Stephen Ongpin Fine Art

of Seated Figures

Cover:

Henry Moore (1898-1986)

Group

The Approach to Venice or Venice, From the Lagoon No.9

TWO CENTURIES OF BRITISH DRAWINGS, WATERCOLOURS AND OIL SKETCHES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am, as ever, grateful to my wife Laura for her constant support and encouragement, as well as her superb editing skills. I am also greatly indebted to gallery director Alesa Boyle, who managed to contribute to every aspect of this catalogue while at the same time preparing for her nuptials. My splendid colleagues Antonia Rosso and Emma Ricci have provided invaluable assistance in every aspect of preparing this catalogue and the accompanying exhibition. Once again, Andrew Smith has photographed all of the works to very high standards, and has also colour-proofed the catalogue images against the original artworks to ensure that they are as accurate as possible, while Sarah Ricks at Healeys Printers has been her usual indefatigable self in the design and layout of the catalogue. I would also like to thank Jack Wakefield and the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue and the drawings included in it: Deborah Bates, Angus Broadbent, Michelle Ongpin Callaghan, Jane Carter, Alessandra Casti, Chris Cook, Ambroise Duchemin, Cheryl and Gino Franchi, Lizzie Jacklin, Rosie Jarvie, Alice Kim, Annabel Kishor, Thomas Le Claire, Megan Corcoran Locke, Helen Loveday, Rebecca Marks, Marcus Marschall, Rachel Mauro, Pilar Ordovas, Guy Peppiatt, Kathyrn and Rick Scorza, and David Wade.

TWO CENTURIES OF BRITISH DRAWINGS, WATERCOLOURS AND OIL SKETCHES

ONGPIN

Dimensions are given in millimetres and inches, with height before width. Unless otherwise noted, paper is white or whitish.

High-resolution digital images of the drawings, as well as framed images, are available on request, and are also visible on our website.

All enquiries should be addressed to Stephen Ongpin at Stephen Ongpin Fine Art Ltd.

82 Park Street

London W1K 6NH

Tel. [+44] (20) 7930-8813 or [+44] (7710) 328-627 e-mail: info@stephenongpinfineart.com

Stephen Ongpin

JOHN VARLEY OWS

London 1778-1842 London

A View of Conwy Castle, North Wales

Watercolour over a pencil underdrawing. Inscribed I certify that this is an Original Drawing / by Old John Varley / Born 1779 / Died 1842 / Herb. Varley / Grandson / 18th July 1899 in black ink on a label formerly attached to the reverse of the frame. Inscribed Conway Castle in pencil on another label formerly attached to the reverse of the frame. 318 x 226 mm. (12 1/2 x 8 7/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Anonymous sale, London, Bonhams, 7 March 2006, lot 73; Martyn Gregory, London, in 2012.

EXHIBITED: London, Martyn Gregory, An Exhibition of British Watercolours and Drawings 1730-1870, 2012, no.69.

Born in the inner London borough of Hackney, John Varley was apprenticed to a silversmith at the age of thirteen, having been forbidden by his father to train as a painter. Following the death of his father a few months later, however, and with the support of his mother, Varley was able to pursue a career as an artist. In 1798 he exhibited his work for the first time, at the Royal Academy. Not long afterwards he became one of the group of young artists, including Thomas Girtin and J. M. W. Turner, who met regularly at the home of the physician and collector Thomas Monro, who also introduced Varley to a number of other collectors.

It was around the turn of the century that Varley began to take on students and develop a reputation as a fine teacher; among his pupils were Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding, William Henry Hunt, John Linnell and William Turner of Oxford. In 1804 Varley was one of the founding members of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours (later known as the Old Water-Colour Society), and he exhibited numerous works there every year between 1805 and 1842, as well as posthumously in 1843. In 1815 he published his influential book A Treatise on the Principles of Landscape, and his work was to have a profound influence on such later watercolourists as John Sell Cotman, David Cox and Peter de Wint. Varley’s reputation lasted well after his death; in their A Century of Painters of the English School, first published in 1866, Richard and Samuel Redgrave described the artist as ‘a perfect master of the rules of composition.’1

From early in his career, Varley made numerous sketching tours of Wales, and Welsh subjects were a large part of his output throughout his long career. He first visited Wales in 1798, in the company of the landscape painter George Arnald, and returned there often. The artist made several visits to the town of Conwy (or Conway), in Caernarvonshire on the north coast of Wales, and views of the town and its 13th century castle were among his earliest exhibited watercolours, shown at the Royal Academy in 1800, 1803 and 1804.

Built by King Edward I between 1283 and 1287, during his conquest of Wales, Conwy Castle had fallen into ruin by the middle of the 17th century. Its picturesque setting was much admired by artists in the 18th and 19th centuries, and Varley painted numerous views of the castle, several of which were exhibited at the Old Water-Colour Society between 1805 and 1823. The artist was particularly fond of depicting Conwy Castle from a distance, with trees acting as repoussoir elements in the foreground of the composition, as here. One such example, a very large and finished watercolour with a similar distant view of Conwy Castle framed by trees in the foreground, is today in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York2

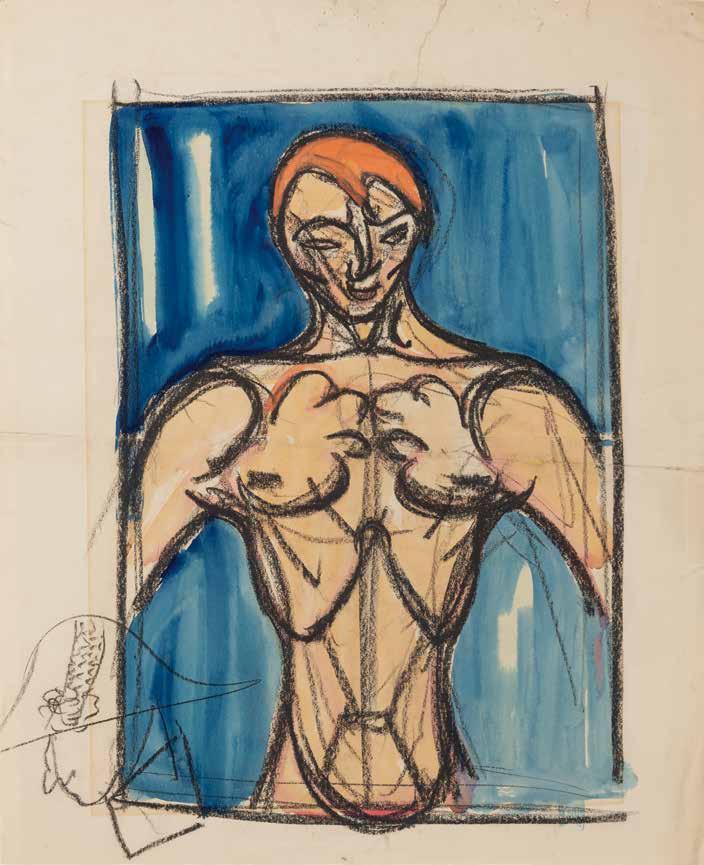

JOHANN HEINRICH FÜSSLI, called HENRY FUSELI RA

Zurich 1741-1825 Putney Hill

Recto: The Quarrel of the Queens: Kriemhild and Brunhild at the Church, from Das Nibelungenlied Verso: Kriemhild and Brunhild, with Siegfried Between Them

Brush and grey and brown washes, heightened with white, over an extensive underdrawing in pencil. The verso in pencil and brown and grey wash, with touches of white heightening. Inscribed and dated P.C. [Purser’s Cross] Augt 05 in brown ink at the lower left. Inscribed (not in the artist’s hand) The Ladies Dancing in pencil on the verso.

464 x 371 mm. (18 1/4 x 14 5/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Private collection, Switzerland, in 1973; Private collection, Germany.

LITERATURE: Gert Schiff, Johann Heinrich Füssli 1741-1825, Zürich, 1973, Vol.I, p.317, pp.638-639, no.1798, Vol.II, fig.1798; Christian Klemm, ‘Friedel’s Love and Kriemhild’s Revenge. Fuseli’s Revels in the Kingdom of the Nibelungs’, in Franziska Lentzsch et al, Fuseli: The Wild Swiss, exhibition catalogue, Zurich, 2005-2006, pp.160-162 (illustrated).

