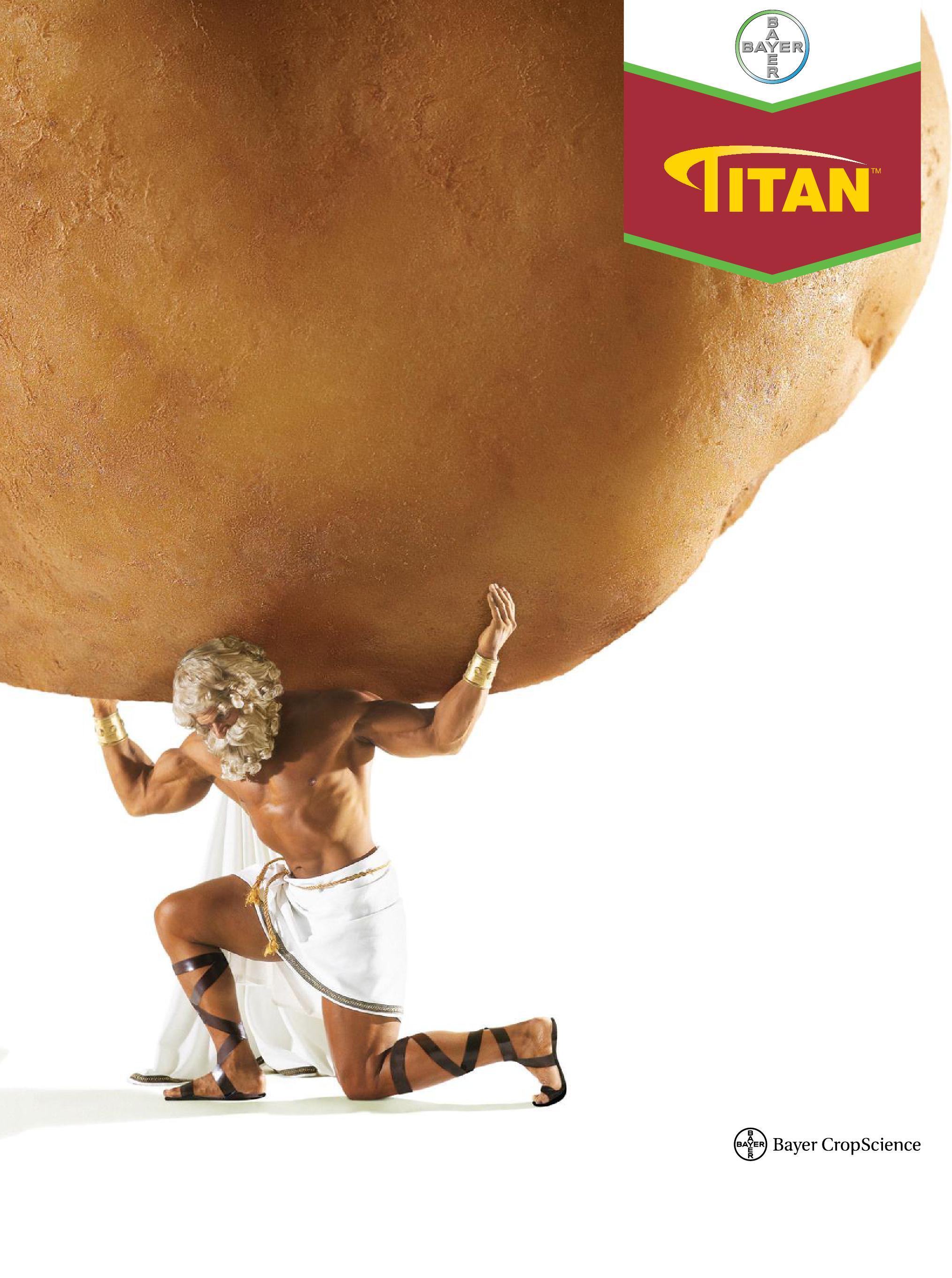

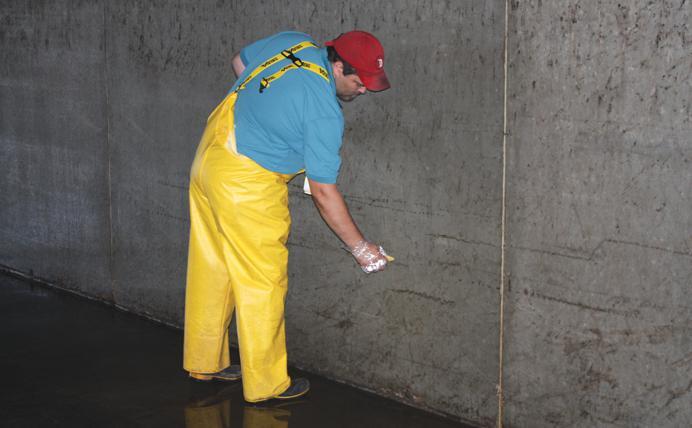

TitanTM seed-piece treatment gives potatoes the strength to produce healthier plants and higher quality yields. Titan controls all of the major above-ground pests: Colorado potato beetle, leafhopper, aphids and flea beetle and reduces the damage caused by wireworm.

Lighten the load on your crop with the strength of Titan – the broadest spectrum seed-piece insecticide for potatoes.

New varieties and new uses for potatoes are just a couple of the issues we cover in this year’s edition of Potatoes in Canada.

Late blight and controlling wireworms are two ongoing challenges for growers, and both have long-term management strategies that are in development.

It’s a fact: potatoes need irrigation, so we provide a look at irrigation systems in our annual Machinery Manager feature.

February 2011, Vol. 37, No. 2

EDITOR

Ralph Pearce • 519.280.0086 rpearce@annexweb.com

CONTRIBuTORS

Bruce Barker

John Dietz

Treena Hein

Carolyn King

Rosalie I. Tennison

EASTERN SALES MANAGER

Steve McCabe • 519.400.0332 smccabe@annexweb.com

WESTERN SALES MANAGER

Kevin Yaworsky • 403.304.9822 kyaworsky@annexweb.com

SALES ASSISTANT

Mary Burnie • 519.429.5175 mburnie@annexweb.com

PRODuCTION ARTIST

Kelli Kramer kkramer@annexweb.com

GROuP PuBLISHER

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 RETURNUNDELIVERABLECANADIANADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT.

P.O. BOx 530, SIMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 0705-3878

CIRCuLATION

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 211

Fax: 877.624.1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SuBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West - 8 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, October, November and December - 1 Year - $44.25 Cdn. plus tax.

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, August, October, November and December - 1 Year - $44.25 Cdn. plus tax.

Specialty Edition - Potatoes in CanadaFebruary - 1 Year - $8.57 Cdn. plus tax.

All of the above - $76.19 Cdn. plus tax.

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written

How can anyone not like potatoes?

Whether they’re mashed, pan-fried, French-fried, home-fried, riced, boiled, baked, roasted, hashbrowned or prepared in one of a dozen other methods I haven’t mentioned, this import from South America is a culinary delight.

When I look at the cover of this year’s issue of Potatoes in Canada, I see the smiling countenance of Jeroen Bakker, a potato breeder with HZPC Holland B.V., who, in our story on new varieties on page 18, states he knew he wanted to be a potato breeder when he was 12 years old. I’m certain that if I were to do a quick survey of potato growers on the Island, in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Alberta or Ontario, I would find a similar level of enthusiasm.

Similarly, there are researchers working diligently to protect potatoes from a legion of weed and pest species and disease pathogens. Like breeders and growers, they believe in what they do and derive satisfaction from the tangible results of their work.

Message not getting through

If you have read our other issues of Top Crop Manager or browsed through our website blogs, you know I am not an avid supporter of the mainstream media. Why? Because they lie (either intentionally or by omission) or misrepresent or ignore the edicts of accuracy and integrity. Their message often is muddled because of the chase for headlines, the battle for market share and the need to “get the story ‘out there’.”

I’m reminded of an instance when a researcher was talking to a large-city reporter. The scribe was attempting to get the “real story” on glycemic index in potatoes. The researcher was trying to explain that, to a degree, the glycemic index in potatoes depends on the preparation method. Halfway through the explanation, the reporter, obviously

suffering from a short attention span, cut in, asking, “Can we just say that potatoes are bad for people?”

As long as the media fail to get the “real story” straight – and this can apply to electric cars and literacy rates, as much as it does to potatoes – then the “real story” on new varieties, new uses for potatoes and, hopefully, new markets for potatoes, will be a tough sell. It will be left to growers, breeders, researchers and farm writers who believe in the sector and want to do as much as possible to help spread the word.

