TOP CROP

MANAGER

5 | Fungicide-resistant pink rot research shows ridomil resistance is increasing in Canada, but alternatives are available.

By Carolyn King

Treena Hein

Pests and diseases Managing potato Virus Y By

Julienne Isaacs

8 | Ahead of the curve on zebra chip getting ready in case this serious disease arrives in Canada.

By Carolyn King

Carolyn King

Treena Hein

22 | Brassicas in potato rotations research shows canola and its cousins can reduce certain diseases and improve potato yields.

By Carolyn King

By Brandi Cowen, Editor

Andrew and Heidi Lawless, potato producers from Kinkora, P.E.I., were named Canada’s Outstanding Young Farmers for 2014. www.potatoesincanada.com

readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of

Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and

labels for complete instructions. PotAto fA rm E rs n A m E d 2014 o utstA nding Young fA rm

Brandi Cowen | ediTor

A m ATTER Of TRu ST

Prince edward Island’s potato industry has weathered a rocky few months. Last fall, consumers discovered several sewing needles hidden inside potatoes originating from Linkletter Farms in Summerside. Linkletter responded by ordering a voluntary recall of affected products, and the prince edward Island potato Board offered up a $50,000 reward for information, leading to the arrest of anyone involved in the tampering. Despite the reward eventually growing to a whopping $100,000, the identity of the culprit remained a mystery. That mystery deepened in late December, when additional sewing needles were discovered at the Cavendish Farms plant in new annan. although no recall was required in this instance, a total of 100,000 pounds of processed French fries and raw potatoes, originating from a second farm, were destroyed. an rCMp investigation is underway, but as of press time, the reward remains unclaimed.

Media reports calling the safety of our food supply into question are never good news for those whose livelihoods are tied to the supply chain. For p e.I’s potato industry, however, there has been one bright spot throughout these past few months: widespread support from many corners. The p e.I. potato Board rallied behind Linkletter Farms early on, offering up the initial reward for information about the tampering. The provincial government and other industry groups, including a grower-owned vegetable supplier in Manitoba, were quick to pitch in funds that ultimately doubled the value of the reward. Last month, amid new reports of further tampering, the Island’s Western gulf Fishermen’s association (WgFa) purchased 200 10-pound bags of potatoes directly from Linkletter Farms and an additional 200 bags from a local shipper for distribution to members attending the association’s annual meeting. WgFa leaders also encouraged other groups on the Island to make their own shows of support for the province’s potato industry.

Farmers on p e.I. and across the country can take some comfort from the fact that the province’s potato board reports the discovery of the sewing needles has not had an impact on business to date. perhaps consumers are reassured by the knowledge that the Conference Board of Canada’s Centre for Food in Canada and the University of guelph’s Food Institute ranked Canada first in their 2014 World ranking of Food Safety performance. The ranking, which saw Canada tie with Ireland as first among 17 countries in the organization for economic Co-operation and Development, evaluated countries on 10 indicators across three areas of food safety risk governance: risk assessment, risk management and risk communication.

From the outset, the p e.I. potato industry has been frank, honest and open with consumers in its approach to addressing the recent incidents of food tampering. Measures are in place to identify safety issues prior to products reaching consumers and, as the discovery at the Cavendish Farms plant demonstrated, those systems are effective. When a safety risk is identified, swift action is taken to remedy the situation and minimize the risk to consumers, as Linkletter Farms proved when it issued the voluntary recall of its products. The industry’s regular updates to the media are proof of a commitment to providing consumers with the information they need to make informed decisions about the food they serve their loved ones. The public has rewarded the industry’s approach with continued trust in the safety of the Island’s potatoes, and faith in the industry to act in the best interests of consumers. We may never know who tampered with p.e.I.’s most well-known crop, nor their reasons for doing so, but farmers across the province and across the country can rest a little easier knowing it will take more than a few sewing needles to curb consumer appetite for their product.

AGREEMENT #40065710 rETUrN UNDELIVErABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIrCULATION e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCrIPTION rATES

Top Crop Manager West - 8 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, August, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 2 issuesSpring and Summer 1 Year - $16 CDN plus tax All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2015 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. www.topcropmanager.com

f u NGICIDE - RESISTANT PIN k ROT

Research shows Ridomil resistance is increasing in Canada, but alternatives are available.

by Carolyn King

Pink rot resistance to ridomil is becoming more common in north america. So, Canadian researchers are determining how far the resistance has spread in this country, and they’re evaluating alternative fungicides to add more tools to the pink rot management toolbox. pink rot is an economically important potato disease usually detected late in the season or in storage. It is caused by a soilborne, fungus-like pathogen called Phytophthora erythroseptica. Wet conditions favour the disease.

The pathogen can infect all the underground parts of the potato plant, causing infected tissues to turn brown or black. Tubers are most commonly infected via the stolons, but in very wet autumns the pathogen can also enter through the eyes or lenticels. aboveground symptoms, such as wilting, stunting and defoliation, tend to appear late in the season. The infection can spread to other tubers during potato harvesting, handling and storage.

When an infected tuber is cut open, the infected area gradually turns pink, then brown and finally black, over the course of about an hour of exposure to air.

resistance is a growing concern

“ ridomil g old’s active ingredient is metalaxyl-m. It is commonly used as an in-furrow treatment, but it’s also used as a foliar because it has some systemic activity. It has been a standard go-to product for pink rot,” says Dr. rick peters, a vegetable

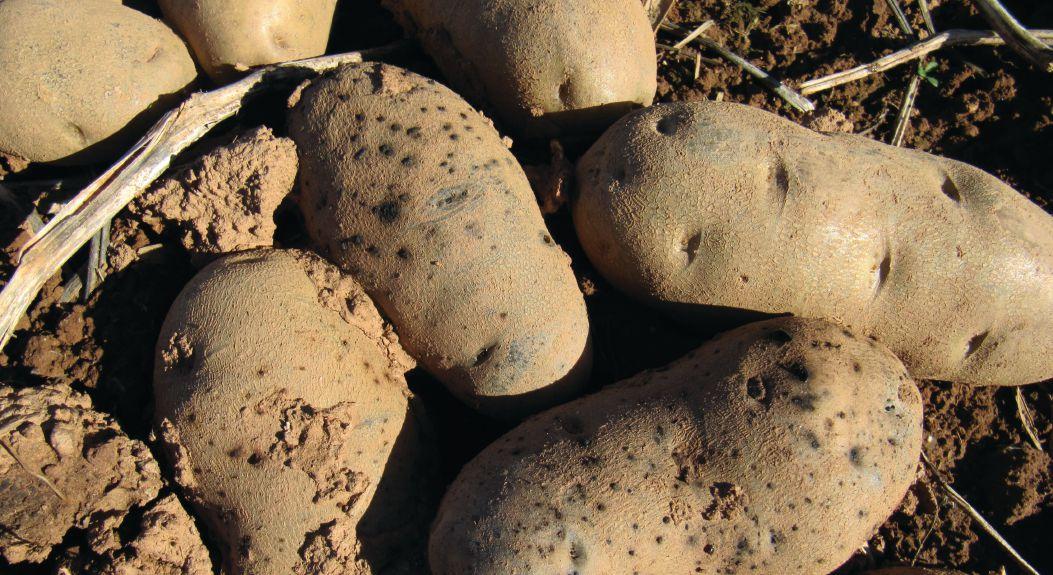

toP: a preliminary survey in 2012 found some fungicide-resistant isolates of the pink rot pathogen in P.e i., so the researchers knew resistance was spreading.

