THE ARGONAUT

Radical Thought at the LSE

By engaging with comment, culture and fieldwork, The Argonaut is committed to challenging hegemonic narratives and broadening radical discourse

Welcome to The Argonaut's Lent term 'mini' print edition This past half-term has been quite extraordinary for us with the UCU strikes bringing a pause to regular learning, whilst demonstrating how our very own university has become a site in which contemporary neoliberal crises intersect. More now than ever before The Argonaut is here to be the LSE's space for critical engagement; to carve out a space for radical thinking in a time of encroachment. This issue showcases some of what we've been working on in the past weeks. We hope you enjoy; and if you do, please don't hesitate to contact us and contribute - we welcome pieces in the categories of Comment, Culture and Fieldwork, in written, visual and other form Funded by LSE's Social Anthropology department but led by students for students, we welcome submissions from everyone. This is a space for the anthropologically-minded community of LSE to express themselves and create a much needed community.

Much love, Iacopo, Ishani, Hila and Lucy

Immerse yourself into a sonic landscape whilst you're reading Taken from 'The Little Argonaut', Issue 005

SOMESONGSFORTHEROAD|OURMONTHLYPLAYLIST

Listen in to our global fusion and protest songs, specially curated for you by our very own Lucy Bernard each month

Our February Selection:

'The Warli Revolt' by Swadeshi, Prakash Bhoir

'Ola!' by Carwin Elis and Rio 18

'Parav' Ajere' by Nu Genea

'Jaan Pehchan Ho' by Mohammed Rafi

'Mudzimu Ndiringe' by Hallelujah Chicken Run Band

‘Munde Kehre Pind Ta’ by DJ Chino, Satwinder Bitti

‘Ronger Duniya’ by Lokkhi Terra, Shikhor Bangladesh All Stars

‘Tami’ by Onipa

‘Kulu’ by N'Gou Bagayoko

‘Gypsytronic' by Balkanotronica

'Samba' by Les Amazones de Guinee

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter at: https://theargonaut com/the-little-argonaut

www.the-argonaut.com

Anthro.Theargonaut@lse.ac.uk

Instagram: theargonautlse

Twitter: @LSEArgonaut

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

March 2023

1

Do we genuinely recognise them? - An Intimate MiniEthnography of People with Dementia in London

By Wange Li

In the summer of 2022, I participated in a volunteering programme at the Museum of London Docklands The programme is called 'Memories of London' and aims to help elderly Londoners with dementia recapture their youth through a series of activities in the museum I reflected for the first time on discourses of ‘memory’, ‘recognition’, and ‘personhood’, gradually becoming aware that the correlation between these was in fact artificial and cannot be taken for granted It was also through close encounters with elderly people with dementia that I saw their vivid but little-known vitality and their deep bonds with London and their loved ones

such questions, which could be offensive to people with dementia That was the first time I began to reflect on the question "Do you recognise me?", which many people, including me at the time, took for granted when referring to dementia: not only was it disrespectful to the individual, but it was problematic in a broader sense, as that the question itself was implied imbued with social and ethical judgements , which should not simply be relegated into to a matter of personal manners or an impulse of expressing sympathetic concerns

One day some months ago, I walked into one of the activity rooms at the Museum of London Docklands. The room was a bit noisy, with a crowd of people standing, sitting, or even lying on the floor. I could not tell what they were doing for a while, making me wonder if I had come to the right place.

"Ah! There you are at last. Come on in, we'll be starting soon." Seiwa, the manager, greeted me enthusiastically and seemed compelled to show me the exciting things that were about to happen.

As I took my seat, I saw David sitting beside his son (the carer) and looking quite nervous David had been talking to me so eloquently the last time we met, but this time in the middle of a group of his peers, he was somewhat tempted to join in the conversation of others but was seemingly too torn shy to step forward Meanwhile; his son was climbing into conversation with the carer of another elderly, making David look even more lonesome Suddenly, he saw me sitting right across from him His eyes lit up and he waved at me like a child Although surprised that he recognised me at once (or maybe not but was just sending out a "help" signal), I immediately dropped the things at hand and made my way to him

I crouched down, shook hands with David and asked him how he was doing I did not ask him if he remembered me, as Seiwa had repeatedly stressed back on the first day of the training not to ask

According to the CDC definition, dementia is a general term for impairment of memory, thinking or decision-making skills that affects the ability to perform everyday activities. One of the most important criteria for judging dementia is memory loss, which in turn relates to concepts such as 'personhood' and 'caring' in the discourse of medical anthropology (Zhu 2021: 176). When individuals no longer have a sense of who they are and are unable to maintain their social relations effectively due to memory loss, their sociality is seriously threatened and constitutes a kind of 'social death'- the body may continue to live, but the person is actually gone, no longer present and no longer a person The philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s three semantic clusters in his book The Course of Recognition (2005) are of particular explanatory power here According to his model, people with dementia usually go through three key stages to complete the transition from active to passive status They begin as a sovereign self capable of identifying external objects, gradually lose this ability and begin to suffer judgement from the outside world, and finally reach a point where they are passively recognised by others as an incomplete person

But what is the nature of this obligation to remember and recognise if we owe it to ourselves in order to qualify for complete personhood? Underlying this perception is the profound western presupposition that human beings, as subjects of personhood, should be autonomous and capable of recognising their own social relations; the idea is also deeply rooted in historical development Since the Enlightenment, memory has been considered a manifestation of the mind and, as such, memory impairment has been seen as a great challenge to the integrity of the human person (Cohen 2008: 336) In an era where such assumptions are the

2

during the events

Museum artefacts and collections that we used

dominant standard of ‘personhood’ in the West, it is clear that people with dementia cannot be reconciled with this institutionalised model of cultural and ethical values. Moreover, since the 20th centurywith the flourishing of cognitive and brain neuroscience since the 20th century, the medicalisation of memory has stimulated processes of deconstruction and reconstruction, that is to say thatthat the implications of which has been thati e the deconstruction of human subjectivity has also completed the construction of illness (Zhu 2021: 177) Once a person is diagnosed with dementia, the label of this disease term overrides the subjectivity of the person themselves, and the bystander's view of the person is henceforth dominated by the label, deepening the understanding and inherent impression of the disease in one encounter after another

A society's understanding of illness has a direct impact on the form of care and attention applied to the patient. Euro-American values of individualism have long held personal autonomy as an important criterion for identifying the integrity of the person, and the rise of modern biomedical discourse has further de-socialised illness by placing its roots and treatment squarely in the human brain However, this focus on individuality should not be the only way to define personhood; rather, its perception should be pluralistic and in various states of tension. It is through ethnographic field research that anthropologists have been able to critique dominant but narrowly defined individualistic values and point to alternative possibilities and interpretations for understanding people with dementia, namely that memory loss does not imply a loss of freedom and self Rather, a new type of self-knowledge may develop when a person enters a state of 'relatedness' and dependence on others, rather than being reduced to being merely a passive, cared-for object.

After exchanging pleasantries for a while, Seiwa gestured for everyone to return to their seats As the day began, I realised why she had just seemed so mysteriously excited and understood why so many older people were joining us today - we were going to have a wedding, and David would be the ‘groom’ for the day I started to wonder who the 'bride' was going to be, and the answer soon emerged - it was the mother of the lady who had chatted with David ther and talking to other people, and no wonder David seemed so nervous It all m

The wedding was on Although it was not a real wedding, we basically had everything and everyone needed for a real wedding One of David's friends was invited to play the priest, a few other programme participants played best man and bridesmaid, and the rest of us played guests Suddenly, I heard one of them start humming a song that resembled a wedding march As more and more people joined in, the song became louder and louder and even began to shake the hearts of people like me who were not very familiar with European wedding customs. I saw a few older men, who were a little frazzled at first, whose mouths began to unconsciously match the call of the song The sound came from their throats, vicissitudes and gradual brightening, and their faces flushed as if they had sung it hundreds or thousands of times until the song had long since become part of their bodies.