Although born and brought up in Switzerland, the artist and writer Henry Fuseli spent most of his career in England. The son of a Swiss painter of portraits and landscapes, he was educated at the Collegium Carolinum in Zurich, the intellectual and literary capital of Switzerland in the 18th century. Fuseli became part of a highly educated circle that included his fellow student, the poet and physiognomist Johan Kaspar Lavater, and the historian Johan Jakob Bodmer, who was his teacher and first instilled in his young student an abiding love of the works of Shakespeare and John Milton, as well as Dante, Homer and the Nibelungenlied. Fuseli was extremely well read and became proficient in several languages apart from his native German, including English, French, Italian, Latin and Greek. Destined by his father for the church, he was ordained into the Zwinglian Swiss Reformed Church at the age of twenty, together with Lavater. In 1762 Fuseli and Lavater published an attack on a corrupt local magistrate and the following year had to leave Switzerland to avoid its repercussions. After several months in Berlin, Fuseli settled in London in 1764.

While Fuseli had drawn since his childhood, during his early years in London he expressed himself mainly in his writings. In 1768, however, he met Sir Joshua Reynolds, the President of the Royal Academy, who encouraged him to become a painter and to travel to Rome. With the support of several friends and patrons, including the wealthy banker Thomas Coutts, he was able to spend the years between 1770 and 1778 studying in Italy, mainly in Rome. A passionate admirer of Michelangelo and the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel in particular, which he copied extensively, Fuseli became part of a circle of foreign-born artists working in Rome that included Nicolai Abildgaard, Thomas Banks, John Brown and Johan Tobias Sergel. After his return to London he began to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy, enjoying success in the 1780s with such grandiose and inventive compositions as The Nightmare, shown to considerable acclaim in 1782 and arguably his most famous painting. He was inspired by performances of Shakespeare and other works on the London stage, and a theatrical influence is manifest in many of his early paintings. Fuseli continued to enjoy the patronage of Coutts and also received commissions from the Liverpool banker and lawyer William Roscoe. Another early supporter was the influential publisher Joseph Johnson, through whom he met William Blake. Fuseli was elected an Associate of the Academy in 1788 and a Royal Academician in 1790.

Throughout his career, Fuseli’s work remained deeply rooted in literature. From 1786 he produced nine paintings to illustrate John Boydell’s ‘Shakespeare Gallery’, and a few years later began his greatest task; a series of more than fifty paintings of subjects taken from the writings of John Milton. The project took a decade to come to fruition, and the paintings – many of them on a monumental scale – were exhibited, as the ‘Milton Gallery’, in London between 1799 and 1800 but with little commercial

success. Fuseli served as Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy Schools from 1799 to 1805 and again from 1810 onwards, and as Keeper from 1784. Although he was much respected in artistic circles in London, his paintings and drawings were little known outside of a small group of aristocratic private collectors, and he was largely forgotten by the middle of the 19th century. It was not until the centenary of Fuseli’s death that his work became known to a wider audience, when an exhibition of 361 drawings and paintings, mainly from Swiss and English collections, was held at the Kunsthaus in Zurich in 1926. In 1941 an even larger exhibition was held at the same museum, which today houses the most comprehensive collection of Fuseli’s oeuvre.

Fuseli’s intellectual background, which set him apart from almost any other artist working in England at the same time, is reflected in his conception of his own art, and this is especially true in his drawings. Relatively few of his drawings may be related to finished paintings, and most seem to have been done as independent exercises1. As Paul Ganz has noted, in one of the earliest accounts of the artist’s output as a draughtsman, ‘Fuseli’s drawings are less the product of his age than his paintings; they are the direct expression of his creative power and reveal his personal outlook and his fiery artistic temperament…In the drawings the artist’s genius has unfolded itself in a free and unrestricted manner without regard to contemporary taste; they therefore open the way to a proper understanding of his art and reveal what was unusual in it and far ahead of his time. 2 Similarly, a more recent writer has commented that ‘Fuseli concentrated especially on original subjects and inventive interpretations of those subjects, especially in drawings. Indeed, the drawings are the most immediate evidence of the sparkling genius, the tenderness, the intense and highly eccentric individuality that was Fuseli’s.’3

In the early years of the 19th century Fuseli began to depict subjects and characters from the medieval German epic poem the Nibelungenlied. He was well acquainted with the tale; his teacher Bodmer had been the first to publish a portion of the Nibelungenlied in 1755 and he himself owned the first German edition of the full text, published in 1782. (The poem was not translated into English until 1848 and so would have been largely unknown to a British audience.) Fuseli exhibited paintings of scenes from the Nibelungenlied at the Royal Academy in 1807 and between 1814 and 1820, and also wrote a number of poems based on the text.

It was in the year 1805, however, that Fuseli worked most consistently on a series of large, finished drawings of episodes from the Nibelungenlied, of which the present sheet is one. A recurring character in these drawings is that of Kriemhild, the central female protagonist of the story. As one scholar has recently suggested, ‘Kriemhild is Henry Fuseli’s representation of the ideal woman, embodying values of justice and morality.’4 A Burgundian princess, Kriemhild is married to the great warrior prince Siegfried. Their love is shattered when Siegfried is murdered by Hagen, a close friend of Kriemhild’s brother, the Burgundian King Gunther. Kriemhild’s grief is overwhelming, and the remainder of the story is taken up with her search for revenge, culminating in the savage deaths of Gunther and Hagen, and the destruction of the Burgundian kingdom. As Christian Klemm points out, ‘[one] aspect that particularly fascinated Fuseli in the Nibelungenlied [was] Kriemhild’s manically obsessive revenge, which is no less excessive and without restraint than her possessive love. 5

Part of the series of Nibelungenlied drawings executed between May and November 1805, this large sheet represents an episode from the first half of the poem, before the death of Siegfried. Here Kriemhild challenges her rival, the warrior-queen Brunhild, wife of King Gunther. The two women have argued over which has the higher social rank, since Brunhild wrongly believes that Siegfried is Gunther’s vassal, and that therefore she, as the wife of a King, should take precedence. Meanwhile, Kriemhild claims that Siegfried, not Gunther, took Brunhild’s virginity on her wedding night, when he stole her ring and belt as trophies. (Although Siegfried did not, in fact, seduce Brunhild that night, he did steal her ring and belt, with the help of a magical cloak of invisibility.) When both women arrive at the cathedral at the same time, Kriemhild asserts her superior status and enters first.

As Klemm has described the present sheet, Fuseli ‘presents the fight between the two Queens in an elaborately orchestrated climax in front of the church, where Brunhild tries to deny precedence to Kriemhild

and Kriemhild accuses Brunhild of being her husband’s concubine, leading to the tragedy after the mass, when Kriemhild shows the ring and belt Siegfried took from Brunhild on her wedding night...Fuseli was in every way equal to the dramatic mastery with which his literary model employs contrasts to reveal the antagonism of the two rivals; in fact he builds up the situation even further, following his predilection for diametric opposites, by contracting the whole sequence of the narrative into one single scene. Kriemhild, as the wife of the great hero Siegfried, is portrayed all in white apart from the belt which Brunhild, in black, is missing; this woman bright with light who drags the secret concealed in the darkness into the daylight is show frontally, while her opponent in diametrically opposed rear view turns back. Kriemhild strides past her up the steps of the cathedral, showing the ring with a contemptuous gesture. As in the saga, standing between the fighting queens is the object of their dispute, the enigmatic Siegfried: shadow-like, he seems to be more part of than in front of a steeply soaring geometric form, which may be seen in concrete terms as a buttress of the church. But the significance of the scene lies wholly in the abstract expressive content – in the division of the picture plane between the rivals, opening up a height and depth giving the conflict both suspense and inevitability.’6 It is this quarrel between Kriemhild and Brunhild, and the anger which the latter feels at being deceived and dishonoured, that leads her to demand justice from Gunther, who then orders Hagen to kill Siegfried.

The initials P.C. inscribed by Fuseli at the bottom of the sheet indicate that this was one of several works drawn at the country home of his longtime friend, the publisher and bookseller Joseph Johnson, at Purser’s Cross in Fulham. Indeed, most of Fuseli’s Nibelungenlied drawings of 1805 were done at Purser’s Cross. Other drawings of subjects from the Nibelungenlied are today in the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki in New Zealand, the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar and the Kunsthaus in Zurich. As the Fuseli scholar Gert Schiff has noted, ‘In just a few months, mostly at Joseph Johnson’s country estate, he created a series of Nibelungen drawings that are among his finest achievements; had this series not remained fragmentary, this series could have been his masterpiece.’7

The verso of this double-sided sheet shows the figure of Kriemhild traced through from the recto, creating a reversed image, to which the artist has added the figures of Brunhilde and Siegfried in different poses from the recto. This allowed him to experiment with variations to the composition and is typical of Fuseli’s practice. As Ketty Gottardo has written, ‘Fuseli’s frequent practice of tracing his compositions from one side to the other of a sheet in order to obtain a mirror image…happens so frequently in his work that it could almost be considered a trademark of authenticity of the artist’s drawings, in addition to their left-handedness…for Fuseli the point of tracing through from one side of a sheet to the other was not simply about seeing how a composition would appear when turned in the opposite direction. On the contrary, trying out a design on the other side allowed him to experiment, and to play with certain details; at times he would then return to the side drawn first to make changes there…through tracing, Fuseli’s explorations on paper free his fantasy to exploit different ideas.’8

