From the studio

Claudio Palavecino Llanos

Selection of academic activities 2014-2024

Claudio Palavecino Llanos

Selection of academic activities 2014-2024

Architectural Design Studio I and II 2nd Semester 2014 - 1st and 2nd Semester 2015

Professors Alberto Fernández and Claudio Palavecino; Teaching Assistant Sergio Cortés

Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Chile

The teaching of the architectural project studio is a learning action for all those who come together in it because it is a space for research through design. The studio is configured as a laboratory where project theses are tested, executed through speculation, a constant questioning of what is known and how this knowledge is useful to expand the limits of our discipline. In this sense, the studio assumes uncertainty and questioning as the only possible path of action, and seeks that all its members develop curiosity, enthusiasm for knowledge and intellectual rigor as the only acceptable conventions. In this way the studio is built as a learning body for students and academics, where the latter test their theories and risk their own conventions about the discipline.

During 2014 and 2015 I developed this approach to the project studio in conjunction with Alberto Fernández at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of Chile. This proposal partly reflects the concerns that both academics had begun to develop in our postgraduate studies and that we wanted to explore in a fully speculative studio, which would help students to ask themselves new questions and generate new knowledge from design.

The first experience was the Competition Studio, which we used as an opportunity to question the typology of squares and public spaces. This first initiative laid the foundations for a second studio, oriented to the study of the scale of the building in contrast with the scale of the city. The thesis behind this approach

was to study how project strategies and arguments could be translated, inherited, or reinterpreted from one project to another, even when the conditions of these were radically different. In this sense, we tested two conditions, on the one hand the negotiation between what is desired as a project and the resources available to achieve a satisfactory outcome, under time constraints that forced the students to ask themselves new questions: could the design decisions of an urban grid be applied to a smaller scale architectural project, could the same strategies of occupation and densification be translated into formal and tectonic configurations of small buildings, what is the limit between object and context, and above all, how can one project be converted into another?

These two studios allowed us to understand how the students designed, what procedures they carried out and what arguments they communicated. From these, we proposed a radically different work methodology for the last workshop, which put to the test what I learned in The Dictionary of Received Ideas Studio, from the moment it uses a series of precisely defined constraints -which forces the students to pose all possible actions within a defined theoretical framework, and therefore exploit its boundaries-, to orient their work directly to uncertainty, forcing them to work with arbitrary rules that prevent them from visualizing a project result, and forcing them to experimentation as the only modus operandi.

This notion assumes that every project arises from initial conditions, which are usually imposed by an external party, and can be understood in principle as constraints that prevent

the development of what is really wanted, or as opportunities that challenge these initial constraints. However, when these constraints are self-imposed, they imply a greater challenge, which is to confront oneself with something that is known, to exercise a critical action with respect to what one has designed and with this, to question how these elements are validated.

For this studio, a series of constraints to design were extracted based on projects previously developed by the students and that had been recurrently used by them -whether they were successful or not- which are compiled in an instruction book. These rules are independent of each other, they have no reason or suggestion as to how or what they should be used for, but have been expressed as simple rules, written with the precision and asceticism of a technical manual. The location of each project is assigned randomly, assumed as an additional constraint.

Each project starts with a set of constraints generated from the process described above, defining a list of 66 shared-use components. Each group of students will work with three of these constraints in the development of their final proposal.

If we think that these conditions for designing are arbitrary, facing rules built from our own projects implies facing our own arbitrariness, which made sense in a time and context different from the current one. In this sense, a project achieves success when it controls and redirects such arbitrariness in a coherent design. To build a rule, express it clearly and turn it into a useful component for other designers is to make clear and precise a

process that is not always so.

Under this logic, starting a project from pre-existing components generates a code -as a theoretical framework- to elaborate the proposals, leading the project towards an uncertain direction with respect to what is normally developed in a conventional studio, where each proposal starts “from scratch”. The use of these collective components as raw material for the studio allows each rule or combination of rules to act repeatedly as modifiers of the project, and for each iteration in which they are used, they generate a new layer of information that collaborates with the collective design knowledge of the student team.

The rules used in the studio should be understood as accelerators of the design process that force to clarify and model the diffuse knowledge with which a project usually starts, acting as tools that demarcate every action between the designer and the tectonic components, without idealizations or deviations. Secondly, they allow a confrontation with those ideas, resources, arguments,

and formulas that are known, and that need to be revised and reinterpreted if the design is to be taken beyond its initial precepts. In other words, they define a theoretical framework that consolidates what is known about architecture, but when made explicit to others, it becomes a problem, since it provides tools and resources that are only valid when they are used outside the conventions and limitations in which they were initially proposed. Without making it explicit, the main instruction of the studio is to play by the rules, to use them differently from the expectations they implied. The instruction book is used as a catalyst for invention and exploration through design, to the extent that they are used from its margins, from the fusion and encounter of rules or from the moment it invites to read ‘between the lines’ of its own regulations. Strictly speaking, the restrictions of the studio pose certainties at the same time that they create uncertainty regarding their results, and whose only possible admissible action is to design.

