CARLOS ALBERTO ESPINAL

CARLOS ALBERTO ESPINAL

By Mari-Len De Guzman

This year marked some important events in land-based recirculating aquaculture that have given the sector a brighter path forward.

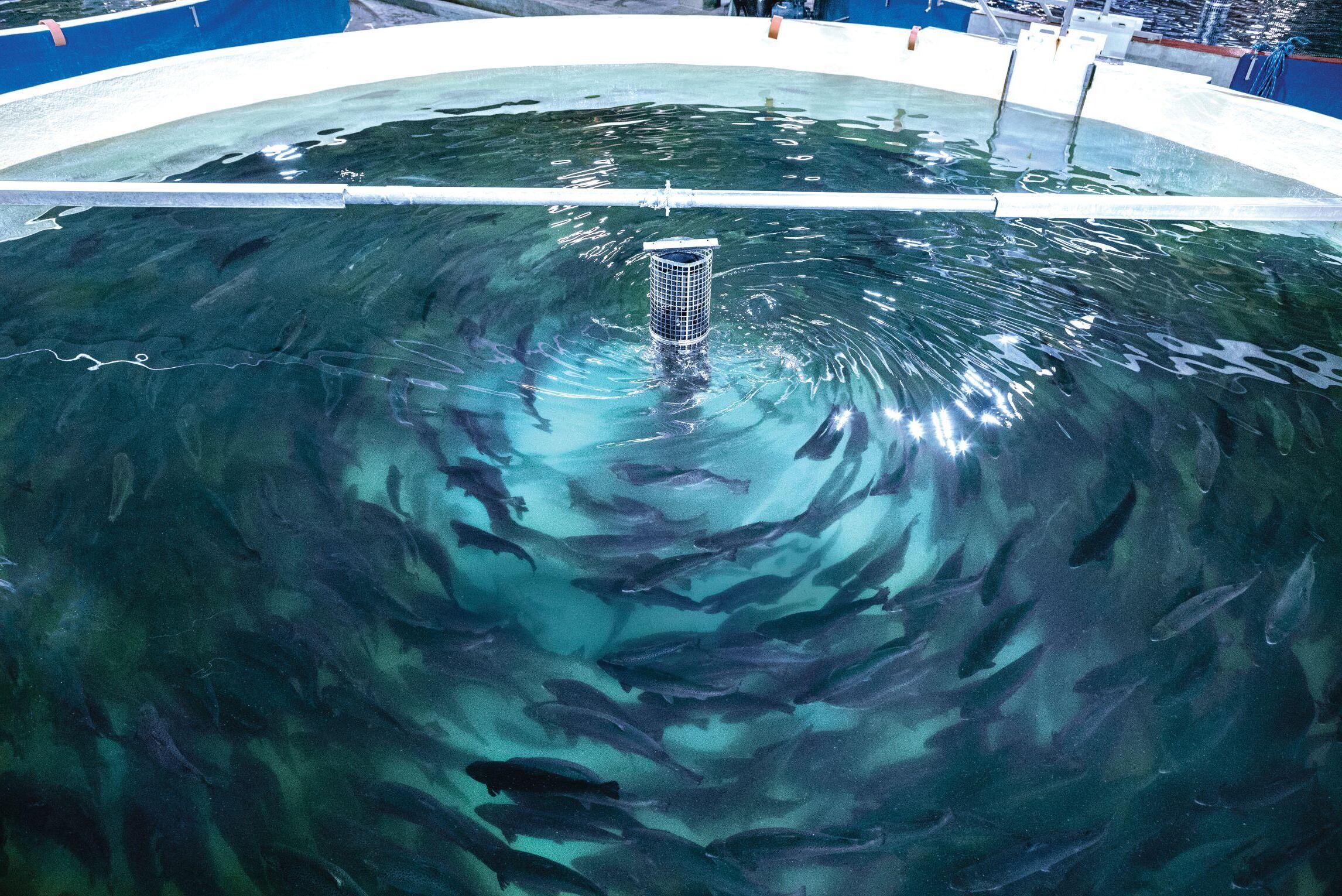

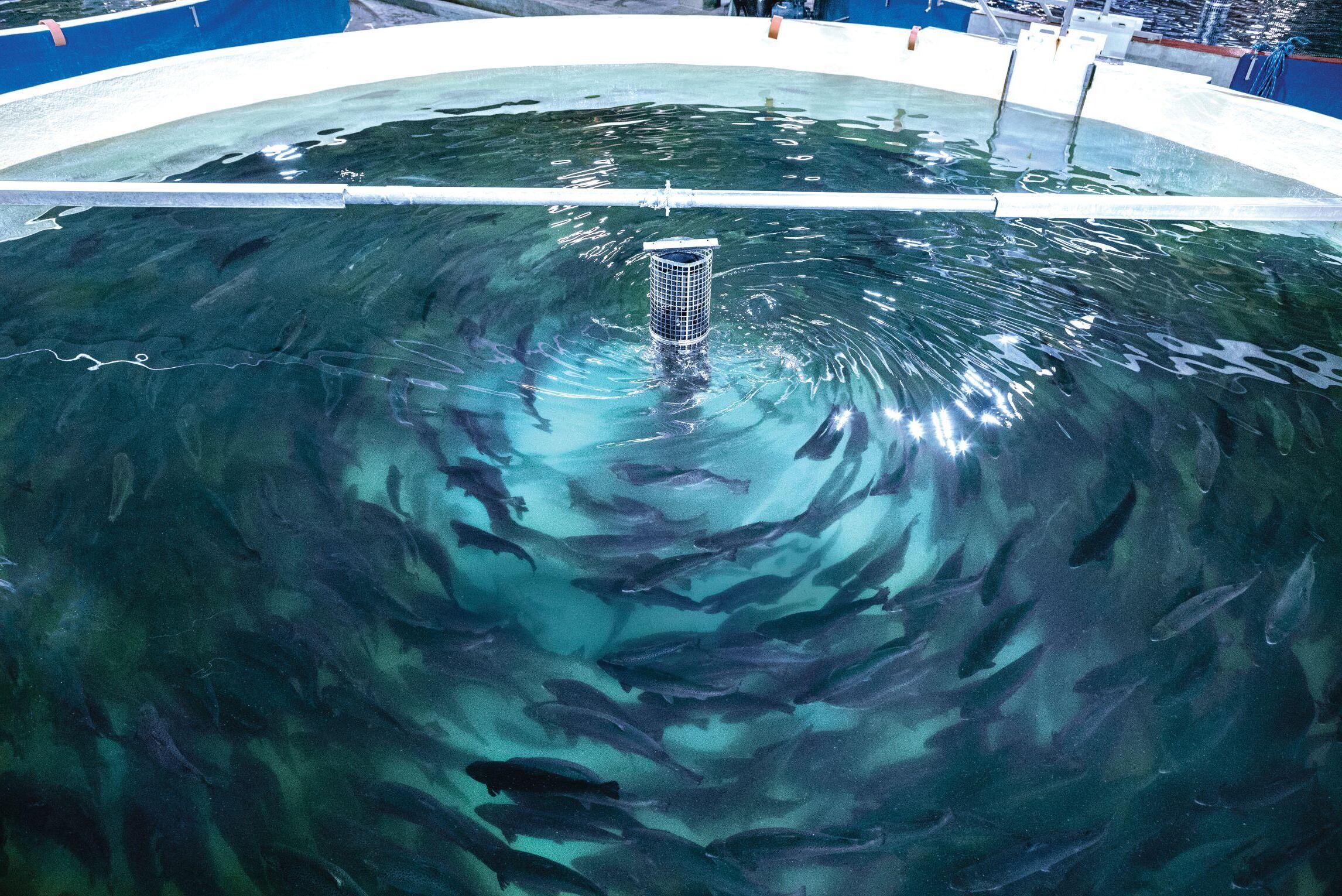

The much-anticipated harvest from Atlantic Sapphire’s Bluehouse facility in Florida was certainly an important event not just for the salmon producer but for the entire spectrum of RAS production. This is the first time a largescale RAS operation in the U.S. has come full circle in its production from egg to harvest, exclusively on land. It’s not really the “first time” a company has harvested fish in a full RAS production environment, as others have had relative success with this, but it is the first for such a big scale.

Most of the large-scale RAS projects are currently either under construction, in the permitting process or in the process of commencing production. Recent developments also signal an expansion of species that are being farmed in these large RAS facilities. One of them is the high-value Yellowtail kingfish.

The Kingfish Company, which has been farming Yellowtail in RAS at its facility in the Netherlands, has announced a significant expansion into the U.S. market with a planned 8,000ton RAS facility in Jonesport, Maine. This is a significant jump from the current 600-ton production capacity at its Kats, Netherlands facility – although the company also plans to expand that to 5,000 tons in the near future.

We can’t talk about developments in 2020 without highlighting the global

pandemic that has wreaked havoc not just in public health systems but in markets and industries around the world. But this pandemic, for all its ugly consequences, had a silver lining, particularly for sustainable food production. International border closures meant significant challenges in the global transport of food supplies, increasing opportunities for local producers to supply the market.

In the seafood world, the global pandemic gave RAS producers a chance to shine, to show agility and adaptability to sudden market changes and pivot their production and sales and distribution strategies.

And shine they did.

When restaurant and hotel industries – a major clientele for RAS producers – were forced to shut down at the height of the pandemic, RAS producers found another market: wholesale, retail and online. The market has changed in a span of three months, and the RAS sector has shown it can adapt to those changes.

As we move into a new year, still on the heels of this global pandemic and many major markets in recovery mode, the outlook seems promising. As more of the large-scale projects come online and the small-scale RAS producers continue to stay competitive and become beacons of sustainable food production, the mainstream marketplace will gradually come to know the benefits and the value of locally-grown, sustainably-raised seafood. And the world will be better for it.

www.rastechmagazine.com

Editor Mari-Len De Guzman 289-259-1408 mdeguzman@annexbusinessmedia.com

Associate Editor Jean Ko Din 437-990-1107 jkodin@annexbusinessmedia.com

Advertising Manager Jeremy Thain 250-474-3982 jthain@annexbusinessmedia.com

Media Designer Jaime Ratcliffe 519-429-5191 ext 4191 jratcliffe@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator Morgen Balch 519-429-5183 mbalch@annexbusinessmedia.com

Circulation Manager Urszula Grzyb 416-442-5600 ext 3537 ugrzyb@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher Todd Humber thumber@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Printed in Canada

SUBSCRIPTION

RAStech is published as a supplement to Hatchery International and Aquaculture North America.

CIRCULATION email: blao@annexbusinesmedia.com Tel: 416.442-5600 ext 3552 Fax: 416.510.6875 (main) 416.442-2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Occasionally, RAStech will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800.668.2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2020 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

An aquaculture company based in Switzerland has announced plans to build a land-based recirculating aquaculture facility in France’s leading fish port.

Local Ocean GmBH is eyeing Calais Port, in Boulogne Sur Mer, in northern France, as the site for a land-based salmon farm capable of producing up to15,000 tons of fish. The Société d’exploitation des ports du Détroit (Detroit Ports Operating Corporation), a public limited company which was created to develop the Calais Port, is also involved in the project.

