UNFAIR

ADVANTAGE

Our Steel Pumpers. Your Steel Nerves. Fire doesn’t always fight fair. And you deserve every advantage you can get. You deserve an E-ONE Stainless Steel Pumper

The body is forged entirely of stainless steel including hinged doors and the sub-frame, providing the unmatched performance and durability you can count on with every call.

The bottom line: with E-ONE and your crew, fire doesn’t stand a chance.

10

BUildiNg partNErships

A mutual-aid association in southwestern Ontario had a mission: to build a better training centre through donations, community partnerships, perseverance and plain old hard work. Now, as Laura King writes, the Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Fire Training Complex is a firefighter’s field of dreams.

28

lEadiNg FrOM thE FlOOr

Many firefighters have identified a need for change or improvement, but have experienced frustration because they lack the rank or authority to make that change. However, as Timothy Pley writes, there are things that firefighters can do to put their good ideas into practice.

38 prOtOcOl aNd prOpEr drEss

Canadian honours and decorations are often the most puzzling and deliberated aspect of a firefighter’s dress uniform. Kirk Hughes explains when to wear which ribbons, how to order medals, and where to pin everything on your dress uniform.

By L AURA K ING Editor lking@annexweb.com

Getting the message to the masses

I comment

t was a year ago this month – Thursday, June 14, 2012, in fact – that I had the pleasure of visiting the Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Fire Training Complex in Quinte West, Ont.

Deputy Chief Rob Rutter of Prince Edward Fire had been after me for some time to do the short road trip down Highway 401 to see how the community had pulled together to expand the training centre, and to witness the Module A course in action.

The day was fantastic (as Rutter had promised it would be) – sunny and warm but not too hot for the 25 participants who were divided into groups and run through evolutions on several training props and scenarios.

Several things struck me.

• The quality of the instruction: there were three local instructors and four from the Ontario Fire College – all were focused and disciplined but kind and helpful when the students had trouble getting their SCBAs on in the required time, or when they panicked a bit during the search-and-rescue evolution.

oped the muscle memory necessary to get their SCBA on quickly, efficiently and accurately but were making progress, and some firefighters who had been around for a while but hadn’t yet found time to complete the course.

There was lots of talk around the picnic tables at lunch about who had been to a structure fire and what role each firefighter had played –replacing cylinders or manning hoselines, depending on levels of experience –and it was clear that everyone who was there wanted to be there.

ON thE cOvEr

Students are run through evolutions at the community supported Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Fire Training Complex in Quinte west., Ont. See story page 10.

• The extra sets of hands that materialized from who knows where to set up hoses, act as runners and provide first aid.

• The fact that all students were volunteer firefighters who had taken two days off work and had already done 40 hours of pre-course work at home.

There were very young firefighters – one confessed that his balaclava smelled Downy fresh because his mom had washed it (this elicited groans and guffaws and pretty much constant ribbing for the rest of the course)

– very new firefighters who hadn’t yet devel-

As regular readers know, I had a similar experience in Peace River, Alta., in April, where 43 volunteer firefighters took time off work to participate in Drager’s LiFTT program. Earlier this month in Wolfville, N.S., 500 firefighters – some career but mostly volunteers – spent a weekend training at FDIC Atlantic.

I’m reaching a bit here, but many of those firefighters in Peace River went to Slave Lake two years ago to battle the wildfire that ravaged the town. Now, a Slave Lake mall owner is suing the municipality and the fire department, claiming improper and inadequate firefighting techniques.

Municipalities set the level of fire and emergency service. In most Canadian cities, towns, villages, municipal districts and regions, that means volunteers provide fire protection.

I know I’m preaching to the choir. Whose job is it to get the message to the masses?

ESTABLISHED 1957 June 2013 VOL. 57 NO. 4

EDITOR LAurA KiNg lking@annexweb.com 289-259-8077

ASSISTANT EDITOR OLiViA D’OrAZiO odorazio@annexweb.com 905-713-4338

EDITOR EMERITUS DON gLENDiNNiNg

ADVERTISING MANAGER CATHEriNE CONNOLLY cconnolly@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext. 253

SALES ASSISTANT BArB COMEr bcomer@annexweb.com 519-429-5176 888-599-2228 ext. 235

MEDIA DESIGNER BrOOKE SHAw bshaw@annexweb.com

GROUP PUBLISHER MArTiN MCANuLTY fire@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT MiKE FrEDEriCKS mfredericks@annexweb.com

PuBLiCATiON MAiL AgrEEMENT #40065710 rETurN uNDELiVErABLE CANADiAN ADDrESSES TO CirCuLATiON DEPT.

P.O. Box 530, SiMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.ca

Printed in Canada iSSN 0015–2595

CIRCULATION

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.ca

Tel: 866-790-6070 ext. 206

Fax: 877-624-1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Canada – 1 Year - $24.00

(with gST $25.20, with HST/QST $27.12) (gST - #867172652rT0001) uSA – 1 Year $40.00 uSD

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund of the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Occasionally, Fire Fighting in Canada will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. if you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission ©2013 Annex Publishing and Printing inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

www.firefightingincanada.com

@fireincanada

Photo BY laura king

statIontostatIon

across canada: Regional news briefs

CFF writer Randy Schmitz nominated for Manning Award

As one of 45 nominees for the 2013 Ernest C. Manning Awards, Randy Schmitz and his nearly indestructible extrication gloves, the Schmitz Mittz, were introduced to members of the Alberta legislature on April 16.

“There was a need for firefighters to have this style of glove,” Schmitz explained. “The gloves that were out there, nothing offered both a high level of protection and a high level of dexterity; and nothing lasted that long. That was my frustration.”

Schmitz is a leading Canadian expert in extrication and the longtime auto-ex writer for Canadian Firefighter and EMS Quarterly.

The original Schmitz Mittz, the RescueX extrication gloves, offer slash resistance, a waterproof layer and high heat resistance. They also feature a carbon fibre knuckle pad, protect wearers against blood-borne pathogens and other fluids such as motor oil and battery acid, and are machine washable.

Many of these features were

born from Schmitz’s own experiences with the shortcomings of typical extrication gloves.

“For example, [the idea for] the carbon fibre knuckle piece: if your attention is diverted momentarily, your hand can get stuck between the tool and the vehicle, and that can damage your hand,” he said.

“You also need that dexterity – changing the saw blade or the bits on a chisel. Those are tasks that you need to complete quickly and if you need to take your gloves off, you’re at risk [of being injured].”

Soon after the RescueX gloves gained popularity, the idea of improved work gloves began to spread across sectors. Schmitz Mittz now makes gloves for a variety of industries, including oil and gas, mining and construction.

The oil and gas glove and the utility armour glove adhere to similar protection standards to those governing the extrication glove, but offer additional features – such as enhanced knuckle protection – that are

the brass pole: promotions & appointments

and most recently served as deputy chief with the innisfil Fire and rescue Service.

more specific to those industries.

The Manning Awards –which comprise four individual awards – have been recognizing and supporting Canadian innovators of all ages since 1982.

“If anything, it’s not the actual fact of winning,”

Schmitz said, “it’s the networking that comes with it.

were promoted to acting captain.

When we were at the [Alberta legislature], it was great to meet all the people there.

“That’s the cool part, those people. We’ve already won, in a sense.”

Winners will be announced at the Annual National Manning Innovation Awards Gala on Oct. 16 in Calgary.

JONATHAN PEGG is the new deputy fire chief in georgina, Ont. Pegg, who has more than 17 years of fire-service experience, became a full-time firefighter with the richmond Hill department in 2002,

The Brock Township Fire Department in Cannington, Ont., has promoted several of its members. CHRIS GILLESPIE was promoted to district chief in February. in January, DERRICK O’GRADy and MIKE GILLESPIE were promoted to captain, while RICK CLARK, SCOTT GRANAHAN, RAy MILTON and ANDy KEELER

BOB CANNON, retired deputy chief in Mission, B.C., has returned to the fire service to act as interim chief following the retirement of ian Fitzpatrick. Cannon, who retired in 2007, has more than 45 years of experience with the Mission Fire/rescue Service.

JACK BURT has been appointed deputy fire chief for the fire department in Meaford, Ont.

