HISTORY

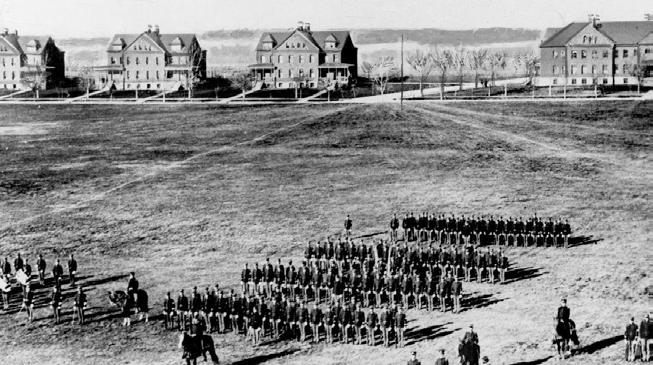

Offutt Air Force Base has a long history as a military installation dating back to its conception as Fort Crook in 1890. Offutt Field (renamed in 1924) played an important role as an airfield during World War Two. The Martin Bomber Plant, one of four military manufacturing plants located in Nebraska during the War, also operated at Offutt. The plant is most remembered for being the construction site of the Enola Gay and Bockscar, the planes that dropped the atomic bombs over Japan (“Arsenal for Democracy,” n.d.). In 1948, Offutt again gained national prominence when Strategic Air Command (later to become USSTRATCOM) moved its headquarters to the base (“History of Offutt Air Force Base,” n.d.).

Throughout its history, Offutt Air Force Base has played a critical role in supporting the Strategic operations that occur there. Since STRATCOM is critical to keeping the United States competitive on the global stage, continuous improvements to its strategies and technology are critical to ensure they are operating with maximum efficiency. With these come improvements to the built environment of its headquarters at Offutt. Even secondary buildings at the base are critical to properly supporting the work of Strategic Command.

When major changes or growth occurred within STRATCOM, construction across Offutt AFB quickly followed to accommodate the growth that was expected across the base. First, this would occur for facilities directly used or impacted by the work of Strategic Command. Following this, updates to secondary facilities such as housing, shopping, and recreation would occur to support the shifting functions and population. This cycle of STRATCOM’s impact on the architecture of Offutt can be seen repeating several times over the course of the Command.

Pre-1940s

New Construction

Renovation/Reuse

1980s-90s

1940s

2000s

Ground (1894)

and Administration (1894) Officers Row (1894-96) Officers Housing (1894-96) Commander’s Home (1894-96)

Runway (1921) Hangers (1921)

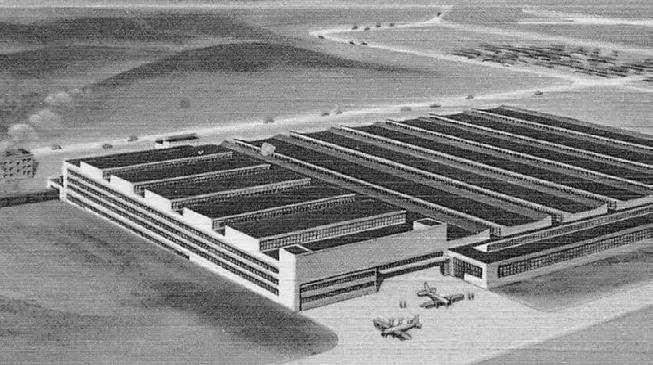

Martin Company Bomber Plant (1941)

“A” Building (1941)

“B” Building (1941)

Paved Runways (1941) Destroyed in fire (1946)

Kisling Hall (Barracks) Turner Hall (Barracks)

Dining Hall (1990s) Airschool (1980s)

(1989)

2000s

Dining Hall

Fire House (2006)

Daycare (2010)

Tuskeegee Hall (Barracks) (2005)

Kenney Gate

Housing Updates (2010)

557th Weather Wing (2008)

2010s

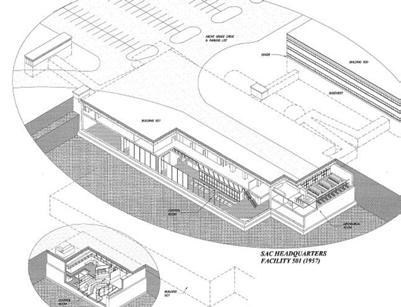

500 Building (1957)

1960s-70s

2020s

Demolished 2012

Area

Demolished 2015 Buildings demolished after flood damages

SAC Memorial Chapel (1956)

Family Housing (late 1950s-60s)

Family Housing (late 1950s-60s)

Becomes SAC headquarters (1948)

McCoy Hall (1952)

Hotels

1960s and 70s

Commissary

Exchange

(1966)

(1977)

Whiteman Hall

2020s

New Runway (2022)

Dining Hall Renovations (2025)

55th Wing Security Forces Squadron Campus (2024)

STRAT Gate (2012)

Cobb Hall (Barracks) (2019) Kenney Gate rennovations (2015)

STRATCOM Command and Control Center (2019)

Becomes 55th Wing Headquarters (2019)

Renovations (2014) Renovations (2013)

STRATCOM HEADQUARTERS

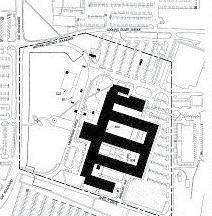

FIGURE-GROUND

AC Vents

Visitor’s Center and Underground Access Control

Entrance

Entrance

Offutt AFB Boundary

1” = 250’

“USSTRATCOM combines the synergy of the U.S. legacy nuclear command and control mission with responsibility for global strike operations.”

- U.S. Strategic Command Website (“About USSTRATCOM,” n.d.)

U.S. Strategic Command is the leader of the United States’ strategic efforts. They form a unified command and control center for overseeing both the country’s nuclear forces and global strike operations. Together, this means that Strategic Command has both the tools to detect and deter threats to the U.S. and its allies, as well as deliver a swift and decisive response in the event of an attack. As one of the Department of Defense’s eleven Unified Combatant Commands, they transcend one branch of the military to report directly to the Secretary of Defense and the U.S. president. Their goal is to provide this leadership and other commands accurate and timely information to respond to threats around the globe and ensure the safety of the nation (“About USSTRATCOM,” n.d.)

STRATCOM is responsible for strategic deterrence and nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) concerning all parts of the nuclear triad (land, air, and sea-based weapons). They also have jurisdiction over global missile defense; global command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR); electromagnetic spectrum operations; and more (“About USSTRATCOM,” n.d.).

SAC TIMELINE

This graphical timeline covers the first fifty years of STRATCOM’s history, during its time as Strategic Air Command. Notable world events, architecture, people, and SAC events are sorted vertically to understand the connections between these occurrences over time.

