LINKING MICROBES TO

MAKE TIME FOR WHAT REALLY

You’re proud of your potato crop. Let’s face it. No one ever looks back and wishes they’d spent more time controlling crop damaging, yield robbing insects. We get that. DuPont™ Coragen® is powered by Rynaxypyr ® , a unique active ingredient and a novel mode-of-action that delivers extended residual control of European corn borer, decreasing the number of applications needed in a season. And, if your Colorado potato beetle seed treatment control breaks late in the season, Coragen® can provide the added control you need, so you have time for more important things. Its environmental pro le makes Coragen® a great t for an Integrated Pest Management Program and it has minimal impact on bene cial insects and pollinators when applied at label rates.1 For farmers who want more time and peace of mind, Coragen® is the answer. Questions? Ask your

TOP CROP

MANAGER

8 | Linking soil microbes to yields Working towards using soil microbial communities as a tool for improving potato crop productivity.

By Carolyn King

THE EDITOR 4 Keeping potatoes healthy By Stefanie Croley, editor

15 | Deadly companion – in a good way A companion planting attract-and-kill method for effective, lower-risk wireworm control.

By Carolyn King

Julienne Isaacs

ON THE WEB

19 | Researchers look to soil for scab solutions

Controlling common scab is a challenge, but work continues to unravel the puzzle.

By Rosalie I. Tennison

By Julienne Isaacs

21 Faster identification of PVY resistance By Rosalie I. Tennison

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITOR

KEEPING POTATOES HEALTHY

Thanks to the power of technology, curated news is delivered straight to my inbox each day, making it easy for me to keep up with the latest trends, technologies and happenings in the world of agriculture.

Admittedly, the system is a bit flawed, as some of the potato-related headlines aren’t the exact type of news I’m after. Without fail, a new recipe featuring potatoes lands in my inbox, and although the dish may look and sound mouth-watering, it’s not the type of potato “news” we look for to share with readers of Potatoes in Canada

However, when a story about an Australian man who ate nothing but potatoes throughout 2016 made headlines late last year, I couldn’t help but click the link. Andrew Taylor, a 36-year-old man from Melbourne, Australia, told the International Business Times he was addicted to food and at the end of 2015, he decided enough was enough. He resolved to find one healthy food he could eat every day and quit everything else. Taylor said he conducted considerable research and settled on potatoes because they provide a balanced source of nutrition. At the time of this writing, Taylor had reported losing a total of 52 kilograms, or 115 pounds. He said he plans to continue the diet, with a few modifications, into 2017 and has even dedicated a website – www.spudfit.com – to his journey.

Taylor maintains the challenge is not intended to be a weight loss program, and while this isn’t the type of news you’ll see covered in our pages, there’s a link between Taylor’s story and the research’s ongoing quest to find healthier potatoes. We’ve covered new varieties with added health benefits before – everything from potatoes with lower glycemic responses, to a potato extract that could do exactly what Taylor set out to do: fight obesity and help with other health issues. Perhaps Taylor’s story may bring more light to the benefits potatoes have to offer, which can only help potato scientists across Canada and the world continue their efforts to breed spuds with significant health benefits – a win-win, if you ask me.

In this issue of Potatoes in Canada, the focus shifts away from what the potato can do to keep you healthy, and more toward what you – and some of Canada’s top potato researchers – are doing to keep the potato healthy. As we approach another growing season, pest and disease concerns will soon be at the top of your mind. If the wireworm is a particular threat to your crop, you’ll love reading about Bob Vernon’s new attract-andkill method for wireworm control on page 15. Though still in its early stages, the project shows great promise and it’s something we’ll be keeping our eyes on in the future.

And on page 5, you’ll find an update on new technology out of Fredericton that’s speeding up potato breeding to improve disease and nematode resistance, as well as other processing and agronomic traits. Benoit Bizimungu and his team are using a polymerase chain reaction machine to screen for variants of DNA linked to certain traits, and Bizimungu says this technology will significantly speed up the breeding process. Whether your potato interests lie on the breeding side or the growing side, we hope you find valuable information among our pages. Best wishes for a safe and prosperous growing season.

TOP CROP

POTATOES IN CANADA SPRING 2017

EDITOR Brandi Cowen • 888.599.2228 ext 278 519.410.4410

ext 245 226.931.0375 • dlabrie@annexweb.com NATIONAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Sarah Otto • 888.599.2228 ext 237 519.400.0332 • sotto@annexweb.com ACCOUNT COORDINATOR

ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIRCULATION e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940

FAST-TRACKING TRAITS FOR IMPROVED POTATO VARIETIES

New technology is speeding up potato breeding at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre.

by Julienne Isaacs

Benoit Bizimungu is quick to identify top breeding priorities for implementing marker-assisted selection at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Fredericton Research and Development Centre.

The team’s first focus is on disease and nematode resistances that are difficult or expensive to screen using traditional methods; next come processing traits like specific gravity and chip colour after cold storage. Eventually, his team will look at agronomic traits.

These priorities are not necessarily based on the researchers’ preferences, but rather on the availability of genetic markers – in other words, markers linked to disease or pest resistance are easier to find because those traits tend to be genetically simple. Traits linked to processing qualities, such as chip colour, are a little more complex. Agronomic traits, such as yield, are more complex still, as they are under the influence of multiple genetic effects.

Bizimungu is a research scientist and a lead on a new project that will use DNA sequencing technology to improve the efficiency of potato breeding projects.

Supported through AAFC peer-review funding, the project is connected to the Integrated Potato Research-Development and Technology Transfer project, which runs from April 2015 to March 2019.

“Research activities are conducted in four streams, with a strong breeding component aimed to develop ‘eco-potato’ germplasm with suitable end-user traits,” Bizimungu says.

