DuPont™ Coragen® insecticide

DuPont™

Coragen

®

puts you in control of your potato fields with extended residual control of European corn borer and resistance management for Colorado potato beetle

Insect control is serious business. Some management decisions can be delayed but when a European corn borer (ECB) or Colorado potato beetle (CPB) infestation hits, it needs to take top priority.

There are a number of factors that play into choosing the right insecticide for the situation. In the long term, you want to manage the potential for resistance development. In the short term, you want to protect your crop. That means choosing the most effective product considering what might be uncooperative weather and a rapidly evolving pest population.

European corn borer –DuPont™ Coragen® will put you in control

Coragen® gives you a better chance of controlling more ECB at peak egg hatch with its wide window of application.

The experts agree – for the best insect control you have to set and monitor pheromone traps to gauge moth numbers. Once you find moths, start looking for egg masses. However, nailing the egg hatch timing can be tough. In different regions over the past two years we’ve seen either cold weather that turned hot causing a sudden, unexpected flush of hatches, or weather that stayed cold, causing a long, drawn-out hatch.

Take command using an insecticide with a longer residual. The extended residual control delivered by Coragen® means that the plant is protected for a longer period of time than

with contact-only insecticides. It can replace two or three applications of other treatments and provides more flexibility in application timing.

Colorado potato beetle –Coragen® controls resistant biotypes

Colorado potato beetle was a scourge to potato growers when the pest developed resistance to previously used insecticides. Those days could come back at any moment unless you start using new modes of action now.

Often the first sign of resistance is confused with reduced residual control. CPB is highly adaptive and growers need to continue to be vigilant as they rotate chemistry and monitor for resistance.

Powered by DuPont™ Rynaxypyr®, Coragen® features a novel mode of action from a whole new class of chemistry: Group 28, the Anthranilic Diamides. It provides control of ECB and CPB, including imidacloprid-resistant biotypes. Coragen®, with an entirely new mode of action, can play an important role in your resistance management strategy.

Coragen®: Powerful action with extended control

With Coragen®, target pests stop feeding within minutes of ingestion, which results in nearly immediate crop protection. And, because Coragen® penetrates the leaf and is translaminar, it’s protected from wash-off.

Coragen® insecticide puts you in control of your toughest insect pests:

• Extended residual control protects plants for longer than contact-only insecticides

• Whole new class of chemistry with a novel mode of action - so you can even control pests that are resistant to other chemistries

• Controls hatching insects all the way through to adult stages of development

• Field-proven under Canadian growing conditions

• Easy on bees and other beneficials, so it’s a good fit in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs

20, 25 5, 26

Pests and Diseases

There is very little that is new under the sun and in potato fields in Canada, but there are new ideas, new practices and new formulations to help growers battle diseases such as Rhizoctonia and pests such European corn borer.

Plant Breeding

Consumer demand is fuelling much of the demand for healthier eating, and researchers and breeders are working to bring new varieties and new consumer-friendly traits to the fields.

March 2011

EDITOR

Ralph Pearce • 519.280.0086 rpearce@annexweb.com

CONTRIbUTORS

Blair Andrews Treena Hein Rosalie I. Tennison

WESTERN SALES MANAGER Kevin Yaworsky • 403.304.9822 kyaworsky@annexweb.com

EASTERN SALES MANAGER

PRODUCTION

POTATO PEST CONTROL GUIDE

IntroduCtIon

Once again, Top Crop Manager is offering an early spring edition of Potatoes in Canada, sponsored by DuPont Canada. This issue extends the potato production features published in the regular edition a month ago. As an added feature, this edition includes an updated “Guide to Potato Pest Control.” It provides comparative notes on products and the various diseases, insects and weeds they control. Be sure to crosscheck

provincial guidelines and product labels before making any final decisions.

Other features in this issue cover a number of topics on production and storage of potatoes. Some decisions on protecting the crop’s yield potential must be left until the growing season is well underway. Keep this issue on hand for a quick reference.

Ralph Pearce Editor

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT.

Printed in Canada ISSN 0705-3878

CIRCULATION

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Plant BreedIng

Lowering the glycemic index of potatoes

by Blair Andrews

The push is on for potatoes to shake reputation as a ‘high carb’ food.

Ateam of Canadian plant and nutritional scientists is working on new varieties that might make healthconscious consumers give potatoes a second look. Despite being rich in nutrients, vitamins and minerals, potatoes are often the subject of negative publicity. The Atkins Diet that had people shunning carbohydrates is a well-known example. Another is the low glycemic index, or low GI diet. People who are interested in low GI use a rating system to choose foods to help them lose weight and manage health issues, including diabetes. While freshly cooked potatoes tend to have high GI numbers, the Canadian research is targeted at improving their rating.

The glycemic index is not a diet, but a system that classifies carbohydrate foods based on how rapidly they are broken down and absorbed into the bloodstream. Certain carbohydrate foods, like freshly cooked potatoes, elevate blood sugar levels more quickly than other foods. Dr. J. Alan Sullivan, professor in the Department of Plant Agriculture at the University of Guelph, is one of the researchers trying to develop low GI potatoes. He says the key to achieving the result is the type of starch in the potato. “When humans digest it, the starch in the potato is broken down very quickly to sugar and absorbed into the bloodstream, and it creates a spike in blood sugar levels,” says Sullivan, explaining why the starch in potatoes is called a rapidly digestible or nonresistant starch.

The ‘where’ of starch digestion is key Sullivan notes that many foods have resistant starch, meaning it is not digested in the small intestine. When it gets into the large intestine, it is fermented by colonic bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids, which are available to the human host as energy. The slower digestion of the starch reduces the glycemic index. “If the amount of resistant versus non-resistant starch can be altered in a particular variety, then the glycemic index may also be changed. So the team is working on changing the relative proportions of non-resistant and resistant starch,” says Sullivan, referring to his work to alter the starch profile of potatoes.