Burt, a 14-year veteran of the fire service, was previously a captain at the South Bruce Peninsula Fire Department in Sauble Beach, Ont.

PAUL SEE is the new fire chief of the waskesiu Fire Department, in the Prince Albert National Park in

Speaker Gene Zwozdesky (middle) tries on a pair of Schmitz Mittz with inventors Calgary firefighter Randy Schmitz (right) and retired Capt. Jonathan Fesik (left) at the Alberta legislature.

Sparks to focus on safety

Longtime fire-service salesperson Kerin Sparks has joined bunker gear manufacturer Innotex as the company’s director of North American sales.

Sparks, who is based in Toronto, has more than 16 years of experience in the North American first responder market, Innotex said in a press release.

Sparks says he is excited about the expansion that Innotex has experienced in the 12 years it has been manufacturing turnout gear.

“The most appealing factor is that they’re a young company with substantial growth,” Sparks said in an interview.

Sparks previously worked for MSA, where he says he built

strong relationships with the International Association of Fire Fighters, the National Volunteer Fire Council and the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs.

These contacts, Sparks says, led him to sit on two CSA committees for respiratory protection. Sparks says he will continue to work with the IAFF, especially on its health and safety initiatives.

Gord Mills joins Eastway

Gord Mills has joined Eastway Emergency Vehicles’ sales team.

Mills has 20 years of experience as a chief officer with the Rideau, Cumberland and City of Ottawa fire departments, where he had direct responsibilities in the design and

acquisition of rural and urban emergency vehicles, Eastway said in a press release in April.

Previous to this, Mills held a management position at Eastway, overseeing the manufacturing and repair of fire and tanker trucks.

“Gord’s 20 years as a member of the OAFC, including 10 years on the board of directors, has provided him with opportunities to network and share knowledge with chief officers from across Ontario,” Eastway said.

Thank-you sign honours Alberta’s first responders

This thank-you to first responders sign appeared on the hill above the centre-oftown parking lot where the auto-ex course was running at the Peace Regional Fire Chiefs conference in Peace River, Alta., on April 12. Some investigation revealed that it had been posted by a former firefighter who had a series of bad calls and stepped back from the job. The man turned to poetry and music to heal, and the sign includes song lyrics. As one firefighter said, “The sign was special enough alone, even more so now knowing the history.”

For more on the conference and editor Laura King’s trip to Peace River, visit www.firefightingincanada.com and click on blogs.

Saskatchewan. See, who has more than 20 years of experience, joined the fire service as a volunteer firefighter in 1991, before becoming a captain and then deputy chief.

EDWARD MOHR has been appointed fire chief for the west Perth Fire Department in Ontario. Mohr, who is a 26-year veteran of the fire service, was previously captain for the municipality’s department.

retirements

IAN FITZPATRICK, fire chief in Mission, B.C., retired Feb. 28. Fitzpatrick, a 32-year veteran of the fire service, was promoted to chief in 2009.

WAyNE MORRISON, fire chief for the Shuswap Fire Department

in British Columbia, retired in November. Morrison had 29 years of fire service experience, including nine years as chief.

last alarm

TRAVIS GUEDES died April 17 after a courageous battle with brain cancer.

guedes, a nine-year veteran of the fire service, was a lieutenant and fire inspector with Salt Spring island Fire rescue in British Columbia.

PAUL VAN ZUTPHEN, a retired district chief with the Mississauga Fire and Emergency Services, died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage on March 29. Van Zutphen, 60, was vacationing with his wife in the Caribbean at the time.

br I gade news: From stations across Canada statIontostatIon

The COLWOOD FIRE RESCUE in British Columbia, under Fire Chief Russ Cameron, took delivery in March of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built pumper. Built on a Spartan Metro Star chassis, and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISL 450-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale 2000 1,750-gpm pump, a Waterous Advantus 6 Dual foam system, a 500-gallon co-poly water tank, and a Whelen LED light package.

The LONGUEUIL FIRE DEPARTMENT in Quebec, under Fire Chief Claude Chevalier, took delivery in February from L’Arsenal of a Pierce Manufacturing-built pumper. Built on a Saber chassis, and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISL 450-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Pierce 1,500gpm pump, a Husky 3 foam system and a 750-gallon co-poly water tank.

The WINDERMERE FIRE DEPARTMENT in British Columbia, under Fire Chief Jim Miller, took delivery in March of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built pumper. Built on a Spartan Metro Star chassis, and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISC 380-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale QMAX 1,750-gpm pump, a FoamPro 2001 foam system, a 750-gallon co-poly water tank, a Whelen LED light package, an Akron Apollo monitor, a TFT Extend-a-Gun and a Honda EM 5000 generator.

The LEDUC COUNTy FIRE DEPARTMENT in Alberta, under Fire Chief Darrell Fleming, took delivery in March of a Fort Garry Fire Trucks-built pumper. Built on a Spartan Metro Star chassis, and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISC 380-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Darley PSP 1,050-gpm pump, a FoamPro 2001 foam system, a 1,000-gallon pro-poly water tank, a Federal light package, FRC LED scene lights, an Elkhart Vulcan RF monitor and an Elkhart RAM monitor.

The MARIEVILLE FIRE DEPARTMENT in Quebec took delivery in February of a Rosenbauer-built aerial truck from Areo-Feu. Built on a Spartan chassis, and powered by an Allison 4000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISL 500-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale 1,250-gpm pump, a 500-gallon UPF water tank, a 109-foot ladder, outriggers and a torque box.

The SAGUENAy FIRE DEPARTMENT in Quebec, under Fire Chief Carol Girard, took delivery in February from L’Arsenal of a Pierce Manufacturing-built pumper. Built on a Saber chassis, and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISL 450-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Pierce 1,500-gpm pump, a Husky 3 foam system and a 750-gallon co-poly water tank.

