Introduction

About ARK︱Something went wrong. And is going on... by Victoria Stepanets

Interview︱ Shape Shifter: writer Yuna Goda interviews airtist Noe Iwai

Review︱In-Betweenness: The Space Where Truth Lies by Yenah Kim and Zofia Kierkus

Review︱ Claudette Johnson: PRESENCE Review

Claiming a rightful place in the history of contemporary art by Nicole Moore ArtNews Memoir ︱ Unwittingly an Outsider, Enchantedly an Insider by Soyeon Jung

4 6 14 20 24 38 42 44 ART GALLERY

About Ark Talks

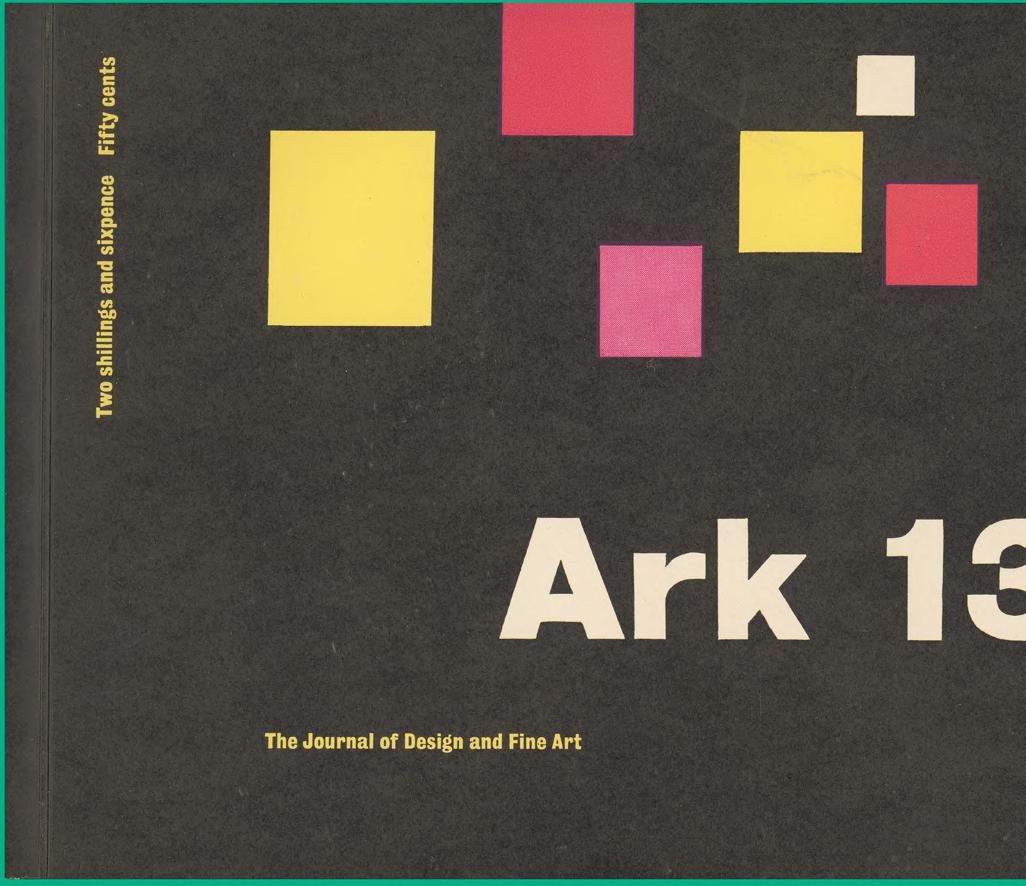

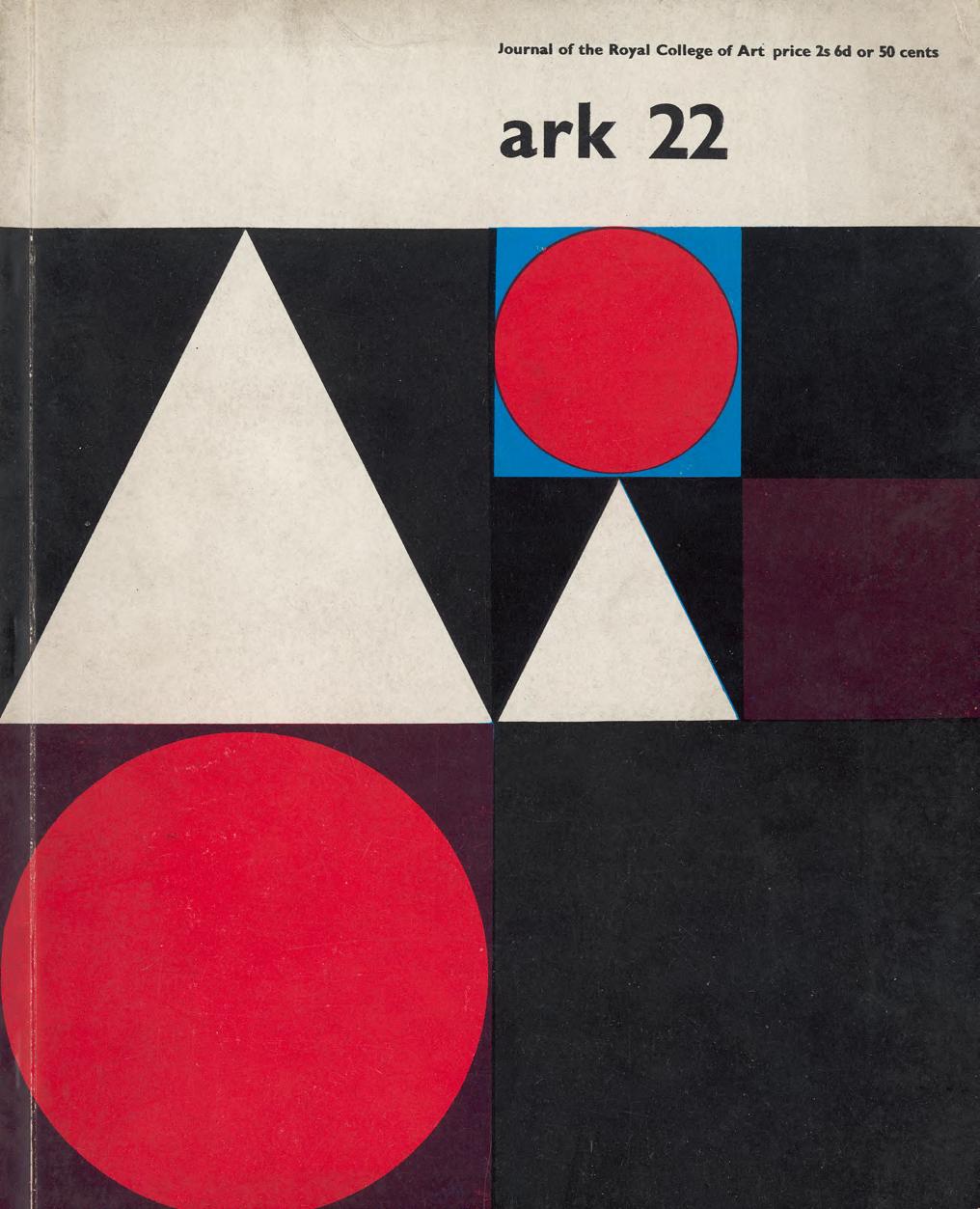

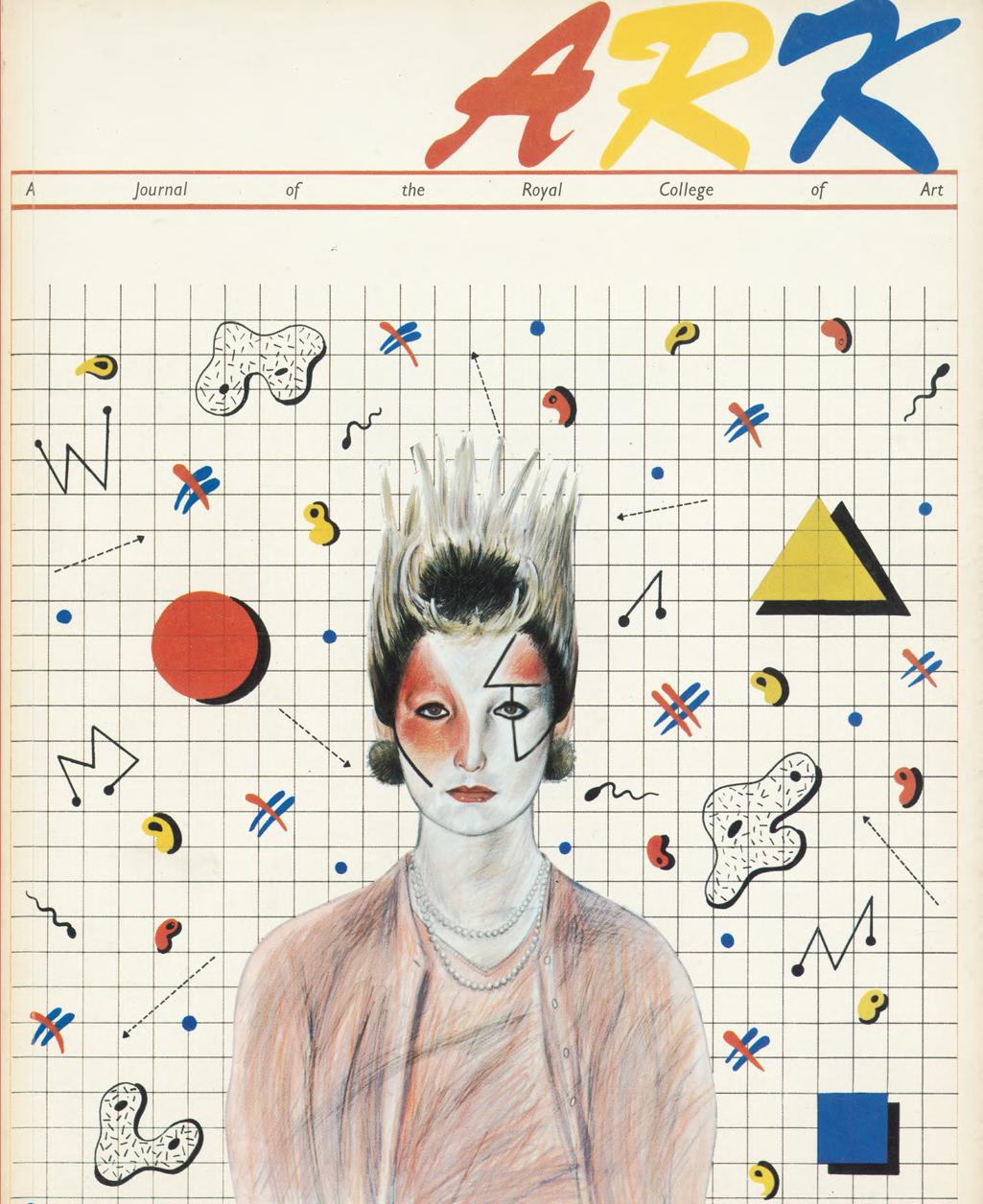

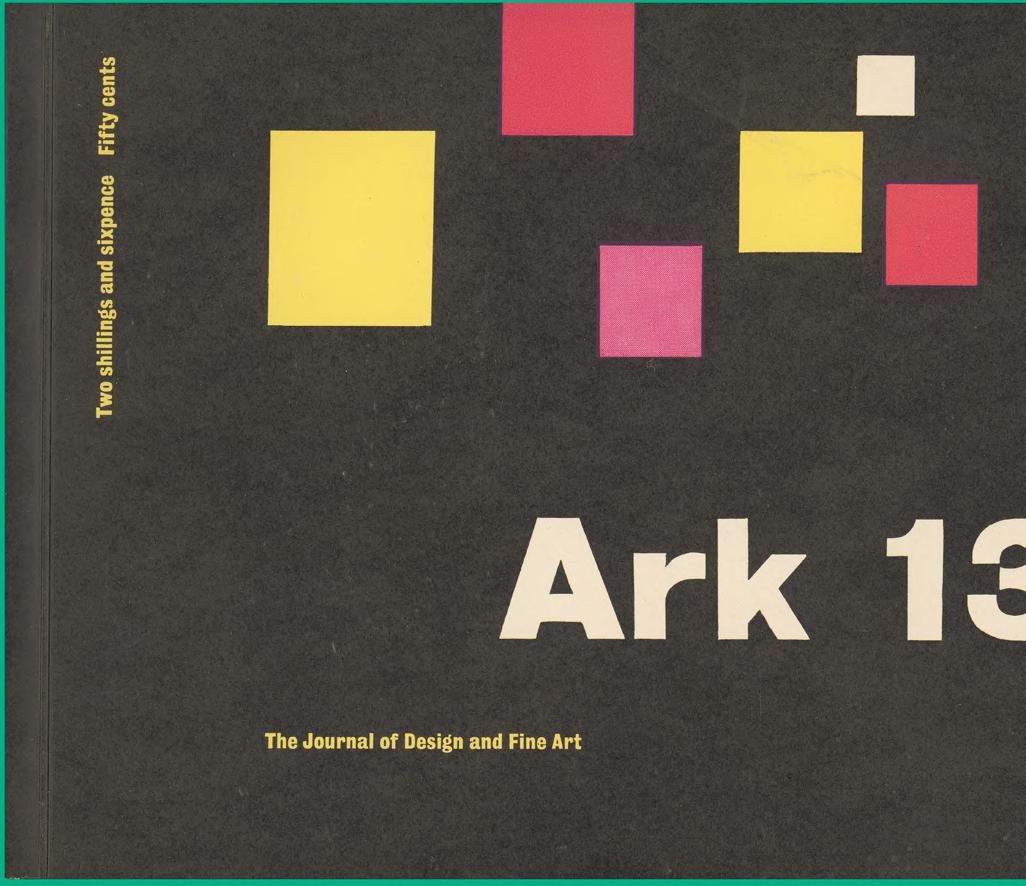

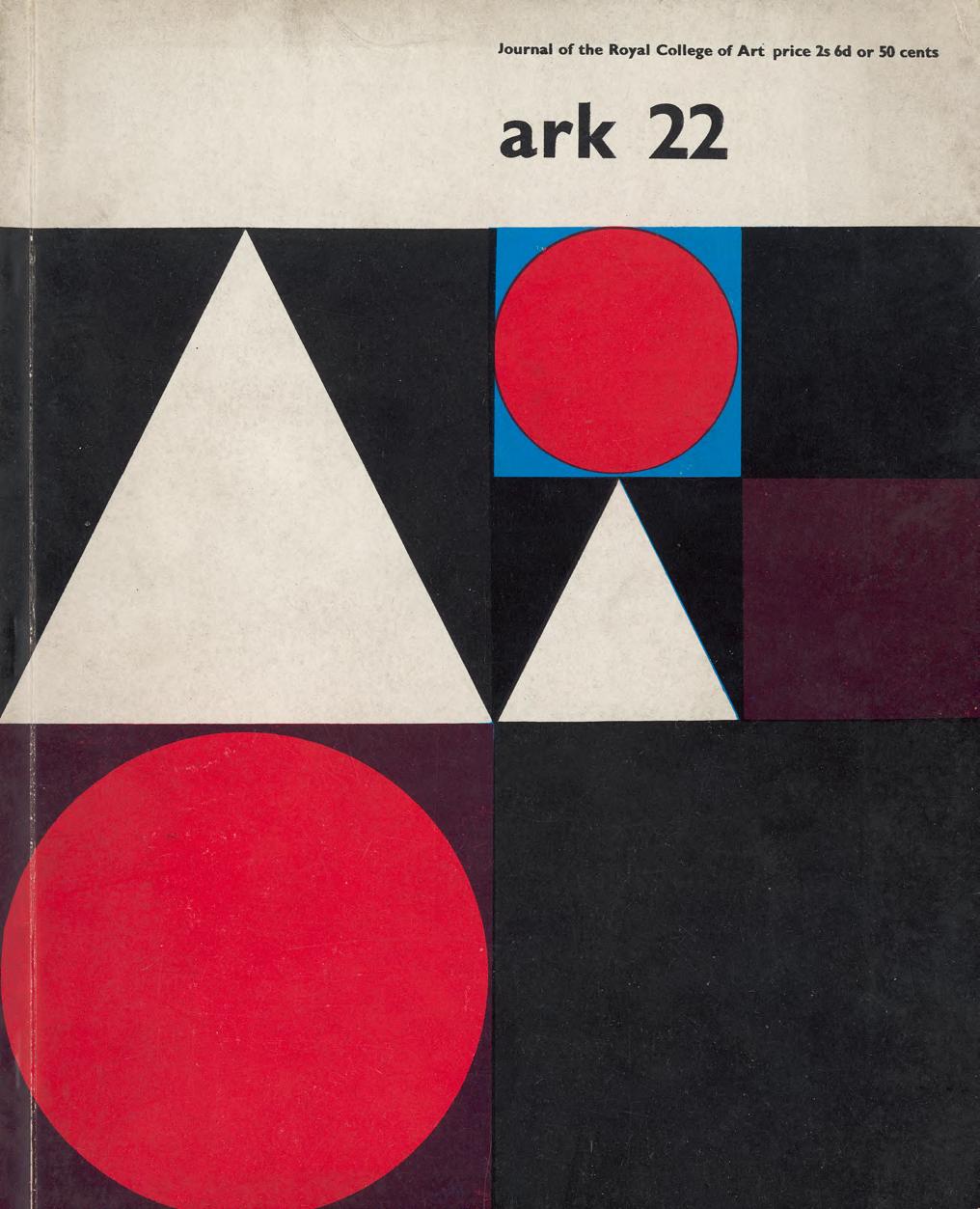

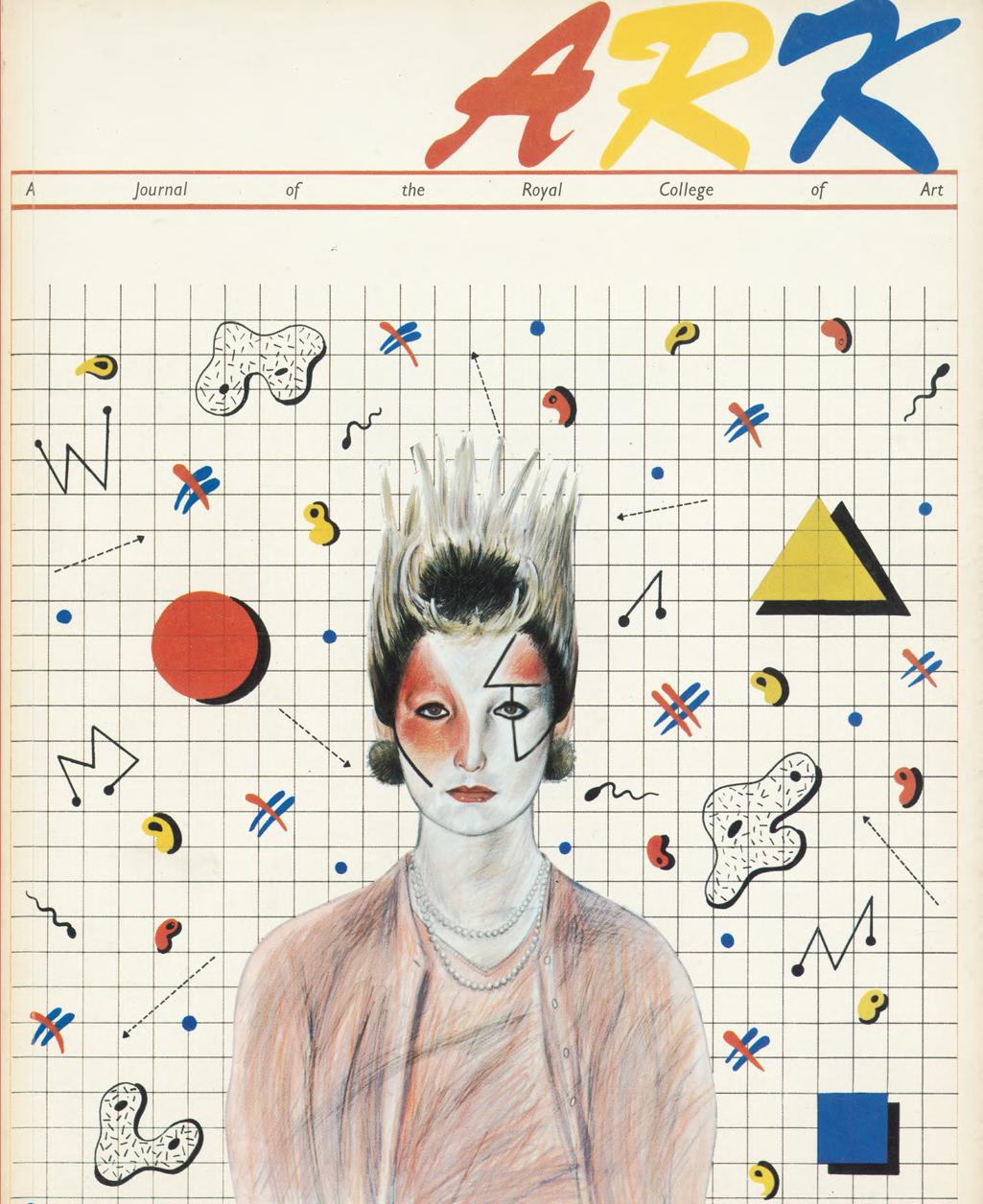

ArkTalks aspires to revive the spirit of the ARK magazine, which was run by students at the Royal College of Art from 1950 to 1978. Born out of a student initiative, ARK evolved into one of London’s most recognized art magazines shortly after its inception, featuring contributions from luminaries such as Ralph Rumney, Lucio Fontana, Alison and Peter Smithson, among others. ArkTalks inherits the distinctive qualities of this historical publication, as a student-run magazine filled with art and writing enthusiasts and celebrates its enduring resonance even after more than five decades. Drawing inspiration from ARK’s profound exploration of social context and its impact on art, our magazine engages artists, critics and curators from diverse backgrounds and nationalities. We invite them to ‘talk’ to us, interweaving their unique experiences and viewpoints within the thematic focus of each issue. These dialogues are to celebrate personal narrative in art and underscore art’s capacity as a unique language capable of delving into realms far beyond the limitations of verbal communication.

As you hold our inaugural edition in your hands, you are partaking in a momentous occasion of the revival of ARK. As you hold our inaugural edition in your hands, you are partaking in a momentous occasion of the revival of ARK and we are delighted beyond words to invite you to explore the richness and depth of art through our eyes. We are delighted beyond words to invite you to explore the richness and depth of art through our eyes.

4

On ‘in-between-ness’ and liminality

The polarizing nature of the binary system pits good against evil, sense against sensibility, us against them. Its culmination in conflicts and wars reveals its inherent violence evident across the globe and throughout history. This inherent violence also manifests within ourselves when the internalized notion begins to pressure us into finding a cohesive self that aligns with one extreme or the other. Most regrettably, it deprives us of experiencing the nuances between extremes and the myriad of realities that transcends our perceptions of the world.

Many influential minds have turned to this liminal reality, introducing a fresh lens through which we perceive the world and navigate life’s complexities. Liminality, namely the state of being in-between physically, emotionally, and metaphorically entails ambivalence, often leaving one feeling disoriented and vulnerable as it defies fitting into one end or the other. This is our world of in-between. It is a realm of contraries and complexities, where the boundaries of understanding blur and truth remains elusive.

