A n t h o n y F e r r i wayfinding, urban design, and selected works

Photo by Anthony Ferri

Photo by Anthony Ferri

A n t h o n y F e r r i wayfinding, urban design, and selected works

Photo by Anthony Ferri

Photo by Anthony Ferri

Awards and Recognition

Selected Publications and Presentations

Hello there,

My passion is connecting the dots of complex problems I have a deep passion for both science and art, finding inspiration in the intersection of analytical inquiry and creative expression. This is why wayfinding as a subject is so interesting to me. It involves a subtle art of guiding people through physical spaces with clarity and ease. But also requires a thorough understanding of place and flow With a keen eye for detail and a deep understanding of human behaviour, I excel in creating intuitive navigation systems that seamlessly blend functionality with aesthetics By carefully studying the unique characteristics of spaces, I tailor my designs to harmonise with the surrounding architecture and geography, ensuring a cohesive and immersive experience for users

I recognise that effective wayfinding is not just about signage; it's also a fundamental aspect of placemaking and urban design. By integrating wayfinding solutions into the fabric of a city or community, I contribute to the creation of vibrant, liveable spaces where people feel connected and engaged Through innovative design solutions, connecting digital ideas to physical realities, and detailed and thorough planning, I help to empower individuals to explore their surroundings with confidence and discover hidden gems along the way.

Whether it's guiding visitors through small indoor spaces or helping pedestrians navigate large and complex cityscapes, I take pride in my ability to create impactful wayfinding experiences that enhance both the physical environment and the lives of those who choose to explore it.

Kind regards.

Anthony Ferri Photo by Anthony Ferri

Photo by Anthony Ferri

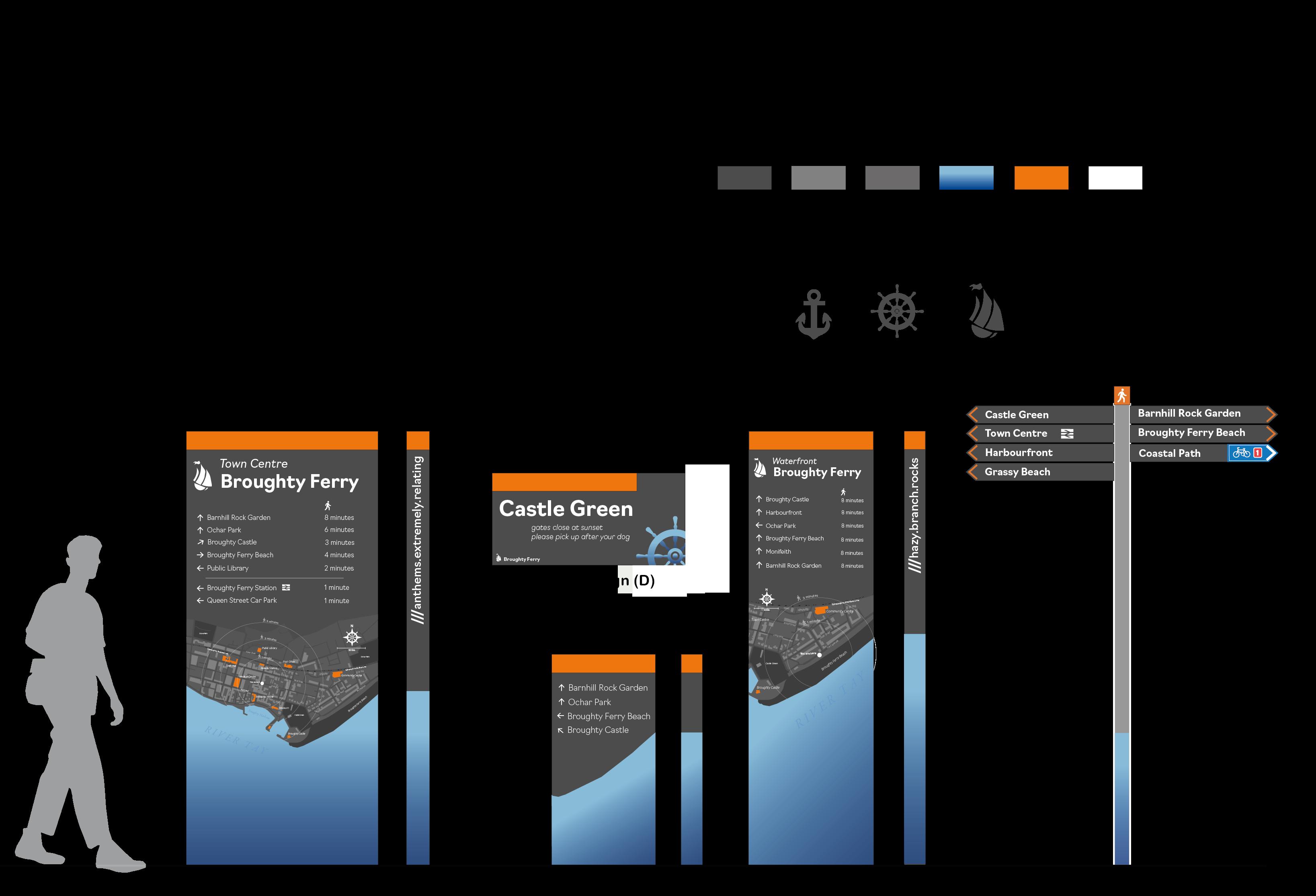

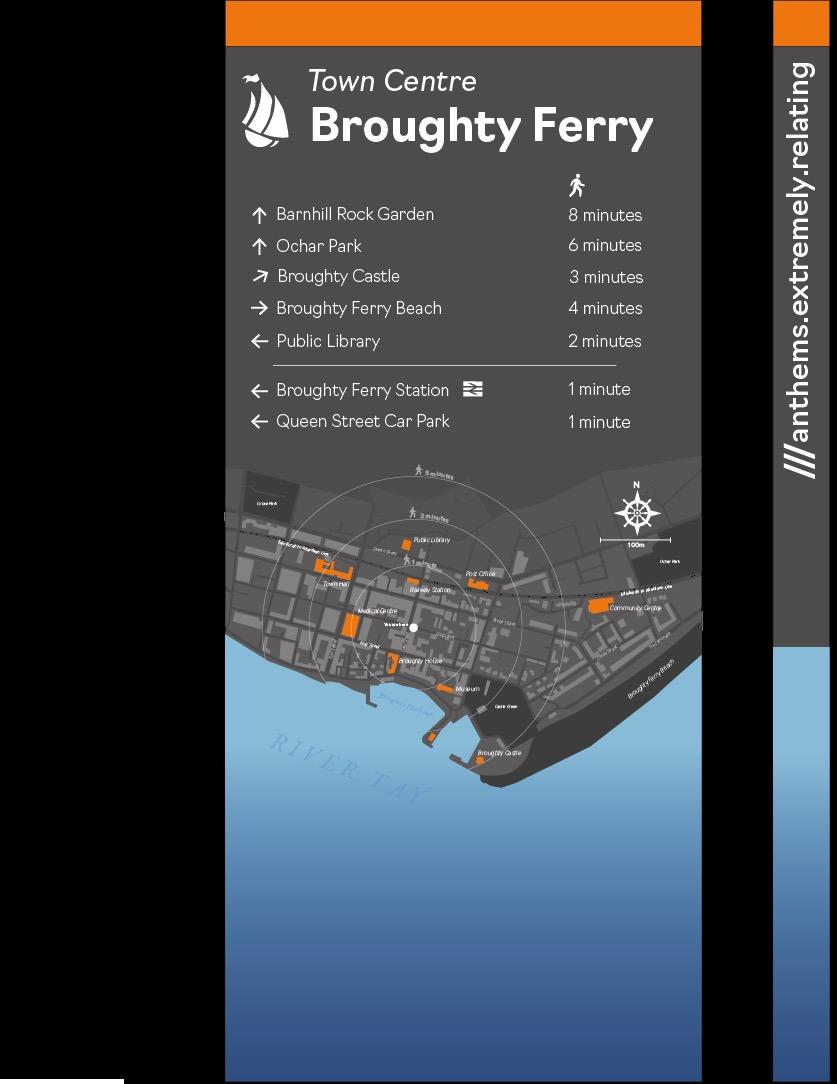

This Concept Design presents an exciting opportunity to revitalise wayfinding within the beautiful town of Broughty Ferry. Broughty Ferry is located east of Dundee and sits on the north bank the River Tay. An historic fishing town, Broughty Ferry offers people a chance to experience a variety of cafes and restaurants, explore local beaches and coastal paths, and enjoy the refreshing waters of the Tay. The proposed wayfinding family of signs is made up of five distinctive types: Plinths, Waymarkers (both large and small), Destination Signs, and Fingerpost Signs.

These sign types would complement the character of the town and provide enough detail for navigability. All signs are clean and contemporary, providing a high -quality and unified system. The primary material suggested for the signs is recycled aluminium as it provides excellent durability and longevity.

The design also incorporates the look and feel of Broughty Ferry through colour. The chosen colour palette encompasses both cultural and navigational meaning and helps to draw attention and

I led a team of designers in developing a wayfinding strategy to enhance Barnstaple’s Town Centre’s legibility. The work proposed wayfinding interventions and associated public realm improvements, including both public art enhancements and transport accessibility upgrades to support improved arrival, navigation, and overall legibility of key destinations in the town centre.

The outputs of the commission included a comprehensive wayfinding and public art strategy, a series of high -quality descriptive maps illustrating existing and proposed wayfinding provisions and public art instalments, as well as a family of signs, wayfinding indicative design details and graphical artwork, and a schedule for sign placement.

