By Peter Chettleburgh

Welcome to RAStech, a special publication devoted to the advancement of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS). This publication is distributed as a supplement to readers of Hatchery International and Aquaculture North America . We’re confident that the magazine will land in the hands of appreciative operators and would-be operators of RAS facilities around the world.

As most fish farmers know, RAS is expanding rapidly, with existing and new installations on every continent (Antarctica excepted) and many countries. The need to conserve water and provide a safe, nurturing environment for a variety of fish species make this quickly evolving technology both desirable and practical.

However, while RAS technology has improved significantly over the past two decades, it still has a long way to go before it can claim a dominant position in the aquaculture sector. And this is where RAStech fits in.

Our aim is provide a forum for specialists in the field to disseminate their knowledge to both new and not-so-new practitioners of the RASman’s art. We aim to appeal to all people in the field; producers in particular, but also research scientists, engineers, investors as well as equipment manufacturers and suppliers. RAStech also aims to provide a platform for manufacturers and suppliers to market their products directly to potential buyers of RAS equipment.

The publication will carry a range of articles about RAS. Using low-tech language to discuss high-tech equipment, RAStech aims to be helpful for both the practicing farmer and the dedicated research scientist.

Let us know your thoughts, your ideas and your suggestions for improvement and how Rastech can support and contribute to this growing industry, now and in the future.

Here’s something to keep in mind when planning for conferences and tradeshows next year. RAStech – the magazine – will be launching a conference and trade show focused exclusively on the development and advancement of recirculating aquaculture systems.

With a range of sessions covering both marine and freshwater RAS, the event promises to provide a wealth of valuable technical (and biological) information for individuals and companies using the systems.

Accompanying the conference will be a RAS-focused trade show with exhibitors from around the world showcasing the latest in RAS hardware and systems.

The event is scheduled to take place next May (2019) and will be located on the eastern seaboard of North America. At press time the exact date and location was being finalized and will be announced in upcoming issues of Hatchery International and Aquaculture North America.

www.hatcheryinternational.com

Editor Peter Chettleburgh

Advertising Manager

Jeremy Thain 250-474-3982 jthain@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator Kathryn Nyenhuis 416-510-6753 knyenhuis@annexbusinessmedia.com

Circulation Manager

Barbara Adelt 416-442-5600 ext 3546 amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Ted Markle tmarkle@annexbusinessmedia.com

President & CEO Mike Fredericks

Printed in Canada

SUBSCRIPTION

RAStech is published as a supplement to Hatchery International and Aquaculture North America.

CIRCULATION

email: blao@annexbusinesmedia.com

Tel: 416.442-5600 ext 3552

Fax: 416.510.6875 (main) 416.442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Occasionally, RAStech will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office

privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800.668.2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2018 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

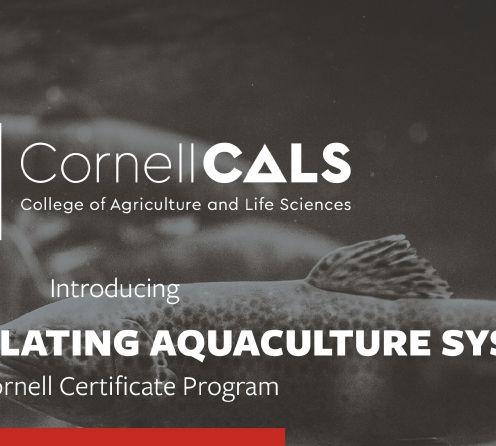

Recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS) are becoming increasingly popular for a range of fish species, including salmon.

Today, companies in all of the world’s main production regions are looking to extend the use of RAS beyond the hatchery and early life stages to cover entire production cycles. Following this trend, Skretting Aquaculture Research Centre Lerang Research Station in Norway has significantly increased its research capacity over the past year to investigating the process of recirculation and developing feeds specific that are optimal for these systems.

From this research emerged RecircReady, our innovative feed range for RAS. Using specialized feed components, RecircReady increases water stability and particle size distribution of faeces, thereby improving filtration efficiency and fish welfare. These diets are available for hatchery and land-based production systems.

Grenada is offering citizenship to individuals who will invest in its $39 million-Grenada Sustainable Aquaculture (GSA) shrimp RAS project. This Citizenship By Investment program has a developer buy-back option. With an economy that is tourism-centered, the government is pinning hopes on the Sustainable Aquaculture Project to diversify its economy.

The RAS production will initially start with Pacific white shrimp, (Litopenaeus vannamie), but may further diversify into other species in the future, according to its website. “RAS will be combined with integrated multi-trophic aquaculture and good husbandry practices to produce premium quality product while avoiding the resource conflicts and any measureable environmental impacts,” GSA said. — RUBY GONZALEZ

Salmo Terra plans to build one of Northern Europe’s largest RAS units in Øygarden, just outside Bergen in Norway.

From smolt to maturity, having total control of the full production cycle will enable Salmo Terra to maintain an optimal environment “where our fish can thrive,” the company said. “It also means that we can implement the highest standards, with no discharge to the surrounding sea.”

Salmo Terra plans to build six production units with construction set to begin within the year. Salmon production will begin in 2019. Initial annual production has been set at 2,670 tons and a maximum output of 8,000 tons. — RUBY GONZALEZ

Professor Olav Vadstein, of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and a team of scientists are investigating the benefits of good bacteria in RAS systems to fish health and profitability.

Don’t push too hard and don’t just blame technology when problems arise.

These are two straight-talking pieces of advice from RAS specialist, Jacob Bregnballe, sales director at AKVA Group and author of Guide to Recirculation Aquaculture.

By 2030, up to 40% of total global aquaculture output could be coming from RAS facilities, according to Luxe Research. Europe will emerge as a large-scale RAS adopter as demand for high-value species like sea bass and salmon continues to rise.

“As a general rule, you should never try to push things too hard when putting fish into a new production process, such as RAS,” Bregnballe told Hatchery International. “It’s also important for famers to avoid the all-too-common problem of ‘wishful thinking’ about what can be achieved.

“The best producers tend to be realistic when making production and technology decisions while always remembering that they’re dealing with a living species which they’re attempting to raise under an often complex biological process.”

Bregnballe added that it’s often better to move carefully and get it

right, than rush into a wrong decision.

“Even if you don’t actually kill the stock through some technology or management mistake,” he said, “you will probably be exposing them to adverse farming conditions , such as giving the fish under your care too high a level of nitrates or too little oxygen.”

Another common mistake farmers make, he said, is trying to produce too much from their unit, especially if the system has cost a significant amount of money.

Bregnballe is impressed with the rate of progress made by RAS-based technology over the last eight years, especially in relation to the salmon sector.

“It would be good to see similar progress being made in relation to other species, of course, but for that to happen we need to see more consistency of development being applied across the marine fish sector,” he said.

Find the latest RAS-related news, features and analysis from across the world . www.hatcheryinternational.com

• Greater

•

• More premium Quality Fish

• Higher Production Rates

• Remote Diagnostics andMonitoring

• Years of Operational Success

• Output Oxygen Levels of 92% ±2%

• 75% Turndown Ratio

• Lower Operating Cost with VSA Technology

By Justin Henry

Justin Henry is the former general manager of Northern Divine Aquafarms, a sturgeon and salmon RAS in British Columbia, Canada. He now heads up Henry Aquaculture Consult Inc, an international advisory and consulting service for the aquaculture industry. He can be reached at jhenry@aquacultureconsult.com

Iremember when “organic” was just a basket full of spotted apples in the corner of the produce section. It’s not that anymore.

