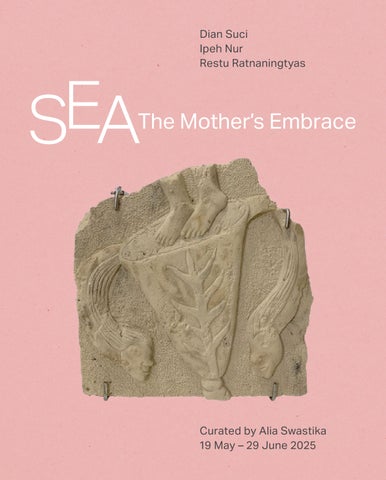

Curated by Alia Swastika

19 May – 29 June 2025

This catalogue is published in conjunction with Sea: The Mother’s Embrace, a group exhibition by Dian Suci, Ipeh Nur, Restu Ratnaningtyas. Curated by Alia Swastika, held at A+ WORKS of ART, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia from 19 May to 29 June 2025.

The maritime project was first developed for the 2025 Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry, for Alia Swastika’s section, Rosestrata were on display in Sharjah from 6 February to 15 June 2025.

Pantura, the northern coast of Java is a significant locus in the history of colonialism and this becomes our starting point of exploring maritime culture in this project. Travelers’ accounts show how major ports that opened up cultural exchange and trade routes were built in several cities across this region; Tuban, for one, was a major port in the early period of foreign entry into Java. Lasem, for example, is known as a city with an advanced culture due to the growth of marine ecosystems in the late 16th century and beyond. This area is still a center for vernacular maritime knowledge passed down for centuries. This region also marks the institutionalization of Islam as a center of power, with the establishment of the first Islamic kingdom in Demak. But now we witness how the region is deeply threatened by massive ecological shifts that endangered the life of the community there.

As we embark on this complex and diverse narrative, female figures from Pantura have significantly influenced our journey. Ratu Shima ruled the kingdom of Jepara in the 6th century, marking a governance system that prioritized the people’s welfare. Later, in the 16th century, Ratna Kencana, known as Ratu Kalinyamat, brought Jepara into a new era of prosperity in trade, ports, and maritime traffic, as well as the economy of its people. RA Kartini emerged from a generation that deeply explored modern thought and the power of emancipation to challenge gender-based social role disparities. Among the three, RA Kartini was designated by the state as a symbol of “women’s emancipation” and became closely associated with the maternal politics of the New Order period. In 2022, Ratu Kalinyamat was also recognized as a national hero, indicating that the strength of women, illustrated through various influential figures across different time periods, has evolved into myths embraced by the community, both consciously and unconsciously, whilst being shaped by complex political dynamics within the state.

As we explore the villages along the Pantura coast, we are confronted with the reality that women are still far from achieving positions that guarantee justice. While women demonstrate remarkable strength as the primary economic support for their families, protection and support for equality remains elusive.

The three artists in the Maritime project, Ipeh Nur, Restu Ratnaningtyas and Dian Suci, presented at the Sharjah Biennale do not all come from coastal areas; instead, their detachment from this culture has led them to uncover unexplored narratives or even pose unanswered questions. Beyond that, exploring the nearby coastal areas, just three hours from Yogyakarta, where the artists reside, becomes a way to share interpretations of a “theme” or a “story,” allowing each to develop new narrative threads based on their knowledge and unique perspectives within a specific social reality. From the narrative of everyday practice, women’s role in the domestic and economic system and spirituality connection to the genealogy of the area through archeological traces.