WINDERMERE FIRE DEPARTMENT

COLWOOD FIRE RESCUE

MARIEVILLE FIRE DEPARTMENT

LONGUEUIL

buIldIng partnersh

partnershIps

Co-operation and ingenuity bolster training centre

By LAURA KING

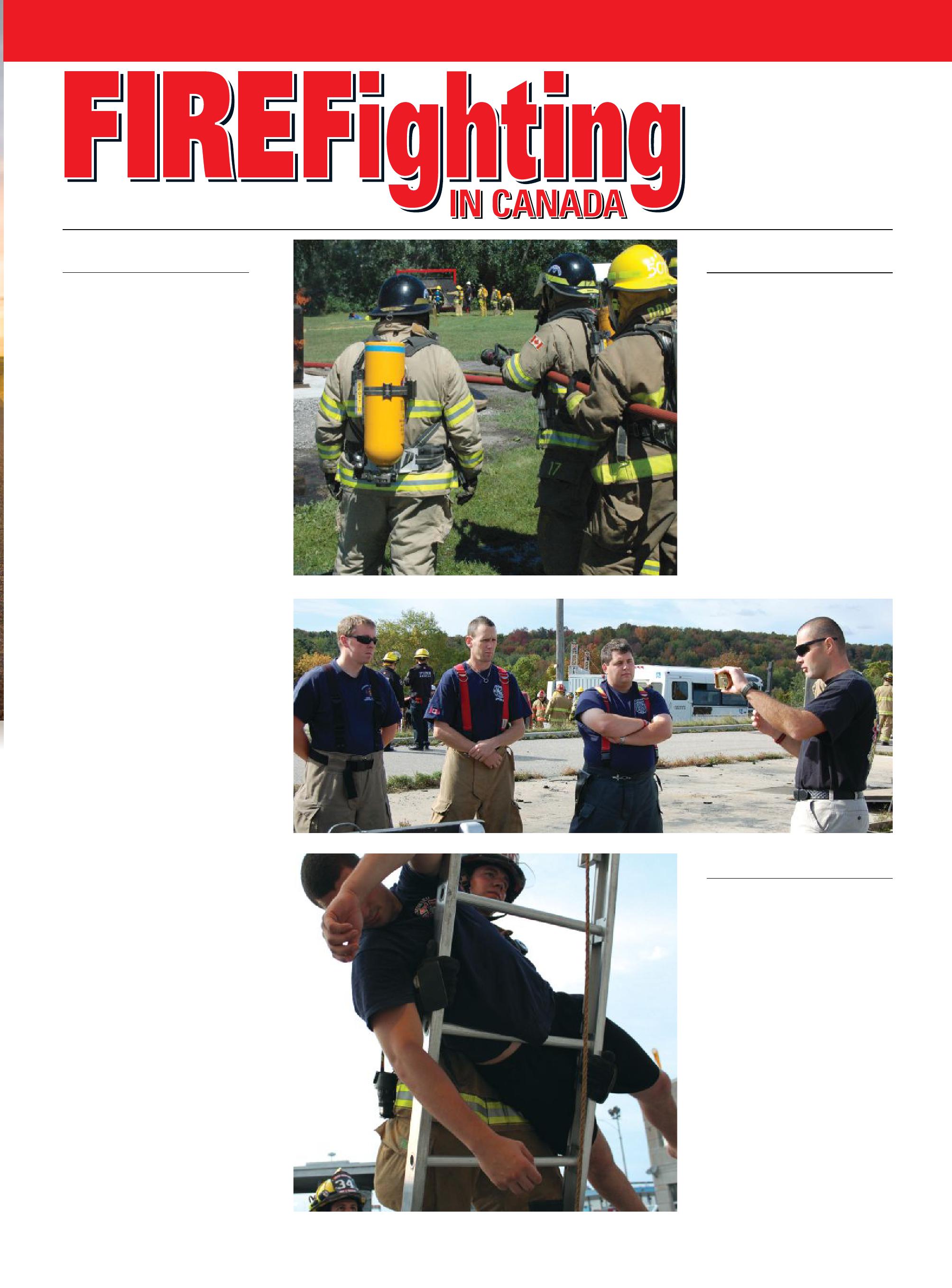

left: Students are run through the ventilation prop during Module

A training, which gives them nine sign-offs toward their Firefighter-1 certification.

abo V e : An instructor prepares a firefighter whose mask is blacked out to navigate the maze during Module

A training at the Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Fire Training Complex in Quinte West, Ont.

for Prince Edward County Deputy Chief Rob Rutter, the motto, If you build it, they will come, rings as true as the blood, sweat and persistence that has led to expansion and full-on programming at the region’s fire training centre.

The Hastings and Prince Edward Counties Fire Training Complex in Quinte West, Ont., is a shining example – literally, with its two new (or, rather, gently used) pumpers – of perseverance and community partnerships.

Few fire departments outside major centres enjoy the luxury of fully equipped training facilities; many rural fire departments have opted for online training as funds for firefighters to travel to provincial fire schools are scarce.

But for the Hastings-Prince Edward Mutual Fire Aid Association, which comprises 17 member fire departments, ingenuity trumped frustration and the original training centre – with a tower and classrooms – has been transformed into a firefighter’s field of dreams.

“If this facility were going to survive we knew we had to bring it back to life because it was slowly dwindling,” says Rick Caddick, the fire chief in Stirling-Rawdon, a picturesque community that supports its fire department and loves its hockey – Stirling-Rawdon was the winner of the Kraft Hockeyville contest in 2012.

“It was cheaper for departments to send the guys here to be trained than it is to send them to Gravenhurst to the Ontario Fire College,” Caddick says. “We don’t have to pay their mileage, they go home at night, and they’re training with men and women they’re going to work with every day.”

“And,” says Rutter, “it fits hand in hand with what’s happening in the province; the fire college announced [in 2012] that it’s delivering more courses off site than at the OFC.”

Still, says Caddick, the training ground is a well-kept secret. “There are still a lot of guys saying, we didn’t know that it’s here, and that it’s awesome.”

The training centre was the brainchild of the mutual-aid association back in the 1980s. The then City of Trenton (now Quinte West) provided the land on a 25-year lease for $1 a year, and CFB Trenton made a financial donation. Construction started on the tower in 1984 and a two-storey confined-space training module was added through a donation from Proctor and Gamble. In 2011, the Quinte West Fire Department donated a 1992 E-One pumper, and an outdoor shelter where firefighters can practice and gear up was built by a local contractor.

Back before municipal amalgamation in 1997, there were 30 fire departments in the mutual-aid association; members held barbeques and sold hats to raise money to build the training tower. The classroom building was added a few years later.

“That was the extent of the bricks and mortar for several years,” Caddick says. “Up to that point we ran more information-type courses; we weren’t accredited, but they were certificate courses.”

Then in 2008, says Rutter, the mutual-aid association and the facility’s board members knew they needed to do more to keep firefighters trained and equipped.

“This is before the Ontario Fire College had made the decision to get the courses out in the community,” Caddick says, “so we brought

Photos BY laura king

For more information, call your local Globe dealer or Safedesign.

British c olum B ia and a l B erta Guillevin

Coquitlam, British Columbia 800-667-3362

Calgary, Alberta 800-661-9227

Campbell River, British Columbia 250-287-2186

Edmonton, Alberta 800-222-6473

Fort St. John, British Columbia 250-785-3375

Kamloops, British Columbia 250-374-0044

Prince George, British Columbia 250-960-4300

Trail, British Columbia 250-364-2526

Que B ec

H.Q. Distribution

LaSalle, Quebec 800-905-0821

Boivin & Gauvin

Saint-Laurent, Quebec 418-872-6552

a tlantic Provinces K&D Pratt Ltd.

St. John’s, Newfoundland 800-563-9595

Dartmouth, Nova Scotia 800-567-1955

m anito B a and s askatchewan Trak Ventures

204-724-2281

[former instructor] Wayne McIsaac down from the college and he agreed to hold a Module A course here for one year and allow us to do live fire training here in the cans, and from that point forward it has grown. We’re doing legislation 101 here and fire-scene assessment is filled every year; this is the fifth year of Module A and we’re filled to capacity every year.”

Originally, the training centre’s board members looked after the details for the courses – hay and palates, drinking water, lunches, and whatever else was needed.

“As it has progressed,” says Caddick, “we certainly have become more proficient at putting the course on. There were usually four or five of us here working and running to get equipment; now it’s much easier because the support work that needs to be done – the hay is here, palates are here – because we have appointed a facility manager who looks after cutting the grass and that everything’s ready to go. We have worker bees.”

The training centre runs two trainer facilitator presentation skills courses each year, after which successful candidates can deliver training to their own firefighters and sign them off on skills. The first pump operations course was offered in September 2012, and fire-prevention officer courses begin this year. In October, the centre will run its first RIT/firefighter selfrescue program.

Rutter says the success of the training is due solely to the commitment of the surrounding departments.

“We have never done without,” Rutter says. “We put the word out that we need a pumper and someone pulls one out of service. We are becoming more self sufficient.”

2013 Ford Lariat to build a three-bay fire station for the training centre’s apparatuses.

In addition to the training tower, the classroom building, the shelter and the trucks, the facility includes a maze for training on entrapments, a ventilation prop, a new (in 2012) Bullex propane fire-hose training system and two large steel tanks used to teach direct and indirect fire attack, thermal layering, mechanical ventilation and fire behaviour.

Last summer, after a fair bit of negotiating, the training centre hosted its first auto extrication course, supported by the Burlington Fire Department because the Ontario Fire College no longer offers extrication programs.

Burlington is well known for its awardwinning auto extrication team, and its chief training officer, Bill Hammond, was instrumental in organizing the course.

“We go to more vehicle extrications than house fires,” Rutter said. “And Burlington donated a set of heavy hydraulics, so now we have our own.”

AJ Stone donated RIT packs and air cylinders after another donor provided facemasks and regulators, and has given the centre an MSA carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide detector for monitoring the atmosphere on the fire ground; M&L Supply “left us some nice hose and supply lines,” Rutter said. Darch Fire recently donated a hose reel for the centre’s Holmatro heavy rescue tools.

“The suppliers have been extremely supportive of this facility and this helps us immensely,” Caddick says.

877-253-9122

www.safedesign.com

The facility’s two recently donated pumpers – a City of Trenton 1990 E-One and a City of Belleville 1992 E-One – are welcome additions.

