The BuckwheaT

Crop rotation shows promise for managing wireworm.

Crop rotation shows promise for managing wireworm.

5 | The buckwheat effect Fine-tuning an important tool for wireworm control.

By Carolyn King

Treena Hein

Julienne Isaacs

By Rosalie I. Tennison

produCtion

Seed potatoes out of thin air

By Rosalie I. Tennison

LAw LAun

hes

By Julienne Isaacs

12 | Breeders, bees and serendipity

The origins of one of the world’s most important cultivars – russet Burbank.

By Carolyn King

Brandi Cowen, Editor

It seems consumers have a complicated relationship with biotechnology and genetically modified organisms (gMos) in the food chain. In January’s “We are What We eat: Healthy eating Trends around the World” report, the nielsen Company found 32 per cent of north american consumers rate gMo -free attributes as very important in their purchasing decisions. gMo -free is in a three-way tie with “made from vegetables/fruits” and “no high fructose corn syrup” for the top spot on a list of 27 attributes consumers are concerned about when choosing which foods to eat. nielsen also found 25 per cent of north american consumers are “very willing” to pay a premium for gMo -free foods.

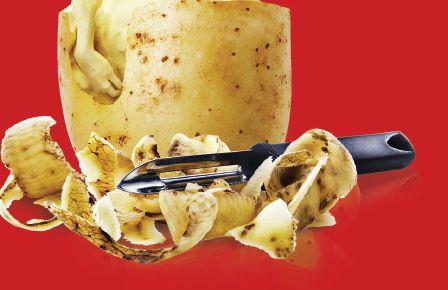

now consider this: new research from Iowa State University found consumers are actually willing to pay more for genetically modified potato products boasting low levels of a chemical compound that’s been linked to cancer in animals. acrylamide occurs naturally when starchy foods are cooked at high temperatures; potato products such as French fries and chips are a major source of acrylamide in the american diet. So far biotechnology and genetic modification have yielded more promising acrylamide reductions than conventional plant breeding techniques. In a study examining consumer willingness to pay more for enhanced food safety delivered through biotechnology, researchers found participants were willing to pay $1.78 more for a five-pound bag of potatoes after they received scientific information on health hazards associated with acrylamide exposure and a potato industry perspective on using biotechnology to reduce acrylamide in potato products. The study also found participants were willing to pay an extra $1.33 for a package of frozen French fries after learning about the scientific implications of human exposure to acrylamide.

What’s the potato industry to make of all this?

Speaking at this year’s ontario potato Conference, Joe guenthner, a professor of agricultural economics and rural sociology with the University of Idaho, made the case for using a “green gM” concept to market biotech potatoes. guenthner defined green gM as genetic modifications that use genes from within the potato family to create new varieties with desirable traits. This, he argues, makes a difference in the minds of many consumers: eating a spud with genes borrowed from a close relative in the potato family just doesn’t sound all that scary.

The J.r. Simplot Company is already using the green gM tactic to market the Innate potato, which offers reduced black spot from bruising and low asparagine, which reduces the potential for acrylamide formation. The company has been working hard to drive home messaging around the green gM concept. as its press releases reiterate, “Innate potatoes only contain genes from wild and cultivated potatoes, grow naturally just like conventional potatoes, and introduce no new allergens.”

That J.r. Simplot has been upfront about marketing Innate potatoes as a gM food will likely play well with consumers, many of whom support labeling of genetically modified foods. according to an associated press- gfk poll conducted last December, two-thirds of americans (66 per cent) reported they are in favour of requiring food manufacturers to put labels on products containing genetically modified organisms or grown from seed engineered in labs. Just seven per cent of american consumers are opposed to the idea. Today’s consumers are hungry for information about their food: where it comes from, how it’s produced and the footprint production leaves behind. as an industry, we shouldn’t be afraid to feed this appetite. organic farmers proudly share their stories with consumers; producers who use biotechnology to bring their crops to market shouldn’t be afraid to do the same. as the study of willingness to pay for low acrylamide potatoes demonstrates, information has a key role to play in consumer acceptance.

DIrECTOr Of SOuL/COO Sue fredericks

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 rETurN uNDELIVErABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIrCuLATION e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SuBSCrIPTION rATES

Top Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 2 issuesSpring and Summer 1 Year - $16 Cdn. plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top

www.topcropmanager.com

Fine-tuning an important tool for wireworm control.

by Carolyn King

Growing two years of buckwheat in a potato rotation is effective at managing wireworms, one of the toughest pest problems for potato growers. But how does buckwheat actually affect wireworms, and can we make buckwheat rotation even more effective and practical for growers? a rotational study is underway on prince edward Island to answer these questions.

The p e.I. study is part of a major project to investigate different strategies for dealing with wireworms, led by Christine noronha, a research scientist with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC). The project, funded by aaFC, involves aaFC scientists across the country because wireworms cause serious problems in many regions and many crops.

Wireworms are the soil-dwelling larvae of click beetles. Canada has about 30 wireworm species of economic importance. In most species, the beetles lay eggs in the soil in the spring. a few weeks later, the larvae hatch. The larval stage lasts about four or five years, depending on the species. Then the larvae pupate and the adults emerge from the soil in spring.

In potatoes, wireworms tunnel into the tubers, reducing marketable yield. The tunnels can also be entry points for potato pathogens.

noronha has been conducting wireworm research in p e.I. for over a decade. Her rotational studies show growing either brown mustard or buckwheat as a cover crop for two years before growing

potatoes can reduce tuber damage by about 80 per cent or more. Brown mustard is known to release chemicals into the soil that control wireworms, but the reasons for buckwheat’s effect on wireworms are not yet known.

aaFC research scientist aaron Mills is leading the new p e.I. buckwheat agronomy study. It is taking place at the Harrington research Farm and runs from 2014 to 2016.

“Christine noronha has done an excellent job at figuring out how to control wireworm with buckwheat; it’s now another tool in the toolbox for controlling wireworm. a big part of this new buckwheat study is to find out how and why buckwheat affects wireworms,” Mills explains.

“We also want to establish local protocols for how to deal with buckwheat in the rotation, so growers wouldn’t be as intimidated by the potential for buckwheat to become a weed problem, and to establish some protocols for managing buckwheat as a grain as well.”