An Invitation to The Unborn

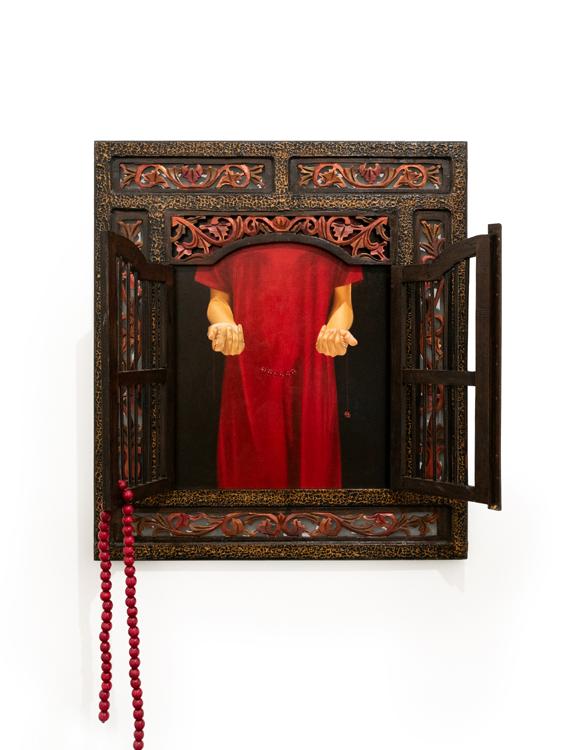

Oil on canvas, window-shaped frame

90 × 80 cm

The Breeze That Hastens the Ship Across the Sea 2025

Watercolour on paper

60 ø cm

The Message of the Immemorial Seed 2025

Watercolour on paper 60 ø cm

Nests of Memories That Shrink From Words 2025

Acrylic on transparent fabrics, carved wooden chests, mordant paste on fabric dyed using natural dyes from plants, wooden beads

Variable dimensions

Whispering Wave Series 2025

Limestone relief

50 × 50 × 4 cm

Whispering Wave Series 2025

Rock powder, yellow ochre, mud eruption, charcoal, red oxide, indigo powder, marble powder, and ceramic on paper

Painting: 85 × 55 × 4 cm

Wood: variable dimension, 114.5 × 50.5 × 22 cm

Whispering Wave Series 2025

Limestone relief

60 × 25 × 8 cm

The discourse surrounding the Indonesian archipelago as a maritime region re-emerged following the Reform era, serving as a mode of criticism towards the New Order policies that were deemed less favorable to coastal communities. Indonesia has the longest coastline in the world, and its marine territory covers two-thirds of the entire archipelago, making it a vital living space that shapes a strong cultural identity. Narratives about maritime culture seemed submerged and forgotten amidst the glorification of inland kingdoms’ history, despite the close relationship between the sea and mountains being an important foundation of Indonesia’s cosmological knowledge. State policies constructed a certain social narrative, marginalizing knowledge, discourse, and collective memory about the sea. Discussions about the ocean have recently become crucial due to climate change and ecosystem threats, where coastal abrasion, degradation, and marine pollution are pressing issues that require collective attention.

In addition to the growing advocacy efforts to preserving marine ecosystems, the exploration of archaeological, anthropological, and historical knowledge, as well as the political economy of the sea, represents a new academic wave that uncovers important narratives that have long been hidden. For example, in the context of rewriting history, the narrative of the Spice Route — which has become a foundation for a movement of maritime cultural history and (post)colonialism — paves the way for efforts to rewrite history and rediscover local knowledge related to the vernacular technology of coastal communities from the pre-colonial period to the present. This articulation of maritime knowledge encompasses various forms, such as film, literature, recipes, songs, textile works, and more.

Why the north coast?

In addition to the growing advocacy efforts to preserve marine ecosystems, the exploration of archaeological, anthropological, and historical knowledge, as well as the political economy of the sea, represents a new academic wave that uncovers important, previously hidden narratives. In the context of rewriting history, the narrative of the Spice Route has become a foundation for a movement of maritime cultural history and postcolonialism, paving the way for efforts to rewrite history and rediscover local knowledge related to vernacular technology of coastal communities from the pre-colonial period to the present. This articulation of maritime knowledge encompasses various forms, including film, literature, recipes, songs, and textile works. The three artists in the Maritime project presented at the Sharjah Biennale do not all come from coastal areas. Still, their detachment from this culture has led them to uncover unexplored narratives or pose unanswered questions. Furthermore, exploring the nearby coastal areas, just three hours from Yogyakarta where the artists reside, becomes a way to share interpretations of a theme or story, allowing each to develop new narrative threads based on their individual knowledge and unique perspectives within a specific social reality.

