, and in 1893 she was given the high-profile commission to paint the Women of Plymouth mural for the Women’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.7

T hough her life became increasingly busy, she maintained her ties to the League. She intended to embark on a career as a muralist, but income in this specialization was too unreliable, so she educated herself in the technique of watercolor on ivory and began painting portrait miniatures. 8 At the same time she became pregnant, and in March of 1895 she gave birth to her first child, Clara.9 Her registration card for the 1895–96 season documents