The research team is examining how the starch is accumulated in the tuber and how genomics and plant breeding can be used to create new varieties. With the assistance of graduate student Stephanie Bach, Sullivan says they are looking at the impact of the environment and genotypes on starch profiles, and breeding behaviour of genotypes with different starch profiles. The goal is to create potato varieties with altered starch profiles that result in a lower glycemic index. “We’re specifically looking for genotypes that have a higher level of resistant starch and a lower level of non-resistant starch,” says Sullivan. “In other words, genotypes with a high level of slowly digestible starch and a low level of rapidly digestible starch.”

The study began with genotypes obtained from the plant breeders at the Potato Research Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The genotypes were then measured for different starch profiles and the number was narrowed down for further study. “Some of them do look promising in terms of their starch profile. We’ll know more in a few months once we analyze the samples,” says Sullivan. “It is one of the most exciting projects we have with potatoes because of the potential payoff for the industry and human health. We hope to alter the starch profile but I’m not sure how much is possible.”

A lengthy, involved process

Altering the starch is just one step. Sullivan says the success of the effort will be determined by the ability to reduce the glycemic index number. He adds that the only way to know for sure is to actually test the blood sugar response in humans. For that part of the study, plant researchers are enlisting the help of nutritional scientist Dr. Tom Wolever of the University of Toronto. Wolever was involved in the original development of the GI concept, supervised by Dr. David Jenkins at the university. “My PhD thesis involved validating the GI and developing the methodology so that it’s accurate and precise,” says Wolever. “I think we have made an impact on the methodology and we have done studies internationally with 28 research laboratories. We can show this measurement works the same on food around the world.”

Wolever says this potato study is exciting because the researchers are going to learn more about how the starch structure and starch chemistry interact with the physiology in people. “I believe it’s critical to what I am interested in, which is how carbohydrate foods influence our health. The opportunity to work with chemists, who understand the plants, doesn’t happen very often,” he explains.

The early testing so far has revealed that the preparation method of the potatoes is an important factor. Wolever says the GI values were much higher in freshly cooked potatoes when compared to cold. In a study by Tracy Moreira, one of Woelver’s graduate students, the variety that had the

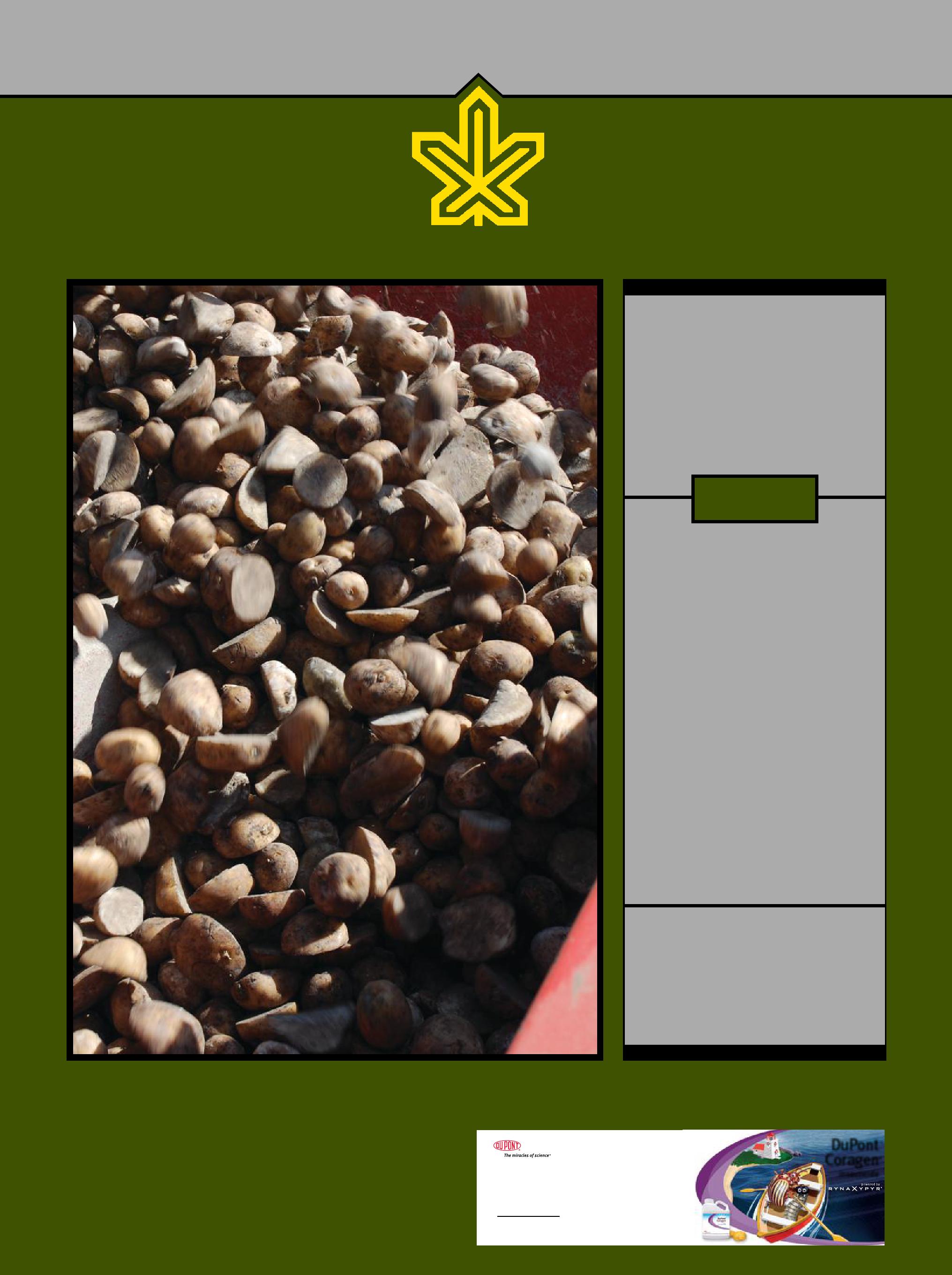

Researchers in Canada are trying to find a way to lower the glycemic index in potatoes by raising the level of slowly digestible starch and lowering the level of rapidly digestible starch. Photo by RalPh PeaRce

Plant BreedIng Pests and dIseases

highest GI when it was hot, saw a GI reduction of 50 percent when it was allowed to cool. Meanwhile, other varieties that showed lower GIs when they were hot, maintained the same number when cooled. Cautioning that it is too early to draw conclusions because the research is in its infancy, Wolever says there are implications for how processing impacts the GI. For example, he has had conversations with a group that is trying to develop an instant mashed potato product that is rich in antioxidants. “When they heard our presentation, they thought the product might have a high GI, which might undo the good work they were doing (with antioxidants). So it opens up a lot of dialogue between different groups,” says Wolever.

