MODERN HYDRONICS FALL 2020

10 EXPANSION TANK POINTERS

OPTIMIZING EFFICIENCY WITH ECM CIRCULATORS

10 EXPANSION TANK POINTERS

OPTIMIZING EFFICIENCY WITH ECM CIRCULATORS

Navigating a ‘low carbon’ economy

RENEWABLE HEAT SOURCE CONTROLS

CONSTRUCTION CHANGES AFFECT DESIGN

4 EXPANSION

10 Details for expansion tanks

Reviewing important design and installation considerations for a closed-loop hydronic system.

BY JOHN SIEGENTHALER

EDITOR

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

ACCOUNT COORDINATOR

MEDIA DESIGNER

CIRCULATION MANAGER

PUBLISHER

COO

MH 8 DESIGN Unintended consequences

The impact of architectural changes on system design.

BY ROBERT BEAN

MH 14 GREEN ECONOMY

Gas fueled systems under fire

Governments are applying pressure on fossil fuel systems.

BY ROBERT WATERS

Optimal efficiency

Exploring the proper application and operation of residential ECM circulators.

BY MIKE MILLER

Product showcase

Doug Picklyk (416) 510-5218 DPicklyk@hpacmag.com

David Skene (416) 510-6884 DSkene@hpacmag.com

Kim Rossiter (416) 510-6794 KRossiter@hpacmag.com

Emily Sun esun@annexbusinessmedia.com

Urszula Grzyb (416) 442-5600, ext. 3537 ugrzyb@annexbusinessmedia.com

Peter Leonard (416) 510-6847 PLeonard@hpacmag.com

Scott Jamieson

MH 24 CONTROLS

Simple and repeatable

Controlling a renewable heat source combined with an auxiliary heat source.

BY JOHN SIEGENTHALER

Design and installation aspects to consider.

BY JOHN SIEGENTHALER

Water in its liquid state, like nearly all physical materials, increases in volume when heated and decreases when cooled. These actions occur at a molecular level. Although it may appear that more water is being “created” as a given volume of water gets heated, that’s not the case. The same number of molecules are present, they’re just taking up more space.

Since water molecules are very small, one might assume that thermal expansion is a “weak” effect. However, that assumption is very wrong. Any attempt to constrain molecular expansion will be met by tremendous forces.

If a strong metal container—such as a hydronic piping system—were to be completely filled with liquid water, sealed from the atmosphere, and heated, it would experience a rapid increase in pressure. If allowed to increase by further heating, the container would eventually burst, in some cases violently. That’s why all closed-loop hydronic systems must have a pressure relief valve.

Since we can’t mechanically “overpower” the expansion of water, we have to accommodate it. We need to give it something to “push” against when heated.

That something is a predetermined volume of air that stays within a closed hydronic system. The container for that air is called an expansion tank.

As the system’s water expands it

pushes against the air in the tank causing it to compress. When the water cools and contracts, the air re-expands.

Today, the most commonly-used expansion tanks use a highly flexible butyl rubber or EPDM diaphragm to completely separate the air and water inside the tank. This diaphragm conforms to the internal surface of the tank when the air side is pressurized (Figure 1)

When the system’s water is heated, the increased volume moves into the tank. The diaphragm moves toward the captive air chamber. The air pressure in the tank increases as does the water pressure in the system. However, if the tank is properly sized, the increase is small and not enough to cause the pressure relief valve to open.

Diaphragm expansion tanks can be sized using charts or software. A detailed procedure for sizing diaphragmtype expansion tanks is given in reference 1 at the end of the article.

There are several design and installation details that should be used to properly incorporate an expansion tank into

a closed-loop hydronic system.

Detail 1: Always make sure the expansion tank connects to the system close to the inlet side of the system’s circulator. This concept was correctly applied decades ago, but then slowly faded from practice as other installation “conveniences” seem to take priority.

The lack of attention to this detail is frequently the cause of chronic air entry into hydronic systems. Experienced hydronic technicians asked to fix systems that require frequent air purging know to check the placement of the expansion tank relative to the circulator inlet as one of the likely causes of the problem.

I’ve known of systems that suffered, from chronic air problems, but were instantly “cured” by repositioning the connection point of the expansion tank near the inlet of the circulator.

The point where the expansion tank connects to the piping system is the only location within the system where the pressure doesn’t change when the circulator is operating. This allows the differential pressure created by the circulator to be added to the static pres -

Navien... the PROVEN performer of highly engineered condensing tankless water heaters

Exclusive dual stainless steel heat exchangers resist corrosion better than copper

ComfortFlow ® built-in recirculation pump & buffer tank for NPE-A models

Easier installs with 2" PVC, 1/2" gas and field gas convertibility

Intuitive controls for faster set up, status reports and troubleshooting

Navien... the LEADER in high efficiency condensing tankless innovations since 2012

To learn why Navien NPE tankless is the best selling* condensing brand in North America, visit NavienInc.com

*According to BRG

sure in the system. Increased system pressure helps protect the circulator from cavitation and often allows for quieter operation. It also enhances the ability of air vents to eject air from the system. Figure 2 (below) shows acceptable placements of the tank.

Detail 2: It’s always best to install diaphragm type expansion tanks vertically with the piping connection at the top. This reduces stress on the tank’s connection relative to horizontal mounting. It also prevents air in the piping from getting trapped on the water side of the expansion tank when the system is first filled. The latter can occur when the tank is mounted vertically, but with the connection at the bottom.

Detail 3: The life of an expansion tank depends on system operating temperature, pressure, fluid chemistry and oxygen content. The higher the operating temperature, and the higher the availability of dissolved oxygen in the system’s water, the shorter the expected life of the tank.

When a tank fails due to a ruptured diaphragm or corrosion it’s relatively easy to replace IF the installer provided an isolation valve between the tank and where it connects to the system. Without this valve you may have to drain gallons from the system just to unscrew the failed tank and screw in a new one.

I suggest a ball valve for isolating expansion tanks. After the system is first commissioned remove the handle from this valve and store it somewhere in the mechanical room. This reduces the chance that someone might inadvertently close the valve and thus isolate the tank from the system.