I saw the shy smiles on David's face, the demented old men who sang earnestly, and the many twilight souls still burning I saw a living 'body of experience', as opposed to the 'body of diagnosis' I had seen in books and clinics Modern biomedicine is so concerned with the latter that it ignores the patient's true self and needs; here, even without their words, I could see their needs being fully met; also here, the normative power relationship between carers and the elderly has been completely subverted In the clinic and in everyday life, caregivers have always played the role of advocates, holding the channels of external communication for their patients, often giving the false impression that they are the true advocates for the latter. But how can this be the case?

Here, we listen carefully to the voices and demands of the elderly and encourage them to actively express themselves in a variety of ways, while the carer becomes a supportive role and we are no longer guided by their opinions solely If we free our perception of ' recognition’ from a single cognitive domain to experience the process of communication, participation and practice, we can appreciate the many other ways in which their capacity to be a person is made tangible And it is through all of this that we see more possibilities in people with dementia The original intention of the “Memories of London” programme was to bring back the brain memories of the elderly with dementia through a series of activities and objects, but it was clear that the effect was rather modest, in the sense that most of the people did not have those entirely back. Nevertheless, does this mean that the programme has failed? I - and the vast majority of participants - think not. Perhaps it was just that the programme was initially designed with some reservations or over-optimism in mind, and we gradually discovered this over the course of the sessions – even if they don't remember, so what? And, had they really forgotten their past?

An increasing number of scholars have begun to question conventional definitions of personhood since the 1990s, arguing that personhood should not be seen as a possession owned by individuals, but rather as an intersubjective state of mutual recognition, respect and

3

A random chat before the day starts

communication Thus, even if a person no longer possesses his or her former memories, so what? The correlation between loss of personhood and the loss of memory is ot natural but always socially constructed, and only with such an understanding, a fundamental change in the assessment of people with dementia and the corresponding care system can be truly ushered in; at the same time, this wave has led to a broader reflection on other more subtle concepts such as 'recognition' at the level of cultural practices

Recognition can be understood not only as an internal emotional or intellectual state of the individual, but also as a social, very concrete and material form of practice and activity (Taylor 2008: 326) Being able to remember others is only one of these activities, as there are countless other forms of knowing how to interact with people: the elderly with dementia in our programme may not all be able to speak coherently, but they are capable of participating in and enjoying activities such as dancing, singing, roleplaying, etc , which all rely on their embodied procedural memory (Taylor 2008: 328) They may not be able to remember and recognise things cognitively, but their bodies respond vividly, testifying to their viability and the fact that they are far from having lost personhood and, consequently, the status of social death Having said this, are

we still unable to overcome the idea that cognition is the defining carrier of personhood?

Regarding the loss of cognitive memory as the signal of one’s incompleteness and social death is thereby a huge ignorance of what it means to be a person Memory in the brain is never the most important thing Its presence or absence does not and should not fully define who we are rather, every word we have said, every interaction we have had with others, every smile or cry we have had, these too are a large part of who we are As memory can be expressed on and through the body, corporeality also matters Even when our minds fail us, the great embodiment of habit remains deeply rooted and functional within (Katz 2013: 311)

Looking back on the whole journey of the 3-months programme, we may not be able to bring back cognitive memories of the people with dementia, but they at least gained joy and respect and a fulfilling experience of the present moment, and we in turn gained a more intimate and comprehensive understanding of them These are already quite enough; from now onwards, as Taylor suggests (2008: 315), perhaps a better and more worthwhile question than "do you recognise me" or "do they recognise us" might be: do we genuinely recognise them?

Argonaut Mixes in the spotlight - music at the margins of empire

by Lucy Bernard

Each month I curate a playlist of global, fusion and protest music to accompany the newsletter. Music is fundamental to human experience and encapsulates culture, struggle and communitas, and I hope each month’s mix might shed light on subaltern sounds.

TheQueenofMbiraMusic:StellaRambisaiChiweshe

Stella Rambisai Chiweshe transformed Zimbabwe's music scene in 1970s (at that point colonial Rhodesia) with her rebellious take on Traditional Shona music The previously male-dominated Mbira music, often thought of as the backbone of Zimbabwean music, was rewoven by Chiweshe Central to this music is the mbira: a ‘thumb piano’ is a small instrument with 22-28 metal keys and a wooden resonator, and echoes of chanting vocals The mbira itself is highly important in Shona culture and is a sort of “telephone to the spirits of people, water, trees and birds”, in the words of Chiweshe herself The instrument was officially banned by Rhodesia’s colonial rulers and by Christian missionaries

As well as her global musical success, Chiweshe is also known for her talent on the screen and stage In 1981 she joined the National Dance Company of Zimbabwe and later starred in film playing Mbuyo Nehanda, the spiritual medium instrumental in organising the nationwide participation in the First Chimurenga of 1896–7 against the colonial rule of the British South Africa Company Nehanda was later executed by the British

The sound of the mbira alongside Chiweshe’s vocals is hypnotic. At her last concert at beloved Café Oto in London she captivated her audience: “If you are listening to the mbira, let go of any thinking”, she told the audience. “Let your mind to do its own thing”. Chiweshe passed away in late January this year, but her legacy and breath-taking sound live on in our monthly newsletter mixes, curated by me. Listen to Chiweshe and many more artists at the margins by scanning the code below.

4

You can listen to this track and others on our Spotify playlists: StellaChiwesheperformingattheMelkweginAmsterdamin 1988 Photograph:FransSchellekens/Redferns

Constructing power: the exploitation of migrant construction workers in the UAE

by Dan Guthrie

The Qatar World Cup made the treatment of migrant labourers in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) a topic of global discussion

From the widely circulated Guardian article claiming 6,500 migrant workers had died since Qatar had been deemed hosts in 2010 (Pattison, 2021), to FIFA president Gianni Infantino’s baffling assertion on the eve of the tournament that he feels ‘like a migrant worker’ (Page, 2022), the plight of the migrant labourer outside the West has perhaps never had this much attention Whilst it is Qatar that has received the most recent coverage, it is the UAE which has the largest catalogue of discourse on the issue, over the longest span of time. The issue is especially pressing given the number of migrant workers within the UAE – estimates consistently put migrant labourers as around 90% of the UAE workforce, with some 500,000 of those being construction workers (Sönmez et al., 2013). To grasp why this exploitation is so prevalent, there needs to be an understanding of both the unique systems of labour management and worker treatment that operate within the UAE, and an understanding of theories relating the power over death. Elements of Foucault’s concept of biopower (especially regarding anatomopolitics) and Berlant’s concept of slow death will be utilised to locate power in the government-employer-migrant construction worker relation, ascertaining what has led to the current situation of exploitation that is now under the global spotlight.

