IN CONVERSATION

WINTER 2018

AUTUMN /

SHOWROOM

St Ives Retirement Living engaged Wood & Grieve Engineers to find lighting solutions to accommodate the design aesthetic of the apartments as well as the multi-function shared spaces, whilst providing visually comfortable illumination that is also safe for all residents.

At the heart of St Ives Carine the luxurious shared spaces are designed to be enjoyed as an extension of the magnificent apartments. Beautifully considered and decorated throughout, the entry plaza makes an impressive welcoming statement featuring iGuzzini Underscore to highlight the ceiling space, and iGuzzini Front Lights to illuminate the lounge in front of the stunning double height glass feature wall.

Beyond reception is the intimate mezzanine library and restaurant with outdoor terrace overlooking the central village gardens. The landscaping, provides areas to explore both day and night including the pond, pool, gym and giant chessboard with pathways illuminated by iGuzzini Twilight post tops and iGuzzini Light Up Walk.

St Ives Carine sets a new benchmark in luxury living for retirees with stunning architecture, interiors and beautifully landscaped amenities.

HASSELL Studio ARCHITECT For more information speak to one of our lighting application specialists or visit the online project page using the QR code reader on your smart-phone. +61 8 9321 0101 mondoluce.perth mondoluce.com.au

CLIENT St Ives Retirement Living ARCHITECT HASSELL Studio ELECTRICAL ENGINEER Wood & Grieve Engineers BUILDERS BGC Construction ELECTRICAL CONTRACTOR Lindquist Electrical Services PHOTOGRAPHER Ron Tan

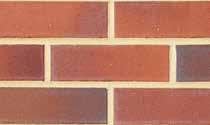

AN INSPIRING LESSON IN BRICK DESIGN

Highgate Primary School’s new double-story early childhood centre turns the familiar into the unexpected to create a surprising and adventurous place of education. Midland Brick sat down with Adrian Iredale from iredale pedersen hook architects to learn more about this striking project.

Q: Being a project for many varied occupants and stakeholders, how did you approach the design and project management?

A: We did our homework! From the very beginning, we set out to ensure that everyone was consulted throughout the process – from the client and builder to parents, teachers, the local community and the Heritage Council of Western Australia.

We knew we had a responsibility to create something that was to become an integral part of the community; a building that related to the school’s historic past, as well as its future.

It was a journey of discovery. We had to consider everything from a child’s perspective and create an environment that was a place of adventure and learning. We also had to reflect on how the teachers operated and engaged with the children, all whilst working within an established planning structure set out by the Education Department. So, on one hand we had massive creative freedom and on the other, strict guidelines.

Q: What gave you the inspiration for the unique style and use of brickwork?

A: Understandably, the existing buildings and immediate backdrop, and indeed the neighbouring streetscapes all had a significant bearing on our design.

PROJECT: Highgate Primary School Extension

BUILDER: Broad Construction

We also wanted to add to that, not just simply blend into the landscape – to make the familiar unfamiliar and surprising. One of these surprises was to engage the new building directly with the street, rather than the normal practice of fencing it off. This has created a unique community connection with the school.

From an external perspective, the brickwork has contributed greatly to the integration of the school with its surrounds. Although the brickwork appears very complex, in reality it is a simple blend of three Midland Brick reds – plus the exceptional skills of the bricklayers!

The actual blending of the three different coloured bricks was probably the most critical factor. We didn’t want a pattern to evolve, but a randomness that harmonised with the schools existing weathered brickwork. What we achieved were walls of random patterns where children can discover their own shapes and outlines in brickwork that is almost three-dimensional.

Q: What do you believe has been the most pleasing outcome of this project?

A: Definitely the widespread acceptance and the sense of community involvement. We had amazing support throughout from everybody involved, which lead to the project coming in under time and under budget.

ARCHITECT: iredale pedersen hook architects BRICKS USED: Burnished Red, Heritage Red, Kalbarri

CLIENT: Department of Education and Department of Finance Building Management and Works

- 2 -

- 3BRICKS BY

BURNISHED RED

HERITAGE RED

KALBARRI THE RESULT

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PETER BENNETTS

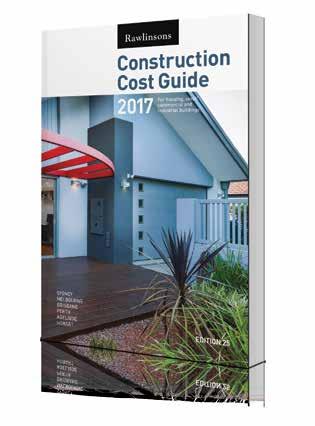

Rawlinsons Australian Construction Handbook and Rawlinsons Construction Cost Guide 2017.

Rawlinsons HAND BOOK $420 INC GST COST GUIDE $285 INC GST Reflect on the budget

PH 1300 730 117 OR WWW.RAWLHOUSE.COM AVAILABLE NOW

The Official Journal of the Australian Institute of Architects: WA Chapter

CONTENTS

contributors

7 editor’s message

9 WA chapter president’s message

people

13 bev’s house 17 client liaison

23 imagined worlds 25 optus stadium

29 the living knowledge stream

31 north west community buildings

35 conversations on heritage

39 ronnie nights

43 weight = mass x gravity

place

49 guardians of place

53 grey street house

59 can you hear me?... you know what I'm saying?

63 in conversation with fremantle’s built heritage

69 roscommon house

73 conversations in time

77 a conversation through buildings

81 creating sustainable relationships

85 coming to perth as a migrant

extras

16 rawlinsons costings extract pull-out postcards

The Architect has been in circulation since 1939 and is highly valued by both Institute members and the broader design professions. Generous financial contributions from architects over the years have helped sustain the magazine and we thank the following practices:

- 5 -

6

CONTRIBUTORS

Janine Betz is a German architect with a passion for placemaking & sustainability. She is a founding member of SCCANZ’s ‘Emerging Innovators’ and works for Lendlease.

Michael Gay is the 2017 WA Emerging Architect Prize Winner and a director of MSG Architecture.

Andrew Boyne is a sole practitioner who focuses on residential and prefabricated architecture. In 2015 Andrew received the Gil Nicol Biennale Award.

Olivia Chetkovich is an architectural graduate with an interest in architectural education and publishing. Olivia is the immediately preceding editor of The Architect.

Neil Cownie is a Perth-based architect who incorporates landscape and interiors into his projects in a holistic way, responding to each project’s unique context.

Philip Gresley is a founding director or Gresley Abas and a believer in what good design can bring to a community.

Hannah Gosling is an architect currently residing in New Zealand who enjoys exploring new places (both physical and virtual). She is a previous editor of The Architect.

Rosie Halsmith is the co-director of To & Fro Studio, a Perth based design and communications agency. She has a background in landscape architecture and community design.

Valerie Schoenjahn is a graduate of architecture. She works in small practice and as a tutor.

Geoff Warn is a director of With_Architecture Studio. He is also the Western Australian Government Architect.

Eddie Marcus (MA Cantab, MA Lond Met, PGDip Curtin) is a professional historian and heritage consultant, with a sideline in blogging about Perth’s more unusual historical tales.

Brett Mitchell is a creative practitioner working between academia and small practice.

Pip Munckton is a landscape architect, studio manager at vittinoAshe architects and works in research and design education at Curtin University.

Kylee Schoonens is Co-Director of Fratelle Group.

Bernard Seeber is a Perth architect working across residential and commercial projects.

Annette Seeman is an artist and academic living in Fremantle currently interested in borders and boundaries, working through drawing, print and photographic processes.

Alice See-Hoo works at Armstrong Parkin Architects in Fremantle. A Scottish transplant to Perth, Alice has lived and worked in Western Australia since 2013.

Kelwin Wong is an architect and graphic designer in Western Australia.

Warranty: Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

Important Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Institute of Architects. Material should also be seen as general comment and not intended as advice on any particular matter. No reader should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained herein. Readers should consult professional advisors. The Australian Institute of Architects, its officers, the editor and authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons whatsoever in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by any such persons in reliance whether in whole or in part upon any of the contents of this publication. All photographs are by the respective contributor unless otherwise noted.

Clancy White is founding director of Whitehaus Architects and a member of the Institute's WA Chapter Council..

Kate Woodman is an architect who previously worked for CODA Studio and COX Architecture in WA.

Joshua Wright is a game concept artist from Perth living in the eastern states.

Editor

Robyn Creagh and Fiona Giles

Managing Editor

Michael Woodhams

Editorial Committee

Holly Farley

Sarah McGann

Kelwin Wong

Magazine Template Design

Public Creative

Copy Editing

Gerard McArtney

Proofreading

Martin Dickie

Publisher Australian Institute of Architects

WA Chapter

Advertising Kim Burges kim.burges@architecture.com.au

Produced for Australian Institute of Architects WA Chapter 33 Broadway Nedlands WA 6009 (08) 6324 3100 wa@architecture.com.au www.architecture.com.au/wa

Cover Image

Leighton Beach Facilities by Bernard Seeber Architects. Image: Douglas Mark Black. Internal Covers

Leighton Beach Facilities by Bernard Seeber Architects. Images: Douglas Mark Black and Brett Mitchell.

