BATTLING BLACKLEG

Developing innovative tactics to battle this chronic disease

Next-gen potato protection is here. Miravis® Duo is a clear level up on foliar fungicides, offering improved early blight control and extended, broad-spectrum disease protection. So now, you can take potato quality from 8-bit pixelated—to crisp, clear HD. No cheat codes required.

To learn more about Miravis® Duo fungicide, speak to your Syngenta Sales Representative, contact the Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or follow @SyngentaCanada on Twitter.

read and

directions. Miravis®, the Alliance Frame, the Purpose Icon and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. © 2021 Syngenta.

6 | Battling blackleg on multiple fronts

Alberta researchers are developing innovative tactics for grappling with this chronic disease.

By Carolyn King

Stefanie Croley

10 | Preparing potatoes for climate change Potato scientists are identifying traits that encourage drought tolerance.

By Rosalie I. Tennison

24 | Understanding in-field variations to boost yields

A new project using soil sensors aims to target fertilization and improve profitability.

By Julienne Isaacs

Bree Rody

By Carolyn King

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

OUR CIRCUS, OUR MONKEYS

Not my circus, not my monkeys. If you’re like me, you’ve probably used that line before to set an imaginary boundary between yourself and a sticky situation. The phrase – a translated version of a Polish proverb – references the idea that a particular problem doesn’t affect you, so you shouldn’t have to worry about it. In fact, it’s probably something you can ignore altogether.

We’ve all thought that way before, though it might not be something we’d like to admit. But the older I get, the more I learn that that even though I might not be the circus ringmaster, I still have a front-row seat to the show. It’s becoming increasingly hard to turn a blind eye to what’s going on around us, and it’s even more important not to ignore it. Just because it’s not happening to me, doesn’t mean it’s not happening.

This was a key message from the panel discussion at the 2022 Canadian Potato Summit, a virtual event organized and hosted by Potatoes in Canada in early February. P.E.I. potato growers have suffered severe stress and loss again this year, after potato wart was confirmed in P.E.I. potato fields in November for the second year in a row, resulting in seed potato shipments to the U.S. being suspended.

No matter your role in the industry, it’s hard to ignore the difficulties growers have faced because of this situation. During the panel at the Summit, Greg Donald, general manager of the P.E.I. Potato Board, shared a bit of the devastation, and we virtually empathized together. But what resonated more for me as I listened to him speak seriously to his fellow panellists and the audience was Donald’s reminder: if it can happen in P.E.I., it can happen to any province, and the implications are felt nationwide. Not just P.E.I.’s circus, not just P.E.I.’s monkeys.

In positive news, just before this issue went to press, the United States had agreed to resume imports of P.E.I. table stock potatoes to Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service is working on their analysis for resuming imports of P.E.I. table stock potatoes to the continental U.S. Progress is good, but the journey isn’t over yet.

As we approach this growing season, it’s more important than ever to keep an eye on what’s happening, both in your fields and beyond. While this setback has been incredibly difficult for growers, it’s not all doom and gloom. Donald and his fellow panellists, Shawn Brenn from the Ontario Potato Board, and Terence Hochstein with the Potato Growers of Alberta, all agreed the Canadian potato industry is an innovative and resilient bunch, producing some of the safest, healthiest and most sought-after crops in Canada. Backed by novel research, both on display at the Canadian Potato Summit, and amongst the pages of this issue, the future is bright for Canadian potatoes.

You can read a more detailed summary of the Canadian Potato Summit on page 20, and watch a recording of all of the sessions for free, online at potatoesincanada.com/summit.

Best of luck as your season begins.

You’re behind Canadian agriculture and we’re behind you

We’re FCC, the only lender 100% invested in Canadian agriculture and food, serving diverse people, projects and passions with financing and knowledge.

Let’s talk about what’s next for your operation.

FCC.CA DREAM. GROW. THRIVE.

PESTS AND DISEASES

BATTLING BLACKLEG ON MULTIPLE FRONTS

Alberta researchers are developing innovative tactics for grappling with this chronic disease.

by Carolyn King

Blackleg is a chronic bacterial disease that is mainly seedborne. Infected tuber tissue turns black and soft. Seed pieces may decay before emergence, resulting in missing spots in the field. If the plants emerge, symptoms include inky black lower stems, wilting, stunting, yellow foliage, and dead plants.

“Our project is using a multipronged approach to blackleg. We are working on better diagnostic tools, we are making sure we understand what is causing the disease these days, we are looking at some novel ways to control the disease, and we’ll be developing a set of best management practices (BMPs) and sharing our research results with growers,” says Dr. Michele Konschuh, a research associate in biological sciences at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta.

In addition to yield losses from the disease, Konschuh notes that a seed potato crop with blackleg levels beyond a certain amount can be downgraded or rejected by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

The three-year project, which started in 2021, is targeting tools, techniques and information that can be transferred to Alberta seed growers. She says, “If we can work with seed growers to address any blackleg concerns at their field level, then by the time the tubers come to the commercial level, they should have less inoculum. And that would mean less risk of blackleg for commercial growers, too.”

Konschuh explains that the updated blackleg pathogen information from the project will help in developing new diagnostic methods and in keeping some really aggressive blackleg species out of Alberta. Development of rapid diagnostic tools will help growers to detect this often-latent disease and to differentiate blackleg from other problems with similar symptoms. And, since there are no commercially available, proven cures for blackleg, new measures for preventing and controlling the disease would be very welcome.

For the project, Konschuh has teamed up with Dr. Larry Kawchuk and Dr. Jonathan Neilson, who are research scientists at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge.

Knowing the enemy

One project objective for Kawchuk is “to get an accurate update on the bacterial species currently causing blackleg in Alberta, and since the disease has been evolving, to characterize it in more detail.”

He and his research group have been working on blackleg on and off for about two decades. “blackleg pathogens are quite universal. If you tried hard enough, you could probably find some in almost all seed. But the disease only rears its head when the environmental conditions are right,” Kawchuk notes.

“Cold, wet conditions during planting really favour the disease by slowing down the emergence of the potato. This gives the pathogen an opportunity to invade the growing tip. Under those conditions, a lot of fields will have up to 70 per cent skips.