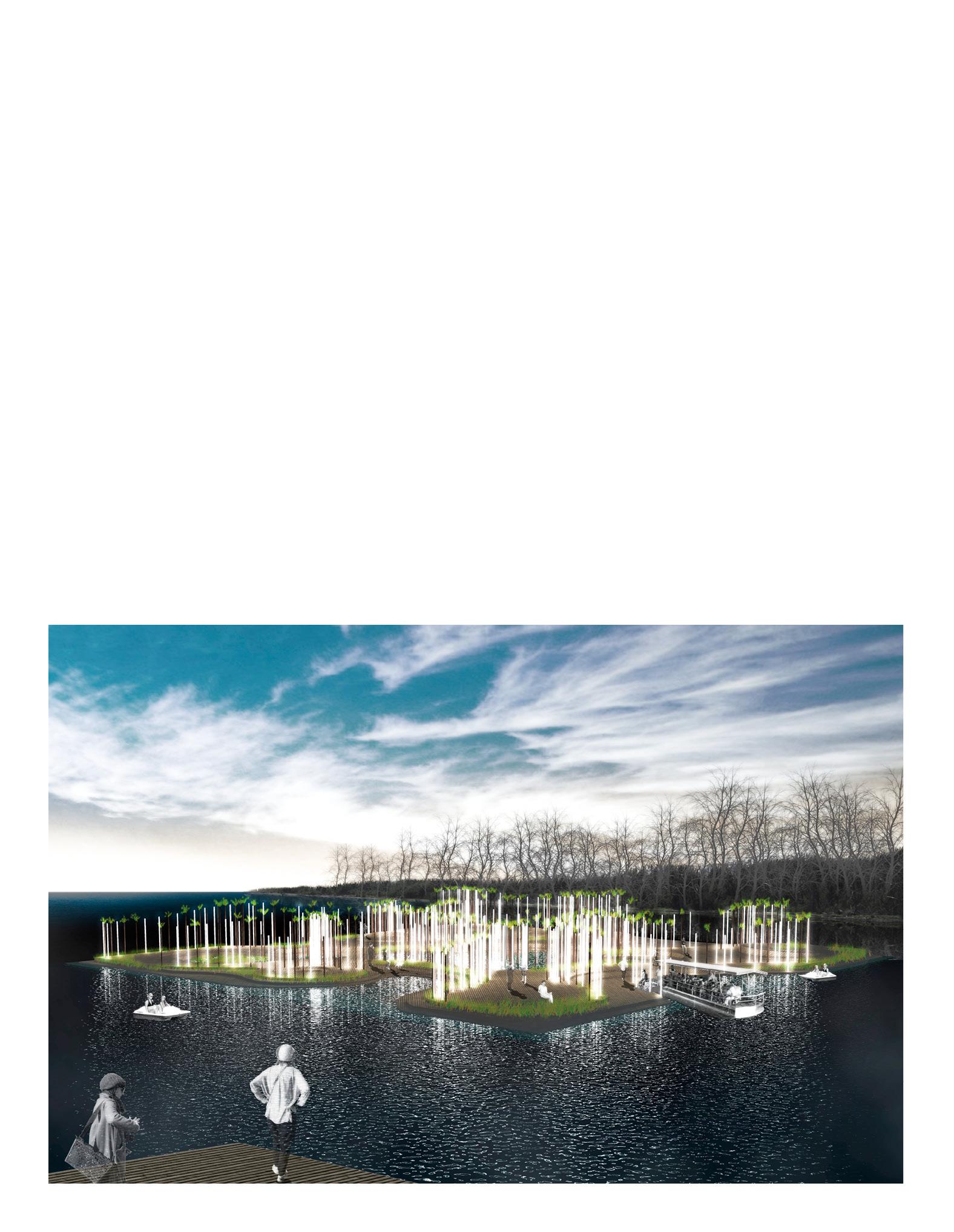

Selected project

Architectural Design Studio II

2nd Semester 2014

Riverside Plaza

3rd place Abrilar Sustentable Award 2014

Francisca Barrantes, Paula Villagrán, Diego Poblete and Gonzalo Muñoz

Selected project

Architectural Design Studio II

2nd Semester 2014

2nd place in the Abrilar Sustentable 2014 Award. Valentina Acha, Makarena Ceballos, Lenka Rubio and Iván Sanhueza.

Selected project

Architectural Design Studio II 2nd Semester 2015

Selected project

Architectural Design Studio II 2nd Semester 2015

Residence for athletes

Project ‘Proceso FAU’ for the dissemination and study of student projects

School of Architecture

Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Chile 2014-2017

www.proceso.uchilefau.cl

A common concern of all architecture students during their training is to know when a project is finished. With the exception of professional practice, which demands results built under strong limitations of time and resources, the development of projects in the academy does not have such defined boundaries. This could be explained by the fact that learning architecture is a personal process, based on speculation and constant work, which differs with each student.

This condition is clearly revealed in the product that crystallizes all design actions: the architectural project. A project is not a finished work, but an intermediate phase of a larger journey, a stage that brings together enough coherence and clarity about the work in progress to set future directions. Developing projects is a profoundly optimistic task because it capitalizes on all present work as a positive inflection. In this sense, the future will always be understood as a better state than it is now, since every good project could translate into a possible good building, or that the experience and learning obtained in the academy could cement a good professional development.

Recognizing that all the work done in the academy is a bet on the future means that nothing that is learned is finished once acquired, that no project is correct enough to remain unchanged, nor that no one has acquired optimal knowledge to be satisfied with obtaining a professional degree. This means that everything one does in these classrooms is only a part of a larger process. This can be understood from the phases of elaboration of a simple

design proposal, to the learning and improvement of the media, techniques, and knowledge that we have to make architecture. These processes describe a series of stages of different complexity and scope, always in constant progress.

The initiative of compiling and publishing portfolios (documents that synthesize the work of students) records these processes, generates a framework that allows us to observe what is planned in the architectural studios of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the U. of Chile, to study it and put it in perspective. It is a hindsight tool that allows us to see what has been done, how projects have been planned and developed, and what can be learned for the next stages. Likewise, its scale is transversal, since it sets a point of reference for each student regarding the work done; for each studio that learns from its own experiences and those of others; for the faculty as a whole that can observe itself in its complexity and completeness from its most honest architectural production and even for society, which can learn about the valuable work that our academic and student community is doing today.

This project - FAU Process - was a synthesis of the learning of the architecture students expressed in a narrative compendium of images and text, which showed how they have developed their intellectual and creative interests in the different FAU courses and studios. This instance registered all the proposals elaborated by the school -without exclusion by themes or qualifications- in a common space that highlighted the work of the entire academic community.

The FAU Portfolio Project generated a public database with all the architectural projects produced each semester, so that they can be used for publications, competitions, accreditations and faculty exhibitions. The first product of this project, the FAU Process website included all the projects received during the second semester 2014 and 2015, with more than 1130 entries it was the largest student project page in Chile.

In the last stage of this project -which was cancelled due to lack of funding-, a printed publication was being prepared, a book that would analyze from the academy the ideas, design methodologies, trends, themes, and topics of interest that can be studied from the design production of the studios each year. In this way, we sought to close a cycle that integrated the vision of the students with that of the academics, using different tools and formats. One built as a database, an instant access to detailed information on student projects, and the other as a pause for reflection and discussion that examines these projects; both built to expand the learning capacity within the academic community, generate links between its different members and produce knowledge beyond the compartments of the school’s structure.

Courses Observation of Architecture and the City, Analysis of Architecture and the City, Architectural Culture 1 and 2. 2016 - Present

Professors: Claudio Palavecino and Sebastián Cuevas (2016 - 2018 -2020) / Assistants: Andrea Fuentes (2017), Francisca Barrantes (2019), Francisca Leiva (2021- 2022) and Catalina Barra (2023present).