Detail 4: Consider oversizing the expansion tank. The typical tank sizing calculations determine the minimum tank volume. Using a larger tank, although likely more expensive, is fine. Doing so reduces changes in system pressure as the fluid temperature varies. In systems without automatic fluid make-up, such as a circuit operating on antifreeze, extra fluid in an oversized expansion tank helps keep a newly commis -

sioned system operating at adequate pressures as the air separator removes dissolved air from the system.

Detail 5: Plan around the lowest temperature the fluid may achieve. In most hydronic heating systems expansion tank size and air side pressurization is based on the assumption that the cold fluid used to fill the system is in the temperature range of 45 to 60F. That’s fine in most space heating applications. However, when an expansion tank is used in a solar collector circuit, or a snowmelting system, the antifreeze solution will at times be much colder, perhaps even below 0F. If the tank’s diaphragm is fully expanded against the steel shell at a fluid temperature of perhaps 45F, any further cooling of the fluid will likely cause negative pressure in the system, and possible inflow of air from a float-type vent. Reference 2 explains how to correct for this possibility. The concept is to add sufficient fluid to the tank during loop pressurization so the diaphragm is not completely expanded against the inside of the tank until all fluid in the system is at the lowest possible temperature.

Detail 6: Adjust for antifreeze. Solutions of propylene or ethylene glycol have higher coefficients of expansion compared to water. The higher the concentration of antifreeze the greater the expansion volume required. The increase in volume for water heated from 60 to 180F is about 3%. The increase in volume for a 50% solution of propylene glycol heated from 60 to 180F is about 4.5%. This higher expansion rate should be accounted for when sizing tanks for systems such as snowmelting, solar thermal or other applications where glycol-based antifreeze solutions are used.

Detail 7: Never use a standard expansion tank with a carbon steel shell in any type of open loop application, such as a system that uses potable water to carry heat to hydronic heat emitters (which is a bad idea for several other reasons). The elevated dissolved oxygen content of the water will accelerate corrosion of the carbon steel shell. This limitation also applies to closedloop systems using non-barrier PEX tubing or other materials that may allow oxygen diffusion in the system. Expansion tanks with internal polymer linings should be used in any application where higher levels of dissolved oxygen could be present.

Detail 8: Don’t install expansion tanks directly below hydraulic separators. Doing so allows dirt collected at the bottom of the separator to drop into the expansion tank. Over time this could lead to failure of the diaphragm. If the tank needs to be near a hydraulic separator it’s best to mount it from a tee in either pipe connecting to the lower sidewall connections on the separator, as shown in Figure 3.

Detail 9: Whenever possible, avoid locating expansion tanks in proximity to very hot water. When the tank’s shell is heated the pressure of the air in the tank increases. This increases system pressure relative to a situation where the tank shell is cooler and may lead to leakage of the pressure relief valve.

Detail 10. Don’t leave an expansion tank vulnerable to impact. Small expansion tanks that hang from ½-in. top con -

4

nections can be easily bent by accidental impact. Ask me how I know this… If the tank must be mounted in a vulnerable location use a strapping system to secure the shell to a solid surface, as shown in Figure 4 (above).

Expansion tanks perform a simple but very necessary function. Follow these details to keep them functioning as intended. <>

John Siegenthaler, P.E., is a mechanical engineering graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and a licensed professional engineer. He has more than 35 years experience in designing modern hydronic heating systems. His latest book is Heating with Renewable Energy (see www.hydronicpros.com).

1. Modern Hydronic Heating, 3rd Ed., John Siegenthaler, Cengage Publishing 2012, ISBN -13: 978-1-4283-3515-8

2. Heating with Renewable Energy, John Siegenthaler, Cengage Publishing 2017, ISBN -13: 978-1-2850-7560-0

This case study illustrates the impact architectural changes can have on mechanical system design.

BY ROBERT BEAN

Over my career I have been fortunate to work with some great clients and design and construction teams where the relationship was not just about completing a successful project but also about education—that being the exchange of knowledge that one earns from challenging events. Any seasoned practitioners will tell you it is ‘project pain’ that provides the experience and any pleasure after that is just a bonus. This case study is an example of a ter-

rific client, an excellent team and a project with some interesting moments.

The 7,800 sq.ft. home (Figure 1) borders between climate zone 6 and 7 with a winter design temperature of -35F (-37C) and summer at 85F (30C). It had several common indoor environment quality (IEQ) challenges, initially including a six-burner gas range, a 6-foot (1.8m) gas fireplace in a great room that had a bank of windows extending 20 feet (6m) up from the floor, a gym and an attached garage that was big enough that it initially required CO monitoring. Several rogue zones had thermal comfort concerns due to large windowto-wall ratios and air quality concerns due to the attached garage, fireplace

and kitchen range combined with the required large exhaust hood. The latter adding a potential noise issue.

The five-person family reached out to us after an online search for healthy indoor environments introduced them to our website and services. After our introductory interview, project questionnaire and initial site meeting, it was clear our project values would work together.

We set out expectations and deliverables, which included consultation on the architecture, enclosure and HVAC design. Our thermal comfort and air quality targets were guided by ASHRAE Standard 55, and a mix between ASHRAE 62.2 and CSA F326.

We also conducted solar control and daylighting with several discussions on

external shading, window characteristics and performance.

From these initial discussions and agreement on critical enclosure improvements, our load calculations resulted in a dead-simple single low-temperature hydronic heating system (Figure 2) with reset using only the boiler controls and with only one circulator for the system and non-electric thermostatic control valves for room control.

It does not get much easier for such a large home. The harmonized temperature was established by manipulating floor tube spacing where possible, increasing radiant surfaces in rogue zones using wall space under windows (Figure 3), adding a trench heater for the great room, and increasing the surface area of the makeup air coils. This approach is preferred over a multi-temperature system, which adds more costs for controls and circulators, commissioning complexity and future maintenance issues for the owner.

At least this was the plan until what was discovered after approval for construction drawings were issued. During a site visit, it became apparent that the specified exterior insulation and radiant walls had been omitted, and additional windows had been installed.

As any professional practitioner can attest, such deviations from a stamped design is not a minor event. We advised there would be heating and cooling load penalties on most zones requiring a complete system redesign.