Looking ahead for consumers

As for when consumers might be able to buy “low GI” potato products, Sullivan says the team must first develop a suite of varieties that can be adapted to different growing regions of Canada and the northeastern part of the US. He says one of his tasks is to study the adaptability and environmental influence on the lines, not only for the agronomic characteristics, but for the starch profiles, as well. “One of the things that this research has done has identified genotypes with different starch profiles. They’re fed back into the breeding program and will be used to create improved lines. That is going to be a long-term process,” says Sullivan. “If we have something in the trials now that has good agronomic characteristics and a much improved starch profile, then I would say (it would be commercially available) in less than five years.”

While it remains to be seen if the research will achieve its goal of producing a better potato, there is confidence that the study marks a new era of crop research. Instead of focusing on agronomics, processing consistency or even taste, more studies are delving into characteristics that would be of interest to the consumer in terms of health. “I’m excited about being able to do some really good science,” says Wolever. “We’re going to be leading the world on potato research because there is nothing else out there with this kind of combination working together.” n

Checking up on Rhizoctonia and early blight

Best management practices and prevention of fungicide resistance.

Rhizoctonia is a fungal pathogen found wherever potatoes are grown, and one to watch because it can survive in the soil for many years. “It can gain a foothold at the start of the season, and can certainly severely hinder stand establishment,” says Dr. Rick Peters, potato pathologist at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Crops and Livestock Research Centre in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. “It’s especially important to control it in cooler, wetter years. When succulent underground plant tissues are moist, they are ripe for attack.”

Peters was called out to several fields in early summer 2010 to do disease diagnosis, and found that Rhizoctonia (or “rhizoc” for short) was the culprit. “The stands were poor in vigour and in health,” he says. The plant damage caused by rhizoc is apparent early in the season, and later in moist soil, the black scurf structures (sclerotia) form a hard crust on the tubers as an overwintering stage. If there are any present at all on seed in the spring, the disease can spread. “The number is two percent,” stresses Peters. “If there’s a

Early blight, another fungal pathogen that growers are having to deal with, can survive in residues, in soil, on infected tubers and on other hosts.

Photo by PeteR DaRbishiRe

higher percentage of the surface area of the seed covered with sclerotia than that, you’re going to be in trouble. After your plants have come up, you don’t have any recourse.”

Prevention the key

Once the seed is cleaned, Peters advises using seed treatments. However, he says that while seed treatments will help reduce some infections, they are not a substitute for clean seed. “In addition, if you control the pathogen on the seed and not in the soil, or vice versa, you are in trouble,” he says. “You must do both.” Therefore, in addition to seed treatments, also use

Research update: DuPont Vertisan fungicide

A new fungicide for treating and preventing Rhizoctonia, early blight, powdery mildew and grey mould, has been submitted for registration to the Pest Management Regulatory Agency. Research indicates that DuPont Vertisan offers control of these foliar and soil-borne fungal diseases in broad-acre crops, including canola, pulses, potatoes, sunflower and sugar beets.

The new active ingredient in Vertisan is called penthiopyrad. It stops the growth of plant pathogenic fungi by blocking cell respiration, and inhibits spore germination and mycelial growth. “Vertisan will be a valuable resistance management tool because of its Group 7 chemistry and next-generation Complex II mode of action,” says Jim Irish, specialty products manager at DuPont.

Vertisan moves through treated leaves to stop infection and protect the entire leaf with preventive and, on certain diseases, curative activity. It offers strong residual control, excellent crop safety, outstanding rainfastness and tank-mix compatibility.

A submission has been made for Vertisan to be applied by ground and air. For Rhizoctonia, it will be applied in-furrow at planting.

Pests and dIseases

a crop protection product in furrow at planting.

Length of crop rotation is also very important. “Our research has shown that three years is better than two years, and four years is better than three years,” says Peters. “The fungal soil population just breaks down over time, so the longer it’s left without a host, the better.”

Canola and some of the mustards (for example, Brassica sp.) have shown particular rhizoc suppressant abilities in Peters’ research studies. “You can grow canola and still get some suppression of rhizoc in potatoes the next year because it excretes some chemicals from its roots that suppress the fungus,” says Peters. “However, you will get a much greater effect if you till the canola into the soil as a green manure. The canola tissues will release toxins that kill the pathogen in greater amounts this way, and tilling it in will also increase microbial activity in the

soil, which also in turn inhibits rhizoctonia growth.”

Lastly, if a grower is not sure which pathogen he or she is dealing with, it is best to get infected potato plant tissue samples to the nearest government diagnostic lab as soon as possible, advises Marleen Clark, a plant disease diagnostician with PEI’s Department of Agriculture in Kensington. “An accurate disease diagnosis can then be correctly treated,” she says, “and in the end, an effective treatment can save farmers money.”

Early blight fungicide resistance

Alternaria early blight is another fungus to watch, particularly in the Prairie provinces. It is really only an issue in the Maritimes when drought conditions appear; very dry weather weakens and stresses potato plants, putting them at risk for infection.

Early blight is also a concern because in a 2008 study, Peters found that the

pathogen demonstrated widespread resistance to strobilurin fungicides (which include Group 11 products) in the potato fields of Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta. “None was apparent at that time in PEI, but continued monitoring would be advisable,” says Peters.