Middle: tubers are most commonly infected via the stolons, but in very wet autumns the pathogen can also enter through the eyes or lenticels.

pathologist with a griculture and a gri-Food Canada ( aa FC) in Charlottetown. over the years, resistance to metalaxyl has developed in many

species of Phytophthora . For instance, by the mid-1990s metalaxyl-resistant strains of Phytophthora infestans , the late blight pathogen, had become so common in the U.S. and Canada that metalaxyl was no longer an effective control option for that disease.

For the pink rot pathogen, metalaxylresistant populations began to be found in north america almost two decades ago, initially in Maine, new York, new Brunswick, Idaho and Minnesota, and then spreading to other american states.

peters has been on the lookout for the further spread of metalaxyl-resistant pink rot in Canadian potato-growing areas.

His most recent national survey was from 2005 to 2007. “at that time we found some evidence of resistance to ridomil creeping up in pink rot populations in new Brunswick, but we didn’t find any evidence outside of that province in our testing,” he says.

In 2012, peters and his research team carried out a preliminary survey in p.e.I. because Island growers were having some issues with pink rot that year. The researchers found metalaxyl-resistant isolates of the pathogen in some fields.

Knowing the problem had spread to p.e.I., peters wanted to determine the current national status of metalaxyl resistance in the pathogen. So, with funding from Syngenta Canada, the prince edward Island potato Board and the potato growers of alberta, he initiated a two-year project, starting in the fall of 2013. The project has two components: a national survey, and field trials of alternative control measures.

“This project will help to give growers information to use fungicide products efficiently,” explains Mary Kay Sonier, seed co-ordinator with the p e.I. potato Board. “For example, if the researchers discover that a high percentage of our isolates here are resistant to ridomil, then there would not be much point in people continuing to use it. It would either further select for resistance – so increase our resistant population – or it would be a waste of product and a waste of money for the growers. If, on the other hand, the number of resistant isolates is low, it would indicate that the product is still an effective control measure.”

She adds, “This project will also help increase grower awareness of the importance of rotating control options to avoid

the build-up of resistance in all pathogens, not just pink rot.”

Cross-Canada survey

The national survey is being conducted in partnership with many agencies. “over the years, we’ve developed quite a good collaborative base across the country through many different studies of other pathogens including Fusarium, Helminthosporium (silver scurf) and so on,” peters says. “So we have good collaborations in each province with provincial staff, industry reps from the different chemical companies, grower groups and so forth who will sample for us and then courier the samples to us in Charlottetown for our analysis.”

If growers find pink rot-infected tubers at harvest time or during storage, they send samples to their provincial co-ordinator, who sends the samples to peters’ lab. The survey’s first season was in the fall and winter of 2013-14; it will be completed in the fall and winter of 2014-15.

For the 2013 crop, the researchers tested a total of 195 isolates from 47 fields and storages. They found resistant isolates in samples from new Brunswick, p e.I., nova Scotia, ontario and Manitoba. no resistant isolates were found west of Manitoba.

peters cautions that these are preliminary results. “a lot of this also depends on the number of samples, and every year is different that way. If you get a wetter season, it’s more conducive to pink rot, and a drier season is less so. Depending on how many samples we get this year from the western part of the country, we might have a better idea of the resistance spectrum out there.”

peters thinks the resistance is likely spreading in two main ways: through transport of infested soil and infected seed; and through development of resistance within a production area due to heavy use of metalaxyl.

He explains, “There are always some resistant strains at a very low level in any pathogen population. So when a fungicide is used very heavily, those strains start to become more prominent in the population.”

evaluating alternatives

“Considering what we’re seeing, especially in states like Maine, north Dakota, Idaho and so on where the ridomil-resistant populations of the pink rot pathogen are quite pronounced, there’s definitely a need for alternative products. So we have been looking at that as well,” peters explains. In the current project, peters and his

Pink rot is caused by a soil-borne, fungus-like pathogen called Phytophthora erythroseptica. it is usually detected late in the season or in storage.

research team are conducting field trials in 2014 and 2015 to evaluate in-furrow and foliar fungicide applications. They are comparing phosphite fungicides and several other products that are registered or being considered for registration for pink rot, as well as some experimental products. The trials are being conducted at aaFC’s Harrington research Farm in p e.I. The researchers are collecting data on factors like emergence, disease levels and yields in the potato crop.

peters and his colleagues conducted several previous studies of phosphite fungicides – not to be confused with phosphate fertilizers. phosphite fungicides have a lower environmental risk than some other fungicides. They are applied as a preventative treatment. They can directly inhibit pathogen growth and reproduction. as well, they can stimulate the plant’s natural defences to fight various pathogens, which can improve plant health and crop yield.

The researchers assessed the effectiveness of phosphites on various diseases. For pink rot and late blight, the studies showed foliar applications of phosphites worked as well as, or better than, metalaxyl-m applications. In addition, the tubers that received phosphites in the field were less susceptible to disease after harvest.

peters notes that two phosphite products, Confine extra and phostrol, are now registered in Canada for in-crop treatment of pink rot.

The current project involves field applications of the fungicides because managing pink rot in the field is critical. “postharvest fungicides for pink rot and late blight are mainly phosphite-based products like phostrol, Confine and rampart, which work really well at killing pathogen spores on the surface of tubers. But the problem is that a lot of our infections happen in the field. and if tubers are infected in the field, the post-harvest treatment [can’t cure them],” peters explains.

He adds, “We often consider pink rot as a late-season or harvest disease, but infection of the plant’s underground tissues can occur fairly early in summer. Then those infections progress through the stolons into the tubers as you get closer to harvest-time. So, early management can be really important.”

What you can do now

“[In the survey], we are seeing more

tubers are most commonly infected via the stolons, but in very wet autumns the pathogen can also enter through the eyes or lenticels.

metalaxyl-resistant pink rot in the eastern provinces. That is definitely a warning bell not to rely on one fungicide product,” peters emphasizes.

So, a key practice for growers is to rotate fungicide products to slow the development of resistance. peters notes that several products are available for a fungicide rotation to manage pink rot.

“phosphites are excellent products for pink rot,” he says. “They are very systemic. and particularly when applied in the field season, which we often do for a late blight program, they give really good tuber rot control for both late blight and pink rot. In some of those U.S. states where ridomil resistance has become really common, phosphites have become a solid alternative to ridomil.” (note that phosphite fungicides should not be applied to seed potatoes as a foliar or post-harvest treatment until further research has been done.)

another fungicide option is Bayer CropScience Canada’s Serenade. “This is a biological control product, a Bacillus bacterium, which now has pink rot on the label as a soil-applied product at planting,” peters explains. as well, Valent Canada and nufarm agriculture Inc. are planning to submit an application this fall to Canada’s pest Management regulatory agency to add pink rot to the label of presidio.

peters also reminds growers to make use of the other tools in their disease management toolbox.

“Using good-quality seed to start things off is always very important, so you’re dealing with a seed piece that is healthy and able to establish a vigorous plant.

“Since moisture is a large factor in how pink rot establishes itself, areas that can irrigate might be able to control moisture levels [to help reduce the disease].

“and eliminating wounding at harvest can be important because any time you have a wound on a tuber it’s more conducive to storage infections,” he says. o ther disease management practices include removing diseased potatoes before storage, and maintaining proper moisture, temperature and air circulation during storage.

Looking ahead, peters is working on another angle to help growers manage pink rot. “This fungus produces an oospore that lasts in the soil for many years and most of our soils would have oospores in them,” he says. “We are working on molecular tests to try to quantify how much inoculum is in soils. So we might be able to have a better predictor of which fields are particularly prone to pink rot because they have so much inoculum in the soil.”

Ah EAD Of T h E C u Rv E ON z E b RA C h IP

Getting ready in case this serious disease arrives in Canada.

by Carolyn King

Zebra chip is a devastating potato disease costing millions of dollars to the potato industry in affected areas of the U.S. and other countries. So far, the disease hasn’t been found in Canada, but it is moving toward our border. now a major multi-agency project is taking a proactive approach in case zebra chip arrives here.