Firstly, the position of migrant labourers must be understood Migrants enter the GCC’s labour market through the kafala system Within this structure, migrants must be sponsored by a specific employer to gain a work contract, enter the state, and obtain a residence To afford transit, funds are borrowed or generated by the sale of homes or livestock (Sönmez et al , 2013) In most of the cases this obviously creates an enormous financial pressure on the labourer since they often find themselves with huge debts and with a family reliant on their work at home Debts can be as high as US$4000; an unsettling figure when construction workers receive, on average, the equivalent of US$175 a month (Ghaemi, 2006: 7) Most significantly for the discussion of power, the kafeel (sponsor) is essentially wholly responsible for the worker They dictate their employment and residency, have the responsibility to inform authorities of changes to the contract, and can even restrict workers

mobility or changes to employment (Ngeh & Pelican, 2018: 172) The government of the UAE has made a large part of the governing of migrant workers the responsibility of employers

The Kafala system is widely regarded as corrupt, so much so that Bahrain, another country in the GCC, prohibited it in 2009 – the minister of labour referring to it as “not differ[ing] much from the system of slavery” (Mahdi, 2009) Postcolonial philosopher Achille Mbembe defined the state of the slave as “a triple loss: loss of a “home, loss of rights over his or her body, and loss of political status” (Mbembe, 2003: 21) Migrants under the kafala system leave their home and move into their employer’s labour camp Their employer has near-total power over the movements and existence of their employees They will often find their passports confiscated, under the guise of this being customary within the kafala system (Sönmez et al , 2013); in reality, it is to control their movements and ensure they do not attempt to return home

Further control is exerted in several ways, including the witholding of workers’ pay Given the immense financial pressure on migrant labourers, this can be destructive to their lives at home, and this immense power can be exercised on the employer’s whim Migrants have no voting rights in the UAE, as the government selects which citizens can vote in each election whilst citizenship is exclusively re s

who cannot speak Arabic, so they cannot read the contracts they sign, or even converse with non-migrants (ICFUAE, 2019: 9); some go further, and hire from a wide range of countries and locations so that their workers cannot communicate (ICFUAE, 2019: 9) The labour camps set up to house migrants are located on the peripheries, so that they are geographically segregated from the privileged classes of the UAE (Hamza, 2015: 90) They report feeling socially excluded from entering parks and shopping centres, saying they are “not people of the city, we live in a labor camp” (Hamza, 2015: 101) Migrant workers experience a holistic loss of bodily autonomy and personhood as they are created as a disposable population Their conditions are more akin to slavery than free employment The Labour Law explicitly prohibits unionising and striking (Federal Supreme Council, 1980),

7

McQue, K (2020) Social distancing is impossible in the cramped living quarters of Dubai’s labour camps, The Guardian. Dubai: The Guardian.

Jebrelli, K (2016) Migrant Workers Dubai Skyline Dubai

8 criminalising any preventative measures by workers to effectively ensure the enforcement of their legal rights. The Ministry of Labour is responsible for ensuring regulations are followed by both employers and employees; however, in 2006 it was reported that “140 government inspectors were responsible for overseeing the labor practices of more than 240,000 businesses employing migrant workers” (Ghaemi, 2006; pg. 6). Furthermore, these inspectors are mainly concerned with the residential situation of the workers, and workplace concerns and hazards are not prioritised (ILO, 2010).

Working conditions in the UAE are dire During the construction of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, the average worker worked 12 hours a day, 6 days a week (ICFUAE, 2019: 11) Death is common The story of Julhas Uddin, a migrant labourer who died when he was instructed to enter a sewage line without an oxygen cylinder (McQue, 2022), is no outlier One report found that between 2010 and 2019, an average of 5866 non-nationals from south and southeast Asia have been dying every year in the UAE (Vital Signs, 2022: 25) Perhaps more shockingly, “1 out of every 2 deaths is effectively unexplained instead using terms such as “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest”” (Vital Signs, 2022: 26) In addition to this, there are many unrecorded deaths, meaning the actual figures are likely higher than the documented 5866 a year It is apparent that the bureaucratic structure has such disregard for the lives of migrant labourers that even their deaths are regarded as of little importance

Thus, the positionality of the migrant construction worker is one of near-constant peril Under immense financial pressure, they are stripped of their identifying documents, and placed in high-risk, low-wage work, where their rights border on non-existent, and they are legally prohibited from mobilising There is no free market in the UAE – due to the kafala system, they cannot leave their employer to join a competitor, meaning the employer can treat them however they please The government has apathy for their wellbeing, from washing its hands of many bureaucratic duties, to a woefully inefficient inspection structure Prohibitions on mobilising, and ineffective and poorly organised modes of inspection, lead to situations where employers have almost total discretion as to the treatment of their employees, and employees are powerless to resist They cannot even be trusted to give an accurate account of death, a consequence of workplace abuse which looms over the construction workers, higher even than the glittering cityscape they are building

For a complete analysis of the power that employers exert over their employees, the most insightful analytic will be a synthesis of two theories relating to power and death The first will be aspects of Foucault’s theory of biopolitics - power as being a ‘right of seizure’, the justification of death as “on behalf of the existence of everyone” (Foucault, 1978: 137) and “the anatomo-politics of the human body” (Foucault, 1978: 139) The second will be Berlant’s theory of ‘slow death’- “the physical wearing out of a population and the deterioration of people in that population that is very nearly a defining condition of their experience” (Berlant, 2007: 754) Berlant’s framework essentially fills in the gaps of Foucault when dealing with oppressive systems that have become the norm for certain populations Reading Foucault in accordance with the exploitation of migrant labourers provides a useful understanding of the development of gaining power. The right of seizure is the right to seize “things, time, bodies, and ultimately life itself” (Foucault, 1978: 136). As demonstrated above, employers in the UAE both actively (through the kafala system, the retaining of passports and the inhumane workload) and passively (through spatial containment and social isolation) seize control over the personhood of the migrant construction worker Their deaths are deemed ro be a non-event - natural causes’ is scrawled as the reason for death, and there is always another worker to take their place This right of seizure is demonstrated by employers and condoned by the government

Foucault’s theory that death is justified as ‘on the behalf of everyone’ must be skewed slightly for this subject. His example rests on the premise of war, detailing how slaughter is justified “in the name of necessity” (Foucault, 1978: 137). he UAE is not engaged in any war in this sense – however, the deaths of these construction workers is on the behalf of those already residing in or attracted to the UAE by low tax rates and theturistic appeal of skylines such as Dubai’s. Here, the government has created an image which employers realize –that of the UAE as a financial hub of the future, complete with soaring glass towers and labyrinthine shopping centres, a monument to consumption and consumerism Death no longer must be justified in the name of necessity; it can now be justified in the name of opulence Anatomo-politics makes up the individual half of the theory of biopolitics It focuses on the reconstitution of man as “a machine: its disciplining, the optimization of its capabilities, the

extortion of its forces” (Foucault, 1978: 139). Its direct relation to power is in the extent to which the powerful body can perform this reconstitution. In making man a machine, it necessitates dehumanisation, as the valuation of the individual becomes what they can do, and how effectively they can do it. Migrant workers are dehumanised and broken down to such an extent that they do not feel part of the population – the government does not concern itself with their wellbeing, and they are herded to labour camps on the edges of cities. Their

A foreign worker waits for the company's bus service to take him home after a day at work (2006) Building Towers, Cheating Workers London, London: HRW

A foreign worker waits for the company's bus service to take him home after a day at work (2006) Building Towers, Cheating Workers London, London: HRW

9 life becomes work – they do not have time for anything else, they cannot access any space that isn’t the camp or the construction site The individual is not only deemed a machine but comes to think of themself as a machine A machine cannot die – it can only break, and with so many other tools at the employer’s disposal, the broken machine is discarded

Foucault notes that power’s highest function may have shifted; it is “no longer to kill, but to invest life through and through” (Foucault, 1978: 139) The employers of the UAE can push life to its limits, to the point of death in many cases They need not exercise the threat of death as a punishment, as their workforce has already been manipulated and reconstituted to have no other alternative –obey to live has replaced obey or die

Despite its usefulness, Foucault’s theory does have its limits Crucially, it focuses on points of crisis, such as war or genocide, as being the situations when the ultimate expression of these forms of power come into being Berlant offers a more nuanced perspective, stating that slow death is “a defining fact of life for a given population that lives it as a fact in ordinary time” (Berlant, 2007: 760) Construction workers in the UAE are not only physically worn down, but consciously deprived of basic liberties; so much so, that they internalise the fact that they are not part of the public, but are instead simply their job title

Berlant offers a more nuanced perspective, stating that slow death is “a defining fact of life for a given population that lives it as a fact in ordinary time” (Berlant, 2007: 760) Construction workers in the UAE are not only physically worn down, but consciously deprived of basic liberties; so much so, that they internalise the fact that they are not part of the public, but are instead simply their job title

Despite protests, and reform in other GCC states, there is no indication the government will do anything to help them The Ministry of Labour fails the migrant worker at every conceivable turn, so much so that its presence becomes phantasmic; the reality

for the migrant worker is dominated slow death, the deterioration normalised to justify the push towards the future.

