MELBOURNE

Level 11 / 522 Flinders Lane

Melbourne VIC 3000

+61 3 8613 1888

SYDNEY

Level 6 / 46-54 Foster Street

Surry Hills NSW 2010

+61 2 9057 4300

NSW Nominated Architect: Mark Raggatt 11783

BRISBANE

76-84 Brunswick St

Fortitude Valley QLD 4006

+61 7 3522 2340

PERTH

Level 12/109 St Georges

Terrace, Perth WA 6000

+61 8 6243 4718

ADELAIDE

217 Flinders Street

Adelaide SA 5000

+61 8 8423 6410

EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION TEAM

Ian McDougall, Ricky Ricardo, Dan Go, Nessie Frangos

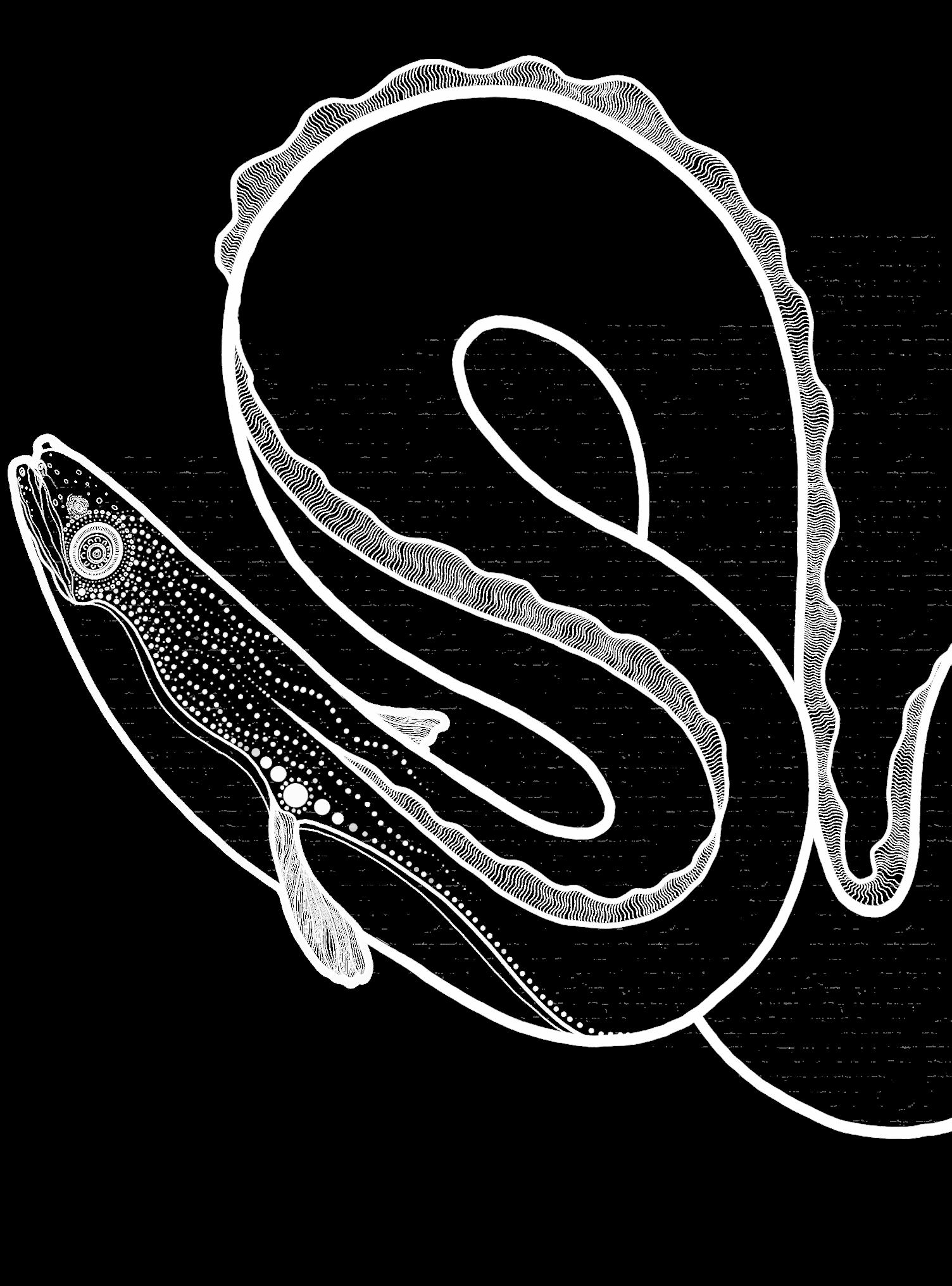

COVER ART

Tarryn Love

PUBLICATION DATE

May 2024

PRINTING Bambra

© ARM Architecture, 2024 armarchitecture.com.au

We at ARM Architecture acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of Country upon which we live and work, throughout Australia.

The Geelong Arts Centre is located on Country of the Wadawurrung peoples of the Kulin Nation.

Our Melbourne workplace is located on Country of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Eastern Kulin nation.

Our Sydney workplace is located on Country of the Gadigal peoples of the Eora nation.

Our Brisbane workplace is located on the Country of the Turrbal peoples.

Our Perth workplace is located on the Country of the Whadjuk Nyoongar peoples.

Our Adelaide workplace is located on Country of the Kaurna peoples.

We at ARM acknowledge all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and we pay our respects to Elders, past, present, and emerging. We recognise and respect their cultural heritage, beliefs, and relationship to the land.

We are committed to our reconciliation journey. We proudly support the Uluru Statement from the Heart and encourage our colleagues and partners to support the Statement.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES ii

INTRODUCTION 2 THE CREATIVE HEART OF THE GEELONG COMMUNITY 4 A GATHERING PLACE 5 DESIGNING GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –CREATIVE PLACES THAT SPEAK OF THE FUTURE 6 EPISODES ALONG THE TRACK 17 PERFORMING ARTS BUILDINGS –TRENDS IN PERFORMANCE SPACES 44 WADAWURRUNG STORIES (TRANSCRIBED ORAL HISTORY) 50 GEELONG ARTS CENTRE – INDIGENOUS ENGAGEMENT 56 MAKING SPACE FOR DIFFERENCE 70 EXPLODING THE BOX — THE FUTURE OF PERFORMING ARTS CENTRE DESIGN 74 PROJECT GALLERY AND DETAILS 78 CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The opening of a new arts facility in any city is cause for celebration. If nothing else, spaces for artistic activity nurture a sense of community through an exchange of fearless and openhearted creativity. Of course, they do more – they are places for us all to gather, to have fun, to share ideas, to provoke discussion. And for those who perform, they are places to show off, to educate, to train, to entertain and to exhibit artists’ speculations through physical, verbal, visual, and musical expression. The completion of the Geelong Arts Centre’s 10+ year revitalisation is not only a moment for celebration but also for reflection.

There has been widespread recognition of the ways COVID has impacted society, and how it has affected the ways we engage with the arts. But there are other significant changes affecting the arts community, such as changes in participation and attendance at performances and changes in the types and methods of creative work. Radical technological change affects our lives dramatically while issues of climate, gender, indigeneity, and social equity and diversity are increasingly challenging us to rethink cultural activity. Changes that were a slow hum in the background have now reached a deafening crescendo; decreasing audience numbers, closing of small arts companies, increasing costs coupled with decreasing government and commercial support. All of these shifts are huge for the makers and consumers of performance art, and so too for those of us who design places for art.

The building of Geelong Arts Centre (GAC) Stage 3 occurs amidst these

changing currents. Discussions within the wider design team, including GAC staff, highlighted new requirements for audiences, communities, and performers. We tried to invent the future, to make the design of the building suit such new demands. But the traditions of theatre and performance run deep and so the design looks both back and forward. The design also occurs at a time when communities are beginning to recognise that they exist in a place that has its own deep roots. Geelong has a significant history as a gathering place, continuously for the Wadawurrung and post the 1836 colonial settlement of Geelong. The GAC site itself is on the edge of a significant former wetland, a place of ritual performance and social gathering for more than 60,000 years. This unique lineage continued as a community place post-settlement, originally occupied by a church, then with a community hall, later a cinema, and then a theatre. The term “glocalization” is pertinent here, understanding that we live amidst global culture but that there is a fundamental need for recognition of the specificity of locality. The design team believed that addressing this tension was necessary through the vision and design of GAC.

This book summarises the making of the Geelong Arts Centre Stage 3, a process infused with ambitions for a new environment for the performing arts. We acknowledge the work completed before us and describe many of the ideas and actions taken to produce this remarkable place.

There are many acknowledgements, but it is important to note that it was the Victorian Government who committed the funding to transform

the former GPAC (stages one, two and three) into the Geelong Arts Centre we see today. It is also important to recognise the excellent project management process by Development Victoria and contractor Lendlease, without whom the project would not have achieved such a high-quality outcome. The present board and staff of GAC, with whom we collaborated, deserve congratulations for successfully creating and realising the project vision—a blueprint for what a performing arts venue should represent for the 21st-century community.

Ian McDougall Co-Founder, ARM Architecture

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 2

THE CREATIVE HEART OF THE GEELONG COMMUNITY

Joel McGuinness Chief Executive Officer & Creative Director Geelong Arts Centre

Joel McGuinness Chief Executive Officer & Creative Director Geelong Arts Centre

The Geelong Arts Centre redevelopment is a testament to collaboration, and it’s been a profound joy and privilege to be at the helm as CEO since 2018. Geelong Arts Centre represents not just a building, but a bold, cultural asset deeply rooted in the heart of Geelong and Victoria. It’s a place that connects communities, transcends boundaries, and reaches far beyond our city's limits.

This new centre isn't your typical black box theatre. It is designed to be accessible and inclusive, fostering an environment where creativity thrives, and cultural expressions are celebrated as core to life. It's a place where irreverence, cheekiness, and stories from diverse backgrounds come to life.

This project was born from a commitment to fresh thinking and a reimagined brief, aligning with Geelong's 50-year vision as a clever and creative city-region, emphasising the need to evolve in a growing, dynamic community.

I believe that cultural institutions must adapt to the changing ways

people engage with culture. The Geelong Arts Centre's mission is to make live performances fun, special and challenging, ensuring cultural institutions remain relevant in our rapidly evolving world.

Through this project we embraced connection and community, giving prominence to First Peoples' stories and wisdom. Crucially, this transformation is a collaborative effort. We’ve loved the collaboration with ARM Architecture, Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, and the First Nations community in the G21 region. One central question guided us throughout this journey: How do we welcome Country into the fabric of this building? Together, we've woven traditional stories, language, and the essence of the land, creating a rich tapestry that spans the building's layers.

I must express my gratitude to Wadawurrung Traditional Owner Corrina Eccles for her support from the project's inception. Starting as passionate conversations with Christine Couzens, Corrina and myself, they evolved into a space of

shared storytelling, a place where diversity and the world's oldest living culture are celebrated. Our artists Kait James, Tarryn Love, Gerard Black, Mick Ryan, and mentor Kirri Tawhai, have played an instrumental role in shaping this transformative journey. Their work is inspiring, diverse, and profound, impacting not just the building but ways of working together. We invite all people to come and visit these spaces and artworks.

My experience in this journey has changed how I view collaboration and creativity, how I celebrate diversity, and appreciate the power of shared storytelling. The Geelong Arts Centre is more than a venue; it's a testament to our evolving culture and the boundless possibilities of artistic expression.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 4

A GATHERING PLACE

Lesley Alway Chair of the Geelong Arts Centre Trust

Lesley Alway Chair of the Geelong Arts Centre Trust

We all loved the original Geelong Performing Arts Centre that opened in 1981. Designed by Andrew Reed, it was then one of the most advanced performing arts venues in regional Australia. But 30 years later it was recognised that it could no longer adequately serve the community with the facilities and technology expected of a contemporary performance venue.

Designing and building a major new cultural infrastructure project is a complex process, but our objective was really very simple. We wanted an arts centre for the future – a unique and special cultural, community and culinary destination that incorporated the latest technologies and audience amenities to deliver extraordinary experiences, but one that also paid homage to the significant cultural, social and architectural heritage of the site.

And so the journey began to deliver a next generation Arts Centre. We wanted it to be fun, welcoming and a little bit magical. Our vision encompassed a range of priorities including respect for and incorporation of First Nations stories and heritage;

state of the art technology to improve production qualities; public spaces for community gathering and audience and artist accessibility; an open and transparent façade to reveal the activities within to welcome in community and locale and to be a good precinct neighbour in terms of the building design. In essence we wanted to turn the traditional black –box theatre inside out so that we were very visibly central to community life and a unique destination for local, national and international visitors. We wanted to be a showcase for not only local arts creatives – but also for local culinary creatives and producers.

We are thrilled that ARM has delivered on our brief, providing not only an imaginative linkage between the new Little Malop Street site and the earlier Ryrie Street project to create a new creative campus that encapsulates the updated Play House and Church spaces but also realises the extraordinary new theatre spaces of Story House and Open House.

5

DESIGNING GEELONG ARTS CENTRE — CREATIVE PLACES THAT SPEAK OF THE FUTURE

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 6

Ian McDougall Co-Founder, ARM Architecture

Ian McDougall Co-Founder, ARM Architecture

Geelong Arts Centre Stage 3 is a $150m centrepiece for the arts and entertainment community of Greater Geelong. It serves as the final component in the revitalisation of the former Geelong Performing Arts Centre, a transformation envisioned in the 2003 Master Plan. ARM Architecture commenced design work on this significant addition in 2019, with the completed project unveiled during a grand gala event on 18 August 2023.

