I am pleased to welcome you to this year's Desert Researcher Magazine. This publication illuminates the remarkable scientific discoveries within Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California's largest and most biodiverse state park.

This magazine embodies the unique three-way partnership between AnzaBorrego Foundation, the Park's natural resource team, and UC Irvine's Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center. Our collective mission extends beyond conservation to creating a scientifically informed community of desert advocates who understand the intricate ecosystems we strive to protect.

As you explore these pages, you'll discover the extraordinary work of researchers studying everything from flat-tailed horned lizards and migratory birds to invasive plant species and paleontological discoveries. In the past year alone, researchers published dozens of scholarly works on our region, contributing vital knowledge about desert ecosystems, climate impacts, and the ancient history preserved in our landscape.

What makes this work truly meaningful is how it connects to the broader mission of Anza-Borrego Foundation. Since 1967, we've conserved over 57,000 acres of desert habitat, transforming the Park from a fragmented landscape into the expansive wilderness it is today. Every acre we protect provides researchers with intact ecosystems to study, enriching our understanding of this remarkable place.

This cycle of research, education, and conservation creates a powerful synergy. The scientific discoveries featured in this magazine inform our education programs, from the new "Anza-Borrego for All" initiative to our teacher symposia and BioBlitz events. These programs, in turn, inspire new advocates for the Park's protection, ensuring that future generations will continue this vital work.

The challenges facing our desert are substantial, from climate change impacts like extreme heat and flash flooding to invasive species and habitat fragmentation. Yet I remain optimistic because I've witnessed the remarkable adaptability and resilience of the desert ecosystem and the dedicated people working to protect it. I've seen firsthand how research-based education creates lasting connections between people and this extraordinary landscape. When someone learns about the complex relationship between bighorn sheep and their habitat, recognizes an endangered bird species by its call, or discovers ancient fossils eroding from mudstone hills, they develop a personal stake in the Park's future.

Bri Fordem Executive Director Anza-Borrego Foundation

To protect and preserve the natural landscapes, wildlife habitat and cultural heritage of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and its surrounding region for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations.

Dan McCamish, Senior Environmental Scientist, Natural Resources Program Supervisor, Colorado Desert District, California State Parks

This publication allows us to reflect on the role that science, in many forms, plays in the guiding stewardship of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park (ABDSP) and the broader Colorado Desert District. ABDSP is the largest Park in the California state park system, covering approximately 650,000 acres of desert, mountain, and riparian ecosystems. ABDSP managers rely heavily on research partnerships to better understand, monitor, and protect the incredible diversity of Park resources within their care.

Scientific study here is not just valuable it's essential. With limited staff and an expansive landscape to manage, we depend on collaborative efforts with universities, nonprofit partners like Anza-Borrego Foundation (ABF), and dedicated individuals who care deeply about desert ecosystems. Research provides the data Park employees need to inform habitat restoration, track invasive species, plan for climate resilience, protect cultural landscapes, manage recreation, and ensure that future generations can experience this region's unique history and biodiversity.

To help advance this mission, select research grants are available each year through the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Natural Resources Program and AnzaBorrego Foundation.

If you are interested in conducting other general scientific research within Anza-Borrego Desert State Park that is not grant-specific, visit this link for information on the California State Park Scientific Research Permit process.

Research grants are available each year through the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Natural Resources Program and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Natural Resources Program and The Anza-Borrego Foundation. These ABDSP Natural Resources Research Grants may provide up to $10,000 annually (based on availability) for projects directly supporting natural resources research within ABDSP. Grants may support student and professional work in ecology, wildlife biology, fire management, hydrology, paleontology, geology, or wildland restoration and conservation science.

Submit a research summary (no more than three paragraphs) describing your topic, its relevance to the Park's long-term natural resource management, and a general map/location of the proposed study area. Email your submission to:

danny.mccamish@parks.ca.gov with the subject line: "2025/2026 Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Research Grant Inquiry" by February 1, 2026, for consideration.

In every case, researchers must obtain all necessary permits before beginning research within the Park. Please reach out early to ensure your project aligns with park priorities and permitting timelines.

Did you know that Anza-Borrego Foundation administers three scholarships that encourage research in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and the Colorado Desert for students and professionals?

The Howie Wier Memorial Conservation Research Grant assists graduate students conducting field studies in the Colorado Desert and Peninsular Range region of southern California. Funds requested can be up to $2,500.

The Paul Jorgensen Conservation Research Grant assists graduate students, post-graduate researchers, or professionals conducting field studies within the Colorado Desert and Peninsular Ranges of southern California. Funds requested can be up to $2,500.

The Begole Archaeological Research Grant (BARG) program is designed to support scientific archaeological research in Colorado Desert District (CDD) parks and in other areas of the California and Baja California Desert regions. Funds requested can be up to $5,000 with no restrictions on research proposal topics, as long as they are archaeological in scope and/or focus. Applicants may be students or industry professionals.

John Taylor, M.S., Environmental Services Intern for California State Parks

The environmental science staff of the Colorado Desert District of California Department of Parks and Recreation have been continuing our regular duties of natural resource management within Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. The forestry aides, environmental services interns ("ESI"), and environmental scientists have continued collecting and analyzing data about plants, animals, and ecosystems to develop and implement conservation efforts so that the Park's resources last for our vis into the future. Although our Park has "desert" in its name, it has many habitats between its low desert to the east and high coastal mountains to its west, giving it a great diversity of plants and animals that need our protection in an increasingly human-impacted world.

Keep reading to hear about a few of our ongoing research projects!

Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Survey Team: Samantha Birdsong (Environmental Scientist and ICC Representative for ABDSP), Jun Wang (ESI), John Taylor (ESI), Giselle Sandoval (ESI), Emelyn Hernandez (Forestry Aide), Jillian Petersen (ESI), Noriko Smallwood (ESI), Harrison Sturgeon (ESI), Hayley Elsken (Associate State Archeologist), Connor Moret (ESI), and Sydney Magner (ESI)

Flat-tailed horned lizards are native to the low elevations (sea level to 1000') of the Colorado Desert, from north of the Sea of Cortez in Mexico to Palm Springs, California, and into Yuma, Arizona. They are listed as a "Species of Special Concern" by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which protects them from collection and land development. These lizards also have a mix of government land agencies monitoring and protecting them, such as the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Interagency Coordinating Committee (ICC). Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is one of the founding members of this committee and has been helping to better understand these lizards since 1997.

d Lizards llii, "flat-tails")

In September 2024, we completed another summer season of flat-tailed horned lizard occupancy surveys. These surveys occur between May and September, and our teams of two eave the office before sunrise to walk up to three plots over an hour, looking to detect at least one lizard. If a izard is captured, its size (body ength and mass) is measured, and its

sex is recorded before release. The survey plots are visited five to six times to attempt detection. In 2022, 13 out of the 41 plots had horned lizards detected. In 2023, 10 out of 28 plots had horned lizards. Summer 2024 was our most successful survey year, with 27 of the 53 plots surveyed having flat-tailed horned lizards present. Lizard detection is the result of a variety of environmental factors, including annual precipitation, temperature, food availability (harvester ants), and general habitat suitability. Our occupancy surveys will eventually be used to choose areas for demography surveys so that we and the other organizations of the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard ICC can better understand these special lizards.

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is the temporary home of two migratory species listed as threatened and endangered by the Endangered Species Act: the Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo and Least Bell's Vireo, respectively. These birds use our Park's woody riparian areas (creeks, streams, and rivers surrounded by dense shrubs and trees) for their nesting sites. Migration stops during the warmer parts of the year, especially late spring and early summer. Agricultural and urban development across Mexico, the western United States, and southwestern Canada has led to the loss of suitable habitat for these two species. This has given our natural resources team great reason to evaluate how California's protected land may benefit each of these species' populations by surveying and recording area occupancy, behavior, and potential nesting. Our survey teams follow designated routes through suitable habitats to listen for singing and calling while also looking for pairing and nesting. In the same surveys, the team stays as quiet as possible to observe all other species (including other birds, amphibians, and mammals) using these limited riparian resources in our desert.

Tamarisk (Tamarix spp.) is a group of shrub and tree species native to the African, Asian, and European continents. The plants are often used in landscaping with beautiful white to pink flowers. They were also planted historically in California as windbreaks because of their dense foliage (collective of leaves). This fall and spring, our botany and forestry teams have set out to reduce the number of Tamarisk growing in riparian areas and desert washes, where they absorb a substantial amount of water that other native trees and shrubs rely on. Tamarisk are also known as salt cedar because they absorb salts through their roots, store it in specialized glands, and then release it through their leaves. Over time, these salts fall off and accumulate on the soil surface, making it hard for other plants to grow.

Our botany team hand-pulls other invasives throughout the Park, including Sahara mustard, desert knapweed, and stinknet. The lack of rainfall between fall 2024 and spring 2025 has made the botany team's work less stressful this year, with a reduction in invasive species sprouting. There might be a break this year, but the seeds of these invasive species can survive for long periods and will sprout in future years when given enough water.

