AL BAHA: FROM VERNACULAR TO CONTEMPORARY STONE HOUSING

Saleh Mansour

Saleh Mansour

Saleh Mansour

First and foremost, Alhamdulillah (all praise be to God) for making my seven-year educational journey possible.

A special thanks to my father, whose unwavering support provided everything I needed and who took on my role in caring for my younger sisters and brother while I was away. To my mother—thank you for being my comfort during difficult times.

I extend my gratitude to my studio professor, Scott Allen, for generously sharing his expertise, offering invaluable guidance, and providing thoughtful critiques that profoundly shaped this work. His insightful feedback was instrumental in refining my research and design approach.

I am deeply grateful to my dear friend Ahmed Salem for his invaluable contributions, sharing both his extensive knowledge of vernacular houses in Al Baha and his high-quality images.

Finally, my sincere appreciation to Abdulaziz Mousa, Architect Abdullah Al Fahad, Engineer Abdulkareem Al Ghamdi, and Engineer Abdulrahman Al Khaldi for their generous assistance with images, research materials, and insightful guidance.

Saleh Mansour

May 4th, 2025

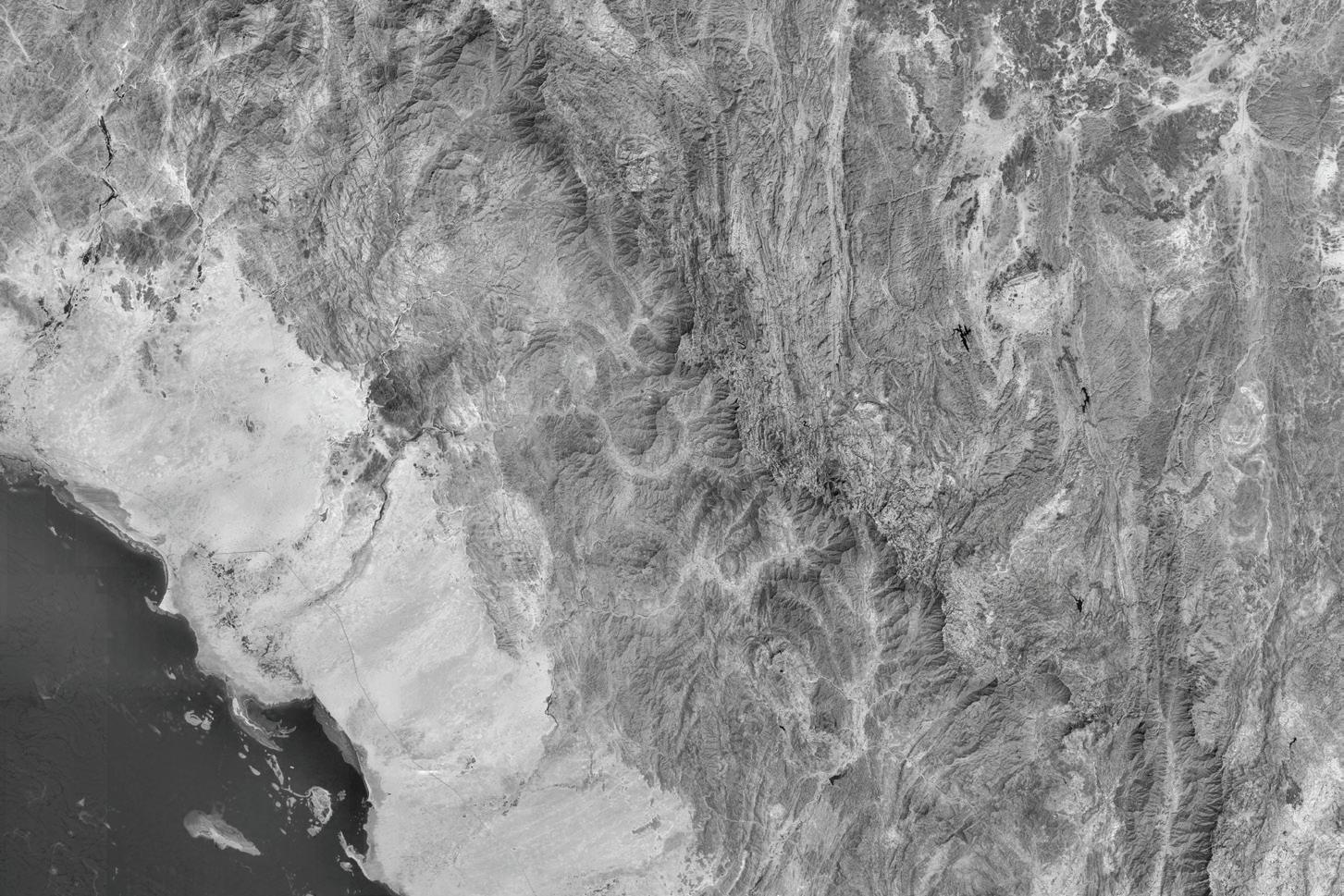

Location

Al Baha Region is located in the southwest of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is placed south of Makkah and north of Asir Region. It is the samllest region of Saudi Arabian, covering around 4,000 mi² (around 0.60% of Saudi Arabia). Al Baha City, the capital, sits at an elevation of 7,014 feet (2,138 meters) on a hilly plateau and is encircled by juniper-covered terraced hillsides. Al Baha includes 11 municipalities: Al Aqiq, Baljurashi, Al Hajrah, Al Makhwah, Al Mandaq, Al Qara, Bani Hassan, Bani Kabir, Ghamed Al Zinad, Maashuqa, and Qilwah [1]. “Over 70% of Al Baha is occupied by Al Sarawat Mountains and adjacent plateaus. Al Sarawat Mountains strongly slope down to meet Tihama Plains (approximately at the sea level)” [1].

Socio-Economic Context

For eternity, the main job of the local community was farming and herding. They carved the hills around their villages to be farmable, creating amphitheaters and waterways to cultivate rainwater and utilize it for growing agricultural grains, pomegranates, peaches, apricots, grapes, and many other crops. This, as in many mountain communities around the world, depended on the annual rainfall, so it was unsustainable. The living conditions were sometimes great and sometimes tough [2].

This remained unchanged up until the discovery of oil and the beginning of urbanization of Saudi Arabia, where the local youth started to seek opportunities in the growing cities. Many of the farmers would send their kids to seek jobs and abandon the unsustainable lifestyle. That resulted in the abandonment of most of the farmlands.

A major migration to the larger cities occurred, where most of the migrated locals would visit their hometowns once a year during the summer [1].

This shift resulted in the mixing of cultures between the locals and the newly urbanized locals as they introduced what they have seen in the larger cities. Attempts of applying plaster and paint, and trying to incorporate electricity and plumbing into tradtional stone houses started to appear [2](Fig 3,4,5). Reinforced concrete also was introduced for the first time in Al Baha. At the time, no serious building code that analyze the regional social and environmental conditions was introduced, so everyone started building different houses forms and styles, copying from the trending styles that were not properly designed for the local context [3].

“The adoption of foreign models in the planning and design of newly developed communities in Saudi Arabia yielded serious problems with respect to people as users and physical elements as responsive to people... Traditional built form was never perceived by builders in terms of geometric relationships and arithmetic measures, in contrast to contemporary built form which is so perceived by professionals. The built form was a product of a thorough understanding of the basic needs and associated functions in the cultural milieu of the inhabitants” (Eben Saleh, 1998)[1].

This resulted in a hideous picture where a mixture of unorganized, disproportionate, houses that does not serve the functional needs of the inhabitants. One would rarely see successful design attempts here and there.

The adoption of national and global residential design themes resulted in a grey picture of Al Baha that does not represent the vernacular architecture. These designs conflict with the region’s social and environmental needs.

The goal of this thesis is to attempt to reintroduce the deep-rooted stone houses heritage in a comprehensive contemporary way that represents the unique qualities of the vernacular architecture of Al Baha and addresses the functional and social needs of the inhabitants.

Before attempting to theoretically re-shape the housing design language for any local culture like Al Baha, there is a necessity to examine the architectural history of that culture. In this case of Al Baha, There are existing remains of fout building types:

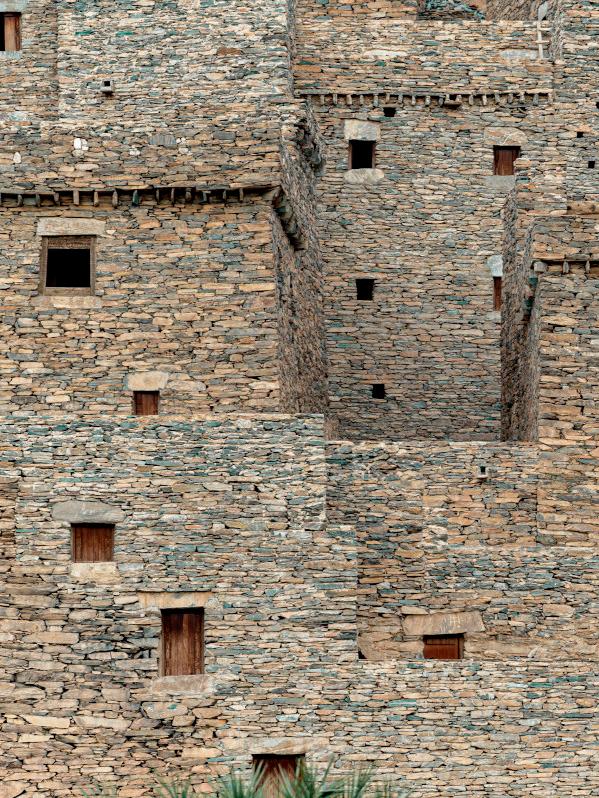

1. Stone houses (Fig. 6).

2. Fortresses (Fig. 7).

3. Castles (Fig. 8).

4. Agricultural Terraces (Fig. 9).

Studying the habitants functionality of these types helps shaping the understanding of the reasons why they are designed the way they are.

“Residential expansion in the traditional era was accompanied by the establishment of new agricultural areas and defensive structures. A constant balance between the built environment and cultivated land was maintained in order to achieve an equilibrium between human growth, available natural resources, and defence considerations” (Eben Saleh, 1998)[1].

The research methodology consists of two stages to develop contextually appropriate architectural solutions. In the initial phase, vernacular building components will be systematically documented, categorized, and deconstructed before being reinterpreted through contemporary design paradigms to enhance their relevance for modern inhabitants. The subsequent phase involves comparative analysis of exemplary global stone architecture projects to distill fundamental design concepts. These derived principles will form the basis of a customized design framework that responds to Al Baha’s specific cultural and environmental conditions. This analytical process directly engages with the study’s primary research objectives, generating actionable guidelines that bridge historical authenticity with present-day requirements. This investigative process will yield an architectural proposition that thoughtfully synthesizes regional identity with innovative design thinking, offering solutions that are simultaneously rooted in tradition and adapted for contemporary living standards

Al Baha locals used to build their houses using stone and available local materials such as wood and mud. The construction is lead by master builders who have knowledge of the local stone and wood types and the skills to construct and craft.

“Stone buildings are highly sophisticated structures as specific knowledge of stone types is required. Therefore, they are not easily built by any habitant; instead, stone buildings are usually built by three (or more) specialized individuals” (Baabdullah, 2020)[3].

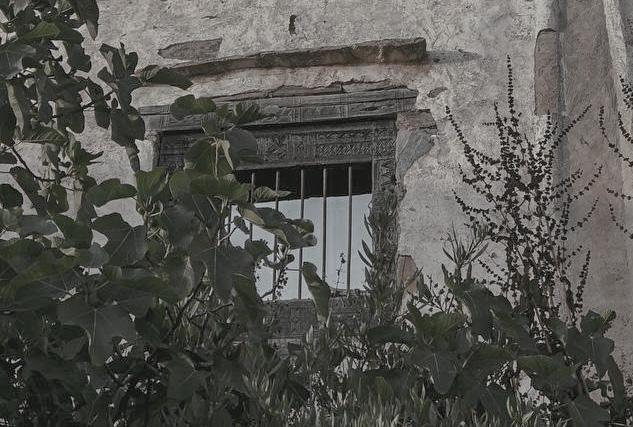

To describe the building style briefly, it includes thick stone walls to protect from tribal raids and the harsh climate in such altitude [1](Fig. 11), ornamented wooden doors and windows crafted from local juniper and wild olive trees (Fig. 12), layers of wooden ceiling members resting on a wooden beam with clay on top as insulation (Fig. 13), and finally ornamented thick wooden columns called “Al Zafer” (Fig. 14).

“There are interiorly visible components of the structure that support Al-Zufur (plural of Al zafer) (Fig. 10), and some work as ornamenting elements. Al-Zufur are protected from humidity by flat, circular-like stones placed under each Zafer, called Sufun. However, above a Zafer, a Wesad is fixed; it is a flat wooden capital that carries Al-Wusuh. A basic structural unit is the wooden beams stabilizing Al-Zufur, and the roof; locally called Al-Wusuh. Consecutively, Al-Bitana layer reinforces Al-Wusuh with thick wooden beams fixed perpendicularly above it.

The final phase of the interior roofing process is of thin wooden boards layer called Al Jard, and it is covered by tree bark called Al-Ghelaq; ensuring that mudding slits are blocked. Finally, an iron hook is fixed in Al-Jard and is called Al-Me’laq. This is used to hang clothes, weaponry, dates, or meat” (Baabdullah, 2020)[3].