The company intends to produce 8,500 tons of 5-kilogram commercial-sized salmon in its first harvest, according to report from industry news site SalmonBusiness.com

Local Ocean is expected to spend about US$126 million in purchasing and developing the 45,500/sq. m. site.

New York-based Finger Lakes Fish, which operates under the brand Local Coho, has raised US$4.6 million in its Series A funding.

The company aims to raise 350 metric tons of Coho salmon in its 43,000-squarefoot recirculating aquaculture system facility in Auburn, Cayuga County.

A post on the company’s website identified the “key strategic partners” in the venture as Jim Murphy, president of Grow Forward, a company that specializes in indoor aquaculture; Bob Tobin, former chief

executive officer of Ahold USA; and Steve Koch who used to run the global mergers and acquisitions business of Credit Suisse.

Europe-based Devonian Capital, which invests in land-based aquaculture, is also a key advisor of Local Coho.

Local Coho hatched its first cohort of eggs in April 2018. The company sold its first batch of Coho salmon in September 2019.

The company is focused on local, sustainable and fresh production in a healthy and safe environment for its Coho salmon.

Work has started on a facility that will soon be Spain’s first recirculating aquaculture system farm for Atlantic salmon.

The Spanish firm NorCantabric has invested US$37.4 million into the project. The company aims to become the “trigger” for salmon farming in the region.

Last spring, the regional government of Cantabria in northern Spain announced it has approved a €1 million (US$1.2 million) grant to NorCantabric. The grant was co-financed by the Ministry of Rural Development, Fisheries and Food and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund.

The RAS facility, which is being built in

a 25,000-sq.m. lot in the Alto Asón Business Park, in Riancho, Ramales de la Victoria, is expected to begin operations in 2021.

NorCantabric will use a recirculating aquaculture system based on the technology of Danish company Alpha-Aqua. The Spanish firm aims to produce 3,000 tons of high-quality Atlantic salmon, according to the Spanish media outlet El Faradio. That figure represents four to five per cent of the Atlantic salmon market in Spain.

The first phase of the construction project will involve the establishment of a hatchery, the company said.

Aquaculture technology supplier AKVA Group has landed a lucrative deal to design a number of land-based salmon farms in the Middle East.

The Norwegian company announced that its AKVA Group Land-Based division has entered into a design and cooperation agreement with Dubai-based Vikings Label.

The Scandinavian company is relatively new in the RAS scene., starting out as an importer of salmon into Dubai. In late 2018, Vikings Label announced plans to enter the land-based salmon farming industry.

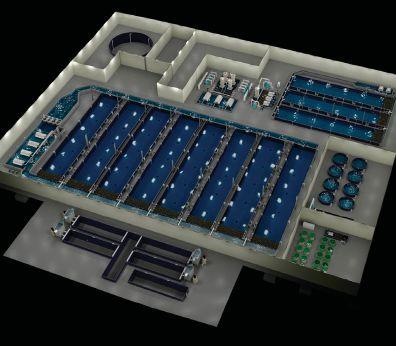

Vikings envisions a 50,000-ton RAS compound sustainably producing locally-consumed fish species in the middle of a desert. The project will also include a research center, education center, a feed mill and an algae plant.

Chief technology officer, Morten Malle, said Vikings Label decided to partner with AKVA because of the firm’s experience in RAS technology.

“Only a few RAS suppliers have long-term experience in the design, construction, and operation of modern land-based fish farming in this region, AKVA group being one of them,” he said.

Go for all-female populations to reduce maturation and optimize your production output

Check out our new product range SalmoRAS4+ and SalmoRAS4+IPN, optimized for full-cycle salmon farming in land-based RAS-system. Both products have All-female (only female populations) as standard and are highly selected for strong growth. Triploid is an additional optional treatment that makes the females sterile, resulting in zero maturation. That is what we call Girl Power! Find out more at www.stofnfiskur.is/products or contact:

Róbert Rúnarsson

Manager

Nordic Aquafarms Inc. has announced it has aquired the remaining shares of Danish firms Maximus A/S and Sashimi Royal A/S, making both companies now fully owned subsidiaries .

“With this acquisition we strengthen our biological diversification and expand the opportunity space for future projects globally,” said Bernt Olav Røttingsnes, Nordic Aquafarms CEO.

Nordic Aquafarms signed an agreement with Sustainable Seafood Invest (SSI) to purchase the remaining 50 per cent of shares in Maximus and 32.5 per cent shares in Sashimi Royal.

Sashimi Royal is the first large-scale producer of premium Yellowtail kingfish in Northern Europe. Maximus produces Yellowtail fingerlings exclusively for its sister company, Sashimi Royal.

Total annual harvest capacity is approximately 900 metric tons, with potential for substantial on-site capacity expansion. The companies have produced Yellowtail kingfish since 2017 with harvest and sales since 2018. The product is primarily sold to the premium hotel, restaurant and catering markets in Europe.

The full acquisition of large-scale Yellowtail RAS producer Sashimi Royal and Maximus A/S signals Nordic Aquafarms’ intent to strengthen its high-value species portfolio.

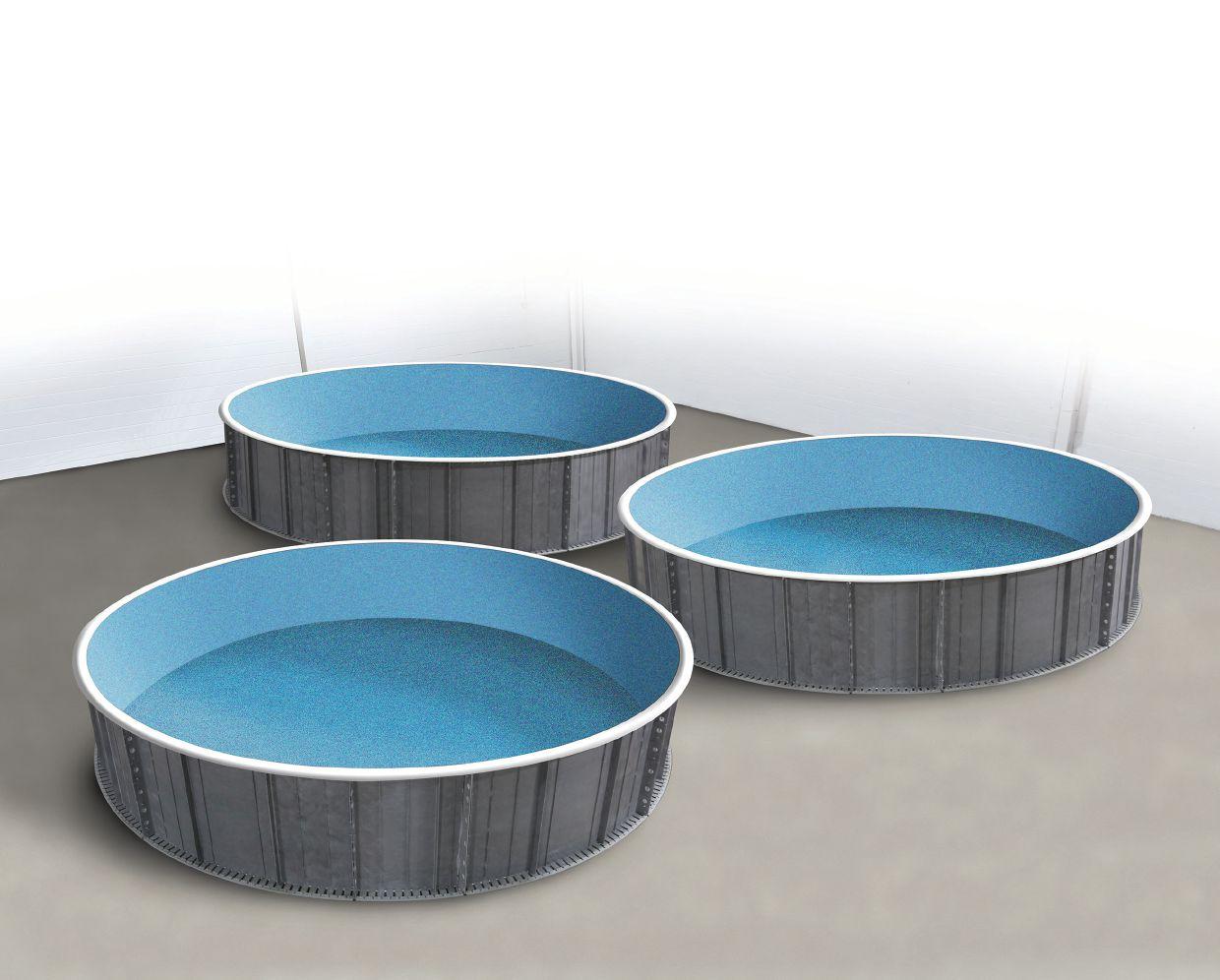

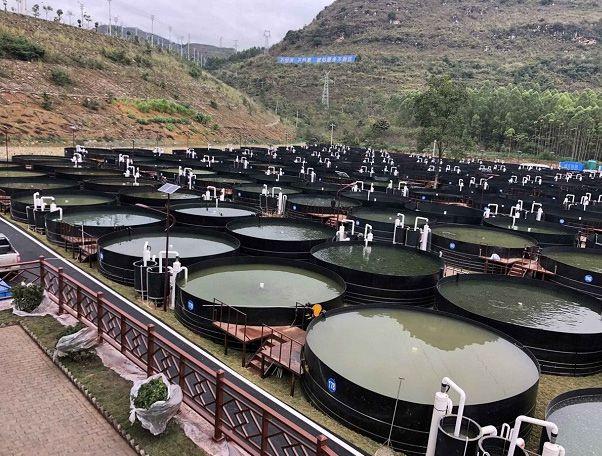

Aquaculture equipment maker Nocera Inc. says it is rolling out a new line of recirculating aquaculture system tanks with significantly increased capacity.

Improvements made to the existing

oxygenation system allows approximately 50 per cent more fish to be raised in the tanks, the company said.

The tanks are designed to improve productivity and sustainability in commercial aquaculture applications.

“Our next-generation recirculating aquaculture system is larger and improves oxygen utilization, which means better fish,” said Jeff Cheng, chief executive officer of Nocera, Inc.

“This represents an environmentally-friendly and cost-effective way to bring clean fish to the table while returning clean water back to the environment.”

Nocera designs, builds and installs

equipment for the fish farming industry. The company also provides technical assistance to the operators of the equipment.

The company’s land-based RAS can be used for saltwater and freshwater species, including tilapia, perch, bass, crayfish, crab and abalone.

Nocera’s RAS tanks can produce 20,000 to 30,000 lbs. of fish annually. The company plans to install its next-generation tanks in Taiwan.

In January, Nocera also signed a contract with Procare International Co. Ltd. to build and install 6,500 RAS tanks for a land-based fish farm facility in the township of Ru Hu in China’s Guang Dong province.