On the other hand, the northern coast of Java is a significant locus in the history of colonialism. Travelers’ accounts show how major ports that opened up cultural exchange and trade routes were built in several cities across this region; Tuban, for one, was a major port in the early period of foreign entry into Java. Lasem, for example, is known as a city with an advanced culture due to the growth of marine ecosystems in the late 16th century and beyond. This area is still a center for vernacular maritime knowledge passed down for centuries. This region also marks the institutionalization of Islam as a center of power, with the establishment of the first Islamic kingdom in Demak. After that, the kingdom spread its influence eastward to Tuban and beyond. The Wali who spread Islam also primarily operated in cities around the northern coast, and their tombs nestled along the coastline have become pilgrimage magnets to this day.

This influence continues to be felt from the early days of independence, with the proliferation of Islamic boarding schools and hybrid Islamic cultural forms. An important marker of modernity that intersects with the colonial narrative is the construction of the first major road led by Daendels (later known as the Daendels Great Road). This road allowed for transportation, changing the concept of time and speed; it also brought machines into rural life. Railroads were built, factories operated; according to Mrazek, this marked the beginning of modernity in the archipelago. The period of Great Postal Road’s building project was known also as a start of Javanese massive uprisings towards colonial government, since many Javanese lost their lives during the construction. Major William Thorn writes that ‘[a]bout twelve thousand natives are said to have perished in constructing it, chiefly owing to the unhealthiness of the forests and marshes, through which it runs’ (Thorn 1815:208 via Pratiwo 2002).

The post-colonial narrative about the Pantura region is a complex and dynamic one, encompassing a range of landscapes from agricultural areas to fish farms, large-scale industrial developments, and cities with diverse communities, from Islamic boarding schools to Chinatowns, as well as the chaos that arises from the contestation of various identity groups. For some Indonesians, Pantura is seen as a tumultuous region, filled with stories of conflict and resistance, with their people perceived as tough and resilient. Despite policies that are not supportive of maritime culture, the community — albeit, marginalized and often forgotten — continues to survive. Stories of resistance, in various forms of articulation, are an important part of the history of the Pantura community. Without policies to protect maritime culture, thousands of hectares of mangrove areas have disappeared, replaced by factories and industrial zones. Water sources are no longer flowing, agricultural land is becoming narrower, and the livelihoods of fishermen are increasingly squeezed. Resistance has become a way for residents to maintain their survival amidst the threats of strong ocean waves and the pressures of time.

As we embark on this complex and diverse narrative, female figures from Pantura have significantly influenced our journey. At least, there

1. Queen Shima (674-695 AD) was known as a firm female leader. She ruled the Kalinga Kingdom to replace her husband, King Kartikeyasinga, who died in 674 AD. Thanks to Queen Shima’s firmness during her leadership, the Kalinga Kingdom was known throughout the world at that time. Kalinga (also called Keling or Holing) is a Hindu kingdom that was once one of the largest governments in Java, centered on the north coast of Java, precisely in the area now called Jepara, Central Java. Queen Shima ruled from 674 to 695 AD. Queen Shima was born in 611 AD in southern Sumatra and then moved to Jepara after marrying the prince from Kalinga, Kartikeyasinga, who later became king from 648 until his death in 674 AD. The nickname “Shima” is often identified with the term “simo” which means “lion,” but this nickname did not make the queen feared, but on the contrary, she was loved by all her people. (source; https:// fox13.id/en/queen-shima-leadership-andjustice-in-the-kalinga-kingdom)

2. Born as Queen Retna Kencana, Queen Kalinyamat was the third daughter of Sultan Trenggana, the third ruler of the Demak Sultanate. She formed a powerful and formidable naval force, even assisting the neighboring Johor Sultanate in fighting Portuguese colonizers in Malacca. In 1550, Queen Kalinyamat sent a fleet of 40 naval ships with 4,000–5,000 soldiers to Malacca at the request of the Johor Sultanate. Although the mission failed, her navy remained a strong presence. Queen Kalinyamat sent her navy back to Malacca two decades later to attack the Portuguese settlers. According to detik.com, this expedition consisted of 300 ships with an estimated 15,000 soldiers. This second attempt successfully broke the Portuguese dominance in Malacca, although around 2,000 of her soldiers must perish. (Source: https://www.msigonline.co.id/the-story-ofqueen-kalinyamat-the-national-heroinefrom-jepara)