Price: $12 (inc gst)

AS ISSN: 1037-3460

- 6 -

editors’ message

Robyn Creagh and Fiona Giles

Is the art of conversation being renewed in our day to day lives? When we take advantage of a ride-share, for example, we agree to be reviewed on our ability to give and receive hospitality. This sudden re-emphasis on transient verbal exchange is a un-looked-for delight. Have you had the experience of surprising yourself mid-conversation? That moment when you speak words to express something less than half admitted to yourself, or when you jump into an entirely new (to you) thought through collaboration with another. What a gift!

In these moments, through the help of others, we re-locate and re-define ourselves. Perhaps these responsive and interactive edges are where we are most interesting (not the deep dark crevices after all). And of course, as we move through the world, those edges are always shifting, and sometimes catalysing external changes. Perhaps we only exist in any meaningful way through the activity of our relationships: social, networked, urban…

Conversations are important from the very local, to the national and global scale. Practicing conversation — listening, empathising, sharing — is going to help us make space for more people to have a say. To hear the richness of stories and voices we’ve been missing. To recognise problems

and injustice and start finding ways forward. In our interconnected world, just avoiding metaphorical eye contact is not going to work. Uncomfortable conversations need to be had to negotiate a way forward. The headlines lately show we’ve started: change the date; #MeToo; institutional abuses; victims are being heard.

The continuing development of the built environment is inherently political, requiring conversations at every stage. Project inception needs careful consideration especially if it is government funded, many stakeholders need to be aligned and ready. Throughout the design process key conversations are required to understand client needs and to explain how the building will work — it is what architects are known for and what we can do best. Even beyond practical completion, successful building

management needs communication between users and operators. You might say that through (and within) architecture we have the opportunity to talk not only to people but also to places. Whether big or small players, at every step in the process there is negotiation. In this arena architects bring more to the table than just some fine-tuned aesthetics.

With this issue we ask questions to illustrate those other skills and hear about the value architects can bring to refine and define a brief, big picture thinking, achieving delight in unexpected places, and bringing people together to get a project over the line. Truly, architecture is a social endeavour. In this issue we’ve experimented with some new formats and voices. We’ve captured conversations between architects, feedback from clients, provocations from edges, and moments from continuing conversations with place and practice. And of course we have invited reviews and visual reflections.

If The Architect is part of a continuing conversation about architecture in Perth, then perhaps your voice has been missing? If so, please speak up. We’re listening.

Thanks to our amazing collaborators: the editorial committee and contributors. •

- 7 -

The Fielders Finesse range includes five unique profiles, Boulevard™, Shadowline 305™, Prominence™, Grandeur® and Neo Roman® that have been designed to combine the aesthetic appeal, durability and flexibility of steel cladding. All profiles are available in a diverse range of materials including traditional COLORBOND® steel and high-end COLORBOND® Metallic and Matt steel finishes, offering options to suit any style.

fielders.com.au/finesse

wa chapter president’s message

Author Suzanne Hunt

This edition’s theme of In Conversation resonates with me because one of my key goals as President is to broaden the conversation about architecture and architects, and the important role we play in cities and towns across WA.

Hopefully you have noticed the Institute being much more visible in the media via regular columns in The West Australian and The Post, and in June and July, I’ll be sharing the screen with other architect-presenters from around Australia as the second series of Australia by Design goes to air.

In a year of firsts for the Institute, this year’s WA Awards entries will be exhibited at Garden City Shopping Centre; part of our concerted effort to engage more productively with community. We’re hopeful that the associated school holiday activities will open the eyes of some school children to the power of design to effect real change and perhaps get them thinking about a career in architecture for themselves. Entries and winners will also be published in a newspaper liftout for Saturday readers of The West Australian the day after the awards and visitors to the exhibition will get a copy to take home, keep and use as a reference the next time they need an architect.

The other new thing is our choice of venue for awards night, somewhere more fitting and architecturally significant for our biggest event of the year. Cathedral Square has been an outstanding development in the heart of the city and we are thrilled to be holding

the events among the splendour of St George’s Cathedral and the Postal Hall.

Less visibly, but of equal importance, are the conversations we are having with state and local government — elected representatives, ministers, agencies and policy makers — to lobby for the inclusion of architects in key decisionmaking processes, and to improve procurement methods. We viewed the recent establishment of Infrastructure Western Australia and the MetroNet Industry Advisory Group as great initiatives, but continue to press for architects to be included at those tables.

The Institute’s strategic plan clearly identifies leadership and high impact advocacy as its main priorities, and we were delighted in April to host the State Government’s special inquirer John Langoulant AM in conversation at a forum of large practices. The thrust of the meeting was his findings of the Inquiry Into Programs and Projects (to which the Institute made a submission) and how better procurement processes will enable higher quality design and delivery of

public buildings. Mr Langoulant urged architects and our professional friends to argue as strongly as possible for the necessary changes. This involves raising awareness of our profession; reinstating architects as the lead consultants in the built environment; identifying and removing barriers that prevent us from achieving best practice outcomes; and highlighting the unique skills that architects offer — our holistic perspective and design thinking skills.

To a conversation that is of pivotal importance to our profession, one of fairness, safety and equity in workplaces. Our second #WorkWomenWisdom event, held in May just after this issue goes to press, builds upon the platform of #TimesUp, the US based movement with a vision specifically focussed on workplace issues. I’ve been heartened by the response to #WWW and while this occasion is for women only, I acknowledge that unhealthy work environments, bullying and inequality can be widespread and not limited by gender. Next time we will broaden the discussion to include the whole profession.

It has been a real pleasure to look at stories and projects featured in this issue, which demonstrate that we as architects are continuing to reach out to others in conversation — clients, end-users and collaborators — and to make valuable contributions to the built environment and society as a whole. •

- 9 -

- 10 -

people

- 11 -

- 12 -

Bev's House by Gresley Abas. Image: Dion Robeson.

In the Port Coogee development south of Fremantle, where proactive design guidelines have again failed to hold off a sea of rendered facades, feature brick and reconstituted limestone, Bev’s House by Gresley Abas feels like an anomaly.

The house is built on a 333m² lot that fronts a park, a street, a laneway and abuts the two-storey parapet wall of a neighbouring house. The parkland immediately in front of the house comprises a triangular lawn with perimeter planting that allows clear views over Cockburn Sound and toward Carnac Island. Just 20 meters away and running the entire length of the opposite side of the triangular park, a six-storey building by Cameron Chisholm Nicol with 101 apartments, provides height and volume that is in stark contrast to the two-storey homes which make up the bulk of the existing subdivision.

Bev’s House is an idiosyncratic name for a house which perfectly reflects the vibrant personality of its owner. It differs from the surrounding single-residential landscape through its avoidance of cement render and a pitched roof, but it does take on the Box-on-Base format that seems synonymous with Western Australian architecture over the last decade. This style has also been adopted by the opposing apartment building which stacks two rows of white box frames over dark-grey bases above each other. In Bev’s House, the base is constructed from a combination of

bev’s house

Author Andrew Boyne

concrete block and chocolate brick which is laid with relief brick detailing along the street frontage. The upper box is clad in white painted fibre cement with expressed joints.

With views in all directions, ocean breezes, and the sound of breaking waves, it feels as if the architects struggled to hold down the box form. It seems that the box has received gun-shot damage with a neat penetration on the street elevation resulting in the complete destruction of the box on the opposite side. Across the building, opaque fibre cement gives way to floor-to-ceiling glass, openness and views.

The Port Coogee development is typical of contemporary sub-divisions. It deploys a mix of medium-rise multiresidential buildings amongst small two-storey single-residential lots. On these small lots, which vary between 250m² and 400m², there is a tendency to build each house to the boundaries to maximise floor area. This results in tunnel homes with air and natural light only available from the front and rear elevations. By accommodating a three-bedroom, two-bathroom home in a footprint of just 7m x 10m, and by utilising the corner lot, Gresley Abas has pulled the two-storey structure from the boundaries to allow natural light into the home and air movement around it. This effect is further enhanced by separating the concrete block garage from the house proper and allowing a tropical resort style garden, complete

with a goldfish pond and an array of pink frangipanis, to encircle the ground floor. The interior spaces are each afforded views onto these gardens which transfer tranquillity into the home and provide a rare luxury of space atypical for small lot residences.

The house is arranged around a central two-storey service and stair core, painted in an ocean-inspired steel blue and accented beautifully with hoop pine detailing. On the upper floor, the open plan kitchen, dining and living spaces are placed on the park side of the building. These have ocean views through floor-to-ceiling glazing and spill onto a wide, covered deck. A guest bedroom and a small bathroom are positioned to the rear with views over the gardens. The ground floor accommodates a large open-plan master suite also with ocean and park views, while the laundry and a small guest bedroom are positioned to the rear. The desire to accommodate the lively spaces upstairs is complemented by a construction methodology which deploys masonry on the ground floor, creating a cooler, calmer atmosphere and light framing upstairs that feels warmer and brighter.