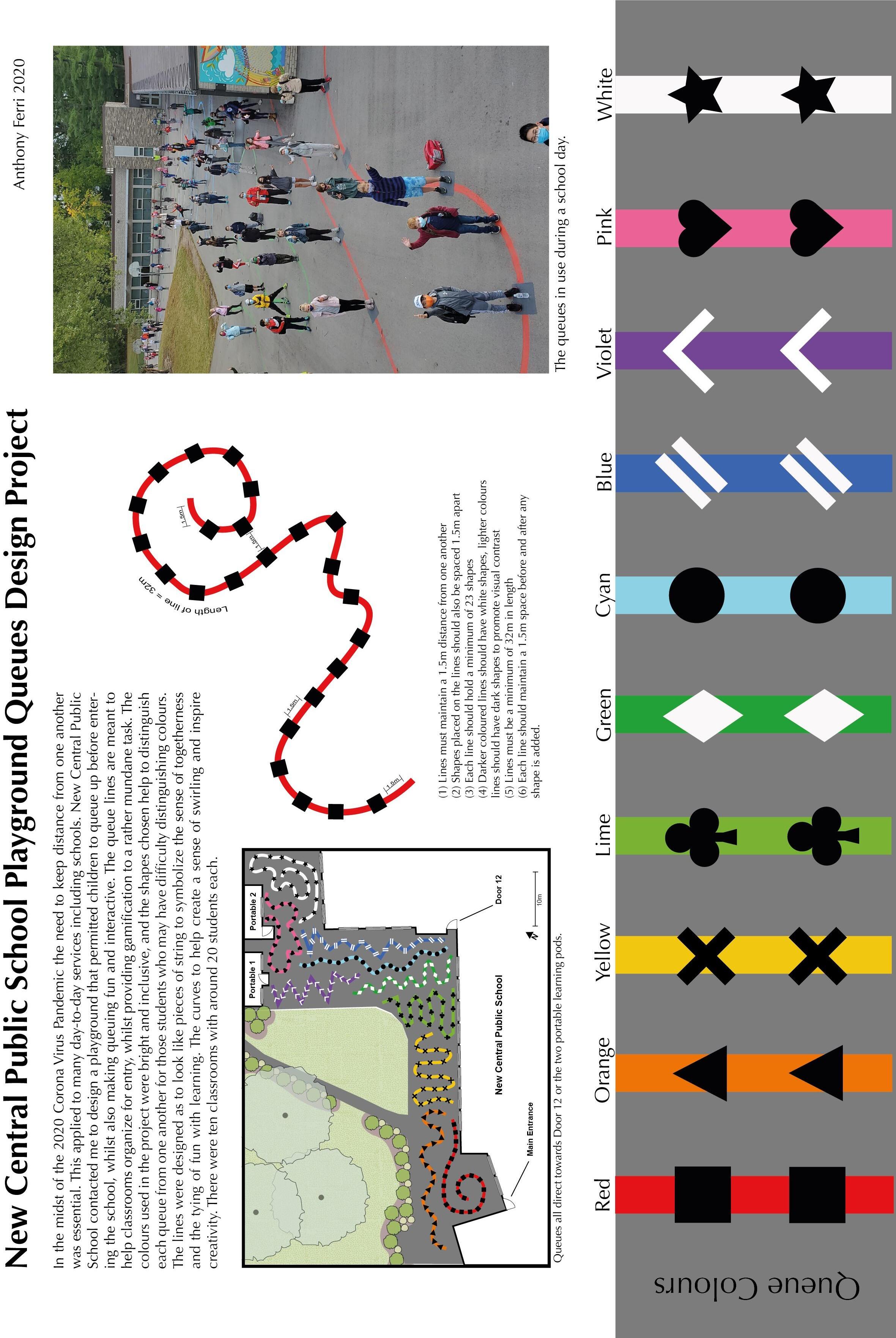

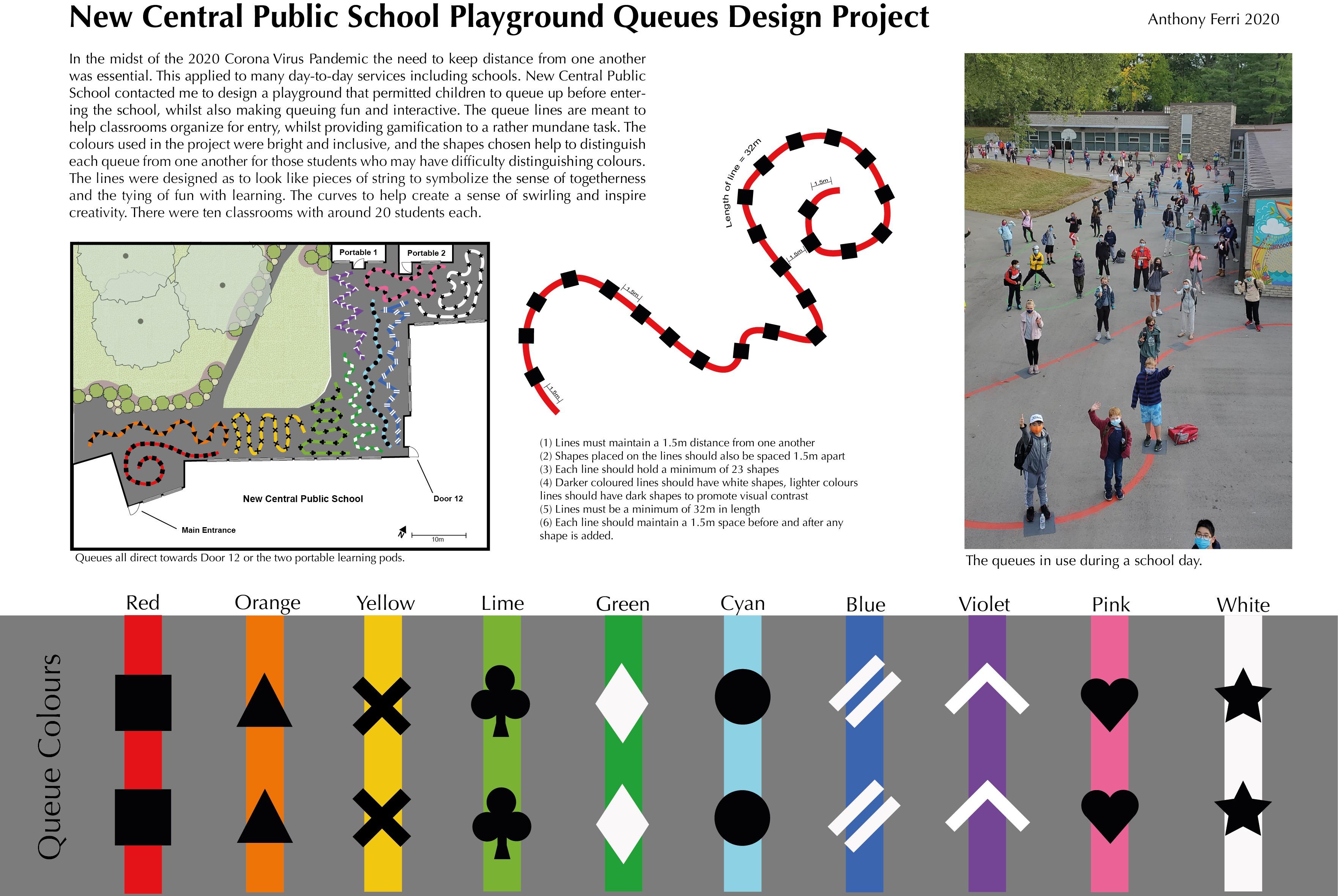

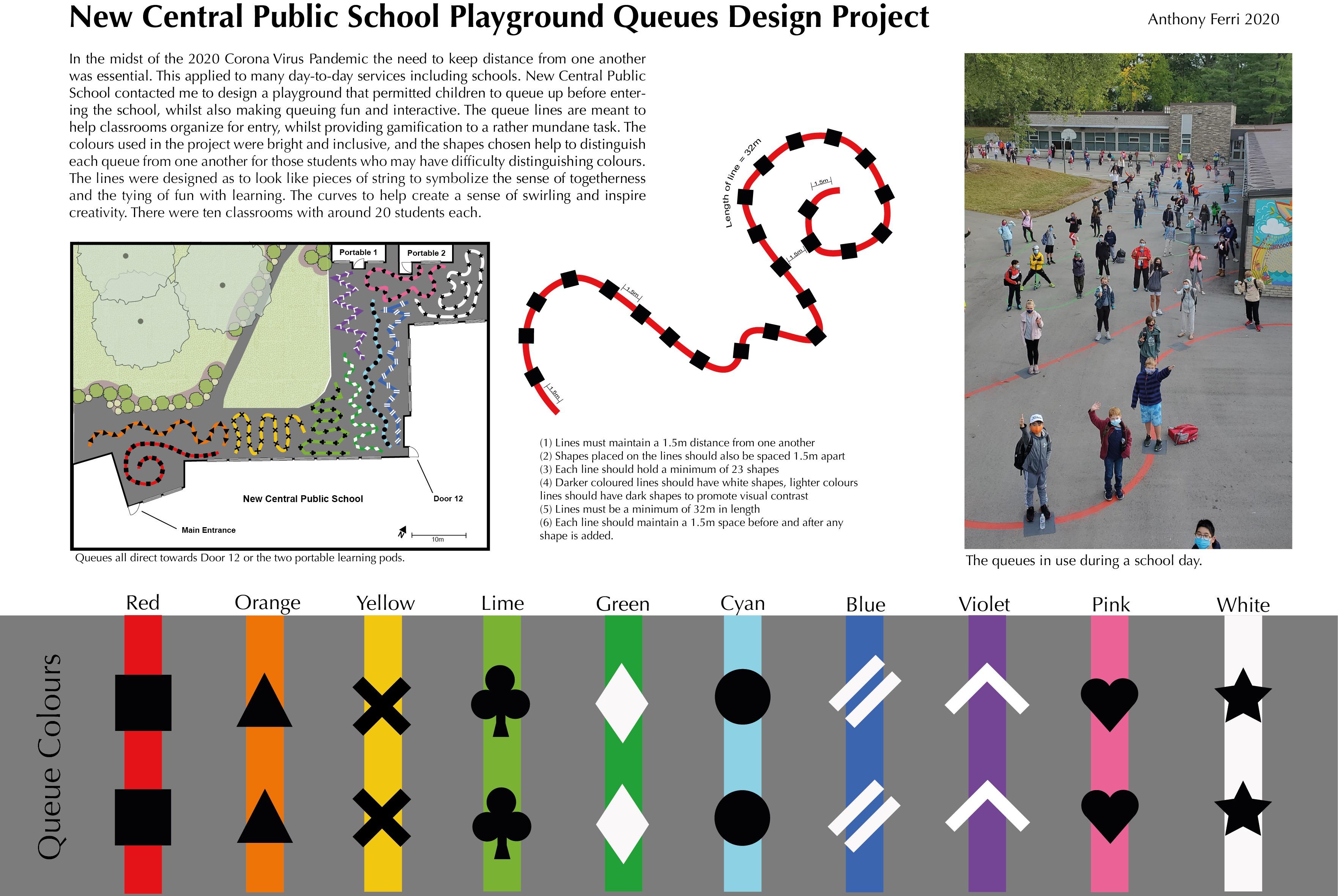

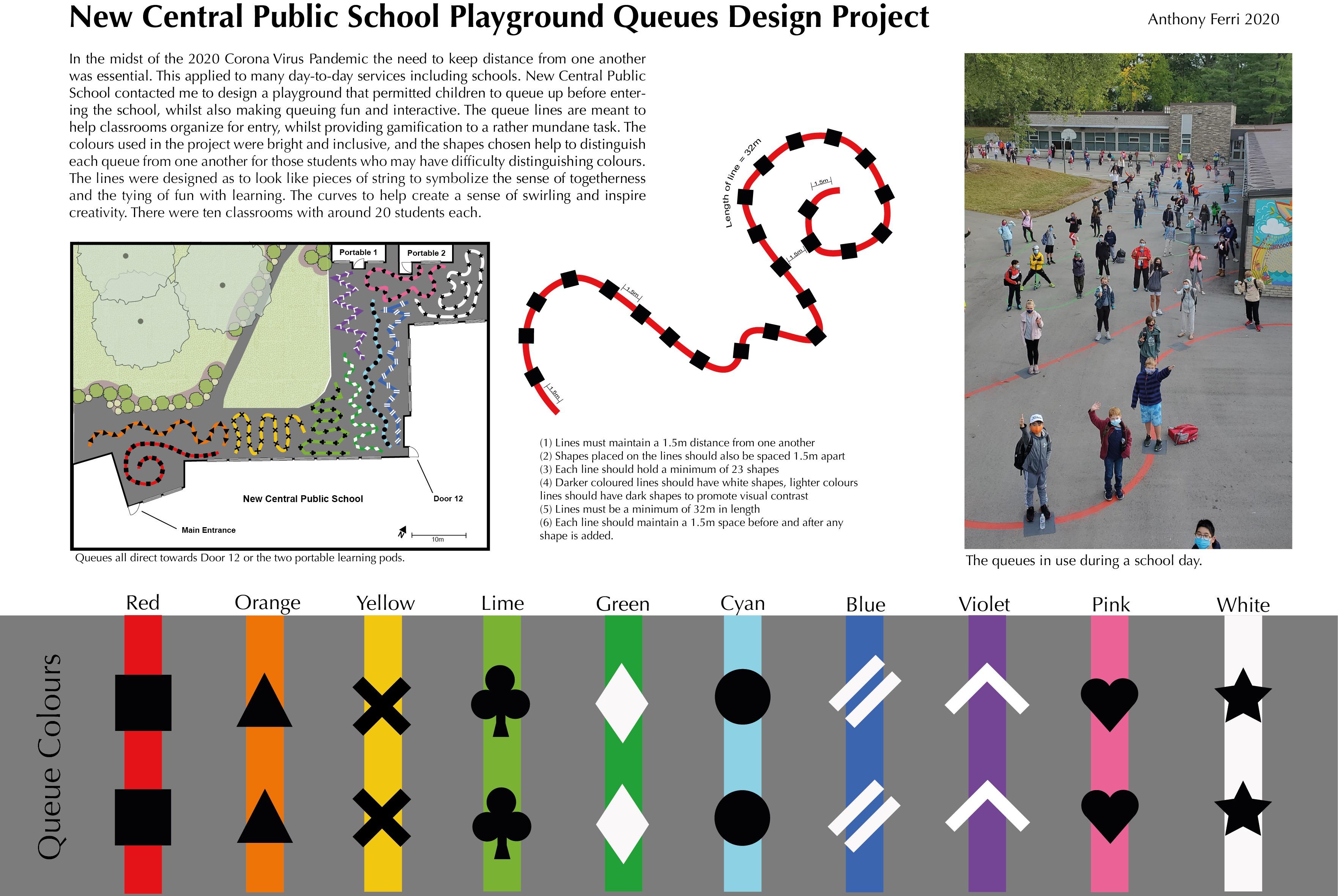

During the 2020 Corona Virus Pandemic the need to keep distance from one another was essential. This applied to many day school time activities. New Central Public School contacted me to design a playground that permitted children to queue up before entering the school

