A HELPING HAND

Research shows nurse crops can help potatoes get off to a good start

Your crop is your masterpiece.

We just bring the tools. The unmistakable red formula of Emesto® Silver fungicide seed treatment protects your potato seed-pieces from seed and soil-borne diseases. With two modes of action against fusarium, it even safeguards against current resistant strains. But what insecticide you choose to combine it with is completely up to you – because when it comes to art, the artist always knows best.

6 | Improve the system, improve yield

Following a five-year study, an AAFC researcher believes he can reduce yield decline.

By Rosalie Tennison

12 | Hot potatoes

The heat is on to identify potato varieties that can thrive through climate change.

By Rosalie Tennison

20 | A helping hand

Research shows nurse crops can help potatoes get off to a good start.

By Mark Halsall

Julienne Isaacs

ON THE WEB

STEPHANIE GORDON | EDITOR

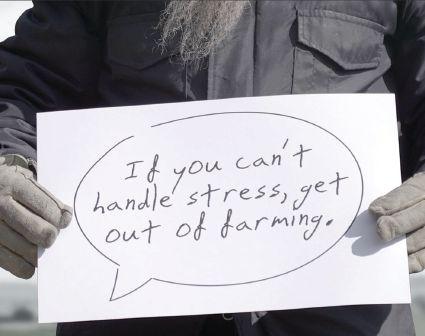

BUSINESS AS USUAL

As we come into the 2020 growing season, faint memories of the 2019 season still linger in some growers’ minds. Especially if you were one of the unlucky ones. One of my favourite questions to ask when I travel to farm shows or potato conferences is, “how was your season this year?” For some this year, it was an easy “good, business as usual” response. For others, it was a polite nod and a “fine.”

In 2019, Manitoba saw an estimated 13,000 acres of potatoes left in the ground, more than double the 5,300 acres left in 2018. Despite this hit, potato production in Canada was up overall, because more potatoes were planted and average yields were up. Our neighbours to the south were not as fortunate. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. spud farmers produced 2.2 per cent less potatoes in 2019 compared to 2018. In states with potato processing capacity, production was down 3.6 per cent.

Do these numbers matter now? Maybe not as much. It depends on how much of the 2019 season we bring into 2020 – hopefully none. There’s a saying that goes “never farm on last year’s weather.” It’s a poignant reminder during outlier years to come into every growing season as you normally would.

When I attended the Manitoba Potato Production Days in Brandon, Man., I felt that’s exactly how growers were entering 2020: with a cautious optimism for the year ahead. This entire spring issue does the same and focuses on what’s to come. On page 14, we share an update on the status of the re-evaluation of several Group M fungicides, some of which will have an impact on your 2020 growing season in various ways. On page 12, we share what’s on the radar of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researchers and their work identifying potato varieties that can thrive through climate change. Finally, we look at what growers can anticipate from up-and-coming trends. Are you thinking of adding micronutrients to your crop management program? Are you thinking of planting a nurse crop to help with weed management prior to emergence? Look into those fresh ideas on page 18 and 20 respectively.

One thing Potatoes in Canada is particularly excited for is our podcast. By the time you’re reading this, Tuber Talk: Canada’s Potato Podcast, will be available wherever you listen to podcasts. We hope to capture some of the discussions our industry is having when it comes to the best production practices and trends. You’ll hear me ask everything from “how was your season this year” to some tougher questions about diseasesuppressive crops and industry challenges. If you haven’t already, check out Tuber Talk: Canada’s Potato Podcast. We hope it will give you a sense of the bigger picture when the growing season rollercoaster takes you through its highs and lows. After all, in the potato industry, these highs and lows just represent business as usual.

FEEDING TIME’S OVER. AND YOU KNOW WHAT THAT MEANS.

Sefina halts feeding and creates a lasting barrier against aphids.

Aphids looking for a quick meal will come up empty thanks to new Sefina® insecticide. In addition to fighting resistance with a new mode of action, it quickly stops aphids from feeding and creates a long-lasting barrier against them. And Sefina is safe for beneficial insects like lady bugs, so you can feel good about turning an aphid’s feeding time into quitting time. Visit agsolutions.ca/sefina to learn more.

Always read and follow label directions.

IMPROVE THE SYSTEM, IMPROVE YIELD

Following a five-year study, an AAFC researcher believes he can reduce yield decline.

by Rosalie Tennison

In many parts of Canada, potato crops are big money earners. For some growers, rotation crops are grown to manage disease, minimize resistance to products, eliminate the tolerance diseases and pests develop to controls and to keep the soil healthy for potatoes. Often rotation crops don’t offer the same rate of return as a high yielding potato crop, but growers believe they are necessary to ensure the health and productivity of the potato crop. However, in Eastern Canada, yields began to decline despite all the management adjustments growers undertook.

In 2013, growers approached Bernie Zebarth, a soil scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Fredericton to see if he could identify the problem. Over the ensuing five years, he has reached some surprising conclusions.

“We looked at a series of options,” Zebarth says. “We wanted to determine what is limiting yields in the first place and then decide what would be the best solution.”

What the examination showed was that soil quality was a big factor in the ability of a potato crop to thrive and produce quality tubers. In particular, the intensive system used to grow potatoes results in declining soil organic matter.

“Soil organic matter is like a bank account,” Zebarth says. “You have to keep a positive balance to have healthy soil.”