Better understanding of how buckwheat impacts wireworms could potentially lead to advances that enhance wireworm control. For instance, one possibility is that buckwheat is releasing compounds into the soil that kill or suppress wireworms directly or perhaps affect other components of the soil ecosystem in ways that

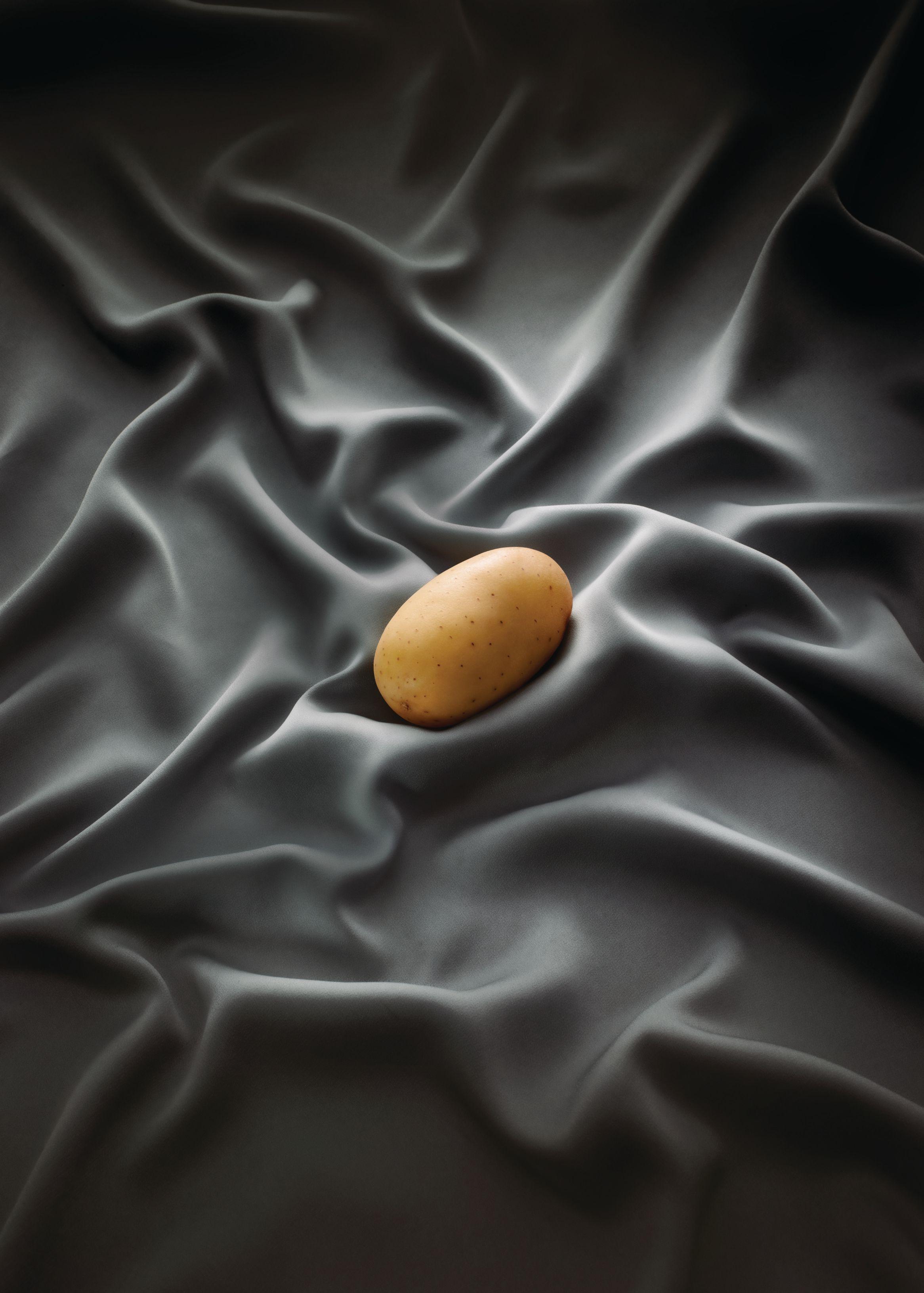

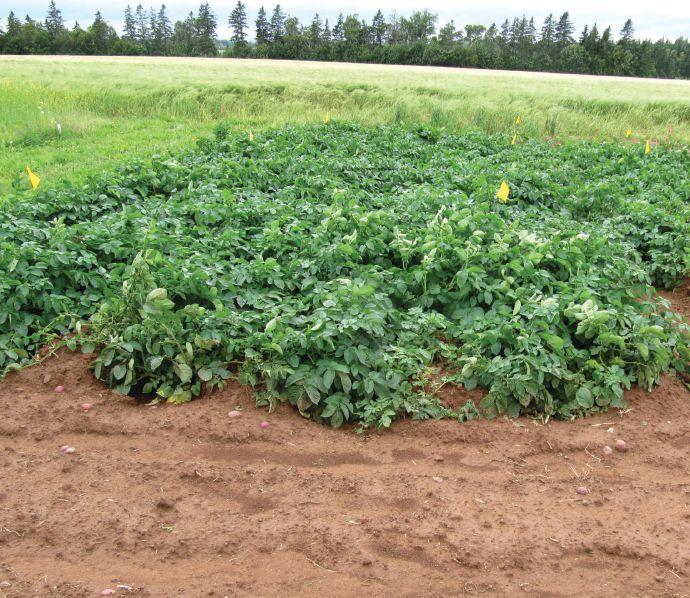

top: a new study at the Harrington research Farm in p e i. is examining how to make buckwheat crops an even more effective and practical option for potato growers looking to control wireworm.

make conditions less favourable for wireworms. If such compounds are released when buckwheat foliage decomposes in the soil, then the most effective wireworm control strategy might be to disk the plant into the soil as a green manure. or it may be best managed as a mulch, in which case flail mowing as a green manure may be best. If the compounds are released by the roots, then perhaps it might be better to let the buckwheat crop grow for a longer period before terminating it. If buckwheat produces compounds that deter other insect pests or pathogens, in addition to wireworms, then it could provide even greater benefits in the crop rotation. In the longer term, perhaps buckwheat lines could be selected that have higher levels of those compounds, or perhaps a bio-insecticide could be developed using the compounds.

Better understanding of how buckwheat impacts wireworms could potentially lead to advances that enhance wireworm control.

a key aspect of successfully including buckwheat in a crop rotation is to ensure volunteer buckwheat doesn’t become a weed issue.

“Traditionally buckwheat has been grown as a weed control measure, and some growers are concerned about growing it because it can become a weed itself if you let it grow too long and go to seed,” Mills says. He explains buckwheat grows very well in p e.I.; the seedlings emerge and grow quickly, enabling the crop to outcompete weeds. as well, some research indicates buckwheat releases chemicals into the soil that inhibit the growth of certain plant species. Those characteristics make buckwheat great at fighting weeds, but can also make volunteer buckwheat a problem for the next crop. although letting buckwheat go to seed is a weed risk, growing buckwheat for grain would be an important opportunity for growers to obtain some income from growing two years of buckwheat for wireworm control.