Days after its successful bid for a permit critical to its recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) project in the U.S., The Kingfish Company announced plans for an initial public offering (IPO) at Oslo’s Merkur Market.

The land-based yellowtail farmer’s fundraising coincides with the acceleration of the company’s roll-out plans in both the U.S. and Europe.

“We are excited by our recent progress across production, sales and expansion activities, and view the Oslo Merkur Market an enabling platform as we look to scale up our business and transform our first mover position into a long term competitive advantage as a vertically integrated RAS aquaculture operator in the E.U. and the U.S.,” said Ohad Maiman, CEO of The Kingfish Company.

In late September, the company moved one step closer to realizing its plans to build a major RAS production facility in the U.S. The Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands finalized The Kingfish Company’s submerged lands lease application for the installation of intake and discharge pipes. The company plans to build a land-based RAS facility in Jonesport, Maine, to produce between 6,000 and 8,000 metric tons of yellowtail annually.

The fundraising and listing process will be led by financial advisors

DNB Bank (Global Coordinators); Arctic Securities (Joint Bookrunner); and Rabobank & Swedbank, in cooperation with Kepler Cheuvreux (Joint Bookrunner); legal advisors, Wikborg Rein (Norway); and DeRoos (Netherlands), according to a press release from The Kingfish Company.

The round is expected to be substantially supported by the company’s largest shareholders – Rabobank Corporate Investments (RCI) and the French Mulliez family office, Creadev.

Apart from its project in the U.S., The Kingfish Company also plans to expand its European business.

The company is increasing the installed capacity of its facility in the Netherlands from 1,250 to 2,750 tons per year.

The company’s Dutch subsidiary, Kingfish Zeeland, recorded substantial production improvements and redirected volumes in Europe to retail due to COVID-19.

At the height of the hotel, restaurant, and catering closures, Kingfish Zeeland managed to land a contract with retail giant Whole Foods Market in the United Kingdom.

Previous studies have shown that exercise improves fish health and growth. A recent research now indicates that giving fish ample resting time before they are harvested and slaughtered results in better quality fillets.

Results of the study can be useful for operators of aquaculture facilities in developing protocols relating to the management of fish stocks as well as harvesting procedures. The researchers found that incorporating adequate resting time for fish to pre-harvest procedures can avoid factors that are detrimental to fish meat quality.

“In aquaculture, the procedures involved in pre-slaughter management are recognized as a critical point in the management of fish welfare and have important effects on meat quality,” according Letícia Emiliani Fantini, a graduate in animal science from the Mato Grosso do Sul State University, in

Brazil.

Fantini and her colleagues conducted a study funded by Brazil’s National Research Council- CNPq and the Federal University of Grande Dourados. The study was carried out using surubim (Pseudoplatystoma spp.) , a South American catfish specie.

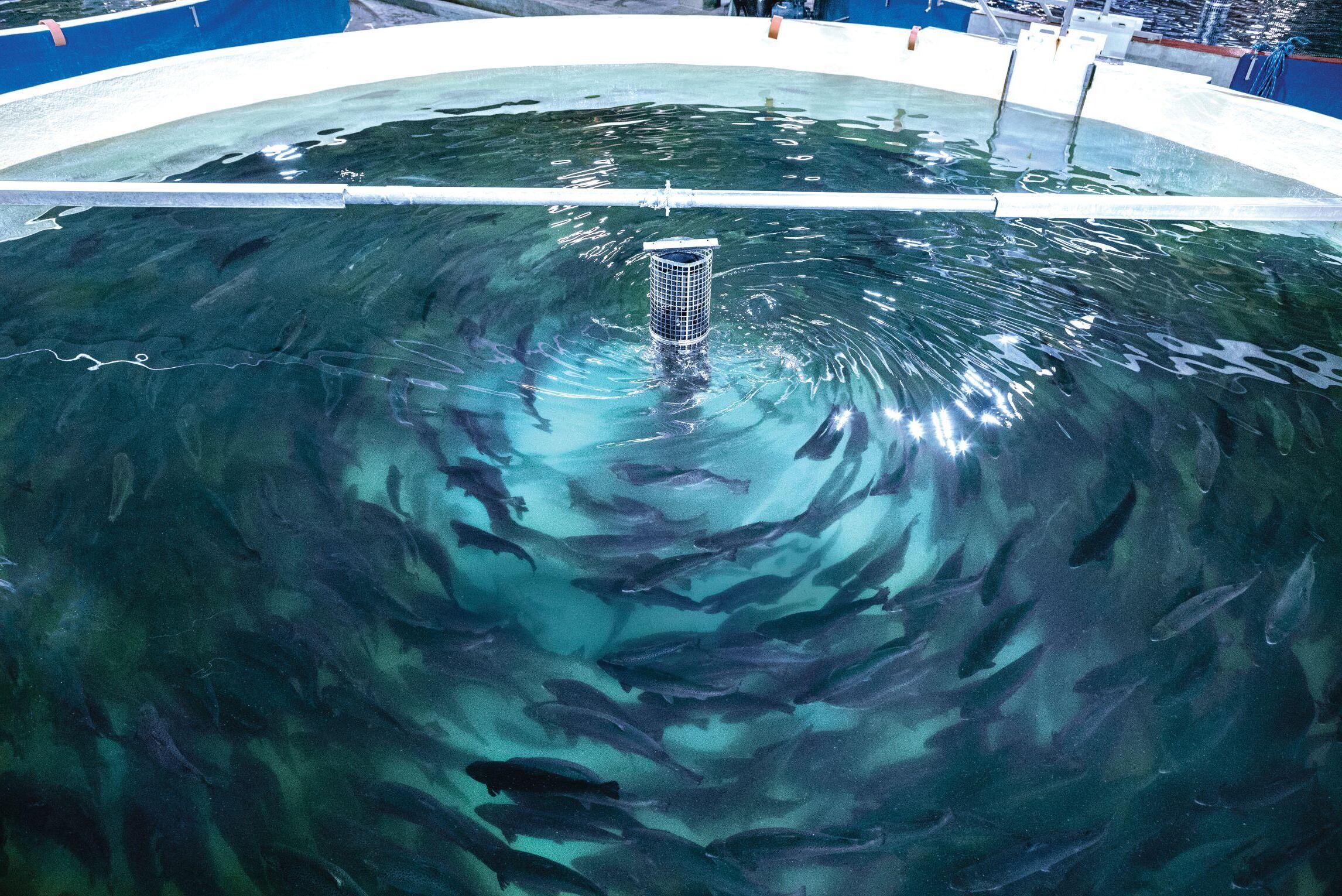

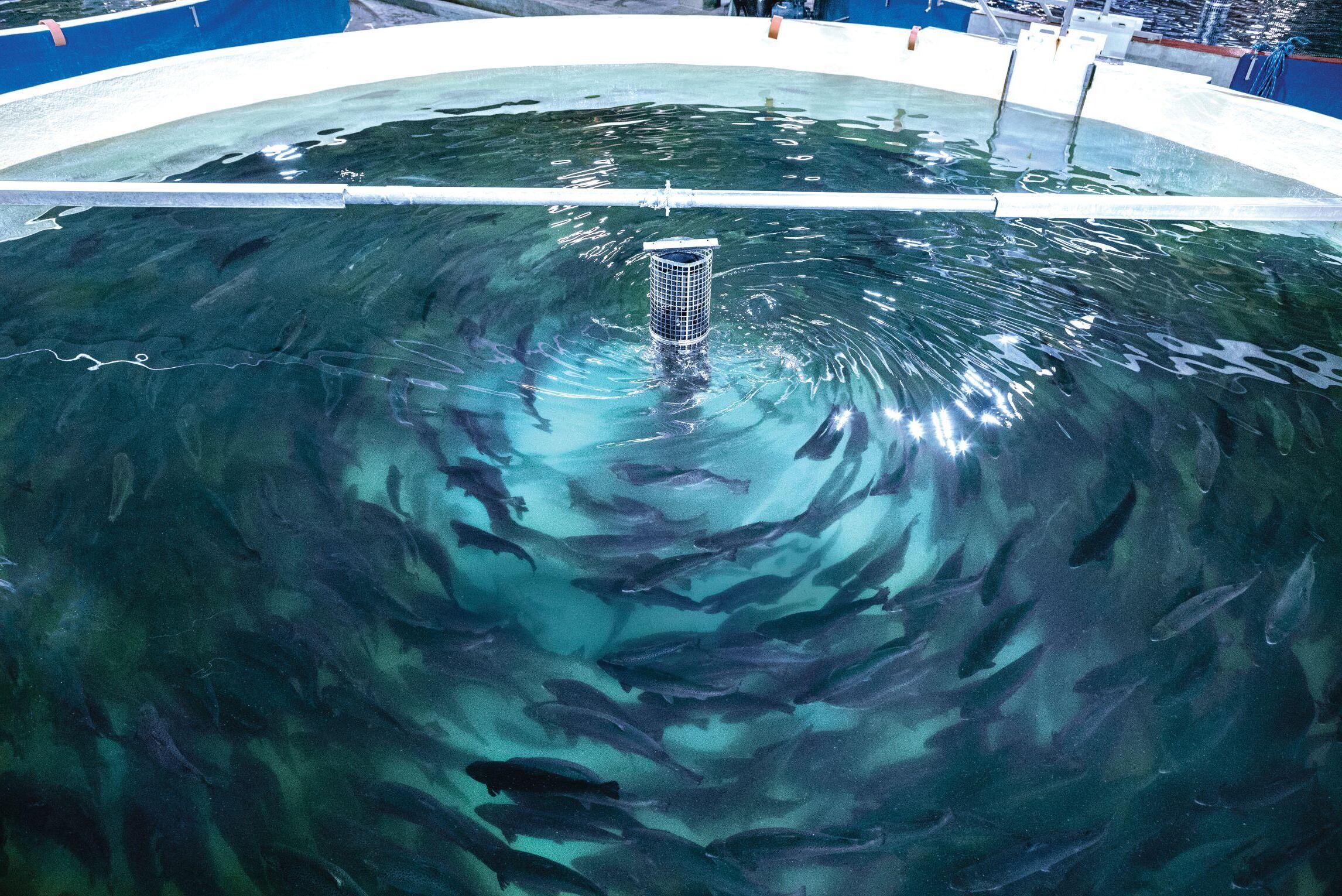

In aquaculture systems, fish are typically stocked at high densities. Activities associated with harvest, such as crowding and transport to the processing plant can result in stress from increased physical activity, according to the researchers.

Stress can cause fish metabolism to be anaerobic. This leads to a faster depletion in pH and early rigor mortis. This can cause problems because fish filleting can only be done when fish are in their pre- or post-rigor condition.

Early rigor mortis also results in more ruptures to muscle tissues that

could lead to gaping, changes in flesh colour, reduced juiciness and softness. Early rigor mortis also reduces fish flesh capacity to hold water. This in turn, reduces shelf life of the product.

The shorter resting times (zero and two hours, more stressed fish) resulted in a faster establishment of rigor mortis, the study found.

Fish subjected to four and eight hours of rest entered rigor mortis 3.5 hours after slaughter and these animals had muscle pH different in the measurement performed three hours after slaughter.