After getting approval for the additional engineering fees, we developed design version 2 (Figure 4). The consequences from the revisions resulted in the very system we had tried to avoid initially. The new calculations revealed a need for more complicated systems with multiple temperatures, which meant electronic controls and more circulators and a redesign on the partially installed distribution piping system.

It also meant an increase in the heating plant and cooling equipment and

distribution piping. We did not do a postchange cost analysis, but I suspect between our fees, the increase in capital costs, including the service fees from

Continued on MH10

the installer, would have paid for a big part of the omitted insulation.

Indeed, any balance would have been quickly offset by lower operating costs relative to the now higher loads.

The client was entirely professional about the hick-up, as were the trades, which helped make the changes flow without any conflict.

Ultimately the real consequence for the project is an increased load profile and more complex system. Fortunately, the final piping assembly was done the way I like them, plumb, parallel, level, and square (Figure 5 ).

Our ASHRAE Standard 55 assessment of several rooms, and specifically of the great room, showed potential for drafts, radiant asymmetry, and mean radiant temperature (MRT) issues due to the large bank of windows.

Our year-round solution, in addition to radiant floors, was to place a hydronic trench heater directly in front of the patio doors (Figure 6).

In the winter, this would provide a warm curtain of air to stop the down -

draft, warm the glass and improve the asymmetry. Also, a preheat coil on the HRV/kitchen exhaust make up air unit could be used for supplemental heat.

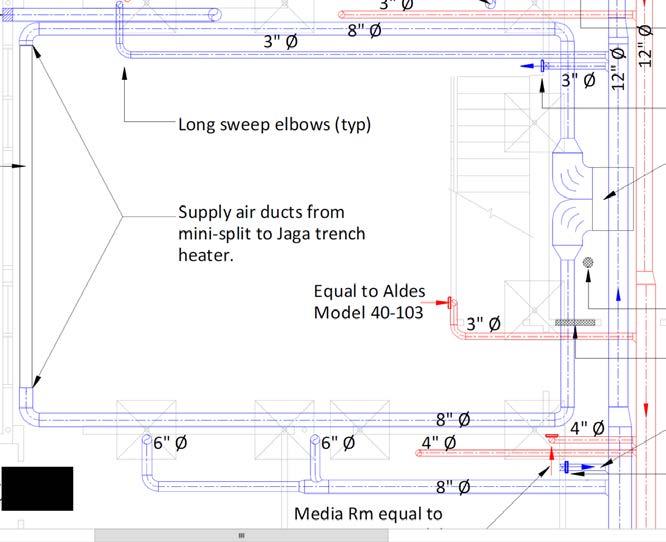

For cooling, we used a ducted minisplit and fed its cooled air into each end of the trench heater, and we used its linear fans to boost the airflow up the glass (Figure 7 ). This cooled the inside surface temperature of the glass, reducing the asymmetry and MRT issues.

In combination with elevated airspeeds from a large ceiling fan, the room fell within compliance with ASHRAE Standard 55.

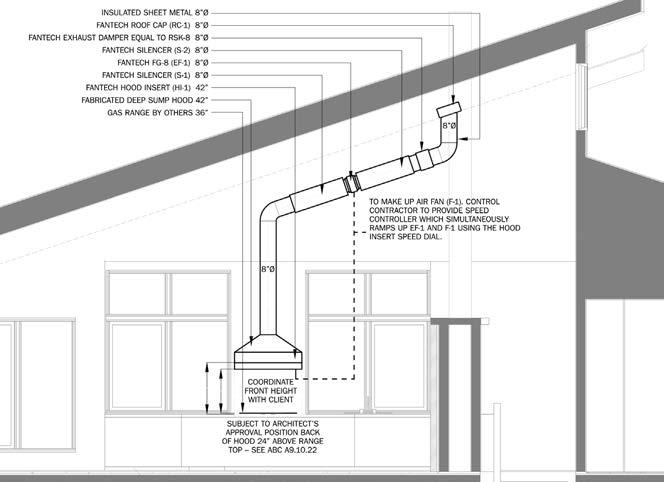

Next up was how to provide up to 800 cfm (378 l/s) of kitchen range exhaust with makeup air, and up to 400 cfm (189 l/s) of home ventilation air with a single air handler.

In either operation, the sound from

airflow had to be minimized. Our kitchen exhaust solution was an inline direct drive exhaust fan with silencers on the inlet and outlet. The fan was located about 20 ft (6m) away above the range in the attic space. A strategy I have used many times with excellent results (Figure 8).

The building ventilation was a multispeed HRV whose exhaust fan was disabled by controls when the kitchen exhaust fan was on (Figure 9). Thus, without exhaust flow, the HRV became a makeup air unit.

Preheating the air in both modes was a generously sized glycol coil. Home ventilation ducting was designed for low velocities from 200 fpm (1.0m/s) up to 500 fpm (2.5m/s) and kitchen exhaust from 1000 fpm (5.0 m/s) up to 2000 fpm (10m/s).

Continued on MH12

The control solution is proprietary, but I will take this opportunity to strongly suggest that manufacturers of both kitchen exhaust fans and HRV’s develop an integrated solution for speed matching their products and disabling the HRV exhaust fan.

Through the integrated design process, thermal comfort, lighting, sound, and in -

door air quality criteria should be first and foremost passive solutions.

Thus architecture, enclosure and interior design are the first solutions to indoor environmental quality challenges. These “three amigos’” when adequately designed simplify electrical and mechanical systems and their associated commissioning, maintenance, capital and operational costs.

Far too often energy conservation is ig-

nored, forcing designers to unnecessarily use the brute force of energy in the form of heat and electricity to solve IEQ problems. There is also a failure to use design solutions like harmonizing fluid temperatures to the lowest common denominator to enable higher system efficiencies.

In this case, the original intentions were good but were destroyed by what was thought to be an inconsequential decision.

As we have said before…in design –everything matters.