“What we are looking for in this project is the improvement of breeding efficiency, and breeders have always relied on many tools to develop a new variety. This new equipment is allowing us to genotype, to determine the sequence in key specific genes of interest, very rapidly, and to identify the desirable variants of genes underlying important traits.”

The new technology in question is a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine that works as a “high-throughput genotyping platform” to help researchers screen for variants of DNA linked to traits of interest in large numbers of samples of genetic material.

“Most of the progress in large-scale genetic polymorphism analysis and related instrumentation is coming from biomedical research in human genetics, but we are slowly adopting it in plant research,” Bizimungu explains. Most real-time PCR machines can run 69 reactions, but this one has the capacity to run 1,536 reactions in minutes,

ABOVE: Benoit Bizimungu stands in front of an automated liquid handler, a piece of lab equipment that can prepare more than 1,500 DNA samples in a matter of minutes.

representing 16 times more capacity than most other machines. The ability to screen so many samples at once is particularly key for potato breeding programs, where researchers are used to growing out thousands of samples in the field and laboriously combing through them looking for expression of key traits.

High-throughput genotyping means all of the samples can be screened in the lab, whittling down the number so only promising candidates are trialed in the field later on.

“We’re able to fast-track traits to improve varieties and identify superior genetic combinations earlier in the breeding program than we would using conventional screening methods only,” Bizimungu says.

A collaborative approach

Fredericton researchers are not alone in this sophisticated approach to potato breeding. Bizimungu says the team is working in collaboration with other researchers developing markers both in Canada and internationally. “This lab is mostly for rapid routine screening, and we integrate new markers as they are developed by collaborators,” he says. “We try to keep ahead of the new developments.”

In particular, Bizimungu’s lab is working with scientists and breeders from the United States. Many of the advances they are able to take advantage of are the result of a four-year United States Department of Agriculture project called the Solanaceae Coordinated Agricultural Project (SolCAP), which ran from 2008 to 2012. SolCAP aimed to translate genomic advances in other fields to American tomato and potato breeding programs; all of its results were made publicly available.

“The project resulted in excess of 20,000 genome-wide sets of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers,” Bizimungu says. “And we’re just starting to make good use of some of those.”

How does the process work? Using already-identified markers linked to traits of interest, the team develops primers to target those markers in samples using the real-time PCR machine. Samples that include traits of interest could end up in breeding programs later on.

The Fredericton team’s approach for using marker-assisted selection was to start with simply inherited traits like disease resistance. “In terms of applying this technology, we started with the markers that are available,” Bizimungu explains. “We started with disease resistance because these are under simple genetic control, but we expect more progress is being made for other, more complex traits as well.”

Bizimungu’s team has already started applying these new disease resistance traits to the breeding program. Later this year, they hope to start incorporating processing traits, which Bizimungu says are more complex, and can be affected by environmental factors.

Using information generated by SolCAP, the team plans to tackle specific gravity, chip colour and sugar levels in processing potato varieties.

Agronomic traits are more difficult to apply in breeding because they are so much more complex, relying on a wide variety of factors. But Bizimungu says as researchers find more information on genes and genetic variations involved in those traits, they can try to target those traits as well.

“With this instrument and markers in general, one of the advantages is that it reduces the size of a breeding population by culling out undesirable types in early generations to enable a more thorough assessment of fewer clones in field evaluations,” he says. “So it improves efficiency.”

It will take a little while before producers see these new traits at work in the field, but Bizimungu says the new technology will speed up the process considerably.

“Breeding is a production line – something comes out every year and something is fed into the pipeline every year. The beauty of this high-throughput system is that it brings these markers into the first year of breeding. We’ve never been able to do this before,” he says.

“In the end, there will be less material going into fieldwork, but the fieldwork we do will have a greater chance of being successful.”

Bizimungu places a plate for collecting DNA samples into the automated liquid handler that will fill the plate with DNA samples.

New Velum Prime. The biggest news in nematode protection – ever.

Velum™ Prime nematicide is here, making yield-robbing nematodes a worry of the past. Integrate it into your nematode protection program by applying it in-furrow at planting. And give your potato yield a chance at being one for the ages.

Learn more at cropscience.bayer.ca/VelumPrime

LINKING SOIL MICROBES TO YIELDS

Working towards using soil microbial communities as a tool for improving potato crop productivity.

by Carolyn King

With the help of DNA sequencing, Canadian researchers are linking soil microbial communities to soil health and potato yields. This research is the first stage in eventually developing a tool to diagnose the health of potato fields and to help identify management practices to improve tuber yields and quality.

“We believe the health of our soils is important in controlling productivity, and we have often thought that the soil microbial community is tied into soil health. But the challenge has always been: How do you measure soil health and how do you measure microbial communities?” explains Bernie Zebarth, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). “It is only recently that we finally have the molecular tools to truly characterize the soil microbial community on a more routine basis, to actually run hundreds of samples instead of just individual samples. This research is our first chance to try that – to see how a microbial community varies in a landscape and if it is related to productivity.”

The researchers found soil pH was the most important factor influencing the changes in the bacterial community’s diversity across the landscape. The community tended to be more diverse when the pH was close to neutral and less diverse when the soil was acidic.

Zebarth and Claudia Goyer, a molecular bacteriologist with AAFC, are collaborating on this research, which is funded by Potatoes New Brunswick, McCain Foods Canada, PEI Potato Board, Manitoba Horticulture Productivity Enhancement Centre Inc. and AAFC.

Their research is part of a major, industry-led initiative to determine how to overcome limitations to productivity in Canadian potato fields. A key aspect of this multi-component, five-year initiative is to understand and address in-field variability in the growth and yield of potato crops. “As part of this initiative, we

<LEFT:Results from samples along a 1,100-metre transect in this field showed soil pH was the most important factor affecting the diversity of the soil bacterial community.