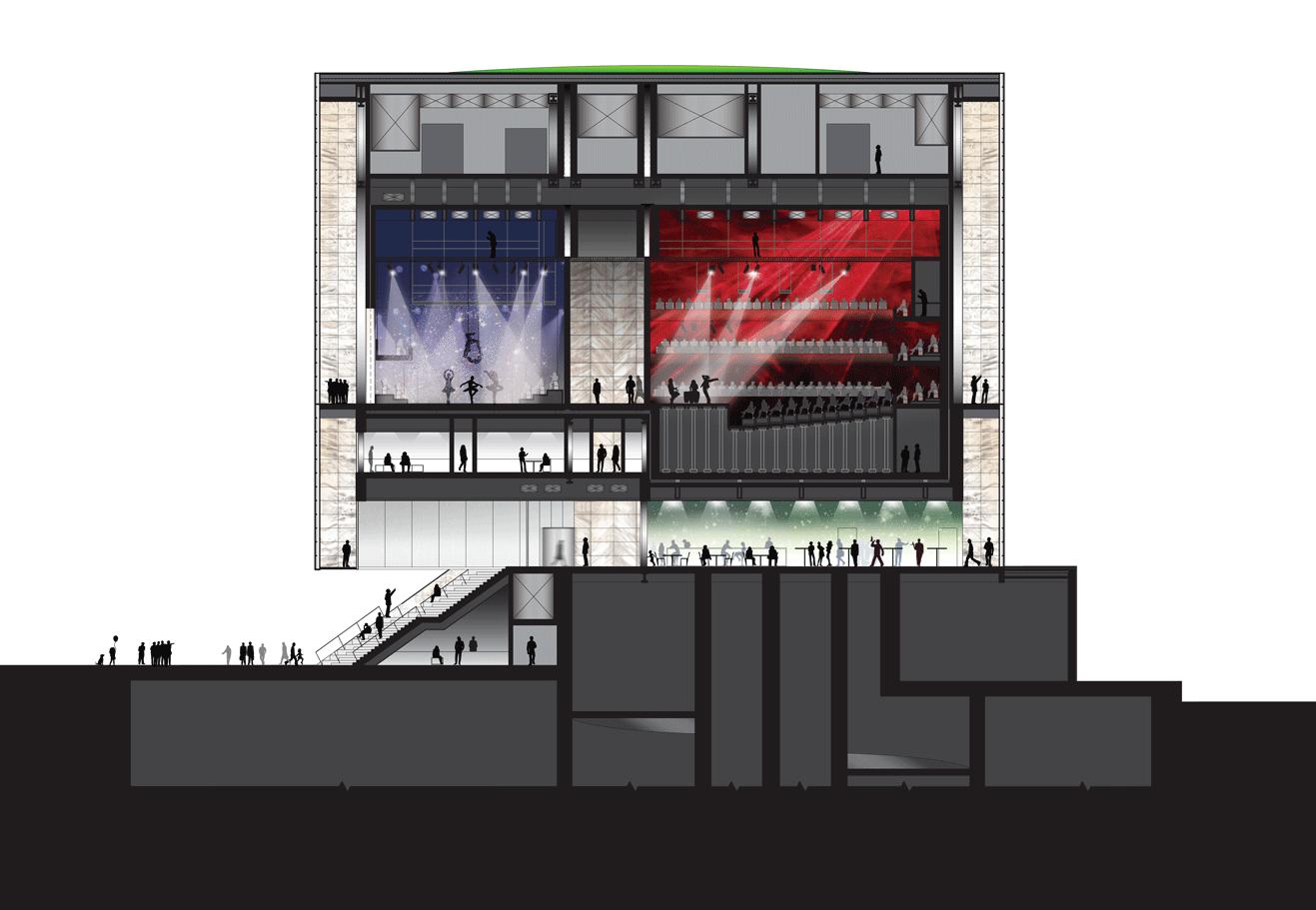

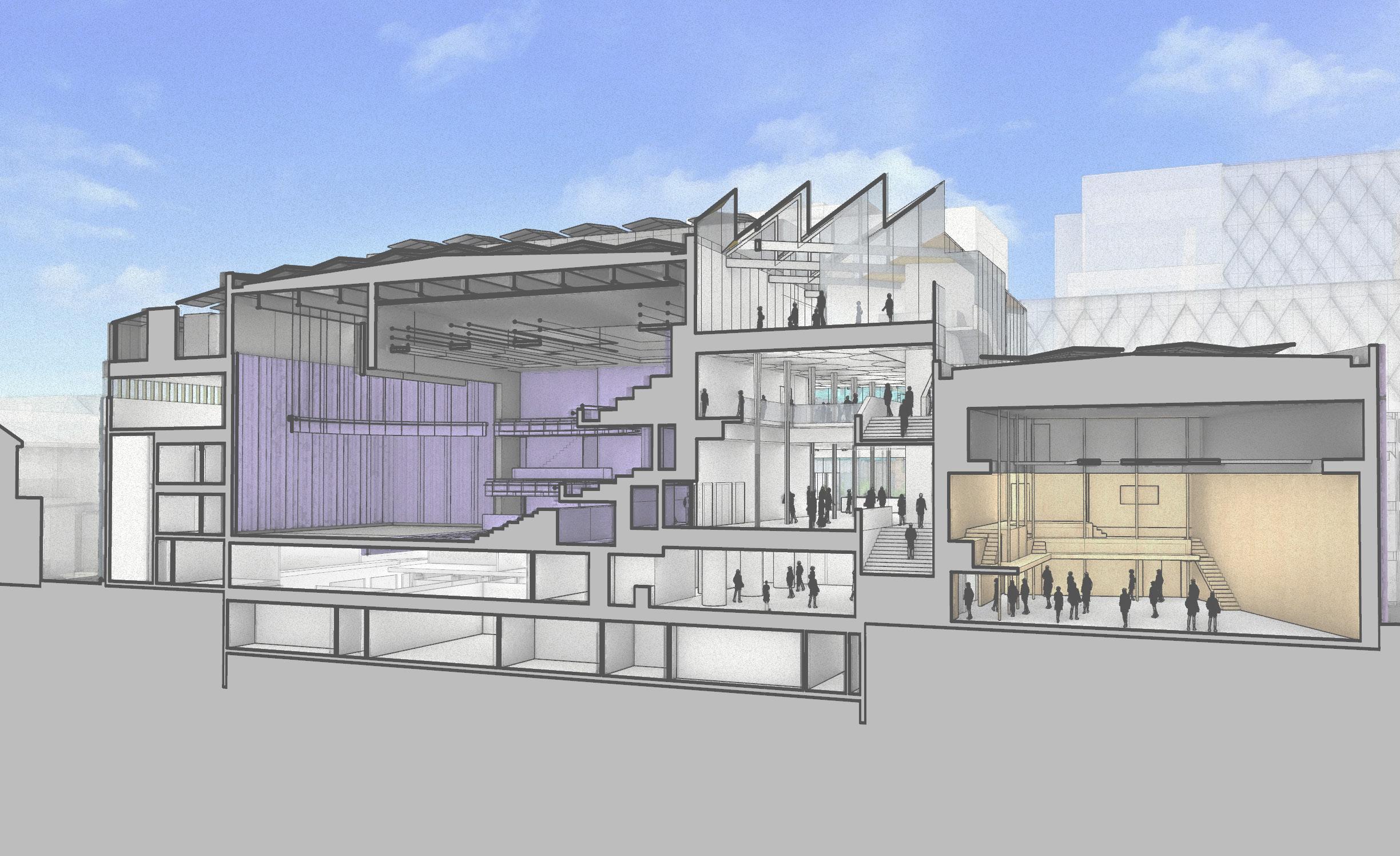

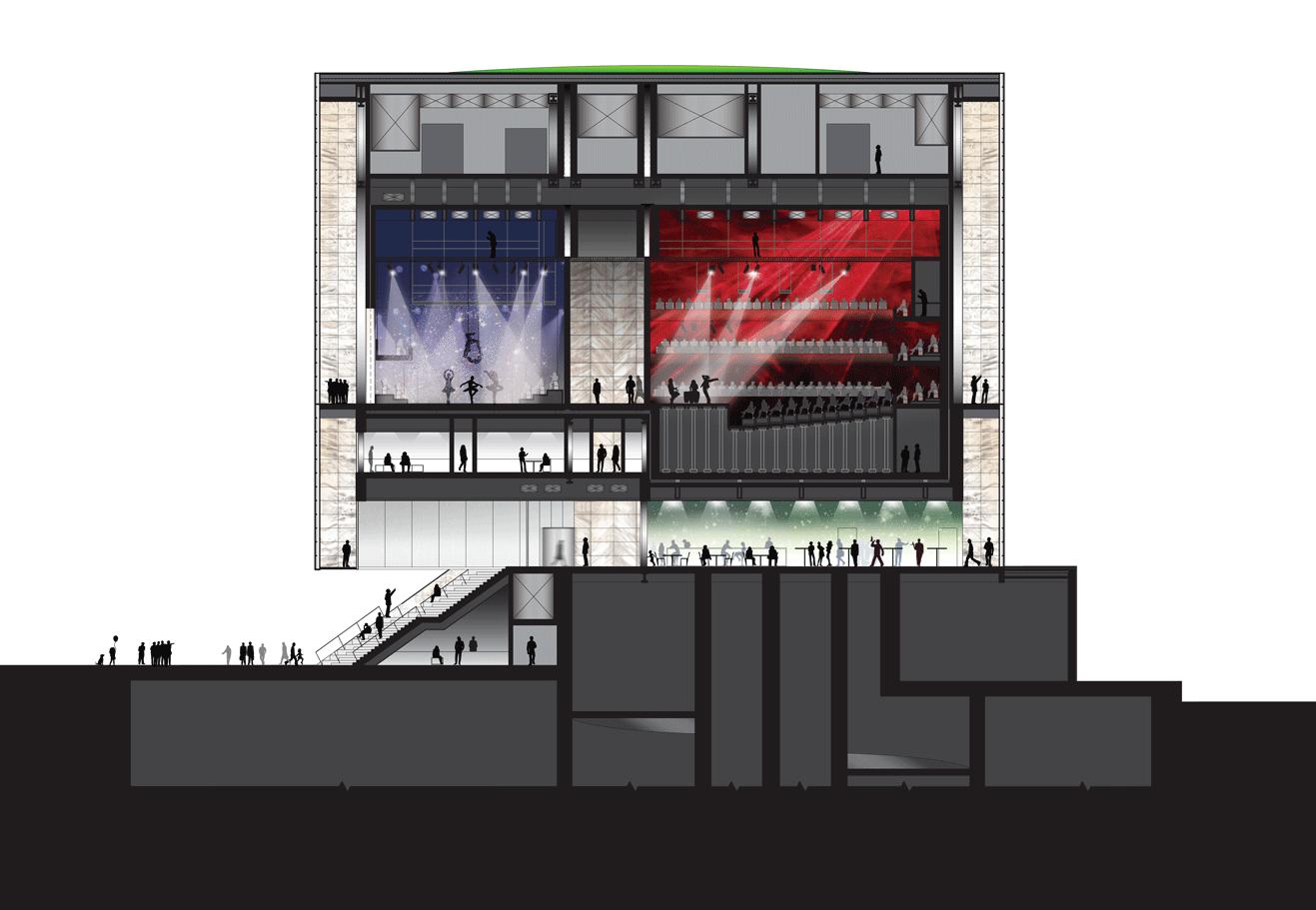

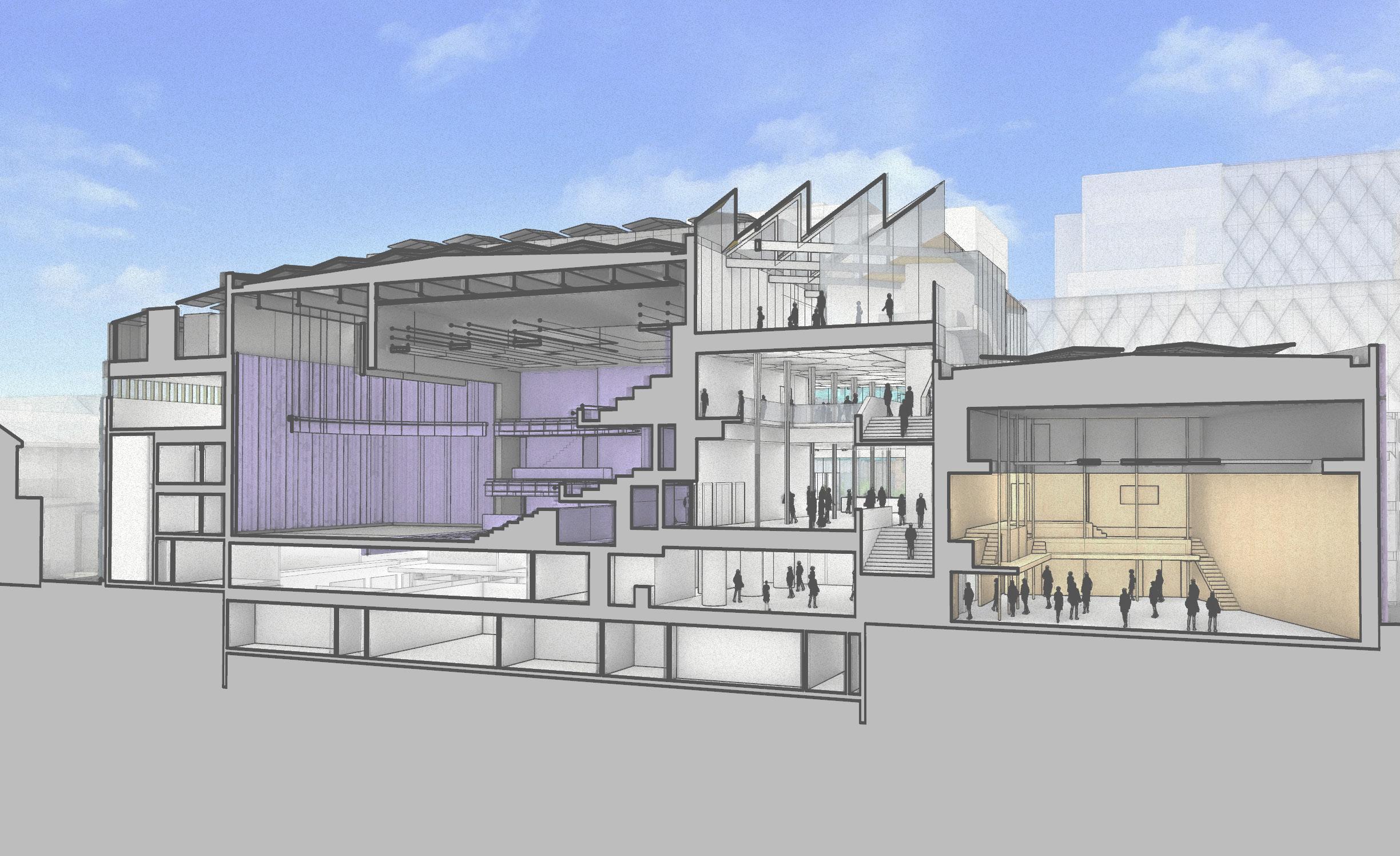

Stage 3 comprises two new stateof-the-art venues (a 550-seat multifunctional theatre, named the Story House, a 250 seat ‘warehouse’ style performance space, named the Open House), café, and a full array of backstage amenities and support spaces. All this adding to the existing 875-seat Playhouse Theatre and Stage 2 studios, making it the largest regional performing arts centre in the nation.

7

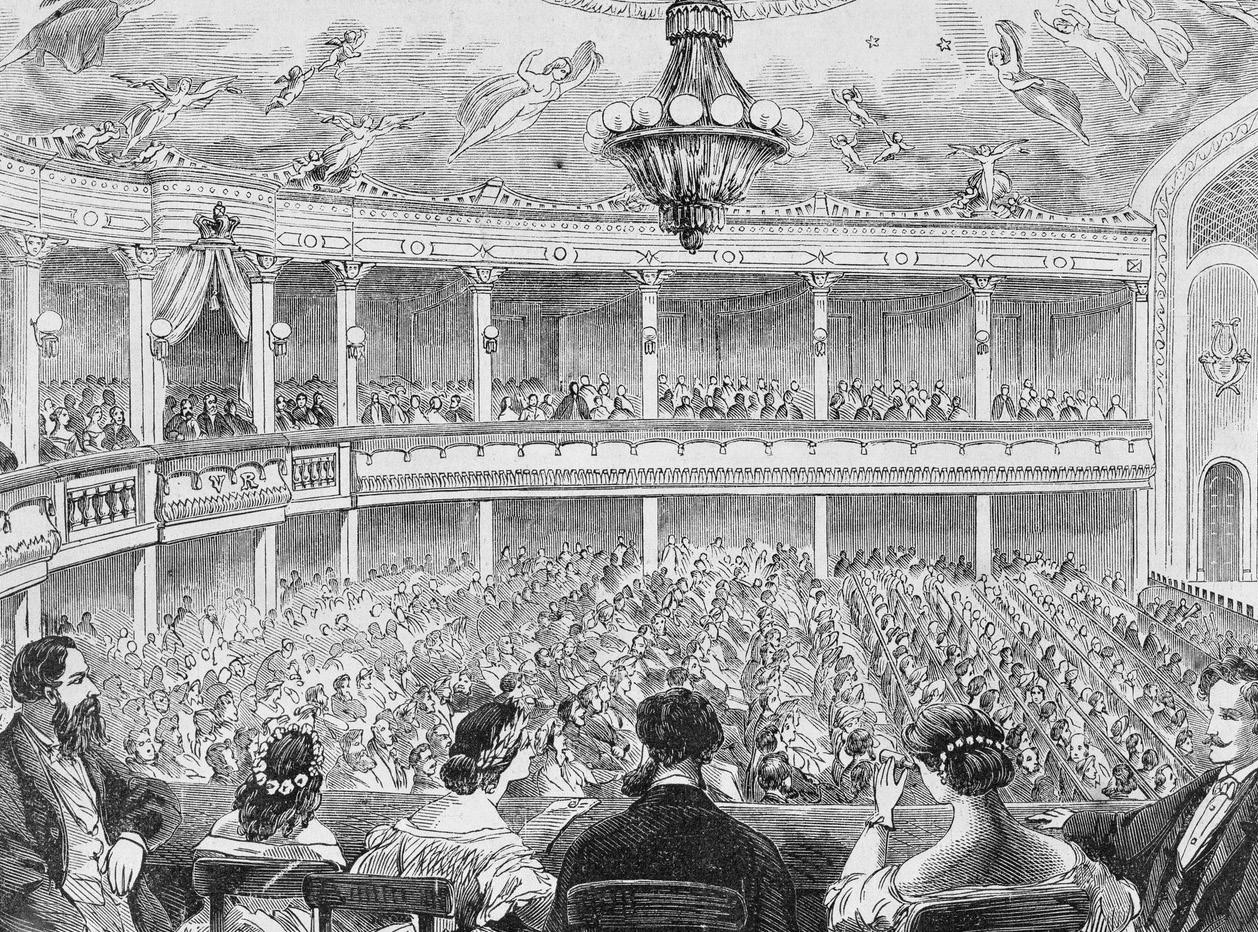

PERFORMING ARTS CENTRES IN AUSTRALIA HAVE HISTORY

In Australia, as in all cultures, the importance of performing arts, performance, dance, music et al to a community is pervasive. Performance and ceremony have always been central to First Nations culture. Omnipresent, participatory and structured, they are deeply significant to Indigenous life. Ceremonial gatherings are characterised by ritual dance, song, body decoration and apparel and are a key part of education, oral history and storytelling.