In his Nibelungenlied drawings, ‘Fuseli’s visual representation of Kriemhild is an idealized figure of Justice. She is depicted with an androgynous form consisting of both masculine and feminine features, including a strong physique and a furrowed brow, exuding absolute strength and force, alongside a shapely body and long flowing hair. This androgyny…mixes together strength and femininity…Several of the drawings from the 1805 series present Kriemhild as the largest and most detailed figure in the scene, making her a central and hierarchically important figure. Not only does this emphasize Fuseli’s interest in the character, it also shows the depth of Kriemhild and her journey towards rectifying a wrongful act.’9 Although in Fuseli’s Nibelungenlied drawings the men are usually depicted as antique nudes, the women, and in particular Kriemhild, are shown in contemporary fashions and hairstyles. As has been noted, ‘Fuseli was especially interested in changes in women’s fashions.’10

As has recently been noted, ‘Fuseli would remain an indefatigable draughtsman till the end of his life; and for him drawing would always retain its capacity to operate as a clandestine area of creative freedom – a space where he could be at liberty to break the rules, and give untrammelled expression to his genius. 11

JOHN LINNELL

London 1792-1882 Redhill

Southampton from the River Test near Netley Abbey, Hampshire

Pen and brown ink and watercolour, on a double-page spread of a sketchbook. Signed, inscribed and dated Southampton J Linnell 1819 in brown ink at the lower centre.

162 x 491 mm. (6 3/8 x 19 3/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Sir Lawrence Burnett Gowing, Newcastle and London, by 1968; Thence by descent.

LITERATURE: Frederick Cummings and Allen Staley, Romantic Art in Britain: Paintings and Drawings 1760-1860, exhibition catalogue, Detroit and Philadelphia, 1968, p.238, under no.157; Paris, Petit Palais, La peinture romantique anglaise et les préraphaélites, exhibition catalogue, 1972, p.165, under no.164.

Born in Bloomsbury in London, John Linnell was the son of a gilder, frame-maker and occasional picture dealer, with whom he worked from a young age, having had very little formal schooling. In 1805 he began studying with the watercolourist John Varley and at the Royal Academy Schools. He was also employed as a copyist in the informal artists’ academy established by the collector Dr. Thomas Monro. Linnell first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1807, at the age of fifteen, and in 1809 won a prize for landscape at the British Institution. Between 1813 and 1820 he exhibited at the Old Water-Colour Society (which accepted oil paintings during those years), but although he applied for admission to the Royal Academy every year from 1821 onwards, he was always unsuccessful and eventually gave up in 18411. Even though he established his reputation as a portrait painter, as he noted in an unpublished memoir, ‘portraits I painted to live, but I lived to paint poetical landscape.’2 From the late 1840s onwards Linnell concentrated on landscapes, eventually becoming the most successful landscape painter in England following the death of Turner. Linnell built a home and family estate at Redhill, near Reigate in Surrey, where he lived and worked for thirty years, until his death at the age of ninety. His three sons – James, James Thomas and William – were all artists.

Linnell visited the port city of Southampton in September and October of 1819. He stayed there as the guest of the painter and engraver David Charles Read, who introduced him to his patron Chambers Hall, of Elmfield Lodge in Southampton. Linnell produced several studies of the landscape around Southampton Water and the Itchen and Test rivers, which he later developed into oil paintings. Drawn on the double-page spread of one of the artist’s early sketchbooks, this sunset view depicts Southampton in the distance, seen from Netley Abbey on the other side of the estuary of the River Test. Some years later, this watercolour was used as a reference study for a small oil painting (fig.1) commissioned from Linnell by Chambers Hall in 18253. The vibrant hues of sunset in the finished painting delighted Hall; as he wrote to the artist, ‘You have indeed realised ideas which I had long cherished of a most magnificent effect of nature, the interest in which is heightened to me from the circumstance of locality.’4

As the Linnell scholar Katherine Crouan has noted of the artist’s early works, ‘The skill and power which Linnell brought to his landscape studies from 1811 resulted in a plein air freshness, the most convincing local colour, a remarkable handling of sunlight and shade, and an ability to convey the expanse of landscape through the sum of its minute particulars…With rare exceptions, Linnell never parted with his studies in oil or watercolour, and he didn’t sell them. They were the raw material for his painting, essential for their documentary value but not in themselves art…However, although Linnell thought of his most intensely naturalistic work as merely factual information about nature, to be re-organised into a personal statement, the sketches he made between 1811 and 1819 take naturalism to the level of a visionary intensity.’5

WILLIAM HENRY HUNT OWS

London 1790-1864 London

Sunset with Distant Trees

Watercolour. Signed W. HUNT in brown ink at the lower right. 94 x 128 mm. (3 3/4 x 5 in.)

PROVENANCE: Cyril and Shirley Fry, London and Snape, Suffolk.

LITERATURE: John Witt, William Henry Hunt (1790-1864): Life and Work, London, 1992, p.150, no.76 (‘Trees Outlined Against a Brilliant Sunset’), where dated 1820-1830.

EXHIBITED: Norwich, Castle Museum and London, Maas Gallery, William Henry Hunt 1790-1864: Water-colours and Drawings from the Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Cyril Fry, 1967, part of no.34 (‘Three Studies of Sunsets, Water-colour, 2 signed. circa 1820-25’); London, Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, ‘Simplicity & Intensity’: Drawings and Watercolours by William Henry Hunt, 2024, no.35.

One of the finest British watercolourists of the 19th century, William Henry Hunt was born with weak and deformed legs that prevented him from physical labour, although from his youth he exhibited a talent for drawing that was to lead to a long and highly successful career as an artist. He was apprenticed to John Varley for a period of some seven years, while also studying at the Royal Academy Schools, and became close friends with two of his fellow students in Varley’s studio, John Linnell and William Mulready, with whom he went on sketching expeditions along the Thames. Like Linnell, Hunt was part of the informal drawing academy established by Dr. Thomas Monro, and was able to study Monro’s collection of watercolours. Monro became a close friend of the artist, eventually owning nearly 170 of his works and often inviting him to stay at his country home in Bushey in Hertfordshire. It was through Monro that the artist met the 5th Earl of Essex, who in the early 1820s commissioned Hunt to draw the house, grounds and servants at Cassiobury Park, near Bushey. The artist also did the same for another aristocratic patron and landowner, the 6th Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth. In general, however, and perhaps due to his infirmity, Hunt did not travel much around Britain, and was content to work relatively close to London.

In the early part of his career, between 1807 and 1825, Hunt showed both watercolours and paintings at the Royal Academy, but following his election as an Associate of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours in 1824 and gaining full Membership two years later, he abandoned working in oils to concentrate fully on watercolours. Between 1824 and his death forty years later, Hunt exhibited well over 750 works at the Society of Painters in Water-Colours, averaging some twenty-five a year during his most productive period of his career, between 1831 and 1851.

Among Hunt’s occasional pupils was John Ruskin, who was a lifelong admirer of his work and often mentioned him in his lectures and writings1. The later 1830s found Hunt producing interior scenes, studies of country folk and still life subjects, particularly of fruit, flowers and bird’s nests, painted with a particular fineness and delicacy that meant that the artist worked very slowly. Characterized by an innovative technical mastery, these detailed and highly finished still life subjects proved especially popular with collectors, and earned the artist the sobriquet ‘Bird’s Nest’ Hunt. Hunt’s watercolours were much admired by critics such as F. G. Stephens and Ruskin, who regarded him as the finest still life painter of the day. His watercolours were widely collected in his lifetime, fetching increasingly higher prices, and by the 1840s were also being engraved.

Although Hunt rarely dated his watercolours, this and the following sheet are likely to be relatively early works of the 1820s or 1830s. By the end of the 1830s, the artist’s poor health had led him to abandon landscape subjects in favour of interior genre subjects, figure studies and still life compositions.

actual size

WILLIAM HENRY HUNT OWS

London 1790-1864 London

Sunset After a Storm

Watercolour, with touches of white heightening, on blue paper. 86 x 118 mm. (3 3/8 x 4 5/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Cyril and Shirley Fry, London and Snape, Suffolk.

LITERATURE: John Witt, William Henry Hunt (1790-1864): Life and Work, London, 1992, p.151, no.80 (‘Sky and Trees’), where dated 1820-1830.

EXHIBITED: Norwich, Castle Museum and London, Maas Gallery, William Henry Hunt 1790-1864: Water-colours and Drawings from the Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Cyril Fry, 1967, part of no.34 (‘Three Studies of Sunsets, Water-colour, 2 signed. circa 1820-25’); London, Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, ‘Simplicity & Intensity’: Drawings and Watercolours by William Henry Hunt, 2024, no.36.

