With the FLIR C5 in your pocket, you’ll be ready anytime to nd issues with pumps, belts, valves, and motors. The C5 is packed with professional features that make it easier to inspect and nd hidden problems, document issues, share results with customers – and keep the production line going.

MONTH 2019

SEPTEMBER 2020

Vol. 36, No. 4

Established 1985

Vol. 35, No. X Established 1985 www.mromagazine.com

www.mromagazine.com

Twitter: @mro_maintenance

Twitter: @mro_maintenance

Instagram: @mromagazine

Instagram: @mromagazine

Facebook: @MROMagazine linkedin.com/company/mro-magazine

Mario Cywinski, Editor 226-931-4194 mcywinski@annexbusinessmedia.com

Contributors

IMario Cywinski, Editor 226-931-4194 mcywinski@annexbusinessmedia.com

Bryan Christiansen, Ted Cowie, L. Tex Leugner, Douglas Martin, Doc Palmer, Peter Phillips, David Rizzo, Brooke Smith

Michael King, Publisher 416-510-5107 mking@annexbusinessmedia.com

Contributors

John Lambert, L. Tex Leugner, Douglas Martin, Doc Palmer, Peter Phillips, Darryl Purificati, Melissa Schmidt

Mark Ryan, Media Designer

Barb Vowles, Account Co-ordinator 416-510-5103 bvowles@annexbusinessmedia.com

Paul Burton, Senior Publisher 416-510-6756 pburton@annexbusinessmedia.com

Beata Olechnowicz, Circulation Manager 416-442-5600 x3543 bolechnowicz@annexbusinessmedia.com

Graham Jeffrey, Media Designer

Barb Vowles, Account Co-ordinator 416-510-5103 bvowles@annexbusinessmedia.com

Tim Dimopoulos, Vice-President tdimopoulos@annexbusinessmedia.com

Scott Jamieson, COO sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Beata Olechnowicz, Circulation Manager 416-442-5600 x3543 bolechnowicz@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mike Fredericks, President & CEO

Machinery and Equipment MRO is published by Annex

Scott Jamieson, COO sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mike Fredericks, President & CEO

Business Media, 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto ON M2H 3R1; Tel. 416-442-5600, Fax 416-510-5140. Toll-free: 1-800-268-7742 in Canada, 1-800-387-0273 in the USA.

Machinery and Equipment MRO is published by Annex

Printed in Canada

ISSN 0831-8603 (print); ISSN 1923-3698 (digital) PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Business Media, 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto ON M2H 3R1; Tel. 416-442-5600, Fax 416-510-5140. Toll-free: 1-800-268-7742 in Canada, 1-800-387-0273 in the USA.

Printed in Canada

CIRCULATION

E-mail: bolechnowicz@annexbusinessmedia.com

ISSN 0831-8603 (print); ISSN 1923-3698 (digital)

Tel: 416-510-5182 Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto ON M2H 3R1

CIRCULATION

Subscription rates.

E-mail: bolechnowicz@annexbusinessmedia.com

Canada: 1 year $65, 2 years $110 United States: 1 year $110

Tel: 416-510-5182 Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto ON M2H 3R1

Elsewhere: 1 year $126 Single copies $10 (Canada), $16.50 (U.S.), $21.50 (other). Add applicable taxes to all rates.

Subscription rates.

Canada: 1 year $65, 2 years $110. United States: 1 year $110. Elsewhere: 1 year $126. Single copies $10 (Canada), $16.50 (U.S.), $21.50 (other). Add applicable taxes to all rates.

On occasion, our subscription list is made available to organizations whose products or services may be of interest to our readers. If you would prefer not to receive such information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer

Privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com, 800-668-2374

On occasion, our subscription list is made available to organizations whose products or services may be of interest to our readers. If you would prefer not to receive such information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer

Privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com, 1-800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2019 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2020 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily

n August, Maintenance and Equipment MRO magazine conducted its first-ever Maintenance and Reliability in a Changed World Virtual Summit. As the world has changed to a 'new normal' of no live events for the foreseeable future, we wanted to stage an event that would allow MRO professionals to virtually meet, and to learn from industry experts. Given the response that we got from a endees and presenters alike, I would say that we achieved that goal. A li le nerve-wracking, but not bad considering this was my first time hosting a summit.

We were very fortunate to have included two well-known industry professionals as part of the program. Suzane Greeman, who spoke about Executive Leadership in Asset Management: What The C-Suite Needs to Know, and James Reyes-Picknell, who spoke about The New Normal for Continual Improvement, gave great presentations that fielded numerous questions, and provided insights that attendees could take back to their companies. Also, an open panel discussion included representatives from a cross-section of MRO companies that operate in Canada (and some globally).

Overall, it was great to see the level of engagement from maintenance, reliability, repair, asset management, operations, and many other a endees from various aspects of the MRO world. It proved that just because we are not able to meet face-to-face, we can still share valuable information that can help others in the industry continue to learn and improve their operations.

It was also interesting to find out, by way of using polls during the summit, where companies stand currently. When asked "What is your biggest challenge to improving future performance?" Lack of leadership fore-sight was the most common challenge at 42 per cent, followed by: recovering from current measures (38 per cent), availability of investment funding (15 per cent), and don't believe we need it (four per cent). When asked "What roles do the executives and board play in the asset management system currently?" Executives are aware, but not sure about the board; and we don't yet have an AMS, tied with 31 per cent each, followed by active involvement, executive sponsorship, authorization, promotion (24 per cent), and we have a system, but no involvement from either (14 per cent).

The final poll question during the open discussion, "What changes has your organization seen as a result of COVID-19?" Showed that 67 per cent of a endees have seen, changes to work (remote work) as the number one answer, followed by production slowdown/stoppage (28 per cent), and staff reductions/layoffs (six per cent). This is something that has been seen all over the work spectrum, as we are learning what the new normal is (will be) and employers and employee are adapting to what the future will hold. For some this is working from home, for others its working at an office with physical distancing, or staggered a endance.

For anyone who has any ideas about any topics that we should cover in an upcoming webinar; episode of In Conversation with Mr. O podcast; virtual event; or MRO, Food and Beverage or online feature; do not hesitate to reach out to me via e-mail, social media, or the old fashion phone call. Yes I do still take phone calls.

Gain operational insight like never before with SKF Pulse.

The SKF Pulse portable, Bluetooth™ sensor and free mobile app help you predict machinery issues before operations are impacted. Monitor vibration and temperature data on your rotating equipment, without the need for training or diagnostic expertise.

Tap into decades of SKF predictive maintenance and rotating machinery analysis expertise through SKF

Rotating Equipment Performance Centers, dedicated to improving your operation and finding solutions for every performance challenge.

SKF is your partner in moving toward a digital future. Visit skf.ca/skfpulse to see how SKF Pulse can improve your operation.

Contact your SKF authorized distributor for a quote today. You will be surprised how cost effective SKF Pulse is.

An Opportunity for a Culture Change / 8

During these uncertain times it is quite interesting to see how different people react to the circumstances we are in.

What’s Up Doug / 10

Focus on magnetism and bearings.

Courage to Transform and Challenging the Status Quo / 12

In a dynamic competitive environment, standing still, means falling behind.

MRO Quiz / 16

Troubleshooting rotating mechanical equipment using vibration analysis.

Maintenance Scheduling / 18

Weekly schedule compliance is an easy tool but a bit tricky.

How to Spot the Signs of Mechanical Failure / 20

By the time mechanical failures or maintenance issues are spotted, they’re often already too serious or expensive to repair.

Maintenance 101 / 22

Performing repair and maintenance during COVID-19.

MRO Virtual Event / 26

MRO Magazine recently held its rstever Maintenance and Reliability in a Changed World Virtual Summit.