***

Considering the current pandemic there are no words to describe how comforting it is knowing our engineering philosophy of ‘designing for people’ has left behind indoor spaces that are serving our clients with excellent independent and dedicated air quality and thermal comfort systems. For the naysayers of days past – I told you so…there – I said it! <>

For more on ASHRAE Standard 55, interested practitioners can obtain for no charge a new book on Thermal Comfort Principles and Practical Applications in Residential Buildings. This project was funded in partnership with BC Housing and can be accessed through this link: www.linkedin.com/groups/13843486/

Robert Bean is director of www.healthyheating.com, and founder of Indoor Climate Consultants Inc.

He is a retired engineering technology professional (ASET and APEGA) who specialized in the design of indoor environments and high performance building systems.

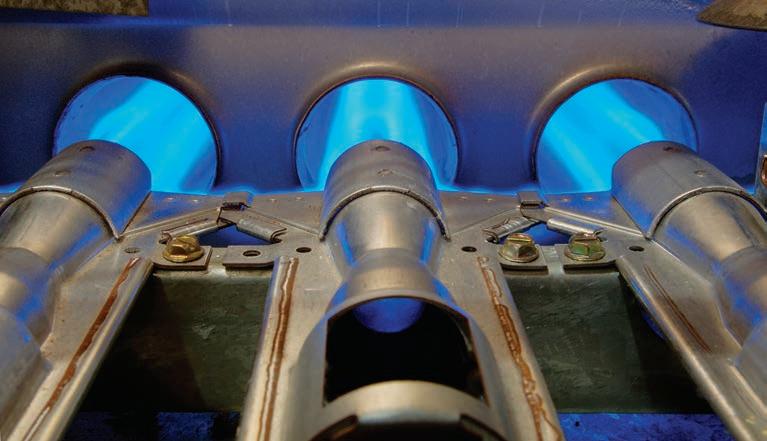

The Brute FT® Combination Boiler and Water Heater utilizes the latest in fire tube technology to offer your customers:

• Exceptional Efficiency. The Brute FT®’s modulating technology automatically adjusts fuel usage to match heat demand – to help your customers save on heating utility bills compared to standard “on-off” boilers! ENERGY STAR® rated, 95% AFUE.

• Outstanding Performance with Higher Flow Rates (4.8 GPM at a 77°F rise). The Brute FT® Combi has a shell-and-tube domestic hot water heat exchanger that gives your customers unrestricted flow and better performance than brazed plate heat exchangers.

• Quicker Hot Water Delivery. The Brute FT® combines storage with on-demand hot water for faster performance.

• Compact Design. Easy to install and service, even in tight spaces.

• Excellent Flexibility. The Brute FT® is field convertible between natural gas & propane, is cascadable up to 20 units, and can be vented with PVC, CPVC, or polypropylene.

To learn more about the Brute FT® Combi, visit bradfordwhite.com

Drive to reduce greenhouse gases is putting pressure on fossil-fuel-fired mechanical equipment.

BY ROBERT WATERS

The push is on from many levels of government to go “low carbon”, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and address climate change. The HVAC sector is part of this push and one result is that traditional oil and gas-fired heating equipment is under pressure. Governments would like to see this equipment become extinct. What does this mean for the hydronic industry and contractors?

There are several examples of recent government policies indicating that traditional fossil fuel heating equipment in Canada may be on the way out. Space and water heating equipment are certainly being targeted due to the fact that residential and commercial buildings account for 17% of total greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Space heating represents 56 to 64% of the energy use in homes and buildings, and water heating represents 8 to 19% of the energy use.

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change outlines the commitments of the federal, provincial and territorial governments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote clean, low-carbon economic growth for Canadians. These governments have set aspirational goals for energy-using heating equipment in the building sector that reduces greenhouse gas emissions significantly.

To support the transition to a low-car-

bon economy, governments approved the “Market Transformation Road Map for Energy Efficient Equipment in the Building Sector” at the Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference in August 2018. This plan sets short- and long-term goals for space and water heating equipment.

The short-term goal requires that by 2025 all fuel-burning technologies for space heating for sale in Canada must meet an energy performance of at least 90% (condensing technology).

The long-term goal states that by 2035 all space heating technologies for sale in Canada meet an energy performance of more than 100%. This goal would see the transition of the entire space and water heating market to heat pump technology or integrated gas absorption heat pump systems.

These ambitious goals still have a long way to go to become reality, however the writing seems to be on the wall … traditional fossil fuel boilers, water heaters and furnaces are under threat of being phased out.

The City of Vancouver is one jurisdiction that is taking greenhouse gas emission reduction very seriously. Vancouver’s “Renewable City Strategy” has set a longterm target to have all buildings in the city (including those already built) use only renewable energy by the year 2050. Vancouver has a head start on most jurisdictions around the world as its electricity supply is already close to 100% renewable. BC’s grid is over 97% renewable due to hydroelectric generation and therefore has very low GHG emissions. As a result, while electricity conservation remains important, the focus of the Vancouver plan is on reducing the demand for fossil fuel space heating and hot water heating. The plan is to transition these functions to renewable sources such as electricity and bio-gas.

In July 2016, Vancouver moved its plan forward by introducing their “Zero Emissions Building Plan” which requires the majority of new buildings in Vancouver to have no operational GHG

emissions by 2025, and all new buildings have no GHG emissions by 2030.

Under this plan Vancouver introduced the “Green Buildings Policy for Rezoning’s” in May 2017, which targeted new high-rise multi-unit residential buildings. The latest bylaw amendment from May 2020 will require all new residential buildings three storeys and under to install zero-emission space and water heating starting in January 1, 2022.

The next step is anticipated in 2025, when both new and replacement heating and hot water systems must be zero emissions. The city anticipates this shift towards zero emission space and water heating will be met with heat pumps.

Vancouver is predicting that air-to-water heat pumps are likely to be a common heating solution for new single-family homes, as over 90% of typical single-family homes built in 2019

were heated with hot water. Water heaters will need to be electric resistance or heat pump water heaters.

The City of Toronto's “TransformTO” plan includes a set of long-term low-carbon goals and strategies to reduce GHG emissions, improve health, grow the economy and improve social equity.

Toronto aims to achieve Net Zero builldings by 2050. The plan has targets for all new buildings to be built to produce near-zero GHG emissions by 2030. By 2050, all existing buildings will have been retrofitted to improve energy performance by an average of 40%. Toronto has not yet introduced any low-carbon equipment requirements.