“right now I would say the majority of growers on the Island are growing buckwheat for wireworm control, but I think people are interested in growing it as a crop for grain as well,” Mills notes. “I think the main export market for buckwheat is for use in noodles in the asian market, although it has been grown in places like new Brunswick to make flour for buckwheat pancakes. and there may be opportunities in the health food industry; for example, buckwheat oil is reported to have some bioactive benefits.” Buckwheat also attracts pollinators and is used for honey production.

Wireworms, organic matter, microbes and more Mills’ study is comparing five different three-year potato rotations. Three of the rotations involve two years of buckwheat and are comparing three strategies for terminating buckwheat: disking, flailing, and desiccating and then harvesting it for grain.

“For termination through disking, we wait until the lower seeds start to drop off and then we use a set of disks to incorporate the aboveground crop material into the soil. For termination through flailing, we wait for the lower seeds to start to drop, and then go in with a flail mower and completely flail off the top of the aboveground biomass, leaving the residue on the top of the soil surface, almost as a smothering effect. and to manage buckwheat for grain, we desiccate the crop and then take it off with a combine,” Mills says.

He adds, “We wait for the lower seeds to start to drop off when

flailing or disking because we’ve found that buckwheat turns to jelly when you flail or disk it – the remaining residue breaks down fairly quickly. So rather than ending up with bare soil going into the winter, we wait for the lower seeds to start to drop off to make sure there will be a little bit of cover going into the winter.”

For the three buckwheat treatments, Mills’ research team is measuring factors like buckwheat biomass and seed yield, as appropriate.

The other two rotations in the study are traditional three-year potato rotations used in p.e.I.: barley underseeded with clover and then potatoes; and barley underseeded with a grass and then potatoes. These traditional rotations have benefits for soil conservation, but they favour the spread of wireworms because the beetles prefer to lay their eggs in grassy areas.

The researchers will be gathering data on such factors as potato yields and the levels of wireworm damage in the tubers for the five rotations.

as well, they will examine effects of the different rotations on water quality, soil organic matter content and soil nutrient levels, so nutrient management specialist Judith nyiraneza and water quality specialist Yefang Jiang are involved in the study.

“although any green cover on the soil helps to reduce erosion, the study will be examining whether or not buckwheat is particularly good at preventing erosion or building up soil organic matter,” Mills says. “I think the jury is still out on whether buckwheat is a soil builder or not.”

Buckwheat’s effect on soil nutrients also needs to be clarified. Some previous research has suggested buckwheat may make nutrients like phosphorus more available to the next crop, while other sources suggest buckwheat may reduce levels of certain nutrients.

To better understand how buckwheat controls wireworms, Christian gallant, a graduate student from Dalhousie University, is looking at the soil organism communities in the plots, especially the nematode communities, and also the fungal and bacterial communities. He will be examining how species diversity and populations change through the course of the growing season and with the different crops.

Mills explains the value of examining nematode communities: “Most people focus on the plant parasitic nematodes. Those nematodes feed on plant roots, and the damage from their feeding also opens up spots for pathogens like Verticillium to enter the plant’s root system. But there is a whole other side of the nematode community. They all have specific jobs to do; there are bacterial feeders, fungal feeders and predators that feed on other nematodes and even mites. By studying the overall nematode community, we can get a snapshot of how things are happening biologically in the soil.”

In addition, researchers will be testing the soil for buckwheat compounds that could be affecting soil organisms. “We’re trying to figure out if buckwheat is actually releasing chemicals into the soil that are affecting the soil pest populations, or if buckwheat is just a non-host for some of these pests,” Mills says.

With one field season completed so far, Mills is looking ahead to the results from 2015 and 2016. “By the end of 2015, we’ll have a really good idea of how the different buckwheat treatments affect soil organisms, nutrients and organic matter, [and water quality]. and by the end of the study’s third year, we’ll have an excellent idea of how everything affects potato production.”

In the meantime, growers are welcome to visit the Harrington research Farm to see the plots and learn more about the study.

Irrigation equipment adjusts to put water and fertility variably across field.

by rosalie I. Tennison

Rain is indiscriminate when it falls from the sky; Mother nature doesn’t ignore low spots on fields just because they don’t need moisture. But for potato growers, technology is making it possible to even out moisture levels to allow for more equitable crop development. no more do pivots have to circle the field, applying the same amount of water on every sector whether it be a drier hilltop or a moisture retaining former creek bed.

although not new technology, a nebraska company’s Variable rate Irrigation (VrI) system is gaining notice in Canada. Valley Irrigation advertises that VrI will “make all areas in your field profitable, reduce runoff, and increase water and chemical application efficiency.” The company also says the equipment is relatively easy to use and will make managing irrigation less stressful.

However, a grower who has been using the system on his alliston, ont. farm for two years now claims there is still much to learn and understand once the equipment is installed. adequate rain during the two years since he began using the equipment did not give Homer VanderZaag the opportunity to fully experience the VrI technology.

“I know there will be a value in using this system, but the last couple years have been wet, so we didn’t see the full benefit,” VanderZaag admits. “our first measurement of success should be yield improvements across the field.” He explains the system allows growers to divide a field into zones and a computer program can tell the pivot when to apply moisture in a zone. Fertigation can be controlled in the same manner, and late blight and tuber rot can also be better managed in years when the crop receives irrigation exclusively.

James Wolsky of K & T Irrigation in West Fargo, n.D., sells Valley’s VrI technology and he understands what VanderZaag has been facing, but he also sees the equipment helping in wet years as well. “We’ve been in a wet cycle for many years here, but we see the variable rate irrigation helping to control excess moisture,” he explains. “our customers are not putting water on where it isn’t needed. We know every field is not the same, so we use the variable rate technology to prevent over-watering potatoes.” even in wetter years there might be periods where some moisture is needed on higher zones, and the pivots can be programmed to water where needed while leaving the lower spots alone.

“The hard part with VrI is writing the prescription for the pivot,” VanderZaag admits. “You take what you know about the field and translate it into a map that represents the needs of the field. You can overlay maps to help, but you need good aerial imagery and topography knowledge. It can be daunting.”

VanderZaag says soil test results help with fertigation, but there is no tool that estimates how much moisture is available in the soil. He feels knowing moisture levels for the various zones would make it easier to program the equipment and to manage water more effectively. He also says VrI would be most useful to growers who have many zones across a field, from highs to lows; a perfectly flat field would, conceivably, require the same level of moisture across all zones.