Perhaps you’ve experienced the conflict of inner selves–feeling both like a kid at heart and an adult by age, experiencing and inflicting hurt, torn between creativity and practicality, or of your social and cultural selves. While the notion of ‘in-between-ness’ may resonate differently with each of us, we have all found ourselves in

these liminal spaces, deeply contemplating which version of ourselves to embrace, at last resigning the rest with bitterness. It is here, in these liminal spaces, that the inspiring minds have discovered the transformative potential, as they create a condition of ambiguity.

Given complete freedom in the vast pool of existence, it is within this ambiguity and potentiality of liminality that individuals undergo profound shifts in identity and worldview, akin to the essence of art itself. It is also within this parallel that we have chosen liminality as the theme of our inaugural magazine edition. We seek solace in art, using its power to unveil the multiple truths and realities, thus expanding our horizon of the world and enriching our existence beyond its earthly experience.

As you flip through the pages, you’ll encounter reflections of our experiences of ‘in-betweenness’ from various angles. We have gathered artists across disciplines, curators, writers to see how 'in-betweenness' manifests itself in different spheres of activity, collectively constituting the sphere of Art. May you find yourself traversing the liminal spaces of thought and emotion within these pages. Through the exploration of art and the contemplation of existence, may your inner journey be as profound as the destinations we seek.

by Soyeon Jung

Something went wrong. And is going on...

VICTORIA STEPANETS

‘It is sometimes said that there is no such thing as good or bad design, that it has no real measurable standards, that it is, in fact, just a matter or personal taste. But it is readily accepted that there is a standard of, say, honesty, or driving, or housing, so why not one of design?’ Let’s replace the word ‘design’ in this quote by Gordon Russel with ‘art’ - it fits well, doesn’t it? That’s all about blurring boundaries. When every artwork can be ‘good enough’ even if it is terribly bad. But how can we prove it when there are no quality standards? When any art can be perceived as ‘good’

- is it a freedom, or a substitution of concepts that penetrates very deeply into the subconscious and washes away all prerequisites for the development of ‘good taste’? We live in a city where no right answers exist - where everything ‘can be right.’ That’s why we are not trying to give any responses - we just want to provide one story. A great story, we believe.

This article is about ARK - a printed issue which was launched by RCA students in the middle of the last century. In a very short time, it became one of the most valuable art magazines in London.

6

By this example, we are aiming to raise awareness of the meaning of a 'quality magazine', highlighting and analysing how and why this experience is still worth sharing today.

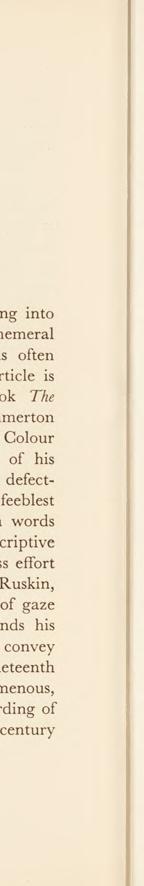

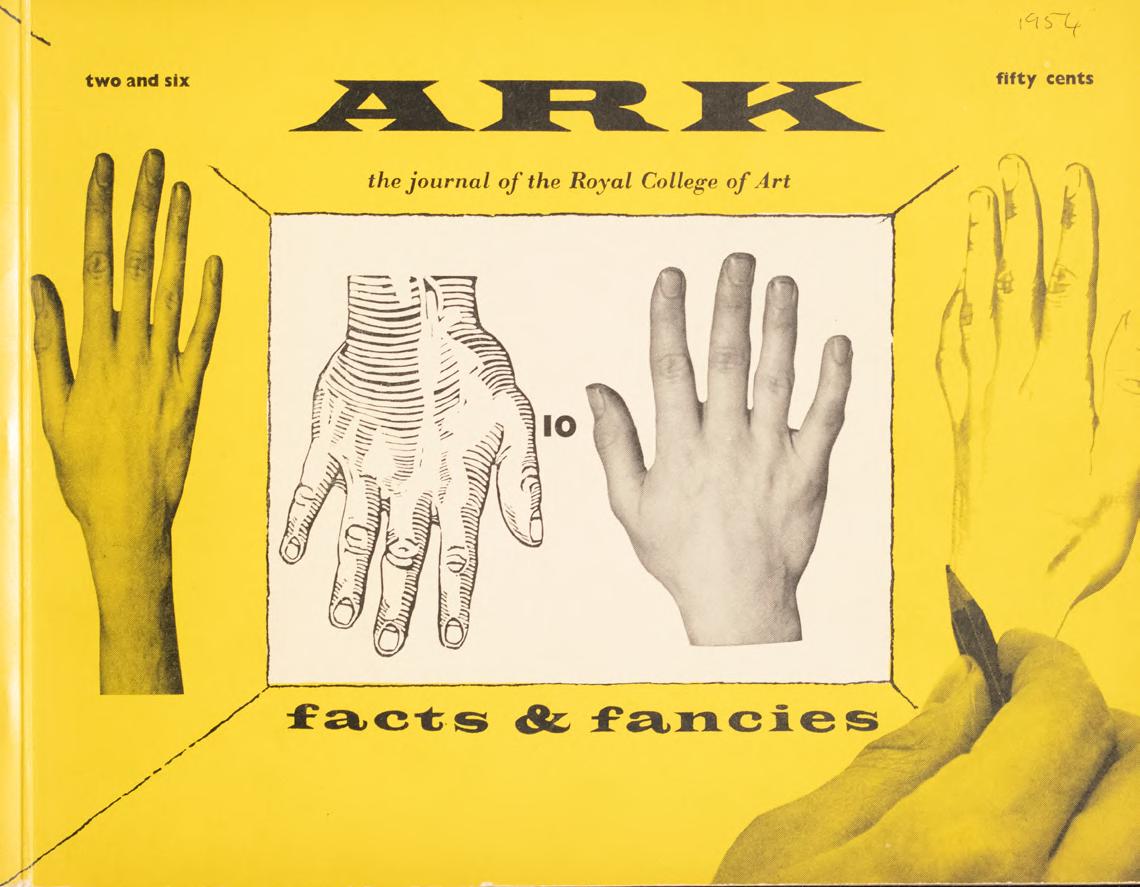

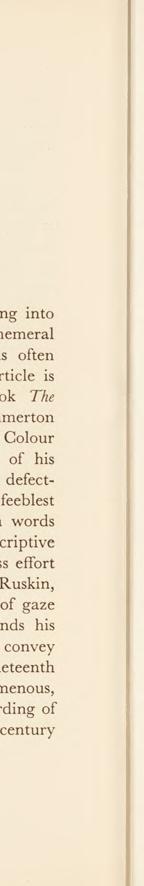

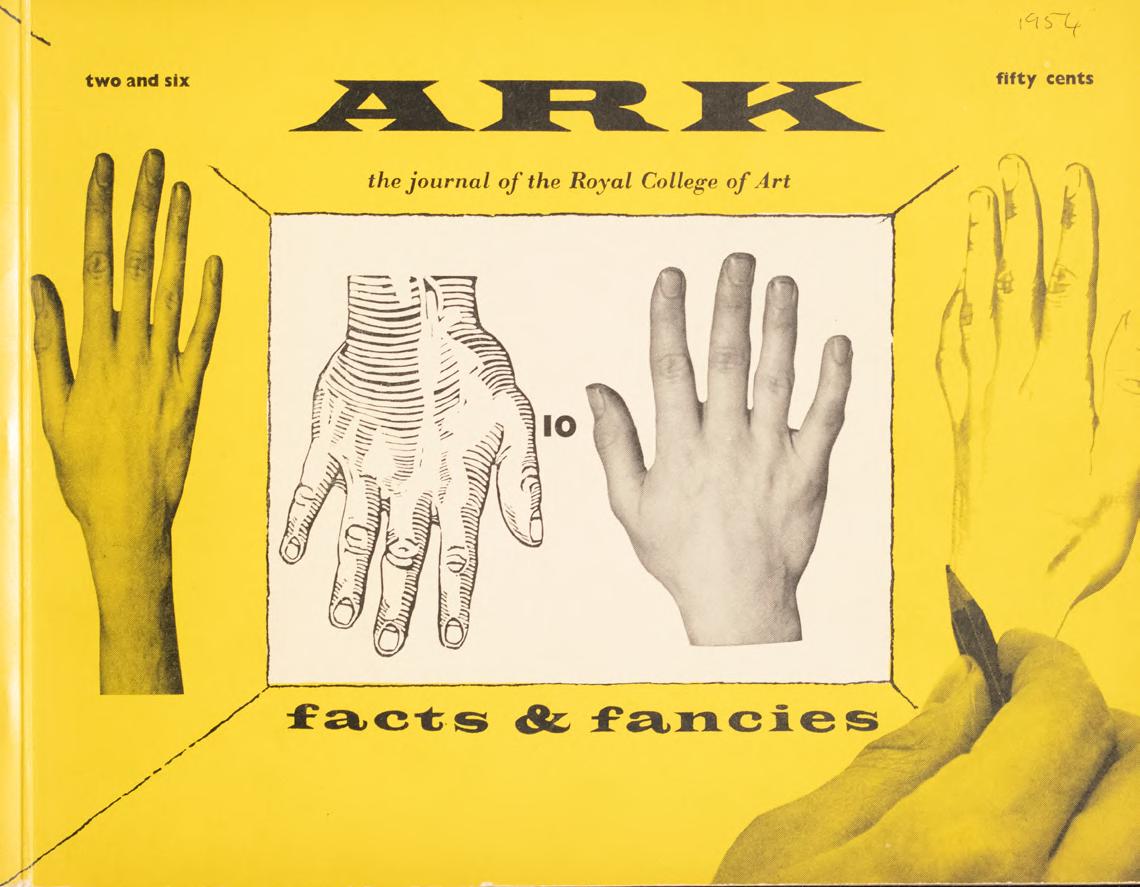

As far back as or as recently as 1950, the world saw the first issue of ARK magazine initiated by Jack Stafford, an RCA student in the School of Woods, Metals, and Plastics. The cover for ARK 1 was prepared by Geoffrey Ireland - an RCA student at that time and a famous British photographer and writer after. What did this magazine look like? For better understanding, it is important to tell some words about the rules this issue was built upon. In 1950, Richard Guyatt, RCA first Professor of Graphic Design, had his inaugural lecture entitled ‘Head, Heart and Hand.’ During his talk, he raised a question about what professional art is: Guyatt argued that each professional artist should be a painter who learns from his heart, a designer –from his head, and a craftsman from his hands. According to him, only a combination of these three components can bring significant results in the art. From the very first issue, ARK exemplified Richard Guyatt’s aim to integrate head, heart and hand. The magazine had all components at high level: illustrations, content, posters, design. And yes, the question of ‘high’ and ‘low’ is very unclear, isn’t it? While understanding the difference between ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ is vital, explaining it is almost impossible. Guyatt commented on this: ‘If the idea behind the poster or a press advertisement is cheap and silly, then the expression of it in pictorial form is bound to be cheap and silly. Obviously, one cannot teach design at the debased level. To learn about design, one must first of all understand what is ‘good’ in good design. This means developing one’s taste… Ability in a young designer grows by this assimilation of good taste coupled with the effort of recreating it in new and personal forms – in understanding and then trying to create good designs.’ Developing a tastethis is what we started with. This is what remains

questionable. And this is what ARK managed to achieve. From the very beginning of its exciting path.