Paige

Prentice, Statewide Bighorn Sheep Coordinator, California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Bighorn sheep are the living emblem of Anza-Borrego Foundation, and they make their home in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park (ABDSP). Yet, their cryptic coats and preference for remote canyons make them notoriously hard to spot, much less count. Known as Peninsular bighorn sheep (PBS), this population is a distinct population segment of desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) and is federally listed as endangered and state listed as threatened. The California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW) monitors and manages this population in close collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) under its

Recovery Plan. Together, we work alongside Tribal partners and land management agencies—the largest of which is ABDSP to monitor disease, track population trends, identify conservation concerns, and prioritize management actions.

Over the past year, CDFW has worked closely with ABDSP and other partners to coordinate and execute range-wide capture and

collaring efforts, as well as a helicopter-based population survey.

In late October 2024, CDFW led the capture and collaring of 85 bighorn sheep (53 females, 32 males) across all nine recovery regions. We captured a higher proportion of rams than in past years to better understand movement and connectivity between recovery regions. Each animal received a GPS collar and ear tags for unique identification. Field and base camp processing included the collection of blood, nasal and rectal swabs, fecal and hair samples, a body condition assessment, and age estimation. Additionally, in basecamp, morphometric measurements and ultrasound scans were conducted to assess body condition and pregnancy of ewes. The GPS collars are programmed to record an individual’s location every two hours and to send an email (mortality alert) if the animal hasn’t moved for more than eight hours. These data help us to understand habitat use and allow us to get causespecific mortality information, respectively. Already, the GPS data is revealing regular ram movement between recovery regions and data from prior years are being used to help inform potential wildlife overcrossing structures along Interstate 8.

Six weeks after captures, we flew helicopter surveys across predetermined polygons in all nine recovery regions. Over 52 flight hours, we recorded 512 individual sheep in 102 distinct groups (Map 1). Using the uniquely marked (collared) individuals in a spatial mark resight model, we estimated 743 adult bighorn range-wide (95% confidence interval 656–830). The raw composition was 240 adult ewes, 131 adult rams, 45 yearlings, and 75 lambs—lamb to ewe, yearling to ewe, and ram to ewe

ratios of 31, 23, and 55 per hundred, respectively.

Longterm monitoring shows total abundance has climbed since 1994 but has edged downward from a 2010 peak (Figure 1). Northern recovery regions—the SanJacinto and Central SantaRosa Mountains— continue to see population growth, likely aided in part by lush urban fringe habitat. Meanwhile, the Vallecito Mountains and Carrizo Canyon within the park have experienced declines, potentially due to disease and drought. The Recovery Plan states that to consider downlisting, each recovery region needs at least 25 adult ewes, and that the range wide population estimate must average 750 or above and be stable or increasing for twelve consecutive years. Currently, we are just shy of that threshold, and several southern regions sit below the ewe minimum, underscoring the need for ongoing management.

Disease continues to be one of the greatest threats to PBS recovery. The disease results from the recent capture effort showed that some individuals tested positive for pneumonia (Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae), but thankfully there were no new strains detected. That said, domestic sheep and goats continue to pose a serious disease risk to wild bighorns, and it is important that we continue to educate the

public on the need for separation (more information here). If members of the public see a domestic sheep or goat wandering ABDSP (or any bighorn habitat), they should notify CDFW.

Looking forward to better managing the costs associated with both capture and survey efforts, CDFW plans to stagger these activities in the future. A smaller capture effort is planned for this fall, with surveys set for the following year. In the meantime, CDFW is working with ABDSP to place cameras at water sources which will help monitor the population. Given the need for individuals to visit surface water during the hot summer months, trail camera data can be used to estimate population numbers and document recruitment. Additionally, CDFW is collaborating with a graduate student to build an integrated population model using data collected through these various surveys, as well as survival data from the collars. This model will help identify drivers behind the population trends, informing management priorities. Stay tuned for future updates as we continue to monitor and protect these iconic desert dwellers.

Syd Magner, Environmental Services Intern

Founded in 2008, the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Botany Society consists of Park volunteers who contribute to botany and conservation through public education, fieldwork, and herbarium work. The Society is an integral part of the Botany Department's operations and allows Park staff to achieve things that wouldn't be possible without the help of dedicated volunteers.

Each year, the Botany Society teams up with Anza-Borrego Foundation to host interpretive plant walks for the general public. Typically, these walks occur from January through early April and are timed to match the general duration of the Park's wildflower season. One Society member takes on the role of plant walk lead and is responsible for educating visitors on the Park flora, while another member acts as a co-lead who accounts for visitor safety and keeps the group together. This year, around a dozen walks were held in various areas of the Park, including Coyote Canyon, Glorietta Canyon, Henderson Canyon, and Mine Wash. Society members may bring other educational aspects into the walks as well, such as geology, weather, and other natural history elements. Don Rideout, Marlin Burke, and many others have been instrumental in the success of this ongoing

educational program.

Join a plant walk this spring! Register at theabf.org

In collaboration with the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center, the Botany Society has also hosted numerous plant experts to provide members of the public with free lectures and information. This season's guest speakers have focused on gardening with desert plants and the frequently overlooked topic of plant/pollinator interactions. Past lecturers include Dr. Jon Rebman (Curator of Botany at the San Diego Natural History Museum), Dr. Michael Simpson (Professor of Biology at San Diego State University specializing in the genus Cryptantha), Dr. Naomi Fraga (Director of Conservation Programs at California Botanic Garden), and many others.

The Botany Society routinely participates in rare plant surveys, the goal being to help Park staff better understand species ranges within the Park and identify any threats to their existence. In preparation, Society members are given brief training on target species identification and how to use iNaturalist to collect spatial and photographic data. So far, the Society has improved the Park's understanding of the ranges of many rare and locally limited plants such as Thurber's stemsucker (Pilostyles thurberi), Arizona carlowrightia (Carlowrightia arizonica), and cottontop cactus (Homalocephala polycephala ssp. polycephala). More target species are being added to the Botany Department's priority list for future surveys. The Botany Society also plays a critical role in removing invasive plants from some of the most iconic parts of AnzaBorrego, mostly in Coyote Canyon and the wildflower fields off Henderson Canyon Road. Hundreds of hours per year are cumulatively spent hand-weeding Sahara mustard (Brassica tournefortii) and Egyptian knapweed (Volutaria tubuliflora) from among the spectacular wildflower displays that visitors come to see when sufficient rainfall has occurred. Without the Society and other weeding group's efforts, what we see today may eventually become a monoculture of weeds.

The Botany Society also performs various herbarium duties for the Botany Department. These duties include mounting specimens collected in the field, scanning specimens so that they can be viewed online, and filing specimens away into the main collection. Since the Society's inception, thousands of specimens have been mounted, and hundreds of specimens have recently been scanned for the Botany Department.

Hayley Elsken, Associate State Archaeologist / Tribal Liaison Colorado Desert District

The Archaeology Program at Anza-Borrego Desert State Park continues to lead vital cultural resource inventories across the expansive desert landscape. Each year, the program receives numerous reports from visitors, park staff, and volunteers describing cultural resources they encounter while exploring or working in the Park. While some of these reports correspond with previously documented sites, many highlight previously unrecorded or unknown locations.

In response to the growing number of new reports, the Archaeology Program assembled a dedicated team this year to follow up on these findings. Their goal: to ensure that each reported site is properly visited, recorded, and documented. Updated and accurate site records are essential tools for protecting cultural heritage. These records enable the team to monitor sites for changes over time, provide critical information during emergencies, and support informed management recommendations.

Among this year's notable contributions to the field is the work of Mandie Carter, a State Park volunteer and recent graduate of San Diego State University. For her senior thesis, Mandie explored contemporary archaeology within the Park, focusing on the cultural phenomenon of "Shoe Trees" or trees that have become adorned with shoes.

Mandie's research centered on the San Felipe Valley Shoe Tree. She proposed that the Shoe Tree functions as a liminal space: one that exists between legality and illegality, is transient by nature, and is situated in a place of physical and social transition. Through detailed analysis, she cataloged and examined the types of shoes on the tree to identify patterns and the demographics of those contributing to the display.

Her findings revealed that the Shoe Tree attracts a wide range of visitors. Shoes came not only from hikers along the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) but also from local high school students, off-roaders, and members of the surrounding community. Mandie presented her insightful research at the annual meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, contributing a unique perspective to the broader conversation about contemporary cultural expression in modern landscapes.

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Paleontology Program and Volunteer Society were established as part of the Parks Natural Resources Division in 1992, with the intent that the Park would take on full management of the considerable fossil resources eroding from more than 100,000 acres of fossil-producing sedimentary beds in the Park. Before that date, fossils recovered under a state permit were curated by the collecting agencies: Los Angeles County Museum, Imperial Valley College Museum, and the University of Arizona. Those institutions collected more than 12,000 catalogued fossils between 1954 and 1987. They were all returned to the Park between 1992 and 2009. In the years since its establishment, the program and society have more than doubled the size of the collection. Paper catalog data and historical documentation have been continuously transposed to digital format.