AL-Wesad: 1:1 the top width

Al-Zafer: 1:4 the top width

Al-Wesad + Al-Zafer: 1:5 the top width

Al-Wesad + Al-Zafer: 1:7.5 the bottom width

Proportions

3. Al-Sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi)

As nails for some joints Materiality

Ornaments

Components Wood Steel 1. Local Juniper 2. AL-Gharab (populus euphratica)

1:9.5 the top piece height (Al-Jibahah)

2. AL-Gharab (populus euphratica)

3. Al-Sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi)

Wood Steel for 1. Local Juniper

1. Nails

2. Al-Nojoom (Knobs)

3. Al-Zirfaal (Latch) 4. Door Hinges

Materiality

Ornaments

Components

Al-Zirfaal

1:8.5 the top piece height (Al-Jibahah)

1:8.5 the side piece with (Al-U’bbor)

2. AL-Gharab (populus euphratica)

3. Al-Sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi)

Wood Steel for 1. Local Juniper

Ornaments

Components

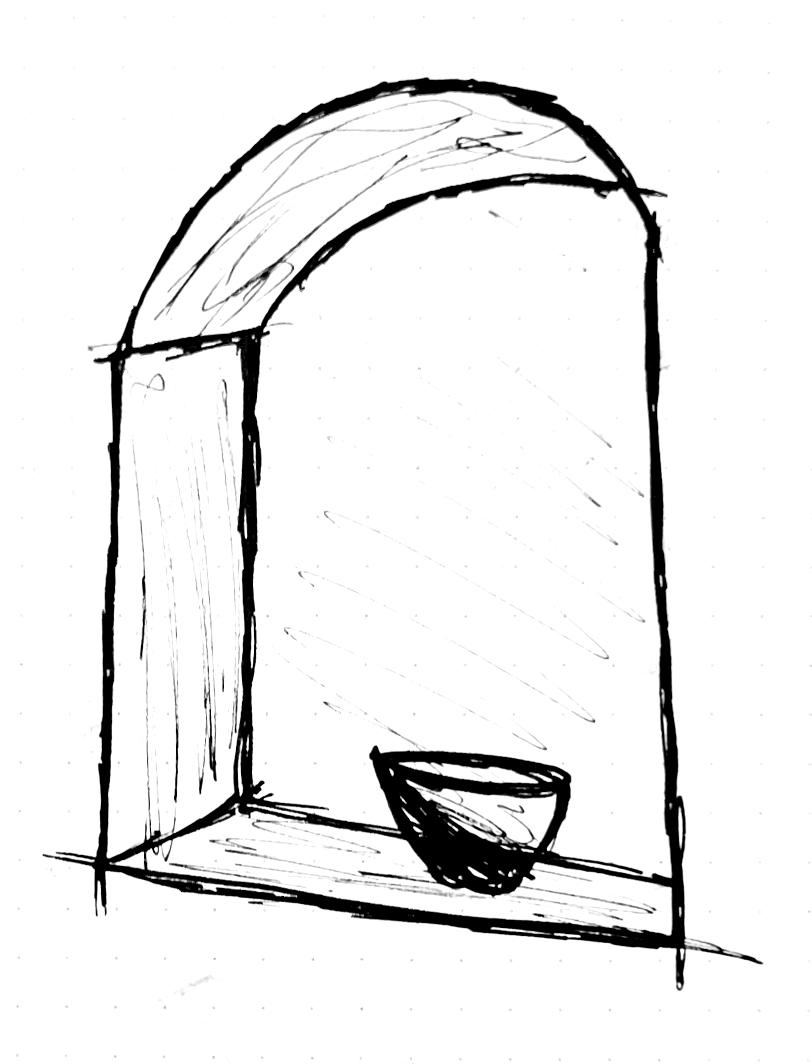

Al Hellanah is a traditional architectural feature. It is a wall opening serves as a storage niche, blending practicality with vernacular design. It reflects regional building customs while offering functional space for household items within domestic interiors

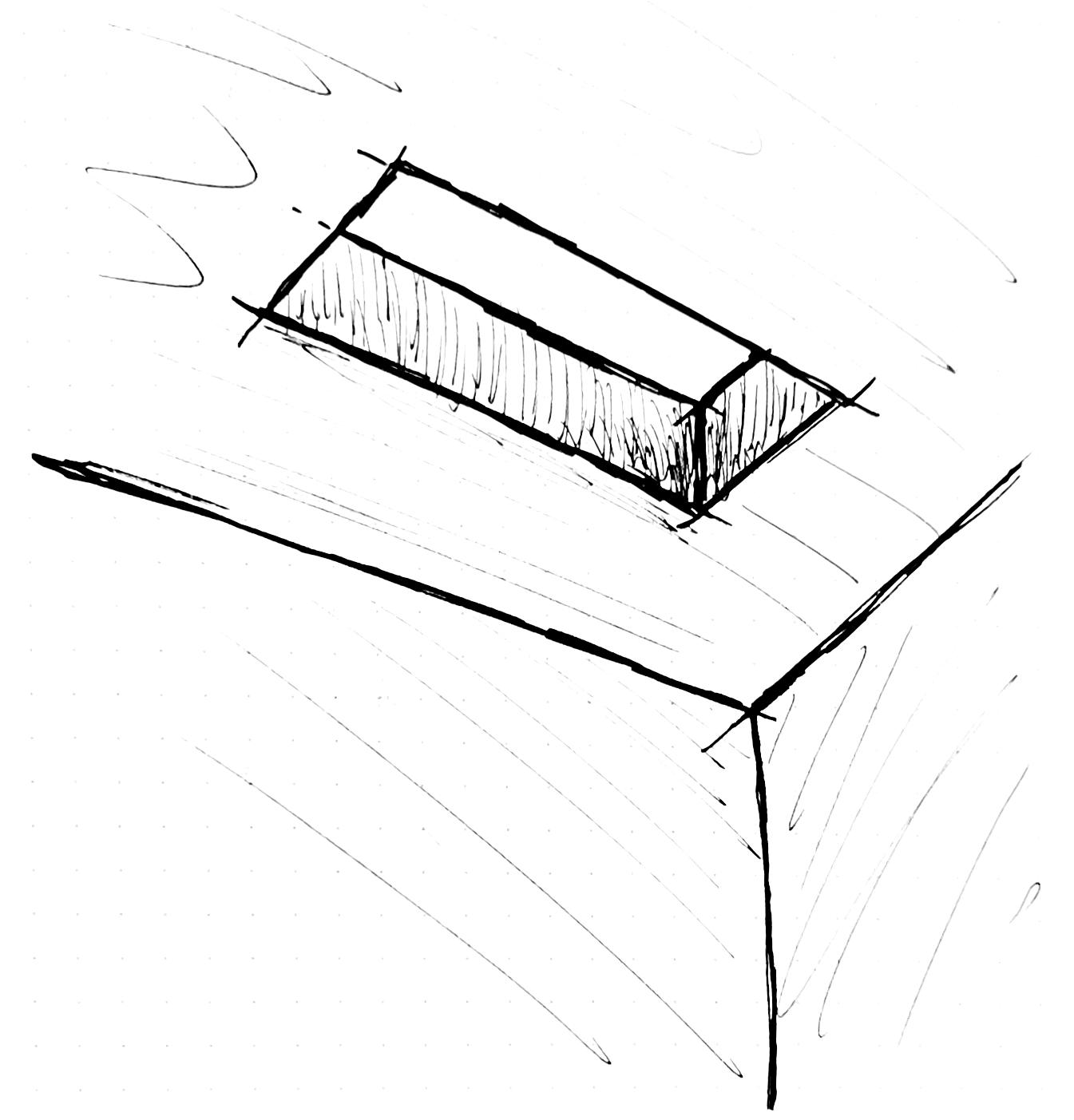

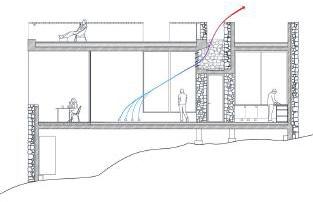

Al Kutrah is a traditional architectural feature found in Al Bahah’s buildings. This ceiling opening provides both natural light and ventilation, demonstrating the region’s climate-responsive design. The element reflects local ingenuity in passive cooling techniques while maintaining cultural authenticity in vernacular construction.

Al Joun is a traditional architectural feature where the upper part of a stone house projects slightly outward, adorned with triangular quartz stone decorations. This detail blends functionality and ornamentation, reflecting regional craftsmanship while adding a distinctive aesthetic to the structure.

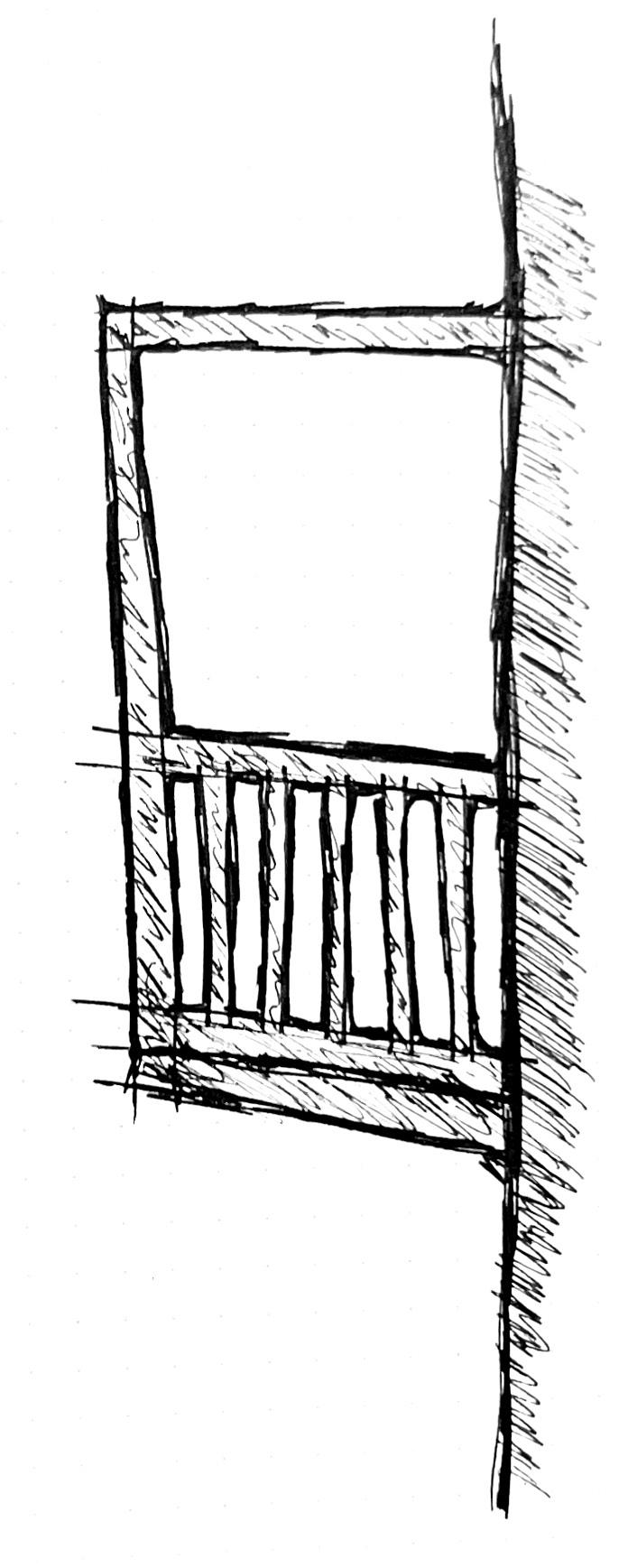

Al Ra’ash is a traditional architectural element—a projecting wooden balcony used for shade, ventilation, and discreet observation. Positioned on upper floors, it balances environmental function with social privacy. This feature exemplifies how vernacular design responds to climate and culture, offering valuable insight for contemporary architectural reinterpretation.

After looking at the basic elements of the vernacular architecture of Al Baha, it is critical now to analyze international precedents. Eight initial precedents accross three continets were chosen.

The goal of studying global precedents that use stone as the main material is to look into ways of intigrating this material in a creative aesthetic manner. The aim is not to imitate any of the 8 precedents, rather, identify and analyze areas of spacial and formal exellence and organize them into a general list of criteria. This will help any designer who wishes to use stone in a contexual contemporary way.

In order to maximize the benefits of looking into global examples, an initial list of criteria has been created to choose the best examples that fit the criteria:

- Must use stones as the primary material

- Must address the desired functionality of the users

- Must provide the contextual climatic response

- Must be in a mountainous city

- Must be designed at least in the last 30 years

- Must derive from local architectural philosophy

- Must uses overal local materials & methods

- Must represent the city’s overall language

017 Stone House

Chosen Precedents

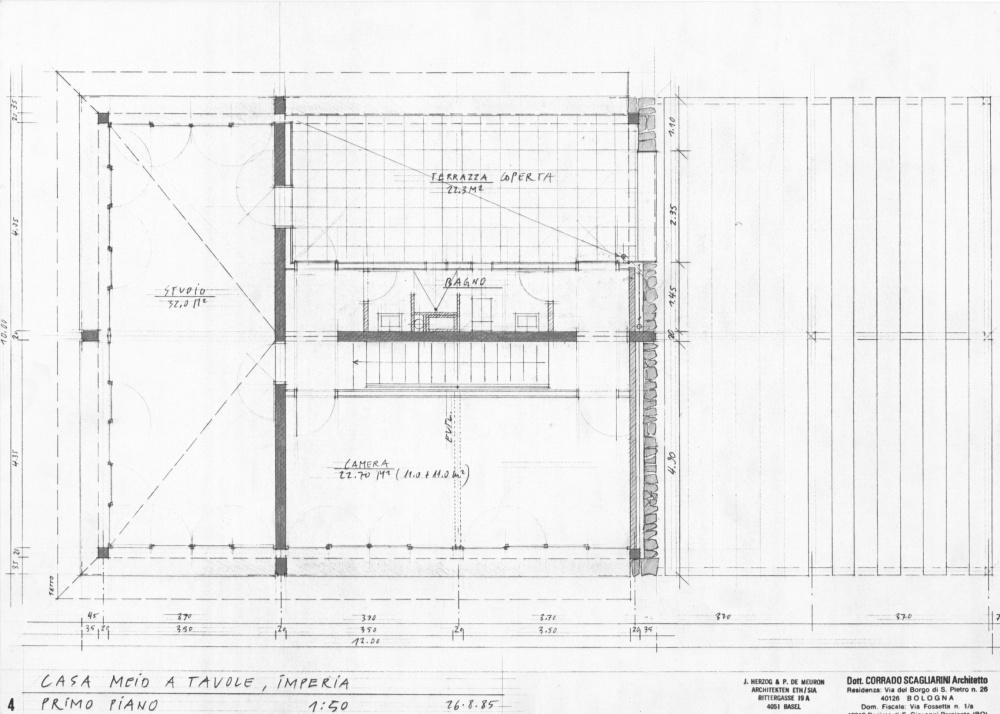

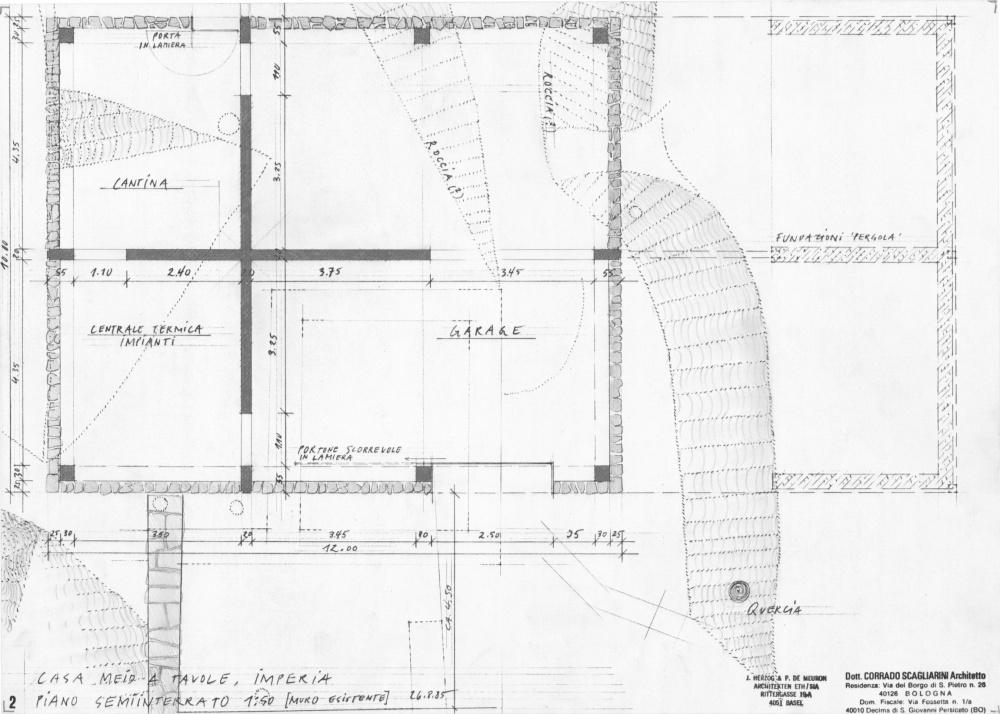

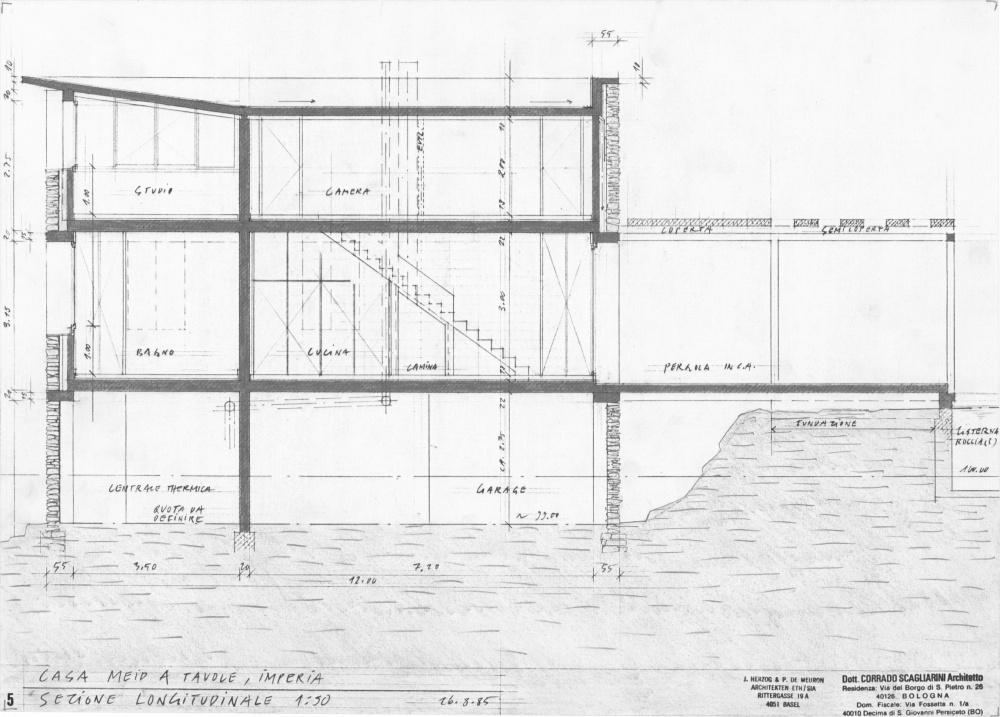

1. 017 Stone House. Herzog & De Meuron. Tavole, Italy. 1988

2. Hanil Visitors Center. BCHO Architects. Danyang-Dun, South Korea. 2009

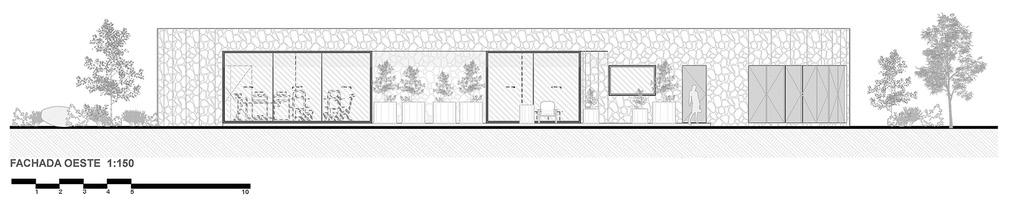

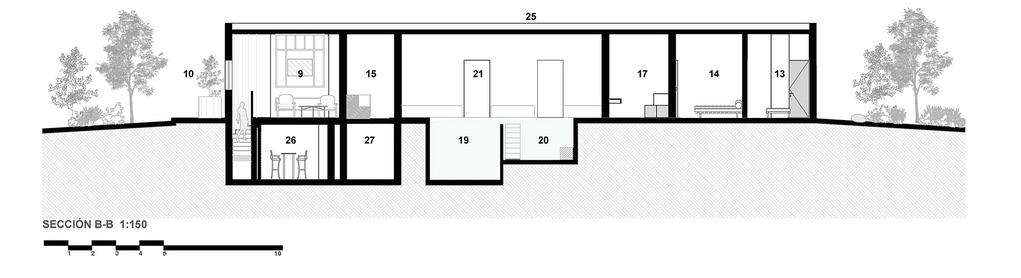

3. Caceres Stone House. Tuñón Architects. Caceras, Spain. 2018

4. Sao Bento Residences. Pedra Liquida. Porto, Portugal. 2019.

5. Quizek 1865 Winery. PL-T Architects. Tibet, China. 2021

6. Spa 28.0855. VAN VAN Atlier. Tapalpa, Mexico. 2023

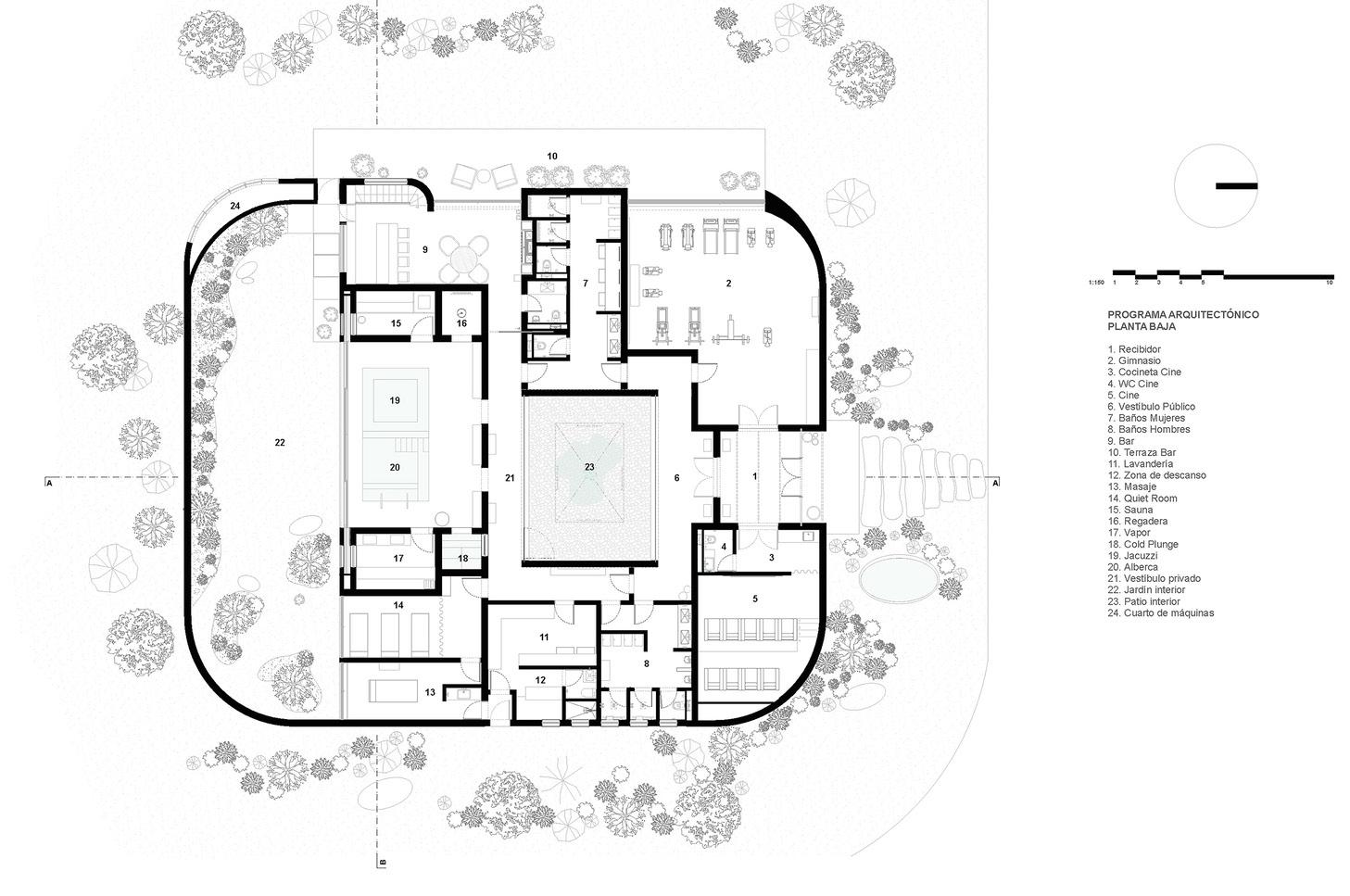

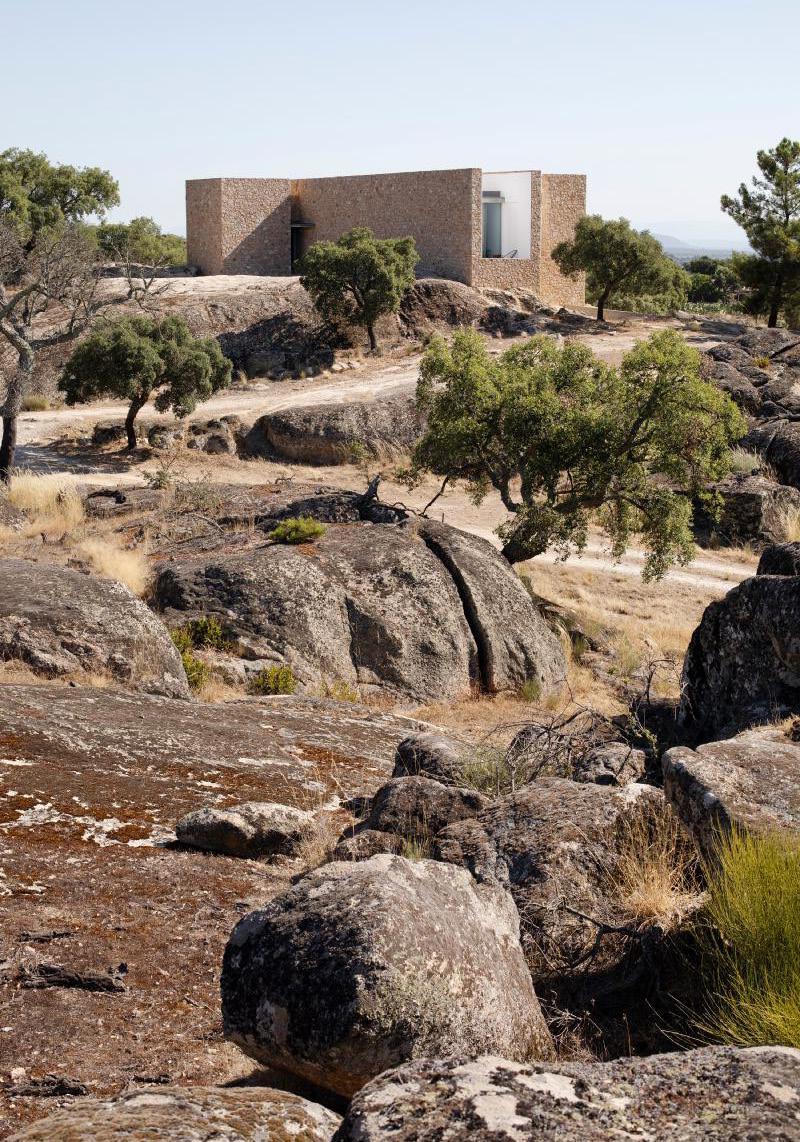

7. Atlier Landauer House-Studio. Atlier Landauer, Castelo De Vide, Portugal.2024

8. Mrizi I Zanave Hotel. Plisatelier. Lezhë, Albania. Date unkown.

Five of these eight case studies which fit the criteria the most were chosen for the analysis. Mrizi I Zanave by plisatelier provides the most spectacular design solution to an existing stone building, but unfortunately, no documentation was found except for Instagram posts by the architect @Plisatelier. For that reason, the precedent was dropped out of the analysis.

Quizek 1865 Winery Atlier Landauer House-Studio

sqft

sqft

sqft

Atlier Landauer House-Studio

Castelo De Vide

Atlier Landauer

Quizek 1865 Winery

PL-T Architects

Mrizi I Zanave Hotel

Plisatelier

Sao Bento Residences

Pedra Liquida

Tibet

Porto House-Studio Winery

Lezhë

Rustic Farmhouse High-rise

Thesis Proposal

By Herzog & De Meuron. Tavole,

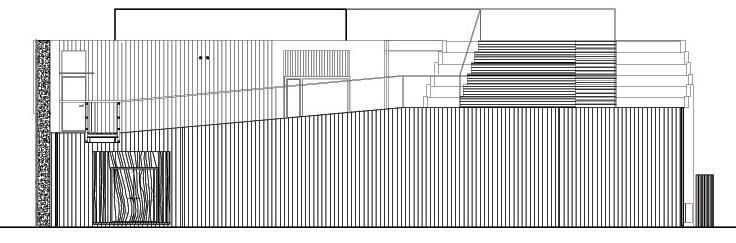

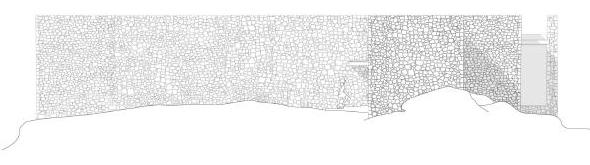

“Set in an undulating landscape of abandoned olive groves, the three-storey house stands on a promontory, engaging part of a former stone terrace. The design concept of the house is based on the fusion of plan, elevation and section. The building is characterized by a cross, made visible in the construction of the side walls where the in-fill dry stone comes in contact with the reinforced concrete frame. The structure occupies the centre on the “piano nobile“, while on the top floor spaces are more interconnected. Here, the house rises above the trees, giving a panoramic view through the vertically articulated strip windows. This notion of extension has its equivalent in the opposite direction with the raised terrace and its pergola-like enclosure. The external wall infills are of slate-like rubble stones, the window shutters are of steel sheets and the door and window linings are of split slate sheets. On the whole, the detailing is spare”. (Herzog & de Meuron, 1988)[9]

Civered Terrace

Stairs

Garage

Bathrooms

Cellar

Facilities

Bedroom

Studio

Living Rooms

“The Purpose of this project is to educate visitors about the potential for recycling concrete. In Korea concrete is the primary building material so it is imperative that we begin to re-use, the otherwise waste, concrete as buildings come down and are replaced. The Information Center is an example of how to re use this material in different types of construction, casting formwork types as well as re-casting techniques. Concrete has been broken and recast in various materials creating both translucent and opaque tiles. The displays will continue to evolve and change at the Information Center as new techniques are developed. The gabion wall and fabric formed concrete which constitute the main façades of the building, was erected first, and the concrete left over from it was recycled in the gabion cages, on the rooftop for insulation from sun, and as a landscape material at the street and around the factory. The site is located to the westernmost part of the factory, adjacent to Mt. Sobaek National Park. The existing land had been changed much to facilitate the movement of trucks to the cement factory. First of all, we tried to restore the damaged original mountains and forest. In order to revive the landscape, we brought in earth to fill the courtyard between the two buildings. The flow of the mountains from the west leads to the reception and cafeteria in the inner courtyard of the building. In the in-between spaces we allowed people to experience the mass of the building while watching the building shift around it’s central courtyard” (BCHO Architects, 2009)[10].