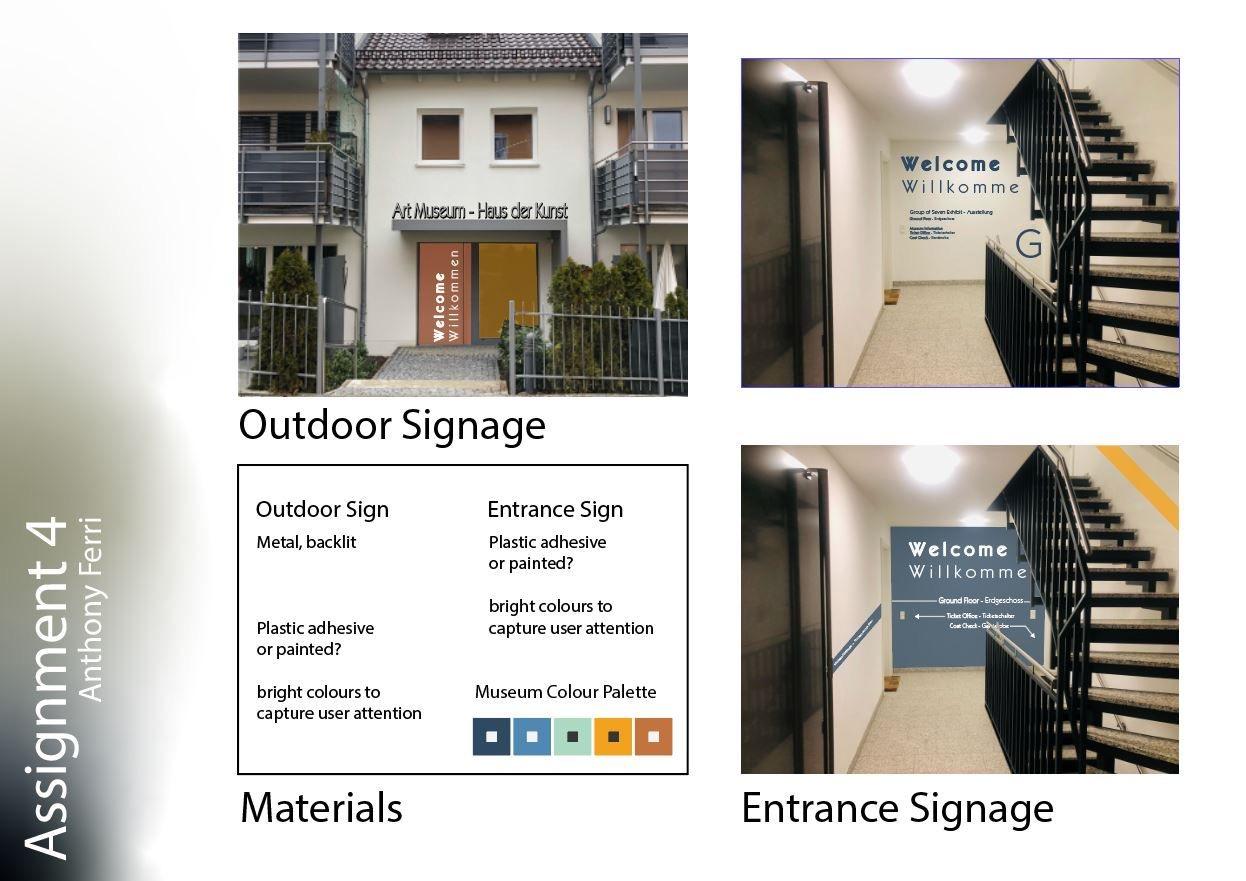

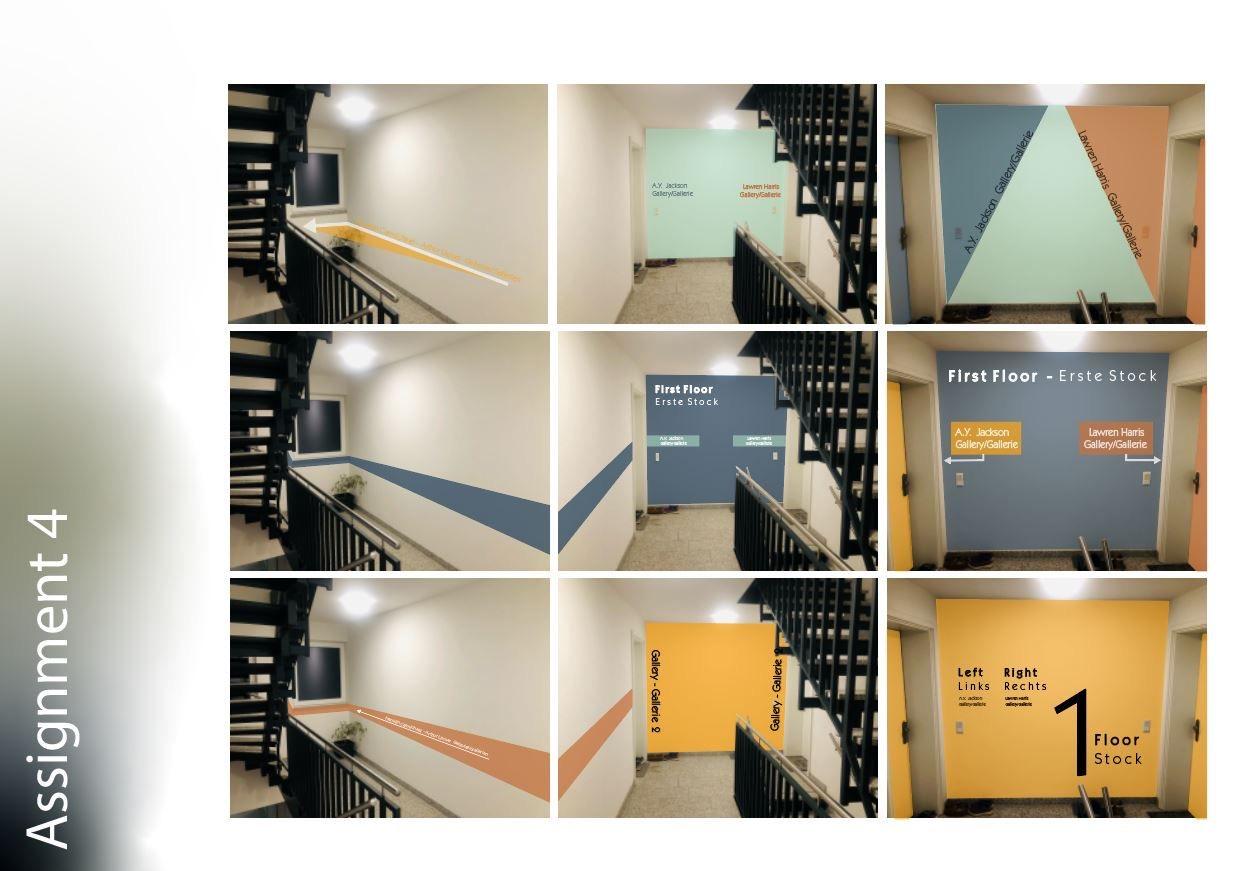

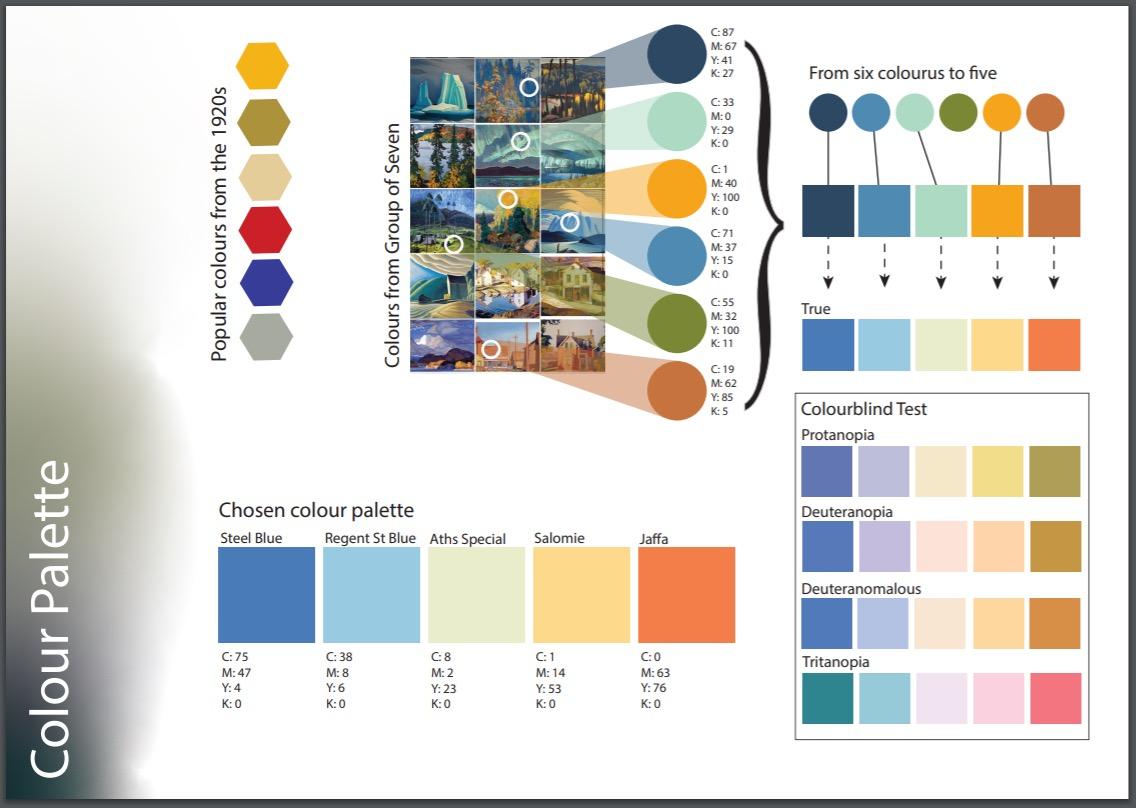

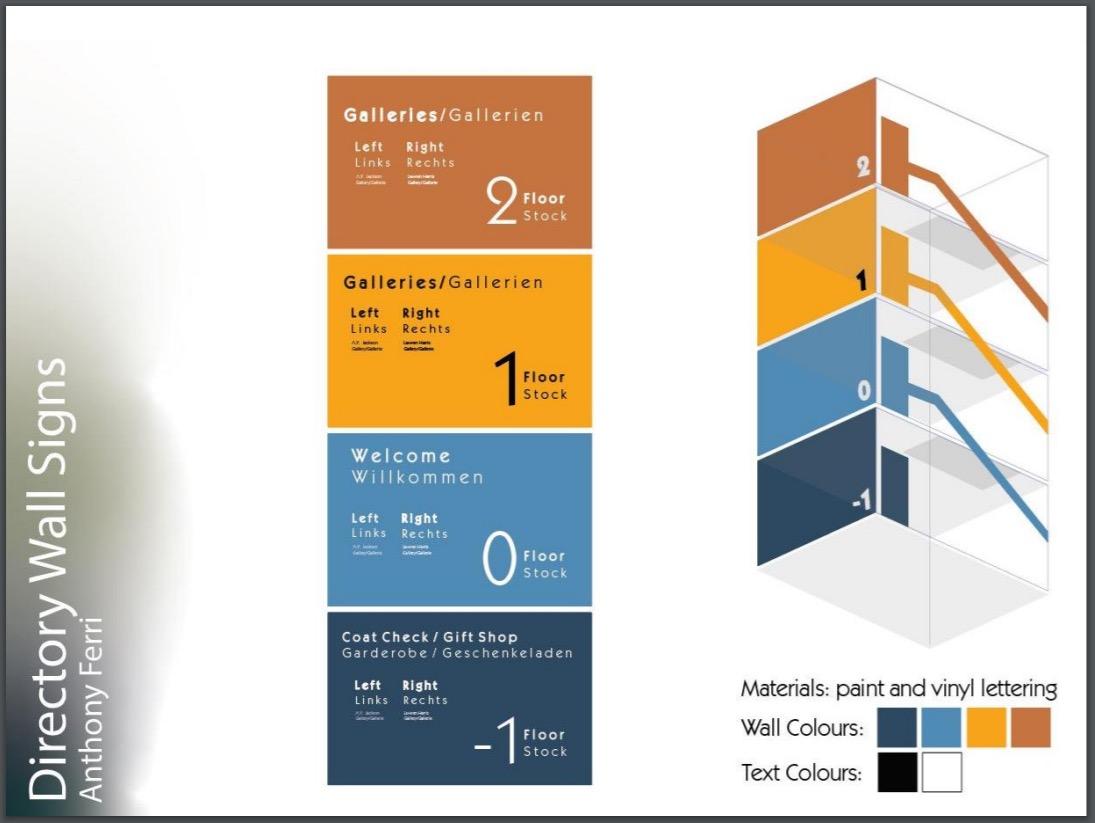

Part of the Wayfindnig Design short course program at the University of Arts London, required us to re -design a small living -space into a museum setting and create a wayfinding visual identity for the space. I chose the housing complex I lived in as my potential "museum space". I developed a colour palette based off he early 1900s artist collective The Group of Seven’s artwork.

The colours were checked to see if they were visually accessible and then applied to mock -ups for a final decision.