“Surprisingly, you also see blackleg in hot, dry summers. In those conditions, it is all about water and transpiration for the plant, and this disease can compromise the plant’s ability to transport water. So, late in the season, you start seeing wilted plants with blackleg on the stem.”

Kawchuk’s group looks at potato diseases in all four western provinces. They typically examine between about 50 and 100 samples of suspected blackleg infections each year, with more people sending in samples in years when the weather favours the disease. In the current

Blackleg symptoms in southern Alberta field in September 2021.

So Much Power. So Little Effort.

Introducing the new highly concentrated formulation of Coragen® MaX insecticide.

Just one 2-litre jug of Coragen MaX insecticide gives you 7 to 21 days of extended control*, excellent tank-mixability and the ability to apply any time, day or night. The smaller jug makes handling, transport, and storage easier than ever. Coragen MaX insecticide lightens the load on bees and many important beneficials** too.

This season, leave the heavy lifting to Coragen MaX insecticide.

project, Konschuh is helping out by recruiting more Alberta growers to send in samples.

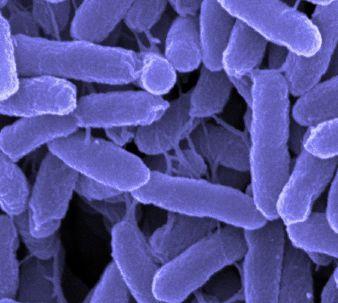

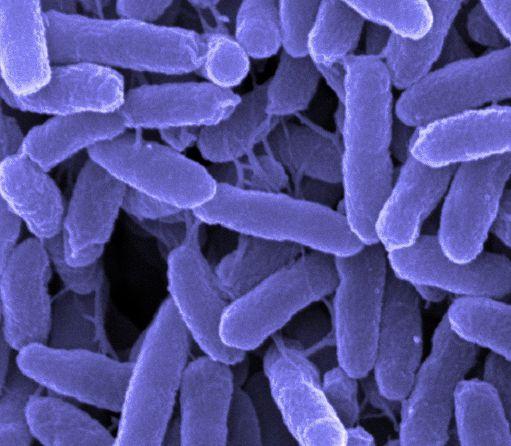

“The main blackleg pathogen we find is Pectobacterium atrosepticum, which makes up at least 80 or 90 per cent of the samples that we examine each year. In the last year or so, we have also picked up a few Pectobacterium carotovorum,” he says.

“Many other Pectobacterium species can cause blackleg, and some can be more severe than the two we deal with. Dickeya dianthicola. . . has caused really big blackleg problems in some [American] states. And Europe has been dealing with an incredibly aggressive Dickeya species that can melt a potato in 24 hours; it would be a huge problem if that got into Alberta.”

The good news is that Kawchuk’s group has not found any Dickeya in Western Canada so far. Interestingly, they have noticed that, in some potato varieties, Pectobacterium carotovorum can produce symptoms that may look somewhat like Dickeya

His group also regularly screens advanced potato lines and new cultivars to determine blackleg susceptibility/resistance and provides that information to the breeder and the industry. Intriguingly, Kawchuk’s group has found that some new lines seem to have slightly unusual blackleg symptoms.

So, in the current project, Kawchuk’s group is testing about 10 new commercial lines and advanced lines to look more closely at these different symptoms and to try to determine whether growing conditions, potato genetics, and/or bacterial strains are influencing the symptoms.

Rapid lab and field tests

Pectobacterium species can be detected using PCR testing, but in this project Kawchuk’s group is developing a faster, easier type of DNA-based lab test called an isothermal assay. “That would allow us within an hour or two to tell the producer what they are dealing with, which Pectobacterium species it is, confirming that it is not a Dickeya,” he explains.

“Then down the road, we might be able to turn that into a lateral flow assay, which is the same type of test as the COVID rapid test that people are now using at home.” Although a lateral flow test would not be as sensitive as a PCR test, a grower could use it for on-the-spot diagnosis.

Harnessing beneficial viruses

Kawchuk’s group will also be doing a study with phages, which are viruses of blackleg bacteria, as a way to treat potato seed to eliminate the bacterium.

He explains, “The virus multiples in the bacterium, makes millions

of copies, explodes the bacterium, and infects all the other bacteria in the vicinity. However, the virus is very specific; it will usually only work on one particular Pectobacterium. So, it may only work for the ones in Alberta, and not for the ones in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.” That specificity also has a positive aspect in that it avoids concerns about the treatment’s impacts on non-target organisms.

Over the years, Kawchuk’s group has been experimenting with using phage for blackleg control. “We’ll take potato samples from a producer who is having a chronic blackleg problem. We’ll isolate the bacterium causing the disease and give the producer all the information related to that. But then we’ll take the bacterium and isolate any phage in the sample. Then we multiply that phage and give it back to the producer so they can add it to a tank mix [to treat seed] or incorporate it in some way.”

According to Kawchuk, once a phage is isolated and characterized, it is fairly easy to multiply in the lab. He adds, “One grower asked me, ‘If it comes off my farm, why isn’t it working there?’ We suspect the phage was just not present in a high enough quantity [to really impact the bacteria’s population].”

The phage treatment effects are very impressive. Kawchuk says, “We have seen yield increases in Saskatchewan of 30 to 40 per cent from the treatment.”

Towards early interventions

The primary goal of Neilson’s research in this project is to answer some key questions: “One question is: can we develop methodologies to distinguish between different blackleg pathogens that cause the same or similar symptoms? And if we can, then what is the earliest time [in the seed certification system] that we can detect the pathogens, is there a remediation that can be applied to prevent or treat the disease, and does that remediation have to be species-specific?”

He adds, “Because blackleg is seed-borne and because of the way Canada manages seed potato certification, blackleg lends itself to an early intervention. So we’re using blackleg as a case study for that. We’re also hoping the technologies and protocols coming out of this research will be applicable to other diseases.”

Based on industry stakeholder input, Neilson and his research group have selected three potato varieties reported to have some tolerance to blackleg and three varieties reported to be extremely susceptible to the disease. The group will be comparing how each variety responds to different blackleg pathogen strains that they recently collected in Alberta, and they will be determining how well some potential detection and treatment methods work with each potato variety and each blackleg strain.

