by Brett Ruffell

by Brett Ruffell

We know the ink has barely dried on this year’s Who’s Who edition – our previous issue where we profiled r ising poultry stars from across the country. However, we’re already planning ahead for next year. And we once again want your input.

The theme for 2019’s Who’s Who is diversity. We’re searching across the country and in different parts of the poultry industry for people who have an interesting and broad mix of focuses.

It could be a farmer growing a combination of different crops and livestock in addition to poultry. Maybe it’s a v et with a varied range of clientele and responsibilities. Or perhaps it’s a researcher studying multiple aspects of poultry – from health and welfare to bird management and more.

Whatever the case may be, if you know of someone who fits the diversity bill we want to hear about them. Visit www.canadianpoultrymag. com/whoswho to send us next year’s nominees. They could end up being featured in next summer’s special edition.

After working on this current issue’s cover story, it wouldn’t surprise me if one of next year’s nominees were part of Chicken Farmers of Ontario (CFO)’s Artisanal Chicken Program. In its third

year, the first of its kind initiative allows growers to produce between 600 and 3,000 birds without buying quota.

The program has proven to be a natural fit for producers with mixed farming operations looking to further diversify their income in a cautious but meaningful way. Al D am, poultry specialist Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, F ood and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), met a few such producers during a recent tour of northern Ontario.

One artisanal chicken grower he met had a market garden, hogs, turkeys and an on-farm market store. Now,

“In the north, there’s been a lot of interest in the whole locally raised food movement.”

through CFO’s program they’ve gradually scaled up to 3,000 chickens as well. “They’ve done really well,” Dam observes.

It was the second year in a row that OMAFRA teamed up with CFO to visit the region. Their goal was to encourage people to participate in the board’s Community Programs, which the artisanal ch icken initiative is an important part of.

Joining Dam for the ride was Carl Stevenson, who advises

producers participating in CFO’s Community Programs, and Dr. Scott Gillingham, a vet and Canadian regional business manager with Aviagen.

At night they delivered workshops in Spring Bay, Sowerby, Azilda and Powassan for anyone interested in chick en production of any scale. Gillingham’s talk covered brooding while Dam spok e about what people could produce without quota, nutrition issues, feeding challenges and more.

During the day they visited white meat processing plants and producers enlisted in CFO’s Community Programs. They listened to growers discuss local challenges. For instance, predators like bears are a big issue. The trio also learned that the artisanal program was having a strong impact in the region.

Why? It’s largely being driven by consumer demand.

“In the north, there’s been a lot of interest in the whole locally raised food movement,” Dam says. However, before the artisanal program there were no core chicken producers in northern Ontario. Now, thanks to the CFO program there are dozens of licenced small-scale gr owers. And the program continues to grow.

With September being National Chicken Month, it seemed fitting to mark the occasion by telling this success story. Get the full account on page 20. And enjoy the month-long celebration of chicken and chicken farmers ahead!

canadianpoultrymag.com

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Associate Editor Jennifer Paige jpaige@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-305-4840

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231 Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Coordinator

Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Alison Keba

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-442-5600 ext 3596

VP Production/Group Publisher

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

President/CEO

Mike Fredericks

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.00 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $69.00 USD Foreign – 1 Year $78.00 USD GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2018 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Customers struggling to get weights on their birds made Broiler Nipple Drinkers and immediately realized the difference it made on their OptiGROW

Colleagues, friends and dignitaries recently gathered in Guelph, Ont., at Alltech’s Canadian headquarters to celebrate the global animal nutrition company’s 30th anniversary operating in Canada. Founded in 1988 by Dr. Pearse Lyons, Alltech Canada has offices and representatives strategically located across the country. In 2016, Alltech acquired Masterfeeds and added a strong network of farm-focused dealers to accommodate and service farmers and ranchers nationwide.

In the early 1940s, a group of Alberta farmers join together to create a co-operative. At first, the co-operative focused on eggs, until 1941 when the group acquired a processing plant and became known as Alberta Poultry Producers Limited. Over the years, the Alberta Poultry Producers Limited business grows and the organization expanded its production capabilities in Alberta, B.C. and Saskatchewan. The name Lilydale first appeared in 1976 when the group becomes known as Lilydale Co-operative Limited. In 2005, the company renamed itself to Lilydale Inc. and in 2012 was acquired by Sofina Foods Inc. This year, Lilydale, one of Canada’s leading poultry brands, celebrates 75 years in business.

Lawrence MacAulay, minister of agriculture and agri-food, recently announced the Government of Canada was providing $844,000 to Egg Farmers of Ontario to assist in the development of Hypereye, an electronic scan to determine the gender and fertility of eggs.

4.4%

is the amount domestic broiler hatching egg production in Canada increased in 2017, over 2016

will identify both the gender and fertility of about 50,000 day-old eggs per hour once fully operational at the commercial hatchery scale.

Maple Lodge Farms (MLF) recently announced an $8 million expansion to its hatchery in Port Hope, Ont.

The investment will extend the hatchery by 22,825 square feet for a total of 56,000 square feet and include state-of-the-art incubation equipment.

“ We are committed to the province’s chicken farmers and the Ontario hatching egg and poultry industry,” said Michael Burrows, CEO of Maple Lodge Farms. “We are investing in the industry, our employees and the Port Hope community. The world-class technology that we are bringing in will make this an exemplary hatchery in the province and country.”

The expansion will include state-of-the-art incubation equipment provided by

Jamesway, a long-time supplier for Maple Lodge hatcheries. The project will feature 36 Platinum 2.0 incubators and 20 Platinum 2.0 hatchers.

When complete, the MLF hatchery will double its capacity to 48 million chicks annually, to better serve southern Ontario farmers and the Ontario poultry industry. The expanded operations will offer new job opportunities for the Port Hope community.

The Port Hope hatchery is led by veterinarian and general manager, Dr. Rachel Ouckama, who has been with the company for 33 years. She was instrumental in developing the expansion proposal and will oversee the project to ensure that a high operational standard is maintained.

Kari Tosczak was born and raised on a grain and cattle farm south of Weyburn, in the southeast corner of Saskatchewan. She attended the University of Saskatchewan and obtained a degree in animal science. After a few years in the swine and goat industries, Tosczak shifted her focus to poultry, working in the feed industry. In 2016, she took on the role of executive director with Chicken Farmers of Saskatchewan.

What do you do with the Chicken Farmers of Saskatchewan?

I am involved in the provincial allocation and pricing, board governance, strategic direction and budgeting. Saskatchewan also has a fund that we do research and industry promotions with, so a good chunk of time is spent with our research committee, guiding that program. Communicating with all the moving pieces of the industry is also a big part of my job – our staff, other provinces, other sectors within our province, the government, and, of course, working with producers. We also implement the Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) On-Farm Food Safety Program and On-Farm Welfare Program at the provincial level.

What do you enjoy most about this position?

I really enjoy being able to work alongside producers and be a voice for them and try to make sure the communication coming to them from CFC, the government and consumers is clear. It is important that everyone understands the reasons behind changes that are being made.

What are some of the initiatives currently being worked on? We completed a quota expansion last year and are also working on establishing a new entrant program to allow new farmers to get started here in the province. We are hoping to get this rolling sometime this year. We also understand the importance of the of antimicrobial reduction and what that will mean to our farmers. Through our research funding we are working to ensure the tools that our farmers need will be available.

What are the challenges/ opportunities you see for Saskatchewan chicken farmers?

Saskatchewan does have some RWA (Raised without antibiotics) production here in the province, which is something some consumers are looking for and we are filling that successfully. In terms of challenges, we have a lack of processing so a lot of our primary product goes out of province.

How do you hope to contribute to the industry?

I think for me, I have a connection with the farms here in Saskatchewan, and I approach things with a “what does this mean to farmers” attitude. Some of our programs require on-farm changes, and so it is important to me to make sure that that these changes don’t negatively impact the welfare of the birds or the farmers. I would like to work to minimize any impact from industry changes, help the farmers to maximize their bird welfare, while we meet the needs of consumers.

SEPTEMBER 2018

SEPT. 1

National Chicken Month Canada-wide

SEPT. 5

PIC Golf Tournament Baden, Ont.

SEPT. 9 - 13

IEC Global Leadership Conference Kyoto, Japan

SEPT. 11 - 13

Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show Woodstock, Ont.

SEPT. 17 - 19

VIV China 2018 Nanjing, China

SEPT. 24

PIC Science in the Pub Guelph, Ont.