Despite its strong form, it is the transparency of this building that makes it particularly distinctive. It is fundamentally a public residence. The master bedroom is clearly visible from the public park and the apartment buildings across it. The visible bedroom also forms part of the entry sequence that comes off the park, runs along

- 13 -

•

- 14 -

Bev's House by Gresley Abas. Image: Dion Robeson.

Bev's House by Gresley Abas. Image: Dion Robeson.

the fully glazed bedroom, through a gate and to a front door fitted flush into the curtain glazing system. Upon opening the door, the stairway rises directly ahead, with the two ground floor bedrooms completely unobstructed and visible on either side. This transparency is carried through to the main living spaces that have full height glazing and are all visible from the park. Subtle privacy is achieved via glittering drapes that remind Bev of the shimmer of the ocean and which introduce some reflection into the glazing during the day while all windows are fitted with recessed roller blinds, this is ultimately a very public residence.

Earlier this year, the UK appointed its first Minister for Loneliness in response to an ‘epidemic of loneliness’. In the United States last year, the Surgeon General published an article addressing workplace loneliness, and increased risk of heart disease, arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and dementia have recently been attributed to loneliness. When considering the typical arrangement of housing around the Port Coogee development it gives pause to consider

the role contemporary homes have played in the rise of social isolation and loneliness.

With automatic garage doors, houses built boundary to boundary, deep boxed-in decks, tiny low-maintenance irrigated front gardens and curtains pulled closed for privacy, there appears little opportunity for occupants to interact with the community around them. If this type of housing isn’t a major contributor to social isolation, it certainly cannot be helping.

By destroying the box form and opening the house to the views, Gresley Abas have also opened the house to the community. Bev happily described her first night in the home when she held a glass up in her living room and toasted with a neighbour in the apartment building across the park. She described cricket games on Christmas day with the neighbourhood and how she liked to wake to the yoga lessons occurring outside her bedroom. She was pleased as a young boy walked in front of the house, hands full with flippers and snorkel on his way to the beach. She described how she has now learnt the

bus schedule simply by watching and hearing the bus drive by, and she spoke of a Facebook page that she shared with residents of the neighbourhood, including the apartment residents that look into her home and how they provide an additional layer of security. The house is surrounded by parks and the movement of people and cars through those surrounding spaces bring action and vitality that lifts the home.

This is a beautifully detailed house but its great success is in the lifestyle it has afforded its occupants. By allowing an open connection between the occupants and the community, the lives of both are enriched. If architects are to acknowledge the significant impact their work has on the wellbeing of the people who occupy their buildings, perhaps Bev’s House by Gresley Abbas could act as a case study in how architecture might be able to facilitate community and ultimately promote wellbeing. •

- 15 -

1 COSTINGS

ESTIMATING AND CONSTRUCTION COSTS COSTINGS COURTESY OF RAWLINSONS, EDITORS OF RAWLINSONS AUSTRALIAN CONSTRUCTION HANDBOOK ESTIMATED BUILDING COST PER SQUARE METRE, PERTH – FEBRUARY 2017 PRICES PER SQUARE METRE GIVEN UNDER THIS SECTION ARE AVERAGE PRICES FOR TYPICAL BUILDINGS AND, UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, EXCLUDE FURNITURE, LOOSE OR SPECIAL EQUIPMENT AND PROFESSIONAL FEES. IT MUST BE EMPHASISED THAT ‘AVERAGE’ PRICES CAN NEVER PROVIDE MORE THAN A ROUGH FIRST GUIDE TO THE PROBABLE COST OF A BUILDING. PRICES QUOTED ARE FOR THE METROPOLITAN AREA. THE MEASUREMENT OF THE SQUARE METRE AREA OF A BUILDING IS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE METHOD ADOPTED BY THE NPWC: THAT IS, LENGTH AND WIDTH MEASUREMENTS TO BE TAKEN BETWEEN THE INNER FACES OF THE OUTER WALLS. COSTS EXCLUDE THE GOODS AND SERVICES TAX (GST) EXCEPT RESIDENTIAL HOUSES AND FLATS.

OFFICES AND BANKS

SUBURBAN BANK

Maximum 2 storeys, including standard finish, air conditioning, bank fittings, no lift

OFFICES

Low rise 3 storeys, air conditioning, lifts, standard finish

Medium rise 4 to 7 storeys, air conditioning, slow lifts, standard finish

Medium/high rise 7 to 20 storeys, air conditioning, medium speed lifts, standard finish

$ per square metre

2,665.00-2,870.00

2,185.00-2,355.00

2,445.00-2,635.00

3,320.00-3,580.00

High rise 21 to 35 storeys, air conditioning, multiple high speed lifts, standard finish 4,410.00-4,755.00

High rise 36 to 50 storeys, air conditioning, multiple high speed lifts, standard finish

CIVIC ETC

CIVIC CENTRE

Main hall 300/500 capacity and suitable for cabarets, conventions, anterooms, small kitchen, no air conditioning

Main hall capacity 500/750, lesser hall, library and kitchen, including air conditioning

LIBRARIES

Maximum 3 storeys, air conditioning, good standard finishes, excluding loose fittings

SUBURBAN POLICE STATION

Single storey, partial air conditioning, standard finishes, small cell block

INDUSTRIAL

FACTORY OR WAREHOUSE

4,870.00-5,250.00

$ per square metre

2,045.00-2,205.00

3,095.00-3,335.00

2,765.00-2,980.00

2,615.00-2,820.00

$ per square metre

Simple single storey with small span, including office accommodation 795.00-855.00

Single storey with large span, for heavy industry, including administration office and amenities area (factory 85% of area)

Multi-storey, maximum 6 storeys, including goods lift and office accommodation

MOTELS AND HOTELS

MOTELS/HOTELS

Motel, single or double storey, standard travellers-type accommodation, individual toilet facilities, dining room, unit air conditioning (cost per bedroom unit $74,600.00–$80,400.00)

Motel, single or double storey, high standard accommodation, restaurant and lounge facilities, swimming pool and other amenities, fully air conditioned (cost per bedroom unit

$101,000.00–$108,800.00)

1,210.00-1,305.00

1,580.00-1,705.00

$ per square metre

2,295.00-2,475.00

2,765.00-2,980.00

Tavern, including air conditioning 2,625.00-2,830.00

City hotel, medium to high rise, including air conditioning and lifts, having 60-65% accommodation area

(cost per bedroom $345,500.00–$372,500.00)

RECREATIONAL

CLUB PREMISES, SQUASH COURTS, RECREATION CENTRES ETC

Social/sporting club building, maximum 2 storeys, air conditioned, bars, kitchen and dining area, dance area, club offices, limited carparking

Single storey sports pavilion with toilets and changerooms, minimum finish

Basketball centre

Squash courts, basic developer standard

(cost per court

$125,200.00–$135,000.00)

Squash courts, high standard (cost per court

$225,500.00–$243,000.00)

Community recreation centre, basic standard

5,120.00-5,520.00

$ per square metre

2,575.00-2,775.00

2,390.00-2,575.00

1,295.00-1,395.00

1,390.00-1,500.00

1,880.00-2,025.00

1,000.00-1,075.00

Community recreation centre, medium standard 1,255.00-1,350.00

50 metre x 21.0m wide x 1.0/2.4m deep pool, fully formed, including filtration and pool siteworks but excluding heating and ancillary buildings (total cost $) 1,604,000.00-1,729,000.00

CINEMAS

Cinema, group complex, inner-city, including seating, stage equipment and air conditioning

CARAVAN PARKS

Basic standard caravan park, including communal facilities, electric power to all bays, small office, roads and parking

Medium standard caravan park, including communal facilities, electric power to all bays, office and retail, laundromat, barbecue areas, small swimming pool, roads and parking

High standard caravan park, including individual facilities and full services to each bay, office and retail, laundromat,barbecue areas, small swimming pool, roads and parking

RESIDENTIAL

HOUSES (including GST)

Standard project home (medium standard)

$ per person

12,460.00-13,430.00

$ per bay

20,500.00-22,100.00

28,880.00-31,130.00

39,370.00-42,430.00

$ per square metre

945.00-1,020.00 Medium

Townhouse, medium standard, 2 storey 1,815.00-1,955.00

FLATS (including GST)

One and two bedroom units, maximum 3 storeys, no lift, minimum standard (cost per flat $99,100.00–$106,800.00) 1,650.00-1,780.00

Multi-storey with lift and prestige standard of finish (cost per flat $660,000.00–$711,500.00) 3,475.00-3,745.00

AGED PERSONS’ HOMES (including GST)

Single storey housing units and additional central care units (cost per unit $127,600.00–$137,600.00) 2,125.00-2,295.00

Multi-storey units + min. lift service (cost per unit $125,800.00–$135,600.00) 2,735.00-2,945.00

EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL SCHOOLS $ per square metre

Primary or secondary, maximum 3 storeys, standard finishes, buildings only

1,700.00-1,830.00

Laboratory block, maximum 3 storeys, including fittings 2,270.00-2,445.00

UNIVERSITY

Administration block, including air conditioning 2,330.00-2,515.00

Tutorial staff and lecture rooms block, including air conditioning 3,065.00-3,305.00

Lecture theatre (250 seats), including air conditioning 3,340.00-3,600.00

Library, maximum 3 storeys, including built-in fittings and air conditioning but excluding moveable furniture 3,045.00-3,280.00

Laboratory + science block, maximum 3 storeys, including air conditioning 4,020.00-4,335.00 Residential college 2,465.00-2,655.00

HOSPITALS AND MEDICAL CENTRES $ per square metre HOSPITALS

District, single storey, 60-bed, operating theatre and partial air conditioning (cost per bed $200,500.00–$216,200.00)

3,715.00-4,005.00

General, multi-storey, 200-bed, including air conditioning and lifts (cost per bed $520,500.00–$561,000.00) 5,780.00-6,230.00

Maternity, multi-storey, 100-bed, including air conditioning and lifts (cost per bed $232,600.00–$250,700.00) 4,650.00-5,015.00

General practitioner medical centre, single storey, consulting rooms, surgery and small theatre, partial air conditioning 1,905.00-2,055.00

SHOPPING CENTRES AND DEPARTMENT STORES $ per square metre

RETAIL PREMISES

Single storey retail/showroom type, standard 'shell' construction, excluding air conditioning and fitting-out work 750.00-805.00

Super market, single storey, air conditioned but excluding fitting-out work 1,575.00-1,700.00

Regional complex, single or 2 storey, medium standard, including air conditioning, malls, circulation areas, excluding shop fitting-out work and carparking 2,070.00-2,235.00

Arcade shops under office tower 3,745.00-4,035.00

Suburban store of large chain, single storey with large open-plan sales area, including air conditioning but excluding carparking

City store, low to medium rise, fully air conditioned, served with escalators and lifts, inclusive of shopfronts but excluding shop fitting-out work 2,685.00-2,890.00

Parking areas, bitumen paved including lighting and storm-water drainage (per car $2,675.00–$2,870.00)

81.00-87.00

MISCELLANEOUS $ per square metre

ECCLESIASTICAL Church hall

CARPARKS

Multi-storey, basic finish with slow passenger lift (cost per car $23,700.00–$25,500.00)

1,080.00-1,165.00

860.00-930.00

Basement carpark under office tower 1,685.00-1,815.00

PRICE

- 16 -

standard individual house

standard house, no air conditioning

built-in furniture

good standard finish

1,680.00-1,810.00 High

but with

and

2,400.00-2,590.00 Prestige standard, partly air-conditioned 3,220.00-3,470.00

1,835.00-1,980.00

Chapel or church, simple structure 1,495.00-1,610.00 Chapel, church or synagogue, medium standard

Chapel, church

high standard

2,245.00-2,420.00

or synagogue,

3,190.00-3,435.00

index is not valid for housing, small projects or remote country work. Building Building Building Building Date Price Date Price Date Price Date Price June Index June Index June Index June Index 1994 106.04 1998 115.34 2002 126.07 2006 180.45 1995 107.63 1999 117.08 2003 133.10 2007 200.20 1996 111.42 2000 122.38 2004 147.24 2008 216.14 1997 113.65 2001 123.58 2005 163.87 2009 224.46 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 March 228.95 232.39 234.71 236.47 239.42 245.42 250.31 255.06(F) June 232.39 232.97 234.71 237.06 240.61 246.63 251.55 September 232.39 233.55 235.88 237.65 241.80 247.85 252.80 December 232.39 234.71 235.88 238.23 242.99 249.06 254.04 Example – to assess the percentage variation in cost between June 1999 and June 2002: Jun-99 = 117.08 Jun-02 = 126.07 = 8.99 x 100 = 7.68% 8.99 117.08 1

INDEX This

client liaison

We asked people what they thought of their new spaces… and of their architect.

Mati & Kaitlyn

KULD CREAMERY

Architect: ARCADIA

Describe the feeling of being in your new space?

Overwhelmingly, there is a sense of fulfilment and pride. Everything came together as we had wanted and some things even better than we imagined. It feels homey and loved even though it’s new and crisp, which is something we aimed for.

How did you meet your architect?

Word of mouth. A fellow business owner in Highgate had worked with ARCADIA on the design of their house. On their recommendation we contacted them for some design consultation, and once we had seen some of their work we were happy to proceed. Also they had really big, excited eyes and liked the project from the beginning.

What was unexpected about the process of working with your architect?

There were a few things. Firstly, the way they could read us and include little touches they knew we would like or would be meaningful. Also, the logical and simple solutions to problems that seemed pretty big.

And seeing everything in three dimensions took some of the fear out

of the process and helped removed the unexpected. Working with Amy, Sal and Mitch definitely took some of the weight off and allowed us to feel comfortable in the process.

Oh, and we had fun…

Before you started, what did you think ‘an architect does’?

Mati — I have been spoilt. I have four family members that are architects, so I had a pretty good idea.

Kaitlyn — I thought they built houses

and strictly did the bones of the building, the structural stuff.

What was the most pleasant surprise of the outcome?

How close the finished space was to everything we had been working towards. There weren’t any surprises. It was so seamless in how the design transitioned from computer-generated space into actuality. Everything was where it was supposed to be, and everything fitted. It was a pretty cool final experience.

- 17 -

•

Mati and Kaitlyn at Kuld Creamery by Arcadia. Image: Kuld Creamery.

Valerie Paul RESIDENCE

Architect: VittinoAshe

Describe the feeling of being in your new space.

I think one of my first feelings was that everything that had been chosen by us in conjunction with the architects fitted so perfectly together. It worked so well and provided me with exactly what I needed when I had downsized from my large family home of 40 years. My new space has now survived nearly two and a half years and I still have the same feelings of comfort, safety and convenience that I had when I moved in.

How did you meet your architect?

Initially we had numerous unsuccessful contacts with builders, architectsonline and draftsmen. My son and his partner had seen a 35m 2 unit that Katherine Ashe and Marco Vittino had designed and completed, which was included in a Perth Open House Scheme. They had both been very impressed by the Vittino/Ashe design for a small space and suggested that I should contact them to see whether they were interested in my 45m 2

Early in 2015 my family and I met the architects on site and after a short time we realised that we had the same ideas for my small project in an

iconic building and an agreement was reached.

What was unexpected about the process of working with your architect?

I was surprised that Marco and Katherine had each drawn up a separate plan then combined them to include the best features of both plans. Their attention to detail and understanding of my needs as an older person were paramount during the whole process of planning and the special features incorporated were not obviously just related to an older person. For example the continuous rail from the lounge to the bathroom, which was incorporated in the built-in cabinetry as a feature, and the built-in seat in the shower amongst others.

My family and I felt that this was not just “another job” for the architects or builder, but that we all had an interest in making the finished project as special as possible. We were included throughout in the choice of finishes, and nothing was included without consultation. In this way, everything that was included fits the design and the requirement for me to have a comfortable and easy-care home.

Before you started what did you think ‘an architect does’?

As my brother had been an architect in the UK, so I was aware that many duties

of the architect were dependent on what the owner required. In my situation, when we first met and discussed the project I asked questions about what they were prepared to do and the costs involved so that there were no surprises or misunderstandings.

What was the most pleasant surprise of the outcome?

With so many horror stories of renovations going wrong or not completed and cost blowouts, I was very happy that the project was completed in the twelve-week time frame, and within budget. It was completed in time for the 2015 Open House Perth Scheme and we had numerous visitors during the four hours that it was open to the public. Everyone who visited the unit expressed surprise and positivity at what had been achieved in such a small space to make it light, airy and extremely liveable. I still get a thrill to see other people’s reactions when they visit and I am able to say that without a doubt this unit has exceeded my expectations in comfort, affordability and ease of maintenance.

- 18 -

Valerie Paul in her home by VittinoAshe. Image: Robert Firth, Acorn Photo.

Abigail Barry

PROJECT LEADER, ASSET MANAGEMENT DIRECTORATE,

WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE FORCE

BALLAJURA POLICE STATION

Architect: TAG Architects

Describe the feeling of being in your new space.

The new Ballajura Police Station feels great to be in. TAG Architects has designed a tidy and functional building, with nice spaces for staff. I’m extremely proud of the work that we’ve done with TAG because there aren’t a lot of creative opportunities with a station, they are mostly built around operational efficiency, but with Ballajura Police Station we’ve achieved it all.

How did you meet your architect?

TAG Architects was appointed to the WA Police Force by Building Management and Works (BMW). They were already working on the Mundijong Police Station at the time.

What was unexpected about the process of working with your architect?

These two stations were TAG’s first contracts with the WA Police Force, so I’d say they were more surprised than I was! Police contracts involve using our Accommodation Standard, so architects might think that it is similar to schools, but it’s not. Stations are both very specific and flexible all at the same time!

