ART H A B E N S

United Kingdom

I have been working with found objects throughout my artistic career, more recently with found plastic objects and fragments.

I love the versatility, the intensity of colour, industrial neutrality, and most of all, the way they record their histories over time and space.

Sources of materials include beaches, the countryside, cities, any place where discarded plastic objects are dumped or reappear.

Japan / Serbia

I am interested in the concepts of ‘atmosphere’ and ‘ Ma ’, a Japanese word which takes the concept of negative space farther, to define a continuum which spans both space and time. For example ‘ the space -in between ’ or ‘ pause in time’ might at first appear that there is nothing between the structures, but actually there is ‘ Ma ’, emptiness, blank space or time exist. And the space and the time have a very slight difference.

For the past 50 years Cuba’s future has been embedded in global systems that have the ability to connect and disconnect them in surprising and complicated ways, which has effected the day to day lives of those inhabited there. My main intention during this project was to document and bear witness to particularly interesting aspects of Cuban lifestyle, industry and culture through a series of reportage driven, visual essays. My journey began in the

Yunhsin Hsu’s artistic practice explores the relationship between man and nature by challenging preconceptions about natural beauty and forcing us to look again. With the development of history and culture, humans gradually take abnormal things for granted and ignore the original truth of them. Through painted illusions, layered meanings are brought to familiar objects to provoke thought and conversation, whilst disrupting existing symbolism.

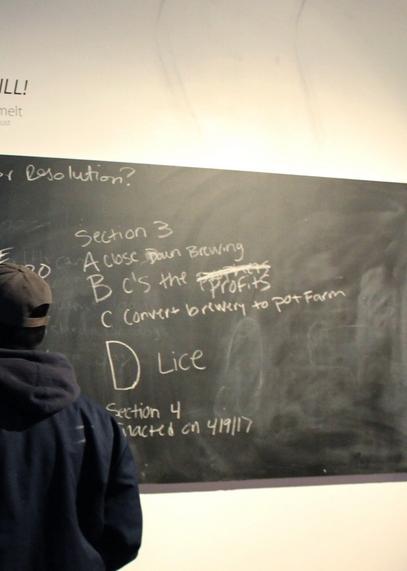

Morgan Hamilton is a Floridian-New Mexican artist currently working in Delaware, USA. He is a son of retired Navy Cryptologists and his childhood was spent moving all over the world, this lead to his love of culture and advocacy for tolerance. His work ranges from performance and video to sculpture and installation, exhibiting abroad and at home, from sea to shining sea. He is a transmedia artist and creates future realms whose bedrock is in our present experience.

Born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan and currently living and working in Toronto, Canada, Mariam Magsi is a Multidisciplinary Artist working in Photography, Performance, Video, Installation and other arts.

Burqatecture was realized during my MFA at OCAD University and the first exhibition of it was at my thesis show in 2017. It was experienced by quite a few people during the exhibition dates and the response was overwhelmingly positive.

I was made redundant after working 16.5 years for the University of Glasgow. I worked as a technician in the field of behavioural ecology and evolutionary biology; this encompassed the study of organic diversity, including its origins, dynamics, maintenance and consequences. Throughout my career I have used the above subjects in my art practice, blurring boundaries between associations of ecology, power and speciation.

Utilising my body as a tool of expression, my work aims to communicate themes such as vulnerability, visibility and fragility as well as focusing on sub-themes of repetition and the absurd, making links between the ritualistic nature of illnesses such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and repetition as part of performance art. This kind of performance work provides an essential look at the complex nature of human interaction, and shines a light on social issues.

is a London based artist intrigued by themes of metamorphosis and transformation.

As well as capturing an aspect of the sitters personality he paints a 'dynamic’ picture with vivid brushstrokes and colour.

Completely self taught, Paul has created a diverse portfolio including abstract landscape oil paintings, portraits in oil, digital art created with a digital pen and tablet and intricate drawings.

174

Born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan, lives and works in Toronto, Canada

An interview by , curator and curator

An interview by , curator and curator

Hello Mariam and welcome to ART Habens. Before starting to elaborate about your artistic production we would start this interview with a couple of questions about your background. You have a solid formal training and you hold a BFA (hons) in Studio Art & English Literature from the University of Toronto and after having earned your Digital Photography Diploma from the George Brown College, you nurtured your education with an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art, Media & Design, that you received from OCAD University in Toronto, where you are currently based: how did those formative years influence your evolution as an artist? In particular, how does your cultural substratum direct the trajectory of your current artistic research?

Mariam Magsi: Firstly, I would like to thank you for this opportunity to connect my work with wider audiences outside of North America. I was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan. I am currently living and working in Toronto, Canada. I am a dual citizen of both countries and I have had the privilege of attending excellent educational establishments in both countries, though my exposure to the arts has been incredibly different and varied in the two countries I consider home. In Pakistan I was in a British educational system within which the arts entailed extensive drawing and painting inspired by Realism. It was very competitive and all about grades, which defeats the purpose when it comes to creative expression. My formal education was in painting and drawing but I had more freedom to explore my subjects of interest in Toronto, Canada at the University of Toronto, Scarborough, where I was introduced to the worlds of Performance Art, Installation Art, Digital Photography, Live Art and other more non-traditional and experimental methods of

making, viewing and interpreting contemporary art. Later, at OCAD University as I did a two year MFA program (I graduated in 2017) I was introduced to intense theory and relearnt everything I thought I knew about art. It is at OCAD where my practice began to identify with visual languages and styles, carving space for itself within our globalized art scene.

Armed with a better understanding of how art can be used as a tool for story telling, as a tool for social change and justice, as a tool to shift societal perspective, I was able to carry over all this new knowledge and information into my

Mariam Magsipractice upon entering the professional art world after my MFA.

You are an eclectic artist and your versatile practice embraces photography, performance art, poetry and documentary, to pursue such multilayered visual results: before starting to elaborate about your artistic production, we would invite to our readers to visit https://www.mariammagsi.com in order to get a synoptic idea about your artistic production: would you tell us what does address you to such captivating multidisciplinary approach? How do you select an artistic discipline in order to explore a particular aspect of your artistic inquiry?

Mariam Magsi: I feel incredibly privileged to be able to visit my home country often. In a way I am sometimes living between two societies and thus am able to observe and record differences, parallels, diversities and nuances. A lot of this engagement with the world and our people, our histories, our narratives and our heritage, has begun to show up in my work whether through clothing, food, landscape or sound. My practice is as diverse as my dynamic identity. People often ask me “Where are you from?” The age old, immigrant question, at once curious and friendly, but also rude and Othering. “Where are you from?” they ask, and I can’t help but swallow up the 100 beautiful ancestors inside my big spirit and say “Pakistan.” Truly, my mother is Punjabi and my father is Baloch. My mother’s heritage goes back to pre-partition India and dates back to Syria. My father’s ancestors came into Pakistan through Iran. Both sides have such rich histories and diverse sets of languages, food, clothing and cultural practices. Within my family home unit, I was raised by Indigenous Baloch women, Filipino women, workers from Bangladesh, Afghanistan and the North of Pakistan. You could be eating sausages and eggs for breakfast, chicken adobo and pansit for lunch and Kabuli pulao for dinner. We

celebrate Christmas, Eid and Diwali and every December 25th a tree is decorated and lit up in the living room. I know that this is not everyone’s experience and I am grateful time and again for this exposure to people, cultures, religions and diversity, because it is this very exposure that today can be seen in my work, which aims to help us reflect upon our humanity.