All of the data are now available for mapping projects via GIS, which is useful for planning future fossil surveys, excavations, and related geology projects, as well as investigative queries regarding the past presence and distribution of fossil organisms and the characteristic environments implied by their presence.

In the past ten years, the program has incorporated 3D photogrammetry of fossil elements (bones, shells, wood, tracks, and burrows) and aerial capture of fossil sites via drone 3D imagery. The program have also incorporated digital microscopy into a data-

gathering protocol. These tools allow us investigation in to the microvertebrates (rodents, lizards, insects) that are difficult to see and describe under standard lighting and hand lenses. Micro-fossils are also now being studied. These are tiny organisms found in ancient sediments smaller than 1 mm, requiring magnification on the order of 100x to 1000x and including ostracodes, diatoms, and pollen. In addition, layers of volcanic ash, which erupted from past events at Long Valley Caldera and Yellowstone and covered the regional landscape tens of thousands to tens of millions of years ago are being reviewed. These materials require a petrographic microscope with similar high magnification.

About 90% of the hands-on work of discovery and recording of fossils, cleaning and repair, fossil identification and description, data entry, labeling, and storage is done by Paleontology Society Volunteers. These individuals undergo a season-long certification class and additional training for specialty tasks, such as photogrammetry, GIS analyses, or other projects they may wish to pursue. Those interested in joining the Paleontology Program and Society as a volunteer are encouraged to view the website at Anza-Borrego Desert Paleontology Society homepage.

Dutcher, Ph.D.

I moved to Borrego Springs with my family in the summer of 2024 from Las Vegas, Nevada to begin my career with the University of California, Irvine at the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center. My time working as conservation biologist in the deserts of North America taught me that these places are fragile systems where species are uniquely adapted to survive harsh conditions near the edge of what is tolerable for life, making them incredibly special. For example, the Mojave desert tortoise, the focal species for my research, can survive for roughly two years without water because they store it in the bladder, converting toxins to uric acid, and recycling water from their bladder into their body when needed. This amazing adaptation for survival in extremely arid environments is compromised if they become frightened and void their bladder; one of the many reasons not to handle a tortoise or get too near, unless it is in harm’s way, in which case please move the animal to a nearby safe place. Tortoises, like many desert dwellers, also exhibit behavioral adaptations for survival such as spending the majority of their lives underground.

Deserts, despite popular perception, are teaming with life that is often unseen and underground, leading many to view them as barren lands. This, in my opinion, has been a contributing factor to the unprecedented levels of recent and rapid development and disturbance in desert landscapes. For example, we currently rely heavily on large-scale solar infrastructure rather than distributed solar. Developments are often sited in desert habitats, requiring large swatches of land where vegetation is bladed and graded or mowed. Because desert vegetation is incredibly

slow to recover from disturbance it is likely that these communities are permanently lost, dramatically altering the landscape at scales and rates of change that are too large and too fast for most species to adequately adapt. Additionally, the utility infrastructure required by large-scale facilities increases the footprint of linear disturbances such as power lines, which promote invasive species and subsidized predators in wildlands.

Our deserts are in great need of habitat protection, and I am proud to be part of a unique partnership between the University of California, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, and Anza-Borrego Foundation that is working together towards that goal. As the incoming director of the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center I am honored to be replacing Jim Dice, the emeritus manager. I hope to translate my expertise in landscape genetics, spatial statistics, and passion for science as tools to support informed and data-driven solutions to support research, education, and community activities in Anza-Borrego and Borrego Springs.

“In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.” –Baba Dioum

Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center in Borrego Springs is managed by the University of California, Irvine and is part of the Natural Reserve System. With 42 reserves across the state of California, it is the world’s largest university run system of protected natural areas. The Research Center functions under a collaborative partnership between the Anza-Borrego Foundation, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, and the University of California, Irvine with the common goals of promoting research, education, and public outreach. Although we are operated by the University with a strong focus on research, the facility is not just for scientist or users from the University of California. We routinely host users from across the United States and other countries. We provide low cost lodging, meeting areas, a classroom, and lab space, and can accommodate individuals or groups of over 100.

University professors and students

Researchers

Anza-Borrego Foundation

State Parks and other government agencies

Volunteer organizations

Local community groups

K-12 students and teachers, including Borrego Springs

Unified School District

Classes (universitylevel and primary)

Educational programs

Meetings

Trainings

Writing and lab retreats

We are proud to serve as your local University of California Natural Reserve and accept applicants from any field in any subject area, provided activities are substantive, feasible, and free of adverse environmental effects. Users need valid qualifications and an affiliation with an institution of higher education, government agency, research group, non-profit organization, or primary education (K-12). Activities must comply with University of California policies, cooperative agreements, and federal and state laws. Recreational use is strictly prohibited. Users need to obtain applicable federal, state, or local permits. Work must explicitly acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center.

Matthew Herbst, Ph.D. ,

hills strewn with Maple, Locust, Pear, Oak, Pine, Birch, and other species, all of which shaped my environmental outlook. I worked for a time in the National Park Service, serving as a ranger in the Hudson Valley at the home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and at Val-Kill the home of Eleanor Roosevelt. It seems only fitting that, decades later, my faculty appointment at UC San Diego would be at Eleanor Roosevelt College.

Up to that point in life, desert had no experiential reality. This changed when I wrapped up graduate work in Ann Arbor and drove to San Diego, encountering the land’s transformations from plains to mountains before plunging into the splendor of Utah, a view enhanced by reading Edward Abbey and Terry Tempest Williams. Onward to northern Arizona

and the diverse cultures and peoples of the region (where I would later return to offer an experiential UCSD program). From there, I descended into the Sonoran Desert, traveling the route that follows the Gila to the Colorado River at Yuma — gateway to the Colorado Desert.

Entering this region, I immediately noted the disappearance of the Saguaro which had so marked the Sonoran. Similarly, when one travels north, the transition from the lower-elevation Colorado Desert to the higher-elevation Mojave is denoted by the appearance of another distinctive marker - the Joshua Tree. What, then, marks the Colorado Desert? Is it the ubiquitous Creosote? Yet, the range of this hardy bush is more expansive, covering Baja, all of the California deserts, and into the Great Basin and Chihuahuan Deserts. More unique, though less ubiquitous, is the region’s Washingtonia filifera the California Fan Palm.

That first Colorado Desert encounter sparked questions that have engaged me down to the present, as I saw, inter alia: dunes, valleys, and mountains, farms, irrigation systems, and the Salton Sea, towns and transportation networks (roads and railways), resource extraction projects and detention centers, and the US/Mexico border, which played such a significant role on human and environmental history, huge stretches of federally- and state-managed land, including one enormous state park that intersects, directly or indirectly, with all of the aforementioned.

Pursuing answers to newly formed questions, weekends and breaks found me back in the desert. As my children grew, the regional exploration expanded more widely. I became “the desert guy” for my kids’ scout troop and more excursions followed. In 2012, I began bringing university students, teaching quarterly seminars called “God, Satan, and the Desert” and “Sacred Mountain,” which included weekend experiences, and added a World History course with a weeklong (Spring Break) program. I have since led 24 university programs, plus an equal number of programs with scouts, community groups, and other partners. Each outing added insight, setting the land, its peoples, and history in a more informed context. This required interdisciplinary conversation that pushed me beyond my academic training and spurred partnerships with experts in geology, biology, ethnic studies, outdoor leadership, and other fields. In fact, one of the joys of visiting the University of California’s Steele-Burnand Research Facility in Borrego Springs is meeting others who are fascinated by the desert from many diverse perspectives.

I paired this inquiry with an inward turn, interrogating my own interaction, and invited others to do the same. Why were we going to the desert? How were we interacting with it -- or were we simply “using” it? Might our engagement have a harmful impact on the desert and its inhabitants (and how does this compare with past interactions)? With such questions in mind, the focus locally began to merge with broader religious, historical, environmental, economic, and other themes that set the Colorado Desert as a place of global significance. This academic inquiry falls within an emergent discipline known as Environmental Humanities. For this article, let me extract one aspect of my work, which considers the desert as the locus of the sacred, highlighting one dimension — pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage is a phenomenon deeply imbedded in the human experience across continents, cultures, and time. It is an intentional, challenging journey to a site recognized for its transcendent importance. Through this, the participant gains a transformative experience, returning home with the internal benefits of the encounter. As an imaginative exercise, consider Anza-Borrego Desert State Park as a whole and the many sites within. What might we propose for this category of analysis and what would be the rule used to determine this? Coyote Canyon, Piedras Grandes, Ghost Mountain, something else? Looking further afield in the desert region, might one consider the Travertine Rocks Memorial, Salvation Mountain, Pilot Knob, Felicity’s “Official Center of the World,” the Yuha geoglyph, another site? Today, efforts are underway to foster pilgrimage routes in the United States and organizations promote pilgrimage as a means of raising awareness and advocating for justice, and the Colorado Desert plays a part in both efforts.

