by Brett Ruffell

by Brett Ruffell

As we slowly move beyond COVID-19 restrictions, one thing some people in agriculture have been eager to restart is hosting and attending barn tours. They can be invaluable tools for educating both students and decision-makers. This, in turn, can help shape public opinion and influence government policies.

But the current avian influenza outbreak has delayed those plans for the foreseeable future – at least in poultry. Still, there’s a trend that ramped up during the pandemic that could expand the reach of these events tenfold without the biosecurity hassles – virtual field trips.

I spoke with two poultry producers, as well as an industry executive, who’ve become so adept at hosting these events that they have them down to an art. Here, they share their best practices in case other producers want to digitally showcase their barns in the name of industry advocacy.

It could be something producers organize themselves or a collaboration with an industry organization.

The first question would-be hosts need to answer is whether to make it a live or pre-recorded event. To Tiffany Martinka, a chicken producer from northeast Saskatchewan, real time is the way to go.

“If possible, I highly recommend doing it live because it allows you to interact and

engage with the audience,” says Martinka, who in one event took 100 classrooms on a tour of her barn to educate students about chicken production. “If I can engage with them and have them asking questions, it gives them a much richer experience.”

Of course, it also depends on the quality of a barn’s Wi-Fi. Everyone I consulted underscored the importance of doing a dry run to test the strength of the facility’s internet connection throughout the barn and note any ‘dead spots’ where it’s weaker.

Kelly Daynard, executive direction of Farm and Food Care Ontario, did just that when organizing a virtual tour of a layer

“I highly recommend doing it live because it allows you to interact and engage with

the audience.”

barn. It proved to be a wise precaution. “It was a beautiful barn, but we absolutely could not get a Wi-Fi signal,” Daynard says. Thus, the producer pre-recorded a tour of her barn. And during the live broadcast, the farmer was there to answer questions as attendees watched the recording.

Asking people beforehand what they hope to gain from the tour is another good idea. When Martinka hosted an event for parliamentary secretaries, for example, she knew they were more interested in sustainability

and the environmental impact of livestock production. Thus, she planned the event accordingly. “So, knowing your audience is really important,” she says.

In terms of equipment, it’s possible to host a quality event on a shoestring budget. Harley Siemens, an egg farmer from Rosenort, Man., had an employee follow him with an iPhone mounted on a gimbal, which is a handheld accessory that ensures the device is level during videos. Gimbals go for about $130. He also used a Bluetooth headset ($50) with a mic attached for quality audio.

For producers looking to get started with hosting virtually barn tours, Martinka recommends starting small. She first hosted one classroom with help from a friend to assess what works and what doesn’t. “That’s a great way to get feedback and practice,” she says.

Daynard advises virtual hosts to shoot in landscape to show more of the facility. She also says to be mindful of lighting and shadows. Additionally, she says to keep the event to about 20 to 30 minutes. “We find that’s the maximum attention span people have with these events.”

Everyone I spoke to vows to continue hosting virtual tours even when the pandemic and the latest avian influenza outbreak are behind us.

For one, they provide greater reach than in-person events. Cost is also a barrier for classes to attend in person. Biosecurity will always be a concern. Lastly, Siemens says virtual is just as rewarding as in person. “I just love talking about what I do.”

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Anita Madden, Audience Development Manager Tel: (416) 510-5183

Email: amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Brand Sales Manager Ross Anderson randerson@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-925-7565

Account Coordinator Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Curtis Martin

Group Publisher Michelle Allison mallison@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes) USA – 1 Year $91.50 CDN Foreign – 1 Year $103.50 CDN GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2022 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

SpechtCanada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

In late April, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency confirmed Manitoba’s first case of avian influenza in a commercial poultry flock, and third case overall. The federal agency detected the first case of highly pathogenic avian influenza strain H5N1 at a farm in the rural municipality of Whitemouth, east of Winnipeg. With these cases, the disease has now been detected in every province during the current outbreak.

The European Union and 30 countries have restricted Canadian poultry and egg imports, according to an industry lobby group, as this year’s deadly avian flu infects flocks in almost every province. The Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council said in an e-mail that the trade restrictions vary in scope, with some countries banning all imports from Canada and others limiting restrictions to affected provinces. The EU and the United States have enacted measures that apply only to products from within 10 kilometre zones around each infected farm, according to CPEPC president Jean-Michel Laurin.

Abbotsford farmer Fred Krahn has been named the BC Egg Legacy Award recipient. Krahn was presented with the honour by B.C. Minister of Agriculture Lana Popham at BC Egg’s recent conference and annual general meeting in Vancouver. The award is not given out on a set schedule, but is given out when a worthy candidate is identified.

1.7M is the number of birds poultry and egg producers have lost due to avian influenza since the current outbreak began in late 2021.

When David Hyink checks on his barns each day, he does so with a sense of trepidation.

David Hyink is a broiler producer in central Alberta and chair of the Alberta Chicken Producers. The current avian influenza outbreak has hit the province the hardest.

The central Alberta chicken farmer is on the lookout for lethargy, lack of appetite, or just a general appearance of ‘droopiness’ in his birds – all of which could be signs of the highly pathogenic strain of H5N1 avian influenza currently circulating in both wild and domestic flocks across North America.

If the disease were to turn up on his property, Hyink knows it would mean the loss of his entire flock.

Avian influenza has a high mortality rate, and those birds at outbreak sites that don’t die from the disease are humanely euthanized to prevent the spread of the virus.

“While we haven’t had it on our farm, and I hope we don’t, it just appears it could be anybody,” Hyink said. “It could be us next, the farm next to us – you just don’t know.”

It’s that kind of uncertainty that is driving high levels of fear and stress on Canadian farms, where – according to Canadian Food Inspection Agency – poultry and egg producers have lost more than 1.7 million birds to avian influenza since late 2021. (The tally includes both birds that have died of the virus and birds that have been

euthanized).