Much of this diversity has been recorded with multiple recording devices, predominantly by my mother who would photograph and videotape everything. Similar to my diverse lived experiences, the methods that I employ, and the mediums I use are also quite diverse. I employ the use of visual mapping, so for me, it always starts with a photograph, whether captured through my phone, camera or any other recording device. That is the usual start to the subject I want to investigate and unravel. Once I have collected sufficient data in the form of visual records and documentation, I am able to make connections and visit the topic with a bigger picture in mind, widening the vocabulary of the process. The contemporary art world is so much more globalized and what we consider art also keeps shifting, so I do not limit myself to certain mediums, though my primaries are always lens based mediums that I like to build upon with performance and/or installation. Some works are process based while others are more complete performances and installations.

For this special edition of ART Habens we have selected Burqatecture, an interesting immersive installation that our readers have already started to get to know in the introductory pages of this article and that can be viewed at https://vimeo.com/214439885. What has at once impressed us of this captivating artwork is the way it provides the viewers with such a multilayered visual experience, capable of challenging their perceptual parameters. Would you walk our readers through the genesis of Burqatecture?

Mariam Magsi: Burqatecture was realized during my MFA at OCAD University and the first exhibition of it was at my thesis show in 2017. It was experienced by quite a few people during the exhibition dates and the response was overwhelmingly positive. To give you a little bit of background, the installation is inspired by quite a few factors. First of all, if you visit Sufi shrines in Pakistan, you will often find barriers between the pilgrims and the rose petal covered graves of the Sufi saints. These barriers resemble the mesh that goes over the eyes on a traditional, Afghani burqa. I’ve often observed these barriers through the polar lenses of the sacred and the profane, the saint and the sinner, etc. Secondly, I was visiting desi restaurants in Ontario when I came into one that had separate, veiled, partitioned, cubic spaces for “families and single women.” While thinking about the social politics of these spaces and the function of the veil within them as an architectural element, Hanna Papaneck’s theory of the “portable seclusion” sprung forward whereby she references the social mobility some women enjoyed due to their veils. Essentially, that is how Burqatecture came to fruition. While examining the postcolonial gaze projected onto the veiled, Muslim women, often symbolic of the ultimate Other, viewers enter a veiled space and are sandwiched between two sets of blinking eyes. One might ask, is the viewer veiled, or is the entity watching veiled? The installation problematizes the concept of Purdah or veiling. I also use sound and scent within the installation.

It's no doubt that collaborations as the one that you have established with Camal Pirbhai for Burqatecture are today ever growing forces in Contemporary Art and that the most exciting things happen when creative minds from different fields of practice meet and collaborate on a project: could you tell us something about this proficient synergy? Can

you explain how your work demonstrates communication between artists from different backgrounds?

Mariam Magsi: The way I see it, there are some artist with definitive styles and specific mediums that they have mastered. While others like Yayoi Kusama, Shahzia Sikander, Kara Walker, are always reinventing themselves with their multidisciplinary practices. Take a look at artists like Marina Abramovic who has worked in Performance Art, Musicals, Self Care and as we

saw recently, mainstream collaborations with rapper Jay-Z. Camal Pirbhai understands textiles and fabrics with an unmatched sensitivity so having him be a part of Burqatecture was wonderful to say the least. Pirbhai has prior experience intersecting digital media with textiles and was able to understand the convergence of the visual projections, the sound installation and the textile installation.

Camal Pirbhai: It's quite arrogant to not think of all of our work as some sort of collaboration.

Whether it is simply with a model, technical or studio assistants there are many hands involved in bringing a piece to life. When working with another artist on a project it is the differences in our two creative visions that makes for interesting work. Choosing to work with another artist is putting ego aside for the greater good of the work and understanding that the work will have a wider scope with the different angles we have on a particular themes. It is also important to be free with your own

thoughts and sensitivities because this is after all what gives the work it's soul, the combination of two minds if managed correctly makes for far more interesting work.

Your works grapple with the most prescient social issues of our unstable contemporary age, including sexuality, gender, Islam, migration, feminism. Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco once remarked that "artists's role differs depending on which part of the world they’re in. It depends on the political system they aree living

under": does your artistic research respond to a particular cultural moment? How do you consider the role of artists to tackle sensitive cultural and religious issues in order to trigger social change in our globalised contemporary age?

Mariam Magsi: You know, I often think about this. However, if you think about it, all of those issues you have brought up: sexuality, gender, Islam, migration, feminism, these are vital parts of human society and shape our existence and

evolution in multifaceted ways. So really, should we be asking if we are responding to current political issues, or are we responding to recurring, pendulum like issues in new, imaginative and evocative ways. If we are being given a platform, which issues and voices will we champion through our creativity and imagination? How can we trigger social change, a shift in human consciousness, a relearning of how people see and view our planet and each other, through contemporary

art? How can we use art to create more access for these issues, since far too often, these discourses are lost in the world of academia or “the white cube.”

Camal Pirbhai: Well, this is interesting and again the differences in Mariam and my understanding of our roles as artist and in tackle cultural issues brings in a more diverse audience to a piece. If two artists are saying the same thing one of them is useless. My thoughts on triggering social change through my work is to speak to those that oppose my views but in a delicate and subtle way. I find that beauty is a great disarmer and once someone is faced with something pleasing it is easier to make a point. This is my weaponry in dealing with the issues we face and want to talk about.

Marked out with a powerful narrative drive and rich of symbolically charged elements, your artistic production seems to aim urge the viewers to look inside of what appear to be seen, rather than its surface, providing the spectatorship with freedom to realize their own perception. How important is for you to invite the viewers to elaborate personal meaning? And how do you develop your storytelling in order to achieve such brilliant results?

I’ve traveled extensively and immersed in cultures upon invitation around the world. I’ve realized, while there are many commonalities and similarities amongst the diverse tribes of human species, no two people will view, interpret or perceive a work of art in the same way.

We are a product of multiple environmental, social, psychological, cultural factors, unavoidably impacted by class, race and gender. Rather than be attached to the outcome of how my work is being engaged with, I would rather focus on the shifts it is creating within

spectators and participants. Are viewers exiting my exhibitions, asking themselves a new set of questions with regards to the work and the symbolic message being conveyed? Are viewers compelled to dig deep into the various politicized topics I am examining in my work? Are viewers able to bring nuance, contradiction and variance into their perspectives, often only shaped by mainstream and social media? I often turn the gaze back onto the viewer to create tension and discomfort, perhaps to also reflect upon my personal journey as a diaspora artist, constantly on display, being viewed, categorized and tokenized.

We are the product of our environment, our upbringing, our education exposure, our cultures and societies and media. As artists, our job is to create the work, but directing how it will be seen is a whole other matter. I do believe that the author dies once the work is out there, and it continues to take a life of its own. While there are commonalities in ways of seeing, it is not possible for two people to see one work in the same way due to varying factors such as class, race, sexual orientation and identity. There will always be some difference.

Camal Pirbhai: The success of any work is to get the audience to put themselves in an other space to have them ask themselves questions. Physically we didn't give them much choice but I think we achieved more then that cause once you entered the space you were really transported. I think it was important to keep the image and sound as simple as possible to allow the audience to fill in the blanks. I feel strongly that you can't tell people what to think, not everyone has the same experience to draw from so leaving just the right amount of space for interpretation is key.