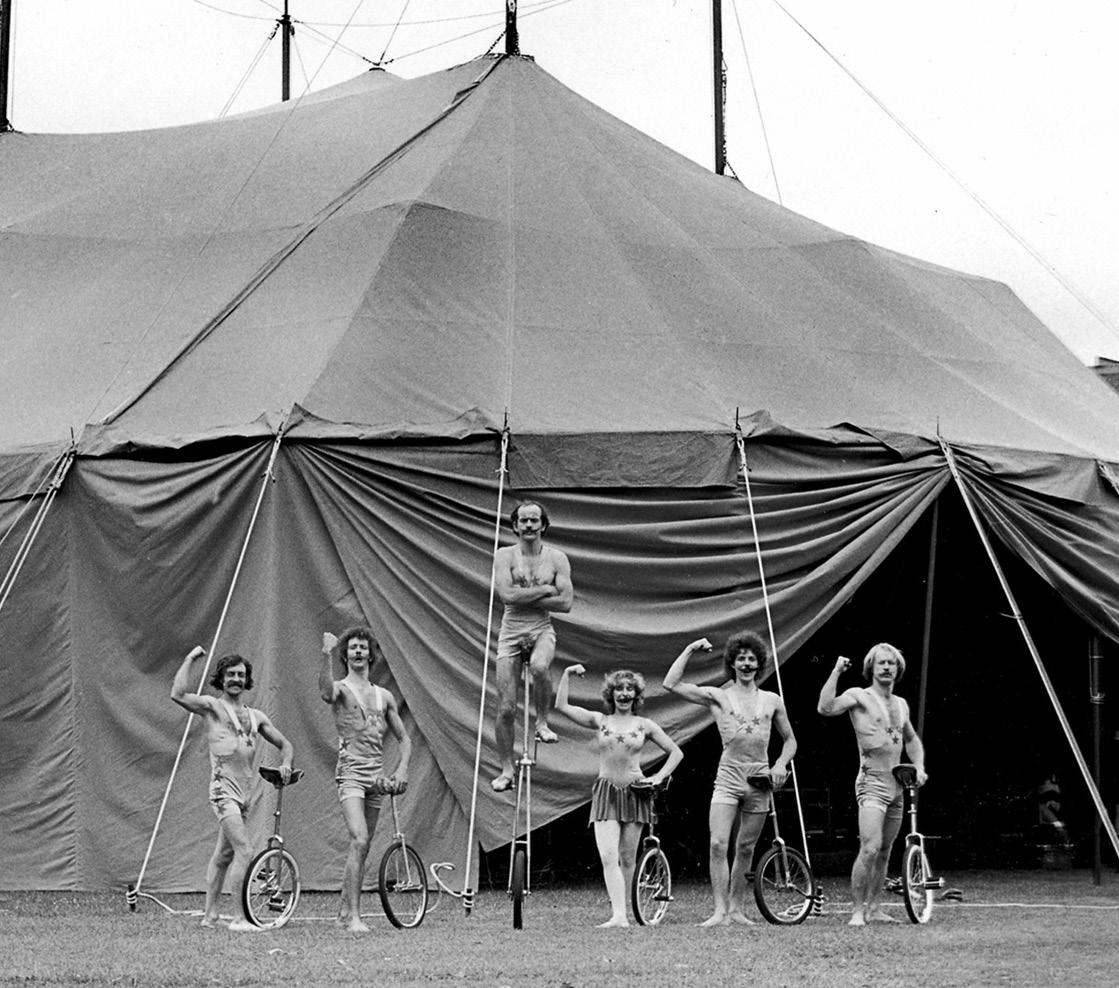

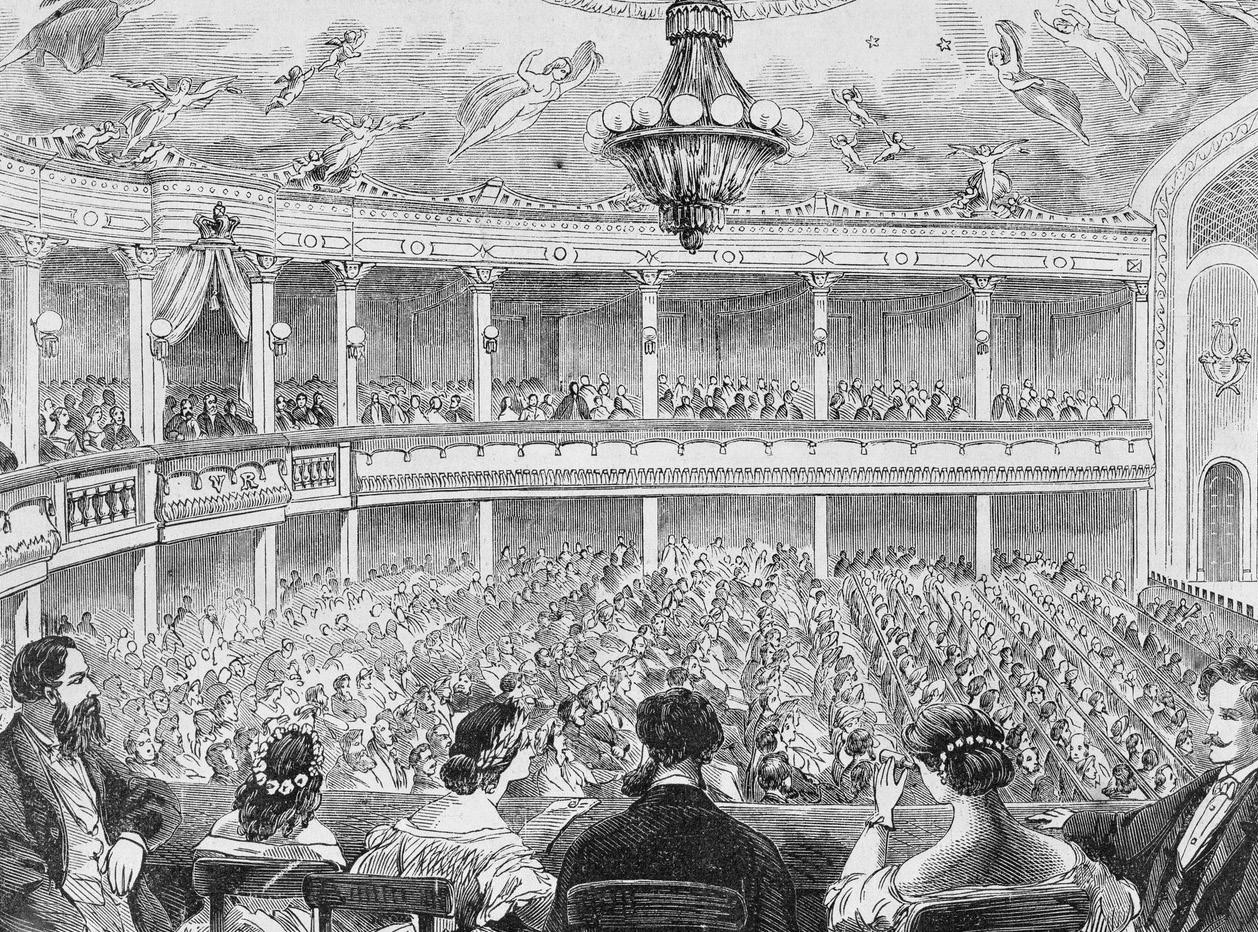

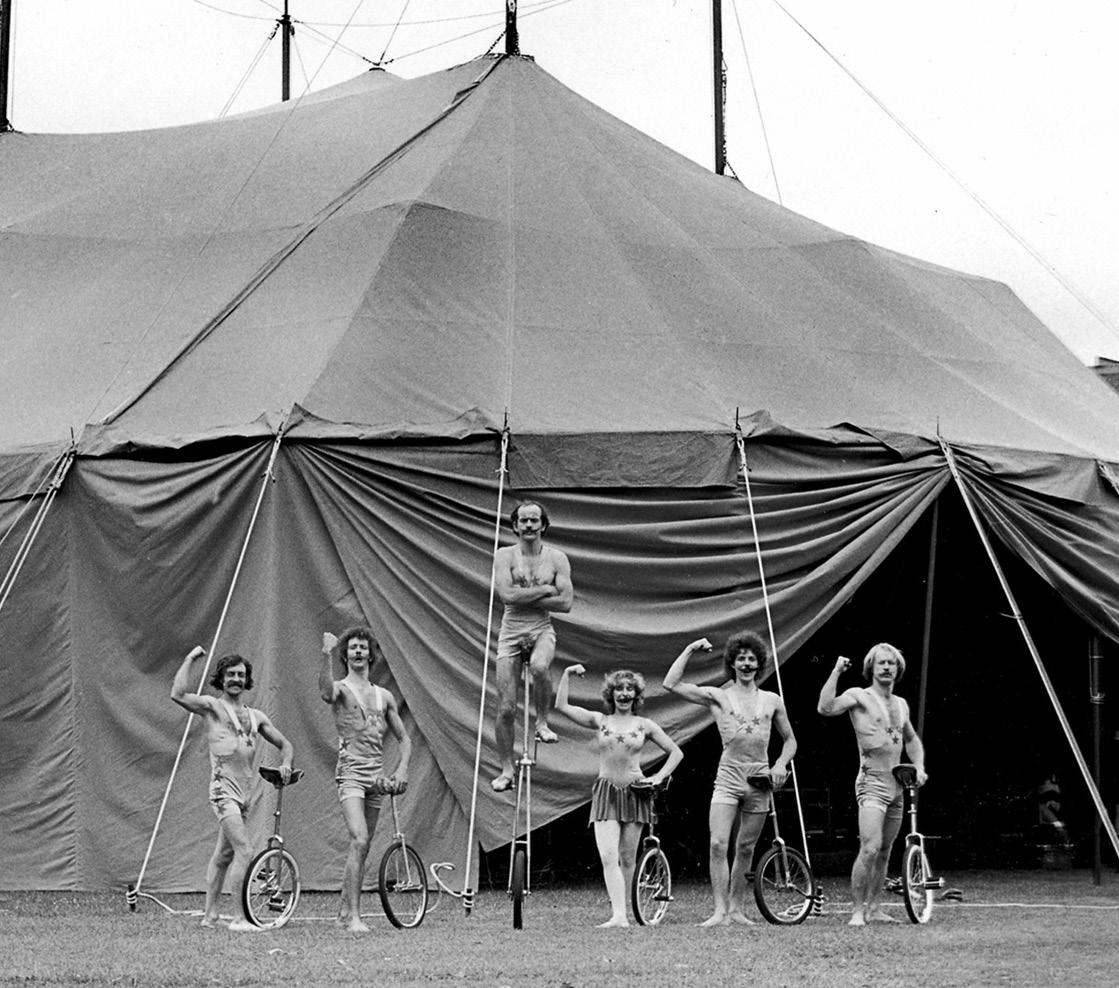

In 1789, just 18 months after the first fleet landed in Sydney, convicts performed ‘The Recruiting Officer’, a contemporary Drury Lane blockbuster. The first theatre building opened in 1796. By the 1830s, Hobart and Sydney had a flowering of venues, including the giant 1,000 patron Theatre Royal in George Street Sydney, a milestone conversion of a hotel into a theatre and circus space. While traditional theatre continued to grow, Music Hall, orations and recitals characterised performance types of both city and country centres of the 19th century, as well as open air events and circus. Performances boomed in new halls, theatres, saloons, town halls and even tent venues. International performers such as Lola Montez (1850s) and Chang the Chinese Giant (1870s) toured country Victoria, although the outrageous Lola was banned from performing in Geelong on her tour.

In 19th-century Australia, audiences flocked to a widening array of performances, leading to a boom in the construction of venues. However, venues quickly became standardised, encompassing the theatre house, the circus/fairground tent, and the town, church or masonic hall. By the 20th century, this expanded to include repertory theatres, black box theatres, clubs for jazz and stand-up, cabarets, rock venues, pubs, open-air festivals, and even theme parks as venue types.

In designing spaces for the arts, it is important to acknowledge Australia’s

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 8

diverse history of performance. Form is not dictated by function but more by culture and ritual.

We might propose that at the heart of all cultures one will find people attending, viewing and/or participating in art forms that are fundamental, story-based, musical, involve dance and movement or the making of pictures and patterns.

One could see these essentials in a continuous history of performance, old to new, in forms that exist today; contemporary dance, ballet, rap music, jazz, musical theatre, circus, Indigenous ceremonies, chamber music, opera and more. Speculating on the array of performance forms and representations is one way into establishing an expressive concept as one that does not divide these forms but embraces their links, variegation and texture.

In creating a design strategy for arts buildings, one can speculate on and express the variety and texture of the array of performance forms rather than separate each into a functional unit.

The broad span of performance types necessitates different built formats, which provides material for a more complex design trajectory for any project. That said, there are components to each performance event, especially for the patron, that are evident in all:

1. The consciousness of the Place in the mind of the community

2. The Procession – excitement and anticipation for the Place

3. Amenity at the Place – the gathering and the ritual of food

4. The Show, the spectacle and the technology of production

5. Aftermath, the download, the discussion over drinks

These notional parcels of experience and consciousness become useful criteria to generate a sequential architectural parti. That is to say, a designer must give careful attention to the chain of rituals and interactions people have with their environments when attending.

9

Royal Hotel housed the capacious Theatre Royal 1827- 40.

Mongo Mongo, Kamilaroi man, acrobat and expert rider with Royal Olympic Circus, Illustrated Sydney News 1855.

Sydney’s first theatre production, "The Recruiting Officer”, Playbill,1789.

THE IMPORTANCE OF REAL PLACES IN THE WORLD

The profound nature of what it is to be in a particular place is increasingly absent in contemporary design. There are many and historic reasons for this, not least the globalisation and homogenisation of culture that is intrinsic to Modernism. One of our driving interests as architects and makers of civic places is to explore the nature of contemporary place and the tensions between the local and global. Discovering the nature of a geographical and cultural place and manifesting that in architectural form is fundamental to the process of design. Design that does not do this renders a building (or place) voiceless, or even worse, meaningless. Each designer addresses this issue differently, but the best work – work that engages its community – creates meaningful narratives. Foregrounding local stories does not equal parochialism, nor does it signal a lack of global engagement.

Our local culture is constantly in exchange with global culture. Global narratives are filtered through the peculiarity of lives, ambitions and experiences of us and our location. A community’s connection with the world is defined by both the correlation and difference to other places. A designer’s challenge is to give physical presence to the dialogue between what corresponds to global practice and what is quite different by being local. Generating a design language of locally recognisable emblems or narratives, in a way that resonates with its community, is often what makes architecture successful.