This and the previous watercolour may have been done during one of Hunt’s stays with Dr. Thomas Monro in Bushey early in his career, when Monro is said to have paid him 7s. 6d. a day for his sketches from nature. Alternatively, they may have been done during the winters in the coastal town of Hastings, where the artist went for his health during the early part of his career, and where he spent some time sketching out of doors. (This was despite the fact that his disability seems to have made it difficult for him to move around easily, and indeed he is recorded as sometimes being transported in a barrow, used as a sort of makeshift wheelchair, from which he would sketch.) As the 19th century poet and critic William Cosmo Monkhouse has written of Hunt, Some of his best landscapes were also painted at Hastings, which he visited regularly for thirty years, taking up his residence in a small house in the old town overlooking the beach...He was debarred by his infirmity from active exercise, and in later years his health prevented him from drawing in the open air. Many, if not most, of his landscapes were drawn from windows.’1

In his 1982 monograph on the artist, Sir John Witt noted of Hunt that ‘in his early impressionable days [he] was steeped in the spirit of the eighteenth century, and in his early landscapes and views of churches, many done with reed pen and watercolour, and others in pure watercolour, his best qualities as an artist can be seen. He possessed an innate and unobtrusive sense of composition which never deserted him. There is a liveliness and spontaneity in these early landscapes and in his seascapes and shore scenes around Hastings which he gradually lost as he came in his later years, and for good financial reasons, to concentrate on plums and grapes and birds’ nests. These early works which have only recently begun to become widely known and appreciated should rank far higher in the hierarchy of nineteenth-century watercolours…for the present writer, Hunt’s finest and most memorable works are his early landscapes…These by their directness and unerring sense of composition best convey Hunt’s passionate love of nature and his skill in portraying it in loving and simple terms. His talents as an all-round watercolourist deserve a far greater and wider recognition than they have hitherto been accorded.’2

The art dealer Cyril Fry (1918-2010) specialized in 18th and 19th century British works on paper and worked from a gallery in London between 1967 and 1986, and later in Aldeburgh in Suffolk. He and his wife Shirley were passionately devoted to Hunt’s work. They assembled a large and varied collection of his oeuvre, and organized two exhibitions of his watercolours in 1967 and 1981.

actual size

DAVID COX OWS

Birmingham 1783-1859 Harborne

The Porte Saint-Denis, Paris

Watercolour over a pencil underdrawing. A repaired tear at the upper right edge of the sheet. 366 x 260 mm. (14 1/2 x 10 1/4 in.)

Watermark: T. EDMONDS 1825.

PROVENANCE: John Herbert Roberts, 1st Baron Clwyd, Abergele, Denbighshire, Wales; By family descent to a private collection; John Manning Gallery, London, in 1960; Andrew Wyld, W/S Fine Art, London, in 2007; Lowell Libson, London, in 2012; Private collection.

LITERATURE: Horace Shipp, ‘Current Shows and Comment. Sure Eye, Sure Hand’, Apollo, March 1960, illustrated p.61; London, Spink-Leger Pictures, ‘Air and distance, storm and sunshine’: Paintings, watercolours and drawings by David Cox, exhibition catalogue, 1999, unpaginated, under no.30; Scott Wilcox, Sun, Wind, and Rain: The Art of David Cox, exhibition catalogue, New Haven and Birmingham, 2008-2009, p.176, no.47; London, Lowell Libson Ltd., Lowell Libson Ltd., 2012, pp.114-115.

EXHIBITED: London, John Manning Gallery, Spring Exhibition: English and Continental Drawings, March 1960; New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, and Birmingham, Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Sun, Wind, and Rain: The Art of David Cox, 2008-2009, no.47.

Among the finest watercolourists in England in the first half of the 19th century, David Cox was trained as a theatrical scene painter in Birmingham before settling in London in 1804 and establishing himself as a watercolourist. Much influenced by the work of John Varley, with whom he may have briefly studied, Cox exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy in 1805. Between 1809 and 1812 he showed his work at the Associated Artists in Watercolours, and in 1812 was admitted to the Society of Painters in Water-Colours, where he exhibited almost every year for the remainder of his long and productive career. Almost all of his sketching trips were in England and Wales, and he only rarely travelled abroad. A celebrated teacher and drawing master, Cox published several technical manuals for amateur watercolourists, including A Treatise on Landscape Painting and Effect in Water Colours, Progressive Lessons on Landscape for Young Beginners and The Young Artist’s Companion.

Cox enjoyed a successful career which lasted over half a century, exhibiting numerous watercolours and the occasional oil painting in London each year. Between 1844 and 1856 he spent part of every summer or autumn in the small village of Betws-y-Coed in the Conwy valley in North Wales, which he used as a base for sketching expeditions, sometimes in the company of younger artists such as George Price Boyce. A stroke, suffered in 1853, left him temporarily paralyzed, and although he recovered, his eyesight began to suffer and by 1857 had started to fail completely. While his output lessened considerably following his stroke, he continued to be well represented – usually with earlier works – at the annual exhibitions of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. An account of his career, published shortly after his death, described Cox as ‘pre-eminent among landscapists, and the founder of a school of landscape painting purely English, but new to England itself when he created it.’1 Two large retrospective exhibitions, each numbering several hundred works, were held in Liverpool in 1875 and Birmingham in 1890.

David Cox travelled to the Continent only three times in his career, visiting Holland and Belgium in 1826 and making two excursions to France, in 1829 and 1832. This superb watercolour dates from the earlier of his two trips to France, when the artist undertook his first (and only) visit to Paris. Accompanied by his son, Cox spent several days in Calais, Amiens and Beauvais before arriving in the French capital. They had intended to travel further into France and make a tour along the Loire to Orléans, but a bad fall and a sprained ankle meant that the artist remained in Paris for six weeks. He spent this time exploring the city in hired carriages from which he sketched.

The present view was taken from the rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis, looking south towards the Porte Saint-Denis, a triumphal arch built on the site of one of the great gates of the city. Commissioned by Louis XIV from the architect François Blondel and the sculptor Michel Anguier, the Porte Saint-Denis was built in 1672 and is the second largest triumphal arch in Paris, after the Arc de Triomphe (which was still under construction when Cox visited the city), and was the entry point into the city for most visitors coming from Britain. As the English painter and diarist Joseph Farington, writing in 1802, noted of the Porte Saint-Denis, ‘We now saw the character of one part of Paris. Approaching the gate the view to a painters eye is picturesque, the forms, & variety & colour of the buildings & the arch which is lofty, make an assemblage very well calculated for a picture.’2

Among the lively watercolours produced by Cox during his stay in Paris in 1829 are examples in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, the Leeds Art Gallery, the Tate in London, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as in several private collections. As Stephen Duffy has noted, ‘The sketches that Cox made during his stay in Paris, and in the other French cities he visited in 1829, are among his most impressive works. The experience seems to have inspired him to produce works of exceptional brilliance and vigour, in which he paid unusually close attention to topographical accuracy.’3 The artist exhibited only a handful of Parisian subjects at the Society of Painters in Water-Colours, however; two in 1830, five the following year, and one in 1838. As the scholar Scott Wilcox has pointed out, ‘the body of Parisian sketches, which have come to be among the most highly regarded of Cox’s watercolours, were in his own lifetime known only to a small coterie of family and friends.’4

An unfinished variant of this watercolour view of the Porte Saint-Denis (fig.1), formerly in the collection of H. S. Reitlinger, was sold at auction in 20035. As Wilcox has noted of the present sheet, ‘Among his Parisian subjects, Cox’s view of the Porte St. Denis is unusual in that it exists in at least two versions. While the present work with its forceful pencil drawing and bold use of watercolor is typical of the works produced during his weeks sketching in the streets of Paris, the other version (private collection)…with its more controlled pencil outlines and application of watercolor seems less a sketch than a piece intended for exhibition and/or sale but left unfinished.’6 A third version of the composition – a smaller watercolour, signed and dated 1831 and worked up from sketches made years earlier in Paris – recently appeared at auction in London7

The first known owner of the present sheet was the Welsh Liberal politician Herbert Roberts, 1st Baron Clwyd (1863-1955), who owned a number of other watercolours by David Cox, including a study of clouds now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

WILLIAM ROXBY BEVERLEY

Richmond 1811-1889 Hampstead

Fishing Boats on a Beach

Watercolour over a pencil underdrawing. Signed and dated WBeverley [?] Augt. / 28 1835 in brown ink at the lower right.

258 x 358 mm. (10 1/8 x 14 1/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Michael Ingram, Driffield Manor, Driffield, Gloucestershire; His posthumous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 6 June 2007, part of lot 248; Private collection, England.