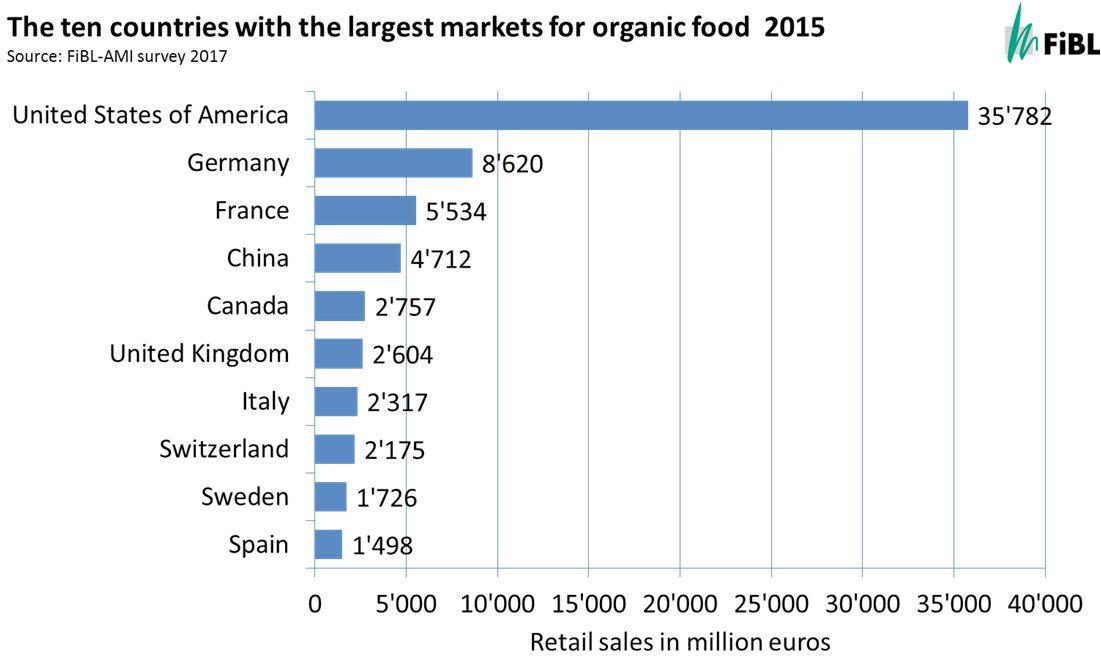

According to the Organic Trade Association, total USA organic product sales in 2016 reached nearly USD $50 billion, with double-digit growth over the previous five years.

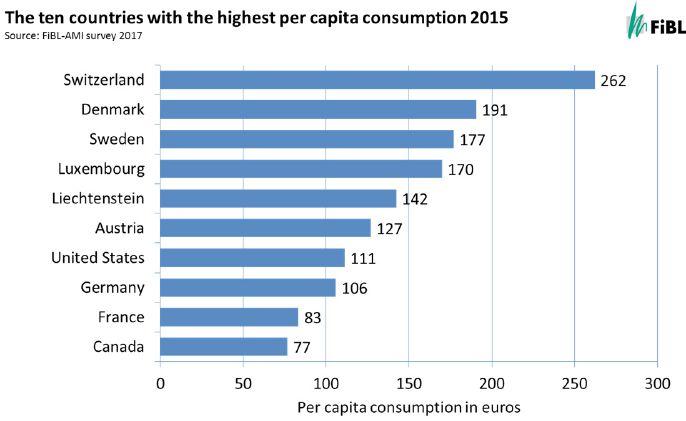

While Switzerland has the highest per capita annual spending on organic (262€), and Denmark has the highest organic market share (8.4% of the total food market), the USA has 48% of the global organic market according to 2015 data from the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture.

Consumers are becoming more aware about how their food is raised. I can’t find a record of the percentage of seafood that was organic, but I suspect it’s close to zero.

Because organic is about the process of production, you will not see organic wild fish on the market. For aquaculture on the other hand, the EU and Canada have organic standards. Internationally, IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements) is developing an aquaculture standard. The United States has a draft standard, which has been in the works for more than a decade.

Here is a look at what those standards say about RAS.

At the IFOAM General Assembly this past November, to provide guidance on writing the aquaculture standard, it was passed that, “Organic aquaculture may include an environmentally integrated recirculation system only if it is primarily based on and

situated in a natural environment. It does not routinely rely on external inputs such as oxygen, allows the raised species to spend the majority of their lives in outdoor facilities and preferably uses renewable energy.” If the standard ends up following this guidance, then it won’t have any organic production in RAS. Maybe the fish really do care about nice fresh outdoor air and butterflies fluttering by, but I doubt it.

The EU organic standard (710/2009) states that, “Closed recirculation aquaculture animal production facilities are prohibited, with the exception of hatcheries and nurseries or for the production of species used for organic feed organisms.” It seems well suited to net pen production. According to Emmanuel Briquet, who helped create the EU standard, the reason Europe

excluded RAS was “because of the higher densities at which fish may be reared in RAS, as well as it not representing well enough the predominant European vision of organic production systems.” Briquet and others are working toward having RAS permitted in future EU standards. He says, “they believe that RAS fulfills one of the primary pillars of organic production: ‘respect for nature’, by way of the high level of control on impact that is inherent in RAS.”

The draft of the USA organic standard does allow for RAS; however, according to George Lockwood, who chaired the organic aquaculture workshop at Aquaculture America in Las Vegas this past February, they “have been unable to get the proposed final rule moved from the hold list to the active list.” This means that the USA authority is not presently working on it; thus, the three-hour organic session in Las Vegas lasted only 15 minutes – just like the previous year.

This past February, the updated Canadian Organic Aquaculture Standard (CAN/ CGSB 32-312 2018) was released. It specifically allows for RAS, stating, “Recirculation systems are permitted if the system supports the health, growth, and well-being of the species.” Finally, something to work with.

Don’t despair if your market is not Canada: you can farm under the Canadian standard anywhere and sell as certified organic in most global markets including the USA.

Do the requirements work for RAS?

Requirements are numerous and similar to terrestrial organic standards in regard to GMO, antibiotic, hormone, and pesticide use. Unlike the EU, the Canadian standard does not prescribe densities in RAS as these would be impossible to determine for each species of fish at each life stage. Instead, the standard requires proper water quality and conditions that promote overall health of the animals. Health and welfare are central to organic standards and are already at the forefront for many in the aquaculture industry. Organic certification lets the consumer know that as well. With its ability to control water quality, exclude disease, and minimize stress, RAS is well suited to meet all the organic requirements.

How many of you have tried to market RAS-grown fish? While you were explaining RAS, how many of your customers were like a deer in the headlights? Marketing RAS may be an impossible task. People don’t want to know those details: they just want a piece of healthy, boneless, skinless protein. Yes, there is a demographic that specifically desires fish raised in RAS, but it is so minuscule that RAS capacity already being built could fill this niche. Compare that to organic. Even though the consumer doesn’t read an organic standard, they still know what “organic” means to them: it does not need to be explained. If organic is important to them, they will consider it at the seafood counter, and be willing to pay more.

The

I was recently shopping at a Canadian Costco and noticed the excellent price of farmed Atlantic salmon. Yet, the organic chinook salmon price was 68% higher. Was it the chinook or the organic that made it more valuable? I needed a side-byside comparison. At Aquaculture America, George Lockwood said that Wegmans, a retail chain in the Eastern USA, “since 2010 has been selling EU organic salmon with major premium prices.” To ascertain what a “major premium price” was, I

checked pricing at Wegmans, and discovered that EU organic Atlantic salmon fillets ($17.99/lb) were selling for an 80% premium over conventional farmed salmon ($9.99/lb). That is major (though don’t put that in your budget).

Be aware that organic production adds challenges and expenses. You have to believe in organic and be passionate to make it work. Organic seafood is now at the stage of the basket of apples in the corner of the store. However, it won’t be long before consumers, and producers, become aware of it.

By Rob J. Davies

Recirculating Aquacul-

ture Systems (RAS) present us with an alternative to seawater net-pen aquaculture. The recent struggles with net pen licenses, and legislation in general, have made it difficult in many countries to expand current sea farms or create new ones.

Although net-pen culture has an essential role to play in the expansion of aquaculture, an alternative method of farming saltwater species needs to be developed in parallel and in a complementary nature (e.g. supplying net-pens with fish to on-grow). This alternative (RAS) utilizes advancements in filtration, husbandry and monitoring technology to control the undesirable factors of fish farming, reduce risks to the stock, and help produce a stable product that is grown efficiently in optimal conditions year-round.

There have been many reports of new RAS failing after only a few years of production. This was documented in a 2010 report by CEFAS as being up to 40% between the years 2000 and 2010 in England and Wales.

The main reasons for these failures have been fundamental design constraints, operational costs and management failings. This is not surprising to any RAS farmer, as many I have spoken with come back to the same issue – the facility

Rob J. Davies is a principal aquaculture consultant with AquaBioTech Group in Malta. For more information go to: www.aquabt.com or email him at: rjd@aquabt.com

could not produce its expected tonnage. This means that the financials – the very concept the farm was based upon –were flawed, owing to overestimation of production and underestimation of costs.