Similar to many other fungal pathogens, early blight can survive between potato crops in residue, in soil, in infested tubers and on other hosts. To manage early blight, it is important to use clean seed, destroy diseased vines (burning is recommended), maintain soil fertility and use as long a crop rotation as possible.

Early blight first becomes visible as very small brown spots on older leaves. These spots grow into concentric rings (resembling a “bulls-eye” target), which results in extensive leaf loss and lower yields. Infection on tubers appears as dark, sunken, roundish areas with raised borders. n

Canola has shown some ability as a Rhizoctonia suppressant, either as an oilseed crop or as a green manure. Unfortunately, this property is better news for Prairie potato growers than for those in the Maritimes.

Photo by RalPh PeaRce

ESN® technology for potatoes.

Potatoes require high N rates, and timing is critical. The crop consumes 60 to 80% of its total N needs during tuber initiation and tuber bulking. ESN technology controls the N supply until the growing plants need it most. Additionally, it virtually eliminates N loss to the environment. Using ESN technology is a smarter way to grow.

For more information about ESN technology or to locate the field representative in your area, visit us at SmartNitrogen.com or call 800-403-2861

“We have used ESN for the last few years and it has helped us more effectively manage our petiole N content. This has ultimately led to improved yield and quality from the reduced plant stress. Add in the reducing fertigation costs and this equates to improved profitability for our operation.”

Mark Keller

Keller Farms, Shilo and Douglas, MB 15,000 irrigated acres; 5,000 of potatoes

Potato Pest Control 2011

Disease management products

Common name

Chemical group (Rotate groups to manage resistance) (Check label for details)

Acrobat 50WP dimethomorph morpholine

Allegro fluazinam pyridinamine

Bravo 500 F chlorothalonil chloronitrile

Bravo ZN chlorothalonil chloronitrile

Copper 53 W copper sulphate inorganic

Copper spray copper oxychloride inorganic

Coppercide copper hydroxide inorganic

Curzate 60 DF cymoxanil acetamide

Dithane 75 DG mancozeb dithiocarbamate

Echo 720 chlorothalonil chloronitrile

Echo 90DF chlorothalonil chloronitrile

Gavel 75 DF zoxamide/mancozeb benzimidazole/ dithiocarbamate

Headline EC pyraclostrobin strobilurin

Kocide 2000 copper hydroxide inorganic

Lance WDG boscalid anilid

Manzate Pro-Stick mancozeb dithiocarbamate

Parasol WG copper hydroxide inorganic

Parasol flowable copper hydroxide inorganic

Penncozeb 75 DF mancozeb dithiocarbamate

Polyram DF metiram dithiocarbamate

Quadris azoxystrobin strobilurin

Quadris azoxystrobin strobilurin

Ranman cyazofamid cyanoimidazole

Reason fenamidone imidazolinone

Revus mandipropamid carboxylic acid amine

Ridomil Gold 480SL metalaxyl-m acylamine

Ridomil Gold / Bravo metalaxyl-m/ chlorothalonil acylamine/ chloronitrile

Scala SC pyrimethanil anilino-pyrimadine

Serenade ASO

Serenade Max

Bacillus subtilis QST 713 strain

Bacillus subtilis QST 713 strain

Tanos 50 DF famoxadone/ cymoxanil oxazolidinedione/ acetimide

Tattoo C propamocarb/chlorothalonil carbamate/chloronitrile

Important: The Potatoes in Canada Potato Pest Control tables are a guide only. It is highly recommended that growers refer to local provincial guides and labels.

Potato Pest Control 2011

Potato Pest Control 2011

Insect management products

Common name

Chemical group (rotate groups to manage resistance) Application timing

Actara 240SC thiamethoxam thianicotinyl planting

Actara 240SC thiamethoxam thianicotinyl

Admire 240 F imidacloprid chloronicotinyl planting

Admire 240 F imidacloprid chloronicotinyl

Admire 240 F (also see Seed Piece Treatments) imidacloprid chloronicotinyl seed piece

Alias 240 EC imidacloprid chloronicotinyl planting

Alias 240 EC imidacloprid chloronicotinyl

Alias 240 EC imidacloprid chloronicotinyl seed piece

Assail 70 WP acetamiprid neonicitinoid

Beleaf 50SG flonicamid pyridinecarboxamide

Clutch 50 WDG clothianidin neonicitinoid planting

Clutch 50 WDG clothianidin neonicitinoid

Coragen chlorantraniliprole anthranilic diamide

Cygon 480 EC dimethoate organophosphate

Decis 5 EC deltamethrin pyrethroid

Diazinon 500 E diazinon organophosphate

Dibrom EC naled organophosphate

Endosulfan endosulfuran chlorinated cyclodiene

Fulfill 50 WG pymetrozine pyridine azomethines

Fyfanon malathion

Grapple/Grapple2 imidacloprid chloronicotinyl planting

Grapple/Grapple2 imidacloprid chloronicotinyl

Grapple/Grapple2 imidacloprid chloronicotinyl seed piece

Imidan phosmet

Lagon 480 E dimethoate organophosphate

Lannate Toss-N-Go methomyl carbamate

Lorsban chlorpyrifos organophosphate

Malathion 500 E malathion organophosphate

Matador 120 EC cyhalothrin-lambda pyrethroid

Monitor 480 EC methamidophos organophosphate

Movento 240 SC spirotetramat tetronic/tetramic acid derivatives prior to economic threshold being reached

Nufos chlorpyrifos organophosphate

Nufos chlorpyrifos organophosphate

Orthene75 SP acephate organophosphate

Perm-up permethrin pyrethroid

Pounce 384 EC permethrin pyrethroid

Pyrinex 480 EC chlorpyrifos organophosphate

Rimon 10 EC novaluron benzoylphenyl urea egg hatch/small larvae

Ripcord 400 EC cypermethrin pyrethroid

Sevin xLR carbaryl carbamate

Silencer 120 EC cyhalothrin-lambda pyrethroid

Success 480 SC spinosad spinosyn egg hatch/small larvae

Thimet 15 G phorate organophosphate planting

Thionex 400 EC endosulfuran chlorinated cyclodiene

Titan clothianidin chloronicotinyl seed piece

UP-Cyde 2.5EC cypermethrin

Vydate L oxamyl carbamate

Potato Pest Control 2011

DuPontTM Coragen® insecticide puts you in control of your toughest insect pests. Coragen® is a highly effective insecticide that delivers extended residual control of key insect pests such as European corn borer and Colorado potato beetle. Plus, Coragen® belongs to a whole new class of chemistry and it has a novel mode of action -so you can even control pests that are resistant to other chemistries.