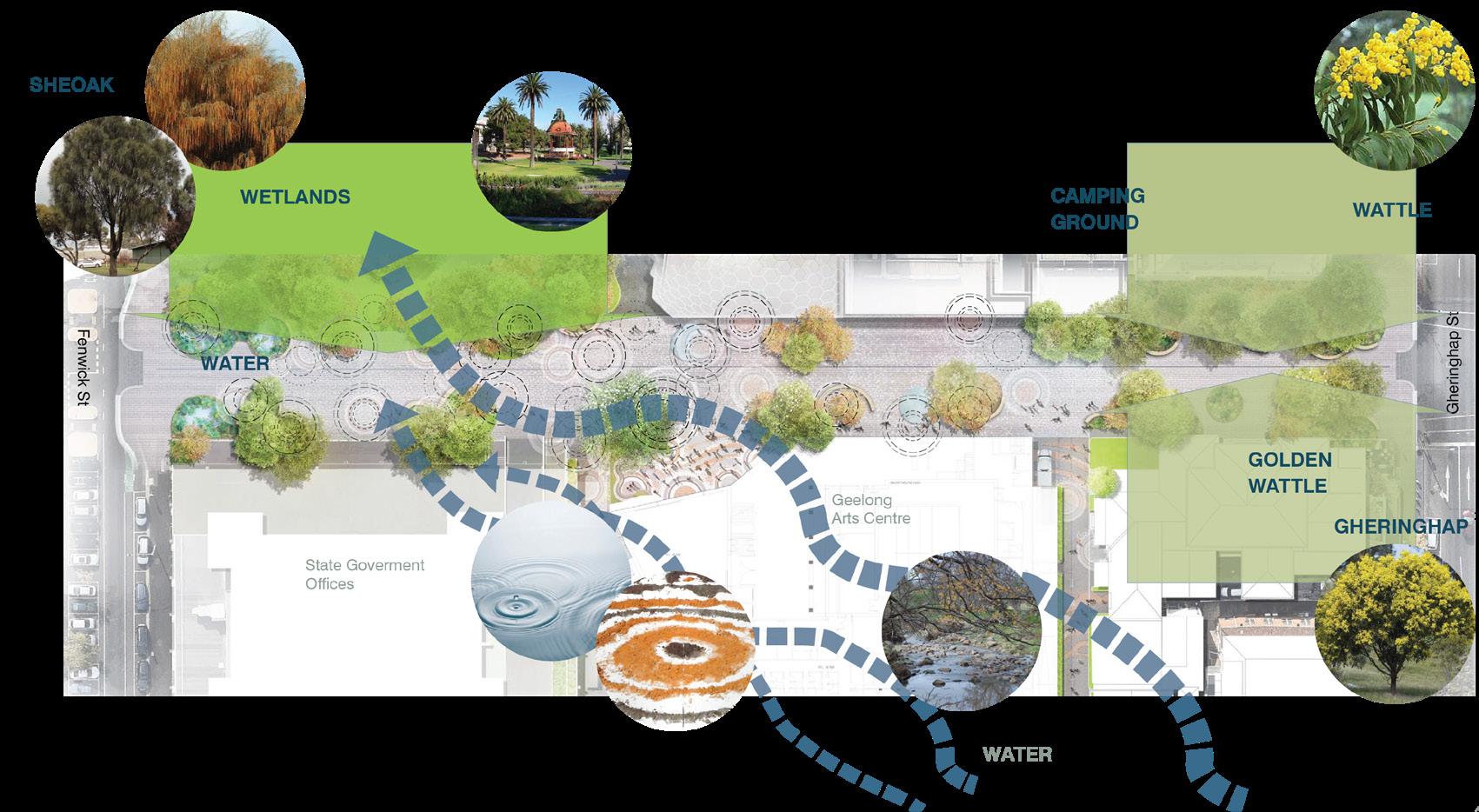

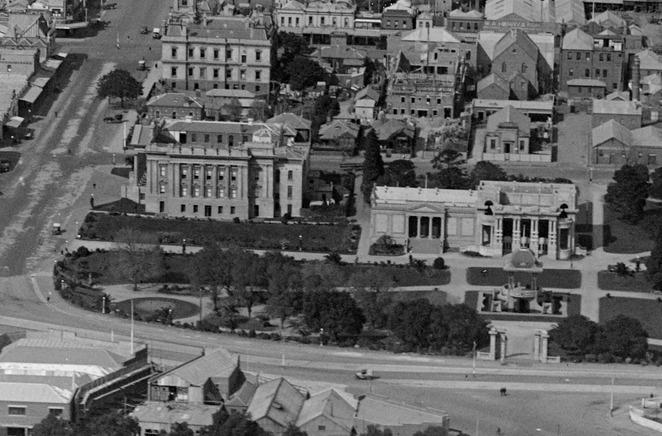

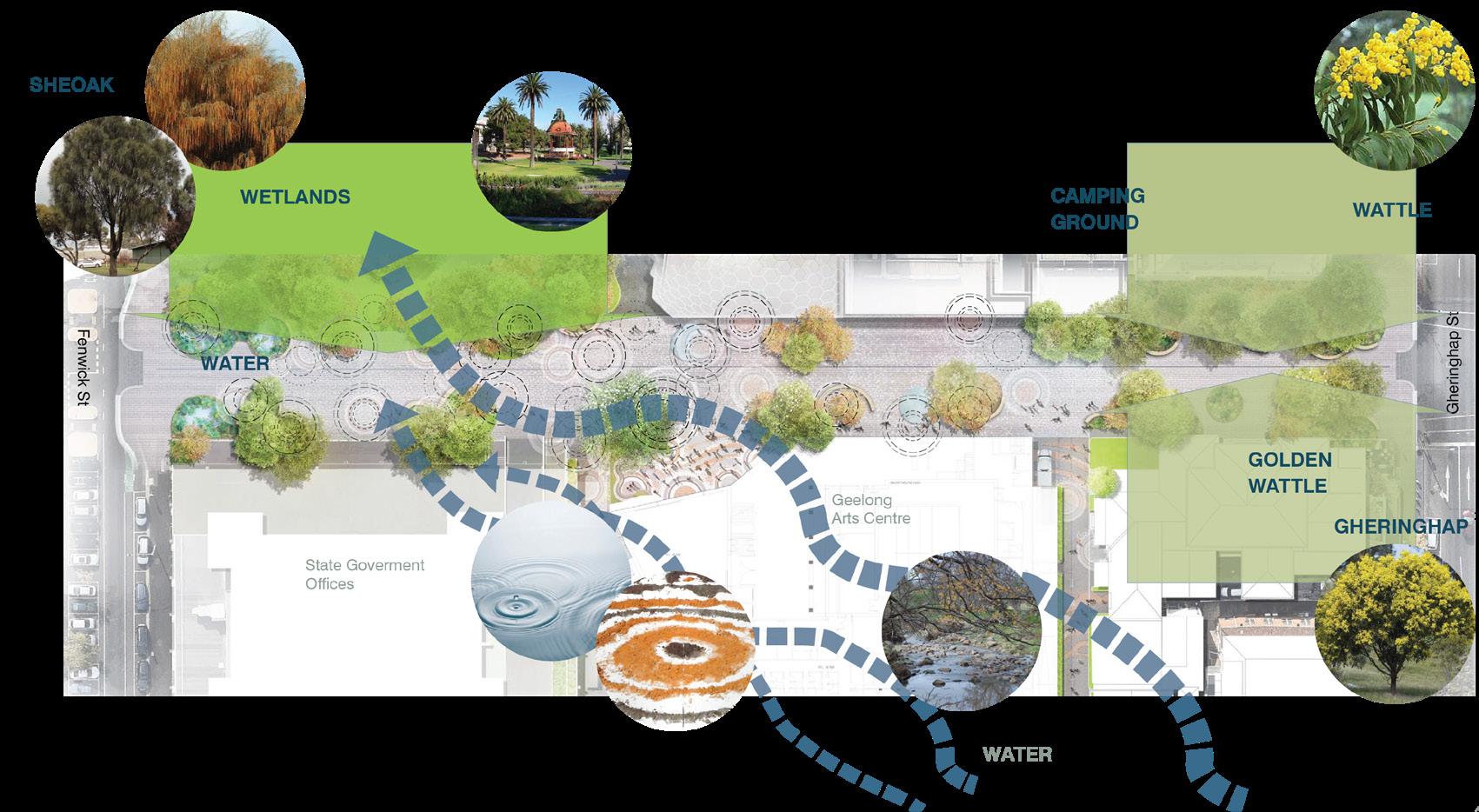

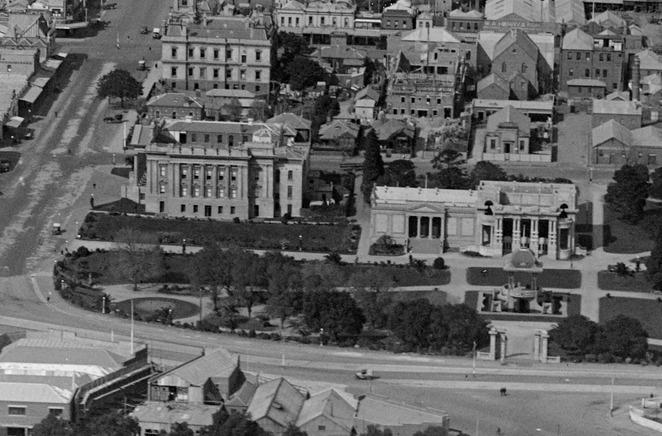

The Little Malop/Ryrie Street site has been a place of entertainment and community gatherings since the earliest times. To the local Indigenous people, the Wadawurrung, Johnstone Park (1872) was a wetland area, a stream and natural amphitheatre. This place was an important area for food and ceremony; a gathering place of the Wadawurrung for more than 60,000 years. European settlers named it Western Gully. In 1856, just seven years after Geelong was established as a town, a Mechanics Institute opened on the Ryrie Street side of the GAC site. Mechanics Institutes in Australia were community buildings usually comprising a public hall, a library, meeting rooms and exhibition spaces. The following year, a church was opened adjacent to the Institute and a Temperance Hall opened the year after. From the 1850s, the precinct became marked by the establishment of the park and gradually occupied by Geelong’s civic institutions and government, all adjacent to the watercourse.

The old Mechanics Institute burnt down in 1926 and was replaced with a new hall, known as the Plaza Theatre. When the new Geelong Performing Arts Centre was built in 1978, that theatre space was embedded in the new building. At that time the hall was called the Ford Theatre but was later renamed the Play House, which is still its name today.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 10

GAC site view with original Post Office, Telegraph Station, and Mechanics Institute (far left) c.1860.

Map of Geelong showing "Western Gully” near the Wharfs 1850.

This site history is a significant cultural narrative which can generate a rich design trajectory for the redevelopment of GAC. Since the site is an aggregation of preceding performance spaces, any new facilities can be part of this resonant patchwork, combining the memory, the remnant, the existing, and now the new. Each “pavilion” is the product of different strands of our cultural history, interwoven into series of places, a campus, a village that is the Geelong Arts Centre.

11

Mechanics Institute c.1866.

Geelong Performing Arts Centre 1981.

GAC site with Mechanics Institute, Church and Hall 1927.

THE CASE FOR THE BEAUTIFUL ROOM

In contemporary theatre design, the driving program in their creation is towards a dark neutrality, equipped to the teeth with machinery for performance and production. 20th century theatre design generally works from 3 distinct and parallel types: the proscenium theatre, the black box studio and theatre-in-the-round. Formulaic briefs for these spaces, while functionally defined, tend to generate an apparatus, spatially placeless, characterless and closed.

The fixed proscenium theatre traces its origins back to the rectangular rooms of 1580s Italy. As we progress into the early 20th century, theatres evolved into the familiar structures we acknowledge today, comprising elements such as the stage, flats, curtains, proscenium, pit, stalls, circle, and balcony. Before the 1940s, auditorium interiors were adorned with elaborate decorations, especially in larger theatres such as Melbourne's Regent Theatre. Even in smaller venues like the charming Theatre Royal in Hobart or more frugal theatres like the Queen’s Theatre Adelaide, intricate interior designs were a hallmark of their audience spaces.

13

Teatro Farnese, Parma, Italy 1628.

Princess Theatre Melbourne, lithograph 1865.

Theatre Royal, Hobart 1837.

Opposite: Palau de la Musica Barcelona 1908.

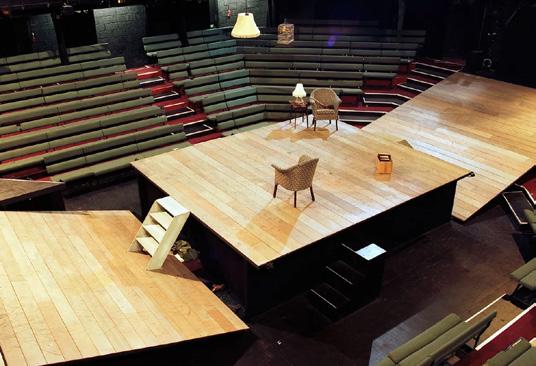

The ‘black box theatre’ on the other hand developed from an avant-garde rethinking of the proscenium theatre as a type and genre. The devolvement of the passive viewer/performer hierarchy begins in the 1920s, influenced by people like Antonin Artaud, by a demand for flexibility, experimentation and stripped back (poor arte povera) production, allowing performances everywhere and anywhere. This demand continued to develop into the 1960s, especially in America and Europe, as exemplified in Peter Brook’s and Jerzy Grotowski’s work.

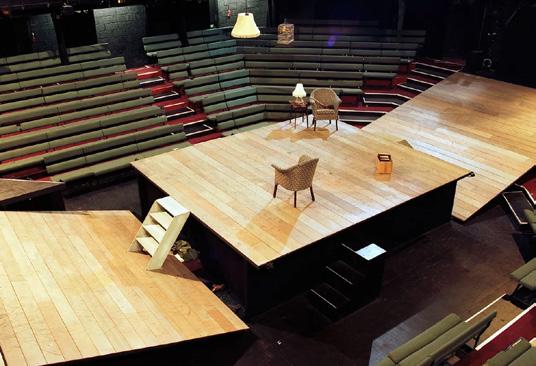

The player/viewer theatre space underwent additional deconstruction, giving rise to 'in-the-round' spaces in the 1970s-80s. This shift reflected a growing preference for immersive experiences and a merging with circus/arena elements within the theatre realm. However, the constraints of a permanent in-the-round layout have led to the gradual superseding, and almost disappearance, of this model as a permanent built form.

If the 20th century was characterised by proscenium and black box typologies, the 21st century appears poised to witness a dynamic fusion of these, giving rise to a spectrum of highly adaptable and acoustically enhanced spaces. We find ourselves at the brink of a design era where continuous advancements in staging technology offer remarkable flexibility, allowing for a myriad of performance setup possibilities.

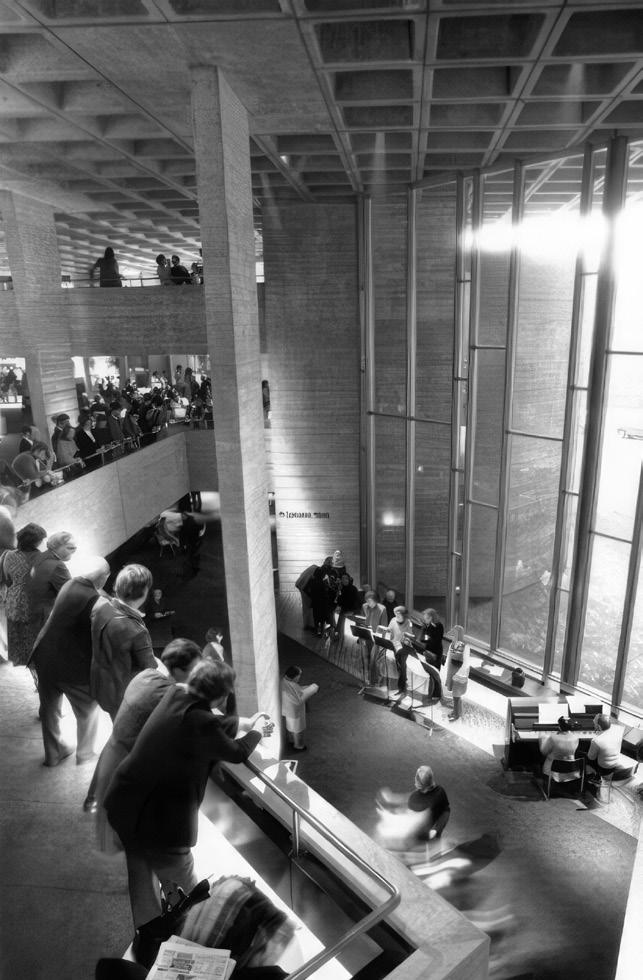

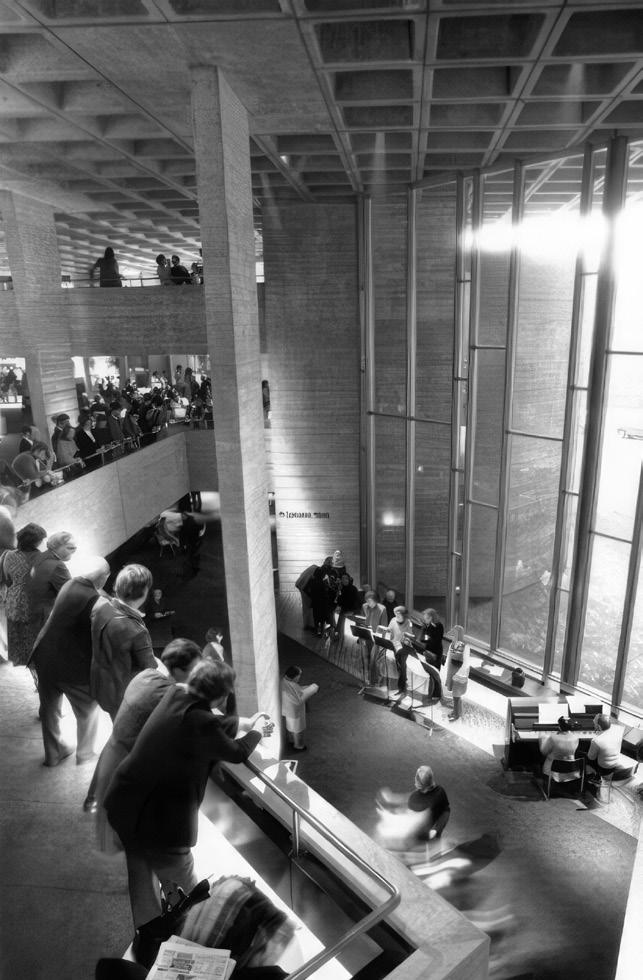

So, what becomes of a space in this evolving landscape? In the 20th century, the allure that defined earlier halls, spanning from the Baroque to Victorian to Art Deco, was all but discarded. The pursuit of a larger audience, aiming for commercial abundance, gave rise to vast-scaled auditoria. Concurrently, the reductive style of the era led to the creation of new halls that exuded an air of emptiness and somberness. Consider, for instance, the interior spaces of London's National Theatre (1963) or even Perth Concert Hall (1973).

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 14

Young Vic London set c.1970.

Foyer at the National Theatre, London 1976.

Dr Faustus set, in Opole, from J Grotowski book Towards a Poor Theatre 1968.

Tight budgets, coupled with an uneven focus on technology and building services, alongside the prevalent architectural style towards puritanism, pseudo-efficiency and the austere, have culminated to negatively shape visitor experience. Unfortunately, this combination often results in environments ranging from lifeless industrial settings to ponderous and even dire atmospheres. These are not places for joyful get-togethers. Nor places that empower the audience. Any mission to create a beautiful place to inhabit, to be enveloped, was increasingly resisted in order to conform with the self-righteous rhetoric of modernism and technology, succumbing to the dominance of stage-centricity.

In their paper “The Problem of Permanence”, Glow and Johanson (2017) note that:

“…… the trends of the past two decades, such as migration and universal education,

have increased the diversity of potential audiences, (and so) dedicated arts centres are regarded as less accessible to and popular than temporary, incidental and multi-purpose spaces.”

Theatre spaces and performance venues should, indeed must, be places where people want to spend time, and not solely for the show. We see an increasing demand for spaces that are welcoming and intriguing. We see an increasing rejection of no-places, of anywhere-places, spaces without a story, spaces without a sense of being in a particular community. We see patrons, both local and visiting, expressing their preference through repeat visits for spaces that captivate the senses, providing an astonishing and, indeed, beautiful experience.

15

Perth Concert Hall, Perth 1973.

BUILDING IN PARTS — A DESIGN ARMATURE FOR GEELONG

The history and layout of the old GPAC site tell the story of a cultural campus, a gathering of diverse buildings. This includes an historic church, a former Masonic Hall transformed into a theatre/dance hall and later a cinema. In 1981, a new theatre was introduced, along with a renovated theatre and an entirely new backstage. More recently, in 2019, the Studios Building (Hassell) was added to the mix. For Stage 3, we embraced the campus concept with enthusiasm, deliberately emphasising that the Arts Centre is not a solitary building but rather a collection of equally significant places. These spaces, both new and old, are intricately interconnected as nodes along the journey through the precinct. Each of the existing elements has been created with a distinctive symbolic sense. We did not seek to cover up the conglomeration. We did not impose a new overarching order onto the field. Instead, we emphasised the tapestry, appliqueing the new with the old.

This design approach breaks away from the tropes of a unified

modernistic whole. Instead, it reconnects with pre-modern traditions that celebrate the potential of Figuration and Fragmentation, especially in the realm of architecture.

As architectural historian Dalibor Vesely noted in discussing Piranesi’s ‘strategy of fragments’:

“The ‘inventive’ strategy of … experimental designs coincides in principle with the eighteen century belief that to know something means to break it down into simple elements and then to combine them in a new order.”

In contrast to the prevailing trope of unity and wholeness, GAC originates from the idea that an authentic and evocative physicality can emerge from independent components. Each of these components possesses a narrative core and internal unity, and when aggregated together, they form a larger, richer entity. This is a design strategy that can be seen in all sorts of artistic endeavours, drawing parallels

to practices such as collage and the assemblages of Joseph Cornell. It resonates with the principles seen in portmanteau cinema, the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, and the rich tradition of folk art.

The Geelong Arts Centre is a very different arts building. It is embedded in its place, Geelong, rather than the product of an international style manual. It was conceived by drawing on the unique cultural history of its location as well as Australia’s history of performing arts. The Centre is complex and clustered rather than simple and singular. It is self-consciously representational and narrative based. It has been developed to accommodate the widest range of performance and event types to welcome a diverse community and cultural span. The venue spaces are created as beautiful rooms, spaces you want to be in, even when there’s nothing on. The ambition is to put art centres back into the heart of their communities.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 16

EPISODES ALONG THE TRACK

NEW VENUES AND PLACES

All New Back Stage & Front of House

T250 Flexible Performance Space

Flat floor with terraced balcony

Seating 259-286 people, main floor area 260 sqm

T500 Theatre

Flexible floor & 2 balconies

Main floor changeable

Flat/tiered and rectractable seating

Seating 521 (end) / 555 (cab) / 580 (round) /850+ (mosh)