The son and grandson of actors and theatre managers, William Roxby Beverley began his career as a painter of scenery for the theatre and continued to work in this field throughout his life. Indeed, his reputation was established by his renown as a scene painter, and in particular his skill in rendering atmospheric effects. (An obituary published in the Daily Telegraph in 1889 described Beverley as the ‘long acknowledged chief and doyen of English scenic artists’, although the author also noted his ‘noble water-colours done in leisure hours.’) Beverley began to produce landscape watercolours under the influence of Clarkson Stanfield, also a former scenographer, whom he joined on sketching tours, as well as Richard Parkes Bonington. Although Beverley began exhibiting his marine watercolours from 1831 onwards, he continued to make his living as a scene painter at the Theatre Royal in Manchester and, occasionally, as an actor. By 1846 he had settled in London, and was engaged as scenic director at several theatres, notably at the Lyceum, Covent Garden and Drury Lane. By comparison with many of his fellow artists, Beverley produced relatively few watercolours, since he was kept busy by the demands on his time as a theatrical painter. Nevertheless, as one early critic had noted, ‘Beverley painted water-colour pictures of rare and delicate beauty, works which alone should suffice to win for him a place in the front rank among our masters of water-colour art.’1

Beverley worked for his entire career in England, although he is known to have visited France and Switzerland. He was particularly fond of coastal scenes and depictions of such port towns and fishing communities as Scarborough, Eastbourne, Hastings and Sunderland, and also painted views in London, the upper Thames valley and the Lake District. Common to many of his watercolours is a particular interest in skies and atmospheric effects; a legacy of his training as a scene painter. Beverley’s landscape watercolours, which were almost always of English coastal scenes, were regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1865 and 1880. He also showed his work at such commercial galleries as the Dudley Gallery, charging up to £400 for his finished watercolours.

An early work, the present sheet is a fine example of Beverley’s lively watercolour sketches. The scene depicted is likely to be found in one of the fishing communities in the Northeast coast of England, where he made several sketching tours. In one of the first critical reappraisals of the artist’s oeuvre, published in 1921, Frank Emanuel noted that ‘there are numbers of charming little compositions and studies of boats and shipping, of which he had the completest practical knowledge, down to the smallest detail. Indeed, his knowledge of shipping was equal to that of any of the specialists in marine work...His drawing of the subtly curving lines of hulls, his delineation of spars and rigging, is absolutely faultless, and put in with a line unrivalled for certainty and purity.’2 Similarly, a later writer opined that ‘Beverley was primarily a marine artist and his best works, I think, are his watercolours of coastal scenes, with boats either on the beach or off-shore. He did many such works in the early morning or at sunset and was masterly at depicting the sun just peeping through the dawn clouds…His draughtsmanship was first class. A close examination of some of his fishing boats, for example, shows what Martin Hardie described as a “structure of crisp and finely descriptive drawing”; the hulls, masts and rigging are put in with an accurate, confident line…Technically, too, his boats are good enough to withstand the scrutiny of any sea-going man.’3

PETER DE WINT OWS

Hanley 1784-1849 London

Wooded Hills and a Valley near Lowther, Westmoreland

Watercolour over traces of an underdrawing in pencil. Inscribed Lowther 433 on the verso, backed. 457 x 572 mm. (18 x 22 1/2 in.)

PROVENANCE: The artist’s studio sale, London, Christie’s, 22-28 May 1850, lot 433 (as ‘Lowther’, bt. Smith for £5,15.6); John F. Laycock; Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 11 July 1972, lot 26; Cyril and Shirley Fry, London and Snape, Suffolk.

LITERATURE: Hammond Smith, Peter DeWint 1784-1849, London, 1982, p.149; Andrew Wilton and Anne Lyles, The Great Age of British Watercolours 1750-1880, exhibition catalogue, 1993, p.224, no.121, illustrated pl.238 (where dated c.1840-1845).

EXHIBITED: London, Fry Gallery and Brighton, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, Peter de Wint (1784–1849): Bicentenary Loan Exhibition, 1984-1985, no.33; London, Royal Academy and Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art, The Great Age of British Watercolours 1750-1880, 1993, no.121 (as Trees at Lowther, Westmoreland).

The son of a Staffordshire physician of Dutch descent, Peter De Wint was trained in the London studio of the portrait painter and engraver John Raphael Smith. There he soon met the young artist William Hilton from Lincoln, who was to become a lifelong friend, as well as his brother-in-law. Released from his apprenticeship in 1806, De Wint studied briefly with the landscape artist John Varley but in general seems to have begun his independent career without further training. He did have access to the private collection of the noted connoisseur Dr. Thomas Monro, whose works by Thomas Girtin he found particularly appealing. In 1809 De Wint became an Associate member of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours, rising to full membership the following year, and he showed numerous works there almost yearly between 1810 and his death in 1849. He also exhibited landscape paintings and watercolours at the Royal Academy, the British Institution and the Associated Artists in Water Colours. He soon found favour with critics, and he began to establish a particular reputation, with regular sales to a large number of devoted patrons and collectors. From 1827 onwards De Wint’s wife Harriet maintained a comprehensive list of the artist’s output, noting the locations depicted, the purchasors of the works and the prices paid for them.

De Wint undertook sketching tours throughout England and Wales, with a particular fondness for his native Lincolnshire, as well as Derbyshire, Yorkshire and the Lake District. (He never seems to have had much desire to travel abroad, however, and his only foreign tour was a brief visit to Normandy in 1828.) He was fond of sketching out of doors, and among his favourite subjects were rivers and streams, harvest scenes and pastoral views. Somewhat unusually, however, De Wint seems to have almost never signed or dated his works, even those sent to exhibitions. He produced a significant number of topographical landscape prints, many of which were published in book form. The artist died in 1849, at the age of sixty-six. In the opinion of Walter Armstrong, in his Memoir of Peter De Wint, published in 1888, ‘De Wint’s place in English art is with Constable and David Cox. Like Constable he saw instinctively the true capabilities of English landscape, and, like Cox, the true powers of the medium in which he worked. His coup d’oeil for a subject was even finer than theirs. He seized with a quicker instinct on the best point of view, the most rhythmical combination of line, the most effective chords of colour. His sense of unity was almost unerring. In his most hasty sketches, no less than his finished pictures, there is ever a central idea led up to and enhanced by every touch of his brush.’1 Writing some thirty years later, a fellow watercolourist added that ‘No artist ever came nearer to painting a perfect picture than did Peter DeWint. His sense of colour was more brilliant, his choice of subject matter more apt, and his judgment as to the exact time when a picture should be left, better than any of his contemporaries.’2

Datable to the late 1830s or early 1840s, this exceptionally large and freely painted watercolour depicts a view near Lowther Castle in Cumbria, the seat of one of De Wint’s foremost patrons, the MP and collector William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale (1787-1872). The Earl, who inherited Lowther Castle in 1802, was a keen supporter of artists and writers, including William Wordsworth. De Wint was a frequent visitor to Lowther Castle and was occasionally employed as a drawing master to the Earl’s grandchildren. The artist produced numerous views of the Lowther estate between 1834 and 1843, several of which were exhibited at the Society of Painters in Water-Colours. As De Wint’s widow (and first biographer) noted of him, ‘His love for nature was excessive, and his study from nature constant and unwearied. He never tired of sketching, which was his great delight…He preferred the North of England, and spent much time in Yorkshire, Cumberland and Westmorland. He was frequently at Lowther Castle, where, through the kindness of the then Earl of Lonsdale and his family, he was enabled to visit the most remote and picturesque spots in that wild and beautiful district.’3

In an early account of the artist’s life and work, published in 1891, Gilbert Redgrave noted of De Wint that ‘His method in water-colours was very simple. He used as a rule only ten pigments:- Yellow Ochre. Gamboge. Vermilion. Indian Red. Purple Lake. Brown Pink. Burnt Sienna. Sepia. Prussian Blue. Indigo…De Wint made a practice of painting on ivory-tinted Creswick paper, which he kept rather wet…He laid in his effect at once in broad flat washes, and he had a fine sense of colour, and a most keen appreciation of the tints and harmonies of nature, which his rich and flowing brush enabled him to carry out swiftly, with great freshness and purity…In his feeling for breadth and in the fine sense of colour De Wint’s water-colour art is truly original…Many of De Wint’s sketches seem to have more freshness and ease than his more elaborate and finished compositions. The very onceness of his sketches made out of doors has in it a most peculiar charm.’4 More recently, the scholar Andrew Wilton has written that ‘De Wint’s work is characterised by a warm range of browns and greens that obviously derives from [Thomas] Girtin; later, he varied this with touches of unmixed red or blue. But he did not make the study of climate a priority. His chief concern remained the creation of subtle and beautifully articulated compositions based on stretches of open or wooded country, often in the broad Wolds of his own Lincolnshire…When well preserved, his watercolours often display fine atmospheric effects.’5

The present sheet was among a group of around five hundred sketches, drawings from nature, and finished watercolours from De Wint’s studio – including sixteen views of Lowther Castle and the surrounding park – that were sold at auction and dispersed the year after the artist’s death, for a total of £2,364. A later owner of this fine watercolour was the art dealer Cyril Fry (1918-2010), who established a gallery, specializing in 18th and 19th century British works on paper, in London between 1967 and 1986, and later in Aldeburgh in Suffolk. Fry acquired the present sheet for his personal collection, which included a number of very fine works by De Wint, an artist he particularly admired.