The project involves a nation-wide monitoring network for zebra chip and the potato psyllid – the tiny insect that transmits the disease – and related research and technology transfer activities. The overall goal is to help the Canadian potato industry be better prepared to deal with the disease if it comes to Canada.

The impetus for the project came from the potato growers of alberta (pga). “about four years ago, I was at a potato association of america conference and the hot topic was the potato psyllid and zebra chip. I talked to some of the presenters and scientists about what was happening with this disease and the potential for it to migrate north. So I became interested in the disease,” pga executive director Terence Hochstein explains.

Then in 2011, zebra chip was found in Washington, oregon and Idaho. Hochstein says, “In the pacific northwest, they didn’t realize they’d had it until the end of the season and the damage was already done. We discussed what it did to their crop that year, the economic cost to growers and the effects on the whole industry, and we decided to start looking at the problem rather than waiting until we have it here.”

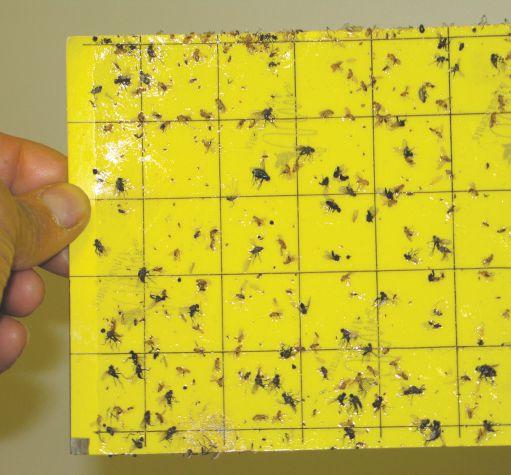

toP: one of the features used to distinguish the potato psyllid from other psyllid species is the broad white stripe on the adult potato psyllid’s abdomen.

Middle: so far, over 1800 sticky cards have been returned to Johnson, and no potato psyllids have been found.

Dr. Dan Johnson, an entomologist specializing in large-scale insect forecasting, ecology and biogeographic analysis at the University of Lethbridge, is the project’s principal investigator and national coordinator. He notes, “potato psyllid and zebra chip are poised to enter Canada, but they are not here yet. It may be just a matter of time before the disease moves into Canada. We think it will probably arrive first in British Columbia, alberta and Manitoba, and then perhaps eastern Canada.”

about the disease and its vector

Zebra chip is caused by the pathogen Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum. Infected potato plants show above-ground symptoms such as stunting, zigzag stems, and misshapen and discoloured leaves. Tuber symptoms include enlarged lenticels, collapsed stolons and brown “zebra” streaks and flecks that are especially noticeable in fried potatoes. The disease kills potato plants, severely reduces yields and makes the tubers unsalable because of the brown discoloration.

“This disease is so new that there are a lot of unanswered questions,” notes Dr. Larry Kawchuk, a plant pathologist and molecular biologist at agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC). Kawchuk is one of the main collaborators on the project.

Zebra chip was first discovered in Mexico in 1994 and in Texas in 2000. Since then it has spread through much of the western half of the U.S., into several Central american countries and new Zealand.

only potato psyllids (Bactericera cockerelli) transmit the zebra chip pathogen. They become infected by feeding on plants that have the disease, and then they spread the pathogen to other susceptible plants

by feeding on them. Infected adults can sometimes transmit the pathogen to their offspring.

potato psyllids go through three life stages: egg, nymphs and adult. The adults are about 2 mm in length, with long, clear wings. They prefer to lay their yellowish, football-shaped eggs on solanaceous plants, such as potatoes, tomatoes and peppers and on weeds such as hairy nightshade. The nymphs are flat with a spiny fringe.

In the U.S., only a small percentage of potato psyllids carry the zebra chip pathogen. Infected psyllids are referred to as “hot.” Some U.S. research indicates hot psyllids can transmit the pathogen to a plant in less than an hour or two of feeding. The adults hop around, so hot psyllids can infect multiple plants.

potato psyllids are able to survive temperatures below freezing and seem to be overwintering in the pacific northwest. over the years, they have occasionally come into Canada. For instance, in 2012 two purported potato psyllid immatures were found near Carberry, Man. Both were free of the pathogen.

at present, the main way to control the spread of zebra chip is by controlling the potato psyllids. Some potato cultivars are more tolerant of the disease than others, and U.S. potato breeders are working to develop varieties with improved zebra chip resistance.

Monitoring underway

The Canadian monitoring network is a collaborative effort. The three research leads are: Johnson; Kawchuk; and Scott Meers, insect management specialist with alberta agriculture and rural Development, with responsibility for insect pest monitoring in the province.

along with these three researchers and

the pga, the network includes people from potato grower associations in other provinces, the Canadian potato Council, the Canadian Horticultural Council, agronomists, federal and provincial specialists, university researchers, potato processors and others in the potato value chain.

The project, which started in 2013 with field sampling in advance of the main project, is funded through the Canadian Horticultural Council in the Canadian agriScience Cluster for Horticulture supported in part by aaFC growing Forward 2 funding. The project’s industry funding component is provided by contributions from the pga, the Stuart Cairns Memorial Chipping research Fund and the University of Lethbridge.

Yellow sticky cards are used to monitor adult psyllids. These cards have very light layers of sticky surface and do not harm birds or mammals. Hochstein outlines how the psyllid monitoring works in alberta: “We work with the local agronomists to ensure good coverage across the growing area. While they are scouting the fields, the agronomists put the cards in, usually just inside the perimeter of a field,” he says. “The cards are left in place for seven days of clear weather. Then the agronomists collect them and drop them off at our office.” as well, Johnson places cards at additional locations, such as roadside vegetation in alberta and B.C., to improve the chances of catching invading potato psyllids. He has also established sentinel plots for more detailed sampling, including sweep net sampling for adults, and leaf sampling for eggs, nymphs and adults.

Co-operation from growers to establish sampling sites at field edges will be an important part of the continuing program. project staff examines every one of the

these and other psyllid species look similar to the potato psyllid, but they do not transmit zebra chip, so Johnson is working on an iPhone app for psyllid identification.

collected cards under a microscope to identify and count all the insects, including things like aphids, beetles, flies, wasps and other psyllid species. over 1000 cards were examined in 2013. Cards examined in 2014 include: over 500 from alberta, 59 from Manitoba, 500 from new Brunswick, 11 from p e.I. and 45 from Quebec.

“So far we have found many types of psyllids, but no potato psyllids,” Johnson says.

The project’s disease monitoring involves testing potato psyllids caught by the monitoring network and any plants suspected of having zebra chip. Kawchuk has been working on refining laboratory methods for testing for the disease based on techniques developed by some of his U.S. colleagues. His lab extracts Dna from each sample and analyzes it for the zebra chip pathogen, using a very precise technique.

“We are encouraging people to send in samples of plants with foliage symptoms that might possibly indicate zebra chip,” Kawchuk says. “and if processors see any examples of tubers with the distinctive zebra chip speckling, we’re asking them to bring in the tubers.”

During 2013 and 2014, Kawchuk’s lab examined over 150 foliage samples. He says, “all of our testing was negative for zebra chip.”

so far, so good

“We’ve done enough sampling to know zebra chip is not here yet,” Johnson says. “We have a little breathing room to test and refine our sampling and analysis methods, and get ready if and when it does hit. So we are ahead of the curve on this research.” The monitoring network will expand this year, with more fields and more provinces participating.