The intensive tillage practices used in potato production, short potato rotations, and increased risk of soil erosion, coupled with the low organic matter inputs from the potato crop, all deplete the soil organic matter bank account. Knowing the methods by which potatoes are produced, Zebarth began looking for ways to manage the crop differently.

Of course, increasing rotation is an excellent first step, he says. Adding more crops into a rotation and lengthening the rotation cycle increases the soil organic matter that is so important to potato production. But Zebarth has some fine-tuning for growers to consider when planning a rotation.

“Consider a nurse crop in the spring that is planted at the same time as the potatoes,” Zebarth recommends. “This crop protects the soil until the potatoes get established. Most choices for a nurse crop will provide cover within a week or so. Consider spring barley, oats, or perhaps fall rye.” The plan, he adds, is to reduce erosion, but a nurse crop will also add organic matter.

“Also, consider a fall-seeded cover crop to protect the soil over the winter period. The goal is to keep living roots growing in the soil as much as possible to keep the soil biologically active,” Zebarth adds.

“The big surprise was how prevalent the soil-borne diseases were,” Zebarth says. “In particular, the potato early dying complex. This complex is caused by the fungal disease Verticillium wilt and, in Eastern Canada, is made more severe by the presence of root lesion nematodes.”

The first step is to know your enemy, according to Zebarth. He points out that new research is underway to identify the specific strains of Verticillium wilt present in the different potato production regions of Canada, and also to identify the specific species of root lesion nematodes present in the soil.

A difficulty facing the potato industry is the lack of an accurate diagnostic tool to test for potato early dying complex. Zebarth says work is being done in this area to develop a more effective soil test that will help growers to manage the disease.

Other methods for disease control are being considered, including bio-fumigation using mustard. The mustard produces a chemical compound called isothiocyanate, which produces the bio-fumigation effect; in field-scale trials, there was a noticeable reduction in pathogens and yields increased.

“Economically, using mustard bio-fumigation takes a field out of production for a season,” Zebarth admits. “But it could improve potato yields.” He suggests using this method on a field that is in distress and in need of help getting back to a healthy state.

“There is no silver bullet for controlling potato early dying,” he

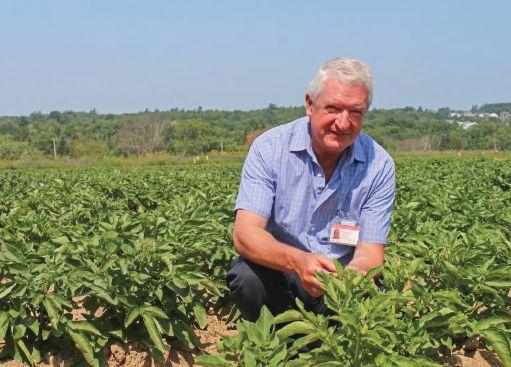

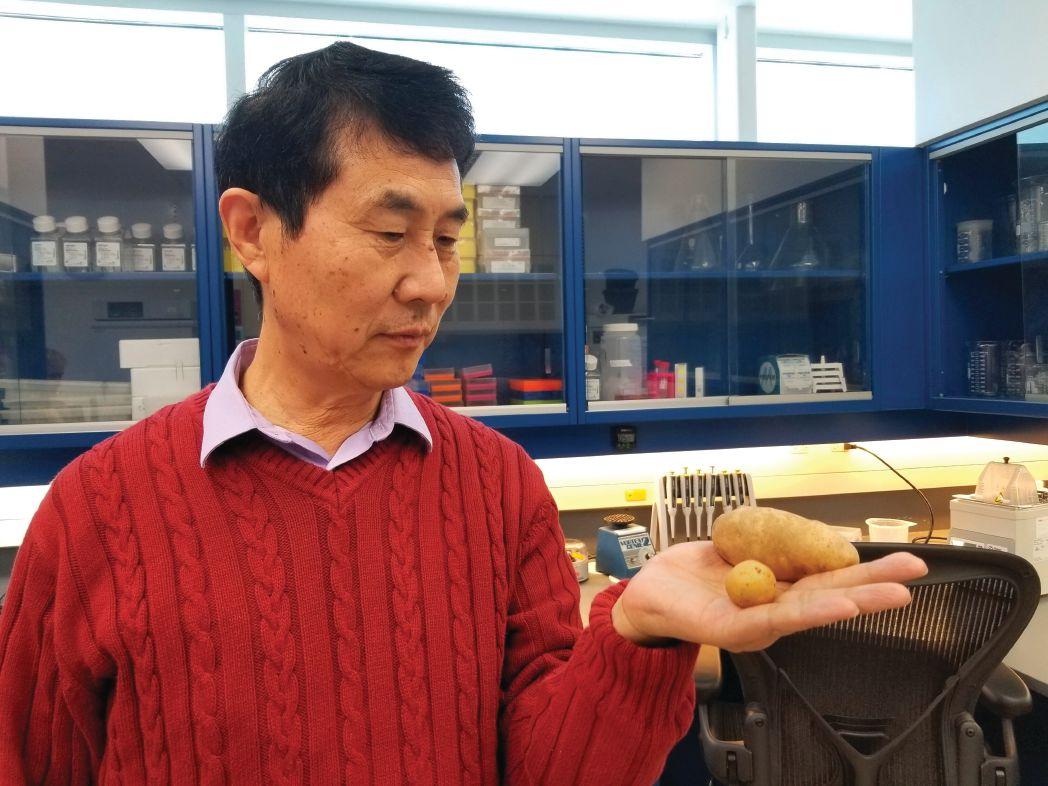

PHOTO COURTESY OF AAFC.