Another way in which Berlant phrases slow death is “structurally motivated attrition” (Berlant, 2007: 761). This definition again builds on Foucault, as it recognises that the distribution of power may not exclusively be top-down – it can be an intersectional attempt to degenerate certain persons. Both the government and employers disregard the humanity of the migrant construction worker; agents at multiple sites are complicit Additionally, the structural motivation behind this treatment helps to normalise it, especially when this vast group of the population is voiceless by design

To conclude, the migrant construction labourer is dead by design They have been stripped of their identity, stripped of their humanity, and mechanised; and this process has been met with mostly indifference The government of the UAE has absconded all responsibility for their livelihood, and left them in the care of employers who engage in a system comparable to slavery to obtain their workforce, and segregate them from the rest of humanity, and human contact, to further reduce their personhood When one dies, if the death is even recorded, it does little to change practices; construction activity in the UAE is on an upwards trajectory (Illankoon, 2022), and this is only likely to continue The normalisation of their subjugation has led to their lives being disposable, and those with the power to change the system either are disinterested in changing it, or actively participating in maintaining it

Further work can be done – issues of racism are also reported to be prevalent, as are cases of gendered discrimination, leading in some cases to forced prostitution (Sönmez et al , 2013) Additionally, this work focuses exclusively on the construction sector – a comparative with the treatment of domestic or hospitality workers could illuminate other manners in which the power to subjugate and oppress is used It is likely that the GCC will only become a more and more crucial area to understand as time goes by – they, by no account, are planning on slipping into obscurity, continually developing their hospitality sectors and tourist draws, the World Cup being the most major recent example of that The forms of power that operate within the UAE – the mechanisms by which they came to be and the methods which reproduce them – must be understood if any effective action is going to be taken against them

Globally, the erosion of personhood and domination over the humanity of an exploited workforce must be studied These practices are not unique to the UAE and exist far outside the sphere of construction Utilising the framework presented here - the production of the worker, and what impact this has on their perceived humanness, read alongside theories of power production – could provide for a more developed understanding of the human cost of progress

Britannica, T Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, December 8) Burj Khalifa Encyclopedia Britannica https://www britannica com/topic/Burj-Khalifa

Madonna and Madonna: The Politics of Finding God (or the Mother Mary) in the post-modern world.

By Inayah Inam

Michael Tolkien’s 1991 film ‘The Rapture’ follows a telephone operator stumbling on an evangelical sect in an office break room, who believes ‘The Rapture’ (Judgement Day) is near. The film shows how the Christian desire for salvation still surrounds us today, despite the tendency to depict our age as secular. Contemporary Christian sentiments are underpinned by political contexts, embedded in wider political phenomena such as decolonisation and globalisation. An interesting site to look at how religious sentiments are underpinned by such politics are religious apparitions because of their nature as crossroads between several political actors in the church such as church’s institutions, followers and correspondent geographical areas; a church’s core and periphery.

In ‘Mother Figured’ (2015) De La Cruz writes about religion in postcolonial times She recounts the incidence of the ‘Marian Apparitions’ after World War II in the Philippines and traces the legacy of a hierarchical (and elitist) Catholic Church, resistant to legitimising these divine miracles as they did not fit the established and Eurocentric framework of legitimate miracles One of the first apparitions, The Lipa miracles (1948), during which the Virgin Mary appeared to a nun in the Carmelite Monastery Teresita, can be read as a post-colonial critique of church, state and the supernatural What constitutes the extra-ordinary or ‘divine’ in this case of this apparition raises ideas about what constitutes religious legitimacy and gendered ideas of ecclesiastical credibility De La Cruz particularly elaborates on the gendered

experiences of devotional subjects, and the invalidation of Teresita’s claims by the church. Teresita’s testimony was dismissed as “pure imaginations” (2015:255) I argue the discreditation of Teresita’s claims were patronisingly discarded on the grounds of misogyny and sexism

However, an apparition’s effects are not totally determined by the church Although their legitimacy may be established by the church’s hierarchy, they can also be understood as ‘spectacles', having effects on the collective imaginary at a grassroots level De La Cruz notes that in another set of apparitions in the Philippines, the ‘Agoo Apparitions’ of 1993, the material spectacle of the weeping Mary Statute captured the public devotional spirit with an onset of religious devotees and curious onlookers who descended on the town This phenomenon transcended usual social divisions deeply marked in Philippines’ everyday social life, as it attracted working-class people alongside “Filipinos of the highest status and celebrity” (De La Cruz 2015: 2) The upsurge in religious mobilisation and participation notably at Mass and devotional practices alludes to the potency of the religious spectacle and the symbolism of Mary as “a transcendent figure with a singular identity (2015:7) This finds parallels in other ‘unifying’ and universal religious figures which carry political capital as well as religious capital For instance, this is the case in Islam for Imam Mahdi, a messianic figure reported to be a ‘saviour’ who will be sighted near the end of times News of potential sightings of this figure gathers attention widely in the Islamic world and there have been multiple claimants to the title The sighting of these religious apparitions should be examined particularly as a ‘postmodern phenomenon’ (Vasquez, Manuel A, Marquardt Marie F 2000) According to Pelikan (1996), almost 50 apparitions have occurred since 1980, in places as diverse as the USA, Nicaragua, Brazil, Rwanda and Australia The proliferation of Marian apparitions can be situated in the “complex process involving the global creation of the local” (Featherstone and Lash, 1995: 4), whereby traditional local religious practices and discourses enter large-scale dynamics like worldwide Church politics, such as the Vatican's New Evangelization project, all of this being mediated by globalised media like Internet and TV

De La Cruz’s examination of Christian apparitions in the Philippines remind me of a similar controversial event on the other side of the world which garnered the disapproval of the Catholic Church - Madonna’s 1989 “Like A Prayer” music video which depicted a black man being wrongfully arrested for the murder of a white woman Madonna, witnessing the falsity of the accusation, prays to a ‘black saint’ resembling the individual and later frees him The video engages in a vigorous spectacle of religious ecstasy, interracial love, and anti-racist politics The lyrics “When you call my name, It's like a little prayer, I'm down on my knees, I wanna take you there” are riddled with innuendos and present an over-frenzied, feminine display of religious passion Although Madonna’s reputation as a controversial popstar who relishes in the publicity machine of outrage and provocation was bashfully fun in the Western media, the subject matter still offers a mirror to the Philippines’ mediatisation’s of religiosity in 1990s Funnily enough, Madonna’s Rebel Heart World Tour in 2016 which stopped in Manilla, was described as the “work of the Devil” by a Catholic newspaper Why is the Catholic Philippines the favourite

5

A still from 'the rapture' 1991

"venue for blasphemy against God and the Holy Mother?” (2016) is what a Filipino archbishop at the time Ramon Arguelles posted on the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines' official website.