Early detection

Neilson wants to develop some non-destructive methods to detect blackleg early, before the symptoms of tuber rot become obvious.

“Right now, we’re using scientific equipment, not something that a grower would use because it is expensive and requires training,” he notes. “But we’re hoping to figure out what kind of devices or protocols would be needed, and that we can work with industry partners to roll them out.”

Neilson’s group is working on two detection methods at present. One is an electronic nose with sensors that can detect volatile gases in a container holding tubers. The types of volatile compounds released by tubers indicate the state of the tubers, including the development of disease. Neilson says, “Our question is: is there a specific profile of the different types of gases that are indicative of, for instance, a blackleg infection versus soft rot or pink rot or Pythium, and is there a difference

Blackleg symptoms in a southern Alberta field in July 2021.

PHOTO COURTESY OF DR. MICHELE KONSCHUH.

PLOT A AGAINST DISEASE. REVYLUTION

New Veltyma fungicide, with Revysol technology, provides broader, stronger and longer protection.

Potato growers can rise up against disease like never before thanks to Veltyma® fungicide. It combines the enhanced performance of Revysol® and the proven Plant Health Benefits of pyraclostrobin for optimal protection against early blight, black dot and brown spot. Visit agsolutions.ca/veltyma to learn more.

PREPARING POTATOES FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

Potato scientists are identifying traits that encourage drought tolerance.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Potatoes – a sturdy, nutritious crop – can withstand minor dry spells, low numbers of insects, and modest disease pressure. However, when the pressure from any challenge to the crop’s successful growth occurs, growers need to take action. In the case of prolonged dry spells, growers can irrigate the field. But the threat of climate change means there may be less water for irrigation and the crop will not be able to withstand the pressure of months or even weeks of drought. At the Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) Research and Development Centre in Fredericton, researchers are already considering a future with less water resources and how we can continue to grow potatoes under these changed conditions.

Dr. Keshav Dahal and his colleagues have completed preliminary research on potato response to drought stress. He says his research will give breeders information on where to focus their attention as they develop drought tolerant varieties.

Dahal and his team conducted their work in the controlled environment of a greenhouse. They identified drought-tolerant traits, such as water-use efficiency, that breeders could use in future programs. Beginning with 56 cultivars, the field was narrowed to six that had different responses to drought. Each difference was identified.

But the research has only just begun. “This is the beginning of my work,” Dahal says. “We need to do more before we can make recommendations to farmers.”

Findings to date

Dahal says the most notable discovery, so far, is the negative effect drought has on photosynthesis, a process for making carbohydrates that is essential for both biomass and tuber production. He says further examination of this factor would give breeders guidance on how to select for water-use efficiency.

“Drought-tolerant cultivars can survive easier because they are more water efficient,” Dahal explains. “They also have more protein in their leaves. We need to identify the specific proteins in the plant that cause greater tolerance to water stress.” He says, by identifying physiological, biochemical and molecular traits that resist stress, breeders will have information to make breeding for drought tolerance more efficient. When all the genetic drought-tolerance information is linked together, new cultivars with improved adaptability and

ABOVE: In Keshav Dehal’s research, potato plants were tested to determine their drought tolerance for different lengths at different ages.

productivity could withstand the stresses of climate change.

Breeders are currently using potato breeds that are known to be drought tolerant and then using them as parents to give new cultivars the same trait. However, Dahal’s work will identify the exact genetic sequence and strategies that a potato plant needs to be effectively drought tolerant. For example, he notes that drought-stressed plants tend to fold their leaves to minimize transpiration water loss from plants. However, the cost associated with narrower leaves is a reduction in photosynthesis, leading to reduced production. As a result, he questions whether efficient water use within the plant will ensure

photosynthesis is not jeopardized.

Next steps

The research Dahal is doing would be difficult to replicate in a field situation. He is attempting to isolate the exact genetic markers and their sequence to ensure the correct genetic material is identified that could then be used to express the trait in new varieties.

“Some plants may have tolerance at different stages of development,” he explains. “We have identified some markers that can be used in building new cultivars.” But, he adds, it is helpful to understand how each one relates to drought, and what triggers one trait over another. “In the future, we are going to need drought-tolerant cultivars,” Dahal says. “We are already experiencing drought and it will become more serious. From a climate change perspective, we will have more frequent and severe droughts that will increase transpiration, which will cause a moisture deficit in the plant.” The result of the moisture deficit will be yield loss.

But, he believes, his work will give breeders the information they need to develop drought-tolerant potatoes that can maintain photosynthesis and tuber yield under predicted drought scenarios.

It’s possible that breeders will eventually be able to adjust popular varieties, such as Russet Burbank or Shepody, to make them more drought tolerant by incorporating the traits identified in Dahal’s research.

As warnings about climate change face the crop production regions of the world, Dahal is attempting to identify the genes potato breeders will need to ensure this important crop is ready for the stress of a warming planet’s growing seasons.

Forecasting potato diseases has come a long way

New agricultural technology like the Spornado Air Sampler can take you even further.

Don’t let airborne spores sneak up on your potatoes. Late blight and other diseases can now be detected by using the Spornado Sampler. The Spornado is a windpowered air sampler with a filter cassette that samples air in your field 24/7. The cassette is sent to a Spornado Lab for a highly sensitive DNA analysis with results emailed to you within 24 hours. Access to this information can save money and will make fungicide applications more accurate - every potato grower should have this innovative technology in their toolbox.

Well-watered plants were watered every day to field capacity. Six-day plants were withheld water for six consecutive days at five weeks old.

PESTS AND DISEASES

A DOUBLE WHAMMY FOR TUBER MARKETABILITY

Potato mop-top virus and powdery scab can be a tough twosome.

by Carolyn King

Potato mop-top virus (PMTV) is a tough-to-control, soil-borne pathogen. The only known way this virus can infect a potato plant is by being carried into the plant by the tough-to-control, soil-borne pathogen that causes powdery scab.

Xianzhou Nie’s current research includes projects to learn more about PMTV in Canada, to develop a better way to detect both pathogens, and to find options to help manage the two diseases.

