Architecture of place

$14.90 Official Journal of the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter Print Post approved PP 100007205 • ISSN 1329-1254

Question today Imagine tomorrow Create for the future

For over 60 years, Irwinconsult built a reputation for pioneering complex solutions, guided by a design philosophy that responded to the architectural intent of a project. WSP is proud to continue this philosophy in helping our clients deliver iconic and complex projects across the built environment.

1. STATE LIBRARY VICTORIA: VISION 2020

Architectus and Schmidt Hammer Lassen

Image: Patrick Rodriguez

Disciplines: Structural, Civil, Building Services, ESD and Fire Safety

2. SHRINE OF REMEMBRANCE STAGES 1&2

ARM Architecture

Image: John Gollings

Disciplines: Structural, Building Services, ESD

3. PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA MEMBERS’ ANNEXE BUILDING

Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design

Image: John Gollings

Disciplines: Structural, Civil, Building Services, Waste Management and ESD

4. SOUTHERN PROGRAM ALLIANCE Cox and Rush\Wright Associates

Image: Courtesy Level Crossing Removal Project

Disciplines: Civil, Environment & Planning, Systems, Railway, Stakeholder Engagement, Project Management

5. NEW STUDENT PRECINCT, UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE, PARKVILLE VIC

Lyons Architecture in collaboration with Koning Eizenberg Architects (USA), ASPECT Studios, Breathe Architecture, NMBW Architecture Studio, Greenaway Architects, Glas Urban and Architects EAT

Render: Lyons

Disciplines: Structural and Civil

2 4 3

www.wsp.com 1

5 Melbourne Level 15, 28 Freshwater Place Southbank, VIC 3006 Australia t +61 3 9861 1111 melbourne@wsp.com Bendigo 133 McCrae Street Bendigo VIC 3550 t +61 3 5442 6333 AU.Bendigo@wsp.com

On the Cover Interpretation sketch of the Cradle Mountain Visitor Centre by Cumulus Studio, with the landscape arrival reflecting the multitude of endemic landscapes of the region, including buttongrass plains and temperate rainforests. Cover artwork by Eloyse McCall.

Art Direction

Annie Luo

Graphics Coordinator

Eloyse McCall

Printing Printgraphics

Acknowledgement of Country

The Victorian Chapter and Editorial Committee respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we work and pay respect to their Elders past, present and emerging.

With thanks to our Gold Patron Carey Lyon

This Publication is Copyright

No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the Australian Institiute of Architects Victorian Chapter.

Disclaimer

Readers are advised that opinions expressed in articles and in editorial content are those of their authors, not of the Australian Institute of Architects represented by its Victorian Chapter. Similarly, the Australian Institute of Architects makes no representation about the accuracy of statements or about the suitability or quality of goods and services advertised.

02 President’s message 05 Chapter news 10 Editorial 12 Feeling climate 18 After Warracknabeal 22 Designing in sensitive environments 26 Experience-based architecture 30 Place value 34 Exploring markets 36 Architecture as host 40 Office of the Victorian Government Architect 42 Slice 44 Profile Contents Managing Editor Simon Tengende Editorial Director Emma Adams Guest Editor Keith

Editorial Committee James Staughton (Chair) Elizabeth Campbell Laura Held Yvonne Meng

Mercuri

Noxon Sarah Lynn Rees

Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter Level 1, 41

St Melbourne,

ABN 72 000 023 012 Become a Patron vic@architecture.com.au 03 8620 3866 Advertise with Us vic@architecture.com.au 03 8620 3866 Subscriptions Four print issues per year (AUD) $60 Australia/NZ $85 Overseas

Westbrook

John

Justin

Keith Westbrook

Exhibition

VIC 3000

Architect

autumn

Victoria

2020

A rich architecture of place

Our understanding of place is inherently subjective. This subjectivity has resulted from many thousands of years of evolution, translations, histories, heritage, dreamtime and occupation. How we regard place and the ownership of this is contentious and is governed by actions, attitudes and economics.

This issue of Architect Victoria, guest edited by Keith Westbrook, begins to set out the varying conditions that impact and define place. What are the social conditions that result and how can we find more meaningful ways of understanding and responding to place?

With the recent summer fires that ravaged communities and wildlife, the conversation very quickly turned to our ability as a country to look to our First Nations People to lead and inform us as to how best to manage the land that we reside on.

A recognition of our ignorance and naivety when it comes to being reliant upon those who know, those who understand place and how it responds and evolves.

and regarding it as a condition associated with tabula rasa denies our ability to understand and comprehend the inherent social and civic responsibilities that underpin our capacity to provide for communities and to allow for these to prosper and be vibrant. As architects we carry this responsibility. It is important that we continually seek ways to drive this agenda and ensure that what we build stands ethically tall.

Amy Muir

Our recent super forum that brought together the Victorian Chapter’s sustainable architecture, small, medium, large and regional practice forums tackled the issue of climate action. How we as individuals and as a collective can achieve very real, incremental change. With contributions from Jeremy McLeod (Breathe Architecture), Craig Harris (Low Impact Development), Stefan Preuss (OVGA), Professor Peter Newton (Cooperative Research Centre for Low Carbon Living), Davina Rooney (Green Building Council of Australia), Nadine Samaha (Level AK), Jacinda Sadler (Sadler Architects) and David Wagner (Atelier Wager), it is evident that complacency will no longer be tolerated so let’s get on with assisting change.

Longevity is key to understanding the principles that drive the need for climate action. The building of place is essential in supporting and underpinning a sustainable future. Ignoring place

I would like to thank Keith Westbrook and the considered reflections provided by the various contributing voices for this edition. It is a layered and nuanced topic. I would also like to acknowledge the very important role this publication plays. As architects we are trained to think laterally, to question, understand and challenge. This often leads to an industry that is made up of a variety of views, insights and convictions which have been informed by education, peers, mentors and the places that we have experienced and worked within. This is what makes for rich and diverse conversations. This is to be celebrated, and this publication provides the very forum for this to occur. Thank you to Emma Adams for her detailed oversight, the Editorial Committee James Staughton (Chair), Elizabeth Campbell, Laura Held, Yvonne Meng, John Mercuri, Justin Noxon, Sarah Lynn Rees and Keith Westbrook for continually pushing for relevant agendas, past and present guest editors and contributors, and Carey Lyon for his generous support as patron.

As we stand amid an evolving pandemic and the lasting impact that these conditions impose on our society as a whole, we cannot forget about those who have been impacted by the summer fires. Reaching out and reminding people that you are there is imperative. Over the coming months we will provide you with updates regarding the provision of additional support at a state and national level. Wishing you all a safe 2020.

Victorian Chapter President

President’s message

architecture.com.au Membership 2020 Shape your profession Join a global network of over 11,500 professionals, committed to raising design standards and advocating on behalf of the profession for all Australians. The knowledge, advocacy and tools you need to shape your world. Shape your world

Architect Victoria 46 Supporting post-fire design and rebuild programs across Australia. Donate today foundation.architecture.com.au/donate

Victorian Chapter

Earlier this year I'm sure no-one would have picked up how much the COVID-19 virus would play havoc with our way of life, including social, cultural and professional activities. As most of us settle into working from home or remotely, I hope that this edition of Architect Victoria provides you with some literary respite from what’s currently happening. While we continue to monitor this space, it is clear that there are still multiple opportunities for the profession to engage in meaningful discussion and action. This was evident at the well-attended Climate Action Forum supported by RMIT University in Melbourne with all proceeds going to Architects Donate— our national campaign to support post-fire design and rebuild programs across Australia. This was balanced by the Pro Bono CPD event, which focused on the fantastic work being done by Architects without Frontiers. With many planned events now suspended or cancelled, I encourage our members and readers

Practice of Architecture Committee

Matt Gibson

Over 2019 the committee said goodbye to Hayley Franklin, Megan Dwyer and Con Moschoyiannis, thank you very much for your contributions. A special thank you to Hayley for her significant and long serving contribution as National Practice Committee (NPC) representative for four years. The Victorian practice committee welcomed Ian Briggs (Chapter Council), Regina Bron (Building Regulations Advisory Committee) and Aimee Goodwin (Small Practice Forum) from the early part of 2019.

It was a year with many of-the-moment issues to deal with along with the regular tasks – that of collating and identifying practice issues for elevation to the National Practice Committee or for the writing, reviewing or briefing of Acumen notes. 2019 started in earnest with a meeting to review the Lacrosse finding and followed throughout the year with extraordinary meetings with the Chapter President, CEO, Planned Cover and the Architects Registration Board of Victoria (ARBV) to work through issues surrounding Professional Indemnity Insurance, Ministerial Orders and the changing nature of the built environment and what it means for practitioners.

