New TitanTM seed-piece treatment gives potatoes the strength to produce healthier plants and higher quality yields. Titan reduces damage from wireworm and controls all of these major above-ground pests: Colorado potato beetle, leafhopper, aphids and flea beetle.

Lighten the load on your crop with the strength of new Titan – the broadest spectrum seed-piece treatment for potatoes.

The fight against diseases and insect pests is never-ending, so Potatoes in Canada provides a glance at some of the more pressing issues.

Plant Breeding

Consumers and processors are demanding more from producers, which puts a little more pressure on researchers for greater diversity and development of desired traits.

Machinery Manager: Irrigation Systems

Four manufacturers have participated in this first edition of this value-added feature.

Cover:

Three months and counting! With the arrival of February, can planting season be that far behind? Photo by Ralph Pearce

February 2010, Vol. 36, No. 2

EDITOR

Ralph Pearce • 519.280.0086 rpearce@annexweb.com

Contributors

Blair Andrews

John Dietz

Treena Hein

Carolyn King

Rosalie I. Tennison

WESTERN SALES MANAGER

Kevin Yaworsky • 403.304.9822 kyaworsky@annexweb.com

EASTERN SALES MANAGER

Steve McCabe • 519.400.0332 smccabe@annexweb.com

SALES ASSISTANT

Mary Burnie • 519.429.5175 mburnie@annexweb.com

PRODUCTION ARTIST

Brooke Shaw bshaw@annexweb.com

GROUP PUBLISHER

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN

ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT.

P.O. BOx 530, SIMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 0705-3878

CIRCULATION

e-mail: mweiler@annexweb.com

Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 211

Fax: 877.624.1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West -8 issues –February, March, Early-April, Mid-April, June, October, November and December 1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issues –February, March, April, August, October, November and December - 1 Year - $50.00 Cdn.

Specialty Edition - Potatoes in CanadaFebruary - 1 Year - $9.00 Cdn.

All of the above - 15 issues - $80.00 Cdn.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2010 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. www.topcropmanager.com

It always seems to happen with a once-a-year magazine: that 365-day retrospective on “What happened.”

Last year at this time, I was looking back on a rather hectic first instalment as chief, cook and bottle washer of this cruise ship. Now, a year later, I am still looking back, thinking of the year’s sights seen and lessons learned.

In 2009, I saw my first potato planting; I attended my first Potato Grower Day at the Elora Research Station (with plenty to see and a few laughs, too). Then there was that rather anxious open house event last August near Alliston, Ontario – the day that five or six tornadoes landed north of Toronto, and unknown to most of us then, sitting skittishly underneath the Big Top, some of those tornadoes were a lot closer than anyone would have thought.

Yet as each event, each deadline and each new story idea comes and goes, I find that each opportunity to learn is just as welcome, and I’m happy to say, just as fresh as the last.

In the past year, I have also seen a kind of territorial sense of pride among potato producers, breeders and industry stakeholders that I have not seen to the same extent in corn, soybeans, wheat or canola. It is one thing to acknowledge the Maritimes for its long-standing reputation for potato production and quality. But there are those in Ontario who want to see more research and breeding done on a local level. There is also research being done on irrigation in Manitoba and on green manures in Washington state.

It all shows me the true picture of potatoes: one crop, many varieties, and many different takes, stakes and loyalties.

Look back but look ahead, too There is also the opportunity to look forward, to this year’s International Potato Technology Expo in Charlottetown, another planting

season and more grower days. And I am hoping there is a trip this summer to Western Canada, where I can learn more about potato production there (among other crops).

This year’s edition of Potatoes in Canada has been another learning opportunity, compiling stories along the lines that I have mentioned already, plus some other very intriguing topics. We are also introducing our Machinery Manager feature to this edition, with a look at irrigation systems (and my thanks to Bruce Barker for his work on this). This feature has become very popular in our other editions of Top Crop Manager , and we hope you find this a valuable resource, as well. It may sound like a broken record when I talk about the “opportunities to learn” but for me, that is one of my few constants (aside from deadlines and answering e-mails). As much as I absorb and commit to memory for future reference, there is always more: more to learn, more to digest, and more of an opportunity to share. And therefore more to enjoy!

EDITOR Ralph Pearce

Only one product gives your crop up to 100 days of protection against irritating pests. In fact, Actara ® lasts longer than any other insecticide. So, you can spray it once and forget about it for the season. For further information, please contact our Customer Resource Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or visit SyngentaFarm.ca

by Rosalie I. Tennison

No time to grow green manure? Use mustard seed meal instead.

Potato crops require large amounts of most inputs and potato growers seek economical alternatives for what this high-value crop requires. Green manure is being touted as an option to provide additional nutrients and increase the soil’s physical properties. As well, it has been proved that green manure is a natural nematicide and can improve yield and tuber quality. But, for Canadian growers, there is often no window of opportunity to seed a green manure between harvest and the onset of winter. The same is true for potato growers in the northern United States. But a researcher at Washington State University in Prosser, has learned that the same results can be achieved by using mustard seed meal, saving growers the effort of growing mustard for green manure. “By using mustard seed meal, which is a byproduct from the biodiesel industry, growers don’t need to grow green manure if it doesn’t fit with their cropping practices,” explains Dr. Ekaterini Riga. “In Washington state, growers harvest late, so there is no time to grow green manure; the same is true for Canada.”

Primarily, brassica seed is used in the biodiesel industry and after the oil is extracted the meal remains. She adds that the meal contains glucosinolates that degrade to nematicides once it is incorporated into the soil.

Riga is collaborating with MPT Mustard Products and Technologies of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, to develop a commercial mustard meal product that can be incorporated into the soil using standard fertilizer equipment. The best time to apply the product, according to Jay Robinson of MPT, is 14 days prior to planting. The mustard meal product, which has yet to be named and receive PMRA registration, shows great promise at reducing or controlling soil borne pathogens, such as rhizoctonia, fusarium, verticillium and pythium. In addition, it makes use of a byproduct that would normally cause concern over its proper disposal.

“This product can also control soil borne pests, such as nematodes, and tests have shown that the use of our product reduces potato scab and blight,” Robinson reports. “The product also includes nutrients and organic matter that encourage microbiological activity, plant growth and increased yield.”

“Mustard seed meal has some nitrogen in it, which becomes available to the plant,” Riga adds. Using the meal will be much easier than growing green manure, especially in the northern United States and Canadian potato growing areas, she continues.

Since the product is still under development cost analyses have not been completed, but Riga believes if the price is competitive it will become a very useful product for potato growers. She adds that, if MPT is successful in getting the product registered, it will be a good alternative to synthetic nematicides. She says meal offers one disadvantage in that there could be phytotoxicity problems as a result of its use. However, in greenhouse trials there was no phytotoxicity recorded.

is a high priority. “All the materials used in this product are renewable and are grown in an environmentally acceptable manner,” he explains.

Therefore, the product is a good fit in any sustainable agricultural practice.

Growers wanting to have the benefits of a green manure crop prior to planting potatoes but rarely have the opportunity, due to weather conditions, to grow a green manure crop effectively, will be able to get the same benefits by using the mustard seed meal product when it is available. Riga expects to have the results from her field tests analyzed in early 2010 and MPT is working on field tests to obtain data to support its application for registration. Therefore, while the product sounds promising and could offer potato growers many benefits, there is no time line on when it will be available commercially.

According to Robinson, the mustard seed meal product fits well into operations where environmental stewardship

Green manures are a valuable tool assisting growers to produce highquality, high-yielding potato crops. A commercial product that can be applied similarly to fertilizer that reduces the time and effort required to grow a green manure crop with the same benefit is bound to be attractive to potato growers across the country. n

Because centimeters make the difference.

Building on the proven performance of the industry’s leading aftermarket hydraulic steering system, Outback eDriveX ™ takes automated steering to the next level. When combined with Outback S3™and BaseLineX ™ or A220, the eDriveX system provides an accurate and affordable steering platform to meet today’s precision needs. eDriveX offers growers the centimeterlevel1 performance needed to tackle most planting and nutrient placement applications while providing a quick return on investment.