Describing the purpose of ARK, Jack Stafford stated: ‘The elusive but necessary relationship between the arts and the social context are the real objects of our enquiry through the pages of ARK and our policy will be to set a subject, give our answers as students of the arts and ask a selection of those who will see the same subject from other and different viewpoints. We shall serve this mixture up to you with the firm belief that it is best to be serious without being solemn.’ In his book ‘Burning the box of beautiful things’, dedicated to ARK magazine, Alex Seago believes that one of the main reasons why ARK still remains a valuable archive for the cultural history, is that its ‘object of enquiry’ remained ‘the elusive but necessary relationships between the arts and the social context’ throughout its twenty-five-year story.

The significant feature of ARK was that it was never a typical student magazine. Although many contributors were students or members of staff, many of the magazine’s writers were ‘representatives of the cold, hard world... chosen for their open-mindedness towards contemporary trends in the arts.’

ARK tried to find a balance between publicising students’ work and ideas and keeping ARK in touch with contemporary developments in the world outside College. Len Deighton, art editor of ARK 10, described: ‘When I took over the art editorship at the end of 1953 I said, ‘What’s it all about? Is it a college magazine? Is it something to sell the College to manufacturers and employers?’

No one knew. It was typically English. No one could decide. In England the whole way of living is predicted upon never defining anything, because that way no one can get it right or wrong.’

Despite this vagueness of purpose - or because of it? - ARK reached success in a very short time.

7

By the end of 1950 ARK’s circulation was already over 2000, peaking at 3000 by 1963. Copies were sold both by subscriptions and main art bookshops in London. Moreover, ARK became popular far beyond the United Kingdom: by 1952 it had subscribers throughout Western Europe, The United States, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Although from issue 3 ARK started to receive financial support from the Royal College of Art, a huge part of financing came from sales via bookshops, subscriptions, and advertising revenue.

And the last one played the most important role. The main advertisers were about twenty firms, most of which had direct or indirect links with the College. As ARK was the most prestigious and widely read art school magazine in Britain, the money spent on buying advertising space in the magazine proved to be an excellent investment. Since, ARK’s relationship with the advertising agencies was quite beneficial.

ARK was part of an era of cultural transformation across fashion, film, television, advertising, newspapers and magazines. Such was the stature

of ARK that it drew contributions from creative luminaries including Ralph Rumney, Lucio Fontana, Alison and Peter Smithson, Toni del Renzio and Reyner Banham.

An editor ARK 24 and 25 Roddy Maude Roxby mentioned that he met a lot of people through ARK he did not know before – meaning a lot of artists and creative practitioners. Particularly, he mentioned Lucio Fontana saying ‘Lucio Fontana

I hadn’t heard of, and then he made us a piece of wood with a nail sticking out, and we punctured every page to the line that he’d drawn on the

outside. Then someone kept the piece of wood with the nail as a Fontana!’.

Literally, ARK united the best from the best - and being part of this magazine meant to become a part of the professional art world.

The covers of ARK deserve special attention, as they carry not only an aesthetics and a design idea, but also a deep symbolic meaning, sometimes revealing not only the trends of the art world, but also political and social challenges. In the context of nuclear proliferation, the Vietnam War, South

8

African Apartheid and enduring class divisions, student political consciousness was raised, finally climaxing with the student protests of the late 1960s. The figurative illustration increasingly seen on the covers of ARK during this period, harnessed the power of the pictorial image as a mechanism for communicating political and social preoccupations.

The covers of ARK are an invaluable historical document: A treasure trove of graphic and illustrative gems that map and often anticipate aesthetic shifts over the three decades of the

magazine’s existence. They point both toward institutional changes within the Royal College of Art and shifts in the wider culture outside it.

For ARK 24 of 1959, which reproduced a number of works by Italian artist Lucio Fontana inside, Postle designed a vivid orange cover, artfully punctured and slashed to echo the qualities of Fontana’s canvases and incorporating, rather impressively, a signed work by the artist himself. It would be unusual today to find a magazine that would adopt such an audacious approach to design, and in 1959 a deliberately punctured ‘Dadaist’ (or

indeed Arte Povera) cover was unheard of. ARK 25 of 1960 designed by Terry Green and Mike Kidd was to prove if anything even more controversial, combining a close-up of Brigitte Bardot’s face captured in three-quarters and bare shoulder in a high-contrast black and white reproduction: the title, price and issue number are written in a continuous line in a random –but in fact obviously highly designed – ‘jumble’ of capitalised and lowercase lettering.

A design critic Rick Poynor said: ‘...ARK has become a vivid historical document. It records,

narrates, evokes and recalls its moment (or succession of moments) with energy, eloquence and insight. There were other contemporary British magazines about visual subjects with elements of content or design in common – Motif, Typographica, the short-lived Uppercase, even The Architectural Review – but…none of them could match ARK’s twists and turns, its visual conceits, and coups de théâtre, or its eclecticism of content during its heyday from the late 1950s to the mid1960s.’ Why until the 1960s when Ark was still in existence until the middle of the 1970s?

9

The crisis came in 1959-1960. By this time, the essential aesthetic distinctions between ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ taste seemed to be under siege. The following years for ARK were characterised by ‘the new breed of student which was beginning to filter into the College from provincial art schools.’ Robin Darwin described: ‘The student of today is less easy to teach because the chips on his shoulders, which in some instances are virtually professional epaulettes, make him less ready to learn… this no doubt reflects the catching philosophy of the ‘beat’ generation.’ Perhaps, the decisive sign came with ARK 34, which consisted of an entirely visual collage of violent and semi-pornographic images, including a montage of Princess Margaret in a bikini surrounded by Britannias brandishing ‘Vote True Blue. Vote Conservative’ placards. This issue stretched the tolerance ARK was aiming at to the limit.

By mid-1964, according to the editor of ARK 35 Michael Myers, the magazine had been eclipsed and was unable to compete with the mainstream media: ‘The main criticism of ARK is that it has no recognisable sense of direction, that it meanders aimlessly across the graphic scene, falling prey to any passing visual trend which happens to come along, that it is like other magazines. It is when ARK is comparable to another magazine that it is bad, because it cannot help but come off second best to whichever magazine it happens to be compared with…’ Although ARK continued to be published until 1974, its moment had gone. According to a British critic and writer Reyner Banham, the 1962-3 issues of ARK gave the impression of being ‘flashy and footloose’, producing ‘quick and showy aesthetic returns on a minimum outlay of talent and intellect’. An art editor of ARK 32 Brian Haynes said that his main preoccupations at the time were ‘trying to have a bit fun… and not doing what had been done before… searching for a new style.’ It is significant that such comments are from the editor of the

magazine. Despite acknowledging the insufficient quality, they were unable to make changes as the problem was wider and went beyond the editorial office. It laid in the pop-graphic movement which brought significant changes in the perception of the art world, and, as Reyner Banham mentioned, led to the vacuousness of ARK’s pop graphics. According to him, that period was characterised by British indifference to theory and lack of research into ‘the techniques and skills of communication.’ ‘No one is doing any research’ - Banham added. The editor of ARKs 35 and 36 Michael Myers had a similar critical opinion: ‘It is in its overall use of graphics that ARK is often at its weakest. Looking through the past ARKs one is almost overwhelmed by the proliferation of slick sharp bizarre type of imagery which seems to have been lifted carteblanche from the ad man. The imagery are ‘now’ images whose only relevance is to today.’

On the one hand, these were trends in the art world that could not be influenced. On the other hand, was it an attempt to go mainstream?

An attempt to keep up with the times, which became a fatal mistake and put the history of the magazine on the finish line? It seems like it was a game without rules. The feeling that you can do everything. Erasure of concepts of quality, and lack of feeling the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’. It was a new wave in the art world which ‘penetrated very deeply into the subconscious and washes away all prerequisites for the development of ‘good taste,’ - the issue we questioned at the very beginning of this story.

Didn’t the 25-year history of ARK convey the centuries-old history of Art?

10

Photos:

Royal College of Art Library, Special Collections

References:

‘ARK: words and images from the Royal College of Art magazine 1950-1978,’ RCA, 2014

Alex Seago ‘Burning the Box of Beautiful Things: The Development of a Postmodern Sensibility,’ Clarendon Press, 1995

Roddy Maude Roxby. Interview. Conducted by Neil Parkinson, an RCA Archives & Collections Manager. Summer 2023