OCTOBER 2018

OCT. 12

World Egg Day Worldwide

Stay informed on infectious disease outbreaks with the latest alerts from Canadian Poultry magazine. For more, visit: canadianpoultrymag.

JULY 29

Marek’s Disease Clark County, Ohio

JULY 23

Avian Influenza Denmark

JULY 14

ILT: Advisory Lifted Niagara, Ont.

A panel of farm animal care specialists examining undercover video reportedly obtained from an egg farm in B.C. says some of the conditions seen are unacceptable but cautions against moving to quick judgement. “We can’t make an assessment from this other than to say this video is not what we see on a daily basis working on farms,” said Dr. Tom Inglis, a practising poultry veterinarian and adjunct assistant professor at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary.

“Our hope would be that if this video clip is shown as news that it is followed up with sufficient confirmation of validity and an attempt to confirm that the facility and situations depicted actually occurred, were not staged, and were responsibly reported to ensure that birds did not suffer or continue to suffer.”

The panel of experts reviewed the video as part of the Animal Care Review Panel program established by the CCFI. The panel was comprised of Dr. Inglis, in collaboration with: Dr. Benjamin Schlegel, a board-certified poultry veterinarian; Jennifer Woods, animal welfare specialist;

and Dr. Mike Petrik, a practising poultry veterinarian.

The group examined a 2.5-minute video apparently produced by the group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). “All egg farmers in Canada are expected to follow the standards set forth in the Canadian Codes of Practice for Laying Hens,” said Woods. “If producers are found to not be adhering to the standards, I would expect industry to intervene and work on correctional actions along with providing further education to the producer.”

CCFI established the Animal Care Review Panel program to engage recognized animal care specialists to examine hidden camera video investigations and provide expert perspectives. It operates independently. Its reviews, assessments, recommendations and reports are not submitted to the egg industry for review or approval. CCFI’s only role is to facilitate the review process and release the findings. The panel’s full report is available at www.foodintegrity.ca/programs/ engage.

Olymel L.P. executives announced the acquisition of all the shares of Pinty’s Delicious Foods Inc., an Ontario poultry slaughtering and processing company that specializes in fully cooked products and other related products. Headquartered in Burlington, Ont., Pinty’s employs 360 people. The company operates three processing plants, respectively located in Port Colborne, Paris and Oakville, Ont.

Tom Inglis, a practising poultry vet and professor, was part of a panel of experts that examined the undercover video.

Alberta Farm Animal Care (AFAC) is involved in a new initiative called the Livestock Welfare Engagement Project. The goal of this project is a collaborative look at animal welfare in Alberta’s livestock industry, where AFAC will facilitate the collection of input from individuals and organizations across the sector. AFAC is looking for help from anyone in Alberta who is involved in animal agriculture. The Livestock Welfare Engagement Project survey is available at surveymonkey. com/r/8HFBYW2

Maple Leaf Foods recently announced that it has signed a definitive agreement to acquire two poultry plants and associated supply from Cericola Farms, a privately held company. Located in Bradford, Ont., and Drummondville, Que., collectively the two plants process approximately 32 million kg of chicken annually.

Have a poultry health question? Send it to poultry@annexweb.com and one of our Ask the Vet columnists will be happy to answer it!

By Aline Porrior

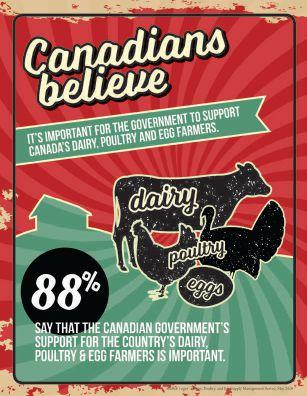

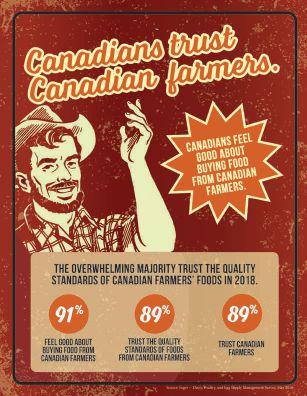

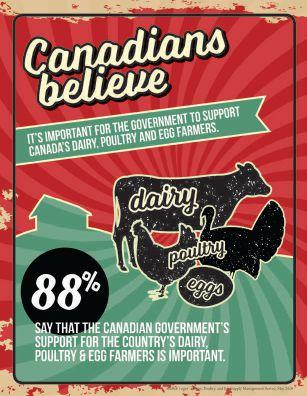

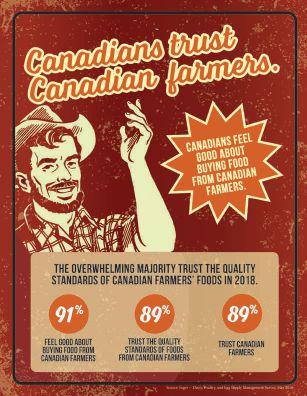

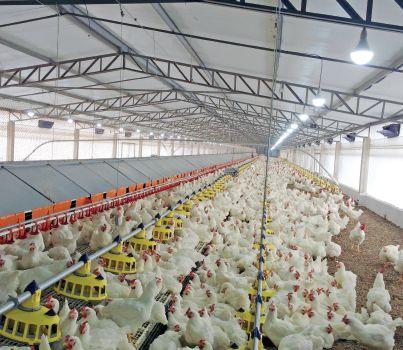

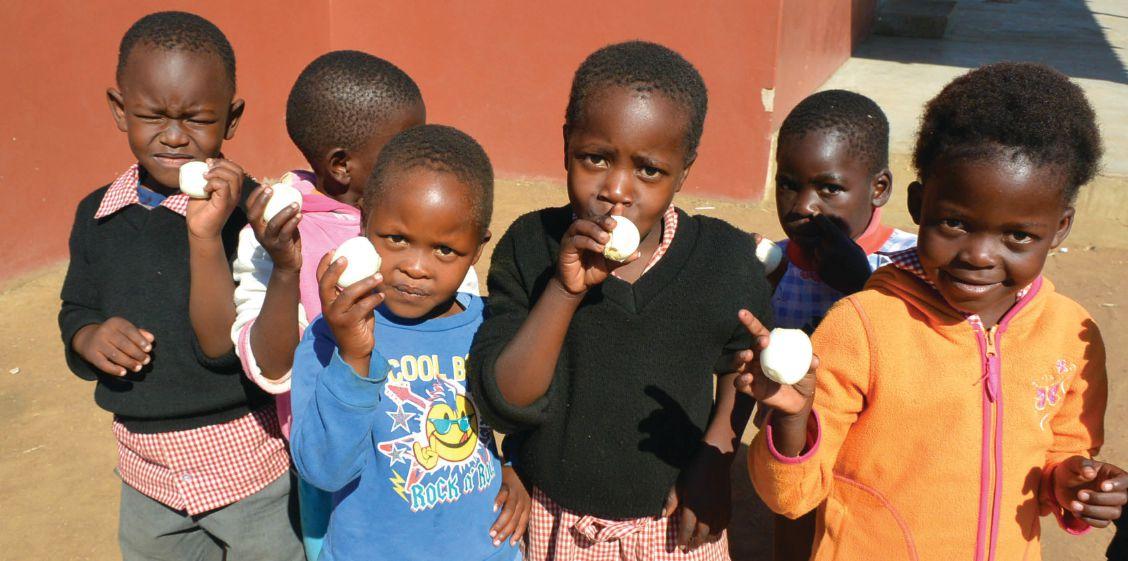

Did you know that September is National Chicken Month? Each y ear, Chicken Farmers of Canada has celebrated chicken farming throughout the whole month of September and this year we are as excited as ever.

It is a time to celebrate chicken farmers from coast-to-coast – they work hard to provide Canadians with fresh, high-quality chicken on a daily basis. Not only that, but we celebrate the benefits chicken farming brings to Canada, whether it’s economic contributions, a safe and steady food supply or even how nutritious and delicious chicken is.

National Chicken Month is also a time to talk about the care our farmers take when it comes to raising their birds.

Our farmers all follow the mandatory Raised by a Canadian Farmer programs – they set out regulations and guidelines for the care and handling of the birds our farmers raise. Each program has strict guidelines that are audited on a regular basis.

The Raised by a Canadian Farmer logo provides additional assurance that the chicken Canadians buy is safe, fresh, of high quality and was raised by caring hands.