• Versatile straight, contour (free-form) and circle pivot steering modes

• Model specific installation kits allow for quick installation

• Outback S3, BaseLineX and A220 compatible

• Facilitates precise steering tasks such as planting, bedding and nutrient placement

• Quick single-season return on investment

• Proportional hydraulic control for rapid line acquisition and smooth on-line performance Contact us today at 800-247-3808 or order online at www.OutbackGuidance.com.

The two-year option, potato and canola or wheat, is a slippery road into lower yields and disease.

Back in 1997, when Manitoba’s potato industry was in an expansion phase, industry and researchers wondered if irrigation and good management could enable them to produce potatoes on a field as frequently as every second year.

They set up a long-term study to get answers they could trust. “The study was initiated in 1997; the rotations were initi-

ated in 1998,” says Dr. Ramona Mohr, lead scientist in the collaborative effort. Mohr is a sustainable systems agronomist at the Brandon Research Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). Most of her work deals with potato rotations and potato nutrient management.

Known as the Carberry Potato Rotation Study, it was set up at the CanadaManitoba Crop Diversification Centre (CMCDC) near Carberry, Manitoba. CMCDC and AAFC were partners, supplying resources for the study. Scientists from the University of Manitoba also participated. “Our overall objective

by John Dietz

was to look at two factors. Which crop rotation would optimize yield and quality while minimizing pest problems? Second, which rotations would also maintain or enhance soil quality?”

The rotation study yielded a great deal of other information that will be useful to the industry, Mohr said. Her report on the rotation options was to be presented in late January to Potato Days in Brandon and, a week later, at the Manitoba Soil Science annual meeting.

Lab analysis is still underway with more results expected later in 2010.

The study examined production results

The pattern of disease control has suddenly changed. Now you can rev up your fruit and vegetable disease programs and throw mildews and blights a curve with Revus® fungicide. With one-of-a-kind LOK + FLO™ action, Revus quickly locks into the waxy outer surface of leaves and gradually filters in to deliver consistent performance rain or shine. Make Revus an integral part of your disease management program. Break the mold™ . For further information, please contact our Customer Resource Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or visit SyngentaFarm.ca

Incidence of vascular wilt disease in potato as affected by crop rotation (2004-2009). Disease ratings are expressed as the percentage of infected plants per number of plants examined.

from rotations of two, three and four years. All of the plots were in similar growing conditions. The potatoes were irrigated but the non-potato crops were not irrigated.

Each rotation had two variations. The short rotation was either potato-canola or potato-wheat. The three-year rotations were either potato-canola-wheat or potato-oat-wheat. One of the four-year rotations was potato-wheat-canola-wheat; the other was potato-canola-alfalfa-alfalfa. The alfalfa was first underseeded and then

managed as a hay crop.

The study needed to be long, with three full repetitions of the four-year rotation, to give a high level of confidence in the results. The final impression was quite different from the first impression. “The first few years the rotations were established we didn’t really see any effect on yields,” Mohr said. “After that, in some years we did see yield differences among the rotations but there wasn’t any single rotation that consistently out-yielded the rest, in potato yield. Up to about 2006,

rotations that seemed to perform a little bit better than the others were the two-year potato-canola, three-year potato-canolawheat, and the four-year potato-canolaalfalfa-alfalfa.”

However, when the results were all analyzed from the 2007 growing season, there appeared to be a change. That change was repeated in the 2008 and 2009 seasons. “The most interesting has been the last three years. During that time we’ve seen lower yields in the short two-year rotations compared to the three- and

Alias® imidacloprid insecticide controls potato pests right from the start with an in-furrow or seed-piece treatment. With the same active ingredient as Admire®, Alias delivers superior, broad-spectrum control of potato insects, including Colorado potato beetles, aphids and leafhoppers.

If it’s bugs you’re after, pull out the Silencer®. It takes out a broad range of crop damaging insects. Silencer, with the same active ingredient as Matador®, is a Group 3 pyrethroid that delivers more bang for your bug when protecting potatoes.

Tough insects don’t stand a chance against Pyrinex®. It protects your potatoes from a broad-spectrum of insects, increasing your yield and improving quality. Pyrinex, with the same active ingredient as Lorsban®, is a Group 1B insecticide that provides sure-fire control of Colorado potato beetle and potato flea beetle. For great crop protection at a fair price, contact your local crop protection retailer and ask for MANA insecticides.

four-year rotations,” explains Mohr. “Our plant pathologist, Dr. Debbie McLaren, at the same time has been finding much higher levels of vascular disease in the potato in short rotations. That’s really the big story coming out of the study.”

By 2009, tuber yields for the short rotations averaged only about two-thirds of yields in the longer rotations. Yields were compared using tubers with a diameter of at least five centimetres.

In the field during the final three seasons, researchers could see obvious signs of a disease called vascular wilt.

“You tend to see leaf yellowing followed by wilting, senescence, and death of the plants before normal maturity” she said. “In 2009, 99 percent of the potato plants surveyed in the two-year potatocanola rotation were showing evidence of vascular wilt. We were seeing very high levels of that disease.”

The highest disease incidence, and most severe, was in the potato-canola rotation. Potato-wheat showed the next highest level. It is thought that the vascular wilt contributed to lower yields in these short rotations.

Vascular wilt pathogens can overwinter in a field. Results of the study indicate there is less vascular wilt risk when the rotation is extended beyond one year.

The study concludes that “the performance of a given rotation in the years immediately after a crop rotation system is established may not reflect its performance in the longer term. During the initial nine years of the rotation study, consistent effects of rotation on yield were not evident, although there was some evidence of increased potential for disease in the shorter rotations.”

Analysis of the economic data still was underway in mid January. Based on just the yields and disease issues, Mohr said, “So far it looks like the two-year rotations are probably not sustainable here in Manitoba in the long term.”

Changes in soil chemistry and physical properties, in microbial populations, in wireworm damage and in weed populations were monitored during the 12-year crop rotation at Carberry.

It may be worth the investment, she said, to take the study a few years further in a somewhat new direction. “We’re interested in whether we can reverse this effect. Can we apply management practices that would reduce the disease load and allow us to bring those yields up again? Can we turn this thing around?” she asked. n

by Carolyn King Markets

Variety from 1800s being examined for its diversity.

The “wet, tasteless and unwholesome” potato variety that triggered the Irish Potato Famine. That is the Lumper’s unhappy reputation. This much-maligned tuber piqued the interest of Vanessa Currie, who leads the potato variety trials at the University of Guelph’s Elora Research Station, northwest of Guelph, Ontario. Naturally she wanted to try it out.

Currie first learned about the Lumper when she was asked to be one of the potato specialists in a proposed docudrama about the Irish potato famine. Potatoes, which are native to South America, were brought to Ireland by the late 1500s. By the early 1800s, millions of poor Irish people relied on potatoes as their only crop and only significant food source. Then in 1845, late blight struck the Irish potato crop. It wiped out almost half the crop that year and nearly the whole crop the next year. During the six years of the famine, more than a million people died from starvation and related diseases, and another million emigrated.

The Lumper was the variety eaten by Ireland’s poor and also the variety most affected by late blight at the start of the outbreak. “In researching the late blight and the Irish Potato Famine, I got interested in the cultivars that they were using. Three cultivars were commonly grown: Apple, Cup and Lumper. Apple and Cup were considered quite edible, but the Lumper was most reviled. It was considered wretched, unpalatable, unfit for humans, and even beasts would reject them if another variety was available,” says Currie. “It seems that the Lumper’s abundance was based solely on economics. It outyielded the others by as much as 30 percent. At a time when hungry bellies were plentiful, people filled them with Lumpers. I was fascinated at the idea that four million

people could be fed on a potato that was considered ‘scarcely food enough for swine.’ How bad could it be, if an entire population was living and thriving almost exclusively on it?”

She notes, “I have tested new potato germplasm for more than 20 years, and seen thousands of different selections and varieties. Some are worse than others, but I have never tried one that sounded as awful as the Lumper.”