School of Architecture

San Sebastian University

Architecture as a discipline has adopted a series of terms through which it constructs its certainties, conventions and knowledge. Concepts such as “space”, “context” or “program” are part of the usual vocabulary of architects and academics, and although their meaning may be imprecise or ambiguous, they are functional to command and materialize the actions of architectural and urban design. If these concepts can open multiple layers of interpretation, it is largely because of the interaction and dependence of architecture -as a field of knowledge- with the observation and interpretation of a physical reality, expressed by tangible elements, pieces that are assembled, shaped or articulated giving form to our built environment.

All architectural projects and works originate from the manipulation of these components, and while the expression, technique and articulation of these components has changed throughout history, we recognize and understand them with precision. We can identify them unambiguously and, perhaps

for this reason, they are rarely approached as a subject of study, despite the fact that it is in these -walls, columns, floors, stairs, windows, roofs, corridors and rooms- where architectural knowledge is materially stored. This knowledge is everywhere, it can be easily seen, touched and recorded, and in the same way that these elements shape buildings, we can also understand elements that build our understanding of the city.

Roads, landmarks, nodes, facades, corners, edges, ground plans, levels, blocks and buildings constitute a vocabulary of urban elements that we are all familiar with. We use them constantly because they are useful to describe our contextual reality, and like the building components, they reveal multiple layers of design, conflict and dialogue of different agents, whose effects are physically expressed in the city. Many of the means and tools of urban design and planning restrict and simplify this reality, regulating ways of operating on the city, leaving aside the broad and rich knowledge that is visible in everyday experience.

Our students are experts in architecture and the city, and we offer tools to decode this reality and begin to understand it from the knowledge and discussion of architectural and urban works, their history, their arguments and possible readings or interpretations of them. In this series of introductory courses to the observation, analysis and culture of architecture and the city, we study together with our students -who are entering the university- how the different elements that make up buildings and our cities can be objects of speculation.

We analyze the theories underlying these architectural and urban elements, we visit buildings, we draw them, we measure them, we photograph them and we place them in a collective debate. Each class starts from what we know, and ends with questions that destabilize the initial precepts. What is apparently a glossary to learn to identify elements, constitutes a framework from which to deconstruct those elements and make our students aware of the reality in which they are immersed.

Student work from Observation and Analysis of Architecture and the City, and Architectural Culture 1 and 2 developed between 2017 and 2023.

to buildings and field work

Each session of the courses on Observation and Analysis of Architecture and the City, as well as Architectural Culture 1 and 2, includes work in the classroom and in the field, visiting different buildings in Santiago. Among these, the National Library, La Moneda Cultural Center, Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center, Manantiales Building, Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Portales Neighborhood Housing Unit, Anacleto Angelini Innovation Center, Tajamar Towers, Campus Oriente UC Extension Center, La Merced Building, Pereira Palace, NAVE Center, School of Arts of the University of Chile, Cuauhtémoc Park, UC Science and Technology Building, among others, have been visited.

Materia Arquitectura Journal No. 17

Studio/Office

Director: Mario Marchant / Guest editor: Claudio Palavecino / Proofreader: Renato

Bernasconi / Art direction: Kathryn Gillmore / Graphic design: Macarena Balcells / Translations: José Molina / Text editing: José Salomón

Ediciones Universidad San Sebastián 2018

As a discipline, architecture has built its cultural heritage to a great extent from concepts or ideas that may be recognised with a certain degree of precision and which are useful for knowledge building. Architecture studio and office do not form part of this conceptual matrix. Their conceptualization is elusive, embodying itself in different figures – studio, office, atelier, laboratory, workshop – that more than intending to clarify their identity, would seem to be responding to opportunist agreements, modelled by different professional and academic circumstances with the purpose of naming the generic space where architects work and are trained.

In this context, all definitions of architecture studio and office may seem rather biased if we consider that every architectural practice is different, that it pursues subjective interests and articulates its own work systems, thus singularizing its workspace starting from unique conditions. In these circumstances, architectural studio and office are understood from a useful ambiguity. We can visualize them like a ‘place’ where several actions occur, a physical space, an environment that allows architectural work to be developed. Thus, studio and office build a culture, a system of relationships between ‘agents’, whether they are people, objects, resources, data or tools, that are activated under rules and connections at the service of a common objective that could not work in isolation. Lastly, studio and office can be justified as a means of architectural ‘production’, as they pursue an objective that can be translated into objects, information, research or another form of expression.

This issue of Materia Arquitectura places the architecture studio and office as study phenomena, taking advantage of their conceptual ambiguity to escape any attempt at definition and assuming its complexities as a reflection of the constant –and necessary – reformulations of architectural practice. In order to do so, the dossier poses from three approximations from where to examine the studio and the office: the physical and virtual space that embraces them; the agents that ccompose them and their interactions; and their academic as well as professional production. ‘Place, agents, production’ build a triad in conflict and dependence, a prism where to build critical discourses on the way in which we build, experience, represent and socialize architectural knowledge and, through this, observe the space from where these actions emerge.

The paradox of studio and office is that, being omnipresent institutions in the practice and teaching of architecture, their intellectual importance is left in the background. However, “the ‘studio’ is a staple of the disciplinary tradition of architecture” – as Emmanuel Petit argues. The knowledge of architecture emerges there, giving form to a creative workspace that may be taken to other fields of knowledge. This is exemplified by coworking spaces emerging from the studio/ office model in architecture – as explained by Gonzalo Carrasco – and become known commercially as attractive spaces for creative work. This is not a superfluous matter: architectural workspaces are, themselves, ideological projects – as stated by Esteban Salcedo –, architectural objects that assume a critical

position about the professional production – even regarding a market model, as argued by José Sánchez – and may materialize in workshops, exhibition galleries or – as stated by Tamao Hashimoto – deploy intermittently and strategically in the city.

Beyond its object condition, the architectural studio and the office are represented in the interaction of their agents, either by means of the dialogue that specifies their ideas – as expressed by the text edited by Ernesto Silva and Rayna Razmilic –, unveiling the imperfections, negotiations and collaborations of project work – as shown in the conversation with Amale Andraos and Dan Wood –, or illustrated by images of the actions, accidents and malpractices occurring there – as illustrated by Michelle Fornabai in her graphic report. At present, architectural studio and office – according to Esteban de Backer – embrace the complexity and contradiction of the processes of architectural work, often being understood from a kind of ‘creative pragmatism’, beyond simple efficiency and professional productivity.