Another issue is that RAS facilities may not be suited to their production functions. This is a trait that has damaged the reputation of RAS, because it is less costly and easier for companies to sell a system they have already designed, as opposed to a system specified to fit the needs of the farmer for his or her unique situation, site and species.

Farmers want a realistic (and achievable) production target from a system that has the right number of tanks, which fits in with their production planning and is able to cope, not only with the densities

and feed amounts that are required, but also the mistakes, technological mishaps and human errors that come with operating a RAS facility.

Therefore, safety margins for the biological and technical systems being installed must be high and the operation of the facility must be based upon a realistic and detailed production plan from the first conceptual design.

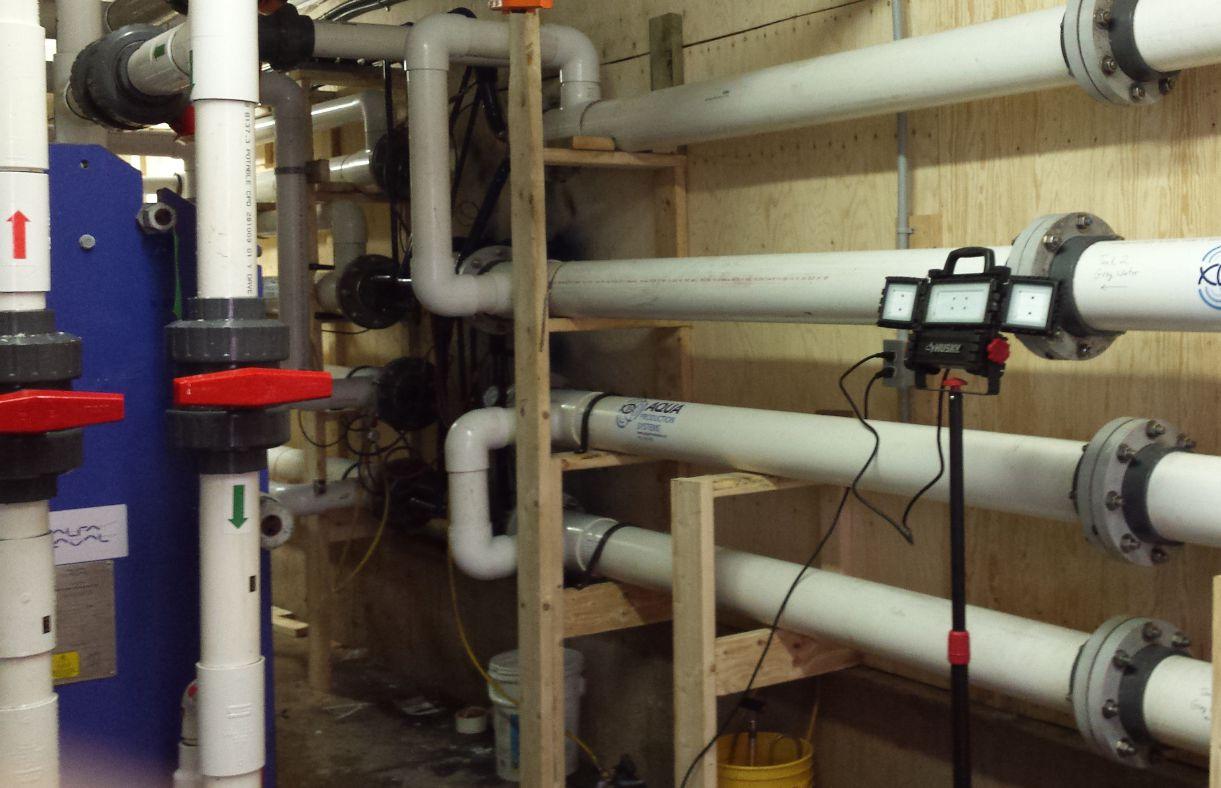

Another major factor concerning operational costs and production efficiencies is equipment failure and the inevitable consequent reduction of growth. This is hugely abundant in seawater RAS, partly due to the lack of experience of RAS designers and farmers, but also because of the high costs associated with the quality of equipment and material that is required in order to build a reliable RAS in such a corrosive environment.

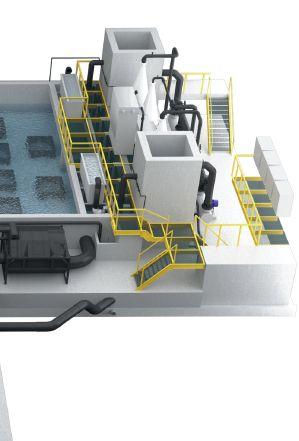

My colleagues and I, from various backgrounds (academic, RAS farming, engineering, maintenance, architectural and veterinary) and nationalities, have combined our experiences in the design and operation of seawater RAS, to build facilities based on what we believe are the farmer’s needs. This means a facility with a reasonable production plan (and safety margin), allowances and redundancies for things going wrong and the use of high quality equipment.

The materials we typically use in these situations are duplex and titanium for our drum filters and backwash pumps, for example, with a minimum of 316L/duplex grade of metal where required and high-strength biaxial weave fiberglass and non-metallic components for all other items. All pumps are high performance and non-metallic, with variable frequency drives and a system design which is extremely energy efficient in order to minimize operating costs.

The components in our designs are first tested at our R&D facility and the operations of the farms are determined from the perspective of a RAS farmer. This means incorporating such items as custom-made fiberglass fish crowders to reduce personnel required for handling operations, as well as purging and draining ports for ease of cleaning and maintenance.

An example of one of our facilities, due to be completed

within a few months, is phase II of the Sheikh Khalifa Zayed Marine Research Center in the UAE. This incorporates several tank types (round, d-ended, shallow, deep...etc.) and a variety of systems in order to provide optimal conditions to the broad spectrum of species that will be bred, hatched and grown there. Each specific system has been sized and calculated using engineering, 3D architectural and bio-planning software to customize it to the operator’s needs in this particular situation. The facilities consist of 69 fish tanks, 28 live feed tanks, 12 egg incubation and general experimentation tanks and other operational components such as custom made grading troughs, in-tank egg incubators, tank partition dividers and crowders.

To summarize, in order to achieve a successful and sustainable seawater RAS farm, designers need to start looking at the facility from a farmer’s perspective and stop promising unachievable production tonnages from systems that do not take into account the true operating and maintenance costs of a RAS facility. In addition, we need to ensure through training and after-sales support that staff

Ultraviolet water treatment for fresh and salt water for Aquaculture, Pisciculture, Aquar iums and Fish ponds C

operating the facility are well versed with the technology and that the systems run as intended.

Only then can we achieve the true potential and bright future of RAS for sea fish, freshwater fish and other aquatic organisms, all of which will be needed to feed the predicted increase in world population in a healthy and sustainable manner.

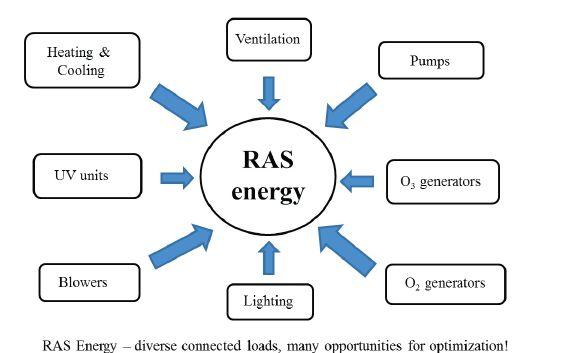

Addressing the high energy consumption challenges associated with RAS use – first in a four-part series

By Maddi Badiola

In 2013, the European Union’s food sector was a major consumer of energy, accounting for 26 per cent of final energy consumption. Agriculture and livestock production were responsible for 33.4 per cent of the energy costs associated with food consumed in the EU.

Farming is one of the major causes of environmental problems, and aquaculture can claim its share of the blame. Public criticism has pushed the sector to find acceptable practices from environmental, societal and economic perspectives.

Farmed seafood is a very efficient protein source in terms of resource use, water, feed and land utilization. Its environmental footprint is significantly smaller than terrestrial livestock and its feed conversion is much more efficient. It can be argued that the answer to food security and ocean conservation is in sustainably farmed seafood.