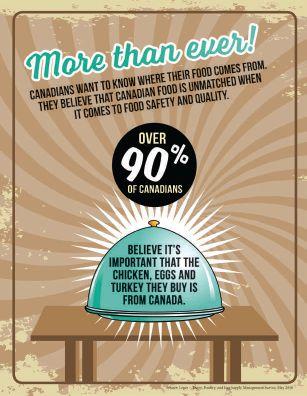

As the years go by, we’ve noticed a disconnect between consumers and their knowledge of where their food comes from. In fact, 84 per cent of Canadians purchase fresh chicken, yet most of them do not understand how the chicken gets to their local retailer.

This is why National Chicken Month is so important; it

National Chicken Month is also a time to talk about the care our farmers take when it comes to raising their birds.

gives us the platform to tell the story behind Canadian chicken farming, and debunk myths surrounding our industry. For example, 43 per cent o f Canadian consumers believe that chickens are raised without hormones or steroids, when in fact hormones and steroids have not been used in Canadian chicken production for more than 50 years. By continuing to deliver our messages through fun activities and contests, we are able to reach Canadian consumers and help them understand how their chicken went from gate to plate.

So, what do we do to celebrate these hardworking farmers? Chicken Farmers of Canada is proud to put on and

pr omote various activities throughout the month in order to get people talking about ever ything chicken. In past years, we have had activities such as a Twitter Party, a N ational Recipe Contest, a Farmer Selfie contest, and even a Pool Peeps colouring contest – which brings everyone together.

Our farmers’ personal favourite is our annual Cook Off videos called Chef D’Oeuvres, which is created in partnership with Swimming Canada. T his head-to-head cooking competition takes farmers out of the barn and into the kitchen to compete against National Canadian swimmers. This year we have farmers Catherine and Tatyana Keet go up against Olympians Martha McCabe and Savannah King as well as farmer b rothers Félix and Anthony Morin battling Olympian Charles Francis and Paralympian Camille Bérubé. These fun videos will be posted throughout the month, with Canadians voting on social media as to which recipe reigns supreme. Missed any of the previous videos? Make sure to check out our YouTube channel to see them all.

How can you take part in this year’s National Chicken Month?

Simple – head over to our website chickenfarmers.ca to see what we have in store. Make sure to follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for prize and loads of fun. We promise you this year’s National Chicken Month will be the best one yet!

The Canadian Poultry Research Council, its board of directors and member organizations support and enhance Canada’s poultry sector through research and related activities. For more details, call 613-566-5916, email info@cp-rc.ca or visit www.cp-rc.ca.

During the course of the past six decades, the poultr y industry has achieved a remarkable increase in production efficiency, largely driven through intensive breeding programs. However, this is in part at the expense of a decrease in reproductive performance and altered immune function. Consequently, a major challenge for the poultry industry is in controlling disease outbreaks caused by infectious agents.

Growth promoting antibiotics (GPAs) refer to the sub -therapeutic quantities of antibiotics, such as virginiamycin and bacitracin, that are added to livestock feed to enhance production efficiency. W hile the precise mode of action of GPAs has yet to be elucidated, they are thought to act through altering the microbial community (microbiome) in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, reducing levels of pathogens causing acute enteric infections. Removal of GPAs from Canadian livestock feeds is promoting interest in the identification of efficacious alternatives.

H undreds of species of microorganisms reside within the GI tract of chickens, which confer a mutually beneficial relationship. A major contribution of these microorganisms is their ability to extract key nutrients in addition to limiting colonization by pathogenic species. Such benefits may be particularly significant for

birds with compromised immune systems and, thus, there is much interest in identifying approaches to manipulate and maintain a healthy microbiome. While recent studies have demonstrated the potential of probiotics to reduce pathogen burden in the GI tract, it is not clear how they work or which formulations are most efficacious.

Dr. John Parkinson, from the University of Toronto, and his research team aim to systematically study the precise mechanism thr ough which probiotics operate by elucidation of active biochemical pathways. In addition, they aim to identify which probiotic species (or combination of species) pr ovide the most beneficial effects.

They will rely on next generation sequencing to both understand the dynamics of microbial populations in the

chicken GI tract as well as identify microbial and host factors that minimize pathogen burden.

The overall strategy is to examine how the microbiome of specific locations of the chicken GI tract respond to dietary regimes over the lifetime of broiler birds, and how such changes impact the abundance of major enteric pathogens, Eimeria and Clostridium perfringens.

To ensure that these findings may be translated across poultr y lines, the researchers are also interested in examining the role of genetics on p athogen burden and how modern breeding practices may have compromised host immune pathways and the host’s ability to reduce pathogen burden.

In the first phase of experimentation, commercial diets in the presence and absence of GPA on commensal abundance and pathogen burden will be investigated. In the second

phase, commercial diets will be supplemented with varying probiotic formulations. In the final phase, commercial diets supplemented with the three best performing formulations will be applied.

The first phase of the experiments have been completed and results are currently being analyzed. Preliminary findings suggest that significant changes occur in the gut microbiome over intestinal sites and bird ages, but the diet and the use of antibiotics had a modest effect. The second phase is currently underway and results will lead to the initiation of phase three.

Anticipated outcomes of this research will provide validation of defined probiotic formulations that minimize the colonization of the chicken GI tract by Eimeria and C. perfringens, in addition to a systematic framework for microbiome interventions that could be readily applied in the short term to the egg laying industry. Findings will ultimately assist in the elimination of GPAs from the poultry su pply chain whilst maintaining consumer confidence in the safe consumption of poultry meat.

This research is funded by the Canadian Poultry Research Council (CPRC), ALMA, NSERC Discovery, Lallemand Animal Nutrition, Pitblado Chair, Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, University of Alberta, New Life Mills and Aviagen.

By Lilian Schaer

The poultry industry is harnessing the skills of University of Guelph computer scientists and their artificial intelligence expertise to get a better idea of when and where avian influenza might next emerge.

Professor Rozita Dara and her computational sciences PhD student Samira Yousefi are mining social media for clues that could help establish correlation between what is talked about by Twitter users and what is reported through actual surveillance and diagnostic activities by the World Health Organization, the World Organization for Animal Health and others.

The ultimate goal is to help authorities with disease prevention and response and policy making, and while online surveillance has been used for human influenza, less work has been done on the avian form of the disease.

“The earlier we detect (an

outbreak), the better and more precise our actions can be,” Yousefi explains, adding this could help avoid tools like mass vaccination or mass culling that are currently widely used disease response measures.

Using a list of keywords related to avian influenza generated by the researchers, an automatic sy stem crawler searches Twitter continuously 24 hours a day for a whole year to gather information and populate a database.

Non-avian influenza and spam posts have to be filtered out using an artificial intelligence algorithm and the system is intelligent enough to learn which data was relevant as it goes along. Now the research team has a clean data s et that shows how many tweets each day were posted about avian influenza.

“This system is hugely robust and can gather a lot of information without human engagement in the process,”

“The earlier we detect (an outbreak), the better and more precise our actions can be.”

Yousefi says, adding the system will improve as the machine becomes smarter.

“ There are so many features that in the future we could customize to language, geographical areas or countries.”

The team did find a surge in Twitter activity around confirmed outbreaks, proving that it is possible to use Twitter data in a predictive fashion.

Avian influenza is a reportable disease, meaning farmers have to let authorities know if they find it on their farm, but many other diseases have no reporting obligation.

“If farmers share data or information on Twitter for diseases that aren’t reportable, like reovirus or infectious bronchitis, we can use this technology to identify disease emergence,” explains patho -

biology department chair and poultry researcher professor Shayan Sharif, a project collaborator who is providing poultr y disease expertise to Dara and her team.

Yousefi’s work also involves developing models that allow for simulation of disease spread between farms based on bird movements to establish regionalized degrees of risk. T his will help policy makers decide what type of control or preventative action should be taken.

The ultimate goal, according to Sharif, is to pull all the p ieces together into a decision support system empowered by artificial intelligence that is able to integrate the different layers of data for early detection and early intervention of avian influenza. Social media is one data source, but so are migratory patterns of birds, trade relationships and weather impacts.

“Right now we don’t have a good handle on how to precisely control and get rid of the disease and mass response is the best we can do,” he says.

This research, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Zvonimir Poljak of the department of population medicine, is supported by Food from Thought, Egg Farmers of Canada, Chicken Farmers of Saskatchewan, Canadian Poultry Research Council and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs – University of Guelph partnership.

This article is provided by Livestock Research Innovation Corporation as part of LRIC’s ongoing efforts to report on Canadian livestock research developments and outcomes.

By Ashley Bruner

Sometimes trends are not worth the hype.