In 2024, for example, Friar Keith Warner of San Diego’s Franciscan School of Theology offered a border pilgrimage, a five-day journey of learning and encounter, partnering with migrant-serving organizations, including in the Colorado Desert border region at Mexicali (Mexico). The goal was for participants to articulate their own “theology of migration.” 24 sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart participated. Sr. Suzanne Cooke explained that this furnished an opportunity to reflect on the question: “What's my responsibility?" This is one of many pilgrimages in the region with an explicit goal of addressing justice. The intent of other collective action has varied from supporting or opposing abortion to ending detention facilities.

Four decades earlier, a pilgrimage of a different kind took place when Paolo Coelho, author of the acclaimed The Alchemist, visited Borrego Springs. This experience morphed into his novel, The Valkyries. An Encounter with Angels (1992), which depicted a search to encounter

the sacred. The story recounts how Paolo and his wife travelled to the region for a 40-day spiritual journey, traversing all of the Californian deserts, before returning to Anza-Borrego, where he had the sacred encounter at Glorietta Canyon. To commemorate this occurrence, Coelho placed an image of the Virgin Mary as a memorial of this epiphany. The novel declares:“In this place, the energy of the soul of the world was felt and it will be felt here forever. It is a place of power.” Such is the power of Anza-Borrego.

Since 2001, the Virgin has inspired a far greater desert pilgrimage that takes place every December 12, the Feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe, in the Coachella Valley. The thirty-mile journey starts at Our Lady of Solitude Catholic Church in Palm Springs and ends at Programa Misionero del Valle in Coachella. This is the longest current pilgrimage in the nation, moving along road and highway from early morning to the evening finish. This twenty-first century pilgrimage grew from a modest beginning to the current experience in which many thousands participate annually. For those who do not have the time or the funds or the documents to make the pilgrimage to the Basilica de Santa María de Guadalupe in Mexico City, which is the most popular pilgrimage site in North America (with some 13 million pilgrims), this Colorado Desert pilgrimage offers an arduous trek for a transformative experience closer at hand.

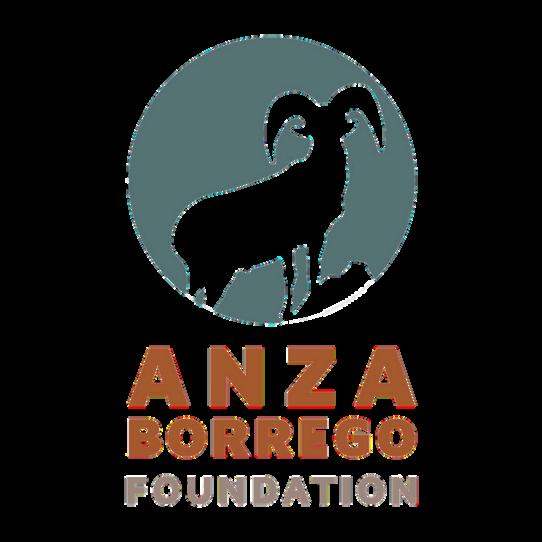

Shifting south, one finds 75 teens pushing wooden carts, each weighing 400 pounds and loaded with supplies, including sleeping packs, food, water, and clothing. The youth worked in groups organized as “families,” each entrusted to a particular cart. They were dressed in nineteenth-century American fashion, except for their footwear, which

was contemporary. The teens were accompanied by adult chaperones, with other adult volunteers helping each night. For three days and two nights, the youth crossed 13 miles of desert, reaching their destination in Anza-Borrego’s Blair Valley, which they called “Zion” – the promised land.All were members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints, participating in a ritual known as a Pioneer Trek, where young believers replicate the experience of their spiritual ancestors, who traversed the

West from Illinois to Utah as well as to other regions – as in the case, following the route of the Mormon Battalion. These treks were regular occurrences until the 2020 Covid shutdown and will soon start again. This Pioneer Trek is a re-enactment of the past, literarily walking in the footsteps of their predecessors, with a goal of attuning youth to their own past and by doing so, spiritually fortifying them. As one teen noted: “I think when you realize what those who came before you sacrificed and when you get a glimpse of the sacrifice they went through, it makes you appreciate what you have.” Another added:“When we had finally

reached Zion, I had this new energy and joy that I wanted to just run around. I then realized we were so blessed now days to have air conditioning as well as doctors and water on hand. Our ancestors didn’t have all that and still sacrificed going through all for this so we could worship freely. I think it made us recognize the things in life we take for granted.”

Let me conclude by going still further back in time. The Cahuilla community, whose territory stretched from Borrego Springs north through the Coachella Valley (and into mountains and passes), teach how the creator god Mukat fashioned humans in this desert region.

Creation began here. Mukat guided the people up to the last moments of this life. His death prompted the Cahuilla to depart in search of a new home. These momentous events are recorded through Cahuilla Bird Songs that recount the migration, as the people searched for the right place to call home. Their search led to the realization that the right place was, in fact, where they had begun— the Colorado Desert region. Here was the center of the world, the site of creation itself. Through these songs, the Cahuilla remember the past and commemorate its significance in the present. Ritual activity connects present and past, land and people, mundane and transcendent.

The link between desert and the sacred is evident in the continued Quechan effort to create the Kw'tsán National Monument. This would set apart 380,000 acres of southeastern Imperial County, incorporating Avikwalal (Pilot Knob), Palo Verde Peak, and the (BLM) Wilderness Areas of Indian Pass, Buzzards Peak, and Picacho Peak. Indigenous advocates explain that these “are cultural spaces that hold our history and the spirits of our ancestors.” The designation as a national monument would affirm sacred tradition, promote greater cultural awareness, and ensure environmental protection, notably from mining operations. In the closing month of the Biden Administration, a new national monument was created in the Colorado Desert – applying this designation to the Chuckwalla Mountains further north. At more than 600,000 acres this new Chuckwalla Mountains National Monument is about the same size as Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. As for the Kw'tsán National Monument, advocacy must continue. This is an important effort and one that is fitting here in the Colorado Desert – the very center of the world.

Join Anza-Borrego Foundation for a season of adventure, where engaging events connect you with the stunning beauty of California's desert landscape!

Just Some of What We Offer:

Relaxing retreats

Amazing desert art classes

Guided hikes and drives at all levels

Family friendly events

Educational seminars & field trips

W. Hamber, Ph.D.

When one steps outside on a dark night, one might find that the sky above is filled with stars, but more importantly by an astonishing variety of colorful, dim celestial objects. First, the close by planets in our solar system, but then also stars and giant gas nebulae located within our own galaxy, and even further out many faint nearby galaxies. Sadly, quite often these objects are not easy to admire, in their variety of colors and shapes, either because they are too faint, or because they are obscured by haze, clouds, trees and city light pollution.

Indeed, to the naked eye, in urban skies, the night sky might not seem like anything special. But as you move far away from areas affected by intense city lighting—and further add a telescope into the equation —everything changes. The sky above you suddenly become full of amazing colorful celestial objects. Not just the nearby planets like Venus and Jupiter, but even more impressive is the variety of galaxies and nebulae with their multitude of intense colors. Thus, moving to a darker area is important, the latter can only be appreciated when the effects of city light pollution are almost completely removed, and their faint light is finally revealed against a background of almost complete darkness.

It follows that the best place for taking detailed high-resolution images of nebulae and galaxies is a place where one has few overcast days and minimal background light pollution. Not surprisingly many of these colorful yet faint sky objects become much more visible in the desert, where the air is dry and transparent, and the skies are often clear and pitch dark. Even then, the number of days available to photography are limited, as cloudy weather, high winds and moonlight can ruin the

telescope images.

Rapidly evolving technology has also played an important role. As electronic photographic equipment and imaging sensors evolved during the last decade, it has become possible to acquire sophisticated astronomical equipment, that is nevertheless light and portable enough to be carried around to different desert areas, depending of course on weather conditions and seasons.

Given these circumstances it is not surprising that, using an assortment of camera equipment, telescopes, mounts and computers, I regularly visit Borrego Springs, where the University of California Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center is located. The research center in Borrego Springs lies in a designated dark sky site, far away from city lights, and is thus ideally suited for my photography work. Exploiting the near complete darkness of the surroundings —and usually on completely moonless nights, which only last for a few days every month—I can then capture (with some patience and devotion) some strikingly colorful detailed images of nebulae and galaxies.

The study of nearby nebulae and galaxies in a dark sky environment can reveal intricate, yet still large-scale, details that cannot be revealed under lightpolluted skies.