Main floor area c.430 sqm incl stage

Courtyard

Stepped edge with central flat space

Area c280sqm

Compliance Work

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 18

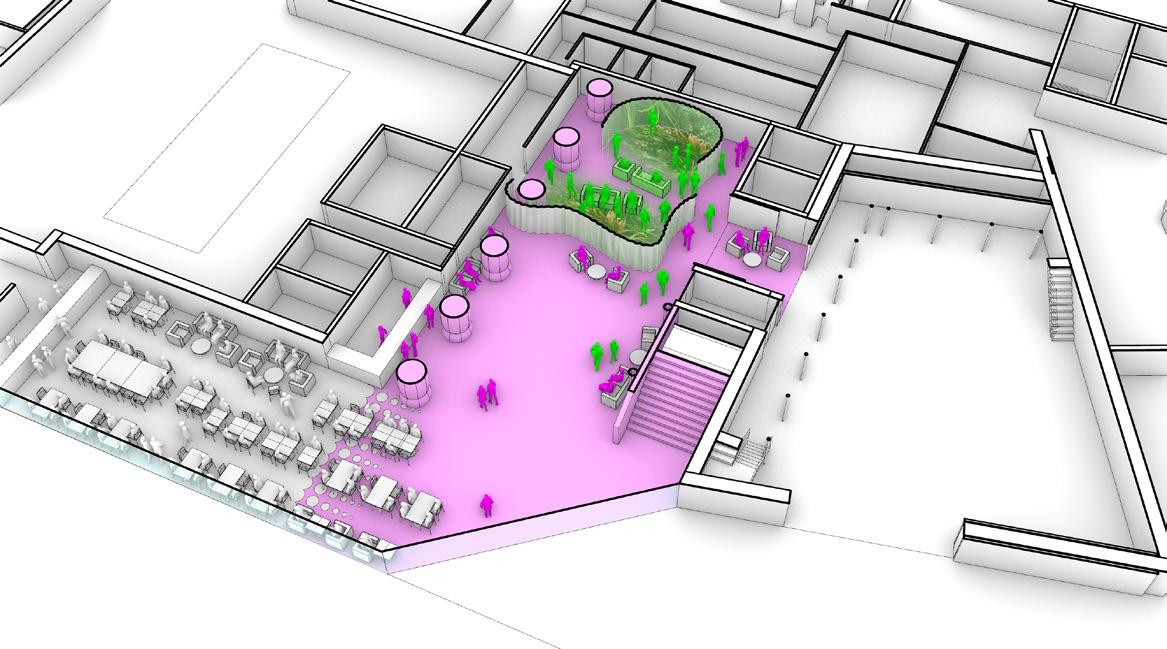

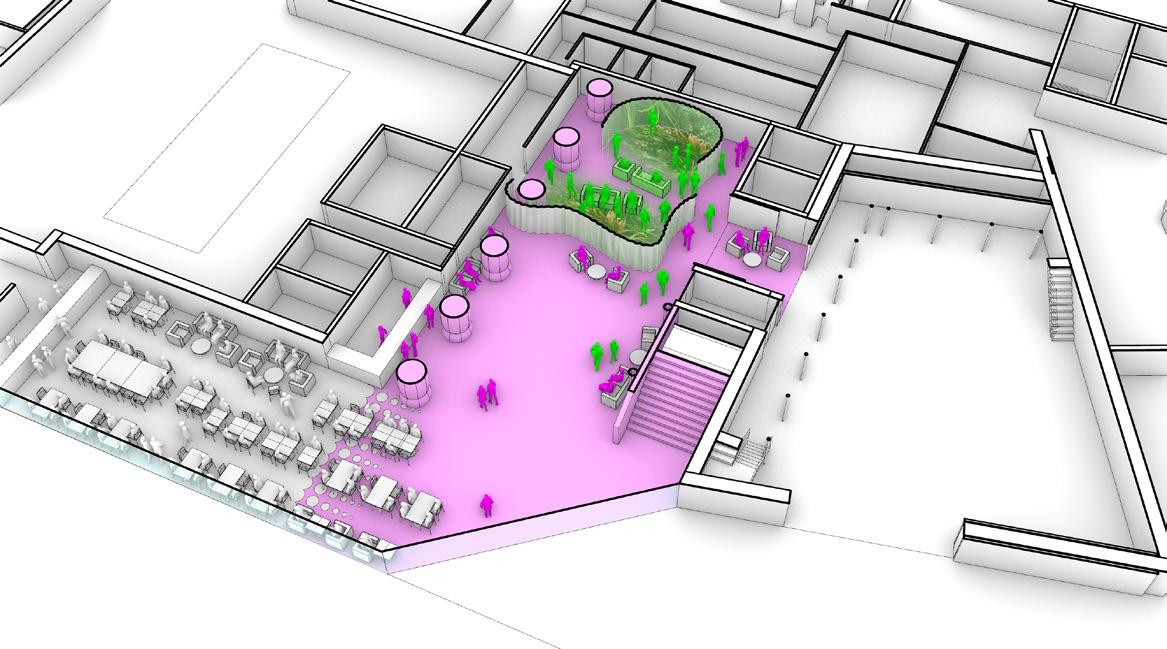

LANE LINK

PLAZA FOYER

CAFE

COURTYARD

PLAYHOUSE

OPENHOUSE

LANE

STORYHOUSE

THE CAFE

Over the past 30 years, the increased accessibility of public institutions has led to a redefinition of the visitor experience. This shift has moved away from formality towards a more approachable, people-oriented character, particularly notable in cultural institutions. The amenity provided by retail, food and beverage and educational facilities is no longer optional but integral to the vitality and financial viability of a centre.

Tutti, GAC’s dining destination, is a shop front on Lt Malop Street right at the front door, intermingled with the entry foyer. It is signified on the street as a discrete, embedded, stage-set street cafe, serving out to footpath diners, and inside blended with the entry foyer. Being in that spot and

highly visible creates a sense that the GAC is active and ‘always open.’ In terms of the viability of the food offer, its placement supports its longterm viability independent of show programming. The café is a key part of the entry procession – the experience of arrival is a community embrace. It is both amenity and ambience.

19

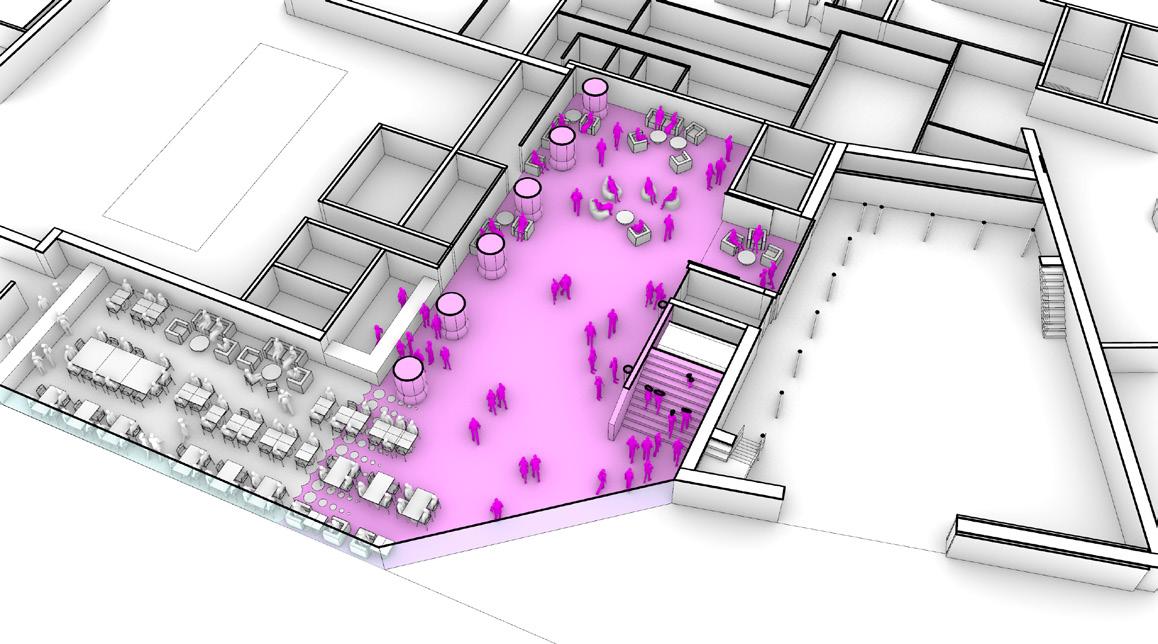

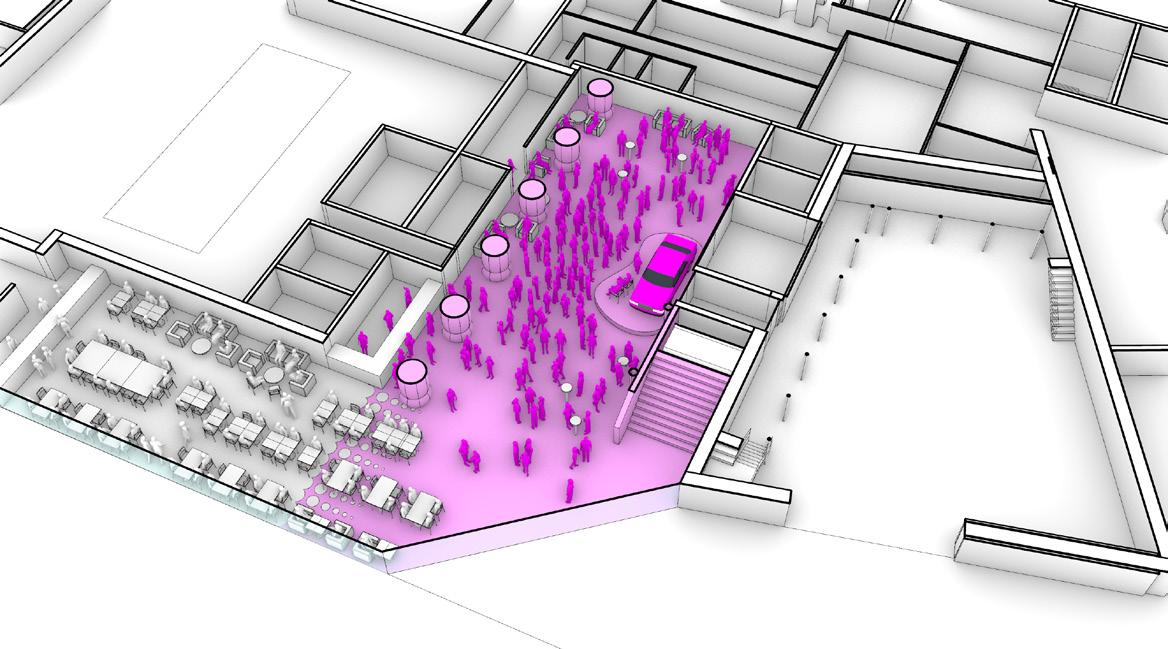

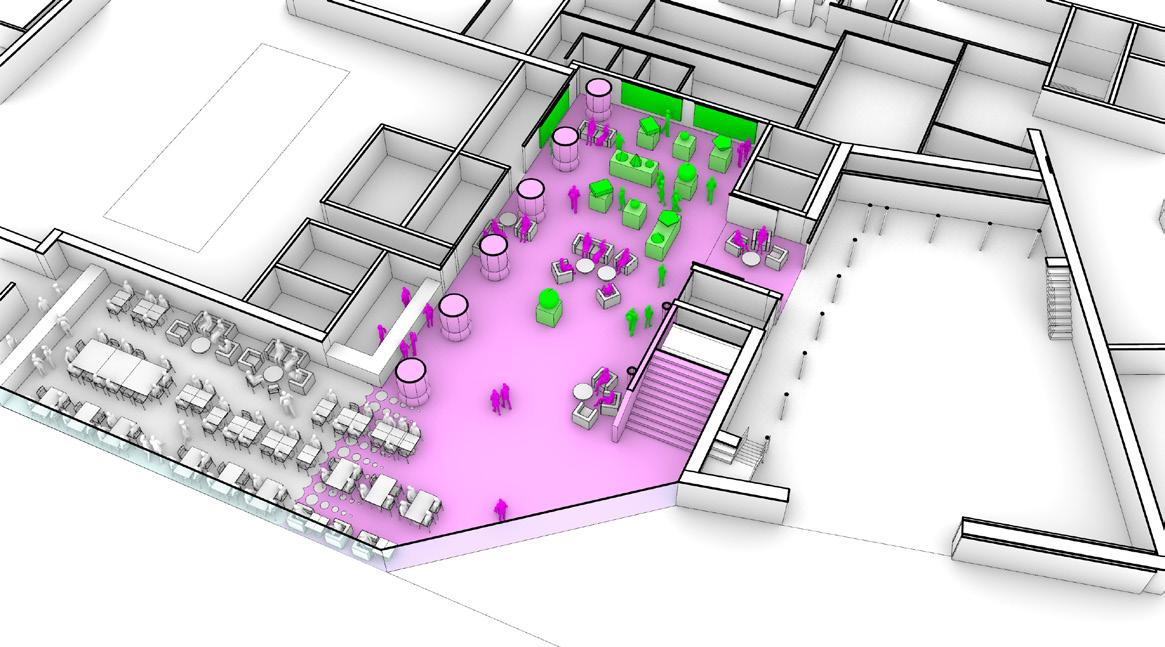

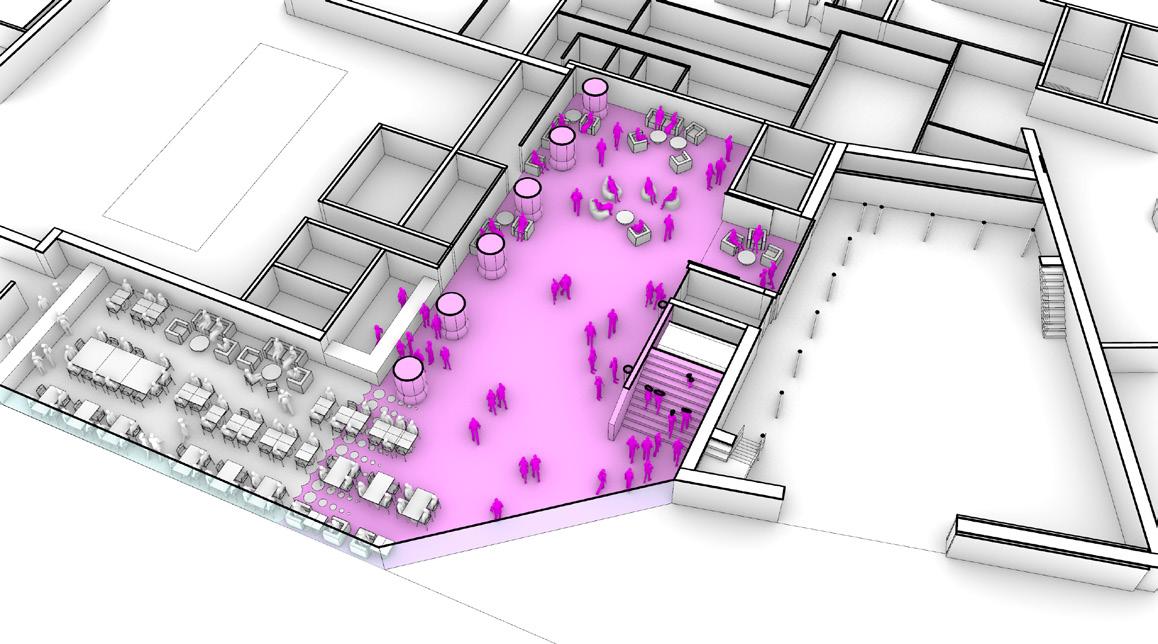

THE GROUND LEVEL FOYER

19th century theatre foyers were little more than cramped hallways. In more recent times, foyers have become blank and/or cavernous, more akin to the public spaces at airports or offices. GAC’s brief called for foyers that would be “inviting and welcoming … vibrant”, “lively at all times” and transformable from social hub to performance space. Not neutral. Not empty. Foyer spaces can be much more than just waiting spaces – they can serve as a welcome mat, an inside/outside connector, performance space, party space, display space. The days of unsociable no-man’s-land foyers need to end.

The new entry foyers are designed to celebrate the magical and surreal elements of performance. In conceptual terms, the singular space is articulated as three juxtaposed stage sets: the entry café, a public lounge room, and a white salon. Similar to the rotation of a stage set, each thematic décor unashamedly abuts the next, offering an immersive experience when observed all at once and, as one walks through, transitioning from set to set.

Functionally, the foyer serves as the primary gathering space at GAC—a welcoming arrival node that combines concierge services, a bar (which also functions as the theatre bar), and ticketing kiosks for incoming patrons. It is equipped with the technology for display, performance and events, and is very good at accommodating and engaging a crowd pre or post event.

21

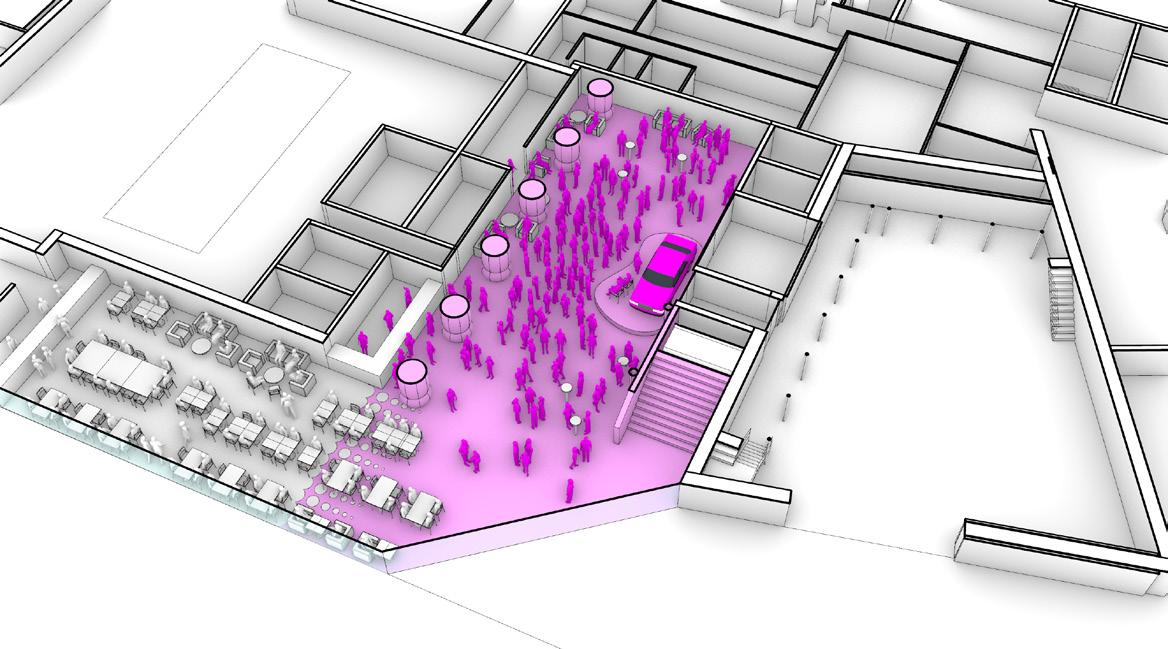

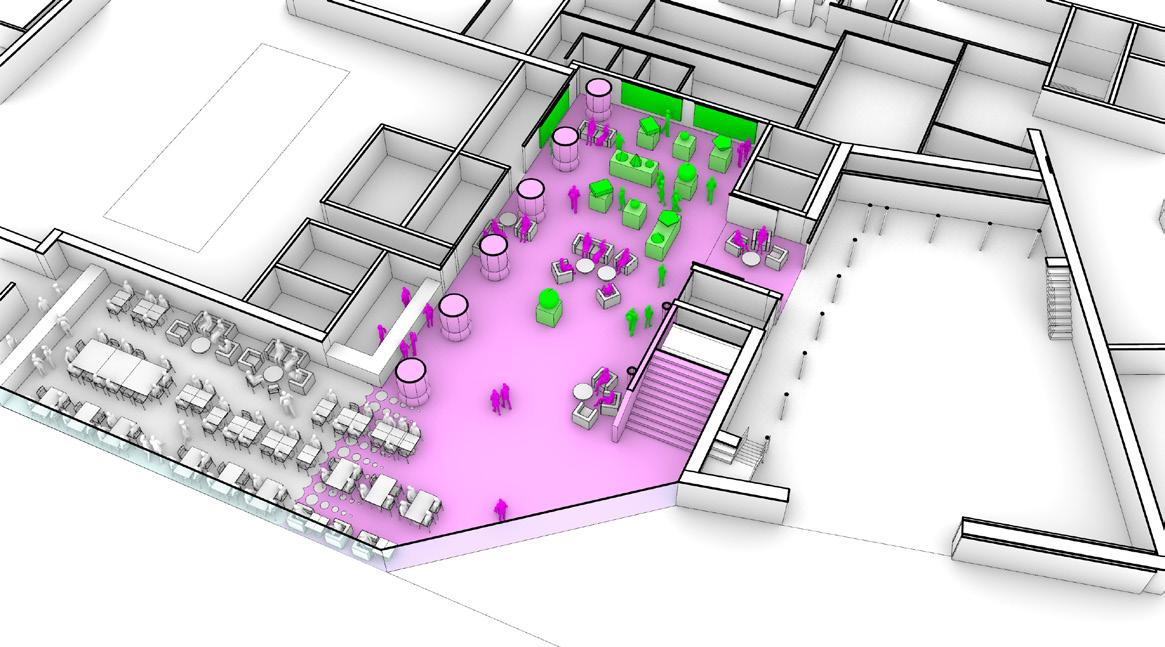

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 22 ARRIVED EARLY BEFORE A SHOW IN THE MAJOR WAREHOUSE SHOW – INTERVAL TO AMENITIES TO AMENITIES LIFTS WAITING AT BAR 15% EVENT BAR FOR HIRE 150 PEOPLE

23 TO AMENITIES LIFTS EVENT SPILL INTO FOYER & ACCESS TO AMENITIES MARKET/FESTIVAL IN

FOYER ENTRY CLOSED ACCESS TO LIFTS & AMENITIES THROUGH INSTALLATION ACCESS TO LIFTS & AMENITIES THROUGH INSTALLATION

IN EVERYDAY MODE WITH FURNITURE REARRANGED FOYER IN EVERYDAY MODE WITH FURNITURE REARRANGED EXHIBITION/IMMERSION/ INSTALLATION – ‘LIGHT’

WAREHOUSE & PLAZA

FOYER

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 24

THE OPEN HOUSE

The new GAC includes a unique type of performance space: the ‘Open House’. Functionally, the space has been conceived to accommodate the widest range of performance and event opportunities but was also designed to exude a particularly informal character.