Johnson is also interested in sampling additional sites beyond those monitored in the provincial monitoring efforts, and he’ll provide free yellow cards to people who want to put the cards out for a week and then send them to him for checking. greenhouses, potted plant suppliers, gardens and tomato crops are important additional sampling sites.

as well, he plans to continue fieldwork to try to determine the current distribution and prevalence of solanaceous weed species. He hopes to start monitoring some of these weeds for the potato psyllid, and to determine whether the psyllid, and/or the pathogen, is able to overwinter in any of these weeds.

If and when potato psyllids arrive in Canada, the researchers will work on refining monitoring techniques to suit Canadian conditions. They will also assess how closely the total potato psyllid numbers and the number of hot psyllids are related to the incidence of zebra chip. and they will evaluate to what extent they should be monitoring fields for symptomatic plant tissues.

In addition, Johnson will be investigating ways to predict potato psyllid infestations, for example, by using factors like air mass movements, temperatures, sources of populations and so on.

and if the psyllid arrives, Meers and Johnson will start research on control methods. possible directions for their research include integrated control practices, minor use registrations for insecticides and testing psyllids to check for insecticide resistance, since some U.S. potato psyllids have developed resistance to certain insecticides. Johnson notes, “Some research in the U.S. indicates that it may even be possible to develop a biological control agent for suppression of the potato psyllid, perhaps using the new insect biocontrol agents we have recently developed in Canada.”

If the zebra chip pathogen is found in Canada, Kawchuk will study it to determine whether the Canadian biotype is different from those found in other regions.

Information aids for growers and agronomists are also being developed. For example, Johnson says the team is working on an iphone app for psyllid identification. “We have about 30 species of psyllids, so I’ve started preparing a guide for psyllid recognition and sampling, with photographs. You need to use a hand lens, but you can recognize the potato psyllid quite quickly once you know the different psyllid species.”

at present, the key for Canadian potato growers is to watch for the insect and disease symptoms.

“It would be great if zebra chip doesn’t arrive here,” Johnson says. “Certain attributes of our landscape, vegetation and climate might help to slow potato psyllid establishment. For example, perennial solanaceous weeds can allow the potato psyllid to overwinter and we have almost no perennial solanaceous weeds,” he says. “So we might end up in the situation where occasionally the psyllid will fly in and cause trouble but not overwinter. The only way to find out will be to stay on top of sampling and develop computer models of where and how they could survive here.”

Hochstein adds, “It’s a matter of watching and monitoring. I hope we never see zebra chip. But if we do, we are going to try to be prepared.”

Yellow sticky cards are being used in a nation-wide program to monitor for potato psyllids – the insects that transmit zebra chip disease.

Breeding NAT u RA l RESISTANCE

Harnessing the genes in wild varieties to better control late blight.

by Treena Hein

Potato breeders have long turned to exotic or wild varieties for their rich and varied genetic material. Wild species contain a great diversity of traits, which relate to a myriad of aspects of potato cultivation and end-product desirability. The ability to resist disease is a trait of particular interest.

In a new project, Dr. Benoit Bizimungu is now hard at work in harnessing the natural resistance found in wild potato species to help better control late blight. Dr. Qin Chen, who helped develop somatic hybrids, and technicians ron gregus, evelyn Lyon and Susan Smienk have assisted Bizimungu during this breeding project at the agriculture and agri-Food Canada research centre in Fredericton.

Late blight (P. infestans) is arguably the most devastating and dangerous potato disease, and because most – if not all – commercial potato cultivars are susceptible to the fungus, farmers must apply fungicide to their fields several times each growing season. over recent years, more virulent strains of late blight have emerged, strains that are harder to control with fungicides, and this means breeding efforts to create varieties with better resistance are more important than ever. planting varieties with boosted resistance also means that growers may be able to reduce the amount of fungicide applied to fields in the future.

Most breeding programs around the world in this vein have focused on using a wild potato relative called Solanum demissum as their main late blight resistance source. Bizimungu explains at least 11 resistance genes (r1-r11) have been identified in S. demissum, and four of them (r1, r2, r3 and r10) have been introgressed into commercial cultivars, but strains of the pathogen that are able to overcome the defences related to these genes have emerged.

Breeders are therefore turning to new sources of resistance, and working to develop germplasm with polygenic resistance (resistance that is stronger, longer-lasting and more durable). In the quest to create varieties less susceptible to late blight, the more durable resistance that can be had, the better. “Durable resistance means that different resistance mechanisms are present in the plant, allowing it to fend off disease in several different ways,” Bizimungu explains.

plant defence mechanisms against late blight work in two ways. one is the presence of physical and chemical barriers on the plant surface that help prevent the fungus from penetrating the plant. The other set of plant defences come into play after successful pathogen penetration has occurred. These latter defences inside the plant include the production of hypersensitive response lesions, as well as the production of various substances that negatively affect the pathogen, such as reactive oxygen species, a glucose residue molecule named callose and various proteins. each of these

defences work in different ways. reactive oxygen species, for example, fend off late blight through their antimicrobial activity and through their important role in cross-linking cell wall proteins.

resistance from the wild

Solanum species are found growing in the wild over a large geographic area – from the southwestern United States to many parts of South america. For this project, Bizimungu is employing three sources of resistance recently found in Mexico (a region with heavy late blight disease pressure) that have the potential to offer natural protection to some strains of late blight. These three wild species are Solanum bulbocastanum, S. chacoense and S. pinnatisectum, with the last one identified in particular as having distinct genetic late blight resistance.

With the aid of molecular markers, Bizimungu and his team have crossed these strains to produce 16 new advanced potato selections. Many more selections with improved resistance are expected to come out of the breeding program in the future. The breeding process began with adding highly virulent late blight inoculum to plants in the lab. The selections that showed the best resistance were then planted and assessed in the field in the presence of natural late blight infection pressure. The best performers from those field trials are currently being hybridized into fresh market and processing selections with acceptable agronomic performance. The progeny is being assessed in various stages at two Canadian locations under different conditions: the Vauxhall research substation in alberta under irrigation production and the Benton ridge substation in new Brunswick under rain-fed cultivation.

of the three wild species, Solanum pinnatisectum presented a special challenge since crossing it with commercially cultivated potato plants (via sexual hybridization) is not possible. The team therefore had to use somatic hybridization, which involves the fusing of somatic (body) cells of parent plants. Successful somatic hybrids were subsequently backcrossed with adapted cultivars or elite breeding clones and the progeny was screened for resistance to P. infestans – and also to see if they possess the capacity for sexual crossing. resistant backcross progenies are being grown at the Vauxhall research substation in alberta and are being assessed for field performance in terms of late blight resistance and agronomic potential.

new lines from all three wild species will be field-tested over the next few years, Bizimungu explains, at which point they will either be used as parents to further develop improved cultivars or be released commercially. “Three potatoes with improved, moderate resistance to some strains of late blight in controlled tests are currently under active evaluation by industry for potential commercialization.”

Take your place in the conversation

There’s

been a lot of talk about food and farming lately – online, in the media and at the dinner table.

That’s a really good thing. It means people are concerned about their health and wellbeing, and that they’re in a position to make positive choices about what they eat. It also spells opportunity for Canada’s agriculture industry. What we do has never been so important to so many people here at home and around the world.

Unfortunately, too many of these conversations are generating false perceptions about what we produce and how we produce it. That’s often because for all the people talking about food, too few are actually part of the agriculture industry. And if we’re not telling our story, someone else will. The good news is, it’s not too late – and we’ve got lots of positive news to share.

Canadian agriculture is remarkably diverse and dynamic. Yet for all the change

the industry has seen over the years, one important constant remains: the family farm. In fact, 98 per cent of Canadian farms are family farms. That’s a key part of the conversation, because from the ground up, what we eat every day is produced by people who want the same things all families want: safe, nutritious food. Those same values also extend to how our food is produced. Canadian farms produce more than ever in ways that are more sustainable than ever. What a great legacy for future generations!