“Mop-top disease seems to be an increasing issue in the United States and in certain Canadian provinces. In the States, some people think mop-top could be the next production issue for the future because the disease can really affect tuber quality,” says Nie, a research scientist in molecular virology with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Fredericton.

The virus can cause symptoms in potato tubers and foliage, although sometimes the infection is symptomless. “The foliar symptoms are mainly yellow arcs or V shapes, or a yellowish mosaic pattern. However, in New Brunswick, I hardly ever see these foliar symptoms; most of the time I see tuber symptoms,” he explains.

“When a susceptible potato is infected with the virus, it may develop some necrosis of the tuber tissues.” Necrosis refers to brown, dead tissue. If you cut open a PMTV-infected tuber, you may see a necrotic stripe, or necrotic flecks or arcs; these symptoms are sometimes called spraing disease. The virus may also

cause symptoms on the surface of an infected tuber, such as rings or blotches.

Nie says, “A tuber showing internal necrosis may not cause harm to human health, but it really affects the end-use. For a processor, the necrosis causes quite a bit of loss, and for a consumer who cuts open an affected potato, the necrotic symptoms are an unappetizing surprise.”

The powdery scab pathogen that vectors PMTV is called Spongospora subterranean forma specialis subterranea (Sss). Sss is a fungal-like microbe known as a protist.

“Sss is an obligate parasite. That means it needs a host in order to complete its life cycle. So scientists can’t cultivate the microbe in the lab, which makes studying it much more difficult,” he notes.

“Sss has a complex life cycle with sexual and asexual stages. The pathogen’s resting spores can survive in the soil for many years – 10, 15, 20 years. Then, when conditions become favourable, this resting form germinates, releasing zoospores. These zoospores are able to swim around a little in moist soils. A zoospore can penetrate a potato plant’s underground tissues, such as root or tuber tissues, especially through a wound or other opening. Once inside the plant, the zoospore goes on to develop and release new spores, which cause secondary infections.”

Although powdery scab may reduce potato yields, a more

ABOVE: The potato mop-top virus can cause tuber necrosis symptoms, which are known as spraing disease.

PHOTO COURTESY OF XIANZHOU NIE.

serious problem is that it causes brownish scabs on the tuber’s surface, which reduces the market value significantly for both fresh and processing uses.

And of course, another problem is that Sss transmits PMTV. Nie says, “When an Sss zoospore containing the mop-top virus infects a potato plant, the virus can be released into the plant as well.”

Both Sss and PMTV need cool, moist conditions to infect a host plant. The virus can survive for many years in the soil, protected within the protist’s resting form.

“Interestingly, when you plant a PMTV-infected tuber in the greenhouse, the plants emerging from that tuber are virus-free. This is called self-elimination,” he explains. “So, a PMTV infection in the field is almost always a new infection; it is not from the previous mother tuber. In other words, the infested soil contains the powdery scab pathogen, which contains the virus and that is the major source for the PMTV infection.”

Nie notes that there are no really effective ways to control PMTV and Sss at present. Some practices that may help to manage the two diseases include choosing less susceptible potato varieties, avoiding fields that are known to be infested, avoiding poorly drained fields, and cleaning soil from field equipment before leaving an infested field. Although a longer crop rotation won’t get rid of the two pathogens, it could help to reduce the inoculum levels in the infested soil.

Learning more about PMTV

Nie is leading a five-year project on PMTV and several other tuber necrosisinducing viruses. This project, which started in 2018, is funded through the Canadian Agri-Science Cluster for Horticulture 3, in cooperation with AAFC, the Canadian Horticultural Council, and industry contributors. His collaborators include colleagues from the New Brunswick Department of Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fishery, Agricultural Certification Services, Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, McCain Foods, J.R. Simplot Company, Manitoba Horticulture Productivity Enhancement Centre Inc. (MHPEC) Inc., Potatoes New Brunswick, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

The researchers and the industry want to get a better handle on the issue of tuber necrosis in Canada, so this project is studying all the major tuber-necrotic viruses: PMTV, tobacco rattle virus, potato virus Y strain NTN, and alfalfa mosaic virus.

One of project’s objectives is to determine the occurrence of these four viruses. So far, Manitoba and New Brunswick are providing tuber samples for analysis. In those samples, PMTV is the most commonly detected cause of tuber necrosis.

A faster test for PMTV and Sss

Since PMTV’s symptoms may be confused with symptoms of other potato problems and since PMTV-infected plants sometimes have no symptoms, laboratory tests are needed to confirm the virus’s presence. However, the traditional testing methods are time-consuming.

So, as part of the Horticulture Cluster project, Nie and his project team have developed a faster, more efficient test that detects not only PMTV but also Sss – the first method able to detect both pathogens simultaneously.

According to Nie, it is very difficult to

inoculate potatoes with PMTV, and the pathogen is particularly hard to detect in soil samples. “Until we developed our new method two years ago, the detection of the mop-top virus always used a bait method. With this method, if you suspect that a soil is contaminated with the virus, then you grow a bait plant, like a tomato or tobacco plant, in the soil. If the bait plant becomes infected with the virus, then you can detect the virus from that plant.”

The bait method takes at least a couple of weeks, including time needed for the bait plants to be transplanted into the soil and become infected and time to conduct a lab test to detect the virus extracted from the bait plant tissues.

In contrast, the new method can detect the virus directly from soil samples and can be completed in two to three days.

The new test uses a technique called high-resolution DNA melting (HRM) analysis. Nie explains that HRM is a form of PCR test, but it is simpler and quicker than a regular PCR test. Regular PCR testing involves first ‘amplifying’ the region of interest in the organism’s DNA to cre -

ate millions of copies of that region. This amplified region is known as an amplicon. The amplicon’s DNA is then extracted using a process called gel electrophoresis, and then those results are analyzed.

The HRM method uses the same amplification step as a regular PCR, but then the amplicon is simply heated. The temperature at which the double strands of the amplicon’s DNA come part into two separate strands is its melting temperature. The exact melting temperature differs depending on the DNA; for instance, PMTV has a different melting temperature than Sss.

“Recent-model PCR machines can automatically detect and record these melting temperatures. We just need 5 minutes to do the melting test, so it saves a lot of time and effort,” Nie says.