Pushing water uphill

A recent survey by Ipsos-Reid determined that the majority of Canadians trust farmers, yet understand little about farming. When I heard that, I thought, “Great! People want more information about agriculture!”

But the survey also found that most Canadians get most of what they know about farming from the mainstream media and the Internet.

That’s starving for information without knowing where to shop.

You can grow it, breeders can provide it, researchers can protect it and we can present all of the details for you.

But who tells the rest of the world the good news?

EDITOR Ralph Pearce

Track your potato production with Field Manager PRO

Order now and you could winan Arctic Cat ATV* *Contest details at www fccsoftware ca/dyff

Your customers want products that are traceable With Field Manager PRO, you can track your inputs, costs and activities Increase the marketability of your potato crop and get a complete picture of your production and field records. Field Manager PRO includes desktop and mobile software

by Rosalie I. Tennison

The Canadian potato breeding system is either in dire straits or highly successful.

Potatoes are a complicated crop and breeding new varieties is equally complex. Very few varieties have stood the test of time as consumer taste changes, disease pressure evolves, and breeders are challenged to meet the needs of growers and the markets they serve.

Traditionally, in Canada, public breeding programs served the growers, but as large processors began demanding certain qualities in the potatoes for their products, breeding also became the domain of private concerns. Large private breeding companies, mostly located in Europe, breed for all levels of the market from table stock to processing, but there is also a “cottage” style breeding system that sees individuals breed varieties that are licensed to the larger companies. Canadian grower organizations include promising varieties from the Europeanbased seed companies in trials to check their adaptability for Canadian growing conditions. But, also included in these trials are the varieties developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), the only remaining public breeder in the country as most universities have scaled back or shifted their focus away from potato research. So, where does this leave growers and what is the state of potato breeding in Canada?

According to Dr. Michele Konschuh, a potato research scientist with Alberta Agriculture, and Rural Development (AARD) in Brooks, changes were made to the public breeding system recently without much consultation with industry. “We tried to keep a breeder in Western Canada, but a different decision was made,” she explains. As a result, AAFC has only one potato breeder, Dr. Benoit Bizimungo, and he is now based in Eastern Canada.

Then, the Accelerated Release Program that had been introduced in Eastern Canada was expanded to Western Canada to allow access to promising seedlings. Konschuh says, in the end, the cost of evaluating promising varieties has been downloaded to industry. She

Photos by RalPh PeaRce

says the program does work for larger companies, but smaller companies cannot afford the cost of developing and marketing the variety.

But, at AAFC in Lethbridge, Dr. Jeff Stewart, the science director for the Lethbridge Research Centre and the person who oversees germplasm enhancement for AAFC at the national level, says the public potato breeding program is alive and well, just reorganized. He also says the Accelerated Release Program has helped stakeholders gain access to promising seedlings sooner than would have been possible under the former system. “Consolidation was necessary in various regions of Canada and it made sense to have a potato breeder at the Potato Research Centre in Fredericton,” Stewart explains. “Fredericton is our centre of excellence for potato research and there is a critical mass of expertise working on potato-related questions there. Bizimungo came from Western Canada and moved to Eastern Canada, so he has a national outlook.”

Stewart adds that AAFC maintains potato research plots in seven provinces where potatoes are grown, so there is attention to what is needed in each growing area.

The focus of the public and private breeding programs may be slightly different even though both are trying to develop germplasm with good traits that growers can produce successfully. Processing companies tend to focus on breeding varieties that will work for the products they produce, whereas public

breeders may be focusing on traits that will work for all types of potatoes. As Stewart says: “We tend to breed for the ‘public good,’ such as lowering the glycemic index.”

In the private breeding category, there are also individuals who breed potatoes. Although individual breeders are common in Europe, Canada can only claim about three, who essentially are trying to develop varieties “for the love of it.”

“Breeding is a lot of work and costs money,” admits John Konst, a potato breeder and seed grower near Outlook, Saskatchewan. “I don’t have access to testing sites or financial support, but I still have to abide by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada rules. Private breeders don’t have free access to parent plants to allow us to breed for disease resistance, for example.”

He says it is difficult for him to maintain his breeding program without some financial support, so his seed farm supports his breeding efforts, but he has to keep the two separated physically to ensure the purity of his seed.

Another private breeder is Dr. Robert Coffin, recently retired from Cavendish Farms on Prince Edward Island, and his experience as a breeder confirms that it is a costly business. “You work for years without any guarantees of success,” he says, “so you must always maintain your enthusiasm.”

If a private, individual breeder is able to develop a variety with scab resistance,

for example, that variety may never get to growers’ fields because the cost of registration and variety protection may be more than a single breeder can afford, he explains. “The weak link in the system is that a variety with a lot of potential may never get its chance in the marketplace because it costs so much to get it there,” Dr. Coffin continues. He says the European model has private breeders who pair up with large companies, which gives them access to facilities and financing to increase seed and develop their successes.

One of the concerns about the Accelerated Release Program is that not all promising seedlings get picked up by companies for further evaluation. Konschuh says that breeding is not everything because varieties have to be evaluated for adaptability. “Selection is

A breeding network that works

Ultimately, the end result of any research, public or private, must result in successful production for the grower and value to the consumer.

maybe more important than breeding,” she says. “We have some fabulous breeding programs, but it is the devel-

To promote the advantages and characteristics of the new tri-state varieties and help ensure the needs of growers are met through breeding program efforts, the Potato Variety Management Institute (PVMI) was formed. PVMI is also responsible for the administration of licenses and royalty collection that returns funds to the research program to ensure its continuation. The tri-states comprise Oregon, Washington and Idaho, whose potato research teams work together to share information and research focus to ensure that what needs to be done leads to the success of the regional breeding program. “PVMI is the brainchild of the tri-state commissions who have supported tri-state breeding programs for more than 26 years now,” explains Jeanne Debons, the organization’s executive director.

Each state has researchers who work together on the 15-plus-year process that it takes to bring a new variety to market. Idaho and Washington have potato breeders working to create successful crosses that meet industry requirements. Idaho is also responsible for selection field trials and agronomic management studies. Oregon manages selection trials and increases seed required in the program. Washington conducts post-harvest research, agronomic management trials and tests for usage. “The tri-state program breeds and evolves varieties for local conditions,” continues Debons. “So, if a variety doesn’t set a reasonably high amount of well-formed, defect-free tubers or doesn’t make it through the conditions of the Pacific Northwest, it isn’t kept in the trials.”

She adds that once the lines are advanced to the tri-state trials, growers are kept informed about each variety at annual meetings and through yearly Yield and Postharvest Quality Evaluations printed by Washington State University.

PVMI is a non-profit organization that does its best to keep industry, including growers, processors and shippers, informed about its varieties and new releases (two or three each year) through grower meetings, newsletters and the Institute’s website (www.pvmi.org). There is also a liaison between growers and seed producers to ensure there is enough seed supply and to help growers find seed if there is none available in their area. “It would be good if we could work with Canada because some of our varieties probably will perform well in Canada,” Debons says. “Tri-state growers have been encouraging and supportive of PVMI for the extra communications and information about the cultivars and what is happening in research. PVMI is hoping to be the glue that helps to hold the whole system together.”

The PVMI model shows how a non-profit organization can help aid communication and share information through one point, and at the same time, provide a source of funding for the future of the program. In this way, any breakthrough, whether public or private, is shared with the industry. It is a multi-faceted system that is efficient and successful. n

opment of the varieties that is lacking.”

“Growers don’t always get access to all the potential varieties,” adds Konst. “I don’t think the current system benefits growers.”

Coffin says his experience with the Accelerated Release Program was not all that successful, as the seedlings he chose to evaluate did not make it past the two-year evaluation period. Problems were identified in the seedlings, such as cracked tubers, extensive sunburn and hollow heart, all of which would lead to extensive dockage to the producer and a corresponding lower pay yield. But, he wonders, were there other potential varieties overlooked that could have been better? He believes there is not enough data provided by AAFC to allow evaluators to make good decisions on the seedlings they want to examine.

Stewart says the varieties developed by AAFC are showcased for growers and industry to give them an idea of what the public breeder is working on. “I’d like to think we have a complete effort in terms of meeting the needs of the industry,” he says. “We do rotational work, broad breeding programs and, if we don’t have what we need, we partner with another organization. You need a good infrastructure to work with potatoes and we have that because we are over 100 years old and have developed a system to work with potatoes in that time.”