The combination between sound and visual plays a crucial aspect in Burqatecture and we have particularly appreciated the way its soundscape created provides the visual experience with such

Collaboration with Camal Pirbhai

an enigmatic and ethereal and a bit unsettling atmosphere: according to Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan there is a 'sense bias' that affects Western societies favoring visual logic, a shift that occurred with the advent of modern alphabet as the eye became more essential than ear: how do you consider the role of sound within your artistic research?

Mariam Magsi: Ever since I began to use Installation Art as a tool for creative communication, I have enjoyed pushing the

boundaries of how our five senses can be engaged and distracted within art gallery settings and the strict parameters within which contemporary artists have to work with. I employ the engagement of sound, touch, scent, sight and sometimes even taste in some of my performances and installations. Installation Art provides imaginative canvases that can be experimented upon beyond the realm of 2D paintings, photography or stationary 3D sculptures. A myriad of mediums and genres can come together to create spectacular and

evocative, immersive, interactive, participatory experiences that help viewers engage with material in new and embodied ways. I truly enjoyed inviting viewers into Burqatecture through scent. The space inside Burqatecture was incensed with Sandalwood on a daily basis in a ritualistic fashion, and the fabrics of the installation were scented with non-alcoholic, Ittar oils and essences. Once inside, participants could feel like they are inside a burqa or a body wearing a burqa. Amidst the heavy and heady scents, the participant is also immersed in

layered, audio echoes of whispers on loop on surround sound, enveloping the entire space and taking the participant in further into the work. Finally, two sets of eyes stare back at the participants, periodically blinking, creating yet another eerie and sinister feel to the created environment. The way all these elements intersect and are experienced through the fabrics is seamless, like good cinematography or photographic composition. This installation has pushed me to consider more works that are immersive, interactive and sensory in this

manner. We live in a world that is over saturated with imagery both online and offline. Works like Burqatecture require a level of sensory presence as well. These works cannot be justified or experienced through visual documentation, but rather require physical presence and full immersion. The work compels you to slow down once inside surrender to the environment created and think, process and experience, at a slower pace. However, it all depends on what is being communicated through the work and what method and medium works best to bring

that particular subject to light.

Camal Pirbhai: Well, the more senses you can effect with a work the more likely your message will be communicated. I don't agree with this idea of a 'senses bias' in-fact our brains need to do so much more computing with visual information that sound, if used properly can affect you more directly.

This was clearly our intent in this work. The fact that the audiences' sense of sight is greatly controlled with the black fabric surrounding

them and the small cutout forcing them to a single point of visual distraction only increases their other senses to be engaged.

You draw a lot from the experience of your early life in Pakistan, where you have had the chance to grow in a stimulating family that encouraged you to engage with art and instilled in you the passion for politics and history. However, as you remarked once, it was “impossible to escape gender roles and expectations.” How does such a wide variety of experiences fuel your creative process and help you to capture the kaleidoscopic quality of our ever changing societies? In particular, how do in your opinion Muslim artists are taking up space in order to fill the lack of diversity in the Eurocentric art canon?

Mariam Magsi: My family has been beyond supportive when it comes to my educational and career related goals. However, you have accurately recalled, that my experience of growing up in a patriarchal society like Pakistan has had an unavoidable impact on the topics I examine in my work, many of which have to do with dismantling global patriarchies. I’ve grown up knowing quite well that sons would have been preferred in my place, and that the hypocritical double standards impacting the lives of Pakistanis are alive and well to this day.

Gender inequality is a big issue and life is a fight irrespective of whether you’re privileged or not. Yes, financial security helps, but does not make Pakistani women exempt from oppression, misogyny and sexism. In a latest series of performative photographs, I tackle the ancient practice of Jahez/Dowry, by wearing inherited paraphernalia over my head and shoulders as resistance to societal roles preordained for women such as that of housewife, homemaker and eventually mother. These are positions I like to challenge in my work. In this series

particularly, I render the objects useless and subvert their original functions. While I am grateful for the support and encouragement I have received from home there were several gaps and holes that have been later filled with feminist scholars and artists that continue to shape the way I think about art, art making and my position as a contemporary diaspora artist. I enjoy using text in my work and I have often studied the resistance based, political works of Barbara Kruger that stand true and defiant even today. Tracey Emin is another artist I have admired for a long time for her honest and dynamic use of text to explore the female lived experience. Both artists employ the use of text but use it in such unique and compelling ways, it’s hard to forget their works or walk away from them unfazed.

People often say “our world is over saturated with imagery.” I contest this statement because our world has been oversaturated with Eurocentric imagery over a century, and this is changing with the advent of social media that provides more democratic exhibition spaces for those of us left out of the Eurocentric canon. Our voices are getting louder, our resistance is more and more unavoidable and we are asking the dominant hegemonic patriarchies some important questions that are shifting the status quo and ruffling the feathers of historic hierarchies that have been unmonitored and unquestioned.I am very excited to be a part of this shift.

You have received a very generous grant from the Toronto Arts Council in Toronto, Canada to further your research on veiling practices associated with Islam and how you can use art as a tool to examine this controversial and politicized topic. We have really appreciated the multifaceted nature of your artistic research and before leaving this stimulating conversation we would like to thank you for

chatting with us and for sharing your thoughts, Mariam. What projects are you currently working on, and what are some of the ideas that you hope to explore in the future?

Mariam Magsi: I am currently working on a diverse set of projects. The Textile Museum of Canada has invited me to make an artist collectible Surgi doll in partnership with Project Sunshine Canada. Surgi dolls are used for healing and therapy in hospitals, so I am very honoured to participate in this unique project. Keep a look out on my website and social media for further details on auction and exhibition dates at the Textile Museum of Canada.

This March, 2019, I am thrilled to participate in Salon 44 at the Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography in Toronto, Canada showcasing the best in Canadian, contemporary photography.

I have a few more exhibitions coming up in Canada and around the world in 2019, predominantly highlighting my photography, performance, video and installation work. I am also currently working on a film with co director, Eric Chengyang called “The Butterfly People” featuring stories about Canadians living with a rare, genetic skin condition called Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB). We have had some production delays but are hoping to complete this labour of love soon.

I would like to thank you for taking out the time to do this extensive interview. Opportunities like this further expose our works to diverse audiences and create even more exhibition opportunities so I am grateful and always happy to have creative, thoughtful back and forth.

An interview by , curator and curator

Burqatecture, 2017 Immersive Installation

Collaboration with Camal Pirbhai

Lives and works in London, United Kingdom

‘Insecurity' live interactive performance at the Silver B

‘The Gaze’ live performance at The Bargehouse gallery at OXO Tower wharf, 2017.

‘The Gaze’ live performance at The Bargehouse gallery at OXO Tower wharf, 2017.

Hello Laura and welcome to ART Habens. Before starting to elaborate about your artistic production we would start this interview with a couple of questions about your background. You have a solid formal training: after having earned your BA (hons) in Fine Art, you nurtured your education with a master’s degree in Fine Art, that you received from the University for the Creative Arts, in Farnham: how did those years influence your evolution as an artist? In particular, how does you cultural substratum direct the trajectory of your current artistic research?