Editor’s Notebook / 3

Industry Newswatch / 6

Mr. O / 30

What’s New in Products / 28

Ford Motor Company’s new four-legged doglike robots can perform 360-degree camera scans, handle 30-degree grades and climb stairs for hours at a time.

Part of a Ford manufacturing pilot program, at the Van Dyke Transmission Plant, designed to save time, reduce cost and increase efficiency. The two robots are being leased from Boston Dynamics. The robots are bright yellow, equipped with five cameras,

can travel up to three miles per hour on a ba ery lasting nearly two hours.

The robots scan the plant floor and assist engineers in updating original computer aided designs, which is utilized when retooling Ford plants. It costs nearly $300,000 to scan one facility. Ford’s manufacturing team hopes it can scan all its plants for a fraction of the cost.

The intent is to be able to operate the robots remotely, programming them for

plant missions and receiving reports immediately from anywhere in the country. Right now the robots can be programmed to follow a specific path and can be operated from up to 50 metres away with the out-of-the-box tablet application.

The robots have three operational gaits, a walk for stable ground, an amble for uneven terrain, and a special speed for stairs. They can change positions from a crouch to a stretch, which allows them to be deployed to difficult-to-reach areas within the plant. They can handle tough terrain, from grates to steps to 30-degree inclines. If they fall, they can right themselves. They maintain a safe, set distance from objects to prevent collisions. MRO

Waterloo-based The Canadian Shieldis donating 750,000 reusable face shields to provincial and territorial governments across Canada, to be distributed to protect teachers and educators from potential exposure to COVID-19.

It began manufacturing face shields in March 2020, at the time it made a call to the community for help in 3D printing the visors. Dozens of school boards from across Canada offered support, and the company was able to donate 20,000 shields to healthcare workers.

The Canadian Shield is also launching kids face shields. They have been modified to fit children aged five to 12 years old. It began producing kids shields a er receiving feedback from customers seeking a suitable face shield option for children under 12.

It has also launched cloth and surgical mask lines, now producing one million surgical masks per week and planning on an annual quota of over 300 million masks. In the next few months, the company will begin manufacturing isolation gowns, with an anticipated capacity of six million gowns per year. MRO

MRO magazine’s weekly e-newsletter provides you with special articles and updates on news, maintenance products, and operating tools - right in your inbox.

MRO o ers the most recent maintenance, reliability, and operations information on social networks.

Follow us on these platforms for the latest news, features, and product information.

MRO also produces the “In Conversation with Mr. O” podcast. Topics include safety, maintenance and reliability, and scheduling and planning.

During these uncertain times it is quite interesting to see how different people react to the circumstances we are in. Like any situation – some people have a glass half full, some a glass half empty. However, we need both types of people in the workplace. One may be overly enthusiastic, while another has a more conservative approach. For an individual, we say it's the nature of a person.

BY JOHN LAMBERT

Collectively, in a plant’s maintenance group, we call it the culture of the group. Culture being the behaviours, beliefs, and values, they share as a group. Most maintenance groups, have at least two or three cultures, even though they are one group. There is (upper) management culture - plant, production, maintenance, engineering, and reliability managers. Next, middle manager culture – with supervisors, foreman, planners and leadhands, these are the front-line supervisors. Finally, the shopfloor group culture - made up of trades/cra smen, millwrights, labourers, and lube techs. In some organizations they can work effectively together; in others they don’t. It becomes an “us and them” situation. It is usually at least two camps.

We see this “us and them” mentality a lot during precision maintenance and machinery installation training. For example, it's a rarity for front-line supervision or management to sit in on training programs. When the doors are closed and it's just the tradesmen/women, it begins with “we just do what we're told,” but by the end of the day we have learned to trust one another and more of the true culture of the shop-floor group comes out. Like most people, they like an opportunity to vent to someone who understands their issues.

Personally, I was a maintenance mechanic/millwright and worked as a maintenance lead-

hand, foreman, supervisor, and a training instructor. Therefore, I understand tradesmen/women’s concerns, and concerns of the front-line supervision. The underlying tradesmen/women concerns are: they are not supported, they are not listened to, and are not involved.

Being between upper management and the tradesmen is not easy. For example, one of the reasons they do not sit in on the training is because someone will bring up a situation where a machine was not correctly repaired yet was put back into service. There could be several valid (or not) reasons that the machine was put back in service.

Therefore, an opportunity is coming, as there will be a roll back in maintenance budgets, because most companies will lose revenue with this pandemic. There should be no surprise if staff is cut back. It’s unfortunate, but it’s reality. The reason why is maintenance is the easiest budget to control and reduce. The opportunity is being able to work together. It’s understanding that the most important thing is to get the job done as efficiently as possible. Use the skills that we have, not only to maintain but to improve.

Now is the time to build the team, because we are “all in this together” and we need each other. A simple way to start is by implementing a precision maintenance program. With precision maintenance you concentrate on ensuring failure prevention and defect elimination in the tasks performed on your machines and equipment by your maintenance and operations people. We train on this and we call it Measure, Analyze, Act and Document (MAAD).

The MAAD concept can be used by

anyone in the maintenance and reliability industry when trying to improve your maintenance processes. It is also a method that we promote and believe should be followed whether you’re a millwright, mechanic, maintenance manager, supervisor, or reliability expert involved in machinery installation.

Measurement: find a simple and effective way to measure your processes (to control a process, you have to measure it).

Analyze: the issue as a group. Asking the question “why”and you need truthful, honest answers from everyone.

Act: if necessary.

Documentation: If you don’t document and you need to look back to analyze, you are only guessing as to what happened.

You can keep this process as simple as you want. For example, you could review and measure the effectiveness of your PM program. The action taken may be to rewrite the PM but whoever does the actual work should be involved with the re-write.

Sometimes a dynamic individual or program can change the culture of a work group but remember, it takes a team to sustain it. To move ourselves forward from this pandemic we will need our communities inside and out of the workplace to work together and build a stronger culture. MRO

John Lambert is the President of BENCHMARK PDM. He can be reached at john@ benchmarkpdm.com.

Calling this article, “heavy industry greasing” or “heavy industry oiling” would work, as the real issue is not “lubricating” rolling element bearings, but about preventing the effects of a contaminated environment, or controlling the bearing operating temperature.

BY DOUGLAS MARTIN

An example that defines the difference between “lubricating” and “greasing” is: an experiment done by E.R. Booser, research scientist, who operated a ball bearing with only two initial drops of oil. The bearing was running at 36,000 rpm for two weeks at a temperature of 100C before encountering failures. The question then is, how much oil is needed for lubrication? In this case, the bearing would have continued to run if one drop of oil was added once a week.

An example, once the grease has been added to the bearing, and the rolling element has created its “channel” in the grease, there is a very small amount of oil that bleeds into the lubricating gap. If the channel remains stable, and is always able bleed oil into the gap, all is good. There are many “sealed for life” bearings in industrial se ings (such as electric motors).

Looking at a 50hp motor that has sealed for life bearings, and an 1-15/16” sha unit block ball bearing on a conveyor. Both bearings have the same insides, 6210.2RSR bearing in the motor has the same size balls and race diameters as P2BL-115WF unit block. The unit block rotates at 100rpm on a dusty conveyor and the motor that drives the same conveyor rotates at 1750 rpm, but bearings are inside a cavity with a labyrinth seal, and a grease pack protecting the sealed bearing.

The slow-moving unit block bearing gets greased once a month, and the motor bearing never gets greased. If this was

about lubrication, the motor bearings should get greased more o en than the unit blocks, but it is the opposite, why? Since we are not lubricating the unit block bearing, we are enhancing the “sealing” of the unit block bearing by re-greasing.

Therefore, what are the key “re-greasing” factors?

There are essentially two methodologies of sealing a bearing and/or its cavity; lip contact seal, and labyrinth seal.