3. Kartini was born on 21 April 1879, in a village called Mayong in the town of Jepara, North Central Java to an aristocrat family. She is the daughter of Raden Mas Adipati Aryo Sosroningrat, the Regent of Jepara. She went to a primary school, along with her brothers, for the children of Dutch planters and administrators. Other girls from aristocratic families did not receive the same formal education she obtained. In 1903, Kartini obtained permission to open in her own home in Rembang the first ever all-girls school, for daughters of Javanese officials. She created her own syllabus and system of instruction. The school aimed at the “character development of young women, while at the same time providing them with practical vocational training and general education in art, literature and science.

are three important figures that are celebrated by the local habitants and authority and even recognized as national heroines. Ratu Shima1 ruled the kingdom of Jepara in the 6th century, marking a governance system that prioritized the people’s welfare. Later, in the 16th century, Ratna Kencana, known as Ratu Kalinyamat, brought Jepara into a new era of prosperity in trade, ports, and maritime traffic, as well as the economy of its people.2 RA Kartini 3 emerged from a generation that deeply explored modern thought and the power of emancipation to challenge gender-based social role disparities. Among the three, RA Kartini was designated by the state as a symbol of “women’s emancipation” and became closely associated with the maternal politics of the New Order period. In 2022, Ratu Kalinyamat was also recognized as a national hero, indicating that the strength of women, illustrated through various influential figures across different time periods, has evolved into myths embraced by the community, both consciously and unconsciously, whilst being shaped by complex political dynamics within the state. Exploring Kalinyamat’s story encourages us to examine how economic and social contexts relate to gender roles in cities based on “maritime culture”. It is noted that in the 16th century, Kalinyamat was quite successful in marking the region’s economic prosperity. From these encouncenters, we started to dig into the main question: How can we reflect on the position of women in economic power relations today?

As we explore the villages along the Pantura coast, we are confronted with the reality that women are still far from achieving positions that guarantee justice. While women demonstrate remarkable strength as the primary economic support for their families, protection and support for equality remains elusive. During our field trips, it is very obvious how women becomes the main economic pillars in the community, especially many of them are widowers or single mothers. The sea has offered them many possibility to be part of the maritime “industry” through smaller scale of trading and sea activities; from the smoke fish making to other foods home-made, or in more land(ing) area, women works in wood carving or weaving home industries. Women in Jepara strongly re-connected with the soul of Queen Kalinyamat, keeping her inspiring life story as something they looked up to, to give them the courage to stand still and to step further. One example of manifestations of this connection is how those women actively visit the praying site (petilasan) of Queen Kalinyamat, at least every month, to send their prayers and to have conversation with their ancestors.

* * *

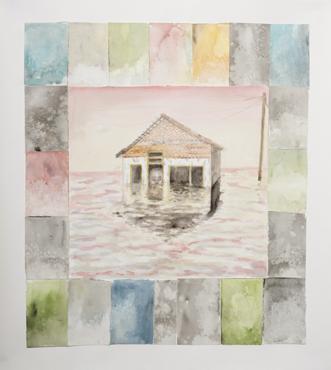

Around 50 kilometers to the west from Jepara, Demak is a smaller city with other complex issues regarding their coastal situation. They faced a fast abrasion, losing mangroves forests and flooding problems for the last two decades. Women are forced to adapt their life and their way of managing household to respond to this environment crisis. The Puspita Bahari group in Demak is an organization of fisherwomen that responds

to such issues and to create a collective movement in struggling within difficult shifts. Puspita Bahari was founded on 25 December 2005 to provide a space for economic empowerment for women fishers and wives of fishermen, on the back of Masnuah’s anxiety over the marginalized coastal women’s life. Masnuah, the founder of Puspita Bahari, born and bred in the fishers village in Rembang District, Central Java, lived through the patriarchal culture and minimum access to information and education for women. Masnuah herself did not make it past elementary school.