Hello, and thank you for such a warm welcome! Yes that’s right, I studied both my BA (hons) and MA in Fine Art at UCA Farnham, and I think it’s apt that we start with a question about my education as it was my Master’s degree in particular that helped shaped my practice beyond anything else. Whilst I have had a creative inclination and a passion for the fine arts for years, it wasn’t until I began my Master’s degree in 2016 that I would really say I became an artist. Unfortunately during my Bachelor’s degree I was incredibly unwell, suffering acutely from various mental health problems, and although I learnt a lot about contemporary art and how to interpret it, I remained too unwell to really apply this knowledge to my own work. After graduating in 2014 I continued to battle with my mental health but, inspired by love of the abstract expressionist period, I began to paint to keep a visual record of my emotions. It was this plunge into art that had a profound effect on my mental state, hoisting me out of depression and allowing me to flourish in my personal and professional life. With my improved mental health, I knew that this was my chance to dive

back into education and hopefully establish a legitimate artistic direction.

I began the course as a painter, and despite only painting for just over a year, I felt a strong connection to the medium, one that I felt incredibly loyal too. The course began with a three week introductory project in which the

Laura Greenwaystaff encouraged students to investigate new ways of working, if only for the duration of the assignment. Eager to make the most of my time as a student again, I made the decision of exploring a new medium for these three weeks, and determined that in order to sufficiently challenge myself, I would explore an artistic area that fascinated yet adequately scared me –performance art. It didn’t take long for me to become enamoured with this broad and stimulating medium, and I quickly discovered that performing was something that not only did I really enjoy, but it felt like a more appropriate vehicle of communicating what I had to say.

Initially I was reluctant to let go of the medium I had become so entwined with, but as I learnt more about performance art and its history, I realised the vast potential that laid within its incredibly broad spectrum. The MA pushed me to reconsider what art could be, and after discovering a wealth of historical and contemporary practitioners that used their bodies to discuss different ideas, I began to question my own relationship with my body and how I could use this vessel as a tool of communication.

Through one to one tutorials with practicing artists I was able to openly discuss my ideas, and the lecturers encouraged me to push myself beyond my comfort zone to create pieces that not only made me uncomfortable, but that made my audience uncomfortable. I think for me that was when I realised the potential that performance art had in relation to provoking an emotional response from my audience and in addition to this, I started to consider the ways in which I could combine the mediums that I loved to create a multidisciplinary approach to performance art. I would say that the Master’s degree was the real birthing of me as an artist, and I owe my subsequent career to both the course and the tutors.

You are a versatile artist and your multidisciplinary practice encompasses performance, painting and video installation, to question the concepts surrounding mental illness, and we would like to invite our readers to visit https://www.lauragreenwayart.com in order to get a wide idea about your artistic production: when walking our readers through your usual setup and process, would you tell us what does address you to such captivating multidisciplinary approach? How do you select an artistic discipline in order to explore a particular aspect of your artistic inquiry?

I begin all my ideas with an experience – hand washing, showering, eating, meeting new people – all of these acts are ones that may seem simple to some, but for me have much deeper connotations. I select an action and then strip it back to the feeling that it produces for me, for example in my 2017 piece ‘The Gaze’ I began by focusing on the action of public hand washing, and then concentrating on the deep anxiety it makes me feel in relation to trying to get this task done quickly when in a public bathroom. I then consider how best to describe this feeling, after all, art is a form of communication and so I simply select the discipline that best depicts the experience. As you can tell from contemplating my practice, performance is the medium that I predominantly favor, however occasionally I find a different medium does an idea more justice. In 2018 I created an interactive installation entitled ‘Baggage’ in which I suspended over 80 luggage tags from the ceiling, all of which displayed a different intrusive thought on, creating a miniature environment of these menacing concerns. I then invited visitors to walk amongst the forest of thoughts, essentially employing their bodies as surrogate performers as they walked around the installation. This idea initially started as a performance using my own body, but as I

Audience members interact with ‘Under the Sheets’ live performance at the 2017 MA Degree Show at University for the Creative Arts, Farnham.

Audience members interact with ‘Under the Sheets’ live performance at the 2017 MA Degree Show at University for the Creative Arts, Farnham.

developed the idea I began to realise that in order to really immerse the viewer in a labyrinth of thoughts, it was necessary for myself to take a step back and allow the audience to directly interact with these thoughts in an installation setting.

For this special edition of ART Habens we have selected Under the Sheets, an interesting interactive performance that our readers can view at https://youtu.be/4pwRn6U3Y5I. Centered on the exploration of the fear of sexual intimacy and physical touch that you experience as part of your OCD, what has at once captured our attention of this extremely interesting work is the way it brings the themes of vulnerability and visibility of mental illness to a new level of significance, establishing direct relations with the spectatorship. When walking our readers through the genesis of this Under the Sheets, would you tell us how important was for you to create a personal performance, about something you knew a lot? And how does your everyday life's experience fuel your artistic research?

Being an artist that makes work about mental illness, my main source of inspiration is my everyday life. I have lived with mental illness, ranging in severity for over 15 years now, and living life with illnesses such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Depression and Anxiety put a real toll on you; everyday tasks can be so hard to accomplish, and things that most people take for granted, like physical contact, can be also be incredibly challenging. However, having my life consumed by these illnesses also meant that when it came to thinking about making artwork, it seemed like my everyday experiences were the natural influence for me to draw inspiration from, as they are essentially all I know. As mentioned in my previous answer, I often begin an idea with an experience from my everyday life and then I strip back these

encounters to the essential actions and concepts that surround them.

At the time of creation, Under the Sheets was the most vulnerable and intimate performance I had ever conceived – the piece came from the frustration that I felt in my personal life when it came to my fear of sex and intimacy. Having severe OCD, physical contact of any sort can be extremely challenging for me; simple interactions like meeting a new person and shaking hands can be fuelled with anxiety and apprehension and as you can imagine, intimate contact can be even more burdensome. Therefore, when designing the performance, I knew that it was crucial that I created a very personal and intimate experience for the audience, and after conducting research into the world of one to one performances, I decided that this was the best way to approach the subject.

Obviously an incredibly personal topic, the piece was always going to be personal, but when it came to choosing a discipline for this piece, I could have created a video piece or even a photography piece that addressed the same issues, yet allowed myself to be absent from the exhibit. Instead I decided such a personal piece would require my body to be present, creating a direct dialogue with the audience. I also knew in order for this piece to work it would demand that I put myself in a very uncomfortable situation, only then could I create a performance that was equally uncomfortable for my audience.

How do you consider the relationship between the necessity of scheduling the details of a shot and the need of spontaneity? How much importance does improvisation play in your practice?

Whilst every detail of my performances are conscious and premeditated, the fact that the majority of the works are live, of course makes

them subject to the element of spontaneity, particularly when they involve an interactive component. At first I found the ways in which live performance could stray from the preconceived idea to be slightly unsettling, but after drawing parallels to the uncertainty and unpredictability of life with a mental illness, I established a respect and enthusiasm for improvisation and spontaneity. I definitely embrace improvisation in my practice much more now, and the fact that I never rehearse a performance also adds to that aspect. Sometimes in live pieces I will now improvise portions of the performance, as I often find that in the moment you are able to read the room and consequently evaluate if more or less audience interaction is needed. In one of my latest live pieces entitled ‘Razor Standards’, in which I shaved and waxed my body hair in the public setting of South London Gallery, I quickly realised that my audience had become mostly stationary and so I decided to actually approach them and make eye contact whilst I continued to shave. The awkwardness of this interaction ultimately made for a more intense experience and, I feel, created a more successful piece.