A positive was that we gave them a brief and they came up with really good ideas. You hope for that, but it doesn’t always happen. If you relay the same information to a bunch of different architects you get different solutions and sometimes there’s magic — we got that with TAG.

Before you started what did you think ‘an architect does’?

I came into this role as a client representative for the WA Police Force, with a career background as a registered architect. That gave me a really interesting perspective on working with architects, as I have a firm expectation of what an architect should do.

In my role for the WA Police Force, I try not to prescribe the aesthetic brief, only the function. Sometimes, I worry that I might be too specific, I don’t want to limit creativity! I expect a lot in terms of communication, and sometimes initially my expectations aren’t met. But I find when I push a couple drawings across the table at a meeting, something shifts. Things just open up when the architect realises that I’m not trying to do their job, but that I understand sketching is the quickest way to describe things, from one architect to another.

What was the most pleasant surprise of the outcome?

Feedback from the frontline police officers has been the most pleasant

surprise. I build a relationship with station staff over the first year of occupation. Because part of my job is to get them settled in, it’s not a case of giving them a building and the keys, then walking away. Our Directorate recently did post-occupancy station evaluations with the BMW Building Research and Technical Services Team. It has been really nice receiving considered, positive feedback from people who have been officers for 30 or 40 years, who tell me “This is the nicest and the best police station that I have ever worked out of” or “There are things I’d like to change and here are some things to consider, but we really like our home base. We’re really proud of it, and we like working here.”

There’s a creative tension in designing police stations — trying to balance functionality with comfort and aesthetics, while meeting exact programs and very specific operational outcomes, and still delivering an ‘agile’ building. But that’s us, that’s the WA Police Force as a client, really! There isn’t a lot of scope for delight, unless you work really hard at it. TAG did, and the delight at the Ballajura Police Station comes from natural light in unexpected places, the feeling of belonging and of operating out of a safe haven; all very well-designed. My photo is of the inaugural team in front of their new home; they are the people I represent and advocate good architectural outcomes for.

- 19•

Ballajura Police Station staff. Station by TAG Architects. Image: WA Police Force .

Ana Ferreira Manhoso

PRINDIVILLE HALL

STUDENT SPACE @ NOTRE DAME

Architect: COX Team

Describe the feeling of being in your new space.

At times I find myself thinking about what the space used to look like, and it is certainly nostalgic to think of the 'dinginess' of memories in the old space — but now there is new life in here, and it feels very refreshing and sophisticated. Seeing the blend of all the new features with aspects of the old is exciting.

How did you meet your architect?

We discussed the priorities, services and uses of the old space, and then explored ideas, additions, and wishes for the new space. I remember we had an opportunity to really delve into how the space is used, by us as student council/ club representatives but also for the general student population. We visited each campus of all other universities in WA prior to this meeting, so we had photographs and ideas prepared to share with the architects and university staff.

What was unexpected about the process of working with your architect?

One of the most notable experiences I remember from collaborating with and

meeting the architects was the quick transition from simply discussing ideas to seeing a complete floor plan. The fast pace of this progress was really unexpected and it was inspiring to see our discussions come to fruition so quickly and accurately.

Before you started what did you think ‘an architect does’?

I was pleasantly surprised with the extent to which architects strive to incorporate their clients’ vision in the work.

What was the most pleasant surprise of the outcome?

Seeing the final touches come together and watching new students take in the beauty of our campus.

- 20 -

Notre Dame Prindiville Hall by COX Team. Image: Peter Bennetts.

Year 8 Students

PAUL RAFTER CENTRE AT IRENE MCCORMACK CATHOLIC COLLEGE

Architect: Parry and Rosenthal Architects

Year 8 Students react to the new Paul Rafter Centre at Irene McCormack Catholic College.

- 21 -

- 22 -

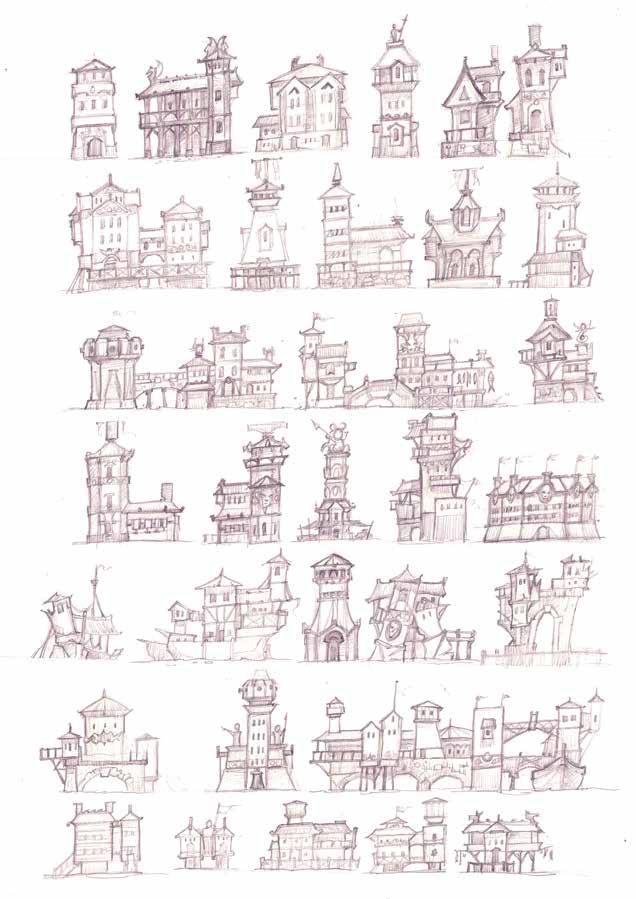

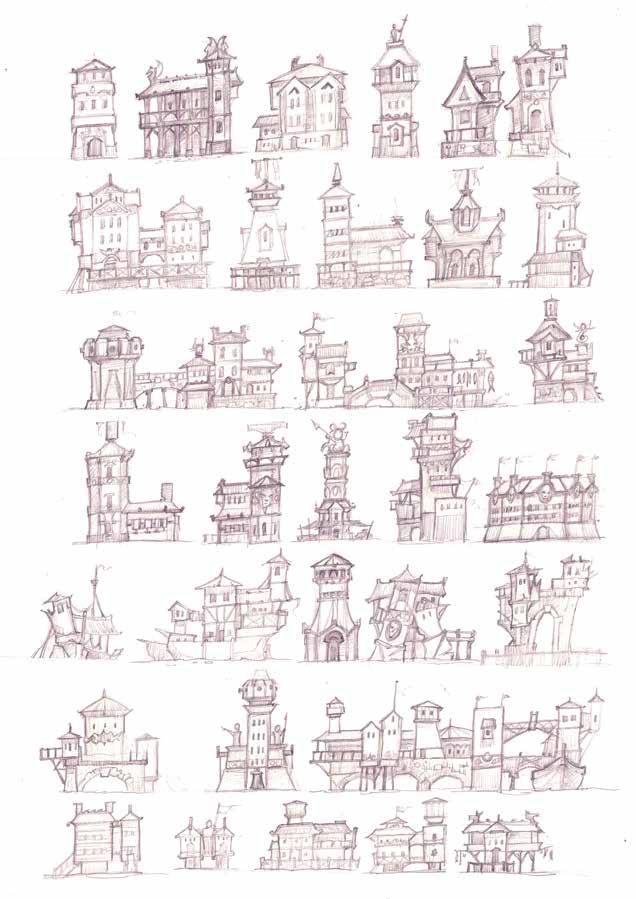

Concept Sketches, HalfArch buildings, Tin Man Games 2018, Table of Tales. Image: Joshua Wright.

imagined worlds

Author Hannah Gosling

I am an architect currently residing in New Zealand who enjoys playing games in my spare time. I think games offer ways to explore worlds in ways not available in other art media. I sat down for a chat across time zones with Joshua Wright, a game concept artist, to find out more about how he designs virtual environments. Within the conversation were some poignant reminders of things too often left to one side in architectural practice.

Josh, how do you go about designing a space or environment?

First you need to establish the visual style for the world the project will be set in. It must be unique and should be able to be used universally. This includes establishing what type of lines, shapes and forms are going to be used. The design objectives must be clear, and the design intent should be able to be distilled down to a simple sentence or word. It is important to spend time researching and establishing a strong style guide. As well as being a guiding document, it becomes a pot of visual ideas to draw upon, check against, and can become shorthand for communicating and explaining the design intent.

It makes me wonder, is enough time spent in architectural practices setting up visual reference documents? Are they provided to, and used by the designers, makers and stakeholders of a project?

To what extent do you draw inspiration from the real world?

Generally, everything has a real-world reference. You often borrow shapes and forms from different styles and experiment with mixing different styles and ideas together. Creativity is generally an iterative process and if something becomes too abstract then it becomes difficult for people to connect with. At the end of the day, the success of the project is determined by whether people connect with it and have a compelling experience. It is also important to spend time testing the environment with real players and observing people in, and engaging with, the created environment. Inevitably people will perceive and use the environment in ways that one has never considered and their perception or use should be considered to be as valid and valuable an experience as those that the designer intended.