I’m sure we all have at least one picture lying around with an outfit we thought was classic but is now horribly outdated. In today’s age of ever-evolving food trends, from cronuts to charcoal ice cream, it can be hard to know what trends are fleeting and which ones will stand the test of time.

At the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity (CCFI) we have been studying one of today’s most trendy segments in research – millennials.

Millennials are more than a catchy term for Generation Y or 18 to 34-year olds. They are a group with growing influence on the Canadian food system. According to Statistics Canada, millennials now represent the largest generation in the workforce and will continue to increase as older generations retire.

This means that millennials will increasingly be the decision makers and hold key positions throughout the agri-food chain.

Not only will millennials be the dominate demographic in the workforce, but the marketplace as well. Millennials will be the largest demographic buying weekly groceries, going to restaurants and making food-related decisions for their growing families over the next 30 years. Thus, what they think about the food system matters.

CCFI’s 2017 Public Trust research revealed that food issues are front of mind among millennials. The rising cost of food and keeping healthy food affordable are their top two life issues, followed by their financial situation, climate change,

and rising energy costs.

Despite citing food issues among their top concerns, the age group is not actively engaging on key food system topics like food safety, humane treatment of animals and innovative approaches to growing food. In fact, over four in 10 say they only think about these topics if they are in the media or they’re forced to.

Who do millennials think should be providing information on the food they eat since they themselves are not actively seeking it out? Our research shows that nearly twothirds feel Canada’s farmers should be providing this type of information, so it’s time for our farmers to answer this call to action.

Young farmers are well positioned to speak to their peers on this issue.

Our research provides some insights on how best to talk to them, star ting with where to have these conversations in the first place.

The best place to engage with millennials is online – the top source of information on food system issues for this group.

A perceived lack of transparency and information is commonly cited by millennials with moderate-to-low trust ratings (rating of four-to-seven out of 10) for Canadian farmers, the way they grow our food and the information they provide. To address this concern, outreach must be loud, clear and credible.

Two areas this generation feels farmers are most responsible for providing transparent information on is the impact of food production on the environment and the treatment of animals raised for food, followed by food safety and

Ashley Bruner is research co-ordinator with the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity. For Canadian consumer insights on public trust in food and farming, visit foodintegrity.ca.

business ethics in food production. When engaging, farmers should address these issues directly. This needs to be authentic – which includes admitting areas where improvement is needed or problems exist.

The importance of building trust in our food system will outlast any trendy diet or food craze in the long term. Millennials care about food issues but are not proactively engaged with them. This means you must get their attention first, then turn up the volume for sharing clear and credible information on food. Young farmers can definitely lead the charge connecting with their peers through their social media channels and putting themselves outside their normal circle of others in the industr y.

Download the CCFI Public Trust Research reports or listen to a webinar about millennials and trust in the food system at foodintegrity.ca. Also, join us at the CCFI Public Trust Summit in Gatineau, Que., on November 13-14 as we turn these research insights into actions.

Ashley Bruner recently joined CCFI as a research co-ordinator and is excited to bring her market research and public policy experience to the team. For the past six y ears, she has worked at Ipsos Public Affairs, managing hundreds of research projects with diverse methodologies for a variety of clients in the public, private and non-pr ofit sectors. She is now converting CCFI research findings into actionable insights to help the food system earn trust.

What makes food news and information credible to consumers?

When it comes to credible food news and information, truth is relative, according to new U.S.-based research from The Center for Food Integrity (CFI). The study identified five consumer segments, how

each defines truth and how food news and information move through culture. It provides the food and agriculture industries insights into which segments are driving food trends and how – and where – to connect with them to earn trust.

“In its first-of-its-kind research, we

Greenwich, Nova Scotia in the heart of Annapolis Valley November 13-15, 2018

Come enjoy the Atlantic Poultry Conference and the tranquil atmosphere of the beautiful Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia

CONTACT

Bruce Rathgeber

Email: brathgeber@dal.ca

Telephone: 902-893-6654

Fax: 902-895-6734

used an innovative approach called digital ethnograpy to determine what constitutes ‘truth’ and why certain ideas get fleeting mentions while others turn into meaning ful food movements” said CFI CEO Charlie Arnot in a press release.

Through digital ethnography, CFI observed 8,500 consumers online across multiple social channels. Going back two years, the study forensically examined their behaviours, identifying beliefs, values, fears and unspoken motivations when it comes to food information.

“It’s like following digital breadcrumbs that leave a trail showing what consumers actually do, not just what they say they do,” Arnot said. “Results revealed that truth isn’t black and white in the minds of consumers.”

Credibility of information is tied to each segment’s relationship to truth. It spans a spectrum ranging from the Scientific, who defines truth as objective, evidence-based science, to the Existentialist who defines it as “what feels true.”

The Scientifics have difficulty relating to mainstream consumers so their influence extends only as far as the next segment, the Philospher, who takes the evidence-based science, simplifies it and filters it through an ethical lens.

“It’s the ethics, or in other words the values, around the issue that provide meaning to the Philospher, who wants to be on the right side of morality when it comes to people, animals, the planet and more,” Arnot said.

The Philosopher has significant influence on the middle, and largest consumer segment, the Follower. Representing 39 percent of the population, Followers fears making the wrong decision for themselves and their families when it comes to food. They want clear, unambiguous answers to their questions, and assurances that they’re doing the right thing, which Philophers provide. More importantly, they value relatable, trusted sources. That’s where shared values, or the ethics, that drive our beliefs, decisions and opinions are critical, Arnot said. “Communicating with values that others share, or can relate to, is the key to earning trust.”

Learn more at foodintegrity.org.

By Ben Kaiser

three brothers at Kaiser Ag and specializes in poultry barn construction and installations.

producers called Environmental management in the broiler house.

Finally, bird density plays a role. Most wind chill calculations are done in a lab with one or two test subjects. So, the wind can go all around their bodies. In densely packed barns, the air flow may be more restricted and could limit the effect of the airs cooling.

It’s the beginning of July and summer is truly here. Ontario is going through another heat wave and ideas on how to cool down barns start to gain importance in our every day discussions. While I have more experience in layer barns, this is a broiler feature, so I’ll do my best to focus on the meat side of the feather industry.

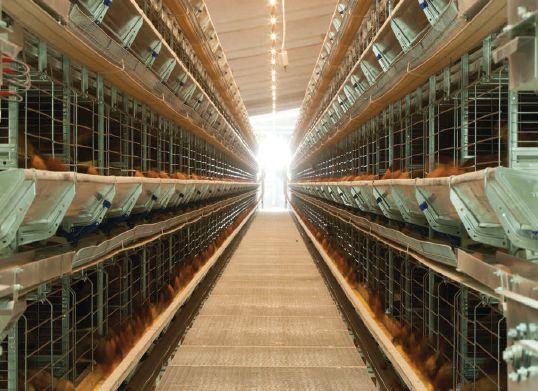

Broilers in Canada, for those who don’t know, are almost exclusively raised on litter floors. In other places in the world you can find broilers raised in cage systems. Floor raised birds tend to ha ve less breast meat bruising and damaging when compared to caged birds and this, and pressure from animal rights activists, is why it tends to be the pr eferred method in Canada.

We know that when a bird is cold, feed conversion is poor. In humans, weight

gain is a simple formula. Calories in minus calories burned is what affects our body weight.

In similar fashion, a broiler that is eating just to keep w arm is burning off calories for warmth instead of putting on body mass.

I ntense heat also has a negative impact on broilers putting on weight. Intense heat causes the birds to drink more, which fills up their stomachs and as a result they eat less. Fewer calories in equals less weight gained.

So, how to cool the barn down during periods of intense heat? Let’s talk a little bit about wind chill and the affects it has.

First of all, calculating wind chill is not an exact science. We are talking about a “perceived” temperature –how warm or cold that it feels as opposed to what the thermometer says. Secondly, wind chill isn’t necessarily

linear. A wind speed of two meters per second doesn’t always deliver an exact temperature drop.

T he starting temperature and the relative humidity also have a role to play.

Thirdly, the ∆ T (delta T) plays a role. If an object and the air have very close temperatures, heat transfer will be more limited. If the object has a higher temperature than the air, the heat transfer will be more pronounced.

Fourthly, the age of the birds also plays a role –smaller and younger birds become chilled sooner than the bigger, older birds.

Ross (Aviagen) has a simple chart in a 2010 manual they put together for broiler A broiler that is eating just to keep warm is burning off calories for warmth instead of putting on body mass.