Wolsky agrees. “We have an example of a grower who has a sand ridge in a field, so he’s not putting water on the lower, wetter, heavier soils, but only on that ridge.” By using the variable rate technology, he says, there can be a savings in water use, and the equipment can also be set to a variable frequency drive to put more water where it is needed most.

according to Valley Irrigation, VrI can save water because only the amount of water that is needed will be applied. By changing the application depth, run-off can also be reduced and over-watering will not be an issue. There are two types of VrI available – speed control of the pivot as it crosses the field, and zone control that allows for fine-tuning the amount of moisture given to the crop. The company literature says the zone-control technology is most helpful in challenging fields divided into more than 5000 zones. The speed control programming works best when the field variability can be captured in pie-shaped wedges.

VanderZaag says in his most complex field, he has 2700 zones with his 1100 foot pivot covering an 80 acre circle. He explains he can set the equipment to irrigate more frequently knowing that each acre is getting the correct amount at any given time. High sandy spots receive more water, while low areas can be limited or even left dry as insurance against large rain events. He believes his average yield will improve overall with regulated moisture. plus, disease and pests will be managed more effectively.

“This is amazing technology and, once the programming is done, it is easy to use,” VanderZaag says. “It was a challenge at first, but it’s a great opportunity to improve our crop output. I like the fact that I can manage my crop’s moisture more effectively.”

VanderZaag did a retrofit on existing equipment to install VrI, but complete systems can be purchased with the technology in place on the pivot. Then, all a grower needs to do is input the field’s “personal” information into the computer program.

not all fields are the same, but variable rate irrigation technology offers growers multiple options for managing moisture. When Mother nature isn’t hitting the high spots adequately, VrI can make up the difference.

With organic potato production on the rise, new research analyzes economic returns.

by Treena Hein

It’s no surprise the demand for organic potatoes is growing in north america and beyond, as demand for all types of organic food is on the rise. Canada’s organic potato acreage is increasing to meet the demand, but there has been little Canadian research to date on the agronomy or economics of organic potato production.

Studies from the United States have found that organic production with well-managed crop rotations can be just as – or more – profitable than conventional potato production systems. While rotation is a key integrated management technique, others include fertility management from organic sources such as manure and compost, alternative pest control, and weed management via mechanical cultivation or flaming.

To investigate further, a team at the a griculture and a griFood Canada ( aa FC) Harrington research Farm in prince e dward Island have completed a four-year study comparing the economic performance of seven different four-year organic potato rotations to a conventional potato rotation. The trial lasted from 2008 to 2011 and the results are just now being published, says roger Henry, the senior technician involved with the project. “Seven organic rotations were developed with various crop combinations to help control pests and soil-borne diseases, and to maintain nutrient levels,” he notes. “ e ach rotation included at least two cash crops during the four seasons and two different pest/disease-suppressive crops, including

brown mustard and buckwheat for wireworm, pearl millet and alfalfa for nematodes, canola and winter rape for rhizoctonia and sorghum sudangrass for verticillium wilt.”

The study results confirm what has been found in other studies elsewhere: despite lower tuber yields, organic potato production generally results in higher net revenues than a conventional potato system, mainly due to the high price premium received for organic potatoes and other organic crop products in p e .I. However, the net revenues are not significantly higher.

“The rotation with the highest return in this study included carrots (potato, mixed grain, carrots and pearl millet),” Henry says. “However, while the yield and net revenue of the carrots boosted the overall revenue of that rotation, the yield and the net revenue for carrots was the most variable of all the crops studied. That’s something to think about.”

and while Henry’s study results point to organic potato farming as a viable business under the current price premium, he says the results also show conventional potato systems could produce similar economic benefits to organic when a traditional three-year potato-cereal-green manure rotation is used. “That’s assuming they continue to get good yields with

aBoVe: a new three-year trial will evaluate which new technologies work best in organic crop cultivation in terms of weed control, nutrient management and pest and pathogen control.

three-year rotations, which does not always happen, and that yields of the organic potatoes stay at 60 per cent of the conventional,” he explains. “I believe we can achieve yields at least at 75 per cent of the conventional yield and more during some years, if we choose the right varieties and perfect our management of the crop while it’s in the ground. If we achieve these yields, then conventional three-year rotation will not be as profitable as a four-year organic one.”

“This transition period is hard from a financial perspective, which is one of the reasons some producers are hesitant to go organic,” he says. “There is also more extensive management associated with organic production, with new skills to learn and knowledge to accumulate compared to conventional. There are also very few people one can talk to about production issues.”

more productive and that would reflect in higher cash crop yields overall.”

“There is also the possibility that if not managed well, soils could become depleted of certain soil nutrients, and increased pest problems [could occur] in certain rotations,” he adds.

new research

a three-year organic study was undertaken this year in p e .I. to evaluate which new technologies work best in organic crop cultivation, including potatoes. The trial is examining nutrient management as well as weed, pest and pathogen control, with an eye on economics. It includes more cash crops than the 2008 to 2011 trial, and is focused on developing cropping guidelines for no-till soybeans, silage, grain corn, edible beans and squash as well as potatoes.

“ nitrogen and phosphorus are two essential nutrients which tend to be most limiting in organic systems,” says Vernon rodd, who is heading the study with a aron Mills at aa FC Charlottetown. “We are using anion exchange membranes to track nutrient availability during the growing season for a number of crops including forages, potatoes and corn.”

The team is also analyzing phospholipid fatty acid profiles in soil samples to measure the makeup of the functional soil community under the various rotations. In addition, the study includes a look at various organic weed control options, including flaming, mechanical control and timing of the cultivation.

“a s organic demand continues to grow, we hope to provide more information on the economics and best practices,” Henry says. “ potato growers can use this, and other, information to decide if organic production is something they want to pursue.” research revealed conventional potato systems, such as

Henry also stresses during the transition to organic certification, financial losses can occur because yields are lower and the producer does not have the benefit of organic price premiums until they are certified.

an important caveat to this study is that it occurred in the first four years after full transition to organic was achieved.

“It’s possible that differences observed in the first four years may not reflect longterm crop performance,” Henry explains. “generally over time, if the soil is managed well, organic soils will become

Checking in on an aeroponic project that could change the future of seed propagation.

by rosalie I. Tennison

Mystery surrounds animals, people or things that appear out of thin air and movies scare us with a villain appearing out of the mist. But there are some very positive and non-threatening aspects to using thin air and mist in potato production. With the support of alberta potato growers, Michele Konschuh may have fine-tuned a better, more efficient, financially viable means to produce seed potatoes.