Thank you to Karen McWilliam for once again drafting several briefing notes on topics such as mental health, student commissions and novation, and to

to continually seek up-to-date information from the Chapter through our website.

Finally, I’d like to acknowledge Chapter President, Amy Muir, for her efforts over the past two years. Amy has worked tirelessly to advocate on behalf of the profession. Joining us on the Victorian Chapter Council in 2020 are Nadine Samaha, David Wagner, Sophie Cleland, Jeremy Schluter, Aimee Goodwin, Daniel Moore and Tom Huntingford. I am pleased to be working with you all. We also thank outgoing Chapter Councillors, Vanessa Bird, Ian Briggs, Rosemary Burne, Jocelyn Chiew, Daniel Soetjahjono, Camilla Tierney and Keith Westbrook. Congratulations to Keith, who has been selected to join the 2020 Australian Institute of Architects Dulux Study Tour, and Jocelyn on your appointment to National Council.

Daniel Moore for his briefing note on electronic communications – all of which led to becoming published Acumen notes. Thanks to Bruce Allen for his consistent conversations with the ARBV on critical insurance matters.

Throughout 2019 the practice committee worked closely with the small, medium and large practice forums to amplify current topics and disseminate information quickly via Odd Spots in Vmail. Bank loan and ABIC issues are continuing to be reviewed by Warwick Mihaly and Aimee Goodwin. Thank you to Ian Briggs who attended all recent NPC meetings and to David Sainsbury for his ongoing expertise. At the start of 2020 we say goodbye to Daniel Moore (as our Emerging Architects and Graduates Network representative) thank you, and welcome Charlotte Churchill.

Architect Victoria

Chapter news

Victorian Executive Director Simon Tengende

Sustainable Architecture Forum

Nadine Samaha

Toner and I attended as sustainable architecture delegates for the Institute. Passionate speakers urged a just transition to a low-carbon future and a full-scale response to the climate emergency.

brought architects face to face with people interested in increasing the sustainable performance of their projects.

The 2020 Sustainability Living Festival's program of events brought together leaders and citizens seeking real action on the climate change and biodiversity emergencies. Jane

Student Organised Network for Architecture

Tom Huntingford

The Institute's Sustainable Architecture Forum ran three events on the climate emergency theme. Neville Cowland and Jacinda Sadler shared insights into how they design to reduce climate and environmental impacts. Jane Toner and I detailed principles and strategies for aligning the built environment with nature. The final event, Ask an Architect Anything about Climate Action,

Victorian Chapter member forums organised the Climate Action Forum, supported by RMIT. Attended by architects and academics, the forum highlighted the need for immediate collective action. Many architects recently expressed interest in starting a new working group in our forum. We welcome new members and ecourage everyone to become involved. Meetings and events are shared through Victorian Chapter media channels.

At the commencement of semester in 2020 there are many exiting initiatives and opportunities. The discussion board established by the SONA committee for the Melbourne School of Design in mid-2019 is continuing to grow with over 600 members at the time of writing. The board has expanded the scope of its operations by bringing other faculty-associated

Awards Committee

Ingrid Bakker

The 2020 Awards season is well underway with Victoria receiving

student clubs into the fold. Moving forward the group will be jointly coordinated by a committee made up of executive teams from each of the Architecture Building and Planning student clubs with the intention that it becomes a one-stop-shop for students to connect and hear about events happening around Melbourne. The continued development of the board creates a significant opportunity for student culture at the University of Melbourne as student clubs have not collaborated on a mutually beneficial project such as this in recent history. The hope over the coming semester and year is that this collaboration will begin to germinate an active and cooperative culture between the student clubs, their committees and members.

Furthermore, SONA is intending to foster cross-institutional collaboration through events such as the proposed Super-crits. Inspired by the thriving culture that exists between the London architecture schools, the Super-crits are intended as large-scale presentations by students from the various architecture faculties at Victorian universities on how their work relates to a given theme. They will then receive feedback from a collected group of practitioners and tutors. These are just two of the initiatives that SONA will be seeking to further this year and will compliment a plethora of official events run by SONA Victoria making for a busy and exciting year ahead.

235 entries. Presentations to Juries was to take place as part of the Melbourne Design Week program at RMIT Design Hub in the city. And while the event was suspended due to growing concerns around COVID-19 and in particular social distancing, the Victorian Chapter is commited to run the 2020 Awards with a format that will navigate the current restrictions and keep members safe,

while maintaining the integrity of the National Architecture Awards program. We would like to thank all 2020 entrants for their understanding and patience during this time.

Congratulations on your extraordinary efforts to date. We wish you all the best for the duration of the program.

of place

Architecture

Chapter news

Victorian Architecture Awards —2020

Check for updated information on the 2020 awards at architecture.com.au/awards

Architect Victoria

Emerging Architects and Graduates Network

Gumji Kang

up for our packed calendar once again. Look out for intros on our @emagnvic Instagram page! I'd also like to say a huge thank you to Camilla Tierney, who has stepped down from her co-Chair role, for her years of contribution. We will soon be releasing more information on our ever-popular podcast, Hearing Architecture, CPD programs curated for graduates, forums and other exciting collaborative projects, so tune in to our social media for more information.

are all ears to any ideas that we could support and provide advocacy for. We look forward to making more positive contributions within our community and also support our members across the state. As always, please reach out to us at emagnvic@ architecture.com.au or our social media networks.

EmAGN is off to a flying start with the new decade. We have welcomed fresh faces for incoming committee members for 2020 and started gearing

Medium Practice Forum

Matt Gibson

In 2020, we continue to support other committees across the Institute, with our involvement in CPD, education, research in practice and Chapter Council, and also open our arms to other Institute partners. We

The Medium Practice Forum convened through 2019 to discuss diverse topics and several real-time issues as they developed through what was a hectic year for the architecture and building industry. Contract administration forums were led by James Staughton (Workshop Architecture) and David Wagner (Atelier Wagner) in March covering current topics such as the refusal of many banks to approve construction loans for architectadministered contracts, deposits within contracts now required under recent ABIC changes, contract administration fee methods, contingency and general quality control.

In May a second forum on contract administration was led by Mel Bright (Studio Bright) and Jonathon Boucher (BE Architecture) looking at methods for efficient process, the managing of resource time, special conditions of ABIC, handover and defects, and builders and social media. July saw Simon Knott (BKK) and myself (MGAD) talk about dispute resolution. What the best methods are to prevent disputes and where unavoidable what options are available to architects.

In September Tristan Wong (SJB) and Brett Nixon (NTF) discussed Human Resources management and office culture – creation of the right office culture, staff reviews, employee contracts, professional development and empowering and maintaining great staff.

In November a combined forum was held at the request of the Victorian Chapter with small, medium and large practice forums attending to talk about the plight of the building industry in light of the recent VCAT rulings and Ministerial Orders with relation to Professional Indemnity

Insurance. Amy Muir (Chapter President) and Tim Leslie (Large Practice Forum) provided insight into how the Institute was progressing with a new Code of Novation and how it was advocating for regulatory reform. A large thank you to David Wagner, Jon Boucher and Albert Mo whom together managed the Medium Practice Forum throughout 2019 and will continue to do so in 2020. The first topic for 2020 will be reporting back on the Financial Benchmarking Survey carried out in late 2019. The Small Practice Forum have co-ordinated a similar questionnaire and will combine with the Medium Practice Forum to provide detailed and real information back (to practices who participate) on the state of the architectural industry. This will illuminate current trends on how practices perform including operational aspects and methods and how practices set themselves up financially.

Architecture of place

08—09 Chapter news

Local context

Words by Kim Irons

Kim Irons is Chair of the Victorian Chapter's Regional Practice Forum. Kim was invited to provide an extended report and looks at how architects working in regional areas could be supported through engagement with city-based practices, particularly with rebuilding work, which in turn could further enhance economic and social sustainability.

It is opportune that this edition of Architect Victoria focuses on regional tourism. While tourism contributes to the broader tourist dollar from international visitors, its direct impact on the economy of a local place can be hit and miss depending on the type of travel. As highlighted by many in Port Campbell, for instance, with few of the tour operators stopping in local towns, instead their passing dollar is absorbed by the larger tourist suppliers and destinations. Not dissimilar to the cruise ship phenomena of Venice and other cities. Cultural tourism has been recognised as a growing influence with visitors seeking cultural immersion,

something reflective of the heritage of the place. However, much of our regional architecture associated with these destinations and tourist attractions are typically designed by architects from outside the region, often city-based, offering a fresh perspective and objective eye. We know for the most part they are exemplars of high quality architecture responsive to place. However, does this miss the opportunity to embed an architecture with potentially more intimate knowledge of local place and community? If we supported use of regional architects or, at the very least, supported partnerships between citybased and local practices, could we start to see an even richer architecture of place?