BOTTOM: The researchers hope their work will help overcome limitations to productivity in Canadian potato fields.

<LEFT: Researchers are collecting soil samples for microbial community analyses to determine how these communities are related to soil properties and potato yields.

wanted to develop different tools, including this work to look at using microbial communities as a tool for assessing soil health,” Zebarth says.

“Ideally, [with such a tool] you would be able to analyze a microbial sample from a field, and the results would tell you if the field is healthy or unhealthy, or somewhere in between. And maybe knowing the nature of the microbial community might tell us how to intervene – if you have this kind of community, then you need this kind of practice to improve it. So that’s our long-term goal, but we’re still really early on in the process.”

Next-generation sequencing

Goyer explains advances in DNA-related technologies have made this research feasible. Over the past 10 or 15 years, the cost of DNA sequencing has plunged. At the same time, the power of the technologies, including the capacity to handle massive amounts of data, has shot up.

“For microbiology these days, it’s really an exciting time. It’s a revolution,” she says. “With a new technique called next-generation sequencing, it has become much easier to look at microbes in soil. That is opening a lot of new research avenues.”

As an example, information on the soil microbial community could help in controlling a soil-borne disease. Any pathogen is part of a larger soil microbial community with many different organisms and complex interrelationships between the organisms. Some of those organisms might increase the target pathogen’s impact on the crop by creating an opening for the pathogen to attack. But others might outcompete that pathogen for positions on the roots of the crop, while others might counteract the pathogen’s effects on the crop because they perform functions for the crop plants, like producing phytohormones that enhance plant growth and yield, triggering the plants’ defence mechanisms against the pathogen, or making nutrients available to the plants.

“So sometimes when we use an agricultural practice to control a disease, we don’t always know why it is working or not working in certain fields,” Goyer says. “But with nextgeneration sequencing, we are finally able to know which microbes are there. And once we understand what is there and why it’s there, and whether it is associated with yield or not, then we can make progress in terms of making microbial communities work for us.”

In this current research, Goyer is using a method of next-generation sequencing called amplicon-based metagenomics that focuses on just the bacterial and fungal communities and allows the research team to analyze a lot of samples at a reasonable cost. The disadvantage of this method is that it cannot identify organisms to the species level, which would be necessary

PHOTOS COURTESY OF BERNIE ZEBARTH.

if you want to find out whether a particular pathogen is present. However, it is possible to do an additional test, like quantitative or digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to see if a specific pathogen is there.

Microbes and landscape

For this research, Zebarth and Goyer are conducting a series of studies. The first study, conducted in 2014, involved sampling along a 1,100-metre transect in a commercial potato field in New Brunswick. They wanted to see how the soil microbial communities varied across the landscape and whether those variations were related to changes in soil properties and topography.

The research team collected soil samples at 83 points along the transect, sampling at the upper-, mid- and lower-slope positions on the hills and depressions of the field’s rolling landscape. They analyzed the samples for the bacterial and fungal communities and for key soil properties including texture, moisture, pH, organic carbon and total nitrogen.

Soil pH was quite variable in this field, ranging from 4.3 to 7.0. “We found that the steeper the slope, the lower the soil pH. We believe that is because of erosion. Our subsoil is acidic and with more erosion, you remove more of the surface soil, exposing the acidic subsoil,” Zebarth explains.

The researchers found soil pH was the most important factor influencing the changes in the bacterial community’s diversity across the landscape. The community tended to be more diverse when the pH was close to neutral and less diverse when the soil was acidic. Organic carbon levels also had some influence on bacterial communities, with higher carbon levels associated with greater diversity.

Fungal community diversity was influenced by organic carbon levels, but not by pH.

Microbes and compost

In 2015, Goyer and Zebarth started a small-plot study to evaluate the effects of different types of compost on the microbial

communities. They compared four treatments: composted forestry waste, composted poultry manure and forestry waste, composted curbside waste, and a control with no compost. The three composts had very different characteristics, particularly in terms of the amount and quality of organic carbon and the amount of nitrogen. For example, the composted forestry waste had a lot of lignin, which is hard for microbes to break down; the composted manure/ forestry waste had a medium amount of lignin; and the composted household waste had no lignin.

The treatments were applied in the fall of 2015. Soil samples were collected that fall, and then in the following spring before planting potatoes, during the growing season and after harvest, to find out how the microbial communities changed over time and how the communities were related to tuber yield and quality.

The preliminary results for this study show the compost treatments initially had a very big impact on the microbial communities. Over the course of the year, those communities gradually became more similar to the community in the control treatment.

The composted curbside waste had the longest lasting effect on the microbial community. Goyer thinks this has to do with the quality and amount of organic carbon in household wastes. “These wastes are much easier and faster to decompose, resulting in different kinds of compounds in the compost. This composition seemed to stimulate more development of a more varied microbial community compared to the other treatments.”

According to Zebarth, it makes sense that the microbial communities would eventually return to something close to their original condition. “The soil has a huge pool of organic matter. By adding some organic matter, we can influence it, but it is such a large pool to begin with that you would expect it to have a certain amount of stability.”

Microbes and fumigation

In another study, the researchers are comparing fumigation using Vapam to no fumigation. In the fall of 2015, the replicated treatments were applied to large-scale strips in a commercial field in

Researchers are evaluating the response of microbial communities to different compost treatments and seeing how that relates to potato yields.

Manitoba. Each strip has several sampling points along it.

“We’re following that study over two years, with sampling starting before fumigation, through the following potato crop and then through the following rotation crop,” Zebarth says. “We want to see how fumigation affects the microbial community and then how the community bounces back afterwards.”

The samples are being analyzed for key soil properties and the bacterial and fungal communities. As well, the samples are being tested for specific pathogens, including Verticillium dahliae, the species that causes Verticillium wilt.