Konschuh, a potato research scientist with the Crop Diversification Centre in Brooks, alta., has used aeroponic technology to produce seed potatoes in a chamber that only requires the roots of the plants to be misted regularly. The p I p 200 potato Incubator was shipped to Canada from northBright Technologies in Chicago. The company had previously developed a prototype called the p I p 100, but having heard about the system, seed growers in alberta were keen to try the technology. The p I p 200’s arrival posed some challenges.

“We had to put the equipment together when it arrived,” Konschuh says, because there were no precise instructions for something that was still in development. Then, she and her team had to figure out how the equipment worked. “The first crop was humbling and we planted it in winter, which was not the best scenario, because we struggled to get the roots developed.”

The aeroponic system includes three chambers stacked on top of each other. The top chamber is open to the greenhouse and the tops of the plants grow upward into carbon dioxide and sunlight. The middle chamber hosts a plug that holds the tissue cultured plantlet. o n the bottom is a fabric layer the roots push through into a dark, open area that is misted to feed the

aBoVe: the aeroponic system includes three stacked chambers. the top chamber is open to the greenhouse, the middle chamber hosts a plug that holds the tissue cultured plantlet and the bottom layer offers a dark, misted area to feed the plants.

plants and keep them alive. The learning curve was not smooth, but jagged, as the team had to learn how to set up the chambers. The fabric the roots needed to push through was inadvertently substituted for something too heavy. preventive maintenance procedures were learned through trial and error. Watering issues also became a challenge because, like any field situation, too much or too little stresses plants, causing yield and quality issues.

“We don’t know much about growing potatoes ‘in captivity,’” Konschuh says. But, faced with a tight schedule, she and her team were able to produce four crops of seed potatoes and each one was more successful than the one before.

“The potato growers did not expect this to be a long-term project, it was merely designed to assess a potential commercial unit,” Konschuh says. “We learned more each time we grew a crop, but we didn’t solve fertility issues and we need to understand root systems better.”

The provincial government recently purchased the pIp 200 and, on recommendations by Konschuh, the manufacturer is making adjustments to create the pIp 150 that will be more “user friendly.” She says the assessment did remove some of the risk that commercial seed potato growers would face if they decide to use the equipment themselves. In the four crop trials, she learned the system does work and that it can be economically viable.

after the first couple “less than stellar” crops using the equipment, the researchers learned and improved, hitting a high of 15 to 20 marketable seed tubers per plant. But, Konschuh admits, in the last trial only one variety was grown. In the first round, 14 varieties were grown and, she explains, each variety had its own idiosyncrasies, making it difficult to manage the fertility and water requirements to ensure each crop was managed successfully.

“We increased yield 10 times over what can be done in a greenhouse using traditional production methods,” Konschuh says. “We used less nutrition and water to produce the seed as well. The cost of producing seed potatoes was reduced based on

lowering our variable cost per tuber. I think, realistically, a seed grower using this system could pay it off in about five years.”

The cost of production, according to the researcher, was 35 cents per tuber compared to the usual 75 cents accrued by the average grower. The team was able to grow some of their production in a field with no apparent differences when compared with traditionally grown seed. However, Konschuh suggests, the cost of seed will most likely not be lowered, but the availability of seed would ensure the province’s seed potato supply.

While the future of seed production in an aeroponic system appears very positive, there is still much to learn and Konschuh admits that it is a less forgiving system than hydroponics. “With aeroponics, you only have about three hours to save the crop if your water pump quits,” she says. “You also need good light and we need to understand fertility and manage plant density better.”

even though Konschuh no longer works directly with the pIp 200, she sees many possibilities to use it as a research tool to study how tubers develop in the field, to understand how root systems feed plants, and to learn how to better control diseases.

Finally, the assessment of the pIp 200 is offering seed growers a new option and, with proof the system is viable and cost-effective, the future of seed production in alberta could be changed. Konschuh believes what she was able to accomplish in only four crops is giving growers enough information to make informed choices about whether to take the leap and purchase the equipment. In the near future, producers may be growing tubers out of thin air in a misty environment and that’s not the least bit scary.

The wait is over! We’re proud to reveal this year’s group trip is to two world-class cities: Rome and Florence. Let Italy sweep you off your feet with its architecture, museums, and of course, delicious cuisine. Just remember your camera... and all those rewarding Hot Potatoes points that you can redeem for the group trip or cash. Visit Hot-Potatoes.ca or call 1 877-661-6665 for more information.

by Carolyn King

Arecent project has corrected misinformation and filled information gaps about the origins of russet Burbank. It provides crucial genetic information for potato breeders, along with a remarkable tale about how russet Burbank has come to be a global success.

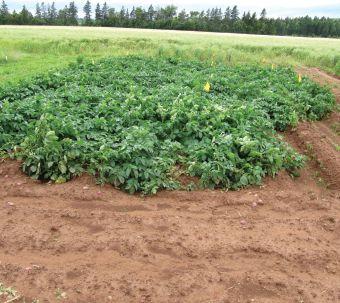

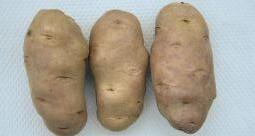

“ russet Burbank is now the most important potato cultivar in the world. It is the number one processing cultivar in Canada, the United States and the netherlands, which are the top three frozen French fry-producing countries. It is number one in e urope, north america, and australia and new Zealand, and it’s right up there in parts of India and China,” says Danielle Donnelly, associate professor in the plant science department of Mc g ill University. “I find it astonishing that a cultivar with origins in the 1890s could still be so important today.”

Donnelly’s research usually focuses on genetic improvement of potato cultivars, but during a sabbatical a couple of years ago at the potato research Centre of agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC), she started putting together the story of russet Burbank. She soon brought in others to help her with the project, including people from the United States Department of agriculture (USDa), Mcgill, aaFC and McCain Foods Canada Ltd. She notes, “It took a big team to pull all the information together.”

russet Burbank comes from a line of important cultivars with beginnings in the 1850s. at that time, the potato industry was reeling from the disastrous impacts of late blight, which resulted in the devastating Irish potato Famine, lasting from 1845 to about 1851. Many of the potato varieties at the time were susceptible to late blight, so breeders and botanists were scouting in South and Central america for potato lines that might have late blight resistance. rough p urple Chili was one of several South american genotypes brought to the U.S. through the panamanian e mbassy. The amateur botanist C. e g oodrich tested these lines and selected rough p urple Chili (released in 1851). The cultivar was thought to have come from Chile (which was spelled “Chili” at the time).

rough p urple Chili was the parent of g arnet Chili (released in 1857). and from g arnet Chili came e arly rose (released in 1867). These cultivars are very important in north american potato genetics. “In the 1990s, Dr. Stephen Love looked at the genealogy of the top 44 cultivars in the U.S. at the time. He

the 1902 catalogue from l l. May & Company in which russet Burbank (netted gem) first appeared.

found that g arnet Chili and e arly rose were in the ancestry of all [of] them,” Donnelly says. “It is amazing how small the genetic base is.”