With a lip contact seal, the primary role is to keep the good grease (or oil) in the bearing (area). With a lip seal integrated into the bearing its purpose is to keep the good grease in the rolling contact area. In most cases, an external sealing mechanism like a labyrinth or flinger provides protection against contamination and a space between the bearing and outer seals that contains grease.

With a labyrinth seal, the grease is expected to flow though the bearing (or housing) and out the labyrinths carrying away contamination. If properly greased, the labyrinth seal should always have a bead of fresh grease at its external opening.

There are no common calculations that can determine how much grease is needed for labyrinth seals as there are many variables. Such as: operating temperature, NLGI number of the grease used, speed of the application, degree of contamination, and amount of vibration in the machine application.

The proper amount of grease needs to be determined by visual observation and adjustment by the lubrication technicians.

NLGI number

NLGI number is a measure of the stiffness of grease. Typical bearing grease is NLGI 2. People may say, “we use an EP 2 grease.” Meaning, a grease with EP additives with NLGI number 2. In vertical applications and applications with higher machine vibration, NLGI 3 is used to help the grease stay in place.

O en in automated lube systems, an NLGI 1 or 1.5 is used to help get the grease to the greasing point. In truck chassis lubrication, there are cases where an NLGI 0 or 00 outperforms an EP 2 shop grease. Why? Since this application is on an auto-lube system, there is always some amount of grease going to the application. The NLGI 2, which is stiffer, gets to the application and stays there. While there, it collects dust, and as the application moves, the dirty NLGI 2 grease pulls contamination into the lubricating gap and causes wear. The NLGI 0 grease is easily displaced and falls away from the application taking away the contamination.

Compared to a standard NLGI 2 grease:

NLGI 3 - stays in place under adverse conditions.

NLGI 1.5 - Is more readily pumpable in an automated lubrication system.

NLGI 0 (or 00) - will easily sluff away taking with it contamination.

When facing challenging contamination conditions, perhaps a change in NLGI number may provide a be er sealing grease.

How much grease should surround a bearing in a housing/pillow block? The housing fill is a function of bearing operating speed and by relationship, how o en the bearing will be re-lubricated. Higher speed applications should be initially packed with less grease, knowing that the re-lubrication frequency may be short. Whereas in slow applications, the housings can be packed fuller, knowing that the need for fresh grease is longer. However, there need to be a sealing barrier as provided by the grease in the housing and the subsequent replenishing of grease (for exclusion of contamination).

Therefore, one may specify the same re-greasing frequency for the same size bearing, one in a fan, and one in a conveyor pulley. With the fan, the demand for fresh grease is governed by the grease life due to the higher speed and higher operating speed, which reduces the life of the grease. Whereas the conveyor will demand fresh grease due to the contamination level of the environment. Fresh grease is intended to carry away the contamination.

In the case of the fan, start with a low housing fill, knowing that more grease is coming, and an excessive amount of grease will lead to the bearing overheating. In the case of the conveyor, we are not concerned about the bearing overheating (due to the slow speed) and the housing can be nearly full, and the added grease is intended to get pushed out of the housing carrying contamination away.

Also, over-greasing is when there is more grease added at a rate that exceeds the ability of the bearing cavity purge. For example,

in a case with an electric motor, there was a grease drain that had to be opened prior to re-lubrication. On a regular routine, grease was added, with the port open and then the technician, a er greasing would replace the drain port. One day, a new technician added grease but was not aware of the grease port and did not open it. The bearing soon failed from excessive greasing. However, the same amount of grease was added at the same frequency. The only thing that changed was that the bearing cavity was not able to purge the grease at the rate that it was added.

Thus, it is not the bearing itself that is over greased, it is the bearing assembly that is over greased. Unfortunately, many still believe over greasing a bearing is bad, without understanding that it is over greasing the bearing assembly per se.

Once a bearing is going slow enough, it can no longer form a lubricating film that fully separates its contact surfaces. As a rule, once the surface speed falls below 20,000 mm/min, solid additives such as graphite or molybdenum are suggested, as there will otherwise be metal to metal contact due to a lack of oil film. For a 300mm bearing, such as a 23060 CC/W33, this is about 70rpm.

In terms of oil, we need to recall that a bearing needs only a few drops of oil to operate for some time. For heavy industrial applications, oil can be used to transport away contaminants to a se ling tank (reservoir) and filtration.

The primary role of additional oil flow is the control of the bearing operating temperature. The flow rate of the oil is based on maintaining the optimum oil temperature such that the delivered oil viscosity can create an oil film. This is a difficult value to calculate what actual flow rate is needed as there are so many variables in a heat transfer calculation. The appropriate oil flow is determined by first determining the appropriate target temperature, then by adjusting the flow to achieve that temperature. Of course, process changes and startup behavior, throw a wrench into the needed operating temperature of oil.

Adding grease and oil flow to a bearing is more than just satisfying a lubrication requirement. It is how the user of the equipment ensures the optimum bearing operating temperature for maximum bearing life (in the case of oil) and how the user can keep the optimum cleanliness in the bearing, for maximum bearing life. MRO

Douglas Martin is a heavy-duty machinery engineer based in Vancouver. He specializes in the design of rotating equipment, failure analysis, and lubrication. Reach him by email at mro.whats.up.doug@gmail.com.

In a dynamic competitive environment, standing still, means falling behind.

BY MELISSA SCHMIDT

For a service organization, a consistent customer experience may be rewarded with customer loyalty, important in a competitive market. Courage to challenge traditional long held beliefs and a historic operating model has helped Finning (Canada) undergo a transformation that improves the customer experience, while remaining agile for a quick response required for customers who navigate cyclical demand. Customer feedback is captured regu-

larly, which places their experience in the driver’s seat. As customers adapted their business models to remain competitive,

Finning (Canada) would need to do the same. The feedback was clear, customers were counting on Finning (Canada) to

remain focused on consistently ge ing their equipment back to work quickly. We acknowledged that making continued improvements for customers meant a revitalization of our operating model.

Revising the business model required the organization to identify potential bo lenecks that could interfere with repair efficiency. It was critical that work be distributed in a way that would minimize accumulations of backlog. Quality standards had to be maintained which prompted the review of the existing allocation of tooling, parts inventory, fleet, and employee development. Technology would be key in connecting with the customer through the repair journey. Adoption of the change would require performance measures that would complement the change.

With the vision of transformation clear, the operating model was adapted to a network design that closely resembles that of a hub and spoke model. This model has specific benefits for service providers. Infrastructure and talent are organized into a series of spokes that offer rapid response services and hubs that offer a full menu of repair and rebuild services.

Spokes focus on the quick response to the initial customer needs, offering a timely triage and immediate small-scale general repairs. Customers are no longer stuck in a long queue waiting for their work to be done. Hubs provide support for the network for larger and more complex repairs. Standardization is used in the hubs to gain greater efficiency through economies of scale and consistent quality. When required, a repair is moved through the network based on the available capacity and capability to perform the work within the hub facilities. This network scheduling approach is the catalyst for tapping into the full capacity and capability of the network. The movement of work through the network is critical in maintaining rapid response in our spoke facilities. If they are tied up with lengthy repairs, we risk of a delay to the customer.

Identifying which locations would be rapid response spokes,

and which would be support hubs was done by assessing feasibility factors such as availability of local talent, competitive operating costs, location relative to demand and existing facility infrastructure.

Throughout the design, there was keen a ention on identifying both tangible and intangible benefits. Priority to improve the less tangible customer loyalty and employee engagement was shared with the need to improve the tangible asset utilization, market share and growth.

Network scheduling manages fluctuations in volume tapping into underutilized resources. Whether it’s people or

hard assets, the increased utilization improves employee engagement and reduces cost. Engagement increases when there is enough work to go around. Managing demand for overtime supports engagement when employees can find a comfortable work life balance. The cost for idle mechanical hours, not billable, are reduced when all available resources are used for scheduling.