To find out where to get Lumper germplasm, Currie contacted Jane Percy at the Potato Gene Repository

of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). The Gene Repository, which is at AAFC’s Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, keeps Canadian and international potato germplasm. It turned out that the Lumper is one of the heritage potatoes in the Repository’s collection, so Percy sent some tissue culture plantlets to Currie in the fall of 2008. “I grew the plantlets in the greenhouse last winter and got little mini-tubers that I was able to plant at the Elora Research Station in the spring of 2009,” says Currie. Although she did not have fully grown seed potatoes to do a regular trial, she was able to do a small test with 200 Lumper plants.

The mini-tubers grew quite well and produced large, vigorous vines that looked like the other potato varieties. She adds, “Late blight is a worry for growers all across Canada, and people learned that the hard way in 2009. But the Lumper doesn’t bring any more risk of this disease than any other variety.”

Currie and her summer students dug up and cooked some Lumpers for participants at the station’s August open house. “The yield was good and it was not hard to see why so many poor families had thrived on them,” she says.

“The tubers were oval to oblong in shape, with deep eyes and a rough, knobby appearance. The skin was smooth and pale. The flesh was cream coloured, not white, but not yellow. They were quite possibly the most ugly potatoes I have grown.”

Surprisingly, the notorious tubers tasted quite good, pretty much like any ordinary potato.

Perhaps the Lumper’s reputation has taken a few undeserved lumps? “The Lumper’s poor reputation seems to have preceded the blight and the famine. But I don’t know why people would think it was that much worse than the Apple and the Cup,” says Currie. “Maybe it was just the taste of the people at the time, maybe their storages were poor and musty, maybe some of the Lumper potatoes were a bit blighty all along and a bit rotten. Maybe the next step is to grow the Apple and the Cup here as well to see if there are some differences!”

She notes that the humble Lumper taught a tough lesson about monoculture production. “I think the blight and famine in the mid-1800s were a real wake-up call to agriculture in general.

They learned that they couldn’t rely on just one variety. In South America, the population there at the time had hundreds and hundreds of potato cultivars that they grew all the time, so if one failed or did poorly, they had others.”

The Lumper’s lesson was taken to heart in Canada, she says. “We have historical records at the University of Guelph dating back to the 1890s in which they were doing potato trials, testing hundreds of varieties. Those records say that in Ontario at the time there were some 4000 farmers doing different plant research on their farms. That’s amazing!

“I think the intense interest in crop breeding and varieties was a direct result of the failure of the monoculture only a generation or two before that. The people doing those trials in the 1890s would have been the children and grandchildren of people who had died or emigrated from that famine. They saw the relationship between breeding, diversity and protecting the crops we want to grow.”

Currie will put the Lumper in the Elora Research Station’s regular potato trials in 2010, and will conduct the regular evaluation of characteristics like yield, taste, cooking and storage. The goal of these annual trials is to identify new chipping and table varieties with commercial potential for Ontario. AAFC potato breeders in Lethbridge and Fredericton,

as well as breeders from the northern United States send their selections to the station for testing. In 2009, about 120 potato selections were evaluated. Results from the trials are provided to breeders, growers, processors and retailers. The trials are supported by a long list of funders including the Ontario Potato Board, Farm Innovation Program, Ontario Research and Development Program, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, University of Guelph, AAFC, and Canadian Snack Food Association. n

While the Lumper is indeed a lumpy looking tuber, that’s not how it got its name. Vanessa Currie learned from John Reader’s book, Propitious Esculent: The Potato in World History, that in the 1800s dock labourers in England who unloaded timber cargos were called lumpers. She says, “We have the term ‘lumberjack’ here, but they were originally called ‘lumperjacks.’” Many lumpers were Irish, and it is thought that some lumpers returned to Ireland with the variety, so it was called the Lumper.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Proven and new chemistry products launched by Syngenta Crop Protection Canada in 2009 are giving growers some new options for seed treatments and late blight control. Revus, registered in 2009, is billed as a “late blight specialist,” while Cruiser Max Potatoes is the first liquid seed piece treatment for both insect and disease control.

Registered for multiple crops, Revus will be of particular interest to potato growers because it protects plants against oomycetes fungi by reducing spore germination. Fields infected with late blight, downy mildew and phytophthora blight will benefit from an application of this new product.

Revus is a Class 40 chemistry, one of only two products in this class, according to Tara McCaughey, Syngenta technical crop manager. Speaking to a group of growers at a Potato Field Day, McCaughey reported that Revus is “rain fast” because it binds to waxy leaf surfaces. “This is a translaminar product that will provide protection to both the top and bottom of the leaf,” she explains. “Revus uses a unique LOK + FLO trademarked technology in combination with the activity of mandipropamid.”

In company literature, Syngenta explains the action of Revus as follows: “upon application, mandipropamid locks (LOK) tightly to the waxy cuticle of treated leaves, quickly becoming rain fast and establishing a barrier to prevent fungi from taking hold. Meanwhile, a steady supply of fungicide enters the leaf, flowing (FLO) through the inner tissue by translaminar activity to protect both sides of the leaf with a longlasting reservoir of the active ingredient.”

“Revus has a low-use rate of one jug per 16 to 24 acres,” continues McCaughey. “It will also work well in a resistance management strategy.”

Growers are advised to use Revus in a rotation with other classes of fungicides that are labeled for control of the same diseases, a practice that will reduce the potential for new infections in a field.

Another new product, according to Scott Ewert, Syngenta’s seed care specialist, is Cruiser Max Potatoes, which is a combi nation of Maxim liquid PSP and Actara 240SC offering control of Colorado Potato

Beetle, potato leaf hopper, aphids, rhizoctonia, fusarium and silver scurf. “The values of Cruiser Max for Potatoes are the lower dose rate that is used on seed and its ease of application,” Ewert explains. “With dust products, you can’t always get the desired treatment on all of the seed. With this liquid treatment, you are treating all sides of the seed piece to get improved coverage and control.”

Ewert says the liquid formulation is an improvement for growers in terms of exposure because, with a liquid application, all the treatment is in an enclosed area. “A requirement for growers wanting to use Cruiser Max Potatoes is to have a treater able to apply this new technology,” he says. “It is important to completely cover the seed to protect the plant.”

He says the Milestone liquid applicator is proving to be the best method of applying

by ralPh Pearce

the company is evaluating other liquid applicators as well.

According to Ewert, Syngenta is investing in new seed treatment products for the future that will also be in liquid form. Getting access to new technology is positive news for growers, especially with the products’ ability to control a variety of

The FarmCare® Program from DuPont is designed to make your life easier by making your crop input decisions simpler. Our crop protection portfolio has the products and performance you want, backed by years of experience. Add exceptional value and you’ve got a powerful combination that will yield bottom-line results for your operation. Get everything you can out of your crops, and everything you can for your dollar. Crop protection is what we do best. FarmCare® is for what you do best.

by Treena Hein

Rotational options are important for a number of reasons. They provide income, help control disease and insect pests in the potato crop, and can also contribute to the maintenance of soil health.

Rotation is often first considered from an above-soil perspective, says Dr. Claude Caldwell, professor of crop physiology at the Nova Scotia Agricultural College in Truro, Nova Scotia. “However, you also must be concerned about what’s going on underneath the soil surface,” he stresses.

Caldwell is currently involved in two studies on how rotational crops can help secure root health at the same time profits are maximized. One is an oilseed crop project involving canola led by Don Smith at McGill University for which it is hoped funding will soon be secured.

“With the new crushing plant up and running about 14 hours’ drive away in Becancour, Quebec, they’re expecting a large 2010 canola crop,” Caldwell notes. “The research is needed.”

The new plant will process approximately one million metric tonnes of oilseeds (600,000 tonnes of canola and 400,000 million tonnes of soybean), and generate annual sales of $450 million.

Caldwell will be co-ordinating basic agronomy experiments to determine the best planting date and seeding rate for canola at eight sites across Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec.

“We will also be measuring how canola affects the base rotational crop, whether that’s soybeans, corn or potatoes,” he notes, “Rooting depth and rooting pattern is very important in rotation to break up the soil and stimulate invertebrate and micro-organism activity.”

He will also study how canola can be used to increase nutrient use efficiency and break disease cycles. “Potatoes leave a fair amount of nutrients in the soil,” says Caldwell, “and the hope is that canola can use these effectively.”