Bernie Zebarth, a soil scientist with AAFC in Fredericton, was approached by growers wondering why yield was declining despite all the management adjustments growers were making.

continues. “We need to make progress on an integrated system.”

He says growers changing their attitudes towards best practices in every part of the operation could be key. Consider upgrading aging equipment to something more efficient and accurate, with the latest technology. If possible, choose equipment that is gentler and causes less disturbance to the soil. Also, trying the newest diagnostic tools and adopting new ways to control disease, such as bio-fumigation, will make a difference.

“We need to start thinking about soil as part of the farm infrastructure,” Zebarth advises. “If you use a simple return on investment approach for soil conservation practices, it’s hard to justify. But taking the whole process all together can lead to cumulative improvements that can be credited to all crops over time. If half the value of your operation is your land, you should do what you can to protect it.”

An analogy for what Zebarth is suggesting is the purchase of a house. It’s one of the largest purchases made in a lifetime and

no one would ignore repairing the roof when it starts to leak. With land being a grower’s largest purchase, the researcher believes it should receive the greatest care to ensure long-term success of the entire operation. The big difference, of course, is that while you can fix your roof quickly, it is not the same for your soil which, once depleted, may require several seasons to replenish it.

Zebarth suggests the industry may need to change its way of gauging success and move from an economics-only model to one that considers the long-term value of soil management. He believes that five years of study and the consideration of many ways to improve soil to ensure yield maintenance or improvement has identified some effective ways to protect the soil. While we still do not have all the answers, he admits, some management options, such as nurse crops, longer rotations, bio-fumigation, and adopting the latest technological advancements in equipment could stop the negative trend in potato yields.

PESTS AND DISEASES

TACKLING A “PROBLEM WITH NO SOLUTIONS”

Research towards common scab management that is targeted to field-specific conditions.

by Carolyn King

The biggest challenge in managing common scab is that all the control measures produce inconsistent results: they work in some fields but not in others. So Eugenia Banks, potato consultant for the Ontario Potato Board, has conducted a two-year project that makes progress on a fieldspecific approach to scab management for Ontario conditions.

“Common scab is the most important soil-borne disease of potatoes in Ontario and across Canada,” Banks says. “Scab does not reduce yield, but the corky, superficial or pitted lesions that develop on infected tubers render the potatoes unmarketable.”

Banks is very aware that developing more consistent scab control methods is an uphill battle for researchers. “Back in 2007, I organized the first International Common Scab Conference in North America. Speakers from all over the world provided information on their ongoing research projects to control common scab. But 12 years after the conference, we have not made much progress. Common scab remains a problem with no solutions.”

One key advantage these days is that advances in molecular technologies are making identification of the different species of scab-causing bacteria much easier and faster. Streptomyces scabies is considered to be the main species causing scab worldwide, but it is not the only Streptomyces species that can cause the disease.

“Recent research has suggested that different species of pathogenic Streptomyces respond differently to recommended management practices,” Banks explains.

One of the objectives of her project was to identify which Streptomyces species is causing common scab in Ontario potato fields. The project also examined whether the scab species in a field is correlated with the field’s soil properties and evaluated the performance of a biocontrol agent for managing scab.

This Ontario Potato Board project ran from 2018 to 2019.

Surprising species results

In the project’s first year, Banks collected soil samples from 50 potato fields in different parts of Ontario, to survey the Streptomyces species and assess soil fertility.

“For many years, Streptomyces scabies was assumed to be the prevalent common scab species in Ontario. We suspected that other species were also present, but which ones? When fighting common scab, you need to know the enemy to try to win the battle.”

As part of the project, A&L Canada Laboratories used molecular technology, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods, for rapid, accurate fingerprinting of the Streptomyces species causing common scab.

Their tests found that 48 of the 50 Ontario fields were infested with common scab. Of the two non-infested fields, one was located near Alliston and the other near Sudbury.

The PCR tests identified four Streptomyces species in the surveyed fields. Streptomyces stelliscabiei was the most widespread, followed by Streptomyces scabies, Streptomyces acidiscabiei and Streptomyces turgidiscabiei

Most of the infested fields had more than one of these four species.

Banks emphasizes, “The fact that Streptomyces stelliscabiei is the predominant species in Ontario – and not Streptomyces scabies as expected – is a major breakthrough result. It could lead to development of practices that specifically target this species. Two fields with high levels of Streptomyces stelliscabiei and no other scab species had about 100 per cent scab incidence in 2018.”

The molecular testing also detected the presence of a toxin called thaxtomin in nearly all of the soil samples. This plant toxin is produced only by pathogenic species of Streptomyces and causes the development of common scab lesions.

ABOVE: Common scab is the most important soil-borne disease of potatoes in Ontario and across Canada.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF EUGENIA BANKS.

The results of the soil nutrient analyses were also very interesting. “The levels of micro- and macro-nutrients varied enormously. Soil pH, per cent base saturation of hydrogen, and the potassium-to-magnesium ratio were found to be the most important factors correlating to levels of common scab in Ontario potato fields,” she says.

“These findings will help to develop a strategy to reduce the incidence of common scab in Ontario.”