Is this also our architectural version of passing cruise ships or could the engagement of regional practices also contribute to the social and economic sustainability of place? This seems even more relevant following extensive loss of landscape and properties in the recent bushfires. Governments have advocated the use of local builders and suppliers to

encourage local employment and a sustained economy.

While the overwhelming generosity of architects to pro bono services to assist with recovery has been positive, do we need to review what this might look like? Some architects in these areas have been directly impacted by the loss of their own properties. Should our pro bono services be offered directly to those who have lost property or would we be better to contribute pro bono services through our colleagues in those areas? The collaboration of local architects on Ballarat Open House provides a useful example, celebrating local design. This could enhance contributions to local economy and culture. We recognise that the increase of architects with extensive experience outside capital cities is directly commensurate with the increase in population and tourism growth in regional Australia. Regional forums meet regularly to discuss design, practice and procurement in their areas and also provide representation of the profession and a collective voice to local issues.

Architect Victoria

Architecture of place

Words by Keith Westbrook

Over the last few months we have witnessed many regional areas impacted by bushfires; the destruction of buildings, flora and fauna with thick smoke blanketing many other parts of the state. Regional communities rely heavily on visitors to support jobs and local economy, so much so that the premier has announced a program for over 115 major organisations to hold multi-day stays in affected areas – to attract visitors back to these regions.1 And while more will need to be done to combat the impacts of COVID-19, it does highlight the importance of tourism in Victoria and the infrastructure and architecture that supports it.

Travelling locally and globally, it’s clear that there is a relationship between tourism and architecture.

The two have been interrelated for centuries from pilgrimages to temples, to the era of the grand tours. What was once an educational rite of passage has now evolved beyond education into a leisure activity. There is a perception that tourism architecture is all about the image of architecture, and while that’s true to some degree, it’s not necessarily the key driver of these projects.

The major impact Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum had

on the small city of Bilbao in Spain is ‘a phenomenon whereby cultural investment plus showy architecture is supposed to equal economic uplift for cities down on their luck.’2 Today, tourism has arguably moved beyond this, with examples such as MONA museum in Tasmania demonstrating benefit to whole local economy while providing a truly evolving and unique experience to bring visitors back for more and more. In these instances, architecture has played a major role in the attraction's success, either as an attractor (the object of tourism) or as the container to house, heighten and orchestrate experiences. Research suggests that ‘visitors seek an authentic experience and wish to be “immersed” in the place they are visiting’3, so in these facilities which engage with history, culture, landscape and ecology as primary design requirements, how can the profession engage in creating architecture which is of its place and not purely an architectural attraction for mass consumption?

In this issue of Architect Victoria, expert contributors explore cultural tourism and how architecture can shape and heighten authentic visitor experiences. The responses cover a range of viewpoints, from Architecture

designing in sensitive environments, through to notions of presence and authenticity.

Kerstin Thompson's article explores the positive transformation of sites as well as the intricacies of designing in places with significant existing cultural, architectural and heritage value. One of KTA’s projects, Riversdale, lies between both flood zones and areas affected by the recent bushfires, bringing into question if there is an opportunity for a new type of bushfire eco-tourism to educate on the impacts of fire and the subsequent regeneration of the environment.

Focusing on regional western Victoria, Tom Morgan, Charity Edwards and Jason Crow from Monash University’s Department of Art, Design and Architecture uncover the true story of the abandoned silos and the paradox of the visual representation of a bygone era of agriculture versus the reality of a booming industry. Through this lens they discuss the transformational project, After Warracknebeal, focusing on the community-led evolution of a small town in the Wimmera.

Across Bass Strait, almost 20 per cent of Tasmania’s land mass is designated as the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, one of the last temperate wildernesses in the world. Peter Walker from Cumulus Studio discusses sustainable tourism in relation to several of the practice's well-known projects situated nearby and within these World Heritage areas. He investigates how architects can respect and contribute to the protection of significant natural sites. Adrian FitzGerald, also discusses sensitive environments, looking at the cultural tourism work of Denton Corker Marshall (DCM) from Stonehenge in the UK, and the Australian Pavilion in Venice, through to current projects in Victoria. DCM aim to enhance the special identity of a place through one of three approaches: subsume into the landform, tread lightly, or boldly contrast with the landscape.

Editorial

of Place

With a focus on Victorian projects, Scott Balmforth from TERRIOR examines the role of architecture within the tourism economy and their approach to designing location-based experiences that are created upon cultural, spatial and ecological understandings of each place, as opposed to an iconic architecture driven by form.

Elizabeth Campbell considers the intersection between the urban, architectural and natural environments, and how people interact with these junctions. Her article explores the history of market buildings with a focus on South Melbourne Market as both tourist attraction and a reflection of local culture, heritage and geography.

In the final article, Gregory Burgess questions why architects focus on the image of architecture. He recounts and reflects upon memories of being present and asks if we can improve the responsiveness of architecture though our own experiences. Gregory has a collaborative approach to designing buildings that engages with local culture, community and Country. Architecture plays a big role in tourism; shaping the visitor’s experience and perception of place, and when designed well, benefits the local community in which it is embedded.

Keith Westbrook is a registered architect and director of Cumulus Studio. During his 13 years of industry experience, Keith has primarily focused on bespoke architectural projects in the public realm. He currently runs Cumulus Studio’s Victorian office where the practice continues to develop their portfolio of cultural tourism projects. He has been a juror for the Victorian Architecture Awards and a sessional lecturer and guest reviewer at Monash University. He is currently a member of the Architect Victoria Editorial Committee and outgoing Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Chapter Councillor.

Notes

1 www.premier.vic.gov.au/business-sport-back-new-driveto-support-fire-affected-communities/

2 Rowan Moore (2017), the Guardian www.theguardian. com/artanddesign/2017/oct/01/bilbao-effect-frank-gehryguggenheim-global-craze

3 Kim Lehman, Mark Wickham, and Dirk Reiser, 'Modelling the Government/Cultural Tourism Marketing Interface', Tourism Planning and Development 14, no. 4 (2017): 467-482.

Architect Victoria

‘how can the profession engage in creating architecture which is of its place and not purely an architectural attraction for mass consumption?’

10—11

Feeling climate

Words by Kerstin Thompson

Can the architecture of tourism ever be anything other than parasitic when the basis for the touristic experience is the site's pre-existing value and interest? Some of our tourism projects have used architecture as a means to kick off a transformation – ecological, economic, social – in situations where the status quo is somehow wanting or in need of repair. For instance, our visitor centre for the Australian Garden at the Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne was part of a broader initiative to regenerate a former sand mine for future generations as a botanical garden celebrating the variety and splendour of Australian natives. In this scenario, upon its completion the debate centred around whether the architecture complimented, or not, the future landscape of merit, not whether it had devalued an existing one.

More problematic are commissions for tourism projects which occupy sites of considerable existing value. Here, the key challenge for architecture is how not to undermine the very attribute most valued and therefore central to the visitor experience. In other words, how not to kill the host.

The Riversdale Masterplan for the Bundanon Trust is an example of this exact conundrum. A site with the big three exceptionals in cultural tourism – cultural, architectural and environmental heritage – its value for visitors is underpinned by the Boyd family’s artistic legacy, the renowned architecture of the BEC building by Murcutt Lewin Lark and a remarkable landscape.

The primary mission of the Bundanon Trust is the appreciation of art and environment and the protection of its cultural and environmental heritage. The Masterplan we undertook with Wraight Associates, Atelier Ten and Craig Burton in 2017 (about to start construction) outlines the built form, supporting infrastructure, landscape and vegetation management strategy required to expand Riversdale’s facilities. This expansion will enable Bundanon Trust to extend its public programs in arts and education; increase general visitation especially by opening up the significant art collection to the public through a gallery; accommodate a greater range and scale of events and continue to manage and repair the broader site ecology.