Microbes and spatial variability

Goyer and Zebarth will be starting yet another study in 2017 to see if they can link the microbial community to tuber yield and quality.

Zebarth explains, “At two sites in New Brunswick, we have done a detailed study on spatial variability. In each field we have about 150 sampling locations in a grid. The original focus of this research was the spatial variability of yield and soil properties. We are going to choose one of those fields and determine the microbial communities as well.” Goyer is very interested in seeing how the communities differ between the high-yielding and low-yielding areas of the field.

Next steps

In the next few years, Goyer and Zebarth are planning to look at how other agricultural practices affect microbial communities. In particular, they want to assess the effects of growing mustard.

“Mustard contains compounds called glucosinolates that break down in the soil to form isothiocyanate, which is a biofumigant that can change the microbial community. Also, mustard normally has a lot of organic matter that is returned to the soil. The biofumigation and the residues themselves make a huge change in the community and it is thought to help control diseases,” Goyer explains.

“We want to better understand this because in New Brunswick it seems that Verticillium wilt might be part of the cause of lower potato yields. We’d like to see if mustard or other high biomass crops can change the community enough to displace the Verticillium pathogen in those fields.”

As well, the researchers are working on tools for high-throughput quantification of key pathogens. “That’s where I want to go because I find that we’re missing part of the picture at the moment,” Goyer says. “In the long run, I’d like to be able to determine what the microbial community in general is doing and what the major pathogens are doing. Those are the two critical pieces of data.” Although methods to identify specific pathogens are available, they are time consuming if there are many samples that have to be analyzed for multiple target species.

Looking ahead, Zebarth says, “We are in the really early stages and we have a long way to go. But the technology is advancing. People are talking about, at some point, being able to have a little chip that you can take into the field and analyze DNA. So maybe in a decade or two you’ll be able to characterize your microbial community right in the field and be able to say this field is great or this field is not so good, and to say which practices would help.”

BACK TO TESTING BASICS

Ontario growers welcome spore trap research for late blight.

by Julienne Isaacs

There are other, more sophisticated methods of testing for the presence of late blight spores in growers’ fields, but that’s precisely the reason Eugenia Banks selected a very simple test for her 2016 project.

“The main objective when you do research is that growers could use the results in the future. Growing potatoes is such a demanding job and growers don’t have the time to do complicated things,” Banks says.

Banks, who retired as potato specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) in 2015, is now the lead on a two-year Ontario Potato Board project evaluating one type of spore trapping technology in order to help growers improve late blight management. Funded in part through Growing Forward 2, the project involves the installation of “passive spore traps” in the Shelburne and Alliston potato growing areas to monitor the presence of late blight spores.

“I decided on these spore traps for late blight because they had never been researched in Ontario before,” Banks says. “I worked with two grower co-operators and they were very happy to have this project,

especially because it didn’t disturb their management practices.”

Two passive spore traps were installed on each grower’s farm early in the 2016 growing season, close to potato fields where it was windy or where there had been late blight in the past.

Banks supplemented the spore traps with in-field scouting twice a week, as well as drone surveying once a week.

No late blight spores were found in the traps until July 7, when Banks found spores in both the Shelburne and Alliston traps. Growers in the area were immediately alerted by email, Banks says, and most of them opted to spray a late blight specific fungicide, even though scouting did not reveal any signs of infection in the fields. Spores were later trapped on Aug. 15 and Sept. 19.

But Banks says the traps’ effectiveness is proved in part because 2016 was such a dry year with conditions that aren’t normally favourable to late blight. In fact, it was the hottest, driest year the province has experienced in 100 years, and no late blight was reported in fields.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF EUGENIA BANKS.

ABOVE: The passive spore trap used by Eugenia Banks in this study consists of a funnel with an attached vane.

“The traps will be evaluated again in 2017,” she says. “That will be a good test because I don’t think that Mother Nature will send us the same weather.”

How passive spore traps work

Banks contrasts passive spore traps with their more complicated cousin, volumetric spore traps. The latter type of trap must be connected to a power source because it opens and shuts at set times, allowing researchers to measure the number of spores trapped in a particular volume of air.

Passive spore traps do not require a power source. They consist of funnels containing mesh filters called “cassettes” that trap spores carried by the wind. Passive traps are not moved and remain permanently open to the wind; researchers don’t know the volume of air passing through, but they change the cassettes twice a week, sending them to a lab for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The test measures the concentration of late blight spores as “low” “medium” or “high.”

“It’s easier for growers to use the passive type,” Banks explains. “We find that the passive traps are more adequate for our objectives: to detect the spores. We are not so interested in the number of spores, because late blight is such a devastating disease that if the spore traps get spores, it means that they’re in the air and growers should switch to a late blight specific fungicide immediately.”

Banks says researchers in the Netherlands have been able to show that infection in a single plant can cause an outbreak of late blight. “Just one viable spore landing in good conditions will produce lesions, and the lesions will expand and it will be explosive,” she says.

The traps are relatively inexpensive and lab tests cost just $25 each – a small price to pay compared to the economic losses wreaked by late blight in unprotected fields.

Growers have been extremely receptive to Banks’ research, she says, and once the research is completed in 2017, some of them are considering installing their own passive spore traps in high-risk areas.

First, though, Banks wants to gather more data. If 2017 is a rainy year with conditions favourable for late blight, she can measure the trap’s effectiveness in all conditions.

“Spore traps represent another tool to be added to the potato growers’ arsenal to combat late blight,” Banks says. “If late blight spores are not detected by the traps, growers should still follow a preventative fungicide program and apply a fungicide spray before rows close. Also, fields should be scouted regularly.”

TRACKING LATE BLIGHT’S ROOTS

New research from North Carolina State University (NC State) has tracked the evolution of differing strains of the major pathogen responsible for late blight disease in potatoes around the world.