When it comes to documentation of a piece, I believe the relationship between performer and photographer is important, and this is a topic that I researched whilst studying for my Master’s degree. I always try and have contact with my photographers before the performance so that I’m able to inform them of any particular shots that I’ve envisaged, and therefore a good working relationship between performer and documenter is key, however sometimes the nature of a performance means that unexpected shots will of course fabricate, and this is why a well trained photographer is key to snapping some great candid shots despite the spontaneity of the performances.

We have been highly fascinated with the way you include symbols and rituals in your artworks, as the boxes in The Gaze and the circles in Intrusion. In this sense, we daresay that you art practice also responds to German photographer Andreas Gursky when he underlined that Art should not be delivering a report on reality, but should be looking at what's behind: in particular, you seem to urge your spectatorship to challenge their cultural categories: how are important the symbols in your work and how important is for you to trigger the viewers' perceptual parameters in order to address them to elaborate personal associations?

As a conceptual artist, symbolism is a highly important aspect of my practice. As mentioned in pieces like ‘The Gaze’, each and every aspect has strong representative elements including the boxes, the timer and the presence of an audience and I would say that symbolism has become one of the most crucial aspects of my performance work. I so often use symbols in my work as a way of alluding to particular aspects of mental illness without being too literal. Of course some of my symbols are not that obvious due to their personal associations, and whilst I think its important that some kind of symbolism is interpreted from my work, I am open to the symbols used being interpreted differently than I intended. I find it interesting to see what certain associations different symbols can trigger in a viewer.

Rituals are another important element – I was initially drawn to performance art because of the strong use of rituals within the medium and I automatically drew links to the ritualistic nature of mental illness, with OCD in particular. Rituals are something that shape so many people’s lives, whether it be a cultural ritual or a simple daily routine, but rituals are an occurrence that most people can relate to. By

Audience members are invited to cover the artist’s skin in their insecurities.

Photo courtesy of The Silver Building and photographer Wiktoria Slowikowska.

Photo courtesy of The Silver Building and photographer Wiktoria Slowikowska.

using these two aspects, I hope that I am able to prompt both thought and reflection in my audience – I like art that makes people think.

Your artworks, and in particular I used to be beautiful, that can be viewed at https://youtu.be/XXaJU-zTiaE also weave such a subtle still effective socio political criticism, to question the unrealistic body standards of society today. Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco once stated, "artists's role differs depending on which part of the world they’re in. It depends on the political system they are living under": does your artistic research respond to a particular cultural moment? In particular, how do you consider the role of artists in our media driven and globalised contemporary age?

I find Gabriel Orozco’s work really compelling, and I definitely agree with this quote of his. Whilst political criticism has not previously been at the forefront of my work, you’re right in suggesting that there are most positively influences from today’s socio political environment in all of my works. I believe that it is actually incredibly hard to avoid touching on these subjects as our social environment has such influence on all parts of our lives, and therefore is visible in the work that we as contemporary artists produce.

My recent piece ‘I used to be beautiful’ is easily my most socially motivated piece so far as it responds directly to today’s image of beauty and the unrealistic standards that society has reinforced as essential, and after receiving such a positive audience response, I intend to explore this subject further. Through commenting on the way that the media expects bodies to look, particularly the female body, my work has also began to address feminist issues in relation to idealistic specifications, with the forefront of this influence being current commercial media. As a mental health awareness campaigner and disability rights activist, my work surrounding

mental illness often subtly comments on the way that people suffering with these conditions can be treated, and in turn helps to start a conversation about issues that are often sidelined. I also believe that my practice can be interpreted as addressing the wider issues of anxiety, the anxiety that people may have developed surrounding the country’s political issues and the apprehension that can arise for many people in these uncertain times.

I believe that as an artist who has a small following, and especially in regards to having an influence on social media, it is my job to create work that inspires conversation and discussion, as I can potentially help change people’s views around specific situations. As contemporary conceptual artists I think that we can take today’s media dominated and use it for our advantage, allowing ourselves to take stage and talk about the subjects that matter most to us.

Many artists express the ideas that they explore through representations of the body and by using their own bodies as a tool of communication, as you do in general in your practice, and in particular in your recent performance I used to be beautiful. German visual artist Gerhard Richter once underlined that "it is always only a matter of seeing: the physical act is unavoidable": as a multidisciplinary artist deeply involved in performance, how do you consider the relation between the abstract nature of the concepts that you explore in your artistic research and the physical aspect of your practice?

When contemplating the subject of mental illness, we are confronted by an incredibly abstract concept. Mental illness is not something we cannot see, and even to put our emotions into words can be a convoluted task. A Google search of the term ‘mental illness’ coupled with the word ‘art’ generates a multitude of images similar in nature – heads between hands and

screaming mouths are used all too often to depict the trauma that we experience in our minds, and it is hard to escape the physical when physicality is all we know. Using the body in my work, I aim to explore these concepts but in a less obvious way. Of course I still use a physical basis, but I prefer to challenge the stereotypical bodily associations.

I instead approach my topics with a broader interpretation of what the body can say about mental illness, how the body can be exhausted and pushed, just like the mind can be, and I try and create parallels between the abstruse nature of the mind and the physical attributes of the body.

As you have remarked in the ending lines of your artist's statement, you aim to create awareness of mental illness and, by creating a dialogue around the subject, she hopes to challenge the stigma surrounding conditions that are often wrongly treated as imaginary afflictions. How do you consider the therapeutical function of art making? And how could art raise awareness into a wider number of people about the theme of mental illness and on how it can affect people’s ability to engage with others?

For me, the impact that art has had on my mental health has been life changing – art has quite literally saved my life! Through out my BA degree I suffered greatly with my mental health, and when I was hospitalized after graduating I reconnected with art as a way of coping with my incredibly low mood and suicidal ideation. The way in which I could express myself through art, at first painting, and then progressing into performance and multidisciplinary work gave me an outlet that traditional talking therapies had never been able to provide, and the more I fell in love with art, the more I fell in love with life. I began to pour my emotions into creating work based around my experiences, and I even learnt

to deal with my panic attacks by focusing on how I could harness and utilise that feeling into a piece of work. As you can tell, I am a strong believer that art can, and does, act as a therapy for some, and I would strongly recommend trying something creative as an outlet for all kinds of trauma.

In terms of raising awareness, I believe that art is an advantageous and effective medium in which to reach people from all walks of life, especially when art becomes public and breaks away from traditional gallery settings. Working for a local pop up gallery I am often able to do

performances in the shopping center where we are based, and this allows me to reach people who are just out shopping and would not necessarily be expecting to see art or be approached about the subject of mental health.

Another beneficial facet of art is the accessibility of it – the topic of mental illness can be a hard conversation to initiate, but seeing it approached in a way that can be interpreted by the audience makes the conversation flow a little easier; I think this is why my art resonates with so many people.

Over the years you have performed in several occasions, including your recent participation to Mind@Silver at The Silver Building Gallery, and to (In)visible at Espacio Gallery, both in London. We have really appreciated the originality of your artistic research, and especially the way your artworks break the barrier with the audience, that in many performance, and more rencently in Baggage, is urged to evolve from the condition of mere spectatorship: how do you consider the nature of your relationship with your audience? And

what do you hope your audience take away from your artworks?

