Geor G e Haynes

In Search of Painting

9 Preface: In Search of Painting

From

Andre

15

Chelsea to Perth Sally Quin 39 Out of Africa John McDonald 68 Selected Works 188 Curriculum Vitae 190 List of Works 196 Acknowledgements

Lipscombe

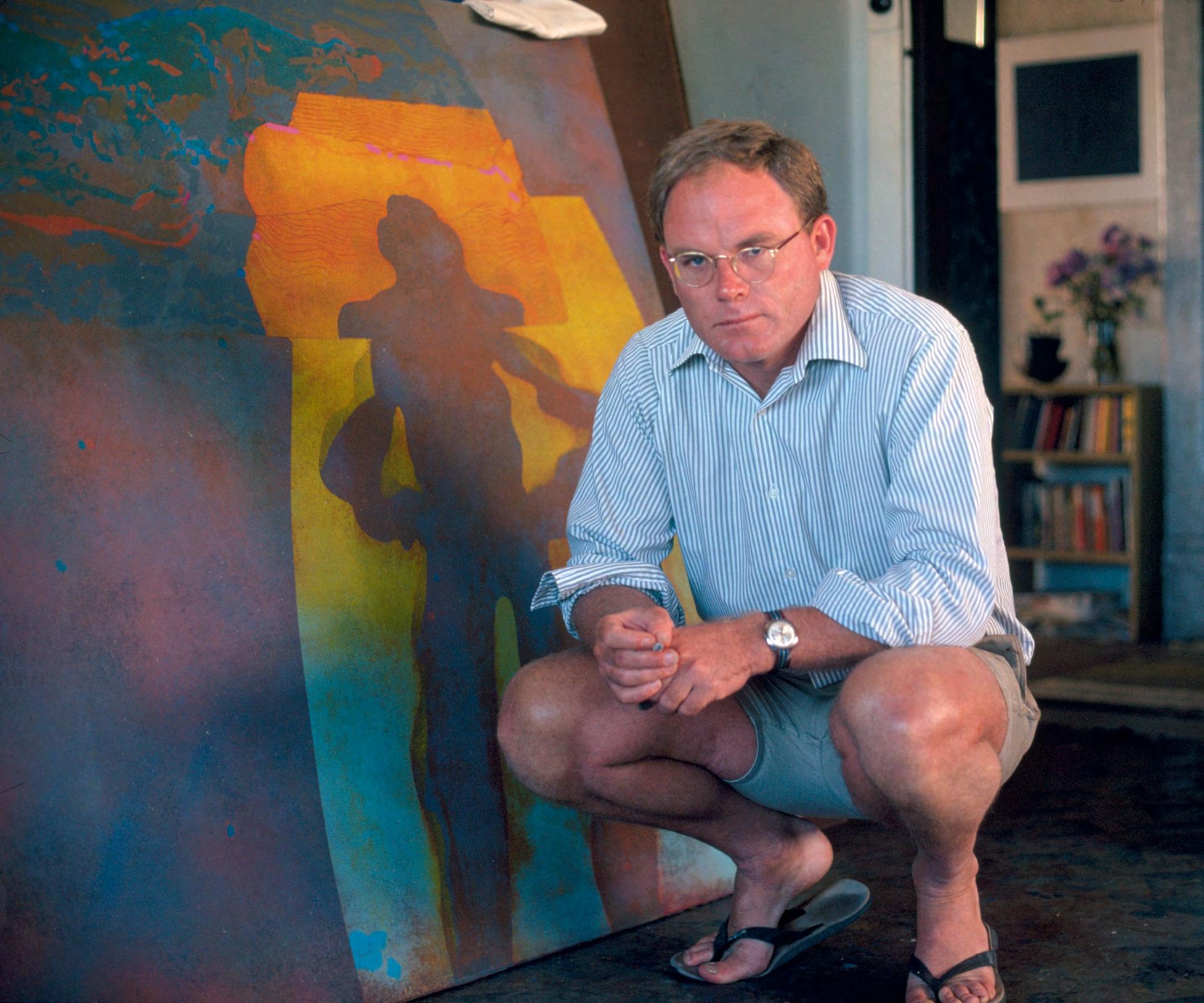

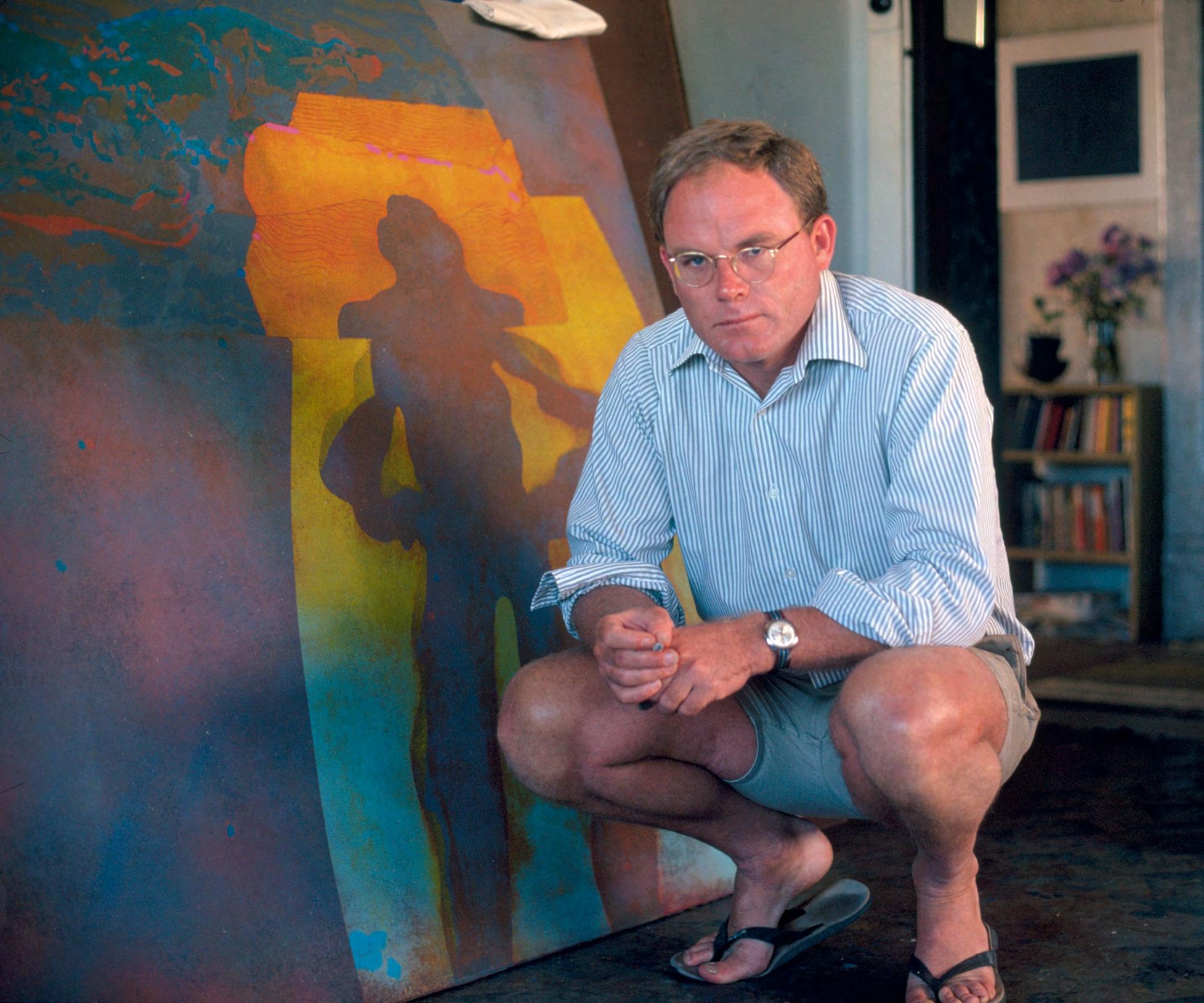

RIGHT George Haynes, 1979, Fremantle.

Photo: Richard Woldendorp. Sourced from the collections of the State Library of Western Australia and reproduced with the permission of the Library Board of Western Australia.

Art should be so enthralling that it stops time.

George Haynes, 2018

6 7

Preface: In searcH of PaInTInG

George Haynes has had a significant impact on shaping Western Australian art, and it is entirely appropriate that his achievement, influence, and legacy is addressed with fresh eyes for a new audience.

It is fitting that Haynes is given critical space now, thirty-five years since his last major survey exhibition in Western Australia and in the absence of any comprehensive assessment of his artistic lifetime to date. This is an opportunity to evaluate Haynes’ work and pay tribute to the broad affection and regard for his wide artistic repertoire and valuable contribution to Western Australia’s cultural inheritance.

