ONE DAY

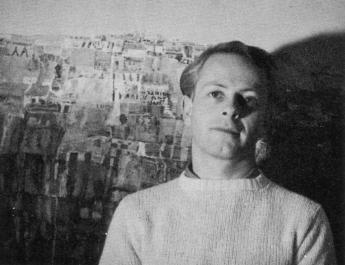

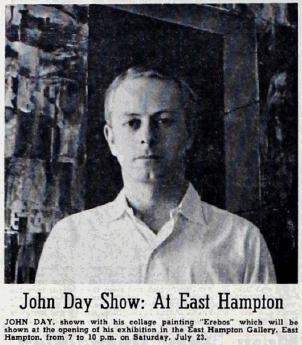

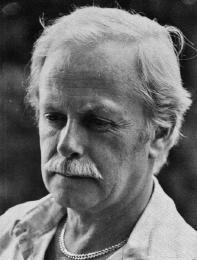

John Day, an artist, died yesterday in the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. He was 49 years old. Mr Day's paintings have been exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

He was a professor of art at William Paterson College in New Jersey. Mr Day was born in Boston and is survived by his mother, Josephine Day of Waterford, Conn., and his brother, Michael Day of Ann Arbor, Mich.

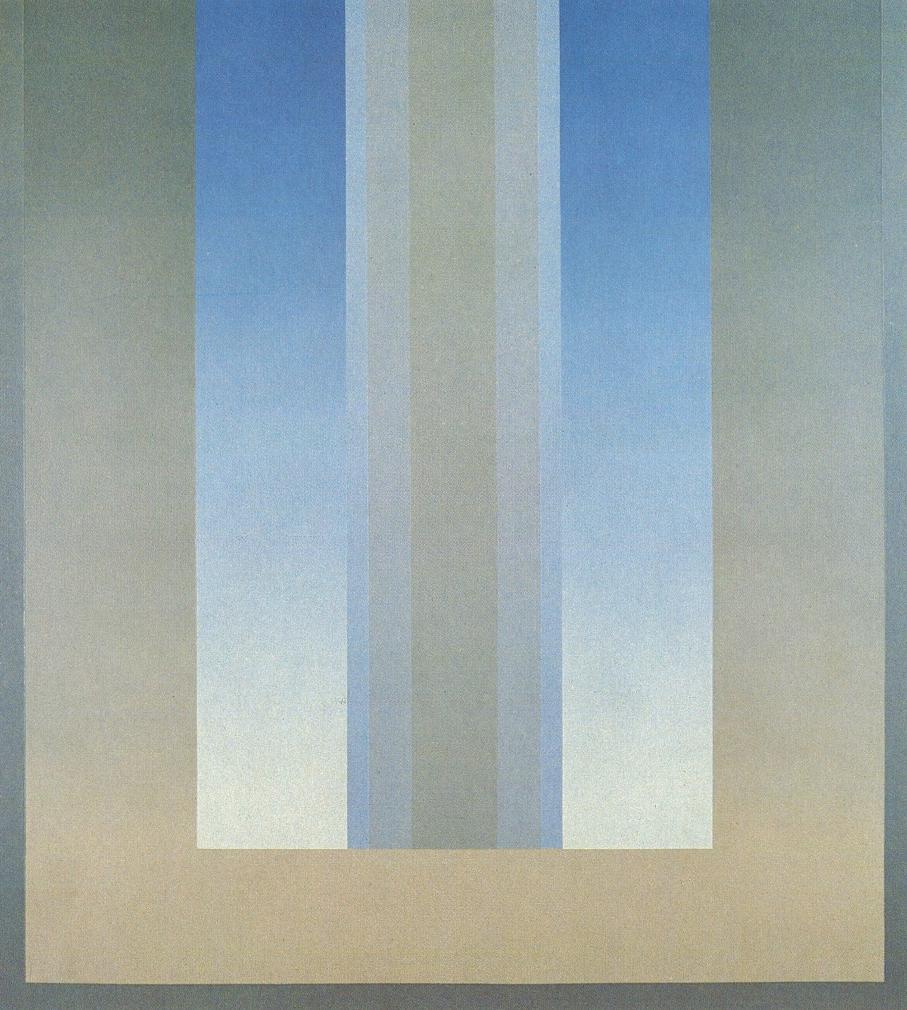

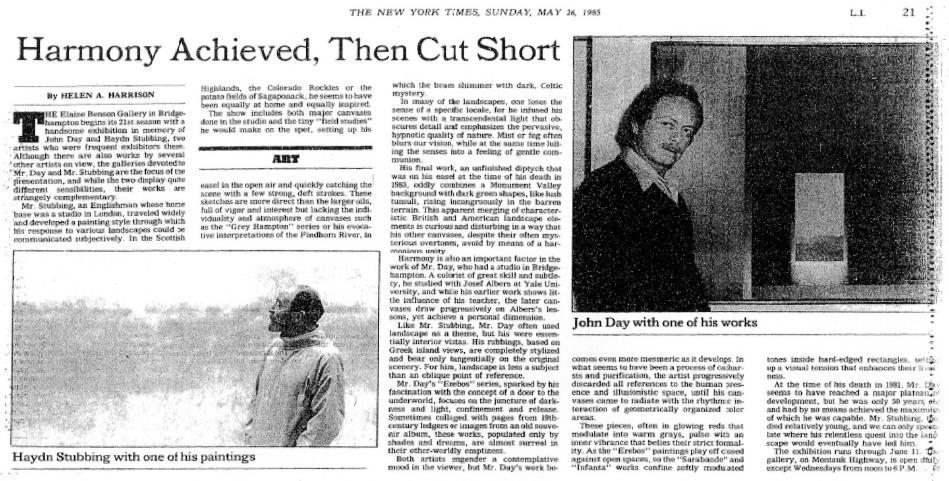

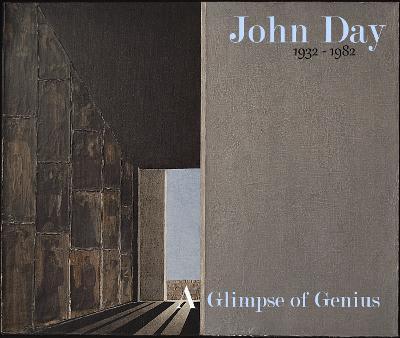

POSTHUMOUS EXHIBITIONS celebrating John Day’s mesmerizing art were staged at the West Hampton Guild Hall in 1983, the Montclair Art Museum and New London’s Lyman Allyn Museum in 1984, and the Elaine Benson Gallery in Bridgehampton, Long Island, in 1985.

JOHN DAY’S ESTATE – a treasure-trove of 92 paintings, 30 reliefs, 14 collages and over 500 drawings – was acquired that year by his friend Guy Cooper (1937-2014) and left in storage in Secaucus, New Jersey. Cooper moved to London with his partner Gordon Taylor and the collection was forgotten about for a quarter of a century, before being shipped to London in 2011. In February 2020 it was acquired by art consultant Iain Brunt.

John Day’s Art has not been seen in public since 11 June 1985. HIS TIME HAS COME AGAIN.

NEW YORK TIMES – 16 APRIL 1982 NEW YORK TIMES – 26 MAY 1985

John Day’s parents Josephine Hamblin (1904-95) and Kenneth Knowlton Day (1901-58) married at Hyde Park Congregational Church (right) in south Boston on the afternoon of 18 June 1928. Kenneth had graduated as a Doctor from the Boston University School of Medicine that same morning.

John Day’s paternal grandfather, Edward Hawley Day (1867-1952), was born in Waltham, Vermont – son of Whitfield Myron Day (1827-76) and Nancy Stark Hawley (1838-1915) of neighbouring Vergennes. The Hawleys descended from Gideon Hawley (1687-1731) of Bridgeport, Connecticut… where John Day would later teach. John Day’s paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Jane Knowlton (18721956), descended from Deer Isle lobstermen in Downeast Maine. Elizabeth’s father, Captain John Buckminster Knowlton (1827-90), was born on Isle Au Haut in the ‘Merchant Row’ archipelago south of Stonington – where he and other family members are buried in Knowlton Cemetery.

‘I can’t describe Deer Isle – there is something about it that opens no door to words’ wrote John Steinbeck after visiting in 1960. Steinbeck found the mentality of its inhabitants forged in the local granite quarries, adding: ‘I would hate to try to force them to do anything they didn’t want to’ – as if commenting on the determinedly individual artistic path John Day would pursue. Pretty Stonington, to Steinbeck, ‘closely resembles Lyme Regis in Dorset. Its houses are layered down to the calm water of the bay. It does not look like an American town at all.’ Many artists – such as John Marin in 1924 (left) – shared his enthusiasm.