There are immense challenges and barri-

ers to reach the goals set by these new policies. For low-carbon or zero emission equipment, the market transformation roadmap outlined by the Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference outlines the “five A’s of market transformation”:

• Availability: Does the technology exist?

• Accessibility: Does the market have access to the technology?

• Awareness: Does the market know about the technology?

• Affordability: Is the technology affordable?

• Acceptance: Is the form, fit, and function of the technology acceptable? There are several examples of lowcarbon space and water heating equipment that are currently being utilized in the Canadian market. Space heating systems can utilize electric resistance heating systems such as baseboards, Continued on MH16

forced air furnaces and hydronic boilers. All of these products have been available and accessible for a long time, and offer affordability, public awareness and acceptance. The main issue that resistance heating has working against it is the high cost of electricity in many regions of Canada.

Heat pump options include both air and ground source (geothermal). Heat pumps are much more efficient than resistance electric, typically providing 2 to 4 times higher efficiencies. Air source and geothermal heat pumps are available to either provide heat to a forced air distribution system or to a hydronic heating system. Both air source and geothermal systems have high water temperature limitations, with neither type working very effectively above 140F.

Geothermal heat pumps provide the highest possible operating efficiency, with consistent year-round performance, but also have the highest installation cost due to the expense of adding vertical or horizontal ground loops.

Air source systems have good performance when outside temperatures are mild, however they can see a significant drop off in performance when the ambient air temperature drops much below -15C. Heat pumps have been around for many years, but the market for the different types has fluctuated based on performance issues (air source) and government subsidies (geothermal).

Air source heat pumps have seen a resurgence in recent years, especially in the Atlantic region. Heat pumps are widely accessible and generally have good market awareness, however barriers still exist with affordability (especially geothermal) and acceptance.

In their market transformation roadmap National Resources Canada (NRCan) identified a number of challenges and barriers to transitioning to low-carbon ground source, air source and gas heat pumps. These include technical barriers such as: the perfor-

mance of air source heat pumps at low ambient temperatures (as mentioned), a lack of standardized test procedures for rating the energy performance of airsource units, high cost for installation of geothermal, retrofit challenges that will add cost and require additional components and controls, variability of commercial building stock and the challenges in remote communities.

They also identified market barriers that include product availability and training requirements for designers, contractors and building owners. Governments envision gas absorption heat pumps playing a major role in the future for low-carbon heating systems, as they may offer a significant increase in performance beyond that of existing gas-fired heating systems. However, they still face barriers to availability, accessibility, awareness, affordability and acceptance because they are not yet commercialized in Canada.

Two big stumbling blocks to a full lowcarbon transformation across Canada are the affordability and availability of electricity supply.

While energy costs vary in different regions of Canada, the reality in most areas is that the cost of electricity is much higher than natural gas. Carbon taxes will gradually increase the cost of natural gas, with the federal carbon tax prices currently at $20/tonne, rising to $50/tonne by 2022.

Natural gas still remains abundant and inexpensive in Canada however, and even with the carbon tax added on will likely remain the preferred choice in most areas for years to come.

Natural gas is currently widely available and serves over 7 million customer locations and over two-thirds of Canadians. There are currently over 570,000 km of underground transmission pipes bringing natural gas across the country.

A transition to high levels of mandated electrification will require a costly expansion of Canada’s electrical infrastructure. Presently only 20% of our energy requirements are met by electricity.

With all of these challenges the transition to low-carbon equipment will likely hit speed bumps along the way. The economics alone will make it difficult to convince consumers to change from natural gas to more costly electricity.

Transitioning to heat pumps will require expensive retrofit costs and electrical service upgrades for many buildings. Finding space to add the heat pump outdoor condensing may be difficult for buildings with tight building lots. Added noise from the outdoor units is something customers will have to get used to.

The mechanical industry will have to transition as well, with new equipment and installation techniques to learn. These hurdles will require intensive marketing and information strategy from governments, utilities and the HVAC industry to get consumers on-side.

While the transition may appear difficult, the benefits of reducing GHG emissions cannot be overlooked. Phasing out millions of fossil fuel fired heating units is one of many actions required to enable Canada to reach its emission reduction targets. This transition should create a boost in economic activity, requiring skilled workers and create demand for new equipment.

This will certainly benefit the HVAC industry, and the reduction of GHG emissions will certainly benefit the planet. <>

Robert Waters provides training, education and support services to the hydronic industry. He has over 35-years’ experience in hydronic heating and solar water heating. He can be reached at solwatservices@gmail.com.

150% wider waterways - Wider pipes allows water to pass through the heat exchanger more effectively, with less risk of blockages.

• Onboard Wi-Fi provides remote control and monitoring

• Up to 11:1 modulation

• Up to 96% AFUE

• Heat only and combi versions

• Integrated ECM pump and diverter valve on all models

• Whisper quiet

• Small zone valve systems may not require primary/secondary piping

DEPENDABLE BY DESIGN.

A ll of our products feature NTI’s legendary combustion stability, durability and preformance.

Exploring the proper application, operation and commissioning of residential ECM circulators.

BY MIKE MILLER

Iabsolutely believe that the electronically commutated motor (ECM) circulator is as significant to this industry as the modulating condensing (ModCon) boiler was when it arrived and still is. Just knowing that the circulator has the ability to adjust the flow of the system to better match the current load condition is awe-inspiring.

The circulator, which has always been an important part of the hydronic system, now “dovetails” with the heating equipment to raise the overall system efficiency, and not just the reduction in wattage consumption (full speed comparison of approximately 50% when compared to a traditional PSC motor), but also the lower return temperatures, longer equipment run times—longer steadystate efficiency, and with the turn-down ability of Mod-Cons, being able to reach and maintain the “thermal equilibrium” for longer time periods.

I have seen results of ECM circulator trials for well over a decade and they have always passed scrutiny. In 2015 a colleague replaced a delta-P controlled system circulator with a ‘newer’ delta-T unit. He used the same model circulator as his condensing boiler primary circulator and both of them were operating at a fixed delta-T of 30F.