The skill set required in a spoke facility is broad to respond to all events, whereas the hubs have scale, and so can specialize. This is a considerable pivot from our former model where all facilities required

both skill sets. With clear definition between broad response technician and specialists, we needed to update our training strategy to align with the new approach and market population, needed to be updated. This also creates an opportunity to expand the training offerings to include content that focuses on customer relations. The result is an efficient use of our training resources and a well prepared, competent work force.

The broad response technician and specialist differentiation provide additional benefits with tooling investment. Spoke facilities are outfi ed with tooling suited to the customer facing rapid response work, leaving the specialty, often expensive, tooling to be allocated to hub facilities. As tool inventories come together, there is the additional one-time benefit from the sale of surplus tooling.

Adjusting parts inventory within the network to align with the prescribed work scope eliminates redundant inventory and creates the financial and infrastructure capacity for more suitable inventory. With order fulfillment an important measurement of working capital performance, this benefit gains a lot of a ention.

Hub facilities have a greater opportunity to become more efficient through scale and repetition of the complex repairs. Repetition coupled with standardization will reduce the average number of days for the repairs. Work is done quicker, which means additional work can be performed, generating more revenue. Ge ing the repairs done right the first time reduces expense related to service redo. We have a service process that complements the standardization, managing work flow, and pro-actively identifying risk. All have a direct relationship to the customer experience. With the undeniable benefits, the focus shi ed to implementation.

This new model had widespread impacts throughout the organization. Every aspect from incentives, to inventory, to tooling had to be considered. Engaging with every department in the organization has led to the creation of a cross-functional implementation plan. The plan considers infrastructure and talent simultaneously.

The extensive facility infrastructure already in place needed to be used differently. Additionally, the current state for each location was captured during the design phase. A gap assessment was used

to identify where infrastructure investment was required. Common gaps identified were related to internal fleet, tooling, and shop space. Sourcing underutilized assets, increasing capacity by implementing additional shi s, and capital spend helped to close the infrastructure gaps.

With the infrastructure in place, the focus shi ed to preparing people for this change. The support and understanding of all employees were instrumental. Challenging traditional culture is never easy, as we were asking employees to remove the wellworn comfortable “location hat” and embrace the “One Finning Network chapeau.”

Creating a common understanding of the “burning platform” and the benefits of this transformation was the first step. Using multiple mediums such as videos, storytelling, toolbox talks, and online resources, the communication and education began. It was important that everyone understood that for Finning (Canada) to remain a competitive player, we needed to make a significant and major change. As the audience received the message, the points of resistance began to surface. Exploring these resistance points helped to form the change management plan.

The immediate question of who would pay the added cost to move equipment needed to be answered. Customers should not be expected to bear the cost of changes to Finning's processes, unless there is increased value to them. To balance urgency and cost, we revised existing transportation routes were revised using a combination of planned and unplanned routes. Costs to transport equipment are offset by increased revenue opportunities, re-allocation of underutilized resources, and efficiency.

Having the right parts on hand to repair equipment supports front-line workers. Nervousness surfaced that the inventory adjustments would be made based on dollars and cents, not what was required to meet the customer needs. Using a regional planning approach, optimal inventory levels were determined that factored unique needs. An example, it was recognizing that British Columbia has a higher number of forestry machines, that needed to be realized in the inventory levels.

Concerns arose that opportunities to develop diverse skills supporting succession would be limited. Confidence that employee development remained a priority, needs to be created. Skills will

continue to be developed through temporary work assignments and employee driven development plans. Specific learning paths are available to outline the path from a generalist to specialist, and vice versa. While the initial focus of the training resources is to prepare the network up to succeed, it serves Finning (Canada) in preparing for future demand.

Similarly, recruitment efforts would need to focus on identifying talent that is adaptable within the network. Potential candidates need to understand how the operating model aligns with their career objectives. This is particularly important for our apprenticeship program. In order to gain diverse experience in the apprenticeship program, it may be necessary to work from multiple locations.

A well thought out design is only valuable if put into practice. Old habits take time to change. In the past, incentives were based on the performance of an individual location. This led to relationship-based decisions that did not always result in the best customer experience. To change this behavior job profiles were revised to increase accountability for customer-centricity. Equally, incentive

models were updated to reward performance of the broader network. With an informed and incentivized work force, compliance to the operating model will be further embedded through continued education, auditing and reporting.

Finning (Canada) embarked on this journey to improve the customer experience and improve employee engagement. As a result, customers have taken note and embraced the changes. It has evolved from fragmented supplier to a trusted partner. While it will take continued effort to adopt the operating model, employees seeing the network in action are becoming change ambassadors. In the service industry, happy employees help to make happy customers. MRO

Melissa Schmidt, MMP, has had a diverse career in the oil and gas sector, primarily in heavy equipment. A passion for continuous improvement and innovation led her to the MMP Program in 2011. A 20-year career with a single organization has provided her with ample opportunity to test the practical application of maintenance principles. Working with PEMAC provides her with an opportunity to keep learning through their network of professionals.

BY L. (TEX) LEUGNER

Vibration is technically defined as the oscillation of an object about its position of rest. These oscillations are responses to mechanical forces symptomatic of a problem. Before we discuss the technology as a troubleshooting tool, a review of terminology is important.

Frequency refers to “how many” of these oscillations in a given length of time (e.g., one minute), measured in cycles per minute (CPM), or cycles per second (Hertz) Hz, related to 1X sha turning speed.

Displacement refers to amplitude and “how much” the object is vibrating measured in Mils (1/1000 inch) peak to peak. Displacement (distance or movement) is generally the best parameter to use for very low frequency measurements (i.e., less than 600 cpm), where velocity and acceleration amplitudes are extremely low. Displacement is also traditionally used for machine balancing at speeds up to 10,000 or 20,000 rpm and where clearances are important criteria.

Velocity indicates “how fast” the object is vibrating measured in inches/second or mm/second peak. Velocity is frequently used for machinery vibration analysis where important frequencies lie in the 600 to 60,000 cpm range. For most machines, mechanical condition is most closely associated with vibration velocity,

which is a measure of energy dissipated and consequent fatigue of machinery components. Overall velocity is also best for detecting a wide variety of different machinery defects occurring at the mid-frequency range.

Acceleration of the object that is vibrating is related to the forces that are causing the vibration measured in “gs” (1g = 32 /sec2 or 9.8 m/sec2) and is reported or shown as root mean squared (RMS). Acceleration (force) is best measured when it is known that all the troublesome vibrations occur at high frequencies, that is, above 60,000 cpm. For example, in detecting high frequency turbine blade vibration in the presence of many low frequency vibrations, acceleration will assist in emphasizing the high frequencies. It is important to remember that when using various transducers to monitor vibration, velocity leads displacement by 90 degrees and acceleration leads velocity by 90 degrees and displacement by 180 degrees.

Vibration analysis should be part of any equipment reliability management program, but what must first be determined are which machines should be monitored and how o en monitoring should take place using the formula:

MACHINE PRIORITY = CRITICALITY X RELIABILITY.

Where criticality is the importance of the machine to production goals; and where reliability is a result of a review of the “probability of failure” based on history of machine repair.

1. How o en should your facility apply vibration analysis?

Logic: machines that are operated under proper conditions and are considered reliable with a satisfactory maintenance history may require quarterly vibration monitoring, depending upon their criticality. Others may require monitoring on a weekly basis due to high production demands, or which might create a safety or environmental hazard. Machines that exhibit serious problems may require monitoring daily or hourly, until repairs can be planned, scheduled, and executed.