Camelina is the focus of his other research. “I’ve been working with it for the last five years,” Caldwell says. “We’re seeing it as a very positive crop

for potatoes as it’s very resistant to diseases and doesn’t share diseases with potatoes.”

While camelina is being grown for jet fuel production in other parts of the world, Caldwell says it is being looked at in the Maritimes for its oil for human consumption and for aquaculture feed. “We want it to be a profitable cash crop for farmers here,” he says. “We’ll also be examining its effects on nematodes and root disease.”

New best practice advice

Dr. Christine Noronha, who studies pest resistance at the Agriculture and Agri-food Canada Crops and Livestock Research Centre in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, has a few tips for growers with regard to controlling pests with rotation. “The mandated use of this practice is definitely beneficial in disrupting the life cycle of insects,” she says, “but because pests move around, distances are critical. That is, when a grower plants a field for potatoes that has been in rotation, it needs to be as far away as possible from a field where potatoes just grew.”

Even a few hundred metres, says Noronha, can make a difference. “The further you put a food source away from the pest’s stronghold, the more you will

reduce the pest population,” she explains. For this strategy to really be effective, however, area-wide collaboration is needed. “If you have an area free of a pest, you can expand that area with collaboration. Talk to other growers and do what you can to make it better for all of you.”

Some pests will turn to weeds as an alternative food source when their foodsource field is planted with something else in the rotation. “So this means if you can control nightshade and other weeds, you can reduce the pests because they have no alternative to feed on,” says Noronha. “Delaying planting also helps, because if the pests have nothing to eat, they’ll leave.”

Weed scientist Dr. Jerry Ivany, also at AAFC Charlottetown, says that traditional rotation options of barley underseeded with clover and timothy mix

have now been replaced by animal grade soybean and some food grade soybean crops by growers who want a higher value cash crop in the rotation. He cautions, however, that before a new rotational crop is chosen, growers need to ensure that there are herbicides registered for use on the crop, or they may be sorry in terms of weed management. “However,” he notes, “if there is no herbicide registered for that crop, you can reduce weed problems by choosing a field with a low weed density or by reducing the weed density before planting by cultivating the field, letting weeds grow for seven to 10 days, cultivating again, and then seeding. Make sure you have no broadleaf perennials and quack grass.”

With regards to controlling broadleaf perennial weeds such as field mint, perennial thistle and mugwort that are problems in the potato crop, Ivany advises controlling them before you plant. “None of the potato-registered herbicides control broad-leaf perennial weeds very well, so growers have to think ahead and control the year before, and some are not doing this,” he says. “Fall application of herbicide products that control broadleaf-perennial and quack grass on barley stubble is recommended, and the use of Roundup Ready crops such as soybeans will also mean you’ll have less of a problem with the perennial weeds in your next year’s potato crop. Growers who buy or rent new land for potatoes need to find out what perennial broadleaf weeds are present. and if those weeds are in the field. then plan to control them in the rotation before the potato year.”

Dr. Rick Peters, who studies vegetable diseases at AAFC Charlottetown, says his research has indicated that length of a rotation is a key consideration for reducing soilborne diseases in potatoes. In a long-term trial in Harrington, PEI (19942008), Peters compared two-year (potatobarley) with three-year (potato-barley-red clover) rotations. “The potatoes grown in three-year rotations were consistently significantly less diseased than those grown in two-year rotations, particularly with respect to diseases caused by rhizoctonia (stem and stolon canker; black scurf),” he says. “Growing non-host crops between potato crops for successive years causes a natural decline in pathogen populations in the soil.” Peters notes that in some situations (organic growers and conventional growers in some parts of the world), rotation cycles are extended

so that potatoes only appear once every four or five years.

The type of crops grown in a potato rotation can also impact on disease severity. “Our research has shown that growing brassica crops, like canola, prior to potatoes can reduce the incidence and severity of soilborne diseases caused by rhizoctonia,” says Peters. “This is particularly effective when canola is used as a green manure crop prior to potatoes.”

The breakdown of the canola tissues in the soil releases chemicals that are toxic to pathogens and also stimulates increased soil microbial activity that leads to biological control of pathogens.

Peters is also experimenting with using sorghum-sudan grass as a green manure crop prior to potatoes. “In some production areas, it has been shown to reduce Verticillium wilt in subsequent potato crops,” he says. n

Proven airflow and ventilation performance. Structural steel plenums, catwalks, interior & exterior fanhouses. Questions? For more information please call 1-888-315-1035 and ask for AG-STOR ® or visit us online @ www.behlen.ca

Although European corn borer pressure during the early part of the 2009 growing season was less than in 2008, by the middle of last September, tell-tale broken stalks and entry holes were surprisingly commonplace in the potato fields of Prince Edward Island. “The European corn borer (ECB) has become an annual pest here over the last few years,” says Brian Beaton, potato co-ordinator with the PEI Department of Agriculture. “The pressure varies from season to season depending on the weather conditions, but most years we see some damage.”

Indeed, it most likely was the weather in 2009 that allowed ECB to slip under the radar. “Because of the rain in the early summer, it seems that the period that the moths were laying eggs was extended,” Beaton says. “Some of the scouting reports had indicated a lower population than usual. But eggs being laid over a longer period of time, three to four weeks, resulted in some fields having more damage than we expected.”

After observing low numbers of eggs, many growers decided not to treat their fields, but enough eggs hatched to cause significant damage later in the season. However, with close monitoring and a solid knowledge of both the pest and pesticide options, growers can ensure they have better results in years to come. “Successful control of ECB requires a thorough understanding of the insect’s life cycle,” says Gilles Moreau, an agronomist with McCain Foods in Florenceville, New Brunswick. “It is best achieved with a well-designed integrated pest management program consisting of pheromone traps, field scouting and interventions at key points along the cycle.”

To attract male moths, the pheromone traps should be placed along the perimeter of the field in mid to late June to monitor moth flights. Moreau says once moths have been captured, scouting the fields twice a week for egg masses should

The extent of damage caused by European corn borer in the Atlantic provinces has been an unpleasant surprise to many.

begin. Egg masses are not easily seen by an untrained eye. They are flat, creamy white and layered over each other, giving the appearance of fish scales on the plant stems or leaves. As egg masses get ready to hatch, they turn black.

Moreau stresses that egg masses are not the only thing growers need to be aware of. “Finding two to three egg masses per group of 10 plants may be a good threshold for spraying, but factors such as crop health, presence of other pests and environmental conditions must be carefully considered in the decision as well,” he says. “These concerns can all affect whether or not egg masses develop and produce larvae. They don’t all necessarily do so.”

This is why continued scouting throughout the egg-laying and hatching periods is so important, says Moreau, and should include hunting for entry holes. Moreau says that those who successfully controlled the insect and did not suffer yield loss scouted fields regularly in 2009. They noted the number of egg masses, monitored their development and tracked the viability of newly hatched larvae.

Moreau also advises farmers to consider

burning or plowing the dry stalks in the fall or early spring, as this will disrupt the life-cycle of the insect and possibly lead to significant mortality.

While it is best to spray most insecticides at peak ECB egg hatch before the neonates bore into the stem, the pest’s sometimes drawn-out laying behaviour can mean it has no peak hatching point to speak of.

Dr. Robert Coffin, a research scientist with Cavendish Farms in Dieppe, New Brunswick, says that is why an insecticide effective at multiple stages of the ECB life cycle is so very useful. “An ovicidal insecticide doesn’t have to be sprayed just when larvae are hatching,” he explains. Unlike most insecticides, Coragen kills both ECB larvae in the eggs and larvae after hatch. It is in a new chemical class with a new mode of action (Group 28, anthranilic diamide). “It’s also very important that products have good residual action,” says Coffin. “If growers are using a product that will only last for a short time, they have to worry a lot more about pinpointing

exactly when it’s best to spray.”

Blair Fraser, a sales representative with DuPont, says the spray’s active ingredient moves into the leaf and stays in the leaf tissue where it is protected from wash-off and can be ingested by pests. It also stays on the stem, so if the larvae begin to burrow into the stem they ingest additional active ingredient.