Field-proven under Canadian growing conditions, Coragen® is easy on beneficials and the environment, so it’s a good fit in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) programs.

Take control of your potato fields – with DuPont™ Coragen® insecticide.

Potato Pest Control 2011

control products

(Not registered in all provinces. Some processors do not accept use of all products.)

Belleisle, Tobique/ no postemergence on early varieties, red-skinned, Atlantic, Eramosa

* Conditions apply: Check provincial guides or product labels for details and specific weed control ratings. Some provincial guides include control ratings not shown. Some tank mixes may not be registered in all provinces: additive effects and antagonism may also occur. Some products and tank mixes are only recommended for certain varieties. Various formulations may be available and additional application rates may be recommended.

** Dandelion not on label for some glyphosates. Some potato processors do not approve use of some products.

Important:

The Potatoes in Canada Potato Pest Control tables are a guide only. It is highly recommended that growers refer to local provincial guides and labels as well as processors and packers.

•

Potato Pest Control 2011

Minimum

at time of application. Requires irrigation to ensure activation prior to emergence. Do not apply at or post-emergence.

before potatoes flower/30 days to harvest. Do not apply during periods of extreme drought or excessive moisture.

Grassy weeds Volunteers broadleaf weeds

Perennial weeds

Potato Pest Control 2011

Seed piece treatments

In-storage seed treatment

Important:

The Potatoes in Canada Potato Pest Control tables are a guide only. It is highly recommended that growers refer to local provincial guides and labels as well as processors and packers.

Potato Pest Control 2011

Important: The Potatoes in Canada Potato Pest Control tables are a guide only.

It is highly recommended that growers refer to local provincial guides and labels.

• • • Refer to label product rates specific to seeding rates.

• • • • For disease control add treatment following application of Admire 240.

• • • • For disease contgrol add treatment following application of Alias 240.

• • • S • • • A co-pack of Actara 240SC and Maxim Liquid PSP.

• • • • For disease control add treatment following application of Grapple.

• Plant as soon as possible after treatment. Use second application for cut seed.

S • • •

S

• • •

Treat cut pieces soon after cutting. S=suppression only

Treat cut pieces soon after cutting. S=suppression only

S • • • Treat cut pieces soon after cutting. S=suppression only

Quickly dries and seals cut surfaces and protects seeds in wet, cold soils.

• • Plant as soon as posssible after treatment. Use second application for cut seed.

• Plant as soon as possible after treatment. Use second application for cut seed.

• • • Treat cut pieces within six hours. Do not use after Mertect used in storage.

• • • • S For wireworm suppression and control of above-ground pests, use higher rate.

• Plant as soon as posssible after treatment. Use second application for cut seed.

• • • Apply as a mist on potatoes going into storage

Important: The Potatoes in Canada Potato Pest Control tables are a guide only. It is highly recommended that growers refer to local provincial guides and labels as well as processors and packers.

Pests and dIseases

Variable weather and finding solutions to increased European corn borer pressure

Foliar, residual insecticides protect against ECB.

European corn borer larvae move in and out of the stalk. That might not seem like too bold a statement, but for a grower caught by an unexpected explosion of ECB pressure, this news can save a crop.

ECB pressure across the Maritimes and through the northeastern United States has been increasing. The mild winter of 2009/2010 did not help. “With the recent milder winters we’ve had more larvae survive the winter than in the past,” says Jim Dwyer, the University of Maine’s area crops specialist based in Presque Isle. “The larvae overwinter in the stalks.”

Several fields in Maine were hit hard with ECB in 2010. “If you have a significant insect population and add drought on top of that, you can get a significant yield impact,” says Dwyer. “Fields that had significant ECB activity saw a lot of crow damage, such as shredded vines, as they went after the larvae. In a couple of fields the bird damage as a result of ECB was more significant than the damage from the ECB themselves.”

Dwyer and other researchers have a theory that the increase in ECB pressure is partly due to the decrease in foliarapplied insecticides. “Historically, as we applied foliar materials for control of Colorado potato beetle, unknowingly we were controlling ECB too,” says Dwyer. “We’re not applying the foliar materials for CPB control in late June and early July like we used to, and ECB has become a significant issue for us.”

That is what Dr. Christine Noronha, an entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, also sees. “In the last 15 years (since about 1995) we started to see an increase, and by 2002, growers were seeing significant damage.”

Changes in weather patterns are not only affecting ECB overwintering; variable summer temperatures are

making it harder for consultants when it comes to recommending whether or not to spray a crop. Danny Blanchette is a crop consultant with the Grand Falls Agromart in Grand Falls, New Brunswick. In 2010, he stood in a field of potatoes that was on the verge of being decimated by ECB. Temperatures had gone from consistently cold to hot very quickly. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Blanchette. Both he and the processor were scouting. “I’ve never seen it go from so cold to so hot so quickly. We couldn’t even find the eggs or the hatch. It was done in a week and a half. The moths came in and laid eggs before we could monitor.”

“Typically, we try to get material out to control the larvae,” says Dwyer. “That gives us a three-day window, from egg hatch to when they enter the plant. Within that window the larvae are extremely vulnerable. Assail (acetamiprid) has some ovicidal activity to control eggs. Pyrethroids do a good job of controlling the larvae. Coragen (rynaxypyr) does a good job of controlling the larvae and is a translaminar material with a longer residual.”

Dwyer admits that it can be difficult to hit the right timing, especially for

growers farming a large number of acres.