Alberta is the hardest hit province, with 900,000 birds dead and 23 farms affected. Ontario is the second hardest hit, with 23 affected farms and 425,000 birds dead.

But outbreaks of the virus have turned up now in every province except Prince Edward Island. Across the country, farmers are being encouraged to keep birds indoors, restrict visitors and ramp up biosecurity measures to help halt the spread.

The virus can be spread between birds through direct contact, but it also spreads easily from wild bird droppings and can be carried into commercial flocks on the feet of workers or on equipment.

While avian influenza was first detected in Canada in 2004, this year’s strain – which has also been wreaking havoc in Europe and Asia – is “unprecedented” in terms of its global impact, according to the CFIA.

The new strain is highly transmissible and appears to be sustaining itself within wild bird populations. While there’s some hope that case counts might decline when the spring bird migration ends in June, for now, farmers are left wondering where and when the next outbreak will happen.

By Lilian Schaer

Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC) fosters research collaboration and drives innovation in the livestock and poultry industry. Visit www.livestockresearch.ca or follow @LivestockInnov on Twitter.

Thanks to the growing public interest in how food is produced, farmers are now often told that they must take charge of telling their story or someone else will do it for them. That’s happening now with livestock, poultry and climate change, for example.

The frequency of media articles pointing the finger squarely at the livestock industry – and this includes poultry – with statements like “livestock are the most dangerous technology on earth” is increasing, and much of the coverage suggests the solution is reducing or eliminating animal agriculture altogether.

There’s no doubt that livestock production contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, but it also produces highly nutritious food and supports carbon sequestration and biodiversity, and its by-products are widely used in many applications world-wide.

The industry has definitely made environmental progress and, although individual sectors are trying hard to publicize that progress, it’s often hard for good news to grab a fair share of media, government or public attention.

Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC) has begun promoting the need for documenting and sharing the importance of the livestock industry to Ontario’s food security, environment and economy.

That’s particularly important today, believes LRIC CEO Mike McMorris, because, although livestock farmers see themselves as egg, chicken, beef or dairy producers, the broader public doesn’t make that distinction.

“Issues like climate change or greenhouse gas emissions impact the entire sector and are bigger than a single commodity organization – and we need to remember that the public doesn’t see us the way we do,” McMorris says.

“As an industry, we need to work together.”

Ian Ross, president and CEO of nutrition company Grand Valley Fortifiers, is chair of LRIC’s Emerging Issues Committee, which monitors trends and developments that have the potential to impact the future of livestock production.

“As an industry, we need to work together, stop competing with each other on protein consumption and talk about the importance of livestock in the ecosystem and in the context of food security,” he says. “We have common business and industry risks, and there are a lot of major forces at play here that are moving against all of us, so let’s work on those challenges together.”

With the input of its member organizations, LRIC has been leading the development of an Ontario Livestock Declaration to encourage greater collaboration and more cohesive messaging around the importance of

livestock production.

A balanced message about the sustainability of the industry could include greenhouse gas emissions per serving of balanced protein; responsible animal care and One Health considerations; impact on soil health, biodiversity, and the environment; and domestic food security, for example.

Reporting on the industry’s progress in these areas will play an important role in supporting that balanced messaging. Many individual sectors are already being proactive in dealing with many of these topics, but the key to making the results resonate will lie with a collective approach, believes McMorris.

“A comprehensive livestock report card of sorts, which pulls together all of our sector-specific information and achievements into easy-tounderstand statements of the industry’s importance and of the progress we’re making in sustainability would be powerful,” he says.

The audience includes government, which McMorris and Ross both suggest needs to know that the livestock sector is a vital contributor to the economy and domestic food production that is also taking action on environmental issues.

“A lot of one-sided science is trying to indicate that the best thing for the world is to get rid of all livestock, but there is collateral damage when things aren’t thought through,” Ross says. “There is no way that any individual producers or sectors can influence this, so let’s work together to communicate the importance of our industry.”

Protein common in milk may help early gut growth in broilers.

By Lisa McLean

The first 10 days of life are crucial for a broiler chick’s fragile digestive system, and exposure to harmful pathogens can lead to poor growth and health issues. As the industry phases out preventative antibiotics, researchers are looking for new ways to make a bird’s digestive system stronger, faster – using a protein that is commonly found in milk.

Dr. Elijah Kiarie of the University of Guelph is working with epidermal growth factor (EGF), a protein that helps with healing. It’s activated when it binds to EGF receptors that are found along the length of the small intestine in poultry.

“One of the many ways to make a chicken’s digestive system more robust without relying on antibiotics is to develop the gut quickly,” Kiarie says. “We want young chicks to eat and absorb nutrients as quickly as possible in those first 10 days, so they are stronger and more developed.”

As part of Kiarie’s work, he has been testing the most effective way and time to deliver EGF to enhance a bird’s intestinal tract. First, he had to confirm when EGF receptors appear in a chicken’s small intestine so he could take advantage of accessing them as early as possible.

Kiarie administered EGF in ovo, directly into the egg, and investigated the presence of EGF receptors at various stages from

days 17 to 21. “What we found is that the EGF receptors only appear on day 21 — when chicks hatch. Once we understood that, we realized it would be more effective to apply EGF directly to feed,” Kiarie says.

The small intestine is lined with villi, tiny hair-like projections that help absorb nutrients. Rapid growth of the small intestine in the first 10 days of a chick’s life is an indication of better gut health. Kiarie says by day seven, a chicken’s small intestine typically comprises about seven per cent of its body weight.

“The challenge with chickens is that they must be able to consume enough nutrients to form their gut in the first 10 days after hatching, and it takes almost three days after hatching for them to access their feed,” says Kiarie. “Our goal is for chickens to develop a more robust small intestine as quickly as possible so they can digest more food.”

Kiarie’s team fed groups of chickens diets containing four different concentrations of EGF. They compared their results with a control group — one that used antibiotics and one that did not. All chickens were fed their designated diets and brought to market weight.