11

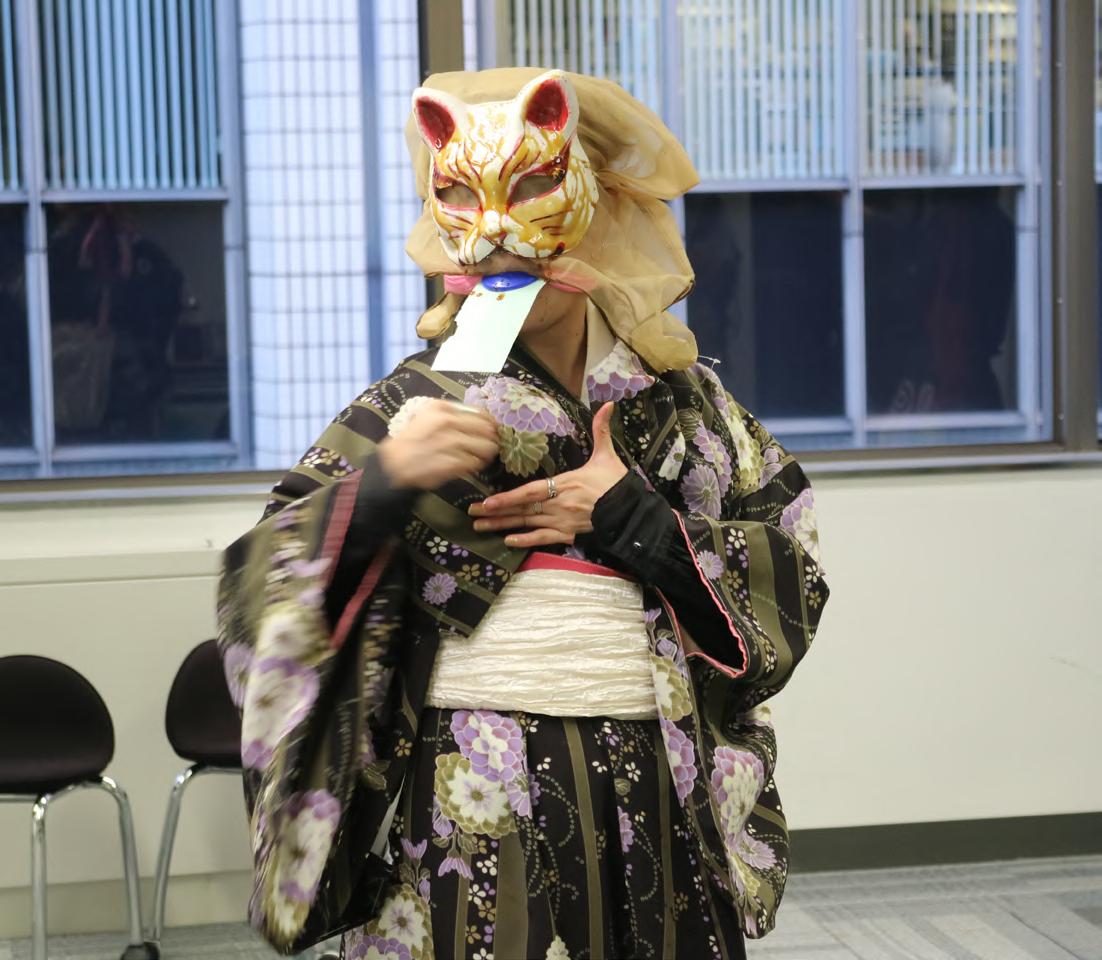

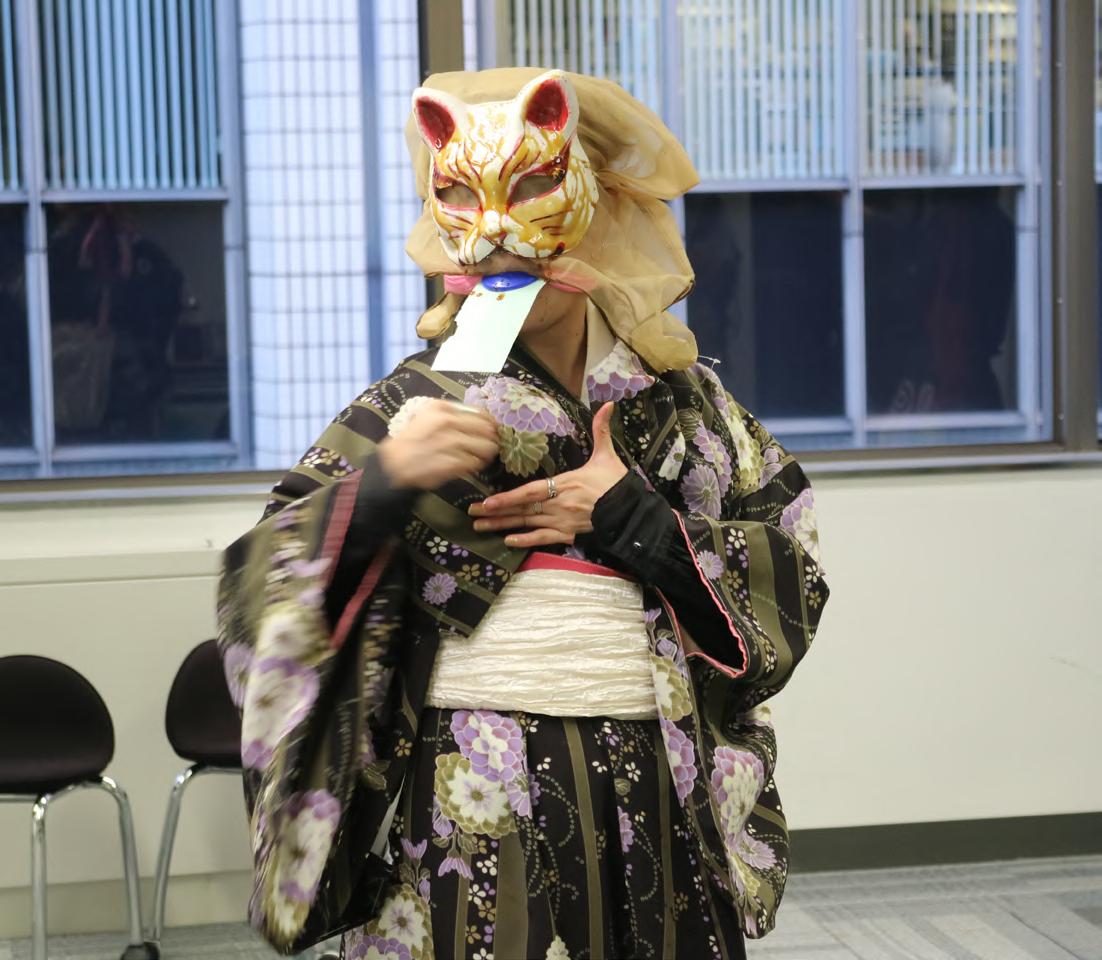

Shape

writer Yuna Goda interviews artist Noe Iwai

Noe Iwai is a performance artist whose works rebel against racism, categorization and prejudice; especially of which romanticize or fetishize Japanese female figures. They perform with a fox mask, sometimes pre-made or hand made by the artist themself. The sly, cunning, and mysterious fox, also known as a “shape-shifter” in Japanese mythology, inspires their practice. Also a graduate of the RCA Contemporary Art Practice and MRes Fine-Arts & Humanities, they performed in many places such as the South London Gallery, San Mei Gallery, and YAU Studio in Tokyo.

Yuna Goda (left) and Noe Iwai (right). Photography by Schwarzsonne

Shifter

To me, Noe is a close friend who lets me stay at their flat every now and then. I’ve stumbled into their room so many times, usually talking for hours. Their room is becoming my second home. It is not only because they are so welcoming, but we share a similar childhood travelling in and out of Japan. I find comfort in this space, where I don’t need to justify my identity that doesn’t quite belong to Japan anymore, nor does it feel closer to the UK yet.

Knowing about Noe’s journey between Japan and the UK, I had always known that the “in-between-ness” had largely shaped their identity. However, this interview became the first time I asked Noe to directly articulate how the fox mask represents it. The fox held a much deeper meaning, weaving cultural identity, gender, and historical context into their performance.

The Fox and Identity

Yuna Goda: Could you please tell me how the fox reflects or symbolizes your “in- between” identity?

Noe Iwai: The idea of the fox mask came pretty randomly at first, just like, “Oh, I need a mask, I need something to cover my face, to do whatever the fuck I want.” And I knew the fox as an animal that can shape-shift in Japanese mythology. In Japan, they’re quite well respected. They are the protectors of shrines or temples. Foxes are around, but not on the street. In England, I’ve seen foxes a lot on the street. Those two kind of connected.

And I had this—how to say—this kind of feeling being a Japanese female. I was not happy when people focused on my gender, or identity, or nationality. I wanted to erase that for a bit. I mean, if Japanese people see the mask, they will know I’m Japanese, because of the traditional white fox mask, but it’s more like a metaphor. I don’t know if I’m answering the question, right.

Y: Oh definitely. You’ve mentioned how the fox is familiar to both the British and Japanese culture—but it’s also interesting how, at first, it was the anonymity of this fox mask that actually enables you to perform and make an opinion. I’m curious, is the fox something you embody? Or does it come naturally to you?

13

illustration by Yuna Goda

N: A bit of both. Before, it was more like me becoming a fox, in a show. But at this very moment, I’m more like, taking the role of the fox. I’m the fox that shape-shifts.

Like, I recently started voguing. So, I’m acting my unusual self. But it is a comfort zone for me actually. Being a Japanese female is uncomfortable, because I get the judgment. But it is my comfort zone to be in that space to be seen.

Also I’ve discovered a while ago, and came out with the pronouns they/them. Before, my friends always called me Fox. Like, “hey, Foxy.” That became my identity, whatever way they wanted to interpret it. And I really liked that. So now, the fox is more about me. Not as work. I could be this, or maybe that. You know? Like, there’s this fluidity when I’m playing around with the idea of the fox in Japanese mythology and folklore.

Y: I actually really like how the fox shape-shifts. I personally think of identity as something very, very fluid. It keeps changing.

N: Yeah no, I fully agree. I think the “in-between-ness” is what we’re all about. I don’t even like the categorization as compromised in using they/ them, I really want to be a fox because like, fox is fluid. Okay, they do have a gender to begin with. But they shape-shift into anything. I’m aware of what body I was born with. But I’m allowed to change, fluidly, while being myself.

The Fox Mask and its Form

Yuna Goda: In the earlier versions of your performances, you use the white fox mask, which is very typical of Japanese culture. I mean, I guess that’s also because you’re actually referring to Japanese culture, like in the Still Live performance.

But in some of your recent iterations you’ve used more European-looking masks, like the rubber one in “Fox Journey”? And at the Crossbones graveyard, you handmade your own fox mask with chicken wire. I can see this exploration of the form of the fox...

“AM I A BAD CHILD or STUPID BRAT 2023”. Performed as part of the Still Live Studies Program at YAU studio, Tokyo, Japan. 23rd August, 2023. Photograph provided by artist.

“Fox Journey” 11th June 2022. Durational Performance from Archway station to the Highgate Cemetary. Photograph provided by artist.

“AM I A BAD CHILD or STUPID BRAT 2023”. Performed as part of the Still Live Studies Program at YAU studio, Tokyo, Japan. 23rd August, 2023. Photograph provided by artist.

“Fox Journey” 11th June 2022. Durational Performance from Archway station to the Highgate Cemetary. Photograph provided by artist.

14

Right: “Playing Alone with a Fox Inside a Cocoon” 27th May 2023. Performed at Crossbones Graveyard.

Photograph provided by artist.

Right: “Playing Alone with a Fox Inside a Cocoon” 27th May 2023. Performed at Crossbones Graveyard.

Photograph provided by artist.

Noe Iwai: Yeah, the form of the fox. The chicken wire on the recent fox mask— I spoke about the concept quite frankly with Michelle Williams Gamaker at the South London Gallery. And she said, “oh, just like a worm-in-a-bud kind of feel.” And wrapping the chicken wire around my face, the process, was a bit painful. You know, like, I really felt the cage type of feel like, “am I the chicken?” I immediately imagined a fox breaking the chicken wire, and snatching at the chicken. And eating it. But, to be really honest, the work I did in Crossbones graveyard and the concept of the mask didn’t really match. I’m still tidying. Yeah. I liked the mask, but not the performance that came with it.

Y: I thought the original concept of the fox was something that really frees you. Whereas the chicken wire almost traps you inside it.

N: So actually, I was trying not to press the wire against my face because it will cut me. It was physically risky. I can look cute with the fox mask, but if somebody touches, it may hurt me. This is more about me having the they/ them pronouns. Like, what if one day I would like to shape-shift into a man, for instance. I don’t think I would now, but a couple of years ago, I’ve considered. I searched about the medications, or the things that I will have to do to change my body. But my body doesn’t usually react well to medication. I will feel comfortable in my new skin or look, but it’s really that aftereffect.

Y: Oh, I understand it now. Basically the fox really allows you to shape-shift, but because it’s made of chicken wire, there’s a risk. Like it hurts you.

N: Exactly. And you might scratch someone by just walking around or by being touched. That was quite realistic to me.

The fox mask and belonging

Yuna Goda: Most of your inspirations come from Japanese traditions or contexts. Would you be interested in referring to folktales in the UK? Because you’ve been in the UK for a very long time too.

Noe Iwai: It’s gonna be half-half in May. Half of my life in Japan, half in England. I have been going back and forth between England and Japan since I was the age of four.

I admire Japanese tradition, history and mythology. Some of it is nostalgia. My grandmother would teach me these things. But I sometimes think the way I’m working on it, is almost like from the Western eye. Like, if I were in Japan the whole time, I don’t think I would have been inspired by the fox so much. I started working on the idea of fox, once I was in the UK. And because the British foxes and their fables were close to me too.

But I think I’m playing with my Japanese identity to begin with. And the shape-shifting foxes are only in Japan and China as far as I know. Yeah.

Y: That’s true. Yeah, that is the most important part of the fox.

N: Yes. For me, the fluidity and shapeshifting is really important. If I work on British foxes it will change the message. I think the focus will be more about the characters and mannerism, which I’m already embodying. So it’s kind of mixed.

16

Y: Tell me if this is wrong... but I was thinking about the reason why you could have resonated so much with the Japanese fox. It might be because the Japanese fox has this other-worldly feeling to it. It’s distant to you. But yet it somehow feels like home. So this strange balance of being otherworldly, and home, maybe fitted you. Because I actually find that similar to voguing—since you brought it up earlier in the conversation. It has an aesthetic that’s different to ‘normal’ fashion, but it invites you as a family.

N: Thank you so much for saying that. It was beautiful that you’ve mentioned it.

I think everything that I got inspired or got attracted to is ‘fight’— activism and revenge, or protection, in the form of art. I have a background in Karate, a type of martial arts, and I got into that because of this. And voguing.

Voguing was created in the 1960s to 1980s, post-war. There were racist movements towards Black and Latin LGBTQ+ communities, including transwomen and people who were homosexual. Then, in response, they started a Ball Room culture that developed into a form of art like vogueing. So it has a brutal background. But I connected with how vogueing is a safe space for self-identification, for self-expression.