Kitchen/kitchenette

Rest Area Storage Dining Stairs

Bathrooms Courtyard Vestibule Unidentified

Living Rooms

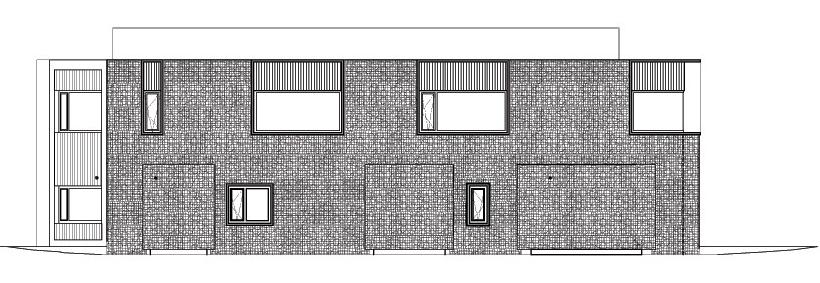

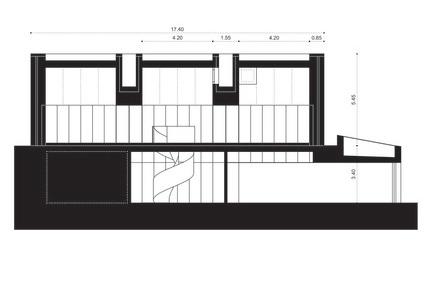

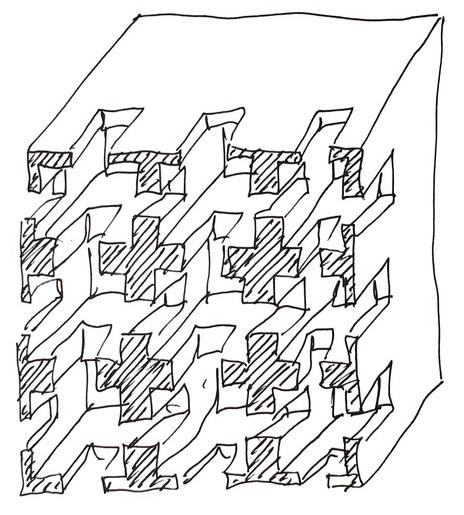

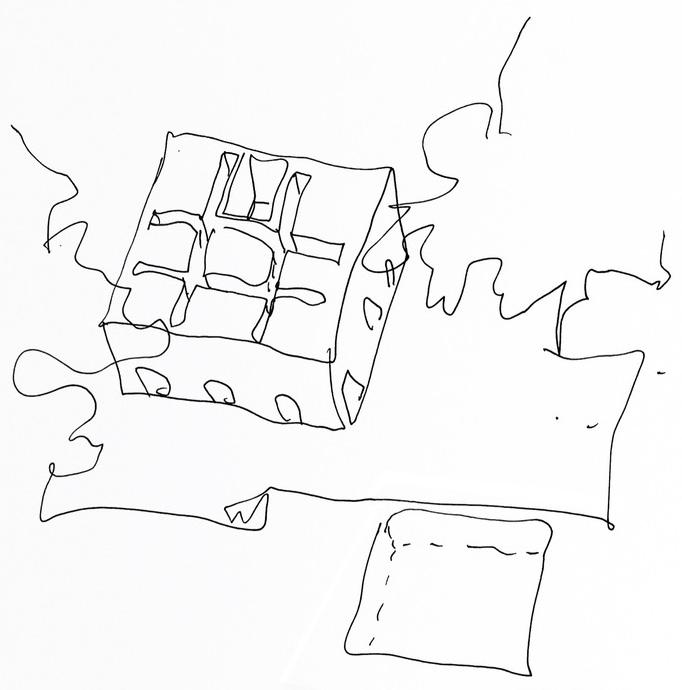

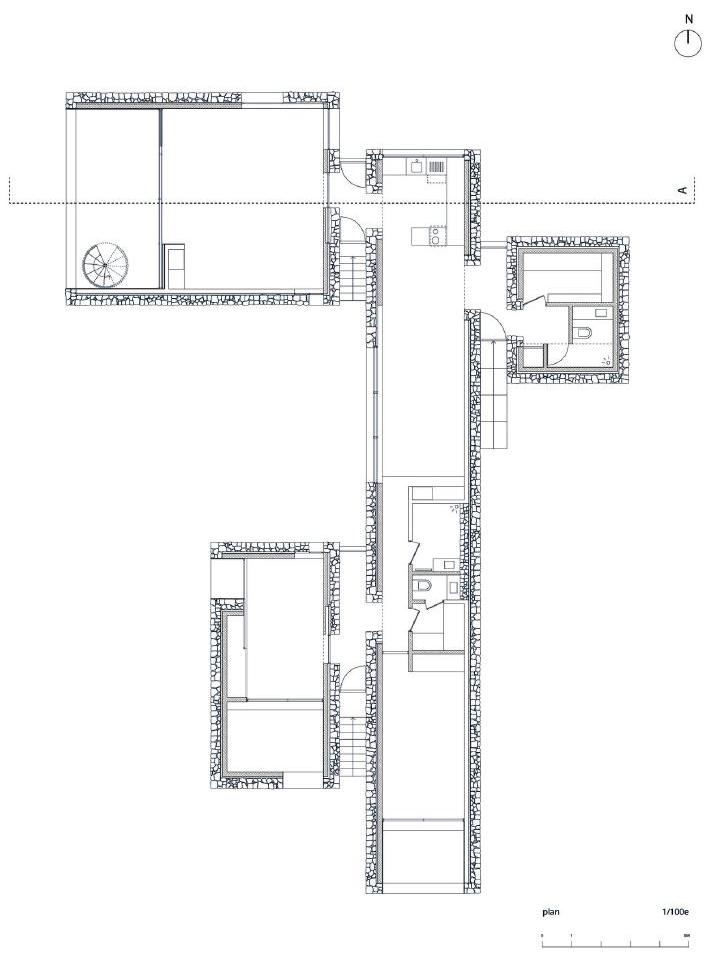

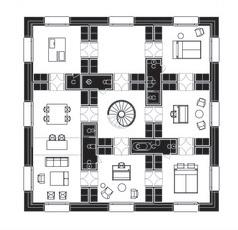

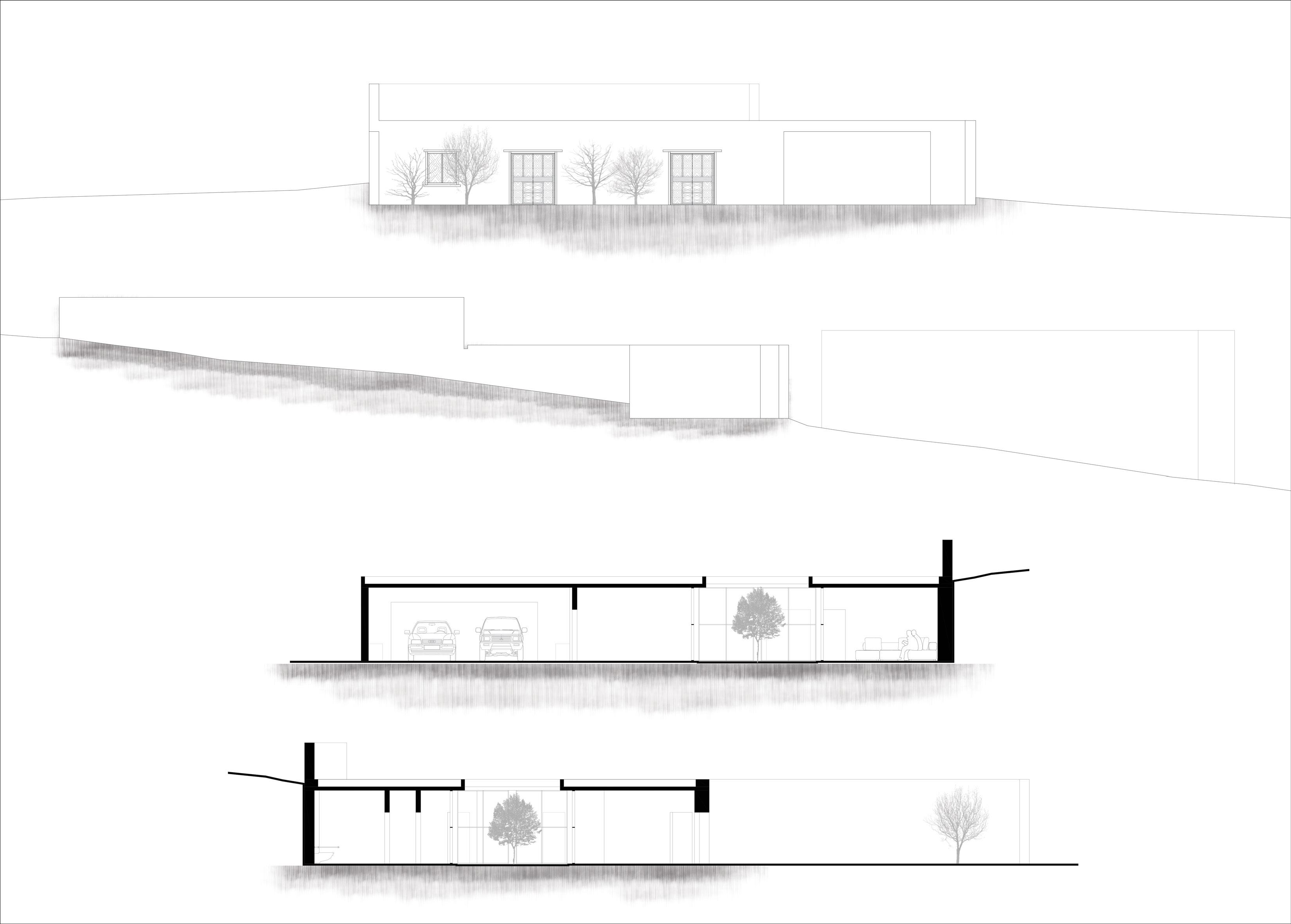

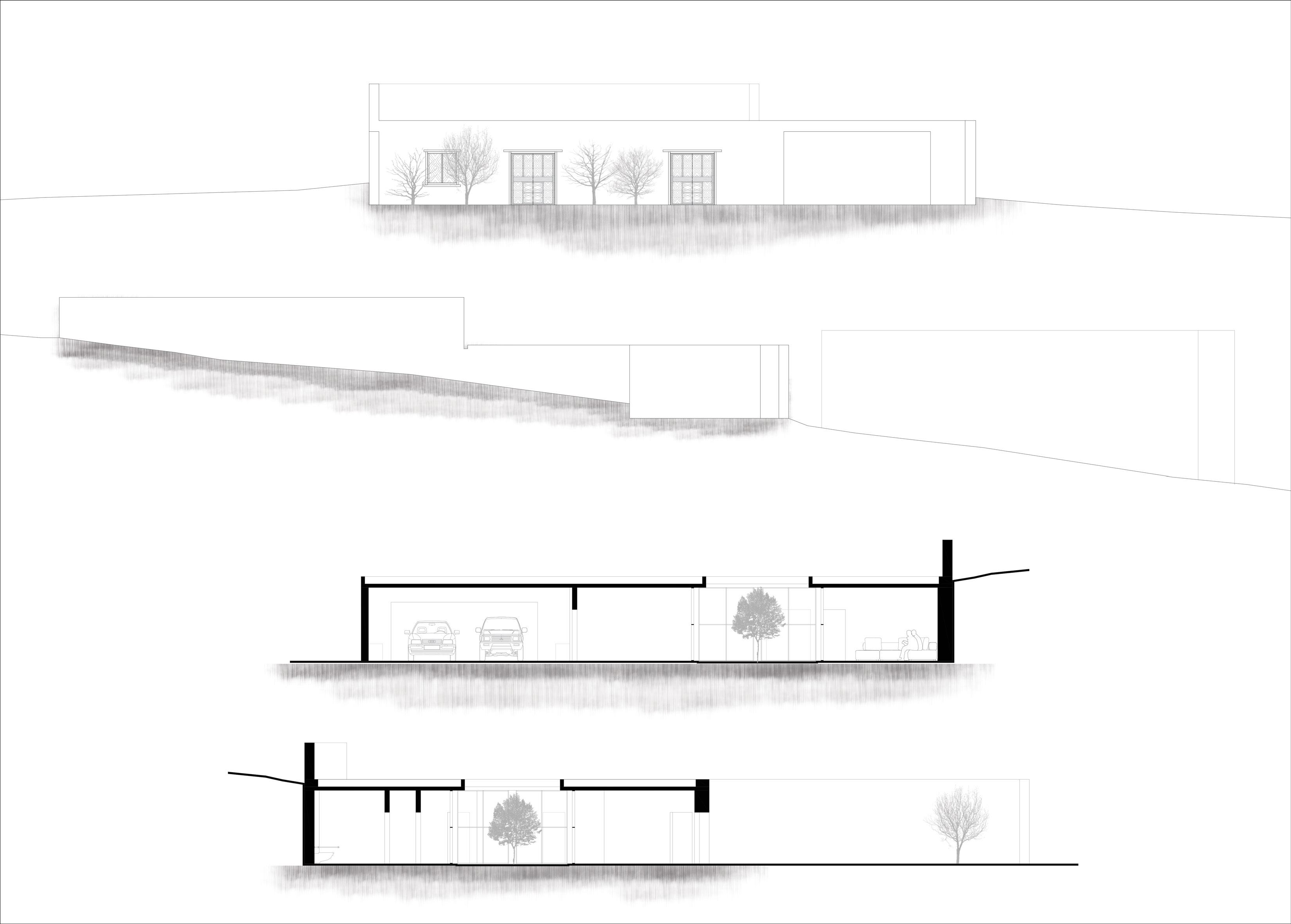

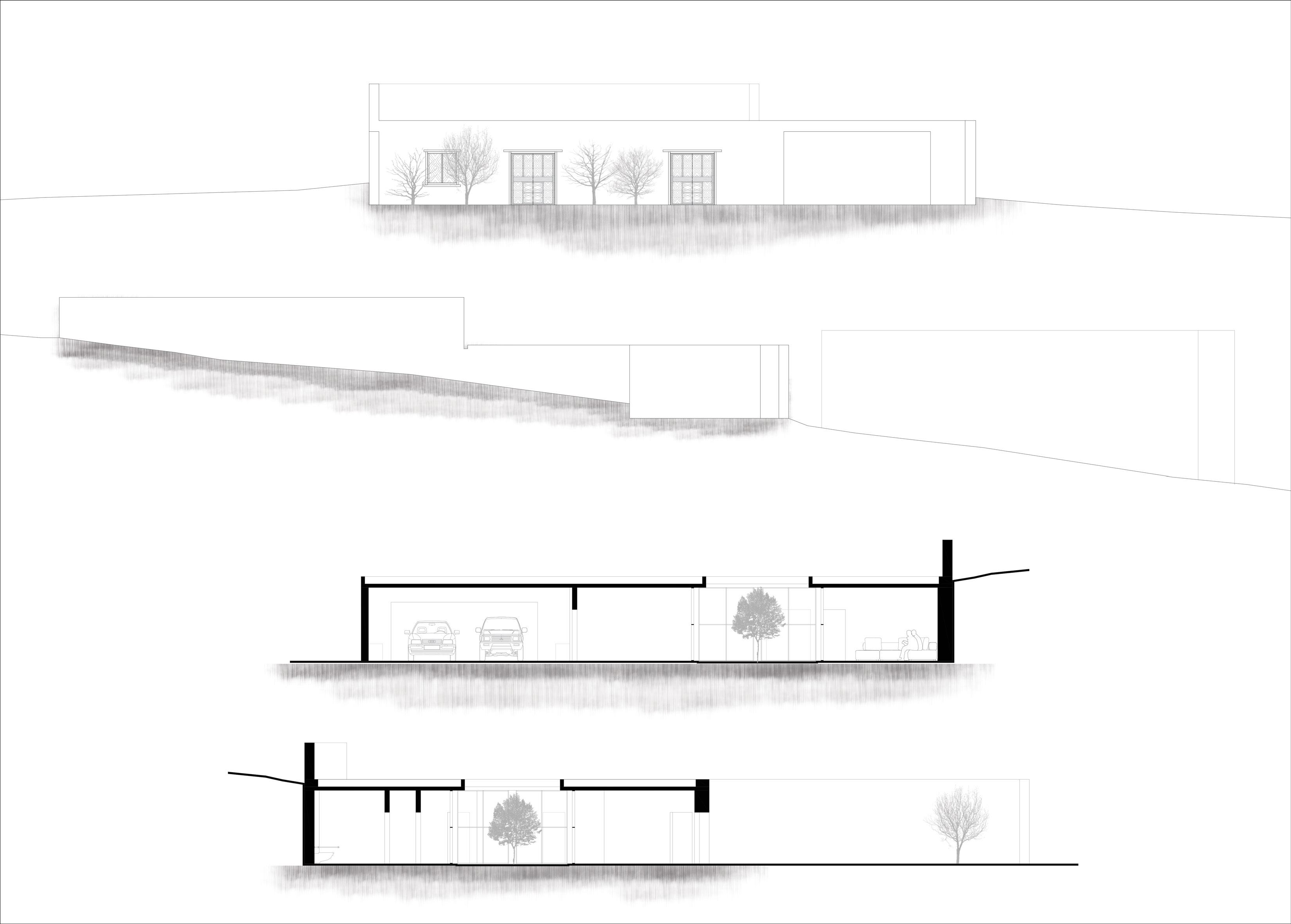

“The house aims to be a palace for its users, affirming this noble character through extreme simplicity in its organization and a rigorous traditional construction of its volume. In this way, on the outside, the house appears as a simple prismatic volume with a square floor plan, 16m on each side, built with walls of Cáceres quartzite stone. On each side there are three window openings, 2.10m in diameter, framed with warm-toned Extremadura granite stone.

Inside, there are nine cubic rooms, each measuring 4.20m on each side, which can accommodate the different uses of the house: living rooms, bedrooms, kitchen and dining room. Among these rooms are located all the house's service spaces such as wardrobes and toilets. Each of the nine rooms is built in two different layers: A lower layer formed by a glass of oak planks, where all the house's installations will be located, and an upper layer formed by a white concrete trough, in which no type of mechanism or lighting system will be located.

Each room opens onto the outside through square oak windows: sliding windows in the wooden base, measuring 2.10m on each side, and motorised windows located in the concrete structure, measuring 1.5m on each side. At the back, framed by the oaks and olive trees, there is an open platform, where people can live outdoors when the weather permits, with a small pool that serves as a swimming pool in summer. On a lower level, with direct access from the street, there is the entire complementary programme of parking, facilities, storage rooms, etc.” - (Tunon Architects,2018)[11].

Kitchen

Bedrooms

Bathrooms

Living Rooms

Laundry Dining Stairs

Garage

“28.0855 is conceived as a multifunctional, recreational, restful, and contemplative space where residents experience a direct connection with nature and water, where only sensations of tranquility and peace are perceived. The project integrates with its surroundings from the outside, and inside, and the sequence of spaces generates contemplative walks through its central courtyard and interior gardens. Here, the Japanese Onsen begins to manifest, creating relaxation spaces surrounded by water, stones, and gardens, leading to calm and recreation. Towards the interior of the Spa, the primary aspect was the constant pursuit of privacy, necessary according to the space and its use. That is why each of the spaces is turned inwards, creating blind facades with stone boundary walls and endowing the project with its monolithic character.

28.0855 is located in rural development in the Sierra of Tapalpa, Jalisco; from its inception, honesty in design was sought, creating a well-defined narrative guide, along with constant respect for the natural environment, making it an integral part of it. In the rustic estates of Mexican towns, dry stone walls are used for delimitation. VAN VAN Atelier reinterprets this concept by using stone in its walls as the fundamental anchoring material. These are erected and assembled naturally, where each stone harmoniously rests upon the other with angular shapes meeting and fitting together, creating boundaries with the exterior. These boundaries are framed with curves to soften their robustness leaving a reminiscent touch of those limiting walls in the fields. Hence, the project’s name: 28.0855, the atomic weight of Silicon, the predominant element in silica the basis of most stones found in nature” (VAN VAN Atlier, 2023)[12].

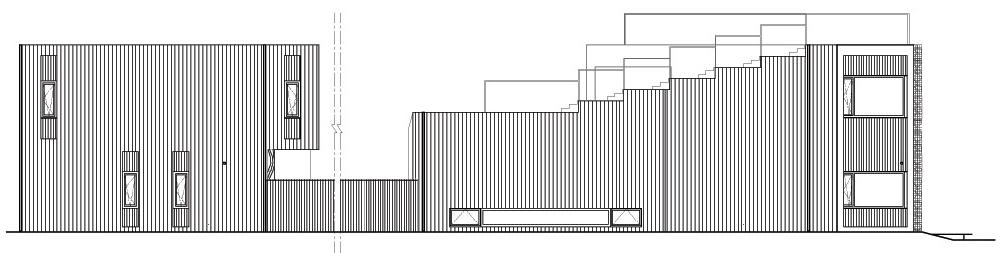

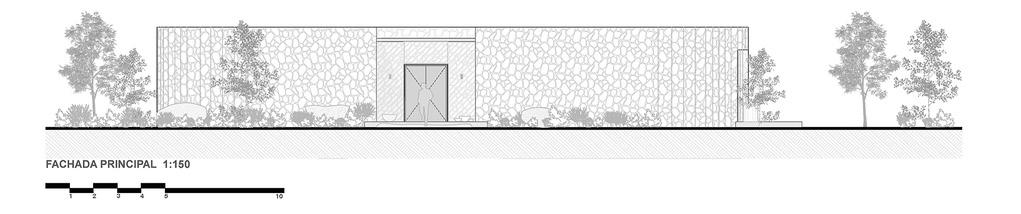

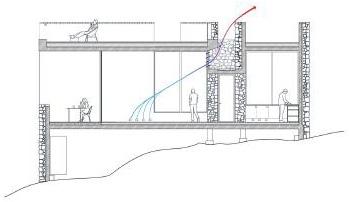

“Located on the western edge of Portugal’s Serra de Sao Mamede, the site offers a slightly overhanging view over the Alentejo plain. A flat alley set between two large granite massifs gives access to the house. It’s extended by a natural ramp at the foot of an imposing rock. The house-studio is perfectly oriented on the North-South axis. Built by local craftsmen, the walls are made of the same granite as the rock on which they stand. There are no lintels on the façades: for each opening, the walls are interrupted all the way to the top, revealing, at constant height, the rim of the upper concrete slab. To preserve the protective presence of the stone, the pipes have been placed inside. Rainwater is collected in a cistern beneath the house” (Antlier Landauer, 2024)[13].

Living Spaces

Kitchen

Bathrooms Stairs

1. Upon examining the selected five precedents, each displays a distinct architectural feature:

2. 017 Stone House: Merges reinforced concrete framing with a traditional stone exterior (Fig. 72).

3. Hanil Visitors Center: Employs an inventive stone application, enclosing large stones within a steel mesh (Fig. 73).

4. Cáceres Stone House: Organized by a strict 16m x 16m grid, forming 9 rooms with cross-cutting views that link each space to at least two exterior vantage points (Fig. 74).

5. Spa 28.0855: Offers continuous interior views framed by integrated green areas such as a courtyard and backyard (Fig. 75).

6. Atelier Landauer Stone House: Features a built-in passive cooling strategy (Fig. 76).

Common Traits

- Use of stone as s structural element.

- Utilization of stone as a tyhermal mass.

- Implementation of a clear lighting strategy.

- Use of a cooling strategy.

- Use reinforced concrete as the main structural system.

- Use of light color palette for interiors (Fig. 77).

- Mixture of wood, concrete, and paint for interiors.

- Creation of directed views for more spatial quality.

- Addressing the users needs based on program.

- Coherent wood, stone, and steel compositions (Fig. 78).

- Contrast between heavy stone finishes and delicate interiors (Fig. 79).

- Use of curtain wall systems, especially for courtyards

- Some analyzed projects are vertical in form (017 Stone House & Atlier Landauer Studio-House)(Fig. 80), while some other projects are horizontal (Spa 28.0855)(Fig.81).

- All analyzed projects appear to be off a city grid.

Throughout history, the Zahran tribe, like many other mountain communities worldwide, has relied on locally available stone to construct their homes and architectural terraces. Stone, being the most accessible material, became the foundation of their traditional building practices.

A typical building crew consisted of at least four builders, each with a specific role. The head builder, known as Albannaa, oversaw the construction process, while the assistant, called Qarari, supported him. At least two additional workers, referred to as Almuhdhirah (meaning “stone bringers”), were responsible for gathering and transporting stone.

The walls were built using a rubble stone technique, forming the primary structural element. The roof was constructed using layers of crossed wooden sticks supported by wooden columns called Al zuffur (plural) or Al zafer (singular). Each column was divided into two main parts: Al zafer (the lower section) and Al Wesad (the upper component). To secure the column in place, stones known as Al Batanah were packed around its base for stability.