From e arly rose came Burbank (released in 1876), which was named after its breeder, Luther Burbank. a s a young man, he made a selection from e arly rose plants in his mother’s garden and came up with Burbank. Then from Burbank came russet Burbank (released in 1902).

according to Donnelly, the cultivar Burbank was a noticeable improvement over its progenitors. “g arnet Chili is a small, roundish red potato; it is sort of smushed in, almost pointy on one side. e arly rose was considered prettier, with its pinkish colour, and it is longer, bigger and easier to peel than g arnet Chili. Burbank is even bigger and nicer looking than e arly rose, and it could be used for both baking and boiling.”

Luther Burbank sold his Burbank cultivar to a seed company, Messrs. g regory and Son, but the company let him keep some. Donnelly says, “He went to southern California and started propagating and distributing the cultivar there. a very early USDa , which was just being formed in those days, started promoting the cultivar to all of the potato-growing areas in the U.S. Within just a few years, Burbank was being grown from Mexico all the way up to alaska.”

o ver the following years, various people noted some Burbank tubers had a russet skin. an incorrect but well-known account attributed the discovery of this russeted type to Louis D. Sweet, a Colorado potato grower, in 1914. However, the USDa’s paul Bethke, who was one of Donnelly’s collaborators on the project, worked with several librarians to look through early U.S. seed catalogues. They determined russet Burbank was probably originally released in 1902 as May’s netted g em by L. L. May & Co. The names netted g em and russet Burbank were often used interchangeably for this cultivar during the next few decades.

genetic relations

“o ver the years, many people have tried to figure out the relationships between rough p urple Chili, g arnet Chili, e arly rose and Burbank. The breeders of these cultivars each thought the cultivar they had grown in their garden or field had [selfpollinated] and that they were collecting seeds that were ‘selfed’ or inbred,” Donnelly says.

“But all the [genetic] evidence shows these cultivars were actually pollinated from outside. potatoes are bee pollinated, which tells us those bees really got around, no matter how

isolated the breeders thought their fields were. So g arnet Chili, e arly rose and Burbank are hybrids. That was shown in the 1990s through isoenzyme work, and then it was shown again and again through genetic studies and very sophisticated molecular studies.

“These same molecular genetic studies find no difference between Burbank and russet Burbank, even though the skin is shockingly different. So russet Burbank is a ‘sport,’ or a mutation, of Burbank,” Donnelly adds.

Thus, as a result of the information brought together in this project, seed companies and germplasm repositories can correct their information on russet Burbank and its progenitors.

“Breeders need to know how these particular cultivars were produced because the cultivars have been so successful,” Donnelly explains. “If breeders mistakenly thought these cultivars were selfed, they might continue to self them to try to find improvements, when really the breeders should be finding out what the male parent was from the pollen coming in. That is really critical information for a breeder.”

During the early 1900s, russet Burbank gradually replaced Burbank in popularity. o ne reason was because people tended to prefer its russeted skin to the thin skin of Burbank. “When russet Burbank first came along, people were still recalling the Irish famine, and they assumed a potato with a thicker skin would more likely resist late blight. That thicker skin probably does help protect the tuber against a number of bacterial and fungal issues,” Donnelly says.

another important factor in russet Burbank’s early success was that Idaho started to promote the cultivar during this same period. She notes, “ people in Idaho were trying to find something that would really identify their state and their potatoes. russet Burbank was a nice-looking potato that grew well for their growers, so they made the cultivar their signature potato, increasing its fame and widespread use.”

a s well, the railways publicized the cultivar. “The stories go that some russet Burbank tubers were so big that they caused problems for the growers because people didn’t want to buy potatoes that were as big as your head. However, someone who was procuring food for the new railways at the time heard about these big potatoes and started serving them on the railway and heavily promoting them as a special treat,” Donnelly says.

a further boost to russet Burbank’s prominence came in the 1940s, with the growth of fast-food franchises in the U.S. “Who would have known those fast-food franchises would take off like a rocket? Those franchises are fuelled by French fries and burgers. So French fries took off, and frozen French fries became important to distribute to restaurants and to the army during the war,” Donnelly says. “The big, blocky russet Burbank tubers are perfect for frozen French fries because there is not too much waste, the fries are long, and you can make them in different widths depending on your interest. p lus they have a great taste and fry beautifully, and the tubers store very well.”

The combination of certain traits that make russet Burbank especially suited to French fry production is another lucky happenstance. Xiu-Qing Li, an aa FC researcher involved in

Continued on page 17

A

by Julienne Isaacs

During the 2014 growing season, a new late blight spore-trapping project was initiated in alberta that may offer growers another tool for delaying the spread of late blight in the province.

Melanie Kalischuk, an instructor at Lethbridge College, says the study was designed to provide alberta growers advanced warning about the presence or absence of Phytophthora infestans, the pathogen that causes late blight. In Western Canada, late blight can occasionally cause devastating losses for potato and tomato growers.

according to Kalischuk, P. infestans has two mating types. If both are present in a region, sexual reproduction of this pathogen can occur and this can result in genetic recombination. “We are lucky in alberta because presently we have only one of the mating types,” she explains.

The sexual form of the pathogen, known as an oospore, also has the ability to survive in the soil for many years, complicating management control practices. “Therefore, we want to avoid sexual reproduction of this pathogen,” Kalischuk says. “avoiding the occurrence of both mating types in the province is important.”

P. infestans requires a living, unprotected host, as well as precise environmental conditions, including moisture and lower temperatures, for infection. as part of this pathogen’s complex life cycle, it produces a spore type referred to as “sporangia.” Sporangia is usually spread via living infected plant tissue in fields, cull piles or weeds. “Sporangia can also become airborne, allowing us to monitor for the occurrences of this pathogen by taking air samples,” Kalischuk says. “Last summer, a series of eight volumetric spore traps were set up in strategic locations throughout the province to monitor air samples for the spores causing late blight disease.”

The study was headed up by Kalischuk and students at Lethbridge College, with assistance from Michael Harding and ron Howard with alberta agriculture and rural Development at Brooks, and Lawrence Kawchuk at agriculture and agri-Food Canada’s Lethbridge research Centre. Funding for the study was provided by potato growers of alberta (pga), alberta Crop Industry Development Fund, Cavendish Farms, Lamb Weston and Crop production Services. The pga also supported the study by disseminating spore-trap counts to growers in real-time.