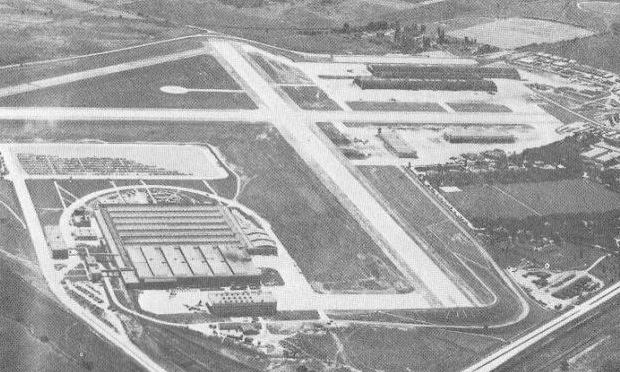

1940: Martin Bomber Plant is constructed at Offutt Airfield, along with new runway and hangars

1950: Korean War begins

1947: Cold War begins

1953: Korean War ends

1948: SAC moves to Offutt AFB

SAC moves into “A Building”, previously used by Glenn Martin Co

1946: George Kenney becomes the first commander of SAC

1944: Continental Air Forces, a predecessor to SAC, is created

1948: Curtis LeMay becomes commander of SAC

1946: Strategic Air Command (SAC) established

1965: US involvement

1962: Cuban Missile Crisis

Area and Missile sites constructed for air defense of the base

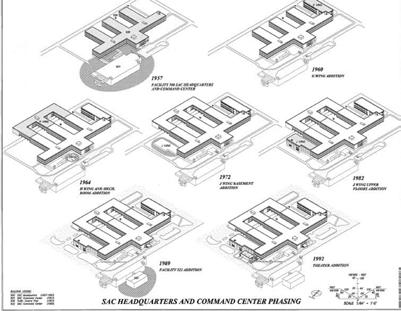

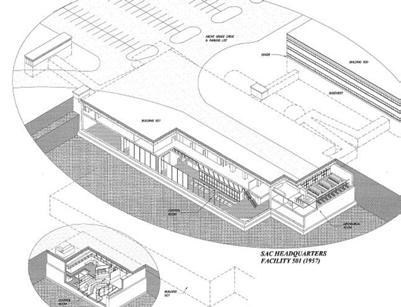

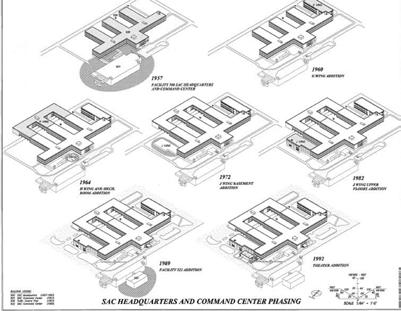

1957: SAC moves into newly constructed 500 Building

1953: President Eisenhower enacts his “New Look”

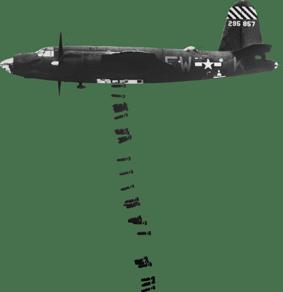

1950: SAC deploys 20 nuclear-capable bombers to Guam and 3 B-29 bombers to Korea

1953: SAC takes command of all 3 legs of the US Nuclear Triad

1951-53: SAC drops over 167,000 tons of bombs on Soviet targets during war

1960 and 64: Additions made to the 500 Building

1960: One third of all SAC bombers are on 24-hour high alert

1957: SAC deploys aircraft to Germany to run reconnaissance over Soviet Union

1950s-60s: New dormitories over 2,000 family housing units constructed at

1960s: SAC hits its peak with 3200 aircraft and 280,000 people

1961: “Operation Looking Glass”, SAC’s 24/7 airborne command post, is launched

1965: The first wave of 30 SAC bombers deployed to Guam for Vietnam War

1991: Cold War ends

and

New commissary, base exchange, hospital, and library constructed at Offutt

Additions made to the 500 Building

1973: SAC forced to downsize and close several bases

1959, 1962, 1970: Additions made to the 500 Building

1973: The National Emergency Airborne Command Post comes under SAC control

1972-73: SAC conducts Saturation Bombing missions over Vietnam

1979: SAC takes control of ballistic missile warning systems and Space Surveillance Network facilities

1989: Berlin Wall falls

Persian Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm)

1989: New SAC underground complex completed

1986: Goldwater-Nichols Act leads to single command for all the US’s nuclear weapons

1988: Process of SAC reorganization begins

1989: SAC’s first Stealth Bomber makes its first flight

1992: George Butler becomes last commander of SAC and first commander of STRATCOM

1991: SAC’s forces taken off 24-hour alert

1990: SAC runs bombing and reconnaissance over Iraq

1992: SAC is disestablished and USSTRATCOM is created

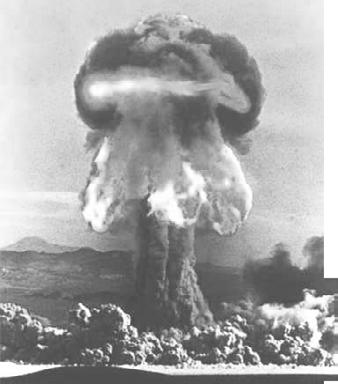

SAC CREATED: Strategic Air Command was established in March 1946 and served one of the three major commands of the US Army Air Forces (“Strategic Air Command” 2023). During World War II, the Army Air Forces ran their first strategic bombing and air defense missions. This established the importance of having strong air power and led to the need to create a unified command for strategic air operations after the War (“Strategic Air Command,” n.d.).

PEAK IN 1960S: The Cold War was a period of unparalleled growth for SAC and helped establish it as a crucial part of the U.S. Military’s forces (“Strategic Air Command” 2024). SAC would hit its peak strength of over 3000 aircraft in 1959 and over 280,000 people in 1962 (Correll 2013).

Architectural Impact: SAC’s growth in size and prominence during the Cold War established them as an invaluable part of the U.S. Military. Their standing in the public eye also became influential, as they were popularized for their role in Cold War deterrence as well as the portrayal of that role in popular media. This would influence the built environment, as architecture became an important tool for keeping up SAC’s public image (Pike 2000).

OPERATION LOOKING GLASS: This twenty-four/seven airborne command post was named after its ability to “mirror” the operations of SAC’s Underground Command Center at Offutt. Operation Looking Glass could command ground-based nuclear forces from the air in the event that the SAC’s ground-based command was rendered inoperable (“Operation Looking Glass” 2023). Operation Looking Glass began in 1961 with five aircraft, which remained constantly airborne for twenty-nine years, until they were taken off airborne alert but remained on continuous ground alert (“Airborne Launch Control Center - Operation Looking Glass,” n.d.).