This traditional method of construction reflects the Zahran tribe’s adaptation to their mountainous environment, utilizing natural resources efficiently while maintaining a structured and collaborative building process. The roles within the crew, along with the specific terminology for materials and techniques, highlight the cultural and practical knowledge passed down through generations.

Modern stone building techniques have evolved significantly, blending traditional craftsmanship with contemporary engineering and sustainability. Around the world, architects are increasingly revisiting stone as a primary material in residential design, not only for its durability and thermal performance but also for its aesthetic qualities and ecological benefits. A prime example is the Atelier Landauer House-Studio in Portugal, designed by Leopold Banchini Architects. This project showcases how stone can be reimagined in minimalist, modern architecture. The house uses locally sourced limestone in massive blocks, a technique that reduces the need for concrete and steel, minimizing the building’s carbon footprint. The stone walls are not merely cladding but serve as the structural core of the building, emphasizing the solidity and permanence that stone can provide.

This technique reflects a broader trend in modern stone architecture—using stone for load-bearing purposes rather than as a decorative surface.

Globally, similar techniques can be seen in projects like the Stone House by John Pawson in Spain or the House of the Big Arch in South Africa. These homes incorporate thick stone walls for thermal mass, maintaining comfortable indoor temperatures with minimal energy use. Advances in stone-cutting technology, such as CNC milling and dry stone assembly, allow for precision and speed while preserving the tactile quality of natural stone. In many regions, architects are combining stone with glass, wood, and steel to create a dialogue between the ancient and the modern.

This house appears to be a chaotic amalgamation of design elements, producing a jarring and uncoordinated architectural form. While it might attempt to reference the vernacular architecture of Al Baha, it does so with little sensitivity to traditional proportions, composition, or spatial coherence.

Form: The massing of the house is inconsistent with traditional forms. Al Baha vernacular architecture typically relies on compact, cubic stone volumes that emphasize verticality in response to mountainous terrain. In contrast, this house has disjointed masses, with no clear hierarchy or balance. The rooflines clash rather than harmonize, and the transitions between volumes appear arbitrary rather than functional.

Color and Material: Traditional Al Baha houses use locally sourced stone and earthy tones that blend with the natural environment. However, this house uses a confusing palette—possibly a mix of artificial stone veneers, stark whites, or painted surfaces—that dilute the authenticity. The choice of materials lacks the textural richness and tactile honesty of the traditional context. Details and Ornamentation: Any vernacular-inspired details seem forced and disconnected. Rather than integrating traditional patterns or motifs in a meaningful way, decorative elements are pasted onto the surface without contextual justification. This results in a cartoonish representation of tradition rather than a respectful reinterpretation.

Architectural Integrity: The house lacks a coherent language. It reflects a design-by-accumulation mentality, where elements are added for visual impact rather than for cultural or environmental resonance. The result is a superficial and confused reference to tradition.

2. Superficial Imitation of Traditional Architecture

Compared to Fig. 82, this building makes a clearer attempt at mimicking the appearance of Al Baha’s vernacular architecture. However, it still suffers from a lack of depth in understanding the principles that underlie traditional forms.

Form: The silhouette of the building seems more ordered, with defined volumes and a central tower-like mass that vaguely resembles the defensive stone towers characteristic of the region. Despite this, the proportions are exaggerated or misapplied. The verticality is overstated, and the massing seems more theatrical than functional.

Color and Material: This building does a slightly better job in using a muted, stone-like material palette. However, on closer inspection, the surface treatments may still be synthetic or merely cladding. True vernacular architecture would feature thick stone walls, not thin veneers. The imitation here is skindeep—it attempts to simulate appearance without adopting traditional construction logic.

Details and Ornamentation: This building includes elements that resemble traditional wooden lintels, small window openings, and perhaps defensive slits. However, these are likely decorative rather than functional. The traditional architectural language is used as an aesthetic toolkit, not as a spatial or climatic strategy. Architectural Integrity: While more disciplined than Fig. 82, this building still fails to internalize the environmental, social, and cultural rationale behind Al Baha architecture. The imitation remains on the surface; it lacks the thermal mass, spatial organization, and material authenticity of the original.

Both houses fall short of meaningfully engaging with Al Baha’s rich architectural heritage. The house in Fig. 82 is more problematic due to its incoherent composition and lack of stylistic discipline. The house in Fig. 83, while visually more cohesive, still misrepresents tradition by reducing it to surface decoration. True vernacular architecture is not a style to be mimicked—it is a system of building rooted in place, material, and culture. Without understanding these roots, attempts at imitation risk undermining the very authenticity they aim to celebrate.

Why Stone, and Why Housing?

The choice of stone as a primary material stems from Al Baha’s historical and geographical context. Throughout history, the people of this mountainous region relied on stone construction due to its abundance and durability. However, with Saudi Arabia’s rapid urbanization and the widespread adoption of reinforced concrete, traditional stone architecture has gradually faded. This shift has led to a disconnect between the region’s architectural identity and contemporary building practices. Housing, in particular, demands urgent attention because it represents Al Baha’s most pressing architectural challenge.

The current housing situation reflects a troubling contrast—between the region’s strong architectural heritage and the diluted, often incongruous mix of modern styles. This disparity calls for an immediate and rigorous design response. Without intervention, the erosion of cultural identity in residential architecture risks becoming irreversible. By revisiting stone construction, not as a nostalgic gesture but as a sustainable and culturally rooted solution, we can address both the practical and symbolic dimensions of Al Baha’s housing crisis. The goal is to create homes that honor tradition while meeting contemporary needs, ensuring architectural continuity in a rapidly changing landscape.

Thesis Project Goal

This thesis aims to design three residential villas across Al Baha, rooted in vernacular architectural principles. By analyzing surviving vernacular structures and case studies, the project establishes design criteria to create contemporary homes that respectfully reinterpret local heritage while addressing modern needs.