However, the lack of space for expansion limits fresh water availability, and pollution concerns are considered obstacles for further enlargement of conventional cagebased and flow-through aquaculture systems. Fish escapees, biosecurity, mangrove destruction, wildlife interactions and product traceability have been some of the problems related to aquaculture. So, how can fish be produced in a sustainable way? This author believes that RAS is a clear choice.

RAS poses few risks to the environment and can be established in many areas. It can be used when water availability is restricted: enabling 90 to 99 per cent of water to be recycled. RAS allows the operator greater control over the chemical, physical and biological water quality parameters, enabling optimal conditions for fish culture. There’s little need for antibiotics; the fish can be fed more effectively than those in net pens and waste can be pumped out of the facilities and

Badiola, PhD, is a RAS engineer and co-founder of HTH aquaMetrics llc,(www.HTHaqua.com) based in Getxo,

Basque Country, Spain. Her specialty is energy conservation, life cycle assessments and RAS global sustainability assessments. She can be contacted by email at mbadiolamillate@gmail.com

taken to composting sites. Also, there’s zero interaction with wild counterparts.

In recent years the number of RAS farms around the world has steadily increased. According to a research conducted by this author in 1986, 300 mT of fish were produced in Europe while in 2014 the number was over 15,000 mT. During the same period, the number of RAS installations grew to around 360 in the U.S. and Europe. Norway and Canada represent important RAS industry countries, mainly for salmon smolt production, while China is increasing its yearly production with the construction of new, large indoor RAS facilities. This increased number of RAS farms around the world coincides with an inherent use of energy and its consequences for both companies and the environment, regional and global.

In 2014, this author worked with the

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program to bestow a “Best choice-green choice” sustainability rating on RAS systems around the world. During that process of sustainability evaluation, one aspect of concern that came to light was the high energy requirement of RAS systems and the need to make improvements in this area.

Having water in continuous re-use and constant pumping can lead to elevated electricity costs. Thus, this high-energy requirement is a challenge which increases operational costs in terms of energy, equipment wear-and-tear and ensuing operational and management costs. On-farm electricity consumption could affect both environmental impacts and economic costs of a RAS, reducing the farms’ sustainability.

In 2013, the energy consumed in the fishery sector, including aquaculture, was equivalent to almost five per cent (i.e. 45 Petajoules, 12.5 teraWatt hours) of the direct energy consumed in the agriculture sector. This clearly shows that energy plays a vital role in food production around the world.

New renewable sources of energy like solar, wind and geothermal, contribute about two per cent of the present world’s energy use. In aquaculture, and mainly in RAS companies, this should be an important consideration when designing or redesigning a production system. The interest in using renewable energy sources or waste from other industries should be part of the solution to further decrease the environmental impacts of RAS.

In the long term, the economic benefits would be tremendous for the companies involved. This change in mindset would also yield societal improvements, more efficient systems and thus, more sustainable global fish production systems.

The energy sources to be employed at a farm will be dictated by the system’s location and its accessibility to the energy sources. Thus, the location of RAS operations, sometimes in remote areas, may make it easier to use renewable energy. We must take advantage of such opportunities.

You have to measure it to improve it. So, what do we measure and how do we measure it? This article is the first in a series to address energy sustainability issues with RAS. Look for future articles in upcoming issues of Hatchery International and RAStech.

By Steve Summerfelt and Bendik Fyhn Terjesen

Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) technology development has been and continues to be a melding of borrowed engineering. Components of RAS originate from municipal and industrial wastewater treatment industries with applied research and development specifically on aquaculture technologies by academics in public and private institutions, as

well as a little creative ingenuity provided by farmers, consultants and system suppliers. This melding of technology has not always worked, but we are now seeing many more RAS facilities meeting their production goals.

It was only about twenty years ago when the first handful of RAS were effectively used to produce millions of Atlantic salmon smolt in North America and

most other major salmon producing countries. Today, market-size Atlantic salmon are already being produced at commercial RAS facilities in Canada, Europe and China, but such facilities are just beginning in the United States. The first commercial RAS farm in the United States to produce 4-5 kg Atlantic salmon, Superior Fresh (Wisconsin), will begin marketing salmon and steelhead this summer. It has already begun production of just under 1,000

ton/year of salad greens.

In Florida, Atlantic Sapphire is building a RAS complex that is said to be capable of producing nearly 8,000 tons of market-size Atlantic salmon annually, with a later up-scaling to 90,000 tons per year.

Following these leaders are Whole Oceans and Nordic Aquafarms; both are working to permit and begin construction on large RAS farms to produce Atlantic salmon in Maine.

Meanwhile, Hudson Valley Fish Farm has started marketing steelhead produced in its RAS facility in New York; and, AquaBounty has requested permission to produce their “AquAdvantage” Atlantic salmon at an existing RAS facility in Indiana.

There are several other projects that haven’t gone public yet, but these could easily push total U.S. investment towards US$500 million by 2020 and much more by 2030.

Another use for commercial RAS that has been developing rapidly in the last decade is for producing post-smolts of Atlantic salmon. Post-smolts are salmon that have achieved sea water tolerance and weigh less than 1-2 kg.

By using post-smolts for stocking in sea, instead of normal-sized smolts at around 100g, it is possible to reduce sea phase time and fish mortalities, reduce issues with sea lice, improve harvest volume, and more efficiently use sea sites. Currently, this technology is developing mostly in Norway, but salmon farmers in other countries are also looking into this production strategy.

The facilities needed to produce postsmolts on land can be an order of magnitude larger than for smolts. Facilities capable of producing several thousands of tons per year are now commonplace, and each provides total tank volumes exceeding 25,000m3. This development places new and increased requirements on

the efficiency and reliability of RAS.

It was also only about twenty years ago when micro-screen drum filters really

became the solids treatment technology of choice. Oxygenation systems were being added to intensify production, and soon after, many RAS suppliers began to look for technologies to control CO2 accumulation within these systems. Refinements and innovations in oxygenation and CO2 control continue to this day. Future improvement will be important because currently, CO2 is one of the defining factors for total system flow and has a great influence on energy use and environmental footprint in RAS.

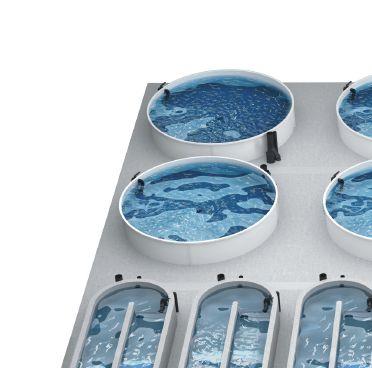

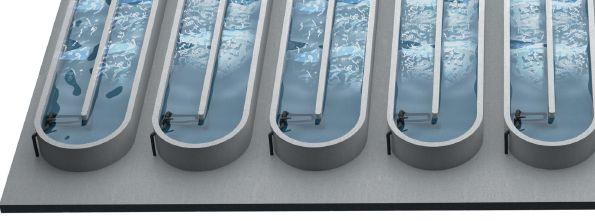

In that same time frame, circular tanks have been recognized by many to be the best culture environment for RAS because of the relatively homogeneous water quality that they provide. Hydrodynamics in circular tanks are better suited to supplementation with pure oxygen than linear raceways, where less desirable concentration gradients can arise. In addition, the impulse force

created by water addition or removal from circular tanks can be adjusted to control the rotational velocities within the tank to rapidly concentrate and remove settleable solids.

Hydrodynamics in circular tanks also allow for good feed distribution and can permit designs that allow for visual or automated sensing and regulation of sinking feeds.

In the future, circular and octagonal tanks are going to continue to become larger and deeper. Such tanks are now approaching 10m depth and 30m diameter in some instances, but even larger tanks are likely in the future. In contrast, the Danish model trout farms and the Veolia RAS 2020 rear fish in raceways within RAS to optimize biomass density management as multiple cohorts move through these partitioned raceways. These raceway-type systems are challenging the status quo when compared to circular-type tanks, yet their use is still a trade-off between benefits/challenges.

It’s not yet clear if either will have a definitive advantage.

It will be important for future development of RAS technology that the tanks and their hydrodynamic properties are clearly defined along with the other RAS components. Unfortunately, this is not always the case when major land-based rearing facilities are constructed. If the tank self-cleaning is not working then other RAS treatment processes and fish performance can deteriorate.