It’s also important to know that wind chill on birds is different than wind chill on humans. Back in 2001, Environment Canada held a symposium to create a standard on wind chill effect on humans. They wanted to see what the effect was on faces in particular. This is important to remember when going over wind chill char ts because people don’t have feathers on their faces (at least as far as I know).

Watching the effect your ventilation system is having on your birds is truly the only way to understand how effective it is. All the factors mentioned above show that calculating wind chill can be a bit more of an art than an exact science. Every year, every season and every flock will be a bit different. It takes time to gain the experience to “tune” in a barn’s ventilation system.

One of my favourite business book authors is John Maxwell, who wrote a book titled Sometimes you win, sometimes you learn.

Just remember that if this past flock didn’t perform the way you wanted it to, it was an opportunity to learn for the next one.

“I am leaving with a shift in mood and motivation.”

— Pamela W.

October 14, 15 & 16, 2018

Hilton/Fallsview, Niagara Falls, Ontario

By Brett Ruffell

Amy and Patrick Kitchen moved from B.C. to Ontario several years ago intent on buying a farm. They knew from the star t they wanted to get into market gardening. Eventually, they decided on a mixed offering. “We wanted to add livestock to the equation to diversify our income and for the manure benefits,” Patrick says.

They bought a farm in Walter’s Falls, Ont., a small community in the northern part of southwestern Ontario. They named their business Sideroad Farm and started off producing crops and hogs. Later, the Kitchens added feathers to the mix, including 100 layers, a few turkeys and 300 broilers through Chicken Farmers of Ontario (CFO)’s Family Food Grower program. Things were going well but they w ere convinced they could expand the broiler side of their business. “We basically sold [our chicken] to friends and family because 300 broilers only gets you so far,” Patrick says.

Then three years ago they saw the perfect opening to scale up the

chicken side of their operation in a manageable way that wouldn’t require them to invest in quota.

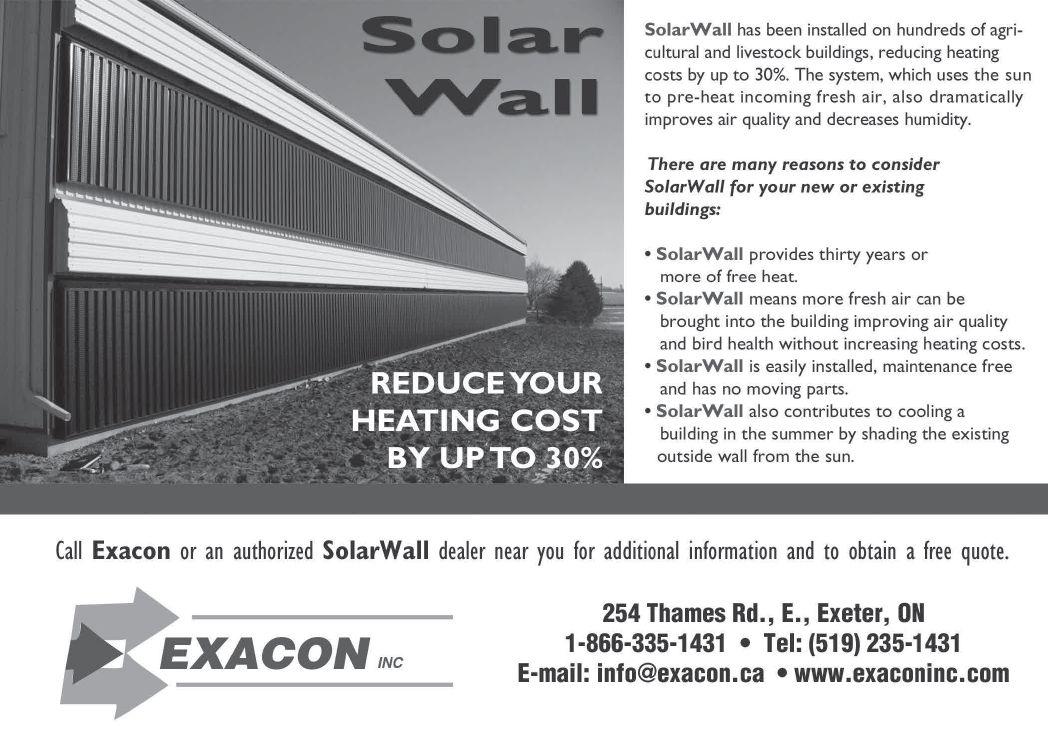

That’s when CFO launched its Artisanal Chicken Program. The first-of-its-kind in Canada, the initiative grants growers a licence to produce between 600 and 3,000 broilers without owning quota. The Kitchens jumped on the opportunity and turned it into a thriving part of their business with a diverse list of clientele.

Indeed, the initiative has been a boon for smaller, independent businesses like Sideroad Farm. And they’ve applied in droves. In just a few years, the board has approved 147 artisanal producers.

“ We’ve been overwhelmingly pleased with the success of the program to date,” says Kathryn Goodish, CFO’s communications and marketing manager.

The organization created the program, which is free to apply for, in response to a few glaring needs.

“We saw an opportunity in the marketplace to enable smaller growers to be part of the system,” Goodish says.

Because of the initiative, those smaller growers have been able to help fill the growing demand for local food options in smaller, underserved communities that aren’t necessarily a fit for larger scale operations. “A lot of customers who are buying the product have a local angle – it’s part of their value proposition,” Goodish explains. “So they’re looking to source local ingredients.”

A region where it’s been particularly impactful is northern Ontario. Before the program, there were no core producers in the region. Now, there are 24 licenced small growers. One of those farmers is Thunder Bay’s Nyomie Korcheski of Country Plaid Farm. “There simply wasn’t local chicken available before,” says Korcheski, who along with her husband is one of just two artisanal producers in her community. “Thunder Bay has local product like cheeses, sauce and eggs but chicken wasn’t available until the artisanal program.”

Because of that untouched potential, sales came naturally for the Korcheskis. They sought out a few stores and restaurants in the beginning. But it wasn’t long before businesses came calling on them looking for local pr oduce. Thus far, every unit they’ve acquired has been accounted for. Their end-of-year goal is to produce close to 3,000 birds, which is the maximum allowed under the program.

Budding producers can use the artisanal program as a stepping-stone to eventually buying qu ota as well. Take Mandy and Tony Willemse of Little Sisters Chicken, for example. Parkhill, Ont.-based farmers with successful hog and bailing businesses, the couple had long contemplated building a commercial broiler barn on their 400 acres of land. Like the Kitchens, they were looking to expand their revenue stream without having to commit to quota.

When they heard about the

artisanal program, they thought they finally had the right fit for their business. “I saw it as a good way to get into the industry,” Tony says. They started with the program in 2016, converting a 600-squar e-foot pig barn into a broiler house. Tony’s in charge of production while Mandy handles marketing. They’ve built up a healthy client base selling mostly to wholesalers but also to restaurants and grocers. They also have an on-farm market store.

“It’s worked out pretty well for us,” Tony says about the program. At the same time they’re shoring up contracts, they have their sights set on bigger things down the road. “Eventually, we’ll have to buy quota to keep our business rolling,” Tony says. The couple currently produces 600-bird

flocks but their barn can accommodate up to 2,500.

A rtisanal producers are also bringing unique product to market. Both Sideroad Farm and Lit tle Sisters Chicken produce pasture-raised chicken. “There’s a lot of demand for that,” Patrick notes. “This program has allowed us to expand to meet that demand.” The Willemses also use non- GMO feed. The Kitchens did as well but have since switched to certified organic.

Sideroad Farm’s birds start off in a brooder room the couple built. The Kitchens then put them out to pasture for an eight-week grow out under the watchful eye of a lama. They have a hut surrounded by an electric fence, which they move each year.

Apart from the marketing ap -

peal of pastured chicken, the producers say it also compliments their vegetable business. “This year our potatoes and squash are growing on our chicken ground from last year,” Tony says, citing the manure benefits. “There are a lot of synergies between livestock and market gardening.”

Since many artisanal growers are new to chicken production, they’ve had a learning curve. “I had one flock that didn’t go too great,” Tony admits. “It was just about making sure I had the right weights. I’ve had to hold onto a few birds an extra week.” He’s had a few commercial barn friends come by to help. CFO also has advisors who answer his questions. Artisanal farmers are audited

Artisanal Chicken Program by the numbers 2015 Chicken Farmers of Ontario launched the program

600 to 3,000 chickens is the range in which artisanal farmers can produce

1,534 is the average number of chickens per artisanal farmer

147 is the number of applications the board has approved

24 is the number of active artisanal growers in northern Ontario

$0 is the cost to apply for the program

24 cents is the per-bird cost producers pay

according to the board’s on-farm food safety and animal care standards. They’re given guidebooks for both programs, which Country Plaid Farm’s Korcheski refers to as her “chicken bibles”. “They force you to uphold that quality,” she says, noting that the books cover issues like stocking density and humidity control.