“If you improve villi, chickens can express more enzymes, and if they express more enzymes, they should be able to digest more food,” Kiarie says. “The birds receiving EGF had healthier, heavier small intestines – but we saw no other advantages.”

In an unexpected twist, all birds – regardless of diet and the use of antibiotics – consumed the same amount of feed, from day zero to market weight. Kiarie notes that while the birds fed EGF had better intestinal health, all birds in all groups were physically identical. “We went back to the drawing board, to focus on the first 10 days,” Kiarie says. “And we wanted to represent farm conditions.”

As egg farmers, we’re committed to building a better tomorrow. From how we treat our animals, to how we work with our community, to how we care for the environment, sustainability colours every decision we make. It’s our job. It’s our way of life. And most of all, it’s our passion.

SUSTAINABILITY STARTS WITH CANADIAN EGGS

Visit eggfarmers.ca to learn more about our farming practices in our Sustainability Report.

Some fear last year’s extreme weather events that devasted B.C.’s poultry industry is a preview what’s to come as climate change worsens. Here’s how to prepare for that new reality

By Madeleine Baerg

Ask a British Columbian poultry producer to describe 2021 and you’ll likely hear descriptors like catastrophic and gut-wrenching. Together, an extreme heat dome event in late June and devastating flooding in November killed more than 1.2 million birds in the province’s poultry barns.

Though it’s not possible to attribute individual weather events to climate change, many fear 2021’s extreme events could well be a preview of a new, more violent weather reality. How can the poultry industry best prepare?

“The heat dome started on the Friday. When I came back to work the next week, all day Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, we were doing insurance claims for growers,” says Dr. Gigi Lin, a veterinarian with Canadian Poultry Consultants Ltd.

“They all died from heat prostration. The birds either died from heat stress directly or you saw layer production drop dramatically, especially in broiler breeder layers. It

was heartbreaking. As a veterinarian, there’s only so much I can do. I can’t change the temperature.”

The losses didn’t end when the thermometer finally dropped, Lin says. She diagnosed nine cases of blackhead in turkeys within two to six weeks of the heat event: an “unheard of” number, she says. Diseases like infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) spiked for the next six months.

“It’s hard to prove the direct correlation to the heat wave, but we do know that when birds are stressed, they’re more susceptible to disease,” Lin says. “So, it was a very significant event: first the direct impact, and then the triggering of diseases related to immunosuppression in the aftermath.”

Farmers left reeling from the heat-related losses had little time to recover before catastrophic flooding caused by ‘atmospheric river’ torrential rain occurred in November.

Sixty-one commercial poultry farms stood in the direct flood zone. In early December, the B.C. government reported the flooding had killed 628,000 chickens: birds either drowned in the floods or died when flooded roads left barns cut off from feed and other resources. Secondary losses mounted over nearly three weeks. With roads throughout B.C.’s primary poultry region flooded, the entire poultry supply and logistics chain backed up: hatching eggs couldn’t get to farms; processing-ready broilers couldn’t make it to market; even feed ingredients had no way to reach manufacturers.

Lin says that, though she hopes the heat dome and flooding event were one-time anomalies, she expects unprecedented natural events ahead.

“I don’t want to say a new normal, but a future challenge. We’re seeing not only in BC but also across the world that we’re having very abnormal natural disasters and natural events.”

To mitigate losses from future extreme weather as much as possible, it’s time to plan now. Not surprisingly, heat-stress related losses were highest in older, bigger birds; in older barns with lower ventilation; in barns with higher stocking density; and amongst conventionally caged layers.

“If we base infrastructure on the temperatures we’ve had in the past decades, it’s probably not going to be efficient or effective to keep our birds comfortable,” says Lin. “So, this is a good time before another extreme event to evaluate your ventilation system; evaluate your barn insulation. Talk to experts. Seek out a resource on barn design to make it easier for birds to withstand extremes.”

Joe Falk, general manager of Fraser Valley Specialty Poultry (FVSP), says his company lost about 14,000 of 250,000 birds during the heat wave.

“For that kind of heat to hit, especially in June, was just shocking and surreal. When it gets that hot for that long, even the water lines heat up. We had sprinklers going everywhere to try to cool the buildings, but there wasn’t enough

well capacity. It was tough.”

Falk says every new barn his company builds, including the three currently under construction, will have tunnel ventilation with a water curtain.

“Obviously, [the heat dome] did happen and, therefore, it could happen again. So, we want to definitely mitigate the losses there. And it just grows a better bird: it makes sense to do it,” Falk says.

New and new-to-here technologies may prove key to managing poultry in a changing climate. Some are already widely used: in regions more traditionally prone to heat like the the southern U.S., poultry barns often employ evaporative cooling pads to keep birds comfortable (though the resulting high humidity carries new problems).

Other technologies are brand new.

Dr. Bill Van Heyst, an adjunct professor in the University of Guelph’s School of Engineering, is currently studying whether geothermal energy might be a workable solution to cool incoming air during the summer and preheat it in winter.

Obstacles remain: in addition to making a economically viable geothermal system, he’ll have to overcome condensation issues that could lead to birds slipping.

“Geothermal is going to take some time. Right now, we’re at the theoretical stage in computational fluid dynamics,” he says. “What works in theory, you have to be careful in practice because there are a lot of other considerations you need to account for.”

Phase change materials – waxes

that can be added into walls to absorb heat during the day and release heat at night – may also prove an extreme temperature mitigating solution of the future, Van Heyst says.

“Climate change has been very slow, thankfully, but it is still progressing,” he says. “I think what we’ll see in the poultry sector is a slow but methodical inclusion of new technologies as they are demonstrated to give the benefits they claim. Producers should be looking at new technologies as they come available and doing cost-benefit analyses. In any of these technologies, a critical factor is that farmers can maintain profitability.”