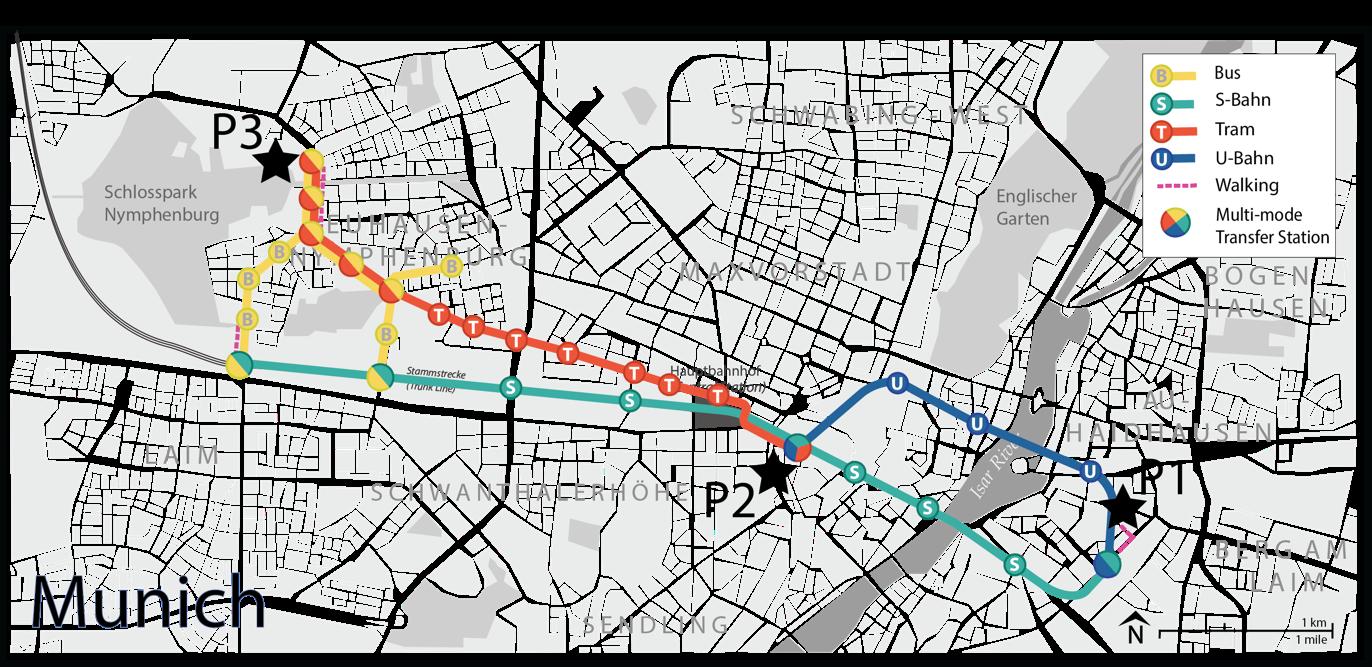

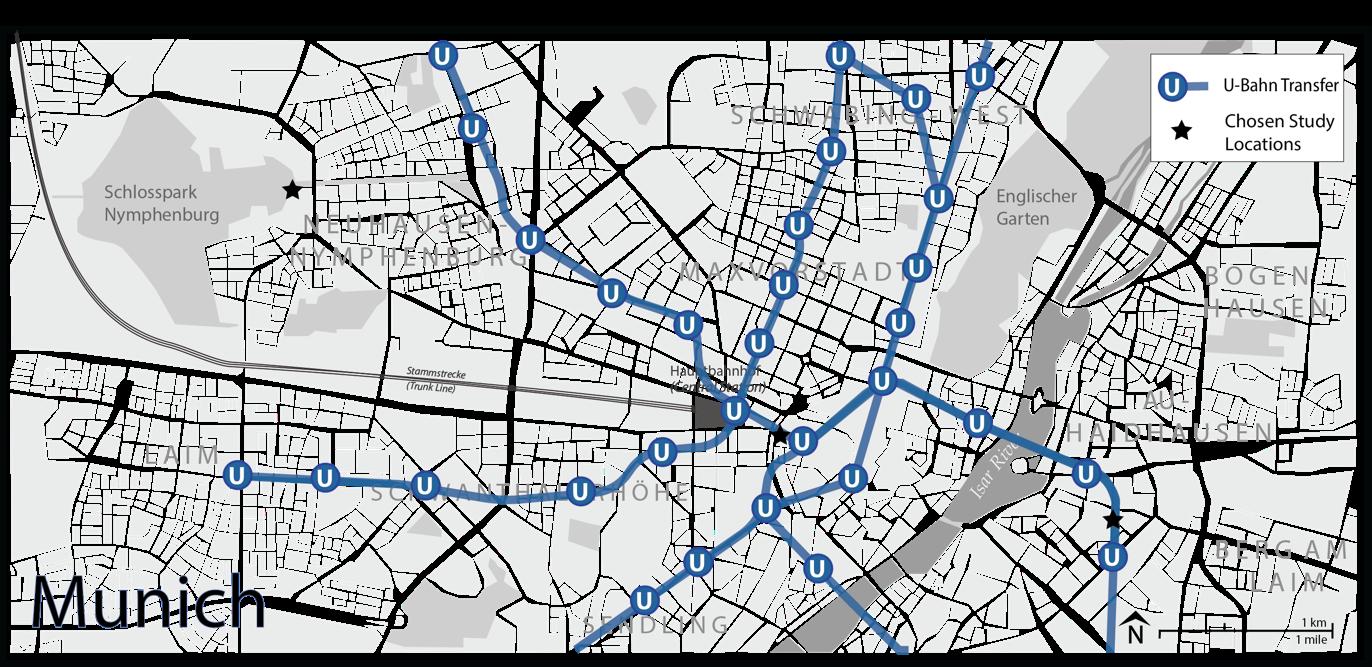

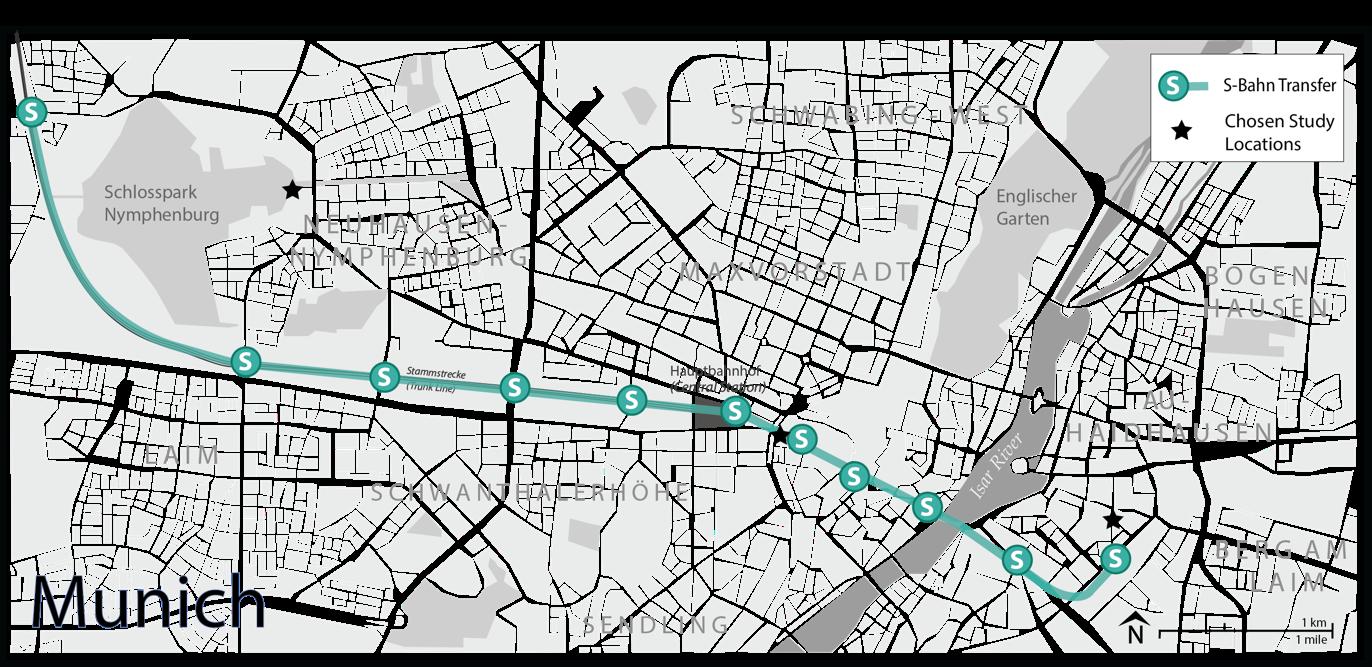

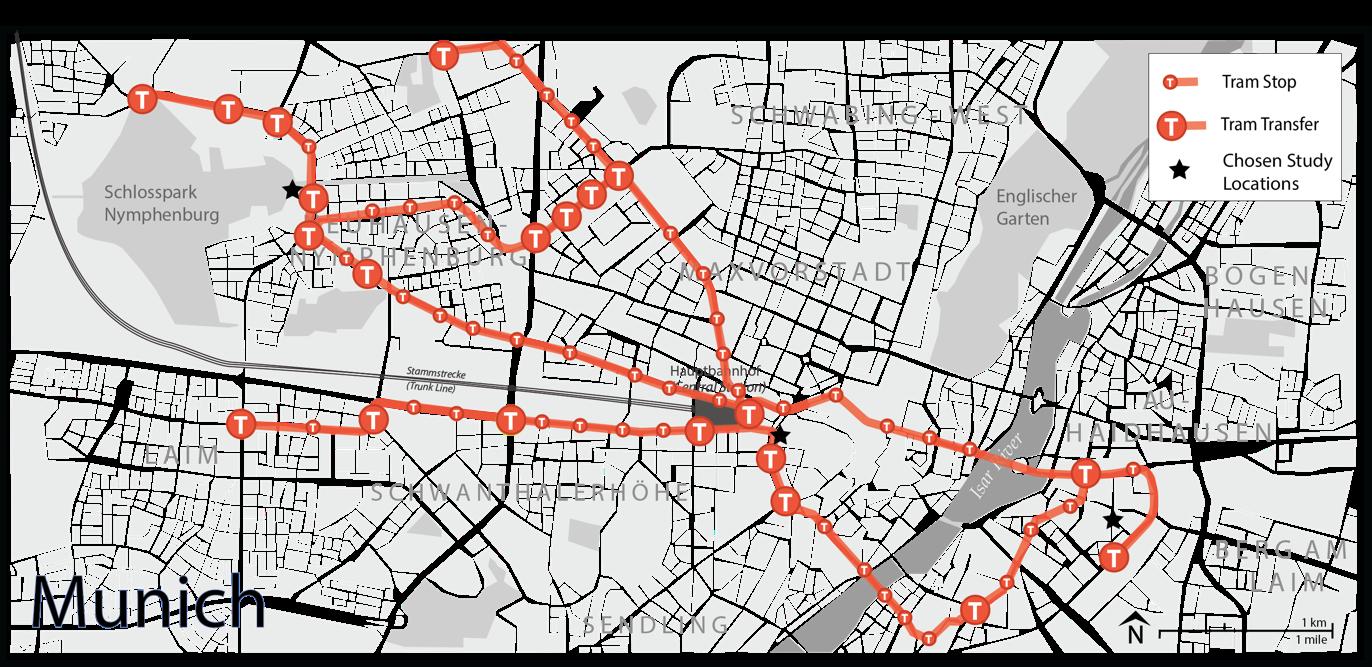

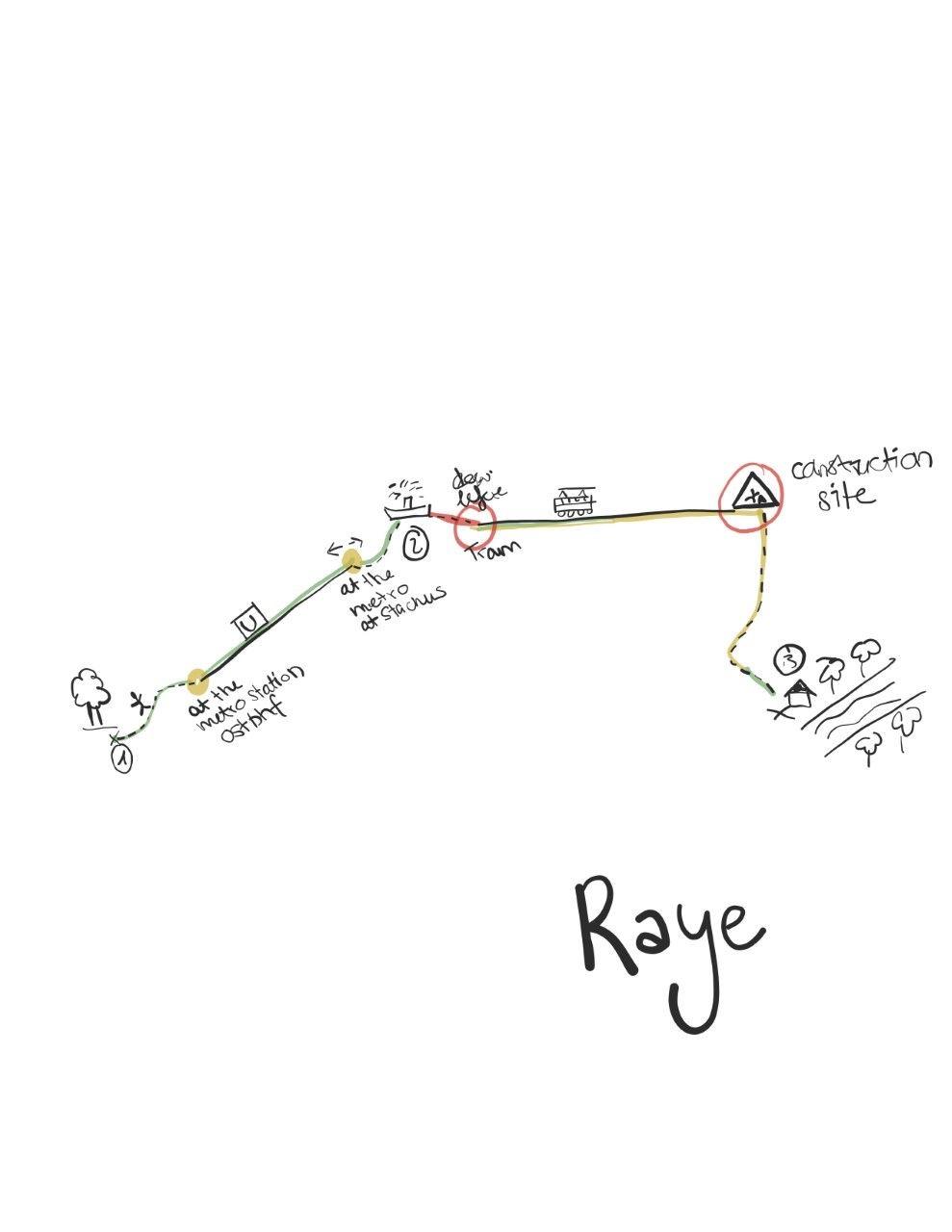

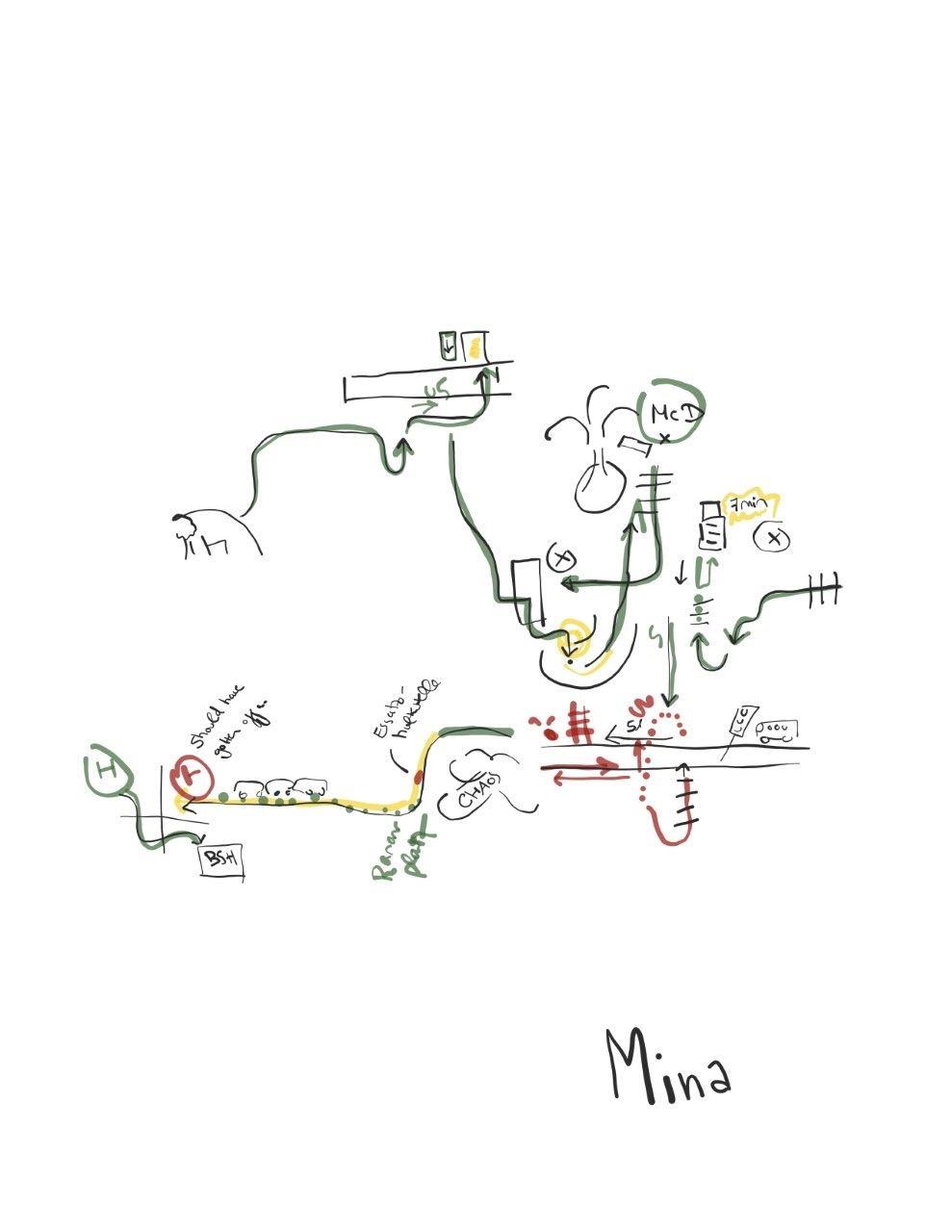