Kalischuk and her team set up two types of spore traps – a rotor rod trap, which had to be checked daily, and a UK-made trap called a Burkard 7-Day recording Volumetric Spore Trap. Burkard traps are lightweight units that contain built-in vacuum pumps to sample airborne particles continuously, with the particles adhering to coated tape on a clockwork-driven drum inside the unit. Traps can be left for up to seven days before they need to be checked by researchers.

The traps were set up at the edges of farmers’ fields, or just west of fields, because late blight spores tend to travel east to west. The researchers found that once spore levels spiked in the traps, they had about a 10- to 16-day window before late blight appeared in nearby fields.

“although this study is in its early stages and more testing is required to quantify pathogen load, last year we were able to observe an increase in the number of air-borne sporangia that correlated with an infection in the field that appeared 10 to 16 days later,” Kalischuk says.

Terence Hochstein, executive director of the pga, says the study did exactly what they’d hoped it would: it provided growers with an early warning about the advancing spread of P. infestans so they could tighten up their existing spray programs and stay ahead of the pathogen. “We first had a major detection of the traps on about July 20. our first reported incident was aug. 5,” he says.

But Kalischuk says the benefit of the study goes beyond immediate payoffs for growers. “another important component of this study is to identify hot-spots for infection and then to educate people in these areas on practices that can help eliminate late blight,” she says. “a number of years ago, alberta potatoes had an economic advantage because late blight was rare in the province. With this project we are helping to bring back the alberta advantage.”

The project will also help growers design more effective management regimes, Kalischuk claims. growers have to watch environmental conditions to stay on top of late blight management, but the late blight spore-trapping project will deliver concrete data about pathogen pressure. “Typically the best strategy to reduce the chance of getting late blight is to remove cull or compost piles, where the pathogen can live, and avoid planting infected seed,” Kalischuk says. “now, with this additional information about the pathogen, farmers will also be able to use preventative rather than reactive fungicide spray programs.”

With one year of positive results, Hochstein and Kalischuk are looking ahead to the future. The project will continue this year, with support from new industry partners, as well as an expanding network of interested growers. Hochstein says there is demand for the spore trap information to become even more readily available to growers.

He underscores the importance of the project in giving growers a measure of control in late blight management, echoing Kalischuk’s claim that it offers a preventative, proactive approach to late blight.

“We’re constantly looking for ways to reduce or eliminate late blight in alberta. our growers – and the entire industry – are very proactive with that. It’s a community disease and we’re doing our best to fight it.”

by Julienne Isaacs

Small potato production is expanding in Saskatchewan to meet increased market demand for “creamer” potatoes with a target size of 20 mm to 40 mm in diameter. Specialty potato companies, such as The Little potato Company of edmonton, have found new culinary markets for so-called “little” potatoes. now growers in Saskatchewan are taking notice, particularly in the irrigated region of outlook.

However, small potato production is markedly different from conventional potato production and has a unique set of requirements, including suitable varieties, special equipment and agronomic practices that differ from large potato production in several key ways. according to Jazeem Wahab, horticultural crops agronomist at agriculture and agri-Food Canada’s (aaFC) Saskatoon research Centre, small potatoes are emerging as a higher-value option for the producer and another culinary choice for the consumer. However, growing small potatoes presents challenges to growers. “We have to develop cost-effective agronomic production practices that can produce the size and grade of small potatoes the market demands,” Wahab says.

Since 2006, Wahab has headed up a long-term study analyzing the effects of seed tuber size, seed spacing and harvest timing on growth and yield of small potatoes in Saskatchewan. He says many factors influence production of high-quality small potatoes, including weather, irrigation, harvest timing and variety. “not one factor operates independently – we have to take a holistic approach,” he says.

The project received support from Saskatchewan’s agriculture Development Fund from 2007 to 2009, as well as some funding from The Little potato Company. Wahab hopes to continue the study this year with aaFC funding.

according to Saskatchewan’s Ministry of agriculture, the project was initially aimed at “finding the best small potato germplasm and developing cost-effective and cultivar-specific agronomic practices for producing small potatoes,” as well as determining the potential for producing small potatoes from commercial table potato cultivars.

Studies under the project’s umbrella included the screening of creamer clones developed by aaFC potato breeders and identifying commercial potato cultivars suited for small potato production.

The project aims to benefit Saskatchewan’s potato industry by bringing greater revenue to the province’s producers through the higher-value small potatoes, which also increase the accessibility of lucrative urban markets. Small potato production is also more costeffective, as small potatoes are harvested earlier than conventional large potatoes, and thus require fewer inputs such as pesticides.

Wahab and his team of researchers analyzed the impact of seed tuber size, seed spacing, harvest and top kill timing under irrigated conditions on three proprietary small potato varieties – Baby Boomer, piccolo and Blushing Belle – as well as a few commercial and table standard large potato varieties, including aC peregrine and norland.

In one study, six seed tuber sizes were used in the study’s treatments, ranging in size from as small as 20 mm to as large as 50 mm in diameter. “In general, we found the larger the seed tuber, the bigger the yields,” Wahab says. Larger seed tubers also tended to decrease tuber size.

Two seed spacings were studied: 15 cm and 20 cm, respectively, between seed piece plantings. In general terms, closer spacings resulted in higher marketable yields, although Wahab says more data is needed. “I’ll be working on consolidating data from the years of the study to come up with recommendations,” he says. “What I can say is that some years, closer spacing yielded significantly higher, and some years it did not. The year that it did not respond well, it was very hot –weather can have a significant impact.”

In another study focused on harvest timing, one top-kill stage was used in the first year, based on tuber development of the different cultivars. Three top-kill stages were used in the second year, at 10, 11 and 12 weeks after planting.

Wahab says harvest timing depends on variables such as weather, but harvesting after 10 weeks usually results in a reasonably good small potato yield. “a nine-week harvest results in very low yields, a 10-week harvest in fairly good yields. at 11 weeks you get some larger potatoes, depending on the variety,” he says.

The team also studied the effects of harvest timing on some standard commercial varieties, such as norland and aC peregrine red potato varieties. What they discovered was aC peregrine could also be grown for the small potato market if harvested early. But even though such adaptability would seem to make varieties like aC peregrine attractive for commercial growers hoping to break into the small potato market, Wahab says most growers cannot afford to grow potatoes for both markets, as small potato production requires specialized equipment.

Before small potato production can grow into a major player in Canada’s potato industry, more suitable varieties will be needed, Wahab says. “The traditional varieties that are grown on a commercial scale have been bred to grow large. The number one thing we need is the best varieties for this particular purpose.”