Arguably, flooding is even more difficult for individual farmers to manage than temperature extremes.

Extreme weather by the numbers

49.6°C is the temperature some parts of B.C. hit during last June’s heat dome.

651,000 is about how many farm animals died as a result of the heat wave, the vast majority of which were chicken and other poultry.

14,000 is how many birds Fraser Valley Speciality Poultry lost during the heat wave.

November 15th is when the floods first hit B.C. A state of emergency was declared two days later.

628,000 is the number of poultry that died in B.C.’s floods.

$228 million is the size of the flood recovery program the federal and B.C. government announced in February to help the province’s farms return to production.

NEST is an online tool from Egg Farmers of Canada designed to help egg farmers monitor and improve their farms’ sustainability.

Though none of Fraser Valley Specialty Poultry’s barns flooded and they managed to keep all their birds fed during the November flood, Falk says they were “really close” to running out of feed.

“The flooding will definitely make people think a little more carefully for the next decade or two about how can we build land up more so it’s not as at risk, or build the dykes up, or use roads to channel flood water,” he says.

He and Lin both say a better crisis warning system is necessary to help producers make better forward-thinking decisions, like shipping nearly market-ready broilers and sourcing additional feed ahead of an extreme event.

“This was such a huge event,” Falk says. “It really brought to light that our system is fragile. As solid as we think it is, it’s actually very fragile. And so a major natural

event like that will wreak havoc and the weak spots will get found.”

As extreme weather events ratchet up producers’ – and consumers’ – interest in sustainability, managing a farm’s environmental footprint is increasingly critical. Now, there’s a new tool to help make doing so easier.

In February, Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) unveiled its new National Environmental Sustainability Tool (NEST) program, an online tool designed to help egg farmers monitor and improve their farms’ sustainability. The beta version currently available provides farmers with benchmarks by region and housing system for key performance outcomes that are known predictors of sustainability. In addition, NEST allows producers access to a variety

of resources to build sustainability.

The full version of NEST, scheduled for launch at the end of this year, will be a complete sustainability calculator that can translate a farm’s data into farm-specific carbon-, water- and land-footprints. It will also provide specific technology and management recommendations based on the location of the farms.

“For example, if a producer wanted to increase the amount of renewable energy that they were using, the tool would take into account the farm location, the availability of wind or solar energy resources, and the provincial electricity grid mix in order to calculate the environmental payback time of adopting that particular technology,” says Dr. Nathan Pelletier, NSERC/Egg Farmers of Canada Industrial Research Chair in Sustainability and the NEST project’s lead.

Past outbreaks make many fear reovirus. But there’s more than one cause of lameness.

By Lilian Schaer

Avian influenza is top of mind for Canadian poultry producers these days. Several years ago, though, it was reovirus that was causing problems for Canadian flocks. It’s a viral arthritis that causes inflammation of the leg joints. There’s no treatment and, although mortality from the actual disease is low, affected birds often have to be culled for various welfare issues.

In 2018, approximately 500,000 birds were affected in an outbreak in Ontario. B.C. poultry veterinarian Dr. Gigi Lin also recalls reovirus being a significant issue in western Canada during her first couple of years of practice starting in 2017.

“During that period, variant reovirus was very prevalent in Canada, especially in western Canada; it’s a virus that can cause severe tendon infection in broilers and cause severe lameness,” Lin says. “Reovirus has gone down significantly; in my practice, it has dropped over 95 per cent in the last several years and it is very uncommon as of today in B.C. in particular.”

The outbreaks have left lasting impacts on producers, though, she adds; so much so that it’s become common that when poultry farmers see lameness, their first thought often turns immediately to reovirus even when there are actually other factors causing the problem.

According to Dr. Tony Redford, an

avian pathologist with the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture based in Abbotsford, lameness is a top five health issue in Canada for poultry in general, and one he says is in the top three for broiler production.

Poor uniformity is an early indicator that something is amiss with a flock. Lameness could be the issue if birds aren’t moving around properly and an abnormal number of them are laying down or if feed or water consumption is down because birds can’t get to the feeder or waterer as easily.

“You don’t see birds dying if lameness is the primary issue. They would be more likely to starve, which takes time, so if you’re not getting a lot of dead birds, lameness should be high on the list (as a possible problem),” Redford says.

In live birds, lameness is relatively easy to identify, Lin adds, as lame birds won’t move away when they’re approached. In more severe cases, lame birds may use their wings as an additional support to help them get around. So, she recommends growers check any dead birds for bruising on the wing tip. Another spot to look at is skin and muscle on the breast; there will be more abrasions or bruising in this area if the bird had trouble walking. Birds with a condition called kinky back can be seen rocking back and forth with extended limbs.

Both veterinarians note that lameness in poultry has both infectious and non-infectious causes, but currently, mobility problems in birds mostly occur as a result

Get incentives to reduce operating costs and emissions

Whether you run a small poultry farm or a large egg production farm, improving energy efficiency can lead to significant reductions in costs and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Beyond energy savings, energy-efficient upgrades can also keep animals comfortable, clean and healthy— which will go straight to your bottom line.

As flocks are extremely sensitive to cold or uneven temperatures, heating equipment is one of the most important investments you can make. High-efficiency and condensing boilers can reduce heating costs and provide consistent, optimal temperatures to help birds grow and stay healthy.

More benefits

• Reduce humidity levels.

• Control temperatures with automated systems.

insulated barn can lose heat, drive up energy costs and make your heating systems work overtime. Adding roof and exterior wall insulation is an effective way to reduce costs through every season.

More benefits

• Increase resilience against severe weather.

• Maintain optimal temperature for egg production and bird growth.

• Prevent disease by keeping rodents and insects out.

Heat exchangers provide fresh outdoor air while recovering heat from outgoing air. This helps regulate indoor temperatures, and distribute conditioned air evenly throughout the space. It also prevents birds from clustering in one area, and mitigates fights.