And now, the mutual-aid society is raising money through tickets sales on a $65,000,

In 2011, when a Module A program was running, organizers had erected tents to shelter the students while they geared up; the wind came up, the tents came down and a $24,000 shelter was born. RAD Home Improvement – which is owned by a facility committee member – donated time and labour, and the large structure now provides

Participants practice nozzle-and-hoseline skills during a Module A class in June 2012; there were 25 students in the class ranging in age from 20 to 45, all volunteer firefighters.

KOC H E K® LDH Water Systems

Storz Couplings

• Forged Storz Couplings 4”, 5” and 6”

• Durable QUANTUM® hard coat and MICRALOX® micro-crystalline anodizing

• Sure grip 3-piece collar for tight secure fit

• Stainless steel locking trigger

• High visibility recessed reflective tape available

Storz Hydrant Converters

• Forged 6 0 61-T6 Aluminum

• High Visibility Reflective Tape (colors)

• Recessed groove protects reflective tape

• Laser engraving on the cap front with your choice of coatings

M I C R ALOX Micro- Crystalline

A patented process, will extend the life of your aluminum parts up to 10 Times compared to conventional aluminum anodic coatings; more effectively resists salt, and chemical corrosion and attack

QUANTU M Hardcoat Color

• High quality durable hardcoat

• Vibrant anodized color

• Great for color coding

NATU R AL Hardcoat

• High quality durable hardcoat

• Most often specified by design and manufacturing engineers Meets

Kochek Company Inc. 75 Highland Drive, Putnam, C T 0 626 0 800 420 4673

which has expanded in the last few years, primarily through donations and elbow grease provided by volunteer firefighters and area businesses.

dry ground and weather protection for program participants.

The Bullex fire-hose training system is environmentally friendly – it uses propane rather than oils and fuels. All the propane lines and tanks were donated and installed by Tyendinaga Propane.

“It’s just talking to these people and communicating with them,” Rutter says.

“It’s about partnerships,” Caddick agrees. “Everybody brings something to the table.”

In addition, the mutual-aid group plans to remove the electric heat out of the classroom building to lower operating costs.

The training facility is accessible by local fire departments, which means as many as 1,000 firefighters can take advantage of it in a year.

“Any department can use it any time as long as we’re not running courses,” Caddick says. “We also have arrangements with CFB Trenton and they use it for specialized training; Proctor & Gamble uses it for confinedspace training.”

Rutter says the key to the success of the training centre is the passion of the committee members and their connections in the community.

“Every one of us brings our own thing to the table; for example, president Chuck Naphan is with Public Works so he has the contacts with the concrete and the gravel people, and everyone just comes together.”

And every department makes some kind of commitment to the facility; for example, two of the training centre’s in-house instructors – Bob Downey and Jim Young – are from Prince Edward Fire.

“That’s one of the things that Wayne McIsaac emphasized,” Rutter says. “You

have to get your own instructors so you become more self-sufficient.”

Each fire department pays dues to the mutual-aid association to cover the cost of mowing, plowing and utilities.

At the Module A session in June 2012, instructors Downey, Young and retired Belleville firefighter Peter Helm ran the course along with four instructors from the fire college.

The Module A program – an Ontario Fire College accredited course – gives firefighters nine sign-offs from component one of the Ontario firefighter curriculum. Module B was delivered in October 2012, after which students who had the required sign-offs could write their Firefighter-1 test.

“Firefighters today aren’t going to spend the time to attend unless they get accreditation,” Caddick says.

“They are permitted to write their exam if they so choose; some don’t want to but it’s an option they have; last October we had 40 people writing exams in this room, and they are all taking time off work – they are volunteers. There is a minimum of 40 hours of pre-course work that has to go into this. They get the binders in advance and the first thing the instructors will do is gather up binders and go through the pre-course work. This is a commitment these firefighters are making.”

As Rutter says, that spirit of volunteerism is what drives those involved in the training centre to go to the businesses in the community for support.

“This facility has been here for 28 years,” he says. “But in the last few, we’ve started putting time and money into it. Without a dream nothing’s going to happen. Without goals you’re not going to win the game.”

Deputy Chief Rob Rutter of Prince Edward County and Chief Rick Caddick of Stirling-Rawdon discuss the potential for ice-water training at the region’s training centre,

CORNERstone

By Ly LE QUAN Fire chief, Waterloo, Ont.

bChoosing to accept inevitable change

ooks can help shape who we are, prompt us to reevaluate what we stand for, and make us consider how we can become better at what we do. I have found that recommending books in my columns and presentations not only helps me to think about what each book offers readers, but it also helps me to suggest opportunities to my fire-service colleagues for self-improvement.

The first book that I recommend will get you to think outside of the box. The second book provides some great tips on how to become a better coach. By applying the lessons taught in these two books, you will be able to break down the imaginary walls that some of us erect, which will help you to better guide, support and mentor others.

In the first book, I Moved Your Cheese, author Deepak Malhotra tells how three mice discover that, instead of just accepting things as they appear to be, they have the ability to escape the maze in which they are confined and configure their environments to their own liking. Sometimes we feel as if we are being confined by our jobs or are somehow stuck in a maze with no exit. Is the challenge to get out of that maze, or to reinvent the world around us?

As the author notes, sometimes the burning question is not if the mouse is in the maze, but if the maze is within the mouse.

I Moved Your Cheese picks up where the popular motivational book, Who Moved My Cheese?, by Dr. Spencer Johnson, left off, and challenges the reader to take things to greater heights. In Who Moved My Cheese?, Johnson points out that change is inevitable and that we must accept this and find ways to embrace change. In I Moved Your Cheese, the reader is challenged to think beyond the belief that change is inevitable, and that we, therefore, need to accept change and move on. Malhotra’s book discusses how to become more resourceful by creating your own environment.

In the second book, Igniting the Third Factor, the author, Dr. Peter Jensen, encapsulates his life’s work into five core practices that leaders can use to ignite what he calls the third factor in themselves and in others. Jensen has participated in six Olympic Games, helping athletes and their coaches win Olympic medals. He has taken these teachings and coaching concepts to the business world and broken them down into five basic characteristics. I’m sure you will find Jensen’s theories of value as you pursue your goal of becoming a better coach and also helping your organization develop a true succession planning program.

The third factor that Jenson writes about is choice. This factor explains that the individual is allowed the opportunity to make a conscious choice to change and become a higher-level person.

The five characteristics that are discussed in great detail in the book are:

• Self awareness;

• The ability to build trust;

• The ability to use imagery;

• The ability to identify blocks when they occur; and

• Recognizing the importance of adversity.

As Jensen notes in his book, “If you learn to ask good questions,

In I Moved Your Cheese, the reader is challenged to think beyond the belief that change is inevitable, and that we, therefore, need to accept change and move on.

For example, I Moved Your Cheese says that if someone asks, who moved the cheese, leaders should explain that it doesn’t matter who moved it; it matters only that the cheese is gone.

Those of you who have read Who Moved My Cheese? may find this theory to be a somewhat challenging concept, but it is one that should be embraced if you want to move toward resolving the issues that are troubling you. There is one simple equation presented in Malhotra’s book: You want the cheese – but the cheese is no longer there; so, your only option is to go elsewhere to find the cheese. Learn how to break down those walls and embrace the concept of change, and you can create your own environment.

Lyle Quan is the fire chief of Waterloo Fire Rescue in Ontario. He has a business degree in emergency services and a degree in adult education. Lyle is an instructor for two Canadian universities and has worked with many departments in the areas of leadership, safety and risk management. Email Lyle at thequans@sympatico.ca and follow Lyle on Twitter at @LyleQuan

be an effective listener, give really good feedback and know how to confront your performers when things are not going well, you can do most anything.”

The author also suggests four good questions to help you get started: the first two questions focus on “I,” while the second two focus on “we.”

• What do you need more of?

• What do you need less of?

• What are we doing well?

• What needs work?

Those of us in the fire service will appreciate two terms that Jensen uses: extinguisher and igniter. Be an igniter by being there for your team, not an extinguisher who rarely seeks to support and embrace the team concept.

Although these books were written by different authors at different times, they complement each other by breaking down biases that we have and helping to ignite the abilities within ourselves.