It is possible that architectural studio and office may never be captured in the pages of a publication as such, only as references, reimagined, criticized, commented upon or expressed between lines. ‘Place, agents, production’ is a phrase that expresses this, it does not have neither subject nor verb nor object, it is just a set of words that trigger an imagery between authors and readers.

Visual Arguments Course

Elective VII - VIII - IX semesters

2nd Semester 2017 and 2nd Semester 2018

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Teaching

Assistant Rafaela Olivares

School of Architecture, Diego Portales University

Visual Arguments Course

Disciplinary Elective

2nd Semester 2018

Professor Claudio Palavecino

School of Architecture, San Sebastian University

Behind every architectural project there is a design process, entailing strategies, negotiations, arguments, and constraints. We tend to accept that the media with which the project is represented are a translation of these abstract conditions, such as technical drawings, physical models or sketches that can be understood with greater or lesser precision depending on the technique of their elaboration. But as with translation in language, the codes in which a message is expressed condition and define it. Thus, the architecture we know is to a great extent the result of the representation media with which it is communicated, being an inherent part of it.

The course “Visual Arguments” assumes as its basic premise that the representation media of an architectural project define a framework for the argumentation of the project. In this way, we can understand that the technical constraints of the medium are also limitations that the architect has consciously or unconsciously defined to project, that the selection of what

to show or what to ignore in a drawing or sketch defines what is communicated, and with this, the understanding that others will perceive of a project; or that the scope of possibilities of representation is a reflection of the paradigms of a specific time and place.

“Visual Arguments” is an instance to critically study the representation media used by architects in buildings and projects as a manifestation of different disciplinary, cultural, political, technological, and intellectual paradigms, and allows students to reinterpret them based on their critical review. Questioning the representation of a project implies destabilizing its arguments and their positioning in a certain validation framework and constitutes a way of questioning our architectural culture. Can new arguments be elaborated for a project if the media through which it is represented are altered, manipulated, or replaced?

Visual Arguments student work at Diego Portales University and University San Sebastian in 2017 and 2018.

Project Publication

Elective VII - VIII - IX semesters

1st Semester 2018

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Teaching Assistants Danery Elizondo and Nicolás

Silva

School of Architecture, Diego Portales University

Visual Arguments and Portfolio

Elective VII - VIII - IX semesters

2nd Semester 2020

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Teaching Assistant Tamara Castro

School of Architecture, San Sebastian University

In the last years of his life, Andrea Palladio published “The Four Books of Architecture”, a comprehensive treatise on the art and technique of architecture. Palladio’s influence on the architecture of the following centuries is unquestionable, and an important part of this influence is due to the elaborate illustrations in this publication, which showed in exquisite detail the elements, proportions, compositional systems and design techniques used by this architect. These drawings were not simple copies of the plans and sketches that preceded the construction of his buildings, but were specially elaborated for this publication. Through this action -revisiting and redrawing his own projectsPalladio would reinterpret his own work based on the experience and culture acquired over time, and through this he would build a new knowledge that would endure and consolidate its importance for future generations.

Architects develop projects not only under the premise of their possible building, but as a manifestation of our disciplinary ideas

and concerns. These are codified in all kinds of representation media -drawings, plans, diagrams, etc.-, expressed in multiple formats, from posters, magazines, books, web pages or exhibitions. Of all of them, one is particularly important, the project portfolio or monograph, as it allows us to understand the designed object from multiple perspectives, such as its development, its influence on other works by the same architect -and its evolution over time- or to reveal actions, decisions and theories that could not be understood only with the documentation of each project in isolation. A portfolio or monograph of projects is a powerful tool to express arguments, ideas, and intellectual concerns of an architect through a retrospective study of his own design production. In the same way that Palladio did, many contemporary architects develop portfolios of their own, not as simple catalogs or compilations, but as a way of re-observing their own professional development and communicating it to others.

“Project Publication” allowed students to develop their own

architectural portfolio, synthesize and systematize their work on projects throughout their brief career and represent them in a narrative structure aimed at studying how they have represented them, revisiting the ideas and arguments addressed, and enabling the emergence of new questioning and critical stances through the publication strategies each of them adopts.

1st Semester 2020

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Teaching

Assistant Maximiliano Aldunate

Faculty of Humanities, School of Architecture, Mayor University

The architecture we inherited at the end of the 20th century assumed its metropolitan condition, and with it, its importance as a cultural production. It is no longer enough to think how a building can be harmoniously contextualized with a city, but how each building is a reproducer of the city, an expression of its habits and culture. The concerns of urban design are today also the concerns of architectural design, and their domains merge in proposals that blur the boundaries between the city and the buildings.

This conjunction takes on special relevance in the notion of public space, which has become one of the main disciplinary focuses of the last decade. In just a few years, the notion of public space has transcended the usual typological conventions of parks, promenades, and squares, becoming a field of speculation and experimentation of collective ways of life, regardless of whether these are between buildings, in open spaces, on rooftops or inside shopping malls. It is not strange that, during the last few months,

Selected project Studio VIII 1st Semester 2020

Urban Refuge

María José López and Sebastián Manríquez

the process of social unrest in Chile has been expressed in forms of occupation and domestication of different surfaces, streets, squares and other spaces in the city. In its apparent neutrality, this plane has become the scene of disputes, agreements and mediations, a repository of public life, a “plane of conflict”. These events unfold under the codification of norms of displacement, occupation or dispersion, many of them tacit and collective, which are defining new forms of spatial relationship, new metropolitan logics that have little or nothing to do with the canons of design that we architects usually work with. In this context, what can we learn from this scenario? what possibilities, opportunities and spatial configurations are present today in public space that we have not paid attention to? and how can we apply these discoveries to the project design? The studio proposes to analyze the spatial phenomena that shape the plane of conflict, to understand them and transform them into tools for project design.

We can understand that every architectural project is an expression of knowledge encoded in material components (columns, walls, roofs, etc.), and the way in which we conceptualize and operate with these components depends on cultural and technological consensus, on the transformations of the city and architects. In this sense, the studio is conceived as a design laboratory that translates the codes of public space into design rules, precise material operations, and through this seeks to question existing canons and propose new dialogues between the building and a city in transformation.