More benefits

• Improve air quality and minimize contamination from bacteria, fungi and viruses.

The Industrial Custom Engineering program provides incentives for energy efficiency projects. The more energy-saving measures included, the greater your incentive and the lower your energy costs.

• Contact an Energy Solutions Advisor for help identifying opportunities.

• They’ll work with you to calculate or verify estimated savings and incentives.

• Implement the energy efficiency project.

• Receive an incentive to speed up payback.

• Up to $0.20/m3 for natural gas saved for general service rate customers.

• Up to 50 percent of the incremental project cost, to a maximum of $100,000. Based on estimated natural gas savings achieved annually.

Visit enbridgegas.com/ incentives to learn more.

Additional terms and conditions apply and can be found online at enbridgegas.com/experts or via your Enbridge Gas Energy Solutions Advisor. Projects must be pre-approved by Enbridge Gas. Volumetric savings are based either on Enbridge Gas approved engineering calculations or Enbridge Gas validated performance metrics. Enbridge Gas makes no warranty or guarantee regarding the estimated savings of any energy efficiency measure. Replacements of existing energy-efficient equipment do not qualify. High-volume projects will be reviewed on a per-project basis. All applications are reviewed by Enbridge Gas and require verification of eligibility, proof of purchase and installation. Incentives cannot exceed 50 percent of the incremental project cost and are only made available to customers where Enbridge Gas energy efficiency offer(s) have impacted the customer’s decision to proceed with theimprovement(s). HST is not applicable and will not be added to incentive payments. Programs are subject to change or cancellation without notice at any time.

© 2022 Enbridge Gas Inc. All rights reserved. ENB 800 06/2022 1. 2. 3.

• Reduce maintenance costs. Make insulation improvements

Insulation acts as a barrier to help keep warm air where you want it. A poorly

• Maintain consistent temperatures through a barn of any size.

• Control humidity levels to keep feed and bedding clean and dry.

• Increase appetites in flocks—they tend not to eat if it’s too cold or too hot.

The varied causes of broiler lameness

• Reovirus

• Septicemia

• Bacterial septic arthritis

• Systemic bacterial infection from the bloodstream like enterococcus, staphylococcus or E.coli

Non-infectious causes of lameness can be things like:

• Dietary or riboflavin deficiency that affects bone development

• Genetically caused bone malformations

• Management issues:

Litter conditions

Barn temperature and humidity

Ventilation, air quality and draftiness

of infections. This includes bacterial bone infection, joint infection, bacterial septic arthritis or a systemic bacterial infection coming from the blood stream, like enterococcus or staphylococcus.

Occasionally, Lin says, there will also be cases of a condition called kinky back. It’s a disorder where a vertebral deformity will cause spinal compression that gives birds hind limb paralysis. This will happen most commonly at the age of two and a half to three weeks and manifests in broilers as the birds gain weight.

Infectious causes will take some time to move through a whole flock, Redford adds, and not all birds will be affected. A bacterial problem like septicemia or systemic bacterial infection early in a bird’s life may not kill the bird but will stay in the joints or bones where it can cause longer-term issues.

Non-infectious causes of lameness happen due to a range of problems – both individual and multi-factorial. One that can be seen within the first week of a chick’s life is rickets, caused by nutritional deficiencies. Modern commercial poultry rations are very nutritionally balanced. So, while not commonly seen, it can happen because of mixing errors, for example.

Genetics can also play a role, sometimes causing bone malformations, but this too is uncommon. Management issues like soiled litter can cause physical damage on the foot pads of the birds. In addition, humidity can cause foot problems.

“Humidity and how wet it is in the barn can cause foot problems, although we don’t see that too often in broilers, more in older birds,” Redford says. “But it can cause higher bacterial growth in the litter and cause septicemia.

And a full barn clean-out can affect bacterial and viral carry-over.”

Treatment and prevention

Because there are a variety of possible causes of lameness, getting an accurate diagnosis is very important. Broilers, in particular, have a relatively short life cycle. So, any interruption in their feed intake or development will have an impact on their growth, and if it lasts even two to three days, they are unlikely to catch up, Lin says.

If young birds are showing severe lameness and unable to get to feed and water, they may be culled due to welfare concerns. If lameness is detected in broilers further on in the growth cycle, it is possible to get the birds to processing age, but they’re likely to have poor uniformity and/or be underweight so producers will be penalized.

“We do treatment and euthanasia of the current (affected) flock, but if it is recurring and there are no associations with external

factors or the breeder flock, then we look into management,” Lin says. “There are so many underlying causes of bacterial infection and there can be multiple factors. So, you must get to the bottom of recurring problems.”

CP_Jeni mobile_April21_MLD.indd 1

Staphylococcus, enterococcus and E.coli are common bacteria that can reach joints. Thus, where they come from is important, she adds.

The biggest portal is the gut. That’s why it’s important to avoid situations that can damage or impact gut health. That includes overheating at early stages in the brooding period, feed interruption or if birds get chilled.

Bacteria can also enter a bird’s system through the respiratory tract. Hence, Lin says to look at barn ventilation, temperature, draftiness, humidity and litter condition. In breeder birds, physical damage on the skin or hock is also a portal of entry.

Any concurrent immunosuppressive diseases, like bursal disease or bronchitis disease, for example, can also be a factor.

“The bottom line is look at it from a holistic point of view: how do you better equip the birds to be healthier?” Lin says. “Get a field service technician or a veterinary professional help. Sometimes it can take some time to sort it out.”

For about two decades, Canadian livestock farmers have used radio frequency identification (RFID) to track and trace animals. Hybrid Turkeys has adapted and integrated the technology into its breeding program, improving the rate, accuracy and sustainability of genetic progress.

“RFID helps us gather more information on our birds so we can make better decisions on which birds to keep in the breeding program to create the next generation,” says Jeff Mohr, protocol manager with Hendrix Genetics, the parent company of Hybrid Turkeys. “The work we are able to do through RFID to gather individual bird information is improving the overall level of genetic progress for turkey producers.”