She also notes, “Streptomyces stelliscabiei appeared to be suppressed by [higher levels of] organic matter in the soil, but this effect was not noticed with Streptomyces scabies.”

Promising biocontrol results

In the project’s second year, Banks assessed the effectiveness of a strain of the bacterium Pseudomonas synxantha as a biocontrol agent for managing common scab.

This strain, called LBUM223, was found in a New Brunswick field by research scientist Martin Filion. In his research at the Université de Moncton and now at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Filion has been investigating various microbial strains as control measures for common scab. LBUM223 is one of the most promising candidates he has found so far.

“LBUM223 has reduced common scab symptoms in research trials in Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick,” Banks says. Her 2019 study was the first evaluation of LBUM223 under Ontario conditions. She assessed LBUM223 in a research plot embedded in a commercial potato field with sandy soil near Alliston. The predominant common scab species in the plot was identified as Streptomyces stelliscabiei. The trial involved Yukon Gold, a potato variety that is highly susceptible to the disease.

For this trial, Filion provided a pure culture of LBUM223. The inoculum was prepared by Afsaneh Sedaghatkish, a PhD student of University of Guelph professor Mary Ruth McDonald. McDonald carried out the statistical analysis of the field data.

The trial included three treatments: 1) control treatment, where the seed potatoes each received 20 millilitres of water at planting; 2) seed treatment-only, where each seed potato was sprayed with 20 millilitres of inoculum at planting; and 3) seed treatment plus five drenches, where each seed potato was sprayed with 20 millilitres of inoculum at planting, and then each plant was drenched with 20 millilitres of inoculum applied at the base of the stem, at emergence and every two weeks after that.

At harvest, Banks measured tuber yields and determined the incidence of tubers with common scab lesions and the percentage of the tuber surface with scab lesions.

The tuber yields and the incidence of tubers with lesions were not statistically different among treatments. However, the treatment did make a significant difference to the percentage of the tuber surface with scab lesions. Tubers from Treatment 3 had the least surface area with scab lesions.

“The results are promising. A reduction in tuber surface infection is a first step in combatting common scab,” she says.

Some next steps

Banks is planning to do further evaluations of LBUM223 in Ontario fields with mixed populations of pathogenic Streptomyces species. “Fields infested with both Streptomyces stelliscabiei and Streptomyces scabies would be good candidates for such a trial. At harvest, the different Streptomyces species could be isolated from infected tuber samples.”

Research towards field-specific scab management is also taking place in other parts of Canada. For example, AAFC’s Claudia Goyer is the lead investigator of a Canadawide common scab project that includes an examination of the genetic diversity of Streptomyces species and strains in potato-growing regions across the country. Filion, who is one of the collaborators on Goyer’s project, says that the project’s genetic studies are underway in P.E.I., New Brunswick, Manitoba and some Ontario fields. He notes, “So far, we have discovered more than 10 different genetic groups of scab-causing Streptomyces. Some are clearly more virulent than others.”

Another area for research related to a field-specific approach is to determine how different potato varieties respond to the different Streptomyces species and strains. “Each year I evaluate new European potato varieties that, according to their breeders, are resistant or tolerant to common scab. However, in my Ontario common scab research plot, these varieties get heavily infected,” Banks says. “This would support the theory that potato varieties may be susceptible to certain Streptomyces species and tolerant to others.”

Advice to growers

What can potato growers do right now to manage common scab? “In healthy fields, make sure you plant healthy seed. Once the common scab bacterium is introduced into a clean field, it will not go away. It will stay there forever. Picking seed tuber samples at random and washing them should give a good indication whether common scab is a problem or not,” Banks says.

“At present, resistant varieties are the most reliable control method. For example, the early fresh market variety Superior was released 68 years ago with a common scab resistance trait that is still holding. Some Superior tubers may show scab lesions in heavily infested fields but at a very low percentage (one to two per cent).

“Also, pay attention to the ratio of potassium to magnesium and the manganese level in your soil. A potassium-to-magnesium ratio between 0.3 and 0.4 tends to have the lowest common scab severity. And soils with higher levels of manganese have lower scab severity.”

And her final tip is: “Be a researcher. Embed a research plot in a field with common scab and try any method you have heard about or think might reduce scab.”

In a 2019 trial, Banks assessed the effectiveness of a bacterial strain called LBUM223 as a biocontrol agent for managing common scab.

Make more art.

Apply Velum® Prime nematicide in-furrow at planting to increase your yield potential. With a unique mode of action and Group for nematode control, it also has secondary fungicidal properties offering early blight and black dot suppression. Get the most out of your masterpiece, with Velum Prime.

HOT POTATOES

The heat is on to identify potato varieties that can thrive through climate change.

by Rosalie Tennison

With climate change heating up Canada’s crop land, identifying or developing new potato varieties that can grow in warmer temperatures is on the radar of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researchers. Potatoes originated from and still grow wild in the cooler climate of the Andes of South America, and research scientists have often mined these varieties for traits desired in North American cultivars. Canada’s potato-growing areas mimic the cool 20 C daytime temperatures that make the wild varieties so hardy. But what happens when the heat gets turned up?

Xiu-Qing Li of AAFC in Fredericton noticed that warmer summers are creating heat stress in Canadian potato crops. He began studying Canada’s current varieties to see which are the most heattolerant. He also hopes to identify the genes responsible for heat tolerance and to incorporate them into future varieties, either through genetic crosses or directional mutation.