Whether public or private, the majority of the needs of growers are being met, for the most part. There may be some glitches in the system in terms of technology transfer, and perhaps even a lack of bodies to do the work, but all the researchers involved in potato breeding programs seem to be working hard to develop the varieties that farmers can grow successfully. n

by Carolyn King

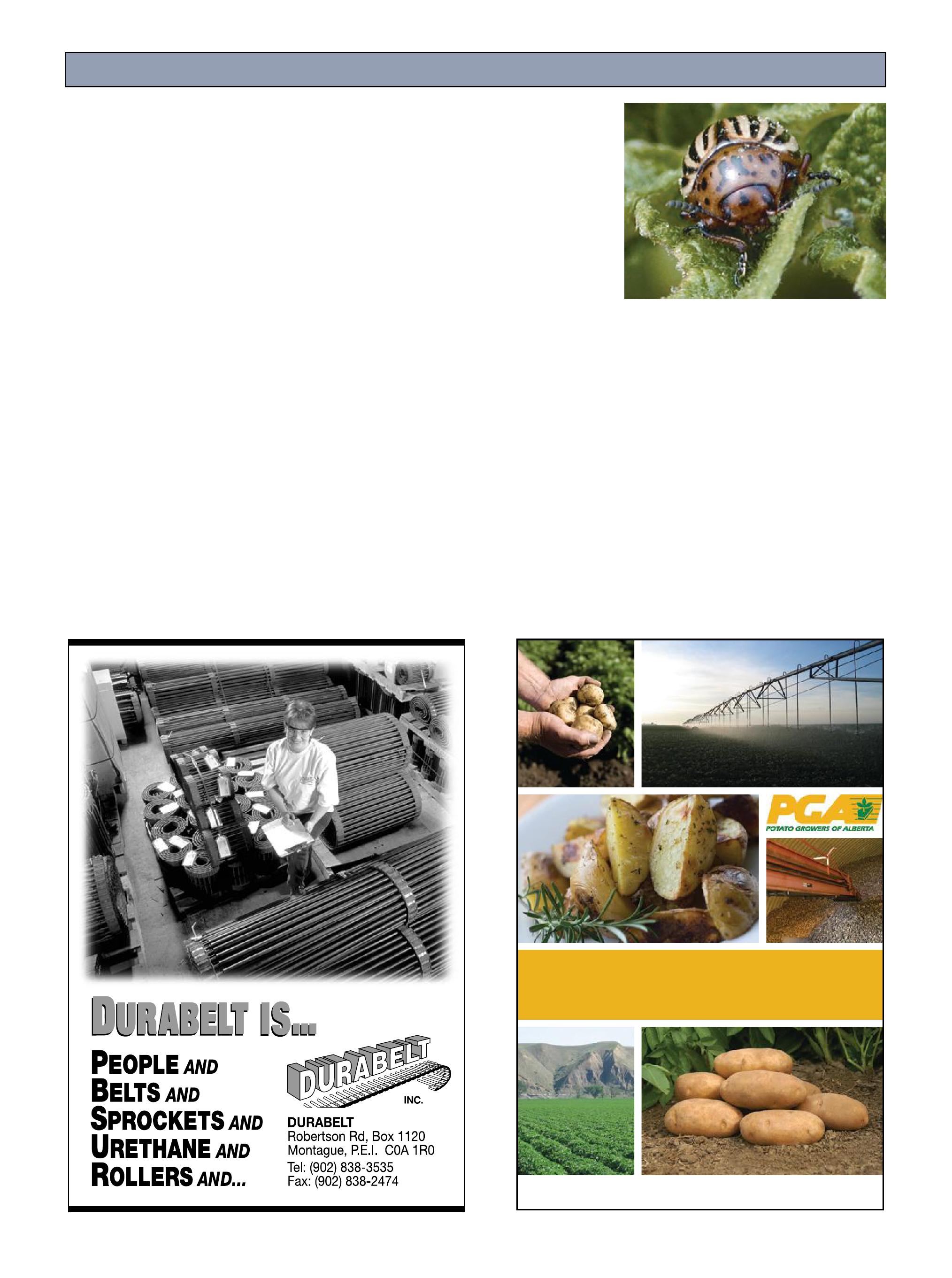

Bacterial ring rot is one of the most difficult infectious potato diseases to combat. Growers rely on sanitation of potato storages and equipment for prevention. With advances in microbial science, new sanitation products and better testing technologies, now is an opportune time to update and improve Canadian sanitation strategies and tools for ring rot control. So a leading-edge project is doing that, and more. “Bacterial ring rot is probably the most feared potato disease, especially for seed growers. There is a zero tolerance for it in seed potato farms. As little as one infected tuber on a farm will result in complete decertification of the farm unit. So finding bacterial ring rot on a seed potato farm would have devastating consequences, putting the operation out of seed production for two or more years until the producer is able to clean up and demonstrate that the infection has been eradicated,” says Dr. Ron Howard, a plant pathologist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (AARD), who is leading the project.

The disease can also be a very serious problem in commercial production of table stock and processing potatoes. It causes tuber rot and reduced yields, and can spread easily from field to field, from the farm to the potato processing plant, and from there to other farms on contaminated potato equipment and vehicles such as trucks.

A major component of Howard’s project is to test the effectiveness of existing and newly identified disinfectants on the ring rot pathogen. In Canada at present, there are two licensed disinfectants that can be used for potato storages and equipment: General Storage Disinfectant and 1-Stroke Environ. “The General Storage Disinfectant has been used for many years, and the 1-Stroke Environ is a more recently introduced product. Growers have asked whether these products are still effective on the ring rot organism, given reports that you hear about plant disease organisms building up resistances, or tolerances to

Using this mobile sanitation unit, researchers are conducting pilot-scale evaluations of the sanitizing procedures in commercial facilities, like this potato storage unit at Broderick, Saskatchewan.

products. And naturally, growers are always on the look-out for products that might be more effective than the older existing products,” says Howard.

He adds, “I’m hoping we’ll end up with more products being registered for use against ring rot as disinfectants. I think there are other products as effective or maybe more effective than the two we have now. The data that we are amassing as part of this project could help support registration of those products, and we would encourage the manufacturers to register them if their efficacy is superior.”

In the past, disinfectant effectiveness was tested only on the single-cell forms of microbes. Howard’s project involves a significant step forward because it is testing the products on both the singlecell and “biofilm” forms of the ring rot bacterium, Clavibacter michiganensis subspecies (sp.) sepedonicus

He explains, “Biofilms are communities of microbes that grow attached to surfaces and are bound together by a slimy matrix. This matrix protects the microbial cells from exposure to disinfectants and antibiotics. As well, the microbial cells in the biofilm have differences in gene expression and physiology, as compared to the non-attached, single-cell, or “planktonic” form of the

microbe. Consequently, biofilms can be up to 10,000 times more resistant to disinfectants than single-celled populations.”

Howard’s research team includes experts from Innovotech Inc., an Albertabased company that has developed advanced technology to rapidly assess the effects of biocides on biofilms. Other team members include Dr. Tracy Shinners-Carnelley, a potato specialist from Manitoba, and Dr. Solke De Boer, a bacterial ring rot specialist from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Federal and provincial agencies and a number of potato organizations are funding the national project.

Along with the disinfectant testing, the researchers are examining how the disinfectants fit into an overall sanitizing strategy for ring rot. A key aspect of this involves assessing disinfectant performance on different types of surface materials, because the surface material can influence both bacterial growth and disinfectant effectiveness.

Potato storages and handling equipment can involve many types of materials such as concrete, unpainted and painted steel, aluminum, galvanized steel, rubber, wood, spray-on foam insulation and sponge foam insulation. Howard says, “All of these surfaces

The industry’s best selling hydraulic steering system is now available for any model swather. The all-new eDrive VSi™ is the ideal steering solution for AGCO, Challenger, Hesston, Massey Ferguson, CASE, New Holland, John Deere, MacDon, Premier, Prairie Star, Westward and Harvest Pro swathers.

• Fast and accurate steering response

• Transfers easily between vehicles

• Proven eDriveTC™ reliability and performance

• Silent in-cab operation

• Easy, clean installation

Simply let go, and let the eDrive VSi™ take the stress out of your workday. For information, visit us at www.OutbackGuidance.com or call us at 866-888-4472.

Photo couRtesy of albeRta agRicultuRe and RuRal develoPment

could potentially become contaminated with bacterial ring rot if you had a serious outbreak and a lot of breakdown in storage. So we’ve taken those materials, contaminated them with ring rot biofilms, and exposed them to different disinfectants at various concentrations for various lengths of time.”

The researchers are also evaluating disinfectant corrosiveness on surfaces, safety issues like protective equipment for applicators and the value of adding products like foaming agents to disinfectant mixtures.