Biofilters have seen tremendous improvements, and there are many different types applied within RAS. Trickling filters, submerged filters, moving bed biological reactors, and fluidized sand biofilters are all broadly applied in different regions and in specific-niche applications.

Most RAS insiders will know applications where each type of biofilter has performed as required or did not perform

as expected. It is rather shocking to us that there are still biofilters being built that cannot control ammonia and nitrite at safe levels for the fish species cultured. In addition, there are substantial differences in performance, foot-print, fixed and variable costs between the various biofilter types. Often the type of biofilter built at a given farm seems to have been determined more by the preferences of the RAS supplier than by the likings and needs of the staff that are operating them.

Ozone is applied more often in RAS to oxidize refractory organics, which removes color, and micro-flocculate small particles. Controlling suspended solids is one of the greatest challenges in RAS for numerous reasons and future facilities will have to use ozonation, foam fractionation (in brackish/seawater facilities), and contact filters to better control suspended solids.

The scale of RAS construction has surged over the past five years and these systems are expected to continue to grow larger into the future. Building larger RAS provides critical economies of scale to reduce both fixed and variable costs. Fortunately, at least some continuity between projects – i.e., when the same turnkey supplier or farming company is involved with each successive RAS iteration – has allowed these RAS to improve technology, standardize equipment and construction methods, and in due course improve performance, reduce risk, and/or reduce capital and overall operating expenses.

Greater investment in RAS for all phases of Atlantic salmon and Pacific salmon (particularly steelhead and coho salmon) are producing advances in technology that are accelerating its deployment. There is also risk associated with in -

creased scale if it leads to a technology or operating failure. One way to mitigate this is to utilize technologies that have already been proven to perform at large scales in other facilities. Thus, it’s critical to avoid large-scale application of technologies that have not been proven at similar scale, temperature, or salinity whenever possible.

In addition, multiple RAS can be used to meet the same production goal and avoid the use of just one enormous RAS. In particular, if the biomass is split over multiple systems, it can sometimes improve biosecurity and provide some redundancy to reduce risk.

There are currently tremendous differences in technologies, water quality and production capacities between different RAS facilities. Water flows and the assimi-

lative capacity of the water treatment processes must maintain optimum water quality levels within RAS at up to a maximum sustained feed loading, which is the carrying capacity of the RAS.

Even the very best designed and dimensioned RAS cannot handle more loading, i.e. feeding rate, than it is rated for without reductions in water quality. For example, feeding a RAS at 1.5-times the RAS carrying capacity can produce significant water quality challenges even for the best designs. Future RAS projects must do a better job of controlling water quality in order to maintain optimal fish growth, health and welfare.

We often recommend that when producing Atlantic salmon the following criteria must be met when operating at maximum feeding capacity: low suspended solids levels (less than 5-10 ppm), relatively low turbidity, dissolved oxygen

saturation >85% and total gas saturation at just below 100% (which can be achieved when a vented and low-pressure oxygen transfer device is used, such as a low head oxygenator), dissolved carbon dioxide concentration at less than 12-20 ppm (depending on life stage), nitrate nitrogen at less than 100 ppm, and water velocities of about 1-1.5 body length per second. Some of these criteria will depend on life stage and interactions with other environmental factors.

When we encounter facilities that are not meeting such criteria when operated within the RAS’s design carrying capacity, it is sometimes uncertain if such deficiencies are an operational error or a design error.

There are many advantages with brackish water salinities, around the isotonic point for the fish, i.e. 10-12 ppt salinity, in terms of growth, FCR, and skin health. However, there continue to be challenges created when salmonid RAS are built for use with salinities greater than about 5-12 ppt.

In the past, salmon smolt have always been produced in freshwater RAS and the farmers and suppliers have considerable experience with such freshwater production systems. In contrast, many of the RAS used to produce post-smolt and even market-size salmon are using brackish water and even full-strength seawater.

Adapting RAS to seawater has sometimes created challenges, as water treatment processes must be larger to account for reduced efficiencies in CO2 stripping, nitrification, and oxygen-holding capacity in seawater. These differences make

brackish-water RAS more expensive than a freshwater RAS of similar production capacity.

In addition, bromide can be oxidized to produce toxic bromine compounds when ozonating brackish-water RAS and sulfate can be reduced to more toxic hydrogen sulfide in environments if sludge accumulates, and/or oxygen and nitrate are depleted. Particular care must therefore be placed on using high efficiency particle removal equipment, on avoiding deadzones and on accurate and relevant sensors.

In the future we may also see RAS in which some salinity is used, to exploit the physiological effects, but where the salinity originates from addition of specific salts in low-flushing systems. Thereby bromides can be avoided and possibly even sulfates. To date, the learning curve has been steep, but farmers and RAS suppliers are getting better at accommodating these differences.

Challenges remain when implementing RAS; the devil is clearly in the details, as many RAS producers still face problems. Yet, continued government and industry support for education and training of future generations, as well as improved technologies and practices through research and development, will be critical to future success.

Steven Summerfelt is director of Aquaculture Systems Research, the Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute in Shepherdstown, WV, USA. Email him at ssummerfelt@conservationfund.org

Bendik Fyhn Terjesen is innovation manager, Cermaq Group in Oslo, Norway. Email Terjesen at bendik.fyhn.terjesen@cermaq.com

1. Culture tank exchange rate inadequate to meet the oxygen demand of the fish or even flush the CO2 produced through the culture tank when the oxygen respiration approaches or exceeds 10 ppm each pass;

2. Culture tank hydrodynamics inhibited by placement of screens, nets or structures across the flow and the impulse force is consumed by drag, which prevents water rotation from transporting solids to the bottom-center drain and creates non-homogeneous water quality conditions to the detriment of the fish;

3. Culture tank inlets placed at a wrong position in the tanks, and where there is no possibility to adjust inlet angle or individual nozzles;

4. Biofilters designs that fail to consistently maintain total ammonia nitrogen below 10 ppm when the RAS is operating at the design feed load;

5. Biofilters that fail to consistently maintain nitrite-nitrogen below 0.4 ppm when the RAS is operated in freshwater at the design feed load;

6. Biofilter startup challenges that kill fish, and chloride (salt) wasn’t added to minimize nitrite toxicity;

7. RAS that does not contain alkalinity supplement and feedback systems;

8. Sensors not sufficiently protected against excessive biofilm. growth or where clear maintenance recommendations are lacking;

9. Solids that don’t rapidly flush from the culture tank, encountering conditions such as aeration, pumps, or mixing fans that can break them into finer particles that coat the gills of fish, inhibit nitrification in the biofilters, or harbor opportunistic pathogens;

10. Ozone generators that do not handle power fluctuations and can rapidly fail with lightning strikes.

By Diogo Thomaz and Antonio Coli

Compared to on-shore grow-out farms, where water is pumped through tanks and raceways, fish hatcheries and nurseries use significantly less water. The reason is that the biomass produced in these facilities is normally 10 to 100 times smaller than in grow-out farms. So, why is there a need for RAS technologies in fish hatcheries?

There has been a significant improvement in survival performance over the last 20 years in many Mediterranean hatcheries, resulting in the production of many more weaned fry than the nursery can pre-grow. Effectively, nurseries have become the bottleneck in production. Often, this is not due to the lack of available tanks but to the limited access to good quality water to allow for healthy growth of fry in these nurseries.

One of the key reasons industrial hatcheries in the Mediterranean needed

RAS technologies was to significantly increase the volume of water available in their nurseries.

Other factors, such as stable water quality, lower heating or cooling costs and better production planning, are also relevant in some cases – but water availability remains the key reason for using RAS.

Based in Greece, Selonda Aquaculture is one of the largest marine fish farming companies in the world. After the merger with Dias Aquaculture, another large Greek aquaculture company, it increased its annual production capacity to 32,000 tons of portion-size fish.

Selonda is also one of the largest marine fish fry producers in Europe with an annual production of approximately 160 million marine juveniles per year. The majority is sea bass and sea bream.

The group operates six hatcheries, five of which include all departments from broodstock to nursery. The sixth one operates only as nursery and pre-growing, and also as a support facility for the breeding program of the group. All six hatcheries – although operating under common principles and methodologies as a very closely cooperating team – are different in terms of size, set-up, water sources, age of the facilities, and others.