Hybrid Turkeys offers breeding and commercial stock in Canada and around the world. It implemented the RFID technology at the pedigree level in Canada in March 2021, so all customers are now benefitting from the genetic progress the

company has made in its breeding program using the technology.

“Over the years, the cost of RFID technology has decreased and made it a more feasible option for other species, including turkeys,” says Mohr, who is part of the R&D team that works on the RFID technology.

“We were using bar codes to track feed efficiency and feed consumption, but now we can accomplish this more efficiently and sustainably with RFID.”

RFID represents a refinement on bar code technology, a simpler, less automated system used to track animal movement and gather production information. For Hybrid Turkeys, RFID technology delivers real time, accurate data on traits such as bird growth to enhance genetic progress, and signals a move to a more sustainable practices for birds and workers.

All turkeys in their breeding program are fitted with an RFID wing tag at the hatchery that tracks information throughout their lifespan to processing. Every time a bird steps on a scale or enters a feeding

station, they are pinged, and information is gathered on their feed consumption and live weight.

Accurately measuring feed conversion on an individual bird basis is the area most established with RFID technology for Hybrid Turkeys. “We can make better progress on feed efficiency with RFID because we have a larger population of data that gives us better validation to confirm what is possible with the birds down the road,” says Blair McCorriston, marketing manager with Hendrix Genetics.

“This greater level of accuracy helps ensure genetic progress and enhances the speed at which we can deliver improvements. This progress results in things like increased body weight with strong legs and livability and improved feed conversion for our breeder and commercial customers.”

The other win with the RFID technology for Hybrid Turkeys is that genetic progress comes in a more sustainable system,

Supporting strong flock protection through trusted in ovo technology since 1992.

As the pioneer of in ovo technology, it’s not that we’ve been around for 30 years but what we’ve been doing to support hatchery success. From defining in ovo vaccination best practices to partnering with customers to provide valued solutions, Embrex® has helped hatcheries globally through trusted technology, service and results.

Discover the Embrex® Innovation Story at Embrex.com/InnovationStory.

Signals shows the art of the incubation process. Based on the lookthink-act approach, it provides practical tools and insights to further improve and optimise hatch results, chick quality and offspring performance in a commercial hatchery environment. Hatchery Signals explains all factors that affect hatchability and chick quality. Starting at the breeder farm, the focus is on egg quality and

viability.

This research is funded by the Canadian Poultry Research Council as part of the Poultry Science Cluster which is supported by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative.

By Jane Robinson

Like many researchers in Canada and around the world, Doug Korver is exploring effective, practical alternatives to antibiotics in poultry production. His team at the University of Alberta are getting ready to feed fermented canola meal to broilers to validate the probiotic properties of this altered feed ingredient.

A professor in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences, Korver is part of a multidisciplinary team looking at antibiotic alternative, led by University of Guelph’s Shayan Sharif. Working with food microbiologist Dr. Michael Gaenzle, Korver and graduate student Vi Pham are heading into the final testing stage of fermented canola meal as a probiotic feed additive. “If we can work with something already in poultry diets that has a probiotic effect and brings other health benefits, that’s very promising,” Korver says.

Canola meal naturally contains a lot of phenolic acid – compounds with known antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. For the lab portion of the research project, Pham fermented canola meal by adding probiotic lactobacilli. “I used lactic acid bacteria to ferment canola meal and then extracted the phenolic acids,” Pham says.

The phenolic acid she extracted from fermentation was then added to poultry pathogens in the lab – Salmonella, Campylobacter and Clostridium perfringens. “The

good news is we learned that fermentation increases the antimicrobial activity of phenolic acid, compared to unfermented canola meal,” Pham says. “And this is important news for bird health and human health.”

Many prebiotics and probiotics are being explored to arm birds with better gut health for a stronger stance against infection. “What our research has shown is that by fermenting canola meal with lactobacillus bacteria, you are essentially converting the phenolic acid that is already there into more potent antimicrobial compounds that are naturally present,” Korver says.

For an antibiotic alternative to be successful,

it has to work in commercial production. While the team’s research looks promising in the lab, new alternatives must also be easy to incorporate into commercial operations. To get one step closer to that possibility, Korver and Pham are moving into the live animal testing portion of their work. They’ll be fermenting canola meal on a larger scale to incorporate into the daily diet of broiler birds.

Broilers will be fed diets that contain fermented canola meal for the trial work set to take place this spring/summer at University of Alberta research facilities. The team will collect digestive samples to look at the levels of microbes. “We’ll be looking to demonstrate that fermented

With Cobb Cares, we combine our mission of feeding the world and making a difference with our values of family, integrity, innovation and being the best. We emphasize five key pillars for our Cobb Cares sustainability story. As we focus on genetic progress, poultry care and welfare, community, environment and the workplace, we hope you’ll have a greater understanding of how Cobb is committed to a more sustainable future not only for our business, but for our team members, the communities that we work and live in and the global poultry value chain. Learn more at cobbcares.com or scan here:

canola meal is effective at reducing potential pathogens in the chicken gut,” Korver says. “We’re focusing on two human pathogens – Salmonella and Campylobacter – and a poultry pathogen – Clostridium perfringens.”

To test efficacy of the altered meal against Clostridium – the causal agent for necrotic enteritis – they’ll use a challenge model to induce necrotic enteritis and determine if

the fermented canola meal reduces the incidence and severity of the disease.

As a feed ingredient, they’ll also be calibrating how much of the fermented canola meal to add to the broiler diet. “We’ll test a few different levels of inclusion in the diet, and then based on the results we’ll be able to choose the optimal level for further testing,” Korver says.

They will look at the impact of fermenta-

tion on the nutritional characteristics of canola meal, and also track performance measures on the birds, including growth, feed conversion, nutrient digestibility and carcass yield.