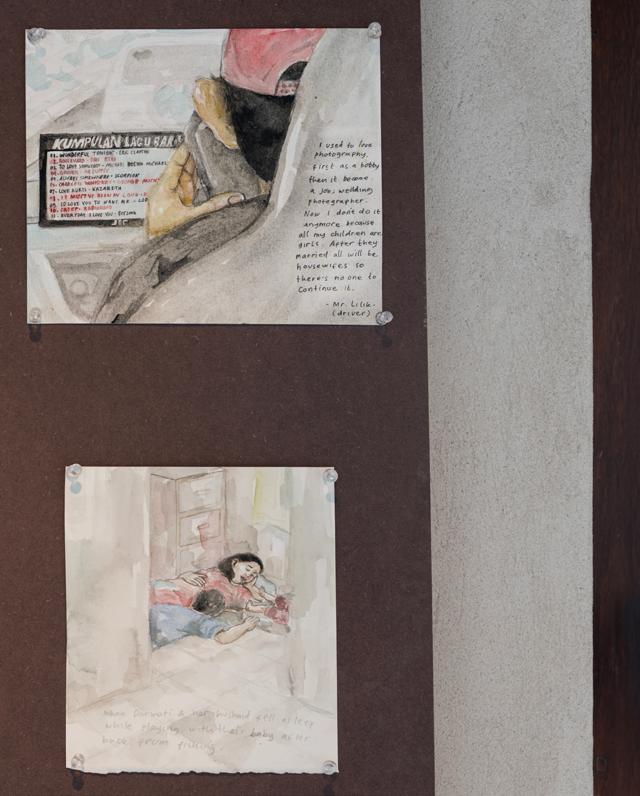

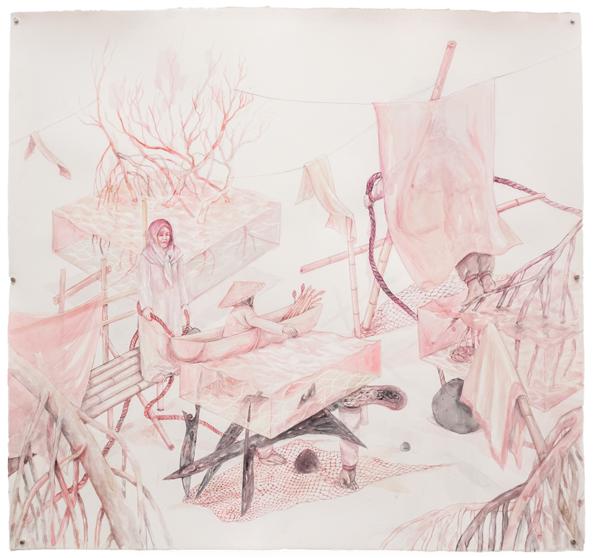

By tracing the journey of Puspita Bahari, Restu Ratnaningtyas was drawn to further explore how these women navigate and adapt to environmental changes and socio-cultural challenges surrounding maritime reality. Her series, “My Ancestor Was a Sailor,” highlights the collective resilience of fisherwomen, incorporating spiritual practices as a source of inner strength and wisdom. The symbols of holding hands serve to explore forms of solidarity. The main part of this narrative-based installation consists of several watercolour paintings characteristic of Restu, depicting the daily struggles of fisherwomen facing gender discrimination, economic hardship, and ecological crises. Restu chose an intimate approach with postcard-like images, making the artwork a memorabilia of mothers caught between private and public spaces, social roles, and individual subjectivity. This project also enables Restu to experiment with ceramic as her medium, to create replicas of different sea creatures — shells, bones, and others — that have strong connection with women’s memory about the sea.