Studio V: The Place of Conflict: Conflicts at Home 1st Semester 2021

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Assistant Viviana Urra Faculty of Humanities, School of Architecture, Mayor University

Studio VI: The Home, a Material Microcosm 2nd Semester 2021

Professor Claudio Palavecino; Teaching Assistant Dannery Elizondo Faculty of Humanities, School of Architecture, Mayor University

Many have written about an “end of cycle”, an epochal turning point that - as a result of the exhaustion of political and economic models, the rise of new groups and social paradigms and the need to rethink our way of life in the face of an unstoppable ecological crisis - defines a frontier between a past that we wish to leave behind and a future that is totally uncertain. We do not know how the accelerated transformations of recent times will shape this new life scenario. However, observing and reflecting on how we have lived up to now - how that life manifests itself in our material reality - gives us some clarity as to what is ending and what is emerging. Few scenarios allow us to visualize this transition as pristinely as our own homes.

Our houses and apartments embody in their surfaces, forms, and structures a material knowledge that reveals the disciplinary, cultural, ideological, and power paradigms with which the most intimate aspects of our lives have been shaped. The architecture of our homes is the product and producer of habits, personal relationships, family life, protection, and stability. It is the environment in which we grow up, the one we know best and the one we most freely customize.

In recent times, the health emergency resulting from the global pandemic has transformed our homes into the main stage, if not the only one in which we develop our daily lives. If the public space had been the scene of conflict and emergency, the pandemic suddenly forced us to retreat into our domestic shelters. Many of the phenomena that had been expressed in the public space were

The place of conflict: conflicts in the home

During the first stage of the studio, the students graphically synthesized the activities, displacements and spaces within the home, and from this information, generated a repository of architectural operations to rethink the domestic space.

transferred to our homes, accelerating and intensifying changes that had already begun to be outlined and implemented in recent decades, such as teleworking, delivery services or the flexible use of rooms within the home.

Architecture studios V and VI addressed the architecture of our homes as a study phenomenon, not only to understand its importance during the pandemic period, but also to observe how it can provide us with perspectives on the near future. The first of this series - “The place of conflict: the conflicts of the home”proposed to observe the homes in which we live and learn from the adaptations and transformations they experienced during the health emergency period, in order to rethink the current housing typologies. For this, the studio positioned the home as a catalyst of social life, work, and consumption habits.

As rarely in history, our domestic life absorbed the complexities of our reality, its conflicts and tensions, all taking place in the privacy of our homes. The architecture of our domestic spaces, their size, organization, privacy, aesthetics, activities, materiality, and functioning were challenged. Beyond the usual typological formulas of our discipline, or the conditions imposed by the housing market, we had to ask ourselves if we like our homes, if their architecture is representative of our needs and desires; and even more if it would make sense to replicate the architecture we know of these places in a scenario of uncertainty like the one we were living in.

To answer these questions, the students collected their own

domestic experiences in pandemic and systematized them in maps and diagrams. This documentation was the basis for a repository of design, tectonic and programmatic formulas with which to propose new domestic architecture proposals. These would seek to redefine the housing tower, exploring the usual programmatic schemes, the community connections they host, the productive logics and their ubiquity in these, the possibility of generating adaptable rooms, the common spaces and the dialogues between home, public space, and urban environments.

The learning from this studio would be deepened in a subsequent research studio, called “Home: a material microcosm”. This sought to visualize and examine the material processes that have taken place in our homes over the last thirty years. This historical lapse frames the period of the rise of the liberal model around the world, which today is in a visible decadence. In Chile and in much of the world, this period is defined by the return to democracy, the consolidation of an urban life and culture, the accelerated development of digital and communication technologies, a massive increase in access to consumer goods, the commodification of labor, and the decline and crisis of the institutions and ideologies that had shaped an era that, in Fukuyama’s words, was “the end of history”.

Despite the sheer breadth and depth of these transformations, the studio’s hypothesis aimed to understand how the material elements that make up our homes constitute a microcosm homologous to our global cities and networks. In the small scale of

Selected project Studio V 1st Semester 2021

The Network Fabiana Labraña, Jesús Santibáñez and Tomás Ahumada

Selected project Studio V 1st Semester 2021

Triangle Module

our homes, in their measurable and verifiable architecture, what is happening in our country and in the world takes shape. Under this approach, decoding the architecture of our homes is a means to understand what is happening beyond it.

The methodology of the studio consisted of examining domestic architecture through graphic and textual documentation; the selection of study subjects -built objects, routines, places, surfaces, and domestic landscapes-, their relationships and networks; and the production of narratives that crystallize domestic processes and transformations in actual buildings. A special emphasis was placed on observing the possible interpretations and transmaterial networks between the home and public spaces, since the latter plays a key role in the domestic confinement of recent years. All the production of the studio was synthesized in publishable documents or thematic dossiers.

The home, a material microcosm During the first stage of the studio, the students made a timeline of important events of the last thirty years. Then, a study of domestic spaces, based on their objects, routines, agents, places and images. And finally, a mapping of transmaterial networks that allow us to see the communications, connections and transferences between the home and its context.

Selected research dossiers

Studio VI

2nd Semester 2021

Dependence on the dark

Sofía Godoy, Sofía Gallardo and José Guzmán

Interior walls

Fernanda Aguilera, Fernanda Delgado and Matías Novoa

The intruder (or the omnipresence of the mobile phone)

Noelia Anza, Paloma Morgado and Rocío Méndez.

Graduation Project Studio (Diploma) 2021-2022

Professor Claudio Palavecino

School of Architecture, San Sebastian University

Throughout history, we have seen how the emergence of new technologies has changed our routines and lifestyles. We are currently living in a time in which information and communication technologies, the global mobility of capital and the automation of production processes are establishing what some experts call a fourth industrial revolution. Many of these transformations impact directly on labor logics and dynamics. In recent years we have observed an increase in the precariousness of jobs, a questioning of long working hours, the rise of teleworking, the need to create spaces for collaborative work, the promotion of policies of inclusiveness in different employment areas, and a strong emphasis on specialization and professionalization. If we understand that these realities -and other emerging onesare changing the meaning of work as we know it, how does architecture respond to these transformations?

The evolution of architecture for work, from an industrial society to a knowledge society, is reflected in the shape of cities, in the

generation of new neighborhoods or in the emergence of new typologies of industrial buildings. Perhaps, where we can notice this evolution more clearly is in the office typology. From work capsules, to the organization of free-floors plans; or in the efforts to make the co-working space a sort of extension of the home, the office expresses through architecture our cultural, political and technological relationship with work.