And producers say the audits themselves are great learning experiences. Sideroad Farm has been audited two times thus far. “To be honest, our experience with CFO has been gr eat,” Patrick says. “The auditing process is both thorough and constructive. In m y opinion there’s really a focus on making you a better farmer.”

To further help growers, CFO offers an online portal with a myriad of resources and tools. What’s more, now that the program is three years old the board is connecting new entrants with more experienced farmers for peer-to-peer learning. Those links ar e being established at annual meetings and through a Facebook page exclusively for participants to support each other. “The board is really committed to helping this group nurture their business,” Goodish sa ys.

One of the biggest challenges artisanal producers share is learning how to market their product. The Kitchens had already amassed an impressive client list from their vegetable business, which they leveraged for their chicken venture. Social media has also been huge. They use it to educate consumers about their product and how they treat their birds.

But before all that producers need to decide on their flock size. To help, the board sends reps to applicants’ farms to have frank discussions about the t heir business plans. “We really try to be realistic about how many chickens they can actually sell,” says Patricia Shanahan, who oversees the program.

The Kitchens decided on a scaled approach. They grew 1,500 birds in their first year, 2,400 the year after and now they’re up to 3,000. With a diverse mix of customers in Owen Sound, Collingwood and To -

ronto, they’ve had no issues selling product. They offer a meat delivery program and supply local restaurants. They’re even in the midst of building an on-farm store.

Where they really thrive is in farmers markets. That’s because as the local food trend grows customers are asking more questions about where their food comes from. A farmers market provides the perfect venue to interact directly with the public to educate them about their product. The couple even invite market goers to their farm to show how they care for their birds. “I think transparency is important,” Patrick says. “This is our passion so we’re more than happy to talk about it.”

Looking forward, the Kitchens are undecided about taking their broiler business to the next level.

“Whether we use it as a stepping stone or sit tight with 3,000 birds we haven’t made a final decision,” Patrick says. “But this experience would be invaluable if we do go that route.”

“We saw an opportunity in the marketplace to enable smaller growers to be part of the system.”

Meanwhile, CFO expects the program to keep expanding. It began accepting more applications in August and demand from smaller-scale farmers remains high. In addition, the organization is getting a lot of repeat growers as well. “People in the program are very pleased with their outcomes, markets and business brands,” Goodish reveals. “So they continue to grow year after year.”

A try-anything attitude propelled this young producer through the process of rejuvenating his family broiler farm.

By Jennifer Paige

After building a career in the electrical trade, Steve DeVries suddenly found himself returning to the family broiler farm. After the sudden passing of his father, the long-planned transfer of the family farm was quickly accelerated. “His passing pushed everything forward about 20 years,” he recalls.

Whil e still operating the farm, his father had insisted on getting his new daughter-in-law Kahley, whom Steve married in 2005, acquainted with farm life and the business. “I always found it really strange because my Dad would get my wife to take minutes of our farm meetings. But those minutes became invaluable after he was gone. We used them to solve disagreements and make decisions,” DeVries remembers.

As he reminisces about his childhood on the farm, it is clear there have been many changes and farm innovations over the years. “I remember he would adjust inlet vents with a hand crank,” he says. “I don’t know how he did it. Now I run both of my barns entirely from my phone.”

Today, the DeVries live on the farm in Listowel, Ont., raising their three children. They operate in a conventional system, producing 30,000 40-day birds annually, raised in two barns in eightweek cycles with 12 days between flocks.

DeVries notes that further restriction on antibiotic use is coming and so there is a greater need for bird management

these days. “Animal husbandry is huge,” he says. “As farmers we are going to have to get better at looking after these animals, caring for them and paying more attention in order to catch a lot of the issues where antibiotics have helped in the past.”

DeVries is also a firm supporter of supply management, something that has motivated him to step up and become a farmer-elected district representative with Chick en Farmers of Ontario (CFO), which holds the primary function of acting in a consultative capacity to the board

and helping to engage other local farmers “What challenged me to become a district representative was when I attended a regional event. I came to the realization that we need farmers to voice their opinions. Supply management has given me the opportunity to farm, and so I want to be a part of making sure that we do everything we can to ensure it stays viable for the next generation, and that includes getting involved at the local level.”

DeVries is one of four district representatives in CFO’s eighth district. He has been in the position for three years.

Focusing on the challenges that poultry farmers are facing to

The Government of Canada is committed to supporting the research, development, demonstration and adoption of clean technologies. To this affect, the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Lawrence MacAulay recently announced the Agricultural Clean Technology Program. This $25 million, three-year investment will help the agricultural sector reduce greenhouse gas emissions through the development and adoption of clean technologies. Provinces and territories are eligible to apply for federal funding through this program, and are encouraged to work with industry on projects that focus on precision agriculture and/or bioproducts.

Hydro One and Niagara Peninsula Energy Inc. have announced the AgriPump Rebate Program, the first program of its kind in Ontario to offer instant rebates to customers who purchase a high-efficiency pump kit. The program is ideal for all farming applications, including livestock. Upgrading to a high-efficiency pump will improve performance and could save customers up to 40 per cent of their system’s energy costs. To learn more and participate in the AgriPump Rebate program, visit: agripump.ca.

PEI has received a $23.8 million federal investment to help improve energy efficiency in homes, businesses, industries and farm operations across the province, as well as reduce carbon pollution in the forestry sector. This joint federal-provincial investment totals $47.8 million.

is the amount of coal production poultry excrement could replace, one study found.

A recent study shows that poultry excrement may have a future as a fuel for heat and electricity.

40% is the amount Ontarians could save on their system’s energy costs by upgrading to a high-efficiency pump under a new program.

Treated excrement from turkeys, chickens and other poultry, when converted to combustible solid biomass fuel, could replace approximately 10 per cent of coal used in electricity generation, reducing greenhouse gases and providing an alternative energy source, according to a study by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) researchers.

While biomass accounts for 73 per cent of renewable energy production worldwide, crops grown for energy production burden land, water and fertilizer resources.

According to the researchers, “Environmentally safe disposal of poultry excrement has become a significant problem. Converting poultry waste to solid fuel, a less resource-intensive, renewable energy source is an environmentally superior alternative that also reduces reliance on fossil fuels.”

According to the study in Elsevier’s Applied Energy , researchers at the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research at BGU evaluated two biofuel types to determine which is the more efficient poultry waste solid fuel.

They compared the production, combustion and gas emissions of biochar, which is produced by slow heating of the biomass at a temperature of 450°C in an oxygen-free furnace, with hydrochar. Hydrochar is produced by heating wet biomass to a much lower temperature of up to 250°C under pressure using a process called hydrothermal carbonization (HTC). HTC mimics natural coal formation within several hours.

“We found that poultry waste processed as hydrochar produced 24 per cent higher net energy generation,” says student researcher Vivian Mau and professor Amit Gross, chair of the department of environmental hydrology and microbiology at BGU’s Zuckerberg Institute.

“Poultry waste hydrochar generates heat at high temperatures and combusts in a similar manner to coal, an important factor in replacing it as renewable energy source.”

For the first time, the researchers also showed that higher HTC production temperatures resulted in a significant reduction in emissions of methane (CH 4) and ammonia (NH 3) and an increase of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide.

Y OU R FARM IN Y OU R HAN D.. . WH EREVE R YOU ARE

A state-of-the-art upgradable system with highly intuitive icons

Fully customizable, regardless of the building size or application.

Maximus will give you the best return on investment. No monthly fee. Free updates.

Daily customized report. Make the best decisions to maximize your results.

losses, protect your reputation.

Dealing with the high cost of food in the north is a constant challenge for producers and consumers. Through innovation and new thinking, Choice North Farms in Hay River, N.W.T., is hoping to make a difference by undertaking the PoultryPonics Dome Project, supported with funding from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor).

Choice North Farms is a private egg producing company in Hay River. Their pilot project will integrate vertical hydroponic units and poultry production in a small geodesic dome. This combination will reduce the amount of nutrients and energy required for production, while providing a good supply of quality local fresh produce and meat substitutes.