There are questions that this raises for me: Can architects learn from the experience of the everyday person, and is the experience of the vernacular valued? What can be learned from ordinary spaces and extraordinary uses?

How do you create an impression of space, and how much detail do you include?

You have to remember that one thing on its own may not make a big impression or even be specifically noticed. But, one hundred things together help create the sense

of something. You can create a compelling experience without necessarily using photorealism, and even when photorealism is used, one has to be strategic about where detail is added and where detail is left out. Low resolution visual descriptors can still go a long way towards creating an atmosphere, especially when combined with audio or tactile descriptors.

A designed space or environment is essentially a collection of subtle and nuanced cues and gestures. As in any creative medium, you have to pick out what is described and what things are left for the imagination to fill in.

Think about your favourite book, painting or film. What is actually described and what only exists in your mind? This also raises the question: How many designed details and design decisions are actually noticed by the everyday user? And on the other hand, what real or imagined details make up the spaces and environments that people remember and love? •

- 23 -

- 24 -

Optus Stadium by HASSELL, COX and HKS. Image: Peter Bennetts.

During the Final Stages of Construction, we took a bus to site from the carpark. As it came into view, the stadium looked almost complete, but for the landscape of hoarding and construction traffic.

After the safety briefings, we made our way onto site through the mess hall. This was not just any site mess, thousands of workers ate lunch here. The number of workers was not apparent until a shift ended, and our tour group was overwhelmed with the stream of people passing us — the hoarding was not quite designed for the mass exodus.

We passed through the service areas and waited for one of the construction elevators. After exploring the various and novel entertaining rooms on offer (you can listen to the coaches strategising if you leave your phone at the door, watch the players warm up or simply enjoy views of the Swan River…) we then made our way to the main event.

Sitting in the stands watching the trucks levelling the pitch was something else. From our high vantage point, the diggers zoomed around like Tonka trucks moving the sand from piles to the pitch.

I came away from the visit very aware of the importance of individual cogs in the very big construction machine.

optus stadium

Author Fiona Giles

The building and the landscape.

Post Practical Completion

Another visit, another car park. This time I snuck in on foot from Burswood and followed the yellow brick road across the former golf course. I walked down the meandering path under the direct sunlight, and enjoyed the view of the vertical city skyline that acts as a counterpoint to the horizontal slice of the stadium. Somehow, the building sits comfortably in the landscape and the sprawling grass plains allow its bulk to be unobtrusive on the horizon. As details of the cladding come into focus, the inspiration of the Pilbara is obvious. Its colourful earth-toned strata is a subtle way to give the building a Western Australian identity.

The number of bus stops was impressive, however, there wasn’t a mass exodus to witness their effectiveness, so I’ll have to come again. It was great to see the number of people just having a look, and enjoying the new public space — drinking at the converted Golf Clubhouse overlooking the river (no longer members only club), grabbing an icecream from the truck on the bank, or simply cycling around.

The Arbour was the highlight. It is a semi-covered walkway that creates a link to the Swan River and represents Noongar Community stories. Inscriptions along the way tell stories in two languages and encourage cultural understanding. The gentle undulations

create a sense of movement that compels visitors to pass through from bridge to station whilst enjoying the journey.

Any sporting venue, and context, needs to pay consideration to movements of people en-masse. The risk is that, on off-days, these spaces can feel empty and cavernous. Optus stadium, however, manages to take full advantage of the riverside location. Ripples come from the circular footy pitch and create a landscape with human scaled spaces that work as a weekend cycling destination.

Once the bridge is finished, and the plants have some time to grow and be shady, I may add this to my river route. •

- 25 -

•

- 26 -

Optus Stadium by HASSELL, COX and HKS. Image: Fiona Giles.

Optus Stadium by HASSELL, COX and HKS. Image: Peter Bennetts.

- 27 -

Optus Stadium by HASSELL, COX and HKS. Image: Peter Bennetts.

Optus Stadium by HASSELL, COX and HKS. Image: Peter Bennetts.

- 28 -

Living Knowledge Stream. Image: Paul Verity at Syrinx Environmental.

the living knowledge stream

Author Pip Munckton & Rosie Halsmith

Bringing Curtin’s water story to the surface.

In recent years, universities have seen a new wave of landmark buildings, university greens and cultural facilities that aim to attract students, build profile, blur the edges and bring the outside — along with its beanbags and food trucks — into historically cloistered grounds. As student numbers continue to grow, institutions are certainly seeing the value in place making, but what does it mean for a campus to truly be connected to its place?

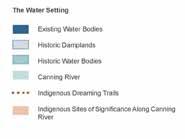

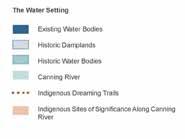

The future vision for the Curtin University campus in Bentley, Perth is driven by Greater Curtin — a plan for an expanded and renewed campus and activity hub. Following the 2013 Greater Curtin Master Plan, Syrinx Environmental, Dr Noel Nannup, and cultural engagement consultants Sync 7 were engaged to build upon one of the central ideas, that of a living stream network through the site.

In its current iteration, the vision for the Living Knowledge Stream is a greenblue infrastructure and indigenous cultural trail network, underpinned by the path of local Songlines and water movement across the future Curtin site. Each Songline (or dreaming trail) is rich and expansive in cultural meaning. The Kujal Kela (Twin Dolphin) tells a story about linkage and unbroken connections to ancestral land and the river through cycles of change, and Djiridji (Zamia) trails tell the story of

seasonal journeys from river to hills and the abundance of food and water. It is not a built outcome; rather, it is a site-specific, research-based strategy and guideline for the design of the public realm.

As practitioners in the built environment we have a responsibility to work together with the traditional owners of the land. In the case of the Living Knowledge Stream the strategy is grounded by the layering of traditional ecological knowledge, mainstream science and design. A conversation between team members brought sacred places to the forefront, as well as invisible water flows, long forgotten by many.

The team, under the guidance of respected Whadjuk Noongar Elder Dr Noel Nannup, mapped two local Songlines that run through the Greater Curtin site. These paths follow both underground and overland water flows — a petrified tributary, or paleochannel of the Canning River and a historical chain of wetlands. These Songlines become structural threads that tie the Living Knowledge Stream framework together, the end result being a network of green-blue infrastructure across the Greater Curtin site — a landscape of ephemeral wetlands and swales. Distinct endemic planting and material palettes represent places and paths of cultural significance, history and the invisible ecological layers of the site. The idea is

that designers will refer to the Living Knowledge Stream guide as a key resource for future works in the Greater Curtin public realm.

In aiming for a whole-of-campus vision, collaboration appears as the crucial element to unearthing a true and complex understanding of the Greater Curtin site. Syrinx Environmental, Dr Noel Nannup and Sync 7 have together uncovered layers of cultural and ecological significance, creating a strategy that is grounded in its place. The success of this project, however, will depend on further conversation and collaboration. With careful management of future phases, there is potential for the significance of the Greater Curtin site to be brought to the surface.

This strategy offers a new perspective on the values that might instil a sense of campus identity and create value for students and university communities in coming years. Rather than a one-off event or a shiny new building, a wholeof-campus infrastructure can increase ecosystem services, bring cultural layers to the forefront, provide a platform for education and ultimately enhance the student and community experience — all while acknowledging the stories of the landscape. With change comes opportunity and a chance for universities to consider their landscapes as an asset — to consider what truly makes their place unique. •

- 29 -

- 30 -

Dampier Community Hub by Gresley Abas Architects. Image: Acorn Photo.

north west community buildings

Author Phil Gresley & Clancy White

The Architect talked to Phil Gresley and Clancy White about their experiences as architects for community buildings in the North West — the Dampier Community Hub (Gresley Abas) and Youth Involvement Centre (YIC) in South Hedland (Whitehaus).

Designing with clients and responding to place

Phil Gresley: Consultation is where the seed of a community project is planted, where things grow. If architects really listen, then the community gets ownership of the project. Architects also gain the opportunity to share their knowledge — and this is not just in the North West.

Clancy White: I think you’re right, the process is really important. It’s easy to have expectations of what the client wants before you go in, but I’ve arrived at project consultations up north expecting to be going in one direction, and come out of that process realising we will be going somewhere completely different.

PG: It can be interesting when a client is connected to a community group, or groups, and they all might want different things. I’ve found myself in the situation where you need to bring quite disparate opinions together…

CW: That has been my experience too. Say local or state government, or a mining company, is paying for the project. A community group, or fifteen

community groups, will actually use it and sometimes not all those ideas for the project align. Luckily, in our Port Hedland project this was not an issue.