KOREAN WAR: The Korean War was the first test of Strategic Air Command’s combat abilities. Immediately upon the start of the conflict in 1950, SAC deployed their forces to air bases in Japan and Guam. Reconnaissance aircraft began running missions which passed information to SAC’s bomber squadrons. On June 28, 1950, three days after the start of the war, SAC struck their first enemy targets - marking their first use of combat power. By August, SAC had five bomber groups stationed in Japan, under the command of the Far East Air Forces. These squadrons continued to run bombing missions on North Korean bridges, ports, industrial plants, and other strategic targets. They also provided close air support for U.S. ground troops and conducted saturation bombing of target areas (“The Korean War,” n.d.). (“Strategic Air Command” 2024). Missions continued until just before the official cease-fire was signed in 1953.

VIETNAM WAR:Throughout the Vietnam War, SAC continued running primarily bombing missions over North Vietnamese targets. Initially, General LeMay’s (now serving as Air Force Chief of Staff) proposal for a strategic bombing campaign over North Vietnam was rejected. However, in 1972, SAC was authorized to bomb the North Vietnam capital for the first time. SAC began “Operation Linebacker II,” a bombing campaign over key North Vietnam targets, that lasted through the end of the war (“Strategic Air Command” 2024).

PERSIAN GULF WAR (OPERATION DESERT STORM): In 1990, the Persian Gulf War campaign launched in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. SAC flew reconnaissance and bombing missions over Iraq from nearby bases in Europe and the Middle East throughout the conflict. Following the end of the Gulf War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, ending the Cold War, SAC’s forces were taken off their twenty-fourhour alert. SAC reorganization, which had been in the works as early as 1988, accelerated (“Strategic Air Command” 2024).

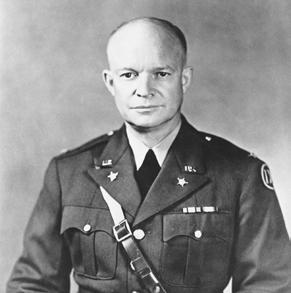

GENERAL GEORGE KENNEY: George C. Kenney became the first commander of Strategic Air Command upon its conception. During his time as commander, Kenney had several other obligations and mainly left command of SAC in the hands of his deputy commander, Clements McMullen. Kenney was criticized for many of his decisions and politics during his time in command. Meanwhile, McMullen mandated postwar budget cuts to the command, and by 1947 only two of SAC’s eleven aircraft groups were combat ready. As a result of both commanders’ neglect and decisions, SAC was suffering (Hughes 2011) (“George Kenney” 2024).

GENERAL CURTIS LE MAY: General LeMay was an Air Force General in the Pacific theater during World War Two. He was well known for his strategic bombing missions and is also credited with the organization and success of the Berlin Airlift (“Curtis LeMay” 2022). The SAC that LeMay inherited in 1948 was extremely underfunded, disorganized, and undertrained. Immediately, LeMay began implementing rigorous training and testing exercises, drilling his crews to be both quick and accurate. Having already developed a reputation as a relentless military leader during World War Two, he brought this same intensity to his command of SAC. Under LeMay, Strategic Air Command was shaped into an efficient, modern, and combat-ready force (Corell 2013)(“Curtis LeMay” 2022)(“Curtis LeMay” 2024).

Architectural Impact: Lemay had a direct impact on the development of Offutt AFB and its architecture. Firstly, he relocated the headquarters of SAC to Offutt, which would directly lead to the growth of the base and the architecture needed to support SAC’s operation there. He also promoted the importance of improved living conditions for his soldiers. This would lead to new dorms and family housing units being built on the base and establish the importance of other facilities at Offutt to support the work and people of Strategic Command (Correll 2013).

PRESIDENT DWIGHT EISENHOWER: President Eisenhower, who served from 1953 to 1961, also played a critical role in advancing the work of SAC. He introduced the “New Look’’ at national defense that emphasized reliance on nuclear weapons and investment in air powerboth of which meant investment in Strategic Air Command (Bauer 2019). Combined with the vigor and readiness that LeMay had infused into SAC in the years prior, an increase in aircraft and other tools took the command to a new level of power (“1953 - The Emergence of the Strategic Air Command,” n.d.).

Architectural Impact: Eisenhower’s “New Look” would turn the country towards a greater reliance on strategic deterrence, which meant funding and otherwise supporting the work of SAC (“1953 - The Emergence of the Strategic Air Command,” n.d.). This investment in aircraft and other tools for SAC would also include investment in their facilities, specifically the construction of a new headquarters in 1957 (Pike 2000). At the same time, the New Look was about reducing defense costs while still getting the most protection out of the country’s investments (Bauer 2019). This balance can be seen in the architecture of the 500 Building, whose construction is simple and efficient, with little ornamentation or other unnecessary features. More of an investment was made into the interior features and technology that made the command center cutting-edge for its time (Pike). For the same reason that the New Look invested in strategic deterrence, the 500 Building was about getting the most protection for a moderate cost, which led to it needing to be extremely efficient in its architectural style.

GENERAL GEORGE LEE BUTLER: General Butler assumed command of SAC in 1991 as well as directorship of the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff, a combined Navy and Air Force command that had overseen the use of nuclear forces during wartime. These two commands combined in 1992 to form United States Strategic Command, marking the end of Strategic Air Command (“History,” n.d.). Butler oversaw the transition into United States Strategic Command during his second year in leadership. After he left STRATCOM, Butler became an outspoken advocate for nuclear disarmament, in fact calling for the total abolition of nuclear weapons (“George Lee Butler” 2022).

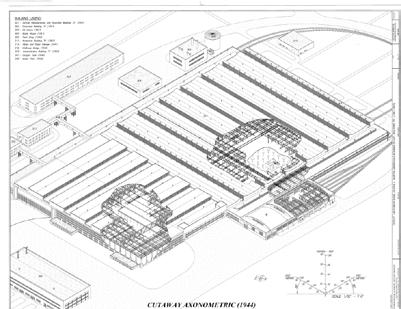

Architectural Impact: The location of the Martin Bomber Plant at Offutt during WW2 would become a large influence in bringing SAC to Offutt Air Force Base after the War. In addition to its desirable geographic location, the Martin Plant influenced the relocation of SAC to Offutt because of the already existing architecture to support SAC’s work. Strategic Air Command’s first 9 years at Offutt were spent in the Martin Company’s “A” Building adjacent to the main assembly building. It is interesting to consider how the architectural typology of production, along with the efficient and standardized methods of General LeMay, might have influenced the culture of the command during this time.