If the pilot project is successful, this innovative clean technology could be scaled and adapted in other northern communities, promoting economic diversification, reducing the cost of living and enhancing the quality of life in remote communities.

CanNor has invested $80,497 in the project through its Strategic Investments in Northern Economic Development (SINED) program,

with Choice North Farms contributing $67,910, the Government of the Northwest Territories injecting $6,586 and the Aurora Research Institute providing an additional $6,000. Total funding for the project is $160,993.

“We are thrilled at North Choice Farms to be able to pilot this green technology, thanks to the support of CanNor. We are confident it will allow us to produce more food locally while reducing our carbon footprint and production cost. This is great for our business, for the agricultural sector in the NWT and for northern consumers,“ said Kevin Wallington, business development manager, Choice North Farms.

The story starts in 2014, when Glenn Scott (founder of Whitehorse-based Agri-Arctic Yukon) created the “AgriDome,” a modified northern survival structure made from available construction materials that’s designed to support hundreds of plants. It features vertical hydroponic growing towers, remote computer monitoring and high-pressure sodium (HPS) lighting, with heat provided by a standard 1,500-watt space heater.

The Yukon Research Centre at Yukon College provided funding and hosted the AgriDome project, which started in September 2014. Scott submitted a feasibility study in January 2016, with average power usage found to be 1.9 kilowatt-hours.

But Scott wasn’t satisfied. He’s among many who believe the heat, light and other synergies of a greenhouse should be used to support production of protein as well. In 2015, he was speaking to Kevin Wallington (head of marketing and sales at Polar Egg in Hay River) about the possibility of combining vegetable and egg production.

They brainstormed and approached CanNor, the Aurora Research Institute and the N.W.T. Ministry of Industry, Tourism and Investment to help complete their joint demonstration project. The rest is history in the making.

The hens, about 200 of them, will be housed in a hexagonal base structure. The AgriDome situated above will have new hydroponics towers that will support the growth of 2,500 to 3,000 plants. Initially they will grow tomatoes, peppers, basil, kale and swiss chard, adding other plants later on.

Wallington says the 200 hens will have the same amount of space as they would in any other free-range housing set-up, with access to the outside in the summer. The eggs will be graded at the Polar Egg grading station (accredited by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency) with the rest of the company’s production. The “poultryponics” eggs could be marketed separately in the future, however, as free-range eggs, if Polar Egg completes plans to modify one of its barns to free-range production with an outdoor enclosure.

$160K is the toal amount of funding the Dome Project has received.

200 is the number of hens that will be housed in the dome.

BY TIM LAMBERT

Backed by the stability and predictability offered by supply management, a green shift is happening across rural Canada. One such farmer at the cutting edge of this new wave is Manitoba’s Abe Loewen. He recently invested in solar panels to heat and cool the family home, alongside his entire barn – home to 12,600 hens.

Loewen first bought his egg farm in 1999. “We were cattle producers before that, and started farming in 1991,” Loewen says. The ‘we’ here is Abe and his wife Trudy. Prior to 1999, they were working his father-inlaw’s land – and there simply wasn’t enough to go around. “I always thought chickens would make a nice living for us if we could get into it,” Loewen says. “So when a farm came up for sale, we put an offer in.”

What did joining the egg industry feel like? “Just amazing. It meant stable work, and we could make a fair return. I was so happy to become

an egg farmer. And, it was all because of supply management.”

Two decades later, it was that same stability that helped put Loewen’s farm through a green shift: the installation of an array of solar panels. The shift began with Abe’s son Dylan. He attended an agriculture show in Brandon, Man., where he learned more about the possibilities of solar power on farms. “Dylan showed me the numbers,” Loewen recalls. “Basically, the panels pay for themselves after 12 years, and we get free power after that.”

Power that pays for itself is enticing for farmers like Abe. “Power on the barn is extremely expensive,” Loewen says. But the investment is so much more. “Doing what is good for the environment, being a good, smart steward of the land, I really enjoy that work,” Loewen says, adding with pride, “The industry is already a leader in environmental stewardship.”

High performance. Energy efficient.

Intelligent design. Long durability.

BlueFan is designed specifically for the harsh livestock house environment. It does not corrode and shuts tightly when not in use. BlueFan saves energy and money and ensures the animals in the livestock house optimum climate and well-being. BlueFan is the best fan on the market.

Read more at www.skov.com or contact your authorized SKOV distributor:

County Line Equipment Ltd. 8582 Hwy 23 N., Listowel ON PH: 800-463-7622 www.county-line.ca

BY JOSE LUIS JANUARIO, Cobb-Vantress South America

Ceiling insulation and enclosed houses with multiple insulation methods are crucial to the efficient operation of a poultry house.

Good insulation minimizes heat intake in the summer and heat loss in the winter, reduces condensation levels and litter moisture problems and increases the life of a house. With a wide variety of insulation materials available, producers must decide which type works best for them.

Each type of material offers a different level of insulation capacity to meet producers’ needs, which is expressed by a resistance value (R-value). The higher the R-value, the more effective the material is at preventing heat transfer.

One of the most common misconceptions about poultry houses is that, during hot weather, most of the heat that causes heat stress enters the house through the ceiling. Those who have ever been on the roof or in the attic of a poultry house on a summer day can understand why people make this assumption. Studies have shown that metal roofs can get as hot as 160°F, and attic temperature can easily exceed 130°F in hot southern climates.

However, under most circumstances, the number one source of heat in a poultry house is the birds. As birds digest feed, they produce heat. The bigger the bird, the more feed it eats and the more heat it produces. A bird will produce about five BTUs (the amount of heat required to increase the temperature of a pound of water one-degree Fahrenheit) of heat per hour for every pound of body weight. So, a 1.4 kg bird will produce 15 BTUs of heat and a 2.7 kg bird will produce 30 BTUs of heat each hour with no caloric stress. This may not seem like a lot of heat until you consider that there are usually close to 20,000 birds in a 40-foot (12 meters) by 400-foot (121 meters) house, bringing the total BTUs of heat produced each hour to 500,000 BTUs or more.

THE

What about the ceiling? If the ceiling is insulated, relatively little of the heat produced by the sun makes it into the house. Even with a relatively small bird (under 1.8 kg), the birds are producing five times the amount of heat that is coming through the ceiling. Greater still is the heat produced by larger birds, which is often seven times more than ceilings. This is not to say that the ceiling heat has no effect on house temperature, but the effect is relatively small compared

to the heat produced by the birds.

When air enters a house, it is warmed by the heat produced by the birds and the heat coming through the ceiling. How much the air heats up is determined by the total amount of heat produced in the house and how long the air remains there.

Having quality ceiling insulation is of significant benefit to poultry producers year-round. During cold weather, hot air produced by the brooders, furnaces and the birds quickly rises toward the ceiling. If the ceiling is not properly insulated, this valuable heat will

pass through it, resulting in lower temperatures and higher heating costs. Conversely, during summertime, ceiling insulation keeps the amount of heat entering the house through the ceiling to a minimum. On a hot summer day, attic temperatures in dropped-ceiling houses

can easily exceed 130°F. If a ceiling is not properly insulated, heat from the attic space will enter the house, leading to higher house temperatures and lower bird performance.

The most common form of insulating material used in dropped ceilings today is

blown cellulose insulation. Blown cellulose insulation has a good R-value, is relatively easy to install and is inexpensive. When properly installed, blown cellulose insulation has proven to be a very effective insulating material for dropped ceiling poultry houses; however, it is not without problems.

The most common problem with blown cellulose insulation is its tendency to “slide” away from the peak of the ceiling, which can leave that area with little or no insulation. The movement of the cellulose insulation away from the peak of the ceiling is generally caused by the fact that most dropped ceilings are sloped, the plastic used to support the insulation is relatively slick and constant cycling of exhaust fans can cause the ceiling to vibrate. Additionally, if the eave openings into the attic space are too large, strong winds have a tendency to blow the insulation away from the sidewall. For the most part, this problem can be adequately handled by minimizing the size of attic eave openings.

Insulation shifting can be a difficult and costly problem to solve. Traditionally, many producers simply blow more cellulose in the areas that have thinned over time, while others may place 10-foot-long fiberglass batt insulation at the peak of the ceiling. And now there is a third option: blown stabilized fiberglass insulation. This is a product with special binders that causes the fiberglass insulation to stick together after it is installed. Originally, this technique was developed for use in ceilings in residential houses with slopes as high as 45 degrees where it is challenging to get a blown insulation to stay in place. Over the past few years, it has been installed in a number of both new and existing poultry houses and the results look promising.