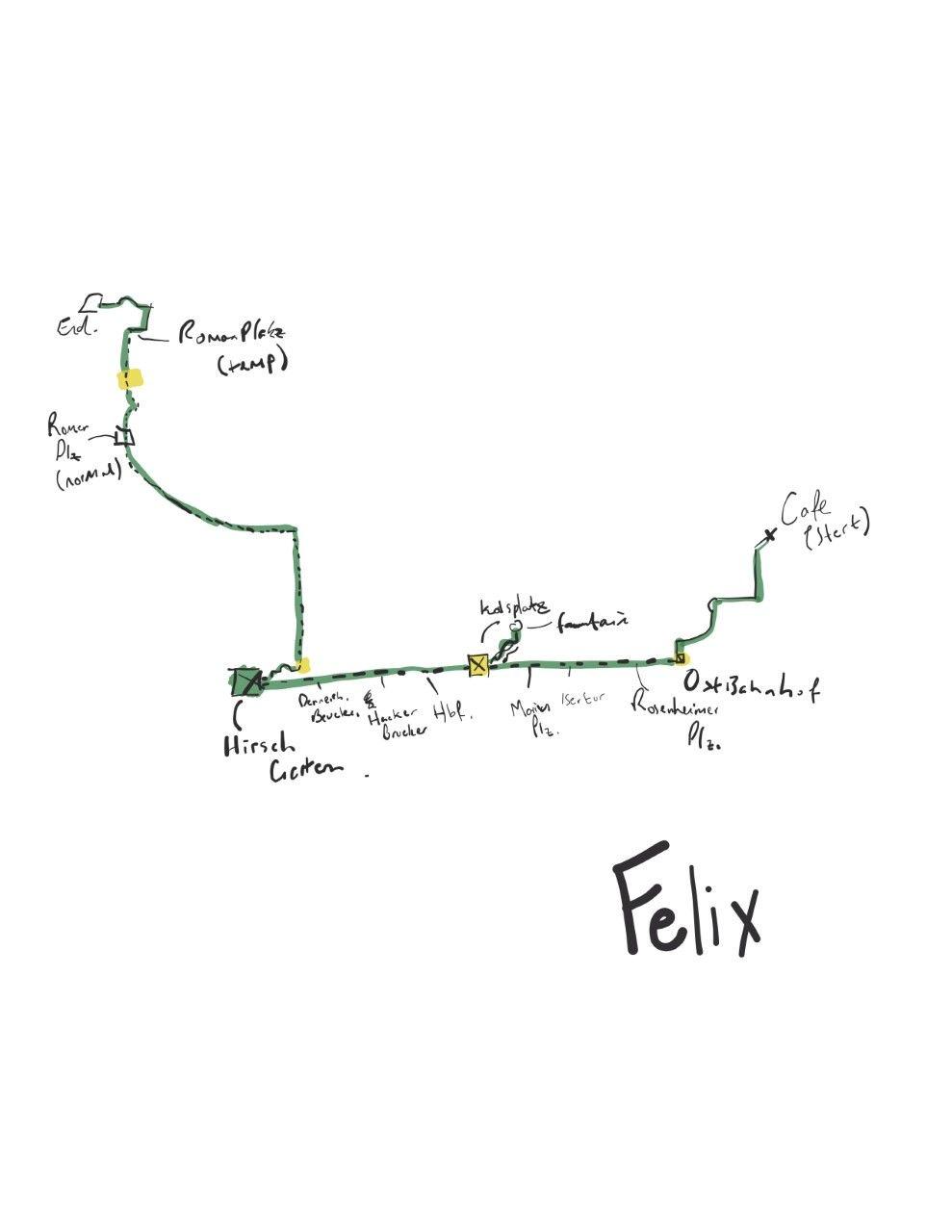

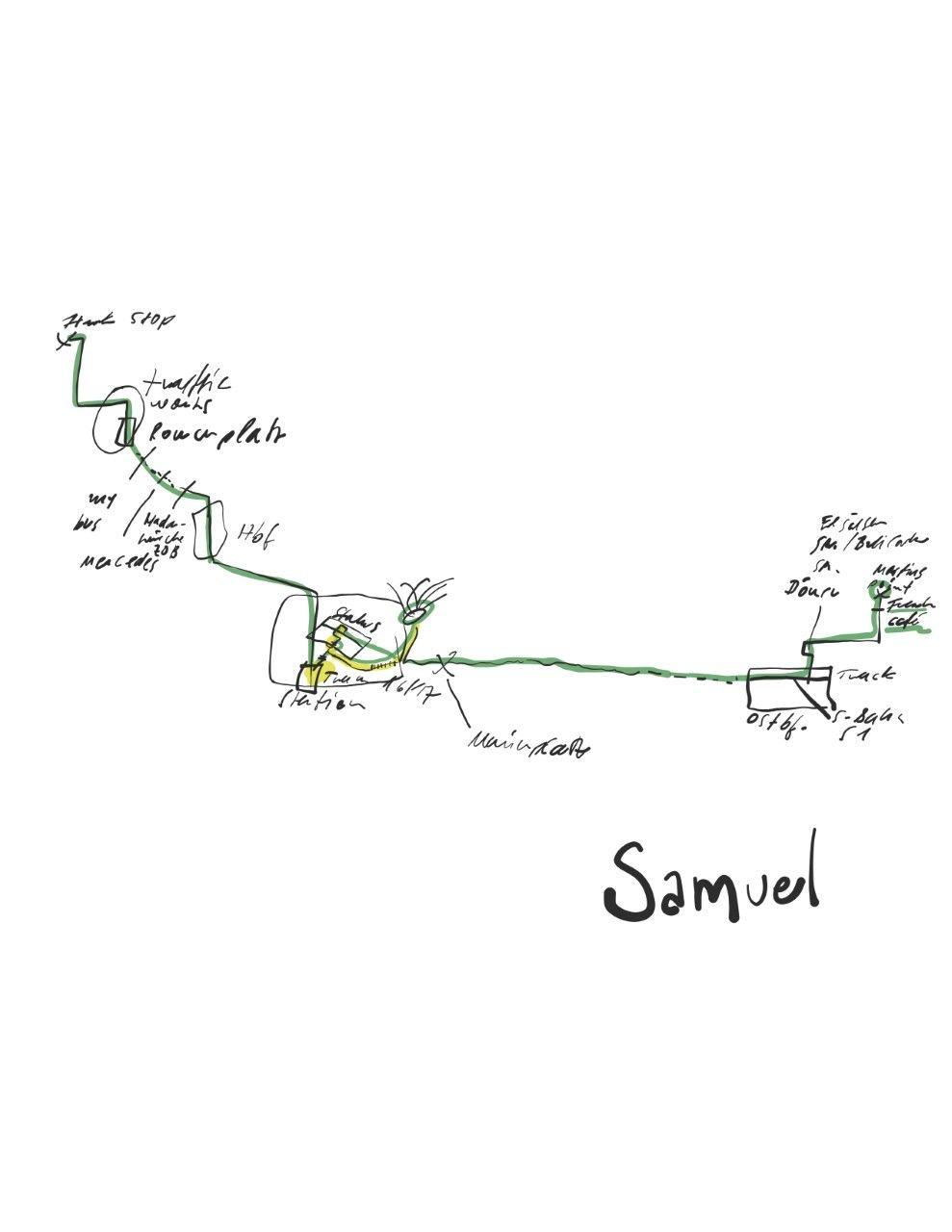

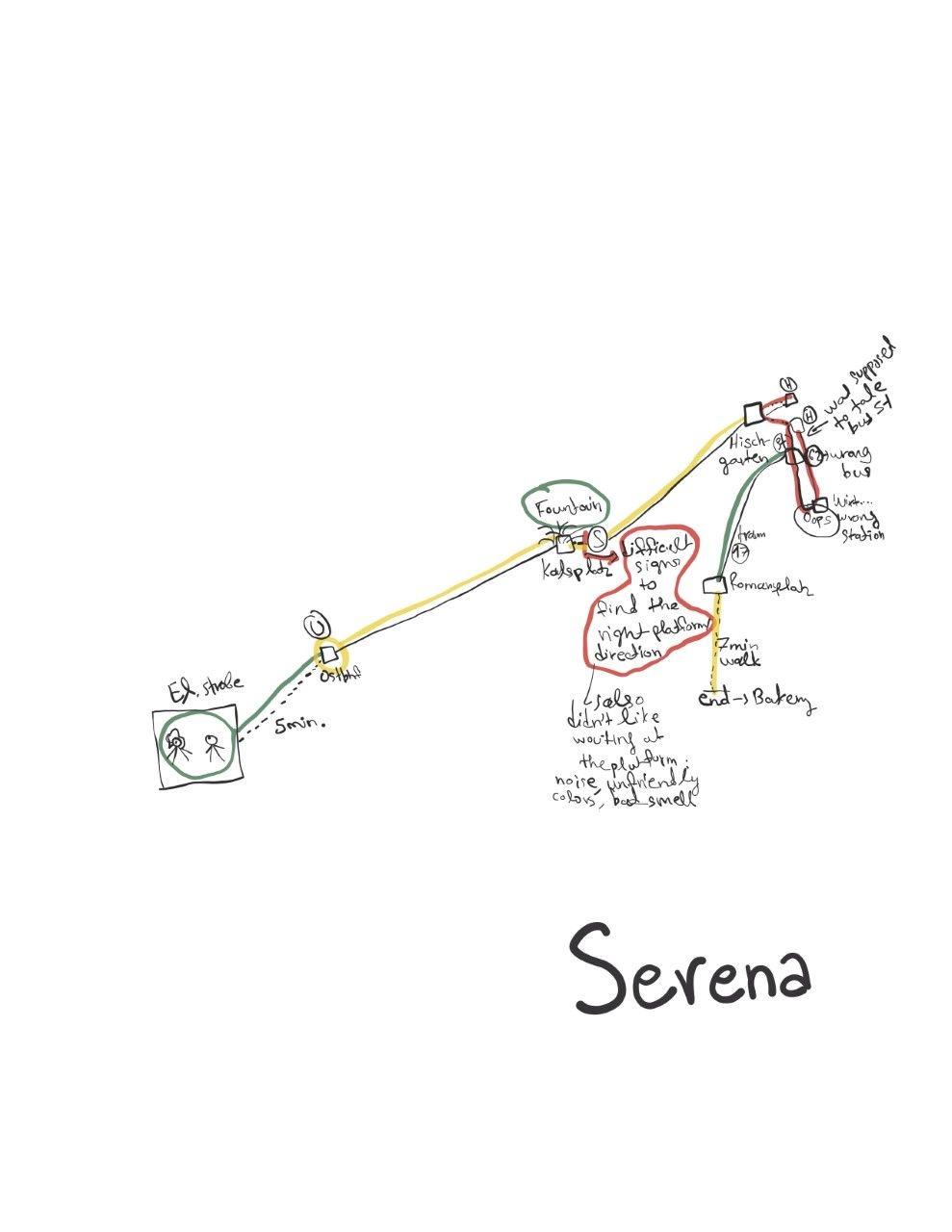

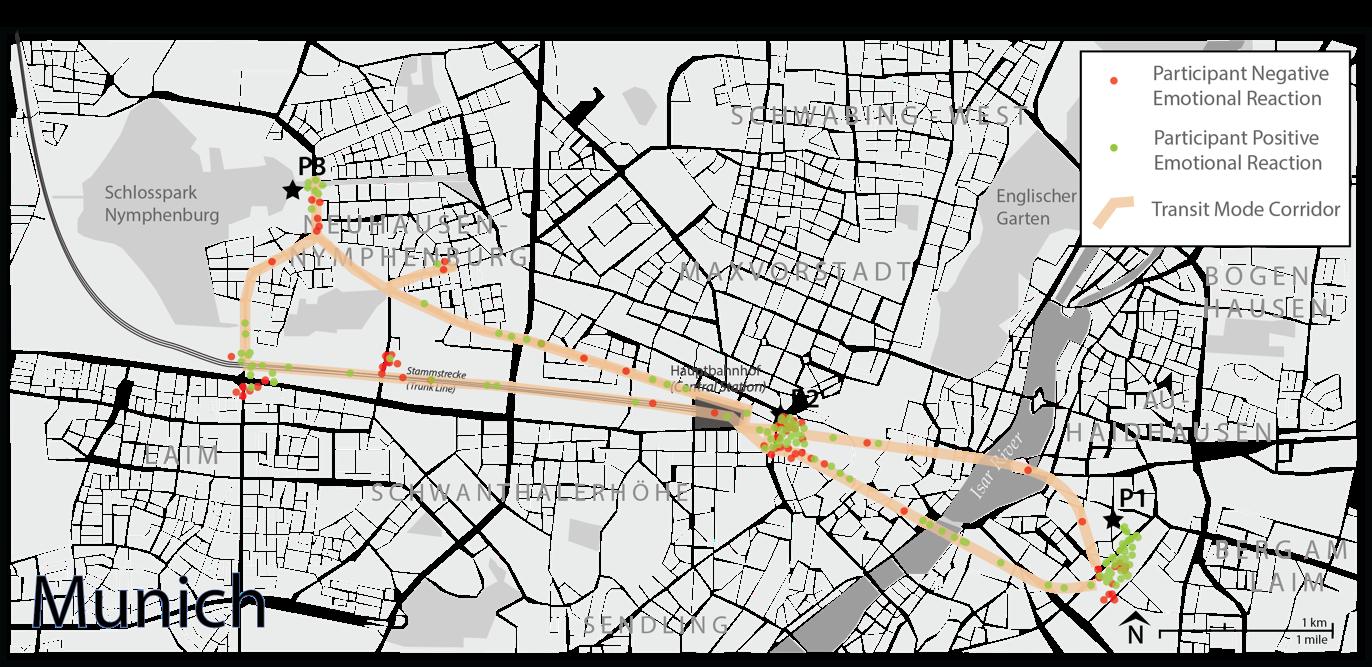

Part of my PhD research involved creating a method to study user behaviour in public transit. Documenting said behaviour on a map was key to visualizing the data. Multiple maps were created to visualise the varied elements of public transport and wayfinding within these environments. Icons were needed to depict specific transit modes.