“The resting time of four to eight hours is effective to reestablish homeostasis after transporting surubim, which provides fillets with higher quality and greater length of the pre-rigor mortis period,” the study concluded.

- NESTOR ARELLANO

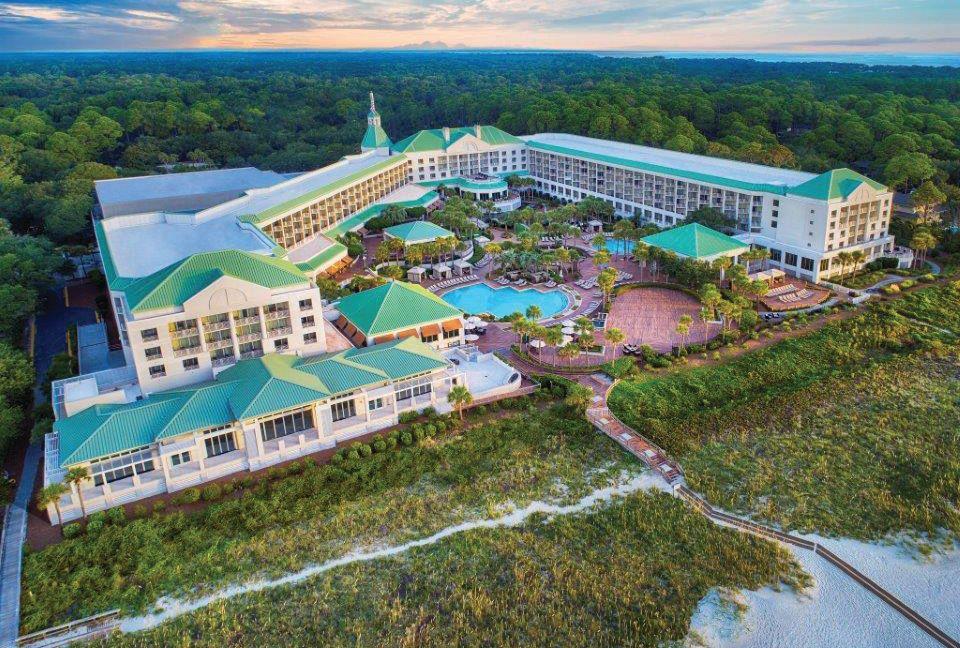

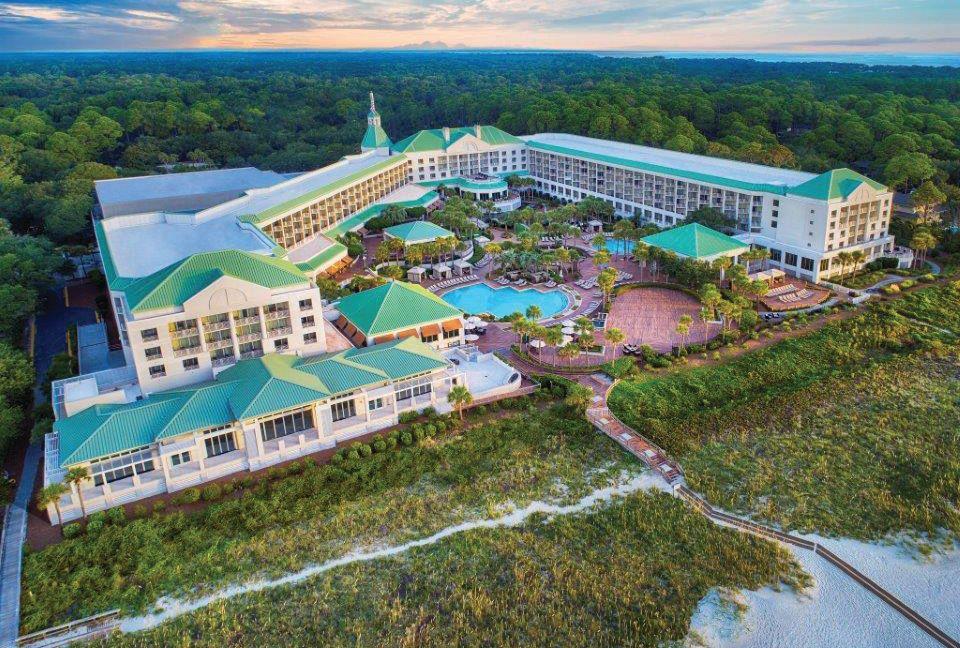

Atlantic Sapphire made its first commercial harvest of its RAS-grown Atlantic salmon from Bluehouse farm in Florida on Sept. 28, marking a major milestone for the company.

In the weeks following the first harvest, Atlantic Sapphire will increase weekly volumes, the company said, expanding its geographical footprint through its distribution partners Giant Eagle, H-E-B, New Seasons Market, Publix, Safeway, Sobeys, Sprouts Farmers Market and Wegmans.

“We knew we had the potential to have an enormous impact on the salmon industry, and with much of the seafood imported into the United States, we wanted to continue to make a positive contribution by seeking out a location that would reduce the carbon footprint of salmon available in the North American market. Today we’re proud to finally start serving Americans delicious Bluehouse Salmon with a quality and freshness they have not experienced before,” Johan Andreassen, Atlantic Sapphire’s CEO, said at the time of the momentous harvest event.

The Chef’s Warehouse, a purveyor of high-quality artisan ingredients for chefs, will be among the first partners to receive the premium Bluehouse Salmon product, according to Atlantic Sapphire.

“The sustainability model, coupled with domestic production, makes this a no brainer for our chef customers,” a statement from the Cheg’s Warehouse said. “Within 48 hours from harvest, we will provide the foodservice community

the freshest and incredibly clean tasting salmon that compares to no other.”

Atlantic Sapphire’s first Bluehouse harvest is an important milestone in the company’s 10-year vision of bringing sustainably-grown Atlantic salmon to the North American market. The first batch of salmon eggs were delivered to the Miami facility in November 2018 and have since been growing there amid ongoing construction of phase one of Atlantic Sapphires’s 80-acre land-based aquaculture facility project. The company expects completion of phase one by the end of the year.

Growing salmon while construction

crews work in the background was not without its challenges, however. In July, Atlantic Sapphire reported it was forced to do an emergency harvest of about 400 tons of fish at one of its grow-out systems. They cited the possibility that “disruptive construction noise and severe vibrations” had stressed out the fish. Upon completion of its phase one build, the salmon producer expects an annual harvest of around 10,000 tons of Atlantic salmon. The company has also secured the key U.S. water permits to produce up to 90,000 tons onsite, and has a targeted harvest volume by 2031 of 220,000 tons.

On sustainability

George Chamberlain, Global Aquaculture Alliance:

“Social responsibility, environmental responsibility and animal health and welfare are all critical. Without those, we simply won’t get market acceptance.”

On system design

Neder Snir, AquaMaof:

“It’s fundamentally important to begin with identifying any potential hazards in any site and biosecurity engineering needs to be a high priority whenever we start designing any kind of system anywhere.”

On feed formulation in RAS Huy Tran, Aquatic Equipment and Design:

“The RAS industry is pretty integrated with the feed industry. Is there room to grow? Absolutely. As our species expand and as our systems change, there are definitely places where feed production can meet up with RAS more.”

On public awareness

James MacKnight, Ideal Fish:

“As a community, we have a tremendous responsibility to education. And that’s a big job. And it comes down to, we need to collaborate more as a community to get that message out.”

On production planning Gregory Beckman, Innovasea:

“One of the things that’s really overlooked in production planning is fish handling. Fish handling aspects is a key ingredient in the design upfront.”

If there is one thing the global pandemic has taught the big RAS producers, it’s the ability to watch market trends and shift strategies to adapt and take advantage of those changing trends.

This was a key insight from the big four RAS players participating in a panel discussion at the recent RAStech Virtual Summit. The speakers – Erik Heim, president of Nordic Aquafarms, Martin Fothergill, board director at Pure Salmon, Ohad Maiman, founder and CEO of The Kingfish Company, and Thue Holm, chief technology officer and co-founder at Atlantic Sapphire – shared their insights on how COVID-19 has changed the trajectory of this emerging RAS sector.

Channel diversification has been one of the key learnings from COVID-19, and shifted priorities for producers.

“When we started the year we intended to focus more on restaurants and slowly develop retail, but (with COVID-19) we had to refocus into retail as restaurants shut down,” said Maiman. The Kingfish Company is based in The Netherlands and produces Dutch Yellowtail. The company has unveiled its expansion plans to build a RAS production facility in the U.S.

The increasing trend in home cooking – also a consequence of pandemic-related lockdowns – is also providing new market opportunities for aquaculture producers.

Pure Salmon’s Fothergill said his company plans to focus on this as well as on the shift in consumer behaviour toward online purchasing to see how the opportunity can be exploited. “Changes that we were expecting to see over three to four years happened in three to four months with that huge shift online.”

The pandemic also highlighted the importance of local food security, said Heim. Nordic Aquafarms recently launched a public information campaign about landbased aquaculture and sustainable food production. During the panel, Heim stressed the importance of informing consumers and correcting the misinfor-

mation.

“As we all take turns on (providing public education), we all will benefit from raising awareness around where this industry is going, given the great potential in the U.S. in the years to come,” Heim said.

Fish welfare was also top of mind among attendees of the RAS Virtual Summit, highlighting the importance of ensuring that the health and wellness of fish in landbased closed containment systems is an important consideration in technology design and operations.

“Fish welfare is something that we have been looking at for a lot of years in looking at the fish,” said Atlantic Sapphire’s Holm, explaining that the key is having good water parameters.

“As long as you can keep good CO2 and good water exchange at the tank with a lot of flow and the fish have good swimming speeds, have low ammonia, low CO2, good oxygen in the tanks, few particles, few bacteria, clear water then there is actually no problem for the salmon to be in those densities,” Holm said, adding that the fish they’ve harvested show no sign of stress and have “beautiful bodies.”

Atlantic Sapphire made its first full commercial harvest in late September from its Bluehouse RAS facility in Florida. The Bluehouse facility itself is in the final stages of construction and is expected to be completed by end of 2020, according to Sapphire’s recent reporting.

- MARI-LEN DE GUZMAN

RAS technology offers exciting new opportunities for the aquaculture industry. But with so few real-world examples of these systems, there are still many unanswered questions about the business case of largescale RAS. Aquaculture economist, Dr. Carole Engle, shared her insights during in a Q&A session at the RAS Virtual Summit on Sept. 16. Below are some highlights from the exchange. The full video can be found at rastechmagazine.com.

Question: What are the main considerations for a business entering the RAS space?

Carole Engle: We finished a study recently where we compare key cost drivers across a variety of production systems. Economies of scale are real in RAS where capital investment is quite intensive and quite strong. We’ve known this for many years. But what did jump out to me in this analysis is that the more established aquaculture sectors in the United States – like catfish production in ponds and trout production in raceways –make far more efficient use in labor and capital, in terms of cost per pound in fish produces than RAS do.