Program

3 Residential Villas: Courtyard

5 Bedrooms

2 Living Rooms

Kitchen

Dining Room

Kitchenette

2 Guest Rooms

Circulation Multiplier Total

sqft

Vernacular Window

Re-shaped Window

Guest Spaces

Public Spaces

Private Spaces

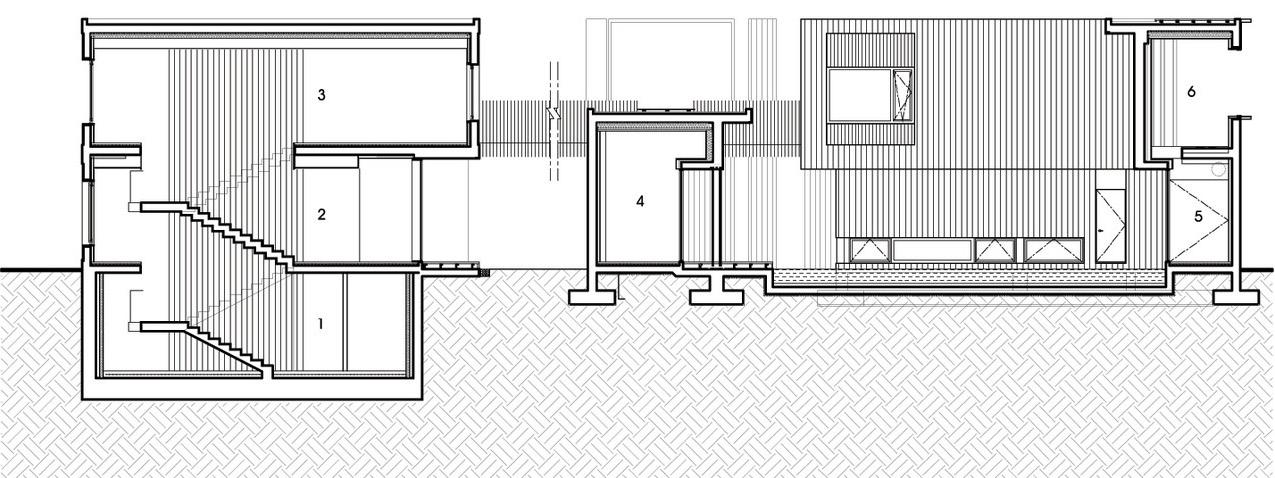

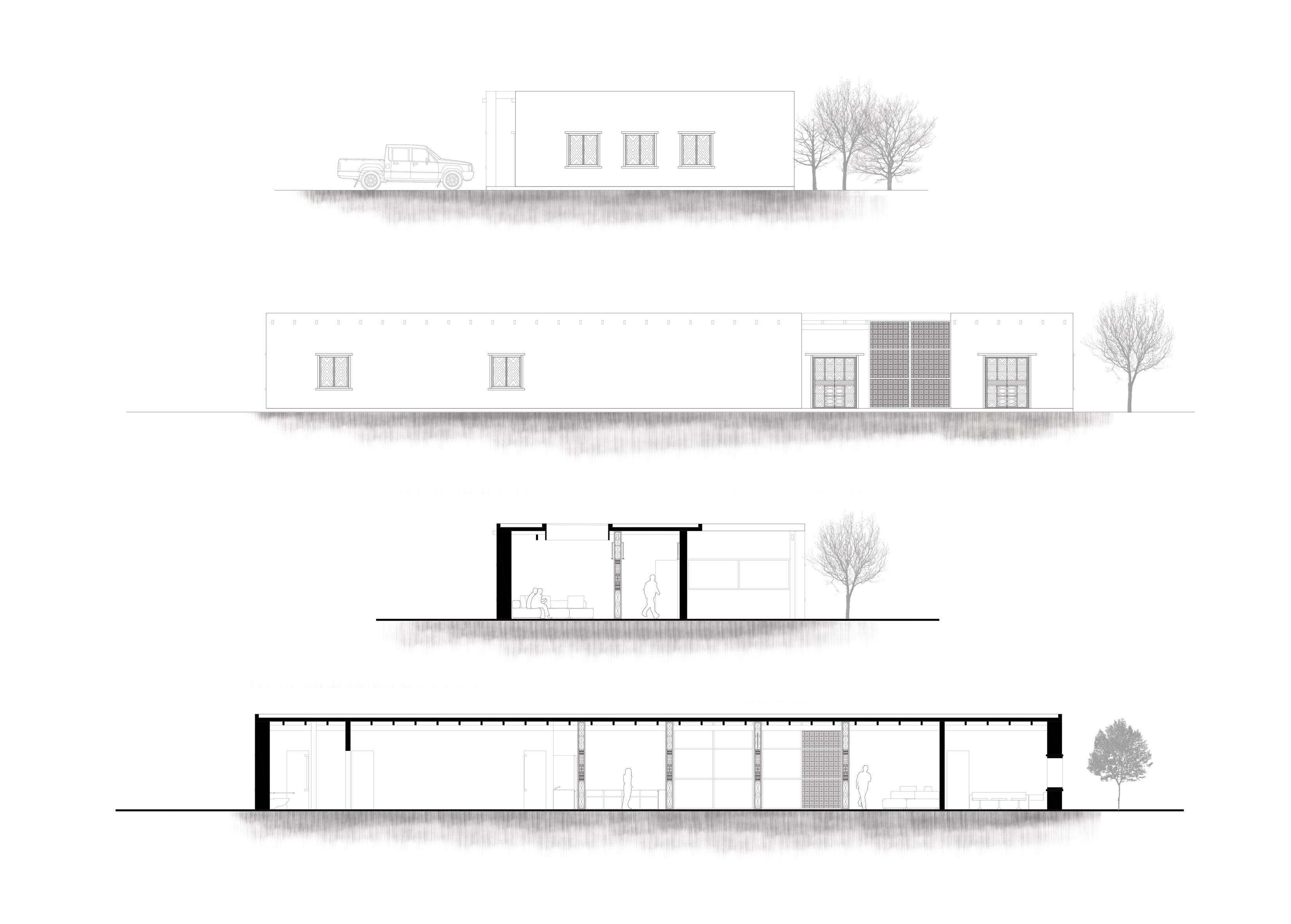

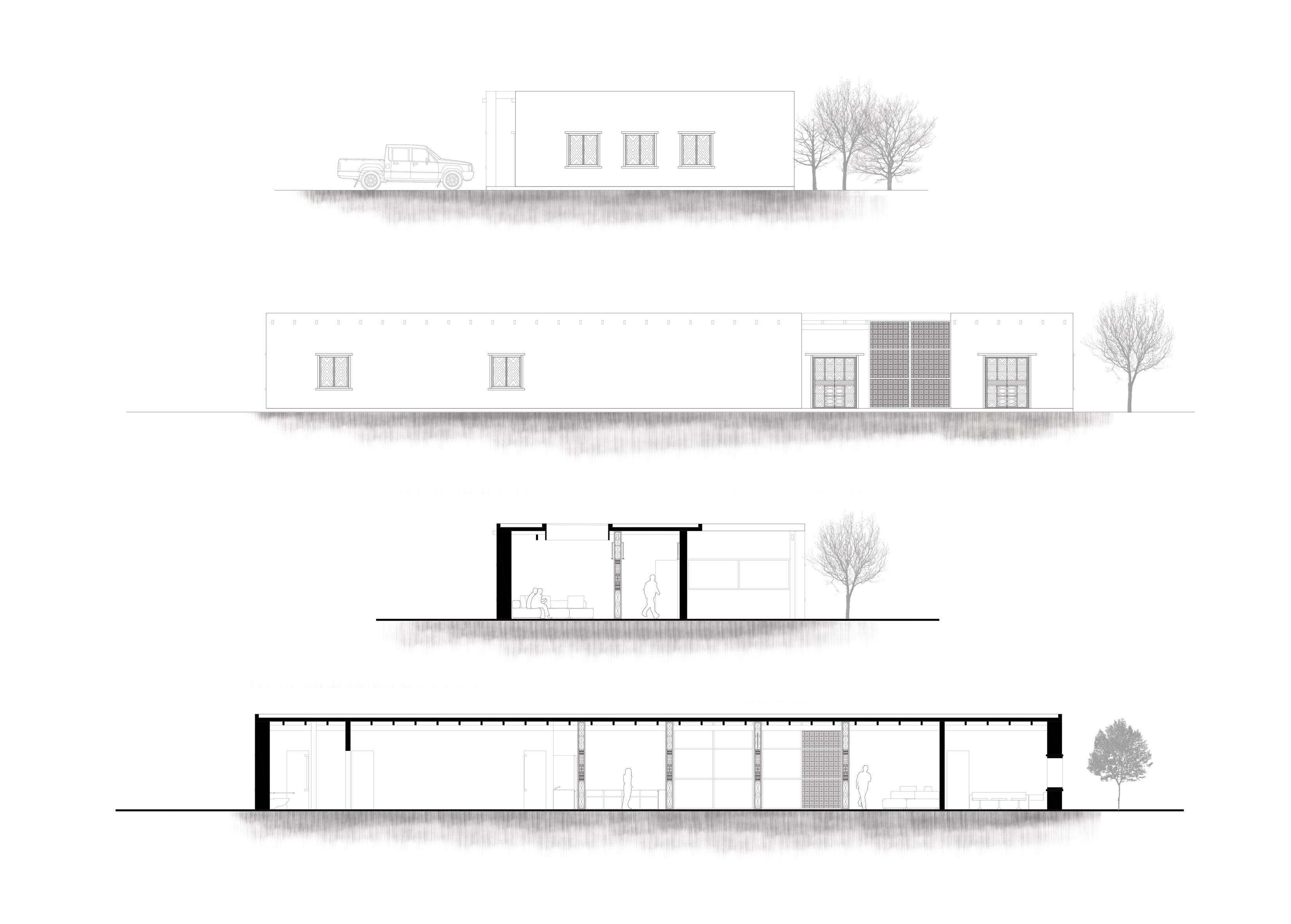

Al Jellah House is the first of three exploratory projects developed as part of a thesis that proposes a structured methodology for reinterpreting architectural heritage. Rather than relying on superficial replication or eclectic formal gestures, this project establishes a critical framework that merges local identity with contemporary spatial and material logic.

Set in a culturally rich but climatically challenging environment, Al Jellah House begins with an analytical extraction of traditional spatial configurations and construction techniques. These elements are not mimicked but abstracted—transformed through a process of reinterpretation that respects their cultural and environmental logic. Key strategies include the use of load-bearing stone walls, an inward-facing courtyard, and a spatial hierarchy that separates private, semi-private, and public domains, all derived from regional domestic typologies.

The project is developed through a phased design methodology: identifying key site and typological elements, reimagining spatial relationships, and finally articulating the architectural form. The resulting design features a robust stone envelope that protects and defines interior spaces, while a central courtyard brings light, ventilation, and communal focus to the home. Each functional zone—such as the women’s and men’s majlis, guest quarters, and private family areas—is organized to reflect social customs while providing comfort and adaptability.

By embedding contextual research into each design decision, Al Jellah House serves as a prototype for contemporary architecture that evolves from tradition rather than overwriting it. It represents not just a building, but a critical position on how architects might ethically and creatively build within heritage contexts. This thesis argues that true architectural progression arises from careful study, respectful reinterpretation, and a deep understanding of place