The maps tell us how individuals navigated throughout the space and where they felt positive, neutral, or negative feelings. All of this data was then correlated and analysed. The findings are thoroughly discussed in my dissertation and can be found in the articles I published (also found at the end of this portfolio).

During my PhD I was a part of a research group called the mobil.LAB . For the mobil.LAB's final conference, I drew a portrait of each member of the doctoral research group. These drawings were used as the avatars for each of the speakers, and also as the profile photos on the conference website. Here are a select few of them

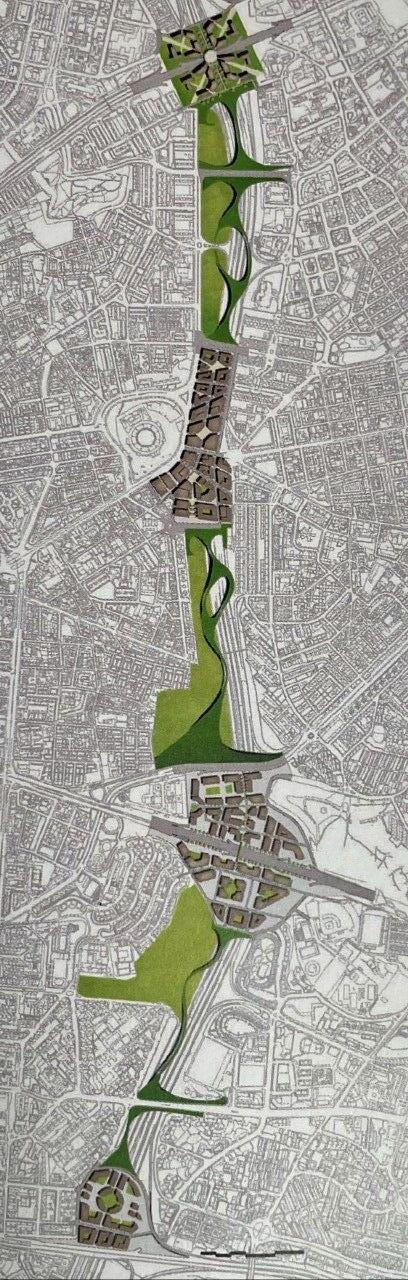

RIGHT: The partial cap of the M30 highway in Madrid was designed when I was a master's student at the University of New South Wales, as part of a design stay at Fundacion Metropoli (Alcobendas, Spain). Each cap encompasses a landmark structure within a precinct and connected by active transport paths. The design takes on an "artificial nature" approach - creating a functional open space system within the existing built environment..

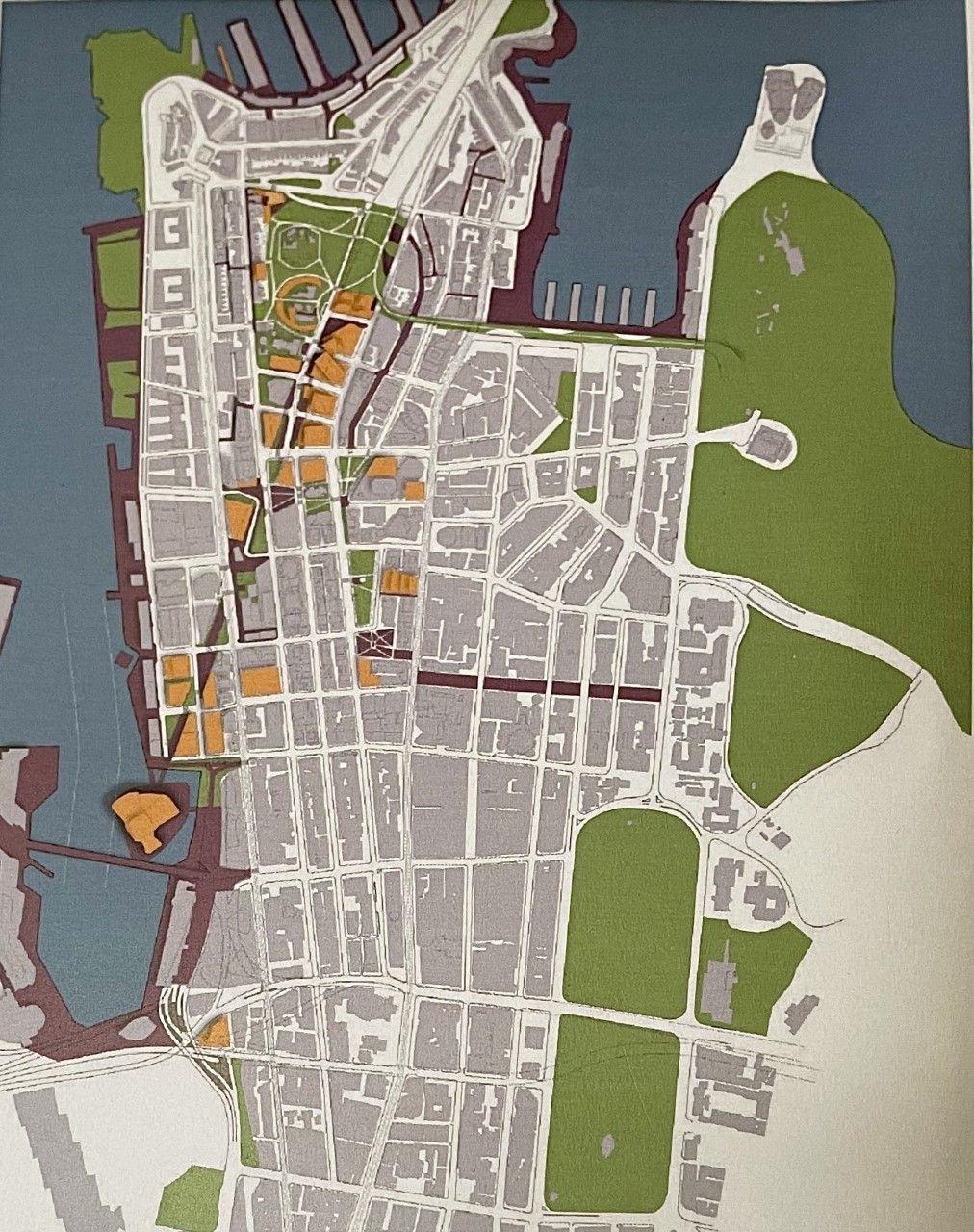

BELOW: Part of a design project during the Master of Urban Development and Design program at the University of New South Wales, I designed what Sydney could look like without an elevated highway running through the Central Business District and presupposes the highway is buried underground. The central axis remains to allow for a reknitting of the of the city grid by highlighting the connection between Darling Harbour and Circular Quay.

UPPER LEFT: I created this image for a friend of mine as a housewarming gift. I wanted to capture the loving playfulness of their relationship.

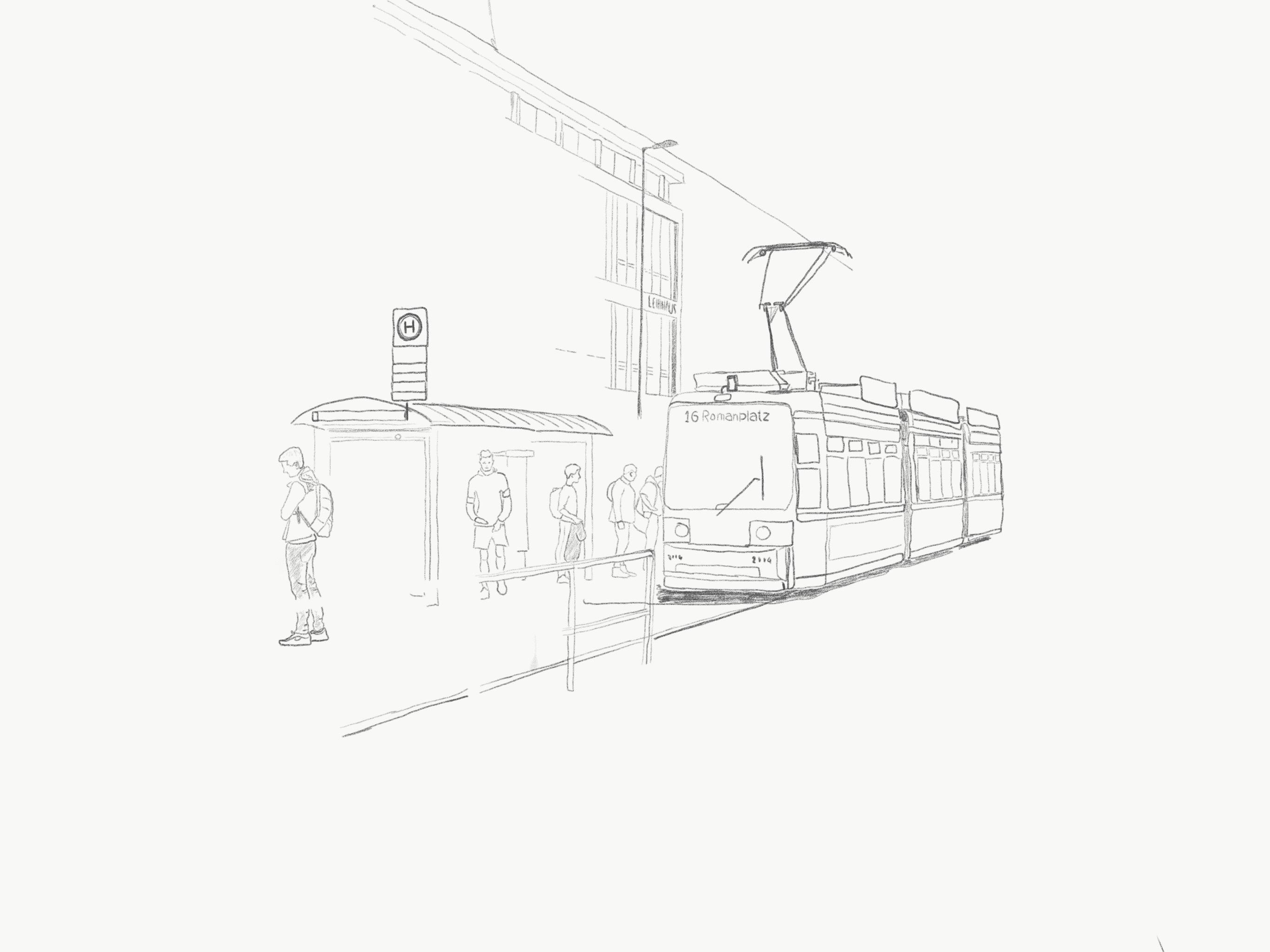

BOTTOM LEFT: Two images of the Munich transport system – one sketch of people waiting for a tram, the other a coloured drawing of the busy Hauptbahnhof (Central Station).