At a time when global supply chains are disrupted, RAS pioneers are taking advantage of the temporary spotlight to cultivate its local market.

“RAS farming really allows us to produce closer to the consumer and so you’ve got a much more attractive carbon footprint,” said Syvia Wulf, AquaBounty Technologies CEO. “And as we’ve all seen during COVID, our supply chains are fragile. And so domestic production is going to become increasingly important.”

Wulf joined fellow RAS producers at the RAS Virtual Summit. Brian Vinci, director of the Freshwater Institute, moderated the discussion, which also included Joe Card-

And so one of those other considerations that I would throw out is to pay equally close attention to efficiency metrics of labor and capital and not just economies of scale.

Question: What are the most important cost factors involved in a RAS project?

Engle: Feed is a major cost, so it’s important to manage a system that keep a low-feed conversion ratio, which is possible in RAS due to climate controls. Capital cost is also very high. If it’s borrowed money from a bank, then you’re paying an interest rate. But if you get that capital from an investor, that investor’s going to want or need a return at some point. So capital needs to be used efficiently. Labor is also a major cost in RAS. Then after that, like most systems, it becomes an energy cost that are some of the greatest costs in a RAS system.

enas, CEO of Aquaco Farms; James MacKnight, general manager of Ideal Fish; and John Ng, president of Hudson Valley Fisheries. Panelists agreed a great advantage of a local RAS facility is how it encourages what Wulf called “rural rejuvenation.”

“I think one of the huge advantages of RAS is that we’re able to go into a run-down community and go into a warehouse that perhaps has not been occupied for several years, and to be able to go in there and refurbish that warehouse and consequently support the depressed community, as well,” said MacKnight.

Cardenas added that training and cultivating local talent is also a huge advantage of a local RAS facility.

“In the first stage (of development), we hired everybody internally and we hired

Question: What is your take on developing countries and potential RAS projects there.

Engle: Location decisions and what kind of aquaculture business is going to make sense is really quite site specific. I would urge people to step back a little bit and not just be locked into RAS.

It makes a lot of sense to be able to locate closer to some important market areas and if the appropriate business models can be put together, it makes a lot of sense. But not everywhere. Pond-based systems and raceway-based systems are very sustainable production systems in the U.S., the EU and elsewhere.

Question: What do you think the industry will and should look like in 10 years?

Engle: The overall aquaculture industry is going to grow around the world. There’s no doubt in my mind. I believe RAS is going to be amenable in raising some species on a farm-level, at a higher production level than we’ve seen before. But I also think we’re still going to have shellfish produced along our coast and around the world. And I also think we’re still going to have some species, like catfish being raised in ponds. I don’t see that disappearing and going away. And I don’t see trout production in raceway going away.

very early,” he said. “Everyone that’s on staff was probably hired six months to a year before their job really began... That got us working extremely well and we’re proud of the price points we’re able to do it at and be competitive.”

“The location for us was key in terms of marketing,” added Ng. “We wanted to leverage Hudson Valley’s reputation and brand. The proximity to market, of course, is a huge advantage, especially to invite some of our customers to the facility.”

Engaging the local community is a big part of building social trust. “When we’ve engaged with consumers what we’ve found was that when we dialogue about that in a very simple way, we get a 70 percent purchase intent for our salmon,” Wulf said.

- JEAN KO DIN

By Maddi Badiola

The world has changed. The year 2020 was supposed to be an incredible year, everyone had high expectations. But no one expected the ongoing sequence of events. Who imagined that we would be living this global pandemic?

Here, in the Basque Country in Spain –where being outside is our way of living, surrounded by family and friends, eating and drinking, socializing – it is hard to believe that our culture and our way of life would need to be modified. Did anyone ever imagine we would be drinking wine with a mask on or those “pintxos” (i.e. “tapas” in Basque) being covered by plastic wrapping? Nevertheless, from something bad there is always something positive that can emerge. In this regard, as a result of COVID-19, much of the human way of food consumption has changed – or reverted back – towards local production. And this is a good news.

Global aquaculture makes an important contribution to food security directly (by increasing food availability and accessibility) and indirectly (as a driver of economic development). But how does it contribute to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? How can this be mitigated?

Climate change and global warming, directly related to greenhouse emissions, are two of the biggest threats recognized by environmentalists, and by people looking for a sustainable lifestyle.

Clouds, water vapor, carbon dioxide and other atmospheric gases retain heat radiated by the earth. Excessive or elevated GHG will cause the planet’s temperature to increase. Such intensification, which happens naturally, is exacerbated by increases in concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from air pollution – especially from combustion of fossil fuels.

Carbon dioxide is the major greenhouse gas resulting from human activities and as such, the efforts to lessen carbon emissions

Maddi Badiola, PhD, is a RAS engineer and co-founder of HTH aquaMetrics llc, (www.HTHaqua.com) based in Getxo, Basque Country, Spain. Her specialty is energy conservation, lifecycle assessments and RAS global sustainability assessments. Email her at mbadiolamillate@gmail.com or contatct her through LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram.

through energy conservation, greater use of fossil fuels with lower carbon emissions, switching from fossil fuels to biofuels and development of alternative (i.e. solar, wind and water) energy resources are some of the initiatives that governments, companies and individuals are undertaking.

And what about transportation? It is relatively easy to put some solar panels on the roof of a company building. However, this does not make any sense if the product produced is going to travel halfway (or more) across the planet to reach its target market. In 2008, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) published a report to end energy use in the world food system, citing processing and distribution account for greater energy use among plant crops, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture, retail, preparation and cooking.

The question is: should we produce food closer to the market? The term “KM zero” or zero kilometre – referring to food produced near the consumers’ place of residence or at a maximum distance of 100km from it, to preserve freshness and quality – has been gaining market traction among more concious consumers. More and more companies are looking for products delivered on a daily basis. As such, some of the biggest and most important fish producers in the world are looking to add daily-delivered, fresh-farmed salmon to their product portfolio.

Aquaculture accounted for approximately 0.45 percent of global anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2013. This is similar in magnitude to the emissions from sheep production. However, such modest emissions reflect the low emissions intensity of aquaculture due largely to the absence of methane production, high fecundity and low feed conversion ratios of finfish and shellfish.

But aquaculture production is increasing rapidly, and emissions arising from postfarm activities (e.g. transportation, which is not included in the 0.45 percent calculation) could increase significantly with the emissions intensity of some supply chains.

A potential solution to solve such con-

cerns has a name, and it is recirculating aquaculture system (RAS): fish farming free of pollutants, antibiotics and disease, located near the markets.

RAS can be located anywhere and requires less land/space than any other aquaculture system. This is advantageous for the producer, providing them close proximity to the market or suppliers. This also translates to reduced CO2 footprint and transportation costs.

Would consumers want their product harvested on, say Monday, and be in their fridge by Friday? Or do they want to have fresh fish delivered to their homes? Maybe those two examples are the most extreme but both are possible. Consumers, as key players and the final link in the supply chain, need to choose. While portions of the world have been locked down, food producers have been working harder than ever and have become innovative in the way they deliver their products. I know of one company delivering RAS-farmed pompano directly to homes and restaurants, and the acceptance from the consumers has been very positive. With such in-person delivery, these customers got to know and trust the supplier, and in the end that is what we are looking for.

Locally produced, KM zero products are gaining space in supermarket shelves. Locally produced, daily delivered fish, may have previously been a luxury, but it’s possible to make this more mainstream.

Do not forget that, “farmed is the way, RAS is the technology.”

Want to know more about RAS sustainability, how the market is evolving and what are the latest innovations? Do not hesitate to contact me.

*Suggested reading: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) (2008). The state of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2008 (ISBN 978-92-5- 106029-2). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved April 4, 2016, from View Article.

By Carlos Alberto Espinal

The water recycling capacity of RAS is three orders of magnitude higher than that of flowthrough farms and at least an order of magnitude compared to partial re-use systems. Despite the significant savings in water, large facilities will still use and discharge significant amounts of water.

In commercial RAS, water usage is mainly directed towards dilution of nitrate, which

accumulates in the system as the nitrifying biofilters oxidize the ammonia excreted by the fish. Thus, the first logical step to increase recirculation rates in RAS is to remove nitrate, which is commonly done using denitrification bioreactors.

Denitrification – the conversion of nitrate to nitrogen gas – can be done through both heterotrophic and autotrophic organisms. Heterotrophic denitrification is more commonly utilized in RAS. Maintaining a

heterotrophic denitrification reactor requires the addition of a carbon donor (an energy source) for the bacteria to work. However, even the most affordable carbon sources, such as methanol, represent a significant operating expense.

This makes the idea of using sludge as a carbon source worth considering. The use of sludge for denitrification has been investigated over the last 20 years and continues to be a subject of research today.

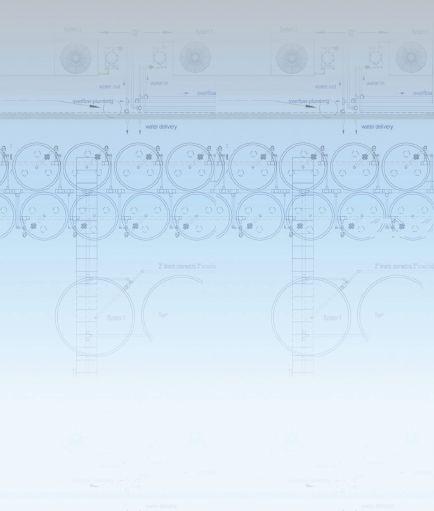

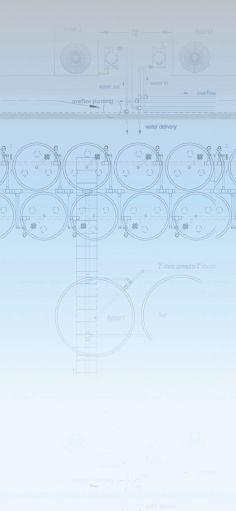

Landing Aquaculture recently conducted a pilot trial using a 1.2 cubic metre batchfed denitrification reactor in a 50 cubic metre semi-commercial RAS, installed at the greenhouse horticulture research station of Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

The RAS ran a 12-month tilapia growing cycle and supplied water for two lettuce growing cycles grown in a separate deep-water culture hydroponic system.

The trials were conducted to evaluate the denitrification performance of a batch-fed, up-flow denitrification reactor which uses a central airlift riser to maintain the sludge mixed and to prevent the formation of a scum layer, commonly found in similar designs such as the upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactors. Reactor performance in terms of single pass efficiency, volumetric nitrate removal rate and effects on the water quality of the RAS were recorded through the study period, which comprised several reactor shutdowns and restarts to adjust its performance.

With the reactor fully working by May 2020, we found that on every batch cycle, the nitrate concentration in the process water was reduced by 150-200 mg/L – about 50 percent concentration measured in the RAS water. The calculated volumetric removal rates for this reactor were 300-500mgNO3/lreactor/ day, similar to other single-sludge reactors reported in the literature.

In this reactor and under the operating conditions of the experiment, the denitrification reaction was limited by the availability of carbon. Part of the limited carbon availability was likely caused by the consumption of dissolved oxygen. Oxygen intrusion in this reactor mainly occurred via the process water.