These include, in nearby nebulae, the distribution of ionized gases, dust particles, as well as a variety of stars ranging from red giants to white dwarfs. Because of the complex chemical composition of these nebulae, which generally include ionized hydrogen (which glows in the red), ionized oxygen (which glows in the blue and green) as well as other ionized gases such as sulfur and helium, these deep sky objects can lead to spectacular colors when viewed in full glory from a dark site.

In addition, it has been possible to see faint nebulae which are remnants of a recent catastrophic star explosion, a so-called supernova. In this case the origin of the gas distribution is nearly spherical, thus giving away the original exploding star’s location. Since different ionized gases tend to travel at different speeds, one finds again that the resulting astrophysical images can be quite colorful. Again, the leftover gas remnants can be very dim, which requires extremely dark skies to be visible.

Within our own galaxy another set of clearly visible sizeable astronomical objects are globular star clusters, often compromising thousands of stars. One example is the Great Cluster in Hercules, a collection of over one hundred thousand stars, and almost as old as the Universe itself.

Finally, further out and under dark skies it becomes possible to see much fainter objects. These include nearby galaxies, which are either satellites of our own galaxy, or are a bit further out and thus part of some other nearby galaxy cluster. One example is the nearby Andromeda Galaxy, which, although very faint, is six times larger in diameter than a full Moon. Again, these galaxies exhibit an amazing variety of morphologies, ranging from spirals to edge on disks, depending also on their relative orientation. And only under dark skies can one clearly observe the extreme variety of colors within a single galaxy, ranging from the bright yellow core to the faint blue spiral arms, with bright purple star forming regions, and often dark dust lanes in between. Occasionally, if one is fortunate enough (as I was in 2023), one can even observe, for a few days, a bright supernova (an exploding star) going off in one of the nearby galaxies.

What follows is a brief description of some of the deep sky objects that are featured in the images below, all taken in Borrego Springs. Here the M number denotes their entry in the Messier catalog, first compiled by Charles Messier in 1771. The New General Catalogue (NGC) and the Index Catalogue (IC) are more recent astronomical catalogs, which list many more objects such as galaxies, nebulae, and large star clusters.

Located in the constellation Monoceros this bright Hydrogen emission nebula has a tight cluster of stars at the center. The nebula's color is mostly reddish, from the vibrant ionized Hydrogen emission. Emission nebulae are formed from ionized gases that emit light of various wavelengths, with the source of ionization usually due to ultraviolet light from a bright nearby star. Since many of these nebulae are composed mainly of Hydrogen, they tend to shine in the red. The image was obtained with an 80mm aperture refractor telescope and more than two hours exposure.

M42 in the constellation Orion is another bright emission nebula about 5,000 and 6,000 light-years away. One of the brightest and most massive star-forming regions of our galaxy, with a geometry resembling the more luminous Orion Nebula, here viewed edge-on. The star cluster NGC 6618 lies embedded in the nebulosity and causes the gases of the nebula to shine due to radiation from these hot, young stars. The image required with a 122mm aperture refractor telescope and an exposure time of more than two hours.

A large Hydrogen emission cloud in the constellation Orion, located close to the bright triple star Alnitak, which can be seen on the left. Extensive areas of dust around the deep red Hydrogen clouds create a nice sharp contrast over the Hydrogen red and give rise to the dark Horsehead shape. Dark nebulae such as the Horsehead are made of dense (molecular or interstellar) dust that obscures (partially or completely) the background stars or nebulae. The bright yellow Flame Nebula NGC 2024 can be seen on the lower left. This image was acquired with a 122m aperture refractor telescope and more than three hours of exposure.

This planetary nebula in the constellation Vulpecula is a colorful nebulosity surrounding a white dwarf, located about 1360 light-years away. Planetary Nebulae are shell-shaped regions of cosmic dust and gas that are expelled from a dying star. Here its age is estimated at only 9,800 years. From our perspective it appears shaped like a prolate spheroid, with several distinct bright and dark knots in the central region. The image was obtained with an 8-inch aperture reflector (mirror) telescope and more than three hours exposure.

M13 is in the constellation Hercules and is a large globular cluster located ca. 22k light years from us and containing around 300k stars, with an estimated age of 11.65 billion years (thus significantly less, but still quite comparable to the age of the Universe, making it very very old). Two faint galaxies are visible nearby, IC 4617 (closer to the center) and NGC 6207 (further out). The image was obtained with an 8-inch aperture reflector (mirror) telescope with a 30-minute exposure.

Located in the constellation Canes Venatici. What is seen the image is actually two galaxies colliding with each other, a large one in the front and a smaller one passing behind it. The larger M51a in the front is a large spiral galaxy about 31 million light years away and containing ca. 100 billion stars. Gravitational interactions with its galactic smaller neighbor NGC 5195 (moving behind M51a) shows the disrupting effects of mutual tidal interactions. The image was obtained with an 8-inch aperture reflector (mirror) telescope and over three hours total exposure.

M101 is located in Ursa Major about 21 million light years away and contains ca. one trillion stars. Gravitational interactions with its close galactic neighbors (in the M101 group) generated over time the rather amazing spiral arms structure. The image was obtained with an 8-inch aperture reflector (mirror) telescope and over eight hours (over several nights) total exposure.

Lately I’ve used several different telescopes to capture images of deep sky objects in Borrego Springs. Some are refractor (glass) telescopes that explore a wide field (usually a few degrees), while some others are larger reflector (mirror) telescopes that allow one to zoom into smaller, fainter objects, extending over a fraction of a degree. Of course, highly sensitive state-of-the-art cooled color cameras are needed to capture the images of faint deep sky objects, and the telescopes themselves are installed on computerized precision tracking mounts.

A more detailed discussion of various technical aspects of my setup is beyond the purpose of this article. Nevertheless, let me offer here a very brief description of the salient points of my setups.

The smaller refractor (glass) telescopes are made of very high quality, low dispersion glass, which minimizes the effects of color fringing, which can happen when a material such as glass is employed for making lenses. Multiple lens systems largely eliminate these artefacts, in my case the telescopes I use are described as apochromatic triplet lens systems.

In the case of the reflector (mirror) telescopes there is almost no glass, the optical magnification is obtained instead by the use of multiple concave and convex hyperbolic mirrors. Specifically, the telescopes I use fall under the design categories of Schmidt-Cassegrain (SCT) and Ritchie-Chretien (RC) telescopes, with the latter being the same basic optical design as the Hubble Space Telescope.

Regarding the cameras, electronic cmos imaging sensor technology has evolved immensely over the last decade, which allows one to use very sensitive, yet lightweight, photographic equipment which is able to catch almost all the photons (light) emitted by faraway nebulae and galaxies, in their full color. Typically, the efficiency of these cooled color cameras is around 80%, which means that most of the photons that are emitted from faraway nebulas and galaxies thousand, if not millions, of years ago are eventually faithfully captured by the cameras.

Finally, the computerized mounts on which the telescopes are installed need to be initially set up by entering precise data such as GPS coordinates, time and date, and altitude. This data then allows the telescope, after a proper star alignment is completed, to find and track celestial objects to an accuracy of a small fraction of a degree, and usually for a whole night, or even multiple nights.

Much of the ensuing night photography is automated. With proper tracking, images are usually taken in a long sequence of rather short exposures, usually between 10 and 30 seconds. Many of these individual pictures are taken over a period ranging from a few minutes to as much as a whole night, or in some cases even multiple nights.

Then individual short exposures are then combined — or “stacked” — by a computer program into a single, very long exposure image. Later the resulting image is cleaned up, color adjusted/white balanced and cropped, using some other sophisticated image manipulation programs.

Dark sky images can reveal spectacular color and structure details of nearby Star Clusters, Nebulae and Galaxies. The Dark Sky environment in Borrego Springs combined with the excellent available infrastructure renders the whole endeavor feasible, by relying on an ideally located telescope setup site, electrical power, wifi, internet access, and convenient lodging.

Dr. Herbert W. Hamber, Ph.D. is professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Irvine. He is a former Fulbright Fellow, and over the years he has taught a variety of graduate level courses in quantum mechanics, statistical mechanics, electrodynamics, quantum field theory and general relativity. His fields of research cover quantum field theory, particle physics, advanced computation, relativistic gravitation and quantum cosmology. Formerly he was a Department of Energy (DoE) employee in the Theory Division at Brookhaven National Lab, a staff member in the Theoretical Physics (Th) division at CERN, the European Center for Nuclear Research, and is a current member of the Institute for Advanced Studies (IAS) in Princeton NJ. He is the author of two physics textbooks, ‘Quantum Gravitation: The Feynman Path Integral Approach’ and ‘Nonpertubative Methods in Quantum Field Theory’.

He is the author of over 130 scientific publications in major refereed journals. In his spare time, he enjoys photography, driving fast cars, attending airshows and practicing deep sky astrophotography. More information can be found here or on his YouTube channel.

Youtube Channel

Michael G. Simpson, Ph.D.