Edward and Elizabeth Day, née Knowlton, lived for decades at 32 Beacon Street in industrial Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where Edward worked as a grain-buyer for J. Cushing & Co. He retired at 70, after a late-career managerial post with General Mills helped the couple move to residential Waban.

They had four children. John Day had two uncles: Clarence (1898-1942), who attended Norwich University in his father’s native Vermont; and Theodore (1906-91), known as Ted, who settled with his wife Mildred Billings (1905-2005) in the small town of Pepperell near the Massachusetts border with New Hampshire (where Edward and Elizabeth joined them in 1942). John Day’s aunt Muriel (1893-1974) married a Norwegian, Salve Gustav Carlsen Traegde, in Boston in 1917, and had seven children.

John Day’s maternal grandfather, Howard Malcolm Hamblin (1840-1912), was a scion of a venerable Boston family and a local property owner. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1862 but never practised. He married Frances C. Hamblin (1864-1948) when he was past sixty, she nudging forty. They lived in the Boston suburb of Hyde Park. Frances was a leading light on the local social scene: Treasurer of the Hyde Park Thought Club, and a keen organizer of cultural events. In 1905, for instance, she arranged a song recital by Frederick W. Bancroft (1855-1914) at the Hotel Tuileries on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue. Bancroft had studied with Luigi Vannuccini in Florence. Frances, in turn, would send her daughter Josephine abroad for musical tuition.

Josephine was an only child. Her father died when she was eight. A few months later, on 23 November 1912, she was first mentioned in the press – leading the Hyde Park Baby Parade clad in Brahmin-style ‘colonial costume.’ In 1915 she recorded Ivor Novello’s wartime hit Keep The Home-Fires Burning for pianoroll. On 16 May 1916, while a pupil at Fairmount School, she regaled the Thought Club’s AGM with her own ‘piano selection.’ As a teenager she also engaged in amateur theatricals and dance.

On 22 April 1921 the Boston Evening Globe announced that Josephine would be leading a Grand March of 100 Children at the Hyde Park May Festival – running a photo of the doe-eyed brunette (left) to boot. A few weeks later she graced her graduation ceremony from Hyde Park High School with a ‘song of her own composition’ before departing for France to study piano with Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) – arguably the greatest music teacher of the 20th century, whose pupils would later include Daniel Barenboïm, Michel Legrand and Quincy Jones.

The link between the Boston and French music scenes was Georges Longy (1868-1930), a Paris Conservatoire graduate who played Principal Oboe for the Boston Symphony Orchestra before founding the still-extant Longy School of Music. The celebrated music critic Olin Downes declared that ‘Longy probably influenced the musical life of Boston more than any other man.’

Josephine was among the first intake of the American Music School that opened in the Palace of Fontainebleau, 40 miles south of Paris, in Summer 1921. In the official photo she is pictured between Aaron Copland (third man from right) and Herbert Elwell (bottom centre, beneath fellow-composer Zo Elliott). Singer Victor

Prahl is far right; bespectacled organist Marshall Bidwell far left. Nadia Boulanger, in a white blouse, sits front centre in this majestic photograph, four seats along from organist and composer Charles Widor (of Toccata fame).

Copland studied with Nadia Boulanger in Fontainebleau and Paris from 1921-24, terming her ‘an intellectual Amazon’ who ‘knew everything there was to know about music,’ and dedicating his Symphony for Organ & Orchestra to her. Nadia Boulanger, as organist, played the work in Boston on 21 February 1925 – with, one may be confident, Josephine and her mother in the audience. She and Nadia established an enduring rapport –perhaps because they both had ageing fathers (Ernest Boulanger, a professor at the Paris Conservatoire, was 72 when Nadia was born).

After her marriage to Kenneth Day in 1928 Josephine and her husband settled in the burgeoning town of Malden, a few miles north of Boston. Their wooden house at 142 Summer Street no longer stands. John Day – named after his great-grandfather, John Buckminster Knowlton (1827-90, far left) – was born there on 27 May 1932. The physical resemblance between the family patriarch and John Day’s cousin Frank (1936-2016, left) is striking.

John Day did not, according to his boyhood friend John Bowman, grow up ‘in any great luxury’ – although the 1940 U.S. Census reveals that the family had a live-in maid. John’s grandmother Frances was also part of the household, her inherited wealth having dwindled during the Great Depression that overlapped with John Day’s childhood years.

Day’s mother Josephine – whom Bowman remembers as ‘a warm, hospitable woman’ –gave piano lessons. His father Kenneth combined his duties as a doctor with studies to

become an anaesthesiologist. Bowman found him ‘rather distant… always in a hurry to be elsewhere.’ Family as well as medical matters may have been on his mind: his sister Muriel, now living a couple of miles away in Stoneham, had been abandoned by her Norwegian husband and left with seven youthful mouths to feed.

Greater tragedy struck at midnight on 21/22 July 1942, when Kenneth’s elder brother Clarence was hit by a train in Waterbury (where he had risen to the post of Chairman of the Pilgrim Plywood Corporation). Newspaper reports eschewed talk of suicide, declaring Clarence’s car to have stalled while crossing the tracks. He was already a widower. His four teenage daughters were left orphaned.

Whatever the parental finances expended on family solidarity, John Day did not go short. ‘He never took up any weekend or summer job like most of his schoolmates’ remembers Bowman. Nor did he join other boys playing in the street. ‘Exactly what he did with his spare hours I cannot say’ adds Bowman. ‘Quite possibly he was already demonstrating his interest in art.’

Day’s first oil painting was sold in Autumn 1947 at an invitational exhibition in Filene’s department store in downtown Boston (left). By then Day was attending Malden High School along with Bowman, Ruth Wolff and Kempton Webb, all born within a few months of each other. ‘Our friendships were so intertwined we were a quartet’ states Wolff (later a celebrated playwright). ‘I thought of us as the Four Musketeers.’

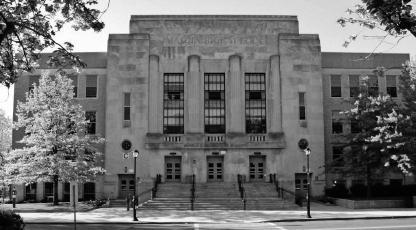

Malden High School (right), founded 1857, was one of the leading schools in Massachusetts. Pupils studied Latin as well as French or German. John Day worked for the school newspaper (The Blue and Gold) and was a member of the English Club, Latin Honor Society, Cercle Français and Drama Society. He also, declares John Bowman admiringly, somehow managed to fit in voluntary art classes as well.

Awed classmates likened him to a budding combination of Einstein and Michelangelo, but Day shunned the adulation. ‘He had blond hair and fair skin, which blushed in pink blotches’ recalls Wolff.

Like his Uncle Clarence and brother Michael, John Day played the violin. His cultural interests were fostered by his grandmother Frances Hamblin. ‘She and John loved each other so much’ sighed Josephine Day. ‘When she died he was very depressed.’

That was in 1948. Next Spring, around the time John completed his time at Malden High, his mother rented him a one-room studio in Rockport on Cape Ann – one of several longestablished Art colonies along the New England coast, from Camden and Kennebunckport up in Maine down to Provincetown in Cape Cod Bay. The aim was for John to spend time pursuing his artistic apprenticeship among people of professional standing.

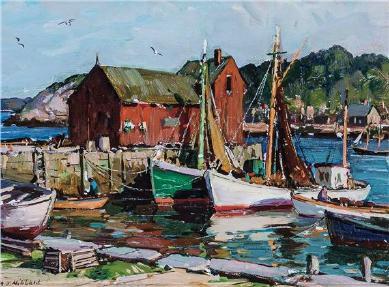

Pretty Rockport was renowned for its 1840s harbour fishing shack, reputedly the most painted building in the United States – dubbed Motif N° 1 by local art teacher Lester Hornby. Its distinctive ‘Pompeiian Red’ paintwork had been applied in 1942 by Association President Aldro Hibbard (author of the sun-dappled view left).

Rockport was just 35 miles from Malden and one day in June 1949, soon after passing his drivingtest, John invited his friends John Bowman and Kempton Webb to join him there. ‘We enjoyed the hour-long trip and checked out the people and they place’ recalls Webb.

Back in Malden Day had transformed a room in his home into an artist’s studio where, remembers John Bowman, ‘he introduced me to his favourite background music, French Baroque: Lully, Charpentier, Couperin, Rameau… I joined him on several local painting expeditions. He insisted on setting me up with my own easel, but I had no talent despite his kind words.’