PG: Delivering on community expectations is about providing good quality, functional, comfortable space. For the Dampier Community Hub, they needed an early learning centre, library, and multipurpose spaces. So, we’d talk to all the different groups — sports groups, yoga, arts and crafts, and the like. And because the City was to manage the venue timetabling, we’d work with them to understand how to best group those activities, and then we’d wrap space around those categories. We tested our design by imagining there’s a new group, or there’s an event that needs a large space.

It’s not rocket science, it’s part of the briefing process. You make sure everyone knows they’ve been listened to by providing what they’re asking for.

CW: The YIC project was for at-risk youth, and the briefing and planning was particularly complicated on that project. There’s a childcare centre for kids under five, a teenager’s drop in space, and an adult training centre. These three completely different user groups are all thrown together — we found that the building could help control the flows of people. It was important to avoid young adults getting mixed together with infants when they are socialising and learning.

After our initial chat with YIC, and some youth representatives there was a lot of back and forth. We’d be asking each other, “How will this work on a typical day?” Because it was such a massive expansion for their facility we had some unknown territory. Sometimes the answer was, “We’re definitely going to need this space, but we don’t exactly know how we’re going to use it until we move in.”

CW: Some of these bigger Pilbara towns have already carried out larger strategic visions, which makes it easy to slot into. The whole community is already thinking into the future, and being part of the bigger plan.

PG: We found the City of Karratha to be a really sophisticated client. They’ve become that way because of the amount of community development in the Pilbara over the past 10 years. They’ve upskilled to deal with it. We appreciated working with people who understand how to get something done.

PG: The Pilbara vernacular handbook that Landcorp developed has done a lot of that work. It helps in understanding what people in the North West are wanting to achieve with the new architecture. They’re trying to build cities, and build community.

Building for climate: the extremes and the everyday

PG: Before reverse cycle airconditioning became ubiquitous,

- 31 -

•

architecture in the Pilbara was working hard to manage the climate through passive solar design. The Port Hedland TAFE campus, the Dampier Salt building, the old High School at Wickham, are examples of buildings that were managing people’s comfort through simple architectural design techniques to achieve really good outcomes.

And then, in the 80s with the introduction of air conditioning, that all went wrong. It became acceptable to just build a box with a big airconditioner and to have it on 24hrs a day, 365 days a year. There is so much lost in terms of architectural opportunity when a building is just a box. We lost all the large shaded outside spaces that let the breezes come through and could achieve a temperate drop of 6 or 7 degrees.

I remember a great moment on the Dampier Community Hub when construction was nearly finished, a couple of the workers were laying in the shade at lunch time having a bit of nap — Outside! They could have been inside in the air-conditioning. It was 36 degrees that day, but they were outside,

laying there letting the breeze come through. At that moment, I knew we had achieved some success.

CW: We design buildings in a way that is going to be relatively straightforward to build. For example, a detail for a roof in the Pilbara involved carefully wrapping a roof truss with insulation. It was a really important part of how we were managing the condensation for the building — it absolutely had to work. So, we stopped and thought about it. Is someone crawling around in a roof, in probably 50-60 degrees, really going to make sure that this thing is done properly? Probably not. Alright, let’s start again. We need something easy because if it doesn’t go in right it’s going to be an ongoing issue.

PG: We used brick for the external walls of the Dampier Community Hub to bring a comfortable module to the experience of the users, something of a small scale in a place of enormous objects and infinite landscapes. Brick is not that unusual in the Pilbara, but not common. We found out that a single layer of brick does not meet the new cyclone codes for object penetration.

CW: Yeah, that’s always a big concern.

PG: We ended up out at Curtin University with one of the brick suppliers and the city of Karratha to carry out the cyclone testing.

CW: They’ve got the cannon that shoots a steel ball and it will just punch a hole straight through a brick wall.

PG: It’s counter intuitive and concerning if buildings are being constructed without taking the performance of brickwork into account. Working up north you’ve got a lot of issues like this to consider — the climate, the place, transporting the material. You’ve got the heat, the wind, cyclones, storm surge and water.

CW: We had a recent discussion with an engineer about designing for a 1 in 2,000 year storm event up there. And I’m saying, “That is literally a storm of biblical proportions! Do we really have to design the building for that?”

PG: But you know you do, because when it rains, it really rains. It’s phenomenal. It’s like nothing down here. •

- 32 -

- 33 -

Dampier Community Hub by Gresley Abas Architects. Image: Acorn Photo.

Youth Involvement Centre by Whitehaus. Image: Clancy White.

- 34 -

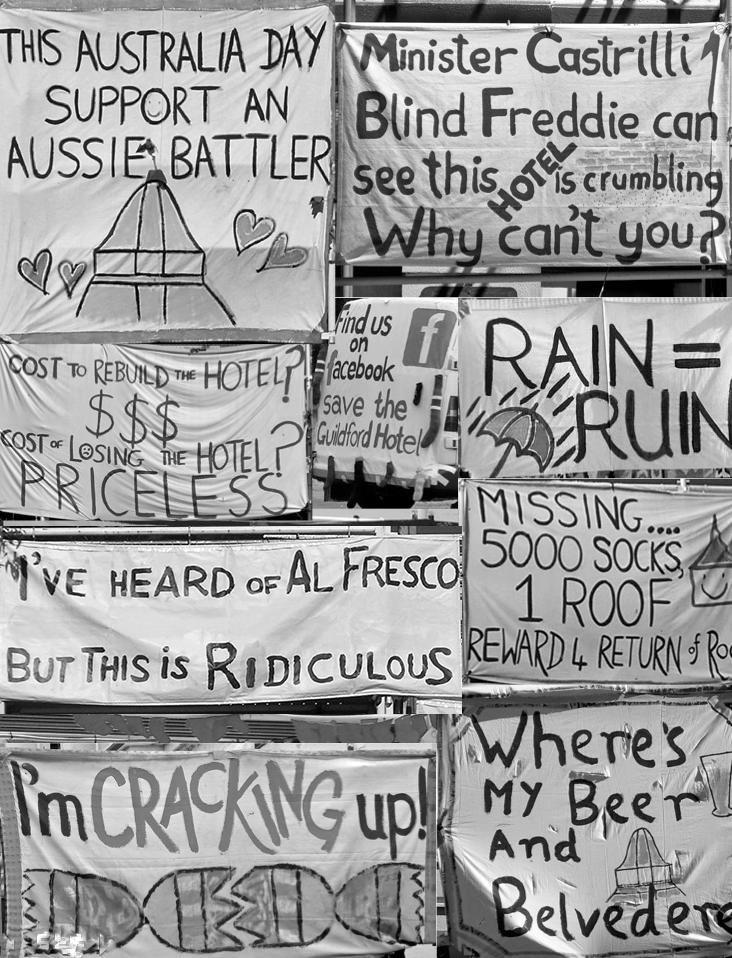

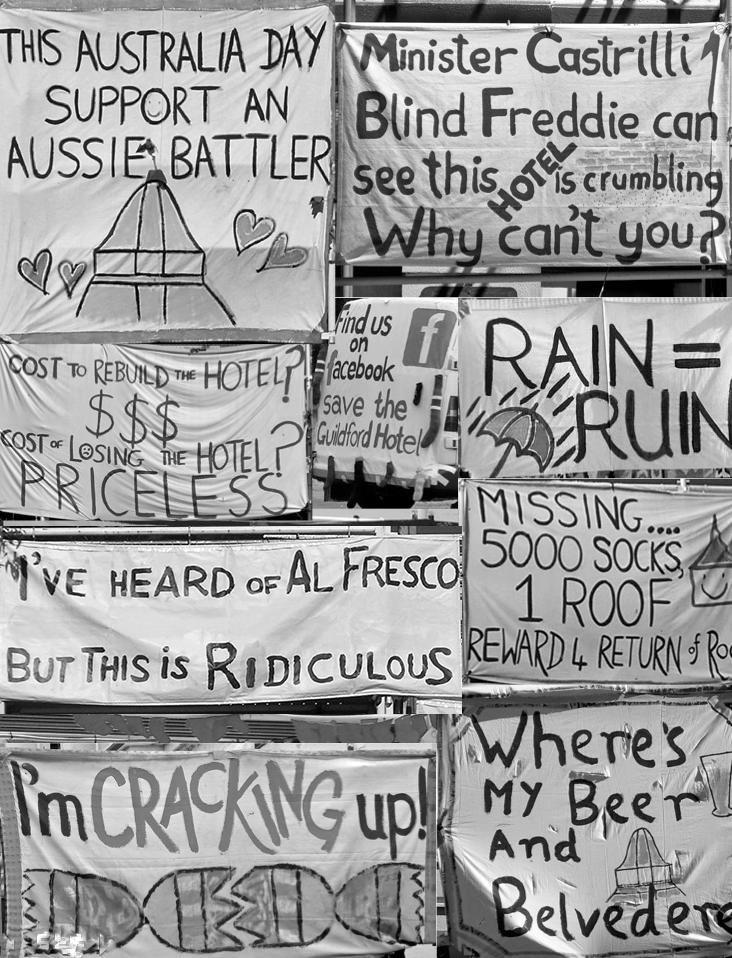

Protest signs. Image: Fratelle Group.

conversations on heritage

Author Kylee Schoonens & Eddie Marcus

One Thursday afternoon at the Guildford Hotel, The Architect Magazine met with Kylee Schoonens and Eddie Marcus to talk heritage architecture.