“Plants can really get around. And after they get to a new place, they can change...“

Ancestors of many of the plants in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park have, in the past, traveled thousands of miles. A repeating pattern of this long-distance transport is seen among plants that occur in both North American and South America on either side of, but not within, the tropical zone. These plants are known as AADs, the acronym meaning American Amphitropical Disjuncts. "American" in this case refers to the two continents of the western hemisphere: North and South America. "Amphitropic" means on either side of the tropical zone, so roughly occurring north of the Tropic of Cancer and south of the Tropic of Capricorn. And, a "Disjunct" refers to an organism that is found far from its typical range. The Anza Borrego Desert State Park is home to many of these American Amphitropical Disjunct plants.

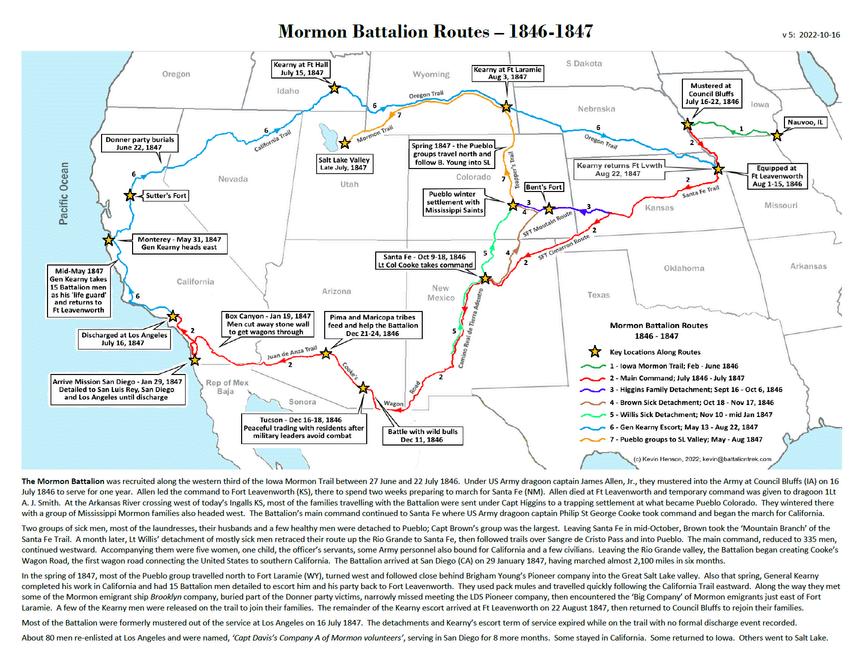

Based on a recent study (Simpson et al. 2017), a total of 237 examples of American Amphitropical Disjunct plants was tabulated. AAD plants can consist of the very same species, occurring in both North and South America, spanning either both sides of the tropics. In fact, that study found that 135 (57%) of all AAD examples are the same species. One example of this in the Park is the common Desert Fiddleneck, Amsinckia tessellata (Boraginaceae). Based on phylogenetic studies using DNA sequence data, we know that approximately 310,000 years ago this plant was transported from southwestern North America to southern Argentina of South America (Fig. 1).

A second example is Cryptantha maritima. This species is one of the most common annual plants of low elevation, "desert floor" species in the Park. But, in this case, only one of four varieties, C. maritima var. pilosa , made it from North America to a single locality in western Argentina (Fig. 2), this one a little bit more distant in time, about 920,000 years ago. Now, with a transport more distant time, the plant arriving in the new continent is more likely to diverge into a new species.

Thus, we see several examples of species pairs, one in North America, one in South America, and each the others closest relative. There are 54 examples (23% of the total) of species pairs that show the AAD pattern. One example of this is the very common Creosote Bush, Larrea tridentata ( Zygophllaceae ; Fig. 3 ), which is in fact the plant that has the greatest biomass of any species in our desert region.

But, our Creosote Bush diverged into what we call a separate species after a long-distance transport, this time from South America to North America, about 6.3 million years ago. The greater timespan enabled this species to diverge from it's closest South American relative, Larrea divaricata, found from Peru to Argentina in South America.

Finally, a transport between the continents even more distant in time can result in one or both of

the original species diverging into two or more new species on their "parent" continent. There are 48 examples (20% of the total) of a AAD "event" that resulted in speciation on one or both continents. Each of the derivative groups of species is known as a "clade." One of these examples is in the genus Hoffmannseggia (Fabaceae). In North America, this genus diverged into three species: Hoffmannseggia intricata, H. microphylla, and H. peninsularis, The second of these three, H. microphylla, the Desert Bird-of-Paradise, occurs in eastern regions of Anza Borrego Desert State Park. But, this group (clade) of three species is most closely related to another clade of two species of the genus found in South America. In this example, we do not know when the original dispersal event occurred, but we do know that it happened after a long-distance transport from South America to North America. But, in general, AAD events that result in the formation of new species (speciation) on both continents occurred further back in time, an average or 8.4 million years ago!

How do plants get from one continent to another? This has been a topic of debate for over a century. The overriding consensus, however, is that plant propagules–seeds or fruits–were carried on the feet or more likely features for a bird. These propagules have to be small and light enough to be carried, and they tend to have little barbs or hooks that can easily attach to the outside of a bird. Given that some birds can travel on migratory "flyways" for thousands of miles, this hypothesis is the most feasible. However, this still must have been a very rare event. And, if and when it happened, it would also be rare that the plant arriving to the new continent could survive and reproduce in its new home. i

species of which are common in our deserts. All Cryptantha species in North America are annuals. But, millions of years ago, a propagule of a Cryptantha ancestor was transported from North America to South America and diverged (speciated) into several species. Some of these species of South American Cryptantha shifted from an annual to a perennial plant duration. (In fact, some of these same species also shifted in chromosome number, as in Creosote Bush.) Again, we do not know the selective advantage for a plant to shift to a perennial duration. It may allow the plant to survive for a longer period of time in the absence of native pollinators. Or a shift to perennial may be environmentally related. Understanding the molecular basis of this shift may give us more insight.

A third change we notice in AAD plants is related to reproductive biology. Some AAD plants have evolved a feature known as "cleistogamy." This mechanism results in the evolution of flowers that

Finally, we note in a few examples of "clade" AADs an accelerated rate of speciation, the evolution of new species from a single ancestor. Certain studies, using DNA sequence data, can estimate how rapidly new species can form, or "speciation." In all cases, where the rate of speciation increases beyond the expected background rate, this increase occurs in a clade that arrived in the new continent. This may be the result of "adaptive radiation, a phenomenon seed in some plants (and animals) that are transported to a new environment, as in the case of AADs. The fact that there are no competitors and the fact that there are new and varied environmental habitats ("niches") available, may accelerate the formation of new species beyond what would normally occur in the parent continent. Examples of this are seen in the genera Astragalus, Locoweeds, and Lupinus, Lupines, many species of which occur in our deserts. But, in this case, the increase in speciation rate only occurred in certain South American species, following dispersal to the new continent.

Although we know much more about American Amphitropical Disjunct plants, and the changes that can occur in the new continent, much research remains to be done. Most of our knowledge of this phenomenon and the patterns that we see comes from molecular phylogenetic analyses, using DNA sequence data of many species in a group to elucidate their evolutionary tree. From these trees, or "cladograms," we can infer both the timing and the direction of dispersal between the continents. But, only about 30% of our AAD plant examples have been studied in this way. In addition, as alluded to above, we now have the tools for investigating in detail the molecular basis of the changes we see following dispersal. What effect does polyploidy, and increase in chromosome number, have on the plants survival? Is it related to other patterns we see, such as the shift to a perennial plant duration or to cleistogamy in reproductive biology. What is the mechanism allowing some groups of plants to speciate prolifically, while other plants remain relatively depauperate in species composition? We now have the tools for answering some of these questions. It's just a matter of scientists tackling them in future research studies.

Literature Cited Simpson, M G , L A Johnson, T Villaverde, and C M Guilliams 2017 American amphitropical disjuncts: Perspectives from vascular plant analyses and prospects for future research. American Journal of Botany 104:1600-1650.

Our Mission is to protect and preserve the natural landscapes, wildlife habitat and cultural heritage of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and its surrounding region for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations.

Help us spread the word about the wonders of Anza-Borrego and build future advocates for this one-of-a-kind Park. Share your knowledge and love of the park by becoming a volunteer...

“This

Linke, ABF Member & Volunteer

Scott Tremor

While driving through the desert at night, have you ever caught a glimpse of a small rodent with a long tufted tail darting across the road? Chances are you saw a kangaroo rat. Unlike many of their shy nocturnal relatives, kangaroo rats are often bold and curious, sometimes even approaching campers around a table or campfire after dark. They are native to western North America, and some species are relatively common in the San Diego region. In fact, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is home to three species, an uncommon diversity that reflects kangaroo rats’ adaptability to a wide range of desert habitats. Built for life on the move,

kangaroo rats sport oversized hind legs and long tails, perfect for their brand of saltatorial (hopping) locomotion. They are also lightning fast, capable of reacting to a rattlesnake strike in just 50-70 milliseconds. Some species are able to twist in midair and use their powerful hind legs to kick away the would-be predator.