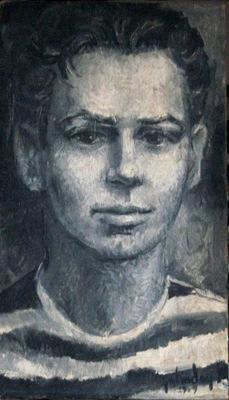

One day John’s mother Josephine asked Kempton Webb if he would be willing to pose as a model for John in his home studio. ‘It was a new experience’ admitted Webb, writing over seventy years later. ‘I simply sat in regular clothes (khaki pants and red sweater). I sat still for maybe an hour a day, for five or six days. I knew nothing about art. We just jabbered away.’

Mission accomplished, ‘John signed the portrait and gave it to me’ adds Webb. ‘It now hangs in the Vermont home of my son, Scott Webb.’

While Kempton’s khaki pants didn’t make it on to the canvas, it’s tempting to think the red sweater was a subconscious homage to the Rockport shack.

It is poignant to note that the ‘shack red’ of Day’s earliest surviving painting would dominate the palette of his final Infanta and Pompeiian series three decades later.

Day spent the academic year 1949/50 at the Syracuse School of Art in upstate New York. In Autumn 1950 he abruptly transferred to Yale University in New Haven to study under Bauhaus legend Josef Albers (1888-1976).

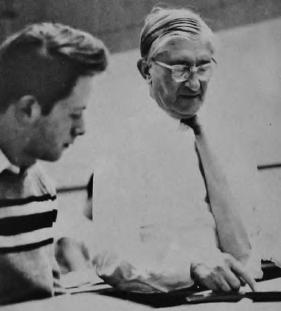

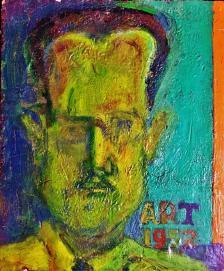

Albers had fled Nazi Germany in 1933, and spent the previous 16 years at Black Mountain College in North Carolina – where his pupils included Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg. It is not known if anyone pulled strings for the 18 year-old Day’s audacious move from Syracuse to Yale – but he was clearly an artist of rapidly evolving accomplishment, as evidenced by his 1951 portrait of his father Kenneth (left). Day and Albers are shown together below right. John Day would be the youngest pupil in Albers’ class at Yale, where he was assisted by Bernard Chaet (1924-2012).

Day lived on Edgewood Avenue in New Haven, a mere 300 yards from the Yale Art School on Crown Street. In both 1951 and 1952 he spent the month of August back in Rockport – winning the Young Members’ Prize from the Rockport Art Association two years running, and portraying the harbour’s iconic shack ‘over and over’ (as he confided to journalist Judith Priestley in 1960).

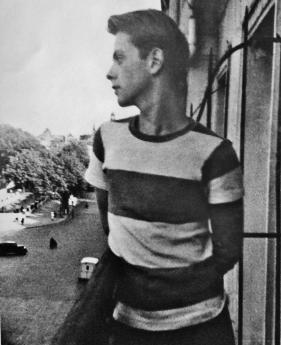

In August 1953 John Bowman stayed with Day in the spacious apartment he was sharing in central Paris with Theo Stavropoulos (1930-2007), a young Greek artist (left) who studied with Fernand Léger and at the Paris Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and would exhibit at the 1953 Salon d’Automne and the 1954 Salon du Printemps. Day (shown on his balcony, right), ‘dragged me all around Paris, introducing me to everything from obscure church chapels to onion soup at midnight in Les Halles’ recalls Bowman. The two later went to Rome where Day ‘was tireless in taking me around to view every notable painting or sculpture in the most obscure side-chapel.’ On later trips to Europe, Day – who claimed to speak ‘French as well as English, Italian well and German fairly’ – would work as a tour guide.

John Day’s parents left Malden when their younger son Michael (an accomplished violinist) headed to Harvard after leaving school. They moved south to Waterford, a seaside town 40 miles east of New Haven, where they had a new house built by local architects Scholfield Lindsay & Liebig – with John Day referenced as ‘design collaborator’ on a sketch he produced himself (above left). The bungalow still stands (above right).

During the 1950s, recalls John Bowman, Day ‘would go off to Europe in the company of an older man, an academic’ – the splendidly named Imbrie Buffum (191597, left), a Yale professor specializing in the arts and literature of France during the Baroque period. ‘John was beginning to lead the life of the homosexual he was’ believes Bowman. ‘As this still had to be such a covert existence – and since I was still so naïve – I gave no thought to this side of John. He never once made the slightest move on me.’ Bowman believes that Day’s homosexuality may have helped him ‘somehow escape the draft that scooped up most of our generation.’

After obtaining his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Yale in June 1954, the 22 year-old Day (right) spent a year in France –thanks to scholarships from the French Government and the Alliance Française in New York. He headed to the Mediterranean fishing village of Les Lecques (15 miles west of Toulon), living in a beachside cottage called Les Jumelles with Theo Stavropoulos (who would join Day at Yale in Autumn 1955).

On 13 May 1955, just after attending the opening of a Jacques Villon show at Galerie Louis Carré in Paris, Day penned a letter to Myra Davis, the New York-based Secretary of the Fontainebleau Art School, seeking funding to enable him to attend the school that Summer; he was particularly keen to attend the class in fresco technique. Day had visited the school with Nadia Boulanger (now its Director) in 1953 –and been wowed by the ‘vitality, extraordinary site and unique opportunities’ it offered. His application was made ‘sur la recommendation de Mlle N. Boulanger’ – who had maintained her links with Boston music circles (and, presumably, Day’s mother) as the first woman to conduct the Boston Symphony in 1938 before teaching harmony, counterpoint and composition at the Longy School from 1941-45.

Nadia Boulanger was one of the five references Day listed at the bottom of his CV. The others were his art teachers Josef Albers and Bernard Chaet; Henri Peyre (1901-88), Head of the French Department at Yale; and Imbrie Buffum.

But Day’s application arrived in New York too late. ‘There is no possibility that we can assist you’ replied Mrs Davis tartly on May 20. ‘You have already been most fortunate.’

Day’s letter, however, contained a mine of information about his state of mind. He had chosen to live in a fishing village to ‘be in contact with the unsurpassable French landscape which so aided Cézanne, Van Gogh and a host of great masters to realize their best works’ – and to ‘avoid the influence and assistance of an Art School’ while seeking his ‘personal response and needs in front of Nature’ (the last phrase revealing just how much Day had gone native, being a literal translation of the French devant la nature). He had also wanted to acquaint himself ‘with the Mediterranean temperament, so different in many respects from my own.

‘I feel my decision was a wise one and that I have worked well and learned a great deal, especially in the field of drawing’ he concluded pompously. ‘Although I may often doubt my capacities, I can no longer doubt my serious devotion to art and my need to express myself though creative action.’

That said, Day now felt an ‘urgent need to associate myself with a school with French thought in the field of art and art education, and with other young people having concerns similar to mine.’

Day does not appear to have taken Myra Davis’s brush-off lying down: he would later claim to have obtained a scholarship to Fontainebleau thanks to the intervention of Nadia Boulanger – with whom he was still in contact in 1962, when she thanked him for her portrait (‘I know no one more loyal or generous than you’ she wrote).

Back at Yale in 1955/6, when Day completed his Master’s course, Josef Albers was variously assisted by the American abstract artists James Brooks (1906-92), Burgoyne Diller (1906-65) and Conrad Marca-Relli (1913-2000). Diller pursued a rigidly geometric approach à la Mondrian; Brooks (a close friend of Jackson Pollock’s) and the Boston-born Marca-Relli (who often worked with collage) were Abstract Expressionists. All three seem to have had some influence on Day’s stylistic development.

Day was the youngest of 14 students to earn an MFA at Yale in June 1956. The oldest was war veteran Homer Mitchell (1919-2011), the most exotic Polish-born Julian Stanczak (1928-2017) – who had fallen under the geometric spell of zebras and African textiles during the six years he spent in a Uganda refugee camp, where he taught himself to paint left-handed (his right arm having been smashed during his boyhood exile to the Soviet Union).