Historically, Selonda has focused on building its hatcheries’ technology and expertise. One area that has always attracted the group’s attention was RAS technologies. In 1992, Selonda bought a majority stake in a company specializing in RAS technology, and formed the International Aqua Tech (IAT). Following the acquisition, the company started introducing RAS technology in its

hatcheries, starting with its first hatchery in Selonda Bay. Water in the two nursery blocks was treated and re-used using RAS.

In the following years, IAT was involved in several RAS projects around the word. The Selonda group of hatcheries, meanwhile, expanded its RAS utilization to new hatcheries that were being built or acquired by the group, based on the initial design of the first systems and the experience gained through the years. So, several new RAS systems were built to support increased production needs.

Today, 37% of the total nursery culture volumes in all six hatcheries are operating with RAS. Also, 25% of the first feeding department of one of the big hatcheries of the group is also operating with RAS. Four of the six Selonda hatcheries are using RAS; the hatcheries in Sagiada, Managouli, Psahna and Mytilini. The company will be investing in RAS for its other hatcheries in Tapies and Larymna over the coming years.

In installing RAS, the company prioritized those facilities where RAS will have the highest returns. The investment aimed to tackle specific bottlenecks at each farm that were preventing the production level from increasing. The company also wanted to keep the cost per fish at low levels mainly by minimizing losses from accidents and lower degree of control. Eventually, the additional investment and operational costs were well absorbed by the improvement in the KPIs.

All RAS are rather simple in design, with a high degree of new water entering the system per hour. Simplicity refers to a basic level of mechanical filtration, simple biofiltration, manual control and operation. The fraction of new water entering the RAS per hour is three to eight% of the total circulated water, and the water exchange rate in the fish tanks is between 60 and 100% per hour, depending on the system and size of the fish it is applied on. In the first feeding depart-

ment, new water introduction rates varies according to the age of the fish and the degree of water circulation.

The RAS concept described above illustrates a balance of several factors: relatively low-cost design, simple management, operational needs and high degree of production safety in respect to fry quality.

Flushing out some of the fish respiration and digestion by-products as well as biofilter products, together with a portion of the suspended solids, creates a favorable environment for the fish to grow. It requires relatively low RAS management skills and maintenance costs. Failure of these systems is unlikely to happen, and when it does, it is normally a result of a serious failure in equipment. However, this kind of scenario should be predictable well in advance if it is likely to occur.

Today’s RAS technologies are either designed for a group of tanks or for individual tanks. The selection relies on

the existing set-up, the available space for the supporting equipment, the ideal strategy per nursery operation, and the balance of risk.

The strategy of Selonda for the future is to significantly advance its existing RAS setup, and install new systems in the remaining nurseries that now operate flow-through systems. The target is to even double stocking carrying capacity of the existing systems and similarly on the flow-through systems that should be increased from 37% to about 65% within the next one-and-a-half years.

A large part of the development of the existing RAS will include improvements in automated control systems. Sensors and control boards will allow better operational control, even remotely. These technologies will be introduced gradually in the current systems, as personnel will be adapting to this new concept of RAS automation.

Introduction of additional mechanical filtration systems and expansion and/ or modification of the biofilters will also be part of the improvements of all existing RAS. Although ozone technology has been introduced from the very first systems in the first hatchery in Selonda bay, its use remains limited in current systems and without automated control. Strategically, the intention is to

introduce ozone technology in all current systems and in the new ones.

Finally, significant improvements in the hydraulics, aeration, oxygenation and degassing with some of the most advanced concepts will play a key role – not only in the RAS elements, but the fish tanks themselves, where the set-up

will enable higher stocking densities under improved conditions. Closer monitoring of the different bacteria populations on a regular basis will also be a necessity as recirculation intensifies.

The accumulated experience of Selonda’s hatcheries division team on designing, setting-up and operating the RAS in the hatcheries is adequate to support the transition to the next level of higher efficiency systems. This experience, together with training on specific topics will secure the expected return on investment.

Diogo Thomaz, PhD, MBA, is a technical and business consultant for the aquaculture industry, based in Athens, Greece. After 15 years as R&D project manager and other industry positions he now leads Aquanetix (www.aquanetix.co.uk), a data management and reporting service for the global aquaculture industry.

Antonio Coli is the head of hatcheries at Selonda Aquaculture.

By Nate Wiese

For more information contact him at: nathan_wiese@fws.gov.

By Nathan Wiese

Arare trout makes its home in the upper reaches of the Gila River of New Mexico and Arizona. The Gila trout (Oncorhynchus gilae) is native only to small headwater streams where it was landlocked thousands of years ago from sea-run Oncorhynchus species. The status of Gila trout improved from ‘endangered’ to ‘threatened’ in 2006, but they are still in a precarious situation. In the arid Southwest, recovery efforts through hatchery supplementation rely on recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) technology.

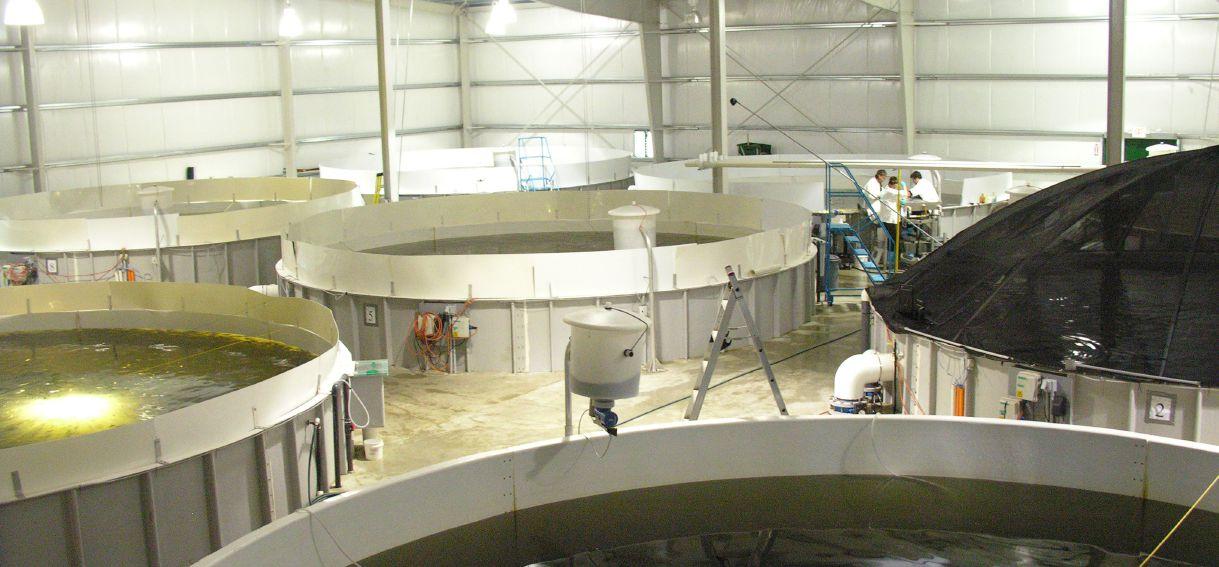

Mora National Fish Hatchery in New Mexico was commissioned in 1998 and now has the sole purpose of Gila trout refugia for recovery. Three main RAS systems are supplemented with five isolation RAS systems to maintain five distinct lineages of Gila trout for recovery stocking.

The hatchery has taken significant advantage of RAS. I ran hatcheries in Idaho for a decade with facilities utilizing up to 90,000 gallons per minute, first-

pass water. With that experience, RAS seemed a scary proposition. I am now running a facility with only 800 gallons per minute of available water, and I’ve realized how inefficient large-volume facilities are. With competent staff and a modern RAS, you can get a lot more out of a gallon than from banks of serial reuse raceways.

Mora takes advantage of RAS for water treatment: housing all rearing vessels indoors, increased swimming velocities

for rearing, manipulating photoperiods for spawn timing, and easy changes to tank configuration. Compared to traditional hatcheries, Mora is built like a Lego set. Tanks and plumbing systems all sit on a concrete slab, so as the program needs change, only simple hand tools are required. Try changing the configuration of concrete raceways, and you’ll need a team of jackhammers, a cement plant and dollar figures with six zeros trailing.