Now in his eighties, Haynes’ work can be regarded as a lifelong testament to the inherent truth and persistency of representational and figurative art in Perth. For more than forty years he has enjoyed a commanding presence within the art market and gallery cognoscenti. His work has been collected by state and national collections and by his many local admirers for decades. As a teacher and mentor his output has had a catalysing effect on his followers.

In Western Australia, Haynes’ favour as an artist is due to his truthful chronicling of Perth’s suburban landscapes and domestic interiors, rendered in charcoal drawings and chromatically vibrant paintings in oils and gouache. His career, which includes interludes working in remote Western Australia, could be seen as a self-imposed challenge to picture the affronting light and sapping heat of the Perth summer, with its pools of reflected and radiant colour. In the Perth summer, the space and light of backyards and ocean frontages are engaged in what John Stringer described in his catalogue essay in 1988, as a ‘subtle drama’ of temperature and sensory intrigue. Haynes’ ability to open our hearts and minds to the nature of perception, and by extension the precious complexities inherent in the interconnected physical world around us, is also a matter for recognition.

The genesis of this volume rests within the series of monographs on established Western Australian artists published by Art Collective WA. In capturing Haynes’ breadth of output, the book exists as a timely record of his lifetime of creativity. The contribution of this book, above its comprehensive reproductions, are the insightful essays which provide readers an understanding of Haynes’ idiosyncratic character and how this has shaped his career.

Dr Sally Quin provides a detailed assessment and scrutiny of Haynes’ grounding in London art school methodologies and a deeper insight into the

9

Andre Lipscombe

LEFT George Haynes, 1976, Victoria Park. Photo: David With.

Haynes’ ability to open our hearts and minds to the nature of perception, and by extension the precious complexities inherent in the interconnected physical world around us, is also a matter for recognition.

that Art Collective WA, and its generous donors, have made to rectify this lack, over its first decade.

I would like to pay tribute to George and thank him for his generosity and steadfast dedication to the perfection of his craft, which for many is indelible with his authentic agency beyond the canvas.

Andre Lipscombe is a visual artist, writer, educator and Curator of the City of Fremantle Art Collection. He has a long-standing career in the visual arts sector, including roles in museums and artist-run organisations, working in both regional and metropolitan settings. He has knowledge and expertise in both contemporary and historical arts practice in Western Australia.

challenges and impacts of transitioning family life to making art in Perth. Quin provides a deeper understanding of Haynes’ connection with Perth’s cultural scene and hard learned drawing skills, which he championed and applied to his teaching roles in Perth, influencing a coterie of younger artists.

John McDonald charts Haynes’ practice and awakening to a colourist mantra after 1970, which Haynes applied equally to his representational and abstract subjects. McDonald also writes convincingly about Haynes’ lifetime of compulsive exploration and apparent scattergun approach to his projects and career choices – inconsistency that impacted his recognition and success in the gallery sector in the eastern states.

I share Quin and McDonald’s view that Haynes’ triumph rests in his penetrating hand-eye control and attention to the lessons in the observation of light, made possible through frequent engagement with drawing and painting directly from his life subjects. In Perth Haynes is unmatched for his accurate tonal fluency, setting a local standard for an instinctive exactitude in representational drawing, framed by a recognisable black and white graphic ‘signature’. His authentic observations of light in nature and the significance that the work is held by Western Australian audiences is a measure of his hardearned success in this area of his practice.

To fully appreciate Haynes’ dynamism and inventiveness, motivation and commercial pragmatism as an artist, scrutiny of his character is useful. Haynes has little concern for contemporary art practice, which is not unique within his generation of Perth painters who are deaf to fashionable trends and arguments of cultural politics. Perhaps from this volume it will be possible to conduct a full appraisal of Haynes’ mature work and arouse in the mind of the reader a fuller appreciation of the trajectory of his creative processes. To create a richer evaluation of this quintessential Perth product, any stocktaking must include genuine appreciation for his skill and courage (including his mature diversions with sculpture and public art) and his occasional displays of uninhibited dissent with the currents of ‘political correctness’ in the Perth art scene.