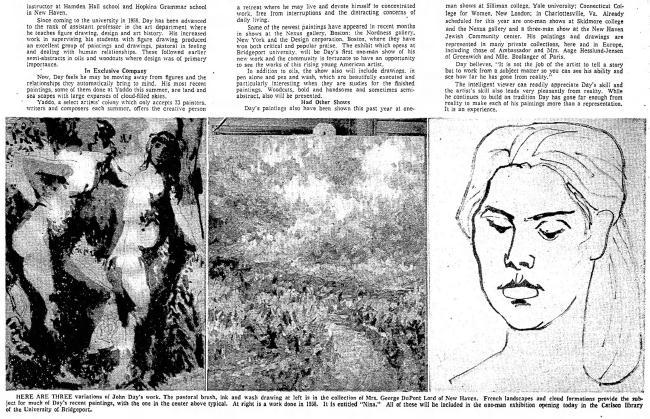

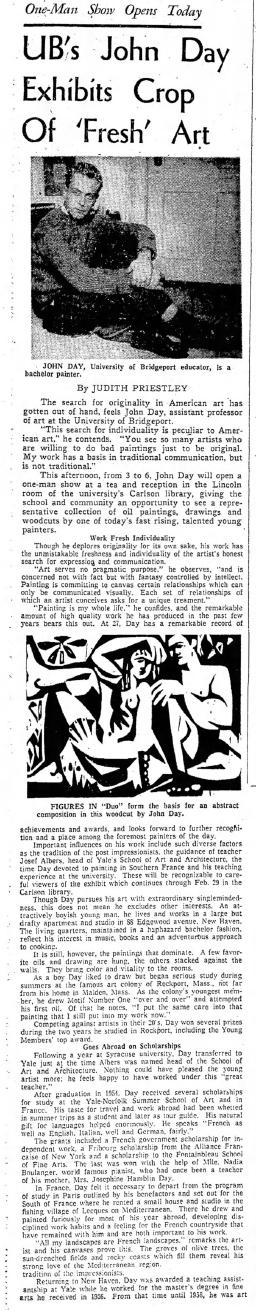

From Autumn 1956 Day taught on the outskirts of New Haven, at Hamden Hall and at Hopkins School – which he joined at the same time as another Yale alumnus, music teacher (and confirmed bachelor) Herbert Richmann (1926-2006) – for whom Day produced the concert poster shown right. In 1958 Day began teaching Drawing, Design & Art History at the University of Bridgeport, 20 miles to the west. In 1959 he took part in the exhibition Why is Color So Exciting? at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, and joined the nearby Yaddo artists’ retreat – painting landscapes shown at Nordness Gallery, New York, and Nexus Gallery in Boston. His solo show of paintings, drawings and woodcuts in Bridgeport University’s Carlton Library in February 1960 exuded ‘unmistakable freshness and individuality’ declared Judith Priestley in the Bridgeport Post. She called Day ‘one of today’s fast-rising young painters’ who ‘has gone far enough from reality to make each of his paintings more than a representation. It is an experience.’

‘My work has a basis in traditional communication, but is not traditional’ Day told her. ‘Painting is my whole life.’ Priestley felt that he ‘pursues his art with extraordinary singlemindedness and looks forward to a place among the foremost artists of the day.’ He was an ‘attractively boyish young man’ whose ‘large but draughty’ New Haven flat, ‘maintained in haphazard fashion, with pictures stacked against the walls, reflects his interest in music, books and an adventurous approach to cooking.’

JOHN DAY PICTURES FROM THE 1950s

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

1 Portrait – pencil (1954)

2 Flat in Paris – pastel (c.1955)

3 Color Study – pastel (1959)

4 Cubist Landscape (1956)

5 Colored Landscape – pastel (1959)

6 Abstract Landscape (1959)

7 Bayscape (1960)

8 Sue van Vorst (c.1960)

9 Boy’s Portrait (1959)

10 Two Faces – woodcut (c.1956)

An eclectic approach to subject-matter and materials characterized Day’s art of the 1950s.

Early owners of his works included Nadia Boulanger and Aage Hessellund-Jensen, Danish Ambassador to the United Nations in New York.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

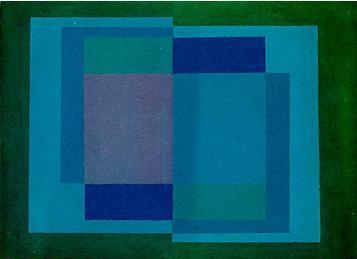

1 Josef Albers: Into the Open (1952)

2 Julian Stanczak: With Respect to Albers (1957)

3 Richard Anuszkiewicz: Radiant Green (1965)

4 Irwin Rubin: Construction #21 (1961)

5 Bernard Chaet: Self-Portrait (1952)

6 James Brooks: B-1955 (1955)

7 Conrad Marca-Relli: Battle (1956)

8 Lois Swirnoff: One, Two & Many (1985)

9 Burgoyne Diller: N° 2 – First Theme (c.1956)

Julian Stanczak pursued abstraction as a way to forget ‘the atrocities of World War II through nonreferential art.’ He studied in London for two years under the great Vorticist (and fellow-Pole) David Bomberg before – like Richard Anuszkiewicz (19302020), also of Polish origin – attending the Cleveland Institute of Art prior to Yale. The term Op Art was coined at Stanczak’s show with New York’s Martha Jackson Gallery in 1964. Irwin Rubin (1930-2006), Victor Liguori (1931-2018) and Lois Swirnoff (born 1931 and the last of Day’s Yale class-mates still alive) all hailed from New York, where Rubin and Swirnoff attended the Cooper Union School of Art. Swirnmoff and Liguori both later taught at Skidmore College.

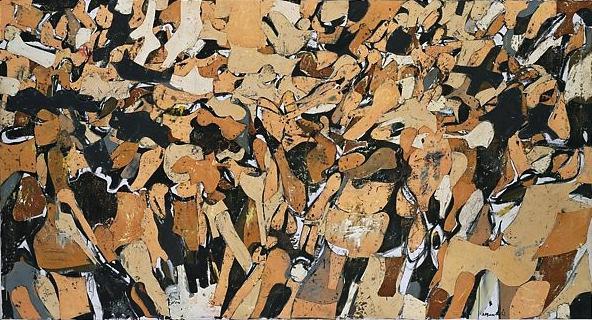

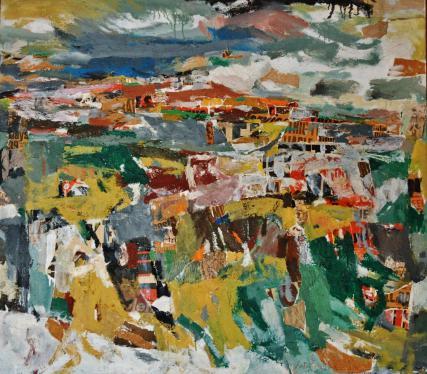

John Day was promoted to Assistant Professor at Bridgeport in 1960, confirming him as a permanent member of staff. His work over the next three years was dominated by collage, with Day (according to his later assistant Robert Napolitano) afflicted by ‘painter’s block.’ In 1961 he produced a series of large, torn-paper Billboard Landscapes (below left) inspired by the ‘lacerated poster’ approach of Jacques Villeglé and Raymond Hains from the Nouveaux Réalistes (a term coined by French art critic Pierre Restany the year before).

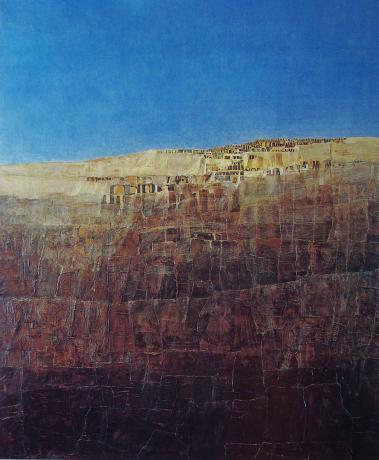

Some 1962 leaf collages nodded to Josef Albers, albeit with newsprint and magazine cuttings vying for attention. One collage, incorporating male/female nudes and pornographic imagery (above right), would remain in Day’s possession until his death. A 1962 collage entitled View of the Plain (below right) escaped abstraction with a patch of sky painted in a deep blue that nodded towards another French artist, Yves Klein, who died that year. This blue would recur in Day’s work for several years – invariably associated with the skies of Greece, whose scenery and mythology would come to haunt him. He also adopted the blue for gallery posters (below centre).

It was his friend Theo Stavroupolos who introduced Day to Greece and its history. Stavropoulos, like Day, taught at Bridgeport in the early 1960s, and the two had a jointshow at the Simonne Stern Gallery in New Orleans in 1967.