2. How does your facility determine the correct selection and application of transducers?

Logic: the quality of the data gathered by vibration analysis is directly dependent upon proper selection and mounting of the transducer. If possible, vibration readings should be taken with the transducer mounted perpendicular to the surface of interest in horizontal, vertical, and axial directions. Vibration signals containing “high frequencies” must be taken with an accelerometer tightly screwed, or glued to the surface, since hand-held pressure alone cannot hold it tightly enough to the surface for it to obtain high frequency motion.

Displacement non-contact proximeters are used to look directly at the rotating sha s of machinery, and the frequencies obtained will be quite low. Accelerometers have the advantage of having adequate sensitivity over a wide range of frequencies. The low end is typically one to three Hz, while the upper range can be as high as 20 kHz. For this reason, accelerometers are the preferred device to use.

3. Do your facilities vibration analysts understand the causes of vibration?

Logic: the primary causes of vibration at what is referred to as rotor frequency, are unbalance, misalignment, a bent or bowed sha , or an eccentric rotor. Any of these conditions can cause a 1X sha speed vibration or harmonics of that frequency. These conditions cause approximately 75 per cent of all vibrations in industrial plant rotating equipment.

4. Are your vibration analysts familiar with rolling element problems that can be determined using vibration analysis?

Logic: anti-friction bearings inherently have low starting friction but high running friction, and the sha frequency for oil lubricated bearings should not exceed 9,600 divided by the sha diameter. Grease lubricated bearings will have a sha frequency that will not usually exceed 7,200 divided by the sha diameter.

For example, a six-inch diameter sha supported by grease lubricated anti-friction bearings should not be run at a frequency higher than 1,200 RPM (or 20 Hz).

Rolling element fault frequencies are caused by fatigue or running wear, incorrect or insufficient lubrication, misalignment or manufacturing flaws within the bearing. There are four fundamental frequencies in anti-friction bearings. These are: fundamental train frequency (FTF), ball-pass frequency of the inner race (BPFI), ball-pass frequency of the outer race (BPFO) and the ball-spin frequency (BSF). These defect frequencies depend upon the shaft speed and bearing geometry. The type of bearings used in the machine should always be recorded in maintenance files and manufacturer’s data can be obtained to provide the specifications.

5. Are your analysts familiar with journal bearing problems that can be determined using vibration analysis?

Logic: at low RPM, journal bearing friction is high due to boundary lubrication. The friction decreases as the sha moves into the rotating position where there is a full oil film between the sha and bearing’s inner surface. A vibration problem associated with journal bearings is the possibility of hydraulic instability of the rotating sha inside the bearing. This vibration is caused by “oil whirl” or “oil whip.” This is caused when a wedge of lubricant moves the sha in an eccentric motion as the sha rotates, which if severe enough will cause a vibration. The frequency will appear somewhere between 35 to 49 per cent of the sha ’s rotational frequency.

6. Are your analysts familiar with vibration problems associated with gear drives?

Logic: gear mesh vibration frequencies will be very high and can be calculated by multiplying the number of gear teeth by RPM of the shaft. When diagnosing a multiple gear train, calculate the gear ratio between the drive and driven gear(s). Then use this ratio to calculate the speed of the driven gears. Most gear box manufacturers will provide this information and may provide the various frequencies within the drive.

7. Do your analysts understand vibration problems associated with fan blade and pump impeller vibration problems? Logic: blade pass frequencies occur as each blade on a fan or compressor rotor delivers its contribution to the process. The blades on a pump impeller create a frequency as the blade passes the outlet port. Blade or vane pass frequencies are inherent in pumps, fans and compressors and normally do not pose a problem. However, large amplitude BPF with harmonics will be generated in pumps if the “vane to diffuser” gaps are unequal, if the impeller wear ring seizes on the sha , or if welds fail. High BPF can be caused by bends in piping, ducts, or obstructions that disturb flow.

8. Do your analysts understand the relationship between vibration frequencies (the forces that cause vibrations) and resonance?

Logic: resonance is the excitation of the natural frequency of a system or the excitation of a component within that system. Put another way, resonance is a condition where the frequency coincides with a systems natural frequency. If a resonant frequency is excited by another frequency operating at or near the same speed, a rotating machine or component can destroy itself in a very short time.

This is a brief introduction to the topic of vibration analysis as a troubleshooting tool. If understood and applied correctly, it offers early warning of many rotating machinery problems. Used in combination with other predictive maintenance technologies like thermography, lubricant analysis, and acoustic ultrasonics, the return on investment will be worth every penny. MRO

L. (Tex) Leugner, the author of Practical Handbook of Machinery Lubrication , is a 15-year veteran of the Royal Canadian Electrical Mechanical Engineers, where he served as a technical specialist. He was the founder and operations manager of Maintenance Technology International Inc. for 30 years. Tex holds an STLE lubricant specialist certification and is a millwright and heavy-duty mechanic. He can be reached at texleug@shaw.ca.

Weekly schedule compliance is an easy key performance indicator (KPI), but a lot of people mess it up. We can use it to lock-in mediocre performance. However, when used properly, KPI can help boost our maintenance productivity.

BY DOC PALMER

Let’s talk about KPIs first. What we ultimately want is a greatly profitable company (that operates in a legally, safe, and environmentally conscious manner). We all understand this basic measure of company success, the reason for its existence. However, if asked if you would rather have great schedule compliance? You should respond “only if it leads to great profits in a legal, safe, environmentally conscious way.” Perfect. You see that our primary objective is not schedule compliance itself.

From a maintenance perspective, what contributes to a company’s success? Well, we work on stuff, manage to fix most things that break, and do a good amount of preventive maintenance. As well as keeping the lines running that produce products that the company sells. Without any weekly scheduling at all, maintenance supervisors are good at keeping their crews busy doing this work. Nevertheless, plants starting their crews with fully loaded schedules actually have more productive crews. If a crew is more productive, it can do more proactive work, keeping things from breaking. It can replace a bearing reported from

the vibration route. It can repair an air leak reported from the ultrasound route. It can tighten an electrical connection reported from the thermography route. Such extra proactive work can be scheduled at more convenient times to minimize line down time, and increased uptime increases profit.

Having more productive crews contributes to greater company success though an increased completion of proactive work. The phenomena of fully loaded schedules driving higher productivity has a bit to do with goal se ing. Think of it as the power of a list. If waking up in the morning with a list of five things that can be done, you’ll be more productive than if waking up with an intent to be busy. With the list of five, and completing three or four things, but without a list only two or three things, would be done. Do you see how the list helps focus and is more productive?

A good question here would be “how big should the list be?” With goal se ing, if a goal is too high, it seems unachievable and doesn’t encourage extra effort. However, if a goal is too low, it doesn’t need extra ef-

fort. Matching the list with what could be done in a perfect world (with no reactive work) helps drive extra productivity, but only if it is okay not to get it all done.

Applying this to a weekly maintenance schedule, we would start with a crew of 10 people (each with 40 hours available) with 400 hours worth of work. Their resulting productivity would be higher than another 10-person crew starting with only 300 hours’ worth of work, a schedule that allows for 100 hours of break-ins. Both crews will take care of break-ins, but here is the key: the crew that starts with a fully loaded schedule will probably complete more work overall but with lower schedule compliance than the other crew.

The fully loaded crew might have a schedule compliance of only about 60 per cent, but might complete 210 work orders. The less loaded crew might have 95 per cent schedule compliance, but might complete only 140 work orders. Both crews probably completed all the visible breakdown work and critical PMs. However, by sheer numbers, the more productive crew completed more proactive work, the key to be er company performance.

Tip: If schedule compliance is above 90 per cent, we probably aren’t giving our maintenance crews enough work.