When not evading rattlesnakes or other predators, kangaroo rats are usually foraging above ground at night in search of seeds, their preferred food, which they temporarily stash in their external cheek pouches. After foraging, the animals return their collections of seeds to their burrows and store them either underground or in small excavations around their burrows.

The Merriam’s kangaroo rat (Dipodomys merriami), widespread and common in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, has a truly extraordinary adaptation: it can live its entire life without ever drinking water. Instead, it gets all the moisture it needs from the seeds it eats. As the seeds are metabolized, water is produced as a by-product. The animal’s kidneys are also adapted to life in the desert, producing extremely concentrated urine to minimize water loss.

Of course, not every kangaroo rat manages to evade predators. When one succumbs to predation, its uneaten seeds may sprout, unintentionally helping plants to colonize new areas. In this way, kangaroo rats’ caches play an unassuming but vital role in the ecosystem, proving that even the smallest desert dwellers can make a big impact.

By Alex Tardy, B.S.

Anza-Borrego State Park is known for its extreme climate and a vast landscape. The region experiences flash flooding in the summer monsoon months, but in between storms has extreme temperatures, sometimes reaching 120°F. During the transition seasons, strong winds are common through the region as moist Pacific air dries out as it is forced down the lee side of the San Diego Laguna mountains. Because of the strong wind up to 70 mph and the desert sand, there are often dust storms and blowing sand during the high wind periods.

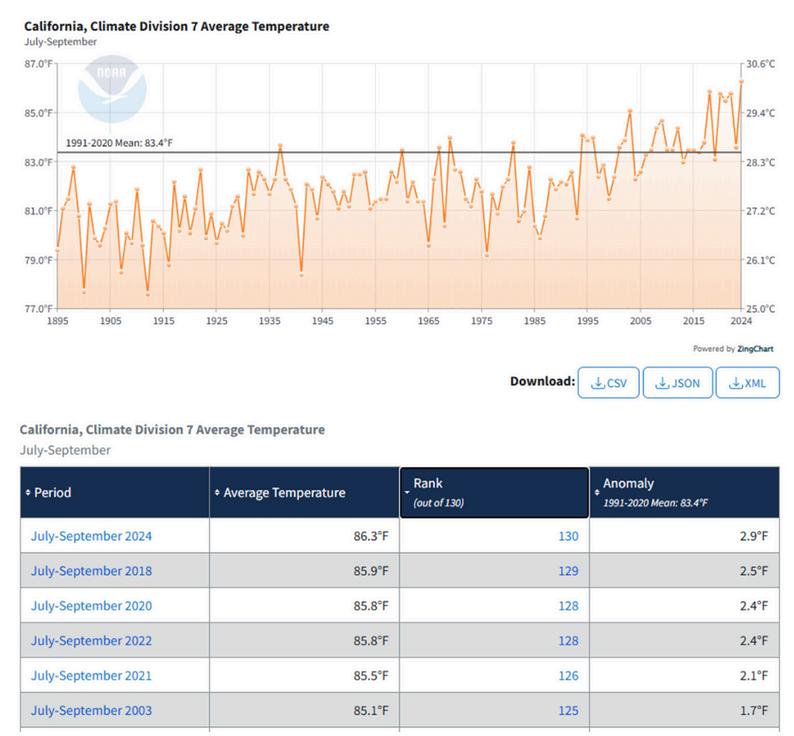

Over the past decade, there has been a trend towards less precipitation and more extreme temperatures and dust episodes. When there are thunderstorms the region can experience severe dust storms called Haboobs. Even though the region is known for hot temperatures, an increase in temperatures over 110°F has been observed across the deserts and overall warmer season from the spring and later into the fall. In the summer of 2024, there were 50 days of high temperatures 110°F or higher, which is only second to 1990 which had 52 days. NOAA records a 24-hour low temperature and high temperature and this is used to develop a daily, monthly and yearly average for climate reports. July 2024 was the hottest month on record averaging 97.5°F (average uses the low and high temperatures in a 24-hour period). This surpasses the

previous hottest month on record in July 2006. So far 2024 is the warmest year on record at the Anza-Borrego State Park and all the top 10 warmest are since 2012. The heat continued through October (October 6 was the warmest average daily temperature recorded in the month at 96.5°F) with one day reaching a high temperature of 111°F. The alltime high for October was set in 1980 at 113°F. Minimum temperatures set records for the first week of October ranging from 79 to as warm as 83°F. On September 6, one of the highest minimum temperatures was recorded at 92°F. Despite all these hot temperatures, last year the 9th wettest day on record occurred on August 20, 2023, with tropical cyclone Hilary.

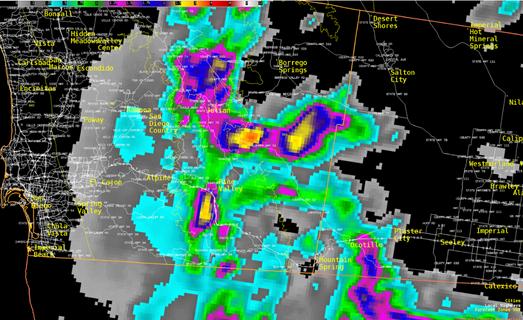

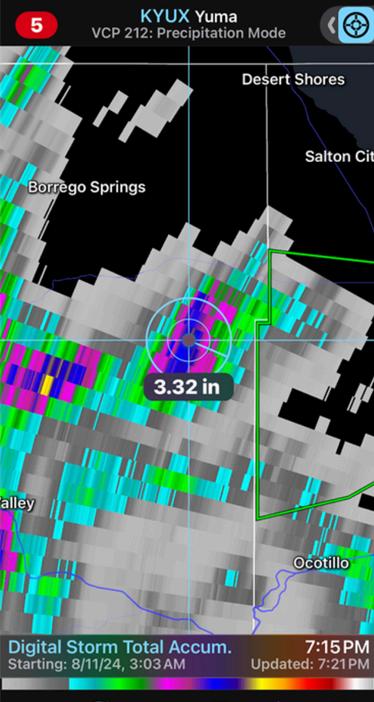

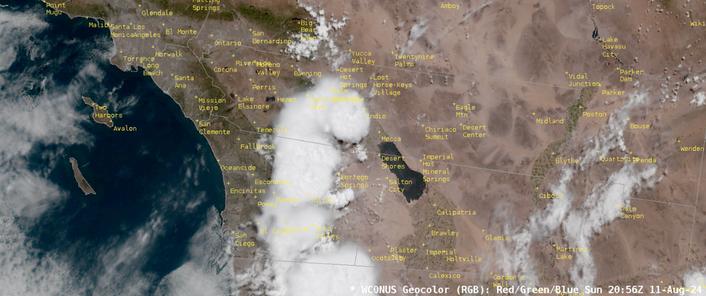

The National Weather Service has worked with the Anza-Borrego State Park and Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center to develop flash flood predictions in the Fish Creek drainage. In August 2024 this region experienced intense thunderstorms over the higher terrain and flash flooding descended through the Fish Creek access road and drainage, washing out portions of Split Mountain Road at the Imperial County line. Hydrologic modeling predicted water levels as high as 5 feet, which was observed by Sicco Rood of the Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center. Thunderstorms are not the only rainfall challenge in this desert country and occasional strong atmospheric rivers with deep moisture will penetrate over the

NWS radar mosaic (blended) estimated rainfall (radar and gauge based) on August 11, 2024.

NWS model (USDA Kineros) on August 11, 2024 predicting maximum water levels of 5 feet on Fish Creek.

Radarscope KYUX (Yuma) radar estimated rainfall of 2 to 3 inches of rainfall on August 11. Thunderstorm satellite imagery from NOAA GOES on August 11, 2024.

Thunderstorm satellite imagery from NOAA GOES on August 11, 2024.

Hottest average temperature July to September 2024, for southeast California deserts.

By Eva Sofia Horna Lowell, MS.

Scientists have documented a dramatic decline in insect biodiversity, part of which can be traced back to human activities that have negatively impacted the environment. California, one of the world's biodiversity hotspots, is home to tens of thousands of pollinator and insect species. This tremendous insect diversity can make it prohibitively difficult and expensive to measure their biodiversity by traditional methods, such as identifying and counting insects under a microscope. Although terrestrial vertebrates are relatively more studied and identified in California (see CDFW, 2016, Complete List of Amphibian, Reptile, Bird and Mammal Species in California), the same cannot be said for insects. This "Insect Apocalypse" is more devastating to California because it can lead to the loss of pollinators, which harms California agriculture, more frequent pest invasions, and perhaps most apparent is the decline of the beautiful Monarch butterflies, Hermes Copper butterflies, and many more special insects.