NC State plant pathologists studied 12 key regions on the genomes of 183 Phytophthorainfestans pathogen samples – including both historic and modern samples – from across the globe. They discovered that a lineage called FAM-1 caused outbreaks of potato late blight in the United States in 1843 and then two years later in Great Britain and Ireland. FAM-1 caused massive and debilitating late blight disease outbreaks in Europe, leaving starvation and migration in its wake.

According to study results published in PLOS ONE , FAM-1 was also found in historic samples from Colombia, suggesting the pathogen had its origins in South America.

Jean Ristaino, the William Neal Reynolds distinguished professor of plant pathology at NC State and the corresponding author of the study, theorizes that the pathogen either arrived in Europe via infected potatoes on South American ships or directly from infected potatoes from the United States.

But FAM-1 wasn’t just a one-hit wonder that made its mark and then quickly disappeared.

“FAM-1 was widespread and dominant in the United States in the mid-to-late 19th century and the early 20th century,” Ristaino said, in a press release. “It also was found in Costa Rica and Columbia in the early 20th century.”

FAM-1 survived for about 100 years in the United States but was then displaced by a different strain of the pathogen called US-1.

“US-1 is not a direct descendant of FAM-1, but rather a sister lineage,” Ristaino said.

US-1, in turn, has been elbowed out of its eponymous homeland by even more aggressive strains of the pathogen that have originated in Mexico. She explained that winter vegetable crops, grown in Mexico and imported into the U.S., can harbour the pathogen.

The pathogen’s effects aren’t limited to the decimation of Ireland’s potato crop 170 years ago. Billions are spent worldwide each year in attempts to control the pathogen, Ristaino added. Potatoes in the developing world are particularly vulnerable as fungicides are less available and expensive.

According to 2015 estimates from Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC), producers in North America, Europe and developing countries spend approximately $1 billion on fungicides for late blight control every year. AAFC estimates the total global financial cost of late blight, including the price of fungicide applications and direct crop losses due to the disease, ranges from $3 to $5 billion every year.

Co-authors on the paper include Amanda Saville, a research technician in Ristaino’s lab, and Michael Martin, an associate professor with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s department of natural history.

The research was supported by a grant from the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Inside the funnel is a spore trap mesh filter, called a “cassette.”

DEADLY COMPANION –

IN A GOOD WAY

A companion planting attract-and-kill method for effective, lower-risk wireworm control.

by Carolyn King

Researchers are hoping Canadian potato growers will soon be able to use an innovative approach to control wireworms. This method uses just a few grams of insecticide per hectare applied to cereal seeds that are planted along with untreated seed potatoes. It provides very good wireworm control for the whole growing season, with a lower environmental risk than currently available insecticide options.

“We’re very excited about this delivery system for controlling wireworms,” says Bob Vernon, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). He and his research team developed this method by drawing on their in-depth knowledge – gained through their many wireworm control studies – of when and how these soil-dwelling larvae feed.

In the spring, about 100 per cent of the wireworm population in a field rises to near the soil surface to feed on plants. Wireworms really like cereals and grasses, but if those aren’t available they’ll eat other crops. In the summer, the wireworms go deeper down to escape hot, dry weather. Then, in late summer, they rise to feed again. As winter arrives, they descend once more. In potato crops, this pattern means wireworms can attack both the mother tubers and daughter tubers.

They tunnel into the tubers, reducing marketable yields.

“Wireworms find their host material by following carbon dioxide trails emitted by germinating or respiring plants in the soil,” Vernon explains. “For example, as a wheat seed germinates, it produces carbon dioxide. Since wheat is planted in distinct rows, you’ll get very nice carbon dioxide plumes coming from those rows, which will attract wireworms. Once they get to the carbon dioxide source, they’ll feed on the wheat seeds or roots. The same thing happens with potatoes: after planting, the mother tubers eventually start to germinate and produce carbon dioxide and respire, attracting wireworms.”

Vernon and his research team realized they might be able to use the wireworm’s food detection system against the pest. “The idea that we had going back about 16 years is that you could put a cereal crop such as wheat in with the potatoes, much like putting a granular insecticide with potatoes at planting. Wheat tends to germinate

ABOVE: In a novel control method, insecticide-treated wheat seeds are planted with potatoes. The wheat germinates first, emitting carbon dioxide that draws wireworms right to the insecticide.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF BOB VERNON.

more rapidly than the mother tubers do, so pretty much all of the wireworms in the field will be attracted to the wheat seed and won’t be as inclined to go to the mother tubers. Now, if you put something lethal on the wheat seed, then you’ll kill most of the wireworms early in the season,” he says.

“Because you are drawing the wireworms right to the poison, you can use far less of it than you would, for example, using Thimet [phorate] or Capture [bifenthrin]. With Thimet or Capture, you’re expecting that the wireworms will encounter the insecticide by chance, so you have to use more of the insecticide and it has to be more spread out.”

Vernon’s group started working on this companion planting attract-and-kill approach in the early 2000s. They have tested virtually all of the available insecticides to see which ones would work best with this approach. The method requires an insecticide that kills wireworms; if the product just temporarily knocks out or repels wireworms, the pests might return later to attack the daughter tubers. Vernon notes, “At the present time, of the insecticides registered [for wireworm control in potatoes], Thimet will kill and chlorpyrifos [Pyrinex] will kill. Those are registered on potatoes as in-furrow granular or spray applications. They are not really available to be put onto cereal crops.”

So to demonstrate the attract-and-kill method, his team has used fipronil. This insecticide, with the product name Regent 4 SC, is registered in the United States for use on potatoes and corn.