Therefore, the schedule compliance KPI is a simple check on the loading of the schedule and not an end unto itself. Don’t make it much more complicated than that. The full loading of the schedule is the driver of productivity. Schedule compliance tells if you truly are fully loaded it. If the schedule compliance is above 90 per cent, that usually means the schedule is not fully loaded. In a good performing plant, we might expect 20 per cent reactive work (three per cent emergency and 17 per cent urgent), so 80 per cent schedule compliance would be about perfect.

However, if you had 90 per cent schedule compliance, it means you did not give crews enough work to focus and encourage them beyond the “keep busy” level. You are not doing as much proactive work as you could be doing. You are not as profitable as you could be. See how it rolls together up to why your company exists? If you set a “target” of 90 per cent schedule compliance, you are forcing yourself into mediocrity even if you think you are fully loading schedules. You are forcing people to over-estimate planned hours or under-estimate labour capacity.

“People with targets and jobs dependent upon meeting them will probably meet the targetseven if they have to destroy the enterprise to do it,” said Dr. W. Edwards Deming.

Refer to “schedule “compliance” as “schedule success” since we all want the schedule to succeed. Some people call it schedule a ainment, but that leads toward giving credit to jobs worked on, instead of completed. Credit should go for scheduled jobs that were actually completed, not simply worked on. Also, quantity of jobs instead of scheduled hours for the measurement, is preferred. “We scheduled 200 jobs and you completed 120 of

those jobs (60 per cent schedule success) and 90 other jobs. Good job.”

Schedule compliance is a great KPI, but certainly invites a lot of discussion about exactly what it is good for. It’s not too complicated even though, just the tip of the iceberg was presented here.

Its primary value is in telling us if we are truly loading our crews with enough work each week. MRO

Doc Palmer, PE, MBA, CMRP is the author of McGraw-Hill’s Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Handbook and as managing partner of Richard Palmer and Associates helps companies worldwide with planning and scheduling success. For more information including on-line help and currently scheduled public workshops, visit www.palmerplanning.com or e-mail Doc at docpalmer@palmerplanning.com.

By the time mechanical failures or maintenance issues are spotted, they’re often already too serious or expensive to repair. Meaning that operators and asset managers have to put a piece of equipment out of order until it can be replaced or fixed, which has a direct negative impact on the business’ bottom line.

BY DARRYL PURIFICATI

When incorporated into a proactive maintenance program, used oil analysis can help with early detection of atypical operations, such as mechanical issues, and the prediction of future maintenance needs. This not only allows for maintenance requirements to be effec-

tively planned for and managed, but also improves the reliability and efficiency of the equipment. Used oil analysis can be easily incorporated into proactive maintenance programs to monitor the condition of heavy-duty engine oil, and the condition of other fluids such as coolant, transmissions, axle, and hydraulic fluids.

A heavy-duty engine oil keeps the internal hardware of the engine protected, and helps it operate with maximum efficiency. Engine oil is vital to the operation of the engine and is its lifeblood. Used oil analysis can provide detail into the condition of the oil, giving valuable insight

into the overall health of the engine, and help with early identification of potential issues, similar to how a blood test can confirm wellness, or highlight underlying conditions.

Used oil analysis is a simple three step process to produce a report, which can inform future maintenance require-

ments and identify potential anomalies that can impact the overall health of the engine. The first step is to take a representative sample of the engine oil. Next, the sample should be sent to a qualified laboratory for analysis. The final stage is to interpret and act on the findings of the report. This can improve the reliability and performance of the equipment while highlighting the potential to safely extend oil drain intervals (extending drain intervals should always be undertaken in conjunction with an oil analysis program) to reduce scheduled maintenance costs.

Acting on the results of the used oil analysis report is essential, and means that its insight isn’t le unused and filed away if no immediate warning signs stand out.

Lubricant experts can also share their experience to identify common anomalies and early warning signs to look out for. For example, if coolant or glycol is present in the oil sample, it could be the first signs of a failing exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) cooler seal. If this is

a potential concern, levels of silicon, potassium, and sodium should be watched closely as a failing EGR cooler seal needs immediate a ention.

Also, some forward-thinking lubricant experts have developed digital tools to support equipment and maintenance managers to extract the full value of their oil analysis program. These digital tools can allow samples and data results to be accessed from desktops and mobile devices, allowing on-site access to the latest insight. Intuitive dashboard graphs and customized reporting can also help prioritize critical results and detect abnormal conditions before they cause costly repairs, and track maintenance events to forecast extended drain intervals and equipment performance.

The latest generation of used oil analysis data tools can help fleets reduce their maintenance costs, and prevent disruptive unplanned downtime. Ultimately adding to the bo om line of the business, used oil analysis is an essential part of any fleet’s proactive maintenance program. MRO

Darryl Purificati is the OEM Technical Liaison for Petro-Canada Lubricants.

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly changed the maintenance landscape.

BY PETER PHILLIPS

Some manufacturing facilities have suffered shutdowns or cut backs because of the virus. Permanent closures have occurred in some industries due to the lack of demand, and owners not being able to hold on with falling sales and profits. Industries such as the airline industry have been hit hard, and have laid of thousands of pilots, flight a endants, and support staff.

Sales of building materials hit a very low point early in the pandemic, even though they were classified as an essential service and remained open for business. Luckily, this sector has recovered well over the past couple months, driven by home owners staying home and spending money on home improvements.

The food industry has been strong during COVID-19, but have suffered staff storage with breaks outs of the disease at some plants, and have reduced production output due to social distancing in the workplace. Public institutions like universities are preparing to conduct their classes online for the fall semester and some expect only a fraction of students to be on campus. This will dramatically affect the number of staff needed to maintain the campus.

The cutbacks and closures have had a trickle-down effect on many support services as well. Maintenance contractors depend upon on repair and maintenance contracts with factories

to keep their businesses alive as well. Some high security facilities, dependent on contractors to perform equipment maintenance, are still closed to outside contractors and vendors, unless absolutely essential to the business.

This many changes in a short period of time will have long term effects, both good and bad, on how equipment is maintained. Repair and maintenance relies heavily on interpersonal contact. The majority of maintenance activities requires more than one person working in isolation. Maintenance generally takes people working in close proximity to each other. Changing a large drive assembly for example may take two to four people, working within inches of each other.

Therefore, it is understandable that there will be increasing numbers of COVID-19 infections at manufacturing facilities. Maintenance offices and workshops are not all designed for six-feet of social distancing, many plants have reduced staff and people working from home to help reduce the spread, and to protect people’s health. However, the maintenance on equipment must be completed to keep the plant running. Wearing the appropriate PPE to protect people from the spread of the virus creates challenges. Wearing face masks and shields are not normal PPE for maintenance personnel, and in plants that are hot and humid, face shields and safety

glasses fog up from breath escaping the face mask; adding to the time of maintenance repairs and discomfort for the workers. In turn, additional work time must be added to allow for these safety precautions.

The way equipment is serviced and maintained has changed, and it doesn’t look like it returning to normal is anywhere in sight. The cost of doing maintenance has increased, just like producing and selling products in stores. Take in consideration the extra cost of security to screen employees, contractors, and customers. Rolling in the added cost of special PPE and sanitation means the difference between staying in business, or closing the doors.

Industries are rethinking how to conduct maintenance with less people while performing the same maintenance routines. Many staff are working from home, for example, maintenance planners are organizing and remotely communicating work orders to maintenance staff. This is not ideal; however, it keeps the maintenance staff executing repairs and maintenance. Changes like these have created a big technology challenge as people work from home, and need laptops linked to the plant’s secure networks to access maintenance programs and files. Infrastructures have been developed so people can work remotely, a end online meetings, and doing their best to keep the plant running during these pandemic times.