On behalf of the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation and the committee, we want to thank all our generous sponsors who donated product, all participants in the online auction and everyone who attended the event on Saturday May 4th. And of course a big thank you to all the volunteers who helped make this a fantastic evening. Over $30,000 was raised! All of the money will go to education bursaries for children of our fallen firefighters. This was the 2nd annual event and we look forward to next year’s event being bigger and better. If you are interested in getting involved in this worthy cause, please contact Mark Prendergast at markp@mnlsupply.com or Kip Cosgrove at kcosgrove@vfiscanada.com. We welcome new committee members, volunteers, sponsors and donors. Once again, thank you, and we look forward to seeing you next year.

TRAINER’Scorner

An all-season guide to training

By Ed BrOUwEr

Ihave the honour of instructing at FDIC Atlantic in Wolfville, N.S., again this year. My son Casey and I will be travelling to Nova Scotia, the province where the Canadian fire service got its start. Although fire brigades can be traced back to the Roman Empire, it was in 1754 that the Union Fire Club was formed in Halifax, effectively becoming the first organized fire department in Canada; it became the Union Engine Company in 1768. In 1996, the municipalities of Halifax, Dartmouth, Bedford and Halifax County amalgamated to form the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM); 38 fire departments joined to become the Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency Service.

So, here we are some 250 years later and one thing is certain: a lot has changed. Change is inevitable, and change is good, but I fear we have become the victims of change. The demands and expectations placed on the fire service, particularly the volunteer departments, have changed and continue to change at an ever-increasing rate.

The Canadian fire service must be the agent of positive change, not the victim of inevitable change. We must keep up with the changes around us while protecting our greatest resource: the volunteer firefighter.

I am not talking about living in the past, or about living in the present while pretending it is the past. Yes, at one time all we did was put the wet stuff on the red stuff. We have changed, the demands on us have changed, expectations of us have changed, and technology has changed. If we don’t step up and change with these things, we will become antiquated. Worse yet, there is a risk of not adequately preparing the next generation of volunteers.

Volunteer fire departments are always just one generation away from extinction. It’s our job, as training officers, to make sure our firefighters are prepared not just for today, but for the future.

Many departments struggle to keep their doors open due to such issues as lack

The Canadian fire service must be able to keep up with the changes around it while protecting its greatest resource – the volunteer firefighter – through ongoing training.

Finding and keeping firefighters is difficult for volunteer departments. Keep your firefighters engaged by training them in the basics.

Photos BY o livia d ’ o razio

Page Ad (4-5/8" x 5") v4

of funding and shortage of volunteers. But there is another concern: volunteers may be in jeopardy of becoming overwhelmed, not by fire-related tasks, such as structural and wildland fire fighting, but by myriad additional training requirements, such as first response medical, extrication, hazardous materials response, and as witnessed in recently in Boston, terrorism.

It is not unusual for volunteer firefighters to spend hours at a structure fire or, depending on location and resources, a complex MVC, and then go to their day jobs. However, is it reasonable to expect a volunteer firefighter to spend six to eight hours flagging, which has been the case lately in our region? How much more can we expect from our volunteers?

With ever-tightening purse strings on the

training budget and fewer grains of sand in the hourglass, these extra assignments could end up exhausting us. Each volunteer department must stay true to its mandate and guard its members by not taking on too much. Sometimes, it is better to say no. Do not take on more responsibility than you can handle and don’t agree to commitments that you can’t keep.

So, how do we prevent our members from becoming overwhelmed?

A good place to start is by clearly expressing your department’s mandate; be sure each member understands it and then train to meet that mandate. Print the mandate on business cards and give one to each member. For example, the mandate of the Campbell River Fire Department in British Columba is to minimize loss of life and property for the City of Campbell River from fires, natural disasters, life-threatening situations, and to assist other emergency agencies.

Remember, our greatest resource is the firefighter. Keep firefighters engaged in this worthy calling by training them in the basics. Volunteer Training Drills, by Howard A. Chatterton, quotes Chief Ramon Granados of the Bowie Volunteer Fire Department and Rescue Squad in Maryland, who often said, “The public will probably forgive you if you have trouble with a difficult fire, but they will never forgive you if you don’t do the basics right.”

Give your members something to be proud of, raise the bar and stay on point. Leave the politics to the politicians. Ask yourself, “What if volunteers, didn’t volunteer?” Familiarize yourself with the Volunteer Firefighters Bill of Rights – several versions can be found online.

As a volunteer it is your right:

• To be assigned a meaningful task

• To be oriented, trained and supervised for the duration of your activity

• To ask questions about your task and seek feedback about your performance

• To be treated with respect and kindness at all times, by every member of the organization for which you volunteer

• To offer input to and feedback from the organization about the job or task you are performing, in an effort to improve your performance and the state of the volunteer fire service

• To be trusted with confidential information, which may be necessary to fulfill your task

• To expect that your time will be used efficiently and effectively

The following is a breakdown for a full year of training, divided into the four seasons with 12 practice sessions per unit. This may not meet your

Volunteer departments don’t have the luxury of having specialty task groups. Every member must be trained to the same level, because you never know who will be able to respond.

TRAINER’Scorner

Continued from page 22

s E as ON al trai N i N g t O pics

■ spriNg

1. Chimney fires

2. Advancing hoselines

3. SCBA basics

4. Driver training

5. Forcible entry

6. Ground ladders

7. Ventilation

8. SCBA emergencies

9. Nozzles and fire streams

10. Hydrants

11. Salvage and overhaul

12. Fire cause determination

■ sUMMEr

1. Urban interface fires

2. Hazmat operations

3. Pumping/drafting

4. Hose lays

5. Driver training

6. Vehicle fires

7. Suppression tactics

8. SCBA emergencies

9. Water supply

10. Hose streams

11. Foam

12. Operating hoselines

■ Fall

1. Rapid intervention

2. Hose handling

3. Suppression tactics

4. Propane safety

5. Below-grade fires

6. Reading smoke

7. Mayday

8. Chimney fires

9. Ventilation

10. Fire behaviour

11. SCBA maintenance

12. Firefighter survival

■ wiNtEr

1. Firefighter safety

2. Cold-weather pumping

3. Pre-plans

4. Communications and alarms

5. Room search

6. Compartment fires

7. Ropes and knots

8. Electrical safety

9. Building construction

10. Portable fire extinguishers

11. Incident command system

12. Sprinkler systems

specific training requirements, but it is a good place to start. Customize it to suit your needs.

When all is said and done, the above schedule constitutes more than 96 hours of training per firefighter, plus an additional 96 hours for the training officer to prepare. These are just the basics of fire training. We have not even begun to touch on first response medical, flagging, hazmat, terrorism, extrication, swift water rescue and high angle rescue, among others. Yes, you can do these on weekends, but these skills must be practised during the year and many require annual recertification. I’m not trying to discourage you, but volunteer departments don’t have the luxury of having specialty task groups. Every member must be trained to the same level, because you never know who will be able to respond. Be careful that you don’t bite off more than you can chew. It is much safer for your members to be proficient at one or two tasks, than inept at a dozen.

I have a huge appreciation and respect for the 127,000 volunteer firefighters in Canada. These men and women deserve to be well trained and given the utmost respect. Trainer’s Corner was birthed 11 years ago with the intent to help meet the needs of the volunteer training officer, so if I can help you in any way, please contact me. Perhaps it would do us all good to get back to meeting our mandates.

Until next time – stay safe and remember to train like lives depend on it.

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., and Greenwood Fire and Rescue. Ed has been in the fire service for 25 years, 18 of those as an instructor. He is a fire warden with the B.C. Ministry of Forests, as well as a wildland urban interface fire suppression instructor/evaluator. He has recently been ordained as a disaster response chaplain. Contact Ed at aka-opa@hotmail.com

Smooth Bore Performance from a Combination Nozzle…

leading from the floor

How newer firefighters can initiate and implement their ideas for change

By TIMOTHY PLeY

top : Younger fire department members may have great ideas for change and improvement but will likely need help getting their ideas heard. Modelling a desired behaviour is a good first step.

we have all experienced the frustration of identifying a need for change or improvement, but not having the rank or authority to make that change. While it is true that change is most easily managed from a position of authority, that doesn’t mean that change can’t be effected from anywhere else in the chain of command.