Among stylistically comparable watercolours by Peter De Wint of the same period is a Wooded River Landscape in the Art Institute of Chicago6. Another comparable view near Lowther, of the same size as the present sheet, is in the Hickman Bacon collection7

JOSEPH

MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER RA

London 1775-1851 London

The Approach to Venice or Venice, from the Lagoon Watercolour, with touches of pen and brown and red ink. 221 x 319 mm. (8 3/4 x 12 1/2 in.)

PROVENANCE: Thomas Griffith, London and Norwood, Surrey; By descent to his daughter, Jemima Lardner Griffith, Rochester, Kent; Probably her sale, London, Christie’s, 4 July 1887, lot 193 (‘Approach to Venice’, sold for 150 gns. to Agnew’s); Thomas Agnew and Sons, London; Acquired from them on 6 July 1887 by Thomas Stuart Kennedy, Park Hill, Wetherby, Yorkshire, and thence by descent to his wife Clara Thornton Kennedy, Harrogate, Yorkshire; Haddon C. Adams, Merton Park, London; Thence by family descent until 2025.

A new and fascinating addition to the corpus of views of Venice produced by J. M. W. Turner throughout his career, this fine and atmospheric watercolour is a noteworthy rediscovery that can be closely associated with a sketchbook used by the artist on his last visit to the city on the lagoon. In the course of his lifetime, Turner travelled to Venice just three times, the first time for a few days in September 1819, when he was forty-four years old. He was there again for just over a week in the late summer of 1833, and made a final visit in August 1840, when he stayed for a fortnight. (It was during this last visit that a fellow artist, William Callow, who was staying at the same hotel as Turner, recalled, ‘One evening whilst I was enjoying a cigar in a gondola I saw Turner in another one sketching San Giorgio, brilliantly lit up by the setting sun. I felt quite ashamed of myself idling away my time whilst he was hard at work so late.’1) Although he spent a total of less than four weeks in Venice during the course of his life, Turner painted Venetian subject pictures throughout much of his later career, exhibiting at least one such painting at the Royal Academy almost every year between 1833 and 1846. It was only after Turner’s death in 1851, however, that his remarkable watercolours of Venice came to light, in sketchbooks or loose sheets found in the artist’s studio, almost all of which are now part of the Turner Bequest at the Tate. Long regarded as a particular high point of Turner’s late work, the artist’s Venetian watercolours number around 150 in total, almost all today in museum collections, to which may now be added the present sheet.

As the pioneering Turner scholar A. J. Finberg, writing in 1930, noted, ‘Though the number of Turner’s Venetian paintings and drawings is not very impressive when compared with the total of his enormous output, yet the works themselves, dealing as they do with a single and clearly-defined subject-matter, form a very interesting and important series. I believe this series, especially the water-colours, is more generally liked and admired at the present time than any other group of his works…There is something in Turner’s Venetian drawings and paintings which appeals with peculiar force to the artist, to the art-critic, and to the art-loving public of to-day.’2 More recently, Martin Butlin has agreed that ‘Turner’s Venetian subjects, both in oil and watercolour, are now amongst the most sought after of his works.’3

Another scholar, Luke Herrmann, has written of Turner’s third and final stay in Venice, in 1840, that ‘As well as making more rapid pencil notations…in three small sketchbooks,…he used larger roll-sketchbooks (which could be rolled up and kept in a pocket) to work in watercolours, very probably on the spot. These late Venetian watercolours, of which some two dozen were removed from the sketchbooks and sold during Turner’s lifetime, are among the artist’s supreme achievements in the medium of which he was such a complete and unrivalled master. Taken as a whole they provide the most engrossing survey of the unique character, atmosphere, and light of Venice; seen individually each one is an outstanding achievement in its own right.’4

It appears that Turner used two identical soft-backed sketchbooks (known as roll-sketchbooks) on his 1840 tour to Venice. One of these – sometimes called the ‘Grand Canal and Giudecca’ sketchbook and containing twenty-one sheets, aptly described as ‘the most perfect, inventive and dream-like of Turner’s watercolours of Venice’5 – is today part of the Turner Bequest at the Tate6. The Tate sketchbook

consists of off-white Whatman paper in sheets measuring approximately 222 x 322 mm., about half of which are watermarked 1834. A second, now dismembered roll-sketchbook of the same Whatman paper, known as the ‘Storm’ sketchbook, appears to have been broken up after Turner’s death. As has been noted, ‘It has sometimes wrongly been suggested that these leaves [from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook] were also part of TBCCCXV [the roll-sketchbook in the Turner Bequest]. However, few of Turner’s late roll sketchbooks contained more than twenty-four sheets, which argues strongly for a second sketchbook; as does the fact that these sheets became separated from the main group of Venetian studies in the Bequest. 7 As Ian Warrell further notes, ‘The second of the Venetian roll sketchbooks contained a number of images, now widely dispersed, that were more fully developed than those in its companion [in the Tate].’8 As the paper historian and analyst Peter Bower has confirmed, the present sheet is on the same paper as the ‘Grand Canal and Giudecca’ and ‘Storm’ sketchbooks, and must have come from the latter.

The late, ephemeral watercolours from the ‘Storm’ roll-sketchbook, amounting to at least twenty sheets and including the present example, were removed and sold to collectors through Turner’s agent and dealer Thomas Griffith, probably after the artist’s death. At least six of the watercolours were purchased by John Ruskin, of which three were later presented by him to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and three to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Other watercolours from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook, all outside the Turner Bequest, are today in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the British Museum in London and the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, as well as in a handful in private collections.

As another scholar has noted of the Venice sketchbooks, ‘With the group of watercolours from the roll sketchbook there are wide variations of style and mood, suggesting that Turner was deliberately exploring a range of responses to the city and its setting.’9 It is sometimes difficult to determine the precise views depicted, since Turner’s intention was mainly to capture fleeting effects of light and colour. While the prominent bell tower in the centre of this composition may at first glance be thought to be the Campanile in the Piazza San Marco, the lack of any identifiable buildings near it, such as the Doge’s Palace or the church of Santa Maria della Salute, or indeed the entrance to the Grand Canal, would suggest that Turner was here depicting a different view altogether. Ian Warrell has suggested that the bell tower may be that of the church of San Francesco della Vigna, in the northeastern part of Venice. If so, then the large squarish building to its right in this watercolour could be the nearby church of San Lorenzo, with the great semi-circular Diocletian window dominating its façade, with Turner viewing the scene from a gondola on the lagoon, near the cemetery island of San Michele. As has been noted, ‘Turner developed a fascination for the city’s profile as seen from the broad expanses of adjacent water... even when restricting himself to the islands closest to the Bacino, Turner discovered vantage points that allowed him to frame the city in novel ways.’10

Not long after Turner’s final visit to Venice in 1840, a railway bridge was constructed that connected the city with the mainland for the first time. As Warrell has pointed out, ‘Turner was fortunate in being among the last generation of travellers to experience Venice as a city that was still completely separate from the surrounding terra firma…the wide spaces of the lagoon were stimulating for Turner, liberating him from the constrictions of more contained outlooks within the city. Here sea and sky become as one and seem to extend without limits in a way that is timeless.’11

Similarly, Finberg has noted of the late Venetian watercolours that ‘The parts of all these drawings in which Turner seems to take most interest are the sea and the sky…he finds more pleasure in them than in the architecture or the boats or figures. The surface of the water, in particular, is always struck in decisively, and its varying shades of blue and green evidently please him.’12 This can be seen both in this previously unpublished sheet and in a closely comparable watercolour of A Storm on the Lagoon in the British Museum13, which comes from the same roll-sketchbook. As Warrell has written of the British Museum Storm on the Lagoon, in terms equally applicable to the present sheet, [several] watercolours from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook chart the arrival of a late-afternoon squall…In the study now in the British Museum, a gondolier seeks shelter in the Grand Canal from the tossing waters of the Bacino. Whether fortuitously,

or as a result of his observations, the opaque jade green that Turner uses in this work unerringly replicates what occurs when a storm aerates the Lagoon during a sudden downpour…It is as though, having returned to the [Hotel] Europa wet and dripping after being caught in the storm, he needed to work through the impressions that were still so vivid and fresh.’14