Guest Spaces

Public Spaces

Private Spaces

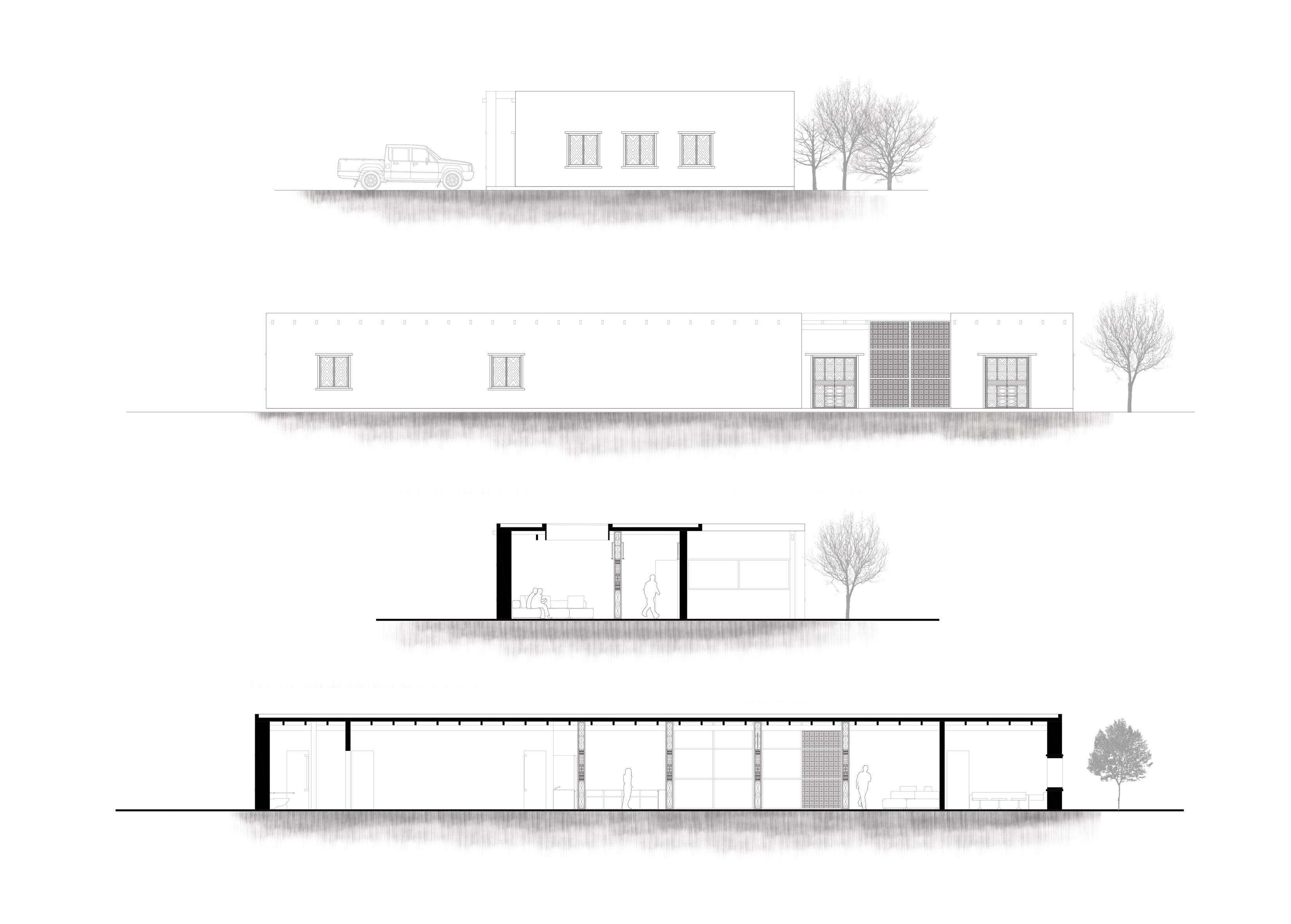

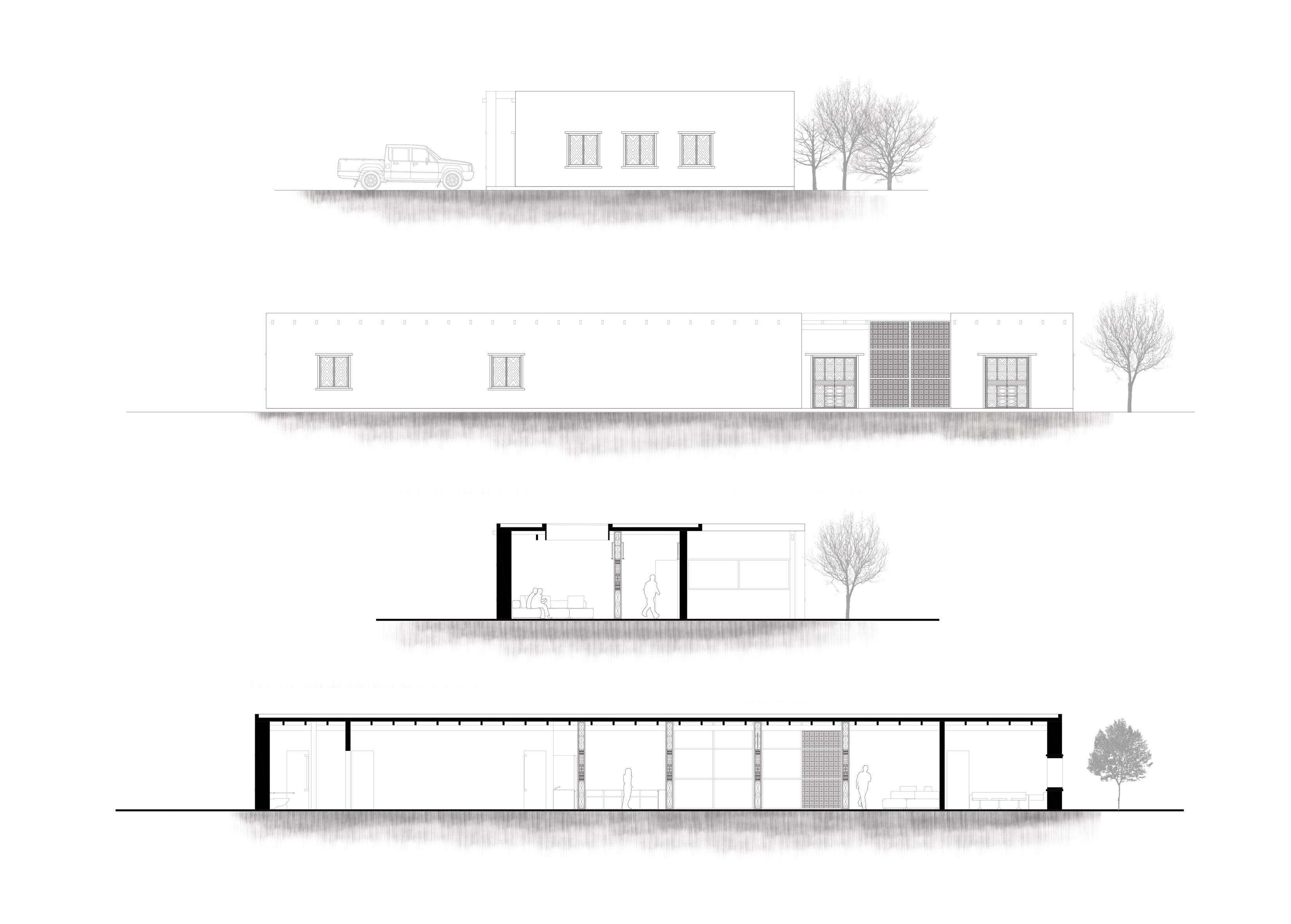

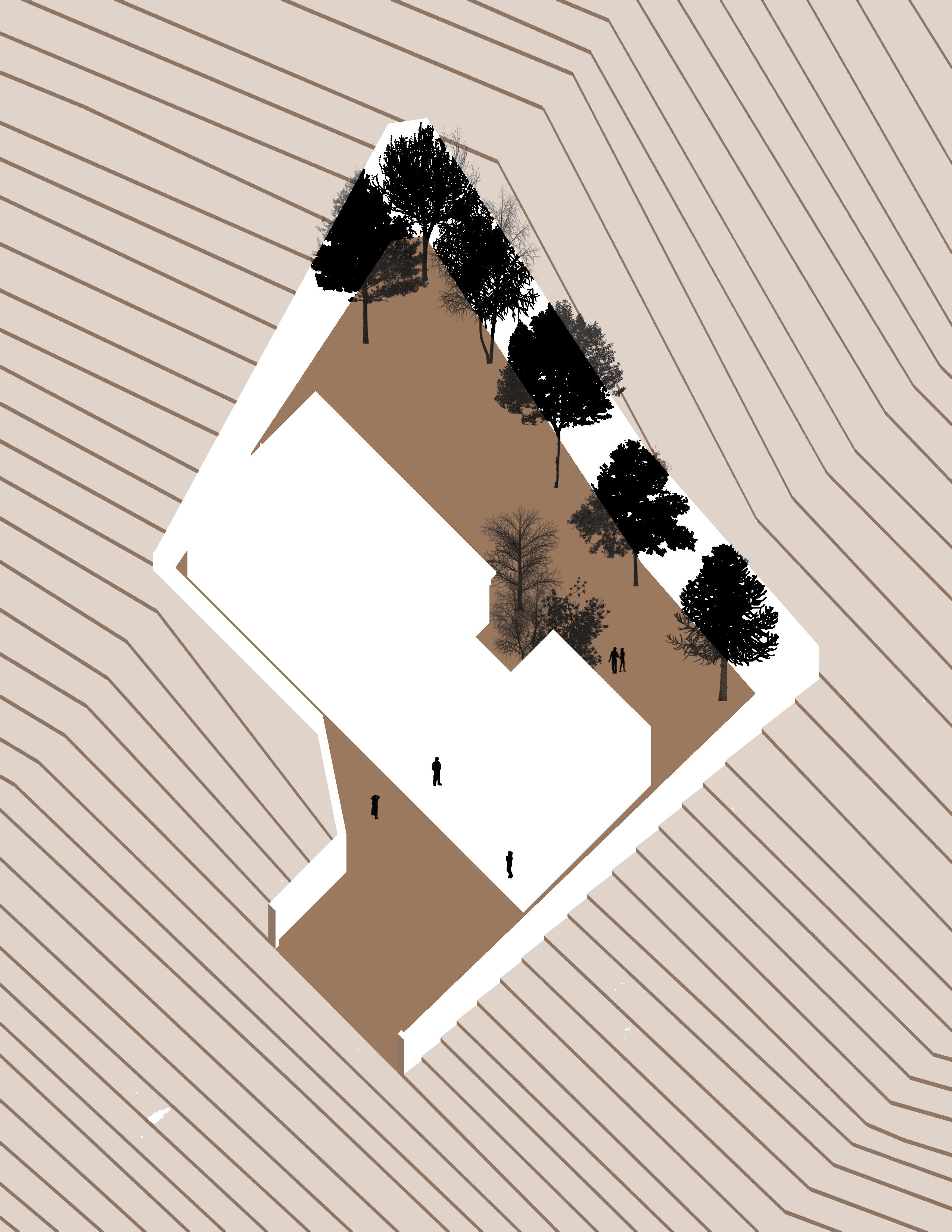

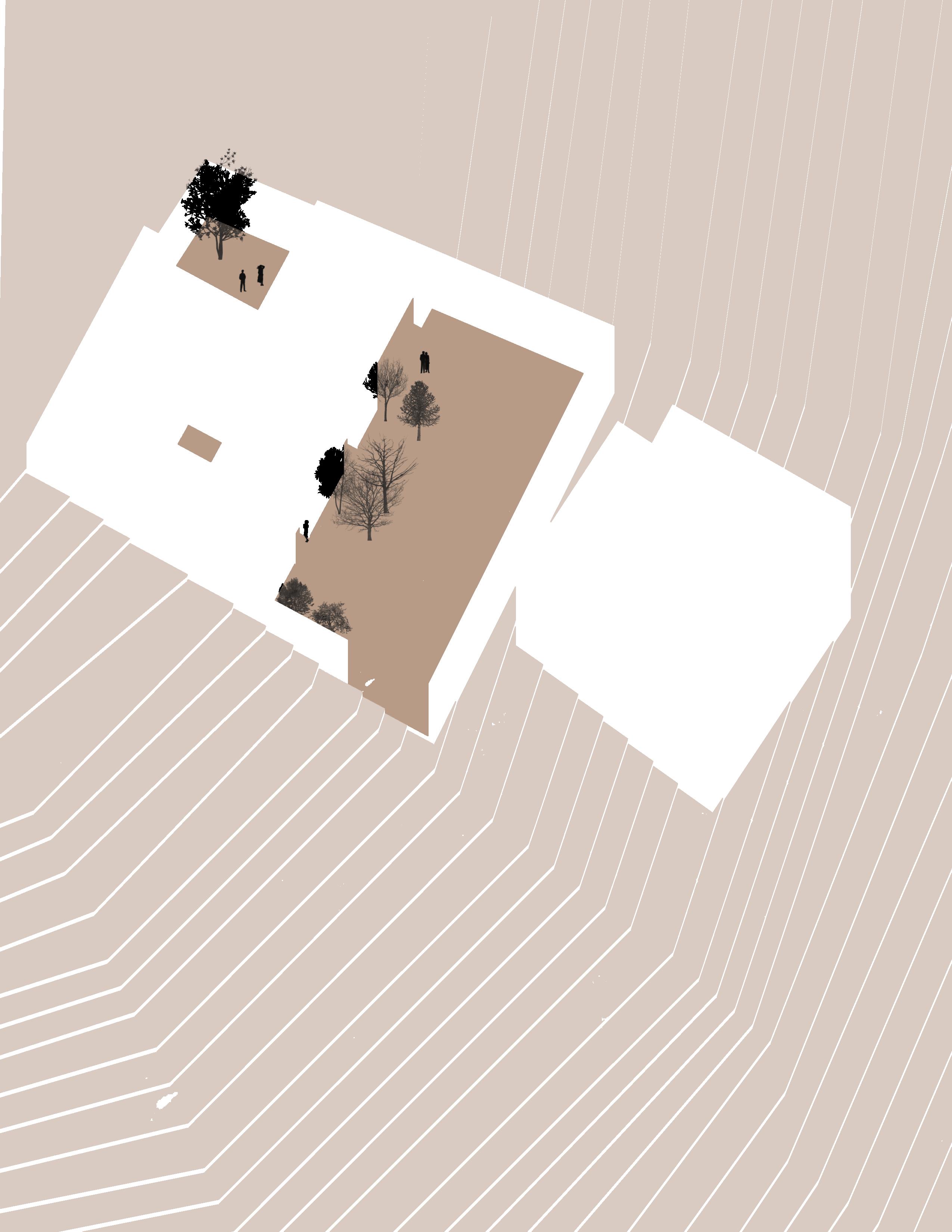

Bakkarah House is the second installment in a trilogy of architectural explorations aimed at reinterpreting heritage through a structured and analytical design methodology. Rooted in the thesis’s overarching framework, this project advances the investigation by applying regional typologies and material logic to a complex residential program, emphasizing the layered relationships between public, semi-private, and private spaces.

The design begins with a critical extraction of vernacular architectural elements from the site’s cultural and environmental context. Through a series of methodical design phases—site analysis, formal extraction, spatial extrusion, wall definition, and form refinement—the house takes shape as a reinterpretation of traditional stone dwellings. The process refrains from literal mimicry; instead, it distills the spatial essence of heritage forms and reimagines them using contemporary design sensibilities.

The architectural composition is centered around a private courtyard, which functions as a climatic and social anchor. Surrounding this void, programmatic zones are articulated with careful hierarchy: the guest reception areas (including separate majlis spaces for men and women) are placed toward the front, while private family functions—including multiple bedrooms and a master suite—are nested deeper within the structure and extended vertically onto a second floor.

Thick stone walls, a hallmark of local building traditions, define the structure’s perimeter and serve both as climatic buffers and symbolic thresholds. Modern mechanical, electrical, and service areas are integrated discreetly to uphold the purity of spatial experience.

Bakkarah House demonstrates how contextual sensitivity, when paired with analytical design strategies, can yield a contemporary architecture that is both culturally grounded and forward-looking. It builds on the thesis’s central claim: that meaningful architectural evolution emerges not from nostalgia, but from critical engagement with place, tradition, and progressive spatial thinking.

5. Final Form

Exterior Stone Walls

Guest Spaces

Public Spaces

Private Spaces

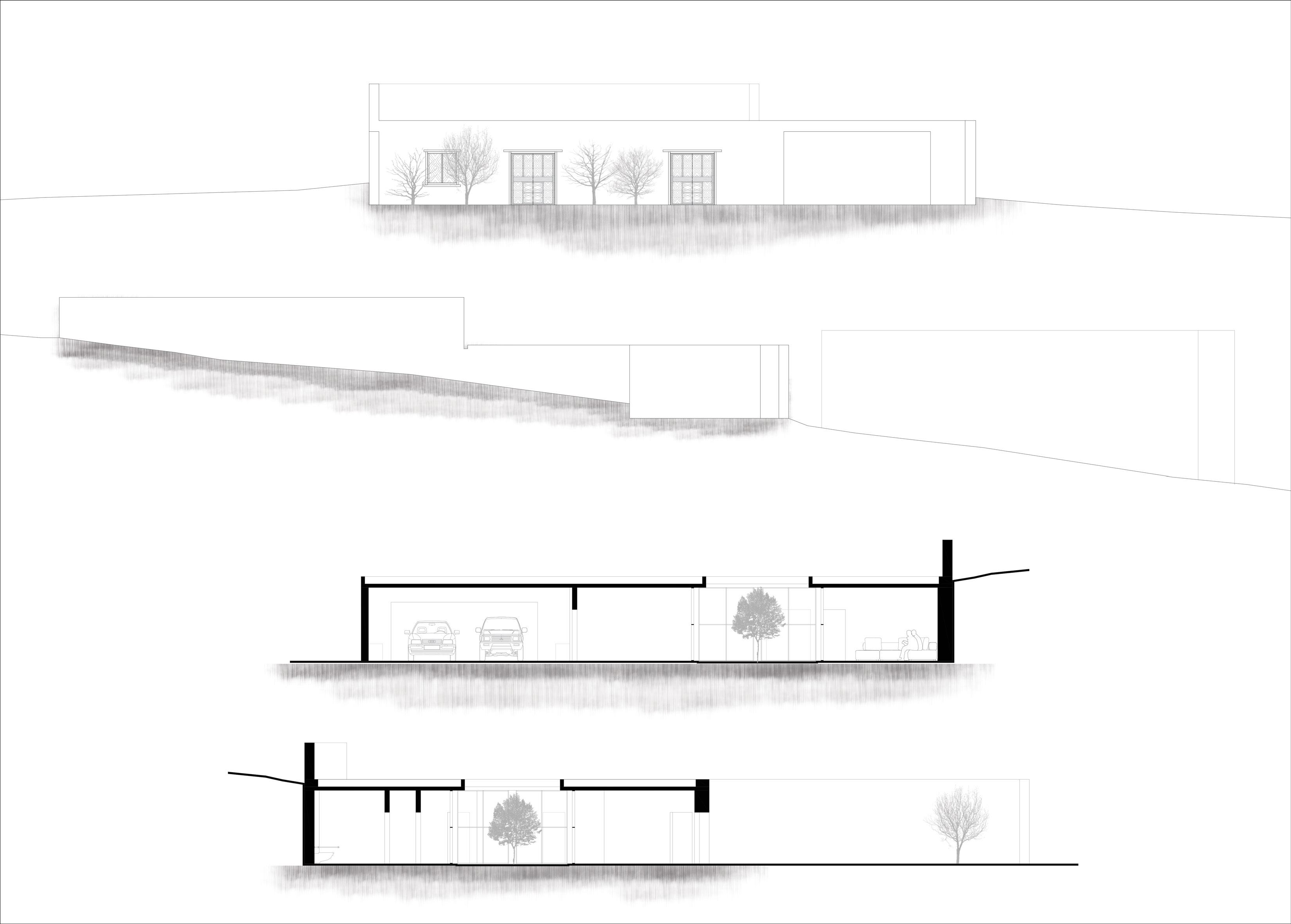

Jradaan House completes the trilogy of design investigations in this thesis, offering a nuanced response to the reinterpretation of architectural heritage through systematic analysis and thoughtful transformation. Serving as both a culmination and refinement of the research methodology, the project synthesizes the lessons learned from earlier iterations and pushes the spatial language toward greater formal clarity and cultural relevance.