GLENN MARTIN COMPANY:

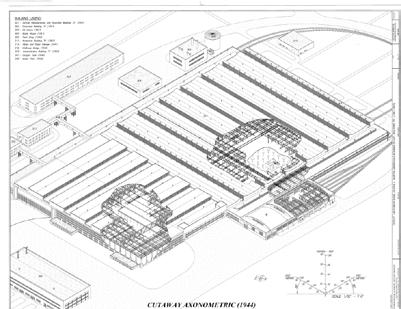

The Martin Company was an aerospace manufacturing company that produced aircraft for the US, primarily during World War Two and the Cold War. The Martin Bomber Plant was one of the four manufacturing plants in Nebraska and operated at Offutt from 1942 to 1945. Constructed in 1941, the main assembly building was designed by architect Albert Kahn and measured 900 by 600 feet. It remains one of Nebraska’ most noteworthy historical structures and a feat of engineering and architecture (Historic American Engineering Record, n.d.). Along with the assembly building, two mile-long runways and six large hangars were also constructed at Offutt for the Company (“History of Offutt Air Force Base” 2005).

500 BUILDING:

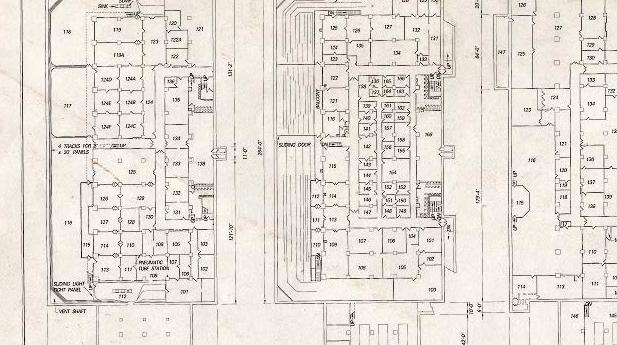

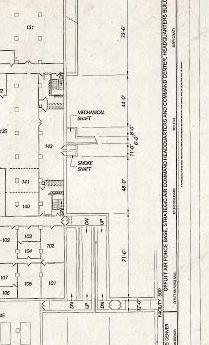

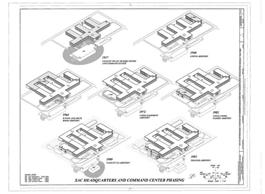

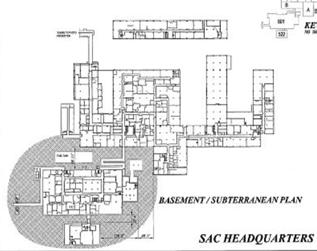

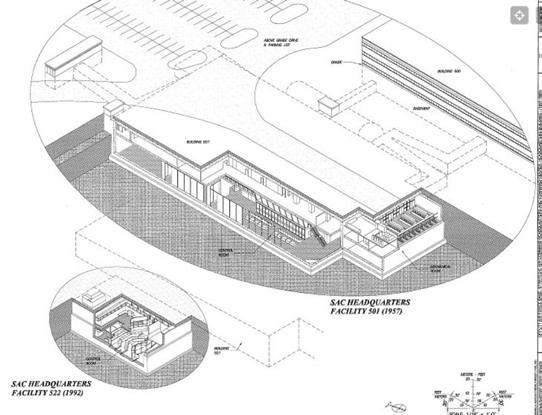

In 1957, construction was completed on a new headquarters for SAC, known as the “500 Building,” Leo A. Daly was the architect on the project. The building was described as the “Western Pentagon,” a heavily fortified structure with offices above ground and a threestory command post below ground. The above ground structure was made of reinforced concrete and masonry, with the below-ground structure of hardened reinforced concrete. The underground had two-foot thick walls and ceilings up to almost four feet thick. Ramped circulation throughout the below-ground post earned it the name of the “molehole”. It contained state-of-the-art technology, displays, and communication connecting SAC to their assets and the rest of the world. At the same time, the post could be completely self-contained, able to sustain 800 people underground for up to two weeks (Pike 2000). Additions were made to the original structure in 1959, 1962, and 1970 (Historic American Engineering Record, n.d.).

Architectural Impact: The 500 Building strongly reflects the influences of the Cold War on military architecture. Its construction is a response to the efficiency, strength, and permanence that Strategic Air Command wanted to promote. The architecture then had an influence itself on public perception of the U.S. and SAC’s strength during the Cold War. Its hardened appearance above ground reflected the true hardened underground, as well as stood as a symbol of the permanence of the nation itself (Pike 2000). It is also interesting to consider the influence on the perception of different groups, from the public viewing the building from a distance as well as those working in a fortress-like building each day.

Architectural Impact: The second Underground Command Center can be seen responding to the advances in military technology while still hearkening to the importance of the bunker established in the Cold War. Public perception and the media continued to play a heavy role in its construction. Many speculated that the reality of the architecture was conformed to a fictional ideal promoted by the media’s depictions of SAC and the military (Pike 2000). This occurrence marked a shift in military architecture, and as technology continued to evolve and more protection happened in the invisible realm, image and perception would continue to have more of a sway on the visible architecture of Strategic Command.

SAC UNDERGROUND COMMAND CENTER:

In 1987, a new Underground Command Center was completed for SAC. The new center, which was attached to the original underground structure of the 500 Building, was a 16,000-squarefoot reinforced concrete and steel structure. Special features include its resistance to electromagnetic pulse, and an underground water supply in case of lockdown. Similar to its predecessor, the underground post had cutting-edge technology and made continuous updates to its displays and communications (Pike 2000).

OFFUTT AFB EXPANSION:

Offutt AFB also modernized many of its facilities and amenities across the base during this time. The federal Wherry Act in 1949 and Capehart Act in 1955 promoted the construction of family housing on and around military bases across the country (Macken n.d.). Offutt constructed 2000 family housing units in the late 50s and 60s under the Wherry and Capehart Acts. Later construction at Offutt included a new hospital, main exchange, commissary (grocery store), and library built in the 1960s and 70s (“Offutt Air Force Base” 2024).

Architectural Impact: Offutt AFB responded to the growth of SAC during the Cold War with major expansion across the base. The Wherry and Capehart acts provided places to live for both a growing number of service members as well as, for the first time, their families. The unique climate of the Cold War led to soldiers and their families residing more permanently on military bases for the first time, which in turn created a demand to support amenities like healthcare and shopping on Base. It is also interesting to consider the implications of a base having everything it needs to be relatively self-sustaining, and what message this sent to those living on the base as well as those outside.

The events of the Cold War would directly influence the architecture of the 1950s and 60s. The political climate and the image of the U.S. Military during this time greatly contributed towards architectural style, especially in military architecture such as SAC’s headquarters. Constructed at the peak of this influence, the 500 Building displays how war and military events profoundly shape the built environment.

Firstly, the Cold War led to the literal and metaphorical construction of bunker architecture. With growing fear over the threat of nuclear war, the construction of literal bunkers and fallout shelters began in the U.S. Bunkers and bomb shelters were constructed underground or in the lower stories of buildings, along with teaching people to practice “duck and cover” drills for the event of a bomb strike (Penny 2011). The influence of the bunker was also seen in more subtle ways, as many buildings of the time were constructed to be low to the ground with simple and unassuming exteriors, few windows, and more extensive underground spaces.