The use of gas sparging in activated sludge reactors is a common technique to maintain the sludge properly mixed. Gas sparging is used in conventional water treatment, in membrane bioreactors and has also been used in UASB reactors. In a previous work by Müller-Belecke and collaborators in 2013, the nitrogen gas-rich off-gas has been recycled and diffused back into the vessel.

In this work, we designed an airlift which created bubble “slugs” instead of fine bubbles to maximize water circulation and minimize oxygen transfer. During gas sparging, DO concentrations in the reactor were kept below 0.2mg/l at all times. These concentrations were low enough for the reactor to resume denitrification rapidly, but high enough to interrupt it during the mixing cycle. Given the simplicity and cost-effectiveness of the solution, airlifts seem to be a low cost, simpler alternative to mechanical stirrers and gas recycling systems in single sludge reactors.

Although the removal of nitrate from the RAS process water was achieved, high degrees of recirculation without removing the solids produced in the system eventually led to blooms of heterotrophic bacteria, akin to what is experienced in biofloc systems. Fish welfare and growth performance remained unhampered. Increased oxygen consumption in the RAS and increased need for system maintenance suggest that sludge reactors must be operated either as end of pipe treatment devices or in combination with a comprehensive downstream solid capture and microbial control step. In this experience, the system’s microscreen drum filter was not efficient in controlling solids coming out of the reactor. The reactor’s effluent, relatively free from solids but highly bioactive, promoted the growth of biofilm slicks clogging the microscreens.

RAS and sludge reactors are highly biodiverse environments whose microbial communities are currently being discovered using metagenomic tools. However, there is a new way to look at RAS at the molecular level: metabolomics.

With metabolomics, we do not look at genes, RNA or proteins, but at thousands of small organic molecules that are produced by the organisms in the system. Collections of molecules can become a “fingerprint” which can be used as a baseline to study changes in behaviour and performance of a biofilter, an anaerobic reactor and perhaps, even the fish themselves. With lengthy analytical work, the metabolome can be surveyed for molecules with properties that could be applied to aquaculture.

To our knowledge, Landing Aquaculture in partnership with Wageningen University are the first to conduct a pilot study on the use of metabolomic approaches to study biofilters in RAS. In the sludge denitrification experiment, five replicate samples for metabolomic analysis were taken from four locations: the inlet and outlet of the nitrifying biofilter, the sludge sampling port of the denitrification and the denitrification reactor’s outlet. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) profiling was conducted on the samples. Principal component analysis was used to identify differences across and within sampling groups.

Although the analysis led to the identification of at least 3,000 potential compounds, the study focused on comparing the occurrence of these across the samples. Some interesting comparisons include:

Of the 3,000 compounds identified, 789 where only found in the denitrification reactor sludge blanket.

There were 692 compounds shared between the denitrification reactor and the nitrifying biofilter, but these would be twice as concentrated in the first.

There were 12 compou nds that were only found at the outlet of the biofilter.

There were 19 compounds that were unique to the nitrifying biofilter, but these were recorded twice the concentration at the outlet compared to the inlet.

A few compounds were putatively identified. Of them, proline – a known plant biostimulant – was found to be 20 times as concentrated in the denitrification reactor compared to the nitrifying biofilter.

Sludge in RAS, although a nuisance for most operations and a cause of H2S pro -

duction, seems to hold some properties which have not been fully exploited: humic acids having antiviral properties, biofloc systems reducing disease transmission, microbially mature water reducing opportunistic pathogen suppression, geosmin and MIB reduction and plant growth promoting effects are some of the potential benefits that have been investigated. However, there is still significant work to discover what molecules are involved in processes we observe.

Future work may lead to using metabolomics to control biological processes, to compare operating conditions within and across RAS farms and to find compounds of interest such as antibiotics, antifungals, insecticides, stress modulators and more. This research work was funded by the EU INNOSUP Horizons 2020 VIDA project.

Carlos Alberto Espinal is the managing director of Landing Aquaculture BV, based in the Netherlands.

By Lynn Fantom

In late September, Atlantic Sapphire harvested its first U.S.-raised Bluehouse salmon in what the company called “a groundbreaking moment” in its history. It could be considered the same for recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) overall.

This development marks a point when leading players in large-scale RAS have demonstrated they can raise capital, endure the tribulations of permitting, and manage construction, even during a global pandemic.

“RAS in the last few years has proven that it crossed the Rubicon from an experimental to a commercially viable technology,” Ohad Maiman, CEO of The Kingfish Company, points out in a panel discussion at the RAS Virtual Summit held last September. Like Atlantic Sapphire, which was founded in Norway and expanded to Florida, this Dutch start-up also has its sights across the Atlantic – but on Maine. In late September, it received a critical permit for its planned large RAS facility in Jonesport, Maine, producing up to 8,000 tons of Yellowtail.

There is no turning back for RAS now. What’s more, as Maiman’s reference to “crossing the Rubicon” suggests, this tech-

nology could be a disruption of historic proportion.

The phrase evokes Julius Caesar who defied the “old guard” by leading his troops across the Rubicon River, launching a fiveyear civil war fought around the globe. Caesar’s triumph earned him power and in-

fluence in the Roman Republic.

Will RAS defeat the naysayers? Will a single production technology dominate the landscape? Which geographies will yield the greatest rewards?

It is unclear at this point how this emerging industry will play out. What is known,

however, is that if RAS is to succeed, leadership matters.

There are many key decisions ahead. As the sage Dr. Carole Engle points out in a new book, RAS profitability may hinge as much on the productivity of both labour and capital as production scales. Economically viable businesses, she says, develop based on multiple decisions over time that lead to more efficient production practices.

There are many decisions ahead, and no going back on some.

As Atlantic Sapphire celebrated its first harvest, its eyes were clearly on the prize: satisfying the demand of a U.S. market hungry for salmon. The nation, which imports most of its salmon, currently consumes about 400,000 tons annually.

That’s why many of the land-based RAS

tons in Florida), Nordic Aquafarms (60,000 tons both in Maine and California), Whole Oceans (20,000 tons in Maine), AquaCon (15,000 tons in Maryland), Pure Salmon (20,000 tons in Virginia), and West Coast Salmon (15,000 tons in Nevada). It adds up to meeting most of the demand.

RAS is ready to compete for a large market like the U.S. because its operating costs are now in the same ballpark as those of net pen producers, according to analysts. This new financial dynamic comes as RAS costs have decreased with scale and the expenses of traditional operators have increased with efforts to combat disease and sea lice, as well as to obtain licences in Norway.

Market demand has also been growing, as the global population increases and health-conscious consumers opt for fish. But the growth in the supply of farmed Atlantic salmon has been falling. It sunk from

More than a dozen land-based RAS facilities are in the works for Norway – for grow-out, not smolt produc-tion. These plans buck the trend of locating large-scale RAS operations close to major markets and are reminders of Norway’s outsized role in global aqua-culture.

Although they may not be making headlines, such ventures can boast RAS expertise outranking many of the firmsthatdo.

For example, Havlandet Aquaculture, with 17 years raising cod smolt, has started construction on a pilot facility with capacity to grow out 30,000 tons of Atlantic salmon annually

The RAS venture Kobbevik og Furuholmen Oppdrett (KFO) is owned by the conglomerate Austevoll Seafood, which also owns Leroy Seafood. KFO’s 10,000-ton-capacity facility will be built in Fitjar,alsohometoLeroy’sSjotrollsmoltfarm,oneofthe largest in Norway

Such leaps from RAS smolt expertise to full growout capability beg the question: how will Norway’s traditional net pen leaders move next?

Theyhavebeengrowingsmoltsbiggerandbigger, after all. Production of post-smolts (250-1,000 grams) has become more common in recent years, accounting for 9.1 per cent of the individual smolts releasedin2019. That is accordingtoMowi’sSalmon Farming IndustryHandbook2020,whichalsonotes thatthemostfrequentlyharvestedweightinNorway is four to fivekilograms(GWT).

The driving force behind this practice is to increase overall salmon production by lowering the mortality that occurs at sea due to sea lice and disease.

Smolt production in RAS is not new, of course. Chile, with more limited freshwater resources than Norway,introducedindustrial-scaleRASfacilitiesfor smoltproduction.Infact,thefirstsuchplantwasbuilt in 2001 for Pesquera Camanchaca.

It is still too early to know if savvy and well-timed adoption of RAS for grow-out will ensure Norway’s ongoing dominance in salmon production.

Or the key may be a hybrid technology. Andfjord Salmon successfully attracted capital to begin construction of the world’s largest flow-through salmon farm. It combines “the best of both worlds,” as the company says: fresh, cold seawater (like net pens) andprotectionfromtherisksofsealice,algaeandfish escapes (like RAS).

For certain, Norway knows both worlds well.

according to the Mowi salmon farming handbook. Kontali expects growth to diminish further to four per cent from 2018 to 2022.

“The background for this trend is that the industry has reached a production level where biological boundaries are being pushed,” Mowi says. Improved pharmaceutical products and techniques such as wellboats are staying the tide, but RAS may provide the long-term answer.

As Maiman describes on his LinkedIn profile: “When capacity constraints force an established industry to go through a paradigm shift, the sea change can be significant – challenging traditional production methods, while providing unparalleled opportunity for innovative newcomers.”

Although RAS leaders share the same goals, their approaches are different.

Atlantic Sapphire, which began trading on the Oslo Stock Exchange in May, is targeting high production volume of 220,000 tons annually at a single facility. Located 15 miles from the coast and 40 miles from Miami, it can reach major U.S. markets within two days of trucking, the company says.

With the completion of the first phase of its Florida construction project expected at the end of 2020, the second phase of construction will commence in the second quarter of 2021. Gradual expansion from then on will continue through 2031.

“We basically can build as much capacity

as we want because permitting is not a limit. We see that as a huge advantage,” says Thue Holm, co-founder and chief technology officer, during the RAS Virtual Summit.

Sitting atop unique geology, Atlantic Sapphire boasts patented technology to access underground aquifers for fresh and salt water and a system of injection wells for discharge.

The company has been harvesting Atlantic salmon from a land-based, “proof of concept” facility in Denmark since 2011, building know-how as it goes. And it hasn’t all gone smoothly – for example, in March, Denmark lost a tankful of 227,000 fish due to high nitrogen levels. But, in Florida, some of the risks are mitigated by the plant’s 12 separate grow-out systems, and these independent systems will increase as the facility expands.

Like Atlantic Sapphire, Nordic Aquafarms piloted RAS in Denmark at its Sashimi Royal operation, which began harvesting Yellowtail kingfish in 2018. A second land-based farm in Fredrikstad, Norway, which started harvesting Atlantic salmon this year, is another notch in the company’s belt.

But, unlike Atlantic Sapphire’s approach with a mega-facility, Nordic Aquafarms has opted for separate U.S. facilities in Maine and California and, at this point in its development, emphasizes in-house engineering expertise.