You’re an important part of the conversation. So speak up – tell the real story.

Every fact

Canadian agriculture has a lot going for it, and sharing the facts is a great way to join the conversation. Our resource section is filled with timely, interesting content – including dozens of easy-to-share fact photos. And each one tells an important story. Here are just a few:

Source: CropLife Canada

Canada’s opportunity: world food demand is set to grow 60% by 2050

The world is growing, and everyone deserves to have access to safe, high quality food. It’s a huge responsibility and an incredible opportunity for Canadian agriculture. Canadian farmers are responding by producing more food than ever, all while using fewer resources. That’s good news here at home and around the world.

Thanks to Canada’s ag and food industry, more than 2.2 million Canadians are bringing home the bacon (pardon the pun) every day. That’s like the entire population of Vancouver. The impact on Canada’s economy, and on our communities and families, is truly remarkable.

Never has Canadian agriculture offered more – and more diverse – career options than right now. There are opportunities in research, manufacturing, financial services, marketing and trade, education and training, and more. And all of these positions need to be filled by talented, energetic people. Visit the website and consider what the facts mean to you. Then join the conversation! AgMoreThanEver.ca

Source: An Overview of the Canadian Agriculture and Agri-Food System 2014 (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada)

Be an AGvocate

Resources to get you started

Joining the ag and food conversation isn’t always easy. What you say is important. So is how you say it. If you’re feeling a little unsure about what to do next, you’re definitely not alone. Fortunately, we’ve got practical expert advice to help you become an effective agvocate.

Our online webinar series brings recognized experts in communication, social media and media relations right to your screen. Topics include:

• The art and science of the ag and food conversation

• Social media 101 for agvocates

• Getting in on the tough conversations

• Working with the media as an agvocate

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca and click on Ag Conversations.

Agvocates unite!

Looking to channel your passion for ag? Adding your name to our agvocate list is a great way to get started. You’ll join a community of like-minded people and receive an email from us every month, with agvocate tips to help you speak up for the industry.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca/agvocates to join.

We a ll sha re t he sa me ta ble.

Pul l up a c hai r.

“ The natural environment is critical to farmers – we depend on soil and water for the production of food. But we also live on our farms, so it’s essential that we act as responsible stewards.”

- Doug Chorney, Manitoba

“ We take pride in knowing we would feel safe consuming any of the crops we sell. If we would not use it ourselves it does not go to market.”

- Katelyn Duncan, Saskatchewan

“ The welfare of my animals is one of my highest priorities. If I don’t give my cows a high quality of life they won’t grow up to be great cows.”

- Andrew Campbell, Ontario

Safe food; animal welfare; sustainability; people care deeply about these things when they make food choices. And all of us in the agriculture industry care deeply about them too. But sometimes the general public doesn’t see it that way. Why? Because, for the most part, we’re not telling them our story and, too often, someone outside the industry is.

The journey from farm to table is a conversation we need to make sure we’re a part of. So let’s talk about it, together.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca to discover how you can help improve and create realistic perceptions of Canadian ag.

mANAGING P OTATO vIRu S Y

Border crops an option in managing this growing threat.

by Julienne Isaacs

In the past several years, potato Virus Y (pVY) has increasingly become a concern to commercial potato producers across Canada, as the number of strains of pVY continues to increase.

pVY is vectored by aphids, which can damage potato plants on their own, but pose a greater threat through their role as carriers of the viral disease. Infection can render potatoes unmarketable.

according to Ian Macrae, an associate professor and extension entomologist at the University of Minnesota’s Department of entomology, the problem of pVY-vectoring aphids has become an epidemic, partly due to: the popularity of non-symptomatic potato varieties resulting in more inoculum to infect symptomatic potato varieties; the development of pVY strains that cause tuber diseases; and the introduction of soybean aphids as a new vector with different population dynamics than traditional aphid species.

Macrae says producers must take a multi-faceted, integrated, pest-management approach to controlling the disease, including, most importantly, limiting inoculum by planting clean seed, using resistant cultivars, and controlling the insects that vector the disease by using crop borders, crop oil sprays and insecticides shown to slow the spread of pVY, such as the anti-feedant type.

In Minnesota, research is being conducted around the use of border cropping in helping manage pVY. The project began, Macrae says, after a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, Chris DiFonzo – now an extension entomologist at the University of Michigan – noticed that aphids, the most common pVY vector, tended to settle on the edges of fields.

“Building on her research, we looked at the spatio-temporal distribution of colonizing aphids and realized they settle at the edge for a bit longer than a week, prior to moving into the fields,” Macrae says. Initial research was conducted by Matt Carroll, now an entomologist with Monsanto.

Based on Carroll’s research, the department began recommending producers treat borders with insecticides to control the first colonization events. according to Macrae, producers have found this to be an effective strategy in managing aphid populations within-field, and in seed potato fields. originally, cereal crops were suggested as good border crops, but as cereal aphids move into potato fields after grains mature, soybean replaced cereals as the suggested border crop.

“It seemed a great fit, because the traditional vectors of pVY don’t increase on soybean, and soybean is not a host for pVY,” Macrae explains. “Unfortunately, it turns out that soybean aphids, while not feeding on or colonizing potatoes, can vector pVY.” He adds their populations will grow on soybean, which means a soybean border crop can be a source of soybean aphids.

Soybean aphids have a late-summer dispersal event, which can mean millions of aphids enter fields. “If they arrive viruliferous, in those numbers they can obviously introduce a large quantity of inoculum into a seed field,” Macrae says. “If they arrive clean, they will still effectively spread whatever inoculum is in the field.”

While soybean aphids are not as efficient in vectoring pVY as other aphids, such as green peach aphids, they can still cause significant damage due to their high numbers, he says, unless they are first managed in the border crop with insecticides.

Management strategies

Integrated pest management relies on the notion that pest control must comprise a variety of techniques and minimize the use of chemical pesticides – although the latter can be used when action thresholds are reached.

Macrae’s work has focused on the spatial distribution of insects and the timing of their colonization. He emphasizes a multipronged approach in dealing with pVY. “as an entomologist, my contributions in pVY management have focused on the most effective methods of controlling the aphids that transmit the disease, but I’m heavily influenced by the need to make solutions [that are] both economically and environmentally sustainable,” he says. according to a study by DiFonzo, more than 50 species of aphid can transmit pVY, and when potato species – particularly seed potato, which is especially vulnerable – have little to no tolerance, growers must adopt a sophisticated management approach. “Winged aphids coming from outside the crop are responsible for the majority of pVY spread, and are not killed by insecticides used against potato-colonizing aphids,” the study argues. “Instead, eliminating inoculum, isolating fields, and using a crop border to ‘clean’ aphid mouthparts are a better strategy for pVY reduction.”

Macrae explains that due to the speed with which pVY can be transmitted by vectoring insects, standard insecticides aren’t very effective in suppressing the virus’ spread. “We need different control strategies and a fuller understanding of vector population dynamics to really develop an integrated management program,” he argues. “and that’s ultimately how we need to think about controlling this disease; it’s not going to be just one tactic.”

Macrae says some research has pointed to the efficacy of oil sprays used in combination with crop borders in controlling aphids, but that border cropping isn’t always an effective strategy on its own.

“The bottom line is that there are some uses to border crops, but pVY management has to be an integrated program.”

lIqu ID SEED - PIECE TREATm ENT bm P S

Another tool to help your potato crop get up and growing.

by Carolyn King

Seed potato pieces are at risk of invasion by pathogens that can cause serious emergence and stand problems. Liquid seed-piece treatments are a fairly new option for dealing with some of these pathogens. Dr. gary Secor, a plant pathologist at north Dakota State University, offers potato growers a set of best management practices (BMps) for these liquid treatments.