It would be nice to think that all Western Australian artists of substance and maturity, regardless of their longevity or level of commercial success, can gain public recognition for their achievements over a lifetime. Unfortunately, art writing in the form of a monograph is still a rarity in Western Australia, and it is with much gratitude and pleasure that I acknowledge the important role

10

RIGHT George Haynes, 1978, Karratha. Photo: Nigel Hewitt.

Haynes thrives on the challenge of working from life. Photography has never been a weapon in his arsenal. His keen eye is trained to grasp fundamentals with tremendous accuracy and set them down with divine patience, for it is not simply a game to retain relationships of scale, distance, texture and tone, but also to make the inert and unmarked surface function as an active element in the design.

12 13

John Stringer, 1988

from cHelsea To PerTH:

THe early Work of GeorGe Haynes, 1962–1972

I went into the Zoology exam and I read the paper, and saw I could answer it all. Then I looked out of the window and it was a beautiful June day so I walked out of the exam … I wanted to go out into the fields and it was a lucky thing …1

Interview with the artist, 17 December 2022. All quotations are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

2 Stringer, J 1988, George Haynes: A Survey, 3 Decades of Painting, exhibition catalogue, 12 November 1988–29 January 1989, Art Gallery of Western Australia, p.7.

The exam to which George Haynes refers was not insignificant, being one of the requirements for entry into medical training at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, undertaken in his final year of school. Though he was ultimately accepted on the basis of a distinction in chemistry, the decision to walk out into nature at this particular moment, without hesitation, seems prescient. Haynes says he had no lack of interest in his medical studies – perhaps driven by the same searching curiosity that would direct his later painterly investigations of natural phenomena. But the prospect of becoming a doctor held no appeal.

Growing up in various parts of Kenya, Haynes was fascinated by the world around him and from an early age sketched and painted objects and scenes both real and imagined. Childhood sketchbooks, according to John Stringer, curator of the artist’s retrospective exhibition in 1988–89, reveal ‘a precocious talent for tackling difficult perspectives, foreshortening and action’.2 From the age of fourteen Haynes had been at boarding school in Bath, England, travelling back to Kenya during the summer holidays. On finishing school in 1957 Haynes returned to Mombasa, planning to spend a year there before commencing his medical studies. But later that year he was called up for national service, in the context of political unrest in Kenya in the 1950s, and his father urged him to leave the country as soon as possible. Recognising that his son had no desire to practise medicine, and seeing that he spent all his time painting, Haynes’ father now encouraged him to commence art school instead.

Walking out into beauty, and finding the medium with which to express a sense of wonder in it all, indeed amounted to ‘a lucky thing’. Perhaps it is no surprise that the window with a view onto the world outside has been a recurrent motif throughout Haynes’ career. More than mere observation of reality, every painting, according to Haynes, ‘starts with a feeling … I try to paint my frame of mind’ – the mind seeking nature, the mind that moves between a sunny disposition and melancholy.

This essay traces the first decade of Haynes’ artistic development, which moves from art school in London to a life in Perth, Western Australia. Though nothing like the heady London art scene, this new locale elicited different kinds of enchantment and aesthetic possibilities, which have sustained the artist creatively for close to sixty years.

15

Sally Quin

LEFT Near Nerja Andalusia 1961, oil on board, 40 × 20cm. Collection of the artist.

3 Sorensen, L (ed.), ‘Gowing, Lawrence, Sir’, Dictionary of Art Historians https:// arthistorians.info/gowingl, accessed 28 January 2023. During his tenure at Chelsea, Gowing was a trustee of the Tate Gallery (1953–60; 1961–64), and before his appointment had written the important monograph Vermeer (1952). He remained Principal at Chelsea until 1965.

4 ‘London Art Schools’, Tate Research Publication, 2018, https://www.tate. org.uk/about-us/projects/art-schooleducated/london-art-schools, accessed 8 February 2023.

5 Bruce, L 1986, The Euston Road School, Scolar Press, London, pp.175–177.

6 Ibid., p.325.

7 Ibid., p.3.

In 1958, arriving from Kenya to London’s Empire Air Terminal at Victoria Station, Haynes asked an official where he might find the nearest art school. He was advised to catch the number 11 bus, which would take him to the Chelsea School of Art. The apparently random mode of selecting Chelsea might be considered another ‘lucky thing’, as the school was entering a period of positive transformation under the leadership of Lawrence Gowing, the distinguished artist, art historian, educator, and curator.3 1958 was Gowing’s first year at Chelsea, and Haynes was the first student to be interviewed by him, accepted based on a portfolio of paintings and drawings from Mombasa.