That’s that, but the Japanese foxes’ mythologies, again, come from the background of like, “humans are stealing the nature and we don’t have food, so we will come and steal.” They were betrayed by men, so they come to revenge. And they do it by shape- shifting into a woman. Actually a sly, cunning, sexy woman.

In Ballroom scenes—where vogueing evolved from—there are houses. And the fathers and mothers of the houses might be vogue performers, models, MCs, and many other types of practitioners. The kids are trainees of the fathers and mothers. They really are a closed society, but they’re inviting. Karate have different but similar cultures... In Karate there is “Doujou” with different “Ryu-ha”, which is like houses with different styles. The geisha society has the “Ozashiki”, which is much more alike houses. They are also inspirations for my performance.

When you say this ‘home’ type of feeling, it’s really correct. Maybe I’m searching for something I feel grounded to... I feel I have to make my own family. And I already treat my friends like my family.

Y: I feel that!

N: I know. I think anything that comes with, a shape of ‘family’ can be very complex. Voguing is also a competition. But I think yeah, again, transforming into another self by vogueing— how vogueing is a rebellion to the prejudice and racism, connects so much to my rebellion to the maledominated society. And the foxes’ revenge. And how I, as a non- binary person so In-Between, fluidly shape-shift into different figures in that space... Crafting language. I think it’ll be really helpful for my future research.

Photography by Schwarzsonne

Photography by Schwarzsonne

In

Betweenness:

The Space Where Truth Lies

by Yenah Kim and Zofia Kierkus

' We are living in a time of global humanitarian emergencies.'

We are taking a moment to pause and gather our thoughts and reflections after the talk between Ai Weiwei and Dr Kareem Estefan, organised by The Social Canvas Projects and The Fitzwilliam Museum Society. The event ('The Role of Interdisciplinary Creativity in Social Activism: When Ai Weiwei's Art Meets Journalism and Artificial Intelligence") took place on the 17th of January, and it’s a part of The Social Canvas Projects’ Art Politics series, a sequence of interdisciplinary projects aimed at providing a platform for contemporary artists to explore the intersection of creative arts and politics through the materialization of political discourse and the presentation of creative works.

Ai Weiwei is discussing his beginnings of using the Internet as a medium, blogging online, censorship and propaganda in communist China. Ai is also sharing his reflections on freedom of speech, human rights and why being an artist is a privilege. 10 years later, he is meeting with the editor of the Creative Times Report.

Image from the event, Ai Weiwei on the left and Dr. Kareem Estefan on the right

Photo by Eliana Dyer-Fernandes

Image from the event, Ai Weiwei on the left and Dr. Kareem Estefan on the right

Photo by Eliana Dyer-Fernandes

Through the lens of “in-betweenness” we are looking at artist’s relationship with technology, Artificial Intelligence and their influence in truth-seeking. We discuss what ‘freedom of expression’ can mean today and what the role of art is in creating spaces for freedom and respect. We are also thinking about mediating spaces where different perspectives are valued and whether there is a place for collective “truth seeking” at all.

Over decades, Ai Weiwei’s practices have been conveying the artist’s continuous endeavour in search of the truth. His journey to locating the truth translates into his latest work Ai vs AI, broadcasted by CIRCA through Piccadilly Lights in London for 81 days. Ai vs AI marks the artist’s first collaboration with AI as a tool for his practice. Every evening at 20:24 in the flickering billboard lights at the centre of Piccadilly Circus, the artist addresses the question—Why am I here? Is true democracy possible? Are you controlled by the privileged class? In those ongoing questions, AI answers, and we reflect.

We are living in a time of global humanitarian emergencies. Information and content around social, political, and cultural issues are constantly shaping and polarising in the media. In a world where information is continuously pouring in, locating the truth seems challenging. Some things become clearer when you blur the lines. So the truth does. To blur those lines between right and wrong and to pave the way for searching for the truth, the artist starts to ask questions. During the talk, he says: “Everybody has the right to ask questions. ... This is not about freedom of speech. This is about freedom of questions. Everybody has the right to ask questions. Questions are important because they relate to our personal stories.”

Could we truly say we are living in a world where we have freedom of speech and the right to express different points of view? Felt frustrated under the circumstances that the artist has experienced both in China and the West, Ai found a way to express his freedom of speech and right to ask questions by utilising technology and AI. During the talk, he says: “If humans will ever be liberated, it will be because we ask the right questions, not provide the right answers. ... So if you don’t have freedom of speech, at least have freedom to ask questions. I ask the questions to AI and AI answers.” As he mentioned, asking the questions to AI, the artist himself, and ourselves might be the way of seeking truth.

However, he clarified the difference between humans and AI when it comes to the way of seeking the truth. For the artist, inviting AI into the practice is like working with any other tool that is under human control. AI is trained to analyse a large dataset and identify the keywords of texts and patterns of code. Therefore, “as technology accelerates the speed and accuracy of the existing information, the answer is fast.” On the other hand, the truth exists in diverse types and forms for us as a human: “There are many different types of truth, there are facts, truth in opinion and perspective, and social events, and also there is a very different truth related to aesthetics and moral judgement, and also in philosophy.” As Ai says, knowledge comes from the endless decisions to make, and the answer is as ever-changing as the truth is. In those questions, there is no right and wrong. Therefore, our answers and the truth exist in the space in between.

19

It is important for us to have open and free space to breathe so that truth can transform and traverse freely between the differences. And these open spaces come from embracing the in-betweenness in which truth exists. In these spaces the truths will start to form slowly by asking the questions, reflecting on them, and having the will and right to express.

Perhaps the question is: for what truths do we want to make space for? Or how do we position ourselves in between these different truths?

In November 2023, Lisson Gallery indefinitely postponed Ai Weiwei’s solo show, just after he shared his comment on the situation in Gaza. The gallery made a statement that the show was postponed as a mutual decision after extensive discussions with the artist. Asked about his perspective, Ai says “When in general the West thinks they have freedom of expression, I think it’s the biggest lie - you don’t have freedom of expression. If you say something and it brings you trouble, that means you don’t have freedom of expression. You have to respect different opinions - and it’s not about what is right or wrong, it’s about having a right to say what you really think.” Understanding Ai’s experience and history with censorship and repression from the Chinese government, it’s interesting to now hear his opinion about limitations on freedom, happening in the West.

Where can we find the momentum to share our truths while respecting other opinions? It’s not as simple as it sounds - we all want to have freedom of expression and for our opinion to be heard and respected - at the same time it’s not easy for all the entities to accept particular opinions as they might not be aligning with their ethos. Freedom also has to find its own space. And I believe a space where freedom can be secured is also a space full of respect and understanding. And that is the challenge of our times.

What can art do?

How can art become a space for mediation in the in-betweenness of perspectives? How can we secure freedom of speech, but at the same time secure that what is being expressed is not harmful for any side? I think in the end, it all comes to being a human and sharing our feelings and observations with others. There is something really concerning nowadays with the need of exposing our opinions. Don’t get me wrong, I do support freedom of public expression, but what social media and digital platforms are gradually doing to us, is instead of finding common ground and sense of togetherness in these heartbreaking times for humanity, imposing a declaration on one of the polars. And what it does is definitely not helping the fight for freedom and peace. Not everything is black or white, and I believe that’s the urgency of the arts now - to mediate in between these polars and to bring people together to seek universal truths that empower our feeling of humanity and unity, instead of dividing us into other conflicts and wars. These kinds of spaces are so important for the growth of our society and for enriching the transnational debate on universal values that are important to all of us.

20

This is the urgency of the arts now. To create a safe space for freedom of expression to take place. Instead of finding the diversity and opposed views as problematic, maybe we can start treating them as a potential for enriching our culture and reforming the societal structures. As Ai said in the beginning “There are many different types of truths (...)”, and maybe it’s time to embrace it.

Even though the truth has different types and forms from each perspective, it shares a common ground: a sense of common humanity. And truth grows in the freedom of expression and the act of questioning and asking. I believe freedom and the truth find their own space in the “ in-betweenness”. In this fluid space where the line between right and wrong is blurred, the different types of truth intersect with each other on the soft ground of humanity that consists of understanding and embracing differences. And they will continuously and freely traverse and cross away from each other.

As his work Ai vs AI shows, AI answers. However, we, as humans, have a will to ask and reflect. As we would never know where the river begins and where the waves of the ocean start from and end, truth is constantly forming and changing by asking and reflecting. So, let these spaces of in-betweenness freely flow by asking questions, thinking and searching for the truth. Here, in the space in between, the truth and freedoms shall sprout.

'For what truths do we want to make space for?'

21

Photo by Eliana Dyer-Fernandes

Image from the event

MARGARET (WEIYI)

MA Curating Contemporary Art, Royal College of Art

Through her art, Weiyi (Margaret) Liang raises the question of what self image and bodily autonomy mean in today’s conditions of life in-between cultures and nations. In addition to this, Liang explores the issues of intersectional feminism and gender expression. The ‘Mountain of A’ photo project focuses closely on masculinity, and aimed at presenting of how it looks in female subjects. Liang uses bodybuilding as an act of defiance against the confines, and cultural and racial expectations of hyper-femininity.

ART GALLERY

ARTWORKS EXPLORING 'IN-BETWEEN-NESS'

LIANG

22

23 ART GALLERY

The ‘Mountain of A’ photo project

SCHWARZSONNE 黯耀

MA Print, Royal College of Art

My life is lingering and torn between illusions and truth, dreams and reality, brightness and darkness, greatness and humbleness, beauty and ugliness. In the name of art and poetry, I try to distort and transform all the encounterings granted onto the Wheel of Fortune: be it happy or sad, virtue or fault; I endeavour to extract and purify the quintessence of my experiences by the alchemy of images, mixing with hopes, prophecies, rhapsodies, lies and Wahrheit even discovering and finding the inner light and holy cores in the darkest, the lowest and the most spleen objects, breathing means of existence into them, then fighting against hunger, poverty, coldness, death and all the enemies of wonders in our life.

ART GALLERY

24

小妹妹,妳就好好享受這盛夏最後一夜的跳繩吧。

ART GALLERY 25

Little lass, just come and enjoy the rope skipping in the last evening of the hot summer.

Reise der Magiestadt (023) by Schwarzsonne

水晶燈,你在默默而冷冷地審視著哪一個無光盛宴?

Crystal chandelier, coldly and silently, which lightless banquet have you been looking at?

Reise der Magiestadt (028) by Schwarzsonne

GALLERY

ART

嘿,古馳,穿透光陰幽暗之隧道,你是否曾經預見了飢餓帶來的崩塌時日?

Hey, Gucci, through the obscure tunnel of Time, have you ever foreseen the fallen days of Hunger?

27 Reise der Magiestadt

ART GALLERY

(033) by Schwarzsonne

NICOLE MOORE

MA Writing, Royal College of Art

The circles theme of my painting depicts my cultural heritage and identity as a fluid and evolving entity. The top circle represents the colours of the Guyanese flag. The bottom circle represents the colours of the Union Jack flag. The middle circle represents my identity positioned between both circles balancing out the Guyanese and English cultural heritages as supporting rather than dominating my identity. The diagonal position of the circles signifies movement.

The background colours red, yellow, and green are the colours of the Rastafari flag — the very same colours of the Marcus Garvey movement back in the early 1900’s — and represent the bloodshed of the African people, the natural wealth/gold of the African land and the lush fertile greenery of the African continent. This colour scheme reflects my appreciation of the Rastafari philosophy (not the religion as I’m not religious), and respect for the culture, vegetarian diet, and reggae music.

The painting can be displayed in a portrait or landscape position as long as the background colours follow in the sequence of red, yellow, and green.