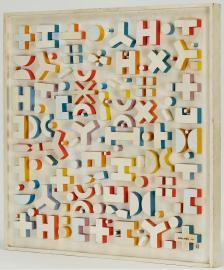

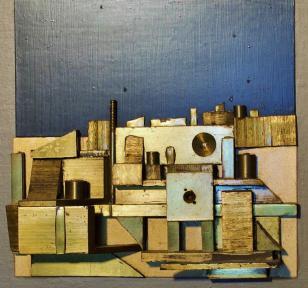

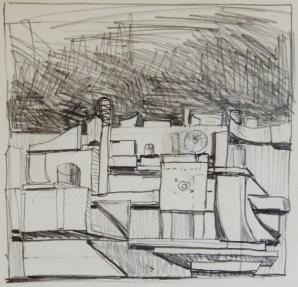

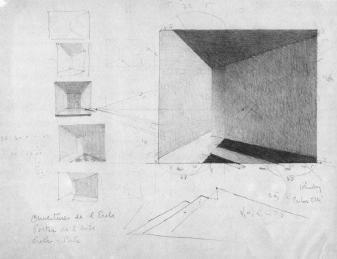

Day’s ingenious reliefs, rarely more than 30cm square, created cityscapes from everyday materials. As the sketch above centre reveals, they were painstakingly prepared with nothing left to compositional chance.

Day also produced cityscapes in lighter relief that looked more like paintings (see below) These would often incorporate newsprint and lettering – after Day came across a typesetter’s cabinet in a thrift store.

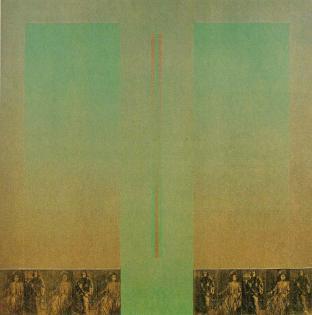

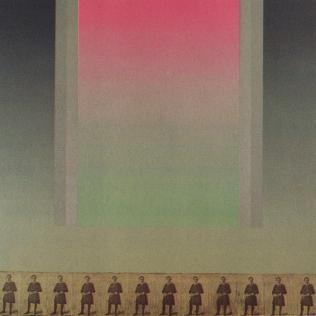

Another chance discovery would have an even more profound effect on Day’s art: that of a scrapbook full of turn-of-the-century photographs of Vaudeville artistes. Day removed the images and incorporated them into his pictures, smearing them with a darkish glaze that rendered them semi-indistinguishable. Among the earliest examples are the day and night Views of Erebos shown on the following page, where the photographs form the rocky foreground beneath a newsprint hilltop.

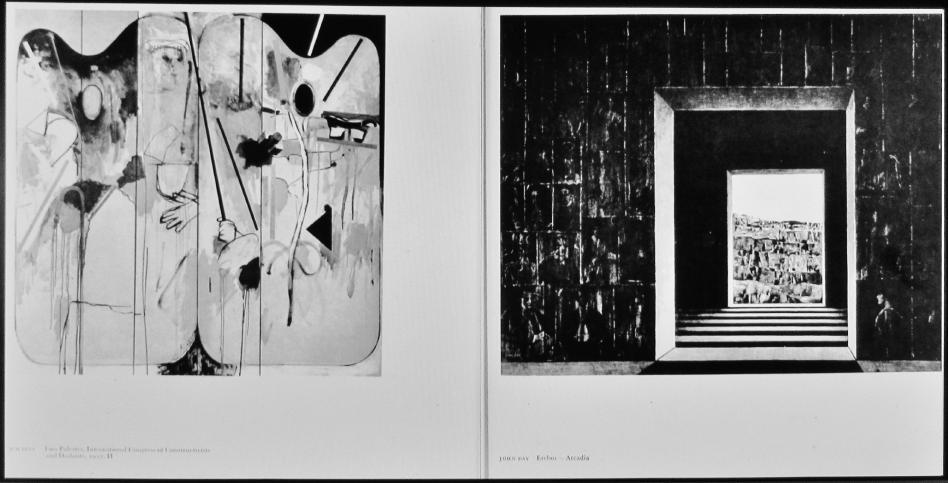

One of these innovative landscapes would enter the New York MoMA and be displayed at its Recent Acquisitions show in 1966 (below). Other works by John Day were acquired by New York’s Metropolitan, Whitney and Guggenheim Museums, by the National Museum of American Art in Washington D.C., and by the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

In 1963 John Day moved from New Haven to New York, renting an apartment-cum-studio on East 89th Street. This new den was in no ordinary block, but on the top floor of the eclectic Graham House, built in 1892 from ‘Pompeian Red’ brick with an ebullient doorway in Indiana limestone. Not only was the sevenstorey building spectacular, it was located just around the corner from the Guggenheim Museum, opened four years before. (Since 2011 the Graham House has been occupied by St David’s School, founded next door in 1951; John F. Kennedy Jr was a pupil in the mid-1960s.)

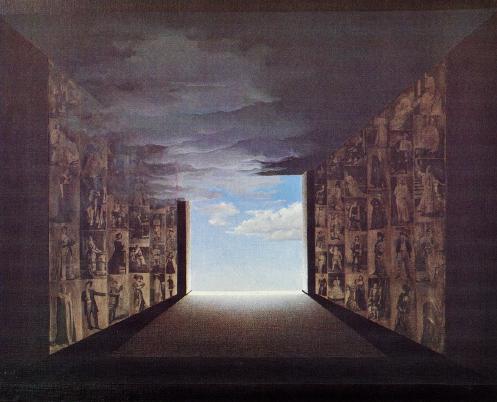

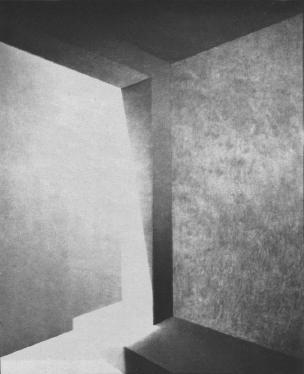

‘Painter’s block’ was banished by Day’s move to his new studio, where his Erebos series swiftly took shape. Erebos was the Ancient Greek purgatory – a land of darkness that the souls of the dead were forced to pass through to reach Elysium.

Sharply receding Last Supper-like perspective; walls lined with images of the dead, recalling the embalmed monks lodged in the walls of Kiev’s Percherska Lavra; and a glimpse of light (or sometimes darkness) at – so to speak – the end of the tunnel were all characteristic of Day’s unprecedented works. To modern eyes they share the vision and precision of the Russian artists Oleg Vasiliev and Eric Bulatov (born respectively the year before and after John Day).

The picture shown right, known as Clouds Entering and dating from 1965, has been likened to Dali or Magritte. Day’s taste for Surrealism was reflected by a ditty he taught Ruth Wolff, concocted by the French Dada poet Robert Desnos:

Une fourmi de dix-huit mètres avec un chapeau sur la tête ça n’existe pas, ça n’existe pas (roughly: ‘there’s no such thing as a 50-foot ant with a hat on its head’)

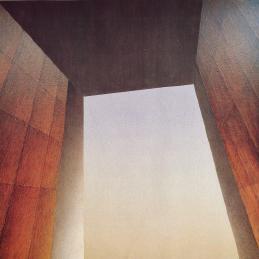

EREBOS ELLE (1971)

ABOVE DAY’S PENCILLED SHEET OF ADVANCE PLANNING RIGHT

EREBOS PORTAL (1970)

SEEMS TO PRESAGE THE GRANDE ARCHE DE LA DEFENSE NEAR PARIS (1989)

Helen Harrison, in the New York Times, found that Day ‘focuses on the juncture of darkness and light, confinement and release. Sometimes collaged with pages from 19th century ledgers or images from an old souvenir album, these works – populated only by shades and dreams – are almost surreal in their other-worldly emptiness.’

In his February 1964 review of Day’s Gates of Erebos exhibition at the East Hampton Gallery on West 56th Street, Brian O’Doherty dubbed these pictures ‘crypt landscapes’ in a ‘marvelous show’ that ‘brings you right through to the world of shades and spirits.’

Day’s works reminded O’Doherty of Joyce’s The Dead, their walls ‘lined with Edwardian shadows (old photographs of the Eleonora Duse type)… one glides through a tunnel of these figures, benighted in dark glazes’ (Eleonora Duse was a bisexual Italian actress of the Belle Epoque – and the first woman ever to grace the cover of Time magazine).

Lillian Lonngren of Art News called Day ‘morbid –delightfully morbid! He brings something new to Surrealism.’

To Gordon Brown, in Art Magazine, Day’s ‘deathly quiet corridors recall Dante’s per me si va tra la perduta gente’ (‘through me, the way that runs among the lost’).

THIS CIRCULAR WORK BY SERGEI SHABAVIN – A SLIGHTLY YOUNGER COLLEAGUE OF ERIK BULATOV AND OLEG VASILIEV –HAS A GEOMETRY AND PRECISION PERSPECTIVE REMINSCENT OF (IF NOT INDEBTED TO) JOHN DAY’S EREBOS VISA (1965)

Brown extolled Day’s ‘exact, classical sense of perspective.’ His corridors leading to or from Hell were ‘mounted with shadowy portraits of vaguely remembered individuals, strangely still and as drained of life.’