Projects that companies started before the pandemic or have scheduled, must still be carried out in order to meet deadlines and budgets. New so ware and business applications still need to be installed, trained out, and implemented. In the past, these projects were led by teams that went from plant-to-plant, province-to-province and country-to-country to assist in the implementation. Now provincial, state, and country borders are closed or restricted, and many companies have COVID-19 polices restricting travel until the threat has passed or under control; however, projects must be completed.

Project teams along with plant staff have been asked to come up with alternatives, and figure out how to complete projects without on-site support staff they had in the past. Corporate teams have been formed, and work behind the scenes developing alternative plans to support their facilities. They are busy developing videos and support documentation, to train people

at the facilities to implement new systems and how to operate new equipment.

Although it takes a great deal of work to develop alternative methods to support plant projects, plant staff actually face the biggest challenge. They are already in a situation of reduced staff and resources, facing reduced maintenance budgets due to financial losses. Now, plant maintenance staff must take on the added responsibility, and take the lead role of site project manager. They have become the plant expert and trainer to teach staff new technology and equipment while still carrying their full work responsibilities at the plant.

Repairs and maintenance during this time have added new innovation, and people are asked to think out of the box and develop new ways of doing maintenance activities. For years maintenance routines have been done “the same old way” without a second thought, now with social distancing, fewer staff, and less operating capital in the maintenance budget, the need for smarter ways of doing maintenance have been developed. Ge ing the job done with the added COVID-19 challenges, maintenance staff have had to examine what really needs to be done, to be more specific on what to inspect, and how to inspect it to ensure the reliability of the equipment.

There will be benefits a er this is over. Maintenance activities will look different because we have found be er ways to perform them. More specific preventive maintenance inspections, will reduce time needed to complete work orders, thus reducing work order backlogs. There will be a cost reduction in plant-to-plant travel as technology has replaced the need for face-to-face meetings.

Indeed, maintenance departments have faced this challenge head on, and have adapted quickly to perform their essential repairs and maintenance. New ideas, new ways of doing things, COVID-19 has demanded innovation and maintenance departments should feel proud of their accomplishments. MRO

Peter Phillips is the owner of Trailwalk Holdings Ltd., a Nova Scotia-based maintenance consulting and training company. Peter has over 40 years of industrial maintenance experience. He travels throughout North America working with maintenance departments and speaking at conferences. Reach him at 902-798-3601 or peter@trailwalk.ca.

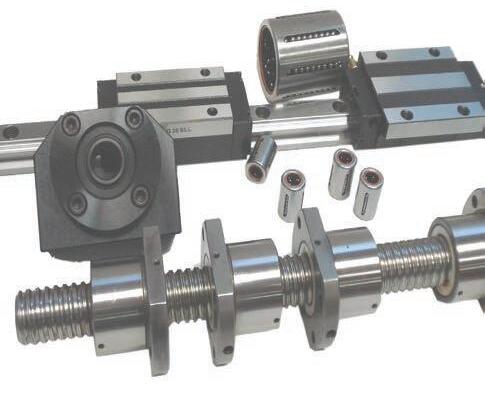

• Design

• Software

• Components

• Commissioning

• Worldwide support

The COVID-19 outbreak has exposed the vulnerability of every aspect of our society, and that includes supply chains. Even relatively well-prepared businesses have su ered serious problems due to supply shortages. By adopting several key measures to increase the adaptability of your supply chain, you can secure your productivity and maintain your bottom line. By Chris Beaton

The pandemic sent shockwaves through supply chains that had operated without interruption for years. Due to its long-standing reputation as “the world’s factory”, countless businesses sourced essential materials from China. The concentration of manufacturing and supply in one geographical location intensified the e ects of widespread factory shutdowns.

Looking ahead, even as many countries return to a semblance of business-as-usual, the potential for further disruption is high.

Luckily, it’s not too late to take measures to become more agile so your business can react more e ectively to protect its supplies. These measures include innovative sourcing strategies for essential motors and parts, leveraging advanced technologies to maximize visibility in your supply chain, and diversification.

In the face of disruption to shipping and supply lines, companies must look for suppliers that bring product stockpiles closer to home, reducing the risk of supply shortages that interfere with productivity.

As businesses react to disruptions, many have found themselves hampered by a lack of visibility into the supply chains that they rely on. This is a result of the traditional linear supply chain model, where an outdated silo approach drives each part of the chain independently, with limited information-sharing.

Many businesses are moving towards a new supply chain model that leverages advanced technology including analytics, software, automation and artificial intelligence to digitally connect all of their operations. This optimizes the flow of information, enabling them to forecast shortages and rapidly deploy response strategies.

Across industries, the pandemic has exposed the risks of one-source supply chain practices. Sourcing from one provider encourages consistency when the markets are stable, but they can also create a dependency and power dynamic between the buyer and seller.

By moving to a diversified marketplace model, businesses can maintain relationships with existing providers while incorporating new partnerships and alternative options. Gain negotiating power, enjoy greater cost transparency and be able to decrease the risk of supply shortages.

By reviewing your current supply chain process, you have the opportunity to position your business to stay productive and profitable during current and future disruptive events. Don’t just prepare your business to ‘survive’ COVID-19 – prepare your supply chain to run more e ciently than it ever has before

Chris Beaton, Red Seal Electric Motor Systems Technician, is the CEO and co-founder of eMotors Direct. With over 26 years in motor sales and service, Chris has developed solutions to enhance the motor supply chain. Originating from Edmonton, Alberta, eMotors Direct has access to the largest supply of motors in Canada. Visit eMotorsDirect.ca to browse motors. Anytime, anywhere.

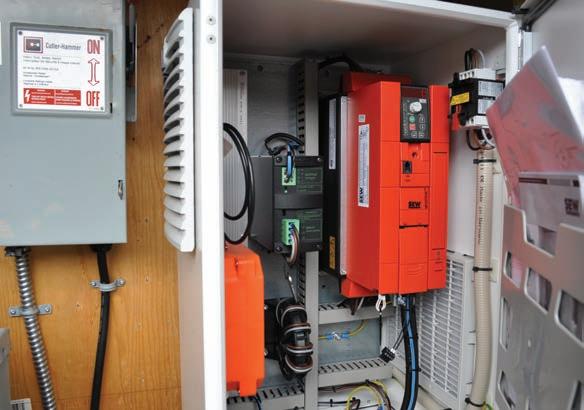

Rail Yard Wake Boarding Park Makes it SEW.

Traditionally, wake boarding whizzes us across open water behind a high-powered motor boat using nothing more than a scaled-down surf board, a tether and nerves of steel. The same rules apply at Rail Yard Wake Park and Aqua Park located in Mount Albert ON, but with one little exception: no high-powered motor boat!

Founders Ian Bowie (left), Ross Benns (second from the left), and Christine Benns (second from the right) changed their love of water sports into an innovative and exciting business.

“The idea of enjoying wake boarding without the environmental implications of using a speed boat really intrigued us—we just needed to find the right venue and the right application to do it.”

After years of scouting the GTA for an ideal spot and hurdling through power supply and government regulations, Rail Yard Wake Park and Aqua Park was open for business in the summer of 2013.

“We wanted to capture the true feeling of traditional wake boarding and open it up to the public. You can literally show up here with a set of swim trunks and everything else is taken care of.”

Capturing the true feeling of wake boarding required a drive system that was robust enough to handle a solid 12 to 15 hours of uninterrupted use, along with integrated electronics for ultra-precise speed control and wireless capability.

The zip line application was designed and built by a company based in Germany called Sesitec. Realizing a wake park requires a precise ensemble it came equipped with SEW-EURODRIVE drives and electronics. However, operations managers, Ross and Ian knew that any downtime would result in a big disappoint to their customers.

“We wouldn’t want to see the look on the faces of our guests if one of our two lines went down. An average ride is 7 to 10 minutes, so we need to be sure any problems can be addressed quickly. Sesitec has a great reputation for expedited delivery of critical components, but we needed a service protocol in place specifically for the drive system.”