Demonstrating the agility RAS leaders need, it acquired that skillset by acting quickly to hire six staff members from its RAS vendor – when it went bankrupt. That internal expertise is paying off.

“It takes out the risk related to vendor support and their capacity issues,” says president Erik Heim, who also participated in the RAS summit. Close, daily interaction among internal design, production, and engineering teams has allowed “a lot of pretty rapid iterations that otherwise may not have been so easy with a traditional vendor,” he adds.

But permits for its large-scale RAS operations in Maine and California have been significantly more challenging than what Atlantic Sapphire faced in Florida. Progress in Maine has also been held up by a lawsuit involving ownership of the intertidal zone which Nordic Aquafarms needs to run intake and outtake pipes.

The delays and headaches do not seem to ruffle the company, however. “I think this is part of the learning process and journey for every company going into (RAS),” says Heim. Nordic Aquafarms is backed by private investors, including the family office of Norwegian shipping magnate Einar Rasmussen.

For its part, the Kingfish Company launched with Yellowtail kingfish as its core species. “We often joke that we have borrowed a page from the Tesla playbook, where yellowtail is our Model S,” says Maiman.

This high-value species is the focus of its current facility in the Netherlands and will remain so in Maine at the new location, fewer than 100 miles east of Nordic Aquafarms. With production from both sites targeted at 20,000 tons, the sashimi-grade Yellowtail helps make the numbers work: a higher price point, still competitive with imports, will offset the higher costs of smaller RAS farms.

To fund four RAS projects under the umbrella of Pure Salmon, this year 8F Asset Management raised $360 million from “long-term strategic investors who really understand what we do,” says Martin Fothergill, co-founder and partner of the global asset management company. Headquartered in Singapore, 8F is a group of former Deutsche Bank executives which created Pure Salmon to realize its “impact investing” strategy.

8F is taking a cue from a risk managed portfolio approach as it aims for Pure Salmon to be a global player with a local footprint.

“Our analysis shows that the 10,000- to 20,000-ton production facility gives

enough economies of scale at the local level, but still represents a manageable construction project and farm and also doesn’t over-concentrate market risks,” says Fothergill at the RAS Virtual Summit.

With a “proof of concept” facility near Warsaw, Poland, that will double as a training facility, the company is planning salmon farms in France, Japan, and the U.S., all engineered using RAS from AquaMaof. Site work on the Japan facility has started, with the others in pre-construction. Together, this first-stage effort is targeted to yield over 40,000 tons during the next few years.

But 8F is already eyeing China. “It’s simply a market that can’t be ignored,” says Fothergill, noting China represents one-third of all global seafood consumption – seven times more than North America. “And we all know it›s already the

six largest salmon consumer in the world.” Pure Salmon plans to have five plants there, with total production of 100,000 tons.

There will be a total of 16 vertically integrated production and processing facilities to serve local markets around the world, with a total production target of 260,000 tons. He says the structure will not be unlike multinational firms which operate in multiple markets, with certain centralized functions – buying of feed, brand management, quality assurance, and training. This salmon empire will be managed by a team based in Abu Dhabi. Fothergill emphasizes how important the next five years will be for RAS to win its “rightful position” in the mainstream of salmon production.

Remember, it also took Julius Caesar five years to triumph.

Saravanan Subramanian is the global product and technical manager for RAS at Skretting. He is responsible for developing and delivering high performance fish feed and technical service to RAS customers.

Bernardo Sumares is a RAS technical specialist at Skretting. He is responsible for providing technical support to RAS customers and improving their farm performance and productivity.

Tahi Fu is a project manager and technical RAS specialist for Skretting. His responsibilities include developing services beyond feed and supporting RAS customers in Asia.

By Saravanan Subramanian, Bernardo Sumares and Tahi Fu

In salmon farming, there is an increasing trend to utilize recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). While some producers have integrated these systems into their broader operations to establish larger, more robust smolt for grow-out in sea cages, others are using them for the entire production cycle – from egg to harvest.

As these ventures have found, there are many advantages to RAS systems. At the forefront is their capability to provide tighter environment controls. By having stable production conditions, RAS provides the scope to promote consistent growth rates.

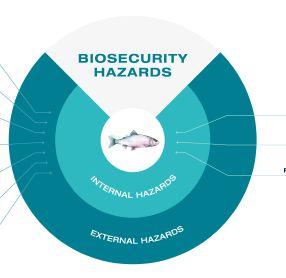

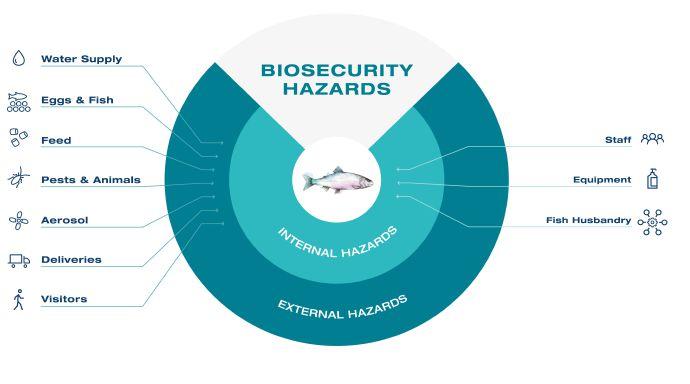

Operating any RAS facility is a demanding task, requiring specialist skills and experience. These systems face their own unique set of challenges, including a range of risks associated with water quality and biosecurity. To minimise fish stress and related susceptibility to disease, it is essential that stable conditions are maintained within the system and that robust biosecurity measures are implemented and followed.

One of the key advantages of RAS facilities is the physical barriers and control measures that they offer to protect fish from external, disease-causing pathogens. Nevertheless, pathogenic microbes can prevail in different forms in and around RAS farms, and given the right conditions, they can rapidly increase in number and spread. This in turn can lead to a disease outbreak situation, and eventually fish mortality – causing financial loss to farmers.

The most common pathogens found in RAS are protozoan parasites (e.g. Amoebas, Costia), fungi (e.g. Saprolegnia, Aphanomyces), bacteria (e.g. Vibrio, Aeromonas) and viruses (e.g. ISA, IPN).

Despite the physical separation from external hazards, RAS can still be very fragile if biosecurity measures are not implemented

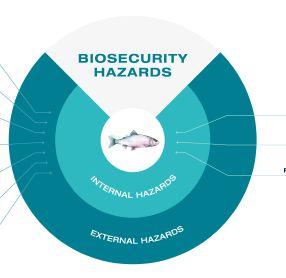

Biosecurity in RAS involves addressing internal and external risk hazards.

and strictly followed.

Hazards are divided in two main categories: external and internal. External hazards are transferred from the exterior into the RAS facility. Internal hazards are those that arise and spread within RAS facilities. Each hazard has a different means of entry, a distinctive rate of spread, and will carry its own level of risk.

Water is an essential element in any fish farm and the quality and safety of intake water varies depending on the source. Water can be supplied to the RAS facility from ground water like borewells or surface waters like rivers, lakes and fjords. Regardless of the source selected, water entering the production tanks must be free of particles (e.g. sand), pathogens and contaminants (e.g. copper, zinc and aluminium).

Groundwater sources are relatively safe, as they are pathogen-free, low in microbial and organic load compared to surface water sources. Therefore, more attention and measures are required for surface water supply. For contaminants, the risk is quite similar for ground and surface water supply source. Undesirable contaminant levels in surface water sources can be influenced by natural weathering, as well as industrial and

agricultural runoff.

One of the first lines of biosecurity begins at this point. Good mechanical filtration measurements are taken to mitigate particles. This is followed by ozone to mitigate microparticles, pathogens and contaminants. Then, UV measurements are taken to mitigate pathogens and remove any excess of ozone in the water.

To reduce the risk of breakdown and to maintain equipment efficiency, it is important to carefully follow the manufacturer’s instructions with regard to the correct contact time and dose in UV and ozone units. Weekly maintenance and daily check-ups should be in place and key components such as UV lamps should be replaced before reaching the end of their expected life.

In case of unexpected failures, it is advisable to keep backups of key components in stock for replacement and to have standby units for emergency use.

As a biosecurity traceability procedure, monthly water samples should be taken before and after treatment to check effective functionality. Monitor contaminant levels in the supply water on a yearly basis.

A regular year-round supply of eggs and fish is a prerequisite in RAS, which involves

meticulous logistics planning to obtain high-quality and pathogen-free supplies.

Allowing eggs or fish carrying pathogens into a RAS facility can have a huge operational risk and financial impact. The production plan will be disrupted, the entire infected rearing unit will have to be cleaned and thoroughly disinfected, and the fish will have to be culled. In a worst case scenario, pathogens will spread to other rearing units. Any stop in RAS operations due to a biosecurity breach will lead to a substantial delay and loss of fish production.

Most local authorities request a health certificate from egg and fish suppliers to mitigate spread of infectious diseases. Suppliers have to be quality assured, requiring screening for infectious pathogens. This procedure must be conducted prior to shipment to the buyer.

It is advisable to request a disinfection certificate for the eggs and transporting system. Eggs should again be disinfected upon arrival and fish should be stocked in quarantine units. The quarantine period varies and depends of several factors, but as a general rule, four weeks is advisable.

Before stocking animals, experienced technicians or veterinarians should conduct an assessment to evaluate stock quality and any underlying health issues post-transport. A good welfare recording system should be in place. Traceability is an important tool in case a disease outbreak arises.

Visitors can be common to RAS facilities and will be present for a variety of reasons. However, such visitors can unintentionally carry and spread pathogens that are infectious to fish and also to facility staff.

Different approaches can minimize these risks. For instance, any new arrival to the facility needs to be informed about its biosecurity rules. They should also complete a visitor form, confirming that they have not been exposed to any potential risks or been on sick leave in the past 14 days. Most facilities further suggest a 48-hour quarantine period after visiting other fish farms or places posing a biosecurity risk.

Physical barriers separating visitors from production areas are also effective. However, they are expensive and need to be planned

in the initial building phase. Simple physical barriers can be implemented with lower costs, such as separating unit entrances and creating changing areas. These areas should be equipped with footbaths, hand disinfection stations and a changing room.

Before entering the RAS, visitors should change into fresh overalls and footwear. They must also clean and disinfect their hands, and avoid any direct contact with the production process. In the case of sampling, staff should provide support to avoid unnecessary risks.

Feed-related risks can be linked to microbial and physical quality. Nutrient-rich feeds offer the means for pathogens to develop and spread, depending on the storage conditions. However, the microbial risk of feed origin is minimal. The risks linked to the physical quality of feeds is important and have indirect effects due to nutrient leaching, as well as the disintegration and behaviour of feed in water.

Today’s commercial fish feed production technologies, like extrusion, expose feed

There is more to RAS aquaculture than the RAS itself: A proven fast delivery concept. NEWS:

Alpha Aqua A/S builds the full production unit at the factory site to ship it as one delivery. Installed on a standard flat concrete slab offering a variety of advantages for the customer:

Pre-test by FAT (Factory Acceptance Test)

Adaptable to existing buildings or dedicated ones

Faster construction - no fixed concrete structures implying better Return on Investment (ROI)

Floor mounted tank system – no underground pipes or specific concrete foundations in the system

High flexibility to adapt to the market changes

Want to know more? Please

materials to high temperatures and pressure that neutralize pathogens.