Fungicidal seed-piece treatment products come in dust or liquid formulations. Secor looks at two examples of liquid products now available on the Canadian market: emesto Silver (prothioconazole and penflufen), available with an insecticide in Titan emesto; and Maxim D (difenoconazole and fludioxonil), available with an insecticide in Cruiser Maxx potato extreme.

Secor explains that these two liquids are effective in controlling disease, plus they have some important advantages over the powder products. “The two liquid seed treatments are broad spectrum; they control several seed-borne fungal diseases including rhizoctonia, fusarium dry rot and silver scurf. although rhizoctonia and fusarium dry rot can also be soil-borne, seed treatments help manage the seedborne aspects of those diseases.

“The liquid treatments also offer ease of handling compared to the dusts. Dusts are difficult to calibrate and to get the same amount on every seed piece. The liquid seed treatments go on at ultra-low volumes, and you can control the spray to get the same amount on every seed piece.

“But the most important advantage, and the driving factor behind [using liquids], is improved worker safety. Workers are not exposed to all the dust that is produced with a dust seed treatment,” Secor says.

In addition, the two liquid products have some active ingredients that are different than those found in the powder seed treatments and in-furrow fungicides, providing more choices for rotating fungicides to slow the development of resistance.

What about bacterial soft rot?

“probably the most frequent cause of seed decay is bacterial soft rot. Bacterial soft rot is not controlled by seed treatments directly because it’s a bacterial disease and the seed treatments are fungicides, which control fungal diseases,” Secor notes.

He explains that the bacterial soft rot pathogen requires a combination of three conditions to cause the disease. “It needs an entry point for infection. It also needs wet conditions. and it needs warm temperatures, and the warmer it is the faster the decay goes.”

The bacteria can enter potato pieces through the lenticels (the tuber’s breathing pores) or wounds from cutting the tubers or other

injuries, such as the wounds caused by fusarium dry rot.

“So, managing fusarium by using a seed treatment indirectly controls bacterial soft rot,” Secor says.

Since wet conditions favour bacterial soft rot, growers may be worried that applying a liquid seed treatment might increase the risk of the disease. Secor has several recommendations to help prevent problems with soft rot decay when using a liquid: “one is to be sure you put on that ultra-low volume of the liquid seed treatment as the label says – don’t exceed the amount of water recommended on the label.

“Then, if possible . . . allow the seed pieces to dry before the seed goes into the truck or before it’s planted. That will minimize any wet conditions.

“and then, of course, do not plant into wet soil, because planting into wet soil, regardless of whether you have a seed treatment or not, will result in bacterial seed decay,” Secor says.

If you are temporarily storing treated seed pieces before planting, check the product label for any specific requirements. Secor provides some general guidelines for storing seed pieces: “Store the pieces in piles that are no higher than head height, about 1.8 metres high. provide plenty of air circulating through those cut potatoes; it helps wound healing and it helps get rid of that excess moisture that can result in seed decay. Store the pieces at about 10 C. and, of course, keep the pieces out of the sun and rain.”

application considerations

Secor has some advice to help growers decide whether or not to apply a seed-piece treatment. “With rhizoctonia, if you have five per cent or greater on the seed, you should probably use a seed treatment. If you have more than one per cent fusarium dry rot in a seed lot, you should use a seed treatment.

“and if you want to control silver scurf because you’re a table stock grower and appearance of the tubers is everything, then one of the best strategies is a seed treatment,” he says, “because as far as we know the inoculum is all seed-borne, not soil-borne.”

However, Secor notes, “The seed treatments do not seem to give control of black dot blemish of potatoes, which is especially important for table potatoes.”

one of the things Secor likes about the liquids is the addition of colorants to some products. “If you’re using a liquid seed treatment that has a colorant in it, you can actually see whether you’re getting good coverage on the seed pieces, and of course, coverage is everything.”

The ability to check that you’re getting complete coverage is

very helpful, according to Secor, especially when you’re adjusting, modifying or fabricating applicator equipment. “In my opinion, one of the limiting factors of using a liquid is the application technology. Farmers are really good at inventing and fabricating machinery to accomplish a specific job, and there is some good equipment out there for ultra-low volume coverage of seed pieces,” Secor says.

“But because liquid seed treatments are so new, I think there is room for some improvements to ensure the equipment can absolutely apply the right ultra-low volume with 100 per cent coverage,” he says.

“Certainly, farmers can modify some of the existing applicators to make them even better because farmers are working so closely with the equipment.”

other tips

Secor outlines several other practices that help minimize disease and decay early in the growing season.

of course, one practice is to buy good-quality seed. “There are many factors to consider for selecting good seed, and certainly you want freedom from disease – low amounts of potato virus Y and potato mosaic virus, no ring rot, no late blight, minimal rhizoctonia, minimal fusarium, minimal silver scurf – a minimal amount of the diseases you can see,” he explains.

“It’s also good to have physiologically younger seed because it generally performs better,” Secor says. “and, of course, you don’t want seed that has been injured, frozen, sunburned or mechanically damaged.”

Secor advises inspecting the seed before you buy it and then handling it carefully during the transportation from the seed grower’s farm to your farm and out to your field. “Most of the pathogens will enter through a wound, so handling the seed gently during the whole process is probably the number one factor for making that seed perform well,” he says.

Secor recommends doing everything you can in your operation to prevent injuries to the seed, before and after cutting. That includes things like reducing or avoiding drops, adding padding in places where the seed might be damaged, and using sharp cutter

blades so the wounds heal quickly.

Frequent disinfection of cutting equipment is always a good practice to reduce the spread of seed-borne diseases. and it’s especially crucial if you have seed with bacterial ring rot because the liquid seed-piece treatments do not control it. Spread of seed-borne late blight during cutting can also be a serious issue, but growers recently gained a liquid treatment option with the registration of Bayer CropScience Canada’s reason (fenamidone) for use as a seedpiece treatment to protect against seed-borne late blight.

“My recommendation is to always disinfect the cutting equipment between seed lots. If you have an infected seed lot, the infection may spread within that seed lot, but you don’t want to infect a new seed lot. So the best thing to do is to completely sanitize your cutter and cutting equipment between seed lots at a minimum,” he says.

Secor also recommends doing everything possible to get the potato plants up and growing on their own root system, independent of the seed pieces, as quickly as possible. He suggests three practices that will help.

“Warm the potatoes prior to planting so they just begin to sprout and then plant them into warm soil. The optimum we recommend is that the seed and the soil be at the same temperature and that temperature should be 10 C – that’s an absolutely perfect way to plant potatoes,” Secor says. often growers are able to warm the potatoes from the storage temperature of 4 C up to 10 C by simply using fans to move outside air, because outside air is typically around 10 C as planting time approaches. a pulp thermometer can be used to monitor the pulp temperature of the seed.

Secor continues, “also, plant potatoes into medium soil moisture; the soil should not be too wet or too dry.

“and don’t plant them too deep. Sometimes it is better to plant them shallow to get them up on their own roots,” he says. “Then you can go through the hilling process at the same time as you’re doing another field operation like applying a herbicide or doing a cultivation.”

If you’re dealing with seed-borne fungal diseases, a liquid seedpiece treatment can be a valuable tool in an integrated approach to getting your potato crop off to a great beginning.

Confi dence is quiet, otherwise you’re just bragging. In this business, it’s not about what you say – it’s about what you do. And Titan® Emesto™ seed-piece treatment sure delivers. It’ll help protect your crop against the broadest spectrum of insects and against all major seed-borne diseases, including rhizoctonia, silver scurf, and fusarium – even current resistant strains. When you can see that your coverage is this good, con dence comes naturally. Visit TitanEmesto.ca and see what con dence can do for you.

or

bRASSICAS in POTATO ROTATIONS

Research shows canola and its cousins can reduce certain diseases and improve potato yields.

by Carolyn King

If you’re dealing with some tough soil-borne diseases, adding canola, mustard or rapeseed to your potato rotation could help.