Day’s Erebos Arcadia was featured in the Whitney Museum’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting that ran 8 December 1965 – 30 January 1966. It appeared in the catalogue as n° 24 (see below) next to De Kooning’s Two Palettes. The show also featured Josef Albers and other front-line abstractionists (Joel Barletta, Richard Diebenkorn, Ellsworth Kelly, Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, Robert Motherwell, Deborah Remington, Frank Stella). Other big-name participants included Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Joan Mitchell, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Wayne Thiebaud, Mark Tobey and Tom Wesselmann.

In the early 1970s Day abandoned his three-dimensional approach to Erebos in favour of frontal settings with collaged figures running horizontally along the bottom of the canvas. Day was now teaching at William Paterson College in Wayne, New Jersey, where one of his pupils was Robin Schwartz (left), today a Guggenheim Fellow in Photography. She spent the academic year 1976/7 in John Day’s class studying Colour Theory.

‘Day – we called teachers by their last name – taught me how to think, add and subtract in colour, to see tight nuances’ she says. ‘He was serious about teaching colour theory. His Josef Albers colour aid assignment gave me a foundation in all things colour.’

‘John Day was greatly influenced by and, I would say, almost worshipped Albers’ remembers Bill Finneran, who was head of the Arts Department at Paterson College. ‘In Day’s teaching and his own work, Albers was The Man – any other notion about art was not of great interest to him.’

‘John Day was a very good teacher – nice and precise, serious and calm, extremely wellorganized, neat as a pin’ adds Schwartz. ‘He didn’t skimp. I liked that. He knew his thing. Nothing about him was haphazard.’ Robert Napolitano – who would became Day’s fulltime studio assistant in 1979 – was also in Day’s class, although he was three years older than Schwartz. She remembers him as ‘very pretty, and kinda superior – he wasn’t nice.’

Schwartz heard about John Day’s death in 1982 when she was working for Burt Glinn (1925-2008), President of Magnum Photos. Glinn had a ‘floor-to-ceiling painting by Day with Grecian figures at the bottom. It was wonderful.’

Gregory Battcock (right) taught Schwartz art history. ‘He liked to joke around. He could hold an audience. I found him fascinating. John Day always wore coloured crew-neck sweaters, but Battcock sported snappy European suits. He liked to go to Riverside Park where the gays hung out.’

A former editor of Arts Magazine, Battcock was a contributor to Gay and The New York Review of Sex and Politics – a flamboyant figure who once dressed up as a ticket inspector and strode through Grand Central Station punching whatever papers he found under people’s arms. As an art-gossip columnist he enjoyed satirizing members of New York’s art community. Battcock died before John Day – and younger: stabbed to death on the balcony of his San Juan holiday flat by his Puerto Rican ‘houseboy’ in 1980, aged 43.

‘I did not realize how lucky I was to be instructed by the art faculty at William Paterson’ states Schwartz. ‘David Haxton, Gregory Battcock, Al Loving – wild, completely out of the box – and John Day: these people put William Paterson College on the map.’ (John Day’s Malden schoolfriend Kempton Webb was also at Paterson, teaching Geography.)

Day was also gaining a reputation further afield – in his beloved France. After two solo shows in 1969 and 1972, at the Rive Gauche gallery in Paris run by former U.S. Cultural Attachée Darthea Speyer, Day’s large painting Erebos au Portail was acquired by Marseille’s Musée Cantini. In 1977 it joined works by a roster of international superstars (Francis Bacon, Christo, Jim Dine, Sam Francis, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Yves Klein, Sol LeWitt, Kenneth Noland, Judit Reigl, Frank Stella, Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann) in the blockbuster exhibition L’Avant-Garde 1960-1976 that travelled from Marseille to Grenoble and St-Etienne before ending up in the newly-opened Pompidou Centre. Day’s work (see above) was reproduced in the 200-page black-and-white catalogue.

John Bowman recalls helping Day hang his works in a New York gallery – he demanded ‘absolute exactitude when it came to where each painting was to hang.’ Bowman does ‘not recall seeing any sign of John’s being devoted to Albers’ theories at this time,’ but that was about to change. In 1977 Day returned to the leaf collages that Albers had asked his students to make at Yale in the 1950s – inspired by his own similar works of a decade before. It heralded the transition to the final phase in Day’s stylistic development, when he at last returned to the precepts of his former teacher.

Day was also active in other spheres, frequenting what Bowman terms New York’s ‘notorious Baths – private clubs with Turkish baths, with the main purpose of inviting fellow homosexuals to lounge naked then enjoy sexual encounters. This was before the AIDS virus – but, even so, many people found these Baths scandalous.

‘On another occasion my wife and I spent a weekend with John at a summer rental on Fire Island – a popular destination for homosexuals’ (in 1974 a prospering Day would acquire a farmhouse in nearby Bridgehampton, Long Island, then sprout a Village People moustache). ‘John now had a highly active sex life, although he never carried on as some flamboyant bohemian or flagrant queer. The John Day I knew remained true to his Malden self.’

Ruth Wolff found Day ‘a good deal more liberated than the rest of us Maldonians’ when her family moved to Upper East 89th Street in the 1970s – a stone’s throw from Day’s ‘top floor apartment with tall arched windows that let in a lot of northern light.’ John and her husband Martin ‘would have endless earnest talks about art. There was even a time when, as an experiment, John executed a painting illustrating some theory Martin had.’

The Wolffs were regular guests at the parties Day hosted. ‘He had lots of friends. I particularly remember one party where, at a long table, John served the longest meatloaf I ever remember’ (echoes here of his ‘adventurous approach to cooking’ remarked on by the Bridgeport Post in 1960). Ruth Wolff found herself sitting next to U.S. Navy Secretary John Warner who, at the time, was married to the daughter of the art collector Paul Mellon. ‘How did John Day know John Warner?’ she mused. ‘Who knows? He knew many people. He had blossomed.’ In cosmopolitan New York, he ‘was able to become what he was.’

Theo Stavropoulos also spent a lot of time in John Day’s apartment, recalls his daughter Dominique. Day was close to all her family, and jokingly referred to Dominique as his ‘favourite girlfriend’ (though not his homecoming queen). She called him Uncle Johnny. ‘He and my father were like an old married couple’ she says. ‘Two brilliant, intense and arrogant artists – it’s easy to understand why they clashed. I witnessed a heck of a lot of bickering.’

John Day and Theo’s wife Susan ‘adored each other as well’ and ‘used to go to the Metropolitan Opera together a lot.’

Dominique also encountered Day’s notoriously enthusiastic approach to money.

‘Johnny once offered to sell me a painting that I fell in love with as a teenager’ she remembers. ‘He asked $500 for it – he always had a sharp business mind! I was taken aback. I was pretty young and never thought that I could ever come up with $500. In retrospect I believe he would have given me time to pay it off. I wish I had taken him up on the offer. I think of the painting to this day.’