I think the irony can’t be overstated when a Filipino Catholic institution attacks a performer called ‘Madonna’, who adopts the name of Mary Mother of Jesus for her art. Thus, Madonna’s, much like Teresita’s, devotional display, deeply embedded in a gendered dynamic, is being left out by what is defined as ‘religiously legitimate’ by the Catholic Church. However, if as devotional displays Teresita’s and Madonna’s acts are deemed ‘illegitimate’ they remain, despite their controversy, in the public imagination.

These religious displays that straddles an uneasy balance between institutional delegitimization and public visibility bring to the fore the question on truth, typical in the postmodern era As De La Cruz notes, “how important is the truth?” (2015:145) The hierarchy of Catholic devotion in which at the top lies the Vatican’s approval and at the bottom is conspiracy or fiction, syncretic or folk embodiments of Catholicism exist Image of Madonna in her controversial Music Video “Like A Prayer” in an uneasy ambiguity. This tension between sanction and scepticism, demonstrates the reality where due to critical media and political discourse, objective truths and absolutes are not so easily accepted. Online mediums, the proliferation of social media, allow people to debate, discuss and form narratives where everything is just a matter of subjective perspective. The church who didn’t validate Teresita’s apparition’s, nevertheless fed into the culture of folk catholic mysticism in the Philippines, as part of a wider experiment in religious ‘glocalization’ (Vasquez, Marquardt 2000). If religion is being re-imagined, re-localised and reconstructed for those originally ‘compliant’ masses who are modern subjects of a globalised world, where does the line end for experiences ‘worthy of belief’?

The existential and the political: anthropology and Chris Killip

By Iacopo Nassigh

The first retrospective exhibition on the work of Chris Killip (1946-2020), a Manx photographer who has mainly worked in the North of England terminated just one week ago at the Photographers gallery, Soho Killip’s work expresses a disenchanted gaze on the life Northerners throughout the 70s and 80s, during which the closing of factories and mines left many people without a job However, Killip’s photographic gaze is not trying to romanticise the resistance of those who remained in the North His photography is embedded into a deep awareness of the need of solidarity and amplification of these people’s lives, and not of pity for these marginalised groups With this awareness, Killip spent months and years with the communities he photographed, such as the years he spent in Lynemouth, Northumberland in the early 80s staying in his van among a community of workers in an open-air coal mine by the sea

Even if sharing the same basic experience of an anthropologist doing prolonged fieldwork it seems to me that his poetic eye was seeing something quite different from what an anthropologist normally sees Where anthropologists see resistance to structural oppression Killip was able to see the human capacity to find relief in despair, to enjoy life as it comes despite the world burning around His image of a girl playing with a hula hoop or the pictures he took of young punk man going crazy at rave speak not just of people that find meaning in cultural structures, as old Geertz would put it, but people that actually enjoy themselves without caring much for a while about anything else This existential quality of Killip’s photography is what I will carry with me other than an even stronger conviction now that things are not just suspended in cultural or political structures Instead, if one has the eye to see this and suspend disbelief for a second, things can be appreciated for themselves, as moments of emotional explosion that maybe just a photograph can express

6

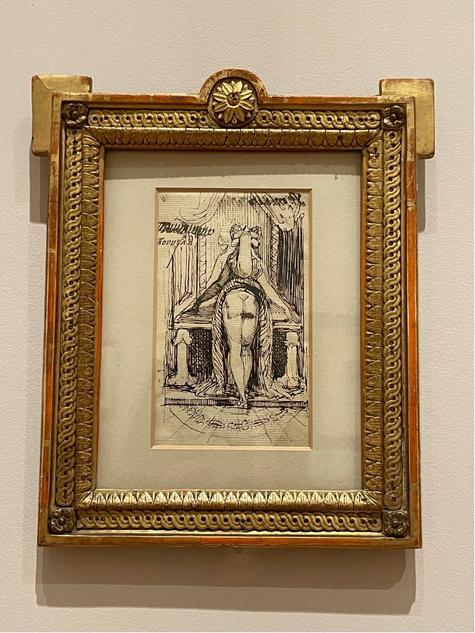

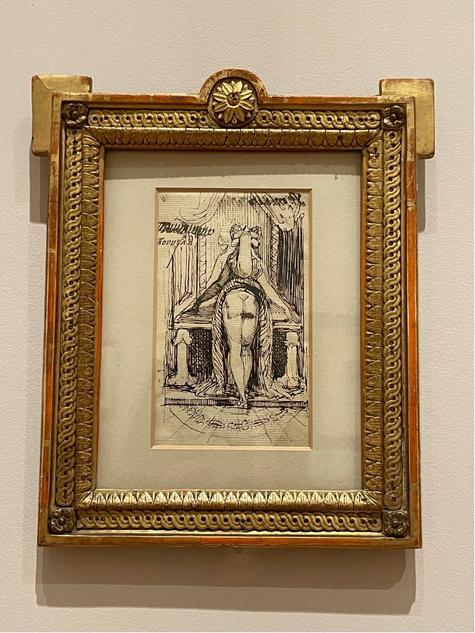

Fuseli and the perceptions of womanhood

by Claire Ding

Last December, I was fortunate to see the work of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), one of the most eccentric 18th century European artists, at the Courtauld gallery The exhibition, Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism, explores notions of sexuality, gender, and womanhood, which were constantly being challenged and reshaped during the Victorian era An array of his private drawings were displayed, foregrounding different courtesans and his wife, Sophia Fuseli, as the centre of attention Breaking away from female stereotypes of submissiveness and maternal virtues, Fuseli’s work of the Modern Woman destabilises traditional understandings of womanhood In my opinion, however, his reimagination ultimately does not seek to empower women and continues to confine women in archetypal roles, subjugating them to the aesthetics of an alternative, but nonetheless male, gaze

Fuseli does, however, showcase the multiplexity of womanhood by subverting female archetypes through the lense of the appearance and clothing of courtesans In ‘Sophia Fuseli, Standing in front of a fireplace’ (1791), Fuseli casts his wife in an elaborate drapery with a complex hairstyle, reminiscent of a courtesan. This depiction is further reinforced by her pink cheeks and red lips, and green facial complexion recalling concurrent tuberculosis aesthetics. Interestingly, Fuseli situated Sophia in a domestic setting, marked by the fireplace, which is affiliated with notions of maternal love and care, creating a stark contrast with an erotic appearance associated with women of a dubious moral character and wild sexual passions. Such oppositions can also be seen in ‘Sophia Fuseli, Seated at a table’ (1790- 91). On one hand, Sophia exemplifies sexual immorality, portrayed by her seductive gaze, voluptuous lips and translucent drapery; the sewing basket next to her, on the other hand, associates her with virtuous domesticity. By doing so, Fuseli converges and distorts Victorian female archetypes of the angel in the house and the fallen woman, thus freeing perceptions of womanhood from conventional understandings.