Pham is also interested in evaluating the probiotic effect of the fermented canola meal. “The lactic acid bacteria I use to ferment the canola meal is a common probiotic with proven effects on humans and ani-

mals. So, I expect to find less Salmonella, Campylobacter and Clostridium by feeding fermented canola meal,” Pham says.

The main goal with any antibiotic alternative is not to eliminate bacteria from the gut or all troublesome pathogens, but to make it difficult for pathogens to establish, proliferate and cause problems.

“In our challenge model, we’re looking to create chaos in the gut to see how well fermented canola meal can reduce the chances for Clostridium perfringens to take hold,” Korver says. “When there is chaos in the intestinal tract, there is competition among the microbes and an opportunity for Clostridium to outcompete other bacteria.”

And that’s where probiotics come in. “It’s important to ensure the gut is stable and probiotics occupy ecological niches in the bird gut that prevent pathogens from establishing,” Korver says.

The big questions for Korver – and others searching for antibiotic alternatives – is how to come up with alternatives that are as economically efficient as possible so the industry can incorporate them. He knows there isn’t going to be one product that will work as well as antibiotics have, and that combinations and different strategies are probably the path forward. But it’s also why he is so encouraged by their results. “This work is so interesting because, in a single step, we have used two different mechanisms – the antimicrobial phenolic compounds inherent in canola meal and the lactic acid used for fermentation – to create a possible new alternative.”

While the fermentation process shows promise for unlocking the antimicrobial properties of canola meal, the research team know the process still needs some work as it produces a wet feed ingredient. If they can make it work on a small scale, and the live bird results show as much promise as the lab work, they’ll look at how to make it a practical process. That may include options for on-farm fermentation, as well as looking at the possibilities of a dry, stabilized fermented canola meal.

Depending on which chickens are being produced, broilers or broiler breeders, up to 70 per cent of the cost can be allocated to feed. With feed costs continuing to rise, minimizing feed waste is more important than ever. However, feed wastage isn’t just a cost issue.

Feed waste can be a biosecurity issue as feed spills can attract wild birds, rodents, beetles (alphitobius) and other vermin that can carry pathogens onto the farm. Moreover, the environmental footprint is enlarged when resources, including water, energy, and land, used to produce feed ingredients and feed are wasted.

Beginning at the feed mill, correct processing, preventing contamination and accurate formulation can help reduce feed losses. For example, incorrect processing can lead to pellets that are too hard, in which case birds may reduce or even refuse

to consume the feed. Similarly, milling feeds to the correct particle size and uniformity is also important because birds may select larger particles and leave fines.

Contaminated feed can occur during the milling process in places such as the mixer (carry-over) and post-processing (dust contamination). Depending on the severity, contaminated feeds can be reworked, or batches may even be completely lost. In the case of rework, time, labour and energy costs are increased.

Consider potential spillage points, as spillage is a direct loss. Accurate weighing is also important, because when feed ingredients are not weighed correctly, feed formulation will be incorrect. This may not lead to lost batches of feed but could have negative impacts on flock performance. For this reason, calibrate scales on a regular basis to ensure that ingredients are included at the correct percentage.

Good quality raw ingredients should always be used to produce feed. Poor quality

ingredients, such as corn contaminated with mycotoxins, will not only decrease the palatability, but also cause health issues. Rancid fats decrease feed palatability, reduce feed intake and absorption and induce poor uniformity. This is especially important in young chicks (first week), as a good start in rearing is important for attaining good performance metrics.

To prevent contamination during transport, it’s important to ensure clean trucks are used. Carry-over from previous loads can contaminate feeds with additives such as coccidostats. Trucks should also be completely dry before filling to protect feeds from moisture, which can lead to mould growth.

With mash feed, there is a possibility of particle segregation during transport, silo filing and feed distribution in the house. Particle segregation is an issue because birds may selectively eat large particles and

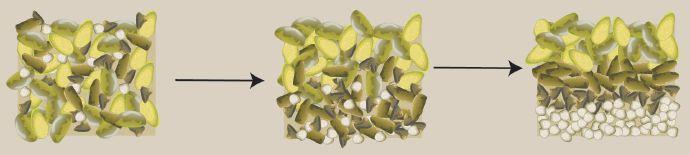

leave fines leading to feed waste and possible nutritional intake deficiencies. This segregation occurs when there is a big difference in particle size, shape or density and the feed is shaken (Figure 1).

Additionally, coarser feeds are more prone to particle segregation than fine feeds. However, making the feed too fine also has issues. Therefore, with mash feed, the average particle size should range from 1,000 to 1,100 microns. At this range, particle segregation will be minimized and good gizzard development is still supported.

Feed storage is important to preserve quality and prevent contamination. Silos for feed storage should be well-sealed to prevent rodents, wild birds, insects and vermin from contaminating feed. Well-sealed silos are also important to prevent moisture and mould related issues.

It is good practice to have at least two silos available per house so that one silo can be completely emptied before adding a fresh batch of feed. This will help prevent feed from adhering and accumulating on the silo walls, which over time can become moldy. Likewise, it is important that feed is cooled properly before filling the silos. If warm feed is placed in the silos, condensation can occur leading to mold issues.

Broilers

Considering that 70 per cent of the cost of raising broilers is feed, using the correct feeding system and ensuring that the feeding system is well maintained can be important for profits. There are several feeding systems available for broilers that work very well.

Recently, some European companies have been evaluating relatively small, round feeders that measure 18 centimetres in diameter. These feeders can be used for broilers up to four kilograms. Some field observations include:

• Flooding the feeders for day old chicks is easy and efficient.

• As of day two, no additional chick feeders are needed.

• Chicks cannot sleep inside, keeping the feed clean.

• Since the feeders are small, the birds empty them relatively quickly, activating the feeder line more often compared to large pans.

• Three levels of feed height in the feeder can reduce feed spillage.