The artist’s relationship with their audience is something that has been at the forefront of my artistic research for some time. I have been incredibly interested in how artists, particularly performance artists, can forge a relationship with their audience through their work. One such artist that has closely inspired my interactive performances in particular is the late British performance artist Adrian Howells. Howell’s work employed the use of intimacy and pioneering one to one interaction with his audience members to create incredibly unique and personal performances that established meaningful emotional connections with strangers, something that inspired a lot of my participatory performances. One element of my performances is the use of audience as my medium, rather than just my own body, and I do this by creating performances that require the audience to be involved in the work, subsequently allowing them to become a performer, if just for a fleeting moment. I like to use my audience as part of the performance for a number of reasons, one being that it allows them to literally put themselves in a vulnerable position, temporarily emulating the unease felt by those with mental illness. Whilst I cannot guarantee to make my audience member transiently feel exactly what I feel, I do believe that engaging my audience in this way definitely helps to create an emotional response in them. I like to hope that they take something special away from the piece –perhaps more of an understanding of what it’s like to live life with a mental illness, or even just a new found awareness of illnesses that can often be so easily misunderstood.

We have really appreciated the multifaceted nature of your artistic research and before leaving this stimulating conversation we

would like to thank you for chatting with us and for sharing your thoughts, Laura. What projects are you currently working on, and what are some of the ideas that you hope to explore in the future?

Thank you so much, it’s been great talking to you and sharing my practice with you and your readers!

Coming into 2019 I gave myself a number of artistic goals, and one of these intentions was to make more work about my physical disabilities as well as my mental illnesses. In turn I am aiming to create more work that explores the social issue of living life with disabilities, including the anxiety disabled people around the country face when it comes to their own financial stability and the barriers that disabled and mentally ill people can face in their everyday lifes due to this lack of support. As mentioned earlier, I will be shifting my focus onto a more political lens when it comes to the way our contemporary government and society treat disability and mental illness, so expect to see some more politically motivated works in the future.

In addition to these concepts, I am currently working on a series of work designed to explore my relationship with my body as this is an area that, due to a binge eating disorder coupled with depression, I struggle with. These works were all inspired by my time at the Venice International Performance Art Week’s summer workshop programme, and I am planning to realise these ideas through a sequence of performances, video works and photographic pieces.

I also intend to continue challenging both my artistic and personal boundaries by creating performances that confront my fears and in turn establishing vulnerable and transparent pieces.

Close up of ‘The Gaze’

live performance at The Bargehouse gallery at OXO Tower wharf, 2017.

Close up of ‘The Gaze’

live performance at The Bargehouse gallery at OXO Tower wharf, 2017.

Lives and works in Glasgow

Straiph exhibiting “Hashish”

Medium Ceramic/Glaze as the Sin Eater at Asylum Artist Management

LONDON LAUNCH SHOW at The Crypt Gallery. (photography Tosh Marshal)

An interview by , curator and curator

An interview by , curator and curator

Hello Straiph and welcome to ART Habens. Before starting to elaborate on your artistic production, we would begin to this interview with a couple of questions about your background. As a primarily self-taught artist, are there any experiences that did particularly influence your creative process? In particular, how do you multifaceted cultural substratum due to the years you spent working as a technician in the field of behavioural ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Glasgow direct the trajectory of your current artistic research?

What I’ve noticed over time is that it’s not so much the experience itself that was important, but the meanings I now assign to the experience as an artist. I would, however, agree that these experiences that I was privy to observe in the context of systematic deconstruction towards reconstruction are a central unifying concept that has without a doubt been majorly influential in directing my trajectory as an artist. However, as an artist to create something only to deconstruct it and then rebuild it again seems to be a Sisyphean task to solve a Promethean problem.

I recently exhibited a series of ceramic head sculptures titled “Sin Eaters” at the Copenhagen Outsider Art Gallery. A sin-eater is a character from Scottish folklore who consumes a ritual meal and drink to magically take on the sins of a person or household. What was destroyed was

Wilsonbelieved to absorb the sins of a recently deceased person, thus absolving the soul of the person. The creative inspiration behind this recent work was generated by the scientific research work related to the concept of phenotypic plasticity that I had observed in my technician role. The experiments tested the ecological theory of adaptive radiation that predicts that the evolution of phenotypic diversity within species is generated by divergent natural selection arising from different environments and competition between species.

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a progression in which organisms diversify

Straiphrapidly into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, creates new challenges and opens environmental niches. Starting with a recent single ancestor, this process results in the speciation and phenotypic adaptation of an array of species exhibiting different morphological and physiological traits with which they can exploit a range of different environments. Metaphorically this series of sculptural heads are in essence a reflection of human phenotypic plasticity. The SinEaters are my attempt to create a personal journey of exploration into the relationship between the structure and function of morphological features, akin to the scientific research process of deconstructing and reconstructing hypotheses. Similar to the operation of natural selection in the universe I want to push the boundaries of the human morphology through these sculptures. I was conscious that as a technician I was always on the periphery of the scientific research and never had the ownership of the hypotheses or the results. In essence, I was the observer looking in or kind of a shadow in the academic process. Processing the science-inspired themes in my artwork has finally given me the opportunity to be the master of the experiment.

The body of works that we have selected for this special edition of ART Habens has at once captured our attention for the way it rejects any conventional classification and challenges the viewers' perceptual parameters, and we would like to invite our readers to visit https://www.artquid.com/gallery/straiph in order to get a comprehensive idea about

your artistic production: when walking our readers through your usual setup and process, we would like to ask you if you think that there is a central idea that connects all your works. In particular, could you explain the concept of Zones of inhibition?

Having had this extraordinary opportunity to have insight into both of the opposing worlds: science and art, allows me to combine in my practice elements from these two distinctive groups. Scientists are objective and rational, artists as subjective, intuitive and arbitrary. These polar opposite forces of creativity give origin to practices that are conventionally seen as mutually exclusive, creating so-called ‘Zones of inhibition’ that are typically inaccessible to the other group. My experience in both environments allows me to draw elements across the Zone of inhibition and combine scientific themes for example with elements of folklore. As an artist, I have the power to distort these boundaries. Unlike the scientists around me who are bound by reason, I do have the freedom to create my own reality rather than trying to study a preexisting one which has allowed me this incredible opportunity to advance my critical thinking and practice.

The zone of inhibition has not always existed between art and science. In the times of antiquity, the fundamental notion of exploring secret powers of the nature of knowledge (Epistemology) was a common culture shared between scientists, philosophers, and artists. At those times these groups were close interrelated via their shared interest in the essences of

things or the ‘inner structure of existence.' I am immensely interested how in our modern era the egos among the natural scientists have taken the trajectory of over dominating our world, emphasizing the power scientific experimentation at the expense of more philosophical or artistic attempts to conceptualise the world around us. The dominance of science brings a danger of feeling omnipotence and starting to “play God” in the sense that we confuse the knowledge we do have with the wisdom to decide how to use it. Perhaps the scientists are too often overlooking this wisdom and ignoring the connection between reality and imagination. For now, the zones of inhibition persist but I will continue working across them and wondering: Science versus Art, which will manifest as triumphant or can they join forces again? As the saying goes “You can’t play God without being acquainted with the devil.”

How importance does spontaneity play in your process? In particular, do you conceive you works instinctively, or do you methodically elaborate your pieces?