Fuseli further disrupts the perceptions of womanhood by turning women into powerful perpetrators who commit sadomasochistic acts It has been suspected that this darker side of Fuseli’s imagination was influenced by the writings of Marquis de Sade In ‘Paidoleteira’ (1821), the courtesan is depicted as committing infanticide using a hairpin and the drawing has a Greek inscription of ‘child murderer’ Similarly, in ‘Woman with long plaits teasing a figure trapped in a well ‘(1817), Fuseli positions the woman as powerful, not only presented by the subject matter itself but also the use of a hierarchical composition Nevertheless, the empowerment of women in Fuseli’s can be questioned as it appears to serve and appeal to the tastes of the libertines, who likely would have been Fuseli’s clients, rather than giving genuine agency and autonomy to women In addition, the ubiquitous male gaze not only penetrates his sadomasochistic imagination of women, but also his drawings of female fashion A recurring motif in his work is the juxtaposition between geometric or phallic shaped hairstyles with an open, provocative display of the female body, which is particularly prominent in ‘Kallipyga’ (1790- 92)

The exhibition ultimately opens a broader discussion of womanhood and has the power to define it Fundamentally, Fuseli as the artist, has the p to imagine and represent womanhood based on his fantasy This, neverth is a product of the broader social climate, as well as the preferences of his

clients; upper-class men. Perceptions of womanhood continue to be written over by the male gaze in art, meaning that women in the drawings of Fuseli are empowered, but not dignified Following further waves of feminism, as well as the rise of female artists in modern and contemporary art, increasingly we see perceptions of womanhood on a much more individualistic and personal basis, by women themselves Artists such as Fuseli can be appreciated for their socially innovative nature, but should be admired whilst recognising their historical contingency.

10

Intimacy Economies and Reality Dating TV Shows

by Ayomide Asani

Reality Dating TV shows have captured the attention of the general public and academia alike. Infused with entertaining conversations, beautiful bodies and details into personal life, there is something in these shows for everyone. Many dating reality TV shows have received the same critiques that other reality TV has, described as vapid, silly, and superficial. But academia has shown that shows like this filled with false realities have small nuggets of ‘truth’, not just in their content but in their continued existence. Although seemingly distanced from reality, they reflect societal attitudes to romantic relationships and more.

The hyper-surveillance in many of these shows makes the audience into something akin to an anthropologist observing the field site and the behaviour of participants. ‘Love Island’ itself perfected this formula, placing a group of strangers into one villa with nothing to do but get to know other participants, whilst their interactions are streamed on TV. A ‘Love Island’ hierarchy is created in these mini societies, at the top of which there are the ‘strongest couples’ and the most liked contestants within the villa. The beauty standards and behaviours that dictate this hierarchy replicate those which we see in the real world, as Eurocentric and heteronormative beauty standards shape contestants' dating habits and performances. What is also intriguing about these shows is their embeddedness in the wider capitalist context The contradiction of being part of a profit-making industry yet simultaneously trying to portray love as removed from this is reflected in the participants’ attempts to disguise their motivations for participating in the shows With prize money awarded to the favourite couples, contestants who show monetized motivations for wanting to win come across to audiences and fellow contestants as distasteful Perhaps this highlights our inability to realize that money does often dictate our pursuits of love ‘Love Island’ as a dating show started with the intention of making money, and the participants behaviours can’t be understood outside of this framework

Love does not exist detached from a capitalist society, as it is embedded within it and shaped by it The commodification of love propels consumerism and props up the entertainment and media industry In terms of consumerism, jewellery brands often utilise public conceptions of romance to sell products Major holidays like

Christmas and Valentine’s Day propel the idea that love can be bought through gifting commodified products Moreover, the romance film and tv industry has utilised romantic themes to keep audiences’ attention Netflix shows like ‘Bridgerton’ combine the popularity of romance in fiction and the periodical film genre to capture our attention and keep us consuming The ‘golden age of rom-coms’ from the 90s to the early 2000s brought in massive amounts of profits for mid-budget feature films Notions of romance leak into almost every film genre within the entertainment industry, from dystopian films to murder mysteries Romance is likely to be integrated into these stories because of its ability to capture the audience's attention

The show ‘Too Hot To Handle’, adds a fascinating spin to dating reality tv shows. The financial reward element is still strong, but punishment is also introduced. This punishment aspect is through the form of fines placed upon the contestants who act upon their sexual desires, so that sexual touching, kissing, sex, and selfgratification are banned. If they are caught on camera doing any of these things large amounts of money will be deducted from the prize fund. This aspect of the show can be both problematic and comical in that the contestants end up policing the sexual activities of one another. When individuals deviate from the rules, it's the responsibility of the group as a whole to discipline them for disobeying the rules of the retreat. If they don’t conform, they are kicked off the show. These rules about sexual behaviour in ‘Too Hot To Handle’ portray a popular theme, namely that withholding sexual intimacy is what creates meaningful connections. Within western societies, it is common to distinguish between sexual and meaningful relationships, stemming perhaps from a masculine idealisation of the need to discipline the body and natural urges to have a successful lifestyle. In such idealized lifestyles, sexual temptations are erased or limited to a secluded sphere while often homosocial relationships are valued as the essential ones. Take the idea of having sex on the first date - this is a debate that is constantly brought up when discussing dating habits There is an assumption that having sex on the first date means that you cannot take the relationship seriously because it is purely sexual and not emotional It reinforces the notion that ‘having sex too quickly’ weakens one's ability to create a long-lasting connection

11

More than anything these shows reinforce pre-existing body and beauty standards rooted in heteronormative ideals. The men in the shows tend to have heavily muscular bodies, and gyms are installed within the villa to accommodate this. For women in this show, a slender body is essential, whilst emphasis on curves and hair colour is imperative. Hyperfocus on bodily details is another aspect of this, highlighted in the fact that when women enter the scenes, cameras zoom in on their bums and legs. When men enter, the focus is similarly on their stomachs and arms. Women and men are also separated, reinforcing heteronormativity. In the mornings men and women separate to debrief on the state of their relationships so far. Women get ready in dressing rooms whilst the men get ready in the bedrooms. Every arrangement is thus underlain by a strong distinction between men and women. When everyone gets ready for dates, the tradition stands that the girls descend the staircase whilst the guys stand and watch. The women are presented and displayed to the men, reinforcing the male gaze on feminine bodies and portraying men as objectifying agents

As an avid watcher of these types of shows, I always find it interesting how societal issues manifest in these isolated villas that insist that they are detached from the outside world It is clear however that these shows actually reproduce aspects of the intimacy economy at play in our wider society and operate as magnifying glasses into details of our Eurocentric, heteronormative and capitalist world

OnTheBansheesofInisherin

by Carli Jacobsen

Martin McDonagh’s work is recognisable as a masterpiece at the first string of Colm’s violin The film tells of the relationship between Pádraic (Colin Farrell) and Colm (Brendan Gleeson), who suddenly begins to imagine a future greater than one that has Pádraic in it Only in the final minutes of the film did I come to terms with Pádraic and Colm’s relationship to be a stab at the Irish Civil War: After endless threats by finger(s), and countless attempts from Padraic to reunite with Colm, a war between the two men begins By the closing scene, one may have completely forgotten why exactly they were fighting in the first place

It took a moment to decipher exactly who plays the Protestant and who plays the Catholic, yet Pádraic and Siobhan's (Kerry Condon) dedication to the Sunday mass and the Banshee, being Mrs McCormick (Sheila Flitton), whom they host for the occasional dinner, while Colm has doubt over the oracle telling of the Banshee and struggles to identify sin in his own life during his confessions Although this is confirmed by Pádraic’s slagging of Colm’s mispronunciation of Irish phrases and his high regard for Mozart, claiming Colm has begun to sound Anglo And when Pádraic places the ultimatum to resolve the friendship, or burn Colm’s house at 2pm, it is a mirrored moment on the 27th June 1922 when Michael Collins' ultimatum to the four garrison to surrender before 4am At 4:15 on the 28th June, Collins bombarded the Four courts with a pair of British field guns

McDonagh embarks you on a journey of brilliant orchestra, cinematic candy of rolling hills and cliffsides, and a dark humour of catholic mockery that is reminiscent of the 2016-2019 dry witted Fleabag series, produced by, written by, and starring Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who also happens to be McDonagh’s partner The Banshees of Inisherin is a beautifully conducted period piece who’s meaning transcends in time frame, making one laugh and perhaps cry through moments of hostility, rejection and revenge that cannot be separated from the ongoings of personal battles and conflicts in contemporary politics

12

Involution in China: the appropriation of a political critique by a neoliberal workplace

By Jingye Tang

“What we have here is pattern plus continued development The pattern precludes the use of another unit or units, but it is not inimical to play within the unit or units The inevitable result is progressive complication, a variety withinuniformity,virtuositywithinmonotony Thisisinvolution ”

-- Alexander Goldenweiser (1936) in Geertz (1963:81)

“Neijuan (“ 内 卷 ”) is the scenario in which vicious competition emerges among dagongren (“office jockeys”, a Chinese internet buzzword from 2020), resulting in the gradual worsening of their working conditions and subsequently broadening the scope of exploitation that the capitalist class can imposeonthem.”