“[Because the HRM test is much more efficient] we can use it for large-scale surveys of fields to see which fields are infested with PMTV, or Sss, or both PMTV and Sss. Growers could use that information to help in managing these diseases. For instance, if you know a field is infested with PMTV and Sss, then you could take steps to minimize the movement of

PMTV tuber necrosis symptoms.

PHOTO COURTESY OF XIANZHOU NIE.

soil from that field to other fields as a way to limit the spread of the

Potato variety trials

Nie and his team used their new HRM test to identify a highly infested area within a PMTV-infested field in New Brunswick. In the Horticulture Cluster project, they are using that location to conduct their trials to determine the sensitivity of different potato varieties to PMTV-induced tuber necrosis.

Such varietal information could help growers, breeders and the industry to reduce the occurrence of these necrotic symptoms in Canadian potatoes.

The team conducted the field trials in 2019 and 2021, and they will be continuing this work in 2022. (The 2020 trial was cancelled due to COVID restrictions.) Nie says, “In total so far, we have tested 21 potato varieties. All of the varieties are commercially important either to our collaborators or to the industry.”

Their preliminary results indicate that red-skinned varieties are more sensitive to PMTV-induced tuber necrosis than the other types of potatoes. And russet types generally seem to be a little less sensitive than the other types.

Nie emphasizes, “Even the cultivars that seem less sensitive are not resistant to PMTV. They still can be infected by the virus, but they are less prone to having tuber necrosis symptoms.”

Could trap crops help?

Nie and Dahu Chen, a plant pathologist at AAFC-Fredericton,

are collaborating on a project to explore a different idea for suppressing powdery scab and mop-top disease in New Brunswick. This project is funded by Enabling Agricultural Research and Innovation, a program of New Brunswick Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries.

“Dahu came up with the idea that we may be able to use trap crops to manage these diseases. Potential trap crops would be plant species that can be infected by Sss but that do not enable Sss to complete its sexual cycle and form resting spores,” explains Nie. Such trap crops could be included in the crop rotation of an infested field to reduce the field’s inoculum levels of Sss and PMTV.

COVID limitations and restrictions have slowed the project’s progress, but the project team has been able to do some screening in the greenhouse. They have been testing different varieties of several crop species, such as tomato, red clover, alfalfa, canola, rapeseed and radish, to see whether the roots can be infected by Sss. They have identified some that seem to be susceptible to infection by Sss.

The next stage of the project will be to see which Sss-infected plants produce resting spores and which ones do not. If they find some that do not produce resting spores in the greenhouse, then they could consider evaluating those ones as possible trap crops in field trials.

Nie is hopeful that the new information and methods generated by his current PMTV and Sss studies will help provide a foundation for developing improved, best management strategies for controlling mop-top disease and powdery scab.

PLOT A AGAINST DISEASE. REVYLUTION

Potatoes made easy

Tracking your potato data is easier than ever. Enter your information once and stay in sync with your agronomist and processors. Auto-fill and store your food safety program forms. And a lot more.

Use AgExpert Field Premium for your potato production. Just $399 a year.

AgExpert.ca/Field

New Veltyma fungicide, with Revysol technology, provides broader, stronger and longer protection.

Potato growers can rise up against disease like never before thanks to Veltyma® fungicide. It combines the enhanced performance of Revysol® and the proven Plant Health Benefits of pyraclostrobin for optimal protection against early blight, black dot and brown spot. Visit agsolutions.ca/veltyma to learn more.

A LOW-TECH, HIGHLY EFFECTIVE TOOL

Early detection of late blight can potentially

by Rosalie I. Tennison

By the time growers see the effects of late blight in a potato field, enough damage could have occurred to reduce profitability. Some producers take a “just because I can’t see it, doesn’t mean it isn’t there” approach and use a spray mitigation program in anticipation of late blight showing up in a field. But this strategy costs time and money. What if you could predict that late blight will be a problem before it can be seen?

The Ontario Potato Board’s Eugenia Banks uses spore traps as a predictor of late blight pressure. She considered, if late blight spores could be captured and identified and the number recorded, the severity of late blight could be predicted. Using what she calls “passive” spore traps – a gizmo driven by wind like a weather vane with a cone shaped front to direct the spores onto a filter at the back – she has been alerting growers in the Alliston/Shelburne potato belt in Ontario to potential late blight pressure.

Banks collects the filters from her traps twice a week and sends them for a PCR test. As soon as the results are returned to her, she emails a report to growers. “I tell them the location of the traps and which ones had spores and where late blight might develop,” Banks explains. “I send the results regularly and some growers say they wouldn’t farm without the information they can get from the spore traps. Fungicides are expensive, so it makes sense to use spore traps to prevent spraying indiscriminately for late blight.”

Banks has been monitoring late blight occurrence with spore traps

for six years and she says the low-tech monitoring system is cost effective. She estimates $2,000 pays for 12 weeks of monitoring. Besides purchasing the traps, the price includes filters and the PCR tests. The next cost is the time it takes to remove and replace the filters and immediately send the exposed filter for testing.

Banks believes the cost is easily recouped when the traps indicate there is no threat and spraying isn’t required. Potatoes are also saved when a prediction of late blight pressure guides growers to timely applications of fungicide before late blight can adversely affect the crop.

Results from P.E.I.

The Prince Edward Island Potato Board began using spore traps a few years ago with similar good results. In 2021, the third year of the program, the Board organized a province-wide sport trap reporting program, including using the same sport traps and PCR testing as Ontario. According to Ryan Barrett, the Board’s research and agronomy specialist, the system helps growers make timely decisions.

“If blight is detected in a certain area, it provides growers with that information, in order to inform whether they need to tighten spray intervals or change their fungicide choices,” Barrett explains. “If no late blight is detected and conditions are not favourable to blight infection,

ABOVE: Spore traps, shown here in Shelburne, Ont., have become a way for the Ontario Potato Board to predict late blight pressure.

Your crop is your masterpiece.

We just bring the tools. The unmistakable red formula of Emesto® Silver fungicide seed treatment protects your potato seed-pieces from seed and soil-borne diseases. With two modes of action against fusarium, it even safeguards against current resistant strains. But what insecticide you choose to combine it with is completely up to you – because when it comes to art, the artist always knows best.