For producers with simple, older houses and no financial means to improve the housing str ucture, we suggest planting trees or installing nets to shade the sides of the house. Even this simple fix can create better conditions for the birds.

For a table listing the R-value of each material, view the online version of this article.

Continued from page 24

“Steve was eager to know more about the industry, how he could get involved and how he could broaden his leadership skills,” says Mark Hermann, board director of District 8 and second vicechair of CFO. He adds that in many cases

the district representative role is an initial step towards further leadership in the organization.

Prior to taking on the farm, in 2004 DeVries invested himself in the electrical

trade. He began his career working primarily in feed mills before moving on to work on poultr y farms. For four years DeVries worked with a poultry barn equipment and automations company, installing barn controls for water, heat, ventilation and preparing the barn for a new crop of chickens.

“Getting into the chicken industry, there is a huge learning curve. It was my job to help other producers walk through the process of making sure the barn was properly set up,” DeVries says. “You get to see a little bit of everything. You see guys that are really innovative and are willing to try different approaches to growing a bird. I learnt so much on the job that I could apply on my own farm, like being able to improve chick performance in the first seven days, things like that.”

In 2017, DeVries launched his own electrical business – Gotham Electric –which he operates congruently with his poultry farm. “That was probably the best decision I have ever made,” he says. “Being on my own has given me the freedom to be able to go where I am needed.”

Hermann adds that DeVries’ background in the electrical industry gives him a unique perspective during industr y conversations. “He always has ideas and input. He also has a really good technical background, so it is always really interesting to talk to him about technology in the barns and how that is progressing.”

DeVries has recently turned his entrepreneurial energy towards another new project, an agriculture technology company launched by his brother-in-law called BinSentr y.

It has developed a sustainable (solar and battery-powered) Internet of Things sensor that installs in the top of feed bins and connects with feed mills to give them live volume/tonnage information for feed tracking, consumption data and supply management optimization. The sensor eliminates the need for anyone to climb feed bins and reduces the chances of animals going without feed.

With DeVries’ desire to be involved in the industry and his innovative mind, the rising star is bound to find continued success on his farm and elsewhere.

By Cindy Huitema

Since last September, Cindy Huitema, egg producer from Haldimand County, Ont., has been documenting her family’s journey transitioning to a new layer housing system with her blog, Cindy Egg Farmerette. In the final installment of her blog, Cindy discusses the process of placing her initial flock and how everyone on the farm is adapting to the new enriched barn and its added technology.

Alot has occurred since the last blog, written just prior to the new flock of laying hens arriving to their habitat of Farmer Automatic Enriched Colony Housing in the new barn.

Electrical was still being worked on the day prior to putting hens in, feed arrived a day or two before and we were still cleaning things up. We quickly realized that it was going to be much easier to do jobs in the barn before the hens came, with the housing empty.

Basically, we went through the barn row-by-row, checking each house to be sure something was not missing or put together incorrectly. For instance, we made sure all of the in-house lighting cords were all zip-tied to housing walls and ceilings so the hens would not be enticed to play with any loops in the cord.

The hens arrived on Friday, May 18, and because we designed room in the barn to build another row of housing, there was lots of space for bringing the carts in. As there were no animals in the barn before,

it was extremely clean.

We decided to have housing lights and wall lights on initially so we could have a good view of the birds and their behaviour, and so they could adjust to their new surroundings.

The in-house lighting and barn wall lights have a dimmable feature that is controlled from the ante room.

Lights can be dimmed downwards from

100 per cent to zero per cent, and there is a knob that you can manually turn to dim if you need to.

We also have the dimming programmed through the Genius system to gradually turn brighter in the morning over a period of a few minutes when the hens get woken up, and gradually dim over a period of 15 minutes when late afternoon sleep time comes. In our old barn, the

lights popped on and off, and this always startled the hens and caused a lot of noise and movement. With the “gradual” feature, this drastically deceases the stress levels of the hens. Just think, if you are sleeping and someone comes in your room and turns on the light, are you not a little ticked and startled?

The Genius controller is in the ante room and is like the brain of the barn. You can see at a glance what is going on the barn, from how many fans are running and at what speed, to water and feed consumption, barn and cooler temperatures, feed schedule, mortality and more.

Our daughter, and recent graduate, Charlotte has stepped into an Egg Farmerette-in-training role rather easily. And, she was surprised how much more there is to learn. She is taking over more of the record keeping, barn cleaning and ante room routines.

Initially, Charlotte and our son John were much more compatible and versed in the operation of the Genius controller. But, the more we use different components of the Genius, we become more comfortable with the controls.

We purchased a refurbished packer from Gary Nairn, who is a local egg farmer and handy machinist when it comes to rebuilding used packers. The packer came about a week prior to the hen install and we have never had one before.

I grew up picking eggs by hand from in front of cages that had two or three hens in them. Our farm here had a laying barn with conventional housing with five or six birds in a unit, and the eggs came to the front of the

barn on egg belts and we would pack the eggs into flats.

Everyone was very anticipatory with the new packer as the eggs still come to the front of the barn on egg belts, but then go from elevators to a cross-conveyor that brings the eggs into the packing room.

John is home for the summer from university and, in addition to his off-farm job, he was good at getting the packer working, understanding its mechanics and spotting any housing issues.

The egg packer puts the eggs in trays, advances the trays by belt to a side table and we stack them into stacks of six to put on skids. In the old barn we would gather eggs twice a day – morning and afternoon. But now, in the new barn, we only gather eggs once a day, in the morning, and we find that the packer saves time. It is also a nicer environment, in a separate room from the hens, and seems to be a more enjoyable task.

Perhaps being newbies at using a packer, we are being a bit pretentious – however, I thoroughly embrace this new routine and do not miss some of the struggles and environment of the old barn.

Looking to the future, we feel we have made a good decision in our hen housing choice and thus far we are enjoying 98 per cent egg production and low mortality with the new housing and barn.

I would like to thank Canadian Poultry for making this an enjoyable experience. Also, I would like to thank my husband Nick and children Stephanie, Nicole, Charlotte and John for their encouragement and support throughout my blogging journey.

By Treena Hein

As has been done periodically since it was created decades ago, the Canada Food Guide is being updated again, this time as par t of a new Healthy Eating Strategy launched by Health Canada in the fall of 2016. Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) and some other groups and individuals have concerns over proposed updates to the guide that relate to a focus on plantbased proteins.

“Since the launch of the strategy, CFC has been trying to have concerns addressed relating to how the new food guide not only shuts out animal protein, but has cut the nutritional expertise of many organizations out of the consultations as well,” notes CFC manager of communications Lisa Bishop -Spencer. “With the active participation of special interest groups who have been mobilized to drive changes to the guide, there are concerns that these groups are acting

with the ultimate objective of dictating what Canadians can and cannot eat. A non-science-based, emotional opposition to animal proteins is not in the best interests of Canadians and their best nutritional interests. We feel that to overlook the information and expertise that agriculture organizations can offer is not in the best interests of Canadians.”

CFC has tried to ensure that the voice of Canada’s chicken farmers is being heard through a wide variety of means, such as multiple letters to the health minister, briefings with the minister of health and the minister of agriculture and agri-food and their staffs, participation in two Health Canada public consultation rounds, sending out calls to action to farmers and more.

Specifically, CFC is concerned that in the detailed summary of the new guiding principles, poultry is described as a ‘nutritious everyday food,’ but that this designation is not clear within the general

description, where plant-based sources of protein are highlighted instead. “This absence of information about protein sources in the general description will mislead Canadians, as it will be the most frequently and easily read,” BishopSpencer notes.

“Furthermore, according to protein quantity and protein quality assessments, plant sources of protein are generally inferior to animal sources of protein, and the new recommendations fail to communicate this,” she states. “Researchers have developed many methods for evaluating the quality of a food protein; it is measured by its amino acids, its digestibility and by how well it meets human needs.” Bishop-Spencer also points out that plant-based sources of protein contribute additional carbohydrates and fat to a person’s diet, which has an effect on overall caloric intake and could contribute to establishing an overall unhealthy w eight. She says chicken is the most

affordable and among the leanest of the meat proteins, offering Canadians the ability to meet their daily requirements for protein and several other important nutrients, without going overboard on daily calories, fat and carbohydrates (depending on cooking method).

CFC was asked to present before the Standing Committee on Health (HESA) at the House of Commons in early June, but the session was cancelled due to several factors. CFC therefore had to submit its concerns in written form.