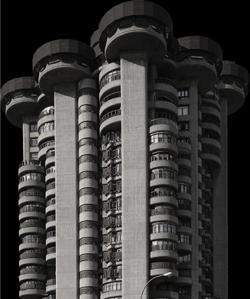

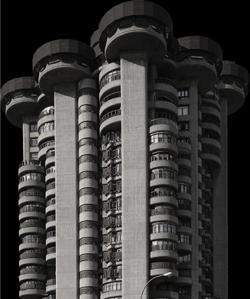

The growth of Brutalism as a style in the U.S. also went hand in hand with the appearance of the bunker. Brutalism was an architectural movement that emerged after World War Two beginning in Great Britain. Its main ideas were rooted in functionality and monumentality, spurred on by a need for speed and simplicity of construction while rebuilding from the destruction of the War (“Brutalist Architecture” n.d.). Brutalism was a direct adaptation of earlier modernist movements such as the International Style and the Bauhaus movement, which both emerged in the rebuilding from the First World War. (“Destructivism” 2022).

Similar to the Bauhaus and International Styles, Brutalism was based on functionality and minimalism, with solid, unfinished materials and large, geometric forms. Brutalism’s defining feature was its use of raw concrete on the exterior, wanting to draw attention to the mass and heavy feeling of the material. Brutalism made its way to the U.S. in the 1960s, especially for use in academic buildings, corporate headquarters, and government buildings (“Brutalist Architecture” n.d.).

The popularity of the style coincided well with the height of the Cold War and the rise of bunker-like buildings. Brutalism had many

similarities to the bunker style of low-to-the-ground buildings with little ornamentation and solid exteriors. Brutalism’s ideas of monumentality and permanence as well as the physical attributes and practicality of concrete were appealing, especially for military construction. The style produced a feeling of a stronghold that evoked security, the keeping of enemies out and those inside protected. The practicality of protection was at times secondary to the image, with the reality of these buildings surviving a nuclear attack being slim. However, the image of monumentality and permanence that they portrayed served more to send a message both to those at home and enemies abroad (Pike 2000).

The SAC 500 Building exemplifies the influence of bunker and Brutalist architecture during this period. As Strategic Air Command became an important part of the United States’ defense efforts, it was a requirement their headquarters appropriately symbolize their position. Although the exterior is primarily brick and reinforced concrete rather than the raw concrete of the Brutalist style, the headquarters is flat and low to the ground, mostly solid mass with small strips of windows, creating a fortress-like compound through interior courtyards. The headquarters hides its most important operations in a three-story underground complex with two-foot-thick walls and an almost four-foot-thick roof to protect it from nuclear attack.

The 500 Building exemplifies the use of the bunker both literally and stylistically in military architecture. While the Cold War led to the construction of literal bunkers on military sites, the influence of the bunker also translated to the visible portions of the architecture as well. In addition to the below-ground complex, Strategic Air Command used the bunker style to give the appearance that their headquarters was secure, strong, and able to resist an attack. This image of strength was perhaps even more important than the physical strength of the materials, as it played into the public’s perception of what made a building and the country safe and secure from attack (Pike 2000). It was essential that SAC continue to assure the public of their safety and of the nation - and its buildings - permanence.

After the events of the Cold War, U.S. leaders sought a unified command for all the country's nuclear forces. In 1992, SAC joined with the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff, a combined Navy and Air Force command that had overseen the use of nuclear forces during wartime. These two commands combined to form the United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), marking the end of Strategic Air Command (“History,” n.d.). With the creation of STRATCOM, all three legs of the “nuclear triad” now fell under one command (Terdiman 2013).

STRATCOM TIMELINE

This timeline charts the history from the establishment of the modern USSTRATCOM to the present day. Notable world events, architecture, people, and SAC events are sorted vertically to understand the connections between these occurrences over time.

2001: 9/11 Attacks and War on Terror begins

2003: Iraq War begins

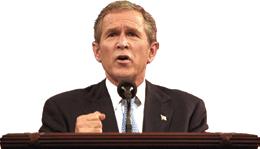

2001: President Bush Conferences in STRATCOM underground bunker after 9/11 attacks

2005: Offutt begins several renovations, leading to new housing, a firehouse, and other facilities

2002: STRATCOM merges with Space Command

2010: First Arab Spring uprisings

2011: Iraq War ends

2012: Construction completed on new STRATCOM Gate at Offutt

2009: The Air Force Global Strike Command becomes the newest command created to support STRATCOM

2008: A malicious code infiltrates DoD networks

STRATCOM destroys a satellite attempting to re-enter earth’s orbit

2010: US Cyber Command established as a sub-command of STRATCOM

2014: STRATCOM directs bombing missions Libyan Civil

2022: Russia invades Ukraine

STRATCOM bombing during Civil War

2021: US troops withdraw from Afghanistan

2019: Construction complete on new STRATCOM headquarters and underground command center

2019: Flooding causes destruction at Offutt

Late 2020s: Estimated completion of rebuilding efforts after flooding at Offutt AFB

2019: Charles Richard becomes commander of STRATCOM

2022: New runway completed at Offutt

2023: Ground broken on new campus for 55th Wing Security Forces Squadron at Offutt

2022: Gen Anthony Cotton takes command of STRATCOM

2022: Nuclear threats from Russia place STRATCOM in the spotlight

2020s: STRATCOM aims to modernize the US nuclear triad with new subma rines, bombers, and ICBMs

CREATION OF USSTRATCOM: In 1992, SAC joined with the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff, a combined Navy and Air Force command that had overseen the use of nuclear forces during wartime. These two commands combined to form the United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), marking the end of Strategic Air Command (“History,” n.d.). With the creation of STRATCOM, all three legs of the “nuclear triad” now fell under one command (Terdiman 2013).

CYBER AND SPACE COMMAND: The necessity for computer security and defense was recognized by the U.S. Military as early as the 1970s, but started to become a reality after the creation of STRATCOM. The modern U.S. Cyber Command was created as a subcommand of STRATCOM in 2010 and is now an important part of STRATCOM’s work (“Our History,” n.d.). Through Cyber Command, STRATCOM is responsible for operating the Department of Defense Information network (DODIN) which transmits, processes and stores all the information used by the Department of Defense (“What is the DODIN?,” n.d.). Their focuses include defending the DODIN, bolstering the nation’s ability to respond to cyber attacks, and supporting commands in carrying out their missions (“Our Mission and Vision,” n.d.).

Architectural Impact: The growing importance of cybersecurity to the military in the 21st century has led to changes in how its architecture must be configured. Despite protection in the digital realm being mostly unseen, it is likely to be reflected in the physical architecture of STRATCOM’s buildings as well. In the same way that Cold War architecture was concerned with the perception of security as much as security itself, modern architecture might likely consider how to promote the strength of their digital protection through visible means.

ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUM OPERATION: The electromagnetic spectrum is also increasingly important to the U.S.’s strategic efforts, and they must maintain an advantage in this domain. In 2023, STRATCOM created the Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) Operations Center, which helped to streamline the DoD’s Electromagnetic Spectrum operations. This was an important step in improving efficiency in operations related to Electronic Warfare and ensuring that the U.S. remains competitive on the national stage in this area. Similar to cybersecurity, a streamlined command for electromagnetic spectrum operations increases national security and allows operations to be carried out smoothly (U.S. Strategic Command Public Affairs 2023).

MODERNIZATION: Finally, STRATCOM is concerned with keeping a modernized arsenal with updates to all three legs of the nuclear triad. Modernization efforts are a top priority, as it can take significant time, money, and coordination to secure new capabilities (Gordon 2023). Although STRATCOM’s arsenal is still fully operational right now, in the near future, many of their current aircraft, ICBMs, and submarines will no longer be modern enough to be safe and viable. It is important to be forward-thinking about replacing outdated systems to remain prepared for the future (Pellerin 2017). STRATCOM is also considering the role of other emerging technologies, such as hypersonic weapons, artificial intelligence, and autonomous systems (Moriyasu 2023).

9/11: In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, then-president Bush and several of his team were transported to STRATCOM’s underground bunker at Offutt. This allowed him to meet with important officials and make decisions for the nation, as well as guarantee his safety and security. The bunker is located 40 feet underground STRATCOM’s 500 Building and is designed to withstand a nuclear blast. It has room to serve as both a command center as well as a hotel for the president and this team (Mastre 2021).

Architectural Impact: Although military installations and facilities like STRATCOM already had some security around access before 9/11, security and access control were significantly increased after. Military gates across the country standardized and upped their security for those getting on base, and this was only the first layer of protection. Facilities like the LeMay building include several layers of security inside to limit access to increasingly more restricted areas.

MIDDLE EAST:

STRATCOM, specifically their space-based command, communications, navigation, and surveillance, played an important role in operations in Iraq and Afghanistan in years following 9/11 (“History” 2018). STRATCOM was also involved in handling tensions related to the Arab Spring uprisings of the 2010s. Their work ranged from developing deterrence and contingency plans during the Syrian Civil War to directing NATO-supported bombing missions in Libya (Terdiman 2013). Into the present day, STRATCOM remains vigilant to threats, particularly nuclear, from a variety of nations including North Korea and China.

UKRAINE WAR: Most recently, STRATCOM has been in the spotlight following the start of the war in Ukraine and concern over nuclear threats from Russia. This has impressed the importance of modernization efforts to their deterrence capacities that have already been in the works (“Collaboration Between China, Russia Compounds Threat, Stratcom Commander Says” 2021).

Architectural Impact: With growing nuclear tensions with Russia, as well as other nations like North Korea, STRATCOM could face a return to the spotlight similar to the Cold War. This could have several consequences on future architecture. Considering the contrast between the wartime and peacetime architecture of STRATCOM, it is interesting to speculate on what new style could emerge with recent events.

GENERAL HENRY G CHILES JR: General Chiles Jr served as commander of STRATCOM from 1994 to 1996 and was the first Naval officer to command all of the United States’ nuclear forces. He was previously a Naval Rear and Vice admiral and commander of the Atlantic Submarine Forces, before becoming the deputy commander of STRATCOM in 1993. His main objectives during his time as commander were adjusting the structure and mission of the newly formed command to respond to the needs of the post-Cold War environment (“Henry G. Chiles Jr” 2023).

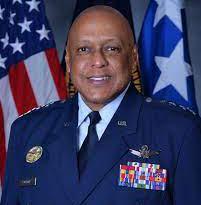

GENERAL ANTHONY COTTON: General Cotton is the current (2024) commander of USSTRATCOM, taking over the post in December 2022. He is a well-decorated Air Force general, having previously served at many levels of command including commanding the 20th Air Force and serving as President and Commander of Air University (“General Anthony J. Cotton” 2023). As a unified command, USSTRATCOM has men and women assigned from all five branches of the military. Its commanders also come from various branches. There have been seven STRATCOM commanders from the Air Force, five from the Navy, and two Marines (“United States Strategic Command” 2023).

Architectural Impact: The construction of the LeMay building enforces the continued importance of STRATCOM to the United States and the crucial mission of strategic deterrence. It also reflects the modern influences that are shaping current military architecture. The departure from a heavy, fortress-like construction to something much lighter and more vertical reflects the shifting message that STRATCOM wants to convey. It sends a message of being much more open and transparent about their work, even when the reality is ever-increasing security.

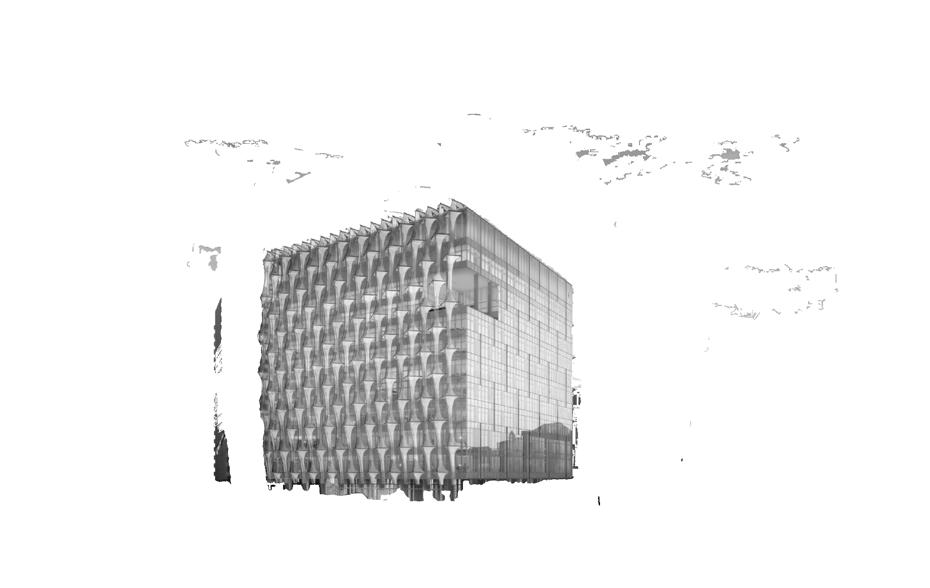

LE MAY BUILDING:

In 2019, construction was completed on a new Command and Control Facility to replace STRATCOM’s previous headquarters. The building, named after General Curtis LeMay, cost 1.3 billion dollars and contains not only an above-ground facility but an extensive underground command center (“U.S. Strategic Command’s Command & Control Facility Dedicated to Gen. Curtis LeMay’’ 2019). HDR was the architect on the project and designed it to mimic the masonry of existing buildings and Offutt while also contrasting past architecture with a lighter and more transparent façade. A central atrium hosts the more public programs and connects the two above-ground wings of the building which include more secure work areas. Multiple layers of security create a “building within a building,” with all of the critical functions happening below ground and behind several secure checkpoints (Tang, Doiel, and Bird 2021). The facility’s state-of-the-art technology and security features support the modernization of STRATCOM and give it the best ability to combat modern challenges (Pearson 2019).