&

SAVE $8/ACRE when you purchase matching acres of Emesto Silver and Velum® Prime nematicide/fungicide. GrowerPrograms.ca

[the tool] provides growers with information to look at lengthening spray schedules or skipping a spray. This reduces the amount of pesticides used, and saves the farm considerable amounts of money.”

Late blight has not been detected in P.E.I. for a number of years, according to Barrett. However, if late blight is found, it could severely impact the crop. “By using the results of spore trapping services as well as weather-based decision tools, a number of PEI producers have been able to reduce the number of fungicide applications per season without increasing the risk of late blight infection,” he says. “This is both great for the environment, [and] great for the producer.”

Growers with multiple fields of potatoes, or who are not in proximity to potato board-sponsored spore trap technology can manage the

DIY SPORE TRAP MONITORING

For growers who want to manage their own system of spore trap monitoring, Eugenia Banks, Ontario Potato Specialist, has some helpful hints:

1. Install traps before crop emergence.

2. Place traps as close to the crop as possible.

3. Ensure traps are at least 90 centimetres above the ground.

4. Place in the areas of the field where wind is prevalent.

5. Use at least two traps in areas where late blight was first detected in previous years.

6. Ensure traps will not interfere with farm equipment.

low-tech system themselves. Or, they can engage companies, such as Spornado and AIR Program, which offer the service on contract and will send regular updates to the grower. Some offer more than just late blight monitoring and include information on weather and other pathogens.

“Spore traps are another tool to combat late blight,” Banks explains. The fact that the tool is inexpensive and uses only wind energy to operate non-stop throughout the growing season, also benefits the environment, she adds.

Work done by provincial potato boards in Ontario and P.E.I. prove this low-tech technology is worth its hundredweight in giving growers information on whether to ramp up late blight control or to save money by reducing fungicide when late blight is not present in the field.

7. Monitor traps at least twice a week replacing filters each time.

8. Send filters to lab immediately by courier.

9. Expect PCR test results the same day lab receives the filters.

The laboratory results will give growers the information to determine if control is needed and how soon to start. Banks suggests tank-mixing a late blight-specific fungicide with a broad-spectrum fungicide, which will minimize late blight pressure and control other pathogens in the field.

KEEPING AN EYE ON THE FUTURE

The 2022 Canadian Potato Summit highlighted breeding, pests, business and more.

by Bree Rody

The 2022 Canadian Potato Summit was broadcast virtually on Feb. 2 and featured guests from Alberta to P.E.I. Throughout the day, more than 300 viewers tuned in to gain potato insights from the space where science meets business, and where the present meets the future. UPL OpenAg served as the 2022 presenting sponsor; FCC, Gorman Controls and Syngenta were gold sponsors; BASF, Bayer Crop Science and Eco+ were silver sponsors; and Tolsma USA was a bronze sponsor.

Breeding for the future

The day opened with a keynote from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher Helen Tai, who had her eye set on the future – and dove deep into how breeding and improving tuber quality can help create potatoes that mitigate the effects of climate change, such as sensitivity to heat and drought.

The solution, Tai said, is new varieties that balance feasibility and desirability – which takes vast amounts of time and effort. In the AAFC’s breeding system, there are 400 parent plants that are cross-fertilized, resulting in roughly 60,000 genetically unique seeds. Those seeds are grown to form mini-tubers, which are then planted in the field. Of those 60,000, Tai explained, only 0.02 per cent makes it to evaluation, and only 0.002 per cent of the original 60,000 make it to commercial release. To put it bluntly, said Tai, “We need better variety, faster.”

DNA sequencing is necessary, because potatoes are far more genetically complicated than other crops like corn or rice. “Bad genes can get hidden, [while] good genes have a hard time getting expressed.” The good news for breeders is that DNA sequence costs have gone down significantly.”

An ideal solution would be to use marker assisted selection (MAS), which would create a map of the potato’s genetic markers, associate the potato’s traits with the markers and then use those for genetics and breeding. Tai currently leads a project on this type of genomic selection for potato breeding.

There’s also genetic transformation, although Tai noted that AAFC does not use this method. Genetic transformation involves genetic engineering of a vector in a lab to carry a new gene into the plant, which results in products commonly known to consumers as genetically modified (GM). Tai noted that there is “a lot of regulation” around genetic transformation, and that consumer acceptance is required for the commercialization of varieties using gene transformation. Changing this mindset involves emphasizing variety, Tai notes. “Some people say ‘I don’t like genetically modified foods.’ But it depends on what it’s being used for. You have to look at each one case-by-case.”

The conversation on potato breeding continued with a presentation by Erica Fava, a research assistant with AAFC’s potato breeding

program in Fredericton, who provided an overview of current breeding activities across Canada. Fava explained strategies for developing new cultivars, as well as which gene expressions and traits the breeding team looks for. Since 2017, when the agency “overhauled” its breeding program, it’s used new innovations such as judging potato colours more objectively by colorimeter, versus a more subjective “eye test.”

Currently, AAFC is applying a number of new sciences in the breeding pipeline, including Tai’s genomic prediction models as well as development of imaging analysis and vigorous methods for disease screening. Current goals are to increase disease resistance, increase genetic gain, find selections that are well adapted to Canada’s climate and find traits that are desirable in the industry. But by far the most important factor in advancing potato breeds is feedback, Fava emphasized, encouraging viewers and other growers to reach out to breeders and researchers and let them know what is working.

Problematic pests

Vikram Bisht, plant pathologist with Manitoba Agriculture, offered a summary of the pests that are of the biggest concern for Canadian growers, noting Colorado potato beetle, European corn borer and aphids among the most pressing challenges.

The biggest issue when it comes to Colorado potato beetle is insecticide resistance, which is developed as a result of both repeat exposure to insecticides and the insect’s inherent genetics. This trait is being monitored across Canada. Bisht noted that European corn borer (ECB) is an “up and down” concern, and not considered a major threat in most areas, save for certain parts of Manitoba. The species spiked in numbers

ABOVE: A screenshot from the virtual Canadian Potato Summit, featuring a presentation from Dr. Helen Tai, researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Fredericton.