Vernon’s studies show very low doses of fipronil are quite effective when used with the attract-and-kill method. “For example, we can get the same result as with Thimet 15G but with between about one and five grams of active ingredient fipronil per hectare,” he explains. “To put that in perspective, Thimet is used at 3,250 grams of

active ingredient per hectare. So, we’re looking at up to about 3,000 times less active ingredient being put into the soil at planting using the cereal crop attract-and-kill approach with a product like fipronil. And the toxicity of fipronil relative to Thimet is about 100 times less.”

This method gives about 80 to 90 per cent wireworm kill early in the growing season. The small remaining population will cause much less damage to the daughter tubers.

Another positive aspect of this approach is that the risk of other insects and mammals being exposed to the insecticide is reduced. “The treated cereal seeds are about 15 centimetres below the ground surface, and the insecticide is not broadcast over a larger area,” Vernon says. “And if you start with one gram of active ingredient per hectare, then by the end of the summer only about 0.1 or 0.2 grams per hectare would remain in the soil.”

Field experiments show potato yields are very rarely affected by competition with the companion crop. Vernon notes, “We have been able to determine the minimum amount of wheat seed needed to kill wireworms and protect the daughter tubers from blemish damage. We know how much wheat to put in the rows and where to put it so the wheat will not interfere with the growth of the potatoes.”

According to Vernon, growers would need to make some fairly simple, low-cost modifications to their existing planting equipment in order to sprinkle the wheat seeds in with their potatoes.

The one obstacle to adoption of this method at present is that fipronil is not registered for use with potatoes in Canada. When Vernon started working with fipronil, he was hopeful it would eventually be registered here, but that didn’t happen. However, his team is testing new insecticides every year, and he is “cautiously optimistic” they’ll find a product that can be slotted into the companion planting attract-and-kill approach.

Vernon’s research team tests new insecticides every year to see how well they control wireworms.

Highlights from other wireworm studies

This attract-and-kill work was funded by various agencies over the years, and the research was recently completed as part of a major project on wireworm control strategies. That project is funded under Growing Forward 2 with the Canadian Horticultural Council, and runs from April 2013 to March 2018.

Vernon is the lead investigator on this national project. The collaborating researchers include his AAFC colleagues Christine Noronha, Todd Kabaluk and Ian Scott. The project’s six components are already making substantial progress.

One component, which is taking place in British Columbia and Prince Edward Island, is evaluating new insecticides, including products that are not yet registered, to see how well they control wireworms in potatoes. This component (and several of the other components in the project) are looking particularly at effects on the three introduced European wireworm species, which are causing significant problems in Prince Edward Island and British Columbia. Along with validating the effectiveness of Capture, the researchers have also identified other very promising products that could be candidates for registration.

Another component involves studies in British Columbia, Alberta and Prince Edward Island to assess the efficacy of various new insecticidal seed treatment products to control wireworms in cereal crops grown in rotation with potatoes. The researchers have found several proprietary products that look very promising. They are also testing sprays for killing click beetles – the adult stage of wireworms.

The third component is assessing several ways to use brown mustard for controlling wireworms in Prince Edward Island trials. This research has found that using mustard seed meal as a soil amendment is not practical for field-scale use. However, planting mustard

between rows of potatoes shows promise. To improve control strategies, this component also includes a study to learn more about the biology of Agriotes sputator, the invasive European species that is wreaking havoc on Prince Edward Island.

In the fourth component, the researchers are developing a biological control method to attract and kill click beetles. They have invented pheromone granules that can be used to attract beetles to an application of Metarhizium spores. This fungus is highly lethal to click beetles, and the trials have achieved up to 95 per cent mortality. The researchers are working on various aspects to develop this method into a cost-effective, practical option for commercial use.

The pheromone granules themselves might also have potential as a way to disrupt click beetle mating.

The fifth component involves development of a trap for monitoring wireworms, which uses carbon dioxide to attract the pests, and development of a method for monitoring carbon dioxide production. The researchers are testing different ways to improve the trap, and they are monitoring wireworms to predict feeding damage. They have also made an apparatus for measuring carbon dioxide production.

The project’s sixth component is the continuation of the national wireworm survey, which started in 2004. Wireworm species information is important because different species can have different responses to control measures. Canada has over 20 wireworm pest species. The species vary from region to region, and multiple species may occur in a single field. AAFC’s Wim van Herk is identifying specimens collected from farm fields across the country and mapping species distribution. Robert Hanner’s lab at the University of Guelph is sequencing the DNA of the specimens to enhance identification.

One of the components in Vernon’s major wireworm project is assessing the efficacy of new seed treatment products to control wireworms in cereals grown in rotation with potatoes.

Somebody should speak up.

Somebody should set the record straight. Somebody should do something

Well I’m somebody. You’re somebody.

Everyone in ag is somebody

So be somebody who does something

Somebody who speaks from a place of experience, with passion and conviction

Somebody who proudly takes part in food conversations big or small, so our voice is heard.

Somebody who tells our story, before someone else does.

Be somebody who does something. Be an agvocate.

AgMoreThanEver.ca

Somebody who builds consumer trust so our industry can meet the demands of a growing, and very hungry, world.

Somebody who shapes people’s relationship with agriculture

It can be done

But it’s a big job that takes co-operation, patience and respect for every voice in the conversation We need to build lines of communication, not draw lines in the sand.

Be somebody who helps everybody see Canadian agriculture as the vital, modern industry it is. Somebody who helps everybody see people in ag for what they are – neighbours, friends, and family who share the same concern everyone does: providing safe, healthy food to the people we love

Our point of view is important

Our story is important

And people want to hear what we have to say

So be somebody who takes, and makes, every opportunity to share it.

I’m somebody

You’re somebody

Together, we can tell everybody

RESEARCHERS LOOK TO SOIL FOR SCAB SOLUTIONS

Controlling common scab is a challenge, but work continues to unravel the puzzle.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

For potato growers around the world, common scab is a constant vexation. Causing millions of dollars in losses each year, common scab is difficult to control. Recent research, however, has identified options for suppressing the disease, if not getting rid of it all together. Some of the research centres on what soil properties make scab more conducive, while other studies look at natural products that can slow the spread.