STRATCOM GATE:

In 2012, work was completed on the New STRATCOM Gate, which would be the primary access point to the base. Designed by Yaeger Architecture, the design includes a new gatehouse, 4 ID check stations, and a new overhead canopy. It was designed to improve traffic flow – being located off of Highway 75 in Omaha – and make an impact on those visiting the base (“STRATCOM Gate,” n.d.).

Architectural Impact: The public perception of STRATCOM begins even before visitors reach any of their buildings. Military gates are important for promoting a base and the military’s public image, especially for visitors. The new STRATCOM Gate balances the objectives of creating a feeling of security for those entering the base while also appearing welcoming. Similar to the LeMay building, the gate has several layers of security, such as spiked barriers that can be raised in the event of a breach (“STRATCOM Gate,” n.d.).

Architectural Impact: Although rebuilding from the flood has been an unexpected challenge faced by Offutt, it has also created an opportunity to improve many buildings across the base. Future architecture will be more resilient to natural disasters, and more modern and connected than ever before. With massive rebuilding also occurring at the same time as the modernization of STRATCOM’s systems and weapons arsenal, it creates an opportunity to integrate the architecture with modernized assets in a direct way. The flood also proved to be a test of the LeMay building, whose roof sustained some rain damages but whose operation continued seamlessly throughout the disaster.

OFFUTT FLOODING AND RUNWAY:

In 2022, construction was completed on a new runway at Offutt, a project that took over a decade to fund and complete. It took several years of discussion and convincing to secure funding for the runway, after testing showed its condition to be one of the worst in the Air Force (Sanderford 2022).

This project faced delays due to widespread flooding across Nebraska in March 2019 that caused major destruction at Offutt. Flood waters covered over 1/3 of the base, damaging 137 facilities and causing an estimated $1 billion in damages. It took until 2022 to get financing and plans to start major rebuilding efforts (Garcia 2022).

NEW CONSTRUCTION:

Offutt is considering better ways to organize and operate the base through the widespread reconstruction following the flood. There are plans for twenty-six new buildings, which will be grouped into “campuses” of similar operations across the base (Losey 2020). Some have already begun, with the 55th Wing breaking ground on their Security Forces Squadron’s campus in March 2023 (“Ground broken on new 55th SFS campus” 2023) . The campus will be made up of three buildings totaling 100,000 square feet . Campuses for Nuclear Command Control and Communications and Satellite Command are expected to be forthcoming Communications and Satellite Command. Repairs are also focused on making Offutt even more resilient against future disasters, and more updates are expected in the coming years (Losey 2020).

Architectural Impact: STRATCOM’s priorities for the 21st century are mirrored in the built environment at Offutt. The wide variety of capabilities that they oversee, from satellites to cybersecurity to nuclear weapons to the aircraft that carry them, all require updates that make them ready to seamlessly integrate with each other and combat modern challenges. These new campuses will allow them to do just that with facilities that are organized while being more connected than ever before. The public facing element of these campuses is also important to consider. A modern, integrated, and visually impactful base reflects that STRATCOM is ready for the 21st century and that the nation still values investing in their strategic work.

In the same way that events of the Cold War period influenced its architecture, modern trends in military architecture can also be seen responding to current world events. The new LeMay Building constructed at Offutt is a great example of forward-looking construction in a military setting. Compared to the old SAC headquarters, the LeMay Building and other modern military buildings create a more updated look with increased glass and transparency. Rather than trying to appear unassuming like the bunker architecture of the past, modern military architecture is more boastful, emphasizing height and verticality more often. These features are not coincidental, but similar to the style of the Cold War, these modern stylistic trends reflect the events and values of the twentieth century.

Firstly, the use of transparency is not only stylistic, but actually symbolic of the goals the government is trying to convey. It is used to evoke a feeling of openness and transparency around the military’s operations. Rather than appearing closed off and secretive, this clarity appears democratic, making the public feel like there is nothing to hide (Baratto 2023). Taller windows as well as overall height give these buildings a more boastful feel, rather than the lower and more unassuming construction of the Cold War. However, this is actually to achieve a similar objective as before: to emphasize the monumentality of the building. While Brutalist buildings did this through the solidness of the materials, the LeMay building does it through the strategic use of heavier materials alongside larger, vertical windows (Tang, Doiel, and Bird 2021,). The effect is a similarly monumental structure, sending a message of STRATCOM’s prominence and permanence, while simultaneously its transparency.

Although glass and “lighter” materials might give the impression of a less secure facility, modern military buildings are as, if not more, defended than those of the past. Protection in these designs happens through the idea of a “building within a building” (“USSTRATCOM Command and Control Facility” 2023). Although the transparent exterior may disguise how secure the facility is, in reality, there are several layers of protection embedded after one enters the building. The most confidential activity is embedded at the core of the building behind several secure entrances (The Associated Press

2019). At Offutt, much of the activity is also embedded in the extensive Underground Control Center underneath the LeMay building itself. The real operation occurs beneath the ground, contrasting the appearance of visibility and openness above. Little is known about the current underground center, but the previous underground was a 16,000-square-foot facility made of thick hardened concrete with the ability to be sealed off from above. The below-ground post has all the information and technology to continue to manage STRATCOM’s forces, even in the event of a lockdown (Pike 2000)

Protection in the digital realm is also growing in importance, and this is just as important for architects to consider as physical security. At Offutt, this is done through construction that protects against electromagnetic attacks in the underground command center. As more of the protection in military buildings moves inward or happens in invisible ways, the outward construction is freed to take on whatever form it wants. Thus, the public image and messaging will likely continue a heavier influence on the exterior of these buildings.

A building that showcases similar ideas is the U.S. Embassy in London. The architecture of the embassy was designed to contrast embassies of the past that had been removed from the city, heavily fortified, even bunker-like. The London Embassy Is the opposite, as a large cube-like shape with a glass façade situated nearer to the core of the city. The transparency of the exterior physically allows more openness to the public but also symbolizes the transparency of diplomatic activity happening within. However, a high level of security is achieved despite the exterior’s appearance through construction that allows it to be blast resistant, layers of protection within, and various site features that double as extra layers of defense. (Hurley 2017). While strength and security are clearly still important, bringing the public into the process more, or at least the appearance of this, is also important.