The subject matter ultimately is the aesthetics of the finished work, is methodical, meticulously and painstakingly constructed. My creation process is an expression of the physical and mental undertaking which is built upon the freedom as mentioned earlier to recreate my reality rather than trying to study a pre-existing one which is an innate foundation of science. It is a reactive agitation to situations derived from instinct and experience, A visceral gut feeling relating to an in-depth inward course of action in spite of difficulty or opposition -

an emotional rather than intellectual response to the given stimulus. The physical making of each piece that I create lies in a fractal spontaneity, in suspense and in the uncertainty of circumstances that is governed by the alchemical interaction between clay, fire, and glaze. When I embark on a creative journey on a particular theme, I become fully immersed in it. For example, last year I was part of a group exhibition in London when the Sin Eater work series creation was at its infancy. To fully feel and understand the Sin Eater and to play the character complete, and explore how he interacts with the world, I decided to morph into Sin Eater, to evade all conscience of my own, like a blank canvas, an empty vessel. By dropping a personality into that space and letting it take over, filling that void. Very sociopathic! On the opening night of the exhibition which conveniently was held in a crypt. I wore a robe that I loaned from Scottish opera, a macabre silicon mask from America (hand-made for the occasion) and black pitiless contact lenses. The presence of the Sin Eater character had a dramatic impression on the audience and helped me to take the Sin Eater theme up to another level and understand the inner being of this character. For me, the artistic process is about either giving everything or nothing.

We like the way your sculptures seem to provide with a tactile nature the ideas that you explore. Michael Fried once remarked that 'materials do not represent, signify, or allude to anything.' What are the properties that you search for in the materials that you combine? In particular, what does appeal you of the materials you include in your artworks?

''The sixth Mass extinction' 'Fungi. Medium Ceramic/Glaze (Meliorist) (photography Jurate Veceraite)

Materials and methods, I'm continually toing and froing, experimenting with the pleasure of discovery and implication. Initially, I was using commercially available clays to help prevent deviation from standards, as they could to a certain degree provide me with a baseline of predictability and rationality within the construction phase. I then started experimenting more with the textures and I now purposefully distort this predictability, atonality, by introducing a local Scottish clay,

dug up from a local farmer’s field. Mixing commercial clays of Porcelain, Stoneware, alongside the local earthenware clay I’ve named “Aberfoyle” changes the properties of the material leading to volatile results from the outset. The Aberfoyle clay is highly porous, not very vitrified and unpredictable when the various clays are all jostling against each other during the firing process – I like to think it’s like alchemy. The differences in material properties make it inevitable that some of the individual pieces morph into an

unexpected direction. Each time when I wait to open the kiln, my imaginative speculation is akin to a twisted pious experience. Once again, I am an observer; this time an artist in the shadow, waiting to witness the chaotic results the differing expansion forces in my mixture of raw materials have imprinted on my creation. Seize the moment and live in the mystery and embrace the effects of alchemy!

We have appreciated the vibrancy of thoughtful nuances of your artworks, to

create tension and dynamics. How did you come about settling on your colour palette? Moreover, how much does your psychological make-up determine the nuances of tones that you decide to include in a specific artwork and in particular, how do you develop a texture?

My psychological nuances of colour run deep. The vibrancy of changing colours within a recent series of work called "Alchemist Garden" are purposely selected

''The sixth Mass extinction' 'Fungi. Medium Ceramic/Glaze (Sotheans) (photography Jurate Veceraite)

according to nature's ways of deception. In the natural kingdom many species, including fungi, have bright, conspicuous colours. It is called “Aposematism” and functions as a defense mechanism that relies on the memory of a would-be predator. Vibrant colours warn predators that the prey is toxic, distasteful or dangerous. I want to use this visual warning in my artwork to highlight their volatility and perhaps to initiate the conversation exploring risk-taking. The influence of the Scottish landscape is also ever-present in my work. It would seem unfortunate not to include those rustic and misty hues of Scottish moorlands considering I live and work within a remote part of Scotland with forests, mountains, and lochs close of my studio.

Rich of symbolism, your artworks are marked out with such a powerful emotional: as an artist particularly interested in the relationship between physical ritual, performance and power and creating religious objects from these ideas, how do you consider the role of symbols and their evocative qualities within your artistic research?

Psychiatrist Carl Jung once said about symbols that their purpose was to “give a meaning to the life of man." An honest challenge considering that traditionally science has no place for symbolism, whereas art is precious, capricious in symbolic representation. This cryptic means of communication has always fascinated me. In the ceramic fungi sculptures, that I produced in 2017 for the Cavin-Morris gallery in New York, I inscribed ancient magical sigils on the surface of each fungus. These cryptic

symbols are taken from the first book (Ars Goetia) in The Lesser Key of Solomon series, which is an anonymous grimoire focused on demonology. It was compiled in the midseventeenth century and is attributed to

magazine.

renaissance ceremonial talismanic magic emphasizing mysticism as an extension and amplification of traditional religious views. It attempts to go beyond or behind traditional and established dogma, to satisfy the need

which certain individuals have to experience the Divine directly. There are two principal subdivisions under which the Ars Goetia falls: the speculative and the practical. The speculative branch of the Ars Goetia deals

essentially with philosophical considerations, whereas the actual, sometimes also called magical, stress the mystical value of ancient archaic words and letters as well as their uses which allowed me the room to delve

into symbolism untrammelled which I believe, is once again a juxtaposition worth challenging and once done has potential for pointing us to a metaphoric truth, towards enlightenment.

We daresay that your artistic practice seems to aim to look inside what appears to be seen, rather than its surface, providing the spectatorship with the

freedom to realize their perception. How important is for you to invite the viewers to elaborate personal meaning?

The work I engage in can be a very internal process, seemingly without a sense of purpose. You pose the question of how important it is for me to invite the viewers to elaborate personal meaning. This presents a potential challenge as the need for understanding is on the viewer, and they can draw their conclusions and skewed perceptions. What I am actively engaged in is a complex matrix of personal involvement, influenced by an intimate experience spanning from two decades as a scientific observer: Me watching them watch their chosen species. These experiences morphed with an even longer influence of Celtic mysticism and folklore. To make that accessible to the viewer seems somewhat intimidating undertaking. In any case, I believe that there are no two people who would find the same message and nuance of influence from any given artwork. So, in that sense, the artistic impact is always at the heart of the spectator and not under my control. However, I hope I can provide something new and engage the viewers that will provoke them to walk along the path of reflection.

As an artist with a scientific background, how do you consider the relationship between artistic production and scientific research? Do you think that there could be a kind of synergy between such opposite disciplines?

Art is often introspective while science is retrospective. The scientists I worked for were extremely protective of their work and

Straiph Wilson as the Sin Eater & Laura Jeacock Norse goddess Hel. (Modelling for artist Karen Strang)

Straiph Wilson as the Sin Eater & Laura Jeacock Norse goddess Hel. (Modelling for artist Karen Strang)

generally had little interest in artistic themes. Therefore, I chose a more undercover position amongst the scientist and was continuously observing them for inspiration but never gave them any inclination that I was studying them, as this would have created a tension that would have made my position untenable. This way I gathered a wealth of information on the scientific process. As previously mentioned, the way science influenced my artistic practice, it is not so much the experience itself that was important, but the meanings I now assign to those experiences as an artist. I am always deriving inspirations from the desire to convey my own experiences and that way I stay true to my craft. My works typically contain multiple layers of meanings, allegories, and references to other equally symbolic cryptic works. If I can convey an honesty of exploration and authenticity, then I will feel that I am heading in the right direction with my practice. I would concur that both disciplines, art, and science, are human attempts in comprehending and defining the world around us to deepen the individual expressions of reality. I'm curious and trying to find synergies in the different disciplines. I think there is scope bringing these disciplines closer together in the modern world and working to evaporate the schism slowly.