In addition to the lab testing, the

researchers are using a mobile sanitation unit to conduct pilot-scale evaluations in commercial facilities to ensure the procedures work in real-life settings. Because bacterial ring rot is rare, the researchers have not come across a storage facility with a ring rot issue. So, the on-site tests are measuring the total microbial load – bacteria, yeast and fungi – in the storages before and after the treatments. In 2010, on-site testing was conducted at 10 commercial storages in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and that work will continue in 2011.

The project has already generated several important results, and Howard hopes to have improved national guidelines for growers within a year.

Three-step cleaning process confirmed as best approach

“Probably our most significant finding is that the sanitation process really does have to follow three key steps, and you can’t skip any step and hope to do a good job of disinfecting surfaces or equipment,” says Howard. He adds, “This three-step strategy is not new. Most growers are already doing that, but we now have the experience and the data to support that strategy through our studies.”

Step 1 is rough cleaning. This involves sweeping and scraping up debris, like tubers that have been squashed or rolled into corners, pieces of potato vines, and soil.

Step 2 is pressure washing. He says, “Pressure washing removes any residual organic material, such as soil and crop debris, and it also begins to blast away at the biofilms of pathogens like ring rot that may be left behind on the floors, walls, plenums, grates and drains. Pressure washing should be done with warm or hot water and a detergent. The detergent softens up the soil and the biofilms, and makes them more amenable to removal by pressure washing. We’re generally talking 2000 or 3000 pounds per square inch of pressure with warm or hot water to break up and flush away the remaining organic residues and soil.”

Step 3 is applying the disinfectant to the pressure-washed surface. It should kill any biofilms and planktonic cells remaining.

He emphasizes, “Steps 1 and 2 are the most critical because you can remove about 99 percent of the contamination by doing a good job with getting rid of the rough residue and biofilms by pressure washing. The disinfectant is just used to clean up any residual contamination.

“Many producers would like to skip Step 1 and Step 2 and just go in there with the disinfectant right off the bat. But we found that the disinfectants do not penetrate into the inside of contaminated stems or tubers or the slimy residues that may be left behind on surfaces. Also some of the disinfectants are neutralized by organic matter and lose their effectiveness.”

So, by leaving the disinfectant application to the last step, it minimizes the

amount of disinfectant needed, which reduces disinfectant costs. Furthermore, some disinfectants are hazardous, so minimizing the amount used reduces the exposure hazard to applicators, potential corrosion damage to surfaces, and potential downstream impacts of excess disinfectant runoff on drains, lagoons and sewer systems.

Choose the right disinfectant for the type of surface

A second important finding is that is no single disinfectant does a 100-percent job on all of the different types of surface materials that can be found in potato storage facilities. For example, some disinfectants work very well on certain surfaces and are weak on others.

Howard notes, “The two most difficult surfaces to disinfect that we’ve found are wood and foam insulation because they are very porous and take a special effort to disinfect. You need to thoroughly clean them, of course, but you also have to make sure you choose the right disinfectant for the job.”

At the end of this project, Howard expects to be able to provide information about the risks and advantages of each disinfectant so growers can make informed choices.

Cutting rates or contact times cuts effectiveness

“Not surprisingly, pretty much all of the disinfectants kill the ring rot organism in the planktonic form, but it is much more difficult to kill as a

biofilm,” notes Howard.

The project’s results show that lowering rates or contact times below those specified on the label can drastically reduce a disinfectant’s effectiveness. “In fact, against the biofilms we have often found that the label rates for general disinfection on many of these products will not eradicate the ring rot pathogen with short exposures of 10 or 20 minutes of contact time. You need to go either to a higher concentration or to a longer contact time,” he explains.

“As a general rule, with most of these products, we often have to go to twice the label rate or more to get a reasonable kill, and we need to extend the contact time sometimes up to 30 minutes. That means, after the surface has been cleaned and you’ve put your disinfectant on, you have to re-apply the disinfectant to make sure you get 30 continuous minutes of contact time between the disinfectant and the surface. Otherwise the disinfectant tends to run off or dry and there’s no further activity.”

The researchers are also developing recommendations for ensuring sufficient contact time. Howard says, “Those recommendations will include things such as applying disinfectants when air temperatures are cool versus warm or hot, and shutting down the doors and ventilation systems in storages to prevent the disinfectant from drying down too rapidly. If that’s not possible, then you may want to consider adding something like a foaming agent to your disinfectant to slow the dry-down.”

Beyond bacterial ring rot

The research methods and technologies used in this ring rot project have become a template for two similar projects. One project relates to controlling bacterial canker in greenhouse tomatoes. Howard says, “The bacterial canker organism is a close cousin of the bacterial ring rot pathogen, so we were able to do sort of a carbon-copy trial to look at methods to eradicate the tomato canker pathogen from the types of hard surfaces commonly found in commercial greenhouses.”

The other project involves clubroot, a serious canola disease that is mainly spread by contaminated equipment. “We’re looking at the efficacy of cleaning methods and disinfectants against the clubroot pathogen where spores contaminate surfaces of equipment and vehicles,” he explains.

As well, Howard is hoping to use the same research approach to evaluate the effects of the ring rot sanitizing procedures on other potato pathogens. The three-step sanitizing process is the best approach for any potato disease issue, but research is needed to determine the effects of the various disinfectants on the other pathogens.

It is quite possible that the ring rot sanitizing strategies will also control other potato pathogens at the same time. Many of the disinfectants used in the ring rot project are broad-spectrum biocides so they will likely kill various other bacterial and fungal pathogens. In addition, the ring rot procedures are aimed at virtually 100 percent eradication of Clavibacter michiganensis sp. sepedonicus, which is not necessary for most other potato pathogens.

Howard says, “We have set a very high standard for the cleaning and disinfection protocols being evaluated in this bacterial ring rot work. For other diseases, in most cases, growers would be satisfied if they were able to take the contamination level down to only one or two or five percent contamination left in the storage. But with bacterial ring rot, we need to take it down to zero because there is a zero tolerance for it in seed operations. And even in many commercial operations, growers treat it as though they want zero tolerance because of the stigma attached to the disease. So the disinfectants and the overall sanitation program have to be so robust as to totally eradicate the organism where at all possible.” n

QUICK INSECT KNOCKDOWN. WIDE RANGE OF CONTROL. LOW-IMPACT MODE OF ACTION.

Potato growers! DelegateTM WG insecticide is now registered for quick, broadspectrum, low-impact control of insects, including Colorado Potato Beetle and European Corn Borer. Only Delegate brings a higher level of performance to your potato business – using a novel mode of action that delivers quick knockdown of a wide range of problem pests with a low impact on beneficial insects. And all this with a considerably lower use rate. Accomplish more. With new Delegate for potatoes. Call our Solutions Center at 1.800.667.3852 or visit dowagro.ca today.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Just when growers figure they have a strategy for managing late blight, a new strain is identified.

Managing late blight is an ongoing challenge, but knowing which strain one is faced with controlling can go a long way in minimizing the frustration. There may not be many tools in the fungicide toolbox, but those that are there can be used more effectively if it is understood which strain is in the field. Unfortunately, just as growers reach that knowledge a new strain is identified. In 2010, a US-22 strain was identified in Michigan; thankfully, it did not reach Canada. However, it could, and then what will growers be left to do?

Until 2009, there was no clear national strategy on dealing with late blight, and information collected by one provincial agricultural department was not always shared with other provinces in a timely manner. It was also unknown if all Canadian potato-growing areas were dealing with the same strain. Reports would be filed that products were ineffective in one area, but worked in

A new tool for the toolbox

Photos couRtesy of dR Khalil al-mughRabi, new bRunswicK dePaRtment

another, and it was unknown if this was due to product failure or incorrect application or if, in fact, the strain of late blight in that area was resistant to the fungicide.

To minimize the confusion and to ensure all growing areas have the same information, Dr. Khalil Al-Mughrabi, a pathologist with the Department of

With some late blight strains developing resistance to available products, and few new products being introduced, the announcement that phosphoric acid products to control late blight are now available is great news. Some growers have been using unregistered formulations of phosphoric acid and researchers have been working to determine how to use it most effectively. But now, a registered formulation for use in potatoes is being marketed in Canada under the name Confine. It is manufactured by Winfield Solutions of St. Paul, Minnesota, and marketed in Canada by the AgroMart Group, near Thorndale, Ontario.

A combination of mono- and di-potassium salts of phosphoric acid, Confine can be applied as a foliar spray, post-harvest to control pink rot, and as a soil drench. Research in New Brunswick on the effectiveness of each application recorded the following:

1. Foliar applications at higher rates provided excellent control of late blight and pink rot tuber disease, providing application was made prior to pathogen inoculation. Control was most effective when the product was applied five times. Further research is being conducted to determine the effectiveness of Confine when used as a tank mix for resistance management.