He reached design temperature twice that season (~11F). His typical watt consumption on the boiler circ went from a fixed 80 watts (spd. med.) to something typical of 11 watts. And the bigger deal, his boiler return temperature was at its

lowest average ever.

We know ECM circulators deliver efficiencies, but it’s important to understand how to properly apply and set the correct mode of operation.

Most current residential ECM products have multiple operating modes: fixed speed (FS), constant pressure (CP), proportional pressure (PP) and some have an additional “Automatic” mode (which is also a PP mode) and some use “Delta T” (the ultimate Auto mode), and all of them, if applied correctly, can result in the highest overall efficiency.

Fixed Speed (RPM) mode: (non-automatic) The fixed speed mode is appropriate when the application will not have changes in the operating points (varied hydraulic pressures down-stream of the circulator) like zone valves or actuators opening and closing. Examples of proper application of the fixed speed mode would include: single zone pumping, boiler circulator in a P/S piping configuration, DHW heat exchanger, pool or spa

heat exchanger, snow/ice melting etc. (see Figure 1)

Constant Pressure mode: (automatic) The constant pressure mode is suited for the traditional North American piping scheme; these are typically multiple zone systems using individual zone valves or actuators on a preassembled manifold with a “system” circulator. The distinguishing difference of this layout is the paralleled supply and returns that run to and from the “near boiler piping” header in the mechanical area. This has also been called a “Home-Run” configuration. (see Figure 2)

Proportional Pressure mode: (automatic) The proportional pressure mode is best suited for the “extended header” piping scheme. The distinctive difference of this layout is the supply and return piping is extended out in the building, and the branches/take-offs are out there as well. These multiple zone systems could be a mixture of different zone operating devices or terminal units such as: fan coils, fin-tube baseboard, cabinet unit heaters or simply several hydronic radi-

ant floor manifolds. All these heat emitters could be controlled by different devices: on/off zone valves, actuators, modulating valves, mixing valves or diverting valves. (see Figure 3, next page).

The primary benefit of ECM circulator technology is that it offers much more “controllability”. It allows complete control of the speed and direction of the circulators, and therefore complete, or more precise, control of the flow of hydronic systems.

The ECM also provides the capability to control the power consumption, and it allows the ability to know when something is wrong with the circ or motor. This information can be used to quickly assess a situation and make changes to the signal, its speed and its direction, or completely shut the motor off.

As previously discussed, I have looked at results from two particular different circulator input control methods; delta T (temperature differential) and delta P (pressure differential).

Delta P (∆P) controlled circs make their adjustments to the speed (rpm) based on what they feel. Things change in a multiple zone system “hydraulically” when zone valves close and open back up, or TRV’s squeeze close. So the mo -

tor feels these hydraulic changes within the system and can ramp down or back up depending on what is required at a given time. No special sensors or pressure transducers are required. Since hydraulic changes in the system can be felt almost instantly, the reaction time in a ∆P circ is very quick.

Delta T (∆T) controlled circs make their adjustments to the rpm based on what they measure. They look at feedback from two separate thermistors, one on the supply piping out to the system and the other on the return piping. When powered, these sensors constantly measure the temperatures and will ramp the circ’s motor down or up to maintain the “designed for” ∆T.

The ∆T is what you use in a flow rate (gallons per minute, GPM) calculation: GPM = Btuh / ∆T x 500; so to use a very important segment of this calculation to control the flow in a residential hydronic system can make sense for many applications. Since temperature changes in the system can take a little while to sense, the reaction time in a ∆T circ is a bit longer than a ∆P circ.

Fixed speed “non-automatic” mode is fairly straight forward as far as the piping

scheme goes so no additional explanation needed there. But a common question is, ‘Which “automatic” operating mode should the circulator be placed in; constant pressure (CP) or proportional pressure (PP)?

The answer relies on how the system is, or will be, piped.

When a system is piped with parallel supply and returns brought back to the boiler as illustrated in the constant pressure mode example (Figure 2), one of the zones will set the maximum pressure drop (PD) required (plus a little for the near boiler piping and incidentals). The system circ still needs to be able to achieve the pressure drop requirement of that single zone, the one that set the PD target.

When the other zones close in the system, the GPM can drop dramatically (due to the circ’s ECM responding to the hydraulic change) but the head requirement is still based on the zone that set the PD target.

CP mode will always try to maintain a “Fixed” desired head setting. For example, one model in the CP Mode has three fixed operating range settings: 5ft./hd, 10ft./hd and 15ft./hd. To select the right head setting requires some educated calculations/estimations. It’s always best to calculate the PD of the system so the correct setting can be used, but here’s a rule of thumb for generalized purposes: 5ft.= baseboard, 10ft.= typical radiant and 15ft.= fan coils or other high PD applications as long as the GPM requirement for any of them can be met.

Another point to understand, the circulator operating in CP mode will only slow down “automatically” if the system’s pressure drop from PVF (pipe valves and fittings) can induce enough resistance to maintain the particular head setting.

If you over estimate the PD of your system, let’s say you choose 15ft. head but the system will only impart 12ft., the circ will simply run out on its maximum rpm curve and it will not automatically

slow down. (It’s better to slightly underestimate/round down in the CP mode)

So as zone valves close in the system, the circulator’s EC motor senses that resistance change then adjusts the rpm of the motor to a lower speed, hence the flow decreases but the motor speed will work to maintain the desired head setting.

PP mode is similar to the CP mode however it uses a “proportional” reset adjustment. As the PD in the system increases due to hydraulic changes (valves closing etc.) the EC motor senses those changes just as it did in the CP mode and will lower its speed but with a slight difference, it moves the head setting downward on a slight decline or pitch from what it was at max rpm.

The manufacturer sets up control logic in the circ’s microprocessor to a predetermined percentage of decline slope. For example, one model of ECM circulator in PP mode has three operating ranges: low, med or high. That means from a maximum head/GPM point on any of the three settings the performance range slopes back at 58% as it approaches ‘0’ GPM. The operating range slightly declines so that when the circulator senses hydraulic resistances it slows down and lets the head reduce along with the GPM.

Now with what I’ve covered in regards to CP and PP control options, let’s go back and think about a potential negative scenario. Picture a typical North American parallel S&R piped system, zoned with zone valves served with an ECM system circulator, similar to Figure 2, but that circ is set to run in a PP mode.