Turner here used differing, subtle shades of blue-green watercolour to depict the waves in the foreground and the ribbed clouds above, with some pale red washes added towards the top of the sheet. Also evident here is another particular characteristic of the artist’s late Venetian watercolours; the use of red tones, applied with a fine pen or tip of a brush dipped in ink or watercolour, to delineate the topography of the city in the far distance, allowing architectural features to stand out against the overall bluish tonality of the water and sky. This is seen in several other watercolours from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook of 1840, such as Venice, The Grand Canal Looking Towards the Dogana in the British Museum15 and Venice, The Mouth of the Grand Canal in the Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art16

The first recorded owner of the present sheet was the art dealer and collector Thomas Griffith (17951868), who from the 1830s onwards acted as Turner’s agent. Griffith was trained as a lawyer but never practiced, despite being admitted to the Inner Temple in 1827. The same year he was entrusted with the sale of some of Turner’s finished watercolours for the Picturesque Views in England and Wales series. A collector himself, Griffith was also known as a supporter of artists17. It was at his home in 1840 that John Ruskin was first introduced to his hero Turner, and it was around the same time that Turner began to engage Griffith with handling the sales of some of his oil paintings, while he was also instrumental in marketing Turner’s late Swiss watercolours of the early 1840s. Griffith owned at least one other of Turner’s 1840 Venetian watercolours from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook; a view of the Grand Canal with Santa Maria della Salute which is now in a private collection18. At his death in 1868, his collection of watercolours and drawings by Turner passed to his unmarried daughter Jemima Lardner Griffith, and were sold by her at auction in London in 1887. One of the major buyers at the sale was the Yorkshire industrialist Thomas Stuart Kennedy (1841-1894), who seems to have acquired the present sheet, through the dealers Agnew’s, either at, or very shortly after, the 1887 auction.

This atmospheric watercolour of Venice later entered the collection of the bridge engineer Haddon Clifford Adams (1898-1971), who was a noted collector of drawings, books, documents and ephemera by John Ruskin. (As Adams stated, in a letter of 1931, ‘collecting Ruskin is my one luxury.’). Adams’s collection of Ruskiniana was bequeathed to the Ruskin Galleries at Bembridge School on the Isle of Wight and is now housed in the Ruskin Library at Lancaster University. Although Adams probably acquired the present sheet, sometime in the 1930s, as a work by Turner (and hence it was not included in his Ruskin gift to Bembridge), its correct attribution seems to have been forgotten after his death. Its recent reappearance as a new addition to the corpus of Turner’s late Venetian watercolours, from the ‘Storm’ sketchbook broken up by Griffith, is therefore an event of considerable significance.

JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER RA

London 1775-1851 London

The Lauerzersee with the Ruins of Schwanau and the Mythens Watercolour over an underdrawing in pencil, with pen and grey ink, with scratching out. 227 x 287 mm. (8 7/8 x 11 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Given by the artist to Mrs. Sophia Caroline Booth, Margate and London; By descent to her son, Daniel John Pound; By descent to his widow, Mary Anne Pound, and given by her to Alfred and Kate Austin, Hove, Sussex; Their anonymous sale (‘presented by J. M. W. TURNER, R.A., to MRS. POUND, and given by her son to the present owner.’), London, Christie’s, 11 June 1909, lot 185 (as ‘A View on the Rhine’, bt. Agnew’s for £346.10); Thomas Agnew and Sons, London; Acquired from them by Walter H. Jones, Blakemere Hall, Northwich, Cheshire and Hurlingham Lodge, Fulham, London; By descent to his widow, Maud Jones, Hurlingham Lodge, London, and Aberuchill Castle, Perthshire, Scotland; Her posthumous sale, London, Christie’s, 3 July 1942, lot 49 (as ‘The Lake of Lucerne: Brunnen in the distance. Painted about 1840. 9 in. by 11 in. From the Collection of Mrs Pound, to whom this drawing was given by the Artist. From the Collection of A. Austin, Esq.’, bt. Agnew’s for £420); Thomas Agnew and Sons, London; L. B. Murray, in 1951, and by descent to his son; Private collection, in 1979; Sold by Agnew’s in June 1983 to D. Hoener, New York; Anonymous sale (‘Property of a New York Private Collector’), New York, Sotheby’s, 21 May 1987, lot 30; A. Alfred Taubman, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan; His (anonymous) sale, London, Sotheby’s, 11 April 1991, lot 77; Anonymous sale (‘The Property of a Gentleman’), London, Christie’s, 9 July 1996, lot 41; (Jacob) Eli Safra, Geneva; His anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 28 January 2016, lot 61.

LITERATURE: A. J. Finberg, Early English Water-Colour Drawings by the Great Masters [Special Number of The Studio], London, Paris and New York, 1919, pp.20 and 45, no.130, illustrated in colour pl.XX; Andrew Wilton, The Life and Work of J. M. W. Turner, Fribourg and London, 1979, pp.478-479, no.1488 (‘The Lowerzersee, with Schwytz and the Mythen’, where dated 1843(?); ‘News and Sales Record,’ Turner Studies: His Art & Epoch 1775-1851, Summer 1987 (Vol.7 No.1), p.64; Eric Shanes, ‘Picture Notes: 1. The Lauerzer See, with the Mythens (hitherto entitled ‘Lake Brienz’), W.1562...Victoria and Albert Museum. 2. The Lauerzer See with Schwytz and the Mythen, W.1488…Private Collection, U.S.A.)’, Turner Studies: His Art & Epoch 1775-1851, Winter 1987, pp.58-59; ‘News and Sales Record,’ Turner Studies: His Art & Epoch 1775-1851, Summer 1991, p.60; Robert Upstone, ‘Salerooms Report’, Turner Society News, August 1991, p.5; ‘An Evening for the Turner Society at Agnew’s’, Turner Society News, March 1994, p.1; Ian Warrell, Through Switzerland with Turner: Ruskin’s First Selection from the Turner Bequest, exhibition catalogue, London, 1995, p.71, under no.32, p.152, no.8; Terence Rodrigues, ed., Christie’s Review of the Year 1996, London, 1996, p.49; ‘Salerooms Report’, Turner Society News, August 1997, p.11; Eric Shanes, Turner: The Great Watercolours, exhibition catalogue, London, 2000-2001, p.238, under no.110; Eric Shanes, The Golden Age of Watercolours: The Hickman Bacon Collection, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich and New Haven, 2001-2002, p.49, under no.27; Eric Shanes, La Vie et les chefs d’oeuvre de J.M.W. Turner, New York, 2008, p.239; J. R. Piggott, ‘Salerooms Report’, Turner Society News, Spring 2016, p.16; Martin Krause, ‘Mrs. Booth’s Turners’, The British Art Journal, 2021, No.1, pp.6 and 8, illustrated p.9, fig.4; Jan Piggott, ‘Salerooms Report’, Turner Society News, Autumn 2023, p.30.

EXHIBITED: London, Thos. Agnew and Sons, Exhibition of Selected Water-Colour Drawings, 1910, no.184 (as ‘On the Rhine’); London, Thos. Agnew and Sons, Exhibition of Water-Colour Drawings by Joseph Mallord William Turner R.A., 1913, no.117 (as ‘View on the Rhine. View of a bend in the river with castle on the left, and on either side snow-clad peaks; moon rising. 8 3/4 x 11 1/4.’); London, Thos. Agnew and Sons, Exhibition of Water Colour Drawings by Artists of the Early English School, 1919, no.130 (as ‘Lake of Lucerne: Brunnen in the distance.’); London, Thos. Agnew and Sons, Centenary Loan Exhibition of WaterColour Drawings by J. M. W. Turner, R.A., 1951, no.96 (‘The Lowerzer See, with Schwyz and the Myttenberg. c.1840. Formerly known as “The Lake of Lucerne, Brunnen in the distance.”’); London, Thos. Agnew and

Sons, Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Watercolours by J. M. W. Turner, R.A., 1967, no.80 (‘The Lowerzer See with Schwyz and the Myttenberg in the Distance’); Zurich, Kunsthaus Zurich, Turner und die Schweiz, 1976-1977, no.43 (‘Lauerzer See, um 1841’); London, Agnew’s, Turner Watercolours: Watercolours by J. M. W. Turner R.A. (1775-1851), 1994, no.8 (‘The Lauerzersee with Schwyz and the Mythen’).