It is a multipurpose space, designed here as a remarkable room to be in, unlike the unsatisfactory antecedents such as the school sports hall or the black box.

The GAC brief specifically called for a welcoming space at the core of community gathering. The Open House has been designed to blend the characteristics of a small memorial hall with those of an old warehouse. This approach stands in contrast to recent trends that prioritise the establishment of a theatrical machine.

As a theatre typology, it is a flat floored space with two sides hosting balconies. It can be set up in many operational modes, offering a multifunctional space. In traditional end-on theatre mode, it can house approximately 250 patrons. Unlike its small hall ancestry, it has a hightech loft across its entire floor area

furnishing flying, lighting and sound equipment for all sorts of events and shows. Unlike its black box siblings, it can be daylit.

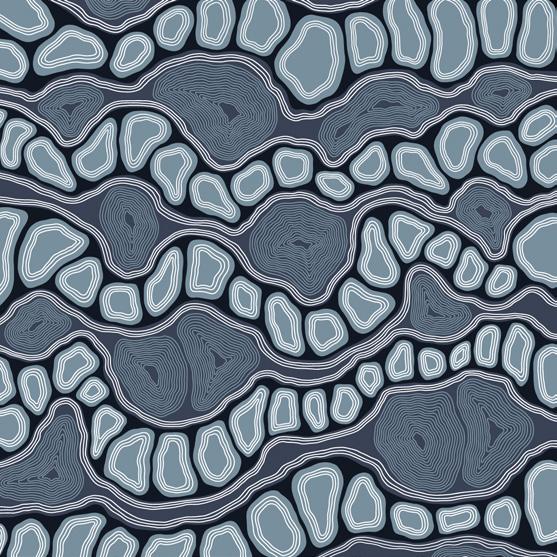

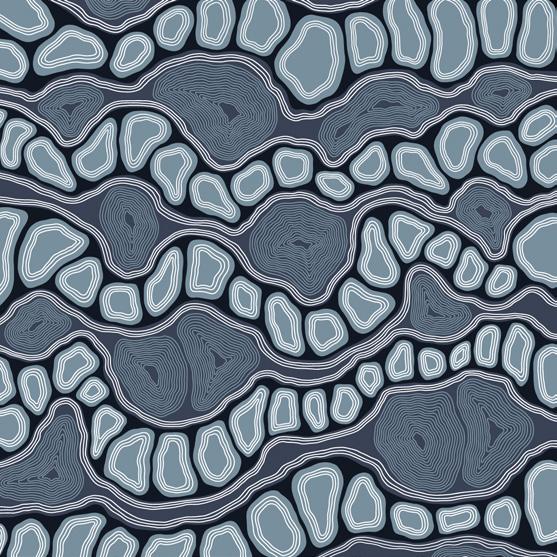

Importantly, it has been designed with a particular character – a ‘found space’ with a trapezoidal plan and intricate timber panelling that vividly depicts the trunks of Moonah trees from Wadawurrung Country. Sections of the floor are marked with circular motifs that reference the ochre Country and shoreline depictions developed through the co-design process with the Wadawurrung traditional owners’ group. These markings are both inside and outside, representing the constancy of Country in the face of transitory occupation. The balcony, designed as an insertion into the volume, is constructed like scaffolding: familiar, informal, a ‘found object’ in a ‘found’ room.

In a significant innovation, the Open House has the ability to open up to the street. It can function as a traditional black box space when the large sliding wall (an inner glass door and outer solid door) is closed. Alternatively, with the outer solid door open, the room is bathed in natural daylight, offering views in and out while preserving

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 26

sound insulation. Opening both the inner glass door and outer solid door allows the room to seamlessly connect to the plaza, merging with the street for events such as fairs, markets, festivals, and indoor/outdoor performances.

27

A makers market in the Open House with door open to the street.

Teatro Ofinica, Sao Paolo 1980-91 by Lina Bo Bardi.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 28

Cabaret

In the round Flat floor end-on with raised stage

Thrust stage

THE GRAND STAIR

The design of GAC embraces a crucial aspect of any night at a show—the experience of audience watching, a moment for both dressing up and dressing down. This includes the procession along the street to the venue and the journey within the building, creating opportunities for seeing and being seen.

GAC has two frontages: Ryrie Street and Lt Malop Street, the latter more than four metres lower than the former. The design reinstates the old ant-track between these two streets, allowing patrons to walk from one to the other. The level change is handled by a wide stair link in the tradition of halls and auditoria around the world. However, in this case, the inspiration for its treatment is more ‘fun fair’ than ‘grand stair’. The staircase is an integral element of the culture of strolling, encounter, and conversation that embodies the social gathering at the heart of what arts centres should be.

31

THE LEVEL 1 FOYER

GAC’s main foyer is not conceived as a service area, but as an exceptional space. During our design process, we conducted a comparative study of recent performing arts centre foyers. This investigation revealed that contemporary foyers had evolved into peripheral, auxiliary spaces related to the embodied performance space. They often took on an interstitial role and were mostly characterised by a lack of distinctiveness or character.

Lessons from pre-modernist theatres and concert halls illustrated the value of foyers as spaces in their own right. This concept enhanced the sense of arrival at a specific ‘place’ within the building, an important member of the parade of spaces that constitute the whole building.

The main foyer is designed with the atmospherics of a tent, referencing the tradition of the carnival and rendered with the theatricality of a stage set. It is designed to accommodate its

function as an audience gathering place pre-show or at interval. The space is, as with the entry foyer, fully equipped with rigging, lighting and AV/comms infrastructure for performances and parties.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 32

33

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 34

35

THE STORY HOUSE

The larger theatre in the new GAC is conceived with its origin as an end-on hall but developed as a highly flexible theatrical space. In standard proscenium setup it can house approximately 550 patrons but can be reset to house over 900 people. Unusual for contemporary theatre space of this size, it has two balconies within the volume, making it more like theatres of the 19th century in scale and visibility. It is compact and intimate, infused with a sense of energy and liveliness. The room boasts a state-of-the-art technical zone with fully equipped fly loft over the end stage zone. In addition, the floor is operable, with lifted sections and stepped wagons to

enable tiered-to-flat floor options. This level of equipment gives technical capability to the full extent of the house, which can be set up in a very wide range of operational types. The design process involved detailed studies of the range of anticipated uses. We believe that this space is the precursor to where new performance space is headed. Agile, fully equipped and just a remarkable space to be in.

37

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 38

Traverse

Cabaret Op 1

In the round

Cabaret Op 2

Gig Thrust

EMBLEMS AND SIGNS

A new cultural building should be a place that speaks to and embraces the community it serves; it should project a persona that embodies the cultural story of its existence, something curious and meaningful, in conversation with the community.

The GAC project is the product of a purposeful design process that reassembles emblems from Geelong’s past. The roof top is emblazoned with a traditional saw-tooth, factorylike canopy covering the rooftop bar. The concrete side walls along Aitchison Place are embossed with the modulation of the former historic Denny-Lascelles wool warehouses. The extensive co-design process with the Wadawurrung delivered a range of narratives represented throughout the building. The Moonah forest of the local coastlands is figured in the Open House theatre and the carpet patterning in the first floor foyer. Bunjil, the sacred Great Creator of the Wadawurrung and other Kulin

Nation clans, is acknowledged by the feather patterning of the balcony foyer carpet. Contemporary First Nations artists Gerard Black, Tarryn Love, Kait James and Mick Ryan have created works directly for the project. In particular, Kait James and Tarryn Love directly participated in the design of built elements – Kait in the exterior panelling of the upper levels, and Tarryn in the wall panelling of the Story House. A more detailed description of the Indigenous narrative and its manifestation can be found in other sections of this book.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES

Moonah tree and perforated panel design.

THE ENTRY — A CALLIOPE

Embedded in the Lt Malop Street façade is a golden entry portal. Its design recalls the ornate wagons pulled through towns with various animals and performers on display to advertise that the circus had come to town. Often the most ornate was that which carried the organ or the circus orchestra. GAC’s front door is such a wagon.

STREET FACE — THE BIG CURTAIN

Perhaps one of the most striking aspects of the building on Lt Malop Street is the front façade itself – a civic scaled rippling shape, a giant curtain. In 1900, the great French architect Henri Sauvage designed a pavilion for the Universal Exhibition dedicated to the pioneering modern dancer, Loïe Fuller. He created a building with a remarkable façade shaped like a giant drape, drawn up in the middle at the entry. It is simultaneously billboard and sculpture and has an astonishing presence.

The Geelong Art Centre demanded a similar yet contemporary signifier; a presence that manifests history and operation, something of wonder and unique to Geelong.

The creation of the grand curtain façade was inspired by theatre curtains, particularly the grand drape, as well as stage drapes and borders. Simultaneously, it symbolises the drapery of a tent, encompassing the drape, flap, and fly. The image of the curtain façade is readable at a distance, then up close it becomes abstracted, appearing as an undulating, dematerialised surface. The intent is to announce the theatre, the circus, the funfair –capturing the essence of anticipation and excitement that precedes a performance and spectacle.

41

Calliope, Great European Zoological Association street pageant 1874.

Loïe Fuller Theatre, France 1900.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 42

House curtain, Palais Garnier, Paris 1875.

Founders of New Circus/Circus Oz, Adelaide 1974.

PERFORMING ARTS BUILDINGS — TRENDS IN PERFORMANCE SPACES

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 44

Gavin Green Senior Partner, Charcoalblue

Erin Shephard Associate Director, Charcoalblue

Gavin Green Senior Partner, Charcoalblue

Erin Shephard Associate Director, Charcoalblue

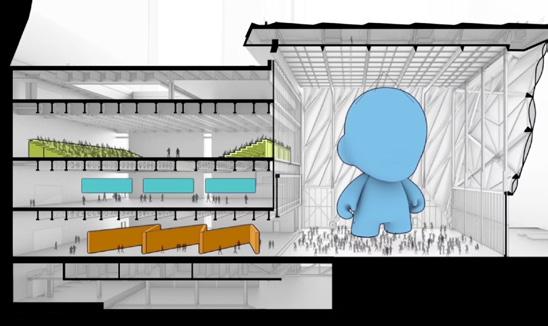

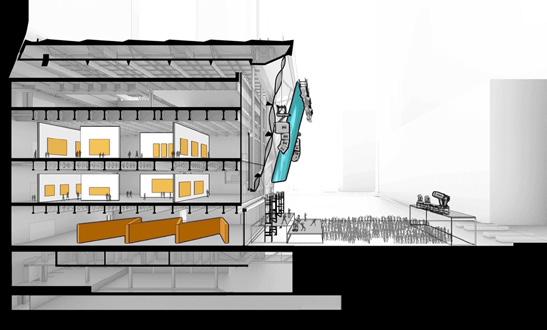

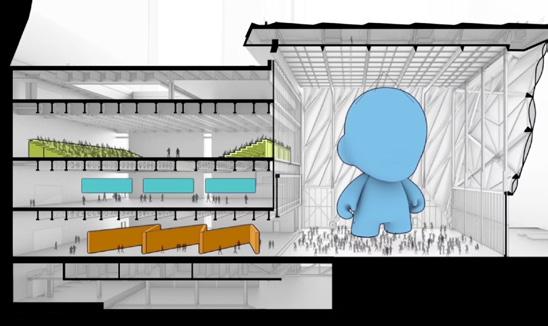

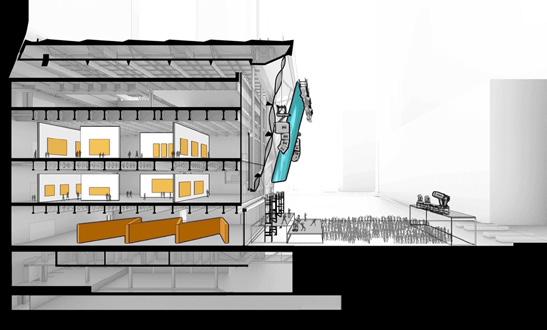

Geelong Arts Centre (GAC) is an exemplar building arriving at a critical moment in the history of theatre architecture. The building is opening its doors at the same time as two equally important arts centres on opposite sides of the globe: Perelman Performing Arts Center (PAC NYC) in New York and Aviva Studios in Manchester. These three spaces are considered together as they all share critical commonalities which are trending in performance architecture. They all explore how contemporary artists want to engage with audiences, how architecture can support flexibility on the stage and in the house, and, critically, how to give a performance building life and energy beyond a theatrical production.

Not long ago, theatre buildings were closed most of the day, only opening in the evening for a production. For some commercial venues this has not changed, however, we now recognise the importance and strength of the public spaces in theatre facilities. Beyond the artistic realm, these spaces often double as community hubs. They are designed to host a wide spectrum of events, workshops, rehearsal, lectures, film screenings,

and community gatherings, enhancing the cultural and social engagement of the communities they serve.

The best cultural buildings invite you inside. GAC isn’t the first theatre to open its doors all day long, but it does so with gusto: a welcoming front door invites you in to pause, buy a coffee, or listen to a piece of music or narrative. There are no barriers to entry, the public spaces are accessible to anyone. This sense of ownership is critical to the longevity of the performing arts, it invites the public back and builds the next generation audience.

Aviva Studios is a larger building on a very complicated site straddling a heritage rail line, yet the ground floor is light filled with an energetic vibe, it feels almost like a venue in and of itself. It speaks to Manchester, inviting visitors to the outside terrace to take a moment and enjoy free programming. In New York, the World Trade Center site is tight, visitors to PAC NYC are drawn to climb the entry staircase (or take the lift) by the powerful façade that offers only a glimpse of activity inside the theatre. Once inside, the public space is filled with life: a great bar, restaurant, a stage with daily free

45

performances, and information about more programming from welcoming staff.

These foyers offer a transition zone for those seeing a ticketed production. Aviva and GAC do the same as PAC NYC, there is an audience journey which changes scale as one moves from the threshold towards the auditorium. The journey builds the anticipation of the production or becomes part of the experience itself. What GAC does well is make the audience journey feel uniquely Geelong, the spaces are playful, vibrant, and don’t take themselves too seriously; it’s this nuance that draws you in.

Flexible theatres are the all the rage, spaces that can do everything all of the time. Theatres can be flexible while not compromising what they are there to do. The inherent fear is they become flexible like a sofa-bed (serving dual purposes poorly).

This trend is not wholly new but it is experiencing a renaissance, influenced by both those that present the work and audiences who attend. In today’s economic climate, the ability for venues to host a broader range of

events and attract diverse audiences translates into increased revenue, which, in turn, helps sustain and support the arts.

Today, audiences can immerse themselves in theatre set in a variety of environments, from pop-up venues to site-specific work, LED-clad environments (like The Sphere in Los Vegas) to more raw found spaces. The departure from traditional theatre configurations is influencing how performance buildings are designed. The artists who pioneered these immersive works are now influencing the next generation of theatre architecture and want more from their buildings. Flexibility allows artists to challenge convention and explore the blurred line between performer and spectator as interactive experiences gain pace alongside the integration of projections and digital effects to enhance storytelling and engagement.

Transformation inside our theatres is being reinvented. London’s Young Vic set the benchmark in the 1970’s, and then again with its rebuild in the early noughties. Today, only half the balcony is fixed, while almost everything else in the theatre can be adapted to each production. The rebuild design

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 46

Post-performance drinks in the foyer at GAC.

47

Flexible theatre space at PAC, New York. Image: REX

Flexible theatre space at Aviva Studios, Manchester. Image: OMA

team explored countless ‘what-if’ stage formats only to be surprised on opening night by a diagonal traverse – a room format not drawn by the architects or designers, but invented by the production’s creative team.

St Ann’s Warehouse in New York is a flexible theatre in a historic tobacco factory. Visiting work is restaged each time in differing formats and audiences are transported into the world of the show, yet they never lose sight of the original building. Within the constraints of the walls and technical bridges, anything is possible!