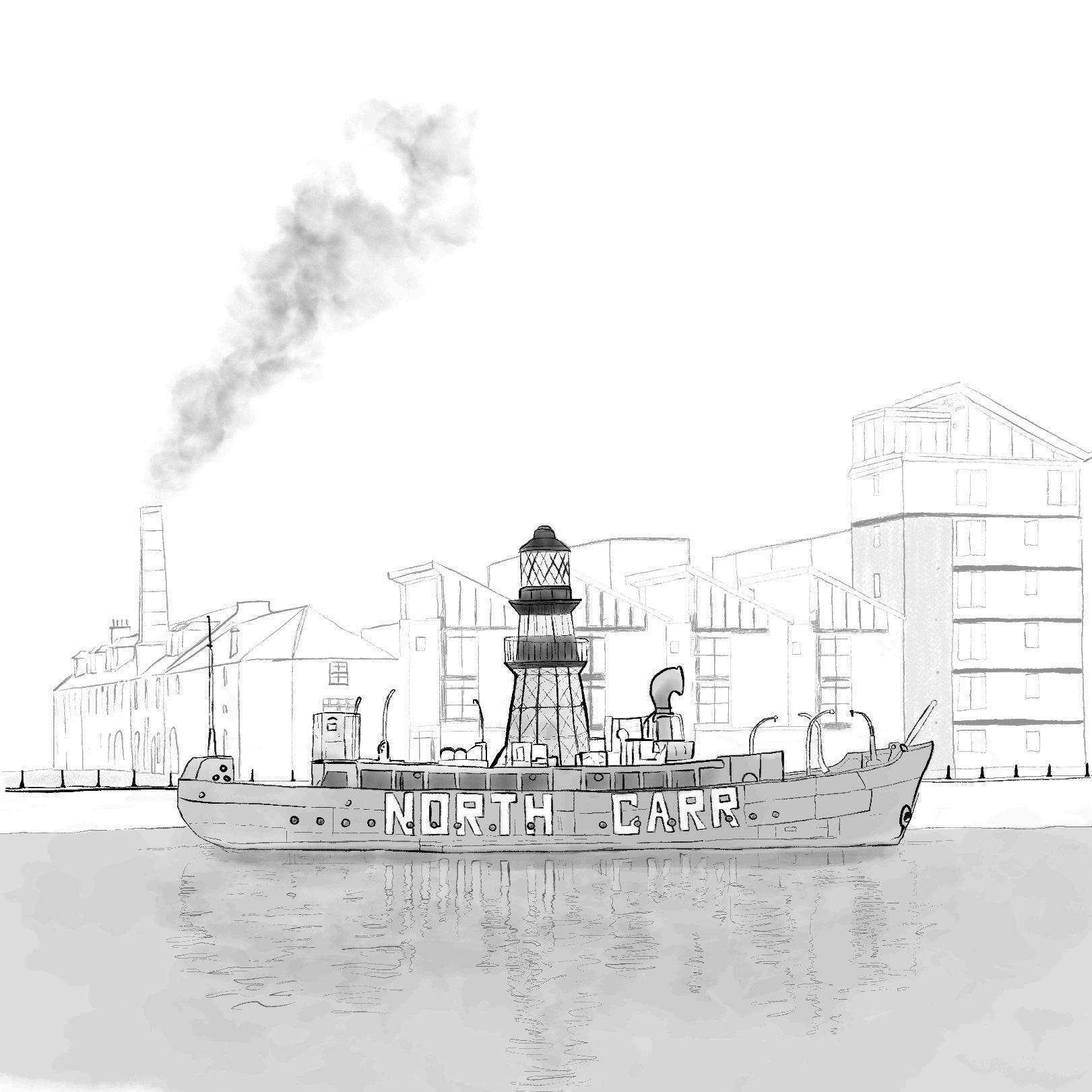

BELOW: A drawing of the North Carr boat in Dundee Harbour on a crisp winter day.

The next three pages in this portfolio include three separate articles I wrote for part of my PhD at the Technical University of Munich. These articles have been peer -reviewed, have been published, and are available open -access (for free) on their respective journal websites.

The articles form three chapters of the entire PhD dissertation and discuss user experience whilst navigating and using wayfinding devices in Munich’s public transport system. The articles touch on elements of emotional experiences in public transport as well as the use of both physical and digital infrastructures.

Anthony Ferri* Monika Popp Gebhard Wul orst

PhD Student

Chair of Urban Structure and Transport Planning

Department of Mobility Systems

Engineering, TUM School of Engineering and Design

Technical University of Munich

anthony.ferri@tum.de

*corresponding author

Department of Geography

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität

monika.popp@lmu.de

Professor and Chair

Urban Structure and Transport Planning

Department of Mobility Systems

Engineering, TUM School of Engineering and Design

Technical University of Munich

gebhard.wul orst@tum.de

The ubiquity of mobile and communication devices today is a result of a rapid societal adoption of new technology over the last few decades. Part of this acceptance of new technologies includes the success story of the smartphone and its advanced level of communication and geo-positioning capabilities on a higher resolution and interactive display (Boulos, et al., 2011; Fullwood, et al., 2017; Perrin, 2017; Melumad, et al., 2019). As smartphones gained popularity, so did the way they in ltrated the many aspects of everyday life — including the way we navigate, particularly focusing on helping us in environments that are unknown, by customizing way nding (Schwering, et al., 2017; Melumad & Pham, 2020). This customization can either aid a user, by presenting a concise route and clearly labeled connections, or hinder a user by producing contradictory information compared to their physical surroundings. For example, a smartphone provides a user with navigational options through applications, or apps. These apps are either third-party entities with their own strategic goals, or apps directly controlled by local transit authorities and not always able to capture all scheduling delays, nor provide all different transfer options to the user (Bian, et al., 2021). Quite often the information provided contradicts and/ or overlaps with other sources of information provided by other apps or websites, leading to fragmented and incoherent provision of navigation information. This, in turn, results in the user having con icting advice during their transit experience.

For a quickly growing portion of the population, the way nding process now incorporates the use of smartphones. In Germany, like many other Western nations, over the last decade, the smartphone has become more com-

Abstract /

Way nding in spatially complex public transit environments poses unique navigational challenges. Transfers, delays, barriers, and user capacity all inuence the usability of a system. Because of the smartphone, how we navigate through these systems, and interact with the surrounding environment is changing. e smartphone provides a spatio-temporal strategy that removes the reliance on our immediate environment and personalizes the waynding process — unlike that of transit schedules, signs, and maps. How does smartphone usage inuence performance and the way nding experience? is paper looks at smartphone usage of twelve participants through a shadowed commented walk, known as a Destination-Task Investigation, in Munich’s public transit system. e study provides insights into the role and the in uence of smartphones during the wayfinding process. Furthermore, it shows that apps providing integrated spatio-temporal information, such as Google, were used most frequently, especially for con rmation during navigation.

Keywords /

Smartphone Technologies; Public Transit; Way nding

Ferri, Popp, and Wul orst

Issue 23(1), 2023, pp. 63-84

https://doi.org/10.18757/ejtir.2023.23.1.6261

ISSN: 1567-7141

http://ejtir.tudelft.nl/

Anthony Ferri1

Chair for Urban Structure and Transport Planning, Technical University of Munich, Germany.

Monika Popp2

Department of Geography, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany.

Wayfinding in public transit environments is especially complex, combining both spatial and temporal tasks for user s to reach their destination. However, a gap exists between users’ needs and existing infrastructure design. With the introduction of Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) to the broader public, the wayfinding process has shifted from more traditional methods to more digital approaches, leaving individuals with the task of navigating the space between both physical and digital milieus. Th e exploratory study presented in this paper provides insights into physical and digital navigational practices in public transit wayfinding systems. The method employed was that of a Destination-Task Investigation, a qualitative mobile interviewing method used to capture participants’ feelings, thoughts, and experiences. The study focuses on three transit spaces within the network: (a) aboveground transfer stations, (b) belowground transfer stations, and (c) on transit, and reveals that participants often relied on their smartphones instead the physical wayfinding infrastructure Moreover, participants were found to use their smartphones in three navigational approaches: (1) Directional Confirmation, (2) Current Positioning, and (3) Future Planning. Results show that participants preferred the Directional Confirmation approach in both aboveground and belowground transfer stations and used their smartphones for navigational purposes most often while on transit. The study also helps illuminate that the presence of a robust wayfinding system within a public transit system increases user trust in the overall system. This study contributes to better understanding user behavioural patterns which has significant relevance for researchers as well as practitioners.

Keywords: design for behaviour change, information and communication technology, public transport, smartphone, wayfinding

Publishing history

Submitted: 19 January 2022

Accepted: 20 February 2023

Published: 27 March 2023

Cite as

Ferri, A., & Popp, M. (2023).

Mind the gap: navigating the space between digital and physical wayfinding in public transit. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 23(1), 63-84.

© 2023 Anthony Ferri, Monika Popp

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

1 A: Chair of Urban Structure and Transport Planning, Department of Mobility Systems Engineering, Technical University of Munich, Arcisstraẞe 21, 80808 Munich, Germany E: anthony.ferri@tum.de

2 A: Department of Geography, Lugwig -Maximilians-Universität, Luisenstraẞe 37, 80333, Munich, Germany. E: monika.popp@lum.de

Anthony Ferri a, * , 1 , Monika Popp b

a Department of Mobility Systems Engineering, TUM School of Engineering and Design, Technical University of Munich (TUM), mobil.L Doctoral esearch roup, hair of Urban Structure and Transport lanning, Munich, ermany

b Department of eography, Lud ig Ma imillians Universitat (LMU), Munich, ermany

ey ords

Cognitive maps

Emotional design

Multimethod

Transit behavior

Wayfnding

1. Introduction

When we think about public transit, seldom do we consider the infuence the space has on our emotional wellbeing. We often consider these spaces as a means to get from Point A to Point B; however, they also function as places of social interaction, and immediately upon entering them, we are required to rely on our senses and feelings to make navigational decisions. Moreover, transit spaces can be incredibly intimidating and overwhelming for many individuals, leading to a high anxiety and stressful experience which affects one’s overall emotional wellbeing (Balaban et al., 2017; Chang, 2013; Cox et al., 2006; Haake et al., 198 ; Natapov et al., 201 ; Peponis et al., 1998; Stankiewic and alia, 2007). Emotional wellbeing, as defned by Huppert (2009), emphasi es the positive feelings experienced in one’s daily activities and describes feeling good (primarily encompassing positive emotions such as happiness, engagement, contentment, and confdence), and functioning effectively (involving the developing of one’s potential, having control over one’s life, coping with normal daily stress, and working towards a goal), as the basis of the term. While both researchers and

* Corresponding author.

1 Present address: Chair of Urban Structure and Transport Planning, Technical University of Munich, Arcisstrasse 21, Munich 80333, ermany. Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com/journal/wellbeing-space-and-society https: doi.org 10.1016

Users of public transit tend to avoid certain routes because they dislike particular aspects, or gravitate towards a particular mode because it is familiar, or because it “feels right” This type of navigation can be described as ‘ ayfeeling’ , or letting one’s senses guide the way. The concept of ayfeeling is integral to understanding how public transit space is used, and underscores the importance of emotional wellbeing within these spaces. But how does one determine what wayfeeling is and when it is being performed? The aim of this paper is to illuminate how emotional wellbeing affects navigational behaviors through the act of wayfeeling. The study uses participant experiences of a Destination-Task Investigation (DTI) in Munich’s public transit system. Included in the DTI, participants were asked to draw their navigational journey, and then asked to highlight the sections they found positive, neutral, and negative. The study revealed that the act of navigating a transit space evokes strong emotional reactions from participants, especially as they had more negative experiences in transfer areas, and felt more positive in familiar spaces. Most importantly, negative events during the DTI overshadowed the overall perception of their journey which lead to an overall negative opinion of their experience.

practitioners have paid close attention to transit environment and infrastructure design (Adey 2008; ensen, 201 ; ensen and Lanng, 2016; Merriman and Pearce, 2017), and research has begun to hone in on the effects of positive experiences in individual memory (Baumeister et al., 2001; Bebbington et al., 2017; Carstensen and DeLiema, 2018), transit users’ emotional wellbeing within these two contexts have not been at the forefront.

In order to help with decision making processes, especially in critical and stressful situations, we rely on our surroundings for navigational cues (Chang, 2013; Haake et al., 198 ). In parallel, we internally sense the situation resulting in an emotional outcome and response. In light of this, wayfnding networks have become essential elements in public transit systems by providing spatio-temporal guidance for passengers through design techniques that include light, color, sound, and texture (Fendley, 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Scollon and Scollon, 2003; van der Hoeven and van Nes, 201 ). The intention of the wayfnding system is to provide navigational assistance to maintain positive user experience. While practitioners have good intentions when implementing wayfnding systems within transit networks, there are aspects of the

E mail addresses anthony.ferri tum.de (A. Ferri), monika.popp lmu.de (M. Popp).

Photo by Anthony Ferri

Photo by Anthony Ferri