Beaton observes that Coragen performed well again in 2009. “It has a

longer residual control period for ECB than some products,” he says, “and that makes the window to apply the product larger, and should provide better control.”

Grower Kevin Hunter, along with his brother Donald and father Carl, farms 850 acres of processing potatoes, mostly Russet Burbanks and Shepody with some Ranger Russets, plus 100 acres of seed potatoes in Kensington, Prince Edward

Island. “In our opinion, Coragen has the longest period of activity,” he says, “which allows us to go in a day or two earlier than with other products. With our current acreage, this is really important, because it takes about four days to spray it all even if the conditions are continually favourable.”

Hunter has an experienced employee who scouts about a third of his acreage for ECB. “There’s a knack to finding the eggs,” says Kevin. “They’re often on the borders of the fields and in sheltered areas. If they’ve already laid on the borders, they’re probably laying in the middle of the fields, but if you go ahead and spray with Coragen, its residual activity takes care of all of it.”

“I’ve heard generally very positive results from farmers,” says Coffin. “Some people tried spraying twice, but once seems to give the suppression.”

Hunter sprays once, which he says helps them comply with the “stringent environmental laws” on PEI. “Having an effective product with a longer residual means you use less and use only one chemical,” he explains. n

The potato was cultivated over 2,500 years ago by the Incas in Peru and Chile. Although a dietary staple, the Incas didn’t just grow potatoes for food – they processed them, used them for medicinal purposes and believed they had mystical qualities.

The Incas learned to preserve potatoes through a mashing/dehydration process to safely store them for up to ten years. Additionally, they discovered medicinal properties, using them to aid in childbirth and treat injuries. They even buried potatoes with their dead to provide nourishment for their afterlife.

Another significant event in potato history was the introduction of Admire® insecticide in 1995. Admire quickly gained widespread recognition as the insecticide Canadian potato growers could count on to deliver higher yield and better quality.

Indeed, history shows that Bayer CropScience has always brought the latest technology to Canadian growers by devoting significant funds to the research and development of brand names like Admire.

by Treena Hein

Using industry residues as soil amendments provides many benefits.

Soil scientist Sherif Fahmy is excited about turning organic industrial “wastes” into something beneficial.

In this era of climate change, decreasing oil availability and rising energy costs, he is not alone. Residues from a multitude of activities including crop farming, logging, sawmilling and even poultry production are being converted into a host of valuable products, from bio-oil and cellulosic ethanol to heat and electricity.

For more than a decade at the Agriculture and Agri-food Canada Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Fahmy has studied the effects of using pulp and paper industry residuals as soil amendments, and has returned some exciting results. During four three-year cycles of growing legumes, potatoes and grain, Fahmy has observed improved soil-water retention and nutrient content, reduced soil erosion and nutrients leaching, and increased crop yields. “Diverting these residues also means the lifespan of landfills is extended,” he says, “and the methane that would have been emitted from these compounds as they break down is avoided.”

The two soil amendments are raw pulp fibre residuals (PFR) and its compost (CPFR), both of which meet the quality guidelines of the Composting Council of Canada. “PFR is the very short cellulose fibres floating in the pulp and paper mill effluent after processing wood chips,” Fahmy explains. “These fibres are flocculated using a resin and precipitated in huge holding tanks, then removed and reduced in moisture content before disposal.”

The nugget-like residue is then used “as is” (raw PFR) or used as an ingredient in a compost formula to make a value-added product (CPFR). The nuggets act as reservoirs for water and dissolved nutrients in the soil.

The study’s first three-year rotation involved growing clover, barley and potatoes in soil containing raw PFR. The second rotation featured field peas, corn and potatoes in soil with CPFR, and the third rotation involved field peas, corn and potato, in soil which again contained raw PFR. The fourth rotation, which ends in March 2011, is being conducted with organic agriculture conditions. Fahmy used both rain-fed trial plots and rain-fed plots with supplemental irrigation.

In general, the overall results of the first two rotations show that moisture content of treated soils was boosted by five to 10 percent, and runoff initiation occurred at a point two times longer than the control. “Our research team also found a 23 percent reduction in runoff and a

71 percent reduction in soil loss due to runoff,” notes Fahmy. “This is especially important to growers in highland areas such as the potato-growing belt around Grand Falls, New Brunswick, which are susceptible to erosion.”

The residues also increased the bio-availability of N, P and K.

In terms of crop yield, red clover, barley, peas and corn yields were significantly increased. Potato yield increased slightly but not significantly. The rain-fed supplemented by irrigation experiment, gave inconclusive results.

While Fahmy firmly believes that the potential domestic and foreign markets for soil amendments from the pulp

and paper industry are large, he sees a number of milestones that must be reached before that potential can be realized.

The first task, he says, is to expand the scope of the trials. “The research has been carried out in small plots, and must now be conducted at the field level on a demonstrative farm setting within the agricultural production community,” he notes. “This will be done next when funding is secured.”

Fahmy would also like to see a large one-year international field demonstration study in a country with different environmental and climatic conditions than Canada. “Testing the amendments under different precipitation and growing conditions would be ideal in helping to confirm the beneficial gains to farmers here and elsewhere,” he says. “It would also show the world that Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada is concerned about the environment and is working to achieve an environmentally sustainable agriculture industry.”

A small study of the local market for these soil amendments was carried out by a senior class at the University of New Brunswick’s Saint John campus. “It was helpful but not elaborate enough,” Fahmy says. “A professional market study as well as a commercialization study needs to be carried out locally, nationally and internationally.

It must address such factors as how best to educate growers on the use of the amendments and the cost of transporting them.”

Once these steps are taken, the Government of Canada, perhaps through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), would be in a good position to promote the use of these types of soil amendment locally and internationally, especially where

CanGrow_4.5x7.5 1/24/06 2:08 PM Page 1

soils are low in organic matter and water conservation is critical. “The marketing of this product to Canada and the world is of great importance,” says Fahmy. “It will improve the environment by recycling the residue into the soil instead of sending it to landfills. This, in turn, will help in reducing global climate change. I believe we do not own the land, but we borrow it from our children.” n

In potatoes, as in all crops, a Good Start does more to ensure a Great Finish

For better marketable yield, with quantity and quality that results, follow the formula that’s as easy as 1 - 2 - 3!

Begin with CAN GROW’s Up Start program, a starter formulation specifically designed for in-furrow use. Up Start provides the seed and seedling with an abundance of soluble calcium, reducing plant stress, increasing cell wall thickness, all of which leads to improved seedling vigour and uniform emergence.

Complement that with PowerStart, a phosphate activator that enhances plant vigour by elevating levels of phosphorylase, which ramps up plant metabolism and boosts root development, root activity, tuber initiation and retention. Best of all, it reduces application rates through better placement and more efficient conversion of phosphates.

Every crop begins with good seed stock, and STA-DRYorganic-based seed treatment provides an added measure of protection that helps plant stand and vigour when plants need it most!

deLange

by Rosalie I. Tennison

The collection of the Potato Gene Resources bank is not large, but it is useful.

Breeders focusing on developing a variety with a desired trait often withdraw genetics from Potato Gene Resources at the Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The repository of potato genetics currently has about 150 clones, but there is some concern that the Canadian collection is genetically narrow. Currently, more than 80 percent of the collection consists of heritage and Canadian-bred varieties, meaning there may not yet be enough genetic diversity in the collection for Canadian breeders to tap into it in a meaningful manner. “Certainly, our potato genetic resource program is not large,” admits Dr. Ken Richards, the manager of Plant Gene Resources in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. “Our collection is not as large as those of the United States or at the International Potato Centre (CIP) in Peru, but it was designed to capture and preserve heritage potatoes that have been grown in Canada.” Breeders have access to US or Peruvian collections to incorporate germplasm into their programs to get the desired genetics they want, he adds.