Let’s consider a common scenario: Quinn has been a firefighter for four years. He is not an officer, and although he is not the newest member of the department, he is still near the lower end of the seniority list. Quinn has an idea he thinks the department should implement in order to improve performance.

In the past, Quinn has seen others bring

up ideas for change, only to be shut down by officers and senior firefighters. Sometimes, those who advocated change were attacked personally.

Why do suggestions for change elicit such negative reactions from senior members? There are several reasons, not the least of which is that senior members feel ownership of current practices. They may have helped to develop those practices. Even if they haven’t, the fact that senior members have done things a certain way for a long time makes them defend those practices.

When a relatively new member comes along with a suggestion for change, even if that suggestion appears to have merit, senior members may oppose it because they perceive that a change will mean that the old ways were wrong. Nobody wants

You protect the public

Let us heLp protect you

For your cleaning, decontamination, inspection, testing, repair and record keeping of your firefighter’s protective clothing... we have you covered!

• 24/7 access to Firetrack®, the online data base that provides you with complete details of your C&M Program with FSM. We do the work for you!

• ETL Verified

• ISO 9001 Registered

• Fast turnaround

• Complete Bunker Gear Rental Program – Toronto Location

Certain changes that firefighters wish to make can’t be brought about solely by modelling a desired behaviour. For operational changes, firefighters may need to elicit the help of a sponsor – a higher-ranking member of the fire service.

to acknowledge that they may have been doing things wrongly; it is easier to resist the change and attempt to uphold current practices. This basic human nature is part of the reason the fire service has traditionally resisted change.

So, should Quinn try to forget his good idea, and continue to follow current practices? That will not help the department improve, and it may result in Quinn becoming one more disillusioned firefighter.

There are some things that Quinn can do to help ensure his idea is well received.

MOdEl thE dEsirEd BEhaviOUr

One of the best ways to effect change, regardless of your position, is to model the desired behaviour. As Mahatma Ghandi said, “Be the change that you wish to see in the world.”

If Quinn’s idea for improvement involves improving turn-out times, for example, Quinn could model personal behaviour that supports that change. He could make changes to his own personal actions to ensure that he is ready to respond quickly. You can be certain that if you model positive, professional behaviour, others will notice and, over time, will change their own behaviour to match yours.

In my department several years ago, one of our firefighters, John, noticed that when we responded to alarm calls there was no standard practice regarding which tools firefighters brought into the building. John did some research and, based on that research, he started to bring irons with him on every alarm call, unless he was directed otherwise by his company officer. He didn’t force anyone to acknowledge that current practices were lacking. Nobody had reason to be offended by John’s quiet leadership.

Soon, John’s officer came to rely on John having the irons with him. Other firefighters noticed, too. When they asked John about this, he shared his research with them. Eventually, it became standard practice for one firefighter to bring irons on alarm calls. John made this change in our department without confrontation and without any real authority. He modelled the desired behaviour and waited patiently for it to catch on.

Ontario (toronto) 1-888-731-7377

Western canada (calgary) 1-403-279-5095

Mid-West USa (Detroit, Mi) 1-866-877-6688

sEEk OUt a spONsOr

Some changes do require the direction of a person in a position of authority, an officer, for example. If Quinn’s idea involves an operational change as opposed to a change in individual behaviour, then he can’t implement that idea on his own. In this case, he needs a sponsor.

A sponsor, such as a chief or company officer, is somebody who has the necessary organizational authority to bring forward an operational

Continued on page 34

13-05-13 9:59 AM

Stick to the plan: the importance of ERPs

In the wake of some very serious industrial accidents around the world, many countries recognized the need for hazard-specific emergency preparedness and response. Processes and procedures were quickly mandated and implemented, gradually morphing into a standardized emergency response plan (ERP). Nuclear plants, oil and natural gas refineries, and chemical and fertilizer processing facilities, are examples of activities that require emergency response plans for unique hazards. Over the past 30 years, national standards, have been developed to provide consistent guidelines for emergency management that are applicable to most industries. Many government regulators also have strict rules for emergency preparedness and response, including minimum requirements for emergency response plans. So, what is the value for firefighters of an emergency response plan? In a worst-case scenario, a well-designed plan makes all the difference in the world.

There are many good reasons for companies to develop emergency response plans. Essentially, every plan should provide emergency personnel with enough information to facilitate a timely and effective response. However, too much information and detail can be just as bad as inadequate information. Although no two plans will be exactly the same, they should meet strategic objectives in terms of protecting people, property and the environment. Thus, each plan must address hazards and risks specific to the operation and the location.

Emergency response plans aim to provide responders with critical information about products and operational processes. For example, emergency response personnel will want to know how much product is stored within a vessel or pipeline and the physical properties of the product. Detailed information is vital and ultimately can determine whether the response is a success or failure. What is the quickest way to shut in a facility or stop the flow of product? How will the product disperse in standard atmospheric conditions? What are the best methods for containment and suppression? How many occupied buildings need to be evacuated? The ERP must provide responders with enough information to answer these typical questions.

chemicals react with heat and pressure. Other hazards at an industrial site, such as confined or restrictive spaces, may require specialized equipment and training.

Arguably, the most valuable tool in the emergency response plan is a site map. A well-developed map shows the location of critical processing equipment, emergency supplies, control points, entry and exit paths, safe areas for staging, occupied buildings, gas-plume dispersion, and suitable points for roadblocks and traffic control. In some circumstances, the maps identify residences within a designated hazard area; this allows emergency personnel to assess which residences should be evacuated and how many people require immediate assistance. For example, in Western Canada many petroleum and natural-gas industry plans contain maps showing emergency planning zones (EPZ) for the hazards of hydrogen sulphide, or explosion hazards such as high volume pressure pipelines, fuel tanks and natural gas liquid storage. Emergency planning zones are predetermined based on the worst-case scenario. Also, an EPZ should not be confused with other zones, such as isolation or hot zones. The EPZ size varies with the type of hazard and generally is measured by its radius in metres. Once the circular area has been drawn on the map, it is easy to identify roads, properties and other values at risk. Simply stated, a well-drawn site map that provides a

Simply stated, a well-drawn site map that provides a clear schematic with the necessary features saves valuable time. ‘‘ ’’

The safety of response personnel also relies on accurate descriptions of the hazardous substances. Valuable time can be wasted trying to obtain information about the physiological effects of chemicals and their exposure limits. The explosion at a fertilizer plant in the community of West, Texas, in April is an example of what can go wrong when emergency personnel do not have the knowledge of how specific

Mike Burzek is the director of public protection and safety for the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission. He has more than 20 years of experience in emergency response and public safety, including nine years as a paramedic. He lives in Dawson Creek, B.C., and can be reached at Mike.Burzek@bcogc.ca

clear schematic with the necessary features saves valuable time.

The emergency response plan should focus on practicality. A plan is of little use just sitting on the shelf, collecting dust. As technology changes, so too must methods and procedures outlined in the ERP. When was the last time the plan was updated? Periodic testing of an emergency response plan is vital. Is information readily available to response personnel? Are the roles and responsibilities clearly written and understood? Clearly, an effective plan provides all the necessary answers.

Developing an ERP requires a lot of resources, and the industry spends a lot of time and money making sure emergency response plans meet regulatory standards. It is critical that responders refer to these plans in an industrial emergency. A well-organized and practical plan can bring structure to those moments of crises. So, stick to the plan – it could save your life.

B y M IKE B URZEK

Options that fit your budget today and tomorrow.

Whatever your needs, Dräger has an SCBA in its portfolio that truly satisfies them. With the expansion of our Sentinel product line — which now includes lightweight, fully integrated, cost-effective options — our SCBA portfolio now allows you to mix and match harness solutions with PASS systems in a way that perfectly suits your department. It’s German engineering at its best. If you’ve been stuck with solutions that offer too much or not enough, Dräger is ready to outfit you with equipment that’s just right.