2. Application can be made as a “root drench,” which would be an effective disease management tool. Three applications via chemigation could provide good control.

3. Control of pink-rot post-harvest is effective if treatment is done before infection, preferably within six hours of harvest. It is not to be used on seed potatoes because it can hinder sprouting.

More work using phosphoric acid is planned, but the initial results in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island look very promising. n

of agRicultuRe, aquacultuRe and fisheRies

Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries in New Brunswick, proposed forming the National Potato Late Blight Working Group. The group would ensure the prevalent late blight strains would be identified in each area and determine which of the available products would offer effective control. “We wanted to get an idea of what late blight strains exist in Canada and develop a national screening program,” Al-Mughrabi explains. Until the organization of the working group, of which he is chair, he says there was overlap and repetition and very little information was shared because there was not a mechanism to do it. “Now, with a co-ordinated approach, we can develop a national picture of late blight in Canada.”

So, what about US-22? Is it a threat to Canadian potatoes? It could be because it is a mutation of US-8 and US-14 strains. The US-8 strain has been in Canada since 2006, but has been effectively controlled with fungicides. “In 2009, US-22 was more aggressive on tomatoes, but also affected US potato crops,” reports Dr. Eugenia Banks, potato specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “Fortunately, US-22 is susceptible to mefenoxam. Our most common strain, US-8, is resistant to mefenoxam, which has been a problem for growers.”

If there is an upside to having US-22 enter Canada, it could be that there are

some effective options for control. Banks says two other strains of late blight, US-23 and US-24, have been identified, with the latter prevalent in North Dakota, which could have an effect on the Manitoba crop. “It is important for growers to find out what strain is infecting their fields,” continues Banks.

It is the goal of the working group to identify the strains and then to keep growers informed so they can choose the best method of control. “We are developing fact sheets on late blight that will carry the same message to all growers in Canada. We had two research projects funded in 2010 to learn what products work on which strains,” Al-Mughrabi says. “We also want to develop an extension program that would allow presentations that everyone in the potato industry can access.”

A website is also planned that will keep current on the latest findings regarding late blight and it will include contact information for each province to give growers access to the late blight experts in their area. In addition, a YouTube video (http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=q1Xa4bJ_YnI) on Al-Mughrabi’s late blight management initiatives was started in Alberta to give growers more information about late blight. “The preliminary results at the end of 2009 showed that Manitoba has US-11 and US-6 while US-8 is most common in Quebec, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island,” Al-Mughrabi reports.

In 2010, he received samples of blight from across Canada with the goal to identify the predominant strains in each growing area. The strains are being identified by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientists in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island and Lethbridge, Alberta. Knowing the strain common to an area can go a long way in knowing what products to use for effective control. He says research on using phosphoric acid to control late blight is showing it is as close to a magic bullet as possible (see sidebar). “There is no one single strategy to control late blight,” admits Al-Mughrabi. “What you need is a combined approach using seed treatments and sprays. We also know that the speed of the sprayer can affect how well the product works. With phosphoric acid, while it is highly effective, it has to be applied at the right time in order for it to do a good job.”

Al-Mughrabi’s initiative to develop a national network of late blight experts who share information and then deliver it to growers may prove to be what is

needed to keep late blight in check consistently. With ready access to the latest information and knowledge of what strains are prevalent in each area, growers will not have to worry needlessly every time a new strain is reported south of the border. Instead, they will know which strains they are likely to face if conditions are right for late blight infections and they will know which products will effectively control that strain. They will also have all the information available to continue resis-

tance development minimization. With the 2011 growing season quickly approaching, growers can be confident that rumours of new strains of late blight entering Canada are already being researched by members of the National Potato Late Blight Working Group. And those members will, no doubt, have the strains identified in each region and control strategies to recommend before any of the late blight pathogens can become a yield-robbing problem. n

You need buildings for your farm that are easy to assemble and built to last. That’s where the BEHLEN Curvet comes in. With sizes ranging from 40’ to 68’ and constructed using 100 per cent steel roof and wall panels, our storage solutions are a perfect companion for your agricultural operation.

Features:

Easy to assemble and expand

Simple to follow construction and foundation details specific to each building

Precision manufactured

Galvanized and pre-painted options

Bolt-down, formed footing channel for easy connection

Wide range of building accessories

Proven airflow and ventilation performance

Structural steel interior and exterior fanhouses, plenums and catwalks

DuPontTM Coragen® insecticide puts you in control of your toughest insect pests. Coragen® is a highly effective insecticide that delivers extended residual control of key insect pests such as European corn borer and Colorado potato beetle. Plus, Coragen® belongs to a whole new class of chemistry and it has a novel mode of action -so you can even control pests that are resistant to other chemistries.

Field-proven under Canadian growing conditions, Coragen® is easy on beneficials and the environment, so it’s a good fit in IPM programs.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

2010 was a good year for introductions of exceptional new varieties.

It is not often that a new variety is so impressive that growers are asking when they can get seed. In 2010, there were a couple of varieties developed by a new generation of breeders who are continuing family traditions of growing and breeding with an eye to the future. One variety is Tebina, and the other is #30-2010, which became known as “Wow” in all the trials.

Developed by Jeroen D. Bakker of HZPC Holland B.V. in the Netherlands, #30 is a round, white-fleshed, scabresistant variety that growers cannot wait to have in their fields. Unfortunately, they will have to wait because Bakker says seed will not be widely available until 2015. “We will have mini tubers available in 2011,” he notes. “HZPC will make the investment in producing mini tubers because this clone looks so promising.”

Bakker says he knew he wanted to be a potato breeder when he was 12 years old, which is unusual as fewer and fewer agricultural students see the value or rewards in becoming breeders. Bakker is a member of a family of seed potato growers from the Netherlands and, therefore, working with the crop is seemingly in his blood. Developing #30 has only cemented his commitment to continue producing better varieties. “Last year (2009) we planted #30 in an area infected with scab and it performed well,” Bakker continues. “This year (2010) it was put into the scab trials and, again, it did well.”

“I would classify this one as resistant to scab, not tolerant,” says Dr. Eugenia Banks, potato specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “We have rated it as a ‘1’ on the scale.”

In 2010, #30 performed well in Ontario and North Carolina; in Ontario it was not grown under irrigation. Banks calls the variety “Wow” because it seems to have the entire package: it performs well in the field; is a nice, round white tuber with shallow eyes; matures early; has uniform size and good yield; and, yes, is scab resistant. “What’s not to like?” asks Banks. “It even washes well!”

ABove: Growers may want “Wow” soon, but Jeroen Bakker, breeder with HZPC Holland B.v., advises it will be 2015 before the variety is commercially available.

RiGHT: Ambra, another new variety from HZPC Holland B.v., has been called “the best yellow variety” by one grower, says Dr. eugenia Banks of oMAFRA.

Photos by Rosalie i tennison

HZPC also showcased Ambra, a yellow, early variety, in the trials in 2010. The variety was noticed in the 2009 trials and now, with another trial to its credit, it is starting to attract serious attention. Banks says Ambra is a high yielding, good-tasting variety that has medium tolerance to scab. “One grower told me Ambra is the best yellow variety he has ever grown,” she reports.

In the specialty varieties, Bakker showed off an orange-fleshed, red-skinned potato that he believes could fit into a niche market. However, the investment required to develop a niche market potato is high and Bakker would like to team up with a partner to offset the costs and assist with the marketing. “For example, a grower could partner with us to develop the variety and then have the rights to develop the market as well,” he says.

As a breeder, Bakker likes to visit Canada and see his varieties in the field.

He says that growers in this country are willing to try new varieties, which gives him confidence that what he is doing is making a difference. Of course, when someone keeps referring to an unnamed variety as “Wow,” it should boost grower confidence, as well. Bakker believes that what he and countless potato growers are doing is vital to the world because, if climate change is a reality, potatoes could become a major staple crop. In fact, potatoes could replace rice, which requires much more water to produce. Bakker is pleased to be part of an industry that could end up playing a vital role in the world food supply and he is committed to developing the varieties required to meet future needs. n

by Carolyn King

With the insecticide Thimet LNL scheduled to be de-registered in Canada in 2012, potato growers are wondering how they will manage wireworms in the future. “Wireworms injure potatoes by feeding on the seed piece, resulting in weak stands and yield reduction. However, the majority of their damage is caused by tunnelling into tubers, which reduces marketable yield. Wireworm tunnelling also creates an entry point for certain plant pathogens, eventually leading to tuber rot,” says Dr. Eugenia Banks, potato specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). She notes, “Wireworms are difficult to control because of their long life cycle, their mobility in soil and their wide host range.”