Under conditions approaching outdoor design temperature, this configuration may not give you the GPM and head required for a specific zone calling on its own. Recall that in PP mode the circ motor is working to lower its head based on a reduction in GPM requirement.

I’ve heard of people being called out for a “low or no heat call” when it was at or approaching design temperature. They’ve said the ∆T across certain zones was

stretched way out and the quick fix was to change from PP to either CP or FS.

Delta T controlled system circulators are the easiest to discuss. The sensors, if located and installed correctly will read the system’s temperature differential in “real-time” and adjust the motor speed accordingly. It will keep the ∆T at the “designed for” condition depending on the model, from 5F to 50F in one degree increments, typical settings of 20 to 30. (see Figure 4)

My hope is that the information in this article helps you better understand the

application, operation and commissioning of residential ECM circulators. As you apply this knowledge we all win because our collective “systems” get better and more efficient.

A special thank you to Rick Mayo, Taco Comfort Solutions products and applications instructor, Western Region, for his enormous contribution to making this article happen. <>

Mike Miller is director of sales, commercial building services, Canada with Taco Inc. hydronicsmike@ tacocomfort.com

From heating controls to mixing valves, Resideo offers a full range of Honeywell Home hydronic product solutions. Find Hydronic Zoning Panels, Pro Press Zone Valves, T6 Pro Hydronic thermostats and more — all in one location.

Our reputation is based on providing you with products to provide homeowners with solutions. Our products have proven to be must-stock standards, engineered for accuracy, safety and reliability — and easy installation.

Webstone has expanded its line of transition products including Press × PEX reducing fittings, baseboard elbow and dual-vent elbow for use with a choice of 1/8-in. NPT vents. The dualvent design ensures an upright vent port is accessible. Ideal for boiler risers or baseboard radiator installations, each elbow includes a brass stiffener for copper finned tube press connections. Products are lead free and available for F1960 or F1807 PEX. webstonevalves.com/PEX

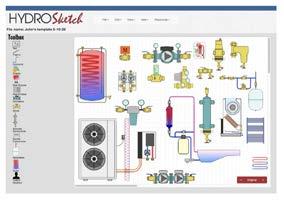

HydroSketch, a cloud-based software tool for quickly creating piping and electrical schematics for hydronic heating and cooling systems has introduced several enhancements. Developed by Appropriate Designs, the tool now has over 50 new component symbols for devices such as magnetic separators, air-to-water heat pumps and specialized buffer tanks. A growing library of “templates” also serve as starting points for basic hydronic schematics. A free 30-day trial is available. hydrosketch.com

The RBI Torus commercial water tube condensing boilers and water heaters come in sizes from 1250 - 4000 MBH. Torus Boilers are up to 97.5% AHRI Certified efficient. Torus units feature a 5:1 turndown. The heat exchanger is made from 316L stainless steel and manufactured through tube hydroforming. The 4-pass design works with a multi-channel manifold and increased tube diameters resulting in ultra-high efficiency with very low pressure drop. rbiwaterheaters.com

A new addition to Calefactio’s hydraulic separators product range is the 2-Zone Calbalance. Hydraulic separators isolate primary circuits (boiler) from secondary circuits (application/heat transmitters). The 2-Zone Calbalance allows the connection of two zones directly. The unit is equipped with the Calvent automatic air vent. Housed in carbonized steel, it's provided with a wall bracket. Maximum operating pressure is 150 psi, and the maximum. operating temperature is 100C. calefactio.com

SFA SANIFLO Canada has introduced Sanicondens Best Flat, a low-profile condensate pump with a 0.9-gallon tank capacity and capability to serve multiple mechanical systems, up to a total of 500,000 Btu/hr. The 12-lb. unit combines a condensate pump with a pH-neutralizing pellet tray and can be installed on a level floor or wallmounted. The unit can discharge condensate 15 feet vertically and 150 feet horizontally. saniflo.ca

The iDROSET CSD series of static balancing valves from Watts offer contractors speed and ease when balancing a hydronic system. Its patented flow measuring technology allows users to set and read flow without additional tools. The valve’s gauge continuously indicates flow without the need to actuate a bypass circuit. A twist of the hand wheel sets flow and can be locked when the desired rate is set. watts.com

HYDROFOAM® IS THE IDEAL RADIANT FLOOR INSULATION PRODUCT FOR RESIDENTIAL AND COMMERCIAL CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS.

The floor of a building is often the most ignored surface when it comes to insulation. The floor, when insulated with HYDROFOAM, completes the building envelope and increases comfort and energy efficiency.

HYDROFOAM maximizes radiant floor heating by ensuring the heat is dispersed evenly throughout the entire floor area, providing building occupants with a comfortable living and working environment.

Controlling a renewable heat source combined with an auxiliary heat source.

BY JOHN SIEGENTHALER

Over the last 40 years I’ve had the opportunity to work with several types of renewable energy heat sources including solar thermal collectors, cordwood boilers, wood pellet boilers and heat pumps. They can all be integrated with hydronic heating distribution systems.

I’ve also worked with systems that took advantage of timeof-use electrical rates. or “off-peak” rates. During specific times of day, usually at night, and sometimes specific dates (e.g., weekday, weekend, holiday, etc.) the cost of purchasing electricity from the local utility is deeply discounted. Utilities do this to help manage peak demand by incentivizing the purchase of electricity at times of low demand.

So what do renewable energy heat sources and time-of-use electrical rates have in common? The answer is that systems using these energy sources almost always require significant thermal storage. For hydronic applications that storage consists of a large insulated tank filled with water.

Thermal storage tanks can be categorized as unpressurized and pressurized. Unpressurized thermal storage tanks must be vented to the atmosphere, usually through a small opening. This ensures that the pressure at the water’s upper surface cannot increase.

These tanks usually consist of an open-top insulated structural shell that’s assembled on site. A flexible liner made of EPDM rubber or polypropylene is placed into this shell, similar to how a trash bag fits into a trash can. The liner contains the water. An insulated lid goes over the top. Piping penetrations are usually made just above the highest water level in the tank.