“We usually spray when the eggs hatch,” says Blanchette. But the larvae got into the stalks of the potato plants and everything looked dire.

Blanchette spoke to Dwyer in Maine, who recommended Coragen, an insecticide from Group 28, the Anthranilic diamides. It causes both rapid cessation of feeding but also has excellent residual, multi-stage control of ECB.

Advantages of residuals

ECB has an Achilles heel that growers can use to their advantage. The pest tends to enter and exit the stalk multiple times. When a product has a longer residual, the ECB pick up the material as they exit the stalk. Dwyer has seen a residual insecticide work in the past in fields that appeared too far gone. “We have seen between 60 and 70 percent control of the larvae after they had entered the plant,” says Dwyer. “Historically, once larvae have entered the plant, we’ve had a tough time getting material to them. I was pleased.”

The field in New Brunswick was saved and produced 250 barrels to the acre. Blanchette estimates that the

The arrival of European corn borer in the Maritimes and the northeastern United States has challenged many growers and agronomists, not only with its numbers, but with the speed of its advances when conditions are right. Photo couRtesy of DR eugenia banks oMafRa

Pests and dIseases

plants would have died and the field would have produced 150 barrels without the spray. “We were shaking ECB carcasses out of the holes in the stems,” he says.

Timing of application is still key but Jim Irish, specialty products manager at DuPont, says it is important to know that ECB moves in and out of the stalk. “With its unique properties, we see why Coragen widens the window of application,” he says. “Along with the extended residual and translaminar activity, Coragen controls hatching insects all the way through to adult stages. These are huge benefits when trying to control ECB, and Coragen often replaces two or three applications.”

It is important to use a product that controls ECB at various stages. Egg hatch can vary tremendously from farm to farm, says Dwyer. When a grower sees dramatic weather change like that, Dwyer says eggs can hatch in as few as three days. It helps to have a product that controls insects at various stages while trying to get fields sprayed at the right time.

A sudden hot spell can cause complications. But during a cold summer, the egg-hatch season can spread over a much longer time period. “During cold summers, the moths keep laying eggs for a longer period of time,” says Noronha. She says sudden temperature spikes can cause a sharp increase in egg laying.

Brian Beaton, potato co-ordinator with the PEI Department of Agriculture, remembers 2009 when people were scouting and not doing cumulative counts. People made the mistake of scouting and counting egg masses one week and then starting from zero the next week. “The summer was cool overall,” says Beaton. “The moths were laying and hatching at different times during a three-week period. People were doing their counts for egg masses but they should have added all the counts together.”

In 2010, Beaton says it was drier and hotter than in 2009 and there was a faster, shorter flush of hatching.

It seems that variable weather is here to stay. Therefore, growers would be advised to consider their insecticides carefully to give themselves some extra breathing room to control ECB. n

BusIness ManageMent

Keeping pace with keeping track

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Tracing food from farm to fork offers some comfort to consumers and protection for growers.

If any lesson was learned after recent outbreaks of food-borne illness, it is: the faster the problem is traced, the sooner it can be fixed and confidence in the food system can be restored. By tracing food from field to the consumer’s plate, the source of a problem can be identified quickly and an entire industry is not targeted unfairly. Such would have been the case if the initial reports of E. coli in spinach from California in 2006 could have pinpointed the farm the spinach came from rather than the entire state spinach crop.

In 2003, an outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or “mad cow disease”) hurt Canada’s beef industry, just as a subsequent “tainted spinach” issue caused the California industry to suffer. But, whereas the beef industry has since managed the issue of traceability to allow a pound of hamburger to be identified as coming from the progeny of a cow in Alberta and a bull in Ontario, the same cannot be said for all vegetable crops. That is changing.

Part of the challenge is that fruits and vegetables cannot be micro-chipped and bar coding on rough-skinned vegetables is difficult. Driven by the processing

industry, traceability, at the outset, seems to add more load to a grower’s already busy schedule, but some growers are finding the additional data collection is assisting them in managing the crop.

Traceability is a multi-layered issue and can remind growers what was done in a field to assist in resistance management and crop rotation. It can be used to reassure consumers that the food is safe. In addition, the information can be used to track stewardship and ensure environmental protection. “Traceability is partly a quality issue, but it is also being used to inform the public that processors and retailers are buying locally by allowing us to track where food comes from,” explains Dr. David Sparling of the Richard Ivey School of Business at the University of Western Ontario in London. “There is also a growing pressure to be able to measure and track the impact on the environment, such as reduced pesticide use or water conservation.”

Many processors are driving the issue because they want to know how sustainable their respective growers are and pass the information on to retailers and consumers, he adds. “It sounds daunting, but we are seeing that when growers start taking stock of what they do, they are also finding ways to improve,” Sparling continues.

In Manitoba, the largest vegetable supplier, Peak of the Market, has

The demand for the means to trace food back, from grocery store or restaurant, all the way back to the field, is growing.

Photos by RalPh PeaRce

A highly water-soluble source of granular micronutrients and secondary nutrients with application rates that maximize coverage for all your crops.

UltraYield ® Micronutrients ensure maximum crop health through research supported agronomics.

Full Line Offering of High Water-Solubility and Low Analysis

NuBOR10

Copper 12

BroadMan20

EZ20

Bean Mix

Corn Mix

10% B, 10% Ca, 5% Mg, 3% S and 70% W/S

12% Cu, 6% Zn, 14% S and 65% W/S

20% Mn, 12% S and 65% W/S

20% Zn, 14% S and 70% W/S

20% Mn, 4% Zn, 1% B and 50% W/S

20% Zn, 4% Mn, 1% B, 1% Cu and 50% W/S

BusIness ManageMent

been tracing the products delivered to its Distribution Centre since 2003.

The co-operative’s president and chief executive officer Larry McIntosh, says the number one issue with consumers is food safety. Traceability can help reassure them the food is safe, he says, because, should problems arise, they can be identified and dealt with quickly. “We can isolate the problem and track the exact lot,” explains McIntosh. “If the problem is with one grower, we can isolate that shipment.”