The hatchery rears captive broodstock lines in a large RAS system. These broodstock are supplemented with wild-captured Gila trout held in small RAS quarantine systems. The nature of RAS allows us to put quarantine areas in small rooms that were originally lab and storage spaces. With existing walls, you’re only footbaths and a two-inch freshwater supply-line away from having a sequestered area to hold wild fish. Plus, you’re indoors so you can manipulate photoperiod with light timers to match your captive lineages.

These RAS quarantine areas allow the hatchery to provide refugia for Gila trout displaced by wildfires, and incorporate wild genes into the captive broodstock. When the habitat recovers in three to five years, these areas can then be re-stocked with the original fish or their progeny.

Thanks to research at Cornell University, RAS is now almost synonymous with dual-drain circular tanks. In the mid-90s, during the design of Mora, the jury was still out. Today, Mora has a combination of circular and linear tanks. This has given the staff great opportunity to compare traditional raceways with circular tanks. Hands down, the circular tanks are a favorite. By increasing the velocities to two body lengths per second in circular tanks, the staff noted improved food conversion efficiencies and lower fat levels in Gila trout. The self-cleaning nature of circular tanks and preparing the Gila trout for the rigors of the wild on a 24-hour treadmill make circular tanks a favorite over traditional raceways.

Egg incubation is completed on firstpass water. So, RAS isn’t used for everything. The staff at Mora had found that egg trays work almost like a biofilter in the RAS system. Debris that passes the drum filters and biofiltration can enter

the incubation stacks. The eggs then act as a filter themselves, which increases issues with fungus. This, of course, is because the facility is maintaining fish and eggs simultaneously. Fortunately, the first-pass water from the incubators can be reused as the make-up water for the RAS system. We recycle egg incubation water, just not back onto our eggs. If we were only doing eggs at that time, a RAS would work great.

Operating Mora’s RAS has been a challenge over the years. When you commission a hatchery, you want to eliminate as many variables as possible. At Mora, we commissioned the system for an endangered species that was either untested or hadn’t succeeded in other propagation efforts. Our early endeavors with Gila trout were a struggle because we didn’t have the RAS dialed in. A big issue at Mora was chronically elevated total gas pressure. Between elevated ground water levels (115% saturation) and pump cavitation, the environment was continuously supersaturated with nitrogen at 105%. That wasn’t enough to cause mortality, but was a constant stressor on the broodstock that decreased eye-up significantly. Now, vacuum degassers supplement the original degassing equipment to maintain nitrogen saturation below 100%.

In addition, early research with Gila trout showed significant benefits from

enriching the rearing environment. This involved placing gravel and other structures in the rearing vessels. While this did excellently in a research environment, scaling up to facility-wide implementation caused unforeseen consequences. We had mats of fecal material breaking loose periodically and then pulverizing on the drum filters. This caused intermittent plumes of ammonia that were nearly impossible to detect with our routine water-quality sampling protocols.

The hatchery has since switched to 2-D enrichment environments with the help of inlaid fiberglass veils. You can print anything these days. We looked at the problem and said why not make an aquarium background on the inside of a fiberglass tank? With some calls to the right tank manufacturers we had a solution. Now the fish have the benefits of enriched environments while maintaining the high water quality needed in a RAS.

I’ve worked at hatcheries for two decades and have done the sleepless nights for a long time. With RAS, I can pull up our entire system on my Android phone from anywhere with a cell signal, and check systems, turn pumps on and off, and have peace of mind. Would I go back? No way. The future of inland fish rearing is RAS. Once you make the commitment, you may even throw away your flip phone.

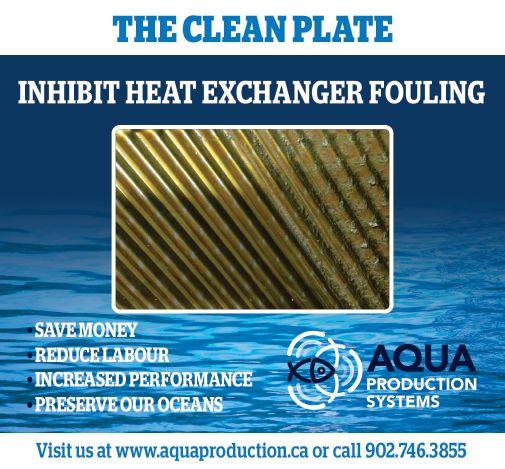

Do you control your temperature or does your temperature control you? By Philip Nickerson

Consider these two scenarios:

Business A – Fish enters farm at two grams in September and reaches 30g two years later; Business B –Same species of fish enters farm at two grams in October and reaches 30g in nine months.

Why the dramatic difference? Temperature.

In the first case, the fish were exposed to ambient temperature (other than heating to prevent lower lethal temperatures). In the second case, a temperature suitable for rapid growth was maintained continuously. Which business would you prefer?

It is widely accepted and a widely practiced staple of aquaculture that fish growth varies significantly with temperature. This is due to the poikilothermic nature of fish. As temperature rises, so does the metabolism of the fish. Metabolism rate affects feeding rate, which

affects the rate of waste production, and the rate of respiration. Therefore, temperature is a variable that contributes to the design of every major component of a RAS system.

So, what happens if the farmer wants to grow fish at 13°C but the cooling system is only capable of maintaining 15°C in summer months?

This situation occurred at a land-based RAS farm, which we will call Business C. The CEO of the farm was giving a presentation outlining the performance of the facility over its first few years. He noted two problems. First, “the chillers were not able to keep the temperature down to 13°C.” Secondly, the CO2 degasser system was not keeping up with its load.

After his presentation we discussed the connection between these two symptoms. The degasser would be sized for the expected loading at 13°C by the RAS designers. Is it possible that the degassers

work when the system temperature is maintained at 13°C because they can handle the load that the fish create at that temperature versus at 15°C?

When reviewing the cooling system, it was determined that the chillers were efficient. Unfortunately, when the process was set to maintain 15°C in the tank, the chillers were chilling water to 4°C. This resulted in a 25 to 30% decrease in chiller capacity. This is a common design error that increases the capital and operational costs. About 25 to 30% more chillers are needed to meet peak cooling demand. Not only does 25 to 30% mean more energy consumed, but the electrical demand charge will likewise increase. [As an aside: a chiller ‘pumps heat’ from one temperature to another. A water pump is sized proportional to the height (or lift, or head) that the water must be pumped. Similarly, a chiller motor is sized proportional to the temperature difference that the chiller is pumping

heat from and to. The smaller the temperature difference, the larger the amount of heat a given chiller will pump – and vice versa.]

The consequences of an extra 30% cooling cost can be devastating. By the time they are discovered, the capital funds have been spent and finding more funding can be difficult or even impossible. In other cases (such as the farm mentioned above), the finding was that the cooling system lacked 30% of the intended capacity. As a result, fish growth was negatively affected.

In Business A and Business C, the operators were not able to maintain the temperature they wanted. How does this change a business?

We all picture the aquaculture business as one where we push the fish to grow as fast as possible. But as soon as the temperature control system loses 30% of its effectiveness, the temperature starts to control the business rather than the business controlling the temperature.

In Business A, the farm is delaying growth by 12 months – in other words someone is taking more than twice as long to get the return on their investment. In Business C, the technician can only feed as much as the degasser can handle, even if the fish are hungry for more. The energy bill still needs to be paid, as do the staff, and all the other costs of owning the farm. RAS is too big of an investment to allow fish to grow slower than the business plan estimated.

The converse is also true – every part of

the system contributes to the temperature picture. Every motor is adding energy to the system. Every organism (fish or nitrifying bacteria, etc.) is adding heat to the system through metabolism. Aeration and water addition, and building envelope construction introduce ambient temperature effects. The trend to tighter RAS is bringing some high cooling loads and, in some cases, even eliminating heating.

There are two goals in the design of a heating or cooling system: an efficient system and an efficient engine.

Car manufacturers have made great strides in increased fuel mileage by reducing the overall weight of the car. RAS cooling loads have been reduced by the introduction of more efficient processes. Every kWh that you pay for is energy entering the RAS system. If you are in cooling mode, you need to pay again to run the chiller to remove that kWh of

energy from your system. Otherwise, the water temperature goes up. Every calorie of feed put into the system represents calories that need to be removed to maintain temperature.