-- Adam, an accountant from my fieldwork which was conducted in an accountant agency in Shenzhen during July, 2021

The theme of this article is 'involution': a concept with the ability to unite Goldenweiser and Adam’s ideas despite their distance in time and space – and despite the fact that they had never heard of one another.

What the American anthropologist was describing is an aesthetic pattern that he found in the “primitive” art of the Māori: an art style which was trapped inside a fractal cycle of repetition and reproduction of the same motifs over and over again. In this cycle, progress in creativity and the difference in aesthetics was only marked by the chronic increment in the number of motifs in a given area (Goldenweiser, 1936 in Geertz, 1963:81).

A paradigm like this, filled with contradictions and obstacles stemming from the internal lacking of creative energy was then summarized as “involution” Upon research in Indonesia, Clifford Geertz (1963) adopted “involution” from Goldenweiser as a concept in his analysis of the Javanese agrarian economy Under the double pressure from colonialism's embargo of productive equipment and the agrarian economy’s saturation of labor supply, the result was an economy of internal complexification and, at the same time, no growth in productivity Phillip Huang (2002:6) first re-interpreted Geertz’s theory and translated “involution” into Chinese, terming it neijuan (a portmanteau joining two Chinese characters, “internal” and “spinning”) Although Huang’s re-interpretation of Geertz has been contested (Liu and Qiu, 2004; Pomeranz, 2003), neijuan as the Chinese translation of involution has mushroomed in Chinese popular discourse since Huang’s work – and it has assumed a life of its own as a term that captures the zeitgeist of contemporary China

My interlocutor Adam, meanwhile, did not refer to Goldenweiser, Geertz or Huang in his understanding of neijuan In fact, Adam had not heard of any of these writers; he also did not elaborate on what he meant by neijuan, taking it as a self-evident term For Adam, neijuan conveys a chain of regress which generates suffering The word was used by him to refer to a phenomenon that he found in his labor as an accountant, namely the gradual demise of working conditions including worsening wage rates and increasingly longer working hours– and it is a common feeling shared by all eight members in the office where I

did my fieldwork, and many more outside of it. In 2020, neijuan was ranked as one of the ten most popular internet buzzwords in China and managed to outlive all its competitors on the list with unassailable popularity even now.

Moreover, as exemplified by the definition that Adam attributed to neijuan, the virality of the term has coincided with an apparent deacademization of the concept and an ostensible unmooring of its history within qualitative social science. Of course, scholarly articles that trace the origin of neijuan in China and explore its meanings predate this boom, but with the adoption of neijuan in Chinese colloquial language, references to it no longer rely solely (if at all) on academic exegesis for their meaning; instead, the term is used to describe one’s own everyday experiences and observations Indeed, I have come to understand how this term provided an avenue for a young urban population to articulate their worsening working condition in a bold and straightforward manner

Manager 1:

“I don’t want our team to be in the exact same situation as the beginning of the year. All of you were in the “American time zone” at the start of this year – no exaggerating. You worked till four in the morning and came to theofficeatoneintheafternoon.Isthisahealthyworkingschedule?Isthis a sign of high efficiency? Our clients were having difficulties communicating with you In our new round of work in the mid-year, everyone,please,leaveat9:30p m atthelatest ”

Manager 2:

“Indeed, our company requires you to engage in result-based work, not time-based work We feel as if you like overworking for long hours in a war of attrition Efficiency and teamworking needs to be improved immediately”

In the afternoon of my forth day at the company, I observed what seemed like a pep talk at a departmental meeting in which attendance by all team members was demanded The managers wanted to address the supposed issues with the team’s working

13

A Ceplok patte, a type of Javanese batik pattern which can also be described as an involuted art form

efficiency and the absence of a (good) fenwei (“atmosphere”) among the team The appearance of these two senior managers in the same room was a rare event; the managers’ speech was an explicit denunciation of the working pattern of their team: a daily work-time rhythm that inverted the usual nine-to-five in a stark way that conveyed the sense of living in another time zone This degree of overworking signaled to the managers unhealthy competition among team members to the extent that it resembled “a war of attrition”

Everyone in the room sat silently None took objection or expressed shock One manager then began calling everyone to take turns to introduce themselves and to articulate their expectations for the future working intensity At this point, a worker next to me suddenly spoke of their experience at the start of the year With a serious and mildly emotive tone, they refuted the claim that they “liked overworking” and emphasized this point with two knocks on the table They lowered their head, it seemed that they were secretly wiping their tears On the first day of my fieldwork and right next to me, there was already a silent protest against the grievance from work It left me shocked and speechless

It was then my turn I announced my ethnography project on neijuan in front of colleagues and especially in front of the project management team in order to negotiate informed consent to conduct my research As soon as my brief introduction concluded, I was greeted by an immediate response from one of the managers:

“Neijuan? Oh, dear fellow student, you are in the wrong place for investigation! Unfortunately, we do not have neijuan in this office!”

The project manager burst into laughter spontaneously Yet as he gazed around the room expectantly, the manager only found some awkward grins from colleagues, squeezed out of the corners of their mouths At this moment, I observed a discernible divide about the office members’ interpretation of neijuan

Neijuan is the blue line, other words came from the list of 10 most popular internet buzzwords article Source: https://index baidu com/v2/index html#/

It is evident that project managers and my colleagues alike were tied up in a regressive process of involution. The focal point of Geertz’s involution theory is precisely how low efficiency and productivity stagnation of the Javanese economy combines with the political economy’s inhibiting effects (such as Dutch colonizers’ containment of any productive capital to be introduced) to resolve the problem. On the workers’ side, One colleague said to me that accounting work was basically “complexification of the smallest number” and that even the smallest numerical discrepancies had to be assessed and accounted for. Thus, in trying to satisfy the requirements of producing accurate figures in reports with a poressing workload and ever-changing requirements from the management and clients, forced them to variously make sense of involution. However, Management too was facing an evident double crisis that brought involution as a forefront issue: the demands from clients were difficult to fulfill at current levels of productivity, eked out by long hours of work At the same time, the lack of new recruits and experienced employees has been a troubling issue In fact, in August 2021, when both of the managers were present in the office, their main topic of conversation was the number and names of those who resigned

Being an ideal employee in my fieldsite – as elsewhere in contemporary China – is fraught with various involuted ethical paradoxes I observed three key virtues that management considered indispensable for such an ideal worker to embody: “gaoxiaolv” (“high efficiency”), “gaomingandu” (“high receptivity” to suggestions), and “zhengnengliang” (“positive energy” ) Yet from the perspective of my colleagues, this ideal type is hard to embody and is fraught with paradoxes For employees, overworking has been routinized and normalized – and yet also variously ridiculed In the words of the managers, overworking was unmoored from a personal ethic of self-sacrifice and had instead become an indicator of low efficiency This had a direct impact to the workers’ bargaining power with the management team, as one member observed:

14

"Before quitting, L always stood up to the manager and told her to stop demanding that she stay in the office [after already long working hours, probably after 11:00 p m ] L even dared turning their phone off during annual leave But even then, the manager still wanted L to stay around becauseLisgoodwiththenumbers "

However, in everyday workplace interactions , “neijuan” or “juan” (shorthand for “neijuan”) was not frequently mentioned and in fact tended to serve to describe trivial matters, almost always in a teasing tone. For instance, during lunch time, when a colleague seemed reluctant to leave due to being preoccupied with their workload, another colleague would typically walk in front and say, “biejuanle” (“stop juan”). In another instance, when a different colleague was choosing which kind of food they would order for dinner and subsequently chose “qingshi” (“light food”, a type of food that was suggested to be healthy in ingredients and served lightly), another colleague would hover over and jibe, “you are juan on food now [too]?”.