The chair of Peak of the Market, and a potato grower, says part of the issue is that most Canadians no longer have a connection to the farm and this leads them to be suspicious of their food supply. “We have to reassure consumers their food is safe,” says Keith Kuhl of Winkler, Manitoba. “If there is an issue with any of the products we sell and the person still has the package the potatoes came in, we can trace those potatoes to the field in which they were grown.”

That level of information tracking also has benefits to growers. Shelbourne, Ontario, grower Scott Rutledge, says he can trace a bag of potatoes back to his storage and from there to where and when he “put it in the ground.” He says having the tracing information also helps him with his crop management.

“If there is a problem, you want to find it right away,” Rutledge says. “It might be that it can be traced to a mechanical problem with the equipment or it might trace back to the seed supplier. Maybe the real issue is liability, so growers need to keep good records for their own protection. Since farmers tend to be the first guy on the list, we need to be able to find answers.”

The information in his computerized traceability program is good to have, he continues, because he can track his management decisions as well and make adjustments if necessary. He says he has records going back five years which give him a picture of what worked and what did not.

Dr. Sparling says the information stored and then analyzed can actually assist growers. “I think there are many growers who don’t spend as much time analyzing their costs and value as they could,” he comments. “But, hopefully, when they begin, they will see the electronic trail will give them quick access to information to improve their

Long thought to be more of an issue for livestock, traceability will soon cover all field crops, including potatoes.

processes and profitability.”

Currently, bags of potatoes can be bar coded and, with that code, the origin of the bag can be traced. But, the future lies in radio frequency identification (RFID) that allows for easier collection and sharing of information. “With RFID, analysis of individual fields is possible and that could save growers money, improve management and identify problems,” Sparling explains. “RFID coding can track the potatoes from field to storage and even record at what temperature the crop was stored.”

But, that is the future, and there are still gaps in the traceability system: for example, there are reports that warehouses that act as “middlemen” to store crops prior to shipping to processors, are not interested in traceability because, they feel it creates more work. Meanwhile, growers who are keeping track do not always have their information passed on to their processors. Most of the growers and experts believe the system is still evolving and that adoption will eventually arrive. “Traceability is a must, but if it becomes too complicated as more information is required, it might be harder to get compliance nationally,” worries McIntosh.

To lead the way and help growers get involved in traceability, OnTrace Agri-Food Traceability was formed in Guelph. This not-for-profit corporation helps growers understand traceability and assists them in developing systems for their operation. “There is a minimum amount of information required to track a product,” explains Brian Sterling, OnTrace’s chief executive officer. “It gets more complicated when you want to include more information, such as saying the potatoes are pesticide free or organic.”

He says 25 percent of Ontario growers are voluntarily registering their farms with OnTrace as part of traceability, but the government would like 100 percent compliance. He does not believe a voluntary system will ever reach 100 percent, so growers and packers need to address this as an industry and determine the approach they can accept.

“This is not going to go away. OnTrace is building a system that connects producers with shippers and warehouses; in fact, we have the ability to link all systems together in what we call a secure ‘inter-party’ system,” explains Sterling. “Consumers want information about the source of their food, but the industry needs to determine what is needed and how to comply with this growing demand for information. It is no longer sufficient to have ‘one-up/one-down’ knowledge; the consumer is asking about the entire chain of events that brings food to their table.”

“Whenever a bar code is required, we’re prepared to do it,” says Rutledge. “We find that not all systems are ready for this, but it is coming and we’re set up to comply. Right now, it is helping us to be better at what we do.”

“It may take time to determine what will work best for the potato industry,” Sparling comments. “This isn’t a new concept; it is done in other industries, but it has to be adapted to agriculture. Likely an industry-wide solution will be found and then that system will be tailored to individual crops. Growers should get involved now in setting the standards for what will work best for potatoes.”

Although individual growers are taking the initiative to set up traceability systems, and some processors and packers are demanding a system, and governments are asking for it, the real push for compliance may come from outside Canada as our international customers begin to demand traceability. When that happens, it may be imperative for a national system to be developed. Grower organizations may want to begin now educating their membership and developing strategies and researching systems in order to be ready. There may come a day when a bag of potato chips sold in Florida may need to be traced to a farm in Canada. n

Pests and dIseases

Common scab solution

by Treena Hein

Harnessing

the power of other bacteria to control the disease.

Among all the diseases that can reduce quality and result in economic losses for potato growers, common scab is one of the most difficult to control. Scab’s telltale brown lesions are caused by infection of a soil-inhabiting bacterium named Streptomyces scabies, and once in a grower’s fields, there is not much that can be done. No chemical control methods are available in Canada and fumigation is toxic and expensive.

Many avenues of control have been explored, and the study of one of the most promising is being spearheaded by Dr. Claudia Goyer, a molecular bacteriologist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC’s) Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Assisting Goyer are molecular biology technicians Sean Whitney and Jan Zeng.

Goyer’s work involves harnessing the ability of soil bacteria to produce molecules that inhibit the growth of other pathogenic bacteria such as S. scabies . The eventual goal is to produce a biopesticide, a biologically based product that controls disease while reducing risk for the environment and human health in comparison with conventional pesticides. Biopesticides are generally more targeted, effective in small quantities and have a higher rate of decomposition.

To Goyer, looking to the soil for a common scab control method is a no-brainer. “It’s well-known that soil is a warfare zone where bacteria use a variety of strategies to compete with each other,” she says.

Goyer and her colleagues have found the majority of soil bacteria able to inhibit the growth of S. scabies are of the genus Bacillus. “This is good news, because with them, it’s fairly easy to make an effective biopesticide,” she says. “They’re easy to grow and they produce spores that resist adverse conditions like heat, cold and dehydration.”

This means biopesticides from Bacillus bacteria can be stored and transported without much difficulty. In addition, the hardy nature of spores means the bacteria has an improved chance of establishing good population numbers in a field after it has been applied.