The power of visual arts in the contemporary age is enormous: at the same time, the role of the viewer’s disposition and attitude is equally important. Both our minds and our bodies need to actively participate in the experience of contemplating a piece of art: it demands your total attention and a particular kind of

effort—it's almost a commitment. So before leaving this conversation, we would like to pose a question about the nature of the relationship of your art with your audience. What do you think about the role of the viewer? Are you particularly interested if you try to achieve to trigger the viewers' perception as a starting point to urge them to elaborate on personal interpretations?

Naturally, I appreciate if my art has an impact on an audience, but primarily my work is driven by my inspiration to create rather than the desire to please an audience. If it opens up the potential to elaborate intimate interpretations in the mind of the viewer that is of course satisfying. Last year I was present in person at three opening nights of exhibitions that were highlighting my practice. At all three of the exhibits, the questions that asked of my practice were multifaceted, far-reaching and sincere. For example, someone asked if the pieces had a magical influence of concern. My answers were "Of course as it is the live piece of artwork." By any measure, outsider art is now an established category, and I felt that curious authenticity at these events. I feel privileged that I have a foundation to place my story upon as the people I met and who wanted to engage in conversation with me, were very switched on, meticulous, exceptionally intellectual and open to interpretations on many levels. My foundation has been a clincher on many occasions, resulting in that individual purchasing my work and additionally establishing contact to know more about my practice.

Straiph exhibiting “Hashish” Medium Ceramic/Glaze as the Sin Eater at Asylum Artist Management

LONDON LAUNCH SHOW at The Crypt Gallery. (photography Tosh Marshal)

Over the years your artworks have been showcased in many occasions: how do you consider the nature of your relationship with your audience? Also, what do you hope your audience takes away from your artworks?

Out of the three exhibitions last year, two included a live performance as the "Sin Eater." They were face-to-face, at proximity, with the audience without them having prior knowledge that such a character would be encountered at the opening night. An uncomfortable, distorted situation by all accounts to many of the audience members. That visceral gut feeling of anxiety and curiosity was palatable. Having my eyes blacked out with contact lenses, thus not allowing the audience to follow my gaze, caused an obvious aversion, an uneasiness that a behavioural ecologist with interest in psychology would find fascinating. This gives an interesting perspective to reflect if "Species that don't figure out ways of dealing with threats will go extinct." Despite putting the audience on the spot and making them deal with an unnerving, devilish character these performances were also well received by the galleries and appreciated by the viewers as an experience that was pushing the boundaries presenting ceramic sculptures in an entirely new context.

We have appreciated the multifaceted nature of your artistic research, and before leaving this stimulating conversation, we would like to thank you for chatting with us and for sharing your thoughts, Straiph. What projects are you currently working on, and what are some of the ideas that you hope to explore in the future?

I have recently made a short film for the Raw Vision Magazine further exploring the Sin Eater character. The video includes emotional visual manipulation which morphs the sin eater character into an optical vortex of anguish represented by revolving and eternally multiplying images of the character. In its theme, it is complete chaos but, in its presentation, forming perfectly symmetrical patterns – again joining to opposites.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQz7xw AODQ8

To complete the full 360 degrees, the view around the scientist versus artist development continuum, in the next phase I will complete observing an artist at work from the sin eater character’s perspective. Scottish artist Karen Strang will paint a portrait of me as the Sin Eater. This will also allow me to explore the nature through another artist’s eyes, and let’s see if what reaches another layer of depth, reveals something new about the Sin Eater character and what kind of ideas this experience inspires.

I am also working to create yet texturally richer head sculptures, really pushing the boundaries of morphology.

An interview by , curator and curator

Straiph exhibiting “Hashish” Medium Ceramic/Glaze as the Sin Eater at Asylum Artist Management

LONDON LAUNCH SHOW at The Crypt Gallery. (photography Tosh Marshal)

Hello Morgan and welcome to ART Habens. Before starting to elaborate about your artistic production we would start this interview with a couple of questions about your background. You have a solid formal training: you hold a BFA in Studio Art and after having earned your MFA in Studio Art from the University of Delaware, yu nurtured your education with a PhD in Museum Education and VisitorCentered Curation, that you are currently pursuing at the Florida State University: how do these formative years influence your evolution as an artist? In particular, how does your cultural substratum direct the trajectory of your current artistic research?

I grew up as a Navy brat, that is, a child of two Navy Cryptologists. I spent my childhood moving between Florida, California, New Mexico, and Okinawa, Japan. My many homes broadened my horizons and exposed me to myriad cultures that not only educated me about the human experience made me appreciate my own. I resolutely believe that travel, exposure, exploring, getting lost, navigating, and adapting sewed the seeds of my creative being.

Like so, so many artists, especially here in the States, I was discouraged from pursuing a “useless” art degree after high school. Fine arts is stigmatized as a an elitist degree that has no job waiting for its graduate after college. It is second-class to Science, Technology, Math, and Engineering (STEM) fields, and pales in comparison to post-graduate STEM job prospects. These myths are specious assumptions based on American ideology that has been traumatized by the financial crisis and subsequent recession.

My mother convinced me to go to school for art after I floundered in several other majors like English, Business, and Education. When my compass was calibrated to my passion, I quickly entered my BFA at Florida State University and made a resolute pact to be an artist. I joined every student-run arts organization to stay involved and in-the-know, and those opened doors beyond my curricular studies, they also gave me my first taste for arts administration,

Morgan Joseph Hamiltonwhich would inform my career as a curator and PhD student.

I was accepted the MFA program at the University of Delaware where I departed from my traditional, formal techniques like oil painting and moved into a self-led journey into installation, costuming, video, and eventually narrative storytelling. I found a passion for storytelling beyond stand-alone installations or video art, I discovered transmedia theory and how using all forms of media (publication, internet, newspaper, email, video, characters, etc.) blurs the lines between reality and virtual reality, something that our currently connected world is coming to terms with. I want to locate the border between real and fake; I’m discovering that the border is much closer than we think.

I took my interests from my program with me while curating at The Delaware Contemporary and used my privilege to promote women artists, local African American artists, and video, internet, and experimental artist. While working as a curator I learned how to be a better exhibiting artist, an important skill that will help me get exposure from galleries and especially successful art reviews like ART Habens.

You are a versatile artist and your practice includes sculpture, installation, performance and video: before starting to elaborate about your artistic production, we would invite to our readers to visit http://www.morganjosephhamilton.com in order to get a synoptic idea about your artistic production: would you tell us what does address you to such captivating multidisciplinary approach? How do you select an artistic discipline in order to explore a particular aspect of your artistic inquiry?

While in school the emphasis is medium first: what is your medium? What do you make with that medium? It took me a while to discover my own process, and break from that formal approach. Since, I have discovered that I address an idea or story and it informs my medium. I

believe that’s why a viewer will find I use anything from traditional oil on panel to fake websites for a fake product.

To illustrate what I am saying, I will use my overarching project Welcome to Nastroism as

an example. Over a long, cold, dark winter I began to read a book called Leaving Orbit (2015) by Margaret Lazarus Dean and absolutely hated it. It was infuriating (you can read my 2 star review on its Amazon product page). It was a book all about how the Apollo