“Scab is a troublesome disease,” admits Robert Coffin, a potato agrologist in Prince Edward Island. “There are different genetic strains of scab as well; there are at least five species, so it’s a constant problem. For example, common scab and powdery scab are two different organisms, but both diseases can cause losses in sales because scab infested tubers cannot be sold for table, processing or seed.”

While large strides have been made to control scab, such as using natural bacterial products, seed treatments, soil fumigants, and attempts to find genetic resistance, the disease continues to confound researchers and growers alike. Management options are limited but several help, such as planting varieties with “reasonable

resistance” or fumigating the soil, which has proven successful, although is it not permitted for use everywhere.

Some diseases can’t survive in the soil without a host, according to Claudia Goyer, a research scientist with the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Fredericton Research and Development Centre. But Goyer says scab can live successfully in the soil without potatoes being present, making it a problem when potatoes are planted.

“The scab bacteria grows on organic matter, like plant residues,” Goyer explains. “What makes it difficult is there are areas of fields that are infested while others are healthy and we do not know why. We now believe there is something different between scab-infested or healthy areas, like soil properties or microbial communities, that could be conducive or suppressive to scab.”

To test this theory, Goyer and her colleagues examined either healthy or scab-infested areas of nine potato fields in Prince

ABOVE: Claudia Goyer is researching the link between soil microbial communities and common scab.

Edward Island, New Brunswick and Quebec. The same variety of potato – Red Pontiac – was grown in each field and the team gathered soil samples three times during the year. Several soil properties (including pH, organic carbon, micronutrients and soil texture) were measured to attempt to determine the difference between the soils that contained scab and those that didn’t.

“We are trying to learn if it is something physical, chemical or biological, such as soil microbial communities in the soil, that promotes scab,” Goyer explains. “Some microbial communities suppress scab.” Not surprisingly, she also discovered that the greater the presence of the scab bacteria, the greater the disease pressure. “We are still analyzing our data, but we are seeing a correlation between scab and pH levels, with more scab in neutral pH soil. We are also seeing that soil carbon to nitrogen ratio, and nutrients including potassium, magnesium and calcium, were correlated with scab severity, but we aren’t sure why yet.”

Advancements in soil science are making it possible for the researchers to analyze soils more effectively and they are also able to assess new control options more efficiently. Coffin conducted research on Microflora Pro, a natural product that contains two species of Bacillus bacteria. He says the product worked really well in 2015, but the results were inconsistent in 2016.

“Bacterial cultures don’t always stay stable in storage or in soils,” Coffin explains. Therefore, understanding scab and how it infects soil, and continuing work to breed resistant potato varieties, would offer better disease management options.

Goyer’s work on analyzing soil and understanding why certain fields are infested with scab may also help the developers of microbial products create formulations that will work best. The advent of more sophisticated soil science research is paving the way for a better understanding of what bacteria will work best in soil.

“We can truly study soil communities so much more than we could years ago using next-generation sequencing,” Goyer says.

“We can see how diverse the soil bacteria and fungal communities that are present in soil are now because of the depth of sequencing. We can capture most of the species present with this approach.” This type of work will help explain the difference in the diversity of soil microbial communities between healthy and scab-infested areas in potato fields.

“Once we understand better what a healthy soil microbial community is,” Goyer continues, “we can see if we can change soil microbial communities so they suppress scab using agricultural practices, inputs like manure and compost, or use of natural bacterial products that suppress scab.

“In the future, we will be able to harness the power of the soil,” Goyer says. “We may be able to manipulate bacteria communities to improve all crops and we could use them to suppress disease.”

Both Goyer and Coffin approve of the idea of using one bacteria to control another. In theory, the best solution would be to combine several bacteria into one product to help with stability, reduce the potential of resistance developing and, possibly, offer balance in the soil. But with so many variables, it takes a great deal of research to get it right.

Goyer says one possibility is that a certain bacteria could be targeted to where it is needed most, similar to the way precision fertilizer application works. Higher amounts of scab-fighting bacteria could be targeted to where soil tests show a high concentration of the disease, and less could be added where scab pressure is low, creating an overall balance across the field.

“Progress is being made,” Coffin says. “With 30,000 to 40,000 genes in a potato plant, it’s like a giant Rubik’s cube when trying to breed a potato with all the desired traits.”

Of course, scab resistance is only one of the desirable traits, which makes finding a solution in the soil another option for controlling scab – and one that Goyer believes shows great promise going forward.

Great advancements have been made to control scab in potatoes, but the disease still confounds growers and scientists.