Chelsea had a small permanent staff – Gowing as head of painting, a head of sculpture, a head of printmaking, and the school’s secretary. Other teaching staff were practising artists around London who worked at Chelsea one day a week. Rather than employing art historians, these practising artists also taught art history and theory, a combined approach distinctive of Chelsea tuition.4 Haynes describes the dominant characteristic of the school as ‘Euston Road’, which refers to the group of painters who taught or trained at the School of Drawing and Painting in Euston Road, London, between 1937 and 1939 – Gowing having been one of the school’s more prominent students.5 In the decades that followed, British art was influenced by Euston Road, not so much in terms of emulation of style, but in relation to a particular approach and method, described by one of the school’s founders, Victor Pasmore, as a ‘renewed objectivity … based on purely optical phenomena tied strictly to the measurable properties of both the visual object and the picture plane’.6 The canvas was carefully marked up with various dots and lines indicating points of measurement, before painting began; a method based on the proportional relationship of forms, as against traditional one-point perspective. Haynes recalls the arduous nature of drawing practice at Chelsea, particularly a class taught by Fred Brill, in which students were required to draw the negative shapes in a pile of chairs, resulting in ‘a splitting headache after an hour of really accurate drawing’.

While this method of measurement was used at other art schools in London, it was, according to Haynes, ‘all prevailing at Chelsea’. The discipline of this approach has remained fundamental to Haynes’ practice – but perhaps only because its rigour was combined with encouragement of free development of style. Indeed, the prospectus of the Euston Road School was explicit: ‘No attempt … will be made to impose a style and students will be left with the maximum of freedom of expression.’7 Recently Haynes has said: ‘My leanings were more expressionistic – but I was very grateful [for the Euston Road method]’. This is very much in keeping with the Chelsea philosophy, Haynes describing both the discipline and the ‘very exploratory’ nature of students’ work there. Today Haynes uses techniques of measurement and picture-plane planning more loosely, but they remain the foundation from which expression and experimentation proceed.

RIGHT FROM TOP Recumbent Figure, 1964, oil on board, 91 × 91cm. Private Collection Darlington Landscape 1965, oil on board, 121.8 × 136.8cm. Private Collection.

16 17

LEFT A Pool for Rothko 1970, acrylic on canvas, 157.5 × 139cm. State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia.

RIGHT A Yellow Pool for Rose, c.1970, acrylic on canvas, 85.2 × 98cm. The University of Western Australia Art Collection.

‘London Art Schools’, Tate Research Publication, 2018, https://www. tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/artschool-educated/london-art-schools, accessed 8 February 2023.

9 Ibid.

10 In 1961, Kitaj and Hockney, together with Peter Blake, exhibited in Young Contemporaries at the Institute of Contemporary Arts which heralded the arrival of British pop art.

11 ‘A Timeline of American Art in PostWar Britain: 1950–59’, in Modern American Art at Tate 1945–1980, Tate Research Publication 2019, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/ publications/modern-american-artat-tate/timeline/1950s, accessed 22 January 2023. Important exhibitions of American art shown in London during Haynes’ years at Chelsea included: Jackson Pollock (1958), Whitechapel Art Gallery; Seventeen American Artists and Eight Sculptors (1958), United States Information Service (USIS) Library – showing works by Ellsworth Kelly, Ad Reinhardt and David Smith; The New American Painting (1959), Tate Gallery – a major exhibition of abstract expressionist art; West Coast Hard-Edge: Four Abstract Classicists (1960), Institute of Contemporary Art, in collaboration with USIS; American Abstract Painters (1960), Arthur Tooth & Sons; Jackson Pollock and New New York Scene (both 1961), Marlborough Fine Art; Mark Rothko: A Retrospective Exhibition: Paintings, 1945–1960 (1961), Whitechapel Art Gallery; Vanguard American Painting (1962), USIS –where UK audiences first saw the art of Robert Rauschenberg.