Wahab believes small potatoes have a bright future in Canada, even though small potato production is still considered “niche.”

Continued from page 13

From Potato Gene Resources, Issue 20, 2013, with permission of Danielle Donnelly.

Rough Purple Chili

Imported from South America, C.E. Goodrich (1851)

Open pollinated – unknown if self-set or hybrid

A. Garnet Chili

C.E. Goodrich (1857)

Open pollinated – outcrossed (hybrid)

B. Early Rose

A. Bresee (1867)

C. Burbank

L. Burbank (breeder)

Messrs. J.J.H. Gregory & Son (1876)

Open pollinated – outcrossed (hybrid) Mutation (sport)

D. Russet Burbank (Netted Gem)

L.L. May & Company (1902)

the project, pointed out Burbank and russet Burbank have “the most extraordinary collection of recessive traits,” Donnelly says. “Such a combination of recessive traits is unlikely to happen very often, and yet all of those characteristics – the tuber’s elongated, blocky shape, large size, very shallow eyes and not very pronounced eyebrows – help make the tuber particularly valuable in the frozen French fry industry.”

a further reason for russet Burbank’s ongoing success is familiarity. “When people taste French fries in one of the many franchises, they develop a sensory image of what a French fry should be like. russet Burbank has set a standard for French fry taste and texture,” Donnelly explains. “and then there’s the accumulated expertise in growing, storing, processing, transporting and cooking russet Burbank French fries, ensuring a very reliable, very delicious product.”

russet Burbank’s excellent storage qualities are also very important. “I visited Cavendish Farms one summer in July. They had mountains of [russet Burbank] potatoes to process and they had done their million pounds and more for that day,” Donnelly says. “[processors] need tubers that store extremely well because they have to be able to process them until the next crop comes in, in the fall.”

These days, the vast majority of frozen French fries in the U.S. and Canada are made with russet Burbank.

Looking back to the origins of russet Burbank, Donnelly thinks of Luther Burbank. “His cultivar Burbank was his first discovery, and it turned out to be his most enduring and most important one. However, he is credited with introducing between 800 and 1000 plants to american horticulture, which is hugely impressive. although he won some awards, he did not receive the respect of his plant breeding peers because he was very unconventional – he wasn’t a scientist, [and] he used intuition and logic and experience to make his decisions,” she says.

“When Luther Burbank produced his cultivar, there was no such thing as plant breeders’ rights and no royalty stream. These days, if he produced such a remarkably popular cultivar, he would be a very wealthy man. and when his cultivar Burbank mutated to become netted g em, or russet Burbank, that would have belonged to him as well because today if you own a cultivar and register it under your name and it mutates, you are owner of that mutation, even if someone else finds it. If Luther Burbank were alive today, the knowledge that his potato cultivar is the most important in the world would make a big difference to his success as a breeder and to the respect he got as a breeder.”

There’s

been a lot of talk about food and farming lately – online, in the media and at the dinner table.

That’s a really good thing. It means people are concerned about their health and wellbeing, and that they’re in a position to make positive choices about what they eat. It also spells opportunity for Canada’s agriculture industry. What we do has never been so important to so many people here at home and around the world.

Unfortunately, too many of these conversations are generating false perceptions about what we produce and how we produce it. That’s often because for all the people talking about food, too few are actually part of the agriculture industry. And if we’re not telling our story, someone else will. The good news is, it’s not too late – and we’ve got lots of positive news to share.

Canadian agriculture is remarkably diverse and dynamic. Yet for all the change

the industry has seen over the years, one important constant remains: the family farm. In fact, 98 per cent of Canadian farms are family farms. That’s a key part of the conversation, because from the ground up, what we eat every day is produced by people who want the same things all families want: safe, nutritious food. Those same values also extend to how our food is produced. Canadian farms produce more than ever in ways that are more sustainable than ever. What a great legacy for future generations!

You’re an important part of the conversation. So speak up – tell the real story.

Canadian agriculture has a lot going for it, and sharing the facts is a great way to join the conversation. Our resource section is filled with timely, interesting content – including dozens of easy-to-share fact photos. And each one tells an important story. Here are just a few:

Source: CropLife Canada

Canada’s opportunity: world food demand is set to grow 60% by 2050

The world is growing, and everyone deserves to have access to safe, high quality food. It’s a huge responsibility and an incredible opportunity for Canadian agriculture. Canadian farmers are responding by producing more food than ever, all while using fewer resources. That’s good news here at home and around the world.

Thanks to Canada’s ag and food industry, more than 2.2 million Canadians are bringing home the bacon (pardon the pun) every day. That’s like the entire population of Vancouver. The impact on Canada’s economy, and on our communities and families, is truly remarkable.

Never has Canadian agriculture offered more – and more diverse – career options than right now. There are opportunities in research, manufacturing, financial services, marketing and trade, education and training, and more. And all of these positions need to be filled by talented, energetic people. Visit the website and consider what the facts mean to you. Then join the conversation! AgMoreThanEver.ca

Joining the ag and food conversation isn’t always easy. What you say is important. So is how you say it. If you’re feeling a little unsure about what to do next, you’re definitely not alone. Fortunately, we’ve got practical expert advice to help you become an effective agvocate.

Our online webinar series brings recognized experts in communication, social media and media relations right to your screen. Topics include:

• The art and science of the ag and food conversation

• Social media 101 for agvocates

• Getting in on the tough conversations

• Working with the media as an agvocate

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca and click on Ag Conversations.

Looking to channel your passion for ag? Adding your name to our agvocate list is a great way to get started. You’ll join a community of like-minded people and receive an email from us every month, with agvocate tips to help you speak up for the industry.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca/agvocates to join.

“ The natural environment is critical to farmers – we depend on soil and water for the production of food. But we also live on our farms, so it’s essential that we act as responsible stewards.”

- Doug Chorney, Manitoba

“ We take pride in knowing we would feel safe consuming any of the crops we sell. If we would not use it ourselves it does not go to market.”

- Katelyn Duncan, Saskatchewan

“ The welfare of my animals is one of my highest priorities. If I don’t give my cows a high quality of life they won’t grow up to be great cows.”

- Andrew Campbell, Ontario

Safe food; animal welfare; sustainability; people care deeply about these things when they make food choices. And all of us in the agriculture industry care deeply about them too. But sometimes the general public doesn’t see it that way. Why? Because, for the most part, we’re not telling them our story and, too often, someone outside the industry is.

The journey from farm to table is a conversation we need to make sure we’re a part of. So let’s talk about it, together.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca to discover how you can help improve and create realistic perceptions of Canadian ag.