That important finding emerged from recent potato rotation studies in Maine, led by Dr. Bob Larkin, a research plant pathologist with the United States Department of a griculture (USDa ).

o ver the last 12 years or so, the USDa researchers have conducted more than 70 trials to investigate the effects of different rotations on soil-borne diseases in potatoes and on potato yields. although the results varied from year to year and field to field, overall, Larkin and his research team found that crops in the Brassicaceae family, such as canola, rapeseed and mustard, consistently reduced potato diseases like black scurf, common scab and Verticillium wilt, and significantly improved potato yields.

now researchers in atlantic Canada will be examining the

effects of Brassica crops as part of a major potato rotation project.

three-pronged

attack

Larkin explains there are three general mechanisms by which rotation crops may reduce soil-borne diseases – and Brassica crops likely act in all three ways.

“The first mechanism is that the rotation crop serves as a break in the host-pathogen cycle,” he says. “This mechanism is in effect any time you have a rotation crop that does not have the same pathogens as your host crop. This is a general strategy of increasing rotation length by adding other types of crops. The longer the time between your host crop, the more its pathogen

aBoVe: one of the more than 70 Usda studies in Maine looking at the effects of crops like mustard, rapeseed and barley in potato rotations.

population declines.”

“The second mechanism is where the rotation crop causes physical, chemical or biological changes in the soil environment,” Larkin says. “It may stimulate microbial activity and diversity, it may increase beneficial organisms, and things like that, which then help compete with pathogens and reduce pathogen populations.” This mechanism varies with different rotation crops.

“The third mechanism is where the rotation crop has a direct inhibiting effect on either particular pathogens or general pathogens,” he says. The rotation crop may release suppressive or toxic compounds in its roots or residues, or it may release compounds that stimulate certain beneficial microbes that suppress pathogens. o nly some crop species have this mechanism.

The first mechanism by itself may not be very effective for controlling some soil-borne pathogens that can survive for many years without a host plant.

Brassicas are well-known for the third mechanism. They contain compounds called glucosinolates, and when Brassica plant materials are incorporated into the soil, the glucosinolates break down to produce other compounds, called isothiocyanates. Isothiocyanates are biofumigants that are toxic to many soil fungi, especially fungal pathogens, weeds, nematodes and other pests.

Larkin’s research shows Brassica biofumigant activity is greatest when the crop is incorporated into the soil as a green manure. However, even when a Brassica crop is harvested and then the remaining crop residues are incorporated, there is still some biofumigant effect. The amount of the biofumigant effect also depends on the Brassica crop’s glucosinolate levels; canolas have relatively low levels, rapeseeds somewhat higher, and mustards have the highest.

“With any of those Brassicas , you will get some benefit from incorporating the crop residues. and it is a measurable and real effect on both potato yield and on reduction of potato diseases,” he notes.

a s well, Larkin’s studies indicate Brassicas also provide the second mechanism.

“ Brassicas seem to have an ability to alter soil microbial communities in different ways which is not necessarily

TITUS™ PRO: THE STRAIGHTEST PATH TO A CLEANER FIELD.

Introducing new DuPont™ Titus™ PRO herbicide for potatoes. As a convenient co-pack, Titus™ PRO brings together rimsulfuron and metribuzin to deliver exceptional post-emergent control of all kinds of grassy and broadleaf weeds. By combining two modes of action, Titus™ PRO is also a valuable resistance management tool and keeps your re-cropping options fexible. One case treats 40 acres. One try and you’re sold.

Questions? Call 1-800-667-3925 or visit tituspro.dupont.ca

DuPont™ Titus™ PRO

related to their amount of glucosinolates or their ability to act as a biofumigant. I think the aspect of how they change the soil microbiology is equally important to their biofumigant effect,” he says.

For example, the USDa researchers found that canola and rapeseed sometimes do a better job at reducing black scurf ( Rhizoctonia solani ) than some of the higher glucosinolate mustards, and the effect on black scurf works even without incorporating the Brassica crop.

However, Larkin’s studies also show that managing some other diseases – like powdery scab ( Spongospora subterranean ) and Verticillium wilt – requires a full green manure.

two-year rotation is too short If disease suppression is a major goal of your potato rotation, then Larkin’s research results provide some key factors to consider.

First, a Brassica ’s disease suppression effect won’t last forever, so the potato crop should immediately follow the Brassica in the rotation to get the greatest benefit.

Second, a two-year rotation will not effectively reduce disease in the long run. Larkin found that no matter what crop was in a two-year rotation with potatoes, certain pathogens tended to build up over time.

For example, in one 10-year study the researchers compared two-year rotations in fields where common scab and Verticillium wilt were not problems at the beginning of the period. But by the end of the study, both diseases had become substantial problems in all of the two-year rotations. The canolapotato and rapeseed-potato rotations had significantly lower disease levels than the other rotations, but they still had gradually increasing amounts of common scab and Verticillium wilt.

“So we recommend a three-year rotation as your first line of defence, and then including a disease-suppressive rotation crop in one of the years of that three-year rotation,” Larkin says.

a Brassica green manure could be a good choice for the disease-suppressive crop, or you could grow a Brassica as a fullseason crop and follow it with a diseasesuppressive cover crop. “The addition of a cover crop like winter rye or ryegrass,

in combination with your Brassica, can provide a significant addition to the disease reduction,” he notes.

even though the grower would not be earning any direct income from a green manure or a cover crop, these options can be valuable tools to get serious soilborne disease problems under control.

“That’s really how we first got into this research,” Larkin explains. “Some potato growers [in Maine] had some soils with substantial disease problems, and they wanted to try whatever they could to get those soils back to where their potatoes would be producing better. So they were willing to give up a seasonal crop for a year or two, to try to get the pathogen populations down to controllable levels.”

(Two seasons of a green manure might be necessary if the field has very high pathogen populations.)

a third factor to consider is whether the rotation crops share any pathogens with potatoes. In Maine, the only shared pathogen that increased in potatoBrassica rotation trials was sclerotinia.

In his own studies, Larkin hasn’t had any sclerotinia issues because sclerotinia is not common in Maine potato fields. However, a researcher at the University of Maine found two fields with sclerotinia and did some rotational trials there.

Sclerotinia increased in those two fields when canola or rapeseed was in a rotation with potatoes.

“So if you have a field with a history of sclerotinia problems, then a Brassica may not be the best rotation crop for you,” says Larkin. alternatively, adding a cereal crop to a potato- Brassica rotation may help because cereals are not susceptible to sclerotinia.

Maritimes rotation project

The major potato rotation project now underway in atlantic Canada is examining various crop options including canola and some other Brassicas

Dr. aaron Mills, a research scientist with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) in p e.I., is leading the project. He is conducting trials at aaFC’s Harrington research Farm in the province, involving nine different three-year rotations.

The project is funded under g rowing Forward 2, with support from aa FC and the e astern Canada o ilseeds Development alliance Inc. McCain Fertilizer division is collaborating by conducting a similar study in new Brunswick.

g enerally, the project’s three-year rotations involve a year of potatoes, a year of another high-value crop, and a year of a more diverse crop mix or a biofumigant

larkin found that potato rotations with crops such as canola and mustard reduced certain potato diseases and improved potato yields.

crop. “We’re looking at canola, soybean and corn [as the high-value crops], and at other, more diversified phases in the rotation, including blends of a Brassica , a grass and a legume all planted at the same time,” Mills explains.