J. M. W. Turner made a total of six visits to Switzerland; the first time in 1802, at the age of twentyseven, when he spent some three months in the Alps. He did not, however, return to the country for another thirty-four years, until 1836, when he travelled there with his friend and patron H. A. J. Munro of Novar, although this trip did not result in any finished watercolours. Most significantly, Turner travelled extensively throughout Switzerland towards the end of his life, returning there every year between 1841 and 1844. Each of these trips resulted in numerous drawings, watercolours and sketches of Swiss and Alpine subjects, as well as a handful of large, finished oil paintings. As John Russell has noted of Turner, ‘Already on his first Swiss tour in 1802 he marked down as if by instinct precisely the places which would concern him most deeply forty or more years later…they were predominantly scenes which had an unruffled lake – Lucerne, Zurich, Thun, Constance – as their point of departure. Drama they had in abundance, those late Swiss watercolours; but it was as much the drama of Turner’s own creativity as of the scenes under discussion…the late Swiss watercolours have a quality which is to be found nowhere else in Turner’s work.’1 As Russell has also written, There was nothing that Turner did not know about European landscape; but it was to Switzerland above all that he turned when he had one more great thing to say and very little time left in which to say it. And he said it in terms of the pacific inundations – the swift flooding of the paper with water and colour – of which he was the supreme master. 2

The watercolours of Swiss views that Turner produced during his final tours of the country in the first half of the 1840s, of which the present sheet is an especially fine example, have long been recognized as among his most remarkable works on paper. They were unlike any watercolours he had done before, and he chose to have them marketed in a different way as well. In 1842 Turner left fifteen ‘sample’ watercolour studies, taken from the ‘roll’ sketchbooks of his Swiss tour the previous year, with his dealer and agent Thomas Griffith. These studies he proposed to make into more finished watercolours on commission, and Griffith was tasked with finding purchasers for them. The same arrangement with Griffith was also undertaken after Turner’s Swiss tours of 1843 and 1844, although in the end most of the finished watercolours were acquired by just two collectors, Munro of Novar and John Ruskin. As the latter wrote of Turner’s late Swiss tours, ‘He made a large number of coloured sketches on this [first] journey, and realised several of them on his return…The perfect repose of his youth had returned to his mind, while the faculties of imagination and execution appeared in renewed strength; all conventionality being done away with by the force of the impression which he had received from the Alps, after his long separation from them. The drawings are marked by a peculiar largeness and simplicity of thought: most of them by deep serenity, passing into melancholy; all by a richness of colour, such as he had never before conceived. They, and the works done in the following years, bear the same relation to those of the rest of his life that the colours of the sunset do to those of the day; and will ever be recognized, in a few years more, as the noblest landscapes ever yet conceived by human intellect.’3

The scholar Andrew Wilton has written that ‘Turner’s fascination with the landscape of Switzerland in the last decade of his career manifested itself almost exclusively in watercolours: studies briefly noted on the spot and worked up in colour afterwards were transformed, under the stimulus of consciously sought commissions, into a sequence of transcendental visions of mountains and lakes defined by the sweeping, swirling spaces between them…He produced hundreds of colour studies on these Swiss journeys, and was bursting with new responses to the lakes and mountains which needed to find expression in the ‘changed’ and ‘hazy’ manner he had newly evolved. But it was hardly in his nature to make finished watercolours without a clear economic purpose like engraving or sale to a collector…He was no doubt conscious that they represented, hazy or not, the culmination of his achievement in the medium…Turner knew these drawings to be his masterpieces.’4 Not long after the artist’s death, his late Swiss watercolours began to be highly prized by collectors, and this has continued to the present day.

In exceptional condition, this luminous watercolour depicts the Lauerzersee, or Lake Lauerz. Situated near the town of Schwyz, the Lauerzersee lies twenty-two kilometres east of the city of Lucerne and not

far from the town of Brunnen on Lake Lucerne. Turner had first visited the area on his initial Swiss journey of 1802, and returned there on sketching tours between 1841 and 1844, although it was in 1843 that he explored the Lauerzersee and its surroundings most extensively, from a base at Lucerne. In the summer of that year the sixty-eight-year old artist travelled along the northern edge of mountain massif of the Rigi, visiting the villages of Kussnacht, Arth, Goldau, Lauerz and Schwyz before ending at Brunnen.

On these excursions he carried with him one of his ‘roll sketchbooks’ of Whatman paper, with which he set down scenes that would be the basis of later, more finished watercolours. These ‘roll’ sketchbooks with soft paper covers, which could be rolled up and carried in a coat pocket, were used by Turner for more comprehensive studies in colour than the rapid pencil sketches which filled his smaller pocket sketchbooks. As Ruskin stated, ‘Turner used to walk about a town with a roll of thin paper in his pocket, and make a few scratches upon a sheet or two of it, which were so much shorthand indication of all he wished to remember. When he got to his inn in the evening, he completed the pencilling rapidly, and added as much colour as was needed to record his plan of the picture.’5

The present sheet comes from one of the ‘roll’ sketchbooks that Turner used on his Swiss tours. While the precise location depicted here remained a mystery for early scholars and collectors6, it has since been firmly identified as the Lauerzersee. Turner appears to have drawn this atmospheric watercolour from the road along the southern edge of the small lake, about a kilometre or so east of the village of Lauerz. At the left of the composition is the small island of Schwanau with its ruined castle, the Burgruine Schwanau, and at the right are the lower slopes of the Urmiberg mountain, while in the distance rise the distinctive twin peaks of the mountains known as the Grosser and Kleiner Mythen. Drawn in a fine pencil at the far end of the lake is what is probably the prominent 16th century church tower of the Alte Kapelle church in the lakeside village of Seewen, close to Schwyz. The artist may have been inspired to visit Schwyz and the Lauerzersee by the extensive description of the area given in John Murray’s guidebook A Hand-Book for Travellers in Switzerland and the Alps of Savoy and Piedmont, published in 1838, which he took with him on his travels.

As Ian Warrell has noted of this watercolour of The Lauerzersee with the Ruins of Schwanau and the Mythens, ‘Having defined the structure of the scene so deftly in his under-drawing, Turner added washes of diluted yellow and blue, leaving traces of hasty movements with his brush; or blending them at times to add green, a colour that is surprisingly rare in his works. These overlapping tones are given more tangible substance through the addition of economic penwork, at times as neat as lines of knitting, and elsewhere more freely calligraphic.’7 Warrell has likened the present sheet, in both stylistic and tonal terms, to a number of other watercolours of c.1842-1843 from the same or a similar roll sketchbook. These include three other ‘sample studies’, all of identical size to the present sheet, in the Turner Bequest at the Tate in London; Arth, on the Lake of Zug, Early Morning8 , Küssnacht, Lake of Lucerne9, and The Pass of St. Gotthard, near Faido10, as well as The Pass of St. Gotthard in the collection of the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island11. Particularly close to this watercolour in tonality and handling is a view of Schwyz, with the Mythens, in the Vaughan Bequest at the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh12. Several of these watercolours, including the present sheet, were later developed into more finished works on paper.

It has been suggested that the present sheet may have been part of a group of fifteen watercolour sketches – done as ‘sample studies’ with a view to obtaining commissions for finished watercolours –seen by Ruskin on the 10th of May 1844 and noted in his diary that day13. Two of this group of slightly larger, finished Swiss watercolours are today in the Turner Bequest at the Tate in London and four more are in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, while single sheets are in the Courtauld Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This watercolour of The Lauerzersee with the Ruins of Schwanau and the Mythens was not, however, used by the artist until several years later, when it served as the basis for one of his final ten finished watercolours of Swiss views, The Lauerzersee with the Mythens of c.1848 (fig.1), which was acquired by Turner’s patron Henry Vaughan and is today in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London14. The finished watercolour, however, lacks the lightness of the present study, and is somewhat darker in tonality.

The provenance of this superb watercolour can be traced back to Turner himself, since it was given by the artist to his housekeeper and devoted companion Sophia Caroline Booth (1799-1878). Of German descent, Sophia was born in Dover and at the age of twenty married a local fisherman named Henry Pound, who died in 1821, leaving her with an infant son, Daniel Pound. Four years later she married John Booth of Margate, and established a boarding house on the seafront there, where Turner would stay on his visits to Margate. After Mrs. Booth was widowed for a second time in 1833, Turner formed a close relationship with her. In 1846 Sophia Booth and her son Daniel moved from Margate to London, where Turner had bought a house for them in Chelsea, overlooking the Thames. She continued to look after the painter, cleaning his brushes and preparing his palettes, until his death in 1851. Turner presented her with several watercolours, including the present sheet, as well as at least eight oil paintings. This watercolour of The Lauerzersee with the Ruins of Schwanau and the Mythens first appeared at auction in 1909 and was purchased by Agnew’s. It was acquired from them by the English polo player and cotton broker Walter Henry Jones (1866-1932), a wealthy collector of Turner’s watercolours who came to own some twenty works by the artist, notably including both The Blue Rigi and The Red Rigi