Wireworms are the larvae of click beetles. The beetle lays eggs in the spring and a few weeks later, the larvae hatch. In most wireworm species, the larval stage lasts four or five years. Then the insects pupate and emerge as adults. During the larval stage, wireworms live in the soil, feeding on the underground parts of plants. They are able to feed on many different types of crops, although potatoes are a particular favourite. “Their mobility in soil allows them to escape unfavourable conditions. Wireworms move up and down in the soil profile in response to changes in soil temperature and moisture. During the growing season, the wireworms move up into the top few inches during the spring when soil temperatures reach approximately 10 degrees C and remain there as long as temperatures remain near 26 degrees C. If temperatures exceed 26 or soil conditions become very dry, wireworms may burrow as deep as 60 centimetres (24 inches). In the fall, wireworms move down to escape freezing temperatures. Thus, winterkill is not very effective in reducing wireworm populations to low levels,” explains Banks.

Wireworms’ wide host range means that crop rotation is not usually an effective control method. So, insecticides are important for managing the

Damage by wireworms makes potatoes unmarketable.

insect. Given the long larval stage and the wireworm’s ability to temporarily avoid unfavourable conditions, the length of time an insecticide remains active is a significant factor in wireworm control.

“In the past, there were a number of chemicals for wireworm control in potatoes, but over time those products have been lost. Thimet LNL is basically the only crop protection insecticide that gives long-lasting wireworm control in potatoes,” explains Bob Hamilton of Engage Agro.

The company is the Canadian distributor and marketer of Thimet (phorate, an organophosphate), which is made by AMVAC International, the Canadian registrant.

Health Canada’s Pesticide Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) plans to phase out the sale and use of Thimet in 2012. Growers will be able to use it until August of that year. “Researchers across Canada are looking and have been looking extensively during the last several years for alternatives to Thimet, and still they have not found any insecticide that is as effective in controlling wireworms. Some products have been identified but they give a “suppression only” rating, which is not good enough,” notes Hamilton. If the wireworms are merely suppressed, they may recover enough to

do damage later in the growing season. Hamilton says, “We’re working with the PMRA to address the circumstances. Wireworm control is clearly a pressing issue. Our focus is on providing effective solutions to control this pest. At present, we are doing what we can to support Thimet LNL.”

The PMRA has extended Thimet’s registration several times in recent years because of the lack of effective alternatives for controlling wireworms in potatoes. One of the researchers looking for alternative control methods is Dr. Christine Noronha, an entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. She says, “I’m really worried for potato growers because if Thimet is taken off the market, as of now there really isn’t anything for our growers here on the Island.”

Even if a product is found fairly soon, it would still need to go through PMRA’s registration process to get on the market. Finding effective control options is an uphill battle, partly because of the wireworm’s subterranean habitat, making it difficult to know how it is responding to different treatments. In addition, research led by Dr. Bob Vernon at AAFC’s research station in Agassiz, British Columbia, shows insecticide effectiveness depends on the wireworm

species. That is a problem because there are 25 to 30 wireworm species in Canada that damage agricultural crops; the species vary from region to region and there can be more than one species in a single field.

Vernon and Noronha are assessing many of the newer insecticides, such as neo-nicotinoids and pyrethroids, as well as various combinations of these insecticides. The results so far indicate the newer insecticides tend to suppress rather than kill wireworms.

Noronha says the insecticides seem to perform better in BC than in PEI. “For us, nothing has given us control for the table stock market. Even with Thimet there is some damage; it’s not giving total control.” She explains, “If it’s a cold spring, then the larvae take their own sweet time to come up because the soil isn’t warm enough for them. The insecticide is used at planting, so if the larvae don’t come up and eat early in the season on those treated tubers or in the treated area, then by the end of the season, the insecticide is no longer working, and it can’t work because you don’t want insecticides on the potatoes you eat. So larvae that come up later don’t get the insecticide.”

She notes that wireworms often do feed later in the growing season because they need to build up their nutrient reserves to survive the winter.

Currently in Ontario, the wireworm situation in potatoes is not as bad as in PEI. Banks says, “Wireworms used to be a serious problem in Ontario, but their populations have decreased since around 2005. A quick survey indicated that close to one percent of the potato acreage in Ontario might have wireworm problems.”

She notes, “In Ontario, Dr. Jeff Tolman conducted research on wireworms. He evaluated the efficacy of clothianidin (a neo-nicotinoid) to control wireworms. It was not easy, and it is still not easy to find fields in Ontario with a high population of wireworms to conduct research.”

However, Banks cautions, “The potato pest complex is notorious for the sudden changes in their incidence and severity. Wireworms might not have been a major problem in Ontario during the last five years, but their incidence might increase in the near future.”

Although wireworms will feed on almost any crop, there are a few that they really do not like. So Noronha led a study to see if perhaps those crops might help in situations where Thimet alone does not provide complete wireworm control. The results were surprisingly good. She says, “I went out on a limb and said, ‘I wonder if it would work?’, and it worked so well!”

She compared the effects of four rotations on wireworm damage in potatoes. The rotations were brown mustard-brown mustardpotato, buckwheat-buckwheat-potato, alfalfa-alfalfa-potato, and barley-clover-potatoes. Thimet was applied in the third year.

Noronha chose brown mustard because it has one of the highest glucosinolate levels in the mustard family. When glucosinolates in the plant tissues break down, they release chemicals called isothiocyanates. The isothiocyanates act as a fumigant against insects, including wireworms, as well as many soil-borne bacterial and fungal diseases. In addition, brown mustard roots have another type of glucosinolate that is actually toxic to insects. “We chose buckwheat because growers were telling me that if they grew buckwheat the year before potatoes, they didn’t have a problem with wireworms in that field,” she explains.

Buckwheat is thought to contain compounds that repel insects and inhibit their feeding.

The researchers used alfalfa because it is a deep-rooted plant that uses a lot of water. Since wireworms prefer moist conditions, it

is possible they may not do well under alfalfa. Noronha notes, “We didn’t think alfalfa would work here because of our high rainfall, but we decided to test it.”

The barley-clover-potato rotation is the normal rotation used by PEI potato growers. The researchers followed the growers’ usual practice, which is to underseed clover to barley in Year 1. The barley was harvested in Year 1, and the clover in Year 2. Wireworms really like to feed on all three of these crops.

For the mustard rotation, in Year 1 the researchers let the mustard reach the flowering stage and then incorporated it into the soil. After about two weeks, they seeded another mustard crop. That second crop did not reach maturity and was simply left standing during the winter to provide soil erosion protection and an ongoing source of glucosinolates. In the spring of Year 2, the researchers incorporated those plants, and then they followed the same steps as in Year 1.

In the buckwheat rotation, they followed the same procedures as in the mustard rotation. For the alfalfa rotation, they managed the alfalfa the way growers normally manage the crop.

The researchers tested the four rotations in two fields, both of which had very high wireworm infestations. At the end of the third growing season, they examined the tubers from all the rotations.

The results for both fields showed the same patterns: wireworm damage in the tubers was lowest in the brown mustard rotation, followed by buckwheat. Noronha says, “We had about four and three holes per tuber in the buckwheat and the mustard, compared to 12 to 13 holes per tuber in the alfalfa and the barleyclover rotations. So there was a really dramatic difference in the number of holes.”

She adds, “We also had a lot of tubers with absolutely no holes at all in the mustard and the buckwheat rotations.”

For instance, more than 30 percent of the tubers were not damaged in the mustard rotation, compared to less than 10 percent of the tubers in the barley rotation. “For the processing market, if wireworm damage is not very deep, then they can just peel off the hole or the scar. But the table stock market cannot accept any damage because if there is any little hole, people don’t want to buy the potato. That’s why I’m excited about the results of the mustard rotation combined with the insecticide; if 30 percent of your tubers have absolutely no damage, that’s much better than having 90 percent damage.”

The researchers also assessed the economics of the different rotations. “We evaluated the tubers in the same way as the processing industry would, taking the culls out of the picture and then evaluating all the tubers and deciding marketability based on the damage levels. For the barley and the alfalfa rotations, only 55 and 56 percent of the crop was marketable for the processing industry, compared to about 80 percent for the buckwheat and mustard rotations,” says Noronha.

These impressive results have encouraged some local growers to try the mustard rotation, even though it requires a fair amount of work to grow two mustard crops per year.

The researchers also did a trial with one mustard crop per year, incorporating it during flowering and then just leaving bare soil until the following spring. The results followed the same trends as those for two mustard crops per year.