The architecture graduation studio “Workspace” proposes to reflect on how the design of the spaces where we work reproduces the problems of contemporary society, and how this same instrument -architectural design- can transform our human and material built environment. In this sense, the studio formulated four foundational questions on this topic: How can we design desirable work environments that respond to the needs, desires, cultures and sensibilities of those who work there?, How can the architecture of these places provoke and give value to collaborative work, proposing new productive scenarios beyond

typological conventions?, How does the proposed architecture critically and sensitively reflect current technological changes?, How do they propose new aesthetics and new work landscapes? and How does the architectural proposal contribute to the built environment, how does it dialogue with neighborhoods, landscapes, streets and networks of our cities?

From these bases, each student established a diagnosis of the cultural, technological and political conditions of the workspace they wished to explore - repository of ideas - and the architectural tools - repository of operations - with which to materialize these intentions. These were the bases with which they then developed their architectural graduation projects.

Architecture Studio 1 and 2 2023

Professors Tomás García de la Huerta and Claudio Palavecino

Finalist Iberoamerican Biennial of Architecture 2024 - Category Pedagogies (with the collaboration of Benjamín González)

School of Architecture, San Sebastian University

What is an architectural project? If we think for a moment about the concept of “ project”, it refers to synthesizing the desires and needs of those who design through different representation media -drawings and models- that anticipate a possible building. Under this logic, the object we commonly call ‘building’ is the expected result of a series of coherences embodied in a plan, an image or a previously elaborated scale model. This process assumes (or yearns for) a total control of matter and the ways of operating with it, a power conceived from a discipline alienated from natural cycles and which, to a great extent, has been one of the causes of the current climate crisis.