The sequential order of focus in designing a temperature control system is as follows:

• Process

• Controls

• Equipment Process includes things like how much new water or ambient air is introduced to the system; how fast waste feed can be removed from the system; or how many levels of heat exchange are between the heating/cooling engine and the water to be cooled (one of the problems with the Business C case). One of the most impactful ways to decrease the process demand is through heat recovery of new water

and/or air for degassers or MBBR.

Controls are the second key contributor to efficiency. Drives are recommended on air and water pumps with variable loads. Especially in RAS where cooling is being applied – remember that there is a 25% (or more) cost for the chiller to remove the energy that was already paid for.

Only once the process and controls are determined should the cooling/heating equipment be looked at, with an eye toward what is the most cost-efficient choice.

There are many options for heating equipment and fuels with large cost variations geographically. Cooling options are more limited, although often more complex. There are two types of cooling: active and passive. Active requires a chiller, passive could be a deep-water line on the coast that draws in 5°C-water year-round, or it could be a cooling tower for the warmest applications.

Remember that the capacity of a chiller will change with the temperature of the water going through and/or the air it is using for cooling the condenser. Be sure to get a capacity rating at the temperatures you will be operating at so that all chillers being considered are comparable.

Philip Nickerson, P.Eng., is one of the owners of Pronova Marine Products Incorporated. Pronova leases marine and freshwater tank space and husbandry services at a landbased farm in Nova Scotia, Canada. He also owns and operates Aqua Production Systems, an aquaculture company specializing in heating and cooling designs. He can be reached at: philipnickerson@gmail.com

The emergence of recirculating aquaculture systems in the industry has led to a new business opportunity for a pair of Australian aquaculture veterans.

Lindsay Hopper (left in photo) and Ryan Whicker (right) are now at the helm of the newly launched Pure Aquatics, a privately-owned recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) design, supply and construction firm based at Wauchope, New South Wales in Australia. Backed by a combined 46 years in the aquaculture industry, Pure Aquatics provides end-to-end solutions from consultancy to installation for commercial, research, live seafood holding, public aquaria, aquaponics and wastewater using new filtration technology.

“We represent some of the most reputable and recognized world leading manufacturers in RK2 Systems – protein fractionators, UVs and energy efficient pumps – and AST Filters, such as Bead

and Polygeyser filters, including their new in-tank PGs ideal for decoupled aquaponics systems and low density culture, such a broodstock fish & prawns, among others,” said Hopper.

Pure Aquatics also offers plastic’s fabrication and customized filtration, as well as staff training, policies and procedures.

“Pure Aquatics provides customer-focused solutions to their customers,” Hopper said. The company’s products and services offerings are classified into nine main divisions: system design and consultation; equipment supply; custom design and manufacturing; wastewater and effluent treatment; maintenance and service contracts; installation specialists; training and management services; dosing, treatment and monitoring systems; and CNC machining and plastic supply.

Ro R tron Regenner e ativve Bl B owers offer r a reliable e soolut u ioon n f for movi v ng larrge amoun u ts of f a air at low to m meddium preessures th t roughoout your RAS S op o eration.

Ma M de in the e USA and d d distributed globally y to the aquaculture market by Sivat t S Servvices, these blower e s include:

• Options for r mu m ltip i le electrical l configurations and fo f r extreme duuty speci i l al coatings.

• Large line of accessories: intake filters, inlet/outlet mufflers, sound attenuation cabinets, pressure regulators, moistur u e separators and VFD’s

Invest in the best equipment for your RAS facility

• Degas Towers • Sand Filters

• Fractionators • Pumps

• Bio Filters • UV Sterilizers

• Ozone Systems

• Instrumentation & controls

• Heating & Cooling

• Bead Filters • Valves

• Blowers and more!

MAT Filtration Technologies of Izmir, Turkey builds and markets the MAT Skid Compact Filtration System which it claims is the “ideal and complete Life Support System (LSS) suitable for any specification of the public aquarium and aquaculture industry where space is of the essence.”

Some key components of the MAT Skid Compact Filtration System include protein skimmer/protein fractionator, UV sterilizer, ozone generator – ozonizer, oxygen concentrator, degasification bio tower/ trickle filter, moving bed biofilter reactor,

venturi pump, feeding pump and flow controllers.

For more information go to: www.matlss.com

Recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS) promote stable, year-round fish production by offering consistent conditions for fish quality and growth, while minimizing the risk of fish escapees. The enclosure of the rearing environment, along with water quality control and waste treatment devices, makes for optimized fish rearing by maintaining stable water quality parameters throughout the entire production cycle.

One key aspect for successful RAS operation lies within the nutrition of the cultured species. If the diets are not optimized for the life stage and species in the tanks, excretion of wastes will increase and these will accumulate in the circulating water.

For optimal performance, the system should be tailored to the diets and excreted waste of the species. The fish, feed and the system must then work together as a whole, as overlooking one aspect may lead to unexpected events in the operation process. In sum, a holistic approach needs to be taken to ensure that optimal feeds are given that promote the fastest fish growth with minimal waste excretion as these support the best system performance and guarantee the ideal rearing environment for the fish. For these reasons, the Skretting Aquaculture Research Centre (ARC) in Norway has increased its research capacity over the past year with the addition of advanced recirculation aquaculture systems. These independent RAS units

primarily focus on the process of recirculation, examining and optimizing the whole system while taking into consideration both inputs and outputs. The new facility has twelve tanks each with an independent water treatment loop which enables testing of the effect of different diets on RAS performance. In addition, each unit can be interconnected before the start of trials to ensure equal initial biofilter performance.

Partnering with the new systems is Skretting’s dedicated feed range for RAS – RecircReady. According to Skretting, “These diets utilize specialized feed components that facilitate biofilter operations by reducing the load of organic materials in the water, reduce phosphorus and nitrogen accumulation and discharge, and reduce turbidity or particular matter. This improves and stabilizes water quality, thereby enhancing filtration efficiency and fish welfare.” For more information go to: www.skretting.com

Adsorptech Pg.11

Advanced Aquacultural Technologies Inc. Pg. 25

AquaBioTech Group Pg. 17

Aquacare Environment Inc Pg. 18

Aquacultur Fischtechnik GmbH Pg. 21

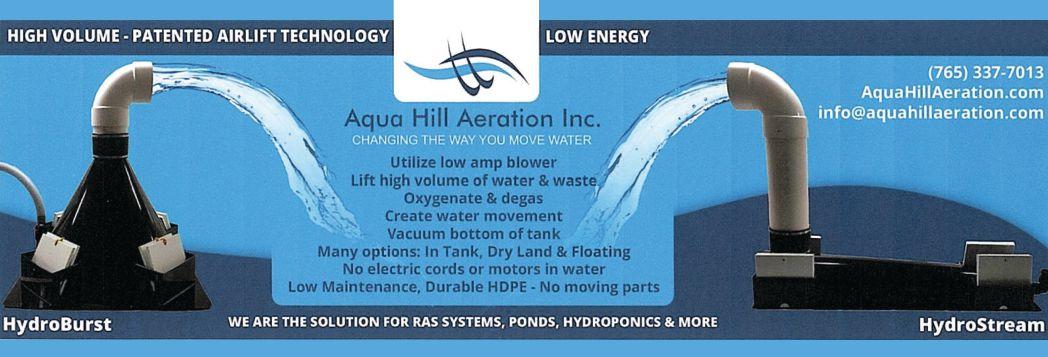

Aqua Hill Aeration, Inc. Pg. 27

Aqua Production Systems Inc. Pg. 14

Aquatic Equipment & Design Inc. Pg. 24

Arvotec Pg. 16

Benchmark Instrumentation & Analytical Services Pg. 7

BIO-UV Pg. 11

Cornell University Pg. 31

Faivre Sarl Pg. 15

Fresh By Design Pg. 16

Hatchery International Pg. 23

Hatchery International Pg. 29

Henry Aquaculture Consult Inc. Pg. 13

Lykkegaard A/S Pg. 28

MAT FİLTRASYON Pg. 22

MDM Incorporated Pg. 14

OxyGuard International Pg. 19

Pure Aquatics Pg. 24

SIVAT Services Pg. 29

Skretting North America Pg. 5

Trome Pg. 9

Veolia Water Technologies (North America) Pg. 32

Veolia Water Technologies ABHydrotech Pg. 21

YSI Inc. Pg. 2