Unfortunately, simply applying mustard meal once a year does not have the same impact on wireworms as growing mustard. Noronha explains, “A lot of people have been trying mustard meals to control wireworms, but it hasn’t worked. I think that’s because mustard meal breaks down and releases isothiocyanate only once. If the wireworms are present at that time, they may be affected, but they can just move away and go deeper into the soil and then come back up later when there are no more isothiocyanates being produced. But if you grow the mustard crop over the year, the plants are constantly releasing isothiocyanates into the soil.”

Noronha will be conducting lab studies to get a better understanding of how brown mustard and buckwheat affect wireworms. She also thinks it would be useful to carry out the rotation study in other regions across the country to determine if the mustard and buckwheat rotations work as well with other wireworm species and in other soil and climate conditions. Also, she is hopeful that the mustard rotation could control wireworms in host crops other than potatoes, like carrots or rutabagas.

And as 2012 approaches, there is also the question of how effective the mustard and buckwheat rotations might be without Thimet. n

Using liquid seed treatment? Use Sta Dry to dry your seed, keep your planter cups dry and provide added protection to keep plant vigour when it’s most needed!

Power Start is a phosphate activator that enhances plant vigour. It ramps up plant metabolism and boosts root development, tuber initiation and retention. Best of all Power Start reduces application rates through better placement and more efficient conversion of phosphates.

Pivot Power provides early prevention of root diseases, increases nutrient absorption, and encourages abundant root growth. This product offers flexibility in application - at planting, with sidedressed N and through pivot irrigation. Pivot Power is proven to increase vigour and stress tolerance, decrease incidence of “early die syndrome,” and increase quaility and storability.

For better marketable yield, with qUANTITy AND qUAlITy, follow the formula easy as 1-2-3!

Jacco deLange Vision Agronomics Utopia, Ontario 705-333-1231 vision@cangrow.com

Hal Reed JEM Holding Taber, Alberta 403-634-1671 jem@cangrow.com CAN GROW Crop Solutions, Inc

Ray McDonald Can Grow Alvinston, Ontario 519-847-5748 spuds@cangrow.com

Changes to the tank-mix regulations in late 2009 means potato producers have better options for pest control.

At the request of grower organizations and industry, the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) changed the tank-mix regulations to allow growers to use unlabelled mixes to control insects, weeds and disease, and industry to help them make wise choices when creating an unlabelled mix. The change means that products can be combined as long as they are labelled for use in potatoes and have the same rate and timing of application. Rumours of growers creating their own tank mixes abound, but most recognized the liability inherent in mixing products that were not registered for that purpose. As well, company representatives could not advise use of an unlabelled tank mix because they would be in violation of PMRA regulations.

A spokesperson for the PMRA says there is still some liability attached to unlabelled tank mixes. “The use of a tank mix may have the potential to result in reduced efficacy or increased crop injury,” says Gary Holub. “However, this may be acceptable if there are other benefits associated with using the tank mix, such as cost savings. Therefore, anyone who recommends or applies an unlabelled tank mix does so at their own risk and liability.”

Risks aside, most growers and company representatives see a number of benefits as a result of the change. The opportunities to improve stewardship and minimize resistance development were mentioned most often by industry representatives. “We view the PMRA tank-mix changes as positive for the industry,” comments Todd Younghans of Valent Canada in Guelph, Ontario. “Growers can now tank-mix products that were already approved in the marketplace. The whole process is now easier for growers and retailers with many more options available for pest control.”

“If the products are all registered for use in potatoes, why shouldn’t they be used together?” asks Brady Code, technical field manager with Syngenta

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Crop Protection Canada, also in Guelph. “On the whole, the change to the regulations is good. However, I recommend growers do a ‘jar test’ if they are trying something new.”

He explains that some incompatibility may be observed if small amounts of the two products are combined in a jar and then left to settle. After five minutes, shake the jar again to see if the mix is stable.

Syngenta Crop Protection Canada has a “tank-mix table” that growers can consult when determining what mix might meet their needs. According to Tanya Tocheva, the company’s director of regulatory affairs, “Growers can access the chart to learn which products can be tank mixed safely.”

She says the new regulations help growers because now they do not have to wait for registration and companies are

able to market products more effectively.

“There’s no question this is a huge change,” says Bill Summers, the government affairs and field development manager for DuPont Canada. “While we still have to have some indication that a tank mix has value, it is making it easier for us to communicate options to the growers about what works. In particular, this offers greater opportunities to manage resistance, as tank mixing can delay the onset of weed resistance.”

At BayerCropScience in Guelph, tank-mix opportunities are being communicated to growers through technical bulletins, grower meetings and marketing initiatives. Company spokesperson Greig Zamecnik says whatever the company promotes, it wants to be able to stand behind the recommendation. “We don’t want something to go wrong, so we talk

about tank mixes from a stewardship standpoint,” he says. “This change is a good thing for the industry because it gives everyone more freedom to operate.”

“We are examining our products and selecting those that we can recommend as tank mixes,” comments Dr. Trevor Kraus of BASF in Mississauga, Ontario. “We want to be confident, so some of the mixes will still be tested in research trials. We want a level of comfort before we recommend a mix.”

The changes make it possible for growers to do what is best for their operation in a timely manner. “Mixes can now be fungicide with herbicide or insecticide with fungicide; there are many options,” continues Kraus. “Growers can now have more confidence in their product tank-mix choices. In the past, we would get calls from growers asking if it was okay to mix products ‘X’ and ‘Y’ together and we could not support that combination. Now, with the new regulations, we can take a closer look at many of those combinations in our research

programs and make recommendations more comfortably.”

“Certainly, we now have more flexibility in what we recommend to growers,” concludes Younghans.

“These new recommendations will make stewardship simpler,” adds Zamecnik. “In the past, if we could have suggested a tank mix, we might have been able to head off the onset of resistance development sooner.”

Perhaps what is creating the largest sigh of relief as a result of the PMRA announcement is the reduction of liability. “With that removed, all parties can work together to ensure products are used responsibly and effectively,” Summers comments.

Holub says the policy on the use of unlabelled tank mixes may provide growers with additional opportunities to be better stewards for more reasons than just resistance management. “There may be opportunities to reduce soil compaction and fuel inputs by applying products as a tank mix, rather than sequentially,” he says. “Our preliminary feedback from industry and

A change in tank-mix regulations is providing growers with more options and greater flexibility to control insects such as Colorado potato beetle, as well as weeds and diseases.

grower organizations has been positive (regarding the new tank-mix direction). Growers now have the flexibility to choose to apply certain unlabelled tank mixes at their discretion.”

As growers become more familiar with the change, the result could be some positive opportunities to care for their potato crop in a safe, effective manner. However, the onus will still be on growers to ensure their choices are a compatible mix. n

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Potatoes are a staple in many world diets, but the crop has potential for other uses.

The lowly potato has long been a basic commodity on tables around the world: its peelings have fed livestock and its starch has made countless collars stand straight. Now, a changing world population, and the knowledge that most of our crops have many uses other than food, could elevate the potato to a higher status. In Europe, potatoes are bred and grown for their starch content alone and some of that starch finds its way to North America to be added to domestic products. Canadian breeders and product manufacturers recognize the versatility of this crop and are pursuing products and research for alternative uses for potato.

The BioPotato Network is a consortium of public and private industry organizations with the goal to take potatoes beyond the table. The network takes a four-pronged approach to develop more byproducts for potatoes and to find alternative uses for the crop. The areas the organization is considering are: functional foods and neutraceuticals, low glycemic index and high dietary fibre, starch for industrial use and bioplastics, and biopesticides for insect control. The federal government budgeted $5.3 million towards the network and a dozen organizations and more than 30 scientists are on board to expand the horizons of growers through projects geared to enhancing potatoes.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist Dr. Qiang Liu is working to develop plastic using potato starch. “I think potato-based bioplastics and modified potato starch look promising,” he says. “Potato starch has unique properties that we can use.”

He says the challenge lies in having enough money to get the technology to market, but the launch of the BioPotato Network and the initial funding is a start.

Already, a small company in Manitoba started by two former potato producers, has developed a bioplastic using the starch filtered from the waste water of potato processing. Solanyl Biopolymers Inc. (Canada) is based in Carberry and

Potato starch-based plastics may be a little more expensive but increased demand might mean more industrial uses for potatoes and more rotational options.

is the Canadian branch of a European company. “We make biodegradable and compostable plastics,” explains Mavis McRae, the company’s marketing manager. “Our plastic is used in injection and extrusion moulding where the plastic is melted and shot into the mould. It can be used for many applications, such as toys, pens and plant pots for gardeners, because it can replace hard plastics.”