Chelsea was, of course, part of a bigger cultural scene and one of the characteristics of London art schools at the time was the ‘cross-fertilisation’ of teachers and students moving between them.8 The teacher Haynes considers having had the greatest influence on his studies was Anthony Whishaw who attended Chelsea (1948–52) prior to moving to the Royal College of Art (1952–55). The student most admired by Haynes, Patrick Caulfield, studied first at Chelsea a few years ahead of Haynes (1956–59), before moving to the Royal College. Despite such interactions, London art schools each had their own distinctive style.9 Haynes summarises the differences: Chelsea was Euston Road; at the Slade School of Fine Art students applied paint thickly in the manner of Frank Auerbach; and the Royal College was distinguished by its Pop aesthetic. During the years Haynes was at Chelsea, R.B. Kitaj and David Hockney were at the Royal College (1959–61, and 1959–62 respectively).10

It was fortuitous to be an art student in London during this period: a number of institutions which focused on contemporary art, such as the Whitechapel Gallery, the Tate Gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, as well as commercial galleries interested in showing progressive art, were located there; and from 1950 onwards there was the increasing presence of exhibitions of contemporary art, many of which came from New York, at that time the capital of the art world.11 Haynes recalls the excitement surrounding the exhibitions of contemporary American art, particularly at the United States Information Service (USIS) Library, referred to by the artist as the ‘Embassy’ shows. Such

18 19

12 Stringer, ibid., p.8.

13 The Fine Art Society Ltd, https://www. thefineartsociety.com/exhibitions/ 150-anthony-whishaw-ra-downstreamflood/, accessed 8 February 2023.

exhibitions had an immediate effect on the activities of London art students –Haynes noting that, after the 1958 USIS show, students came to Chelsea with enormous pieces of Masonite to paint on, hoping to emulate something of the bold, audacious works they had seen. Of all the exhibitions Haynes saw in those years, it was the Mark Rothko show at the Whitechapel, in 1961, which had the most deep and lasting impact.

At this time, Haynes was particularly interested in artists’ use of line and brushstroke, as opposed to colour. He greatly admired Brett Whiteley, seeing his first London solo show at Matthiesen Gallery in 1962. He also appreciated earlier protagonists of European modernism, such as the ‘lively lines’ of Egon Schiele’s drawings and Oskar Kokoschka’s ‘breezy brushstrokes’. Stringer also notes Haynes’ early interest in ‘the expressionist COBRA painters who clung to drawing’. He was, of course, also engaged with recent developments in British painting,12 particularly the figurative art of the so-called School of London. According to Haynes, Francis Bacon, then at the peak of his powers, ‘influenced everyone’. Haynes was a regular visitor to the Beaux Arts Gallery on Bruton Place where Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff showed their expressive, impasto-laden paintings.

During his student years, Haynes was looking at different modes of abstraction: abstract expressionism in its American and European forms, colour field painting, hard edge minimalism, and early twentieth-century European modernism; as well as figurative art with abstract qualities, as in the early works of American and British pop art, and the painting he saw at Beaux Arts.

Though primarily a figurative artist, with his works drawing on the observation of reality, expressive abstraction is also a long-standing characteristic of Haynes’ work. This mixed and dynamic approach was perhaps shaped by the combination of Chelsea’s ‘exploratory’ environment, and the variety of modern and contemporary art he experienced in this period. The primacy of painting and drawing themselves, variously influenced by perceptual experience and art new and old, was summed up by Whishaw, stating that ‘each painting and work on paper makes its own separate demands’.13

ARRIvAL In WEsTERn AusTRALIA

After graduation in 1962, at the age of twenty-four, Haynes visited Perth, Western Australia, where his parents had settled the year before. Initially he had no intention of staying, but within three months of arrival he and his wife had welcomed their first child, and it seemed a good idea to stay. Artistically, Haynes was immediately captivated by the beguiling new environment – ‘the light! Never seen shadows like it!' Over the next decade he would develop a mode of expressing this light, and shadow, in startling, original ways.

A glowing reference from Gowing on graduating from Chelsea (1962) indicates that Haynes was an exceptional and determined student. Of the student works that have survived, two undated figure studies and the landscape, Near Andalusia (1961), already show sophisticated handling of tone and experimentation with planar modelling. Within the first decade of his arrival, he quickly became known in the Perth art scene, combining a regular exhibiting schedule with art teaching, and a series of labouring jobs to keep the wolf from the door. Of great importance to Haynes in his year of arrival was meeting artist Robert Juniper whose work he had seen at Skinner Galleries,

Over the next decade he would develop a mode of expressing this light, and shadow, in startling, original ways.

20 21

RIGHT A Side Stroke, c.1969, acrylic on canvas, 97 × 170cm. The University of Western Australia Art Collection.