Acknowledging the sensitivities and complexities around this next stage of development at Riversdale, the new works will accommodate increased visitation in ways that preserve the estate’s most cherished qualities, particularly its experience as a remote cultural retreat and its ecological, artistic and cultural history. There have been at least six significant periods in the evolution of these lands. These include Aboriginal occupation as part of the Dharawal Nation, Yuin people and Wodi Wodi Clan groups and then through European settlement marked by land grants and stock routes, rural estates and improved estates. On a site that has already undergone several rounds of buildings, the additional visitor facilities will be part of the latest period which encompasses the Boyd Estates to the present Bundanon Trust: the subterranean Arthur Boyd Gallery and Collection Store and the Bridge – collocated adjacent to the historic Boyd cluster to achieve a centralised heart united by a common forecourt.

Pivotal to the new visitor experience will be the invitation to compare through the architecture, Boyd’s imaginary landscape with the actual one around them, to continue the established conversation between art and environment. The tension and interplay between the natural and imagined, indigenous and exotic landscape appealed to Boyd and was fundamental to his vision. →

→ Right Shoalhaven River with Rose, Burning Book and Aeroplane (1981) by Arthur Boyd. Arthur Boyd’s work reproduced with the permission of Bundanon Trust

→ Next page Riversdale Masterplan for the Bundanon Trust by Kerstin Thompson Architects. Dharawal Country

Architecture of place

Article

12—13

This offered us much to draw upon in framing Riversdale's future. For example, sited to highlight the contrast of clearing to bush, proportions of windows and their placement to capture Arthur Boyd’s favourite views, breathing interiors sympathetic to the painting practice en plein air (painting outdoors).

Further, this rare conflation of inspiration (source) and reception (place) motivated an architecture that is both attractor and container: an attractor that adds another chapter to the legacy of the BEC building by Murcutt Lewin Lark and a container for accommodating the activities central to the Trust’s mission.

Boyd’s Shoalhaven paintings are of course powerful visual renderings of the Shoalhaven landscape. The new works at Riversdale will supplement this painterly understanding with a systems-based, ecological one. A vast network of river systems, in-tact bush and productive farming, this is a dynamic landscape in which different cycles work in parallel – hour, day, season, millennia, extreme periods of fire and flood – and inevitably reveal signs of its evolution, and the various forces that continue to shape it. Beyond a scenographic appraisal of the site’s beauty, the integrated design of buildings, landscapes and site

infrastructure will forge an authentic visitor experience structured around an environmental continuum that extends well beyond the official site boundary.

While the architecture of both the gallery and the bridge is at once dramatic and subtle, spectacular and performative, assertive and deferential, their moderation of climate is radically different according to function. The Arthur Boyd Gallery and Collection Store is housed underground. Its inherent passive thermal stability will protect the precious artworks from the site’s dramatic climate variations and reduce the need for mechanical systems. It also acts as a bushfire

Architecture of place

16—17

refuge and forms the reinstated hill to preserve the setting of the BEC. As a counterpoint to this the bridge building is in the spirit of plein air with a lower level of climate control appropriate to its use for workshops, accommodation, cafe and dining where indoor-outdoor flow is desirable. Variations in temperature, light, humidity and wind are opportunities for visitors to perceive place. Imagined as a piece of infrastructure, the singularity of the bridge’s form serves as datum to highlight the distinctive, undulating topography of Shoalhaven, an alternate interpretation of touching the earth lightly. Recalling the trestle bridges endemic to flood landscapes such as this, the new structure allows sporadic waters to flow beneath it and, importantly, for the reinstatement of the wet gully ecology, for children’s exploration and delight.

Postscript to fires

The Riversdale site faces the threat of flood from the river to the east and the threat of fire from forests to the north and west. Between the lines of the 100-year flood and an adequate asset protection zone lay a slither of available land for these new works. In a devastating show of just how vulnerable the site is, the road to Bundanon was burnt from the voracious path of January’s fires. Yet in this now post-apocalyptic scape of ashen earth and tinder sticks that is the future visitor’s prelude to Riversdale’s remaining beauty, there lies much opportunity for a new kind of eco-tourism: to learn about fire, its impact on and transformation of our ecologies. Repeat visits over several

years could be a way for visitors to experience the various stages of regeneration starting now when towns, especially on the New South Wales south coast need the economic boost. Bundanon Trust’s core business on the Riversdale site is school children. Imagine a curriculum structured around climate flux and environmental extremes: an authentic experience necessarily contingent on these vicissitudes, more than ideal states of poster blue skies and calm shores. Here instead is a kind of tourism that through purpose, place and practice can index the dynamism at the heart of Australia’s landscapes. From future vantage points we might witness the change in texture and silhouette of Arthur Boyd’s favourite hills as this damaged landscape renews.

Kerstin Thompson is Principal of KTA and Adjunct Professor at RMIT and Monash universities. A committed design educator she regularly lectures and runs studios at various schools across Australia and New Zealand. An Australian Institute of Architects Life Fellow, Kerstin plays an active role promoting quality design within the profession and through her talks and writings as a panellist on the Office of the Victorian Government Architect Design Review Panel.

Architect Victoria

→ Left Riversdale bridge render by Kerstin Thompson Architects. The new structure will allow water to flow beneath and the reinstatement of wet gully ecology. Dharawal Country

‘Acknowledging the sensitivities and complexities around this next stage of development at Riversdale, the new works will accommodate increased visitation in ways that preserve the estate’s most cherished qualities’

After Warracknabeal

Words

In the Wimmera, the conversion of disused wheat silos has created potential pathways out of traditional patterns of rural decline. In towns such as Brim, Nullawil, and Patchewollock, these art-led transformations have spurred tourist visits and catalysed surrounding networks and ecosystems. Treating infrastructure as large public canvasses has created an armature for a new truth-experience. However, the act of fabrication, whether making buildings or telling stories about them, can also reinforce existing views, approaches and understandings. As architects and designers operating in this region, we have been forced to reassess our own work in relation to the authenticity of this emerging reality. By relating our experiences in the After Warracknabeal courthouse project, we cast our initial design and subsequent restaging of the on-going refurbishment within the broader context of the Silo Art Trail. We suggest architecture can no longer be a simple signifier. Ultimately, our goal is to identify ways in which architecture becomes a platform for facturing authenticity (broadly defined modes of artisanship and making in general), as exemplified in the history of the silo canvas embedded in contemporary regional Victoria.

As outsiders, we initially understood Warracknabeal, a small town along the Silo Art Trail, as a regional centre in decline. Without a creative solution, we imagined continued downturns in population and economic activity, leading to a slow death. The After Warracknabeal project offered Warracknabeal an afterlife through an ambitious plan to transform its disused courthouse into a tourist drawcard. A radical architectural intervention into the site would create a small art hotel to attract tourists including artists. Under the auspices of Working Heritage, a public trust managing heritage places on Crown land in Victoria, the existing building would be revitalised for cultural and artistic use by the broader community. We sought to introduce and refine a prototype for regional transformation through creative practice, which could ultimately offer the chance of being replicated in other areas throughout Victoria and Australia.

The existing courthouse building was in good shape but needed significant interior renovation to create a multipurpose space for a working art studio, exhibition space, and flexible community facilities. Our approach was to maintain the

historical integrity of the building, only making changes required by the new program. These included removing the built-in furniture and some walls to create a larger space. The existing eastern annexe would house utility spaces – a kitchen, accessible bathroom, and external deck. In addition, a capsule-cabin was proposed for the northern edge of the site to host artist residencies. Placed amid a rewilded landscape, the capsule-cabin would set the big night sky in dialogue with the courthouse. When not accommodating artists, the cabin would be made available as a boutique art hotel.

After extended consultation and conversation with local residents during our visits to develop the After Warracknabeal project, we questioned our understanding of the region. How and why did the Silo Art Trail offer a more true experience of the region than we perceived, as visitors? We realised the project could not continue as we had imagined. The project must build upon the experiences of the people who call it home and the infrastructural landscape, which they inhabit. This meant developing a deeper understanding of the silos, which not only paint the landscape, but signal a more authentic experience of the Wimmera.