While Restu sees how those women are a strong survivor, instead of representing them as powerless or merely victims of of complex social issues, we can not ignore the systemic marginalization of women in term of their role on ocean economy. Many research have been exploring these gender gap as subject matter; The unequal power relations in the economy, stemming from gender constructions, have led to women being overlooked in state policies related to the protection of maritime areas. Since the 1990s, women have dominated the retail trade system, as men-dominated sectors, such as shellfish and fisheries trading, have proven inefficient due to their tendency to spend money on “alcohol, gambling, and extramarital relationships” rather than bringing it home to their families (Barclay et al., 2018: 204). When examining the tuna value chain in Indonesia, men are typically seen in positions involving heavy physical labor and lifting, or in higher authority positions that accumulate greater wealth. In contrast, women are often found in lower-value market trading positions, leaving them without strong social standing when negotiating to improve their livelihoods. Additionally, social taboos limit women’s involvement at sea, including the notion that women should not venture out to sea. Women typically do not occupy higher authority positions, making them vulnerable to labor exploitation.

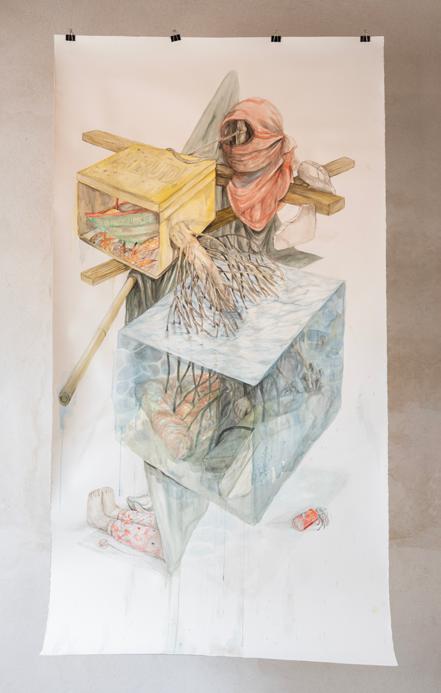

Dian Suci has conducted in-depth observations in recent years to explore how women navigate domestic space, in their personal lives and

in the economic context that emerges within that domesticity. Her works investigate the lives of women workers who are an extension of global industries, focusing on work processes done at home, such as sewing, attaching buttons, and labeling. In a still strongly patriarchal culture, the dual demands of domestic responsibilities and the pressure to boost family economies has shaped bodily articulations marred by repetitive patterns, long-term unrelenting fatigue, and often neglected emotional conditions.

Dian Suci explores narratives about the contributions of women from the northern coastal region of Java, inspired by historical figures like Ratu Kalinyamat and Kartini, highlighting how women’s knowledge has played a significant role in the region’s economic growth. The Jepara city area, where her research is conducted, has a history as one of the largest trading ports in the early 17th century, known for its massive wood carving crafts and later developing into a weaving craft center in the 1990s. Dian Suci is interested in examining the tension between myth and historical glorification of a maritime city focusing on women’s involvement in social-political dynamics and the impact of economic expansion and extraction on women’s bodies and lives.

In the wood carving motifs presented, Dian Suci explores Jepara’s history as a cosmopolitan space marked by carving motifs that show Chinese cultural influences and the introduction of new visual languages in early 17th-century Jepara. Specifically, in realizing these carving ideas, she collaborated with a female carver. Dian was interested in observing how women, who were once the main supporters of Jepara’s renowned furniture industry from the 1980s to the 2000s as carvers, are no longer interested in mastering this skill and have shifted to working as factory workers due to the establishment of many new factories in the Jepara area. Not only is carving, but also the weaving craft industry which was developed in Jepara in the 1990s, threatened with losing workers due to the increasing construction of industrial factories. In this context, it seems important to highlight how women are not only the backbone of family economics but also the guardians of knowledge and artistic creation skills. Additionally, Dian Suci highlights women’s knowledge related to spiritualism, where maritime life requires various rituals to ask for safety and strength when facing the sea with all its natural surprises.