“Climate change threatens the future production of potatoes, but some varieties are more heat-tolerant than others,” Li explains. “We want to continue to grow potatoes, but we need to use varieties that can tolerate heat stress.”

In a paper published in Botany [journal], Li quotes Statistics

Canada data that revealed a 2016 yield decrease in Ontario potatoes of 17.2 per cent compared to the 2015 season. A trend of continuous decreases could severely hamper potato production in Canada and could also pose issues of food security with the rising world population. If the entire production of potatoes worldwide experiences similar yield decline, the future of this nutritious food source could be under threat. Li’s research focuses on getting in front of what could be a potential crisis.

Growers know that developing new cultivars can take a decade or more and, with predicted increases in temperature to be as much as two degrees by the end of the century, if not sooner, plant breeders need to start working towards varieties that can take the heat immediately.

Li and his team put 55 commercial cultivars under heat stress in a laboratory and studied leaf chlorophyll content, plant growth and tuber yield. There were variations in the cultivars’ tolerance to the heat stress but, overall, leaf size was stunted, chlorophyll-index estimates increased and tuber size was reduced. As a result, he says,

ABOVE: Xiu-Qing Li with AAFC in Fredericton is studying Canada’s current potato varieties to see which are the most heat-tolerant.

they were able to identify the most heat-tolerant cultivars currently available to Canadian growers.

“We wanted to understand the impacts of high temperatures on potatoes in the northern climate,” Li explains. “It’s possible that potatoes could be grown farther north if the climate warms up, but the issue will be if they will have enough time to reach maturity. Perhaps we will need varieties that mature earlier.”

Li cautions, “Canada grows potatoes one crop per year, and the potato plants need to tolerate hot summer days in order to continue to grow in the fall. These hot days could potentially impact the tuber and quality negatively.”

Tuber size is reduced under heat stress in all varieties tested but, of those that appeared to be the most heat tolerant, many are the offspring of the industry’s long-time standards, such as Shepody. In fact, Li reports that Shepody performed better than most of the varieties in the study. He adds that Atlantic also performed relatively well under the stressful conditions.

“We need to start addressing heat tolerance in potatoes in order to be prepared for the future,” Li advises. “We need to do further research, and we need to be more proactive about saving varieties that are currently important for the potato industry but are heat susceptible.”

Li’s heat tolerance research is just the tip of the iceberg. He reports wanting to consider improving the performance of plants when they are under stress. Besides developing new varieties, are there cultural practices that could be adopted to reduce the stress from increasing temperatures? For example, how does heat stress affect the growing cycle, and are there production adjustments

growers could make to grow potatoes in a warmer climate?

“We are confident that we can largely resolve the issues,” Li comments. “We are working on several levels in this regard and we think we can improve the production of potatoes using both genetic and non-genetic approaches.”

“Understanding the biology, identifying the involved genes, and improving varieties for heat tolerance are priorities for our research team,” Li adds. More research on heat tolerance in potatoes would be useful and could help focus efforts more effectively, he says.

Canada’s moderate climate is good for potato production, but it can be hampered by a short growing season. If it gets too hot, potatoes may not grow in the traditional growing areas, Li cautions. It may be possible to grow potatoes farther north if earlier maturing varieties can be developed, or harvests may need to be completed earlier, resulting in smaller tubers.

“Climate change is a certainty and temperatures will fluctuate more,” Li says. “Therefore, we need to consider different ideas to reduce heat stress. Perhaps we need to make adjustments at planting or during production. Answering the questions around potato production under heat stress is a priority for my laboratory.”

Li recommends a multi-disciplinary approach going forward. As the climate changes, he suggests all sectors of production need to work together to ensure Canadian potato production remains successful. From a mutational approach to improve heat tolerance of existing varieties, to land and water management, to production activities that can reduce stress during the growing season, Li believes that Canadian potato producers can adapt when the heat is on.

Producing food is getting even more challenging. The window of opportunity for crop protection is limited. That is why every drop must count. Agrifac offers the most stable self propelled sprayer range with the most innovative developments available on the market to ensure that every drop hits the right spot. Want to know more? Visit our website, contact us or ask for a demo! www.agrifac.com

RE-EVALUATION UPDATE: GROUP M FUNGICIDES AND NEONICS

What is the status of Group M fungicides and neonicotinoids in the re-evaluation process?

by Stephanie Gordon

Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) wrapped up, or is expecting to wrap up in 2020, several pesticide re-evaluation decisions for commonly used active ingredients in potatoes, such as Group M fungicides and neonicotinoids.

Tracy Shinners-Carnelley, vice president of research and quality at Peak of the Market, presented on coping with pesticide re-evaluation at Manitoba Potato Production Days held in Brandon, Man. from Jan. 28 to 30, 2020. Shinners-Carnelley provided an update on the Group M fungicides: chlorothalonil, mancozeb, metiram, captan, and neonicotinoids.

PMRA conducts a general re-evaluation of pesticides every 15 years. The re-evaluation process involves reviewing the same areas of data that are reviewed during the registration process. A special review is more specific. A special review can be initiated at any time and focuses on one aspect of concern. For example, the neonicotinoids came under special review because of growing concern about their impact on the safety of pollinators.