Solanyl’s process creates a product that breaks down completely in the environment, which makes it more expensive, but also more “green.” The company has one product on the shelves: a biodegradable plant pot that can be used in the greenhouse industry. The Solanyl pots replace the plastic types currently used by the greenhouse industry that eventually go in the landfill because they cannot be recycled. Other products that can be made using the company’s bio-plastic include CD and DVD-trays, cup holders, promotional items and golf tees. “We’re squeezing every last bit of potato out of the potato,” McRae comments. “There are plenty of uses for potato starch.”

In the United States, New Bedford Thread has been using potato starch since the 1950s to coat and smooth cotton thread to make it easier to pull through cloth or fur. “We use potato starch cooked with

water, glue and petroleum jelly until it reaches the correct consistency and then we use that mixture to impregnate the cotton thread,” explains company president George Unhoch. “We have to bring in potato starch from the Netherlands for our use because there is no potato starch processed in the United States anymore.” Unhoch says environmental concerns over the process used to extract the starch caused North American companies to close up shop. “Producing potato starch domestically became too expensive,” continues Unhoch, “because there was concern about the water by-products remaining after the starch extraction.”

Industry shows room to grow

It is the goal of the BioPotato Network to solve some of the problems facing what could be termed “the alternative potato industry.” Liu says there is room to grow the industrial use of potatoes in Canada, but the processes for using potatoes must be perfected and be economical. As an example, it took Solanyl two years to develop the process used to turn potato starch into the resin used by the plastic industry. “I think there is opportunity to separate the starch in our regular processing industry,” Liu says, which would be a value-added aspect for the

industry. “We are trying to think outside the box and use byproducts from the processing plants. It is possible to convert potatoes for other uses, but we don’t want to compete for food uses.”

Although potatoes are bred for starch production in Europe, Liu prefers the approach Solanyl has taken to use byproducts of the industry. He does admit there are areas in which it is difficult to grow good food-grade potatoes, but in which it would be possible to produce an industrial use crop.

However, what if potatoes could be developed that could “multi-task?” Dr. Yvan Pelletier, an entomologist with AAFC in New Brunswick, is looking at breeding potatoes where both the plant and the tubers would be used; the latter for food and the former for another use. In particular, he is attempting to identify the chemicals in the leaves of wild potatoes from South and Central America that allow those plants to be resistant to insect pests (see story on Page 26). If the chemicals can be identified, it would lead to some exciting possibilities for insect control, particularly Colorado potato beetle, either through

Biodegradable and composting plastics are created from potato starch, filtered from the processing water of potato production.

breeding (selecting for the presence of the chemicals) or by extracting the identified compound from the leaves to create a natural pesticide spray for domestic crops. “We are a long way from a commercial

product,” Pelletier concedes. “Some of the hurdles that will have to be jumped will be economic, such as finding an extraction method to prepare the end product and developing a formulation that will stay on the leaves to give control. But, what if we could breed Colorado potato beetle resistance into the plant, then harvest the leaves to create a biopesticide, and still have the crop underneath?”

Researchers have been looking at alternative uses for other crops in the last decade, but with the organization of the BioPotato Network, potatoes are now being considered in this category as well. Liu says there is a great deal of interest in improving potatoes to increase dietary fibre and to lower the crop’s glycemic index. As well, the Solanyl and Bedford Thread examples show there is interest in using the unique properties of potatoes for industrial uses.

No doubt, this old crop is being viewed in a new light and the many scientists involved in the BioPotato Network understand potato’s potential. For potato producers, the research promises growing opportunity. n

by Treena Hein

Compounds found in the leaves of wild potato species are studied in a quest to create more natural pesticides.

As is the case with many crops, some wild potato species are more resistant to insect pests than modern varieties. “This is mostly because of the natural chemicals found in the leaves,” says Dr. Yvan Pelletier, an entomologist at the Agriculture and Agri-food Canada’s (AAFC’s) Potato Research Centre (PRC) in Fredericton, New Brunswick. “Beetles like the Colorado potato beetle try a bite or a few bites of the leaves of wild species, but then stop because of the noxious taste.”

There is also one wild species, notes Pelletier, where adult beetles are very strongly repelled by the plant’s odour alone. “There’s a volatile compound present that’s a very powerful antifeedant,” he says.

Scientists have found success elsewhere with harnessing natural repellents, and teams like Pelletier’s are currently building on this success in all corners of the world. The neem plant, for example, contains a compound that has been isolated and is used effectively against foliage-eating insects. The insecticides Rotenone and pyrethroids were both derived from natural plant chemicals, notes Pelletier. “After these natural compounds were isolated, synthetic forms were then created that mimic their action, but provide a greater amount of stability and strength.”

Breeding and chemistry projects

For several years, two projects have been underway to try to harness the power of the natural chemicals in wild potato leaves. A major long-term breeding project is aimed at combining the genetics in a wild variety with modern varieties; it will lead to the eventual creation of a hybrid cross that still possesses repellent compounds in the leaves but also features all the traits needed for commercial cultivation, and adaptations for Canadian growing conditions. This project is currently being carried out by a large group of breeders at PRC, including Dr. Agnes Murphy,

For several years, researchers have been trying to cross different varieties with wild potato species from South America, including S. acroclossum and S. chomatrophilium

Dr. Benoit Bizimungu and Dr. David De Koeyer, along with graduate students and a co-operative of potato breeders in France called Comité Nord des producteurs de plant de pomme de terre.

From the resistant wild potato species, several successive crosses are required to adapt the plant to Canadian conditions and improve the tuber qualities. So far, the Fredericton team has made five backcrosses with one wild species,

and a few more might be needed before one selection is good enough to become a variety. For each cross, Pelletier says hundreds of plants are produced and tested for Colorado potato beetle (CPB) resistance, but also for other commercially interesting traits such as cooking or cold sweetening. The material derived from the wild S. oplocense species also has a very good cold-sweetening quality, similar to Russet Burbank.

A cross between a species of wild potato, S. tarijense, which is resistant to Colorado potato beetle, and Russet Burnbank, which is CPB-susceptible, is another of the many being studied by AAFC researchers.

Ideally, it would also be nice to be able to harvest the leaves as well as the potatoes from these plants, says Pelletier. “We could extract the chemicals to use on other standard varieties that don’t have resistant compounds in their leaves or even use the extracted chemicals on other crops.”

The parallel project involves isolating the repellent chemicals in the leaves of wild potatoes and developing natural pesticides to control CPB or other insects. In this endeavour, Pelletier is joined by PRC colleagues De Koeyer and Dr. Hellen Tai, as well as Dr. Larry Calhoun from the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, and Dr. Ian Scott at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in London, Ontario. “It sounds like an easy task to isolate the compounds, but it’s quite daunting because there are thousands of chemicals in a plant’s leaves,” says Pelletier. The team is analyzing leaves from six wild species native to South America that demonstrate good insect repellency. One of the species looks like modern varieties do, but all the others are smaller, feature different leaflets (but similar flowers), and creep along the ground. “We’ve been growing three of them for 15 years, and we’ve added the other due to suggestions by colleagues at the International Potato Center in Lima, Peru,” says Pelletier.

All along, the team has been surprised by the variety of compounds they have found. “It’s families of compounds that we have to isolate and identify, in order to see their potential, and there are many of them,” Pelletier explains. “The isolation process is done by looking at the spectrum of compounds using a mass spectrophotometer contained in Russet Burbank potatoes and comparing that to what’s in wild ones.”

Team member and bio-chemist Calhoun then works on determining which chemicals are bioactive and stable enough to use. “We are keeping an open mind,” says Pelletier. “We know there is certainly something in there, but it could be that a mixture of compounds is more important than any specific chemical. It’s not an easy task.”

After the team determines and isolates the active chemical, they will create a stable spray, one that will not degrade in warm temperatures and in sunlight. “We’ll then test these compounds,” says Pelletier, “by spraying them on the beetles, just like you would a regular pesticide, and observing the effect. It will be a great accomplishment to get to that stage.” n

by John Dietz

Tested and researched for Alberta’s growers since 2008, it looks like a good option for 2011.

It has taken a few years, but now there is research showing that slow-release nitrogen can benefit Canada’s potato growers on several fronts.

The product is new, although the concept is not. Coating urea granules with a product to slow the rate of release has been discussed for decades. The New York Times mentioned the concept in a gardening column dating back to March 27, 1966, noting “The nitrogen in the fertilizer is derived from two sources: one (is) a quickly available nitrogen and the other a ureaformaldehyde polymer. Each granule has a coating which protects the core of nitrogen inside. The coating has microscopic holes which release the nitrogen slowly to the lawn.”

Sulphur and various polymer coatings for urea granules now have several applications, worldwide. In China and Southeast Asia, for instance, farmers are gaining access to slow-release, coated fertilizers.