Bacteria in the Bacillus genus are not the only ones that have been studied to produce commercial biopesticides. Pseudomonas, Agrobacterium, and Streptomyces species have also been used. “The most renowned biopesticide features Bacillus thuringiensis, a bacterium that produces a protein toxic to insects,” says Goyer.

Step by step

The team begins the process by isolating bacteria from field soil. To do this, they add a solution and shake vigorously. The soil bacteria are then put into competition with a large quantity of common scab pathogen on solid growth medium plates, explains Goyer. “In these conditions, only bacterium that can produce molecules that can stop the growth of

A common sight for most growers, common scab’s most severe symptoms are deep-pitted lesions.

common scab will survive and multiply. They’ll form a colony you can see easily on the plate.”

That is the fairly quick part; purifying, characterizing and identifying inhibiting bacteria takes much longer, but they are crucial steps in ensuring the bacteria isolated present low risks to human health. After this is finished, the researchers then test different formulations of bacteria to see if this increases the control of common scab, and conduct further studies in the greenhouse and field.

So far, greenhouse tests with Bacillus isolates (grown in liquid culture and applied as a seed treatment on potato tubers at planting time) have provided outstanding results. “We’ve seen a 60 percent reduction in the severity of scab,” says Goyer. “This indicates that the Bacillus isolates were decreasing the severity of common scab probably by reducing the number of common scab bacteria in the soil.”

In the field trials to come in 2011 and 2012, however, Goyer expects a reduction of only 30 to 40 percent in the severity of common scab because the conditions will be harsher compared to those in a greenhouse.

Although Goyer has chosen to test seedcoating, there are other ways biopesticides can be delivered, including wettable powders, dusts and liquids. They have differing shelf lives,

Pests and dIseases

and offer differing success in terms of the bacteria multiplying and surviving in the environment, thus controlling the target disease. They also differ in terms of ease of preparation, ease of application and overall expense. The choice to go with one or another also depends on what part of the plant will be treated, where and when the pathogen grows and infects, and the grower’s particular cropping system. “After careful consideration, we decided the best time to introduce Bacillus -based biopesticides against common scab would be at planting as a tuber seedcoating,” says Goyer.

According to Dr. Claudia Goyer, with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, work with Bacillus isolates has shown the greatest potential for reducing the severity of common scab.

Introducing Bacillus at planting also allows the bacteria to colonize the tuber, the developing roots and the stolons, outcompeting S. scabies and preventing its growth. In addition, if it is possible to mix it with other products also applied as a seedcoating, this would allow growers to introduce the bacteria in a convenient and cost-effective way. The greatest challenge in this research is the fact that it is all about delivering a biologically based product, says Goyer. “It’s fundamentally different than chemical products because its living nature is what must be preserved and nurtured as it’s integrated as a regular strategy to control disease.” n

Plant BreedIng

Now arriving: a new white for table and fries

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Lower input requirements could help Tebina take the North American market by storm.

For the first time in many years there is a promising new white variety for growers to consider.

Developed by a Belgian family with both a trade and breeding business, Tebina wowed growers at potato field days in Ontario in 2010. According to the breeder, this is the first variety the company has developed that would fit into the North American market and offer some exciting traits for growers. “This is the first time we have developed a good white potato that could meet the needs of the North American market,” explains Francis Binst of Binst Breeding and Selection. “North Americans like white potatoes and Tebina is a bright white that should please growers and consumers.”

From a management standpoint, the variety has some appealing characteristics. “Tebina requires less nitrogen levels,” explains Binst. “It’s a late variety that is good both mashed and baked with 21 percent dry matter.”

Despite the lower nitrogen requirements, a Tebina plant still puts out a pile of potatoes with approximately 17 tubers per plant. Binst says, without any irrigation, growers were growing 40 tons per acre in Europe. This was verified and approved by an official bailiff, an individual who verifies yields in Belgium, in October 2007, he adds.

“The main feature we see Tebina offering growers is the large yield without an increase on the input side, so a net result will be more saleable units per acre without any increase in the cost of production,” adds Don Northcott of Real Potatoes Ltd., the Prince Edward Island distributor of Tebina. “We believe this variety will fill a niche where growers need to hit a lower price point and still make an acceptable return per acre.”

The lower nitrogen requirements may please many growers, but the trick to successfully growing Tebina is in the management. Binst admits work is still being done to perfect the management recommendations to allow growers to get a consistent size and yield. It is all due to the fertility. Binst says reducing the nitrogen levels will keep Tebina tubers at a reasonable size. If nitrogen levels are high in a field, Tebina just keeps growing and the tubers can become extremely large. “Certainly, you can get a high yield if you just let Tebina grow,” concedes Binst.

However, he adds that the size of the tubers might not be what is desired. He suggests growers have a clear idea of what they intend to do with Tebina and then manage the crop accordingly. “Experiment with the planting distance and start with half to 60 percent of the nitrogen you need and add more if you want to increase the size of the tubers.”

Northcott says Tebina will process out of the field for French fries and it is an excellent variety for general purpose cooking applications. For growers, knowing where you intend to market Tebina may play a role in managing its growth. “The variety can be used for multiple applications,” he adds, which gives growers some options.

Tebina has been grown in Europe since 2004 and Real Potatoes expects to have seed available for the Canadian market in 2011. “We will have sample volumes of seed available for commercial trials, so growers should contact us to secure sample totes,” Northcott says.

“Sometimes you look for something that is unique in the potato market,” Binst explains. “We think that having a high yield with Tebina is what we have to offer.”

That, and the fact that it might be possible to grow a nice white potato with half the nitrogen and still get that yield. n

You have always been able to count on DuPont for high-performing fungicides, herbicides and insecticides, in-field service and agronomic support. Now, you can maximize your crop protection savings and value with our unique FarmCare® Horticultural Program.

This year, with every unit of eligible DuPont product purchased, you’ll receive points that can be redeemed for cash rebates at the end of the season. The more you purchase – the more you save. It’s our way of saying ‘thank you’ for growing with DuPont! Get everything you can out of your crops, and everything you can for your dollar. DuPont™ FarmCare® Horticultural Program – for your crops, for your business, for your benefit.