The message of modern military architecture is heavily contrasted with that of the Cold War era. Many modern military buildings use transparency to promote the symbolism of democracy to the public. However, these modern buildings are as secure, if not more than, their predecessors, utilizing technology and layers of protection to keep the most important aspects of their operations safe.

In both the past and the present of military architecture, the built environment has reflected the world events and political climate occurring at the time. Another study of military architecture summarizes, “Architectural influences can indicate the time or period of a building’s construction, as well as the trends of the country and region at that time. Buildings on military installations are no exception and their architectural influences reflect the historical evolution of the installation, the military service, and DoD” (Michael, Smith, and Sin 2011, 2). This rings true for the architecture of STRATCOM, which can be seen reflecting the architectural trends of the time, the events of the past and present, and the messaging of the DoD.

As evidenced in the SAC 500 Building, Cold War-era military architecture often had features reflective of nuclear bunkers and Brutalist influences. These buildings portrayed an image of strength and permanence, the ability to keep enemies out and those inside safe. Modern military architecture utilizes more windows and lighter materials to symbolize transparency to the public. Much of this happens on the façade, while the secure interior creates a building within a building to protect its internal operations.

Both styles have similarities, as both aim to promote permanence or monumentality. While Cold War architecture did this through the heavy form and materials such as masonry and concrete, modern architecture does this through verticality and the strategic use of these heavier materials. Both styles also reveal a consideration for the public perception of STRATCOM and the military in general, which sometimes contrasts with the reality of the architecture. With both the 500 Building and the LeMay Building, there is an emphasis on the outward image of the building, even when its true security took a different form.

Typical commercial aircraft cruising height: 5.9 to 7.2 miles

International Space Station: 254 miles

Wideband Global SATCOM Satellites: 22,000 miles

STRATCOM oversees the Wideband Global SATCOM system, a system of satellites that provide communications for the US military and other partner nations.

Operation Looking Glass: 7.5 miles

STRATCOM’s Airborne Command Post primarily serves to relay information to submarines as well as serves as an emergency command post should the Underground Command Center become compromised.

Military jet ceilings: 9.4 to 11.1 miles

Electromagnetic Spectrum STRATCOM leads cutting edge advancements in the US’s electromagnetic spectrum capabilities. The new Underground Command Center is also protected to withstand electromagnetic attacks.

STRAT Gate: 1500 ft

One of three points of entry to Offutt AFB. This is the closest gate to the new STRATCOM headquarters and provides the first layer of security.

STRATCOM Underground Bunker: -40 ft Immediately following the events of 9/11, President Bush was flown to this underground bunker to keep him secure while he communicating with his team. It has since been taken out of use.

TownofBellevue , NE:2.5miles

USSTRATCOM Headquarters

Construction of STRATCOM new Command and Control Facility was completed in 2019. Named after General Curtis Le May, the building is almost one million square feet and cost $1.3 billion dollars.

Underground Command Center

Both STRATCOM’s old building (now home to the 55th Wing) and new facility have extensive Command Centers that are located underground. The newest underground command center is heavily encased in layers of steel and concrete.

Submarine Diving Depth: -800 ft STRATCOM has command over the US Navy’s 18 nuclear-powered submarines, including 14 ballistic missile submarines.

Underground Telephone Lines

STRATCOM has their own dedicated telephone circuits that equip their Primary Alerting System. They use this so-called “Red Line” system to send and receive coded messages to and from their other operating locations or other crucial offices.

STRATCOM is one of the DoD’s 11 Unified Commands and reports to the Secretary of Defense at the Pentagon.

Offutt AFB Runway

The 55th Wing at Offutt AFB currently employs 29 aircraft comprised of 6 variants of the OC, WC, TC, & RC-135 aircraft.

Water Table: -30 to -500 ft

The Ogallala Aquifer underlies most of the state of Nebraska as well as parts of 7 other Great Plains states. The water table is around 30 to 500 ft below the surface, while the Aquifer reaches up to 1000 feet deep in some places.

Underground Missile

STRATCOM overseas the systems. Many now-unsed across Nebraska from Cold Atlas-F missiles.

United States Strategic Command has a rich history that is deeply entwined with Nebraska and Offutt Air Force Base. From its origins as Strategic Air Command to its peak in the Cold War to modern challenges and beyond, STRATCOM has become an important part of the state’s history. As its role and shape have shifted, so has its architecture. Furthermore, the events that shaped STRATCOM’s history have also shaped the architecture not just of Offutt, but of the nation. Architecture, especially of the military, has responded to the unique influences of military and world events throughout history. The Cold War period and the modernday provide an interesting comparison that exemplifies this and creates a framework to perhaps consider the future architecture and events of Strategic Command.

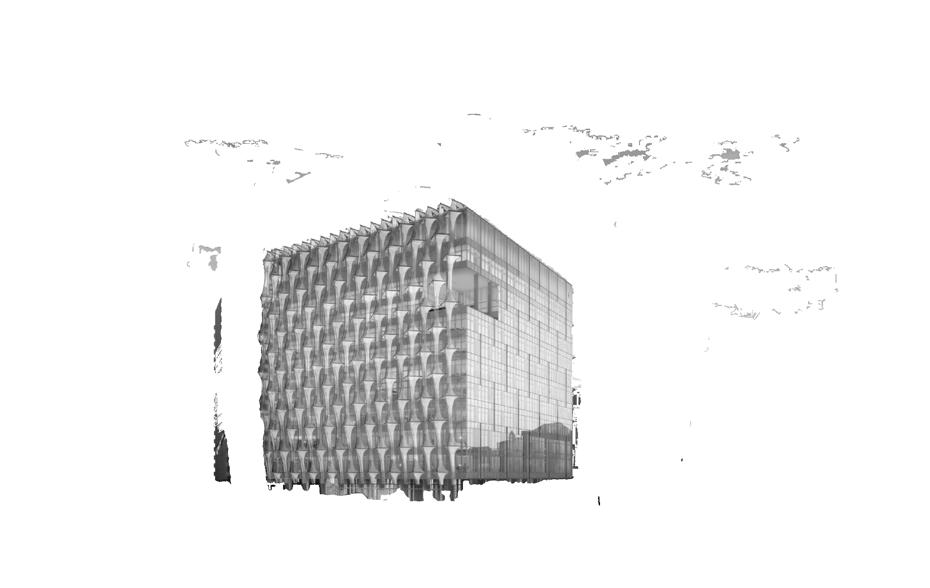

A SECTION OF STRATCOM

Inspired by a traditional architectural section, this drawing plays with scale and collaging to graphically communicate both the architecture as well as the “system” of STRATCOM. The goal of the section is to display the relation of STRATCOM at Offutt AFB to its greater local and global context. This allows the section to communicate the different functions of Strategic Command, including the different aircraft, subcommands, and facilities they oversee, giving a feel for the worldwide reach that STRATCOM has.