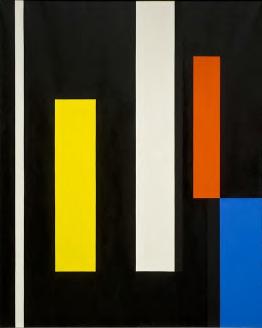

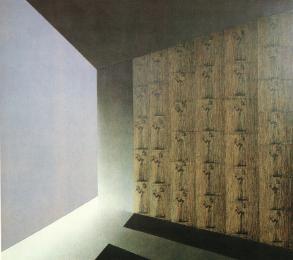

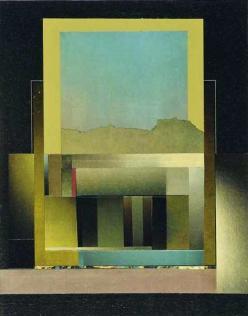

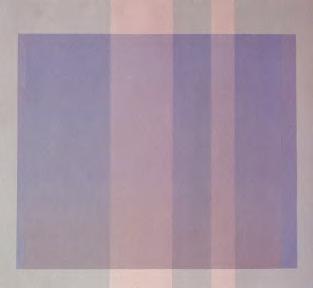

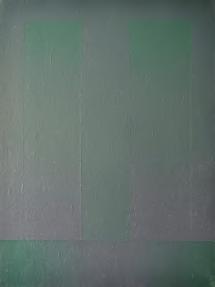

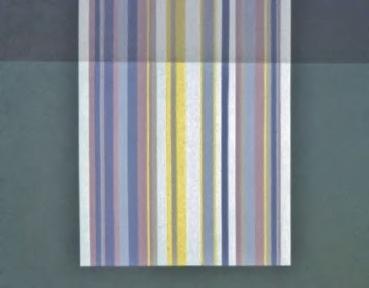

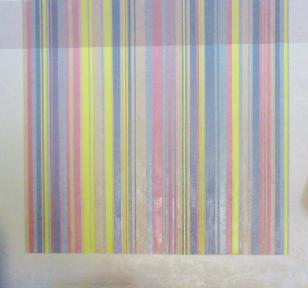

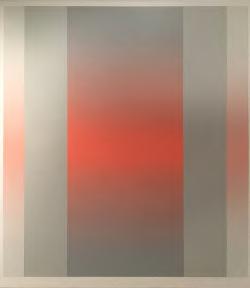

1979 – PAINTED ABSTRACTION – 1982

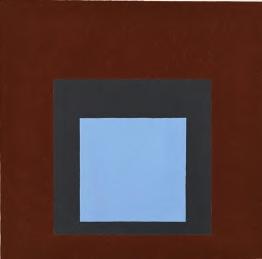

Two works entitled Southern Summer marked John Day’s transition to the pure, painterly abstraction – without recourse to collage – that characterized his prolific last three years. Some, but not all, of the paintings he produced at this time were assigned to two series: Infanta, inspired by Velasquez; and Pompeiian, inspired by ancient frescos (and also, perhaps by the ‘Pompeiian Red’ brick of Day’s New York apartment). Some of the Pompeiian works were further subtitled Sarabande in honour of a Spanish dance popular in the Baroque France of Louis XIV that Day held dear.

Both series employed colour-field painting to express the mood evoked by the original works. Both exude the spiritual intensity of a Rothko – albeit it in quieter tones. ‘My aim is to paint paintings so quiet you can hear a pin drop’ explained Day. He now felt his previous works ‘too busy. They’re Berlioz. I want to be Bach.’

There was musical structure to his chromatic approach. As his final assistant, Robert Napolitano, would later explain, Day used a family of colours based on mathematical sequences, with two parent colours (numbered 1 and 9) at the end of the scale, and a middle fifth colour created by mixing various amounts of the parent colours together in the same daylight. Day mixed his colours carefully with a palette knife on glass. They were then sealed in plastic and number-coded for later use.

Day listened to classical music while he painted – principally Bach, Monteverdi, Mozart and Verdi. Perhaps his love of Monteverdi was inspired by Nadia Boulanger – who, in 1937, recorded Monteverdi’s madrigals for HMV and conducted his music with London’s Royal Philharmonic… prompting the critic Auguste Mangeot to write, in terms echoing Day’s talk of ‘hearing a pin drop’:

She never uses a dynamic level louder than mezzo forte and she takes pleasure in veiled, murmuring sonorities, from which she nevertheless obtains great power of expression. She arranges her dynamic levels so as never to have need of fortissimo.

To David Shirey, writing in the New York Times on 28 June 1981 (about an exhibition at the Louise Himelfarb Gallery in Water Mill, Long Island), ‘John Day has a penchant for pictorial paradoxes, but he is an abstractionist who combines a quiet voluptuousness of color and light with a stern geometric structure.

‘While we are aware in these fascinating works of the freedom and imaginative subtleties suggested in the colors and the lyrical light,’ continued Shirey, ‘we are also conscious that these effects are kept in check by the structural severity Day has imposed upon them. There seems to be a tranquil push and pull between the actual surfaces of the works and their intimations of depth, a kind of mathematical certainty about them pitted against a metaphysical and spiritual ambiguity.’

Such was the importance that Day attached to the pinpoint planning of his compositions that, when his work was exhibited in the Ben Shahn Hall at William Paterson College in January 1980, the accompanying poster (right) featured his preparatory sketches and annotations rather than a finished artwork.

The last show to feature John Day during his lifetime was held at the Montclair Art Museum. It charted Josef Albers’ career as painter and teacher, with a selection of works by his pupils. It closed on 17 January 1982. Three months later Day was dead.

When Theo Stavropoulos found out that Day was seriously ill in the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, recalls his daughter Dominique, ‘he went to see him every day until he died.’ The two men had fallen out in the late 1970s, and stopped speaking to each other. ‘It was a great relief that they could at least reconcile. My father never got over John’s death.’

To Ruth Wolff, John Day left behind a body of work that embodied ‘luxe, calme et volupté

as in the Baudelaire poem John taught me long ago.’

To John Bowman, John Day was ‘a true enjoyer of his existence, and dedicated to his painting. Gentle and generous as a human being, focused and intense as an artist.’

A memorial gathering in Day’s New York apartment was organized by his assistant Napolitano, his brother Michael and his mother Josephine, now in her late seventies. She greeted Bowman as an old friend.

‘At one point we stepped aside’ he relates. ‘She confirmed that there was no identified cause of death – only that his immune system had collapsed.’

1982 – POSTHUMOUS – 2020

‘A few weeks later I was in my kitchen listening to the early morning news on our public radio station’ continues Bowman. ‘There was this report of a disease that was rampant in the homosexual communities of New York and the San Francisco Bay area. Its major symptom was the collapse of the immune system due to a virus called HIV.’

On 11 May 1982, less than four weeks after John Day’s death, the New York Times reported on a New Homosexual Disorder ‘known to doctors for less than a year’ and which was ‘worrying health officials.’ According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the number of American victims then stood at 136 – the majority in New York. Federal health officials were concerned that tens of thousands more male homosexuals might be silently affected. By 2020, over 700,000 had died of AIDS in the U.S.

Back in May 1982 the term AIDS (Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome) had not even been coined. The disease was likened to a rare type of cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma; journalists referred to ‘gay cancer’; some researchers talked of GRID (Gay-Related Immuno-Deficiency). The CDC informed a Congressional Hearing that GRID was ‘a matter of urgent public health and scientific importance.’ Most cases occurred among homosexual men ‘who have had numerous sexual partners – often anonymous partners whose identity remains unknown.’ The CDC estimated the average number of sexual partners for affected homosexuals at over 1,150, adding: ‘Gay people whose lifestyle consists of anonymous sexual encounters are going to have to do some serious rethinking.’

Andy Warhol was ‘worried I could get it by drinking out of the same glass, or just being around these kids who go to the Baths.’ In 1984 his boyfriend Jon Gould was admitted to hospital with pneumonia; he died in September 1986 from AIDS, aged of 33. Alexander Iolas, the gallerist who gave Warhol both his first exhibition (in New York in 1952) and his last (Il Cenacolo in Milan in 1986), died of AIDS in June 1987. Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe were other high-profile artworld victims. Showbiz lost Liberace, Freddie Mercury and many more.

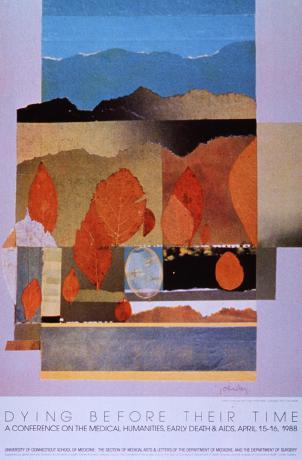

In April 1988 the University of Connecticut hosted a conference entitled Dying Before Their Time to discuss ‘the medical humanities, early death & AIDS.’ A John Day leaf collage served as its elegiac poster.

John Day left his artworks to Robert Napolitano. Posthumous shows of his work were held at the Guild Hall (East Hampton) in 1983; at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum (New London) and Montclair Art Museum (New Jersey) in 1984; then (together with the recently deceased British artist Haydn Stubbing) at the Elaine Benson Gallery, Bridgehampton, in May/June 1985.

Helen Harrison reported on that show for the New York Times , calling Day ‘a colorist of great skill and subtlety’ and noting that ‘while his earlier work shows little influence of his teacher, the later canvases draw progressively on Albers’ lessons, yet achieve a personal dimension.’ Day had ‘progressively discarded all references to human presence and illusionistic space, until his canvases came to radiate with the rhythmic interaction of geometrically organized colour areas. These pieces, often in glowing reds that modulate into warm greys, pulse with an inner vibrancy that belies their strict formality.’ They had ‘softly modulated tones inside hard-edged rectangles, setting up a visual tension that enhances their liveliness.’

Day, concluded Harrison, seemed to have ‘reached a major plateau of development – but he was only 50 years old and had by no means achieved the maximum of which he was capable.’

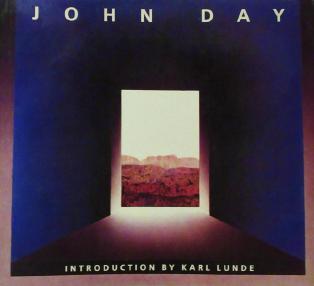

A 96-page book on John Day was published by Tenth Avenue Editions (New York) in 1984. It contained 45 coloured reproductions plus an overview of John Day’s work by his colleague Karl Lunde (1931-2009), Professor of Art History at Walter Paterson College (and the partner of artist and arts administrator Roy Moyer).