The Silo Art Trail has a vast repertoire of such canvases. Hundreds of tall concrete silos rise from the undulating landscape, marking the edge of a band of unusually productive clay soils that run northward from Horsham.1 They crouch at the edges of townships, as a set of visually interchangeable marks across the grain-belt of the Wimmera. There is something geological about them, as if they are more discrete eruptions of the same formations that

Architecture of place

Article

by Tom Morgan, Charity Edwards and Jason Crow

→ Right After Warracknabeal proposal by Monash Art Design and Architecture. Render by Stephen Hawken. Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk Country.

underlay the Grampians and Mount Arapiles. The silos read as surface manifestations of vast subterranean structures that form capstones to the tangles of steel conveyors, rail-heads, and long, barrow-like tin and timber sheds. These associated structures have long since eroded and dissipated. The silos are left as remnant outcrops. In this light, they read as the indicators of larger practices of regional retreat: residual objects, ‘reduced to landmarks of a declining rural community.’2

The implied redundancy and status of the silos, as witness to a passing community, misses a critical reality. The silos have been mothballed as farming practices have eclipsed their capacity. Infrastructures imagined and emplaced in the 1930s and 1940s are now ill-equipped for the scale and logics of these changed operations. Uniquely,

however, large-scale agri-business in Australia remains family owned and operated.3 These family farms break with extractive, industrial ideas of productivity.4 This leads to a key paradox. While the silos do function as registers of dramatic change, they are misconstrued as symbols of decline, which no longer mesh with current reality. Negative framing of the silos ignores their roles as markers of methods, approaches, and technologies that are now fundamental to the communal identity of the Wimmera. Not something geological, but rather something artefactual, requiring and inviting reappraisal and re-contextualisation. The silo in Brim was the first to be painted. Street artist Guido Van Helten’s set of towering portraits formed the nucleus of the new tourist art trail.5 The conversion of these leviathan silos into vast →

Architect Victoria

18—19

‘We now understand the towns of the region as potential sites for civic creative practice, where we support the local population in contributing their own knowledge, skills, and insight to structure their own authenticity.’

Architecture of place

→ Above Brim by Guido van Helten (2016). Image still taken from After Warracknabeal (2018): a short film by Matthew Bird, Tom Morgan and Charity Edwards, in collaboration with cinematographer James Wright, and with sound and music by Daniel Jenatsch. Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk Country.

20—21

canvasses repeats the endeavor by Le Corbusier to render silos, as operative constructions of our modernity. The French architect gained notoriety for ‘falsifying’ photographs of silos, such as Montreal’s Silo 2. Architectural historians overlaid external values on the doctoring of the photos, rendering the work inauthentic, much as we misread the After Warracknabeal project. The benefits of possible fabricated narratives - especially around notions of redundancy and ruin – now structure a set of investigations and interventions, which we hope will invert the usual post-industrial and post-growth narrative of cultural tourism.

In the now revised After Warracknabeal project, interventions into the courthouse build from community needs for accessibility and serviceability. The project has required re-examination of what programing would most benefit the community. Our intent is to physically and figuratively open the space toward new civic creative practices. Toward this goal, a new entry ramp and threshold condition comprise a significant portion of the capital works. A new ablutions block will also be installed at the north-west corner of the courthouse. In consultation with the community, these modifications will enable the courthouse to better serve community needs. The intended flexibility extends to the ablutions block, which can be relocated to other suitable sites within Yarriambiack Shire.

The design will now function as a set of adaptive tools for the community, allowing the courthouse to serve functions beyond the ones we originally proposed: studio, gallery, and artist residence. Emerging from our most recent deliberations is a more locally-led direction for the site. The most surprising change for us was how little architecture featured in the mix. Far more pressing has been addressing the nuanced demographic shifts in the population and the creative practitioners already working in the wider region. We saw a need for diverse programming in the

refurbished building, which leverages the strong intersections between community volunteering and cultural life in Warracknabeal. To that end, our focus has shifted from the building to a pilot program of workshops in and with the community.

The process of developing this project has not only changed how we practice, it has transformed how we imagine Warracknabeal. We no longer frame regional Victoria as a place in decline. We now understand the towns of the region as potential sites for civic creative practice, where we support the local population in contributing their own knowledge, skills and insight to structure their own authenticity. Construction continues. The first stage of After Warracknabeal is due to open in mid-2020. In the meantime, we are working with members of Warracknabeal on projects that further build community through listening, caring, and making together.

Dr Tom Morgan, Charity Edwards, and Dr Jason Crow are practitionerresearchers from Monash University’s Faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture. The After Warracknabeal project is part of an emerging research agenda that explores ways in which components of design and creative praxis can be used to interrogate, animate, and activate communities and their implicit knowledges and practices. The expanded team enacting this research works across a variety of sites and communities in Melbourne, regional Victoria, and the broader Asia-Pacific context.

Notes

1 Robinson et al. (2005) Wimmera Land Resource Assessment. DPI Victoria

2 Athanasios Tsakonas (2019) Victoria’s Silo Art Trail, Fabrications, 29:2, pp 273-276,

3 Grain Growers Limited, State of the Australian Grain Industry, 2016

4 ibid

5 Athanasios Tsakonas (2019) Victoria’s Silo Art Trail, Fabrications, 29:2, pp.273-276,

6 Inspired perhaps his reading of essays written by Walter Gropius and Adolf Loos, Le Corbusier modified a series of photographs of silos, which would later be published in his Towards a New Architecture. Though barely mentioned in the text, these false images of silos would become critical exemplars of Modern Architecture. they must be maintained.

Architect Victoria

Designing in sensitive environments

Words by Adrian FitzGerald

We have been designing cultural tourism facilities both here and overseas for a number of years. During this time visitation has grown at extraordinary rates. Stonehenge receives 1.58 million people each year while the Architecture Biennale in Venice receives 600,000. Both are UNESCO World Heritage—listed sites of great sensitivity. Closer to home, the business case for the Shepparton Art Museum predicts growth of 10.6 per cent, while the Twelve Apostles has 1.2 million visitors, contributing $190 million to the economy.

The question facing architects is how to design tourism facilities in these highly sensitive environments. Via our work, plus current work in World Heritage Al Ula in Saudi Arabia, we posit three approaches: subsume into the landforms; tread lightly upon the land; or boldly contrast with the landscape. All of which we have adopted for different projects as appropriate.