Flexibility can be taken to an extreme as in Dallas’s Wylie Theatre and New York’s The Shed, both include exciting technology but it comes at significant capital cost which is not always attainable. Australian

theatres continually work magic with lower technology but more flexible opportunities as in Sydney Theatre Company’s new home.

Spatial flexibility is also currently trending: Aviva Studios, the new home for the Manchester International Festival includes a gigantic columnfree warehouse for up to 5,000 capacity events, like music, immersive work and exhibitions. The warehouse can be divided in two or plugged into the adjacent 1,600-seat theatre, its opening show included a vast traverse dance stage with a standing audience each side, pumping music, lasers and a 30m-long flown LED screen. Similarly, PAC NYC has three interconnected rooms separated by pairs of acoustic doors and scene docks. There are some stage lifts to support changeover, but much is

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 48

The Warehouse at Aviva Studios by OMA.

moved by hand, even the large seating towers can be pushed around by hand with simple air-casters.

Flexibility ensures that the art drives the theatre format, not the other way around.

GAC has a perfect balance between flexibility and purpose. The Story House theatre feels a very focused end-on space, emphasised by the powerful elliptical geometry, yet the room can be easily transformed with simple lifts and wagons into thrust and traverse layouts. And, unbeknown to the occasional visitor, all the seats can easily be removed to transform the room to a flat floor configuration perfect for a vibrant live music gig.

Smaller supporting venues in an arts centre can offer even more avenues for creativity. GAC’s Open House is a triumph: the compact asymmetrical room is a space suitable for theatre, live music, circus, cabaret, and storytelling by the community and professional artists. Everything can be stripped back and it remains an exciting room in its raw state. The staging can be reconfigured, the

room’s orientation changed, and even one wall opened up to the adjacent plaza. It references the trends illustrated by PAC NYC, Aviva Studios, and the Young Vic, while establishing its own unique space for Geelong.

As the performing arts landscape continues to evolve, flexible theatre spaces have proven to be adaptable and sustainable solutions that cater to the changing needs and preferences of artists and audiences. These spaces embody the dynamic spirit of the performing arts in which innovation, diversity, and inclusivity are celebrated, thereby ensuring that live entertainment remains accessible and engaging for generations to come.

49

Layout concepts for The Shed, New York by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Rockwell Group.

WADAWURRUNG STORIES — TRANSCRIBED ORAL HISTORY

MATNYOO WADAWURRUNG DJA, WEEYA

BENGADAK MAEEWAN NGARRIMILI, KARREE BAA YEENG MOORROP

BENGORDEENGADAK DJA BAA NGUBITJ WARRI

THIS IS WADAWURRUNG COUNTRY, WHERE WE HAVE LONG DANCED, TOLD STORIES AND SUNG THE SPIRIT ON OUR LANDS AND WATERS

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 50

Dr David Jones

Professor (Research) in the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre at Monash University, and formerly oversighted all Strategic Planning & Urban Design activities for the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation.

A more detailed of this text is contained in Jones, DS (2024), Planning for Urban Country.

Djilang (Geelong) has long been the venue for song, dance, ceremony and art for the Wadawurrung People. Its unique juxtaposition between Corayo and Barwon, overlooked by Wurdi Youang, Anakie Youang and the Barrabuls, it possesses the spiritual qualities of a place endowed with multiple water resources, environments and animals, and especially Ancestors. The Geelong Arts Centre (GAC) project represents a significant respectful design that reinvigorates this past and continuing spirit. It brings the patterns and patinas of this living landscape into a platform for these activities and ceremonies to grow and nurture this evolving community into the future.

Architect Ian McDougall describes the GAC as having “its own identity which feeds back into its location. It’s telling … of the profound traditions of performance on the Wadawurrung site for thousands of years.” From the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation (WTOAC) representatives involved in this design journey, it was a delight working and talking with ARM Architecture especially in the successional workin-progress design presentations and conversations, where ideas were tested and teased around online due to Covid and face-to-face prompting WTOAC to offer many opinions and values. The latter also resulted in WTOAC driving the use of Language as text in the contemporary design (as quoted above), the talk of pastpresent-future, the engagement of artists, and also tabling ochre colours, passed Elders explanations and references to pre-colonial and 1830s-1850s events. Included were traditional stories of the lands, waters and day/night skies, animals including bats, Wadawurrung gatherings and dancings, and the colours of Moonah forests, local ochres, jarosites from Bells Beach and greenstone from Dog Rocks. All contributions that were listened to, respected, and eagerly enveloped as either prominent or subtle Wadawurrung design narrative clues into the internal and external design-making.

51

What unfolded from this co-operative co-design process was an integrated WTOAC-informed design narrative that told of the Geelong regional landscape in the flavours for floors, finishes, art, decals, lighting, ceilings, and cultural atmosphere that recognising both day and night activities. Possessing “a cohesive First Nations narrative from across every floor, the process of co-design has been extraordinary in terms of working so closely for a number of years with Wadawurrung Traditional Owners and other First Nations people on sharing and reflecting the narrative of this land as it has been for thousands of generations, so that’s amazing.”

Ground – Ochre Country:

The Mother Earth, Ochre, Texture, Air, Water, Trees, Chatterings and Acknowledgement of Country.

Level 1 – Moonah Forest Country: Inspired by Stories and Sounds.

Level 2/3 – Sky Country: Country of Bundjil and Balayang.

Forecourt – Ochre Country:

The Mother Earth, Ochre, Texture, Air, Water, Trees, Chatterings and Acknowledgement of Country.

Courtyard – Moonah Forest Country and Night Sky: Inspired by Stories and Sounds.

Central to the design was four horizontal levels/layers of Country translated into design layers. Each of the four levels evokes a different Wadawurrung creation narrative, with Earth and Ochre Country expressed at ground level, ascending to Moonah Forest Country, Sky Country and Night Sky on level four. These layers include:

Level 4 – Night Sky: Inspired by the Moon and the Stars Stories.

Little Malop Street Façade: Water Ripples at Waterholes, Night Sky Reflected in Windows.

Story House 550-Seat Theatre – Sky Country and Night Sky: The Crescent Moon, Bundjil and Balayang.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 52

From left to right: Kait James, Tarryn Love, Mick Ryan, Gerard Black, Kiri Tawhai.

53

These themes set the flavour for each floor but also ecologically united the day/night experience of the complex.

First Nations Peoples art installations were commissioned within and upon the new GAC to enrich this First Nations celebration. A co-design process, led by DV with ARM, GPAC and WTOAC, was involved in the design of the tender EOI brief, the jury selection phase, the journey in the construction and fabrication of the works including a special mentorship arrangement for an up-and-coming young First Nations artist. The successful EOI participants were Kait James, Tarryn Love, Gerard Black, and Mick Ryan.

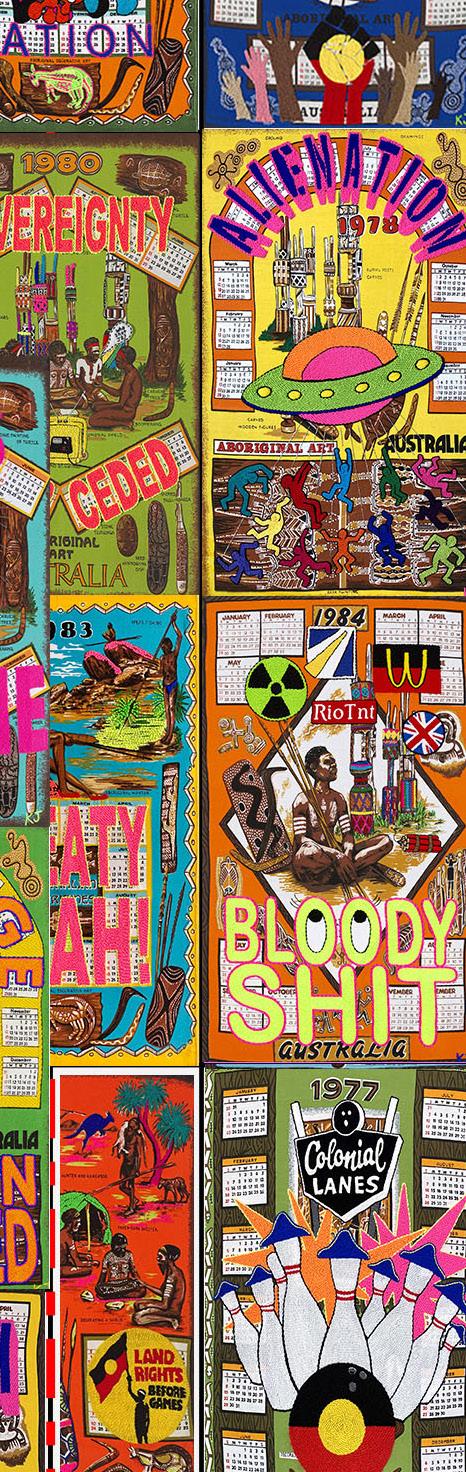

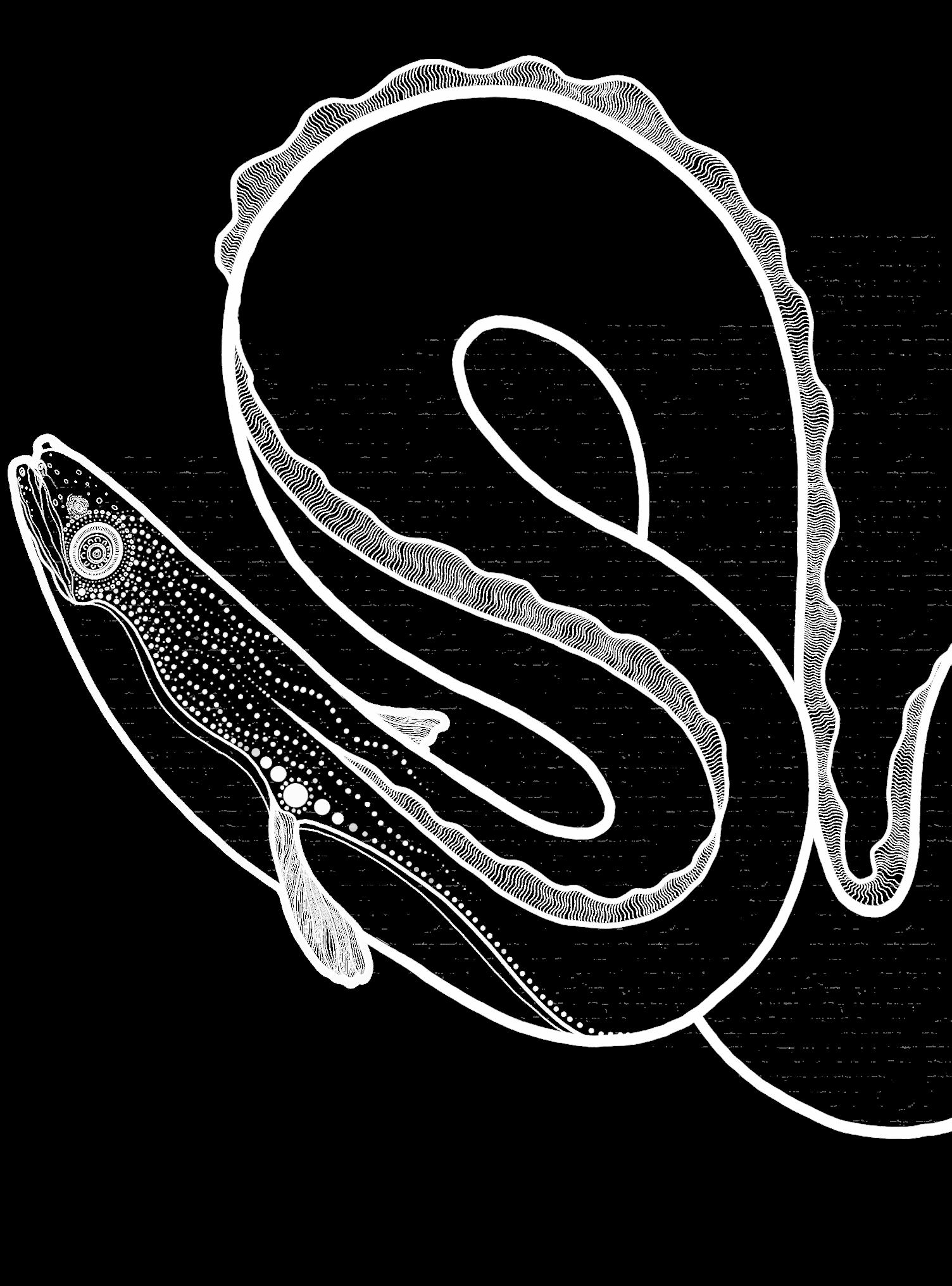

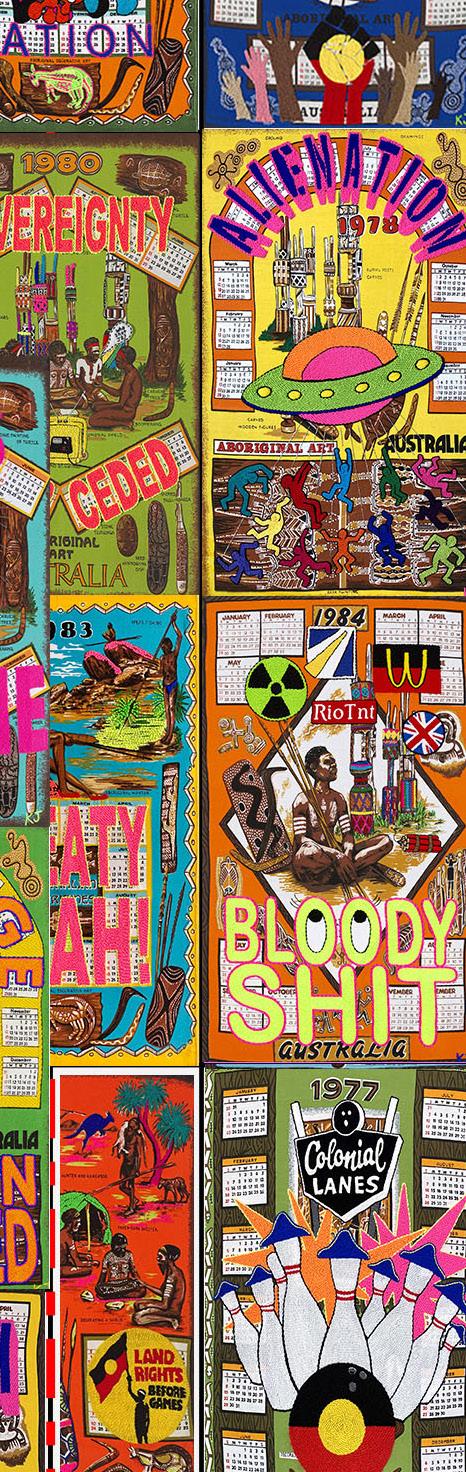

James carried forth her pop-culture passion using part of the facade as a huge art canvas to host 184 panels depicting Aboriginal Souvenir Tea Towels from the 1970-80s. Love’s art reflects the passing down of knowledge and language, which she aims to revive and reinvigorate her culture while exploring her identity, and it appears on the walls and panels of the 550-seat theatre, the Story House. Black’s work features intricate, geometric dotwork inspired by his connection to the land and ocean of the Wadawurrung, ancient art techniques and his birthing Country of Worimi, and his work appears as a mural in the café. Through music and performance, Ryan’s soundscape work seeks to share stories of the experiences and treatment of Aboriginal people in the region that people would not be aware of.

Additionally, while the external façade design is “inspired by Victoria’s early history of performance tents, circus and the tradition of stage curtains,” to the WTOAC the vertical and horizontal surface narratives talk of water; water pools, underground water rivulets, water cascading and aerating down walls, and water drips. This explains the Wadawurrung Language etched in Aitchison Place: “Water is living, come

and dance water, follow the journey and respect water. Ngubitj moorron, keembarne baa ngarramili Ngubitj, Kapa yaneekan-werreeyt baa ngubitj gonarra nyala goopma.”

In retrospect, McDougall, when asked what he loves most about the project, “[it is] the co-design process with Wadawurrung and the community engagement with First Nations groups on themes, which integrated First Nations culture into the building fabric in a meaningful and connected way … I think it is a remarkable collaboration between the First Nations groups and the technical team; a first for any arts centre in Australia.” To WTOAC, this project demonstrates that co-design of an architectural project is possible with a First Nations community; one just needs patience, respect, trust and lateral thinking.

REFERENCES

Crock, L (2023), Final stage of Geelong Arts Centre is a work of, and for, art, Bellarine Times, February 17. Available at: https://timesnewsgroup.com.au/bellarinetimes/realestate/final-stage-of-geelong-arts-centre-is-a-work-of-andfor-art/ , accessed 2 May 2023.

Geelong Arts Centre [GAC] (2021), Media Release: Creativity Unleashed. Available at: https:// geelongartscentre.org.au/news/creativity-unleashed/, accessed 2 May 2023.

Geelong Arts Centre [GAC] (2022), People of the Project: Ian McDougall. Available at: https://geelongartscentre.org. au/news/people-of-the-project-ian-mcdougall/, accessed 2 May 2023.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 54

55

From left to bottom right: Artworks by Kait James (cropped), Gerard Black (cropped) and Tarryn Love.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE INDIGENOUS ENGAGEMENT

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 56

Ian McDougall Co-Founder, ARMArchitecture

The Wadawurrung people have lived in the area they called Djilang, now named Geelong, for over 25 millenia, their presence acknowledged in the naming of the city itself, the streets and surrounding places; Gheringhap, Moorabool, Malop, Corio, and others. The Geelong Arts and Cultural Precinct, the site of the Geelong Arts Centre is centred on a former waterway and wetland deeply significant to the Wadawurrung.

The project to rejuvenate the Geelong Performing Arts Centre began with the 2003 Strategic Plan. ARM was commissioned in September 2019 for the third, final and largest stage of the rejuvenation. While the previous stages had little to no engagement with the traditional owners, by 2019, GAC were actively involved with local Indigenous people and culture, however there was no sense of how this collaboration would continue into the development of the building.