Ipeh Nur has been engaging with the archeological aspects of materials and objects as part of her investigation of various local histories. In this maritime project, Ipeh Nur’s research led her to a finding on the landscape of North coast of Java thousands years ago, where some parts of the cities lay there showing the evidence of mystical existence of Muria strait. The changing nature of its landscape and seascape has shaped also different layers of soil, sands, stones, karst, beneath the earth. While the natures showed constant shifts of different period of the land’s archeology, the social and anthropological traces also referred to the fast changing of the human civilization, from the ancient era of the

ancestral spirit to the dark history of colonialism. Ipeh Nur juxtaposes the line of Muria strait and the path of Jalan Raya Daendels (The Great Post Road) — one of the first big infrastructure projects of Dutch colonial government, to connect north part of Java from the far West to the far East (Anyer to Panarukan). The road had dramatically changed the political economic contexts of Java in 19th Century, with the intensification of farm commodities (including teakwood, sugar, rubber, and many others). It is the start of intensive extractive acts from human to the nature; the relationship had fallen into a from a mutual understanding of life cycle to transactional. Another line that passing this area is the mountain Kendeng, the longest karst area in Java, with the water sources in her body, that has been continuously struggle to survive, being threaten by many industrial projects. In her work, Ipeh underlines the relationship between mother earth and women’s body as metaphor, where she saw the form of the caldera similar to women’s womb, both are the source of life with nurturing nature.

Ipeh Nur uses various materials she found during her research trip, the sand, stone and soils, as part of her paintings that depict stories of what has been lost and what has emerged, what was forgotten and what stays within, what the buried under and what are flying around above the sky. She interweaves different textiles and materials, to trace various commodities as the result of extractive modes of operating, and even leave them torn out, roughly cut or let big holes in the paintings to give sense of damage and destroyed landscape. Her bold experiment on the form of painting goes smoothly with her complex process of researching and formulating the narratives.

This maritime project is a small start for the artists involved and myself to reflect the current situation of our ecological crisis, from the stories of mothers in Demak and Jepara, and from crying forest and rivers. During our field trips, the ancestral spirits whispering through the ocean waves, the old magic trees, and the water source that has been central to the life of women. The mothers of Puspita Bahari, the weavers of Jepara lurik textile, and women farmers from cities lies in the line of Pantura had greatly shared and inspired us with their endurance, resilience, and dedication to protect their land and water, to embody everyday life practice as our way producing knowledge as the legacy for next generations. While some songs from the rituals seemed to be a mourning for the lost of mangroves and all lives disrupted by many disasters, these struggle from below also turn the songs as a voice of faith.

From various stories and mithologies of those women who had left their traces along the north coast of Java, these three artists bringing a strong statement on the survival of women despites all the shifts of ecological crisis and global economic dynamics. Juxtaposing traditional crafts and contemporary artistic approaches, and composing poetic

interpretation of various rituals and historical archives, Dian Suci, Ipeh Nur and Restu Ratnaningtyas present subtle and gentle reminder on forgotten life lines, for those who risks their life for their beloved family and for maintaining spiritual relationship with the past, whispering a hope for a better future.

REFERENCES

Pratiwi, Andi Misbahul and Boangmnalu, Abby Gina The Existence and Power of Fisherwomen in Morodemak and Purworejo Villages: Against Violence, Bureaucracy & Biased of Religious Interpretation. Jurnal Perempuan, VOL. 22 NO. 4 (2017)

P nas Pratiwo, Java and de groote postweg, la grande route, the great mail road, Jalan Raya Pos, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, On the roadThe social impact of new roads in Southeast Asia 158 (2002), no: 4, Leiden, 707–725

N McClean, K Barclay, M Fabinyi, DS Adhuri, R Sulu, T Indrabudi, Assessing the Governance of Tuna Fisheries for Community Wellbeing: Case studies from Indonesia and Solomon Islands, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, 2019

Suryakusuma, Julia. Fish, feminists, fishy business, bureaucracy and religious bias, The Jakarta Post, February 7, 2018

Click to read: https://www.thejakartapost.com/ news/2018/02/07/fish-feministsfishy-business-and-religious-bias. html.

Ipeh Nur