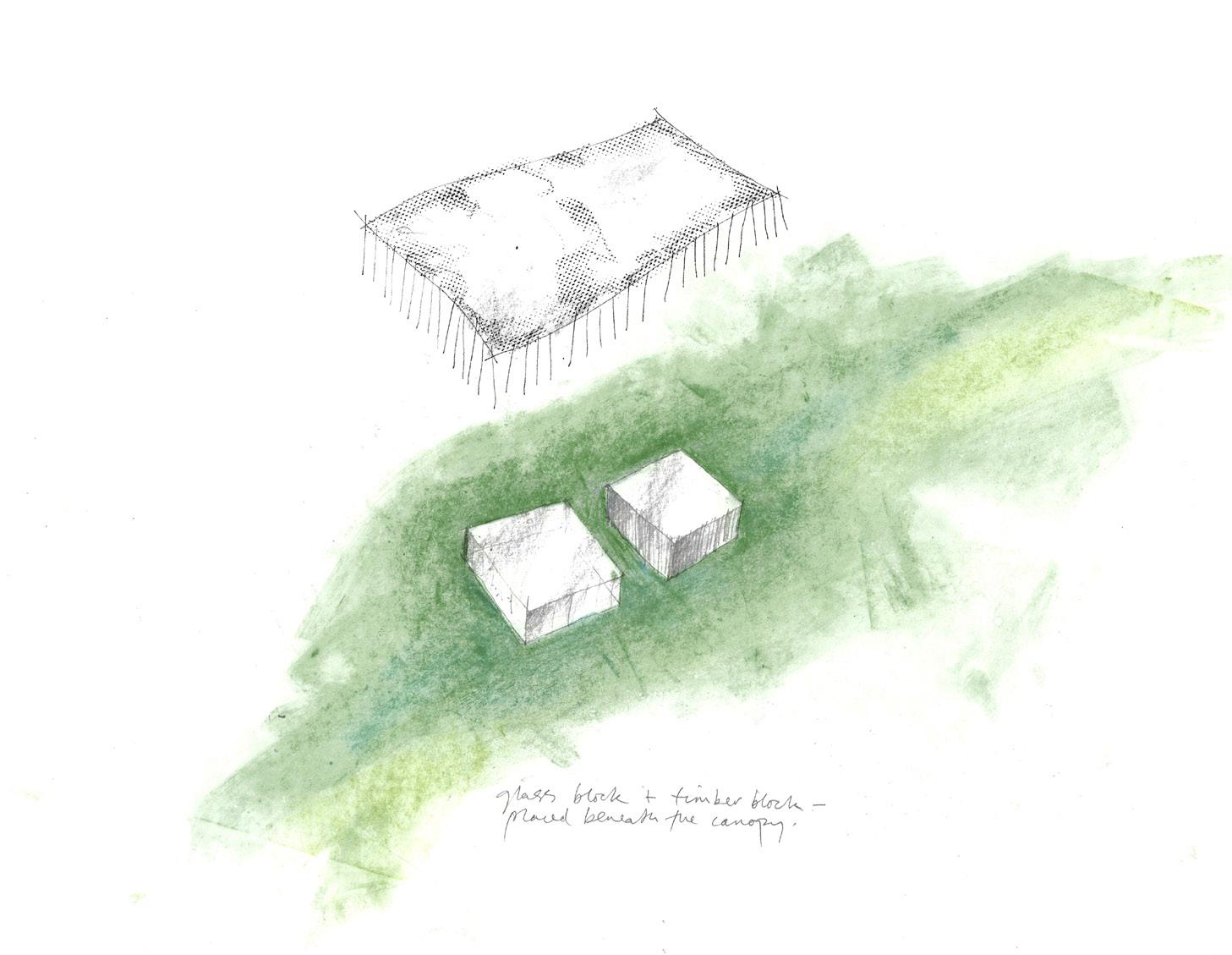

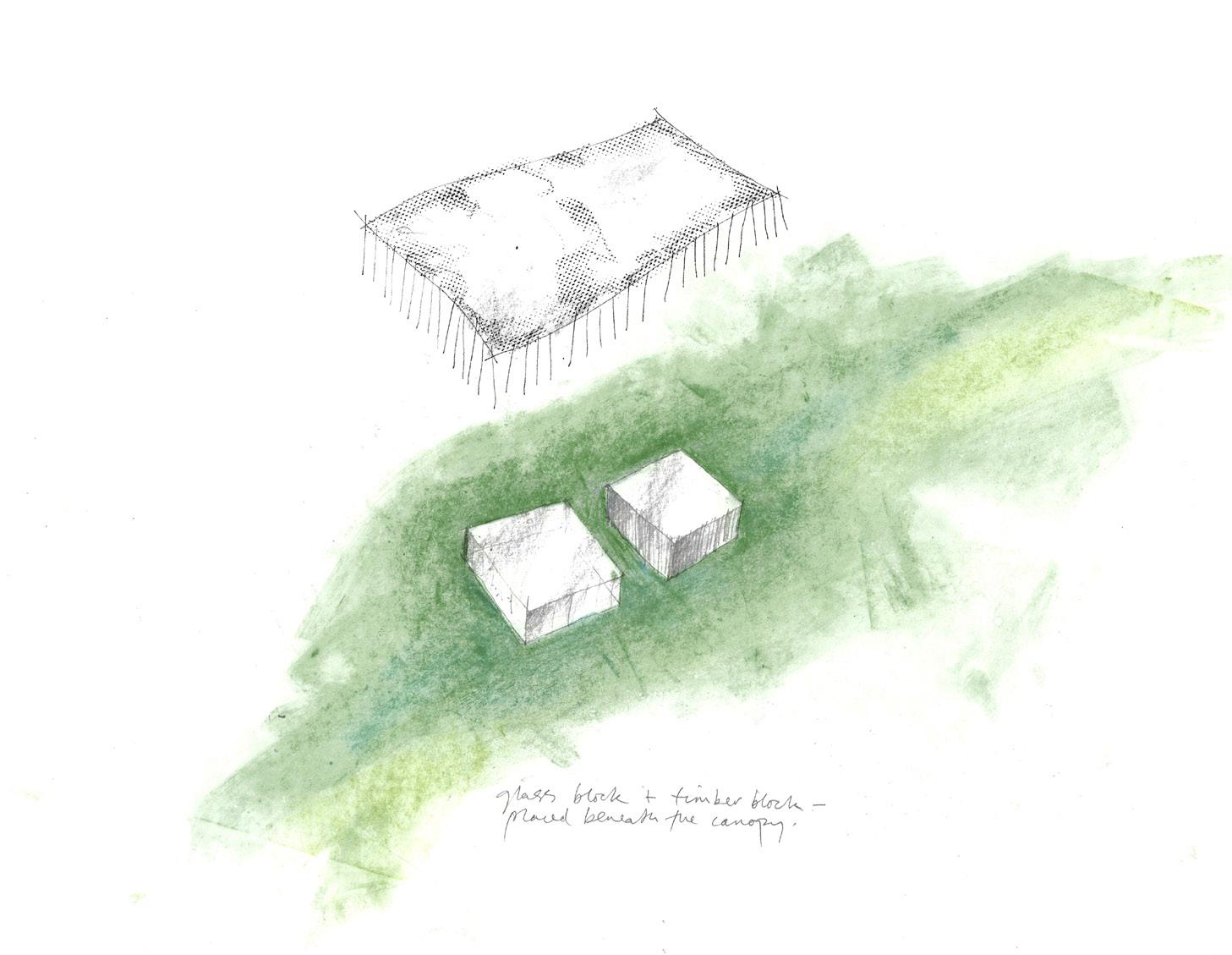

Our first commission in 2001 for the Stonehenge Exhibition and Visitor Centre for instance, subsumes into the land. It seems to us that visitor centres for buildings or monuments pose an architectural dilemma. They exist because of another sensitive structure, but their

very presence sets up a dialogue. Scale, materials, setting and form, how does a visitor centre affect the visitor’s experience?

The power and imagery of Stonehenge derives not so much from the actual size of the monument, which is relatively small, but rather from its relationship to its setting. Stonehenge sits alone on windswept open plain. A composition of huge slabs of bluestone and sarsen stone, it is effectively a historic 4500-yearold work of land art. The experience of the stones, while monumental in the landscape, are comparatively small. To avoid overwhelming their scale we proposed to partly bury the visitor centre marking it with a series of zinc arcs exposed in the terrain. This first scheme was abandoned. We were later selected for a new, smaller scheme, 2.4 kilometres from the stones. It was briefed to have as little visual and physical impact as possible. This included below ground disturbance, as the Salisbury Plains are one of the most significant archaeological sites in the world. The resultant building has the lightest possible touch with the ability to return the site to its previous state –built over fill so underground services don’t affect the heritage crust. The

building also echoes the rolling plain with a thin perforated canopy plate sitting on a pincushion of columns sheltering two simple cubic volumes containing visitor-centre uses, one transparent and mainly of glass, the other solid and mainly of timber. We also felt it was important not to overscale the stones. We wanted to ensure the vistor centre did not convey a subliminal image of the stones being smaller than they really are, so the height of the canopy roof is kept lower than the tallest trilithon, while the pods with their volume diffused by the overhanging canopy, take on an ephemeral quality of lightness in contrast to the permanence and mass of the stones. For the Australian Pavilion in the heritage Giardini della Biennale in Venice, we adopted a sculptural counterpoint to the gardens. The pavilion is a distinct presence within the Giardini of the utmost simplicity, architecturally expressed as a white box within a black box. Envisaged as a pure object rather than a building, it is a container on, and in which, ideas can be explored, where the container in no way competes with those ideas. Australia built a temporary pavilion in 1987 designed by Phillip Cox. In 2008, for the ideas competition organised by Ronnie Di Stasio, we proposed the simple black box containing a white box with no connotations whatsoever of national character. →

of place

Architecture

Article

→ Right The Australian Pavilion in the heritage Giardini della Biennale in Venice is a bold object in counterpoint to the gardens.

Architecture by Denton Corker Marshall

Photo by John Gollings

→ Stonehenge Exhibition and Visitor Centre treads lightly on the Salisbury Plains Architecture by Denton Corker Marshall

Architect Victoria 22—23

It was an interesting speculation because we have designed embassies and thought about the issue of trying to find an Australian expression overseas – the idea of how a building says something about the country it represents – Cox looked for this in vernacular Australian architecture. Having designed gallery spaces, we know artists are not enamoured in overly elaborate architecture – they just want white neutral space. So, we proposed a building, that is simply, a blank canvas and container for exhibits. Why a black box? Black objects have a history in art –Malevich’s Black Square of 1915 for one, or in cinema with Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey. We liked the reference to a black stele suddenly appearing and changing the world. We were dropping the enigmatic black object into the middle of the Eurocentric art scene and setting a challenge.

In terms of an appropriate Australianness, it seemed important to us the pavilion have memorability. Our design is unexpected in its simplicity and its austerity, stripped and reduced, startlingly simple – but utterly memorable. To achieve this you have to be confident and we see this as one of the things it expresses about Australia – a young country that now feels able to express itself confidently on the world stage.