Description from Nicole’s art blog: https://nicolemooreart2022.blogspot.com/2022/04/englishguyanese-cultural-heritage.html

ART GALLERY

ART GALLERY 29

British/Guyanese Cultural Heritage (2019) by Nicole Moore

ELF (WANRONG) ZHU

MA Photography, Royal College of Art

“This series of works is a deconstruction and reconstruction of self under the background of the post-truth era based on my discussion of personal identity. I scanned my body in 3D software, flattened my body in 3D virtual world to a 2D world, and then turned these 2D physical images into experimental video installation, which is a process of changing 3D into 2D and then returning to 3D. In this process, my body shuttled through many interesting states and spaces, thus discussing that personal identity and physical body became more blurred.”

30 ART GALLERY

30

ART GALLERY 31

X,Y,Z by Elf (Wanrong) Zhu

ART GALLERY 33

X,Y,Z by Elf (Wanrong) Zhu

SOFIIA VINNICHENKO

MA Photography, Royal College of Art

It’s easier to talk about the past than the present, to understand where I was and who I was than am. This work explores the illusory nature of choice, shaped by our own previous decisions. It serves as an illustration to my essay from 2019, where I attempt to answer the question, “Who am I?”

Here is a part of it: “I am a fiction. Life is a single moment that stretches out to eternity during a fall. I am a collection of other people’s dreams. I am the spark of a star that has already died. I consume myself and give birth to myself almost simultaneously and continuously...”

Using the circle as a symbol of unity, infinity and balance, I introduce chaos to a scene that is already falling apart.

ART GALLERY

34

ART GALLERY 35

Free Fall by Sofiia Vinnichenko

[Digital C-Type Print (127x98 cm)] exhibited at the Royal College of Art

Claudette Johnson: PRESENCE Review

Claiming a rightful place in the history of contemporary art

written by Nicole Moore

Presence, featuring visual artist Claudette Johnson, a founder member of the Black British Arts Movement, known for her large-scale drawings of black women, showed at The Courtauld Gallery’s famous and newly refurbished Great Room from 29 September 2023 to 14 January 2024. The Presence exhibition expressed Johnson’s insight of a figurative artist as well as drew from the freedom that abstraction brings.

During the early years of her practice, in her search for works in the Western art canon that featured black women, Johnson could only find parodies of black womanhood depicted in paintings in ways that not only reinforced white cultural imperialism but also romanticized otherness. She responded to the need for something new, something more authentic and less invisible, offering a counternarrative, and this formed the foundation of her practice.

When traditionally women have been portrayed through the male gaze, Johnson reclaims and captures the powerful gaze and presence of black female subjects, by placing the black female figure front and centre in a way that traditional modernism renders the black female image as secondary, otherised like a backing singer without a voice.

Presence is all about the idea of black women taking up space and asserting their right to be here, in the art world, the Western art canon. The idea of this exhibition is also about the figure breaking through the constraints — large scale art with larger-than-life figures filling the canvas, means the visual narrative and landscape is one of black women’s presence not just within the exhibition but inside the frame. Why did The Courtauld Gallery choose to exhibit Johnson and why now? Could it be that it is now more appropriate that the newly refurbished third-floor display spaces, with its wooden flooring and neutral grey walls, are given over to showcasing the works of living artists, a kind of merging of the historical and contemporary, — “a chance to enjoy stunning examples of new and recently created works of art alongside the canonical pieces that grace our permanent collection.” 1 Johnson’s arrival at The Courtauld Gallery, means her work now rubs shoulders with Van Gogh, Gauguin, Manet, Picasso, and Renoir, artists that Johnson’s art historical education consisted of as a fine art student in the University of Wolverhampton, artists that she has been in dialogue with since she came to prominence in the 1980s during the first National Black Art (BLK Art Group) Convention 2 .

* * *

36

This idea of centralising black subjects in contemporary art is nothing new. Artists such as Barbara Walker, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Lina Iris Viktor, and Sonia Boyce, who represented Britain at the Venice Biennale (2022), and Lubaina Himid, a strong advocate of Johnson, and the first black woman and the oldest person to have won the Turner Prize (2017) to name but a few, produce artwork that depict black female figures. That this kind of work is being recognised now is questionable. Himid is concerned that ‘people might say: “Oh we’re showing them now because now they’ve got really good.”

Himid disputes this but is of the impression that ‘this current prominence is a fashionable moment, rather than solid progress.’ On the other hand, Himid is reassured that ‘a lot of those artists that were in their 20s in the 1980s are seen by younger [Black and Asian] artists to be making it.’ 3

Presence then, provides a unique opportunity to experience Johnson’s strong and commanding body of work. The Courtauld Gallery’s Marit Rausing Director, Professor Mark Hallett, is clear as to the importance of Johnson’s contribution, stating in the exhibition catalogue that: “Over a career that has spanned more than forty years, that has seen her having to confront and overcome a multiplicity of challenges as a Black British woman, and who

continues to generate extraordinary new work, Claudette Johnson has offered one of the most sustained and subtle explorations of subjecthood, and more specifically Black subjecthood, in the art of our time.”

Blues Dance (2023) is one of my favourite pieces in the exhibition and one of many captivating works. This is not a portrait; Johnson is resisting and moving beyond the traditional historical position of the portrait in her practice. This painting is a depiction of a black female figure totally absorbed in a dance movement. She looks serious, like someone absorbing music would. No eye contact could mean that she is at one with the music, not interested in us. The woman’s face is shaded light and mid-brown. Her hands are invisible, yet we can imagine them possibly finger-clicking to the music. Her vibrant blue dress with its light and dark tones dominates the painting. There is a stillness and movement between the dress and her other clothes layered under and on top and a connection between the blue dress and the blues dance. Her grey transparent jacket offers a light and additional layer. The contrast of a yellow polo neck top provides a warmth against the cool blue tones. Her hair is worn in an afro, a symbol of pride and heritage, an expression of a political statement indicative of the Black Power Movement.

Notes:

1 Price, D & Wright, B (Eds) (2023) Claudette Johnson Patience - First published to accompany the exhibition.

2 Looking Back: First National Black Art Convention (2020) held at Wolverhampton University - School of Art.

3 Guardian (2021) ‘Lubaina Himid: The beginning of my life was a terrible tragedy’ by Charlotte Higgins.

In the background, a thin red diagonal line is set at an angle across what could be a white heart shape. A shadow of a darker grey to the figure’s right contrasts with the grey jacket. The background’s brush strokes are solid compared to the rest of the painting. The far-right dark beige vertical panel provides the idea of a wall, there to support the dancing. We do not know whether anyone is in front, possibly dancing in the same way, with the same rhythm and movement.

Blues Dance — a new work made from a reference photograph that evokes the blues parties of the 1970s and 1980s — while being present now, is a profound painting and struck a chord, especially since I am of the generation that included Blues Dance parties in my social life. Blues Dance parties emerged as a social and cultural need for black communities in Britain at that time; they were favourite places to be and to be seen. These were unlicensed all-night reggae parties held in a house or other impromptu space, where someone would transform their home into a club for a weekend, catering almost exclusively to black audiences.

Blues Dance triggered memories of those partying days where the atmosphere was friendly, sultry, and dark. Sometimes, all you could see was the occasional flickering lighter flame igniting a cigarette, offering a smoky silhouette of the crowd. In the summer, it would get so hot that water droplets would form on the ceiling. I vividly remember intermingling smoothly into the darkness where I would lose myself as a result of being soothed by the heavy bass reggae rhythms, played by London’s sound systems 4 — Chicken Hi-Fi, Success Sound, and Soferno B — who all had large followings and would entertain us using big home-made speaker boxes, whose ‘Rewind Selecta’ DJ style would ensure our favourites were well-played, heard and promoted. At these much-needed events, we soaked up the music of Bob Marley, Burning Spear, Culture, Black Uhuru, and Third World; you would hardly hear this music in any other public places. These social and cultural events were also somewhat spiritual, almost church-like judging by the communities that developed over a period of years. The dancing, moving to a reggae beat and rhythm, transported you to an escape from the nine-to-five slog; work soon became a long-distance entity of the past, if only for a Saturday night which would extend into daylight hours on Sunday. We would leave a Blues Dance feeling energised and nourished not just by the Caribbean food that we had ate, but by the whole unforgettable experience of having access to melodies

that remained with us in our memory bank sometimes for as long as a week; the sounds were so imbibed into our consciousness, that even now they can be readily retrieved at a moment’s notice through social media outlets like Spotify or YouTube. Blues Dance reggae music has become legendary, featured in films like The Story of Lover’s Rock 5 and Burning an Illusion 6 both directed by Menelik Shabazz, Babylon 7 directed by Franco Rosso, and Lovers Rock 8 directed by Steve McQueen.

Johnson successfully demonstrates in Blues Dance in particular, how the image can make someone feel, what memories are triggered, what messages they communicate and ultimately how the work causes the viewer to engage in the transformative power of art. There are questions to be had about the way Johnson depicts music and sound as felt through the body. Blues Dance also raises the question of how we move in and around the gallery space, and how we engage with the artwork, how we may make a connection with the art rather than remain passive.

American poet and essayist Claudia Rankine, in an interview 9 about her book Citizen: An American Lyric, 10 in response to the question of ‘what might have been lost had images not been present in Citizen’, said, “One of my goals was to explore visual culture ... when one looks at an image, one can go anywhere.” American author and black feminist theorist bell hooks, in Art on My Mind 11 draws on the power of art to convert and transform, to expand our consciousness and our ability to create and nurture our spirits. Black feminist theorist of visual culture and contemporary art Tina Campt, in A Black Gaze, 12 also draws on those ideas; she asks us how we might not just look but listen to images, suggesting that we consider a series of questions: “What is the sound that precedes the image? What can you see, touch, feel, hear?” Campt also identifies sound as an “inherently embodied process that registers at multiple levels of the human sensorium,” arguing that it is possible through sounds to engage with forgotten histories that images transmit. This is particularly notable with Blues Dance, which evokes memories of the 1980s black music scene and through that artwork we are almost transported back to that time.

The way Johnson engages with the body, sound, and movement, bringing them together, merging them in the art, takes it beyond a purely aesthetic experience. The outcome for the viewer

* *

*

is an engagement that is enjoyable, liberating, and uplifting. Zadie Smith, in a YouTube interview, 13 where she discussed writing about art, said: “...one of the extraordinary things about visual arts is that its impact is instantaneous, I mean, I can take in the entirety of the art object in a moment. My considerations, my thoughts about it can extend over weeks and months but the act of viewing doesn’t occupy time in the same way as reading ... I was so struck by it, that I could have this experience of the sublime, without it taking up a three-dimensional time-space in my life.” This idea of time, for example, where our timing of what happens in our lives stays with us, supports the idea that the past is never where you think you left it; events may have happened years ago, but in our memory, the event is close by and easily recalled. Memory, nostalgia, and reminiscence are always there in the remembering visualisation process.

As viewers, we are encouraged to participate in the process of a slower looking at Johnson’s works, in order to interpret the full meaning of them, allowing ourselves, our bodies, to be moved and transformed by what we see. Johnson’s works exceed their physical form. They cannot be contained, the same way that through dance, the body cannot be contained. This kind of art represents a rich legacy of creativity and resilience that can be passed down to future generations.

Presence has the power to illuminate stories, traditions, and values that contribute a uniqueness and vibrancy to Black British culture. Apart from the positive visual representations of black women, Presence further contributes towards the multitude of different narratives, and different ways to depict blackness. This allows for seeing the black female subject in all of its complexities and multi-dimensional personas. Johnson’s repertoire enables us as viewers to explore and address some of the most important and engaging topics in the history of British art. The Presence exhibition — the contribution of the artwork, the curatorial decisions 14 , placements, and catalogue — effectively combine to communicate the essence and energy of black women taking up space and by doing so is changing the face of contemporary art. This is Johnson’s story, and her artwork is a testimony to her sharing her journey, which she successfully weaves into the wider Western art canon, on her own terms and with no apologies.