A pressurized thermal storage tank, such as the 350-gallon tank shown in Figure 1, are usually constructed of steel. They can be insulated using several types of materials. That insulation is usually installed after the tank has been piped and all connections to the tank have been pressure tested.

Most mechanical codes require pressurized tanks larger than 119 US gallons to be ASME certified. This process involves traceable materials and physical inspections during fabrication. It adds assurance that the tank is well built and safe, when applied within the certification limits. It also adds significant cost to the units.

Systems using a thermal storage tank heated by a renewable source or off-peak electricity usually have an auxiliary heat source. In retrofit applications that auxiliary heat source is often an existing boiler. In new systems it could also be a boiler or a heat pump.

The control concept is to use heat from thermal storage whenever possible, and only use the auxiliary heat source when necessary to ensure the building remains comfortable. Heat is transferred from thermal storage into a heating distribution system as needed. Figure 2 shows a simple way to do this using a pair of closely spaced tees that provide hydraulic separation between the tank circulator (P2 , bottom right) and the distribution circulator (P3, top left).

Circulator (P2) in Figure 2 could be controlled as an on/off device, or as a variable speed injection pump. The latter allows accurate control of the water temperature sent to the space heating load. It also allows for outdoor reset of that supply water temperature.

Figure 3 (next page) shows how an auxiliary heat source would be integrated into this piping arrangement. Another set of closely spaced tees connects the auxiliary heat source to the distribution system. These tees provide hydraulic separation between circulator (P4) and the distribution circulator (P3). The auxiliary heat source also connects “downstream” of the thermal storage tank. This allows the coolest water in the system, that returning from the load, to flow into the lower tank connection. This enables the renewable energy heat source to operate at the lowest temperatures the system can provide. Lower water temperature operation increases the efficiency of most renewable energy heat sources.

The auxiliary heat source is only turned on when there is a demand from the space heating load, and when the temperature

of the water supplied to the load drops slightly below the minimum value necessary to maintain the heating load, as determined by an outdoor reset controller.

In systems with this configuration (e.g., thermal storage heated by a renewable heat source, along with an auxiliary heat source) it’s important not to allow heat produced by the auxiliary heat source to inadvertently enter the thermal storage tank.

Doing so would allow high grade energy such as gas, propane, fuel oil or electricity to be converted to lower grade energy (e.g., heat) before that energy is needed by the load. Heat is much harder to store compared to keeping energy in high grade form until needed.

The key to preventing inadvertent transfer of heat produced by the auxiliary heat source into thermal storage is by comparing the temperature of the water returning from the distribution system to that at the upper header of the thermal storage tank.

As long as the temperature at the upper tank header is a few degrees higher than the temperature of water returning from the distribution system, the thermal storage tank, or the renewable heat source that supplies it, can make a positive energy contribution to the space heating load. This control

Continued on MH26

September 22nd at 3:00 EST

Anticipated length: 50 minutes with 10 minutes for Q&A

Why air-to-water heat pumps are a market opportunity for hydronic professionals.

There’s a world wide trend underway that will undoubtedly affect the future of North American hydronics technology. That trend is away from fossilfueled boilers and toward electrically powered heat pumps. This trend presents a significant opportunity for hydronic pros that are ready to take advantage of it using modern air-to-water heat pump systems.

This webinar will introduce the basics of air-to-water heat pumps, describe why they will be a new niche for hydronic professionals, and show some basic system configurations. Attendees will see how their current knowledge and skills in crafting modern hydronic systems can be leveraged around this new heating / cooling source.

• Understand the basic operation & performance of air-to-water heat pumps

• Grasp global trends that will increase this market niche

• Understand the importance of low water temperatures in air-to-water heat pump systems

• Learn how to configure a basic system for heating and cooling

Presented by

tem. If the temperature at sensor (S3) subsequently drops to within 3-degrees F of the temperature at sensor (S4), circulator (P2) is turned off. The on/off temperature differentials of 5F and 3F are only suggested values. To minimize sensing error it’s best to use identical mounting techniques for both sensors.

Figure 4 shows the simple wiring needed to combine the functions of the outdoor reset controller with the differential temperature controller.

For the wiring shown, the controllers are turned on only when there is a demand for heat from the load. Both are assumed to be powered by 24 VAC.

When the normally open contact in the differential temperature controller closes it passes line voltage to operate circulator (P2). When the normally open contact in the outdoor reset controller closes it signals the auxiliary heat source to operate. That heat source is shown as being supplied from a separate electrical source. Circulator (P4) is powered through that same electrical source and operates whenever the auxiliary heat source is on.

The controllers shown are readily available and are relatively inexpensive. The control functions they provide are well established over several decades. The combined functionality of these two controllers provides a simple and repeatable way to manage heat input to a space heating distribution system from both a renewable heat source, (or heat stored from off-peak electricity), and an auxiliary heat source. <>

function is easily handled using a differential temperature controller.

Figure 3 shows a differential temperature controller installed to compare the temperature at the return side of the distribution system (S4) to the temperature at the upper tank header (S3). Circulator (P2) is only allowed to start if

the temperature at sensor (S3) is at least 5-degrees F above the temperature at sensor (S4).

This prevents heat generated by the auxiliary heat source from being inadvertently sent into thermal storage. It also prevents flow from what might be cool thermal storage into the distribution sys-

John Siegenthaler, P.E., is a mechanical engineering graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and a licensed professional engineer. His latest book is Heating with Renewable Energy (see hydronicpros.com).

Fits all of our most popular products

•Low-lead, dezincification resistant brass alloy for durability.

•Union fittings for fast and easy installation and service.

•Meets the requirements of ASTM F1960 for cold expansion fittings.

Components for today's modern hydronic systems

Heating & Cooling

Viessman is one of the most prefered and trusted brands in hydronic heating solutions in Canada for 40 years. Whether your project is a new home, commercial residence, or retrofit we offer heating solutions supported with digital tools to provide peace of mind at your fingertips:

• Program, remotely monitor & control your boiler using ViCare App

• Free expert advice when you request a heating system consultation online

• Extended 5 year parts and labour warranty for residential gas-fired condensing boilers up to 300 MBH input*