The Shepparton Art Museum (to be completed later this year) adopts the same approach of a contrasting form placed within its lakeside parkland. It is characterised by a straightforward clarity to create a compelling cultural landmark. The restricted ground floor, required by a floodway across the site, is turned into a real opportunity by extruding the small footprint vertically over five levels, creating a distinctive small and

tall art museum. This has advantages in maximising much used park space while creating a beacon in the flat Shepparton landscape. It also offers prospect to the lake, town centre and river redgum reserve from the rooftop events space. We also applied a subsumed strategy to cleverly conceal all loading dock and service areas in an introduced landform – an art hill, extending the park up to the firststorey gallery cafe. →

Architecture of place

Article

→ Above Shepparton Art Museum by Denton Corker Marshall (2020) adopts a tall and small bold approach. Yorta Yorta Country

24—25

On the Shipwreck Coast, Denton Corker Marshall with McGregor Coxall and Arup utilise all three approaches – subsumed, treading lightly and bold counterpoint. The Twelve Apostles lookout is perched on top of the cliffs, to both elevate and experience the scale and heightened drama of the incredible landscape. We introduced two contrasting, leaning blocks, one resting on the ground and the other cantilevering into the sky. The initial experience is unsettled, deliberately bringing visitors to a high point, framing a view downwards. An unexpected shift, by leaning the form, creates a feeling of being exposed on the edge of the world, before entering a warm, timber-lined interior providing shelter with revealing defined panoramas.

The Loch Ard Gorge blowhole is a surprising and thrilling experience. The lookout is conceptually subsumed into the landscape, revealing itself as unexpectedly as the blowhole, with a singular, sculptural shell-like object anchored in the land. The dynamic form creates ever changing views stretching the viewing perimeter while hiding much of the structure. The shell offers partial protection from the elements and is shaped to amplify the

dramatic atmosphere of sound and spray.

Nearby, the Port Campbell Creek Bridge lightly touches its environment, bringing visitors from the town into the ethereal, serene and floating experience above the water and sand before plunging into the escarpment. A lightweight suspension structure, anchored by irregular masts, provides a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal landscape.

All cultural tourism sites are distinctive and utterly unique. Approaches in either subsuming, treading lightly or contrasting can strengthen and enhance their special identity of place.

Adrian FitzGerald is a Senior Director at Denton Corker Marshall. Adrian has been an integral part of the significant growth and success of the practice over the past four decades. This has encompassed extensive international experience including 14 years in the London, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore studios. He is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects, serving as a National Councillor and on award juries and committees.

Architect Victoria

‘The question facing architects is how to design tourism facilities in these highly sensitive environments’

Experience-based architecture

Words by Peter Walker

Architecture has the ability to accentuate and even create unique experiences which drive tourism. However, in a climate where too much tourism can contribute to the degradation and destruction of place values, future demand will require models in which architecture must contribute to the protection, maintenance and regeneration of those values that make places unique. Of the many reasons people travel, one of the strongest is our desire to have unique, authentic experiences. In an experience-based economy, differences born out of evolutionary pressures and geographic separation become an advantage in creating place-based uniqueness. And architecture is, in many ways, an embodiment of this uniqueness – a manifestation of culture, tradition, innovation, economics, identity and, ultimately, place. In this context, it is not surprising then that architecture plays a lead role in tourism – not only through the historical vernacular but also the contemporary icon.

As a practice Cumulus Studio has been exploring the role architecture plays in tourism. Of all the sectors in which we work, tourism development has the most scope for the creation of interesting,

iconic architecture, which can inspire and create truly lasting memories. However, how should thinking about sustainability affect our design approach?

In several of our recent projects, we have taken valuable historic buildings and, through careful treatment and accentuation of their remarkable embodied characteristics, transformed each into highly unique and industry-acclaimed tourism destinations. These include the adaptive reuse of an early 19th century apple picking shed into a cider house and museum for Willie Smith, a 1940s hydro pump station into a wilderness lodge at Pumphouse Point and Launceston’s Ritchie’s Flour Mill into boutique accommodation for Stillwater Seven. The authentic history, ideas and stories ingrained in the buildings add significant value from a tourism perspective.

Furthermore, prior to their conversion, each of the buildings had reached or passed the economic use-by-date of their original purpose. In the case of both Willie Smith’s and Pumphouse Point, the buildings had been vacant for decades and in advancing states of decay. Through adaptive reuse these buildings have been given a sustainable future that

preserves their embodied values and stories for generations to come. This is not a new idea. As architects we are challenged not just to ‘do no harm’ but also move to a model where architecture contributes towards regeneration. Recycling buildings plays a small part in our collective responsibility to create an environmentally and culturally sustainable future. And tourism provides an economically sustainable model for this.

While it is relatively easy to see how this model can work in an urban context, it is more challenging to consider in relation to natural settings. Increased visitation through intense tourism in many places is destroying the natural asset that was the original drawcard.

Currently, we are involved in two projects within the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area which recognise the potential for a symbiotic relationship between tourism and the natural environment.

The Viewing Shelter at Dove Lake is a public project designed to responsibly accommodate high numbers of tourists. The strategy encourages the majority of visitors to access controlled areas by increasing accessibility, while the more sensitive areas require an additional effort to access, naturally reducing visitor numbers. The architecture is solid and weighty, acting as a chapel in →

Architecture of place

Article

→ Right Located at the end of 250-metre flume projecting into Lake St Claire, Pumphouse Point has become a tourism destination in its own right. Architecture by Cumulus Studio (2012). Photo by Stuart Gibson. Palawa Country

Architecture of place Article 28—29

which to contemplate and respect the environment in which it sits. It is designed to leave the visitor with a renewed appreciation for the place’s ancient geology, as well as an understanding of why it needs protection. The project is located on previously impacted land and enables the revegetation of damaged landscape.

Contrastingly, our project for Halls Island just outside the Walls of Jerusalem National Park involves the creation of four completely removable lightweight shelters for commercial accommodation. These shelters are tent-like, suitable for sleeping and basic bathing only. The project utilises a high-value, low-turnover approach, giving guests an authentic, close to nature, no-frills experience within a vast rugged environment. The project will also protect and rejuvenate sensitive landscape damaged by previous users of the site, which ultimately leads to a more valuable visitor experience.

In both of these projects, best practice Environmentally Sensitive Design strategies, such as siting, material use, internal environment, water systems, and energy use have all been considered. However, these two projects also aim to give back to their environment in small ways.

Above all they hope to inspire visitors to consider their environment from an alternative perspective and challenge them to act respectfully towards it.

Peter Walker is the Director and co-founder of Cumulus Studio. With over 20 years industry experience, particularly within the tourism sector and in the adaptive reuse of existing buildings. Peter has led international award winning tourism projects at Pumphouse Point, Devil’s Corner and Saffire resort (while a director at Circa Morris-Nunn Walker). He is also a former recipient of the Australian Institute of Architects (Tasmanian Chapter) Emerging Architect Prize and Dulux Study Tour.

Architect Victoria

→ Left The historic Apple Picking Shed that houses Willie Smith’s cider house, Huon Valley. Architecture by Cumulus Studio (2012) Photo by Johnathan Wherrett. Palawa Country

‘Of the many reasons people travel, one of the strongest is our desire to have unique, authentic experiences’

Place value

Words by Scott Balmforth

Cultural tourism has often resulted in the idea that the building itself is the focus of a tourist economy. For our practice, the central importance of place determines the design project.

Early projects were key in establishing and articulating key concepts central to all TERROIR projects. The planning and organisation of Peppermint Bay in Tasmania, for example, navigated between an inside-out process of incorporating key site qualities into the generative diagram and at the same time recasting a commercially oriented brief. So, notwithstanding the formal qualities, it is less about architecture as icon or commodity but founded in the creation of a location-based experience, where the ecological, spatial and cultural dimensions of site are not replaced but elaborated upon through the project.

These ideas reached maturity through a series of projects in regional Victoria, many in collaboration with Sally Hirst (Hirst Projects). Sally provides a series of important insights around the role of high-visitation public projects to a local community – both in terms of its identity and economy.

Our first collaborative project with Sally – Koondrook Wharf – is an exemplar of how this union works, combining in the project an understanding of the specific story of that place and enhancing that story through our architectural proposition, while also delivering a project that has economic benefits to the community and region. With a population of only 900 people, the removal of its wharf fifty years ago had disconnected Koondrook from an ecosystem of economy and recreation on the Murray River. Our response to a technically oriented brief to reconstruct the former wharf, questioned what a wharf would deliver, and so broadened a discourse from reinstatement to how community could once again come together at the river’s edge. This approach resonated with the community and council who could see potential in thinking through the project in an expanded way and how this would recast the way they might connect the town to the river in a specific way that differentiated from nearby towns.