(Written by Nicole Moore)

Notes (continued):

4 Nice Up The Dance! — Celebrating the Influence of UK Sound Systems, FARAH, YouTube, 6 yrs ago.

5 The Story of Lover’s Rock, (2011) documentary film Directed by Menelik Shabazz.

6 Burning an Illusion (1981), the story of a black woman’s awakening, Directed by Menelik Shabazz.

7 Babylon (1981) Directed by Franco Rosso — Trailer by Film & Clips, YouTube, 10 yrs ago.

8 Lovers Rock (2020) Small Axe Series 1, Directed by Steve McQueen - fictional story of young love at a blues party in 1980, BBC One.

9 Claudia Rankine and Kevin Young on Influence in Art and Poetry, Key West Literary Seminar (2016).

10 Rankine, C. (2014) Citizen: An American Lyric.

11 hooks, b (1995) Art on My Mind - Visual Politics

12 Campt, T. (2021) A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See

13 Digital Alumni Week — In Conversation with awardwinning novelist and King’s alumni, Zadie Smith, King’s College, Cambridge, YouTube, 3 yrs ago.

14 Curators: Professor Dorothy Price & Dr Barnaby Wright. Exhibition Supporters: The Garcia Family Foundation. With additional support from Lubaina Himid, Jerwood Foundation, Tavolozza Foundation, and Hollybush Gardens gallery for their support with the organisation of the exhibition.

39

Photograph by Nicole Moore, 29 October 2023.

ART

CUTE

@TheSomersetHouse

Somerset House presents a playful exhibition CUTE, which delves into the widespread embrace of cute culture and its significant impact on contemporary society. Innocent yet powerful, cuteness has long evoked complex emotions, resonating with both children and adults alike. Embodying two seemingly opposite traits of charm and harmless, cuteness has deeply permeated numerous cultural facets, ranging from emojis to internet memes, video games to plush toys. The exhibition offers a compelling exploration of this phenomenon, inviting the audience to contemplate its multifaceted influence. Exhibition runs through 14 April 2024. until 14th April

Anna Perach: Holes

Anna Perach’s first institutional solo exhibition in the UK, Anna Perach: Holes invites the audience to delve into the liminal spaces surrounding female archetypes and reimagined concepts of flesh and skin. Drawing from cultural myths, Anna creates sculptural hybrids that explore ideas of gender, identity, and craft. This site of rebirth enables a space where the conventional understanding of flesh and skin is challenged and redefined. Exhibition runs through 28 April 2024. until 28th April @Gasworks

Anna Perach, Holes, 2024. Exhibition view. Commissioned and produced by Gasworks. Photo: Andy Keate

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM EDITRORIAL TEAM

William Blake’s Universe

The Fitzwilliam Museum presents the largest display of William Blake from the museum’s own collection. A visionary born “with a different face” (Poem in Letter to Butts, Aug. 16, 1803: K2, 251; cf. “Mary”: Kr, 228.), William Blake found himself straddling realms, existing in a space neither fully aligned with his own era nor entirely disconnected from it. Far from ordinary, he inhabited a solitary and isolated realm, fading into obscurity for generations until undergoing a recent reevaluation. William Blake’s Universe invites the audience towards spiritual exploration amidst the backdrop of war, revolution, and political turmoil. Exhibition runs through 19 May 2024. until 19th May @The Fitzwilliam Museum

The Time is Always Now: Artist Reframe the Black Figure

The National Portrait Gallery presents a group exhibition The Time is Always Now: Artist Reframe the Black Figure showcasing the works of contemporary artists from the African diaspora. It delves into the depiction, and absence, of the Black figure in Western art history. Through this exploration, the exhibition illuminates the richness and complexity of Black life. Exhibition runs through 19 May 2024. until 19th May

Amy Sherald, She was learning to love moments, to love moments for themselves , 2017. © Amy Sherald. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joseph Hyde

NEWS

@National

PortraitGallery

41

Unwittingly an Outsider, Enchantedly an Insider

by Soyeon Jung

Building an early identity within a society predicated on the idea of homogeneity comes with multifaceted individual predicaments. One way in which it manifested for me was the struggle to embrace my in-between status. It took one person to engrave a sense of shame in not fully fitting in, so deeply that it followed me for the better half of my life, and another to completely shatter it. This is my personal journey of reconciling with my ‘outsider’ status, unveiled through an encounter with a friend that unfolded over a few months.

I was born in Changwon, South Korea, and later relocated to Seoul. While moving back and forth between Massachusetts, US and Seoul, South Korea, I found myself caught between cultural and social identities, speaking neither the authentic dialect of my hometown nor fully adopting American norms. My educational background and upbringing were somewhat unconventional within the context of Changwon, my hometown, and my accent in Seoul would prompt curiosity about my origins, not to mention its perpetuation in US schools.

One particular event, intensely etched into my memory, marks the moment I became hyper-aware of my peripherality in the world. It was my first summer in Seoul at the age of 15 when I was set to attend a summer school. Not knowing what to expect, I woke up early, naively excited as any typical teenager on the first day of school. However, my anticipation soon took an unexpected turn when I simply asked about the room I was assigned. It was a straightforward question to which I expected nothing but a straightforward answer. Instead, the registrar responded with a quiet yet dismissive smirk, mimicking my tone as he casually asked where I was from. I still remember vividly, feeling completely exposed at such an unexpected response, with a burning sensation on my face as if I had committed a fault I didn’t even realize existed. I recall being unable to pull myself to speak for the rest of the day.

42

Fast forward to 2023, by this point, I had grown to speak as I pleased, albeit with the lingering awareness of the social cues that marked my ‘outsider’ status. Then I came to London, where I had no friends or relatives, and the culture and history were not of my familiarity. I came, to force myself out of my comfort zone, but I was surprised to find myself more in place than ever. It didn’t take me long until I realized the source of the comforting sense traces back to my lasting struggle with in-betweenness. Everyone was living in-between cultures and nations. Ironically, I felt a complete sense of belonging from ultimate displacement.

Particularly, one encounter with a fellow student (‘P’ thereafter as he wished to remain anonymous for this writing) in the MA Curating course marked another milestone I know will remain as impactful as my encounter with the registrar at summer school. P was born into multiple cultural identities with his maternal side half Japanese and Vietnamese, and his father being of Chinese, while his own nationality is of something else. I later learned that he wasn’t the best typical representation of his own nationality, as he told me about an incident where a cab driver assumed he spoke their native language well, when in fact, it’s his first and very own language. This is a point that made him question the essence of nationality.

What binds these two completely distinct individuals together?

P was not in any way ethnically identical with the driver, didn’t look like one of them, and he had a more varied identity when it came to cultural background.

His immediate response when asked about his feelings regarding in-betweenness was so unapologetically positive. He immediately connected to multiculturalism, highlighting the advantages of embracing multiple cultures. He raised his adeptness at navigating diverse societies, breaking down cultural barriers,

43

and understanding the unspoken nuances of various norms. His perspective on in-betweenness prompted me to contemplate conventional notions of identity. Yet, it didn’t fully capture the psychological predicaments that follow physical relocation, where one brings along a multifaceted identity. However, his response upon arriving in London, displaced from his origin, revealed something noteworthy at the intersectionality of multiculturalism, transnationalism, and the experience of inbetweenness. He said, “growing up with multiple cultural backgrounds enabled me to hold conversations about books and movies with random strangers without feeling ‘left out.’”

“Without feeling left out.” His words struck me. For so long, the feeling of not quite fitting in shadowed me with the unconscious need to fit into the communities I was newly entering and to adapt the identities they embodied. I had been so shackled by the experience of unsolicited shame that I have long failed to see the worlds I belong to.

Being in-between grants us the freedom to choose where we belong.

It was the kind of realization that had been within reach all along but required the right perspective and mindset to fully grasp. And in words it lays out as easily as followed: perpetual outsider, to a perpetual insider. I transitioned from feeling like a perpetual outsider to embracing a sense of belonging as a perpetual insider.

“always an insider”

Being is a mindset. It’s a conscious reframing of our understanding on belonging and identity. It’s about embracing our unique cultural heritage, experiences, and perspectives as sources of strength and authenticity. By adopting this perspective, we empower ourselves to navigate the complexities of identity that rewrite the narratives that shape our sense of belonging in the world and find liberation in embracing the richness of our individual narratives and celebrating the diversity of human experience. It’s a reminder that our worthiness transcends borders, cultures, and identities, anchoring us in a deep sense of belonging to ourselves and to the interconnected humanity.

I had two aspirations from this piece of writing. One was to convey what P helped me see – embracing the best of both worlds, questioning conventional notions of nationality and

44

identity, and embodying multiple cultures. I hope to alleviate the mark left on you, similar to the impact the registrar’s remark left on me. I acknowledge the power dynamics at play within the multitude of cultures and personalities embedded in multi and transnational identities. I also recognize external forces beyond our control that may influence how we perceive ourselves. Nevertheless, I wanted to emphasize the strength found in embracing one’s duality.

Another was to extend this thread of thought to the notion of transnationalism, a concept now prominent in many disciplines. Particularly within curatorial discourse, especially in the UK, transnationalism emerges as the ultimate method of meaning-creation (or however one defines “curatorial”). However, the essence of this idea is often misunderstood, risking curatorial practice as passive responses to the inevitable force of globalization. Despite dedicating an entire term exploring methods of achieving transnationalism in our curating course, the question lingered, What exactly is “transnational”? I felt that the reason why we failed to fully grasp its notion is not only due to lack of thorough debate and introspection on the precise definition of transnationalism, but primarily due to the fact we couldn’t see its relevance.

In a way, I aimed to create a space where the narrative of being in-between becomes a personal story for everyone. To present the feeling of in-betweenness, which is ubiquitous to all-in-one way or another, as a connecting thread that can resonate with everyone. My goal was to foster resonance because, only when this connection is established, rather than transnationalism as a concept applicable to specific groups, can we purposefully incorporate the idea of transnationalism within this ever more interconnected world, as well as in our artistic practices.

45

Editorial Team

Co-editors and contributing writers

Soyeon Jung ︱MA Curating Contemporary Art

Victoria Stepanets︱MA Curating Contemporary Art

Yuna Goda︱MA Writing

Yenah Kim︱ MA Curating Contemporary Art

Zofia Kierkus︱MA Curating Contemporary Art

Nicole Moore︱MA Writing

Design

Yuna Goda

Zofia Kierkus

Yenah Kim Photographer

Schwarzsonne︱MA Print

For inquiries or collaboration opportunities, please contact on Instagram @arttalksrca.

“AM I A BAD CHILD or STUPID BRAT 2023”. Performed as part of the Still Live Studies Program at YAU studio, Tokyo, Japan. 23rd August, 2023. Photograph provided by artist.

“Fox Journey” 11th June 2022. Durational Performance from Archway station to the Highgate Cemetary. Photograph provided by artist.

“AM I A BAD CHILD or STUPID BRAT 2023”. Performed as part of the Still Live Studies Program at YAU studio, Tokyo, Japan. 23rd August, 2023. Photograph provided by artist.

“Fox Journey” 11th June 2022. Durational Performance from Archway station to the Highgate Cemetary. Photograph provided by artist.

Right: “Playing Alone with a Fox Inside a Cocoon” 27th May 2023. Performed at Crossbones Graveyard.

Photograph provided by artist.

Right: “Playing Alone with a Fox Inside a Cocoon” 27th May 2023. Performed at Crossbones Graveyard.

Photograph provided by artist.

Photography by Schwarzsonne

Photography by Schwarzsonne

Image from the event, Ai Weiwei on the left and Dr. Kareem Estefan on the right

Photo by Eliana Dyer-Fernandes

Image from the event, Ai Weiwei on the left and Dr. Kareem Estefan on the right

Photo by Eliana Dyer-Fernandes