It takes time and resources to build a collection of potato germplasm and it is also an ongoing process to manage the collection. Unlike grains that can be stored dry and only need to be grown out periodically, potatoes have to be grown regularly. The collection also must be disease free and, therefore, before a variety can be stored in the collection, it has to be tested for disease and virus incidence and, if infected, cleaned of them. In any given year, about 10 per cent of the collection is in clonal form and the remaining percent of varieties is maintained in vitro

Garrett Pittenger works with Seed of Diversity, an organization that preserves Canada’s seed heritage. He has donated

Despite the wide variety of sizes, shapes and colours of potatoes grown in Canada, researchers are concerned with the genetic diversity, and are working to broaden their collection of different germplasm.

numerous heritage potato varieties to Potato Gene Resources because he wants to ensure the collection is diverse and useful. He says that, because many heritage varieties have been preserved, it is now possible for breeders, growers and consumers to enjoy potatoes that had fallen out of favour but are now making a comeback. “We are now appreciating the purple or blue varieties for their anti-oxidant properties,” Pittenger comments. “We may need to ‘re-commercialize’ some of the heritage varieties because growers will grow them if there is a market.”

However, without Potato Gene Resources some of the varieties might no longer exist. Pittenger would like to see niche markets developed, which will help preserve Canada’s potato heritage rather than leaving all the work to Potato Gene Resources and a handful of dedicated potato preservationists.

Blair Andrews

Canadian research scientists are working on a unique project to identify the millions of bacteria in soil with the aim of lowering management costs for potato growers.

The researchers are using DNA technology to develop diagnostic techniques for soil health indicators. The purpose is to use those natural processes to more rapidly develop and rebuild the soil structure and microbiology to the point at which farmers could reduce their reliance on chemical fertilizers and other costly inputs.

The idea stems from work conducted by Dr. George Lazarovits, a research scientist at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research station in London, Ontario. Dr. Lazarovits is one of the leading researchers on the use of byproducts of animal production, such as meat and bone meal, feather meal, and poultry and swine manure, as agents that effectively reduce soilborne plant diseases. The concept, known as suppressive soils, makes use of nutrients to manage soilborne plant parasites, thereby giving farmers alternatives to fumigants when disease resistant cultivars are not available. Interest in the subject is growing because fumigation is being constrained by increased costs, urbanization and the negative environmental impacts of urbanization. As for cultivars, resistant genes to soil-borne pathogens are often not available for many crop species.

Part of Lazarovits’ work required identifying the impact of the nutrients on the micro-organism community in the soil. He says people wanted to know if the byproducts were helping the beneficial microbes. “The big problem, of course, is who the good guys are? A simpler question is, ‘who is there at all.’ It has always been my interest to find out who lives on the root of a plant and who is in the soil,” he explains.

Two different sources have inspired his research ideas: grafted horticultural plants and sugarcane production in Brazil. Commenting on the former, Lazarovits says grafted plants, such as tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers and watermelons, have been a remarkable replacement for the fumigant methyl bromide. “When you

take a commercial cultivar of a tomato, for example, and you put it on to an older, more primitive rootstock, you get this incredibly productive upper part of the plant.”

He suspects that there must be something in the older root systems that is giving the commercial plant new vigour. “They require less fertilizer, less water and fewer herbicides because they can tolerate a lot more stress in the form of heat. And they’re resistant to pathogens.”

While potatoes cannot be grafted, Lazarovits says researchers can examine how the soil is helping the grafted plants and they can determine how they might increase the vigour of potatoes in a similar fashion.

In addition to searching for clues in grafted plants, Lazarovits is also interested in examining the research in Brazil, where the country turned to producing ethanol from sugarcane to replace the importation of oil in the 1970s.

With the idea that cost of production had to be low, Lazarovits says the scientists went to the poorest farmers they knew: those who could not afford to use any fertilizer, and screened the varieties that were grown in the low-fertility soils. He says they found cultivars that produced good yields with minimal input costs. After the scientists put the cultivars into tissue cultures to eliminate viruses and planted them in the fields, Lazarovits says they created another

problem. “These plants did not grow very well after they put them into tissue culture. They discovered that inside these plants were about half a dozen bacteria in very high populations. The tissue culture eliminated these bacteria. When they put the bacteria back into the plants, they grew normally again.”

He adds that Brazilian growers only use about 50 kg of N fertilizer per hectare (44.6 lbs per acre) whereas American farmers who grow different sugarcane clones use about 350 kg of N per hectare (312.3 lbs per acre). “So there is a significant reduction in the production cost because of that.”

The examples of the sugarcane and the grafted plants underscore the assertion that it would be advantageous to know “who” is in the soil. In his effort to identify the millions of bacteria in the soils, Lazarovits is working with Dr. Sean Hemmingsen of the Plant Biotechnology Institute, which is part of the National Research Council in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Dr. Hemmingsen has developed a DNA technology that Lazarovits says can produce a fingerprint of all the organisms that may be present in the soil. “It’s new technology that has never been done before; anywhere in the world.”

The researchers have analyzed two Canadian soils; a sample from Prince Edward Island and one from Ontario. They examined the organisms that are living on the roots and the ones that are living in the soil close to the roots. Lazarovits says they found that organisms on the roots

Nevertheless, the issue of the number of varieties in the collection is less critical than the variability of the genetics in the collection. Richards explains that, by their nature, potatoes do not have a great amount of genetic variability. Unlike a cereal crop, which may have a wide rage of genetic variability, potatoes have many similar DNA characteristics. “Breeders need to be aware of this when they are selecting clones for breeding purposes,” Richards continues. “They need to be selecting genetic material that is not close to the genetics they are working with.” He cites the Irish potato famine as an example of the close genetic relationships between varieties. The Irish farmers were growing varieties genetically uniform and susceptible when a pandemic of a disease, late blight, wiped out the potato crop of Europe and North America.

This phenomenon is commonly called genetic vulnerability. Two factors influence the degree of vulnerability: the relative areas devoted to each variety and the degree of uniformity or relatedness between varieties. “It is only possible to improve genetics within the limits of the material that is available,” Richards explains.

To this end, Potato Gene Resources has a good collection of varieties adapted to the Canadian climate, but breeders may need to access varieties from CIP or the United States in order to increase the genetic diversity within their programs. Fortunately, he adds, Canada’s breeders do frequently go to these other collections to access traits that might not be available in Canada’s “bank.” With a growing emphasis on breeding varieties that have specific traits, such as drought tolerance or

disease resistance, there may be a limited amount of germplasm in the world to achieve the desired goal due to the narrowness of the genetic variation in the crop as a whole. Even though there are red, blue and white potatoes, and some are round and others are long and narrow, their invisible DNA could be very similar.

Meanwhile, Pittenger believes that Canada’s collection of potato clones needs to be protected so it is available to breeders to learn about traits that may not known or are yet to be appreciated or needed “I think the missing link is that more of the potato clones need to be in the seed potato system and then evaluation of the varieties could be beefed up so we know what we have,” Pittenger suggests. “Because most of the materials in the gene resources collection are adapted to Canada,” Dr. Richards continues, “it could become more valuable in the near future because we may have to start breeding to meet the challenges of climate change.” He says he would like to see a screening test developed to evaluate the collection for drought tolerance, which would be added to the list of traits that is available for each clone in the collection.

In the end, the number of clones in the collection is not the real issue. The difficulty is maintaining a collection that is well suited to Canada, but that may not have the diversity of genetics that is really needed to breed the varieties that are required by the industry. Support from the seed industry and growers would not only increase the knowledge of the many heritage and Canadian varieties that are held in the collection, but could also be of assistance in maintaining a more genetically diverse collection of seed stock. n

When you live agriculture, you see things differently Canadian producers know they’re part of something special. In fact, they’re feeding the world. These entrepreneurs rely on people who understand that agriculture is unique. FCC financing is designed for them. Agriculture is life www.fcc.ca/advancing

Research on the control of late blight, in addition to work on identifying the various bacteria in soil is all part of a cluster of projects, with funding from the “Growing Forward” initiative.

Amidst just a handful of soil and residue are millions of bacteria, some that actually encourage growth in some plants, and do not impede it.

are vastly different from the organisms in the soil. “There is some selection of the microbes that are on the root versus what’s in the soil. And we can now identify those guys, pull them out and potentially test them for what benefits they may have for the plant.”