Background

Kylee Schoonens: After the fire in October 2008, although the owner received a Development Approval they did not have a tenant to take over running the hotel. With building use uncertain, the project went into a holding pattern until Fratelle Group came on board in 2013. Fratelle’s motto is ‘connect to create’ connecting people to get projects across the line. We identified the Publican Group who came over from the East Coast, embraced our vision and became the eventual tenants in 2014.

After the fire there had been quite a lot of community angst and anger due to the roof remaining off, and the building staying in a state of exposure for seven years. There was a lot of protest socks tied to the hoarding and protest signs — all trying to get the owners to act.

We engaged with the Heritage Council from the outset. They initially wanted all the cornicing and ceilings to go back in, and to bring back the plasterboard and period features.

Eddie Marcus : But which period?

KS: Well, that's the thing. The original hotel was built in July 1885, with an extension in 1914.

EM: It's a typical story of a hotel extension, done for the same reason that anybody spends money — they were forced to by government! Liquor licencing wouldn't renew the license in 1914 until they met code. Liquor licenses are useful tools for historians, which along with the call for tenders tell me the architects were Wright Powell and Cameron (still going as Cameron Chisholm Nicol). For James Wright it must have been one of his last projects as he died in 1917.

The Swan Brewery took over in 1929, implementing their standard bigchain look. ‘Period design’ could mean restoring it to this, or we could remove Wright’s frontage and restore it to its 1885 original red brick façade…

KS: That would never happen!

It was renovated in the 90’s. So, before the fire, it was faux-federation heritage — everything dark green and maroon. They had the dado rails and scotias as the period features! It was underutilised. The front façade suffered from severe concrete cancer so they installed steel columns. We managed to remove these, we took plaster casts of the original columns and rebuilt them. We received a heritage grant to restore the front façade and for the reinstatement of the belvedere (cupola). The Heritage Council was supportive as they wanted to see action. They brought ideas but our vision prevailed.

Plasterwork on the upper level suffered seven years of weather exposure and was coming off in sheets. We decided not to replace what fell off. Downstairs a lot of the stuff had been stolen, but as the staircase was lost in the fire, luckily the period features upstairs were almost all intact. Many single leaf walls had collapsed so, rather than rebuilding, we kept what we found. We were conscious to define what is new and what is old. For example, steel straps were required so we expressed them. We also stepped the ceiling away from the edge of the brickwork.

During demolition the builder retained everything. They had two shipping containers full of material for reuse — jarrah beams as benchtops, and the fire-warped steel from the belvedere and the staircases was used in light fixtures and installations.

The Belvedere

EM: In those days a belvedere was quite common, if you could afford it — you will find many more on plans than were actually built. Everybody designed belvederes, but during construction owners would cut back! There are several pubs in the CBD which should have had belvederes but never got them.

KS: That was one of the elements where the Heritage Council was adamant we be faithful to the original design. Watercolours from the 1914 renovation

- 35 -

•

The Guildford Hotel.

- 36 -

The Guildford Hotel by Fratelle Group. Image: Fratelle Group.

The Guildford Hotel by Fratelle Group. Image: SQUINT PHOTOGRAPHY.

showed the belvedere with a lookout access. We wanted to allow everyone to see the belvedere, so left the floor out to allow it to be experienced from the bar below. It was constructed in the rear car park and craned into place one Saturday morning — we had about 500 people come down to watch it! Everyone in the local area has a connection to the building, and quite an emotional connection as well. That's what I love about architecture.

EM: A cliché historian’s definition is: “Heritage is the awkward conjunction of history and memory.” A building embodies history, whereas human memory is flawed. You get all sorts of stories about places that can't possibly be true. It's what makes it heritage, but also what makes it incredibly difficult to work with as emotions can trump economic realities. Economically it was possible this place would be demolished, or it could have had a five-storey block of flats out the back.

KS: …We have designed that 5 storey block of flats! The hotel's viability does indeed need it.

Respectful design

EM: Heritage buildings are not just buildings. They are connected to the community and sometimes, they are buildings heritage architects just love! Respect for a building is a difficult term to implement. In Perth you often end up with facile ‘façadism’. Don't change it too much on the front, but gut everything else.

Restoration, renovation — everything except preservation — is creating a story as much as it is telling a story; it is a decision by the architect and developer to compromise between commercial necessity and what's there. If you want to go ‘full respect’, take out your modern bar and refrigerators because that's what it would have been like in 1915! Not viable today. No one wants to drink warm beer in a non-airconditioned room...

KS: and you probably wouldn't get your liquor licence either!

EM: There is not infinite flexibility to be respectful, but you can develop an outcome which people agree works as heritage, which is why keeping the community on side is a good idea. Respect for fabric can be not ripping down more than you have to, but sometimes you cannot avoid this in order to meet the commercial necessity required to reactivate a space. It's a compromise.

KS: Yes, exactly. We haven't recreated a chapter, we've created a new chapter. Downstairs, where we needed to cut holes in walls, we restricted the opening height up to three metres and put in a steel beam to express it.

We needed to make it a modern-day facility, so the new bar cuts through an original dining room and staircase. We've moved the stair to make it flow. There are also new elements in the place of existing elements to reduce the impact on the building.

EM: Creating a new narrative rather

than grabbing a period in history and trying to replicate it.

KS: If you are copying the heritage then you are not respecting it.

EM: The core principles are: retain as much as you can and do not introduce new openings or entrances where possible on key façades. Respect is not very scientific. But we can ask, does it work as a heritage building? In this case yes it does. Would James Wright recognise it? He'd probably say, "What have you done with the space I designed? A lovely 1915 space, and you ruined it!"

KS: I'm going to have the ghost of James on my shoulder now! •

- 37 -

•

- 38 -

Ronnie Nights Bar by spaceagency. Image: Detail MC.

Ronnie Nights is the quirky new cousin of backstreet bar ‘Strange Company’. Sharing the same client group and architect, together they represent the beginnings of a network of venues envisaged by the proprietors for Fremantle. The offerings and audiences of these two venues must be distinct so they can complement, rather than compete with one another if the proposed collective is to succeed. Located at the bend in Fremantle’s ‘main drag’, Ronnie Nights sits in a row of retail at the gateway of the dining strip. Its open front attracts the foot traffic of locals, tourists and out-of-towners.

For the architects at spaceagency, the project represents a deliberate departure from the sophisticated, moody venues, such as Bread in Common in Fremantle and the Treasury Buildings in Perth, towards something more playful and thematic. Ronnie Nights is an eclectic bricolage of patterned surfaces, collected items and bold monochrome graphics that are craftily composed using a string of coloured insertions. It is a space that takes decorative clues from Fremantle’s sharehouse culture to recreate the fun loving familiarity of a Freo house party.

The building was previously occupied by Indian restaurant ‘Aunty G’ and, prior to that, another Indian restaurant ‘Maya’ whose single dining space spanned two shopfronts. The new bar counter is located along the intersection of these

ronnie nights

Author Kate Woodman

shopfronts, dissecting the space and making sense of the existing ceiling heights. This double sided, centrally located bar services all areas of the venue. Running perpendicular to the street, the theatre of drink preparation is visible to passersby. Within the venue, views across the bar connect and layer the space. Clever, focused lighting illuminates surfaces rather than spaces and the apparent effortlessness of this spatial planning and servicing belie the skill and budget required in its execution.

The street frontage has been retained and recomposed through the application of a couple of swift decorative forms. A powdercoated yellow portal with black and white tiling below and window film above denotes the understated entry. Behind the existing full height bifold doors, a simple steel pipe and coloured rope balustrade creates an open and connected street edge. This rope, sandwiched between mission brown mosaics, evokes nostalgic memories of 1980’s macrame.

The existing building and the planning strategies of the architects have resulted in four distinct but connected rooms, each with uniquely different volumes. The design exploits this diversity in spaces, applying a novel decorative approach to each.

Straight off the street you enter into a high and narrow space that links the

various rooms visually and physically. A heritage stair leading to the first floor lounge is visible overhead, a dipped in green ‘Garden Room’, complete with its own disco ball, is visible beyond the main space, and the warm glow of the street facing lounge can be seen across the bar to your left.

In the entry space the patterned surfaces of printed acoustic panel, the glossy black of pressed tin ceiling and the existing tiled floor lay backdrop to the bold graphic of terrazzo coloured in red, black and white. This enviable finish forms the rectilinear counter top of the bar as well as a standing bar that meanders along the entry wall.

The active pedestrian edge at the front and the hum of the kitchen at the rear bookend the venue. The adjoining ground floor lounge is a compressed space with uniform black walls and tangerine coloured cable tray. Throughout the venue a combination of purchased, collected and custom designed furniture sits amongst copious pot plants, retro nostalgia and family photos that were found on site.