Whatever your needs, Dräger has an SCBA in its portfolio that truly satisfies them. With the expansion of our Sentinel product line—which now includes lightweight, fully integrated, cost-effective options—our SCBA portfolio now allows you to mix and match harness solutions with PASS systems in a way that perfectly suits your department. It’s German engineering at its best. If you’ve been stuck with solutions that offer too much or not enough, Dräger is ready to outfit you with equipment that’s just right. for more information visit www.draeger.com/scba

for more information visit www.draeger.com/pssseries

change. Quinn should start with his own company officer. He should ask for an opportunity to meet to discuss his idea. When presenting the idea, Quinn should be open to input that modifies the idea, and should ask the officer if he or she will bring the idea forward through the necessary channels.

Sometimes, when working with one or more sponsors, the origin of a good idea can be lost. Quinn should be prepared to share credit with his sponsors. If Quinn’s original goal was to see a good change implemented, he shouldn’t be too concerned about credit. Over time, people like Quinn are recognized as leaders.

givE yOUr idEa away

We have all seen individuals attempt to implement change, only to see the change fail because others didn’t really buy into it. The lesson here is that, when we set out to inspire others to support change, we need to allow those people to assume some ownership of new ideas in order to ensure their success.

There are two difficulties that arise when giving away good ideas. As hinted at above, the first is that, as others take ownership of your idea, your ownership diminishes. Some people refuse to share ownership of their ideas, and, consequently, those people do not make change in their organizations. Instead, they unhappily collect a list of good ideas that the fire department would not support.

The second challenge to giving away ideas is that, as others assume ownership, they make modifications to the idea, often making the idea better and/or more likely to succeed. It can be difficult to see your good idea changed, but it is a necessary part of seeing any idea implemented. In fact, experienced change agents know that early signs of success include broad ownership and tweaking of the original idea.

BE patiENt

There are a number of possible reasons a good idea is not immediately successful. Most often, it has more to do with current conditions within the fire department than an indication of the quality of the idea.

Throughout the early years of my career, I was known for asking questions. I would ask why we did things a certain way. Often my questions were met with hostility. I learned to choose when, where and with whom to ask those questions. Looking back, I can recall many changes that we made in my fire department that began because I questioned current practices.

Since the beginning of my career, I have maintained a written list of ideas for positive change for which we just weren’t yet ready. Many years ago, I entitled that list Things to Change, meaning things that I would do if I ever became fire chief. From time to time, I add to or delete from that list. The reason I mention my list is to illustrate that fire departments are not ready for some ideas, as good as those ideas might be. In those cases, writing down the ideas saves them for future use and helps us to move forward in a positive way, knowing that our good ideas are safe for future consideration.

BE a gOOd FOllOwEr

Every fire department has several members who are either sitting on good ideas or struggling to gain support to implement them. One of the best leadership techniques that any of us can employ is to identify a member trying to implement a good idea and support that initiative. Often we get too caught up in wanting to lead when what our departments really need is people who will follow and support others who are doing good work.

Timothy Pley is the fire chief for the City of Port Alberni, in British Columbia, and the first vice-president of the Fire Chiefs’ Association of British Columbia. E-mail Tim at timothy_pley@portalberni.ca and follow him on Twitter at @PleyTim Continued

BACKtoBASICS

Victim removal down ladders

– part 1

By Mark vaN dEr FEyst

one of the many functions of a truck company on the fire ground is to search inside a structure for any unaccounted for occupants, and then remove any victims quickly and efficiently. However, this task is not reserved for a truck company. It is often performed by the first-arriving unit, which could be an engine company, a squad or rescue company, or a ladder company. Regardless, if the conditions warrant a fast attack of the fire, a search should be commenced immediately so the removal of any occupants can take place.

The fire conditions will dictate whether an occupant inside a structure will be a victim rescue or a victim removal. The decision to conduct a search must be made within the first few moments of arrival, which will set the tone and pace for the operation.

Once a victim has been located, he or she needs to be removed. This removal should be quick, using the nearest exit point, which in most areas of a home, will be a window. The interior rescue team will be able to easily drag the victim a short distance to the window and get another team outside to move the occupant down a ladder to safety.

The window may be laddered by one firefighter or by a team of two. If two firefighters are assigned, then there will be ample help to bring down the occupant. If only one firefighter is available to ladder the window, then the interior rescue team may need to help in the descent. When there is just one available firefighter to ladder the window, that firefighter will heel the ladder at the bottom while the interior team sends one firefighter out onto the ladder to receive the occupant as the person is passed through the window.

Passing the victim through a window will be the tough part for the interior team. Lifting a person from the floor to the windowsill will be enough to fatigue the crew; it will be a challenge to muster the energy required to drag the victim there. If the lift requires both firefighters and just one firefighter is available to ladder the outside window, the occupant will have to be staged on the windowsill so that one firefighter from the interior rescue team can climb over the occupant and onto the ladder. That firefighter will then be ready to receive the occupant as the remaining interior rescue firefighter helps to push and guide the occupant out.

The easiest way to bring a victim down a ladder is to position him or her horizontally across the arms of the firefighter. This position allows the firefighter to maintain control of the victim at all times while descending down the ladder, one rung at a time. This position can be easily set up with either the victim’s head or feet being passed through the window first. The firefighter on the ladder will guide the occupant into the correct position, as seen in photo 1.

In photo 2, you can see how the occupant ends up on the ladder –lying horizontally across the arms of the firefighter. It is important that the occupant be firmly supported in two key areas: under the armpit and between the legs. The firefighter will be firmly grasping the beams of the

Photo 1: When removing a victim down a ladder from the second storey of a structure, the firefighter on the ladder outside of the building guides the victim into the correct position.

Photos BY Mark van der f e Y st

Photo 2: The victim will end up on the ladder lying horizontally across the arms of the firefighter.

ladder – not the rungs – allowing him to easily climb down the ladder without losing control of the victim. By placing his arms under the victim’s armpit and between the victim’s legs, the firefighter ensures that the occupant will not slide out from underneath him and fall to the ground. Unconscious victims are not able to support themselves; the rescuing firefighter will have to do all of the work.

The occupant should be positioned so that he is lying right at the centre of the firefighter’s torso. Having the victim in this position means the firefighter’s arms can be at a 90-degree angle, rather than almost straight out, as they would need to be if the occupant were high up near firefighter’s chest. Positioning the victim at the firefighter’s torso allows for better control and is less fatiguing for the firefighter.

In photo 3, you can see that the occupant is lying at an angle across the firefighter’s body and the ladder. Depending upon the size and weight of the occupant, the firefighter may have to adjust the position of the occupant so that he is balanced on the ladder and across the arms. This can be accomplished by the firefighter sliding one of his hands down the ladder beam to adjust accordingly. Once the balance point is located, the occupant will slide down the ladder much more easily.

In photos 4 and 5, you can see how the occupant is removed from the ladder and

carried away to awaiting medical personnel. The firefighter will drop the bottom half of the occupant onto the ground by removing his hand from between the victim’s legs. The firefighter will then take that free hand and reach under the occupant’s other armpit and grab both of his own hands. Once the firefighter has a firm grasp, the firefighter can drag the occupant away from the ladder.

Practising this technique will help you and your crew to become proficient and comfortable executing this type of rescue.

Mark van der Feyst is a 14-year veteran of the fire service. He works for the City of Woodstock Fire Department in Ontario. Mark instructs in Canada, the United States and India and is a local-level suppression instructor for the Pennsylvania State Fire Academy and an instructor for the Justice Institute of B.C. E-mail Mark at Mark@FireStarTraining.com

Photo 3: The firefighter will have one arm under the victim’s armpit and his other arm between the victim’s legs.

Photo 4: To get the victim off of the ladder, the rescuing firefighter will remove his arm from between the victim’s legs, allowing the legs to drop to the ground.

Photo 5: The firefighter will then grasp his own hands in front of the victim and drag the victim to awaiting medical personnel.

Protocol and proper dress

Navigating the rules and regulations around medals, honours and awards

By KIRK HUGHES

TOP: Members of the Canadian fire services attend the monument unveiling and memorial service for the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation in Ottawa in September. It is common practice to wear dress uniforms, including any honours, during memorial services.

RIGHT: The first three medals (from the left) are federal medals; the fourth is the Fire Services Long Service Medal from the Province of Ontario. Note the bars on the ribbons of the last three medals. These bars signify additional service.