This limited usage can be linked to the fact that the workers have identified real and personal obstacles in their career. The belowaverage salaries (compared to other high-tech companies who operated in the same area) and the managers’ behaviour combined to generate shame and indignation for workers. In response to the ideal worker figure that evidenced the three virtues, the accountants often self-effacingly employed a four-point inversion of it to describe themselves: “dixiaolv” (“low effieicny”), “dimingandu” (“low receptiveness”), “funengliang” (“negative energy”), and the newly added “zhizaomaodun” (“seditiousness”) in response to the newest solution raised by the management team to deal with the current crisis – teamwork.

Writers and social commentators have noted that neijuan emerged on the internet since April 2020 and has increased in virality ever since (Wang and Ge, 2020) This is highlighted by the prior graph which depicts its increased popularity, and through the qualitative responses of my interlocutors In a group interview during my fieldwork, the accountants in the office spoke about when they first saw neijuan on the internet The responses ranged from May to September 2020 and for some, a few months later than that One accountant noted that they first read “neijuan” in May 2020 in an article addressing the increasingly competitive dating “market” in which the pursuit of love had been increasingly based on valuations of the candidates’ wealth and university degree

Another accountant noted that their discovery of neijuan dovetailed with a personal panic that they had about the sudden “grade inflation” of the university degree/ranking of the new interns and colleagues around soon after returning to work in September 2020.

However, despite the seeming novelty of neijuan in the public gaze, the use of neijuan in public discourse in China has historical roots. Attention to involution as a helpful way to describe a negative paradigm of living or working has emerged in China over the last decade . For instance, an online article published by the Daily News of Guangdong in 2014, aptly headed “Involuted Life”, introduces involution in the following manner:

There is a shepherd on the hill who tends his sheep every day and a pedestrian who came by stepped forward.

Q: What are you doing?

A: Shepherding.

Q: Why are you shepherding?

A: To earn money.

Q: Why are you earning money?

A: To find me a wife.

Q: Why are you having a wife?

A: To have children?

Q: Why are you having children?

A: So that they can help me with shepherding

This dialogue may appear amusing, but most people do live in such cycles: what drives us to work or study hard may actually be our desire to maintain our current way of life

This life is an “involuted” life ”

The moral of the story is simple: step out of your comfort zone and you might live a better life However, its mention of involution in the take-home message complicates the plausibility of it, because the author seems to overlook the essence of Geertz’s notion of agricultural involution: the wider context in which the so-called “internal complexification” or the de facto stagnation of productivity occurs On the contrary, the story’s author’s proposed solution to involution seems to pivot solely on the agency of the individuals; the simplicity of pastoral life and the desires of the shepherd described in this article appear to convey a primitiveness in the mindset of individuals who live an “involuted life” The incongruence between this story and scholarly conceptualizations might originate from the fact that the author later inaccurately describes “involuted effect” as a theory from the discipline of

Interpreting

the term literally, neijuan denotes a pattern of inward spiral

The 996 working schedule have come to the fore in the last years, with the increasing neoliberalisation in China

15

psychology, limiting the relevance of Geertz’s discoveries in Java to a case of “repetitive cycling without progress” as the author puts it

It is hard to speculate what the influence of this allegorical story is on the emergence of neijuan as a popular Chinese vernacular Nonetheless, similar didactic short stories that emerged before the virality of neijuan share many features with the above tale: unbreakable repetitions and loss in productivity from a “managerial” perspective. That is to say that such stories attribute agency for the solution to neijuan to the individual and largely decontextualise human subjects from their structural, political economic setting, seemingly misapplying Geertz’s insights. I call such works with these features as exemplifying the “shepherd paradigm” to involution/neijuan – these mark the starting point of the non-academic usage of neujian, which endures in the commonsense meaning of the term today.

With the popularization of neijuan in 2020, increasing scholarly attention went into tracing the origin of neijuan The resultant analyses consisted of a more accurate alignment to the term as expounded by Geertz and Huang than the shepherd paradigm For instance, on Baidubaike, the largest encyclopedia website in China, a total of ten references are dedicated to the entry of neijuan However, this modern usage cannot be considered as a radical break from the previous paradigm In this refashioned meaning neijuan seemed to detect the responsibility of involuted life in people themselves, dismissing the structural motifs that lead people to experience neijuan When I tried to recover the original meaning of the word with my colleaugues, I always reached a dead end On one occasion, after bringing up Geertz’s four-point definition of involution to a colleague (of which the last point refers to “the self-sophistication of the economic system”), she turned to me and asked if “involution” was perhaps actually a good thing. Awkwardly, I had to remind her that it was a term that denotes social critique. On other instances, when I began raising the subject of “zhidu” (“the system”) in front of my colleagues I always found them unresponsive. This has been an ethical issue which concerned me in my fieldwork. The incorporation of the political economy is, however, a critical feature for conceptualizing involution in a systematic way. Without paying attention to the political and economic forces which generate the “involuted life”, there is a risk that the concept of involution becomes redundant

In an online post published in a Chinese video game forum in 2010 which was titled “involuted: the shortcomings of the social structure of World of Warcraft (WOW) and their consequences”, the author analyzed what he believed to be wrong in his beloved video game community In his analysis, he challenged the then claim “is this just a game?” and suggested that the political and economic implications of World of Warcraft must be taken seriously Describing it as an aggregate of social relationships between players and exploring the premise of a world structured by involuted stagnation, the World of Warcraft community according to his analysis was indeed subject to a sweeping kind of transformative change just like an actual society. In the conclusion, he observes: 'How different can the transformations in the video game WOW be to the social problems that plague the people of our country? To understand our games is also to understand our reality'. In hindsight, to my colleagues/interlocutors and me, his analysis appears prescient. Yet for my interlocutors, their jobs do not afford them the privilege of simply ‘turning off’ and leaving the game, let alone a reflective space to question their workplace as a ‘game’ in isolation from the requirements real life In the reality of being forced to deal with involution in the workplace, they come to see themselves as subjects becoming lesser versions of themselves, being twisted and folded by the swirl that seems to pull everyone inside Thus this refashioned, vernacular use of neijuan becomes the way Chinese workers try to express their material feeling of entrapment without talking about what is the unmentionable cause of it, “zhidu” (“the system”)

www.the-argonaut.com

Anthro.Theargonaut@lse.ac.uk

Instagram: theargonautlse

Twitter: @LSEArgonaut

16

A foreign worker waits for the company's bus service to take him home after a day at work (2006) Building Towers, Cheating Workers London, London: HRW

A foreign worker waits for the company's bus service to take him home after a day at work (2006) Building Towers, Cheating Workers London, London: HRW