14 Richard Jasas interview with George Haynes, August 1988, quoted in Stringer, p.7.

15 Sharkey, C (2004), ‘Rose Skinner, Modern art, and the Skinner Galleries’, Early Days: Journal of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.373–384. The article includes discussion of the cultural milieu of Perth in the late 1950s through the 1960s, including other exhibiting venues such as The Triangle and Old Fire Station Gallery. See also Maria E. Brown, Art and Artists in Perth 1950–2000, unpublished PhD Thesis, The University of Western Australia, 2018, pp.73–89.

then a commercial gallery at the centre of the contemporary art scene in Perth. Nine years older than Haynes, Juniper had trained at the Beckenham School of Art in Kent (1943–47) and had a growing reputation in Perth and across Australia. They met at Juniper’s home in Darlington in the Perth Hills and an immediate bond was formed, Haynes stating that though they were ‘poles apart [artistically] we respected what each other was doing … we talked a lot about art and painted together’. Life drawing classes were initiated with Juniper and other local artists, Brian McKay and Guy Grey-Smith.

The earliest of the Perth paintings, Sing Praise a New Day is Born, and Hear Us O Lord, From Heaven thy Dwelling Place (both 1962–63), are reminiscent of the European abstraction of Tachisme and COBRA, but also of Auerbach’s thick and textured application of paint. Each work depicts what appears to be a sun, rising or setting, at the horizon line or the point at which blocks of overlapping, visible brushstrokes meet. The titles of the works (taken from Cornish hymns) remind us that, for Haynes, abstraction is not a vehicle for depicting a transcendence of reality, but rather is a way to express a tangible aspect of reality, or to render visible a sense of the intangible within the real – the titles alluding to the spiritual dimensions of a new day dawning and the earthly place from which a transcendent heaven might be imagined. At this very early stage it was clear the artist did not feel bound to, or limited by, abstraction in its dominant international modes. Haynes’ early abstraction was connected to reality and stimulated by observing it – showing just how mysterious or otherworldly that perceptual experience can be.

The use of bright, saturated colours had not yet become a preoccupation of Haynes’ work, as it would so spectacularly some five years later. This was due in part to the fact that the artist’s palette was determined by the paints that he could afford, and that he imported from L. Cornelissen & Son’s in London. In a 1988 interview with Richard Jasas the artist elaborates:

I was poor and I used to import paints from England from Cornelissen’s [sic]. Their best colours were raw umber and yellow ochre, burnt sienna, and Indian red. So those were the paints I used.14

Sing Praise a New Day is Born employs these earth tones with its background of yellow ochre, a sun of burnt sienna, and patches of raw umber and Indian red also apparent.

Juniper introduced Haynes to Rose Skinner in 1963 and he became part of the Skinner stable of artists in that same year. Skinner Galleries had opened in 1958 and formed part of a thriving cultural milieu in Perth at the time which included David Foulkes-Taylor’s Triangle Gallery and Rie Heymans’ Old Fire Station Gallery.15 These contemporary exhibition spaces were complemented by art criticism published in The Critic (1961–70), a journal produced at the University of Western Australia with regular writing on contemporary art by Tom Gibbons and Patrick Hutchings.

22 23

ABOvE Girl on the Beach, c.1966, oil on board, 35 × 40cm. The University of Western Australia Art Collection.

Haynes’ early abstraction was connected to reality and stimulated by observing it – showing just how mysterious or other-worldly that perceptual experience can be.

16 Russell, J 1965, ‘Home-thoughts about the Wardle Prize’, Art and Australia, 1 June, p.26.

In 1963, assisted by Skinner, Haynes enjoyed his first interstate showing in Paintings from the West: 14 Western Australian Painters, at the Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia, Melbourne. In 1964 he was given his first solo show at Skinner Galleries, officially opened by Juniper. It was quickly successful, and all works sold. To offer a sense of the gallery’s activities, other artists exhibiting that year included Sam Fullbrook, Jacqueline Hick, Juniper, Sidney Nolan, John Olsen, Michael Shannon, Albert Tucker and Fred Williams. Additionally, there were exhibitions of Norwegian design and contemporary prints from Japan. A locus for local, national and, on occasion, international art and design, Skinner Galleries brought together patrons from the worlds of art, literature, politics and business.