Lunde (right) believed that Day had ‘come to identify himself in his last paintings with pure light. Interior and exterior have become identical. It is painting as self-portraiture in its ultimate form: a union of himself with his art, a sublimation of his personality to its own image.’

The book also featured articles by Robert Napolitano and the New York art critic Amei Wallach (right). Day, she wrote, ‘was never the sort of painter it is easy to categorize. He was not Pop, or Minimal, or Expressionist. In the last years, perhaps, if one wanted to oversimplify, one could call him a Color Field painter. But color was only one of his concerns. He was a painter of enormous subtlety and intelligence. He wanted to tackle the large subjects. Like eternity. Like mythology. Like purity.’

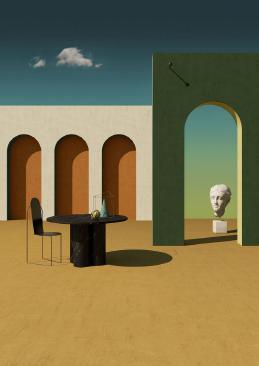

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO

PAUL DELVAUX

RENE MAGRITTE

LEONARDO DA VINCI

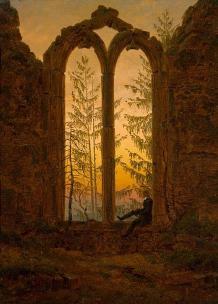

CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH

OTTO FREUNDLICH

OLEG VASILIEV

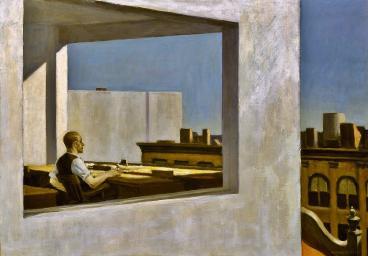

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP RIGHT :

HYDE SOLOMON

ESTEBAN VICENTE

JOSEF ALBERS

EDWARD HOPPER

THEO STAVROPOULOS

MARK ROTHKO

AD REINHARDT

JULIAN STANCZAK

In 1985 Day’s close friend Guy Cooper, a Cambridge law graduate who became International Marketing Executive for Unilever, purchased his artistic estate from Napolitano for around $200,000. Cooper kept a limited number of works for private enjoyment, placing the rest in storage with Scanio in New Jersey. They have not been displayed since.

The last time a work by John Day was shown in public was in June 1990 – in Setauket, Long Island, when Gallery North (left) selected him among the 25 artists to have marked the Gallery’s first 25 years. Erebos Gemini 1821 was shown: ‘a fine example of an important series by the late John Day… Using pages from an old ledger as an echo from the past, Mr Day leads us into the dark passage by which the soul travels to the underworld, where the twin realms of past and present are one.’

Robert Napolitano resurfaced in the artworld for the last time at Gallery North in 1991, in a group exhibition called Abstractions, where his ‘planar wall reliefs made of gator board…reinterpreted crystalline forms in artistic terms.’

Day’s Yale contemporaries met mixed fortunes. Richard Anuszkiewicz was shown at the 1986 Venice Biennale but, after the Martha Jackson Gallery closed in 1979, Julian Stanczak’s next New York solo show was not until 2004 – even though the New York Times thought his work had ‘steadily become more refined and ingenious’ (words that could equally have applied to John Day). The New York gallery representing Theo Stavropoulos closed in 1980. Thereafter he made artworks in private, his studio only open to family and friends until the posthumous show Offerings of Light at Lehman College Art Gallery in the Bronx in 2013 introduced his work to a new generation (with a catalogue introduction by Amei Wallach). John Day, it should be noted, never had an exclusive gallery to promote his work.

In 2019 a Frank Stella mural was erected behind Malden High School to help students ‘become aware of modern and abstract act.’ Although Stella was born in Malden four years after John Day, in 1936, their artistic paths seldom crossed. Future art historians may marvel that the sophisticated Day should have languished in reputational neglect while the bold, brash Stella enjoyed worldwide fame.

John Day’s onetime colleague at Paterson College, Gregory Battcock, fell into similar oblivion until 2016 when, after his personal archives were discovered by chance, he was

the subject of a biography by Joseph Grigley, Oceans of Love: The Uncontainable Gregory Battcock.

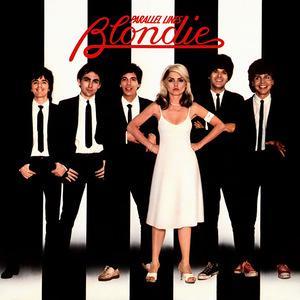

Yet John Day’s memory has lingered in some unsuspected musical ways. The black-andwhite stripes that bedeck Day’s Erebos interiors were immortalized on the sleeve of Blondie’s 1978 album Parallel Lines – a decade after The Monkees’ Daydream Believer had pioneered the colour-field music video. In 1988 a sepulchral Erebos portal loomed centrestage in Luc Besson’s cult video for Serge Gainsbourg’s homosexual reinterpretation of Edith Piaf’s Mon Légionnaire.

John Day’s mother Josephine died in 1995. Mildred Billings, wife of his Uncle Ted, died in 2005, at the ripe old age of 99. Her son Frank Day – pilot, photographer, writer, carpenter – died in 2016 after teaching Chemistry for many years at North Shore Community College in Massachusetts. Since the death of John Day’s brother Michael, in 2017, Frank’s son Peter – a singer and guitarist from Burlington, Vermont – has been male head of the Day family.

In 2011 Guy Cooper brought John Day’s estate to the spacious flat in London’s West End where he lived with his partner Gordon Taylor – a Berkeley graduate who became Deputy Director of the Globe Theatre (and acquired the lucrative rights to Virginia Woolf’s Orlando). The couple first met in 1973 and made a latterday living as high society gardening consultants, with Terence Conran and Elton John among their clients. They became TV celebrities thanks to their quirky BBC series Curious Gardeners.

Guy Cooper (in pink shirt, left) died in 2015. In February 2020 Iain Brunt, an art consultant who had worked for the Wildenstein family for over twenty years, acquired the John Day collection from Gordon Taylor and had it shipped to his French home near Lake Geneva.

‘When I first saw John Day’s works I was amazed by his handling of texture and colour’ exclaims Brunt (whose clients include the Sultan of Brunei, Ralph Lauren, Elton John, Andrew Lloyd Weber, Sir Denis Mahon and the International Olympic Committee).

‘To me, John Day represents a missing link from an era when some outstanding artists were not recognized by the artworld as they deserved. Perhaps his social life hindered him – homosexuality was very much behind closed doors from the 1950s to ’80s – and, also, a reluctance of the artworld to see outside the box.’

Cooper and Tayor, confides Brunt, ‘lived in a socially frantic homosexual world. They loved art. But the works were put into storage and forgotten about until Guy Cooper’s death, when Gordon Taylor decided to rearrange his affairs and gave me the collection to look after. I have decided to devote myself to this collection. I am amazed by its quality. I want to share these works with the artworld and my friends.’

A selection of 46 works from John Day’s estate will provide A Glimpse of Genius in Geneva (at Studio Art Unlimited) in May 2021 – followed by a show at the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery in Boston (June 2021) and an exhibition of Day’s drawings at Malden Public Library, in his home town, in Autumn 2021.

The esthetically varied, technically stunning art of John Day has yet to be showcased in a Museum retrospective. The rediscovery of his estate offers a chance to right that wrong.

Meine Zeit wird kommen ! declared Gustav Mahler, another creative genius struck down in his prime – dying in 1911, aged 50… just one year older than John Day. Mahler’s final works, like Day’s, attained a serenity that had been a lifetime in the seeking. Like Day the artist, Mahler the composer did not, during his lifetime, enjoy the public acclaim his extraordinary talent deserved and would later attract. His day would come. ONE DAY

WHERE I DIDN’T DIE A THOUSAND TIMES – WHERE I COULD SATISFY THIS LIFE OF MINE ONE DAY

WHERE EVERY HOUR COULD BE A JOY TO ME – AND LIVE MY LIFE THE WAY IT’S MEANT TO BE ONE DAY

WHERE I WOULDN’T FEEL MY SENSES DIE – WHERE NOTHING MADE ME HANG MY HEAD AND CRY ONE DAY

WHERE I COULD SEE MYSELF AS OTHERS CAN – WHERE I COULD FEEL THE STRENGTH OF LOVE AT HAND

O MY SENTIMENTAL FRIEND – YOUR TIME WILL COME AGAIN O N E D A Y

– ULTRAVOX 1983 –