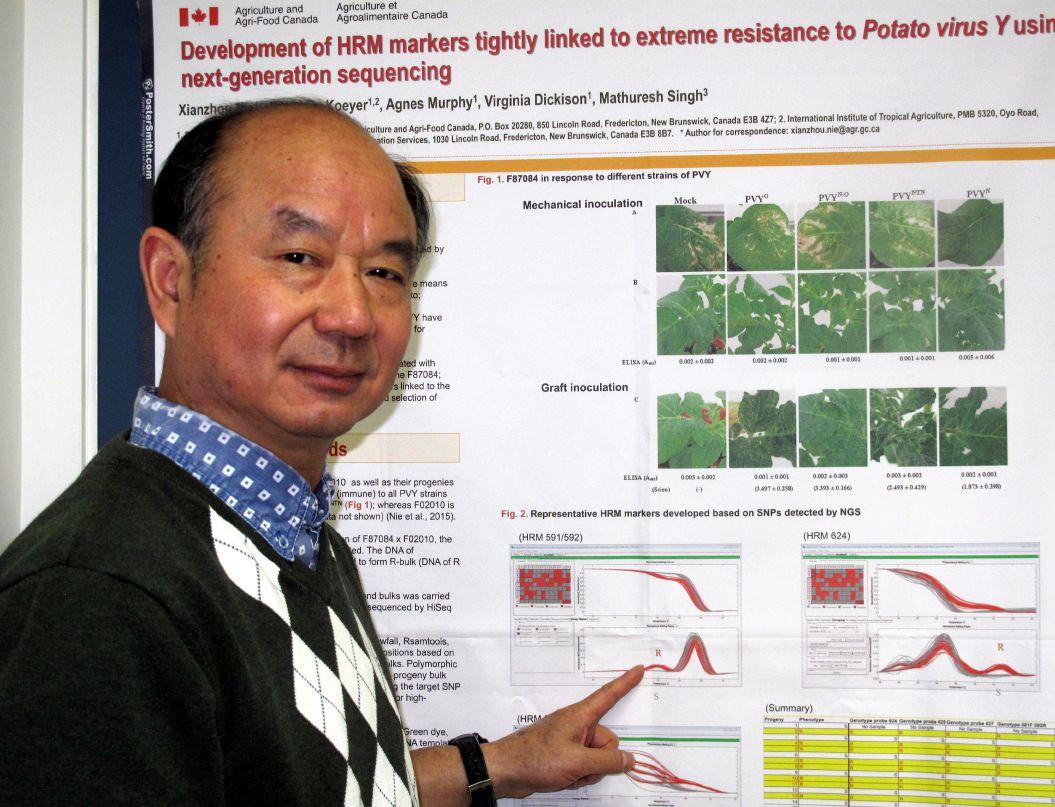

FASTER IDENTIFICATION OF PVY RESISTANCE

A new tool will help breeders isolate resistant genes.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Avirologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), in collaboration with breeders, has developed a way to speed up marker-assisted selection in the effort to identify potato virus Y (PVY) resistant material. The method – known as high-resolution melting markers, or HRM markers – has been used in other breeding programs, but Xianzhou Nie, a research scientist at the Fredericton Research and Development Centre, has perfected it so it can be used to select genetic material that is extremely resistant to PVY infections.

As most growers know, PVY infection can devastate a crop, making the choice of seed important. Severe PVY pressure can cause as much as a 90 per cent yield reduction. Choosing seed that is PVY free, therefore, is the first step towards minimizing losses. However, aphids can also transfer the disease, which adds to the workload and cost of production when growers have to spray mineral oil to ensure the spread of aphid-transmitted PVY is minimized. The best solution from economic and environmental perspectives would be to have potato varieties that are resistant to PVY, which would also eliminate the spread of the disease. Nie

hopes this research and development of a faster method to identify PVY-resistant and susceptible parent material and progeny will vastly improve and fast-track potato breeding.

“Using HRM markers, we are identifying efficiently and accurately, markers associated with genes controlling PVY resistance in potatoes,” he explains. “If a potato inherits the resistance gene, it will not develop the disease. This will be very useful for breeders making selections in breeding programs.”

Conventional breeding programs can screen thousands of crosses; it isn’t until the most promising are faced with PVY pressure that breeders know for sure if they have a potential diseaseresistant variety. Traditional screening for PVY resistance is carried out mainly in the greenhouse by inoculating each and every offspring/progeny plant with the virus and then waiting for symptoms to develop and laboratory detection of PVY to be completed.

ABOVE: Xianzhou Nie uses high-resolution melting markers to select genetic material that is extremely resistant to PVY infections.

By using the HRM marker technique (a procedure carried out in a laboratory as well), breeders will not only be able to identify and select parental material that is PVY-resistant or has “extreme resistance” prior to making crosses, but they will also be able to screen for progeny/offspring inheriting the resistance efficiently in the laboratory setting.

Nie estimates that if 200 plants are bred using traditional selecting methods involving PVY inoculation in the greenhouse, it can take two to three months to determine which progeny, if any, are resistant to PVY.

“Using the HRM marker method, we can screen for PVYresistant plants in two to three days,” he says.

By determining the value of using HRM markers in PVY screening, Nie says that in the future the method could be used to identify other diseases, or to isolate desirable traits. He says using HRM marker technology allows a researcher to run 96 samples in three to four minutes after amplification of the DNA pieces containing the markers. There’s no question the potential for breeding programs in the future is enormous.

“In our breeding program at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, we anticipate the method being implemented for screening for

disease resistance to speed up the selection process,” Nie says. Because the method was perfected at a public institution, it is not protected by copyright, which makes it accessible to any breeding program in the world. “We have provided the technology and now anyone can choose to use it.”

Early in 2016, this new form of PVY resistance identification was tested on some of the latest clones bred at AAFC. The presence of the HRM markers that indicate PVY resistance was detected, which signals the potential varieties will be PVY-resistant. The breeders are now looking for germplasm that would have extreme resistance to PVY because those markers are present. Nie envisions a day when PVY-resistant potato varieties will be common, giving growers one less disease to worry about.

The Herbicide Resistance Summit aims to facilitate a more unified understanding of herbicide resistance issues across Canada and around the world.

Leading scientists will share the latest information on key issues faced by farmers, agronomists and crop protection researchers.

Delegates will walk away with a clear understanding of specific actions they can take to help minimize the devastating impact of herbicide resistance in their fields.

C NFIDENCE. O

The potato business can be unpredictable, but your coverage doesn’t have to be. Titan ® Emesto ® seed-piece treatment is a red formulation that’s easy to apply and easy to see. It protects against the broadest spectrum of insects – including Colorado potato beetle – plus all major seed-borne diseases, including rhizoctonia, silver scurf and fusarium, even current resistant strains. But don’t just take our word for it. Canadian potato growers have con dence in Titan Emesto. When your coverage is