Canadian honours and decorations are often the most puzzling, and deliberated, aspect of a firefighter’s dress uniform. Although the Governor General regulates most medals though the Chancellery of Honours, sometimes there is confusion about what constitutes an official award and whether or not it can be worn on the dress uniform.

Common awards that are associated with uniforms are divided into honours, undress ribbons, commendation pins and hazard skill badges.

Modern awards are often classified by the agency that presents them. Federal honours often come from the Governor General acting on behalf of the Queen and include such examples as the Diamond Jubilee Medal and the Fire Service Exemplary Service Medal. Provincial or territorial honours, such as the Saskatchewan Protective Services Medal or

the Ontario Firefighter Medal for Bravery, are often awarded by the lieutenant-governor. Lastly, albeit rarely, a foreign government may bestow an honour on a Canadian citizen, such as the United States’ Bronze Star Medal, and with the proper protocol, it can be worn on the uniform. These are the three branches of awards approved by the national Canadian Honours System.

According to the Governor General’s website, the purpose of the Canadian Honours System is to “recognize those people who have demonstrated excellence, courage or exceptional dedication to service in ways that bring special credit to this country.” Federal awards can be separated into three categories: orders, decorations and medals.

The website explains that orders, such as the Order of Canada, the Most Venerable

By V INCE M AC K ENZIE Fire chief, Grand Falls-Windsor, N.L.

cVOLUNTEERVIsIon

Old fire dogs learn new tricks

anada’s fire service is a network of firefighters, officers and departments of all types. Training opportunities are growing. Today’s firefighters have so many of these opportunities at their fingertips that I am envious of the younger generations who are growing up with the Internet, smartphone apps, YouTube and Twitter. When I joined the fire service, training was done in our own department, by the warhorses who came before us. Technology included pinwheel filmstrips and even eight-millimetre film. Magazines were few and far between and training manuals were just catching on. On our training night, we would go out and learn the way “we always did it.” All of our training was steeped in tradition and old habits.

That said, even back then, some of us young firefighters started using technology; VHS became all the rage and we could take training videos and watch them in our own homes. As young firefighters, we were eager to learn all the tricks of the trade and the techniques that those warhorses passed down. I sometimes think back to those times and wonder how we ever got through it without getting hurt more often. Each fire department had its own way of doing things. Portable radios, SCBA and bunker gear were luxuries. Then as we learned more, we, as young firefighters, started to question our own techniques.

For some time now, I have subscribed to the three Ts of motivation for firefighters:

Technology – When a fire department receives new fitness or training equipment, the motivation to be more active or involved gets turned up for a while. But, once the novelty of the new equipment wears down, so too does motivation. Unfortunately, our budgets don’t allow for new technology every six months.

Training – Training allows us to build confidence and be better equipped to do the job. Training keeps us on our toes; there is always something new to be trained on and it can be done relatively inexpensively.

at the invitation of the Maritime Fire Chiefs Association. I had the pleasure of spending several days with Chief Schreiner. While travelling with this inspiring chief from a small town on the other side of the country, it became clear to me that our fire service needs more of this type of connectivity. I have attended my share of conferences and I am a firm believer that we all need to spread our wings, open our minds, find good things and bring them back to our departments. What this forwardthinking and experienced fire chief is doing is admirable.

Schreiner’s career mirrors mine; like me, he was a small-town volunteer firefighter, experiencing all the ups and downs of fire-hall politics and the like. Some people reach points in their careers after 25 years at which the tendency is to coast until retirement. Others, like Chief Schreiner, have a passion that keeps growing. After spending time with Schreiner, I found that I had a new mentor. We discussed at length how the fire service was changing and he and I both felt that we were headed for greater successes through training opportunities and connectivity. Gone were the days of fire departments staying in their own little worlds, absorbed in the traditions within their communities and continuing with their bad habits.

The tour, which was nicknamed Stopbad to fit into 140-character tweets better than Safe and Effective Scene Management, included 11

Tradition was going out the window as part of a tradeoff for a safer and more effective fire service. ‘‘ ’’

Tragedy – This motivation always comes too late, but when tragic events happen in our community or fire department, firefighters often vow to make things better and work harder. This motivation is often short lived, as well.

Training is the single most motivating factor that we have to keep our crews engaged.

Firefighters in Atlantic Canada recently had the opportunity to attend the Safe and Effective Scene Management training sessions with Fire Chief Gord Schreiner of Comox, B.C., who toured the eastern provinces

Vince MacKenzie is the fire chief in Grand Falls-Windsor, N.L. He is the president of the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Fire Service and a director of the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs. E-mail him at firechief@grandfallswindsor.com and follow him on Twitter at @FirechiefVince

seminars and more than 500 participants. Both Chief Schreiner and I noticed another pattern that was a little surprising: we observed that both senior firefighters/officers and younger firefighters were participating in the sessions. Older firefighters genuinely embraced some of the changes proposed. Tradition was going out the window as part of the tradeoff for a safer and more effective fire service. More importantly though, we were astounded at the enthusiasm from fire officers and chiefs who had 25 to 30 or more years in the fire service. These veterans were the same types of warhorses I had as trainers but they were actually opening themselves up to new things.

The Stopbad tour was a great success, a great lesson in Canadian firefighter training, and, more importantly, served as reinforcement that we still have seasoned veterans out there with the enthusiasm of young rookies, eager to learn and continue to grow. This is a refreshing trend. So, rookies, don’t put the old warhorses out to pasture yet!

left: This mount shows a collection of federal orders and medals. From left: the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal, the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal and the Service Medal of the Order of St. John.

centre : This National Defense Service Medal from the United States is an example of a foreign award that, unless approved by the Governor General, should not be worn with Canadian Honours.

r I ght: The medal on the left, which is an International Firefighters Medal, was acquired by purchase and, therefore, is only to be used for display purposes. The medal on the right is an internal fire department award, and should be worn only on the right side of the body, when appropriate.

Continued from page 38

Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, and various provincial orders, recognize “significant achievement and remarkable service.” Decorations, meanwhile, are often awarded for acts of heroism, by both civilians and those in the military, and recognize “exceptional devotion to duty.” Decorations include such honours as the Victoria Cross, the Medal of Bravery and the Meritorious Service Medal. Usually, these decorations entitle the recipient to use post-nominal initials.

Medals are the most common honour bestowed by the federal government. They recognize military service, and war and operational deployments; commemorate special events; and commend longterm exemplary service. Examples include the Canadian Peacekeeping Service Medal, which was inspired by the United Nations Peacekeepers, the various NATO service medals, the Canadian Forces Decoration (which, despite its name, is actually a medal) and the exemplary service medals for policing, fire and emergency medical services.

Provincial and territorial awards differ slightly in category and, except for the orders, should be worn to the left of all federal honours. Foreign honours, which are sometimes called imperial honours when awarded after 1972 by British or Commonwealth nations, under the authority of the Crown, can be worn only after the honour has been approved by the governor general in council and, again, only after all other medals.

Official honours (which we’ll call medals) are worn on the left side of the dress uniform. Ideally, medals should be professionally court mounted, or fixed to a piece of buckram so that the medals do not move around or bang into each other, according to the order of precedence. The medals are worn on the left lapel of the chest so that the edge of the mount rests on the chest pocket. If more than one medal has been awarded, then the mount of medals is referred to as a rack. If five or more medals have been awarded, the rack should be mounted so the ribbons overlap slightly. Medals are never worn in more than one row and should not extend past the middle of the chest or the left arm sleeve. Wearing loose medals is permitted,

but avoid placing two loose medals on either side of the brass button of the chest pocket on the dress uniform.

There are some legal aspects to consider when wearing orders, decorations and medals. Under Section 419 of the Criminal Code of Canada, it is illegal for anyone other than the recipient – such as friends or relatives – to wear the orders, decorations or medals that someone else received. This issue is most evident around Remembrance Day. Occasionally, relatives of deceased medal recipients will wear the insignia to honour that person. Other times, less scrupulous people have been caught wearing honours they have not been awarded, have not earned, or simply purchased for wear. These people are often identified by other firefighters, military veterans groups and spectators, and bring a lot of bad press to the department or agency that they claim to represent. Furthermore, such acts can result in charges and a criminal record.