By thinking about different relations and how they work across different scales, the project became a device that connects people to the

river in multiple modes. The project includes a number of actors – human and material – who have a strong relation to this place: local Indigenous artists are featured; residents and visitors can occupy platforms that weave through the river redgums, platforms made of locally sourced and milled native redgum; while a 28-metre-long single-span gangway links to a floating pontoon that allows all-year-round docking for recreational boats, large paddle steamers and house boats.

Two recent projects – one just completed and one underway – have extended these ideas and deployed them on a larger scale. The recently completed Penguin Parade Visitor Centre is a key part of a natural and financial ecosystem managed by Phillip Island Nature Parks. The site is part of the largest land buy-back for a single species in history. Completed in 2010, the Kirner Government started the process of buying back private holdings on the Summerland Peninsula. →

Architecture of place

Article

→ Right Koondrook Wharf

Architecture by TERRIOR with Hirst Projects

Photo by Adam Gibson Barapa Barapa Country

Architecture of place 32—33

The design of the Penguin Parade Visitor Centre extends this logic. Like people moving out for the penguins, the previous visitor centre made way for a new penguin habitat which will add considerable resilience to the penguin population. The completed building is somewhat dramatic at present but will eventually all but disappear into the three different abutting landscapes. The building is less an icon and more of a brooch that gathers these landscapes together and responds to each in specific ways – formally and experientially.

The interior is structured around part of the overall choregraphed pathway from visitor arrival to penguin viewing experience at the beach. This spine has the capacity for large crowds (up to 4000 visitors per night) and off each side are dedicated spaces for ticketing, education, retail and hospitality. Between the spine and these spaces is a layered edge of unprogrammed and indeterminate third space which enables individual experience and interpretation. Thus, while the interior is arranged around a very simple pathway – a line in the landscape – the third space is instrumental in connecting visitors to this place; that moment when visitors pause and reflect and when this reflection generates visitor engagement.

With the Puffing Billy Railway Visitor Centre in the Dandenong Ranges, currently under construction, the challenge was how to enhance this already iconic and much-loved hero. Addressing the stresses of a massively increased visitation – half the line regularly exceeds capacity, yet only 10 per cent of visitors travel the second half, a new visitor centre was proposed in the 2017 Masterplan by Tract Consultants, at the midpoint of the railway line, Lakeside Station in Emerald Lake Park. Once part of a 180-hectare plant nursery, the beauty of the park has made it a key destination since the reopening of the line in 1955. Departing from the language of building as icon or object, we proposed a simple extension of the Lakeside platform, which foregrounds the true heroes of the experience; the trains and the landscape. Once completed, the dark-clad building will disappear somewhat, pointing visitors to what already exists at the site rather than the architecture. Thinking relationally, instead of seeing the building as the primary outcome, it intertwines economic, cultural and spatial logics with a specific ecosystem and landscape in a way that can transform all of them.

Scott Balmforth is a founding Director and Principal of TERROIR. The practice was established in Hobart and Sydney simultaneously in 1999 and expanded internationally with TERROIR ApS in Copenhagen in 2010. Scott has led a range of award-winning and internationally published architecture and urban design projects, including 2019 International Architecture Awards for Koondrook Wharf and the new Penguin Parade Visitor Centre.

Architect Victoria

→ Left Penguin Parade Visitor Centre, Phillip Island by TERRIOR Photo by Peter Bennetts Bunurong Country

→ Puffing Billy Railway Visitor Centre, Lakeside Station, Emerald by TERRIOR. Render by Doug and Wolf Boon Wurrung and Woi Wurrung Countries

Exploring markets

Words by Elizabeth Campbell

Food and food culture have long, deep connections with the history of a place, reflecting settlement, geography and cultural traditions. At a human scale these qualities can frequently be seen in local recipes, food festivals and daily rituals centred around the preparation and sharing of food. But what about the architecture that provides platform to this activity? How does an architectural typology influence the way people experience food specific to place?

In many contemporary cities around the world, street names, size of urban blocks and relationship to urban fringes can be traced back through food — specifically the way in which it travelled into the marketplace to be sold, swapped and traded. This has been clearly identified in major Western cities through historical maps dating back to the 17th century, including London, New York and Rome. These urban drawings capture data showing the history of street names that were associated with the specific food trade founded upon it.

Some of these traces can also be found in Australian cities through the history of colonial settlement and the export of social structures associated with market

typologies. Melbourne is home to several traditional markets, each home to unique produce and local people. South Melbourne, Queen Victoria, Prahran and Preston markets are the most well-known. Of the four, South Melbourne is the oldest continuing market in the city at over 150 years old, although there is some debate about this claim. Historically, the role of the market has been home to generations of local families connected to the food trade, some of which have been operating under its changing roofs for over 50 years. It has also been a place for supplying fresh, local food to residents.

Throughout the twentieth century, the evolution of the market typology into supermarket – a space of convenience which offers everything under one roof, impacted the relationship between food culture and place. The supermarket also changed urban form, while a marketplace has open edges and spills into a place, a supermarket is a closed box veiled in large signs arrived at by car, a common experience anywhere in the world. This shift challenged the marketplace; however, it is not only the community reliance on South Melbourne Market that has continued

to increase, it is a place for residents of surrounding suburbs and also an attraction for a growing number of visitors keen to experience local food, people, history. The market facilitates this through offering a diverse range of opportunities for visitors to have unique interactions of food and place. Through spatial arrangement, scale of small retailers along internal streets or the permeable edges and the direct connections with stall owners, the market promotes social connection, both intimate and collective. There are places to stop, sit, eat and drink. Wide streets invite people to wander slowly, narrow spaces create bumping shoulders and main axis create direct routes through and promote faster foot traffic. These varied spaces promote different paces adding to the overall energy.

The interior environment reflects an ad-hoc layering of different times and styles. It has been renovated numerous times and is an eclectic mix of materials — brick, terrazzo, marble, timber and brass. Signage and wayfinding are additionally mixed media, some handwritten, some fonts in many different sizes. Some stalls have been thoughtfully designed, while others look as though they have not changed since they opened many →

Architecture of place

Article

decades ago. This is a trait of markets all over the world, their function is so closely tied to the quality of produce sold and the relationships built with people over time, often the importance of a homogenous aesthetic is not necessary — and rather, the chaos adds to the energy.

There is an extensive visitation and local community rhythm to the daily and weekly operation of the market that spreads beyond into the wider realm of South Melbourne. According to the latest available annual report, visitor numbers are increasing. This foot traffic is also beneficial to businesses in the surrounding streets, many of which have been there since the late 1800s. The people behind the counters are passionate about the food they are selling; they know where it comes from, they are proud of how fresh it is and care about the way it is sold. Described as ‘a quintessential village market – a place where people love to meet, eat, drink, shop, discover, share and connect –tightly woven into the fabric of the community it serves. It is central to the culture, heritage and place of South Melbourne and its surrounds.’ The South Melbourne Market remains

historically, an example of a typical architectural typology that provides the armature for the trade of food unique to place as the market, the agora. Typically, markets were found at the centre of urban environments. They provided and continue to provide a connection to place much richer than a supermarket. They are catalytic platforms for commerce, social exchange and often informed the urban form and development of a city.

Elizabeth Campbell is a project architect at Kennedy Nolan with a broad range of experience across single and multi-residential, cultural and commercial projects. Supplementing her professional work, Elizabeth is part of the Architect Victoria Editorial Committee. She is also involved in teaching, critique and dialogue at Melbourne, Monash and RMIT universities.

Architect Victoria

34—35

‘a trait of markets all over the world, their function is so closely tied to the quality of produce sold and the relationships built with people over time, often the importance of a homogenous aesthetic is not necessary’

Architecture as host

Words by Gregory Burgess

Recently, in the middle of a bushwalk with friends through steeply folded country, I took my shoes off to go barefoot for a while. Suddenly, long protected toes and soles were registering every subtle shift of gradient, tiny stones, decomposing bark and leaves, delicate twigs. I continued, wincing, with tender footfall; reflecting on our usual way of being in nature as onlookers and wondering how Wurundjeri may have experienced this country in preEuropean times. There was a breeze. I was aware of its note as it blew across my ear. I could feel my hair lifting, the roots straining slightly. Perhaps there was an increased receptivity – we had agreed at the start that this would be a silent walk, to be as present as possible. Usually we tend to separation, lacking attentive sensing – listening, observing, beholding –and literally being out of touch with ourselves, our communities and our environment. This in turn is reflected in our architecture. In a sense, our buildings are us; they speak through their gestures. Can we improve the responsiveness of our architecture through our own experience?

In a small, tall, and darkened room, staggered lengths of muslin were suspended. A film was projected