“I think [pesticide re-evaluation] has become more of a timely topic for potato growers in the last number of years because so many key active ingredients in the potato industry were either undergoing re-evaluation or special reviews,” Shinners-Carnelley says. “So a lot of us in that industry has been consumed for the last number of years in responding to PMRA consultations, but now we’re at the point where we’re actually seeing final decisions being published and those label amendments being implemented.”

PMRA’s pesticide label search is also available as a free app, called Pesticide Labels, for your mobile device.

Chlorothalonil

Chlorothalonil is a broad-spectrum fungicide used by potato growers to control late blight, early blight and Botrytis grey mould, among other uses in field vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops. Chlorothalonil-containing products are sold under the names Bravo, Echo, and Daconil. It is a Group M fungicide, and

Group M fungicides are an essential component of a potato grower’s toolbox.

“The Group M fungicides are of tremendous importance,” Shinners-Carnelley says. “Between chlorothalonil and mancozeb, these two active ingredients formed the backbone of disease management programs for growers across the country.”

Shinners-Carnelley adds that these

Tamara Carter Co-founder

Carter Cattle Company Ltd. Lacadena, SK

fungicides have a broad spectrum of disease control and a low risk of developing resistance. “So, not only are they effective against the diseases, they also make excellent tank mix partners for many of the newer fungicides that have a medium to higher risk of developing resistance,” Shinners-Carnelley says.

PMRA published the final re-evaluation decision of chlorothalonil on May 10, 2018. Significant changes were made to use patterns for the fungicide, including on potato. Growers must be aware of how they should adjust their use of the fungicide, because all of these use changes must be made before May 10, 2020.

The presentation by Shinners-Carnelley touched on four specific changes that will impact a grower’s workflow with chlorothalonil.

1. A maximum of three applications of chlorothalonil can be applied for potatoes. This is a reduction in the number of applications that was previously allowed.

2. Additional measures, such as personal protective equipment and engineering controls, have been put in place to reduce the exposure of mixers, loaders and applicators of the fungicide.

3. Additional measures – especially around timing – have been added to limit exposure for post-application workers.

Post-application workers involve anyone who enters a potato field after a spray,

the risk to aquatic organisms from runoff. Shinners-Carnelley says that the specifics of what constitutes “downhill” or “aquatic habitats” has not been clarified, and require some more detail. If the downhill slope is steep, the risk of runoff is greater than if the downhill slope is more gradual. However, she does clarify that a vegetative filter strip is different from a “spray buffer zone” that works to protect land and aquatic organisms in case of spray drift – not runoff.

Mancozeb

Mancozeb is one of the most economical broad-spectrum fungicides for early and late blight. Mancozeb-containing products are sold under the names Fortuna, Dithane, and Manzate, among others.

PMRA re-issued a proposed decision for mancozeb in October 2018. The updated re-evaluation decision for mancozeb suggested cancelling all uses of mancozeb except on tobacco due to unacceptable risks to human health and the environment. There was a three-month consultation process that sought feedback from growers on how the fungicide is used in modern potato production and a final decision is expected in June 2020.

Mancozeb is not banned in the European Union or in the United States, having undergone its own re-evaluations in those countries in 2018 and 2005 respectively. Industry members expect a reduction in applications for growers, but not a complete elimination.

“Industry members expect a reduction in mancozeb applications for growers, but not a complete elimination.”

such as agronomists. Post-application workers that are entering the field for scouting can only re-enter three days after an application has taken place. Previously the restricted entry interval (REI) was only two days for scouting purposes. For rouging the REI is 19 days, and for handset irrigation it is 23 days.

4. A vegetative filter strip (VFS) of at least 10 metres must be constructed and maintained between the field edge and adjacent downhill aquatic habitats to reduce

Metiram

Even though the PMRA deemed the metiram fungicide acceptable for potatoes with conditions, BASF decided to discontinue its metiram products anyway.

The metiram active ingredient is a part of two products: Polyram DF (a standalone metiram formulation) and Cabrio Plus (a co-formulation of metiram and pyraclostrobin). For the 2020 growing season, the following changes are in effect:

• BASF may only sell Cabrio Plus or

Polyram DF prior to Dec. 31, 2019.

• Distributors and retailers can continue to sell Cabrio Plus and/or Polyram DF until June 21, 2020.

• Growers can continue to apply Cabrio Plus and/or Polyram DF until June 21, 2021.

Captan

Captan is a Group M fungicide that has not traditionally been used on potato, but after its own re-evaluation process, remains acceptable for use on potato. It is registered for ground and aerial application as long as it’s within the maximum of three applications per season.

Shinners-Carnelley says that it’s a fungicide for future consideration and good to keep in growers’ minds. “My suggestion to growers is to keep this in the back of your mind for future consideration. It is a Group M option, and if we do see a dramatic reduction in the number of mancozeb applications – once we get a final decision on that – perhaps it’s a matter of looking at captan as an option to include in potato management programs going forward, because it will give that broad base of protection and make a good mix partner for so many of the newer fungicides,” Shinners-Carnelley says.

Neonicotinoids

There is less news on the status of neonicotinoids at the current moment. PMRA has been conducting special reviews over the last few years on the insecticides imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam after concerns were raised regarding the effect of these ingredients on pollinators, aquatic invertebrates and squash bees.

The pollinator special review has been completed and the use on potatoes has been maintained, but fuller final decisions on the status of these insecticides are expected in the fall of 2020.