We’re looking for six women making a difference in Canadian agriculture. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving Canada’s agriculture industry.

in 2016, and researchers have found that at low levels, it is not necessarily the tunnelling of the ECB that causes yield loss but rather injuries. When boring holes, the ECB can see parts of its limbs break off in those holes, which causes stem rot. Fortunately, Bisht said, most insecticides that work on beetles work on ECB.

Business matters

Disruption played a major part in the state of the industry panel discussion featuring Greg Donald, general manager of the P.E.I. Potato Board, Terence Hochstein, executive director of the Potato Growers of Alberta, and Shawn Brenn, chair of the Ontario Potato Board. With major concerns such as potato wart and its effects on export markets, higher input prices and continued uncertainty regarding the availability of trucks and freight, it’s proof there’s never a dull moment for potato growers.

After what Brenn called “one of the most comfortable growing seasons” in recent memory for summer 2021 (including yields 15 to 20 per cent higher than 2020), both he and Donald say growers are bracing for the most expensive crop they’ll ever plant this coming season.

“The word ‘uncertainty’ pretty much covers it,” said Donald, who estimates that the cost

per acre will be $900 to $1,000.

Hochstein echoed the concerns, sharing that Alberta’s expected input costs will rise by 20 per cent. But it’s more than just the upfront costs, he cautioned. COVID outbreaks, which come in waves, affect the processing and packaging sector. Luckily, Hochstein noted, Alberta growers are able to pivot, because in his region there are about a half-dozen other crops to bring in the rotation.

“There have been some pivots [to] alternative crops,” he said. “We have growers saying, ‘why would I spend 20 per cent more on this particular crop?”

Brenn and Donald noted growers in their regions – particularly P.E.I. – are slightly more limited when it comes to alternate options. “There are still certain people [who] have contracts, [who] don’t have the flexibility to just say, ‘I’m gonna grow corn or soybean,’” Brenn said.

For Donald and other P.E.I. growers, the second year in a row of potato wart being detected in the province caused extreme strain. In November 2021, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s confirmation of potato wart in the province resulted in a temporary suspension of potato shipments to the U.S. When the

same such incident occurred in December 2020, the U.S. embargo lasted for approximately three months. Donald issued a sober warning to his cross-country colleagues: “If the U.S. is permitted to close their market to a Canadian competitor, this can happen to any province in Canada… I just can’t describe or put into words the devastation this has caused.”

But the panel agreed, like many others over the last two years, potato growers have found many silver linings. Hochstein said demand continues to grow for frozen products, as does the chipping industry, with another potato chip plant opening in Alberta. Brenn and Donald also bored the innovation and high standards of safety that are common across the industry. “We have innovative, forward-thinking growers,” Brenn said.

Donald added that the various initiatives taken by the industry to ensure that foods are safe and traceable deserve to be celebrated and marketed even more. “That’s something we don’t capitalize [on] enough when we market our products. Some of the [safest] food in the world is produced in our country.”

Visit potatoesincanada.com/summit to access recordings and bonus video interviews from the event.

Syngenta_Potato_Portfolio_2022_Partners_PotatoesinCanada.pdf

2022 Ontario Potato Conference

Wednesday, March 2ND

SCHEDULE:

10:00 a.m. ET

Battling the Blackleg complex successfully

Ian Toth, James Hutton Institute, Scotland, UK

10:30 a.m. ET

Black dot - the silent, early yield robber: Epidemiology and management

Julie Pasche, North Dakota State University

11:00 a.m. ET

Experiences with minimum tillage on potatoes

Homer Vander Zaag, H.J. VanderDer Zaag Farms Ltd.

BREAK

1:00 p.m. ET

Climate change: How heat impacts potatoes at different growth stages

Mike Thornton, University of Idaho

1:30 p.m. ET

Dealing with Linuron shortage in 2022

Darin Gibson, Gaia Consulting

SOIL UNDERSTANDING IN-FIELD VARIATION TO BOOST YIELDS

A new project using soil sensors aims to target fertilization and improve profitability.

by Julienne Isaacs

Every farmer knows that every field is different – and that there can be a great deal of difference within fields as well. Until recently, the tools to analyze these differences have been out of reach for many farmers.

Despite a growing body of research demonstrating in-field variation, typically, fields are still managed on a field-by-field basis, which can mean both profit losses and negative impacts on the environment. But intensive soil sampling is expensive and time-consuming. Another approach is needed.

Athyna Cambouris is a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Quebec City. She’s been studying applications of precision agriculture since 1996, when she implemented her first experiment on variable application of phosphorous and potassium in potatoes.

Precision agriculture technology has come a long way since the 1990s. These days, Cambouris is working on projects in Quebec, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island focused on delineating in-field management zones based on soil properties using ground-penetrating radar and soil electrical conductivity sensors, among other soil sensors.

It’s a suite of tests called proximal soil sensing (PSS), and they are both commercially available and affordable.

The goal of her research, Cambouris says, is to target fertilization in potatoes to improve productivity and profitability. “Potato is a good crop [to study] because nitrogen doesn’t only influence yield but also quality. If you put on too much or not

enough N, you’ll have impacts,” she explains. “This is one of the reasons I want to work with nitrogen. It’s a great challenge because N presents so much spatial and temporal variability, and part of that can be controlled using management zones in the soil.”

Soil properties that particularly influence N’s effectiveness include various parameters including soil texture, humidity and organic matter, she says. If farmers can delineate management zones (MZs) based on factors like these, they can better target their inputs, especially N.

Living Labs projects

Cambouris is the lead on one study under the AAFC Living Laboratory projects with two growers in the Maritimes that look at using a precision N management approach using MZs. The project began in 2019, and Cambouris and her collaborators delineated MZs using soil electrical conductivity, topography and yield data from yield. Then they characterized the MZs in terms of soil properties. During the growing seasons of 2020 and 2021, they evaluated the plant N status of the crop using vegetation indices extracted from drone imaging.