After a quick chat with a colleague, Ross discovered that SEW-EURODRIVE has several Canadian o ces, one being local that could replace or repair the drives and electronics 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year.

“We got on the phone immediately and talk about rapid response, the Service Manager, Scott Gallop, called us back right away—then he showed up at our park the following week. Scott told us exactly what we wanted to hear and based on his responsiveness, we knew he meant what he said.”

“We really appreciated Scott’s level of interest in what we do and we didn’t even buy anything! This just shows you what type of company Eurodrive really is—they care. When the time comes for servicing our drive system, we will definitely make it SEW.”

MRO Magazine recently held its first-everMaintenance and Reliability in a Changed World Virtual Summit, which allowed maintenance, reliability, and operations professionals to learn techniques to optimize their day-to-day maintenance activities. The summit brought together professionals from across the MRO world, and a endees were very engaged throughout. Industry experts and sponsor representatives gave a series of presentations and discussions that le a endees with a plethora of information to digest.

Suzane Greeman from Greeman Asset Management Solutions Inc., led a session on Executive Leadership in Asset Management: What The C-Suite Needs to Know. She summarized her presentations as follows.

“Many asset-dependent firms have assets that are important to national life, such as powerplants, water treatment plants,

airports, railways, sea ports and manufacturers. Many of these are at significant risks. They have been weakened internally by aging assets, inappropriate business systems, and human factors. They have also been threatened externally by global socio-economic and geo-political factors.

“Top management is ultimately responsible to the stakeholders for value creation, and therefore need to protect the organization from value erosion. This level of management is also the only level vested with the authority to build the culture, sustain it, enact policy, and make structural changes. This means that senior leadership have a special responsibility to build internal resilience to protect the organization from external threats.

“Senior management also has specific responsibilities as it relates to the asset management system.They need to: provide clarity around the strategic direction of the organization;es-

tablish the asset management office, the related governance and provide specific approvals;champion asset management philosophies;create cohesion, disruption and collaboration at the middle management level;align financial and non-financial Information; create financial literacy; managecompetences; continually evaluate roles and responsibilities; promote the integration of asset management processes into the organization’s other business processes; educate themselves in asset management; and don’t circumvent the organization’s asset management processes. Asset management requires top management oversight, participation and active support. Asset management is a top management job.”

James Reyes-Picknell from Conscious Asset led a session on The New Normal for Continual Improvement, which proved very engaging, and included a lively Q&A session. He summarized his presentation as follows.

“The "new normal" remains largely ill-defined, although we continue to learn what is working and what is not working when it comes to handling COVID-19, and its impacts in our daily lives at home and at work. What we do know is that the "old normal" is gone, and that one thing remains constant, change. In the world of MRO, many companies were already struggling with high maintenance costs, and low availability of productive assets leading to less than the best business performance. Few had improvement initiatives underway and even they put those on hold when COVID-19 measures hit.

“With fewer numbers at work, many working in new ways, and li le change to old business processes, we can expect less efficiency from those processes. There was simply no time to

consider re-engineering before sending people home. We are coping, some be er than others, and we know that what we are doing now is not going to be sustainable. Where MRO performance was low, it is still low and likely even suffering more. Funding for maintenance and parts has been cut by some 28 per cent of companies and another 41 per cent have suspended capital work and new acquisitions.

“We know that reduced maintenance now will come back to haunt us. Reduced parts spending is hurting now and will only get worse. The need to improve efficiency and effectiveness of our maintenance and reliability programs has not changed, and may be even more critical now. Leadership is not even looking at it, 42 per cent of those a ending the summit responded that lack of leadership foresight is a barrier to improvements as their companies emerge from COVID-19. Another 38 per cent are somewhat distracted by current measures. That's a whopping 80 per cent who have taken their eyes of the ball. That is a leading indicator that our industrial recovery from COVID-19 is likely to be marked with setbacks in performance and competitiveness, unless we make some course corrections, and make them soon.”

Finally, an open discussion featuring speakers and sponsor representatives; took place. The session saw all participants partake in a lively debate on a variety of MRO related topics, aided by a variety of questions from a endees.

Those who missed the live presentation, can now view the sessions on-demand. The session are available here: www. mromagazine.com/virtual-events/maintenance-and-reliability-in-a-changed-world-virtual-summit/ MRO

WAGO I/O System

Field is IP67 rated and offers two types of housings: cast zinc with encapsulated electronics, and non-encapsulated plastic with low mass. Cast zinc housing devices have input and output power ports for use with daisy chained modules, and are Profinet based. Future releases will be able to support EtherNet/ IP and EtherCat protocols. They are designed for the timesensitive networking standard, support OPC UA and MQTT communications, and can be configured via smart device app using Bluetooth technology.

Non-encapsulated lightweight modules are IO-Link hubs for connection to an IO-Link Master. They are available in eight or 16 configurable DIO ports and each channel is configurable for a 24 VDC digital input or output rated at two amps per channel. Both are equipped with load management. Current and voltage levels can be recorded and evaluated, and overload limits and alarms can be set for each channel. www.wago.com/us/discover-io-systems/field

AMADA WELD TECH Inc., MIB300A and MIB-600A AC inverter welding power supplies, offer exact heat input and quality welds. It uses inverter technology with pulse width modulation to produce and simulate an AC waveform. AC inverter can produce an AC frequency from 50 to 500 Hz, is not affected by line voltage fluctuation, and provides a balanced three phase load.

MIB-300A and MIB-600A feature secondary constant current control, up to 20 pulses per weld and ability to set upslope, downslope and weld interrupt. MIB-300A and MIB-600A may be used with the same transformers and weld heads as standard AC welders. With max output currents of 20,000 and 40,000 A respectively, the units may be used for a variety of welding applications. www.amadaweldtech.com

Pipestoppers, low profile inflatable stoppers are available in sizes 150 to 2,235 millimetres in diameter and provide grip inside the pipe, with an airtight seal. Each stopper is fi ed with a standard schrader valve connected to a 1.2 metre hose, is inflatable using a foot pump or compressor, and is heat resistant up to 80ºC.

Cylindrical and spherical stoppers: stop the flow of gas or liquid inside pipes and ducts. Available up to ø 2,440 mm. For higher temperatures, these inflatable stoppers can also be manufactured with a heat resistant cover for temperatures up to 300ºC.

PetroChem stoppers: manufactured from latex, are used for stopping off pipes with hydrocarbon gases and liquids inside. Inflatable rubber plugs: a wide diameter range, can withstand chemicals and hydrocarbons, for higher-pressure applications, with a long life. www.huntingdonfusion.com.

Optimized for hydraulic valves and actuators, TE Connectivity LVDT position sensors are accurate, reliable, compact and adaptable. LVDT position sensor can measure spool position within onethousandth of an inch and infinite resolution.

Friction-free operation enables reliable sensor life and repeatability, allowing hydraulic LVDTs to be used in demanding, high-cycle applications. They are hermetically sealed and can be mounted inside valves, capable of withstanding high pressure (up to 10,000 psi) and harsh exposure such as hydraulic fluid. Stroke lengths as low as +0.005 inches.

www.te.com

Harold G. Schaevitz Industries LLC ILPS-18S Series spring loaded inductive linear position sensors use LVIT Technology. It has a compact design, long service life, and ideal for test stands, test laboratories, automated assembly machines, processing and packaging equipment, robotics, and automotive test applications.

It offers: measuring ranges from 13 to 100 millimetres; excellent stroke-to-length ratio; service life rated to over 100 million cycles; 19 mm diameter threaded aluminum housing sealed to IP-67; and,axial termination with M12 connector or integral cable.

www.hgsind.com/product/ilps-18s-linear-lvit-positionsensor-spring-loaded