He notes, “The canola acreage is increasing slightly in prince e dward Island, it is one of the higher-value oilseed crops, and it does very well under our climate. and it’s important to diversify the cropping system, so if you can add in a different crop and it’s a higher value crop, then that’s a win-win situation.

“Canola has also been touted to have some biofumigatory effects, and the Brassicas in general produce certain compounds shown to have effects on diseases and insect pests,” Mills says. “Buckwheat is another [crop that supresses pests], based on research by my colleague Dr. Christine noronha, so we’re also including buckwheat in the trials.”

Mills and his research team will be scouting all the crops in the different rotations for disease and insect pests. Sclerotinia is one of the issues they’ll particularly watch for. Mills notes, “We are starting to see an increase in sclerotinia [in p e .I.], and a lot of the higher value crops in these rotations are

hosts for sclerotinia.”

along with collecting data on crop yields, diseases and insect pest issues, the researchers will also be monitoring such factors as crop biomass and soil organisms including nematodes. and Dr. Judith nyiraneza, an aa FC nutrient management specialist, will be tracking nutrient dynamics in the soil.

The researchers conducted preliminary work in 2013, and 2014 was the project’s first full year. The current funding will take the project to 2017-18, but Mills hopes to run it for nine to 12 years.

“You can’t really look at the trends until you get at least a couple of phases of each rotation. So one of the big determinants for the project’s success is how long we can run the rotations,” he says.

Putting it all together

The effects of different rotation crops on potato diseases and yields may differ somewhat from region to region. Mills emphasizes the importance of evaluating rotations in different regions: “ p. e .I. soils are different than those in o ntario or out west, and how the crops respond is not exactly the same.”

Mills’ overall advice for effective potato rotations is that more diversity is better. “From what we’ve seen so far

with some of our other studies, it’s all about increasing the crop diversity. You can increase the length of the rotation by adding different crops. o r, if you have a shorter rotation, you can increase [the in-year diversity]. That seems to show some benefits to the soil and to the organic matter especially,” he says.

Similarly, Larkin advises using multiple rotation-related practices for enhanced disease suppression. e xamples include: increasing the rotation’s length, adding crops that also have the second and third mechanisms of disease suppression, and including cover crops and green manures.

His research shows that, although these practices will not completely eliminate potato diseases, they will reduce soil-borne potato diseases and improve potato yields.

a s well, these kinds of sustainable practices provide other long-term benefits for a farm’s production capacity and potential longevity. These benefits include improving overall soil health, enhancing soil microbial diversity and activity, increasing soil organic matter and building a healthier agro-ecosystem. “all these practices are components of making a better, more sustainable system,” Larkin says.

For potato growers in Maine, Larkin’s general rotation recommendation is “a three-year rotation, with one year of a grain such as barley, then a cover crop like ryegrass or winter rye, then a Brassica , which could be a mustard green manure or a harvestable oilseed Brassica crop, and then potato in the third year of the rotation.”

He notes, “That recommendation is based on a lot of different studies looking at what is the best system for reducing disease, what is the best system for improving soil quality. now [in our current studies] we are trying to combine those into a rotation that incorporates aspects of all of those things and seeing if it really does everything we hoped it would.”

a major potato rotation project in P.e.i. is examining various crop options including canola and some other Brassicas.

bREEDING Ou T T ub ER DE f ECTS

Exciting new breeding efforts are producing varieties resistant to stress-induced defect disorders.

by Treena Hein

Many things can disrupt normal tuber growth, leading to reduced yields and reduced profits.

Uncontrollable environmental factors, such as temperature extremes, can contribute to malformed tubers and a defect called hollow heart, and global climate change is expected to bring more temperature extremes and drought in the future. However, cultivation practices also matter, and things like inadequate, excess or uneven levels of soil nutrients can disrupt normal tuber development and cause undesirable physiological disorders.

“If farmers do their best to ensure uniform and adequate soil moisture and fertility throughout tuber initiation and growth, losses from many physiological disorders can be avoided or minimized,” says Dr. Benoit Bizimungu, an agriculture and agriFood Canada (aaFC) research scientist and potato breeder in Fredericton. “of course, most farms are not irrigated, and even if all care is taken and irrigation is used, things like high or low temperatures can cause defects. Furthermore, the causes of some defect disorders are not well known.”

Malformation of the tuber actually occurs after environmental stresses have temporarily slowed or halted tuber growth. “The resumption of growth after this stress can result in non-uniform secondary growth,” Bizimungu explains. The defect known as hollow heart is also associated with fluctuating growing conditions, but also by soil nutritional imbalances, or conditions that favour rapid tuber enlargement. although the incidence of hollow heart is influenced strongly by the environment, Bizimungu says there is also a genetic component to its expression. “Under conditions promoting its development, some cultivars exhibit more severe expression than others,” he notes. “The two standard potato varieties (russet Burbank for frozen French fries, and atlantic for chip processing) are both susceptible to environmental stresses leading to hollow heart and other tuber defects.”

Because not all the unfavourable conditions that contribute to growth disorders can be controlled, it’s fortunate that genetic improvement can play a role in reducing the prevalence of defects and thereby avoiding or minimizing losses. of course, no cultivar is completely resistant to every disorder, but some are less susceptible than others. Tubers used for seed, fresh market, or processing may be affected differently by environmental stresses, Bizimungu explains, and certain disorders are not as important

in some of these end uses as they are in others (consumers and processors prefer uniform potatoes, for example).

Breeding efforts

as part of the national potato breeding program, Bizimungu and his team have carried out evaluation and selection of breeding clones for resistance to stress-induced defect disorders over the last six years. Selection for each generation was narrowed down by the team from approximately 100,000 original lines planted in the first year of selection. after planting under rainfed production in eastern Canada at the Benton ridge breeding substation in new Brunswick, and under irrigated conditions at the Vauxhall research substation in southern alberta, the number of clones was narrowed down to about 50. Superior selections were then chosen for adaptation evaluation, in collaboration with industry, at eight test sites across seven provinces.

The list of outstanding selections nearing completion or in advanced industry tests includes French fry clones CV99222-2, ar2010-01 and ar2010-02, chip clones ar2010-03, ar201302 and ar2014-02, and dual French fry/fresh clone CV01236-3. They have all shown much better fry colour than russet Burbank or atlantic. all of them have also shown greater marketable yields due to fewer defects than both russet Burbank and atlantic by four to 21 per cent in experimental plots. Bizimungu’s preliminary data shows that CV99222-2 and CV01236-3 outperformed russet Burbank in western Canadian trials conducted under irrigation in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and alberta. These clones also appear to do well in rain-fed conditions in new Brunswick. Clones ar2013-02 and ar2014-02 also appear to have a wide geographic adaptation, Bizimungu notes, and outperformed atlantic in most national test sites in terms of marketable yield.

“The national trials aim to check performance of these selections showing the potential to offer improved yields and processing quality under different conditions and different local environmental stresses,” Bizimungu says, “in order to choose the most promising ones for release to industry for further testing. Upon successful completion of industry testing, their registration as cultivars will follow.”

Industry can visit aaFC’s accelerated release program website to access trial data, with locations and performance, to decide which selection to request for further testing, with the option to license.

We have a history of protecting what matters most to us, and creating new and innovative ways to enhance that level of protection. Reason ® seed-piece treatment for seed-borne late blight protection is proof of that. You counted on Reason to protect against late blight and early blight through foliar applications, and now you can start protecting your potato crop with Reason at planting too. As a seed-piece treatment, Reason can be used alone when seed-borne late blight is a threat or mixed with Titan® or Titan Emesto™ for the highest level of disease and insect protection you can achieve.

GEAR UP WITH REASON SEED-PIECE TREATMENT – AN EVOLUTION IN