Biosecurity measures are extremely important to reduce indirect risks due to feed physical quality. At delivery, all feeds should be inspected. A sample should be taken, labelled and frozen for future analysis (if required). In the sample, it is important to analyze dust, breakage and oil leakage. Keep a good recording system in place, to ensure traceability if any problems do arise.

Feed should be stored appropriately in a cold and fresh room or silo, and when smaller feed types are opened, they should be properly closed to avoid deterioration or contamination.

Feeding systems should be checked and maintained on a weekly basis. A feed sample should be taken when reaching the end of the feeding line to analyse dust and breakage. Small particles of feed released into the water can lead to serious consequences. Any feed accumulation or mould should be immediately cleaned, especially in feeding systems to avoid spreading to other feeds.

Deliveries are part of RAS facility operations and traffic can occasionally be high. Pathogens can also enter the facility through deliveries and these can rapidly spread if no biosecurity measures are in place. It is recommended to establish a delivery area and a place where relevant goods can be disinfected and placed in quarantine.

Disinfection logs from the carrier should be requested to ensure there are no risks from previous cargo, stating the type of chemical used and completed date.

Always ensure that goods are from certified sources, especially those products that will be directly used in the system. Never use equipment that has been in other facilities,

even disinfected, as the risk is too high.

Aerosols are small suspended particles in the air, like dust, that can gradually accumulate and settle on surfaces. Airborne particles can also carry pathogens into the facility through the ventilation systems.

Because it is difficult to trace, this external hazard is not commonly mentioned as a problem in RAS operations. It is recommended to have a filtration system to minimise the entry of particles, and when possible, ventilation systems should be installed specifically in each unit.

Wherever possible, ventilation outlets and fans should be placed away from tanks, equipment and sump areas where aerosol and droplets can easily come into contact with the water in the system. Monthly visual inspection of ventilation systems is recommended and filters should be changed frequently.

RAS facilities are less exposed to pests and animals than traditional fish farms. However, they still offer stable temperatures, food and safety from predators, thereby creating the perfect environment for potential pests like insects, rodents and scavenger birds.

These pests and animals are external hazards that could carry pathogens into the facility. Some could stress the fish which eventually can lead to welfare and health issues. Other related biosecurity risks include damage to feed bags and electrical systems.

A certified pest control company should assess the control of pests and animals. Staff should be pro-active about removing and cleaning any feed spills immediately, and ensuring that the facility is tidy, organised

and free of accumulated waste or materials.

Staff are the most important element in RAS operations. They are responsible for implementing and following biosecurity protocols while also ensuring risks are avoided.

There is a high risk of pathogens spreading through the facility via staff members due to their daily activities and direct contact with fish and systems. Team members should be sufficiently skilled to perform any type of operation in the facility, but it is important that the team has a specific production unit or a specific batch of fish to follow, as this reduces cross-contamination risks.

Staff discipline is essential. Good hygiene and specific working clothes are important measures. Keep footbath stations cleaned and refilled with active disinfectants. Disinfectants can lose their efficiency fast depending on usage, so ensure they are replaced regularly. Solution guide tables can be displayed at the relevant area as a reminder.

Good awareness training and culture is also important. In the event of disease outbreak, maintain different staff shifts to avoid cross-contamination.

Good equipment and tools are key for smoother, more efficient operations. They also boost team morale, save time and contribute to biosecurity.

A huge risk of cross-contamination is associated with the use of equipment between operational tasks and units. In particular, this can occur when using equipment from grower production units in hatchery units, in which fish are more susceptible and fragile.

Good biosecurity practices involve the cleaning and disinfection of all types of

Good circulation is decisive for profitable aquaculture. Do you want unequalled operational reliability, energy savings, and operating efficiency many years ahead?

Specialists in corrosionresistant propeller pumps, closely adapted to the needs of the individual customer.

www.lykkegaard-as.com

equipment after use – removing fish mucus, scales and organic material clinging to the equipment. If not thoroughly cleaned, theybecome susceptible to bacterial growth, causing bad odor and a potential source for disease outbreaks.

Disinfectant residues on equipment have to be rinsed before use. In some cases and the material allows, disinfected tools should be left to air-dry until next use. Procedures can differ from manufacturer, type of product and concentration used but as a general rule, a disinfectant should be in contact at least 10-20 minutes before removal. Every surface should be physically cleaned to remove as much organic material as possible before disinfection.

Another good practice is the use of color codes in operations. This simple and effective method can be applied to all types of operations – from the removal of dead fish to feed preparation. This brings a range of benefits: minimising cross-contamination, improving hazard awareness, and providing quicker access to the required equipment.

Bio-accumulation and mortalities in the RAS system promote the development of organisms like pathogens, increasing the risk of diseases outbreaks. By keeping a healthy system, the chances of pathogens growing and spreading are highly reduced. When faeces and uneaten feed are not effectively removed from the RAS system, bio-accumulation is expected. It is important to have good fish husbandry routines implemented to ensure active removal. Biofilm removal from the tank walls and sump areas should be monitored and cleaned. Deposits of uneaten feed and organic matter should be cleaned and syphoned if required.

Other associated risks include the removal of mortalities from the system. This activity should be taken with extra precautions, and it is advisable to use specific equipment, designate specific areas to classify fish mortalities, and use disposable gloves. The disposal of dead fish should follow local regulations and be collected by a certified company.

Designated specific areas, floors, walkways and all type of surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected after each operation. Biosecurity measures prevent and mini-

mise the spread of pathogens. Any neglect or breach in biosecurity measures can result in a disease outbreak, which can in turn, require extra labour during operations. It could also affect the RAS facility’s reputation and lead to welfare authorities deciding to restrict production expansion plans, with significant monetary implications.

It is important to develop and implement a strict biosecurity plan alongside your team and to involve different areas of expertise to guarantee that the details are not forgotten. Review and test the plan to ensure all measures are in place. Ensure your team has good biosecurity awareness, as they are the key factor to implement and follow the measures. Use infographics within your facility, they are a powerful tool reminding everyone about the importance of biosecurity. Specific biosecurity training should also be provided with annual reviews.

Essentially, biosecurity starts long before entering the RAS facility. It is important to create a culture of biosecurity awareness throughout your facility to ensure that everyone knows the risks and consequences.

Known for its line of underwater ROVs, Deep Trekker presents an underwater camera for RAS facilities.

The DTPod Underwater Camera is a portable, durable and easy to operate machine that is designed to withstand lengthy installations and 360-degree inspections underwater.

Its 360-degree pan and tilt camera is ideal for monitoring fish health, feeding

Amiad’s Mini Sigma filter is the newest addition to the Sigma water filtration product line.

Its small and lightweight structure makes it easy to install, simple to operate and requires minimal maintenance. The Mini Sigma filter was developed for low-pressure operation with a capacity of up to 80 cubic metres per hour or 352 gallons per minute.

Raw water enters through the filter’s inlet and passes through a pleated coarse screen that is designed with a larger screen area, in order to increase the filter’s capability to handle high dirt loads. The water then flows through to an inner fine screen which catches the remaining smaller particles.

time or submerged infrastructure. It includes a splash proof controller which allows access to a fleet of installed cameras without having to maneuver large, bulky equipment or risk having a laptop close to the water.

The DTPod camera features a standard 1920 x 1080 HD resolution that works well in low-light environments. It also features a self-cleaning lens feature on

www.deeptrekker.com

The self-cleaning cycle is triggered using Amiad’s ADI-P controller. It interacts with Amiad’s app that provides detailed filtration performance data to your mobile device, such as DP and flush cycle counters, low/high pressure alerts, low battery alerts, and performance history data.

The self-cleaning cycle can be programmed to initiate by signal from the DP switch (pre-set at 7 psi), by time interval, manual start or by flushing duration. All these settings can be programmed through the ADI-P controller and app. www.amiad.com

PR Aqua ULC is the new Canadian distributor for Atlantium Technologies’ ultraviolet technology.

The Hydro-Uptic UV system inactivates viruses and pathogens that could be found in water. It is based on medium-pressure lamps which are designed with an optical amplification mechanism that recycles UV photons within a quartz-made disinfection chamber. This makes them more power-efficient than most low-pressure systems.

“We are excited about this opportunity to represent Atlantium UV in North America where we have a long and successful history providing systems design and high-quality equipment to aquaculture customers,” said Ian Race, product and sales manager for PR Aqua.

PR Aqua is an aquaculture design and technology provider based in Nanaimo, B.C. in Canada. Its latest partnership with Atlantium, based in Beit-Shemesh, Israel, will bring its globally-recognized UV disenfection technology to Canadian aquaculture farms. www.praqua.com

Adsorptech Pg. 27

Advanced Aquacultural Technologies Inc. Pg. 18

Aquacare Environment Inc. Pg. 16

Aqua Logic Inc. Pg. 23

AquaMaof Aquaculture Technologies, Ltd. Pg. 2

Aquatic Enterprises, Inc. Pg. 29

Aquatic Equipment & Design Inc. Pg. 28

Benchmark Instrumentation & Analytical Services Pg. 5

Biomar A/ S Pg. 6

CM Aqua Technologies Pg. 25

Cornell Universit Pg. 27

DrTim’s Aquatics, LLC. Pg. 15

Faivre Sarl Pg. 9

Feeding Systems SL Pg. 21

Fresh By Design Pg. 10

RASTECH Pg. 31

HTH aquaMetrics LLC Pg.25

IBIS Group Inc. Pg. 29

Integrated Aqua Systems Inc. Pg.11

Lykkegaard A/S Pg. 26

Only Alpha Pool Products Pg. 32

OxyGuard International Pg. 20

PR Aqua, ULC Pg.10

Pure Aquatics Pg. 28

Reed Mariculture Inc. Pg. 22

Reef Industries, Inc. Pg. 19

RK2 Systems Inc. Pg.19

Silk Stevens Pg. 29

Stofnfiskur h.f Pg. 7

Tongxiang Small Boss Special Plastic Products Ltd. Pg. 17

ULTRAAQUA A/S Pg. 8

Customized for your fish farm, hatchery or research operation! Our Commercial LSS Packages are custom engineered to meet your specific needs.

• Marine and Freshwater

• Mechanical filtration

• Chemical filtration

• Ultraviolet disinfection

• NEMA enclosed controls

• Bio-filter towers

• De-gassing towers

• Wide variety of flow rates

• Flow control valves

• Protein skimmers

• Variable frequency-drive pumps

• Temperature management All our systems are pre-plumbed and fully water tested prior to shipping.

Even the most well-maintained and managed RAS will have deviations from normal operating conditions. A robust system design that includes back-up and emergency life support equipment can mitigate risks. However, alarming features that quickly alert staff to a potential issue are critical to return a RAS to normal operating conditions as quickly as possible. Ideally, alarms will be few and far between at a well-managed farm. Because of this, alarming equipment should be regularly tested to confirm proper working order.