Ultimately, Lazarovits says he is trying to find a low-cost management system for growers that will allow them to shift their soils into what he calls highly productive ecosystems. “And this, hopefully, will speed up the rate: that we can maybe identify technologies to make soils more fertile and create those kinds of ecosystems where the growers have to put in less fertilizer, they can use some of the microbes that fix nitrogen and release phosphorous and all those things.”

As for the next stages of his research,

Lazarovits says there is the potential to collaborate with Canadian potato breeders who have varieties that grow well on low-fertility soils. He suggests that they will examine them for the presence of beneficial soil organisms. Lazarovits is also trying to secure funding for the research through the federal government’s “Growing Forward” program. The horticulture industry is applying for a potato cluster that would also involve research into late blight and

potato breeding. Lazarovits’ group is focusing on soil health. “We’re looking for soil health indicators for potatoes; those soils where growers get good yields year to year, and they can regulate their input costs with no risk of disastrous crop losses.”

Given that the funding is based on three years, Lazarovits hopes his work, if the proposal is approved, would be incorporated into commercial production within that time frame. n

by Treena Hein

More breeding development hopefully will occur in the near future.

In order to better compete, the Ontario potato industry is keen to have more breeding selection conducted in the province, and prospects for this to be realized are looking bright indeed. “The interest level for this is very strong,” notes Glen Squirrell, current chairperson at the Ontario Potato Board. “The global potato industry is changing very quickly. Markets are becoming more focused on potatoes with special qualities such as low-glycemic index and coloured varieties with high levels of antioxidants. In order to meet the challenges coming from around the world, we need to have varieties that are well adapted to our growing conditions here and meet consumer needs.”

The University of Guelph’s potato breeding program was severely cut back more than 10 years ago, notes Squirrell. He believes support for it was cut when the main breeder retired. “It was very successful, producing the Yukon Gold variety, for instance,” he says.

While Squirrell acknowledges that there is one private breeding program in Ontario (at Sunrise Produce), “we are very

supportive of having the University of Guelph’s program built back up again.” As it stands, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) only provides that institution with funding to test varieties at their final stage of development, basically just before they are selected for commercial production and availability to growers.

Leading the charge to have Ontario potato breeding move “further upstream” in the testing process is Dr. Al Sullivan, a professor in the Department of Plant Agriculture at the University of Guelph. He and his lab technician Vanessa Currie have been involved with the AAFC testing program for about 11 years.

“The material we currently receive is at the Elite breeding level,” explains Sullivan. “It has been tested for adaptation in various locations across the country and those lines that have done well are sent to us for evaluation in the Ontario environment.”

Sullivan would like to work with material that is “further up the selection pipeline,” so to speak. “We will be able to examine earlier generation material from the AAFC breeding centres in Fredericton, New Brunswick, and Lethbridge, Alberta, with the goal of strengthening the development pipeline for

growers here,” he says. “Working with a much broader range of germplasm means selecting from a larger pool of genetic variability to better address Ontario’s market and growing conditions.”

The commercial uptake of AAFC-produced-lines by Ontario growers has been poor because the lines have not delivered well on either of these fronts. “The climate and soils are very different here than the Maritimes or Prairies,” says Sullivan. “It’s a much warmer and more humid climate here than Western or Atlantic Canada, and we have a longer growing season.” He adds, “Whether or not a given cultivar will grow here is not the issue. It’s about how well a cultivar performs and how the qualities of the lines manifest themselves in Ontario.”

Differences conditions, different needs

As with growing conditions, the markets in Ontario are also very different. “The potatoes in Fredericton and Lethbridge are developed with a strong emphasis towards the french-fry market,” notes Sullivan. “Here in Ontario, the markets are for chips as an end-product, and for table stock. In terms of potatoes that meet these demands, growers here haven’t found a great deal of value in the lines we’ve been evaluating.”

Growers have access to details about the lines from annual reports produced by Currie and Sullivan and distributed through the Ontario Potato Board, and can also view them first-hand during annual field days held in Guelph. “It’s therefore safe to say that growers have a fair amount of information about these selections that they can use when making

their decisions,” says Sullivan.

As a plant breeder, Sullivan is ready, willing and able to get started. “Vanessa also provides a great deal of expertise,” he adds, “and the University of Guelph also brings the expertise of several other researchers and research labs to the table.”

A formal initial request to move forward was submitted to AAFC by Sullivan during fall of 2009. It included letters of support from growers, processors, major retailers, the Ontario Potato Board and the Canadian Snack Food Association.

The feedback on the request was positive, Sullivan says. He now has to submit the scientific request, and is already in the process of preparing and submitting funding applications. “AAFC has been very helpful in suggesting possible funding sources for this initiative, including the AAFC Science Cluster,” he says. “This will be a sizable up-scaling of our activities, and that will require a larger budget.”

Sullivan stresses, however, that not just any funding will do. “Success will require ongoing funding,” he notes.

“That may be a challenge to secure. Some of the programs we’re applying to provide one-time funding, which is a good start, but we need long-term financial support. The funding scientific review panels must decide if this is deserving of a higher priority than other ventures they may be evaluating.”

For his part, Squirrell is delighted with how things are progressing. “Growers have a huge interest in using varieties that are better suited to Ontario,” he concludes. “We’re very excited about the steps that have been taken so far on this and look forward to achieving this goal.” n

Considering the high-value nature of potatoes, it is not hard to understand why irrigation is particularly important to potato growers across the country.

Once again, the value of the crop plays into the decision-making process on irrigation, its timing, the equipment used, and the systems used to operate that equipment and monitor the crop’s progress.

As these resources continue to increase both in terms of the number of models available and the hardware and software involved, growers are looking for more quick-reference material to help them make the decisions that are best for their operations.

In this issue of Potatoes in Canada’s, we bring you this edition of our Machinery Manager series,

dealing with irrigation systems. As with our other Machinery Manager features, we have provided valueadded specification highlights and photos. The full specifications are available on our website at www. topcropmanager.com.

I hope you find this information useful and easy to access. At Top Crop Manager, we always advise growers to check with the equipment manufacturers, dealers and other agronomy professionals, for more information that pertains to your own farming operation.