• With these small feeders, the lighting program must be adjusted so that birds can eat ad libitum.

With broilers, a correct feed withdrawal program is also important and can help minimize feed wastage. Optimum recommended time for feed withdrawal is

eight to 12 hours (beginning when birds do not have access to feed in the poultry house until shackling at the processing plant). Less than eight hours may result in excess feed and fecal residues in the digestive tract.

This is a waste, as the undigested feed will not be converted to meat. The excess feed residue will also cause yield, processing and contamination problems in the plant. Feed withdrawal longer than 12 hours causes the intestines to lose their tensile strength, making them easy to tear and rupture during evisceration at the processing plant. This will cause carcass and equipment contamination in the plant.

Feeder management is an important factor to control feed wastage. When using pan feeders, ensure that feeders are locked and do not swing. Swinging feeders not only make it difficult for birds to access feed but feed can also spill out of the pans if they swing.

To prevent spills when using chain feeders:

• Check for worn feeder troughs and spillage at the return to the feed hoppers. Perform maintenance and replace worn out parts.

• Set maximum feed levels in the troughs at onethird full. When feed levels are set too high, feed can spill out of the troughs when chains are running.

energy to produce metabolic heat. If temperatures are too low, the birds will consume more feed to generate body heat to keep comfortable. Keep in mind that even with a pure heating fuel such as propane, it is still less expensive to heat with propane than with feed consumption.

• Chain feeders with high corners prevent feed from spilling out of the trough, which is the best option.

Determining how much feed to order for the silos before a flock is transferred to the production farm or at the end of the production cycle is also critical to minimize feed wastage.

In most companies, the excess feed is taken out of the silos and moved to another flock, which incurs costs. However, on many occasions, the feed is wasted. Timing, logistics and calculating the correct amount of feed is important, so that the least amount of feed is present when the birds leave the farm.

Birds consume, digest and absorb the nutrients from the feed. Nutrients then are used for maintenance, growth and/or egg production. The efficiency of digestion and absorption is dependent on a healthy gut and good water quality and intake. For

these reasons, poor gut health will reduce the bird’s ability to extract the nutrients, and, in turn, they will require additional feed to meet their genetic potential.

Specific to broilers, a high feed intake and fast passage rate means good gut health is necessary for optimal feed digestion and nutrient absorption. Disruptions in gut health can cause feed to pass undigested and deposited in excreta, which negatively impacts costs and generally impacts the environment on both the feed and poultry sides of production.

To support good gut health, biosecurity programs are important to minimize pathogenic challenges. Other points to consider include making sure drinker lines are clean and provide fresh, cool water. Keep the litter dry with good ventilation and correct any dripping nipples or water line connections.

When temperatures are below the thermal comfort zone, birds must allocate

For broiler breeders, it is important to follow the feeding programs recommended by your genetics supplier as overfeeding has consequences beyond feed waste. In addition to feed waste, over feeding birds can cause the following issues:

• Overfeeding pullets or having the wrong feed formulations can lead to extra breast muscle deposition and create complications such as early mortality after photo stimulation.

• Overfeeding hens can end up causing multiple ovulations, egg peritonitis, sudden death syndrome and a prolapsed cloaca.

• Overfeeding males will cause overweight males that have difficulties with mating. In this case, flock fertility can be negatively impacted.

Feed waste can come in many forms. There are direct wastage issues such as feed spills that can create losses beyond dollars including biosecurity risks. Use only good quality ingredients and preserve that quality by keeping feed stored under the correct conditions.

Producers must also consider feed consumption, digestion and absorption. That’s because feed that passes through the bird undigested has costs going all the way back to resources used to grow those feed ingredients.

Winfridus Bakker has 40 years of experience in poultry production operations. He joined the Cobb World Technical Services team in 2000. Winfridus is a Great Grandparent, Grandparent and Parent stock breeder specialist. He serves Latin America, New Zealand, Australia, and Central and Eastern Europe.

Location

Cookstown, Ont.

Sector

Layers

The business

Wardlaw’s Poultry Farm has been producing eggs since 1999. They also expanded into supplying feed mills with ingredients. The farm is run by Keith and Valerie Wardlaw, their son Brian Wardlaw and barn manager Gideon Courtney.

The need

The Wardlaws’ barn was too small to accommodate their quota. What’s more, they had conventional cages and needed to install alternative housing to comply with the code of practice for layers. Thus, a few years ago they decided to build a new barn. But first they spent a year visiting a few dozen farms across Ontario to see what other producers were doing. They then took best practices from that research and applied them to their own new barn, which they started building in the fall of 2020 and opened last spring.

The barn

The producers installed an enriched system from Hellmann based on good reviews they heard from other farmers. They also liked Hellmann’s lift system for collecting eggs. While many systems use a fixed position conveyer, Hellmann’s includes a mobile conveyer that moves from tier to tier. In addition, they worked with Glass-Pac on installing tunnel ventilation to provide a more comfortable environment for their flocks during the summer. “When it’s the warmest weather, you actually see the chickens at the front of their cages, wings open feeling the breeze,” Brian Wardlaw says of the new barn’s tunnel system.

Contact your local distributor or sales representative to find out more about Big Dutchman’s cage-free and enriched layer systems, ventilation equipment and more. Get the most ‘bang for your buck’ by investing in equipment from Big Dutchman

Looking to make an investment in new production equipment? Big Dutchman delivers innovation, quality, and has a proven track record to give you the most ‘bang for your buck’. Plus, you’ll have happy and healthy hens

Chicken Farmers of Canada has put together information and resources specifically for farmers. This resource portal includes everything from articles and videos to podcasts and case studies.

You can now access the Farmer Resource Portal right from the homepage of the chickenfarmers.ca website. You will find updated information on the AMU strategy, brooding, feed and water management, flock and environmental monitoring, necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis, and pathogen reduction.

information on antibiotic reduction and pathogen control on farm chickenfarmers.ca/portal