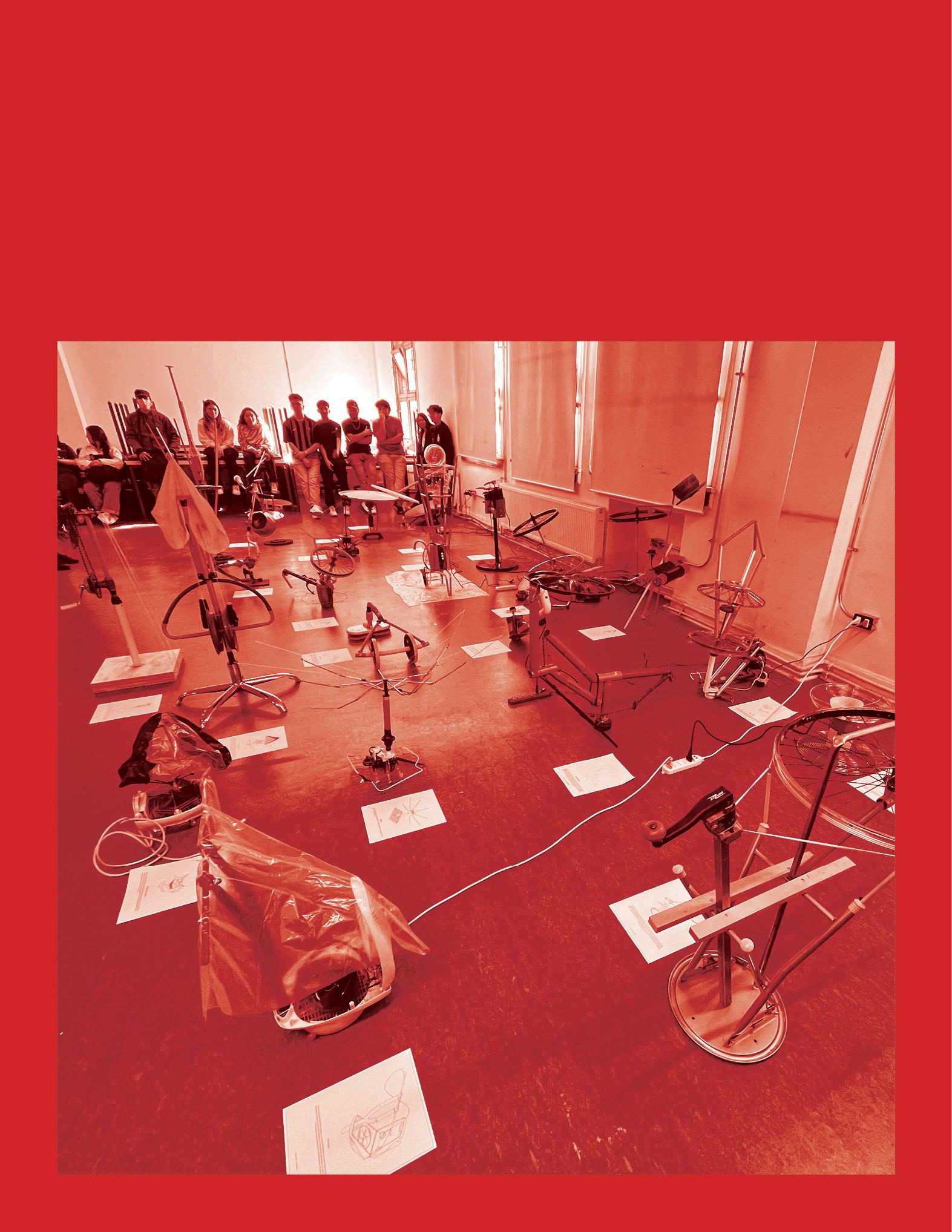

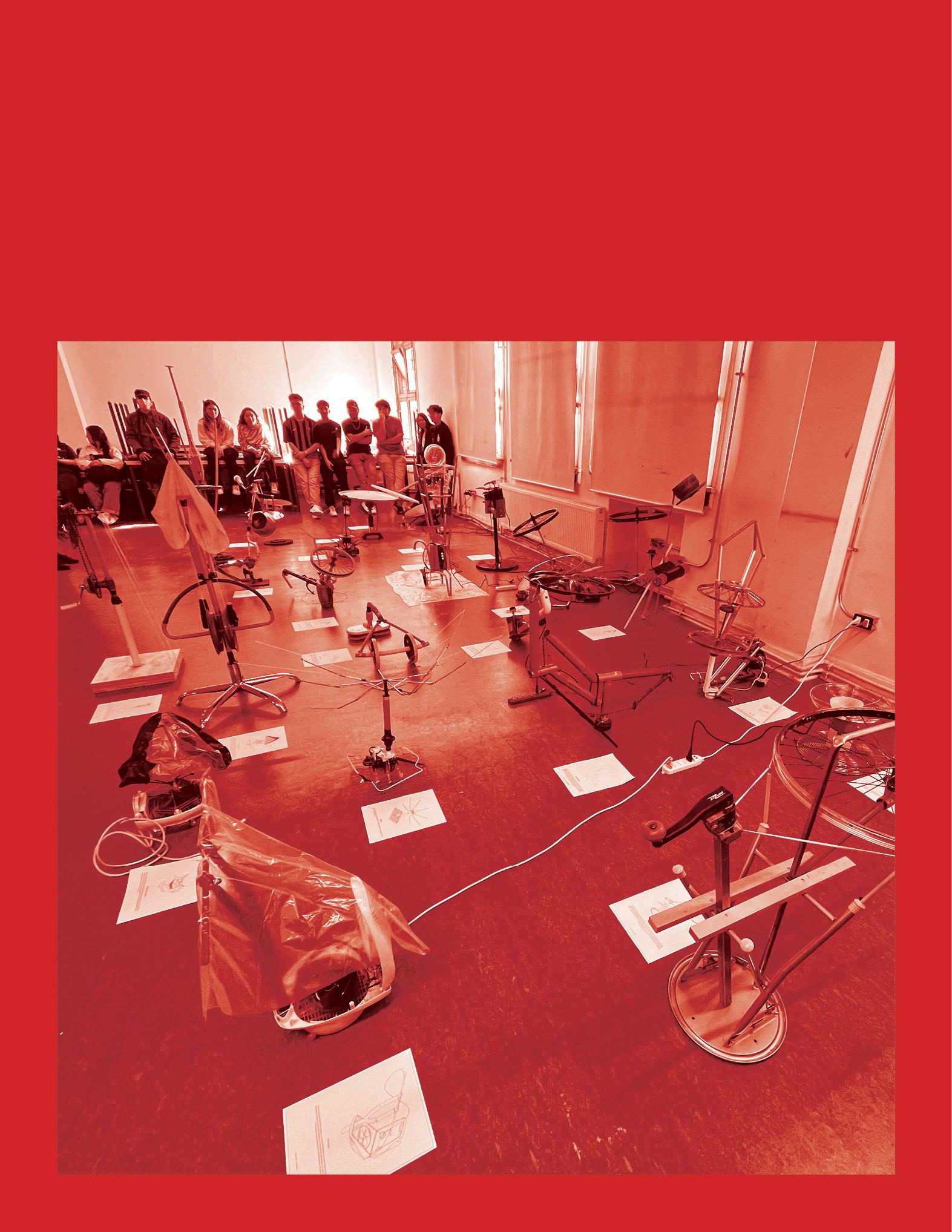

The Material Ecologies Studio does not intend to project from that control, but rather to invert the relationship of power that we have over this material world. That is to say, to reveal the intrinsic value of the objects, artifacts and pieces that compose it, and to integrate this knowledge in a design logic circumscribed to the ecological complexities of our environment, to the needs of human beings and the vital dynamics of other living beings.

To this end, we propose the development of “environmental stimulators”, objects conceived from the intellectual and technical consistency of architectural design and that, from their plastic, formal and functional setting, can transform the environmental conditions of their surroundings. This process arises from a plan articulated by the following stages:

- Collection: we define an inventory of objects that are valueless from the usual perspective of our discipline -broken or discarded

Collages of material hybrids made by the students of the Material Ecologies Studio (2023)

artifacts, waste- but that contain a material value to be explored. These will form a basic repository from which all the subsequent design work will be based.

- Model: These objects constituted the pieces of a hybrid, an assembly that allowed us to experiment with new spatialities and expressions materialized from the physical exploration -unions, counterweights, deformations, tensions, compressions- generated by and between the parts of this body. These hybrids, could execute movements, deployments, rotations or perform other action that physically alter or modify their environment.

- Translation: The models were translated into collages and technical drawings that, on the one hand, allowed to adjust and correct unions, scales, modulations and articulations of pieces of this material hybrid, and give it coherence as a unified body; and on the other hand, allowed to integrate progressively, the environmental factors with which this object had to dialogue. That is to say, it was a stage in which the architectural design was the result of the drawing, insofar as this interpreted a tangible reality and allowed to disclose its material logics.

- Context: We explore the connections, relationships and tensions between these objects - understood as material and graphic hybrids - with the existing environmental conditions, and seek to enhance and intensify them, in order to generate instances of interaction and coexistence between human beings and different organisms. In this sense, it is worth pointing out that the first version of the studio worked with generic environmental contexts,

while the most recent one integrated these hybrids as part of the structure of an existing building.

- Product: From the process, its interpretations, mediations and discoveries, new architectural objects emerged, which could not be understood as finished projects, but as constructions in dialogue with their environment, which we call ‘environmental stimulators’.

The studio never sought to impose a commission, nor to propose solutions to specific problems, nor to have predefined images of what architecture should be generated, nor did it even have the ambition to design buildings or come close to solving them. We propose the studio as a laboratory driven by a method of work and exploration oriented to think and make architecture from an ecological paradigm, in symmetry with the material reality that surrounds us.

Planimetric and axonometric drawings of hybrids made by students of the Material Ecology

Selected Projects

Architecture Design Studio I 1st Semester 2023

Selected Projects

Architecture Design Studio II 2nd Semester 2023

Environmental Filter

Javiera Chicaguala

City and Territory 3 and 4: Theory of Architecture 2024

Professor Claudio Palavecino

School of Architecture, San Sebastian University

In the late eighties, it was theorized that Western liberal democracies would lay the foundations for unparalleled prosperity and stability for human beings. This thesis, which claimed a supposed “end of history”, has proven to be a biased and erroneous premonition, when judged from the perspective of our present. The climate crisis has jeopardized the future of our life on the planet, disturbing ecosystems and impacting thousands of human and non-human species. Information and communication technologies have had far reaching social and political effects, changing the way we work, socialize and exert democracy. China has become the world’s largest industrial power, ethnic and gender groups that were once marginalized are acquiring a new place in society, and dangers that we would have considered extinct, such as the one caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, have revealed the fragility of our life models.

The 21st century seems to be an era marked by uncertainty, rather than by the consolidation of a great project of development and

Exhibition of essays developed in the course City and Territory 3 - Theory of Architecture. 1st Semester 2024

Exhibition of essays developed in the course City and Territory 4 - Theory of Architecture. 2nd Semester 2024

stability. In this scenario, what is the state of architecture? What ideas, theories, actions and processes have sustained it in recent years?