Check the label

When in doubt, growers should consult the most updated label of a product. PMRA states that the official label will be the one in the pesticide registry.

Producers can use the pest control product (PCP) number on the container to search the PMRA label database [pr-rp.hc-sc.gc.ca/ls-re/index-eng.php] and access current labels. PMRA’s pesticide label search is also available as a free app, called Pesticide Labels, for your mobile device.

SMALL AND MIGHTY

Micronutrients are key for potato.

by Julienne Isaacs

The big picture macronutrient requirements of most field crops are well known. Producers might be less familiar with the smaller micronutrient requirements, for one good reason: normally, soils carry enough micronutrients without needing amendments. In the case of potato, a few key micronutrients make a big difference to yield and quality. If they’re deficient, you’ll see problems.

Macronutrients are required in relatively large amounts to keep crops thriving and include nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium and sulfur. Micronutrients - named because plants need them in much smaller, or “micro,” quantities, and not because they’re less essential - include boron, copper, iron, manganese, zinc, nickel, molybdenum and chloride.

For potatoes, the micronutrients researchers are most concerned with are boron and zinc, says Umesh Gupta, research scientist emeritus with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Charlottetown.

“If there’s not enough boron in the soil but the potato is growing rapidly, it’s susceptible to hollow heart,” Gupta says.

Hollow heart, easily identifiable by a star-shaped cavity in the middle of the tuber, is more common in rutabaga or turnip, but when it affects potatoes it significantly impacts quality.

Boron application can be very helpful for potato soils in regions with sandier soils, says Joann Whalen, a professor in the department of Natural Resource Sciences at McGill University. She’s seen reports of boron deficiencies in Australia, the United States and throughout Atlantic Canada.

Zinc is also key for potatoes: the mineral helps with photosynthesis and cell growth and serves as a binding agent in enzyme reactions. If it’s deficient, potato growth is stunted.

Whalen says a study from Iran showed that zinc deficiency in potato caused a reduction in tuber weight as well as the number of tubers per plant.

“If you’re observing some type of unexplained small reduction in the number of tubers per plant, it could be good to attend to zinc concentration in the soil, and follow up with a petiole analysis,” Whalen says.

Petiole or leaf stem analyses should typically be conducted every seven to 10 days during the growing season. “The nutrient requirements change as the plant develops,” Whalen explains. “There are different demands all through the growing season.”

Application rates

Carl Rosen, professor and head of the department of soil, water, and climate at the University of Minnesota, says even when

“Biofortified” potatoes rich in micronutrients like iron, zinc, and copper help promote human nutrition.

boron levels are low, adding the mineral might not result in a yield response, although in some trials it does increase tuber size profile.

Response to other micronutrients depends on the soil, he says. For example, manganese and iron might be deficient on high pH soils, while copper and manganese might be low on organic soils.

“Have soil tested for micronutrients and pH before planting; during the growing season, sample petioles and have them tested,” he says.

Micronutrients are not mobile in the plant, so symptoms of deficiency appear on the younger leaves first then spread to lower leaves in severe cases.

PHOTO

But while producers should be on the alert for micronutrient deficiencies in the crop, they should be careful not to overcorrect if a soil or petiole test shows levels are low.

Overapplication of boron can result in toxicity, impacting yields.

For boron, recommendations are usually one to two pounds per acre; toxicity can result if boron is applied at 10 pounds per acre, with cupping of leaves and sometimes necrosis of the leaf margins, Rosen says.

Boron is commonly available in North America through a company called 20 Mule Team that produces solid borax as well as a soluble version called Solubor. As a foliar spray the product should be applied before flowering or tuber formation, Whalen says; it can be applied with an adjuvant that aids absorption through the leaves.

According to Gupta, plant health is only one reason producers should keep their eye on the micronutrient requirements of their potato crop: micronutrients are also key for human health.

“Biofortified” potatoes rich in micronutrients like iron, zinc and copper help promote human nutrition.

Three decades ago, boron was not considered essential for human health, but now it’s been linked to memory, cognitive function and bone strength. Zinc helps activate enzymes that remove free radicals and limit oxidative stress.

Optimal quality and yields are typically considered the chief goal for potato production, but Gupta says human health needs to stay on the agenda. “We have to remember potatoes are consumed by humans. They should contain sufficient nutrients so people are getting them in their diet,” he says.

NUTRITION DIAGNOSTICS TOOL

In 2018, the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), J.R. Simplot Company and Tennessee State University collaborated on a plant nutrition diagnostics tool for potato producers. The publication, which includes high-resolution photos of a range of nutrient deficiency symptoms, can be found at www.ipni.net/ article/IPNI-3478.

A HELPING HAND

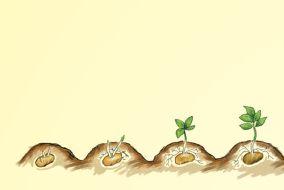

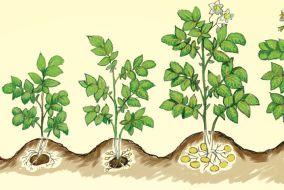

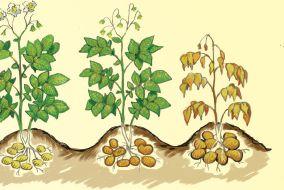

Research studies show that nurse crops can help potatoes get off to a good start and also provide benefits throughout the growing season.

by Mark Halsall

Cover crops are known to help prevent soil erosion and boost organic matter in potato fields when planted in the fall after harvest. Now, scientists at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) are looking in the question of whether nurse crops – fast-growing companion plants that are planted a day or so before the potato seed and then terminated just prior to seedling emergence – can provide similar benefits.