Artwork by Gerard Black. 57

Artwork by Gerard Black. 57

INTENT

At the earliest time, both GAC and the design team made it a goal to ensure the new facility would express the nature and continuous history of its place, Djilang/Geelong. It is normal practice for us at ARM to generate project design strategies that narrate local stories, which includes the indigenous by beginning to discuss what the building might be, this early, meant that the discussions with the Wadawurrung and the suspension of design resolution until such discussion had happened, afforded considerable agency of the narrations in forming the core character of the new facility. We believe public buildings have a responsibility to engage (and contend) with the cultural ethics and values of their community. Nowadays in Australia new buildings need to be part of the ongoing acknowledgement of and reconciliation with Indigenous communities. GAC and the project team made that commitment to amalgamate, in equal emphasis, Indigenous and post-settlement histories. An interesting challenge in undertaking this commitment was the change in mindset required of the architectural team. We have come to realise the need to share the navigation of the design thematic of the project – an act more akin to dressmaker than auteur.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 58

Kait James panel prototype. Installation of panels.

PROCESS

A successful collaboration requires a fair and ongoing process of discussion, creation and agreement. The design team with GAC and with Development Victoria set in place a formal structure guided by a nominated facilitator in late 2020. The design team and Wadawurrung representatives formed a working group, established a schedule of workshops and meetings, round tables of talk and design action. The working group began in February 2021 with traditional owner representatives, Corrina Eccles, a Wadawurrung woman and lead from the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, David Jones, consulting facilitator to WTOAC, as well as Indigenous artists and other WTOAC members. This process continued actively through 2021.

A narrative armature was developed for the whole building, thematically focused on the Wadawurrung sense of the land and cosmos of Djilang. This group identified a process for spaces and areas to be codesigned with selected Indigenous artists and designers and the design team.

The second phase of the procedure began in June 2021. First expressions of Interest, then appointments, as selected by a small panel of Wadawurrung representatives, First Nation advisors, architects and government team members. It was crucial that local Indigenous were among those selected but so too wider Indigenous participants.

Development Victoria and the lead contractor Lendlease streamlined the appointment process by using shortform contracts and practical terms of engagement for the artists. This meant that more candidates would respond to the EOI and that artists not necessarily experienced in making buildings would have the confidence to sign up for the complex process to integrate their designs into built fabric.

59

Artwork by Tarryn Love.

THE EXTRAORDINARY

The new GAC Stage 3 rises through four main levels, each of which carries themes of the Wadawurrung natural world: Ground Level is Ochre Country; L1 is Moonah Forest Country; Balcony Level is Sky Country; and Roof Top is the Night Sky. Working with the Wadawurrung group leader to design motifs through the whole building, the foyer carpet on L1 carries Moonah tree patterning, as does the wall panelling in the Open House. The plumage of the great creator spirit, Bunjil, is depicted in the Balcony Level carpet. In the Story House, local artist and Gungitjmara Keeray Wurrung woman Tarryn Love created a grand narrative painting that was translated into the blue panelling, and Kait James, Wadawurrung artist, created artwork for the exterior panelling covering the upper levels of the building. At the café on street level, Worimi artist Gerard Black prepared a three-dimensional work for the wall, and musician/ artist Mick Ryan, a Ngarrindjeri/ Gunditjmarra man, created an acoustic work that will play in the courtyard and linkway between Stages Two and Three of the GAC. Finally, depictions of Ochre Country and coastal themes are embedded in the small plaza and laneways surrounding the building.

The outcomes are extraordinary in both the quality of the designs and the commitment to an equal depiction of Indigenous and post-settlement culture. The explicit Indigenous presence in the making of a place means it is profoundly of Djilong/ Geelong. That presence blends with the traditions of architectural language, creating a ‘gallery of meaning’, acknowledging the continuous history of the city and its people.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 60

61

CO-DESIGNING COUNTRY

Sam Rice Associate, ARM Architecture

ARM Associate Sam Rice reflects on his collaboration with Indigenous artist Tarryn Love designing the acoustic panelling that adorns the walls of the 550-seat Story House theatre at the Geelong Arts Centre.

The ARM team first started working with Tarryn during one of Melbourne’s lockdowns in 2021. Meeting virtually, we were six small faces on a screen, surrounded by either our bedroom clutter or the tidy artifice provided by one of those generic backdrops. Each of us began by sharing the Country we were speaking from and what our role on the project was. We were meeting Tarryn to commence a collaboration on the interiors of the 550-seat Story House theatre, the largest theatre within the new Geelong Arts Centre.

At that time, I hadn’t been to site because of the persistent lockdowns, but I’d been spending hours building a 3D model of the major theatre and was intimately aware of the curve and rise of the seating plats, of the mechanical service ducts running behind the walls, of the depth of the balcony fronts.

Tarryn spoke of her connection to Country, of her Gunditjmara Keerray Woorroong heritage and growing up on Wadawurrung Country, of her studio at Platform Arts, which is next door to the Geelong Arts Centre site, and how she had been watching out the window during those interminable pandemic months as the site was cleared, holes dug and the building emerged. She told us stories of how she felt on Country, of land and sky and ‘night Country’, and of time.

We listened.

We spoke of our experience with theatres and architectural scale. We described the acoustic requirements of the surfaces that we were to co-design with Tarryn and how perforations can make imagery in architectural treatments. We spoke of the scale of the room, of patrons’ relationship to the walls on which Tarryn’s artwork would be realised –sometimes close, sometimes far. At times lit, at others not.

The process of co-design in the Story House continued in this manner. Each participant brought special and particular knowledge to the table and listened to and acknowledged the expertise of the other. Tarryn began with line-and-fill artworks which responded to the wider project narrative that was developed by the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners. Spanning the theatre’s three levels, the artworks explored her connection to her Ancestors, the ‘river’ of the Milky Way, and the stars of the night sky. The nature of the room required the images to be continuous, horizontal and modular, changes Tarryn quickly accomplished. When we produced an image of an early design mapped onto the walls of the theatre, Tarryn realised that the possum skin cloaks of the Ancestors on the lower level could be made life-size, and their presence directly adjacent to the stalls entries would be felt by all who came in those doors. The interactive exchange of

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 62

Artwork by Tarryn Love.

36mm grid

Hole sizes: 12, 18, 24mm dia

Panel perforations comparison.

40mm grid

Hole sizes: 12, 20, 28mm dia

44mm grid

Hole sizes: 12, 22, 32mm dia

Wall panels indicative view.

63

constraints and opportunities, explored collaboratively, integrated the narrative artwork into the still digital space of the theatre. This seamless integration made decisions straightforward, and serendipities felt perfectly aligned.

As work returned to the office, we had the opportunity to get those six people from the first online meetings in the same room, to look at 1:1 scale prints of Tarryn’s artwork transferred to different perforation patterns. For all of us – ARM, Tarryn, Development Victoria and Lendlease – it was that magical moment when architecture scales up from the screen to the real world. We compared points with slots, rectilinear grids with diamond ones, four sizes of perforation with five. We looked at them standing on the other side of the room and with our noses pressed up against the sheets. Some of us had done this before, but we were all equally excited to see Tarryn’s stories at building scale.

A few months later, we convened again. This time in the concrete expanse of the Geelong Arts Centre construction site, to see the first prototypes of the panels on the wall. This was another shift in understanding, as we saw the work

with the thickness and texture of timber. But there were only nine panels – they looked lonely.

Finally seeing the complete set of more than 500 panels installed in the Story House sometime later was a revelation. Tarryn’s artwork has an enveloping quality, readable at multiple scales and capable of being grasped in its entirety from across the room. It elicits a personal resonance as you walk alongside it, creating a palpable connection.

It was a privilege to be involved in the transcribing of Tarryn’s artwork from sketchpad to theatre wall. The success of the Geelong Art Centre’s engagement with First Nations artists is resonant when you realise that in this room of stories, it’s Tarryn’s story of Country that we see first, and last.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 64

Tarryn Love panel, prototype.

65

Gerard Black's artwork being fabricated offsite.

Gerard Black's artwork being fabricated offsite.

I FEEL WELCOME HERE: A BUILDING THAT CELEBRATES ITS PLACE, COMMUNITY AND CULTURE

Jeremy Stewart Principal, ARM Architecture

ARM Principal Jeremy Stewart reflects on the co-design process with the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation (WTOAC), which provided a defining narrative for the design of the Geelong Arts Centre (Stage 3).

The Geelong Arts Centre project presented a rare opportunity. A regional arts centre of this scale is a generational chance to revitalise an existing theatre community, attract new audiences, enhance the current arts precinct, and introduce modern, flexible venues that are easy to operate and equipped with contemporary theatre technologies.

The briefing documents emphasised that the project aimed to address 'threshold anxiety'—the discomfort people experience when entering arts venues—by creating spaces that are welcoming for both performers and patrons. This was to be more than a typical arts centre; its vision was to engage and provoke the community, enticing and exciting them. A pivotal aspect of this community engagement was the co-design process with the Wadawurrung, which provided a defining narrative for the project.

As noted in David Jones’ essay in this book (page 50), the site and its surroundings have been a performance space for the Wadawurrung peoples for tens of thousands of years. This history had been obscured, with the original waterways paved over and gathering spaces transformed.

Our initial meeting with the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation (WTOAC) included four participants:

Wadawurrung Elder Corrina Eccles, Deakin University academic David

Jones, Ian McDougall, and myself. Development Victoria and the Geelong Arts Centre (GAC) concurred that presenting the ongoing work to a small, select group—who would serve as primary contacts throughout the project—was the best approach for fostering an open relationship. The presentation was held in a compact meeting room at the WTOAC offices in Geelong. It covered the general layout of the venues, detailed plans of the theatres, the concept of a campus-style arrangement with a central courtyard and forecourt, a site section illustrating the simplified pedestrian route through the site, and architectural inspirations, including the draped façade and the use of 'sets' to define spaces within the Centre.

There was a great deal of information to absorb. Corrina and David listened attentively and inquired about the opportunities available within the space. Corrina observed that the draped façade evoked images of cascading water. We agreed to reconvene in a couple of weeks, allowing Corrina and David some time to reflect on the information presented.

The follow-up meeting proved crucial for the project. The diagram we discussed earlier, which reimagined different aspects of Wadawurrung Country, became the cornerstone of our design narrative. This conceptual shift defined the building as an extension of the Country itself, guiding design decisions throughout the Arts Centre. The façade was reinterpreted to represent cascading water, which

67

flowed down to ochre Country, shaping the landscape design by TCL. This motif of water extended into the surrounding streets, echoing the waterways that once permeated the area, and spilled into the building through the Little Malop Street entrance and at the forecourt entry to the Open House, thereby integrating elements of the Country into the structure.

Additionally, the development of this narrative facilitated discussions on various potential sites within the centre for artworks by First Nations artists. This dialogue ultimately led to the engagement of four artists—Kait James, Tarryn Love, Gerard Black, and Mick Ryan—who were commissioned to create works for the project. Inside the ARM office, the momentum and creative energy were palpable as we moved forward with these enriched design elements. Staff were assigned to work directly with the artists to assist them in translating their works into the architectural fabric of the centre.

The development of the artists' work was facilitated by the appointment of an artist liaison, Kiri Tawhai, who ensured a culturally safe environment for the artists, assisted with contractual matters, and provided guidance and support. The process of integrating artistic work into the architectural fabric varied depending on the artist and the complexity of the piece. For instance, incorporating Tarryn Love’s artwork involved extensive coordination with theatrical, acoustic, services, and structural consultants—a complex task that resulted in the production of over 500 custom panels. This collaboration between Tarryn Love and Sam Rice is detailed in Sam Rice’s essay (page 62).

“It's deeply meaningful to see my culture and heritage embraced and celebrated at Geelong Arts Centre. This opportunity not only allows me to share my artistic vision but

also serves as a powerful statement of recognition for my art and its significance in contemporary society. Seeing my work finished and displayed at scale, and knowing that it will inspire and resonate with the community and visitors for generations to come, is really special."

— Gunditjmara Keerray Woorrong artist, Tarryn Love

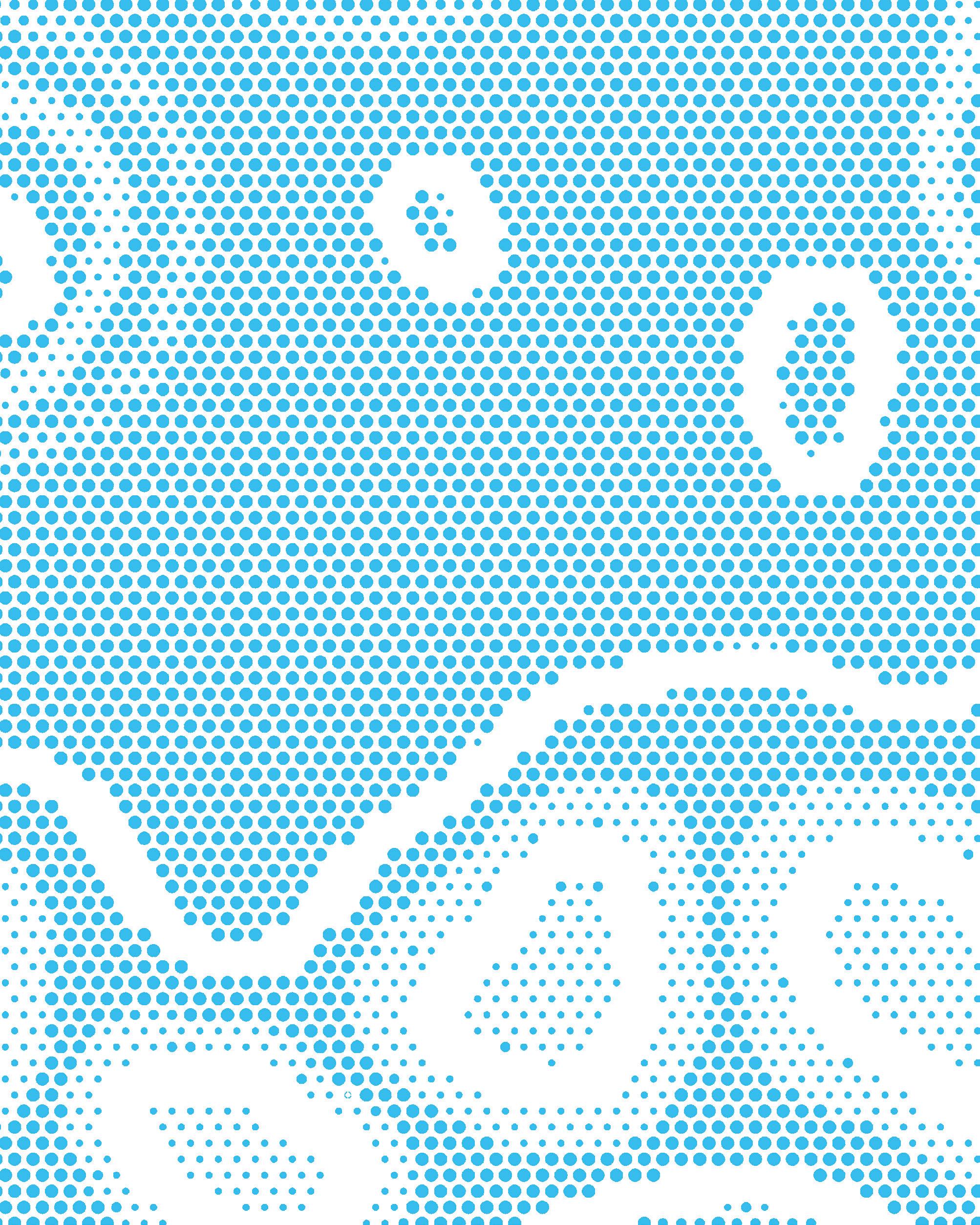

Kait James's work was inspired by Aboriginal souvenir tea towels from the 1970s. The design included 193 façade panels based on 23 individual designs. As the artworks were pre-existing and had already been photographed, only very minor alterations were necessary. This, combined with their placement on the façade, allowed for a straightforward translation from artistic work to architectural facade. ARM provided Kait with an unfolded elevation that enabled her to position her work on the façade. Kait would then return the file, and ARM would update the panels in the 3D model. Following this, updated images of the 3D model were emailed to Kait for her review. Once Kait, the Geelong Arts Centre (GAC), and Development Victoria (DV) were satisfied with the design arrangement, two full-scale colour samples were printed to verify that the print quality, colour reproduction, and resolution matched the original works. After some minor adjustments, the final panels were printed and installed on the façade.

When unveiled, the panels surpassed our expectations, creating an enigmatic pattern visible from Johnstone Park and Little Malop Street. This transformed into vibrant, detailed pieces when viewed from within the central courtyard. Reflections of the panels in the reflective glazing of surrounding buildings added an unexpected layer of complexity to the installation.

GEELONG ARTS CENTRE –DIRECTIONS FOR 21ST CENTURY ARTS CENTRES 68

Ground Level narrative image, Ochre Country (Point Addis, Wadawurrung Country).

Façade narrative image, water ripples at waterholes.

Gerard Black's work draws inspiration from his experiences growing up on Wadawurrung Country and his walks along Spring Creek with his son. Located in the Little Malop Street café, his multilayered piece follows a similar process to Kait's, with Gerard working from unfolded elevations that were then reincorporated into the 3D model. Updated images were returned for review, and the process became highly efficient, allowing the design to be updated several times a day.

Gerard's artwork consists of several layers, including a complex threedimensional rear layer that required precise routing and integrated lighting; as a result, several prototypes were produced. The final piece was fabricated offsite and then swiftly installed onsite. From the street, the rear surface appears subdued, with a backlit eel design prominently displayed. As viewers approach, the surface transforms to reveal a brightly coloured, highly textured finish, with the eel visually receding, creating a dynamic interplay between viewer perspective and artwork detail.

“Creating this work has provided me with a platform to further embrace and share my culture. I’m excited for visitors to Geelong Arts Centre to get up close and personal with the work, fall in love with the eel, and the stories of my culture."

— Worimi artist, Gerard Black

Mick Ryan's piece, a soundscape inspired by the Moonah Forest, was initially intended for the Little Malop Street forecourt. However, it was relocated to the central courtyard to ensure that the intricate composition would not be overwhelmed by traffic noise, providing a more suitable space for people to sit and contemplate the work.

The completed soundscape features a diverse array of sounds and instruments, including guitar,