The design process follows a consistent methodology—beginning with site study, formal and typological extraction, volumetric extrusion, and spatial refinement. Jradaan House, like its predecessors, uses the courtyard as the core organizational element, serving both environmental and social functions. However, this iteration introduces greater fluidity between zones and emphasizes the integration of private and semi-private spaces through carefully choreographed transitions.

The spatial program balances family privacy with hospitality, a key cultural value in the region. The layout includes distinct zones for men’s and women’s majlis, guest areas, and a well-defined family core, including multiple bedrooms and private bathrooms. The backyard, garage, and service spaces are seamlessly embedded into the massing without compromising the design’s conceptual rigor.

Materially, the house remains faithful to the thesis’s emphasis on thick exterior stone walls, which perform thermally while visually rooting the project in its local context. The architectural vocabulary maintains a minimalist clarity while referencing traditional domestic forms, avoiding literal historic replication.

As the third case study in the thesis, Jradaan House represents the most resolved expression of the research. It demonstrates how deep contextual engagement—combined with structured design analysis—can result in architecture that is simultaneously grounded in tradition and responsive to contemporary needs. Through this project, the thesis reaffirms its central argument: heritage can be a foundation for innovation, not a boundary to it.

Summary

This thesis presents a structured methodology for reinterpreting architectural heritage through three exploratory projects. Rather than engaging in superficial imitation or uncontextualized stylistic blending, the research establishes a systematic approach to architectural evolution—one that respects cultural identity while embracing contemporary design thinking. The methodology emphasizes deep analysis of local heritage, comparative study of global precedents, and critical evaluation of unsuccessful attempts to ensure meaningful architectural progression.

The three Projects begin with a deep investigation of traditional domestic forms within a specific environmental and cultural context. Through this process, vernacular strategies—such as thick stone walls, introverted courtyards, and social spatial hierarchies—are not replicated but reimagined. The design process is intentionally iterative and analytical, progressing through phases of extraction, spatial organization, and formal refinement to generate responsive architectural solutions.

Al Jellah House sets the foundation, introducing a strong organizational core around a central courtyard and establishing clear public-private transitions. Bakkarah House expands the thesis’s complexity by introducing a vertical spatial organization and emphasizing layered programmatic relationships. Jradaan House synthesizes the methodology into a refined and adaptive structure, offering the most integrated balance between cultural resonance and contemporary living.

Materiality across all three projects reinforces this continuity, with stone used as both a symbolic and performative element. While each design is site-specific and functionally distinct, all share a disciplined architectural language shaped by heritage yet oriented toward the future.

Together, these three houses form a cohesive architectural argument: that tradition can be a rich source of innovation when approached with intention, analysis, and respect. This thesis advocates for an architec-

The foundation of this approach lies in a multi-layered examination of Al Baha’s architectural heritage. The study begins with an investigation of primary structural and spatial elements—those fundamental components that define the region’s built identity. These include load-bearing systems, spatial organization, and material traditions that have historically shaped the architectural language of the area.

Following this, the research identifies secondary architectural elements—features such as fenestration patterns, transitional spaces, and structural detailing—that contribute to the nuanced character of local buildings. By distinguishing between primary and secondary elements, the methodology ensures that reinterpretation maintains the essential spirit of the heritage while allowing flexibility in adaptation.

The third stage focuses on ornamental and decorative aspects, examining how traditional motifs can be abstracted or reimagined rather than directly replicated. This step is crucial in avoiding pastiche while preserving cultural symbolism. The research then extends beyond local context by analyzing global architectural precedents that utilize rough stone as a dominant exterior material. Projects such as [insert relevant examples] provide insights into material innovation, tectonic expression, and contextual sensitivity, offering valuable lessons for contemporary adaptations of heritage.

Finally, the study critically assesses unsuccessful examples of heritage reinterpretation, identifying common pitfalls such as tokenistic ornamentation, disproportionate scaling, or dissonant material choices. This evaluative process serves as a safeguard against repeating past mistakes, reinforcing the need for a thoughtful, research-driven design approach.

Architecture, like culture, is never truly finished; it evolves through experimentation, adaptation, and sometimes, necessary reinvention. The projects acknowledge this reality by presenting flexible frameworks rather than rigid solutions. They demonstrate that heritage-inspired design should be an evolving dialogue—one that balances respect for tradition with the necessity of innovation. The “final product” is less important than the mindset it fosters: one that values depth over decoration, intentionality over imitation, and evolution over stagnation.

The three projects developed in this thesis are not presented as definitive solutions but as initial iterations in an ongoing design discourse. Their significance lies in the methodological framework they establish—one that prioritizes critical thinking and iterative refinement over fixed aesthetic outcomes. By treating architectural heritage as a dynamic continuum rather than a static artifact, the research opens avenues for continuous improvement and reinterpretation.

The novelty of this approach is its emphasis on structured analysis rather than stylistic replication. Each design decision—from material selection to spatial configuration—is subjected to rigorous evaluation, ensuring that the resulting architecture remains rooted in tradition while responding to contemporary needs. This process-oriented mindset allows for infinite variations and refinements, acknowledging that architectural evolution is an ever-unfolding dialogue between past and present.

The methodology proposed in this thesis has broader implications for architectural practice, particularly in regions where rapid modernization threatens to erode cultural identity. By demonstrating how heritage can be reinterpreted without resorting to pastiche, the research provides a replicable model for designers working in similar contexts. Future explorations could expand on this foundation by incorporating advanced digital modeling, sustainable material innovations, or community-based participatory design—further enriching the conversation on heritage adaptation.

This thesis establishes a critical framework for engaging with architectural heritage—one that moves beyond surface-level imitation toward a more profound, analytical reinterpretation. Through systematic study of local and global precedents, coupled with reflective evaluation of past failures, the research advocates for an architecture that is both culturally resonant and progressively innovative. The three projects serve as preliminary explorations, inviting further development and refinement. Ultimately, the work underscores the importance of process-driven design, where the journey of critical inquiry holds as much value as the architectural outcomes themselves. By fostering this mindset, the thesis contributes to a more thoughtful and sustainable evolution of built heritage.

The primary objective of this thesis was to initiate a critical discourse on how architects and designers should engage with the ongoing evolution of architectural heritage. Rather than resorting to superficial imitation or haphazardly blending global and local styles, the project advocates for a more deliberate and analytical methodology. The three design proposals presented here serve as preliminary explorations—initial iterations in what should be an ongoing, iterative process. Their value lies not in being definitive solutions but in demonstrating a framework for continuous reassessment and refinement.

Each project was developed with the understanding that architectural heritage should not be treated as a static artifact to be copied but as a living tradition that must adapt to contemporary needs. The emphasis was placed on systematically evaluating every design decision—questioning whether a particular approach genuinely contributes to a meaningful evolution of heritage or if alternative strategies should be pursued. This process of constant re-evaluation ensures that design choices are intentional, culturally resonant, and architecturally coherent rather than arbitrary or trend-driven.

The significance of this thesis lies not in the final architectural outcomes but in the methodological approach itself. By prioritizing critical analysis over aesthetic replication, the projects challenge conventional practices in heritage-based design. The proposed strategies—such as deconstructing traditional elements, studying materiality in a global context, and learning from past failures—open up infinite possibilities for further development. The designs are not endpoints but starting points, inviting future architects to build upon, critique, and refine them.

This thesis does not claim to have all the answers but instead seeks to ask the right questions. How can we reinterpret heritage without losing its essence? How can global influences enrich rather than dilute local identity? By proposing a structured yet adaptable methodology, the projects encourage future designers to engage with these questions rigorously. The hope is that this work inspires further research, debate, and experimentation—ultimately leading to architecture that is both culturally meaningful and dynamically progressive. The conversation has only just begun.

[1]: Eben Saleh, Mohammed Abdullah. Transformation of the traditional settlements of southwest Saudi Arabia, Planning Perspectives. (1998). 13:2, 195-215, DOI: 10.1080/026654398364527. https://doi. org/10.1080/026654398364527

[2]: Zee Ain Heritage Village in Al-Baha Region. UNESCO World Heritage Convention, April 8, 2015. http://whc. unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6031/.

[3]: Baabdullah, Renad. Traditional Domestic Architecture in Al-Baha Region. Effat Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. (2020). https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/eurj/vol1/iss1/7

[4]: Eben Saleh, Mohammed Abdullah. The symbolism of landmarks in traditional settlements and wilderness of the Arabian Peninsula, Building and Environment. Volume 31, Issue 3. (1996). Pages 283-297. ISSN 0360-1323, https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-1323(95)00052-6

[5]: Mohamed, Mahmoud. “Communication with architectural heritage in a contemporary style in the Islamic region of Saudi Arabia.” bab Journal of FSMVU Faculty of Architecture and Design 1.2 (2020): 161-183.

[6]: Eben Saleh, Mohammed Abdullah. “Alckas: the urban pattern of a traditional settlement in south-western Saudi Arabia.” Urban Design International 2.2 (1997): 93-107.

[7]: Eben Saleh, Mohammed Abdullah. From Symbolism to Functionalism and Back Again: Towers of Traditional Settlements in the Arabian Peninsula, Architectural Science Review, 39:1, 25-37, (1996). DOI: 10.1080/00038628.1996.9697354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.1996 .9697354

[8]: Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, Deputy Ministry of Town Planning, Architectural Heritage of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Between Authenticity and Contemporality, 2010.

[9]: Herzog & de Meuron. 1988. H&dM https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/017-stone-house/

[10]: BCHO Architects. Archdaily. 2009. https://www.archdaily.com/72484/hanil-visitors-center-guest-housebcho-architects

[11]: Tuñón, Emilio, & Albornoz, Carlos. ArchDaily. 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/907251/stone-houses-in-caceres-tunon-arquitectos

[12]: VAN VAN Atlier. ArchDaily. 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

[13]: Atlier Landauer. Divisare. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Fig. 1: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 2: Saudi Tourism. 2020 Available: http://sauditourism.sa/en/ExploreKSA/AttractionSites/DheeAyn/Pages/default.aspx.

Fig. 3: AbdulAziz Mousa. 202. Via email

Fig. 4: AbdulAziz Mousa. 202. Via email

Fig. 5: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 6: Saudi Tourism. 2020 Available: http://sauditourism.sa/en/ExploreKSA/AttractionSites/Pages/default.aspx.

Fig. 7: Saudi Tourism. 2020 Available: http://sauditourism.sa/en/ExploreKSA/AttractionSites/Pages/default.aspx.

Fig. 8: Saudi Tourism. 2020 Available: http://sauditourism.sa/en/ExploreKSA/AttractionSites/Pages/default.aspx.

Fig. 9: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 10: Baabdullah, Renad. Traditional Domestic Architecture in Al-Baha Region. Effat Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. (2020). https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/eurj/vol1/iss1/7

Fig. 11: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 12: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 13: Eng. Abdulkarim Al Ghamdi. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 14: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 15-24: Herzog & de Meuron. 1988. H&dM https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/017-stone-house/ Fig. 25-34: Yong Gwan Kim. 2009. https://www.archdaily.com/72484/hanil-visitors-center-guest-house-bcho-architects

Fig. 35-49: Tuñón, Emilio, & Albornoz, Carlos. ArchDaily. 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/907251/stone-houses-in-caceres-tunon-arquitectos

Fig. 50-58: César Béjar 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

Fig. 59-71: Tiago Casanova. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Fig. 72: Herzog & de Meuron. 1988. H&dM https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/projects/017-stone-house/

Fig. 73: Yong Gwan Kim. 2009. https://www.archdaily.com/72484/hanil-visitors-center-guest-house-bcho-architects

Fig. 74: Tuñón, Emilio, & Albornoz, Carlos. ArchDaily. 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/907251/stone-houses-in-caceres-tunon-arquitectos

Fig. 75: César Béjar 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

Fig. 76: Tiago Casanova. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Fig. 77: César Béjar 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

Fig. 78: César Béjar 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

Fig. 79: Tiago Casanova. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Fig. 80: Tiago Casanova. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Fig. 81: César Béjar 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/1016400/house-2855-van-van-atelier

Fig. 82: Mansour Alzahrani. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 83: Mansour Alzahrani. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 84: Ahmed Salem. 2024. Via Email

Fig. 85-86: Tiago Casanova. 2024. https://divisare.com/projects/512859-atelier-landauer-tiago-casanova-house-studio

Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom. “15. Architecture under the Ottomans after the Conquest of Constantinople.” The Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250–1800 by Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom, Yale University Press, 1994. A&AePortal, aaeportal.com/?id=-15674.

Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom. “7. Architecture in Egypt, Syria, and Arabia under the Circassian Mamluks (1389–1517).” The Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250–1800 by Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom, Yale University Press, 1994. A&AePortal, aaeportal.com/?id=-15666.

Christensen, Peter H. “7. Monuments.” Germany and the Ottoman Railways: Art, Empire, and Infrastructure by Peter H. Christensen, Yale University Press, 2017. A&AePortal, aaeportal.com/?id=-20725.

Fadl MA, Al-Yasi HM, Alsherif EA. Impact of elevation and slope aspect on floristic composition in wadi Elkor, Sarawat Mountain, Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep. 2021 Aug 9;11(1):16160. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95450-4. PMID: 34373469; PMCID: PMC8352965.

Fonseca, Rory. “Building in Egypt: Pharaonic Stone Masonry [by] Dieter Arnold.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 51, no. 2, June 1992, pp. 214–16. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=bvh&AN=330313&site=ehost-live.

L. Dipasquale, L. Rovero, Fabio Fratini, 15 - Ancient stone masonry constructions. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering, Nonconventional and Vernacular Construction Materials (Second Edition),

Salerno, G et al. Stone-masonry new constructions: science and history in the service of beauty and environment. 2010. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000320604900022

Eben Saleh, Mohammed Abdullah. The symbolism of landmarks in traditional settlements and wilderness of the Arabian Peninsula, Building and Environment. Volume 31, Issue 3, 1996. Pages 283-297. ISSN 0360-1323, https:// doi.org/10.1016/0360-1323(95)00052-6