“We’re doing variable rate of N preplant with one grower. We applied varied rates at preplanting based on MZs we’ve

ABOVE: One of the four experimental fields used in the area of Kensington in PEI Living Laboratory initiatives program of AAFC.

delineated, based on yield, topography, and electrical conductivity,” Cambouris explains. The other producer in the Living Labs project, says Cambouris, wanted to study VR applications in-season; data from that site is currently being analyzed.

Cambouris says looking at soil sensor data is complex, and doesn’t always suggest the same management approaches. But that’s partly the point. “Using soil sensors will help you to capture the spatial variability of the field, but then you have to relate [that data] to what it exactly means. It doesn’t mean the same thing from field to field across the country,” she says.

High soil electrical conductivity, for example, can be linked to clay soils with

higher organic matter and higher water holding capacity, and thus higher yields, in PEI and Quebec. But when Cambouris ran the same experiments on fields in New Brunswick, higher soil electrical conductivity was linked to lower yields. “We were able to relate [this finding] to soil texture,” she says. “In New Brunswick, the soil texture is more loamy than sandy, and they were having drainage problems. That decreased yield.

Management approaches

Cambouris says it can be tough to directly link yield boosts to a MZ-based precision agriculture approach. “Normally, to see if you have a good field showing yield variation, you need to have at least three years of potato yield data, then you can analyze that and see if there is a difference, and you have to look to the climate data,” she cautions.

But in one study, Cambouris was able to demonstrate that a MZ-based approach showed a difference of six tonnes per hectare per year in a specific field.

ai16437279085_CFARMS_21-282_eastern-ad_E_PotatoesinCanada_di.pdf 1 2022-02-01 10:05 AM

“We know that precision agriculture is a science linked to different parameters that could be site-specific. When you identify the soil properties linked to sensor data, you can extract that information and go into another field that presents the same type of soil with similar approaches.”

Once soil properties are better understood in discrete zones, producers can take steps to correct problems in those zones. In a study directed by Cambouris

LET’S MAKE IT TO

In 2022, recycle every jug

Cleanfarms’ recycling helps Canadian farmers take care of their land for present and future generations. By taking empty containers (jugs, drums and totes) to nearby collection sites, farmers proudly contribute to a sustainable community and environment. When recycling jugs, every one counts.

Ask your ag retailer for an ag collection bag, fill it with rinsed, empty jugs and return to a collection site.

info@cleanfarms.ca @cleanfarms

in New Brunswick, for example, a field in the study with high electrical conductivity was characterized by the “wettest soil, the finest soil texture and the lowest tuber yield.” Drainage or land leveling in that portion of the field could correct the problem.

Cambouris says the technology is available in many Canadian provinces. But paying for PSS tests is just the beginning. Producers have to put in the work to understand the management zones and steer away from uniform applications.

“They have to be engaged, and say

Battling blackleg on multiple fronts – continued from page 8

between one species causing blackleg versus another?”

Their initial tests have confirmed that the gas sensors can detect the difference between rotting and non-rotting tubers. Now they are building a prototype electronic nose with several different sensors that each detects a different type of gas.

“The electronic nose is nice because it is scalable,” he says. For instance, if growers just want to know whether they’ve got tuber rot, they could buy a simpler, lower cost unit, and if they want to know which rot pathogen is present, they could buy a unit with extra sensors.

The other method involves measuring different wavelengths of light to try to detect the early development of blackleg within tubers. They have done some preliminary tests, but Neilson hasn’t analyzed the data yet. He notes, “Part of the reason why we wanted to try a few methods is because they could potentially work together in an integrated way. For instance, the nose could identify which bin might have a problem and then the imaging system could identify which specific tubers to get rid of.”

Resisting stress and blackleg

Neilson and his group are also examining how each of the six potato varieties responds to various biological and chemical treatments. All the treatments are reported to increase a plant’s resistance to drought or other environmental stresses. So Neilson is hoping to identify treatments that suppress blackleg while also making the crop more productive.

They will evaluate how each treatment affects things like the variety’s growth and tuber characteristics, and how effectively each treatment controls blackleg. So far, they have experimented with some commercially available products, but they are also planning to collect some native beneficial bacteria and fungi that live inside potato plants.

for example, ‘I can vary my potassium based on management zone, same thing for phosphorous, and the pH map can be very interesting to help limit disease, or I don’t want to put on too much calcium,’ etcetera,” she says. “You can save money by saving inputs.”

“A plant’s microbial community is a combination of what it inherited from its mother plant and what it is experiencing during the current growing period,” he notes. “An ideal situation for controlling blackleg would be a beneficial microbe that we could inoculate as early as possible and that travels with the seed.”

Sharing blackleg BMPs

“One of the challenges for us is to figure out what growers already know now about blackleg, what they need to know based on the results from previous studies, and what we are finding in this project. My role is partly to gather that information,” Konschuh says.

She will be working with the Potato Growers of Alberta to find out things like what practices growers have tried for managing blackleg, and what has worked for them, and she will put together a summary of what the research literature says about blackleg management.

Konschuh might also work with growers on some on-farm agronomic studies. “For example, some of the literature suggests that applying gypsum [calcium sulphate] or calcium nitrate could reduce blackleg. So, if growers are fertilizing anyway, then perhaps we can help them select a fertilizer that would also reduce the incidence of blackleg. We also might do a study to confirm the effectiveness of some measures to reduce the incidence of blackleg, like roguing.”

“We’ll be putting out best management recommendations each year, and then improving on those recommendations and adding more tools, to help growers minimize the occurrence of this chronic disease whenever there’s a wet, cool spring or a hot, dry summer,” Kawchuk says.

This project has funding from Alberta’s Results Driven Agriculture Research and in-kind support from stakeholders in Alberta’s potato industry.

The instrument (VERIS 3100, VERIS Technologies inc.) Cambouris’ team used to measure the apparent electrical conductivity in the PEI field in 2019.

Make more art.

Apply Velum® Prime nematicide/fungicide in-furrow at planting to increase your yield potential. With a unique mode of action and Group for nematode control, it also has secondary fungicidal properties offering early blight and black dot suppression. Get the most out of your masterpiece, with Velum Prime.

SAVE $8/ACRE when you purchase matching acres of Velum Prime and Emesto® Silver fungicide seed-piece treatment. GrowerPrograms.ca