Ralph Pearce Editor Potatoes in Canada

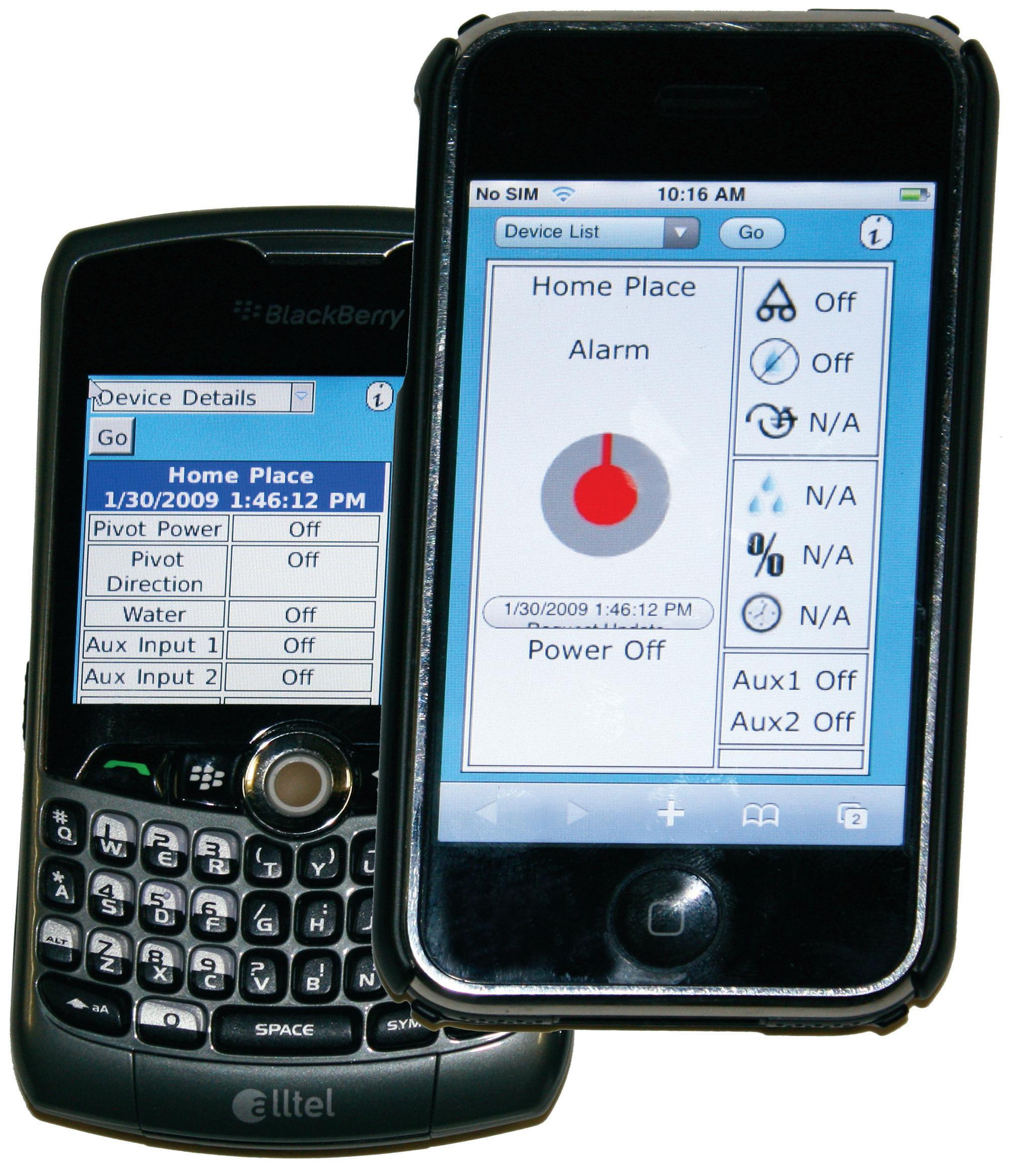

The newest innovation from AgSense is an advanced GPS-driven pivot monitor/control system that communicates via the digital cell network to provide near real-time information and up-to-the-minute alarms to a grower’s cellphone, smart phone or computer.

Field Commander is a GPS-driven pivot controller that communicates via the digital cell network and is loaded with numer ous digital control features that enable a grower to upgrade his pivot without an expensive panel conversion. Field Commander is the first remote pivot controller that works with any brand of pivot and has the ability to remotely monitor and/or control numerous sensors, pumps and meters in the field from a single web page.

Field Commander works via the WagNet (Wireless Ag Network) web portal. WagNet’s revolutionary micro-network communications technology enables a grower to remotely monitor and/or control numerous field operations from a single website for a single low annual service fee. WagNet has a simple, easy to understand user interface that makes it possible to monitor and control all Field Commander and Crop Link devices from virtually anywhere in the world. WagNet features Google Maps and user configurable alarms that put the grower in control of when, why and who should be notified when a problem occurs.

Field Commander works with any brand of pivot and comes loaded with numerous digital control features, allowing growers to upgrade a pivot without replacing the existing control panel.

GPS guidance, digital cell communications, comprehensive reports, historical graphs, up-to-the-minute alarms and the ability to communicate with multiple sensors, meters and pumps makes Field Commander the most complete field management system on the market.

Pivot start/stop Monitor; Control; Graph

Pivot direction Monitor; Control; Graph

Pressure cut off Monitor; Control; Graph

End gun Monitor; Control; Graph

Pivot position Monitor; Graph

Water pressure Monitor; Graph Speed Monitor; Control; Graph

Stop at/by time Monitor; Control; Graph

Communications Cell, smart phone or computer

Compatible pivots Any

Go to www.machinerymanager.ca for further specifications and links to AgSense irrigation equipment.

Lindsay introduces FieldNET with pump control

Lindsay Corporation, maker of Zimmatic irrigation systems, announces the addition of pump control to its awardwinning FieldNET web-based irrigation management system. With this addition, growers will be able to access a single online portal to monitor and control their entire pump and centre pivot irrigation system.

FieldNet is the industry’s first fully-integrated pump and centre pivot irrigation monitoring and control package. For the first time, growers have the ability to use a combination of cutting-edge irrigation and pump control technology, all in one package, to save energy, water and labour costs.

FieldNET, the industry’s first full control web-based irrigation management system, allows growers to monitor and control their pivots from any Internet connection or cellphone. With a user-friendly web portal, FieldNET provides growers a quick view of every pivot, providing information on pivot location, pivot status and water usage.

With FieldNET pump control, growers now have information on their entire water delivery system, allowing them to monitor and maintain each pump and pivot for peak performance. This integrated solution automatically tracks and reports pump start-ups and shutdowns and sends alerts for any disparity of normal operations, such as flow alarms.

FieldNET with pump control is available in two service levels and can be installed on both new and existing Lindsay systems as well as on systems from other manufacturers.

Pivot start/stop Monitor; Control Monitor; Control

Pivot direction Monitor

End

Pivot position

Water

Soft

None

Auto stop/auto reverse None

Programmable

Programmable

Communications Cellphone; computer Cellphone; computer

Compatible pivots Any Any

Go to www.machinerymanager.ca for further specifications and links to Lindsay irrigation equipment

OnTrac Satellite Technology allows installation of pivot control technology in remote areas with poor or no cellular reception, making OnTrac more reliable than cellular-based communications. OnTrac sends alert messages to a choice of cell phone, smart phone, pager, landline phone, or e-mail, or to a combination of all. OnTrac tracks precise system locations when used with the exclusive Reinke Navigator Series of GPS Controls.

The OnTrac technology uses a flexible platform that can be configured to meet the needs of irrigators. With the addition of other technology options, such as GPS and other controllers, the OnTrac system can be built to provide the type of control individual irrigators require.

OnTrac eliminates signal reception issues caused by tall crops, terrain or buildings, and allows users to view system status and history via the Internet.

System updates and alerts can be received via text messages, or by voice alerts over cellphones. Alert messages can also be quickly and conveniently sent to a pager. With a PDA or smart phone and an Internet connection, the system status can be viewed on the web, and change of status information can be sent to the user’s e-mail address.

OnTrac also allows the operator to view system status and location from anywhere in the world via a secure OnTrac web site.

Options available include pressure monitoring, position reporting on the Internet using exclusive Reinke Navigator GPS technology, and rainfall reporting over the Internet and to cellphones, PDAs, and pagers.

Pivot start/stop

Pivot direction

Monitor; Control optional

Monitor: Control optional

Water on/off Optional

End gun

Monitor; Control optional

Pivot position Optional

Water pressure Optional

Soft barriers

Auto stop/auto reverse

Communications

Monitor: Control optional

Monitor: Control optional

Cellphone; Handheld computers

Compatible pivots Any

Go to www.machinerymanager.ca for further specifications and links to Reinke irrigation equipment.

As fuel and labour costs continue to rise and water availability lessens, more farmers will need Remote Monitoring and Control Products to help manage their irrigation operation. With the Valley BaseStation2-SM and the Valley Tracker product line, there are many Valley products that can help farmers minimize their costs and maximize their profitability.

The custom designed Valley BaseStation2-SM is a reliable and complete remote monitoring and control solution as it works with any Valley pivot or linear as well as non-Valley machines. This complete irrigation management solution communicates using VHF/UHF data radios with pumps and valves as well as monitors soil moisture, pressure transducers, temperature sensors and flow meters. A dedicated computer is in constant communication with irrigation equipment to provide real-time updates on equipment status. There are no monthly fees associated with the BaseStation2-SM as the grower owns everything.

The Tracker product line also works with any Valley pivot and non-Valley machines. The Valley TrackerSP, Tracker2 and TrackerLT each offer different levels of management allowing the grower to find a solution to fit his needs. They use digital cellular modems and provide the basic remote monitoring and control functions. The Tracker management functions are accessible though the Internet or cellular phone. Because it uses digital cellular modems, monthly service fees apply.

Pivot start/stop Remote stop Remote control Remote control Remote control

Pivot direction Monitor Monitor; Control Monitor; Control Monitor; Control

Water on/off Monitor Monitor Monitor; Control Monitor; Control

End gun Monitor Monitor Monitor; Control

Pivot position Monitor Monitor Monitor Monitor