In the summer of 2022, the San Diego Natural History Museum (SDNHM) was awarded a grant to participate in the California Insect Barcode Initiative (CIB). Along with seven other institutions across California (California Academy of Sciences, UC Berkley, USDA, UC Davis, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, UC Riverside, and San Diego Natural History Museum), this statewide project aims to build a comprehensive DNA barcode library for every insect in the State of California (which is no easy feat given that we don't even know how many tens of thousands of insect species occur in the State).

What is a DNA barcode library? DNA barcoding is a technique used to identify and classify living organisms, in this case, insects, using a short, standardized gene within their DNA. Think of the gene like a barcode on a product in a grocery store—it provides a unique identifier that helps distinguish one species from another. More specifically, DNA barcodes are assigned to a "BIN," and we can think of each "BIN" as a species.

Along with creating a comprehensive insect DNA barcode library, we aim to document insect diversity and distribution throughout the State. To accomplish these goals, we not only used insect samples we collected from the field, but we also used identified specimens from historical entomology collections.

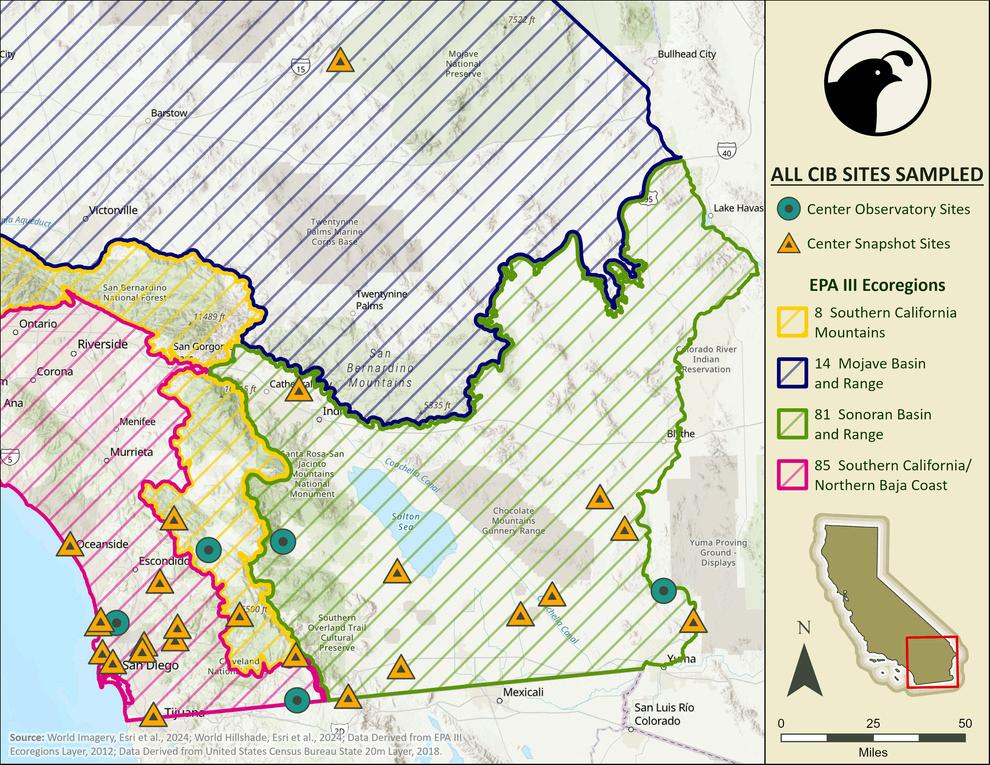

SDNHM received an award to focus surveying efforts on southern California, specifically San Diego and Imperial Counties. We sampled 28 sites covering the area's three different EPA level III ecoregions, ensuring we captured as much diversity as possible (Figure 1). We had two different types of sites: "observatory sites" and "snapshot sites." The five observatory sites we established were long-term (one year), and we sampled monthly for one week. Our remaining 23 snapshot sites were short-term opportunistic sampling sites, and we sampled only once for seven days. At all our observatory sites, we deployed malaise and blue vane traps (Figure 2) so that we could systematically look at insect diversity over time. Malaise traps target all flying insects, whereas blue vane traps target bees and wasps. Pollinators are attracted to blue vanes because they mistake the blue and yellow colors for flowers. We used different sampling methods at both observatory and snapshot sites depending on the vegetation, habitat, and taxa we wanted to target.

We established one of our observatory sites at the UCI Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Station. We specifically chose this locality, which borders Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, because of the need to document the large insect diversity in the desert and wellmanaged and preserved California State Parks. We began sampling in November 2022 and finished sampling in November 2023. During these 12 months, we collected 23 samples from malaise traps, blue vane traps, UV light sheets, and hand collecting. These samples were processed back at the SDNHM Entomology department. The processing entailed hundreds of hours of sorting and counting specimens in the samples before we sent them off to our collaborators at the University of Guelph for DNA sequencing. We have received most of our data back except for some of our November 2023 data.

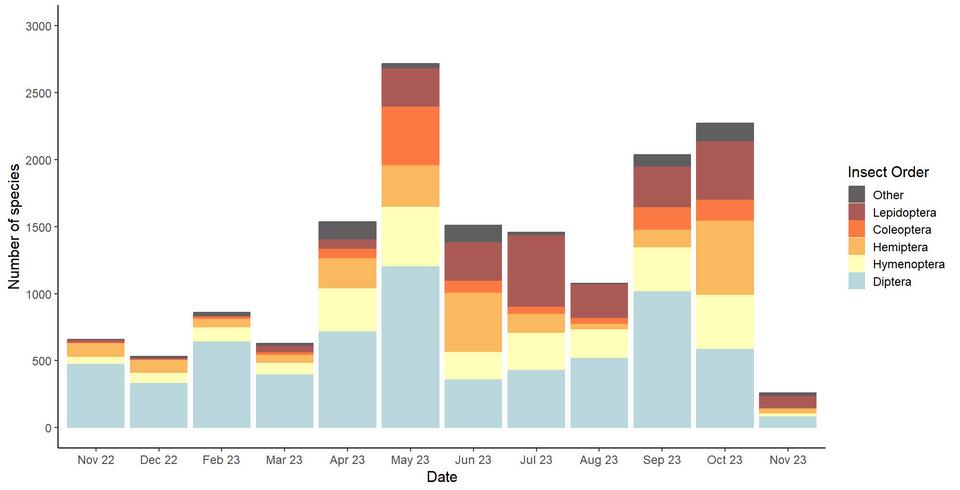

We collected approximately 15,000 specimens over the 12 months, highlighting the vast number of insects that live within Anza-Borrego. Out of these 15,000 specimens, we documented over 1,800 species. Remarkably, only 79 of these 1,800 species have identifications. This could mean that only 79 of these species have ever been described, and/or no one has ever returned to match the DNA barcode to the already described species from which the sample was taken. Either way, as entomologists, we have a tremendous amount of

work ahead of us to match these DNA barcodes to identified species. Using the DNA barcode data, we looked at the change in insect diversity over time and found some interesting patterns (Figure 3). We found variations in the number of species belonging to each Order depending on the month. As expected, insect diversity in Anza-Borrego peaked during the spring month of May. Still, perhaps unexpectedly, diversity remained relatively high throughout the summer and early fall. Rainfall the previous winter is often a good indicator of insects, particularly pollinator, diversity the following year. From July 2022 to June 2023, Borrego Springs received 8.05 inches of rain. The last year to record that amount of rain was 2019-20, which received 8.34 inches, followed by 2004-05, which rained 12.31 inches (data taken from the Steele/Burnand weather tower station). Lots of rainfall can lead to abundant floral resources, greatly benefiting pollinators and other insects because they have more flowers to feed on. In March of 2023 alone, Borrego Springs received 2.32 inches of rain, a relatively large

amount compared to previous years. Perhaps this also suggests there were more plants in summer and early fall, and insect diversity was high in summer and early fall because they had more floral resources to feed and reproduce.

Across all the different Orders of insects we sampled, five had the highest number of species: Diptera (flies), Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants), Hemiptera (leafhoppers), Coleoptera (lady beetles, stink beetles), and Lepidoptera (butterflies). Diptera, commonly known as flies, were consistently the most abundant throughout the year (Figure 7). One interesting fly species in Anza-Borrego is Copestylum apiciferum (Figure 4). Copestylum is one of the largest groups of hoverflies in America, and even more interesting is that the adult flies only lay their eggs in decaying cacti, where the larvae live until they mature into adults. We also captured a high diversity of bees, wasps (Order, Hymenoptera), moths, and butterflies (Lepidoptera), which depend highly on floral resources for food and reproduction. San Diego County alone has over 650 species of bees, many of which we can find in Anza-Borrego and throughout the desert (Figure 5, 6).

Moving forward, we plan to examine further what environmental variables, like rainfall, temperature, radiation, wind, etc., could correlate with insect abundance. Just as important is the need to return to the physical insects from which the DNA samples were taken and identify them further to Genus or Species so that more of the DNA barcodes in these massive databases have identifications.

a