In 1965 Juniper and Haynes showed in a joint exhibition, opened by modernist architect Geoffrey Summerhayes. Haynes recalls with good humour his dejection at the time, seeing the red stickers proliferate on Juniper’s wall, but he was soon to have a second sell-out show of his own at Watters Gallery in Sydney in 1966. Indeed, one of the benefits of showing with Skinner were the connections it offered to commercial galleries and dealers nationally, such as Frank Watters and Rudy Komon.

Also significant were the important national art competitions hosted by Skinner Galleries, such as the T.E. Wardle Art Prize held in conjunction with the Festival of Perth. Rose Skinner would invite a leading critic as judge; John Russell in 1965 and Robert Melville in 1966. In 1965 the prize went to Brett Whiteley for Woman in Bath V (1964), but writing in Art and Australia Russell also praises the ‘delightful painterly freshness’ of Haynes’ entry.16 In 1967 the Festival Invitation Art Prize was judged by leading British painter Patrick Heron, and Haynes’ interaction with him during his visit remains memorable to the artist to this day. Though Haynes exhibited in art prizes at the Art Gallery of Western Australia and other galleries, the most enduring relationship during the 1960s

24 25

ABOvE FROM LEFT Sing Praise a New Day is Born, 1962–63, oil on board, 91.3 × 61cm. Private Collection. Hear Us O Lord, From Heaven Thy Dwelling Place, 1962–63, oil on board, 91.3 × 61cm. Private Collection.

was with Skinner Galleries where he would continue to exhibit regularly in group and solo shows until 1976, the year the gallery ceased operation.

Haynes’ strongest memories of his association with Skinner Galleries are the friendships he formed with other artists who exhibited there, especially with Juniper, Sam Fullbrook and Fred Williams. When they were together, away from their dealers and the hype of the gallery, they would talk almost exclusively about art. Haynes has remarked that he simply wanted ‘to learn all I bloody can about painting’, a sentiment perhaps shared by the others in this group. During this period, Juniper and Williams, in particular, were developing distinctive modes of representing the Australian landscape. Though Haynes too would develop a mature style deeply affected by the quality of Australian light, and the clarity of colour and form revealed in it, it did not manifest in depictions of a parched interior or unvariegated bush landscape. True to Haynes’ inclination to experiment, while living in Darlington he did produce one landscape in this mode, Darlington Landscape (1965). Thickly painted in subdued tones, the work combines unresolved perspectives – aerial, front on, perhaps remembered, perhaps observed. Though pleased with the work, Haynes did not continue in this manner, the red stripe in the lower right corner presaging things to come.

By Haynes’ own admission no consistent style seems to have been formed in these early years: ‘I kept chopping and changing and not developing any particular thing’, enjoying different artistic influences and painterly approaches, as his training had encouraged. This ‘chopping and changing’ nonetheless produced an intriguing series of early works reflecting the artist’s eclectic and exploratory impulses in his favoured subjects of interiors, the figure, and the natural world, where observed reality is infused with imagination and feeling. Such variety may also reflect Haynes’ teaching activities, which proceeded alongside his practice during these years. In 1963 Haynes opened the South Bank Art School in South Perth where he produced paintings as demonstration pieces, imparting particular techniques or ideas to students along the way.

Over the course of 1964, and working from a life model, Haynes painted Recumbent Figure (1964), a masterclass in fundamental elements of design and draughtsmanship (combining flat pattern with figuration and classical foreshortening) in a restricted colour range, and Berlin Self-Portrait (c.1964), a more experimental or perhaps even improvised arrangement of shape and colour. While a semi-abstract head and shoulders self-portrait can be seen in the bottom centre of the canvas, this observed reality is combined with memory, invented figures, abstract design and amorphous shapes. Significantly, the painting is focussed on chroma rather than line, with heavy colour saturation and dynamic interactions of red and blue, an early example of prominent primary colours. Looking at the image almost sixty years later, Haynes notes a connection to the early Pop aesthetic of Kitaj but adds, ‘to me, you know … you don’t keep on trying to do Kitaj’s, that’s what I say’.

26 27

LEFT Berlin Self-Portrait, 1964, oil and acrylic on board, 122 × 137.5cm. Private Collection.

9 780994284266 > ISBN 978-0-9942842-6-6

George Haynes. Portrait by Robert Frith, Acorn Photo 2023.

George Haynes. Portrait by Robert Frith, Acorn Photo 2023.