Through this series of classes, I seek to build a framework for questioning the material and intellectual production of architecture over the last thirty years on both the national and international spectrum. This approach deliberately evades disciplinary certainties and instead raises questions on how architecture operates in the world, and how the world redefines what we understand for architecture.

To this end, we begin by addressing the crisis of discipline autonomy in the late 1980s and the diverse approaches to the architectural project from the 1990s onwards. We inquire into the role of digitalization in design processes and aesthetics, the effects of the global metropolis on architectural production, and the fragmentation of interests and practices during this period.

We also speculate on the emergence of theories, aesthetics, discourses and narratives from the dialogue between the world of information, the world of things and the world of living beings, examining cases that question and propose new architectures from ecological thinking and cosmopolitics.

Through these ideas, we also analyze the constructions and deconstructions of architectural production in Chile, exploring its key figures, the changes in their positioning regarding their work, from the isolated object to the interest in the city and public space, examining the myths and biases that have built their image abroad and within our society.

Archipelago City

Organized by: Loreto Lyon and Claudio Palavecino.

Graphic design: Cristina Núñez

School of Architecture, San Sebastian U. 2022

Urgent City: How do we want to live?

Organized by: Loreto Lyon and Claudio Palavecino.

Graphic design: Cristina Núñez

School of Architecture, San Sebastian U. 2023

Future City: Overlapping Experiences

Organized by: Loreto Lyon, Claudio Palavecino and Diego González.

Graphic design: Cristina Núñez

School of Architecture, San Sebastian U. 2024

The Architectural Culture Conference Series at the School of Architecture of the San Sebastian University have brought together some of the most distinguished scholars, professionals and intellectuals of our country around projects, ideas and buildings that allow us to discuss contemporary architecture and the city. In recent years, this interest has been focused on the city, understood as the stage and generator of material realities, cultural expressions, landscapes, dynamics and conflicts that are central to current architectural practice and thought. My role, in charge of directing the 2022, 2023 and 2024 series, has focused on deepening this dialogue, with the participation of the following lecturers:

Archipelago City (2022):Loreto Lyon, Alejandro Beals, Paula Livingstone, Alejandra Bosch, Arturo Lyon, Danilo Martic, Cecilia Puga, Carolina Portugueis, Martín Labbé, Cristián Undurraga, Juan Ignacio Cerda, Diego Torres and Fernando Pérez.

Urgent City - How do we want to live? (2023): Joan MacDonald, Marina Otero Verzier, Sonia Montecino, Paola Jirón, Sara Ortiz Escalante, Marta Moreira and Sebastián Cuevas.

Future City - Overlapping Experiences: Germán Hidalgo, Valentina Rozas-Krause, Loreto Figueroa, Sebastián Baraona, Sofía Montealegre, Javier Pinto, Eduardo Martínez, Gabriela Etchegaray, Jorge Ambrosi, Pía Montealegre, Teodoro Fernández and Enrique Walker

Architectural projects are the result of a series of intelligently connected operations, actions and narratives. The concept of “strategy” is often used as an expression to synthesize these operational frameworks; as a way of assimilating the architect to an operator who commands troops, who knows how to control resources or who presides over a territory. Despite this, we do not have a clear notion of what an architectural strategy is, even though we assume that it is fundamental to the development process of any project. As a result of this, we reviewed multiple experiences -design, publication, work with institutions, installations- to observe how the idea of architectural strategy is as contextual and undefinable as the situations in which it must have been proposed.

Conference “Strategies: Ambiguities” Architectural Culture Conference Series School of Architecture, San Sebastian University 2017

Conference “Rules: Definitions” Workshop “Archetypal Landscapes: 1 Program, 12 Variations”. School of Architecture, San Sebastian University 2017

Conference “Architects do not make buildings” Workshop “All in line”. School of Architecture, San Sebastian University 2018

Conference “Between the studio and the office”

Seminar “Research and Architectural Problems Leading to Projects” School of Architecture, Mayor University 2019

Conference “The City of Delights” WAUM 2020 Workshop - Urban Artifacts: Mending the City School of Architecture, Mayor University 2020

All projects follow rules, whether external, such as legal frameworks or building standards, or self-imposed, such as tools, representation media or working methods. It could be considered that these rules are a way of restricting design possibilities and freedoms, but at the same time they are a way of pushing those apparent limitations to unknown frontiers. This fundamental idea is what makes the rules -as clearly defined, precise operations, with no room for further interpretationsbecome an instrument for creativity. A form of experimentation starting from simple and known design options, which conceives the project as a discovery, as something that could not be anticipated mechanically, that is to say, as an expression of new knowledge.

What is research in architecture, what parameters do we have to discern what is and what is not research, and can an architectural project be a form of research? It is paradoxical that the architectural academic milieu has embraced research as the form, the means, and the goal through which to validate its work, without questioning what it is really about. We accept that the architectural project, design methods and those who develop them cannot always be equated with the established figures of the researcher, the laboratory or testing ground, much less with the orthodoxy of the scientific method. There is no intention to explain what architectural research is, or should be, but to make visible where it takes place -in the studio and the architectural office-, and we propose these environments as objects of analysis to unveil their fundamental importance in the generation of architectural knowledge.

Can a project explain itself? It seems that this idea has become a sort of maxim for architects, but how true is this? In this conference, we discuss how the representation media are supported by a framework of culture, ideas and intentions that are not necessarily instrumental to the materialization of a work. In that sense, drawings, models or images operate as disseminators of knowledge, they inherit the existing architectural culture and reproduce it for future generations, generating questions and arguments through the techniques and media in which they are expressed.

Food does not seem to be a matter of interest for architecture. However, the relationship we have as a global community with food is mediated by the way we understand the land: as an exploitable resource. Supermarkets, restaurants or fridges are forms of architecture that crystallize such exploitation by allowing us to have easy access to food, but in doing so, they separate us further from the landscapes from which they are obtained. The city and architecture, as executors of an agrilogistic project, make the soils, cycles and processes of food extraction and production invisible. In this new context, we discuss how we can reverse this paradigm and rethink design within an ecosystemic approach.

Claudio Palavecino

Llanos

Selection of academic activities 2014-2024

Cover: Exhibition of projects from the Material Ecologies Studio. School of Architecture, San Sebastian University (2023)