Sheldon Hann, a biologist at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre (FRDC) in New Brunswick, has been analyzing data from two AAFC studies that assessed the value of field pea, winter rye and spring barley as nurse crops in potato production.

Hann oversaw the nurse crop studies at the FRDC and worked with a number of other AAFC researchers including soil scientist Judith Nyiraneza, who lead the nurse crop studies at the Charlottetown Research and Development Centre in Prince Edward Island.

Among the research findings were indications that the nurse crops helped to keep weeds at bay and also prevented soil erosion in the crucial first few weeks before the potato shoots emerged. Another benefit was that when tilled into the soil during hilling, the nurse crops provided an important nutrient source in the form

of green compost and also helped to retain moisture in the potato hills throughout the growing season.

“It also has the benefit of adding another biological component in the mix. Studies have shown that increases in crop diversity can influence the microbial communities in the soil and the soil health equation,” Hann says.

According to Hann, field pea, winter rye and spring barley were chosen for studies because of their ability to be seeded early, germinate quickly and establish reliably.

In addition to comparing the efficacy of the different nurse crops, the researchers also assessed different seeding methods and rates to see which had the most impact on yield. For field pea, for example, a high seeding rate achieved higher yields than a lower seeding rate, while for winter rye, the opposite was true.

Two different methods for stopping the nurse crop growth involving mechanical hilling with and without chemical desiccation were evaluated. Two desiccation products were also assessed in one of the studies.

ABOVE: Sheldon Hann, a biologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, checks the health of potato plants grown with nurse crops.

The nurse crop research in Fredericton included a three-year study and a one-year project, which both concluded in 2017. Since then, Hann has been going over the results and analysing the large number of soil and plant samples that were taken during the trials to better understand the mechanisms that enable nurse crops to benefit potato production and also provide some guidance for future research in this area.

Nyiraneza believes that nurse crops could prove to be particularly useful for potato production in Eastern Canada.

“The key to good productive land is soil with high organic matter. Soil types in some parts of Eastern Canada can make it hard to keep that organic matter, and when you combine that with row crops that don’t leave behind a lot of plant residue and frequent soil tillage, you can quickly find yourself with depleted amounts of organic matter,” she says.

“Nurse crops can be part of the solution to the soil nutrient loss and drought conditions that have led to declining potato

yields in Eastern Canada. When they are tilled into the soil, they act as green compost and help with water retention throughout the growing season. With better access to nutrients and water, we saw improved potato yields in some cases.”

Hann agrees that nurse crops offer a number of important benefits that could contribute to the success of an integrated management system for building soil quality and health.

“We have to look at the whole system and how that system can be best managed. Nurse crops may be one component of that, but in the grand scheme of things, we need to have more of an integrated approach,” he says.

Hann notes that common questions during discussions with industry and project partners include what costs are associated with adding nurse crops into a potato rotation and what are the specific yield benefits.

Farmers, he says, want to know if increases in yield will cover the extra expenses that accompany the implementation of nurse crops in the potato rotation, such as nurse crop seed and products for desiccating the nurse crops. According to Hann, it’s a question that remains to be answered.

“I think this is something that we need to really dig into with the data that we’ve collected from our trials as well as from other studies,” Hann says. “It comes down to a budgeting – if I put this much in, how much am I going to get out? I haven’t run that economic analysis yet, but it would be really interesting to be able to do that and see the results.”

Nyiraneza points out that in addition to economic factors, there are other important considerations, such as time requirements and logistical issues associated with implementing a nurse crop system.

“It’s in the early stages,” she says. “To me, everything has to be well-studied and understood before this practice can be adopted on a large scale.”

Potatoes growing amongst a terminated nurse crop.

A nurse crop biomass sample being collected.

Field pea seedlings emerging in a potato plot.

Your potato crop has many enemies but FMC has your back with six trusted tools for when you need them most.

Tank-mix with Reglone® Desiccant for more complete vine kill, leading to better tuber quality.

Fast uptake for superior in-furrow control of CPB and potato flea beetle.

Reliable aphid control, unique anti-feeding action and beneficial-friendly.

Short 7-day PHI.

Residual control of European corn borer and Colorado potato beetle. Reduced risk product and beneficial-friendly.

Short 1-day PHI.

Consistent, systemic control of leafhoppers.

Short 7-day PHI.

Systemic, residual control of sucking and chewing pests, including Colorado potato beetle, European corn borer, armyworms, flea beetles and aphids.

Short 7-day PHI.

Is pink rot on your radar?

Defend your crop with Orondis Gold.

Applied in-furrow, Orondis® Gold fungicide goes to work early in the season, protecting your potatoes throughout the year from damaging diseases such as pink rot and Pythium leak. Orondis Gold combines the power of metalaxyl-M (Group 4) with oxathiapiprolin (Group 49) – a new mode of action to suppress pink rot and help manage resistance. For more information, visit Syngenta.ca, contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or follow @SyngentaCanada on Twitter. Always read and follow label directions. Orondis®, the Alliance Frame and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. © 2019 Syngenta.